Abstract

Electrolysis of low-grade impure water offers a sustainable approach to hydrogen production. However, unstable interfacial pH caused by electrochemical reactions accelerates ion-induced electrode degradation. Here, we show an ion-selective gate strategy, in which ion-conducting polymer coatings are applied onto commercial platinum carbon and iridium oxide catalysts to enable selective ion transport and to stabilize the interfacial pH. Compared with conventional aqueous electrolytes, this solid-state configuration effectively suppresses local pH fluctuations and blocks the migration of detrimental impurity ions. The ion-selective gate achieves nearly complete rejection of common ions found in seawater, river and lake water, and industrial wastewater, demonstrating broad adaptability to impurity-rich environments. In untreated seawater, the ion-selective gate engineered electrode operates stably for 1500 h at 200 mA cm−2, with a degradation rate of 5.2 mV kh−1, approaching the durability of pure water electrolysis. This design is compatible with both proton exchange membrane and anion exchange membrane electrolyzers, providing a scalable route for sustainable hydrogen generation from natural water sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introdution

Freshwater is becoming increasingly scarce, with over 80% of the global population facing high water security risks1,2,3,4. Traditional water electrolysis systems that rely on ultrapure water not only worsen these challenges but also raise operational costs and limit large-scale deployment5,6,7,8,9,10. In contrast, using impurity-rich water sources, such as natural or low-grade water, offers a sustainable alternative that reduces dependence on freshwater and improves the economic feasibility of hydrogen production5,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. However, electrolysis in these non-pure water environments introduces additional challenges, particularly in maintaining long-term operational stability13,24,25. The highly dynamic interfacial microenvironment during electrolysis, under applied electric fields, drives specific ion migration within the electrolyte, while simultaneous hydrogen evolution (HER) and oxygen evolution (OER) reactions at the electrodes induce severe local pH fluctuations5,26,27,28. These pH changes, which can vary by 5 to 9 units from the bulk solution, not only accelerate catalyst degradation but also significantly reduce efficiency29,30,31. The presence of diverse ionic contaminants in impurity-rich water sources, such as calcium, magnesium, and chloride ions, exacerbates the challenges at the electrode interface32. These ions cause fouling, precipitation, and competitive adsorption, leading to rapid performance deterioration33,34,35,36,37. The existing catalyst modifications partially block ions but have limited ability to regulate interfacial ions and pH12,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. As a result, stability is restricted to 100 h in impure water, far below 1000 h observed for pure water electrolysis45,46,47,48,49,50. This limitation stems from slow ion transport in aqueous environments, which restricts the rapid transfer of H+ and OH− needed to stabilize interfacial pH. As a result, long-term performance in impure water remains a challenge.

Compared to aqueous electrolytes, solid-state ion conductors offer a promising solution to overcome the inherent limitations of ion transport rates in liquid-phase systems. Among these, ion-conducting polymers (ionomers) have attracted attention because of their ability to facilitate ion transport in electrochemical systems. The charged functional groups in ionomers, such as sulfonic acid or quaternary ammonium, enable selective ion transport by repelling cations or anions. The hydrophobic backbone (e.g., -CH2-, -CF2-) provides mechanical integrity and drives microphase separation, confining water to ion-rich domains and limiting excessive swelling. The ionic side chains (e.g., -SO3H in Nafion; quaternary ammonium in AEMs) form hydrated nanochannels where H+ or OH− are conducted via a combination of structural (Grotthuss-like) and vehicular diffusion, with their relative contributions governed by hydration and temperature51,52. While ionomers have been used in fuel cells53 and pure water electrolyzers54,55 for proton conduction or as structural binders, their role as dynamic interfacial regulators in impurity-rich environments enables precise ion transport control and pH stabilization, offering a transformative strategy for long-term stable water electrolysis. Their robust design also makes ionomers highly adaptable, ensuring compatibility with various catalysts and electrolysis configurations, enabling stable performance across a wide range of operational conditions.

In this work, we develop an ion-selective gate (ISG) strategy that involves ionomer coatings directly onto commercial Pt/C and IrOx catalysts to address the persistent challenges of impurity ion deposition, pH instability, and electrode degradation in electrolysis of impure saline water. By facilitating selective ion transport and enhancing H+ and OH− mobility at the electrode interface, the ISG suppresses the chlorine evolution reaction (ClER) at the anode, mitigates precipitation at the cathode, and prevents catalyst deactivation. This approach enables over 1500 h of stable operation in untreated natural seawater, approaching the durability achieved in pure water electrolysis. Unlike the existing strategies that are designed to tackle single-electrode challenges in isolation, our ISG design provides comprehensive interfacial stability across both electrodes, ensuring broad applicability to proton exchange membrane (PEM) and anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzers. This work offers a scalable and universal solution to extend electrolyzer lifespan in ion-rich environments, addressing a critical barrier for large-scale hydrogen production from low-grade water sources.

Results

Ion transport control via ISG

We introduce ISG engineering—a universal strategy that employs ion-selective ionomers to precisely manage ion transport and pH, enabling stable operation at the electrode-water interface across diverse electrolyzer configurations. In impurity-rich natural water, the most problematic impurities are calcium and magnesium cations and chloride anions. Our ISG strategy uses ionomers to enhance electrolysis in impurity-rich water. At the cathode, anion-selective ionomers enhance OH− transport and block calcium and magnesium ions to prevent precipitation and active site blockage. At the anode, cation-selective ionomers facilitate H+ transport and block chloride ions, effectively suppressing ClER. This dual ion management redefines the role of ionomers by achieving optimal ion selectivity and greatly improving electrode stability, representing a transformative advancement in impurity-rich water electrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The ISG used in this study, constructed from commercially available ionomers PiperIon A-5 (anion-selective) and Nafion (cation-selective), offers a readily accessible and cost-effective solution for large-scale seawater electrolysis.

The biggest challenge in impurity-rich water electrolysis comes from the high levels of harmful ions. In this study, we take seawater electrolysis as the most complex example of impurity-rich systems. Under the influence of electric field, these ions accumulate significantly at the electrode interfaces. For instance, near the cathode, the concentration of calcium and magnesium ions rises from approximately 2000 mg L−1 to 7000 mg L−1, while concentration of chloride ions near the anode increases from around 20,000 mg L−1 to 90,000 mg L−1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Through ISG engineering, ion-selective ionomers are applied at the electrode interfaces to block the transport of these undesirable ions. Anion-selective ISG prevents calcium and magnesium ions from reaching the cathode, while cation-selective ISG restricts chloride ions from approaching the anode (Fig. 1a, b). Further analysis shows that increasing the ionomer layer thickness significantly reduces ion concentrations at both electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 3) and further enhances abilities of preventing side reactions.

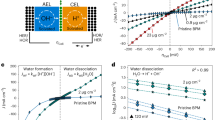

a Simulation of the anion-selective ISG effectively blocking harmful cations like Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions near the cathode during impurity-rich water electrolysis. b Simulation of the cation-selective ISG effectively blocking harmful anions like Cl− ions near the anode during impurity-rich water electrolysis. c OH− conductivity of the cathode catalyst layer with and without ISG coating, measured by EIS in a sandwich-cell configuration (schematic inset). d H+ conductivity of the anode catalyst layer with and without ISG coating, measured by EIS in a sandwich-cell configuration (schematic inset). e Schematic illustration of selective ion transport and impurity rejection by the ISG layer at electrode interfaces.

Beyond impurity rejection, another critical function of the ISG is to stabilize the local pH environment. To directly validate the OH− and H+ conduction function of ISG coatings, we measured the effective ionic conductivity of the catalyst layers using a sandwich-cell electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) configuration (Supplementary Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 1c, d, the OH− conductivity of the cathode catalyst layer increased from 4.12 ± 0.96 mS cm−1 without ISG (prepared with neutral PTFE binders) to 12.31 ± 1.95 mS cm−1 with ISG, while the H⁺ conductivity of the anode catalyst layer increased from 9.40 ± 1.08 mS cm−1 to 18.43 ± 2.66 mS cm−1. These results confirm that the ISG significantly improves ionic transport within the catalyst layers, thereby facilitating rapid removal of locally generated H+/OH− and helping to stabilize the interfacial pH during electrolysis in impurity-rich water. By combining selective impurity rejection with fast ion conduction, the ISG simultaneously stabilizes interfacial pH and prevents harmful ion accumulation at the electrode surface, effectively mitigating local fluctuations and side reactions during impurity-rich water electrolysis (Fig. 1e).

To demonstrate the ability of our ISG strategy to enable commercial catalysts for seawater electrolysis, we selected Pt/C and IrOx as cathode and anode catalysts, respectively. These catalysts, commonly employed in pure water electrolysis, have significant limitations in direct seawater applications due to the challenging ionic environment (Supplementary Fig. 5). By coating these catalysts with anion-selective and cation-selective ionomers, it is observed that the ISG uniformly encapsulates the Pt/C and IrOx catalysts respectively (Supplementary Figs. 6–14). Electrolyte analysis by ICP-OES and ion chromatography further confirms that ISG-coated electrodes suppress the accumulation of Mg2+, Ca2+, and Cl− at the interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 15). This uniform encapsulation ensures that ISG can be applied seamlessly to various catalyst surfaces without compromising their structural integrity. Additionally, the ISG-coated catalysts exhibit dispersibility, allowing them to be readily integrated into standard manufacturing processes, such as membrane electrode assembly (MEA) production, without affecting the compression or distribution of the catalyst layers.

Seawater electrolysis performance and long-term stability

We applied ISG to commercial Pt/C and IrOx and integrated them into a seawater electrolyzer with titanium (Ti) flow fields. A diaphragm membrane separated the gases to prevent H2 and O2 mixing (Fig. 2a). The catalyst loadings were 0.5 mgPt cm−2 for the cathode and 0.6 mgIr cm−2 for the anode. Analysis of the produced gases showed a stable H2 to O2 ratio of approximately 2:1 (Fig. 2b), indicating that chlorine gas generation was effectively suppressed. Additionally, our system maintained stable hydrogen production from untreated natural seawater (collected from Henley Beach, Adelaide; Supplementary Table 1) for over 1500 h without alkaline additives (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Figs. 16, 17). In contrast, conventional seawater electrolysis systems often rely on added alkaline electrolytes to improve conductivity and prevent cation precipitation. Despite these challenges, our ISG strategy enables direct seawater electrolysis with competitive stability. The system operated at an average voltage of 2.82 V under 200 mA cm−2, achieving long-term seawater electrolysis durability without the need for chemical modifications. Furthermore, no precipitates were formed to block the flow channels within the electrolyzer. In stark contrast, during unprotected conventional direct seawater electrolysis, the cell voltage rapidly increased to 4.5 V within 20 h at the same current density of 200 mA cm−2. This high voltage led to inevitable ClER, where the generated Cl2 severely corroded both the catalyst and the electrolyzer. Even the highly corrosion-resistant Ti flow field experienced significant damage (Supplementary Fig. 18). With ISG protection, the active chlorine concentration remained significantly lower, reaching just 40.7 ± 3.98 ppm after 10 h at a current density of 200 mA cm−2, while the system without ISG showed a rapid increase in active chlorine to 587.2 ± 35.43 ppm (Fig. 2d). This sharp contrast demonstrates the effectiveness of ISG in suppressing ClER, contributing to the competitive long-term stability of the system.

a Schematic of the electrolyzer using natural seawater for electrolysis with ISG at both electrodes to regulate ion transport and pH. b The volume ratio of hydrogen to oxygen during long-term seawater electrolysis. c Electrolysis durability test at a constant current density of 200 mA cm−2 in Henley Beach seawater, showing stable voltage operation over 1500 h with ISG, compared to rapid voltage increases without ISG. Inset table summarizes the operating parameters used in this work. d Active chlorine concentration and relative Faradaic efficiency for hydrogen production in seawater electrolysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The comparison of degradation rates and operating times between seawater and pure water electrolysis systems highlights the significant advancements achieved with our ISG strategy. While existing seawater electrolysis systems typically exhibit degradation rates between 100 and 10,000 mV kh−1 and fail after fewer than 100 h26,39,41,42, our ISG-protected system demonstrated a low degradation rate of 5.2 mV kh−1 and maintained stable operation for 1500 h. This performance not only far exceeds current seawater electrolysis technologies but also approaches many pure water electrolysis systems, such as PEM electrolyzers with Ir-based catalysts, which typically degrade at rates of 10–100 mV kh−1 (Supplementary Fig. 19). These results demonstrate the potential of ISG to bridge the gap between pure water electrolysis and low-grade water resources, providing a scalable and adaptable solution for hydrogen production from complex, impurity-rich sources.

Ion transport performance

As previously discussed, in seawater electrolysis, one of the critical factors influencing efficiency and long-term stability is the ability to manage the local pH at the catalyst interface. While seawater typically has a neutral or slightly alkaline pH (around 8.2), the local pH at the electrode surfaces can fluctuate significantly during electrochemical reactions, creating highly alkaline or acidic conditions. The most unique property of our ISG technology is efficient regulation of H+ and OH− transport to maintain a more stable interfacial environment. At the cathode, the ISG facilitates OH− transport away from the surface, preventing excessive alkalinity and the subsequent formation of detrimental precipitates. Operando Raman spectroscopy analysis was carried out in a custom-designed electrochemical cell (Fig. 3a). The O-H stretching region revealed that, without ISG, the fraction of weakly hydrogen-bonded water decreased sharply with current density increasing, indicating severe alkalization at the cathode. In contrast, ISG-coated electrodes maintained nearly constant hydrogen-bonding features, confirming their ability to stabilize the interfacial environment (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 20). We then conducted Raman during electrolysis at −10 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3c, d). The results show that without ISG, the cathode surface exhibits strong peaks of Mg(OH)2 and Ca(OH)2, indicating significant precipitation. In contrast, the ISG coating greatly reduced these peaks, suggesting effective prevention of such deposits by facilitating OH− transport while blocking Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions.

a Schematic illustration of the operando Raman setup in MEA mode. b Ratio of weakly/strongly H-bonded water at the cathode with and without ISG under different current densities. c Time-resolved Raman spectra at the cathode without ISG, showing the growth of Mg(OH)2 deposits. d Time-resolved Raman spectra at the cathode with ISG, showing suppressed Mg(OH)2 formation. e Ratio of weakly/strongly H-bonded water at the anode with and without ISG under different current densities. f Cl element XPS spectra of the anode surface with and without ISG after the OER reaction. g Faradaic efficiency for hydrogen evolution in the presence of various cationic impurities. h Faradaic efficiency for oxygen evolution in the presence of various anionic impurities. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis further confirmed this observation, with XRD patterns showing that the ionomer coating significantly suppressed the formation of Mg(OH)2 and Ca(OH)2 on the cathode surface during electrolysis (Supplementary Figs. 21–24). The measured pH values at the catalyst surface under various potentials reveal that the ISG significantly stabilized the local pH (Supplementary Figs. 25–28). Chronopotentiometry tests revealed that the ISG-coated cathode maintained stable voltage during HER in natural seawater, while the uncoated cathode experienced rapid voltage increases due to active site blockage (Supplementary Fig. 29). This trend highlights the enhanced capacity of ISG to efficiently transport OH− ions, thereby mitigating local pH fluctuations and effectively regulating the interfacial environment.

At the anode, we explored the effect of cation ISG coating on the OER performance and optimized their loading to effectively suppress ClER. Our results demonstrate that ionomer-coated anodes significantly reduce the overpotential by 260 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 in natural seawater, compared to uncoated anodes (Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31). This adjustment also improved the Faradaic efficiency (FE) for OER from 38.2% to 95.1%, with ClER effectively suppressed for at least 4 h (Supplementary Figs. 32–35). Operando Raman spectroscopy further confirmed this effect: without ISG, the fraction of weakly hydrogen-bonded water increased markedly with current density increasing, indicating severe acidification, while ISG-coated anodes maintained nearly constant hydrogen-bonding features, evidencing a stabilized interfacial environment (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 36). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and chronopotentiometry tests (10–100 mA cm−2) revealed that ionomer-coated anodes significantly reduced chlorine adsorption and corrosion, leading to slower voltage degradation and improved long-term stability (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 37).

In addition to these pH-dependent results, we also investigated the impurity tolerance of ISG in the presence of common ionic contaminants. we selected five representative cations (Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, Na+, Cu2+) and five anions (Cl−, Br−, SO42−, NO3−, CO32−) commonly found in seawater, river or lake water, and industrial wastewater. The data shows that ISG achieves near 100% tolerance efficiency for these impurity ions, effectively blocking these harmful cations and anions (Fig. 3g, h; Supplementary Fig. 38). This high rejection rate for both cations and anions demonstrates the ability of ISG to selectively prevent undesirable ions from reaching the electrodes while facilitating the transport of essential species like OH− and H+, ultimately improving overall electrolysis performance in impurity-rich environments. These findings highlight the versatility and efficiency of ISG, making it a promising solution for enhancing the performance and stability of electrolysis systems across a wide range of operational conditions, including in environments with varying pH levels and impurity-rich water sources.

Figure 4a illustrates the critical role of ISG in enhancing ion transport during seawater electrolysis. At the cathode, the anion-selective ISG blocks calcium and magnesium ions while accelerating OH− transport. At the anode, the cation-selective ISG inhibits chloride ions and promotes rapid H+ transport. The ISG constructed from ion-selective ionomers exhibits significantly higher ionic mobilities. The comparison of ion production-to-accumulation ratios at the electrode interfaces highlights the superior interfacial ion management enabled by the ISG layer (Fig. 4b, c). At the cathode, the OH⁻ production-to-accumulation ratio in the ISG system steadily increases to nearly 104, demonstrating efficient OH− removal and preventing disruptive accumulation. In contrast, the OH⁻ production-to-accumulation ratio in conventional aqueous systems progressively declines to approximately 10, indicating poor ion transport and severe local alkalinity. Similarly, at the anode, the H+ production-to-accumulation ratio in the ISG system reaches nearly 105. In liquid-phase systems, this ratio drops below 10, showing poor proton transport and severe local acidification.

a Schematic of ISG-mediated ion transport at the cathode and anode, illustrating selective ion blocking and ion transport pathways. b OH− production-to-accumulation ratios at the cathode in ISG and aqueous systems. c H+ production-to-accumulation ratios at the anode in ISG and aqueous systems. d Ion mobility ratios (OH− in ISG vs. solution) and surface H+ concentration at the anode as functions of ISG content. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The boundary-layer diffusion model (equations in Fig. 4b, c) explains these trends. The ISG has much higher ionic diffusion coefficients for H+ and OH− than liquid-phase electrolytes. This allows faster ion removal, stabilizes interfacial pH, and improves electrochemical performance. Using the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation (equation in Fig. 4d), we calculated the ionic mobilities at different ISG contents to analyze their effect on transport dynamics. The OH− mobility ratio in ISG compared to liquid-phase electrolytes exhibits an increasing trend, peaking at approximately 25 with 40% of ISG content. As ISG content increases, the surface H+ accumulation ratio declines and eventually stabilizes, demonstrating the ISG’s ability to suppress H+ accumulation and maintain a balanced interfacial environment. Compared to conventional material-based strategies (i.e., self-cleaning surfaces29 or in-situ growth of pH-regulating materials26), our ISG method is simpler and more versatile. It allows precise ion transport control and makes the system design more efficient.

Versatility across electrolysis systems

To evaluate the pH adaptability of the ISG strategy, we investigated its performance across a wide pH range to simulate operating conditions of commercial PEM and AEM electrolyzers. At the cathode, the ISG maintained high OH− transport rates across varying pH levels (6.3 to 10), while effectively suppressing surface-bulk ΔpH, indicating strong capability to mitigate local alkalinity accumulation (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 39). Under three representative pH conditions (1, 8.2, and 14), the ISG-protected cathode exhibited stable operation over 200 h with negligible voltage fluctuations and sustained HER Faradaic efficiency above 90% (Fig. 5b, c). Similarly, at the anode, the ISG facilitated consistent H+ transport across the same pH range and effectively suppressed interfacial acidification, as evidenced by minimized ΔpH values (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 40). Long-term OER tests under identical pH conditions confirmed stability and FE exceeding 90% (Fig. 5e, f). Together, these results highlight the robustness and broad applicability of the ISG across diverse electrochemical environments, underscoring its potential as a universal interfacial design for practical water electrolysis systems.

a OH− transport rate and surface-bulk ΔpH at the cathode across a pH range from 6.3 to 10. b Voltage profiles of the ISG-protected cathode during 200 h HER under different pH conditions: pH = 1 (tested at 10 mA cm−2), pH = 8.2 and 14 (tested at 100 mA cm−2). c Faradaic efficiency and voltage change after 200 h HER under different pH conditions. d H+ transport rate and ΔpH at the anode from pH 6.3 to 10. e Voltage profiles of the ISG-protected anode during 200 h OER under pH = 1, 8.2, and 14, all tested at 100 mA cm−2. f Faradaic efficiency and voltage change after 200 h OER under different pH conditions. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

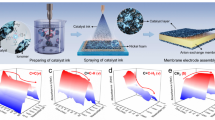

To explore the broad applicability of the ISG strategy, we applied ISG across two pure water electrolysis: PEM and AEM (Fig. 6a). These systems often encounter challenges like ion accumulation and performance degradation in ion-rich environments such as seawater. We integrated the ISG with commercial Pt/C and IrOx catalysts to address key challenges in seawater electrolysis, including ion accumulation and electrochemical instability (Fig. 6b, c). While PEM electrolyzers have made significant progress with advanced catalysts, bipolar plates, and ion-exchange membranes, adapting this technology to seawater electrolysis remains difficult. The acidic environment at the catalyst interface in PEM systems makes them particularly prone to ClER. To evaluate the effectiveness of the ISG in mitigating these issues, we tested it using RO-grade diluted seawater at 60 °C. With ISG protection, the PEM seawater electrolyzer achieved an industrially relevant hydrogen production current density of 1.0 A cm−2 at a cell voltage of 1.81 V, matching the performance typically seen in PEM systems operating with pure water (Fig. 6d). In contrast, the unprotected system required a significantly higher voltage of 1.88 V to reach the same current density of 1.0 A cm−2, further demonstrating the superior efficiency by the ISG strategy. Long-term chronopotentiometry tests at 1.0 A cm−2 further confirmed the stability of the ISG-protected PEM system, which maintained a nearly constant voltage over 100 h, while the unprotected system failed within 10 h due to a sharp voltage spike (Fig. 6e).

a Schematic of the PEM/AEM mode seawater electrolysis. b Chemical structure of the anion-selective ISG used in the cathode coating. Optical and microscopic images of the Pt/C catalyst coated with anion-selective ISG at the cathode. Microscopic features of the ISG-coating are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 50 μm. The inset shows the membrane electrode assembly (scale bar: 1 cm). c Chemical structure of the cation-selective ISG used in the anode coating. Optical and microscopic images of the IrOx catalyst coated with cation-selective ISG at the anode. Microscopic details of the ISG layer are highlighted by arrows, with a scale bar of 50 μm. The inset displays the membrane electrode assembly (scale bar: 1 cm). d Polarization curves of the PEM electrolyzer in RO-grade diluted seawater at 60 °C. e Voltage stability of the PEM system at 1.0 A cm−2 over 100 h. Inset table summarizes the operating parameters used in this work. f Polarization curves of the AEM electrolyzer in natural seawater at 80 °C with and without ISG. g Voltage stability of the AEM system at 200 mA cm−2 over 100 h. Inset table summarizes the operating parameters used in this work. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

AEM technology has advanced in pure and alkaline water electrolysis. However, its use in seawater is limited by calcium and magnesium precipitation, which worsens in the alkaline environment of AEM systems. In AEM mode, with natural seawater as the electrolyte at both electrodes, the ISG-coated system achieved a cell voltage of 2.87 V at 1.0 A cm−2—significantly lower than the 4.71 V required by the unprotected system (Fig. 6f). This reduction in voltage underscores the ability of ISG to mitigate ion-induced degradation and precipitation, even in more challenging conditions like natural seawater. At a current density of 200 mA cm−2, the ISG-coated AEM system remained stable for over 100 h, whereas the unprotected system showed rapid voltage rise and failed within 10 h (Fig. 6g). These results confirm that the ISG strategy can be seamlessly integrated into both acidic and alkaline electrolysis platforms, offering strong compatibility, efficiency, and long-term stability in practical seawater electrolysis systems.

Discussion

This study addresses the challenges of impure water electrolysis by demonstrating that the ISG engineering effectively suppresses ion-induced degradation of electrodes and stabilizes interfacial pH. By integrating ion-selective ionomers at both electrodes, the ISG strategy mitigates catalyst deactivation and significantly extends system durability, achieving over 1500 h of stable operation in natural seawater. The demonstration of 100 h stability in both PEM and AEM electrolyzers highlights the versatility of the ISG strategy and reinforces its potential for scalable integration into diverse water electrolysis systems. Moving forward, further optimization of ionomer composition, layer thickness, and interfacial architecture could enhance ion selectivity and transport efficiency, enabling longer operational lifetimes under more demanding electrolysis conditions. This work lays the foundation for scalable hydrogen production from abundant, low-grade water resources, advancing sustainable energy solutions beyond reliance on ultrapure water.

Methods

Chemicals

The cation-selective ionomer used was Nafion perfluorinated resin solution (product #527084-25 ml) purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The anion-selective ionomer was PiperIon A-5 from Versogen. The Pt/C catalyst containing 20% Pt and the IrOx catalyst were both obtained from Premetek. Deionized (DI) water was supplied by the Milli-Q Benchtop laboratory water purification system (Sigma-Aldrich).

Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted using a Rigaku MiniFlex 600 X-ray diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.54 Å, operating at 40 kV and 15 mA). High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were obtained using an FEI Titan Themis microscope with aberration correction, operating at 200 kV. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were captured using a FEI QUANTA 450 FEG Environmental SEM, operating at 10 kV. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired with a Philips CM200 microscope, operating at 200 kV. XPS analyses were performed under ultra-high vacuum conditions using a Kratos Axis Ultra DLD photoelectron spectrometer with an aluminum monochromatic X-ray source.

Finite-element method simulations

Finite element simulations were performed using COMSOL Multiphysics with the Transport of Diluted Species (TDS) module coupled with Nernst–Planck migration and chemical species definitions. A rectangular domain (1 μm width, 150 μm length) was used to represent the electrode-electrode distance. The electrode boundaries were fixed at –0.5 V for the cathode and 2.0 V for the anode. Bulk concentrations of Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl−, and SO42− were set according to seawater composition, and transport was governed solely by diffusion and migration with convection neglected. The system was solved under steady-state conditions with activity coefficients set to unity. The electrical double layer was treated using the Gouy–Chapman–Stern model, which includes a compact Helmholtz layer (specifically adsorbed ions) and a diffuse layer (counter-ions and co-ions). Diffusion coefficients and bulk concentrations used in the simulations are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Ionic conductivity measurements

The ionic conductivity of the catalyst layers was evaluated using a symmetric sandwich cell configuration (membrane | CL | membrane), which suppresses electronic conduction and avoids electrode reaction interference. Pt-coated stainless-steel plates were used as blocking electrodes. Prior to assembly, the membranes were pretreated following standard procedures. PiperIon A20 membranes were soaked in CO2-free 1 M KOH at 60 °C for 4 h, while Nafion 115 membranes were cleaned in H2O2 solution, protonated in H2SO4, and rinsed thoroughly in deionized water. Catalyst inks were sprayed onto one side of the membranes. Two types of electrodes were prepared: “with ISG,” in which the ion-selective ionomer was used, and “without ISG,” in which only PTFE binder was used. The thickness of the catalyst layers was measured with a digital micrometer. A second membrane of the same type was then placed on top to complete the sandwich structure, which was clamped between the Pt-coated stainless-steel electrodes. EIS measurements were performed at open-circuit potential using a frequency range of 105-1 Hz, with the cell being maintained at 60 °C. The high-frequency intercept was taken as the total resistance of the sandwich cell. The resistance of the membrane alone (two-membrane control without CL) was subtracted to obtain the resistance of the catalyst layer.

Then, the ionic conductivity of catalyst layers was then calculated according to the relation:

where L is the thickness of the catalyst layer, RCL is the resistance of catalyst layer, and A is the electrode area (0.785 cm2 for a circular electrode with a diameter of 1 cm).

Electrochemical measurements

Natural seawater was collected from the surface of Henley Beach, Adelaide, Australia, and filtered to remove solids and microorganisms before testing (pH = 8.20 ± 0.02). Electrochemical measurements were conducted in a three-electrode setup using a CHI-760E electrochemical workstation at room temperature (25 °C). The electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) was estimated based on the electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl). Cdl values were determined by cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans in a non-Faradaic potential range from 1.03 to 1.13 V versus RHE, with scan rates of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mV s−1. For long-term durability tests in natural seawater, a carbon fiber substrate was used for the cathode, while a platinum-coated titanium fiber substrate was used for the anode. For the control electrodes denoted as “without ISG,” polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) was used as a neutral binder in place of ionomer. Potentials for all three-electrode measurements were referenced to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), calculated by adding 0.196 + 0.059 × pH V to the potential vs. Ag/AgCl electrode.

In-situ Raman measurements

In-situ Raman spectroscopy measurements were performed using a Renishaw Raman spectrometer (Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution) equipped with a 60× (1.0 N.A) water-immersion objective (Olympus), utilizing a 532 nm laser wavelength. Data collection involved 10-s exposures, repeated 10 times. A screen-printed chip electrode from Pine Research Instrumentation was employed for potentiostatic tests on a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation. Prepared ink was applied to the chip and allowed to dry at room temperature (25 °C), with natural seawater serving as the electrolyte. An Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference electrode, and a platinum electrode was used as the counter electrode.

Seawater electrolysers

For the diaphragm mode seawater electrolysis, natural seawater was used as the electrolyte, and the gases at the cathode and anode were separated by a ZIRFON UTP 220 Membrane. The ionomer-coated catalysts layer was sprayed onto titanium fibre felts, followed by a protective layer of activated carbon. The catalyst loadings were 0.5 mgPt cm−2 for the cathode and 0.6 mgIr cm−2 for the anode, with activated carbon loadings of ~0.08 mg cm−2, respectively. For electrode with ionomer-coated catalyst, the ionomer loading was fixed at 40 wt%, defined as the mass of ionomer divided by the total mass of ionomer plus catalyst. This value was selected based on systematic optimization experiments. A thin carbon black interlayer was also added to improve electronic conductivity. Natural seawater flowed through the cell at a rate of 60 ml min−1. The steady-state polarization curve was tested at 80 °C, and the stability test was conducted at 40 °C. For the PEM mode seawater electrolysis, seawater used as the electrolyte was diluted 300 times. A Ti-fiber felt (0.25 mm thickness, 78% porosity) served as the anodic gas diffusion layer (GDL), while carbon paper (TGP-H-060, Toray Industries, Inc) was used as the cathodic GDL. The PEM mode test was conducted at 60 °C, with diluted seawater flowing through the cell at 50 ml min−1. For the AEM mode seawater electrolysis, natural seawater was used as the electrolyte, with gases at the cathode and anode separated by a PiperIon A20 anion exchange membrane. The ionomer-coated catalysts were sprayed on both sides of the PiperIon A20 membrane, followed by a protective layer of activated carbon. The prepared membrane electrode was soaked in 1 M KOH for 10 h, with the KOH solution replaced every two hours. Natural seawater flowed through the cell at a rate of 50 ml min−1. The steady-state polarization curve was tested at 80 °C, and the stability test was conducted at 25 °C.

Gas analysis and FE calculation

H2 and O2 were quantified directly using online gas chromatography (GC, Agilent 8890) equipped with thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a flame ionization detector (FID). External calibration was used to convert peak areas into molar amounts. For MEA tests, the catalyst layers were spray-coated directly onto membranes using the same ink formulation and catalyst/ionomer loadings as in the electrolyzer tests. For H-cell tests, electrodes were prepared with the identical spray-coating procedure and ink composition, but deposited onto a titanium fiber felt substrate. The Faradaic efficiency (FE) was calculated from the detected product amount and the total charge passed according to:

where n is the number of charges involved in the reaction (2 for H2, 4 for O2); F is the Faraday constant (96485 C mol−1); v is the flow rate of gas products; c is the measured concentration of H2 and O2 by GC; A is the area of working electrode; Vm is the gas molar volume (Vm = 24.5 L mol−1, 1.01 × 105 Pa, 25 °C); Jtot is the total current density.

Data availability

The source data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Vorosmarty, C. J. et al. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 467, 555–561 (2010).

Garrido-Baserba, M. et al. Using water and wastewater decentralization to enhance the resilience and sustainability of cities. Nat. Water 2, 953–974 (2024).

Cassol, G. S. et al. Ultra-fast green hydrogen production from municipal wastewater by an integrated forward osmosis-alkaline water electrolysis system. Nat. Commun. 15, 2617 (2024).

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4667 (2021).

Tong, W. et al. Electrolysis of low-grade and saline surface water. Nat. Energy 5, 367–377 (2020).

Franco, B. A., Baptista, P., Neto, R. C. & Ganilha, S. Assessment of offloading pathways for wind-powered offshore hydrogen production: Energy and economic analysis. Appl. Energy 286, 116553 (2021).

Moliner, R., Lázaro, M. J. & Suelves, I. Analysis of the strategies for bridging the gap towards the Hydrogen Economy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 41, 19500–19508 (2016).

Liu, W. et al. Ferricyanide Armed Anodes Enable Stable Water Oxidation in Saturated Saline Water at 2 A/cm2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309882 (2023).

Duan, X. et al. Dynamic chloride ion adsorption on single iridium atom boosts seawater oxidation catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 1973 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. High-Performance Alkaline Seawater Electrolysis with Anomalous Chloride Promoted Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311674 (2023).

Dresp, S., Dionigi, F., Klingenhof, M. & Strasser, P. Direct Electrolytic Splitting of Seawater: Opportunities and Challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 933–942 (2019).

Deng, P. J. et al. Layered Double Hydroxides with Carbonate Intercalation as Ultra-Stable Anodes for Seawater Splitting at Ampere-Level Current Density. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400053 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Progress in Anode Stability Improvement for Seawater Electrolysis to Produce Hydrogen. Adv. Mater. 36, e2311322 (2024).

Xie, H. et al. A membrane-based seawater electrolyser for hydrogen generation. Nature 612, 673–678 (2022).

Veroneau, S. S. & Nocera, D. G. Continuous electrochemical water splitting from natural water sources via forward osmosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e202455118 (2021).

Veroneau, S. S., Hartnett, A. C., Thorarinsdottir, A. E. & Nocera, D. G. Direct Seawater Splitting by Forward Osmosis Coupled to Water Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 1403–1408 (2022).

Marin, D. H. et al. Hydrogen production with seawater-resilient bipolar membrane electrolyzers. Joule 7, 765–781 (2023).

Caldera, U. & Breyer, C. Learning Curve for Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination Plants: Capital Cost Trend of the Past, Present, and Future. Water Resour. Res. 53, 10523–10538 (2017).

Generous, M. M., Qasem, N. A. A., Akbar, U. A. & Zubair, S. M. Techno-economic assessment of electrodialysis and reverse osmosis desalination plants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 272, 118875 (2021).

Kuang, Y. et al. Solar-driven, highly sustained splitting of seawater into hydrogen and oxygen fuels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 116, 6624–6629 (2019).

Liu, T. et al. In-situ direct seawater electrolysis using floating platform in ocean with uncontrollable wave motion. Nat. Commun. 15, 5305 (2024).

Liang, J. et al. Efficient bubble/precipitate traffic enables stable seawater reduction electrocatalysis at industrial-level current densities. Nat. Commun. 15, 2950 (2024).

Liang, J. et al. Electroreduction of alkaline/natural seawater: Self-cleaning Pt/carbon cathode and on-site co-synthesis of H2 and Mg hydroxide nanoflakes. Chem 10, 3067–3087 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Seawater electrolysis for fuels and chemicals production: fundamentals, achievements, and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 7455–7488 (2024).

Gao, F.-Y., Yu, P.-C. & Gao, M.-R. Seawater electrolysis technologies for green hydrogen production: challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 36, 100827 (2022).

Huang, C. et al. Functional Bimetal Co-Modification for Boosting Large-Current-Density Seawater Electrolysis by Inhibiting Adsorption of Chloride Ions. Adv. Energ. Mater. 13, 2301475 (2023).

He, X. et al. Engineered PW12-polyoxometalate docked Fe sites on CoFe hydroxide anode for durable seawater electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 16, 5541 (2025).

Liang, J. et al. Expanded Negative Electrostatic Network-Assisted Seawater Oxidation and High-Salinity Seawater Reutilization. ACS Nano 19, 1530–1546 (2025).

Yi, L. et al. Solidophobic Surface for Electrochemical Extraction of High-Valued Mg(OH)2 Coupled with H2 Production from Seawater. Nano Lett. 24, 5920–5928 (2024).

Bao, D. et al. Dynamic Creation of a Local Acid-like Environment for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Natural Seawater. J. Am. Chem. Soc. (2024).

He, X. et al. Hexafluorophosphate additive enables durable seawater oxidation at ampere-level current density. Nat. Commun. 16, 4998 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. Concerning the stability of seawater electrolysis: a corrosion mechanism study of halide on Ni-based anode. Nat. Commun. 14, 4822 (2023).

Lyu, X. & Serov, A. Cutting-edge methods for amplifying the oxygen evolution reaction during seawater electrolysis: a brief synopsis. Ind. Chem. Mater. 1, 475–485 (2023).

Dionigi, F., Reier, T., Pawolek, Z., Gliech, M. & Strasser, P. Design Criteria, Operating Conditions, and Nickel-Iron Hydroxide Catalyst Materials for Selective Seawater Electrolysis. ChemSusChem 9, 962–972 (2016).

Fei, H. et al. Direct Seawater Electrolysis: From Catalyst Design to Device Applications. Adv. Mater. 36, e2309211 (2024).

Vos, J. G., Wezendonk, T. A., Jeremiasse, A. W. & Koper, M. T. M. MnOx/IrOx as Selective Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalyst in Acidic Chloride Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10270–10281 (2018).

Carmo, M., Fritz, D. L., Mergel, J. & Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 38, 4901–4934 (2013).

Obata, K. & Takanabe, K. A Permselective CeOx Coating To Improve the Stability of Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1616–1620 (2018).

Wang, N. et al. Strong-Proton-Adsorption Co-Based Electrocatalysts Achieve Active and Stable Neutral Seawater Splitting. Adv. Mater. 35, e2210057 (2023).

Praveen Kumar, S., Sharafudeen, P. C. & Elumalai, P. High entropy metal oxide@graphene oxide composite as electrocatalyst for green hydrogen generation using anion exchange membrane seawater electrolyzer. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 38156–38171 (2023).

Liu, Q. et al. Ion sieving membrane for direct seawater anti-precipitation hydrogen evolution reaction electrode. Chem. Sci. 14, 11830–11839 (2023).

Zhao, S. et al. Lewis Acid Driving Asymmetric Interfacial Electron Distribution to Stabilize Active Species for Efficient Neutral Water Oxidation. Adv. Mater. 36, e2308925 (2024).

Dresp, S. et al. Molecular Understanding of the Impact of Saline Contaminants and Alkaline pH on NiFe Layered Double Hydroxide Oxygen Evolution Catalysts. ACS Catal. 11, 6800–6809 (2021).

Jin, H. et al. Stable and Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution from Seawater Enabled by an Unsaturated Nickel Surface Nitride. Adv. Mater. 33, e2007508 (2021).

Li, A. et al. Atomically dispersed hexavalent iridium oxide from MnO2 reduction for oxygen evolution catalysis. Science 384, 666–670 (2024).

Klingenhof, M. et al. High-performance anion-exchange membrane water electrolysers using NiX (X = Fe,Co,Mn) catalyst-coated membranes with redox-active Ni–O ligands. Nat. Catal. 7, 1213–1222 (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. Anion Exchange Ionomers Enable Sustained Pure-Water Electrolysis Using Platinum-Group-Metal-Free Electrocatalysts. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 5018–5024 (2023).

Sun, Q. et al. Understanding hydrogen electrocatalysis by probing the hydrogen-bond network of water at the electrified Pt–solution interface. Nat. Energy (2023).

Shiva Kumar, S. & Himabindu, V. Hydrogen production by PEM water electrolysis – A review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2, 442–454 (2019).

Qiu, C., Xu, Z., Chen, F.-Y. & Wang, H. Anode Engineering for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers. ACS Catal. 14, 921–954 (2024).

Merle, G., Wessling, M. & Nijmeijer, K. Anion exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 377, 1–35 (2011).

Kreuer, K.-D. Ion Conducting Membranes for Fuel Cells and other Electrochemical Devices. Chem. Mater. 26, 361–380 (2013).

Jinnouchi, R. et al. The role of oxygen-permeable ionomer for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 4956 (2021).

Li, D. et al. Highly quaternized polystyrene ionomers for high performance anion exchange membrane water electrolysers. Nat. Energy 5, 378–385 (2020).

Mardle, P., Chen, B. & Holdcroft, S. Opportunities of Ionomer Development for Anion-Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 3330–3342 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding from the Australian Research Council (CE230100032, S.-Z.Q., Y.Z.; DP230102027, S.-Z.Q.; DP240102575, Y.Z.; FT200100062, Y.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and S.-Z.Q. conceived and supervised this research. F.-Y.G. designed and conducted the characterizations, and electrochemical measurements. J.X. assisted with the electrochemical measurements. H.S. performed SEM measurements. J.-W.D. assisted with the finite element simulation. M.J., Y.Z., and S.-Z.Q. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors (F.-Y.G., Y.Z., and S.-Z.Q.) declare the following competing interests: a patent (Australian Provisional Patent 64631AU-P) has been filed based on this study. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, FY., Xu, J., Shen, H. et al. Ion-selective interface engineering for durable electrolysis of impure water. Nat Commun 16, 11625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66711-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66711-x