Abstract

The ultra-slow relaxation dynamics of glasses at ambient temperature provide a promising alternative for dating glasses with extremely low isotopic content that cannot be dated using traditional radiometric methods. However, these ultra-slow, nonlinear aging dynamics remain poorly understood due to the lack of accurate theoretical models and long-term experimental validation. Existing equilibrium-based dynamics models substantially overestimate relaxation times at temperatures far below the glass transition temperature, making it difficult to model and quantify non-equilibrium aging over geological timescales. We address this challenge by formulating an empirical equation that quantifies the non-equilibrium effective relaxation time (τeff) for various glasses, including metallic glasses, organic amber, and lunar glasses. Our findings demonstrate a universal nonlinear aging dynamics governed by a single τeff, which follows a robust empirical relation parameterized by aging temperature and material-specific fragility. Employing this equation, we propose a universal glass kinetics dating method, conceptually analogous to radioactive decay, where τeff serves as a material-specific decay constant. This approach enables dating of glassy materials over timescales spanning decades to billions of years. This work bridges a fundamental gap in glass aging theory and establishes a practical framework for dating geological and planetary glasses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glasses, although macroscopically solid and apparently static, are fundamentally out-of-equilibrium systems that evolve continuously over time1,2,3. This structural evolution, known as physical aging, arises from an extremely slow relaxation of the disordered structure toward lower energy configurations. At temperatures near the glass transition temperature (Tg), the aging process has been extensively studied, with clear manifestations such as enthalpy recovery4,5, volume relaxation6, and mechanical stiffening7,8. However, at temperatures far below Tg—such as ambient or geological conditions—the dynamics of aging slow so dramatically that relaxation becomes effectively undetectable within conventional experimental timeframes. Yet mounting evidence challenges the long-held assumption that glasses are entirely “frozen” in this regime. Observable aging effects have been reported over timescales ranging from decades to billions of years, in systems including metallic glass (MG)5, polymer9,10,11, and silicate glasses12,13. This recognition raises a central question in non-equilibrium physics: how can we quantitatively describe and predict the dynamics of disordered systems evolving over geological timescales?

One of the most remarkable features of glass aging dynamics is its inherent nonlinearity8, 14, 15. In equilibrium supercooled liquids, the relaxation behavior in response to perturbations (e.g., subtle temperature jump) can be well described by a stretched exponential Kohlrausch-Williams-Watts (KWW) function16, 17: \(\phi \left(t\right)=\exp \left[-{\left(t/{\tau }_{{\mbox{eq}}}\right)}^{\beta }\right]\), where \(\phi \left(t\right)=\left[p\left(t\right)-p\left(\infty \right)\right]/\left(\left[p\left(0\right)-p\left(\infty \right)\right]\right)\) is the normalized relaxation function, and p(t) is the measured quantity (e.g., enthalpy, density, modulus). And τeq here is the equilibrium relaxation time which does not depend on aging time. Unlike equilibrium supercooled liquids, non-equilibrium glasses exhibit progressively slower and history-dependent relaxation. To describe this nonlinear aging dynamics, the concept of material time is introduced14,15,18,19, and a nonlinear integral function is required8:

where \(\xi \left(t\right)={\int }_{0}^{t}d{t}_{1}/{\tau }_{{\mbox{neq}}}\left({t}_{1}\right)\) is the dimensionless material time, and τneq is the instantaneous relaxation time which is not fixed but evolves continuously with aging time. This nonlinear integral form introduces substantial complexity, as the time-dependent nature of τneq(t) prevents a closed-form analytical solution, requiring numerical integration or approximation methods.

This mathematical complexity reflects a deeper conceptual challenge: accurately capturing the nonlinear, time-dependent nature of τneq(t) in theoretical models. However, most widely used models—including the Arrhenius, Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann (VFT)20,21,22, Parabolic23, and MYEGA relations24—were developed to capture equilibrium or near-equilibrium dynamics. When extrapolated to deep sub-Tg regimes, they often yield vastly overestimated relaxation times, in some cases even exceeding the age of the universe. Even frameworks explicitly designed for non-equilibrium behavior, such as the Narayanaswamy-Moynihan (NM) model18,25, treat relaxation as quasi-equilibrium and fail to fully account for the nonlinear growth of τneq(t). As a result, theoretical predictions consistently overestimate effective relaxation times by several orders of magnitude compared to experimental observations. For example, long-term studies on MGs, polymers, and oxide glasses—including those by Duan et al.26, Zhao et al.5, Perez-De Eulate et al.9, and Corning Incorporated12—have shown that the measured relaxation times are several orders of magnitude shorter than NM-based predictions. These discrepancies highlight a critical limitation in current theoretical frameworks: the failure to completely incorporate nonlinear effects that dominate ultra-slow aging behavior.

This fundamental knowledge gap in glass physics has profound implications for Earth and planetary sciences. Natural glasses, such as obsidian, tektites, organic amber, and lunar glasses, are widespread in geological and extraterrestrial environments. They are often the only available amorphous records of thermal, impact, or volcanic events. However, some lunar glasses contain K or Pb at concentrations too low to produce measurable isotope signals27,28,29,30, while amber contains 14C but its short half-life (~5730 years)31 restricts dating to at most several tens of thousands of years, far shorter than the millions of years typically required. As a result, glasses with extremely low isotope abundances cannot be reliably dated using traditional radiometric techniques, which calls for the development of alternative dating methods. The continuous evolution of physical properties in these aging glasses suggests an alternative: a kinetics-based dating approach that estimates age through intrinsic structural relaxation dynamics rather than isotopic decay. Such a method could unlock the chronology of otherwise undatable glassy materials, providing new tools for reconstructing geological history, tracing planetary surface processes, and interpreting extraterrestrial sample returns.

In this study, we address these challenges by formulating an empirical equation that quantifies the effective relaxation time (τeff) of glasses in non-equilibrium aging regimes at deep sub-Tg temperatures. Through systematic analysis of diverse glassy materials—including Ce-based MG, fossilized amber, and lunar glasses—we demonstrate that their nonlinear relaxation dynamics can be unified through a single τeff, governed by aging temperature and material-specific fragility. The resulting empirical relation captures essential features of ultra-slow aging across multiple classes of glasses and reveals a universal behavior that serves as a kinetic fingerprint. Based on this framework, we propose a glass kinetics dating method, conceptually analogous to radioactive decay, in which τeff serves as a material-specific decay constant. This approach provides a quantitative chronometer for glassy materials, applicable across timescales spanning decades to billions of years.

Results

Glass kinetics decay method: nonlinear features of aging

The introduction of material time is crucial for understanding and analyzing the aging dynamics of glass14,15,18,19. In the special case where τneq(t) is constant, the material time ξ(t) scales linearly with the real time t, i.e., \(\xi (t)\propto t\). However, during aging process, τneq(t) typically increases with t, hence ξ(t) is nonlinear with t. Struik32 systematically studied the change of creep relaxation time τneq(t) with aging time t in glasses, and observed a power-law relationship between them, i.e., \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{neq}}}}}\left(t\right)\propto {t}^{\mu }\), where μ is the Struik shift factor. In this case, the material time is related to the aging time by a power law, i.e., \(\xi (t)\propto {t}^{1-\mu }\). And the overall relaxation function still remains a KWW form, i.e.,

where βeff = β(1−μ) is the apparent stretching exponent, τeff corresponds to the time when ϕ(t) decays to e-1, which represents a characteristic time scale of glass aging. In such case, the material time can be reconstructed as \(\xi \left(t\right)={\left(t/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)}^{1-\mu }\), and the Struik relation can be deduced as \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{neq}}}}}\left(t\right)={t}^{\mu }\times \,{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{1-\mu }/(1-\mu )\). The Eq. (2) suggests that even in nonlinear aging regimes, if the Struik relation is valid, the relaxation dynamics can still be described using a single effective time scale and a modified exponent. Even in systems where the Struik power-law relation does not strictly apply, the Eq. (2) can still provide an empirical approximation over finite time windows33,34,35. Consequently, the KWW function is generally applicable to relaxation in diverse glass systems, and even in other many-body interacting systems36,37.

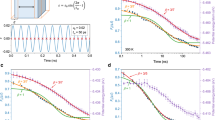

The broad validation of the KWW equation in modeling the aging dynamics of various glasses can be evidenced from the data collected in Fig. 1a. Metallic glasses such as Ce-based5, Pd-based6, and Zr-based7 glasses, as well as polymer glasses like poly(vinyl-chloride) (PVC)8, polystyrene (PS85K)38, polycarbonate (PC)38, and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)38, and silicate glasses12,39 have been shown to follow the KWW equation closely during their aging processes. In all cases, the initial glassy states were prepared by quenching from their supercooled liquids, and the as-cast samples were subsequently annealed isothermally below Tg. The temporal evolution of their physical properties, such as recovered enthalpy, hardness, creep modulus, fictive temperature, and strain, was then monitored during the approach toward equilibrium. Despite the different thermal histories and the diversity of measured properties, the KWW equation can accurately capture the kinetics of these changes, allowing for the determination of the non-equilibrium effective relaxation time τeff and the stretching exponent βeff. In Fig. 1b, by normalizing the aging time with τeff and βeff, all the decay curves can collapse into a single master curve. This collapse strongly supports the universality of the KWW equation in modeling the non-equilibrium aging kinetics of a wide range of glassy systems, irrespective of their composition or physical properties.

a Relaxation behaviors of various glassy systems are well captured by the KWW equation. These systems include metallic glasses (Ce-based5, Pd-based6, Zr-based7), polymer glasses (PVC8, PS85K38, PC38, PMMA38), and inorganic silica glasses12,39. The relaxation dynamics are extracted from diverse physical quantities, including recovered enthalpy, hardness, creep modulus, fictive temperature, and strain, measured under different aging protocols (the fitted values of τeff and βeff are listed in Supplementary Table 1). b By reducing the aging time with the non-equilibrium effective relaxation time τeff and the βeff index obtained in (a), the variations in different physical properties of various types of glass can be unified into a single master curve, demonstrating the effectiveness of the KWW empirical formula in describing the kinetic decay of relaxation.

Empirical equation for the decay of non-equilibrium glasses

To characterize the temperature dependence of the effective relaxation time (τeff) in aging glasses, we begin by reviewing existing theoretical models. Numerous phenomenological equations have been proposed to describe the evolution of equilibrium relaxation time τeq with temperature in supercooled liquids. The simplest is the Arrhenius equation \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{eq}}}}}={\tau }_{0}\exp \left[{E}_{a}/{RT}\right]\), where τ0 is the prefactor and Ea is the apparent activation energy. The Arrhenius equation only works for several strong glass-forming systems (like silica), but fails for most other systems where apparent activation energy Ea varies with temperature. To address this, various non-Arrhenius models, such as the VFT \({E}_{a}={BRT}/\left(T-{T}_{0}\right)\)20,21,22, parabolic \({E}_{a}=C{{RT}\left({T}_{0}/T-1\right)}^{2}\)23, and MYEGA \({E}_{a}={KR}\exp \left[C/T\right]\)24 have been developed. However, these models20,21,22,23,24 are only valid for equilibrium supercooled liquids and break down in the non-equilibrium glassy state.

A more general framework for modeling non-equilibrium glass involves the concept of fictive temperature (Tf), defined as the effective thermodynamic temperature at which a glass’s instantaneous properties match those of the equilibrium liquid40. During aging, Tf continuously decreases from the temperature that glass is frozen (Tg) toward the ambient temperature (T). The Narayanaswamy–Moynihan (NM) model18, 25 relates the growth of the instantaneous non-equilibrium relaxation time τneq(t) to the evolution of Tf(t), as:

where Eg is the activation energy around Tg, x is the weighting factor. And the τneq(t) in turn determines the decaying rate of fictive temperature Tf(t) and related physical properties p(t), i.e.,

Due to the inherent complexity of nonlinearity, obtaining an exact analytical solution for these equations is challenging. To make analytical progress, we provide an approximating solution under two assumptions: 1) the τeff is defined as the time when relaxation function decays to e−1 (i.e., \(\phi \left({\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)={e}^{-1}\)); 2) a simple KWW function can be used to approximate relaxation function \(\phi (t)\) near \(t={\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\), i.e. \(\phi (t)=\exp \left[-{\left(t/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)}^{{\beta }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}}\right]\) with βeff = β(1−μ). Consequently, the non-equilibrium relaxation time τneq(t) near \(t={\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\) could be deduced as a power law relationship \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{neq}}}}}\left(t\right)={t}^{\mu }\,{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{1-\mu }/(1-\mu )\). Combining these simplified equations with Eq. (3) and Eq. (4) yields the following equation:

where \({T}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}\left(t\right)=T+\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T\right)\exp \left[-{\left(t/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)}^{{\beta }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}}\right]\). In such case, an analytical solution for τeff can be deduced as \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}=\left(1-\mu \right){\tau }_{0}\exp \left[x{E}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}/{RT}+\left(1-x\right){E}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}/R{T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\right]\), where \({T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}={T}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}\left({\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)=T+\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T\right){e}^{-1}\) is the fictive temperature at \(t={\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\), and the parameter \(1-\mu={\left[1+\left(1-x\right){y}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\right]}^{-1}\) with \({y}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}=\beta {E}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\left({T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}-T\right)/R{T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}^{2}\). Considering that Eg is connected to fragility index m (i.e., \({E}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=m{{\mathrm{ln}}}\left(10\right)R{T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\)) and that \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}={\tau }_{0}\exp \left[{E}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}/R{T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\right]\), the non-equilibrium effective relaxation time of glass τeff can be reconstructed as

with \({T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}=T+\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T\right){e}^{-1}\) and \({y}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}=\beta m{{\mathrm{ln}}}\left(10\right){T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\left({T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}-T\right)/{T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}^{2}\). The upper limit of the τeff is related to the case of x = 1, i.e., \(\log \left[{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{{{{\rm{up}}}}}/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\right]=m\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}/T-1\right)\), which is a simple Arrhenius equation. Whereas the lower limit of τeff is related to the case of x = 0, i.e., \(\log \left[{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{{{{\rm{low}}}}}/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\right]=m\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}/{T}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}-1\right)-\log \left[1+{y}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\right]\). The lower limit of τeff has a limited value even at zero temperature, i.e., \(\log \left[{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{{{{\rm{low}}}}}\left(T=0\right)/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\right]=m\left(e-1\right)-\log \left[1+e\beta m{{\mathrm{ln}}}\left(10\right)\right] < m\left(e-1\right)\), indicating that glass aging could take place even at temperature far below Tg. More importantly, the fragility index m is crucial here, and it controls how fast the relaxation time increase as temperature decreases.

As an illustration, the evolution of relaxation time for these different models is compared in a Ce-based MG with a fragility of 40.9 (see Supplementary Fig. 1) and a Tg of 410 K. As shown in Fig. 2, the lower limit of the NM model, which accounts for the nonlinear effect, predicts a room-temperature relaxation time of 958 years. In contrast, the upper limit of the NM model, which neglects the nonlinear effect, predicts a room-temperature relaxation time of 50.3 billion years—longer than the age of the universe (13.8 billion years). Moreover, the coupling model (CM)33,41 predicts a room-temperature relaxation time of 1.28 million years, which is much longer than the prediction of the lower limit of the NM model. For the non-Arrhenius models (VFT, MYEGA, and Parabolic), the predicted relaxation time is even longer. These results highlight the significance of nonlinearity in understanding the non-equilibrium relaxation process, as it can effectively reduce the relaxation time of glass by tens of orders of magnitude. However, by observing the distinct enthalpy decrease during a 10.5-year aging process in experiments, the relaxation time of Ce-based MG at room temperature is estimated to be on the order of 101 years, which is much shorter than the predictions of all these models. Therefore, these existing theories are still inadequate for effectively evaluating relaxation time of glass.

Taking the present Ce-based MG with a fragility of 40.9 and a Tg of 410 K as an example, the τeff at ambient temperature is assessed using VFT20,21,22, MYEGA24, Parabolic23, NM models18,25, coupling model (CM)33, and our proposed empirical equation. The empirical equation yields a result of ~1.14 years, which is within the same order of magnitude as the age of Ce-based MG. In contrast, the other models significantly overestimate the τeff, resulting in values that are vastly different from the actual age of the glass.

To address this issue, an empirical formula was developed to effectively describe the τeff below Tg42: \({{\mathrm{ln}}}{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={{\mathrm{ln}}}{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}+A\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T\right)\), where τg is the relaxation time at Tg, and A is an unknown constant without any given physical meaning. For better comparison among different glass systems, the temperature can be normalized with Tg, and a new empirical formula can be developed:

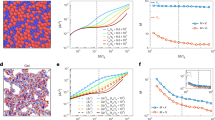

where w is a dimensionless constant. Actually, Hecksher and coworkers43,44 have proposed a single-parameter aging (SPA) ansatz, suggesting that the difference between logarithm of the aging rates in equilibrium and out-of-equilibrium is proportional to the temperature difference, which corresponds well to Eq. (7). As shown in Fig. 3a, the relationship between ln(τeff/τg) and (Tg − T)/Tg below Tg for different types of glasses is linear, with the slope varying depending on the type of glass. By multiplying the slope w by (Tg − T)/Tg, it is found that the τeff of all different types of glasses can be normalized onto a single master curve, as shown in Fig. 3b. This demonstrates the effectiveness of Eq. (7) in describing the τeff below Tg for different types of glasses. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3c, the slope w and the fragility m of various glasses show a good fit with the equation y = x, with a fitting degree of 94.7%. This indicates that the slope w in Eq. (7) can be approximated as the fragility value of the glass (w ~ m). Notably, as shown in Fig. 2, applying Eq. (7) to the Ce-based MG would produce a τeff of 1.14 years at ambient temperature. This value of τeff is of the same order of magnitude as the time showing distinct aging effects, more reasonable than the predictions by all other models. It indicates that the Eq. (7) can be effective and reliable even at ambient temperature.

a There exists a linear relationship between ln(τeff/τg) and (Tg − T)/Tg for different types of glasses4,42,57,65,66,67,68, and the slopes w of these glasses are different. b When (Tg − T)/Tg is multiplied by the slope w, it is found that all data can be unified onto a single master curve, indicating the effectiveness of Eq. (7) in describing the temperature dependence of relaxation times below Tg. c The relationship between the slope w of each glass in (a) and their fragility values61,69,70,71 is approximately linear and equal. d The τeff at ambient temperature for Ce-based MG (black solid square), amber (pink solid circle), and lunar glass (purple solid triangle) are predicted using Eq. (7), and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

Comparing the predicted age and the real age

To evaluate the validity of our model in describing long-term aging dynamics at ambient temperatures, we compare the predicted ages of the glasses with their known or independently estimated real ages. When using the equation \(\phi (t)=\exp \left[-{\left(t/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)}^{{\beta }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}}\right]\) to assess the age of glass at ambient temperature, the parameters βeff and τeff are essential as they determine the decay rate of the aging dynamics. At temperatures far below Tg, βeff has been consistently found to be approximately a constant value of 3/712,45. The ambient temperature τeff can be calculated using the empirical relation \({{\mathrm{ln}}}\left({\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\right)=w\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T\right)/{T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\), where w is approximately equal to the kinetic fragility m. By analyzing the variation of Tg under different heating rates, the fragility values of Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG, lunar glass, and amber were determined to be 40.9 ± 1.4, 45.8 ± 3.1, and 98.2 ± 4.6, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. 1). These values and their uncertainties are consistent with previously reported fragility measurements for MGs46, silicate glasses47, and polymers48.

The average annual ambient temperature at the storage location of Ce-based MG is ~288 K. Using this temperature, τeff at ambient temperature is estimated to be e17.4 seconds, or 1.14 years, as shown in Fig. 3d. Therefore, the relaxation function of Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG at ambient temperature is expressed as ϕ(t) = exp[−(t/1.14)3/7]. From the observed changes in the physical properties of Ce-based MG during aging, its corresponding age t can be determined. As shown in Fig. 4a, compared to the initial sample, the 10.5 years’aged Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG exhibits a more pronounced endothermic overshoot during the glass transition process, with the recovery enthalpy increasing from 1.1 J g-1 of the rejuvenated sample to 9.7 J g−1 of the aged sample. The recovery enthalpy of the aged sample is very close to the equilibrium value of recovery enthalpy. This yields a normalized relaxation value of ϕ ≈ 0.11. Substituting this into the relaxation function provides an estimated age of ~7.17 years (black solid square in Fig. 5a), which is reasonably close to the actual age of 10.5 years, confirming the model’s accuracy under ambient conditions.

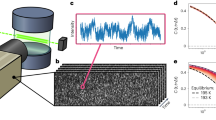

Since its preparation, the as-cast Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG has aged at room temperature for ~10.5 years, while the age of Baltic amber is between 35 and 50 million years49,50. Both the long-term aged a Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG and c amber exhibit a significant endothermic overshoot compared to their corresponding rejuvenated samples. b, d The XRD spectra of both long-term aged and rejuvenated samples show an amorphous state, and the insets show photographs of the two hyperaged samples.

The age of a Ce-based MG, b Baltic amber, and c Chang’E-5 lunar glass are estimated from the changes in their physical properties, according to the KWW decaying function \(\phi (t,{T})=\exp \left[-{\left(t/{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right)}^{{\beta }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}}\right]\) (τeff values are in Fig. 3d). The error bars in (a-c) represent the standard deviation. d shows the comparison between the actual age and predicted age. The black solid squares, red solid circles, and violet solid triangles represent the predicted ages of Ce-based MG, Baltic amber, and Chang’E-5 lunar glass, and Gorilla glass12 respectively, and the error bars in (d) indicate the confidence interval.

According to the official climate report issued by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management – National Research Institute (Poland), the national mean annual temperature in Poland is ~282.7 K. At this ambient temperature, the τeff of amber is e34.2 seconds, or about 21.6 million years (Fig. 3d). The corresponding relaxation function for amber at ambient temperature can be determined: ϕ(t) = exp[-(t/21.6)3/7]. As shown in Fig. 4c, the recovery enthalpy of the amber sample during the glass transition process increases from 3.02 J g−1 of the rejuvenated sample to 12.4 J g−1 of the hyper-aged sample. After approximation, a ϕ value of ~0.24 can be obtained. Substituting into the relaxation equation yields a predicted age of ~49.5 million years (red solid circle in Fig. 5b), which falls within the known age range of Baltic amber49,50. This consistency indicates that the long-term aging dynamics of amber confirm well to the kinetic model we established even at geological time scale.

At the Chang’E-5 landing site (~43°N, 52°W)51, the lunar surface temperature exhibits strong diurnal variations52. The temperature profile at this site is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 (data from ref. 52): nighttime temperatures are ~97 K with small fluctuations, whereas daytime temperatures rise to a peak of ~350 K. Using a trapezoidal approximation to the daytime segment, the average daytime temperature is ~286 K. Aging dynamics are exponentially sensitive to temperature. At the Chang’E-5 landing site, the average daytime temperature is ~189 K higher than the nighttime value. Therefore, the aging dynamics are expected to be dominated by daytime conditions, whereas the nighttime contribution can be neglected. At 286 K, τeff for the lunar glass during daytime is e36.9 seconds, or roughly 331 million years (Fig. 3d). The daytime aging dynamics function is therefore ϕ(t) = exp[-(t/331)3/7]. From this relation, the age of lunar glass is estimated to be approximately twice the daytime aging duration. According to ref. 13, the reduced modulus of two lunar glass samples increased from 48.5 and 56.8 GPa in their rejuvenated states to 84.2 and 85.6 GPa in their hyperaged states, respectively. From these modulus changes, relaxation function values of approximately ϕ ≈ 0.58 and ϕ ≈ 0.66 were obtained. Substituting into the kinetic model yields estimated ages of ~161 million and 86.0 million years, respectively. These values fall within the range of 2 million to 2 billion years as determined by isotopic dating methods30. The agreement between our predictions and radiometric age estimates suggests that the glass kinetics dating method provides a reliable alternative and is capable of cross-validation with traditional techniques.

Discussion

Despite the extensive research on glass aging, most studies have focused on relatively short timescales, typically less than a decade. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the relaxation dynamics of glass on such short timescales have been well characterized in both equilibrium and non-equilibrium regimes. In these regimes, relaxation times are shorter than approximately one year and can be described by fast relaxation modes such as α-relaxation, β-relaxation, and β′-relaxation. Extensive experimental data are available for these processes, supported by calorimetric, mechanical, and spectroscopic measurements33,53,54. In contrast, the aging dynamics over geological timescales, spanning millions to billions of years, remain largely unexplored. This gap defines a “no man’s land” in the relaxation map, where experimental data are scarce and conventional models fail to describe the ultra-slow dynamics of non-equilibrium glasses.

For relaxation times shorter than one year, both equilibrium and non-equilibrium states of glass can be experimentally accessed and characterized by fast relaxation modes such as α, β, and β′. However, in the non-equilibrium regime where the relaxation time exceeds one year, experimental data are extremely scarce and existing theoretical models fail to provide accurate descriptions, resulting in a “no man’s land” in the study of long-term glass aging. The image of lunar glasses is reproduced from Ref. 13 under a CC BY-NC license.

Our work addresses this gap by investigating the aging dynamics of three distinct types of long-aged glasses at ambient temperature: a Ce-based MG aged for 10.5 years, Baltic amber aged tens of millions of years, and lunar glass samples aged hundreds of millions of years. Our results demonstrate that, despite the inherent complexity and nonlinearity, the aging dynamics of these materials across different temperatures and timescales follow a general and predictable trend. Although the aging dynamics exhibit nonlinearity, the relaxation function can still be effectively characterized by a single timescale, τeff, which represents the effective relaxation time of the glass. Importantly, τeff is distinct from the equilibrium relaxation time τeq. While τeq is typically too long to be measured directly at temperatures far below Tg10,11,55, τeff is significantly shorter due to the nonlinearity of the aging process. This shorter timescale allows the aging effects to be observed and measured even at temperatures well below Tg.

According to our phenomenological model, the temperature-dependence of τeff can be described by the empirical relation: \({{\mathrm{ln}}}{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={{\mathrm{ln}}}{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}+w({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T)/{T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\), where w is the key parameter reflecting how rapidly the aging dynamics slow down with decreasing temperature. From this relation, the apparent activation energy of aging can be deduced as: \({E}_{{{{\rm{aging}}}}}\left(T\right)={wR}{T}^{2}/{T}_{g}\). This effective activation energy decreases as the temperature decreases and approaches zero as the temperature approaches absolute zero. These results are consistent with Simon’s discussion56 in 1931 that glass can never be completely frozen. The structural flow units responsible for aging remain active, even at temperatures far below Tg.

Notably, the parameter w plays a crucial role in determining the temperature dependence of τeff. As shown in Fig. 3c, w is closely related to the kinetic fragility m (w ~ m). And we have used the m value to replace w value in estimating τeff of these long-aged Ce-MG, amber, and lunar glass samples (see Fig. 3d). In this case, the uncertainty of m will transform linearly to that of lnτeff, and consequently to the estimated age. To quantitatively assess the sensitivity of lnτeff to m, we have performed an error propagation analysis. In our dating framework, the primary concern lies in the order of magnitude of the estimated age of the glass, which is governed by lnτeff. The relative uncertainties obtained from our measurements of m are 3.4%, 4.7%, and 6.9% for Ce-based MG, amber, and lunar glass, respectively. With this level of uncertainty, the corresponding uncertainties in lnτeff are ±0.4 for Ce-based MG, ±1.4 for amber, and ±2.2 for lunar glass, respectively. Propagating these uncertainties to the estimated ages gives an uncertainty of less than 50% for the Ce-based MG, while even for the more fragile amber and for lunar glass aged at lower temperature, the predicted ages remain within one order of magnitude. This demonstrates that the uncertainty in fragility does not affect the validity of our dating approach.

On the other hand, it is important to note that w can differ from m, particularly for strong glasses. For example, LaAlNiCu MG is stronger than other glasses in Fig. 3d, with the lowest value of fragility (m ~ 35)57. The w value is around 18, resulting in a w/m ratio of 0.514. This lower value of w/m in LaAlNiCu MG indicates a smaller activation energy and faster aging dynamics than expected. Similarly, fast aging dynamics have been reported in the Corning Gorilla Glass (Tg = 893 K) at room temperature ( ~ 293 K), with the measured relaxation time (τeff) of only 27.6 days12. In contrast, using the Mauro-Allan-Potuzak model58, Welch et al. estimated a room temperature viscosity of about 1022.25 Pa∙s for Gorilla glass, corresponding to a relaxation time of 19000 years12. Obviously, the measured aging dynamics there is much faster than expected. Given that the fragility m of Gorilla Glass is around 32, similar to that of LaAlNiCu MG, we assume a similar w/m ratio of 0.514. This yields an estimated w value of 16.5 for Gorilla Glass. According to our model, the room-temperature viscosity is ~1016.77 Pa∙s, corresponding to a relaxation time of 22.9 days. The close agreement between our predicted and measured relaxation times underscores the robustness of our approach in describing the non-equilibrium relaxation behavior of glasses across a wide range of conditions.

In addition to enhancing our understanding of ultra-slow relaxation dynamics, this framework also provides a practical method for dating glassy materials. By measuring their current physical properties, one can inversely deduce the age of glass samples. This kinetics-based dating approach represents an advancement in age determination and serves as a reliable alternative to traditional isotopic techniques, particularly for glass materials that are difficult to date using conventional methods. This method is highly flexible, as the relaxation time of glass materials can be systematically tuned by varying their composition and temperature. It is applicable to a wide range of glassy systems, including organic amber, MGs, and inorganic silicate glasses formed on the Moon or other planetary bodies, consistently providing reliable age estimates across diverse timescales. Furthermore, because it does not rely on radioactive content, this approach enables dating of materials with minimal or no isotopes, offering new insights into the geological histories of planetary surfaces such as the Moon and Mars. A typical example is the potential application of this method to determine the age of silk. In the past, the age of silk glass could only be inferred by observing changes in its kinetic properties to distinguish whether it was ancient or modern, without the capability to accurately predict its age59. Beyond such cultural heritage cases, the same framework can assess the long-term stability of optical coatings60, where refractive index drift affects performance, and monitor resistance drift in amorphous films for memory and sensing devices.

In summary, this study presents a comprehensive investigation into the long-term aging dynamics of diverse glassy materials. Based on the following assumptions: 1) the material time formalism with single-parameter aging, 2) a stretched exponential relaxation function for aging dynamics, and 3) the Struik’s power law relation between instantaneous relaxation time and aging time, we demonstrate that the nonlinear aging process can be effectively characterized by an effective relaxation time τeff, despite the inherent complexity and nonlinearity of aging. We further reveal that an empirical relation of \({{\mathrm{ln}}}{\tau }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={{\mathrm{ln}}}{\tau }_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}+w\left({T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-T\right)/{T}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) successfully captures the temperature dependence of τeff across various glass types, including MGs, Baltic amber, and lunar glasses aged under ambient conditions. The consistency between the predicted and observed relaxation times validates the reliability of this model and underscores the importance of nonlinear effects in glass aging. Beyond advancing our understanding of ultra-slow aging dynamics, our findings introduce a kinetics-based glass dating approach as a practical alternative to traditional isotopic methods, particularly for glassy materials with limited radioactive content. This method holds broad applicability across organic, metallic, and inorganic glasses, offering new opportunities for reconstructing the geological history of glass-bearing planetary materials and deepening our understanding of non-equilibrium aging behaviors.

Methods

Glass samples

We investigated three distinct types of glasses that had aged for different durations under ambient conditions: a Ce-based MG stored for ~10.5 years, Baltic amber aged for tens of millions of years, and lunar glass samples aged for hundreds of millions of years, returned by China’s Chang’E-5 mission. Specifically, the Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG was produced in 2013 and stored in a sealed plastic container under ambient conditions for 10.5 years. The inset of Fig. 4b shows a photograph of this Ce-based MG after 10.5 years. The sample developed a dark brown oxide layer on its surface, which was removed with sandpaper to reveal a shiny metallic luster. The inset of Fig. 4d shows the amber sample, which originates from Poland. The age of this Baltic amber is estimated to be between 30 and 50 million years49,50.

Thermal and structural characterization

To assess the degree of aging in each glass sample, the aged state was compared to its original state (corresponding to the case of t = 0). This can be achieved by heating the glass above the Tg, where it transitions into the supercooled liquid state, and then rapidly quenching it to ambient temperature10,11. This process rejuvenates the glass and recovers it to its initial state5. The aged Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG and amber samples were heated in a high-vacuum annealing furnace to a temperature 5 K above the end of the glass transition temperature (Tg) at a rate of 20 K min−1, held for 60 sec, and then furnace-cooled to room temperature to obtain rejuvenated samples (in initial state) with identical initial thermal histories. The thermodynamics of glassy samples was performed using Perkin Elmer DSC 8000 at a heating rate of 20 K min−1 under a purified argon atmosphere. The heat capacities (Cp) of amber and Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 MG were obtained by comparing with Cp of a sapphire standard sample. The amorphous structure of amber and Ce65Ga8Cu22Nb5 samples with different aging histories was confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a D8/ADVANCE diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV. The kinetic fragility (m) of different types of glass was measured using DSC to analyze the relationship between Tg and various heating rates. Samples were subjected to heating rates ranging from 5 to 150 K min−1, and the corresponding Tg values were recorded. By plotting the logarithm of the heating rates against Tg, the fragility parameter (m) for each type of glass was determined61,62.

Chang’E-5 lunar glass

The lunar regolith was scooped from the lunar surface in Chang’E-5 lunar exploration program. The lunar regolith sample numbered CE5C0400 was applied from China National Space Administration. The lunar regolith from the Chang’E-5 mission contains ~15 wt.% of glassy materials63, which formed due to the rapid cooling of basalt melted by meteorite impacts64. The Tg of lunar glass is taken from ref. 13. According to our previous results13, the glass obtained by cooling at 240 K s−1 approximates the glass initially formed by impact on the Moon and is regarded as the rejuvenated state of the lunar glass. The samples aged on the lunar surface over geological timescales are considered to be in a hyperaged state, and the reduced modulus values for rejuvenated and hyperaged states are measured in ref. 13.

Data availability

All data in this study are included in the manuscript, the Supplementary Information/Source Data file, or can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 410, 259–267 (2001).

Angell, C. A. Formation of glasses from liquids and biopolymers. Science 267, 1924–1935 (1995).

Dyre, J. C. Colloquium: The glass transition and elastic models of glass-forming liquids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 953–972 (2006).

Gallino, I., Shah, M. B. & Busch, R. Enthalpy relaxation and its relation to the thermodynamics and crystallization of the Zr58.5Cu15.6Ni12.8Al10.3Nb2.8 bulk metallic glass-forming alloy. Acta Mater. 55, 1367–1376 (2007).

Zhao, Y. et al. Ultrastable metallic glass by room temperature aging. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn3623 (2022).

Xue, R. J. et al. Characterization of flow units in metallic glass through density variation. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 123514 (2013).

Wang, D. P. et al. Structural perspectives on the elastic and mechanical properties of metallic glasses. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 173505 (2013).

Hodge, I. M. Physical aging in polymer glasses. Science 267, 1945–1947 (1995).

Perez-De Eulate, N. G. & Cangialosi, D. The very long-term physical aging of glassy polymers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 12356–12361 (2018).

Zhao, J., Simon, S. L. & McKenna, G. B. Using 20-million-year-old amber to test the super-Arrhenius behaviour of glass-forming systems. Nat. Commun. 4, 1783 (2013).

Pérez-Castañeda, T., Jiménez-Riobóo, R. J. & Ramos, M. A. Two-level systems and boson peak remain stable in 110-million-year-old amber glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 165901 (2014).

Welch, R. C. et al. Dynamics of glass relaxation at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 265901 (2013).

Chen, Z. Q. et al. Geological timescales’ aging effects of lunar glasses. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi6086 (2023).

Böhmer, T. et al. Time reversibility during the ageing of materials. Nat. Phys. 20, 1112–1117 (2024).

Riechers, B. et al. Predicting nonlinear physical aging of glasses from equilibrium relaxation via the material time. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9809 (2022).

Kohlrausch, R. Nachtrag über die elastische Nachwirkung beim Cocon und Glasladen. Ann. Phys. 72, 7–14 (1847).

Williams, G. & Watts, D. C. Non-symmetrical dielectric relaxation behaviour arising from a simple empirical decay function. Trans. Faraday Soc. 66, 80–85 (1970).

Narayanaswamy, O. A model of structural relaxation in glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 54, 491–498 (1971).

Dyre, J. C. Narayanaswamy’s 1971 aging theory and material time. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 114507 (2015).

Vogel, H. Das Temperaturabhängigkeitsgesetz der Viskosität von Flüssigkeiten. Phys. Z. 22, 645–646 (1921).

Fulcher, G. S. Analysis of recent measurements of the viscosity of glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 8, 339–355 (1925).

Tammann, G. & Hesse, W. Die Abhängigkeit der Viskosität von der Temperatur bei unterkühlten Flüssigkeiten. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 156, 245–257 (1926).

Elmatad, Y. S., Chandler, D. & Garrahan, J. P. Corresponding states of structural glass formers. Ii. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 17113–17119 (2010).

Mauro, J. C., Yue, Y., Ellison, A. J., Gupta, P. K. & Allan, D. C. Viscosity of glass-forming liquids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19780–19784 (2009).

Moynihan, C. T. et al. Structural relaxation in vitreous materials. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 279, 15–35 (1976).

Duan, Y. J. et al. Connection between mechanical relaxation and equilibration kinetics in a high-entropy metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 056101 (2024).

Zellner, N. E. B., Spudis, P. D., Delano, J. W. & Whittet, D. C. B. Impact glasses from the Apollo 14 landing site and implications for regional geology. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 107, 5102–5114 (2002).

Delano, J. W. et al. An integrated approach to understanding Apollo 16 impact glasses: Chemistry, isotopes, and shape. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 42, 993–1004 (2007).

Zellner, N. E. B. et al. Apollo 17 regolith, 71501, 262: a record of impact events and mare volcanism in lunar glasses. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 44, 839–851 (2009).

Long, T. et al. Constraining the formation and transport of lunar impact glasses. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq2542 (2022).

Taylor, R. E. & Bar-Yosef, O. Radiocarbon Dating: An Archaeological Perspective. (Routledge, 2016).

Struik, L. C. E. et al. Physical Aging in Amorphous Polymers and Other Materials (Elsevier, 1978).

Ngai, K. L. Universal properties of relaxation and diffusion in complex materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 140, 101130 (2023).

Lunkenheimer, P., Wehn, R., Schneider, U. & Loidl, A. Glassy aging dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 055702 (2005).

Evenson, Z. et al. X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy reveals intermittent aging dynamics in a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 175701 (2015).

Phillips, J. Stretched exponential relaxation in molecular and electronic glasses. Rep. Prog. Phys. 59, 1133–1207 (1996).

Vaknin, A., Ovadyahu, Z. & Pollak, M. Aging effects in an Anderson insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3402–3405 (2000).

Boucher, V. M., Cangialosi, D., Alegría, A. & Colmenero, J. Enthalpy recovery of glassy polymers. Macromolecules 44, 8333–8342 (2011).

Ryu, S. R. & Tomozawa, M. Structural relaxation time of silica glass as a function of fictive and holding temperature. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 89, 81–88 (2006).

Tool, A. Q. Relation between inelastic deformability and thermal expansion of glass in its annealing range. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 29, 240–253 (1946).

Casalini, R. & Roland, C. Aging of the secondary relaxation to probe structural relaxation in the glassy state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 035701 (2009).

Mei, J. N. et al. Structural relaxation of Ti40Zr25Ni8Cu9Be18 bulk metallic glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 357, 110–115 (2011).

Hecksher, T., Olsen, N. B. & Dyre, J. C. Communication: direct tests of single-parameter aging. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 241103 (2015).

Hecksher, T. & Niss, K. Single parameter aging and density scaling. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 194504 (2024).

Sun, Y.-T. et al. Distinct relaxation mechanism at room temperature in metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 14, 507 (2023).

Zhang, H.-R. et al. Fragility crossover mediated by covalent-like electronic interactions in metallic liquids. Mater. Futures 3, 025002 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. Revealing the relationship between liquid fragility and medium-range order in silicate glasses. Nat. Commun. 14, 13 (2023).

Kunal, K., Robertson, C. G., Pawlus, S., Hahn, S. F. & Sokolov, A. P. Role of chemical structure in fragility of polymers: a qualitative picture. Macromolecules 41, 7232–7238 (2008).

Czajkowski, M. J. Amber from the Baltic. Mercian Geol. 17, 86–91 (2009).

Penney, D. et al. Biodiversity of Fossils in Amber from the Major World Deposits (Siri Scientific Press, 2010).

Li, C. L. et al. Characteristics of the lunar samples returned by the Chang’E-5 mission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwab188 (2022).

Williams, J.-P., Paige, D. A., Greenhagen, B. T. & Sefton-Nash, E. The global surface temperatures of the Moon as measured by the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment. Icarus 283, 300–325 (2017).

Micoulaut, M. Relaxation and physical aging in network glasses: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 066504 (2016).

Yu, H.-B., Wang, W.-H. & Samwer, K. The β relaxation in metallic glasses: an overview. Mater. Today 16, 183–191 (2013).

Yoon, H. & McKenna, G. B. Testing the paradigm of an ideal glass transition in ultrastable polymeric glasses. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau5423 (2018).

Simon, F. et al. Über den zustand der unterkühlten flüssigkeiten und gläser. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 203, 219–227 (1931).

Zhang, T., Ye, F., Wang, Y. & Lin, J. Structural relaxation of La55Al25Ni10Cu10 bulk metallic glass. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 39, 1953–1957 (2008).

Mauro, J. C., Allan, D. C. & Potuzak, M. Nonequilibrium viscosity of glass. Phys. Rev. B 80, 094204 (2009).

Wang, J., Guan, J., Hawkins, N. & Vollrath, F. Structure and glass transition behaviour of silks. J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 20170883 (2018).

Ovshinsky, S. R. & Fritzsche, H. Amorphous semiconductors for switching, memory, and imaging applications. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 20, 91–105 (1973).

Zhao, Y. & Zhang, B. Evaluating the correlation between fragility and glass-forming ability in Ce-based metallic glasses. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 115107 (2017).

Brüning, R. & Samwer, K. Glass transition on long time scales. Phys. Rev. B 46, 11318–11322 (1992).

Zhang, H. et al. Size, morphology, and composition of lunar samples returned by Chang’E-5. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 65, 1–8 (2022).

Zhao, R. et al. Diverse glasses revealed from Chang’E-5 lunar regolith. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad079 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Hahn, H. Study of the kinetics of free volume in Zr45Cu39.3Al7Ag8.7 metallic glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 355, 2616–2621 (2009).

Fan, G. J., Löffler, J. F., Wunderlich, R. K. & Fecht, H. J. Thermodynamics, enthalpy relaxation and fragility of Pd43Ni10Cu27P20. Acta Mater. 52, 667–674 (2004).

Cangialosi, D., Boucher, V. M., Alegría, A. & Colmenero, J. Direct evidence of two equilibration mechanisms in glassy polymers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 095701 (2013).

Monnier, X., Cangialosi, D., Ruta, B., Busch, R. & Gallino, I. Vitrification decoupling from α-relaxation in a metallic glass. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay1454 (2020).

Park, E. S., Na, J. H. & Kim, D. H. Correlation between fragility and plasticity in metallic glass alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 031907 (2007).

Delbreilh, L. et al. Fragility of a thermoplastic polymer: influence of chain rigidity. Mater. Lett. 59, 2881–2885 (2005).

Cangialosi, D. Dynamics and thermodynamics of polymer glasses. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 153101 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 52325104 (B.Z.), 52571193 (Y.Z.), 52301214 (H.Z.) and 52271151 (Z.C.)), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no. 2021YFA0716302 (B.Z.)), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024B0101070001 (B.Z.)), the Bureau of Frontier Sciences and Basic Research, CAS (Grant no. QYJ-2025-01 (H.B.)), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, China (Grant nos. 2022A1515140115 (Y.Z.) and 2023A1515012598 (Z.C.)), and Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory (Grant no. SLZL01-03 (Y.Z.)). Y.Z. acknowledges the financial support of the Songhu Youth Scholar Program from the Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory. We acknowledge the fruitful discussions with Baoshuang Shang and Mingxiang Pan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and H.Z. contributed equally to this work. W.-H.W., H.B., and B.Z. supervised the project. W.-H.W., H.B., and B.Z. conceived and guided the research. Y.Z., L.X., and Z.C. conducted the experiments. Y.Z., H.Z., L.X., and R.Z. performed theoretical and data analysis. Y.Z., H.Z., B.Z., H.B., and W.-H.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jichao Qiao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Zhang, H., Xu, L. et al. Ultra-slow aging dynamics of glass and its application to geological dating. Nat Commun 16, 11631 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66472-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66472-7