Abstract

Crystallographic textures are a major determinant of the macroscale anisotropic properties of polycrystalline metallic alloys produced in a wide range of additive manufacturing (AM) processes. Here, we introduce a statistical method that can accurately quantify the degree of orientational order of textures despite the large random fluctuations in the orientation of individual grains inherent in AM processes. The method, demonstrated for laser and resolidification of AlSi thin films, extends Z-scoring to a dynamical regime to assess the statistical significance of observed textures compared to randomly generated ones at different stages of solidification. We further show that, combined with phase-field modeling, this method can be used to infer fundamental anisotropic properties of the solid-liquid interface that are essential for texture prediction, and are compared here to the results of atomistic simulations. In addition, phase-field modeling reveals that, even at rapid AM solidification rates, the observed 〈110〉-dominated textures in the AlSi thin films are controlled predominantly by the anisotropy of the interface free-energy and sheds light on the physical mechanism of grain competition. These results significantly enhance both the existing tools for the quantification and prediction of AM crystallographic textures and our basic understanding of their formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), particularly laser-based techniques like Powder Bed Fusion Laser Beam (PBF-LB) and Directed Energy Deposition (DED), has revolutionized the fabrication of complex metallic components, offering unprecedented design freedom and material performance1,2,3. These processes operate under extreme thermal conditions, including thermal gradients of 103 ~ 107 K/m4,5, solidification velocities ranging from 10−4 to 10 m/s4,6, and cooling rates as high as 108 K/s3,5,7. These extreme conditions often produce columnar or equiaxed microstructures with complex crystallographic textures that influence mechanical properties and macroscopic anisotropy3,8. However, the mechanisms governing grain texture selection under AM conditions remain poorly understood.

Grain texture evolution during solidification is generally controlled by the growth competition between grains of different crystallographic orientations. This competition selects grains with more favorable orientations at the expense of other grains with less favorable ones9. For columnar dendritic grain structures forming under slow solidification conditions, where the solid-liquid interface can be assumed to remain close to thermodynamic equilibrium, grain textures are primarily governed by the anisotropy of the solid-liquid interfacial free energy (γsl) that determines preferred dendrite growth directions10,11,12,13. For commercially important metallic alloys with cubic crystal symmetry, such as Al- or Ni-based alloys, 〈100〉 dendrite growth directions are commonly preferred, leading to 〈100〉 grain textures with 〈100〉 crystal axes preferentially aligned parallel to the heat flow direction. Compositional variations have also been observed to induce dendrite orientation transitions (DOTs) from 〈100〉 to 〈110〉 directions in some Al-based alloys, including AlZn14,15,16, AlGe17, and AlSm18. These DOTs have been interpreted theoretically using a two-parameter form of γsl predicted by atomistic simulations. While knowledge of preferred dendrite growth directions is an important prerequisite to predict grain textures, it is generally insufficient, since it does not predict which grains survive and which ones are eliminated. The classical minimum undercooling criterion of Walton and Chalmers19 assumes the growth of dendritic grains with the smallest growth undercooling, equivalent to the smallest misorientation between one of the 〈100〉 crystal axes and the heat flow direction, should be favored. However, this criterion alone does not predict how fast grains are eliminated. Several computational studies20,21,22 in a slow solidification regime have shown that, surprisingly, unfavorably oriented grains can sometimes survive and even outgrow favorably oriented grains. These studies have highlighted the limitation of the minimum undercooling criterion and identified various other factors than growth undercooling influencing grain competition, including neighboring grain bi-crystallography20,21 and microstructural length scales of dendritic grain structures22.

For columnar grain structures forming under rapid solidification conditions encountered in AM processes, where the solid-liquid interface can no longer be assumed to remain in local thermodynamic equilibrium, much less is known about what controls grain texture selection. Depending on the alloy type and growth conditions, the microstructure within each grain typically evolves from cellular/dendritic to weakly cellular to planar or banded as the solidification front velocity approaches and exceeds the absolute stability limit23,24,25,26,27. Textures obtained in AM specimens have been previously explained considering the dendritic primary growth direction and the contributions of the thermal gradient, solidification rate and melt pool shape8,28,29,30,31. Phase-field (PF) modeling studies at the melt pool scale have either focused on the computationally more tractable planar front case without cellular/dendritic microstructures32,33, or assumed a standard form of γsl with one anisotropy parameter that favors 〈100〉 dendrite growth directions34,35. In addition, to date, comparisons between predicted and observed cellular/dendritic grain textures have remained largely qualitative. As a result, some basic related questions have remained unanswered. Does the anisotropy of γsl, or the kinetic anisotropy known to influence dendrite orientations at rapid rates in undercooled melts36,37 control dendrite orientations under AM conditions? Are two anisotropy parameters essential for interpreting DOTs under slow solidification conditions14,15,17,18 adequate to predict preferred growth directions under rapid solidification? What is the underlying mechanism that governs the grain texture evolution?

Addressing these questions presents a major challenge. For the comparison of predicted and observed textures to be informative of preferred growth directions, the texture analysis needs to cope with the inherent stochasticity of the grain competition process, as well as large spatial variations of heat flow direction, which are both especially pronounced in AM processes. In a slow solidification regime where large columnar grains form with 〈100〉 or 〈110〉 crystal axes aligned preferentially with respect to a uniform thermal axis15,17, standard pole figures generally suffice to analyze grain textures and DOTs. However, under AM conditions, grain textures generally consist of a large number of grains with significant variations in growth orientation with respect to a thermal axis that itself varies around the melt pool. Furthermore, the number of grains decreases during solidification. This raises the central question of the present study of whether the comparison of predicted and observed textures can be made sufficiently quantitative to infer anisotropic crystal growth properties.

To address this question, and at the same time answer some of the basic questions raised above, we combine experimental and computational PF studies of pulsed-laser-induced melting and rapid re-solidification of thin films of AlSi alloys. By focusing on this quasi-2D geometry, we are able to use in situ imaging with Dynamic Transmission Electron Microscopy (DTEM), complemented by ex situ orientation mapping via TEM-based crystallographic mapping, to measure grain orientations with respect to the local thermal axis around the melt pool at different solidification times. We further introduce a new statistical method based on Z-scoring − Significance Analysis of Solidification Textures (SAST) − to quantify the observed textures. Here, the Z-score represents the number of standard deviations by which the observed grain alignment with the local thermal axis, or the axis perpendicular to it, deviates from its mean value for a distribution of randomly oriented grains. Importantly, the mean and standard deviation of this distribution are calculated as a function of the solid fraction with the same number (N) of actively growing grains as in an experiment or PF simulation, allowing us to assess the statistical significance of the observed textures at different stages of solidification despite the fact that N decreases with increasing solid fraction due to grain competition. Furthermore, using SAST together with PF modeling, we are able to infer both the anisotropic properties of the solid-liquid interface that govern the formation of the intra-grain cellular/dendritic microstructure, and the physical mechanism of the inter-grain growth competition that controls the grain texture. The results reveal that the anisotropy of the excess interface free-energy plays a dominant role even at rapid rates typical of AM processes and that grain competition is well-described by the classical Walton and Chalmers19 minimum undercooling criterion.

Results

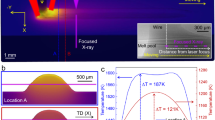

Pulsed-laser-induced rapid solidification of AlSi thin films by DTEM

In this work, we conducted pulsed-laser-induced rapid solidification experiments on AlSi thin films with homogeneous initial grain sizes and random textures. Thin films approximately 100 nm thick were investigated for three Si compositions: ~ 1 wt.%, ~ 3 wt.%, and ~ 6 wt.%, referred to as Al1Si, Al3Si and Al6Si, respectively. In situ imaging was performed during laser spot melting by DTEM, where the melt pool boundary at different times after the laser was turned off was tracked, as shown in Fig. 1a. Note that solidification does not start at laser shutdown, but the interface remains still for some time (called incubation time) until it starts moving towards the melt pool center. This has been previously reported by McKeown et al.38.Detailed data analysis was performed to estimate the major and minor ellipse semiaxes (\({a}_{e}^{0}\) and \({b}_{e}^{0}\)) and instantaneous solidification velocity (V) values with time. Further information regarding DTEM experiments and data analysis is found in Experimental methods. Fig. 1b presents V as a function of the solid fraction (by area) at various Si contents, together with fitted curves. This result demonstrates increasing V as the solid fraction increases, i.e., V increases with solidification time t towards the center of the melt pool, consistent with the findings reported by McKeown et al.38. Moreover, lower Si contents result in higher average V values. This trend can be attributed to the corresponding decrease in thermal conductivity, which varies from ≈ 215 Wm−1K−1 for Al1Si to ≈ 160 Wm−1K−1 for Al6Si at room temperature, according to the ThermoCalc® 2022b, TCAL7 database. The thin nature of the DTEM samples effectively eliminates convection, especially when the sample plane is perpendicular to gravity during the experiment. This prevents the formation of convection cells, minimizing disturbances, making solidification conduction-driven39. More detailed information about the DTEM set-up can be found in Ref. 40. Regardless of the level of Si content, average velocities consistently fall within the range of 0.5 ~ 2 m/s. These velocities align with the characteristic range of solidification velocities in AM, ranging from approximately 10−4 to 10 m/s4,6.

a Example DTEM results for an Al6Si thin film subjected to laser melting (energy of 2.34 μJ and dwell time of 50 μs). Images were captured at nine different time steps after the laser was turned off, with a step size of 2.5 μs. The largest melt pool trace is highlighted by a white dashed ellipse, and the melt pool trace at an example time step is depicted by a blue dashed ellipse. b Plots of solidification velocity (V) versus the solid fraction (defined in Supplementary Note 2) for three solute contents (Al1Si, Al3Si and Al6Si). The upper (solid symbols) and lower (open symbols) bounds correspond to the major and minor axes, respectively. Experimental data were estimated from DTEM experiments with laser energies ranging from 2.32 to 3.92 μJ, keeping a constant dwell time of 50 ns. c An IPF (out-of-plane direction Z) map obtained by TEM-based crystallographic orientation mapping (ASTAR) on an Al6Si DTEM thin film, where the approximate scanned area is denoted by a yellow box in subfigure a. The melt pool boundary is highlighted by a white dashed line, with the upper part of the map consisting of nanograins of near-random texture. Black lines highlight the grains, calculated assuming a 5∘ inner-grain misorientation threshold. Source data corresponding to solidification velocity measurements, crystallographic data and their corresponding analysis codes are provided as Source Data files.

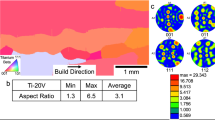

Ex situ characterization of grain textures by TEM-based orientation mapping

Ex situ TEM-based orientation mapping was performed to evaluate the crystallographic textures produced by the DTEM experiments; see Experimental methods for additional details regarding the mapping. For this analysis, only face-centered cubic (fcc) Al was considered. Two scans per chemical composition were conducted, where one of them was taken in the as-sputtered region and the other one was taken near the melt pool boundary. The former captures the orientations outside the melt pool edge, in the heat-affected zone, which is characterized by small, equiaxed grains of approximately random orientations. The characterization of the as-sputtered and the heat-affected zone can be found in Supplementary Note 4. An example of the latter mapping is shown by the Inverse Pole Figure (IPF) map corresponding to Al6Si, as shown in Fig. 1c, where grains are defined as regions with a maximum 5∘ inner-grain misorientation. Within the melt pool, the grains that evolve from the edge to the center appear columnar. Notice that at the late stage of solidification, only grains colored red, yellow, and green survive, while the blue grains are eliminated.

To gain a deeper understanding of grain texture evolution during rapid solidification, we analyze the crystallographic mapping data as a function of time (t) and Si amount. For each time step the solid-liquid interface is estimated to be an ellipse, following the procedure outlined in Supplementary Note 2. Since local orientations vary within the grain, the representative orientation at a given time step is determined by averaging the orientations over a 200 nm region from the solid-liquid interface (region with the red dashed line in Fig. 2a). For each filtered grain, a grain coordinate system, (X, Y, Z), is established. Here, X denotes the solidification direction, approximated as the vector perpendicular to the solidification front segment near the grain. The Y-axis represents the in-plane direction perpendicular to X, while Z denotes the out-of-plane direction (Fig. 2b). In addition, we introduce three key directions, ds[100], dp[010], and dp[011], which are illustrated in Fig. 2 and will be further defined in the next section.

a An IPF (out-of-plane direction Z) map for Al3Si at 15 μs. Black lines delimit grains calculated assuming a 5∘ inner-grain misorientation threshold. The green grain on the right is selected to highlight the coordinate system and variables. The red dashed line delimits the pixels near the solid-liquid interface selected for analysis. The gray box shows the area magnified in the panels on the right-hand side. The methodology explained in the main text is used to define, for every grain time-step, (b) the secondary [100] direction or ds[100] (red), (c) the primary [010] direction or dp[010] (blue) on the plane perpendicular to ds[100], and (d) the primary [011] direction or dp[011] (orange) on the plane perpendicular to ds[100]. The grain coordinate system (X, Y, Z) is shown in gray in panels (b–d). Crystallographic data and their corresponding analysis codes are provided as Source Data files.

Figure 3 shows IPF (out-of-plane direction Z) maps corresponding to varying levels of Si content and different solidification times. These maps feature cubes representing the orientation of each grain, particularly in the region proximal to the solidification front (see Experimental methods for its definition). Adjacent to each map is a set of pole figures representing the mean orientations of filtered grains. In these figures, the grain coordinate system (X, Y, Z) is utilized, whereby the mean grain orientations have been rotated to align the grain solidification direction (X) parallel to the horizontal direction. Spot size in the pole figures is proportional to the grain area, while spot color is determined by the mean grain IPF (out-of-plane direction Z). A more complete set of maps and pole figures, corresponding to a wider range of time-steps, is available in Supplementary Note 5.

IPF (out-of-plane direction Z) maps and corresponding (001), (110) and (111) Discrete Pole Figures are displayed for Al3Si (a–c) at the solidification time of (a) 0 μs, (b) 10 μs, and (c) 27.5 μs, and (d) for Al1Si at 17.5 μs and (e) for Al6Si at 37.5 μs. On the IPF maps, white dashed lines delimit the melt pool boundaries, while black solid lines represent grain boundaries. Pole figures are represented in the grain coordinate system; that is, the mean grain orientations have been rotated so the grain solidification direction (X) represented by black arrows is parallel to the horizontal direction. Spot size is proportional to grain area, and spots are mean grain IPF color. Only grains touching the solid-liquid interface are considered; the solidification front at each time step has been calculated considering the velocities in Fig. 1b. Crystallographic data and their corresponding analysis codes are provided as Source Data files.

The observations from Fig. 3a–c demonstrate the evolution of texture as solidification progresses. Prior to solidification initiation, the texture appears nearly random (Fig. 3a), characterized by a high prevalence of small, equiaxed grains that formed via the sputtering process. As solidification starts, some grains in contact with the melt pool boundary begin to grow epitaxially (IPF map in Fig. 3b), aligning approximately parallel to the heat flux. Even though the texture retains an appearance of randomness (pole figures in Fig. 3b), selective orientations begin to emerge. Towards the end of solidification (Fig. 3c), grain competition becomes evident, leading to the preferential selection of specific crystallographic orientations. The (100) pole figure illustrates that two directions belonging to the 〈100〉 family lie vertically, parallel to Y. Moreover, pole figures corresponding to the (110) and (111) planes show regions of higher intensity, indicating some directionality. Examination of the cube maps on the left indicates not all of the grains grew along their primary [010] directions, as traditionally reported41,42. In contrast, some of them exhibit [011]∥X alignment. Note that all of these directions are in-plane, consistent with the sample geometry17. Finally, analysis of these representations of rotated cubes for other Si contents (Fig. 3d, e) confirms the persistence of these trends.

Significance Analysis of Solidification Texture (SAST)

While the pole figures in Fig. 3 offer a qualitative visualization of grain texture, a more rigorous and quantitative approach remains needed to evaluate texture evolution. To address this, we developed a Significance Analysis of Solidification Texture (SAST) methodology (see “Methods”). SAST provides a systematic framework to quantitatively evaluate the alignment of grain orientations and their deviation from random orientations. This robust approach enables a comprehensive assessment of texture evolution across varying experimental conditions, ensuring greater precision and consistency in analysis.

For each grain in the sample plane that is still growing, we first pick (Fig. 2) one of the six principal 〈100〉 directions that has the largest projection onto the Y direction locally parallel to the solidification front, ds[100], and then subsequently pick the one among the 4 remaining 〈100〉 directions in the plane perpendicular to ds[100] that has the largest projection onto the X growth direction, dp[010], and the one among the four 〈110〉 directions in the same plane that has the largest projection onto the solidification direction, dp[011]. This choice of directions turns out to maximize statistical significance in comparison to other choices discussed in Supplementary Note 6. It is also guided by the pole figures (Fig. 3), which suggest that 〈100〉 directions are oriented preferentially parallel to the solidification front, as expected for typical 〈100〉 textures with secondary dendrite arms perpendicular to the growth direction. This is also visually apparent when examining the preferential orientations of the cubes for each grain (with six faces perpendicular to the 〈100〉 directions) in the left column of Fig. 3. As for the crsytallographic direction that is most aligned with the growth direction, the pole figures or the cube orientations are less clear, since they seem to contain a mix of directions close to 〈100〉 and 〈110〉 and other directions in between. This is different than what is expected for standard 〈100〉 textures dominated by primary dendrite arms growing along 〈100〉 directions. While 〈110〉 directions appear more frequently than 〈100〉, it is not clear that this difference is statistically significant. Therefore, while we expect 〈100〉 directions to be preferentially aligned parallel to the solidification front, a statistical analysis is required to confirm this expectation and to determine the preferred crystallographic growth directions.

To perform this statistical analysis, we compare, at different stages of solidification, whether the N grains that are still growing are preferentially aligned with the X and Y axes when compared to N randomly oriented grains. Taking N into account is important because N decreases in time due to grain competition, and statistical significance requires N to be sufficiently large. Since N is largest at the earliest stage of solidification, when grains are randomly oriented, it is not a priori obvious that N is still sufficiently large to reach statistical significance at later stages when the anisotropic growth competition of different grains has selected a texture. Our results below demonstrate there is a large window between the early and final stages of solidification, where grain competition has selected a texture and N is still sufficiently large to quantitatively assess its statistical significance. To measure the alignment of a collection of N grains, we sum over all grains the projections of the crystallographic directions of interest onto the local axes perpendicular and parallel to the solidification front, denoted by Yi and Xi for the ith grain, respectively, which yields the sums

This approach takes into account the large variation of orientations of the solidification front around the melt pool. For perfectly aligned grains along dα, Aα equals N for each α ∈ {s[100], p[010], p[011]}, while for randomly chosen grains, Aα is randomly distributed. This distribution is generally non-trivial for small N, as illustrated for N = 1 and As[100] = ds[100] ⋅ Y in Fig. 4a; it exhibits a constant frequency for values exceeding \(\sqrt{2}/2\), with a mean of 0.831 and a standard deviation of 0.1 as detailed in Supplementary Note 7. In the large N limit, however, the statistical distribution of Aα’s become Gaussian with a mean value that is proportional to N, albeit much smaller than N since different random projections cancel each other, and a standard deviation \(\sim \sqrt{N}\) is obtained as expected from the central limit theorem. This is illustrated in Fig. 4b that shows the statistical distributions of As[100] with increasing N with a perfect fit to a Gaussian distribution (solid black curve) for N = 29, where the values of N correspond to the grain textures of Fig. 3a–c at different stages of solidification.

a Alignment distribution of the random grain’s secondary [100] direction with respect to the Y-axis (ds[100] ⋅ Y). Mean value is 0.831, and standard deviation is 0.1. The distributions in panels a and b are generated from 10,000,000 randomly oriented grains, which are divided into 10 groups to calculate the standard deviations (SD) for each box. Data are presented as mean ± SD. b Random grain distribution for groups with various sizes (N). The crosses are experimental measurements of Al3Si at t = 7.5 μs (red), t = 20 μs (orange), and t = 30 μs (blue). The plus signs are values for perfect alignment, corresponding to the X-axis value of N. The black curve is the Gaussian function using the mean and SD obtained from the random distribution. The red, orange, and blue histograms correspond to the squares marked by the red, orange, and blue arrows, respectively, in the following panel c. Data are presented as mean ± SD (vertical black lines). c–e Evolution of experimentally estimated Z-scores (zs[100] zp[010] and zp[011], filled symbols) compared to Z-score values for perfect alignment (zs[100],pa zp[010],pa and zp[011],pa, open symbols); results correspond to: (c) zs[100] and zs[100],pa; (d) zp[010] and zp[010],pa; and (e) zp[011] and zp[011],pa. Refer to the main text for a detailed definition of these variables. The horizontal dashed black and dotted gray lines represent Z-scores of 0 and 1.96 (the critical value for statistical significance corresponding to the p-value of 0.05 for a two-tailed test); (f) number of analyzed grains versus solid fraction, as defined in Supplementary Note 2. Crystallographic data, SAST results and the corresponding analysis codes are provided as Source Data files.

We can now use the distributions in Fig. 4b to assess the statistical significance of the experimentally observed textures. For this, we superimpose as crosses the computed values of As[100] for the grain textures corresponding to Fig. 3a–c in Fig. 4b, and as pluses the values As[100] = N corresponding to perfect alignment. For the early stage corresponding to Fig. 3a, there are many grains (N = 29) that are randomly oriented. As a result, the measured value of As[100] falls well inside the distribution for randomly oriented grains and is far from the value for perfect alignment. For the intermediate stage of solidification corresponding to Fig. 3b, there are fewer grains left growing (N = 13), but the measured value of As[100] is now a few standard deviations outside the distribution for randomly oriented grains, moving closer to the value for perfect alignment. This trend continues to the later stage of solidification, where the measured value of As[100] remains statistically significant (i.e., outside the distribution for randomly oriented grains), even though the number of grains has decreased further (N = 5).

To further assess the statistical significance of the measured alignments at different stages of solidification, we use standard Z-scoring to quantify how much the experimentally measured Aα values deviate from the mean μα of random orientations, normalized by the standard deviation (σα): zα = (Aα − μα)/σα. The stage of solidification is measured as in Fig. 1b by the solid fraction, which increases in time from zero at the start of solidification to 1 at the end of solidification. The results are shown in Fig. 4c–e that compares the experimentally measured Z-scores to the values for perfect alignment with Aα = N (zs[100],pa, zp[010],pa, zp[011],pa) as a function of solid fraction. Figure 4c shows that zs[100] surpasses the threshold Z-score of statistical significance 1.96 for a large window of solid fraction comprised between the very early and late stages of solidification. This threshold Z-score corresponds to a small p-value of 0.05 for a two-tailed test, an indicator that the observations are not due to random chance. Note that any measurement with a corresponding Z-score for perfect alignment above 1.96 (corresponding to two grains) is statistically representative. This statistical significance confirms the aforementioned expected trend that ds[100] aligns with the solidification front (Y-axis). As solidification progresses, zs[100] approaches zs[100],pa, suggesting that grains with ds[100] aligned with Y increasingly dominate during grain competition. In contrast, Fig. 4d reveals that zp[010] consistently remains below 1.96 throughout solidification, showing no significant alignment trend with the X-axis. Figure 4e highlights pronounced alignment of dp[011] with the X-axis, supported by the zp[011] values that exceed 1.96 for most of the solidification process. However, toward the end of solidification, zp[011] falls below 1.96 due to a reduced number of surviving grains (Fig. 4f). Our analysis reveals clear trends in grain orientation evolution during solidification: [100] directions increasingly align with the Y-axis, while [011] directions align with the X-axis. These findings underscore the role of grain competition in texture evolution and validate the SAST methodology as a robust tool for quantifying texture alignment.

Notably, since the standard deviation of alignment scales with \(\sqrt{N}\), the Z-scores for perfect alignment of 1 and 2 grains are 1.69 and 2.39, respectively. Thus, the minimum number of grains required for statistical relevance is 2. However, this does not explain the decreases in zs[100] and zp[110] at the mid-to-late stage, when the number of grains is larger than 2. To evaluate the alignment of a single grain and to enable comparison of Z-scores across systems with different grain numbers, we normalize the Z-score using the corresponding value for perfect alignment: zα/zα,pa = (Aα − μα)/(N − μα). Supplementary Fig. 5 shows that the Z-score ratios for ds[100] and dp[110] steadily increase during solidification, except in the late stage. The late-stage deviation arises because the grain number decreases substantially below ~ 13, which is insufficient for reliably selecting preferential orientations during grain competition.

Phase-field modeling of dendritic structures

To elucidate the mechanism underlying experimentally observed 〈011〉 textures, we employed PF modeling to simulate the crystallographic texture evolution with the incorporation of the anisotropies of both the solid-liquid interfacial free energy (as) and atomic attachment kinetics (ak). For a solid-liquid interface with normal direction n, as(n) can be expanded using spherical harmonics Ki(n) (i = 1, 2), which are detailed in Supplementary Note 8:

Here, γ0 denotes the reference solid-liquid interfacial free energy, and ϵ1 and ϵ2 are anisotropy parameters. Previous studies on DOTs under slow solidification conditions for three-dimensional (3D) bulk materials demonstrate that a positive ϵ1 promotes 〈100〉-oriented growth, a negative ϵ2 enhances the 〈011〉 dominance, and a region of positive ϵ1 combined with negative ϵ2 favors a more complicated hyperbranched structure14,17,43. The kinetic anisotropy ak(n), governing interface mobility, is represented by one leading term:

where μk(n) is the anisotropic kinetic coefficient, \({\mu }_{k}^{0}\) is its isotropic reference value, and ϵk quantifies kinetic anisotropy strength. In 3D bulk materials, the positive ϵk promotes the 〈100〉 growth direction44, although in Al-based alloys at low solidification velocities, its impact is negligible compared with the influence of as14. Conversely, at very high solidification velocities, the effect of kinetic anisotropy becomes significant for dendrite orientations in undercooled melts36,37,45. However, the effects of as and ak in thin-film alloys remain unexplored. While their roles are well-characterized in bulk materials, confinement effects in thin-film geometries may alter the competitive dynamics governing texture evolution.

A challenge in capturing the crystallographic textures from rapid solidification experiments is accurately implementing 3D anisotropies in two-dimensional (2D) simulations. Our AlSi rapid solidification experiments were conducted on thin films with a thickness of approximately 100 nm. However, numerically resolving crystallographic textures at the melt-pool scale in 3D is computationally demanding for PF modeling. Therefore, we approximated the thin films as effectively 2D by assuming that the solid-liquid interface is essentially planar in the direction perpendicular to the film. In standard 2D implementations of γsl anisotropy, existing models reduce the problem to a simplified special case, aligning a [100] direction perpendicular to the sample plane20,23. This approach yields a four-fold symmetry expressed as a function of the misorientation angle α: \({a}_{s}=1+{\epsilon }_{4}\cos 4(\theta -\alpha )\), where ϵ4 is the anisotropy parameter and θ is the angle between the normal direction of the solid-liquid interface and the X-axis. However, this simplification fails to capture the complexity of crystallographic orientations, which are randomly distributed in 3D space. To address this limitation, we calculated as by projecting the interface normal vector n onto the intrinsic crystal coordinates. These projections were directly substituted into the explicit expressions for as(n) and ak(n), with randomly distributed orthogonal crystal axes defined in the laboratory frame (see Supplementary Note 8). This approach captures the full spectrum of possible crystallographic orientations that are essentially a mixture of two-fold and four-fold symmetry terms for the one-parameter anisotropy (Eq. 17 in Supplementary Note 8). Notably, our formulation recovers the conventional four-fold symmetry when [100] is aligned perpendicular to the sample plane and reduces to isotropic as when [111] is perpendicular to it. To simulate the crystallographic textures at the melt pool scale, we first used the commonly used one-parameter form of as, (ϵ1,ϵ2) = (0.06, 0), which is a generalization of the aforementioned simplified as forms. PF simulation results for a quarter melt pool are depicted in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 12, with the model details provided in the Phase field modeling section of Methods. Figure 5a and Supplementary Movie 1 show representative grain texture evolution characterized by rotated cubes that elucidate grain orientations. The grain texture exhibits a trend where, at the late stage of solidification, one of the 〈100〉 directions tends to align with the solidification direction. This observation can be confirmed by the Discrete Pole Figures (Fig. 5b), Density Pole Figures (Fig. 5c), and Density Pole Figures considering 4 simulations (Fig. 5d) at the solidification time of 15 μs, obtained following the same procedure as in experiments.

a Representative grain texture with 60 grain orientations shown by rotated cubes. b Discrete pole figures of panel (a) with grains that touch the solidification front at 15 μs only considered. c Density Pole Figures of panel (b). The color bar denotes Multiples of Random Distribution (MRD). d Density Pole Figure of 4 simulations. e zs[100] or Z-score of the projection sum of the secondary [100] direction on the Y- axis as a function of solidification distance. Blue squares correspond to the simulation shown in panel (a). Gray open circles, squares, and triangles correspond to experimental results for Al1Si, Al3Si, and Al6Si, respectively. The dotted line denotes a Z-score of 1.96, corresponding to the p-value at 0.05. f zp[010] or Z-score of the projection sum of the primary [010] direction on the X-axis. g zp[011] or Z-score of the projection sum of the primary [011] direction on the X-axis. h Number of grains within the melt pool shown in panel (a).

Grain texture evolution is further quantitatively analyzed through SAST. Figure 5e–g display three key Z-scores of simulation results, along with the experimentally measured Z-scores for Al1Si (open circles), Al3Si (open square), and Al6Si (open triangles). Figure 5e illustrates most of the zs[100] data points are below 1.96 (p-value of 0.05), suggesting statistically insignificance of ds[100]’s alignment with Y, different from experiments (Fig. 4a). In addition, Fig. 5f exhibits a window of zp[010] exceeding 1.96, in contrast to the experimental measurements of around 0 (Fig. 4b). This alignment indicates dp[011] tends to form a large angle with respect to the X-axis, which explains the negative zp[011] values of around − 1.96 (Fig. 5g). In addition, Fig. 5 h presents the grain number, which substantially affects Z-score values. This result demonstrates a large initial grain number, followed by a quick decrease to a level that agrees with the experiments.

The inability to replicate the experimentally observed grain texture using the one-parameter γsl anisotropy prompted us to calculate more realistic parameters for AlSi alloys. To achieve this, we conducted atomistic simulations for the solid-liquid interface evolution within a thin slab, using an angular embedded atom method (AEAM) interatomic potential for AlSi46. By employing the capillary fluctuation method (CFM)47, we determined the anisotropy parameters of dilute Al-Si alloys, revealing a shift toward the 〈110〉 region with increasing Si composition (Supplementary Note 9 and Supplementary Fig. 11), consistent with the trend observed in the AlSm alloys18. In this study, we selected (ϵ1,ϵ2) = (0.06, − 0.006) as the representative anisotropy parameters.

The PF simulation results are presented in Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 13, and Supplementary Movie 2. Figure 6a focuses on a representative grain texture for Al1Si, demonstrating a transition to [011] growth direction at late- stage solidification. The observed grain texture can be validated by the Pole Figures shown in Fig. 6b–d, produced following the same procedure as in Fig. 5. Specifically, in the (100) Pole Figure, a prominent high-density region is observed around the north pole, and in the (110) Pole Figure, a relatively high-density area is at the east. These characteristics underscore ds[100] predominantly aligns with the Y-axis, while dp[011] aligns with the X-axis.

a Representative grain texture with 60 grain orientations shown by rotated cubes. b Pole figures of panel (a) with the solid-liquid interface determined at the same position as the simulation at 15 μs. c Density Pole Figure of panel (a). d Density Pole Figure of 4 simulations. e zs[100] or Z-score of the projection sum of the secondary [100] direction on the Y-axis as a function solidification distance. Blue squares correspond to the simulation shown in panel (a). Gray open circles, squares, and triangles correspond to experimental results for Al1Si, Al3Si, and Al6Si, respectively. f zp[010] or Z-score of the projection sum of the primary [010] direction on the X-axis. g zp[011] or Z-score of the projection sum of the primary [011] direction on the X-axis. h Number of grains within the melt pool shown in panel (a).

To further quantify the grain texture evolution, we applied the SAST method. Figure 6e–g presents the Z-scores for the projection sum of ds[100] on the Y-axis (Fig. 6e), dp[010] on the X-axis (Fig. 6f), and dp[011] on the X-axis (Fig. 6g), for both PF simulations (blue square) and experiments (gray lines). Additionally, the number of grains in the simulations approaches those in experiments quickly after solidification starts (Fig. 6). Moreover, the Z-score ratio with respect to that for perfect alignment shows an increase for most of the solidification process, and the initial grains outside the melt pool is approximately 205.0 ± 83.7 nm (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). These simulation results demonstrate remarkable agreement with the experimental measurements, thus validating our PF model’s capability in capturing the grain texture evolution during rapid solidification of thin-film AlSi alloys.

Compared to γsl anisotropy, kinetic anisotropy plays only a minor role in texture evolution. To illustrate this, we performed two series of PF simulations. In the first, γsl was isotropic while kinetics were anisotropic. Supplementary Fig. 16 shows slight increases in Z-scores, but none reaching statistical significance, suggesting near-random orientation and only weak 〈100〉 trends. In contrast, the second series applied γsl anisotropy (ϵ1,ϵ2) = (0.06, − 0.006) with isotropic kinetics. Supplementary Fig. 17 reveals significant 〈011〉 alignment, matching the fully anisotropic case in Fig. 6. Together, these results confirm that while kinetic anisotropy promotes a conventional 〈100〉 texture, γsl anisotropy remains dominant in crystallographic texture evolution. Notably, the primary role of γsl anisotropy and the minor influence of kinetic anisotropy remain valid when the solidification velocity follows the experimentally measured profile (Fig. 1b) and the thermal gradient is increased to 5 K/μm (Supplementary Figs. 18, 19, and 20).

The grain textures observed in experiments and polycrystalline PF simulations (Figs. 4–6) can be well explained by the minimum undercooling criterion, which assumes that dendritic grains with the lowest tip undercooling are preferentially selected. To investigate the mechanism of texture formation, we performed single-crystal simulations with the principal axis rotating around the X, Y, and Z-axes (Fig. 7a). For (ϵ1, ϵ2) = (0.06, − 0.006), the tip undercooling Δ decreases monotonically for rotations around the Y-axis (orange line), but generally increases for other rotations. To explain more complex orientations in polycrystalline simulations, we further examined sequential rotations: a subsequent X-axis rotation after the initial Y-axis rotation (Fig. 7c) dramatically increases Δ. These behaviors align with the preferred 〈110〉 texture observed experimentally and in polycrystalline simulations at the same anisotropy parameters (Figs. 4, 6). In contrast, for (ϵ1, ϵ2) = (0.06, 0), X-axis rotations (blue line and cube in Fig. 7d) yield the smallest Δ, consistent with the preferred 〈100〉 texture observed in polycrystalline simulations at the same anisotropy parameters (Fig. 5). Notably, the rotation around the Y-axis for Al3Si also exhibits the minimum undercooling (Supplementary Fig. 21), indicating that the Si composition effect does not significantly affect the crystallographic texture evolution in PF simulations.

a Dendrite morphology for Al1Si with (ϵ1, ϵ2) = (0.06, − 0.006). b Dendrite tip undercooling Δ as a function of rotation angles of the principle axes around the X, Y, and Z-directions. Undercooling is defined as Δ = (Tl − Ttip)/(Tl − Ts), where Ttip is the temperature at the tip, Tl is the liquidus temperature at the nominal composition c∞, and Ts is the solidus temperature at c∞. For blue circles beyond 30∘, Δ was obtained using the output of the smaller-angle simulation as input. The open circle marks the unstable structure shown in panel (a). c Δ for a subsequent X-axis rotation after the initial Y-axis rotation (20∘ for light blue lines and 45∘ for bright blue lines). The dashed line denotes Δ without rotation. d Δ versus the rotation angles for (ϵ1, ϵ2) = (0.06, 0).

Discussion

The present study has introduced a SAST methodology to quantitatively characterize experimentally observed or simulated grain textures by statistically differentiating them from randomly generated textures at different stages of solidification. This approach complements traditional Pole Figures by evaluation through Z-score the statistical significance of preferred crystallographic orientations. While Pole Figures are informative in cases where textures are pronounced, the information they provide becomes more qualitative when statistical fluctuations in grain orientations are significant (Fig. 3). Such fluctuations can originate from a number of factors, including the strong variation in heat flow direction around melt pools, the inherently stochastic nature of the grain competition process20,48, and the characteristically small anisotropies of crystal growth properties in metallic alloys that may only weakly select certain growth orientations. In the present study, fluctuations or grain orientations are further enhanced by the fact that, prior to melting and solidification, deposited grains are randomly oriented in 3D space. As a result, even for the simplest form of cubic anisotropy of the interface free-energy \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})={\gamma }_{0}[1-3{\epsilon }_{4}+{\epsilon }_{4}({n}_{x}^{4}+{n}_{y}^{4}+{n}_{z}^{4})]\) in 3D, each grain has a different projected form of \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})\) in the 2D plane of growth, characterized by \({\gamma }_{sl}(\theta )={\gamma }_{0}[1+{A}_{0}{\epsilon }_{4}+{A}_{2}{\epsilon }_{4}\cos 2(\theta -\alpha )+{A}_{4}{\epsilon }_{4}\cos 4(\theta -\beta )]\), where θ is the angle between the directional normal to the interface (\(\widehat{n}\)) and a reference axis in this plane and where (A0, A2, A4, α, β) are different for each grain (Eq. 17 in Supplementary Note 8); the same holds true for the kinetic coefficient \({\mu }_{k}(\widehat{n})\). For a two-parameter anisotropy form of \(\gamma (\widehat{n})\) in 3D, the 2D projected form is even more complex and contains a six-fold component (Eq. 14 in Supplementary Note 8). Our results show that, despite the large fluctuations of grain orientations caused by these various factors, SAST is able to identify preferred textures in a statistically significant way for intermediate solidification stages with large enough Z-scores, when textures are indeed formed as in the present experiments (Fig. 4) and for some, but not all, of the simulated textures (Figs. 5, 6). In these cases, Z-scores typically fall below statistical significance at early stages of solidification, before grain competition has had time to select a texture, and sometimes at late stages when the number of grains that have survived this competition becomes too small. When no preferred textures are formed, Z-scores remain below or marginally close to statistical significance at all stages of solidification (Supplementary Fig. 16). As a first concrete application of SAST in the present context of thin films, our results demonstrate the method can be used to infer anisotropic crystal growth properties by the combination of simulation, experiment, and a comparison between the two. By comparing predicted and observed textures, we were able to conclude that the commonly used one anisotropy parameter form of \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})\) is insufficient to reproduce the specific experimentally observed texture with 〈100〉 and 〈110〉 directions aligned preferentially parallel and perpendicular to the solidification front, respectively (Figs. 4, 5). This observed texture, however, was obtained with a two-parameter anisotropy form of \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})\) (Fig. 6) with these parameters (ϵ1, ϵ2) predicted by atomistic simulations using an AEAM interatomic potential for AlSi alloys (Supplementary Note 9). This agreement suggests the anisotropy of \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})\) is a major determinant of grain texture in the present thin-film experiments. This expectation was further confirmed by additional simulations showing that, (i) if interface free-energy is chosen to be isotropic (\({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})={\gamma }_{0}\)), anisotropic interface kinetics alone does not suffice to generate a grain texture of clear statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 16), and (ii) the combination of isotropic interface kinetics and anisotropic \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})\) reproduces the observed texture (Supplementary Fig. 17). In a recent 3D phase-field study of a single laser track of 316L stainless steel, kinetic anisotropy was found to influence the grain texture in the central region of the melt pool32. However, this study was conducted in a velocity range beyond the absolute stability limit for this alloy, where the interface grows with a planar morphology and γsl was assumed to be isotropic. Our results indicate that the effect of kinetic anisotropy is less relevant below the absolute stability limit, even at relatively high velocities when cellular/dendritic structures, which are strongly affected by the anisotropy of \({\gamma }_{sl}(\widehat{n})\), are present. This is so even though the capillary undercooling ~ Γ/R, where Γ is the Gibbs-Thomson coefficient and R is the dendrite tip radius, and the kinetic undercooling V/μk can be estimated (using R ~ 50 nm measured from simulations23) to have comparable magnitudes of a few degrees K. Notably, these conclusions are drawn from 2D PF simulations, which approximate more realistic three-dimensional (3D) scenarios. The 2D model neglects the curvature of the solid-liquid interface through the film thickness, potentially influencing grain texture selection. Full-scale 3D polycrystalline simulations incorporating realistic film thicknesses (~ 100 nm) remain computationally prohibitive. In addition, the curvature of the interface along the film thickness is controlled by the interfacial excess free energies between solid/liquid AlSi and the substrate. These, together with the solid-liquid interfacial energy, determine the dihedral angle formed at the solid-liquid-substrate junction. These energies are not precisely known and are challenging to compute using MD simulations, making it difficult to realistically model film-thickness curvature effects. Despite these limitations, we believe the quasi-2D results presented here provide meaningful insights into grain texture selection relevant to applied AM processes, such as LPBF, which involve fully 3D melt pools. The fundamental mechanisms of grain competition under AM conditions, revealed through our quasi-2D simulations, support the broader applicability of these findings to a wide range of 3D AM processes.

The minimum undercooling criterion identified in our study for AM conditions assumes that cellular/dendritic grains with the lowest tip undercooling are preferentially selected, a mechanism traditionally used to explain grain competition under slow solidification rates19. In this framework, differences in dendrite tip undercooling cause unfavorable grains to lag behind and be eliminated by favorable grains. Our findings show that this criterion predicts remarkably well the selection of the 〈100〉 and 〈110〉 dominated textures for different forms of the anisotropy of the excess solid-liquid interface free-energy (Figs. 4–6). This suggests that the same criterion may be applicable to more general 3D geometries under AM conditions. Although the minimum undercooling criterion predicts which grain orientation is favored, it does not predict how quickly a well-oriented grain overgrows neighboring grains with larger undercooling. Additional studies, which extend recent studies of grain competition in a slow solidification regime21,22,48, are needed to address this question.

Method

Experimental methods

AlSi thin films with Si contents of ≈ 1, 3 and 6 wt. %, exhibiting homogeneous initial grain sizes and random textures, were used in this work. For the sake of brevity, alloys are referred to as Al1Si, Al3Si and Al6Si, respectively. Thin films, approximately 100 nm thick, were deposited onto amorphous, 0.25 × 0.25 mm wide, 50 nm-thick SiNX windowed TEM grids by DC magnetron sputtering. Sputtering was conducted in a chamber with a base pressure below 6.7 10−6 Pa, and the process pressure was 0.44 Pa. The main sputter target was Al1Si, run at a power of 300 W, with a secondary Si target to increase the Si content, run at a power of 25–75 W. Further information about the thin film fabrication process can be found in Refs. 38,49.

We carried out in situ laser spot melting and imaging experiments by movie-mode DTEM at 200 kV50. The thin films were melted by a pulsed Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm wavelength) with a Gaussian beam (1/e2 diameter of ≈ 135 μm), a deposited energy ranging from 2.32 to 3.92 μJ, and a dwell time of 50 ns. As detailed in other works51, after a certain delay time subsequent to the laser shut-off, a 2k x 2k CCD camera with single electron detection capability50 was used to capture nine consecutive elliptical low-magnification multi-beam bright-field TEM images of major and minor axes of ≈ 90 and 80 μm, respectively, and temporal resolution of 1-2.5 μs. Every nine-image series was recorded in a 256 × 256 pixel image file. Therefore, each experiment recorded images corresponding to a maximum duration of 22.5 μs. Because solidification was not always completed after such a period of time, up to three different laser hits were conducted per alloy system, varying the delay times from 0 to 40 μs to capture the entire solidification sequence. More details on the DTEM experimental procedures has been described in previous publications51.

We conducted detailed analyses of DTEM data by tracking the melt pool boundary, as shown in Fig. 1a, to estimate the major and minor ellipse semiaxes (\({a}_{e}^{0}\) and \({b}_{e}^{0}\)) as a function of time t. Note that the melt pool was ellipse-shaped, due to the non-perpendicular laser impact on the thin films during the experiments. Using the temporally resolved \({a}_{e}^{0}\) and \({b}_{e}^{0}\), we calculated instantaneous V and plotted them against solid fraction at various Si contents, as shown in Fig. 1b. We performed polynomial fitting of the scattered data in Fig. 1b using second-order polynomials and the least squares method.

We then performed ex situ TEM-based orientation mapping (NanoMEGAS® ASTAR) in a Philips CM300 FEG (S)TEM operated at 300 kV to evaluate the crystallographic textures produced by the DTEM experiments. Orientation maps were obtained by indexing electron diffraction patterns acquired with an electron probe size of 5–10 nm, with average confidence indexes (CI) above 0.25 (see Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Note 5 for values corresponding to each scan). Two ASTAR scans were conducted per alloy, in the as-sputtered regions (step size of 5 nm) and near the melt pool boundary (step size of 25 nm); only fcc crystal symmetry was considered. Spot sizes ranging from 3 to 50 nm were used, depending upon the mapped area. ASTAR data analyses were conducted on with Matlab® 2024a and the MTEX toolbax 5.8.052. The analyses of the maps near the melt pool boundary included an initial data cleaning step, in which (a) grains were generated, with a threshold of 1∘; (b) grains with equivalent diameters below 58 nm were deleted; (c) unindexed and deleted pixels were interpolated using the method of nearest neighbor; (d) the process was repeated and grains were recomputed. Subsequently, areas affected by orientation misindexing due to the 180∘ ambiguity problem, described in ref. 53, were manually identified and their orientation was interpolated, where each wrongly indexed pixel was assigned the mean orientation of neighbors belonging to the same grain. After cleaning, grains were generated with a threshold of 5∘.

Phase field modeling

We employed a multi-PF model extending from a previously established model designed for the rapid solidification of binary alloys23, in which far-from-equilibrium effects like solute trapping at the solid-liquid interface are quantitatively reproduced over an extremely wide range interface velocities from μm/s to m/s. Notably, this model distinguishes itself by obviating the need for introducing corrective anti-trapping currents, as typically required in other widely adopted models54,55, to mitigate the spurious solute trapping effect across the solid-liquid interface. Instead of employing corrective anti-trapping currents, our model incorporates a nonlinear solute diffusivity as a function of the PF (ϕ) within the interface region. This approach provides a more accurate representation of the physical phenomena under consideration. Furthermore, the versatility of this multi-PF model allows for the utilization of a larger interface thickness without compromising numerical accuracy. This feature substantially increases the grid spacing achievable during numerical simulations, thereby enhancing computational efficiency and reducing computational resource requirements.

The polycrystalline PF model employed in this study encompasses the evolution of both a Si concentration field, denoted as c, and M = 60 order parameters represented as ϕα with α = 1, 2, . . . , N and ϕα ∈ [ − 1, 1]. To simplify the experimental conditions while retaining the fundamental characteristics of the system, we applied the frozen temperature (T) approximation. This approximation defines the temperature, T, as a function of both solidification time, t, and solidification distance, x, and is expressed as follows: T = T0 + G(x − Vpt), where the pulling velocity, Vp, and temperature gradient, G, are aligned with the solidification direction. Here, T0 represents the initial temperature at the melt pool border.

The evolution equations governing the dynamics of ϕα and c

are derived based on the free-energy functional of binary alloys as detailed in Ji et al.23. Here, we take the choices of interface attachment time scale τ(n) = τ0as(n)2/ak(n), where \({\tau }_{0}={(S{W}_{0})}^{2}/(\Gamma {\mu }_{k}^{0})\), and interface width W(n) = SW0as(n). These choices are based on the general forms of the interfacial free-energy anisotropy γ(n) = γ0as(n) and kinetic coefficient anisotropy \({\mu }_{k}(n)={\mu }_{k}^{0}{a}_{k}({\bf{n}})\). Within these expressions, γ0 represents the reference value of interfacial free-energy, as(n) denotes the anisotropic strength of the interfacial free-energy, \({\mu }_{k}^{0}\) stands for the reference value of interfacial kinetic coefficient, ak(n) characterizes the anisotropic strength of the kinetic coefficient, n = ∇ϕ/∣∇ϕ∣ represents the unit vector normal to the solid-liquid interface, S serves as a computational coefficient for adjusting interface thickness, W0 denotes the physical interface width (approximately 1 nm), Γ = γ0Tm/L represents the Gibbs-Thomson coefficient, Tm denotes the melting point, and L stands for the latent heat of melting. Furthermore, the coefficients b and λ are given by b = lnke/2 and \(\lambda={a}_{1}^{0}b{m}_{e}S{W}_{0}/[\Gamma ({k}_{e}-1)]\), where ke is the partition coefficient, \({a}_{1}^{0}=2\sqrt{2}/3\), and me < 0 represents the liquidus slope. In addition, the interpolation function of the energy density is of a common form g(ϕ) = 15(ϕ − 2ϕ3/3 + ϕ5/5)/8, which ensures \({g}^{{\prime} }(\pm 1)={g}^{{\prime\prime} }(\pm 1)=0\) and g(± 1) = ± 1, thus allowing the free-energy density to attain local minima in the solid (ϕα = 1) and liquid (ϕα = − 1) phases.

In this study, we emphasize the anisotropy of the interfacial free-energy is critical to grain texture selection during rapid solidification of thin-film alloys. Using an angular embedded atom method (EAM) potential for AlSi in the molecular dynamics simulations, we have calculated the anisotropic parameters of γsl for the Si composition of interest (Supplementary Note 9). It is worth noting that Eq. (2) also applies to ak(n), with the distinction that the second-order term is absent. For comprehensive details regarding the implementation of as(n), please refer to Supplementary Note 8.

In Eq. (4), the term Dlq(ψ) represents the solute diffusivity across the solid-liquid interface. Here, Dl corresponds to the diffusivity in the liquid phase, ψ = − 1 + 2∑α(1 + ϕα)/2 serves as a mapping from ϕα to the overall liquid-solid interface. Additionally, the function q(ϕ) = 6(1 − ϕ) − 11(1−ϕ)2/4 (applicable only for S = 5) is introduced as a nonlinear function to mitigate the spurious excess trapping. Importantly, the variational derivation of the free-energy functional necessitates the replacement of g(ϕα) in Eq. (4) with g(ψ) because the interpolation function g(ϕ) is originally introduced to interpolate free energy between solid and liquid phases. However, when dealing with more than two order parameters, the stability of PF modeling dictates that g(ϕα) should be retained in the evolution equation of ϕα. Otherwise, a stable fixed point emerges at ϕα ≈ − 0.5, which is not physically valid, as there is no corresponding phase that exists at this point.

The final term in the evolution equation of ϕα shown in Eq. (4) accounts for the coupling between adjacent grains, with the positive value of ω representing a repulsive force. Assuming that ψ remains constant across the grain boundary, we can derive a unique expression for ω. To obtain this, we first consider the evolution equation for c. At equilibrium, integrating the right-hand side from − ∞ to x yields c = c∞eb[1+g(ψ)]. For the one-dimensional equation of ϕ, we multiply both sides by dϕα/dx and integrate from − ∞ to ∞. The resulting relation can then be solved by substituting c = c∞eb[1+g(ψ)] and using the constraint ψ = 1 + ϕ1 + ϕ2 = 1. Consequently, we obtain

Here c∞ denotes the nominal composition. Notably, this expression indicates that, due to ke < 1, the value of ω exhibits a linear increase with the undercooling (T − TM)/(∣me∣c∞). In particular, when the temperature aligns with the liquidus line at Tl = TM + mec∞ for the parameters listed in Table 1, we find that ω = 0.652.

The evolution equations were implemented in C/C++ within the CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) framework to leverage parallel computation. Simulations were performed on NVIDIA V100 or H200 GPUs in single precision to maximize computational speed and accommodate a larger number of phase fields. For a typical system size of 5120 × 5120 grid points, a single simulation on an NVIDIA V100 GPU required ~ 10 days of wall-clock time. Simulation data are processed using Python (3.9.6) codes.

Significance Analysis of Solidification Texture (SAST)

The elliptic/circular nature of the solid-liquid interface during thin-film spot melting hinders the interpretation of texture development as a function of time, as local solidification directions vary considerably for every grain. Here, we present a novel methodology to analyze the statistics of grain texture development during thin-film solidification: Significance Analysis of Solidification Texture (SAST). Even though the examples given in this section correspond to the experimental data, the same methodology has been applied to the modeling output.

Firstly, the coordinates of the experimental solid-liquid interface as a function of solidification time t were determined, as explained in Supplementary Note 2. Once these coordinates are known, the crystallographic map can be cropped accordingly to analyze the texture data for that specific time t. Fig. 2a shows a schematic diagram for Al3Si, where data within the solid-liquid interface for that time-step and data out of the melt pool boundary has been deleted. In the PF simulations, the solid-liquid interface at a specific time was determined using essentially the same method as in the experiments. Since the melt pool was assumed circular in PF simulations, the calculation can be simplified. In particular, we first identified the dendrite tip position at this specific time and then drew a circle at this position for the grain texture at the final solidification time. Next, for each time-step t, we delimited grains considering a maximum inner grain misorientation of 5∘, as described in refs. 56,57. In Fig. 2a, grains are delimited by black lines. For a solidification time t, only the grains in contact with the solid-liquid interface, not truncated by the crystallographic map boundaries, were selected for analysis. Details on how filtering was conducted can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

Once grain filtering was finished, we proceeded to analyze the texture data. In the schematic diagram in Fig. 2, some of the definitions introduced in this methodology are provided. Moreover, the green grain delimited by a thick black line in Fig. 2a will be used to define some of the most important variables by the panels on the right, Fig. 2b–d. For every selected grain, we filtered the data-points located at less than 200 nm from the interface, i.e., Di,j≤ 200 nm (refer to Supplementary Note 3 for a definition of Di,j), see area delimited by a dashed red line in Fig. 2a. Then, we calculated the mean crystallographic orientation (in matrix notation) and centroid coordinates of the selected region: O and (xc, yc), respectively. The reason why the data contained in the whole grain was not considered for the calculation was to avoid artifacts in the calculation associated with experimental orientation gradients, detected as the distance from the melt pool boundary increased, as observed in the same figure by the changes in Inverse Pole Figure (IPF) color within individual grains.

For every grain, the grain coordinate system, (X, Y, Z), was defined. The solidification direction vector X was approximated as the vector perpendicular to the tangent to the section of the solidification front near the grain. The considered section of the solid-liquid interface included any interface point within a 500 nm distance from the centroid (xc, yc). Note that, according to previous works in the literature where thin sample geometries were utilized, dendrites are expected to grow in-plane, as impingement with the sample border forces dendritic arms growing out of the plane to either cease growth or change their growth direction17. The two remaining directions of the grain coordinate system were defined as follows: Y was defined as the in-plane direction perpendicular to X and Z was defined as the out-of-plane direction, see Fig. 2b.

Utilizing this new coordinate system can be useful to estimate the primary and secondary dendrite growth directions. However, to further elucidate trends, a more quantitative and general methodology is needed. In Fig. 2b we defined the secondary [100] and [113100] directions (unit vectors ds[100] in the crystal coordinate system, denoted by red arrows), which are the growth directions of the secondary arms, as those 〈100〉 crystallographic directions (d<100>) with the largest projection onto the Y-axis in absolute value, i.e., the largest d<100> ⋅ Y. Note that previous investigations have shown that secondary arms of dendrites undergoing DOT are not necessarily perpendicular to the dendrite trunk, which is parallel to the X15,17; confirmation of this assumption would imply additional TEM analysis. Nevertheless, this definition allows for systematic assessment of texture development.

In the plane perpendicular to ds[100], the potential primary [010] and [011310] directions (unit vectors dp[010], denoted by blue arrows) are defined as those 〈100〉 directions (d<100>) with the maximum projection onto the X-axis, i.e., the greatest d<100> ⋅ X. Similarly, the primary [011] and [113111310] (unit vectors dp[011], denoted by orange arrows) are chosen from the 〈011〉 family (d<011>) having the largest projection onto the X-axis, i.e., the greatest d<011> ⋅ X. Considering two possible primary directions allows us to assess which one is more probable, or whether intermediate growth directions may occur. Alternatively, for a specific grain i, these directions can be defined so that their projections onto Xi or Yi satisfy:

Using these directions, we defined the overall alignment of N grain orientations, illustrated in Eq. (1), quantified the statistical alignment of grains compared to random distribution via Z-scores. Specifically, Z-scores are given by zα = (Aα − μα)/σα, where α ∈ {s[100], p[010], p[011]}, and μα and σα represent the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of Aα for randomly distributed grain orientations. Explicitly,

A Z-score measures the number of standard deviations a given data point lies from the mean. In this work, the sum of the projections of the selected growth directions have been selected to quantitatively evaluate the grain orientations of a whole texture.

Finally, for every alloy and time step, the Z-scores for perfect alignment (zs[100],pa zp[010],pa and zp[011],pa) were calculated. This was achieved assuming Y was perfectly aligned with ds[100] vector for every grain and X was perfectly aligned with dp[010] or dp[011] vectors for every grain. These Z-scores were calculated as follows:

Statistics and reproducibility

A large number of random grain orientations (ranging from 100,000 to 1,000,000), each defined by three orthogonal unit vectors (see Supplementary Note 8 for details), were generated to compute alignment distributions for N randomly oriented grains and the corresponding Z-scores (Figs. 4–6). The projections of these orientations were grouped into sets of N data points, discarding any remainder. Within each group, the N projections were summed to obtain As[100] values. The large number of random orientations ensures statistically robust estimates of the mean and standard deviation of As[100] used in Z-score calculations. For the alignment distributions shown in Fig. 4a, b, alignment values were binned into 20 intervals, and the random orientation generation process was repeated ten times to compute mean frequencies and standard deviations for each bin.

The statistical significance is represented by the Z-score, which quantifies the deviation of an experimental or simulated measurement of the alignment from the mean of the random-orientation distributions. The Z-score is therefore not associated with standard error. In Figs. 4–6 and other Supplementary Figures., each Z-score corresponds to a single measurement encompassing all grains within a given texture. Because alignment is computed as the sum of grain-orientation projections, increasing the number of grains reduces stochastic uncertainty. Accordingly, for the four simulations shown in Supplementary Figs. 12A, 13A, and elsewhere in the Supplementary Information, Z-scores were calculated using all grains in the alignment analysis, and thus do not yield standard errors for the reported values.

Data availability

All raw data and codes used to reproduce the results in this study have been deposited in Figshare58. The DOI link of this dataset is https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30460382.v2. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Guo, N. & Leu, M. C. Additive manufacturing: technology, applications and research needs. Front. Mech. Eng. 8, 215–243 (2013).

King, W. E. et al. Laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing of metals; physics, computational, and materials challenges. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2, 041304 (2015).

Herzog, D., Seyda, V., Wycisk, E. & Emmelmann, C. Additive manufacturing of metals. Acta Materialia 117, 371–392 (2016).

Sabau, A. S. et al. Fluid dynamics effects on microstructure prediction in single-laser tracks for additive manufacturing of in625. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 51, 1263–1281 (2020).

Hooper, P. A. Melt pool temperature and cooling rates in laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 22, 548–559 (2018).

Hagenlocher, C. et al. In process monitoring of the thermal profile during solidification in laser directed energy deposition of aluminium. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 3, 100084 (2022).

Hofmeister, W. & Griffith, M. Solidification in direct metal deposition by lens processing. Jom 53, 30–34 (2001).

Hagihara, K. & Nakano, T. Control of anisotropic crystallographic texture in powder bed fusion additive manufacturing of metals and ceramics-a review. Jom 74, 1760–1773 (2022).

Kurz, W., Rappaz, M. & Trivedi, R. Progress in modelling solidification microstructures in metals and alloys. part ii: dendrites from 2001 to 2018. Int. Mater. Rev. 66, 30–76 (2021).

Langer, J. S. Chance and matter. In Proc. Les Houches Summer School, Session XLVI (North-Holland Amsterdam, 1987).

Kessler, D. A., Koplik, J. & Levine, H. Pattern selection in fingered growth phenomena. Adv. Phys. 37, 255–339 (1988).

Karma, A. & Rappel, W.-J. Numerical simulation of three-dimensional dendritic growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4050 (1996).

Karma, A. & Rappel, W.-J. Quantitative phase-field modeling of dendritic growth in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. E 57, 4323 (1998).

Haxhimali, T., Karma, A., Gonzales, F. & Rappaz, M. Orientation selection in dendritic evolution. Nat. Mater. 5, 660–664 (2006).

Gonzales, F. & Rappaz, M. Dendrite growth directions in aluminum-zinc alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 37, 2797–2806 (2006).

Zhao, Y., Liu, K., Hou, H. & Chen, L.-Q. Role of interfacial energy anisotropy in dendrite orientation in al-zn alloys: A phase field study. Mater. Des. 216, 110555 (2022).

Becker, M., Dantzig, J., Kolbe, M., Wiese, S. T. & Kargl, F. Dendrite orientation transition in alge alloys. Acta Mater. 165, 666–677 (2019).

Wang, L., Hoyt, J. J., Wang, N., Provatas, N. & Sinclair, C. W. Controlling solid-liquid interfacial energy anisotropy through the isotropic liquid. Nat. Commun. 11, 724 (2020).

Walton, D. & Chalmers, uB. The origin of the preferred orientation in the columnar zone of ingots. Trans. Metall. Soc. AIME 215, 1 (1959).

Tourret, D. & Karma, A. Growth competition of columnar dendritic grains: A phase-field study. Acta Mater. 82, 64–83 (2015).

Pineau, A., Guillemot, G., Tourret, D., Karma, A. & Gandin, C.-A. Growth competition between columnar dendritic grains–cellular automaton versus phase field modeling. Acta Materialia 155, 286–301 (2018).

Dorari, E., Ji, K., Guillemot, G., Gandin, C.-A. & Karma, A. Growth competition between columnar dendritic grains–the role of microstructural length scales. Acta Materialia 223, 117395 (2022).

Ji, K., Dorari, E., Clarke, A. J. & Karma, A. Microstructural pattern formation during far-from-equilibrium alloy solidification. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 026203 (2023).

Ji, K., Clarke, A. J., McKeown, J. T. & Karma, A. Microstructure development during rapid alloy solidification. MRS Bull. 49, 556–567 (2024).

Ji, K., Zhong, M. & Karma, A. Phase-field model of alloy solidification far from chemical equilibrium at the solid-liquid interface. Phys. Rev. Res. 7, 033128 (2025).

Tourret, D. et al. Morphological stability of solid-liquid interfaces under additive manufacturing conditions. Acta Mater. 250, 118858 (2023).

Liu, P. et al. Investigation on evolution mechanisms of site-specific grain structures during metal additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 257, 191–202 (2018).

Thijs, L., Kempen, K., Kruth, J.-P. & Van Humbeeck, J. Fine-structured aluminium products with controllable texture by selective laser melting of pre-alloyed alsi10mg powder. Acta Mater. 61, 1809–1819 (2013).

Vrancken, B., Thijs, L., Kruth, J.-P. & Van Humbeeck, J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of a novel β titanium metallic composite by selective laser melting. Acta Mater. 68, 150–158 (2014).

Sun, S.-H., Hagihara, K. & Nakano, T. Effect of scanning strategy on texture formation in ni-25 at.% mo alloys fabricated by selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 140, 307–316 (2018).

Andreau, O. et al. Texture control of 316l parts by modulation of the melt pool morphology in selective laser melting. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 264, 21–31 (2019).

Chadwick, A. F. & Voorhees, P. W. The development of grain structure during additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 211, 116862 (2021).

Yang, M., Wang, L. & Yan, W. Phase-field modeling of grain evolutions in additive manufacturing from nucleation, growth, to coarsening. Npj Comput. Mater. 7, 56 (2021).

Pinomaa, T. & Provatas, N. Quantitative phase field modeling of solute trapping and continuous growth kinetics in quasi-rapid solidification. Acta Mater.168, 167–177 (2019).

Pinomaa, T. et al. Phase field modeling of rapid resolidification of al-cu thin films. J. Cryst. Growth 532, 125418 (2020).

Brener, E. & Mel’Nikov, V. Pattern selection in two-dimensional dendritic growth. Adv. Phys. 40, 53–97 (1991).

Bragard, J., Karma, A., Lee, Y. H. & Plapp, M. Linking phase-field and atomistic simulations to model dendritic solidification in highly undercooled melts. Interface Sci. 10, 121–136 (2002).

McKeown, J. T. et al. Time-resolved in situ measurements during rapid alloy solidification: Experimental insight for additive manufacturing. Jom 68, 985–999 (2016).

McKeown, J. T., Clarke, A. J. & Wiezorek, J. M. Imaging transient solidification behavior. Mrs Bull. 45, 916–926 (2020).

LaGrange, T. et al. Single-shot dynamic transmission electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 044105 (2006).

Kurz, W. & Fisher, D. Fundamentals of Solidification.(1992).

Rappaz, M. & Dantzig, J. A. Solidification (EPFL Press, 2009).

Dantzig, J., Di Napoli, P., Friedli, J. & Rappaz, M. Dendritic growth morphologies in al-zn alloys-part ii: Phase-field computations. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 44, 5532–5543 (2013).

Trivedi, R., Seetharaman, V. & Eshelman, M. The effects of interface kinetics anisotropy on the growth direction of cellular microstructures. Metall. Trans. A 22, 585–593 (1991).

Ihle, T. Competition between kinetic and surface tension anisotropy in dendritic growth. Eur. Phys. J. B Condens. Matter Complex Syst. 16, 337–344 (2000).

Saidi, P., Frolov, T., Hoyt, J. & Asta, M. An angular embedded atom method interatomic potential for the aluminum–silicon system. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 22, 055010 (2014).

Hoyt, J., Asta, M. & Karma, A. Method for computing the anisotropy of the solid-liquid interfacial free energy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5530 (2001).

Tourret, D., Song, Y., Clarke, A. J. & Karma, A. Grain growth competition during thin-sample directional solidification of dendritic microstructures: A phase-field study. Acta Mater.122, 220–235 (2017).

Roehling, J. D. et al. Rapid solidification growth mode transitions in al-si alloys by dynamic transmission electron microscopy. Acta Mater. 131, 22–30 (2017).

LaGrange, T., Reed, B. W. & Masiel, D. J. Movie-mode dynamic electron microscopy. Mrs Bull. 40, 22–28 (2015).

Zweiacker, K. et al. Determination of crystal growth rates during rapid solidification of polycrystalline aluminum by nano-scale spatio-temporal resolution in situ transmission electron microscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 055106 (2016).

Bachmann, F., Hielscher, R. & Schaeben, H. Texture analysis with mtex–free and open source software toolbox. in Solid State Phenomena, 160, 63–68 (Trans Tech Publ, 2010).

Rauch, E. F. et al. New features in crystal orientation and phase mapping for transmission electron microscopy. Symmetry 13, 1675 (2021).

Karma, A. Phase-field formulation for quantitative modeling of alloy solidification. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 115701 (2001).

Echebarria, B., Folch, R., Karma, A. & Plapp, M. Quantitative phase-field model of alloy solidification. Phys. Rev. E 70, 061604 (2004).

Bachmann, F., Hielscher, R. & Schaeben, H. Grain detection from 2d and 3d ebsd data-specification of the mtex algorithm. Ultramicroscopy 111, 1720–1733 (2011).

McMahon, C. et al. Boundary identification in ebsd data with a generalization of fast multiscale clustering. Ultramicroscopy 133, 16–25 (2013).