Abstract

Optical fibers with integrated robotic microstructures are promising for cutting-edge applications. However, the development of microbots on a fiber system for synergistic sensing and actuation is challenging. Herein, inspired from natural Bobbit worm, we report a tactile gripper-on-a-fiber system that integrates wave spring, planar reflector with a scattering cone and a smart gripper on a single-mode fiber. The wave spring fabricated via two-photon polymerization of SU-8 can convert the applied micro-force into detectable stretching or compression, serving as a Fabry-Perot interferences sensor. Additionally, a pH responsive gripper with SU-8 frames and bovine serum albumin muscles is integrated with the wave spring, forming the tactile gripper-on-a-fiber system. As a proof-of-concept, the tactile gripper-on-a-fiber system was employed for micro-object sorting, flexible micro-block assembly, synergistic prey detection/capture, the measurement of Young’s modulus of zebrafish zygotes, and in-situ fetal movement monitoring, revealing great potential in biomedicine, precision manufacturing, minimally invasive and robotic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbots are miniature intelligent microsystems that consist of integrated sensing, actuation and control units1,2, holding great promise for cutting-edge applications in biomedicine3, precision manufacturing, minimally invasive and robotic surgery4. Unlike, conventional micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) based on silicon, microbots can be designed and fabricated using smart soft materials, revealing improved flexibility and biocompatibility3,4. At present, the development of microbots mainly resorts to advanced micro/nano manufacturing technologies and the development of smart materials, the former usually refers to self-assembly, 3D/4D printing, two-photon polymerization (TPP)5; and the latter relays on stimuli-responsive materials that can undergo reversible reconfiguration under external stimuli6. Based on this design principle, microbots with different functionalities have been successfully developed by combining advanced manufacturing protocols with various smart materials7. Correspondingly, microbots can be manipulated via different driving strategies including both physical signals such as light/magnetic/electric fields8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, and chemical stimuli such as moisture21, pH value4,7,22, different solvents23,24. For example, Xiong et al. presented a 4D-printed artificial heart composed of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM)-doped single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) hydrogel, which emulates the cardiac pulsation by programmable periodic light manipulation of the contractile-diastolic behavior of the structure9. To realize the magnetic manipulation of microbots, Xu et al. developed a poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogel doped with magnetic nanoparticles (MNP)3. The resultant micro-mechanical claw produced via TPP enables grasping and cell transfer with the help of magnetic field. Florea et al. reported the TPP fabrication of 4D microstructures based on a phenyl-boronic acid copolymer, which can be controlled by modulating sugar concentration23. In contrast to other chemical reagents, the use of sugar as a driving source may reduce the harm to organisms. Previously, we have developed an artificial musculoskeletal system based on bovine serum albumin (BSA) and SU-8 composite structures, demonstrating pH-responsive actuation capabilities7. The resulting microgripper exhibited exceptional dexterity in performing various manipulation tasks, including precise object grasping and controlled release operations. Nevertheless, despite the fact that soft microbots enable programmable shape morphing, their practical applications are fundamentally constrained by the lack of force feedback ability, which becomes critical for developing intelligent robotic systems2,3,25. The implementation of real-time force detection systems could yield multiple operational benefits, including enhanced dexterity in manipulating microscopic objects, minimized mechanical trauma to delicate biological structures13, more precise force regulation17, and adaptive responsiveness to dynamic environments4. These advancements collectively suggest that force feedback integration is essential for soft microrobots development. However, significant challenges remain in achieving high-density sensor integration with miniature soft robots while maintaining their inherent deformability.

Considering the limitations with respect to dimension and loading capacity, microbots with integrated perception and actuation capabilities cannot be developed by directly assembling sensing and actuating components together. Consequently, the manipulation, signal perception and feedback functions of microbots have to rely on their working platforms3,6. As a representative example, optical fibers that feature anti-electromagnetic interference26, small size, and biocompatibility, have emerged as a versatile working platform for microbots27,28,29,30,31,32. In the past decade, individual functional devices including sensors, actuators and imaging components have been successfully integrated with optical fibers, enabling signal perception33, mechanical operation34,35 and imaging36,37. For instance, the integration of sensitive microstructures on optical fibers makes it possible to detect multi-signals such as temperature38, pressure39,40, minuscule force41, humidness42 and pH value43. Unfortunately, these sophisticated sensors are incapable of mechanical manipulation. On the other hand, with the help of micro/nano fabrication technologies, squeezing and hydraulically driven mechanical microstructures have also been manufactured on fibers34,35, enabling on-demand actuation. Nevertheless, these fiber-based actuators lack the perception abilities for dynamic signal feedback and on-time adjustment. To date, the development of fiber microbots that permit both sensitive perception and robotic actuation remains a big challenge, because it requires an innovative combination of smart materials and their manufacturing technologies32.

Herein, inspired from natural Bobbit worm, we developed a tactile gripper-on-a-fiber (TGoF) system that enables both perception and actuation through multiple on-tip TPP fabrication process. The Bobbit worm, characterized by its elongated fibrous morphology, is a sophisticated marine ambush predator despite lacking eyes and the brain. It employs five cephalic antennae to detect the mechanical and biochemical cues. When triggered by prey movement, the organism executes explosive strikes from its sedimentary burrow, ensnaring targets with scissor-like maxillae44,45. The TGoF system that mimics Bobbit worm enables synergistic optical sensing and chemical actuation. Typically, it mainly consists of a wave spring, a planar reflector with a scattering cone and a smart gripper, as well as a single-mode fiber (SMF). The multi-layer wave spring on the tip of the SMF can converts the applied micro-force into detectable stretching or compression deformation, serving as a Fabry-Perot (F-P) interferences sensor. To prevent the influence from environmental light and the interference signals, a finely tuned scattering cone has been incorporated onto the upper plane. In addition to sensitive perception, a smart gripper with a pair of SU-8 frames and in-situ integrated BSA muscle is fabricated on top of the wave spring, forming the TGoF system. With the help of a coupled microfluidic chamber, the smart gripper can be manipulated via pH change, by which the expansion/shrinking of BSA muscle can trigger the grab/release operation. As a proof-of-concept, the TGoF system was employed for synergistic micro-objects manipulation and microforce sensing, for instance, the measurement of Young’s modulus of zebrafish zygotes and in-situ fetal movement. The TGoG system may hold great promise for future applications in biomedicine, precision manufacturing, minimally invasive and robotic surgery.

Results

Design, working mechanism and fabrication of TGoF system

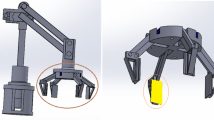

Inspired by natural Bobbit worm, a TGoF system that enables both perception and actuation is designed and fabricated. Figure 1a shows the basic design principle of the TGoF system, in which a circular base, a wave spring for minuscule force detection, a planar reflector with scattering cone for eliminating the interference of stary light (Supplementary Fig. 1-3, Supplementary Note 1), and a pH responsive gripper for on-demand manipulation are integrated on the tip of a SMF. With the flexible processing capabilities of the femtosecond laser46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, such a precise and complex 3D microstructure composed of different materials is produced by multiple and in-situ TPP fabrication (insets of Fig. 1a). To achieve microforce measurement, a multi-layer wave spring with a planar reflector is designed and fabricated based on SU-8, serving as a F-P sensor. Unlike conventional helical springs, the wave spring may have significantly enhanced mechanical stability and shock resistance. It can convert small stress into detectable stretching or compression, giving rise to the variation in cavity length (Fig. 1b). In this way, the applied microforce can be calculated through an intuitive spectral representation (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Note 2). More importantly, with the help of a smart gripper, our microforce sensor is workable in both stretching and compression states.

a The basic concept of bio-inspired TGoF system and the sensing/actuation structures. The insets are microscopic and SEM images of the microstructures. b Sensing principle of the wave spring-based F-P fiber sensor. c Driving principle of the pH-responsive smart gripper. d Schematic of the on-tip TPP fabrication process.

The smart gripper is manufactured using SU-8 as frameworks and BSA as pH responsive muscles, respectively. The SU-8 framework can guarantee the mechanical stability in different environments, and the BSA muscles can be dynamically actuated (swelling and shrinking) upon pH change. The cooperation of the musculoskeletal structure enables controllable gripping and release performance. The essential driving mechanism is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1c. Briefly, the BSA hydrogels mainly consists of amino acids, and the electrostatic repulsion of these functional groups dominates their volume. It is well known that the isoelectric point of BSA is about 4.77. In this condition, the electrostatic repulsion is the smallest, demonstrating a shrinking state. When the pH value decreases or increases, the BSA structure would possess positive or negative charges, respectively, leading to significant swelling due to the electrostatic repulsion. The reversible actuation of the BSA muscles make it possible to manipulate the gripper in a highly controlled fashion.

The in-situ fabrication of sensing and actuating structures on the tip of a SMF is realized through multiple TPP processes. To achieve the in-situ integration of the SU-8 structure, the SMF was fixed on a cover glass, where a microfluidic chamber was equipped (Fig. 1d). Consequently, the in-situ TPP fabrication and developing processes can be implemented on the stage. The first TPP fabrication was performed to manufacture SU-8 microstructures including the circular base, the wave spring and the reflector, as well as the gripper framework. To make the gripper smart, BSA muscles was integrated with the SU-8 framework by performing the secondary TPP fabrication. In this way, a robotic SMF equipped with a tactile gripper (TGoF) is developed.

Mechanical simulation of the wave springs

The sensing properties of the TGoF system primarily rely on the mechanical deformation of the wave springs. Consequently, the sensing performance can be optimized through reasonable modulation of the wave spring parameters. Figure 2a shows the design model of the wave spring, which consists of multi-layers of circular wave belts that stack together in a staggered manner. Detailed description of the correlation between the outer diameter (D1), the inner diameter (D2), the band height (h), the band thickness (t), the band number (N), and mechanical properties of the wave spring is provided in equation (S6) (supplementary information). To give a clear depiction of the TGoF system, a partially transparent model is shown in Fig. 2b, demonstrating the 3D configuration of the wave spring utilized in the mechanical simulation. To simplify the simulation process, we neglected the influence of the scattering cone and gripper on the mechanical properties of the spring. Since the sensitivity depends on the deformation of the wave spring under an equivalent load, we set a monitored point at the center of the planar reflector (underneath the scattering cone) to record the displacement.

a Design principle of the wave spring that consists of multi-layers of circular wave belts. b A partially transparent model of the wave spring employed in the finite element analysis. c Displacement simulation of the wave springs subjected to different stretching and compression loads, D1, D2, t and h of the wave spring are 80 µm, 75 µm, 1 µm and 10 µm, respective. d Dependence of the displacement on the applied loads in both stretching and compression processes. e Displacement simulation of the wave springs with different belt thicknesses under the same load. f Dependence of the displacement on the applied loads, in which the belt thickness of the wave spring varied from 0.5 to 2 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the finite element simulation, both stretching and compression states with different loads are measured, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2c, a comprehensive analysis on stretching and compression deformation of the wave spring are conducted under applied forces of 0.2 µN, 0.6 µN, and 1 µN, respectively. Notably, the displacement of each part of the wave spring can be well identified from the color distribution. The corresponding data diagram indicates that the displacement remains consistent under both stretching and compression states when subjected to the same load (Fig. 2d). According to equation (S6), varying the wave belt thickness (t) can tune the mechanical properties of the wave spring directly. In the following simulation, we tuned thickness (t) from 0.5 µm to 2 µm, while kept the applied loads for both stretching and compression at 1 µN (Fig. 2e). The dependence of displacement on load for wave springs of different belt thickness is shown in Fig. 2f. The decrease of belt thickness leads to a significant increase in displacement. In this regard, a relatively small thickness may give rise to much higher sensitivity. Nevertheless, considering the mechanical strength and the stability, when t is less than 1 µm, the resultant wave spring lacks sufficient structural strength to support the grippers. In this work, the band width and thickness of the wave spring are set to be 5 µm and 1 µm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Note 3). In addition, the influence of number of layers on the mechanical properties and the deformation under torsional force were also explored (Supplementary Fig. 6 and 7, Supplementary Note 4).

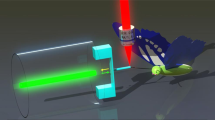

Microforce sensing

In the microforce sensing measurements, three wave springs with belt thicknesses of 1 µm (WS-1), 1.5 µm (WS-2), and 2 µm (WS-3) were fabricated and tested for comparison. To quantify the microforce applied to the sensor, a homemade system was constructed. Since commercial optical fibers feature standardized properties with known dimensions and Young’s modulus, we developed a custom microforce generator based on fiber optics for microforce calibration41. As shown in Fig. 3a, with the assistance of the precision measurement platform, the wave spring sensor can gradually approach the cantilever fiber. When the wave spring sensor pressed against the end of the cantilever fiber, the as-generated microforce can be fed back to the wave spring, leading to the compression. According to the length of cantilever fiber (Lfiber) and the displacement of the contact point (Δd), the load received by the sensor can be precisely calculated (equation S7), while the spectra shift of the F-P sensor can be recorded for calibration.

a Schematic diagram of the homemade microforce sensing system. The inset is the microscopic image of the contact region. b The evolution of the interference spectra of WS-1. c Dependence of wavelength shift on compression load, and the microforce sensitivity of WS-1 is fitted. d The evolution of the interference spectra of WS-2. e Dependence of wavelength shift on compression load for WS-2. f The evolution of the interference spectra of WS-3. g Dependence of wavelength shift on compression load for WS-3. The insets of c, e, and g are microscopic images of relative wave spring. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 3b–g show the evolution of the interference spectra and the microforce sensitivity of the three wave spring sensors. Generally, with the increase of the compression load, the cavity length decreases, and the interference spectra are blue shifted. In the case of WS-1, the interference spectrum shifted from 1547.6 to 1534.6 nm when the compression load increased from 0 to 42 µN (Fig. 3b). Linear regression analysis of the load and interference wavelength suggests a high correlation coefficient of 0.999 and a slope of −0.32, indicating a high sensitivity of −0.32 nm/µN (Fig. 3c). In sensing experiments of the other two wave springs, similar blue-shift effects are also observed (Fig. 3d, f). The microforce sensitivities with respect to WS-2 and WS-3 are −0.10 nm/µN and −0.03 nm/µN, respectively (Figs. 3e, g). By comparison, the microforce sensitivity decreases with the increase of belt thickness. Therefore, the mechanical characteristics of the wave spring can be precisely modulated to meet diverse requirements by tuning these structural parameters. Despite slender springs can lead to relatively higher sensitivities, large deformation may result in structural instability in practical force detection. Simultaneously, a substantial change in cavity length can induce a pronounced drift in the spectra, which hampers sensitivity demodulation. Considering the sensitivity, measuring range and stability, we chose WS-1 for the following experiments. Meanwhile, an exploration experiment is conducted on the relationship between the laser power and the sensitivities of the wave springs (Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Note 5). In addition to compression, the sensitivity of stretching process is also evaluated (Supplementary Fig. 9 and 10). Moreover, the microforce sensitivity of the F-P sensor is closely related to the refractive index of the environment. To meet the requirement in practical applications, the sensitivity in aqueous solutions of different pH value is also characterized (Supplementary Fig. 11, 12). Additionally, to assess the cyclic durability of the wave spring, we performed 200 loading cycles, which indicated reasonable stabilities of the TGoF system (Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Note 5). It is worthy pointing out that both the wave spring and the gripper fabricated via TPP may suffer from relatively high variability. To minimize such experimental differences, the laser processing parameters and developing conditions should be strictly consistent. Because the deformation of the wave spring is very small within a moderate load range, we employed a more flexible coil spring to visualize the stretching and compression process (Supplementary Fig. 14). When the coil spring (equipped with a disc) was compressed and stretched, its length change can be clearly identified. At the same time, the corresponding interference spectra show obvious blue or red shift (Supplementary Video 1). To evaluate the mechanical stability against bending torque, we investigated the deformation behavior of the wave spring theoretically and experimentally by applying a perpendicular force to the axis. Additionally, to verify the excellent stability of the wave spring, we designed and fabricated a helical spring array, and made a comprehensive comparison against bending torque (Supplementary Fig. 15–20, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Note 6).

Actuation of grippers

Soft microbots that feature flexible body yet controllable deformation are promising for developing fiber manipulators6,7. To endow the wave spring sensor with robotic actuation, we further fabricated a smart gripper based on a stiff/soft synergistic dual material system, in which the relatively stiffer SU-8 is used as supporting frameworks and pH responsive BSA is employed as muscle for gripper actuation. As shown in Fig. 4a, the expansion of the BSA in basic condition (e.g., pH = 13) can drive the gripping behavior, whereas the shrinking near isoelectric point (pH = 5) can lead to the release of the gripper. In TPP fabrication, the 3D model is first converted into point cloud data, where the scanning step length (SL) specifically denotes the spatial interval between two adjacent voxels within this dataset. critical parameters governing the power density received by photopolymer include laser power, single-point exposure duration, and scanning SL, which collectively determine the photopolymerization efficacy and final structural fidelity. When laser power and exposure time are fixed, the voxel dimensions remain constant. By adjusting SL to modulate the degree of voxel overlap, the density of the polymer network can be precisely controlled. To optimize the pH responsive property of BSA, we fabricated three BSA blocks by varying the SL from 200 nm to 100 nm, and investigated their volume change in aqueous solutions of three typical pH values (pH = 1, 5, and 13, Fig. 4b). Generally, the BSA microstructure fabricated using larger SL may have a much looser BSA network, demonstrating a relatively greater length swelling ratio (LpH=13/LpH=5, LpH=1/LpH=5). Additionally, for the structure fabricated using the same SL, the length swelling ratio between pH = 13 and pH = 5 is much larger than that between pH=1 and pH = 5. However, it is worthy pointing out that a larger swelling ratio cannot guarantee larger driving effect, since both the Poisson ratio and Young’s modulus are different. Therefore, the BSA muscles fabricated based on different SL are integrated with the SU-8 frameworks for further comparison. The resultant grippers and their responsiveness under different pH values are demonstrated in Fig. 4c. In acid condition (pH = 1), the BSA structure of 100 nm SL can drive the gripper clamping, whereas in basic condition (pH = 13), both grippers fabricated using 100 nm and 150 nm SL are workable. In the following experiments, we fixed the scanning SL of BSA at 150 nm for the gripper manipulation.

a Schematic illustration of the fabrication and actuation of the gripper. b Dependence of swelling ratio of BSA microstructures on SL. The insets are microscopic images of BSA blocks fabricated under different conditions and actuated under different pH values. c Microscopic images of grippers with different BSA muscles (SL = 100 nm, SL = 150 nm, SL = 200 nm) at pH=1, pH=5 and pH=13, respectively. d Schematic diagram of the microfluidic system for manipulating the gripper. e Photograph of the real microfluidic chip for the TGoF system. f Actuation of the gripper by switching the pH values. g Gripping the Y-shape structure. h Pulling the Y-shape structure through the closed gripper. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

By integrating the pH responsive gripper and the wave spring sensor with a SMF, the TGoF system formed. Figure 4f–h show the open/close manipulation of the gripper in aqueous solutions. To get better control over the environmental pH values, a tri-channel microfluidic chip was employed as the working platform (Supplementary Fig. 21, Supplementary Note 7), where the pH can be freely switched. Interestingly, when the initial pH value was ~5, and the gripper was fully open. By switching the environment to alkalinous solution (pH = 13), the gripper was closed (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Video 2). According to the quantitative responsiveness experiments, both the response and recovery time for the gripper is evaluated to be ~1.4 s (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Note 7). Additionally, to assess the cyclic durability of the pH-responsive gripper, we performed 200 actuation cycles, which confirmed the durability of the TGoF system (Supplementary Fig. 23, Supplementary Note 7). To explore the gripping force, a Y-shape structure with an original included angle of 36° was positioned at the center of the gripper (Fig. 4g). After switching the pH value to 13, the gripper clamped and pressed Y-shape structure. Consequently, the included angle decreased to 16° in 2.8 s (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Video 2). To represent the as-generated forces, a displacement-stress simulation of the Y-shaped structure was built (Supplementary Fig. 24, Supplementary Note 8), and the clamping forces is simulated to be ~1.5 μN (Supplementary Fig. 25). Additionally, in a passive process, the Y-shape structure was pulled through the closed gripper when the environmental pH was kept at 13 (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Video 2). Notably, due to the confinement of the gripper, the Y-shape structure deformed and propped open the gripper until passed through it.

Operation of TGoF system

At present, precise assembly of microstructures in a highly controlled fashion remains a challenging task, because it requires miniature yet complex sensing and actuation components that permit aiming, flexible gripping, installation, release, and the real-time perception of these processes55,56. To demonstrate the sensing and actuation capabilities of our TGoF system, we performed several operations including micro-objects sorting, flexible assembly of micro-building blocks, and perceivable hunting that mimics Bobbit worm. First, micro-objects of circular, triangular, and the square shapes are designed and fabricated for corresponding sorting (Fig. 5a). With the help of the piezoelectric platform, the tactile gripper successfully picked up these micro-objects and released them into the corresponding containers (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Video 3). In addition to flexible manipulation, non-invasive and sensitive interaction with the micro-objects is imperative55. Interestingly, the wave spring sensor also enable real-time microforce detection and feedback. In the assembly of micro-building blocks (Fig. 5c), the roof of the micro-castle anchored to the substrate was picked up by breaking the connecting wire, and the real-time stress change during this process was recorded by the TGoF sensor (Supplementary Video 4). As shown in Fig. 5d, with the increase of pulling displacement, obvious red-shift of the interference spectra can be observed. The dependence of the as-generated microforces on the pulling displacement shows that the breaking point appears at ~20 μm, and the breaking force of the connecting wire is ~127.7 μN.

a Schematic diagram of the micro-object sorting. b Video screenshots of the sorting process. This process was repeated three times to sort the three blocks. c Schematic diagram of the controllable assembly of the micro-building blocks. d Video screenshots of the roof-castle assembly. e The evolution of the interference spectra during the grasping of the roof from the substrate. f Dependence of the as-generated microforce on the displacement of the gripper. g Schematic diagram of the synergistic prey detection and capture process. h Video screenshots of fish detection and capture process. i The evolution of the interference spectra for the stress detection process. j The evolution of the interference spectra for the grasping process. k The corresponding microforce change on relative displacement, in which the displacement of gripper towards right is set as positive value. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Additionally, by mimicking natural Bobbit worm, the TGoF system also enables synergistic prey detection and capture by coupling an automatic pH switching system. Figure 5g shows the schematic illustration of the working mechanism, in which the threshold of microforce for the pH switch is set to be 80 µN. When the fish model gradually press the TGoF system, the as-generated force can be well recorded and calculated simultaneously. When the microforce exceeded the threshold (80 µN), the pH switch can be triggered and the gripper clamped the prey at once. Moreover, in the subsequent grasping process, the pulling tension can be also detected until the connecting wire anchored the fish model was broken (Supplementary Video 5). The evolution of the interference spectra in the prey detection and grasping processes, as well as the microforce change on relative displacement are shown in Fig. 5i–k, respectively.

Proof-of-concept applications of the TGoF system

The sensing and actuation abilities of the TGoF system hold great promise for cutting edge applications, for instance, the minimally invasive surgical intervention and endoscopic operation57,58,59. Nevertheless, the actuation process that usually involves acid or alkali solutions has imposed limitations on their practical applications in biomedical applications7. To address this issue, the gripper structure was re-designed, in which a replaceable gripper-based microprobe is proposed (Fig. 6a). The sensing microprobe can work in conventional physiological environment (pH = 7), and the probe tip can be replaced with other ones in alkali solutions. As shown in Fig. 6a, a series of microprobes of different sizes can be designed and fabricated for complex stress measurement. For instance, the microprobe equipped TGoF system can be employed for measuring the Young’s modulus of the zebrafish zygotes (Fig. 6b). In the practical operation, we demonstrated the installation of a microprobe of ~35 μm in length and 6 μm in diameter (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Video 6). According to the classical Hertzian contact model, the Young’s modulus of the cell can be measured by fitting the probe size, the indentation depth, and the corresponding microforce (Supplementary Fig. 26, Supplementary Note 9). When the SMF fixed on a high-precision stepper motor gradually approached and pressed the zebrafish fertilized zygotes, the displacement of the microprobe and the corresponding indentation of the zygote can be clearly observed (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Video 6). Meanwhile, obvious blue-shift of the interference spectra can be recorded (Fig. 6e). With the increase the relative displacement, the pressure on the wave spring increased, and the interference spectra regularly shifted to short wavelength. According to the sensitivity of the wave spring, the microforce subjected to the fertilized zygote can be deduced backwards. In this way, a model of indentation depth and microforce is constructed (Fig. 6g). By nonlinear fitting of indentation depth and microforce in equation (S9), the Young’s modulus of the fertilized zygote in the present case was measured to be ~0.103 MPa. In addition, the TGoF probe can also detect the fetal movement of an active embryo of Oryzias latipes (Fig. 6h). Notably, the heart beating and the seedling rotating of the embryo can be observed from the microscopic images. In the stationary state, the interference spectrum kept stable without fluctuation. When fetal movement occurred, the interference spectrum showed obvious red-shift (Fig. 6i, Supplementary Video 7). In terms of biological properties, previous results have confirmed that both BSA hydrogels and SU-8 photoresist demonstrate low immunogenicity and cytotoxicity, making them suitable for biomedical device fabrication60,61. These proof-of-concept applications suggest that the TGoF system holds great promise for future applications in the fields of micromanipulation, biomedicine, and surgical robotics.

a Schematic diagram of the installation of microprobes on the TGoF. b Schematic diagram of TGoF microprobe for the measurement of Young’s modulus of zebrafish zygotes. c Video screenshots of the microprobe installation. d Video screenshots of the Young’s modulus measurement of zebrafish zygotes. e The evolution of the interference spectra during the Young’s modulus measurement. f Dependence of the of interference spectra on the platform displacements. g The fitting dip wavelengths of Young’s modulus is obtained according to the classical Hertzian contact model, Ld is the indentation depth. h The use of TGoF microprobe in fetal movement monitoring. The insets are microscopic images of the embryo of Oryzias latipes before and after a fetal movement. i The variations of interference spectra before and after the fetal movement. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Generally, optical fibers can server as a multifunctional platform for microbots manipulation and perception, revealing great potential for developing robot-on-a-fiber (RoF) systems. Nevertheless, the integration of 3D micro/nano structures composed of various functional materials on the end face of optical fibers is challenging, because it involves both the development of smart material systems and nanoscale 3D additive manufacturing technologies. Consequently, to date, RoF systems with cooperative sensing and actuation capabilities are still rare. In this paper, inspired from the natural Bobbit worm, we designed and fabricated a TGoF system via multiple in-situ TPP fabrication processes, which primarily consists of a wave spring F-P interferences sensor, a pH responsive smart gripper and a SMF. The combination of micro-sensor and actuator on fiber tip enables the tactile gripping function. For the sensing part, a wave spring that functions as a microforce-sensitive F-P sensing cavity are fabricated at the tip of a SMF. Micro-stress applied to the wave spring can cause detectable stretching/compression deformation and thus change the length of the F-P sensing cavity, giving rise to the shift of interference spectra. In this way, imperceptible microforce can be quantitatively detected through an intuitive spectral representation. The micro-force sensitivity of the wave spring sensor can be further modulated by altering the wave spring parameters, for instance, the thickness and layers of circular wave belts. In the case of a moderate 6-layer wave spring, the microforce sensitivity can reach −0.32 nm/µN in the range of 0–42 µN. For the smart gripper, pH responsive BSA muscles are incorporated with the junctions of a rigid SU-8 fingers, enabling the on-demand gripping actuation with the help of a coupled pH switching chamber. The gripping behavior can be further controlled by tuning the laser scanning SL of the BSA muscles and the actuated pH values. The response time of the gripper used in this work is evaluated to be ~1.6 s.

To demonstrate proof-of-concept applications, the TGoF system had been employed for micro-object shorting, in which micro-blocks labeled with different shapes were picked up from substrate and released into the corresponding collecting containers. The on-demand picking up and release capability made it possible to assemble micro-building blocks into complex 3D nanostructures. In addition to the precise and controllable assembly, the real-time micro-force can be detected simultaneously, endowing the gripper with tactile feedback. In this way, an automatic prey detection and capture fiber that mimics Bobbit worm was developed. Furthermore, towards biomedical applications, the TGoF system with replaceable microprobes was re-designed for use in neutral aqueous solution. The Young’s modulus of the fertilized zygote was measured (0.103 MPa), and the fetal movement monitoring of an active embryo of Oryzias latipes was demonstrated.

The TGoF system demonstrates significant advancements in integrated sensing-actuation capabilities compared to state-of-the-art TPP-fabricated tactile sensors and microbots. As detailed in Supplementary Table 2 (Supplementary Note 10) comparing working platforms, materials, functionalities, sensitivity, and stability, current TPP-based microbots primarily employ glass substrates as the working platform, which limits their sensing performance. While existing micro-sensors on optical fibers or microfluidic chips enable multiparametric detection (microforce, pH, temperature, and refractive index), they lack dynamic actuation capacity. Our system innovatively integrates fiber-optic sensing structures with smart grippers, achieving synergistic integration of microforce sensing and dynamic actuation. This dual-functional design not only enhances operational flexibility and system integration but also overcomes the inherent limitations of standalone sensors or actuators.

While demonstrating notable advantages, the TGoF system exhibits discernible limitations compared to established silicon-based MEMS technologies62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. Although TPP enables multi-material 3D microfabrication, its production efficiency remains suboptimal relative to conventional MEMS manufacturing processes. Critical challenges in mass production, reproducibility, standardization, and cost-effectiveness present primary barriers to practical implementation. Furthermore, polymeric architectures display substantially inferior mechanical strength and durability compared to silicon-based counterparts, potentially limiting their reliability in high-stress operational environments. Nevertheless, the relatively low Young’s modulus and enhanced yield strength of photopolymers versus silicon62 confer distinct advantages for biomedical applications, particularly in minimizing risks of tissue trauma and inflammatory responses. Notably, recent advancements in processable materials and femtosecond laser processing systems suggest these limitations may be mitigated through high-throughput parallel manufacturing approaches. This technological evolution positions TPP as a promising candidate for advanced additive manufacturing applications, including but not limited to 3D micro-robotic systems, compliant sensory arrays, 3D microfluidic networks, and biointegrated implants. We anticipate that TPP-enabled miniaturized devices will emerge as complementary technologies to conventional silicon-MEMS platforms, particularly in emerging applications requiring complex 3D architectures and biocompatible interfaces, holding significant potential for advancing next-generation intelligent microsystems across multidisciplinary domains.

Methods

Preparation of pH-responsive BSA photoresist

BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, A7638) and methylene blue (MB, Sigma-Aldrich, M9140) were used as monomers and photoinitiators, respectively. 600 mg of BSA was added to 800 µL of MB solution (0.6 mg/mL). Then the mixture was incubated at 5 °C for 48 h to ensure complete dissolution of BSA. The pH solutions involved in the BSA actuation experiments are pH = 1 (0.2 mol/L HCL + 0.2 mol/L KCL), pH = 5 (0.1 mol/L NaOH + 0.2 mol/L potassium hydrogen phthalate), and pH = 13 (1.0 mol/L NaOH).

Fabrication of the SU-8 and BSA structures on a SMF

The fiberoptic stripper (CFS-3) and the fiber cleaver (FC-6T) were employed to precisely remove a portion of the SMF coating and neatly sever the tip. After being cleaned with alcohol and acetone, the SMF was horizontally positioned on a pristine cover-glass and securely affixed using UV curing adhesive. An appropriate volume of SU-8 (2075, NANO, MicroChem) photoresist was dispensed onto the tip of the SMF, followed by placing the entire assembly in a light-free constant temperature chamber at 95 °C for 1 h. The TPP processing system consists of a Fs laser source (Ti: the sapphire femtosecond laser oscillator with a central wavelength of 800 nm, a pulse width of 120 fs, and a repetition rate of 80 MHz), an oil-immersed objective lens (Olympus, ×60, numerical aperture: 1.4), a piezo stage (Physik Instrument), and a galvo scanning system (Sunny Technology). According to the pre-designed model, the laser spot was moved in the SU-8 photoresist in a strategy of the point-by-point and layer-by-layer polymerization to finally outline the complete structure. The laser power and SL are 12 mw and 200 nm, respectively. The processed SU-8 structure was subjected to a 30-minute curing process at 90 °C, followed by immersion in a developer for 20 min to facilitate the development.

In the secondary TPP process, the BSA photoresist was added to the SU-8 structure. Prior to the TPP processing of the BSA, the piezo stage was adjusted in order to ensure precise deployment of laser focus at a predetermined position. Subsequently, the same laser scanning strategy was employed to seamlessly integrate the BSA unit within its corresponding SU-8 frame. The SL for BSA was set as 100 nm, 150 nm, and 200 nm for different experiments, while the laser power is 18 mW. After completing the composite processing, the whole structure was immersed in distilled water for 5 h to remove the uncured BSA photoresist.

Simulation

The finite element simulation was performed in Comsol Multiphysics 6.0. In simulation models, the Young’s modulus, density and Poisson’s ratio of SU-8 were set to 4.8 GPa, 1200 kg m-3 and 0.26, respectively. Detailed modeling methods and parameter settings were reported in corresponding chapters and supplementary information.

Cells experiment

Zebrafish fertilized zygotes: One day after fertilization, the cells are fixated in a paraformaldehyde solution and stored at 11 °C in the dark.

Characterization

The detailed characteristics of samples were obtained using a field emission electron microscope (SEM, JSM-7500F, JEOL), with the current intensity and gold spray time set to 20 mA and 75 s, respectively. Meanwhile, the optical images were characterized by an inverted biological microscope (NIB410, with a 20 MP Sony Exmor CMOS Sensor). The optical fiber spectrum demodulator (GC-97001C-06-04, 1525–1568 nm) was self-built, and the scanning frequency is twice per second.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jager, E. W. H., Jager, E. W. & Inganäs, O. Microfabricating conjugated polymer actuators. Science 290, 1540–1545 (2000).

Rus, D. & Tolley, M. T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 521, 467–475 (2015).

Xu, H. F. et al. 3D nanofabricated soft microrobots with super-compliant picoforce springs as onboard sensors and actuators. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 494–503 (2024).

Xin, C. et al. Environmentally adaptive shape-morphing microrobots for localized cancer cell treatment. ACS Nano 15, 18048–18059 (2021).

Mainik, P., Spiegel, C. A. & Blasco, E. Recent advances in multi-photon 3D laser printing: active materials and applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310100 (2024).

Ma, Z. C. et al. Microfluidic approaches for microactuators: from fabrication, actuation, to functionalization. Small 19, 2300469 (2023).

Ma, Z. C. et al. Femtosecond laser programmed artificial musculoskeletal systems. Nat. Commun. 11, 4536 (2020).

Xin, C. et al. Light-triggered multi-joint microactuator fabricated by two-in-one femtosecond laser writing. Nat. Commun. 14, 4273 (2023).

Deng, C. S. et al. Femtosecond laser 4D printing of light-driven intelligent micromachines. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2211473 (2023).

Jia, Y. L., Zhu, Z. Y., Jing, X., Lin, J. Q. & Lu, M. M. Fabrication and Performance Evaluation of Magnetic Driven Double Curved Conical Ribbon Micro-Helical Robot. Mater. Des. 226, 111651 (2023).

Servant, A., Qiu, F. M., Mazza, M., Kostarelos, K. & Nelson, B. J. Controlled in vivo swimming of a swarm of bacteria-like microrobotic flagella. Adv. Mater. 27, 2981–2988 (2015).

Marino, H., Bergeles, C. & Nelson, B. J. Robust electromagnetic control of microrobots under force and localization uncertainties. IEEE T. Autom. SCI Eng. 11, 310–316 (2013).

Ullrich, F. et al. Mobility experiments with microrobots for minimally invasive intraocular surgery. Invest. Ophth. Vis. Sci. 54, 2853–2863 (2013).

Diller, E. & Sitti, M. Three-dimensional programmable assembly by untethered magnetic robotic micro-grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 4397–4404 (2014).

Kummer, M. P. et al. OctoMag: An electromagnetic system for 5-DOF wireless micromanipulation. IEEE T. Robot. 26, 1006–1017 (2010).

Pétrot, R., Devillers, T., Stephan, O., Cugat, O. & Tomba, C. Multi-Material 3D Microprinting of Magnetically Deformable Biocompatible Structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304445 (2023).

Tottori, S. et al. Magnetic helical micromachines: fabrication, controlled swimming, and cargo transport. Adv. Mater. 24, 811–816 (2012).

Rajabasadi, F., Schwarz, L., Medina-Sancehz, M. & Schmidt, O. G. 3D and 4D lithography of untethered microrobots. Prog. Mater. Sci. 120, 100808 (2021).

Vieille, V. et al. Fabrication and magnetic actuation of 3D-microprinted multifunctional hybrid microstructures. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000535 (2020).

Hu, X. H. et al. Magnetic soft micromachines made of linked microactuator networks. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe8436 (2021).

Lv, C. et al. Humidity-responsive actuation of programmable hydrogel microstructures based on 3D printing. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 259, 736–744 (2018).

Huang, T. Y. et al. Four-dimensional micro-building blocks. Sci. Adv. 6, eaav8219 (2020).

Ennis, A. et al. Two-Photon Polymerization of Sugar Responsive 4D Microstructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213947 (2023).

Zhang, Y. L. et al. Dual-3D femtosecond laser nanofabrication enables dynamic actuation. ACS Nano 13, 4041–4048 (2019).

Fusco, S. et al. An integrated microrobotic platform for on-demand, targeted therapeutic interventions. Adv. Mater. 26, 952–957 (2014).

Han, X. L. et al. Operando monitoring of dendrite formation in lithium metal batteries via ultrasensitive tilted fiber Bragg grating sensors. Light-Sci. Appl 13, 24 (2024).

Picelli, L., Van Veldhoven, P. J., Verhagen, E. & Fiore, A. Hybrid electronic–photonic sensors on a fibre tip. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1162–1167 (2023).

Mei, W. X. et al. Operando monitoring of thermal runaway in commercial lithium-ion cells via advanced lab-on-fiber technologies. Nat. Commun. 14, 5251 (2023).

Wei, H. M. et al. Two-photon 3D printed spring-based Fabry–Pérot cavity resonator for acoustic wave detection and imaging. Photonics Res. 11, 780–786 (2023).

Wang, R. L. et al. Operando monitoring of ion activities in aqueous batteries with plasmonic fiber-optic sensors. Nat. Commun. 12, 547 (2022).

Ran, Y. et al. Fiber-optic theranostics (FOT): interstitial fiber-optic needles for cancer sensing and therapy. Adv. Sci. 9, 2200456 (2022).

Bian, P. et al. Femtosecond Laser 3D Nano-Printing for Functionalization of Optical Fiber Tips. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2300957 (2024).

Williams, J. C., Chandrahalim, H., Suelzer, J. S. & Usechak, N. G. Multiphoton nanosculpting of optical resonant and nonresonant microsensors on fiber tips. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 19988–19999 (2022).

Power, M., Thompson, A. J., Anastasova, S. & Yang, G. Z. A monolithic force-sensitive 3D microgripper fabricated on the tip of an optical fiber using 2-photon polymerization. Small 14, 1703964 (2018).

Power, M., Barbot, A., Seichepine, F. & Yang, G. Z. Bistable, Pneumatically Actuated Microgripper Fabricated Using Two-Photon Polymerization and Oxygen Plasma Etching. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2200121 (2023).

Li, J. W. et al. Ultrathin monolithic 3D printed optical coherence tomography endoscopy for preclinical and clinical use. Light-Sci. Appl 9, 124 (2020).

Gissibl, T., Thiele, S., Herkommer, A. & Giessen, H. Two-photon direct laser writing of ultracompact multi-lens objectives. Nat. Photonics 10, 554–560 (2016).

Li, C. X., Liu, Y., Lang, C. P., Zhang, Y. L. & Qu, S. L. Femtosecond laser direct writing of a 3D microcantilever on the tip of an optical fiber sensor for on-chip optofluidic sensing. Lab a Chip 22, 3734–3743 (2022).

Xie, F. et al. Optimizing scanning trajectory for laser nanoprinting of micro-optical Fabry-Perot interferometer integrated on single-mode fiber end-face for gas flow sensing. Opt. Laser Technol. 175, 110762 (2024).

Shang, X. G. et al. Fiber-Integrated Force Sensor using 3D Printed Spring-Composed Fabry-Perot Cavities with a High Precision Down to Tens of Piconewton. Adv. Mater. 36, 2305121 (2024).

Zou, M. Q. et al. Fiber-tip polymer clamped-beam probe for high-sensitivity nanoforce measurements. Light-Sci. Appl 10, 171 (2021).

Zhang, S. Y. et al. High-Q polymer microcavities integrated on a multicore fiber facet for vapor sensing. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1900602 (2019).

Purdey, M. S., Thompson, J. G., Monro, T. M., Abell, A. D. & Schartner, E. P. A dual sensor for pH and hydrogen peroxide using polymer-coated optical fibre tips. Sensors 15, 31904–31913 (2015).

Pan, Y. Y. et al. The 20-million-year old lair of an ambush-predatory worm preserved in northeast Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 11, 1174 (2021).

Purschke, G. et al. Sense organs in polychaetes (Annelida). Hydrobiologia 535, 53–78 (2005).

Liu, S. F. et al. 3D nanoprinting of semiconductor quantum dots by photoexcitation-induced chemical bonding. Science 377, 1112–1116 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Light-driven magnetic encoding for hybrid magnetic micromachines. Nano Lett. 21, 1628–1635 (2021).

Zhang, Y. Z. et al. A Novel Multifunctional Material for Constructing 3D Multi-Response Structures Using Programmable Two-Photon Laser Fabrication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 202313922 (2024).

Zhang, Z. X. et al. Three-Dimensional Directional Assembly of Liquid Crystal Molecules. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401533 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Carbon-Nanotube-Coated 3D Microspring Force Sensor for Medical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 35577–35586 (2019).

Wen, H. J. et al. Great chiral fluorescence from the optical duality of silver nanostructures enabled by 3D laser printing. Mater. Horiz. 7, 3201–3208 (2020).

Ge, Z. X. et al. Bubble-based microrobots enable digital assembly of heterogeneous microtissue modules. Biofabrication 14, 025023 (2022).

Li, W. Y. et al. Laser nanoprinting of floating three-dimensional plasmonic color in pH-responsive hydrogel. Nanotechnology 33, 065302 (2021).

Fan, X. H. et al. 3D printing of nanowrinkled architectures via laser direct assembly. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9942 (2022).

Wang, L. L. et al. Multimodal bubble microrobot near an air–water interface. Small 18, 2203872 (2022).

Dai, L. G., Lin, D. J., Wang, X. D., Jiao, N. D. & Liu, L. Q. Integrated assembly and flexible movement of microparts using multifunctional bubble microrobots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 57587–57597 (2020).

Pinet, É. Saving lives. Nat. Photonics 2, 150–152 (2008).

White, D. C. et al. Endovascular interventional cardiology: 2015 in review. J. Interv. Cardiol. 29, 5–10 (2016).

Goh, H. K. C., Ng, Y. H. & Teo, D. T. W. Minimally invasive surgery for head and neck cancer. Lancet Oncol. 11, 281–286 (2010).

Sun, Y. L. et al. Dynamically Tunable Protein Microlenses. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 15, 1558–1562 (2012).

Chen, Z. Y. & Lee, J. B. Biocompatibility of SU-8 and Its Biomedical Device Applications. Micromachines 12, 794 (2021).

Arlett, J. L., Myers, E. B. & Roukes, M. L. Comparative advantages of mechanical biosensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 203–215 (2011).

Altintas, Z. Editorial for the Special Issue on Biosensors and MEMS-Based Diagnostic Applications. Micromachines-Basel 12, 229 (2021).

Zhang, D. D. et al. Fabrication and optical manipulation of micro-robots for biomedical applications. Matter 5, 3135–3160 (2022).

Barbot, A., Tan, H. J., Power, M., Seichepine, F. & Yang, G. Z. Floating magnetic microrobots for fiber functionalization. Sci. Robot 4, eaax8336 (2019).

Yang, X. P. & Zhang, M. L. Review of flexible microelectromechanical system sensors and devices. Nanotech Precis Eng. 4, 025001 (2021).

Lee, H. T., Seichepine, F. & Yang, G. Z. Microtentacle Actuators Based on Shape Memory Alloy Smart Soft Composite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2002510 (2020).

Stapf, H., Selbmann, F., Joseph, Y. & Rahimi, P. Membrane-Based NEMS/MEMS Biosensors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 6, 2120–2133 (2024).

Algamili, A. S. et al. A Review of Actuation and Sensing Mechanisms in MEMS-Based Sensor Devices. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 16, 16 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Y.-L.Z. acknowledgements support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant No. 2022YFB4600400; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. T2325014 and 62205174; the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province under Grant No. 20230101350JC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-X.L., Y.-Q.L., S.-L.Q. and Y.-L.Z. conceived the idea and designed the research. C.-X.L. and D.D.H. undertook the experiments and the characterization. C.-X.L. and Y.-L.Z. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Florent Seichepine, Yu Wang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, CX., Liu, YQ., Han, DD. et al. A tactile gripper on an optical fiber for perception and actuation. Nat Commun 16, 11513 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66575-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66575-1