Abstract

2,2’,7,7-tetrakis(N,N-di(4-methoxyphenylamine)−9,9′-spirobifluorene (spiro-OMeTAD) remains as the most widely used material for the hole transport layer (HTL) in efficient n-i-p perovskite photovoltaic devices. However, the conventional recipe, i.e., spiro-OMeTAD doped with bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide (LiTFSI) and 4-tert-butylpyridine (tBP) leads to poor device operational stability. Here, we introduce a strategy that employs light to generate protons in the precursor solution by ammonium TFSI dopants, which in turn increases the conductivity of HTL by the formation of oxidized spiro (referred to as light-oxidation doping treatment or LODT in short). Devices utilizing the LODT strategy results in reduced hysteresis and enhanced operational stability. The best perovskite solar module (PSM) achieves a certified power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 20.95% for a 12.83 cm² aperture area, standing out as one of the best Li-free spiro-OMeTAD HTL based PSMs. Furthermore, the unencapsulated perovskite solar cell has an extended operational stability profile exceeding 700 hours with only 7% decrease in the initial PCE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

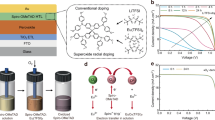

Metal halide perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have garnered significant research attention due to their remarkable upsurge in power conversion efficiency (PCE) from 3.8 to 27.3%1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In PSCs, the hole transport layer (HTL) is one of the essential components for extracting and transporting photo-generated holes, thus influencing device performance. 2,2’,7,7-tetrakis(N,N-di(4-methoxyphenylamine)−9,9′-spirobifluorene (spiro-OMeTAD, or spiro) mixed with lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide (LiTFSI) and 4-tert-butylpyridine (tBP)8,9,10,11 as hole transport layer (spiro-HTL) is commonly adopted in n-i-p structured PSCs, leading to high PCEs5,6,10,11,12,13. Such a widely employed spiro-HTL in PSCs is endowed with abilities of suitable energy level matching with respect to the underlying perovskite (PVSK) layer, relatively high conductivity with good hole extraction capability, and easy upscaling on larger area perovskite solar modules (PSMs). However, two main issues, including the post-oxidation process of spiro-HTL that requires oxygen diffusion from ambient air and tBP threatening the long-term operational stability, pose a significant obstacle to their commercialization as summarized in Fig. 1a14,15,16,17,18,19. In particular, under ambient conditions, the high-performance spiro-HTL-based PSMs remain a challenge20,21,22.

a Comparisons of disadvantages and advantages between conventional spiro-HTL and the proposed light-accelerated oxidation treatment (LODT) spiro-HTL in perovskite photovoltaics. b LODT process for HTL. This process utilizes a proton-donating salt, NH4TFSI, to facilitate the light-accelerated, proton-mediated oxidation of spiro-OMeTAD to spiroTFSI. c Application of TFSI salts in the perovskite layer and at the interface. KTFSI is incorporated as additive into the perovskite precursor solution to improve the crystalline quality of the film and to optimize the energy level alignment with HTL; OATFSI is employed as a co-dopant in HTL and surface passivation on perovskite to enhance its hydrophobicity and form stable 2D PVSK.

For a considerable time, numerous studies have focused on the doping methods and additives for the spiro-HTL. These include using protons such as HTFSI to directly oxidize spiro and enhance the conductivity of spiro-HTL, while neglecting the instability of perovskite under acidic condition23,24; Another strategy involves photo-activated oxidation through CO2 reduction25, providing an additional doping pathway, but it remains dependent on the hygroscopic LiTFSI26. Additionally, the use of radical ions structurally similar to tBP has been explored to flexibly tune the energy levels of spiro-HTL, thereby avoiding the use of the detrimental co-additives. However, the practical viability of this method is hampered by considerations of cost and scalability, especially for large-area solar modules13. Ammonium-based TFSI salts or related ionic liquids have also been proven to participate in the oxidation of spiro-OMeTAD. However, the insufficient understanding of the doping process has hindered their widespread adoption27. Besides, the majority of these studies have concentrated on the cations within the dopants, often neglecting or underestimating the role of the abundant, residual TFSI- anions. While it is known that the strong electronegative TFSI- can stabilize the oxidized spiro-OMeTAD•+, its interaction with the underlying perovskite layer has been neglected in most studies28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Here, we investigated the effects of the TFSI additives based on n-i-p structured PSCs. Within HTL, the moderate use of NH4TFSI salt accelerates the doping process of spiro-OMeTAD in solution under visible light without the presence of O2. This process is denoted as the light-accelerated doping treatment (LODT). Within it, tetrahydrofuran (THF) was adopted as a suitable solvent for dissolving both spiro-OMeTAD and various ammonium TFSI salts (ATFSI) and used to partially replace the corrosive tBP for better performances. In perovskite, by incorporating potassium TFSI (KTFSI) into the perovskite precursor solution and octylammonium (OA) TFSI on the perovskite layer resulted in suitable energy level alignment and improved perovskite surface stability. Meanwhile, the combination of OATFSI and NH4TFSI in LODT-HTL facilitates charge transfer from perovskite to HTL, ultimately improving better conductivity in HTL (Fig. 1b, c). In this work, the holistic strategies improved the performance of PSM with a certificated efficiency of 20.95% on a 5 × 5 cm2 substrate (aperture area = 12.83 cm2). Notably, the operational stability was maintained with T97 over 700 h for the small-area solar cell devices in a dry N2 environment without encapsulation (ISOS-L1). This work highlights the significant potential of synergistic utilization of TFSI additives to improve the performance and durability of perovskite photovoltaic devices.

Results and discussion

Phenomena of LODT in ATFSI-spiro precursor solution

Distinguished from the LiTFSI and tBP involving the photooxidation process36,37, protons can effectively react with spiro-OMeTAD (Supplementary Note 1). Most inorganic ammonium compounds can gradually release protons in solution, depending on their acid dissociation constant (pKa). Thus, the proton-containing ammonium cations in TFSI additives were studied.

To systematically probe the acid-doping effect in spiro-OMeTAD, we synthesized a series of ATFSI salts with progressively increasing methyl substitutions on the nitrogen: ammonium TFSI (NH4TFSI), methylammonium TFSI (MATFSI), dimethylammonium TFSI (DMATFSI), trimethylammonium TFSI (TMATFSI), and tetramethylammonium TFSI (TeMATFSI). Considering the strong coordination ability of tBP, which may hinder proton release, THF was chosen as the solvent, efficiently dissolving both spiro and ATFSI (as well as LiTFSI) (Supplementary Fig. 1), while its coordination effect on ammonium is negligible compared to tBP. This provides an appropriate medium to directly probe the interaction between ATFSI and spiro. Specifically, equal molar amounts of ATFSI (0.07 mmol) and spiro were dissolved in THF and subjected to white light illumination.

The light treatment process and proposed reaction are schematically shown in Fig. 2a, b. Control experiments ruled out solvent-induced doping and contributions from trace oxygen or moisture (both <0.1 ppm, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Using a home-built in situ UV-Vis-NIR setup inside a N2 glovebox, we monitored the absorbance changes over time under continuous illumination. The oxidized spiroTFSI and other related oxides displayed distinct absorption signatures compared to pristine spiro, most prominently in the near-infrared region (Supplementary Fig. 4)25. As anticipated, four of the ATFSIs (NH4TFSI, MATFSI, DMATFSI, and TMATFSI) induced clear photo-responses, given by the increasing absorbance signals (Supplementary Fig. 5), whereas TeMATFSI showed a negligible effect because (CH3)4N+ cannot release free protons. Notably, the oxidation ability varied across different cations as demonstrated in Fig. 2c. For example, within 4 min, NH4TFSI and MATFSI resulted in a rapid absorbance growth at 1521 nm, significantly faster than DMATFSI. However, TMATFSI with the lowest pKa, expected to be the strongest oxidant, showed slow absorbance changes, likely due to its inadequate dissociation in THF38. After 4 min, NH4TFSI exhibited a sudden growth in absorbance, which can be attributed to the release of NH3 and thus more release of protons26. Upon THF evaporation in glovebox at room temperature, the resulting doped spiro solids retained the radical features as confirmed by electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy (Fig. 2d), consistent with the UV–Vis results. Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) further confirmed effective p-type doping and conductivity enhancement for most ATFSI except TeMATFSI (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 and Supplementary Table 1). Based on these results, NH4TFSI was selected as the efficient additive for LODT-HTL.

a Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure for the LODT method. Steps (i)–(iv) visually demonstrate the oxidation of spiro in solution (i) after adding different ATFSI to a spiro/THF solution (ii), followed by light exposure (iii), and final oxidation phenomenon observed through solution color change (iv). b Proposed mechanism for the spiro oxidation assisted by ATFSI. Protons are from the ammonium cations, which accelerate the oxidation reaction under light illumination, then forming oxidized spiro+ in THF solution. c Time-resolved UV-Vis-NIR absorption monitoring of the spiro oxidation process with different ATFSIs under white-light LED illumination. The plot shows the percentage increase rate (ΔA) of absorbance (A) relative to the initial absorbance (At=0) at the peak of 1521 nm. d Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra of solid spiro samples doped with various ATFSI salts, confirming the formation of radicals. e, f Decay-associated spectra (DAS) for a pristine spiro film and NH4TFSI doped spiro film. The DAS were obtained from transient absorption spectra (TAS) by global fitting with a tri-exponential function.

To elucidate the role of light in the LODT process, we employed irradiation wavelengths of 365, 450, 550, 650, and 850 nm. Except 850 nm, the shorter wavelengths and stronger light powers lead to faster absorbance growth of spiro solutions (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). This result highlights the role of higher-energy photons in helping with acceleration in the spiro oxidation process efficiently. As the doping mechanism of NH4TFSI involves proton-coupled electron transfer23 from the photoexcited spiro* to spiro+, abundant and higher-energy photons (wavelength of 365 nm equivalent to 3.4 eV) are more efficient in populating the excited state of spiro*. In LODT, the reaction can be presented as: \({spiro}+{{NH}}_{4}{TFSI}\to {spiroHTFSI}+N{H}_{3}\) and light accelerates the reaction of \({spiroHTFSI}+{spir}{o}^{*}{\longrightarrow}^{h\nu}{spiro}+{spir}{o}^{\cdot+}{TFS}{I}^{-}+1/2{H}_{2}.\) Here, the photoexcited spiro* readily transfers an electron to the proton, following with the reduction of the proton to hydrogen, thereby generating the oxidized radical (spiro+ or spiro•+) easily under suitable light activation (Supplementary Note 1). The resulting spiro+ is stabilized by the TFSI⁻ anion, while the deprotonated spiro species remains in the system and can further participate in subsequent reactions. Collectively, the above results demonstrate that light irradiation is an effective method of accelerating the NH4TFSI-induced oxidation of spiro in solution. Then, we performed femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS) to study the oxidation activation process under the light exposure. Pristine spiro-HTL exhibited a broad peak in the range of 420–550 nm (Supplementary Fig. 10f). After doping with NH4TFSI, an additional response emerged within 560–610 nm (Supplementary Fig. 10l), characteristic of the excited state spiro* species36,39. This indicates that pristine spiro, without TFSI⁻, cannot efficiently undergo the excitation-induced oxidation (spiro* → spiro+). Decay-associated spectra (DAS) further support that, and the analysis with triple-exponential fitting revealed that LODT-HTL undergoes a distinct decay pathway leading to oxidized radical cations, indicated by a prominent 530 nm feature from spiroTFSI. In contrast, no similar signature was observed for the pristine spiro (Fig. 2e, f), suggesting the effective doping of spiro-HTL.

Incorporation of THF with tBP in LODT-HTL

The facile doping ability of LODT also relies on the use of THF solvent. However, its rapid evaporation during spin-coating causes undesirable precipitation from NH4TFSI, while adding tBP improves the film quality (Supplementary Fig. 11). To gain the benefits and better understanding of tBP, it is necessary to investigate its specific role in LODT and the interaction with perovskite. Here, we take the resulting solid from LODT and then redissolve it in chlorobenzene (CB) to be consistent with a conventional spiro solution. Meanwhile, to take advantage of THF, various amounts of THF are applied to replace tBP in the following studies.

As shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 12, the absorption peaks of oxidized spiro at 522 and 1521 nm gradually decreased with increasing tBP/THF volume ratios. This indicates that tBP induces detrimental reactions with spiroTFSI, or promotes the de-doping of oxidized spiro. UPS characterization in Fig. 3b further corroborated the phenomena. LODT-HTL without tBP exhibited both deep Fermi level (EF ≈ −4.83 eV) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO ≈ −5.06 eV) levels (with respect to the vacuum level, w.r.t. Evacuum). Upon introducing a small amount of tBP (0.67:1 ratio), both EF ≈ −4.90 eV and EHOMO ≈ −5.17 eV dropped. With further increase in tBP, the EF upshifted gradually, reaching a maximum of –4.41 eV at a 10:1 ratio; meanwhile, the HOMO also shifted upward, saturating at −4.79 eV. The widening of energy differences between the HOMO and EF also suggests that tBP drives a de-doping effect in the pristine p-type LODT-HTL (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14)19. Considering the interaction between tBP and NH4TFSI-spiro, we can explain why, first, a downshift of both work function (WF) and EHOMO at a ratio of 0.67 tBP is observed. This is because even a trace amount of tBP can induce the formation of spiro aggregates, creating donor-acceptor complexes that cause the WF and EHOMO to shift to deeper energy levels40. However, as more tBP is added, its more dominant de-doping effect takes over, causing the apparent WF and EHOMO to shift back to shallower energy levels and increasing the energy differences of | EF–EHOMO | as shown in Supplementary Table 2. However, despite suppressing doping and unfavorable energy-level alignment, increasing tBP enhanced the conductivity of fresh LODT-HTL (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table 3 and 4), which is consistent with the effect from tBP. The tBP reduces the crystalline of NH4TFSI-spiro. But enhance the amorphous tBP-spiro+ component, thus gives easier carrier movement within the film19. Furthermore, to investigate the thermal stability of doped spiro, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) reveals a decrease in the glass transition temperature (Tg) with increasing tBP concentration (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 15e). This effect can be attributed to the plasticizing role of tBP, which intercalates between spiro molecules and weakens intermolecular interactions27. The broader and weaker exothermic peak associated with the formation of crystallization further supports this interpretation as well. While enhanced molecular mobility from tBP may benefit film formation and conductivity, on the other hand, it inevitably compromises thermal stability.

a UV-Vis-NIR absorbance intensity changes of LODT-NH4TFSI solutions prepared with different tBP to THF volume ratios, measured at wavelengths of 522 nm (light-colored bars) and 1521 nm (dark-colored bars). b Fermi level (EF) and the onset edge of the HOMO (EHOMO) positions and their differences ( | EF–EHOMO (eV) |, with respect to the vacuum level, Evacuum) of the corresponding LODT-HTL films as a function of the tBP:THF volume ratios. c Conductivity of LODT-HTL films with varying tBP concentrations (device structure of FTO/PEDOT:PSS/LODT-HTL/Au with an electrode area of 0.16 cm2). d Glass transition temperature (Tg) of the solid LODT-HTL and the relative intensity of the PbI2 diffraction peak (2θ = 12.6°) under normalized intensity of the perovskite (110) peak from the XRD patterns as a function of tBP:THF ratio.

Given the direct contact between spiro solutions and the perovskite surface, we further examined the reactivity of tBP toward perovskite. Owing to the strong coordination ability, tBP rapidly dissolved FAPbI3 single crystals, whereas THF alone shows negligible effect within 2 min, as confirmed by UV–Vis measurements at 400 nm (Supplementary Fig. 16a, b, c). Moreover, XRD analysis revealed that treatment with tBP-containing solutions (without spiro and NH4TFSI) induced PbI2 formation after post annealing, as shown in Fig. 3d (Supplementary Figs. 16d and 17). These results highlight the dual role of tBP in LODT-HTL fabrication: while it promotes HTL formation and conductivity, it simultaneously compromises doping efficiency, energy-level alignment, and perovskite stability. To balance these competing effects. The tBP/THF ratio of 1:1 is adopted primarily to balance perovskite phase stability with the requirement of maintaining suitable energy levels and sufficient thermal stability (Tg = 92 °C) of the HTL.

Management of the perovskite surface with versatile TFSI additives

Beyond its facile doping ability in HTL, it is also important to consider the residual TFSI component as their strong electron negativity can significantly influence the adjacent perovskite surface. Therefore, decoupling the contribution of TFSI salts is essential for a comprehensive understanding of TFSI additives in device behavior.

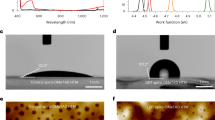

Previous studies41,42 show that K+ cation primarily incorporates into the bulk perovskite while minimal surface influence. This characteristic enables us to isolate the specific effects of the TFSI- anion on the perovskite surface by using KTFSI. We then introduced KTFSI into the perovskite precursor solution and fabricated perovskite layers using both the one-step and two-step methods (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). Laser microscopy, atomic force microscopy (AFM), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that compared with pristine perovskite, KTFSI treated perovskite (KTFSI-PVSK) exhibited a substantial increase in grain size. In particular, the beneficial influences of KTFSI were evident in the two-step method, where the grain size grew from less than 500 nm to over 1 μm. Additionally, the corresponding XRD showed a notable higher intensity at (110) and (220) peak positions (Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 5). The reduced full width at half maximum (FWHM) indicates improved crystallinity after the formation of the perovskite phase with KTFSI doping. To elucidate the role of KTFSI in the perovskite film formation, we tracked the morphological evolution during annealing. SEM images (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Figs. 21–24) revealed that KTFSI significantly promotes grain growth via an Ostwald ripening process, resulting in larger, smoother grains compared to the pristine film yet without affecting the final optical properties (Supplementary Fig. 25). KTFSI was found to enhance the crystallinity of the PbI2 film in the two-step deposition, evidenced by XRD of FWHM at the (001) peak for PbI2 from 0.119 to 0.079 (Supplementary Fig. 26), while also creating a significant porous structure. Such morphology facilitates the complete conversion from PbI2 to perovskite upon reaction with FAI, as confirmed by the near elimination of the residual PbI2 peak (Supplementary Fig. 22b). We also attribute this enhanced crystallinity to a mechanism where TFSI- anions interact with FAI and PbI2, retarding the typically rapid PbI2-FAI reaction. This controlled reaction is related with several factors: potential hydrogen bonds may form between the −CF3 groups on the TFSI- and the formamidinium cation (FA+)43, meanwhile, the oxygen on the TFSI- can coordinate with Pb2+. These interactions create a form of steric hindrance, making the direct and rapid reaction between FAI and PbI2 more difficult and slower44. As the film is heated, the FAI gains enough energy to overcome the binding energy of the TFSI- and Pb2+-TFSI- components. It then gradually reacts with the released PbI2 in a controlled reaction, leading to the formation of larger perovskite grains as illustrated in Fig. 4b. In contrast, without the addition of TFSI-, the reaction proceeds rapidly between PbI2 and FAI, resulting in the faster formation of smaller perovskite grains. Notably, owing to the hydrophobic nature of the TFSI-, it can interact with the intermediate phases during crystallization (Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28). This prevents uncontrolled dendritic growth and promotes the formation of uniformly dispersed crystals (Supplementary Fig. 29). This delayed but improved crystallization process was also confirmed by excitation-emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31), which showed a delayed photoluminescence (PL) signal after annealing for 1 min compared to the pristine, but with a significantly stronger intensity for the final KTFSI-PVSK sample, indicating fewer defects in the perovskite film. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements in Supplementary Fig. 32 (Supplementary Table 6) show a slower charge carrier decay in the KTFSI-doped perovskite, further indicating less defects compared to the pristine perovskite film. The benefit of KTFSI doping was also quantified by space-charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements (Fig. 4d, e and Supplementary Fig. 33), which demonstrated a reduction of trap state density for both electrons (from 2.83 × 1014 cm−3 to 1.74 × 1014 cm−3) and holes (from 1.52 × 1015 cm−3 to 1.14 × 1015 cm−3), confirming the enhanced quality of the KTFSI-modified perovskite films. Dark I–V measurements (FTO/SnO2/PVSK/spiro/Au) further indicated suppressed charge carrier recombination due to reduced defect densities from KTFSI (Supplementary Fig. 34). Subsequently, we investigated the surface energetics of these perovskite films by UPS (Supplementary Fig. 35). Compared to the pristine PVSK, the surface work function of the KTFSI-PVSK film increased from 4.16 to 4.57 eV, and the valence band maximum (EVBM) position shifted from −1.46 eV to a shallower position of −0.88 eV (with respect to Fermi level, w.r.t. EF). The WF changes were consistent with the contact potential difference (CPD) attained (Supplementary Fig. 36), both through Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) and nondestructive Kelvin probe measurement in nitrogen: WFsample = WFtip – CPD. To understand the band alignment, the conduction band minimum (ECBM) is examined by two methodologies. In the first method, we use the optical Eg values determined by the UV–Vis absorption (Supplementary Fig. 25) and the EVBM position to extract the ECBM position (ECBM = EVBM + Eg). Optical bandgaps of two-step deposited perovskite with 1.53 eV were determined for both pristine and KTFSI-PVSK films, indicating that the bulk perovskite films present similar optical properties. The ECBM positions of 0.07 and 0.65 eV were determined for the pristine and KTFSI-PVSK films, respectively. However, the low-energy inverse photoemission spectroscopy (LEIPS) results, a surface-sensitive technique, revealed differences in ECBM values comparing the pristine and KTFSI-PVSK films. ECBM positions based on LEIPS were at ≈0 eV for pristine and ~1 eV for the KTFSI-PVSK films (Fig. 4f, g). The transport bandgap (ECBM – EVBM) values of ~1.5 and ~1.9 eV are calculated for the pristine and KTFSI-PVSK films, respectively. The differences in the transport bandgaps are attributed due to additional perovskite surface modification by the presence of TFSI anions, which are corroborated by the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements discussed below. By comparing the energy level alignment of pristine and KTFSI-PVSK, it is apparent that the EVBM of KTFSI-PVSK is closer to the HOMO level of spiro-LODT HTL, which is favorable for hole extraction (Supplementary Fig. 37).

a SEM images tracking the morphological evolution of a KTFSI-doped perovskite film during a two-step process within 10 min. Scale bar: 1 µm. b Schematic illustration of the proposed mechanism for KTFSI mediated perovskite grain growth. (i) FAI solution spin-coated on the porous, KTFSI-incorporated PbI2 layer. (ii) TFSI⁻ anions inhibited further reaction of FAI with unreacted PbI2 and perovskite intermediate phase. (iii) Larger perovskite grains upon heating from further reaction of FAI with PbI2. Green circles: FAI; Violet polygons: TFSI- ions; Yellow polygons: PbI2 and unreacted perovskite intermediate phase. c Three-dimensional excitation-emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectra of a KTFSI-doped perovskite film during different annealing times, mapping the PL intensity evolution in the 750-900 nm emission range under excitation from 400 to 500 nm. Dark current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of the hole-only devices with FTO/PTAA/PVSK/spiro/Au configuration for d control (PVSK with potassium iodide, KI) and e PVSK with KTFSI (molar equivalent of KI). The trap-filled limit voltages (VTFL) derived from the I-V curves are 1.008 V (control) and 0.752 V (KTFSI), respectively. Combined UPS and LEIPS spectra of the f pristine perovskite and g with KTFSI. WF and EVBM: 4.16 and −1.46 eV for pristine PVSK; 4.57 and −0.88 eV for KTFSI added PVSK, respectively; ECBM are obtained by adding optical bandgap of Eg (1.53 eV) to EVBM (0.07 and 0.65 eV for pristine and KTFSI) and calculated from LEIPS (in brackets, 0 eV and 1 eV, respectively). In situ grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD, ω = 1°) monitoring the evolution of diffraction intensity as a function of angle every minute during annealing for FAPbI3 perovskite films post-treated with h PEATFSI and i OATFSI for 20 min at 70 °C in air.

XPS signals of Pb 4 f orbitals provide differences between the two perovskite films, illustrating a significant shift to lower binding energy, suggesting the interaction from the outer valence electrons (Supplementary Fig. 38, Supplementary Table 7), the shift was not induced by work function differences, considering that the binding energy position of I 3 d was almost unchanged. To determine the remaining components, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) was employed in these pristine and KTFSI-PVSK films. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 39, the perovskite surface with KTFSI additive exhibited significant enrichment of the O and F signal with mass/charge ratios, m/z = 16 and 19, further confirming the presence of TFSI anions on the perovskite surface. To further investigate the interfacial role of TFSI, we analyzed the perovskite/HTL interface by TRPL. The incorporation of KTFSI was found to accelerate charge carrier extractions, where the fast decay component (τ₁) decreased from 107 to 94 ns (Supplementary Fig. 40, Supplementary Table 6). This finding is corroborated by the DAS results, as compared in Supplementary Fig. 41, which also show a faster decay from the excited state to the ground state, further confirming that TFSI facilitates charge transfer to HTL. Furthermore, KTFSI-doped FAPbI3 single crystals with no discernible lattice changes (Supplementary Fig. 42), combing the characterization mentioned above, these provide evidence that the TFSI⁻ is functionalized on the surface of perovskite.

Building on the established benefits of the TFSI⁻ anion, we then explored the abilities of cations in TFSI additives: phenethylammonium (PEA+) and OA+ from PEATFSI and OATFSI, respectively. These cations form 2D-PVSK layers and behave different thermal stabilities. As shown in Fig. 4h, using grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD, incident angle of ω = 1°), post-treatment with PEATFSI initially formed a 2D perovskite phase. However, this phase proved to be thermally unstable, decomposing upon heating, which is consistent with our previous finding45 (Supplementary Figs. 43 and 44). This suggests an ion exchange phenomenon between PEA+ and FA+ cations in the TFSI additive and perovskite. In contrast, post-treatment with OATFSI yields a thermally robust 2D-PVSK layer. During heating, this 2D layer undergoes a stable phase evolution, transitioning from a n = 2 phase (4.1°–4.2°) to a n = 1 phase (3.2°) (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 45). We attribute this improved stability to the larger size of the OATFI cation, which helps preserve the integrity of the 2D phase. Furthermore, we discovered that perovskite films post-treated with OATFSI exhibited the energy level nearly identical to those treated with KTFSI, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 46 and 37a. This is likely attributed to the strong electronegativity of the TFSI-, suggesting that the surface electronic properties are predominantly determined by the TFSI- anions. Furthermore, SCLC measurements (Supplementary Figs. 47 and 33) reveal that surface treatment with OATFSI reduced the hole trap density to a low value of 8.92 × 1014 cm−3. This improvement can be attributed to the formation of a 2D-PVSK layer and additional passivation effect from both OA+ and TFSI- 46. Additionally, water contact angle measurements on the perovskite surface increased from 2.9° to 66.1° with the incorporation of OATFSI, making it more hydrophobic and better protection from humid conditions (Supplementary Fig. 48). This demonstrates that the combination of a suitable cation (OA+) with the TFSI- provides suitable control over the perovskite surface properties. The resulting optimized interface offers an ideal foundation for the fabrication of high-performance devices.

Integrating spiro-LODT HTL and TFSI additive in perovskite for photovoltaic devices

In LODT, although NH4TFSI showed modulated doping capability in HTL, it required further optimization when applied in PSCs. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 49, as the doping concentration increased close to 15 mol%, both WF and HOMO reach to deeper position w.r.t. vacuum level (Evaccum). It is also confirmed that a doping concentration of 15 mol% of NH4TFSI is optimal for LODT HTL in PSC devices, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 50.

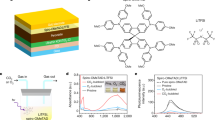

LODT HTL applied in PSCs (Supplementary Fig. 51a) was compared to the conventional LiTFSI spiro-HTL (Supplementary Fig. 51b) and chemically oxidized FK209 spiro-HTL (Supplementary Fig. 51c). The LODT-HTL based PSCs yielded comparable device performance like FK209 doped HTL without relying on air exposure and surface passivation. In contrast to the conventional LiTFSI spiro-HTL, the devices with freshly deposited electrodes exhibited a low fill factor (FF) since the absence of oxygen-doped spiro-HTL. Conversely, notable differences were observed in the device hysteresis behavior between the chemically and light-oxidized devices. To elucidate these distinctions, we compare the PCEs under the reverse (RS) and forward scans (FS) and define the hysteresis index (Hindex) as PCERS/PCEFS. Hindex values closer to 1 indicate lower hysteresis. Clearly, the replacement of Li ions in the LODT-treated spiro-HTL devices resulted in lower hysteresis (Hindex average: 1.008) compared to those subjected to chemical oxidation (Hindex average: 1.048) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 52. In addition, we found that the spiro-LODT HTL was also suitable for different compositions of perovskite films in devices (Supplementary Fig. 53). The best performance was delivered based on the two-step normal bandgap perovskite composition (Eg = 1.53 eV) leading to a champion open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 1.14 V and PCE of 21.2%. Furthermore, we found that OATFSI functions effectively as a dopant in the LODT-HTL (Supplementary Fig. 54) and as a co-dopant with NH4TFSI (Fig. 5a), yielding a high conductivity of 3.625 × 10−3 S/cm (Supplementary Fig. 55). DAS analysis showed that the addition of OATFSI enhanced the photo-excitation process of HTL, reducing the time from 29.6 to 21.3 ps corresponding to the NH4TFSI only HTL (Supplementary Figs. 56 and 10). The improvement benefits hole extraction at the device interface compared with LiTFSI-spiro as confirmed by TRPL (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 40, Supplementary Table 6). However, its ionic liquid properties can lower the Tg of HTL (72.6 °C), compromising its thermal stability (Supplementary Fig. 57). By choosing a minimal amount of OATFSI (1% mol to spiro), maintain a Tg of 90 °C while still improving conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 55). With the optimized concentration of KTFSI as 3 mg/mL (Supplementary Table 8), The champion devices show enhanced performance compared to the control devices. Moreover, the use of KTFSI was found to effectively inhibit hysteresis in devices (Supplementary Fig. 58) and enhanced Voc and FF.

a Absorption spectra evolution of the LODT-spiro solution co-doped with NH4TFSI and OATFSI, showing increased absorbance under continuous white LED illumination within 9 min. The curve was acquired every minute. b TRPL decay for perovskite films covered by a conventional LiTFSI-spiro HTL and the optimized LODT-HTL co-doped with NH4TFSI and OATFSI. c Schematic of PSM architecture alongside a photograph of a fabricated 5 × 5 cm PSM. d J-V curves under reverse (RS) and forward scans (FS) for the control device (with pristine perovskite and conventional HTL) and the target device (with KTFSI-doped, OATFSI modified perovskite, and co-doped LODT-HTL). e, f Long-term operational stability of the control and target devices tested under the ISOS-L-1 protocol (continuous 1-sun illumination at 25 ± 10 °C in a N2 atmosphere without encapsulation).

Based on the optimized co-doped NH4TFSI and OATFSI LODT-HTL, OATFSI passivated interface, and KTFSI as additive in the perovskite layer, we achieved champion PSC devices (target) with Voc = 1.19 V, PCE (RS) = 23.0%, and Hindex = 1.009, with steady-state power output (SPO) PCE of 22.9% after 320 s (Supplementary Fig. 59, Supplementary Table 9), while the control device (employing standard LiTFSI-spiro HTL and pristine perovskite without KTFSI and OATFSI passivation) yielded a PCE of 20.5% (RS) with an active area of on 0.16 cm2 and Hindex = 1.454. The integrated current density Jsc values calculated from external quantum efficiency (EQE) matches with the J-V curves (Supplementary Figs. 60 and 61). Although the remaining KTFSI on the perovskite surface did not improve Jsc due to similar optical absorption, it led to enhanced Voc and FF as a result of smoother energy matching (Supplementary Fig. 37a). To highlight the up-scalability capabilities, we also fabricated PSMs with aperture area of 22.08 cm2, with structure geometrical fill factor (GFF) of 94% (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 62) and the best devices yielded Voc = 9.36 V, PCE (RS) = 20.6%, with Hindex = 1.01, comparing to PCE (RS) = 17.4% with Hindex = 1.58 of control (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). Furthermore, the certified device achieved a PCE of 20.95% on 12.83 cm2 PSM (Supplementary Fig. 63). To the best of our knowledge, this performance stands out as one of the best Li-free spiro-HTL PSMs47 (Supplementary Table 11). Notably, such a low PCE loss induced by upscaling strongly highlights the advantages of the holistic approach for efficient large-scale PSM fabrication. To extend the application of the LODT method to scalable blade-coating processes (D-bar coating), we optimized the relevant coating parameters. This enabled the deposition of highly uniform HTL films, resulting in devices achieving champion PSM performance comparable to the spin-coated method (Supplementary Figs. 64 and 65, Supplementary Table 9). Moreover, the strength of the holistic strategy not only manifests in device efficiencies but also in enhanced operational stability of the devices. The stability results under 1-sun illumination conditions with temperature controlled (25 ± 5 °C) and N2 flow (ISOS-L1) for T80 = 521 h were obtained for large-area PSMs. Moreover, after 700 h, the small-area PSC device kept 97% (T97 = 700 h) of its initial PCE (Fig. 5e, f). More importantly, the thermal operational stability of the devices was evaluated. The encapsulated LODT-based devices demonstrated improved thermal stability, achieving a T90 lifetime of 491 h at 45 °C. Meanwhile, the mini-module exhibits a T75 lifetime of 500 h under 65 °C with encapsulant (Supplementary Fig. 66). This improvement is verified by AFM analysis, with Supplementary Fig. 67 shows minimal morphological change after aging at 65 °C in air for the LODT-HTL. This robustness is a consequence of the higher Tg (Supplementary Figs. 15 and 57) for the LODT method (80.1–90 °C). Additionally, the reduced water content in the solid phase is further evidenced by thermogravimetric and differential thermal analysis, TG-DTA (Supplementary Fig. 68 and Supplementary Table 12). Moreover, the finding also validates the suitability of LODT-HTL on CsPbI3 perovskite (Supplementary Fig. 66 and Supplementary Table 13). These findings confirm that TFSI additives in both HTL and perovskite as an effective and holistic strategy to enhance the stability of spiro-based n-i-p perovskite photovoltaics and warranting further exploration of potentials in ATFSI-based spiro-HTL dopants (Supplementary Fig. 69 and Supplementary Table 14).

Discussion

In conclusion, we developed a holistic strategy based on a distinctive pre-doping approach of TFSI salts in the spiro-HTL layer, denoted as LODT, to avoid the air post-oxidation process48,49. LiTFSI was replaced by NH4TFSI co-mixed with OATFSI, and the tBP amount was reduced by employing THF. Efficient proton-mediated doping was achieved through UV light activation. After decoupling the behavior of anions and cations in TFSI salts, we further introduced KTFSI as an additive into the perovskite precursor solution, and OATFSI to passivate the perovskite surface, resulting in a robust TFSI-passivated perovskite surface and improved energy level alignment in PSCs. We also applied our strategies to large-area PSMs, demonstrating enhanced performance with a 20.95% certified PCE with 12.83 cm2 aperture area. Moreover, after 700 h of continuous operation, the PSCs exhibited only a slight decrease in performance to 97% of its initial PCE. This synergistic and holistic strategy, leveraging versatile TFSI-based additives, not only yields devices with enhanced operational stability but also demonstrates compatibility with upscaled PSM fabrication. Most importantly, we offer a special perspective and the fundamental mechanistic of TFSI additives in advancing spiro-HTL via light doping and interface modulation with perovskite in the n-i-p structure perovskite photovoltaics. Furthermore, our strategies have the technological relevance in considering cost analysis for industrial-scale fabrication (Supplementary Table 15).

Methods

Materials

All reagents were used as received without any further purification

FTO glasses (7–8 Ω/sq., Suzhou ShangYang Solar Technology Co., Ltd and Yingkou OPV Tech New Energy Co., Ltd); Tin(II) chloride dihydrate (SnCl2•2H2O, 99.99%), urea (99.5%); Cesium iodide (CsI, 99.999%) from Sigma Aldrich, lead(II) iodide (PbI2, 99.99%), potassium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (KTFSI, 98%) from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., formamidinium iodide (FAI, 99.99%), methylammonium chloride (MACl, >99.99%), methylammonium bromide (MABr, >99.99%), dimethylamine hydroiodide (DMAI, >98.0%), phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI, 98%) from Greatcell Solar Materials Pty Ltd., n-octylammonium iodide (OAI, 99%, Xi’an Yuri Solar Co., Ltd.); spiro (99.5%), bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide lithium salt (Li-TFSI, 99.95%), tris[4-tert-butyl-2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)pyridine]cobalt(III) tris(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (FK209 Co(III) TFSI salt, 98%), bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (HTFSI, ˃ 99.0%) from, Sigma-Aldrich; Gold (Au, ˃ 99.95%, Nilaco. Co., Ltd.).

Solvents

Acetone (>99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich), thioglycolic acid (TGA, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich); N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, super dehydrated, >99.5%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, dehydrated, >99.0%), isopropanol (IPA, super dehydrated, >99.7%), ethyl acetate (EA, >99.0%), chlorobenzene (CB, 99.8%), hydrochloric acid (HCl) from FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals; Acetonitrile (ACN, super dehydrated, 99.9%), 4-tert-butylpyridine (tBP, 99.9%), tetrahydrofuran (THF, anhydrous, ≥99.9%, inhibitor-free), hexane (anhydrous, 95%) from Sigma-Aldrich; Ammonia solution (NH3•H2O, 28% in Water), methylamine solution (CH3NH2, MA, 40% in Water), dimethylamine ((CH3)2NH, DMA, 50% in Water), trimethylamine ((CH3)3N, TMA, 28% in Wate), tetramethylammonium hydroxide ((CH3)4NOH, TeMAOH, 10% in water) from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of ammonium TFSI salts

The ammonium TFSI salts (NH4TFSI, MATFSI, DMATFSI, TMATFSI, TeMATFSI, and OATFSI) were synthesized by acid-base reaction between HTFSI and the corresponding ammonia in water. Briefly, 1.0 mmol of HTFSI (281 mg) and fresh 1.5 mmol of ammonia aqueous solution were mixed by slowly dropping ammonia solution in the HTFSI immersed in a water/ice bath, then stirred for 4 h. The solvent and unreacted ammonia were removed by rotary evaporator under 60 °C. After obtaining the ammonium TFSI salts, the powder/liquid was dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C overnight; the liquid phase of OATFSI was dried by anhydrous magnesium sulfate; then, the products were transferred into the N2 glove box.

PEATFSI was synthesized by ion exchange of PEAI (0.01 mol) and LiTFSI (0.01 mol) mixed in deionized water. After blending the solution for 4 h, two phases were observed, with the PEATFSI on top. Then, the solution was transferred in a separatory funnel and carefully washed with water for 6–8 times, leaving the top phase each time. For every washing process, PEAI was checked by AgTFSI (0.001 mol/L, in water), until no yellow–white color AgI precipitation appeared. The liquid was still yellow in color because of dissolved I2, CB was added and separated to remove I2 for several times. The remaining liquid was transferred into a rotary evaporator to remove any solvent and dried by MgSO4 (dehydrated). Then, the liquid PEATFSI was transferred to the N2 glove box.

Preparation of LODT-HTL

Seventy-two milligrams spiro-OMeTAD and synthesized ammonium TFSI salt (or LiTFSI) were dissolved in 1 mL of mixed solvents with CB: THF = 100:1 (V:V). Then, the solution was irradiated by UV light (350 nm) for around 5 min until there was no longer a noticeable change of its color. Excessive volume of hexane was added in order to precipitate the oxidized spiro. After filtering, dark brown colored oxidized spiro solids were obtained, which were washed with EA and hexane to remove water and then dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 50 °C. All processes were carried out in an N2 glove box. Alternatively, the reaction product can be collected as a solid powder to facilitate handling and storage for a long period. To do this, we changed the solvent from CB to chloroform. Despite the changes in solvents, the solution preparation procedure was the same unless otherwise noted. The weighted amount of 0.059 mol of solid was mixed with CB and THF with 100:1 (V:V), then tBP with a volume of 1:1 (V:V) tBP:THF was added, without subsequent filtration.

Perovskite solar cell (PSC) fabrication

Electron transport layer (ETL) deposition

The SnO2 ETL layer was deposited by chemical bath deposition (CBD). Briefly, the FTO substrates were sonicated in the sequence of soap water, deionized water (DI water), acetone, IPA, and dried by nitrogen flow. Before the CBD process, the FTO glasses were treated by UVO for 20 min. Then, the FTO glasses were bathed in the prepared CBD solution and heated at 70 °C for 4 h. After washing with DI water, the glasses were annealed on a hotplate at 180 °C for 1 h and ready to be used for PSC fabrication.

Light absorption, perovskite layer deposition

The perovskite layer was deposited on the ETL layer by either a one-step or a two-step method, and all the operation steps were carried out in the atmosphere of the corresponding pure N2 and open dry (20–30% RH) air. Before perovskite deposition, each substrate was treated under UVO for 10 min.

For One-Step

The precursor solution was poured over the substrate and spun at 1000 rpm for 10 s and then spun at 5000 rpm with the acceleration speed of 1000 rpm for 30 s. Then at 25 s, EA was quickly dropped on top of the film. Subsequently, the substrate was annealed in air (20–30 % RH) at 150 °C for 10 min.

For Two-Step

First, the inorganic lead solution was added on substrates and then spined with the speed of 2000 rpm for 30 s. Then, the samples were transferred on a hotplate at 70 °C for 1 min. After cooling down the samples, the organic ammonium solution was poured over the substrate and then spun at a speed of 2000 rpm for 30 s. Subsequently, the samples were annealed at 150 °C for 10 min.

For inorganic perovskite

Equimolar quantities of CsI, PbI2, and DMAI were mixed with a concentration of 0.7 mol/L in DMF. Then, the pre-heated substrate at 70 °C was covered by the solution and spun at a speed of 3000 rpm for 30 s in N2 glove box. The CsPbI3 perovskite was heated at 180 °C for 12 min in air. Then, the perovskite was treated by 3 mg/mL OAI in IPA under the spin speed of 5000 rpm for 30 s. Subsequently, the sample was annealed at 100 °C for 5 min.

For the stability test, the triple cation perovskite layer was deposited on ETL by the anti-solvent one-step method in a nitrogen-filled glove box. The precursor solution was spun on the substrate at the speed of 5000 rpm for 30 s, with the acceleration speed of 500 rpm, then EA was dropped during spinning on top of the substrate after 16 s. Then, the substrate was taken in air and annealed at 150 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, the PEAI solution (5 mg/mL in IPA) was spun on the cooled perovskite layer with a speed of 5000 rpm without further annealing.

Perovskite precursor solution preparation

One-step perovskite solution

Within one milliliter (DMF:DMSO = 8:1), the precursor solution contains 668 mg PbI2, 18.2 mg CsI, and 211.4 mg FAI.

One-step triple-cation perovskite solution

Within one milliliter (DMF:DMSO = 8:1), the precursor solution contains 650 mg PbI2, 18.2 mg CsI, 7.8 mg MABr, 200 mg FAI, and 5 mg MACl.

Two-step perovskite solution

Within one milliliter (DMF:DMSO = 19:1), the inorganic solution contains 645 mg PbI2 and 15 mg CsI. Within 1 mL (IPA), the organic ammonium solution contains 80 mg FAI and 15 mg MACl.

KTFSI doping method

In hybrid-organic perovskite, KTFSI powder was directly added to the precursor solution with different amounts. Here, 3 mg is the optimal concentration for post-treatment.

The investigation of 2D-PVSK was conducted by 5 mg/mL of OATFSI in chloroform. For device fabrication, 0.5 mg/mL OATFSI was adopted and then annealed at 70 °C for 10 min.

All solutions were filtered with a PTFE membrane filter with 0.22 μm pore size.

Hole transport layer (HTL) deposition

The conventional spiro-HTL solution contains 72 mg spiro-OMeTAD, 18 μL Li-TFSI (520 mg/mL in ACN), and 28 μl tBP in 1 mL CB, without filtering. The solution was spun on the perovskite layer at a speed of 3500 rpm for 30 s.

The classical spiro-HTL solution contains 72 mg spiro-OMeTAD, 18 μL Li-TFSI (520 mg/mL in ACN), 28 μL FK209 (375 mg/mL in ACN), and 28 μL tBP in 1 mL CB, without filtering. The solution was spin-coated on top of the perovskite layer at 3500 rpm for 30 s.

The LODT spiro-HTL solution

The preparation follows the above-mentioned steps. As for the OATFSI mixed spiro solution, together with tBP, different amounts of OATFSI were added; the optimal concentration for thermal stable HTL is 1% mol of spiro. The solution was then spin-coated on the perovskite layer with a speed of 3500 rpm for 30 s.

Back contact electrodes deposition

After HTL deposition, the 70 nm thick gold electrode was deposited on top of HTL by thermal vapor deposition under the vacuum (1–2 × 10−5 Torr) condition within about 15 min.

Perovskite solar module (PSM) fabrication

The PSM shares the same fabrication process (two-step method) as the small area PSC, both applied for two-step FA-perovskite and CsPbI3. The only difference is the additional laser processing to connect each sub-cell in series into an integrated PSM. For 5 × 5 cm2 PSM, the P1 is designed with a width of 150 μm. After the deposition of ETL, perovskite, and HTL, the P2 pattern was conducted by laser scribing via a picosecond laser (Picosecond Laser Processing System, LPS-R002A, Spectronix Corporation), to remove layers above FTO. The P3 pattern was defined after gold deposition by a similar laser cutting process to remove gold and separate each sub-cell. The P4 is used when no shadow mask is applied during the test. The design of the patterning lines is shown in Supplementary Fig. 62.

Light stability testing

The PSCs under fixed bias determined by the open-circuit voltage (VMPP) were tested in our home-designed environmental enclosure box under a flow of dry N2. The devices were illuminated by a solar simulator (PEC-L01, Peccel), and the power output was measured continuously using a source meter (Keithley 2401) controlled by a program written in LabVIEW. The thermal stability test was performed in the home-made N2-filled glove box and heat sample directly on a hot plate with a certain temperature. The encapsulation was performed by UV-glued edge with the top transparent glass to cover the electrode side of the devices.

Characterization techniques

XPS measurements were conducted with a photoelectron spectrometer (AXIS Ultra HAS, Kratos) equipped with monochromatic Al Kα (1486.6 eV). SIMS (Kratos Axis ULTRA) is equipped with an Ar+ sputtering gun (1 keV, 50 nA beam current and 100 μm spot size) and a quadrupole mass spectrometer (HAL 7, Hiden Analytical) operated in the positive ion detection mode. Height-amplitude images were acquired with an atomic force microscope (Asylum Research MFP-3D). The surface morphology and cross-sectional images were characterized using SEM (FEI Quanta 250 FEG FEI Quanta 250 FEG). X-ray diffraction measurements were carried out on a Bruker D8 Discover diffractometer (Bruker AXS) using a Cu (λ = 1.54 Å) source with a power output of 1600 W. The ultraviolet visible (UV–vis) spectra were collected on a UV–vis spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-3600 Plus). Crystallization process was confirmed by EEM fluorescence spectroscopy (Horiba Duetta). The J-V characteristics of the PSCs were measured under 1 Sun illumination (AM1.5 G, 100 mW cm−2, calibrated using a KG3 reference silicon cell (Enlitech)), using a solar simulator (Newport Oriel Sol 1 A, xenon lamp, USHIO, UXL-150SO) and a source meter (Keithley 2400). PSCs were fabricated with active areas of 0.16 cm2. An additional 0.16 cm2 metal no reflection black shadow mask was used to define the active area of PSCs. The test procedure is to scan from −0.1 to 1.2 V at a rate of 100 mV s−1. The step of the scan is 0.015 V. The EQE spectra of the devices were obtained from the IVQE8-C model to quantify the current density.

The change of the absorption spectra of spiro solution in THF with different additives was recorded in a nitrogen-filled glovebox a UV-Vis-NIR spectrometer (ULS2048CL-EVO, Avantes) and an NIR spectrometer (AvaSpec-NIR256-2.5-HSC-EVO, Avantes), using 650, 550, 450, and 365 nm Thorlabs LEDs with 10 nm width bandpass filters and a common white light handy LED as excitation light. The probing light was cut off before the sample using the longpass filters with a corresponding chosen excitation light cut-off region (650, 550, 450, and 375 nm, Thorlabs). TRPL test: Nanosecond transient emission measurements were conducted using a Yb:KGW laser (Light conversion, Pharos, 1030 nm, 1 kHz repetition rate, 150 fs, 2 mJ per pulse). The laser beam was directed into the optical parametric amplifier (Light conversion, ORPHEUS) to generate the 450 nm excitation pulse aimed at the sample in the vacuum chamber. And the resulting emission from the sample was collected by the iCCD detector (PI-MAX 4, Teledyne) at a 1 kHz repetition rate and 100 accumulation cycles for a better signal-to-noise ratio. The 475 nm optical long-pass filter was used to eliminate the direct effect of the pump beam. And the dark current background correction was implemented to remove the steady state offset signal.

Contact angle measurements were conducted using a drop shape analyzer (FM 4000, Krüss GmbH, Germany).

KPFM measurements were performed by an atomic force microscope (AFM, Asylum Research MFP-3D, Oxford Instruments) using Ti/Ir-coated Si cantilevers with a nominal spring constant of 2.8 N m−1 (Model: ASYELEC-01-R2). The ultraviolet photoemission spectra (UPS) (He-Iα = 21.22 eV) were collected by a photoelectron spectrometer (XPSAXIS Ultra HAS, Kratos). Low-energy inverse photoemission spectroscopy (LEIPS, ALS Technology Co., Ltd) measurements were performed in a high-vacuum chamber with a pressure of 10−10 Torr. ESR is collected by JEOL ESR Spectrometer JES-X300 at room temperature in a sealed tube with solid samples. Thermal analyzer Thermo Plus Evo2 TG-DTA and DSC Vesta was used to study the thermal stability of spiro. Laser microscopy (Keyence VK-X210) was used to determine the size of PSM and the characterization of perovskite crystals.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data that supports the findings of this study are available in Supplementary Data Files in the Supplementary Information section. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

Burschka, J. et al. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499, 316–319 (2013).

Bai, S. et al. Planar perovskite solar cells with long-term stability using ionic liquid additives. Nature 571, 245–250 (2019).

Jiang, Q. et al. Surface passivation of perovskite film for efficient solar cells. Nat. Photonics 13, 460–466 (2019).

Min, H. et al. Perovskite solar cells with atomically coherent interlayers on SnO2 electrodes. Nature 598, 444–450 (2021).

Park, J. et al. Controlled growth of perovskite layers with volatile alkylammonium chlorides. Nature 616, 724–730 (2023).

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 66). Prog. Photovolt. 33, 795–810 (2025).

Ravishankar, S. et al. Influence of charge transport layers on open-circuit voltage and hysteresis in perovskite solar cells. Joule 2, 788–798 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Thermodynamically stabilized beta-CsPbI3-based perovskite solar cells with efficiencies >18%. Science 365, 591–595 (2019).

Yoo, J. J. et al. Efficient perovskite solar cells via improved carrier management. Nature 590, 587–593 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Inactive (Pbi2)2rbcl stabilizes perovskite films for efficient solar cells. Science 377, 531–534 (2022).

Kim, M. et al. Conformal quantum dot-SnO2 layers as electron transporters for efficient perovskite solar Cells. Science 375, 302–306 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Ion-modulated radical doping of spiro-OMeTAD for more efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Science 377, 495–501 (2022).

Rong, Y. et al. Challenges for commercializing perovskite solar cells. Science 361, eaat8235 (2018).

Park, N. G., Grätzel, M., Miyasaka, T., Zhu, K. & Emery, K. Towards stable and commercially available perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 1, 16152 (2016).

Li, N., Niu, X., Chen, Q. & Zhou, H. Towards commercialization: the operational stability of perovskite solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 8235–8286 (2020).

Ren, G. H. et al. Strategies of modifying spiro-OMeTAD materials for perovskite solar cells: a review. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 4589–4625 (2021).

Schloemer, T. H., Christians, J. A., Luther, J. M. & Sellinger, A. Doping strategies for small molecule organic hole-transport materials: impacts on perovskite solar cell performance and stability. Chem. Sci. 10, 1904–1935 (2019).

Lamberti, F. et al. Evidence of spiro-OMeTAD De-doping by tert-butylpyridine additive in hole-transporting layers for perovskite solar cells. Chem 5, 1806–1817 (2019).

Saliba, M. et al. Cesium-containing triple cation perovskite solar cells: improved stability, reproducibility and high efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1989–1997 (2016).

Ma, C. et al. Unveiling facet-dependent degradation and facet engineering for stable perovskite solar cells. Science 379, 173–178 (2023).

Khenkin, M. V. et al. Consensus statement for stability assessment and reporting for perovskite photovoltaics based on isos procedures. Nat. Energy 5, 35–49 (2020).

Abate, A. et al. Protic ionic liquids as P-dopant for organic hole transporting materials and their application in high efficiency hybrid solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13538–13548 (2013).

Li, Z. et al. Acid additives enhancing the conductivity of spiro-ometad toward high-efficiency and hysteresis-less planar perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1601451 (2017).

Kong, J. et al. CO2 doping of organic interlayers for perovskite solar cells. Nature 594, 51–56 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Impact of lithium dopants in hole-transporting layers on perovskite solar cell stability under day–night cycling. Nat. Energy https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01856-z (2025)

Jung, S. K. et al. Exploiting an interfacial reaction in perovskite solar cells: quaternary alkylammonium ionic salt dopants for spiro-OMeTAD. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2402144 (2025).

Dong, Y. Y. et al. Dopant-induced interactions in spiro-OMeTAD: advancing hole transport for perovskite solar cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 162, 100875 (2025).

Ye, L. et al. Superoxide radical derived metal-free spiro-OMeTAD for highly stable perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 15, 7889 (2024).

Klipfel, N. et al. Mechanistic insights into the role of the Bis(Trifluoromethanesulfonyl)Imide ion in coevaporated p-i-n perovskite solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 52450–52460 (2021).

Kim, Y. et al. Alkylammonium Bis(Trifluoromethylsulfonyl)Imide as a dopant in the hole-transporting layer for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2226–2238 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. Surface passivation of perovskite films by potassium Bis(Fluorosulfonyl) imide for efficient solar cells. Org. Electron. 107, 106544 (2022).

Gkini, K. et al. Influence of TFSI post-treatment on surface doping and passivation of lead halide perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 31291–31300 (2024).

Cao, F. et al. Synergistic ionic liquid in hole transport layers for highly stable and efficient perovskite solar cells. Small 19, e2207784 (2023).

Rombach, F. M., Haque, S. A. & Macdonald, T. J. Lessons learned from spiro-OMeTAD and PTAA in perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5161–5190 (2021).

Kim, S. G. et al. Photo doping of spiro-OMeTAD for highly stable and efficient perovskite solar cells. Joule 8, 1707–1722 (2024).

Shin, Y. S. et al. De-doping engineering for efficient and heat-stable perovskite solar cells. Joule 9, 2542–4351 (2025).

Streitwieser, A. & Kim, Y.-J. Ion pair basicity of some amines in THF: implications for ion pair acidity scales1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11783–11786 (2000).

Goel, M. et al. Homo-homo electron transfer: an elegant strategy for p-type doping of polymer semiconductors toward thermoelectric applications. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003596 (2020).

Fantacci, S., De Angelis, F., Nazeeruddin, M. K. & Grätzel, M. Electronic and optical properties of the spiro-OMeTAD hole conductor in its neutral and oxidized forms: a DFT/TDDFT investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 23126–23133 (2011).

Aranda, C. A. et al. Overcoming ionic migration in perovskite solar cells through alkali metals. Joule 8, 241–254 (2024).

Son, D. Y. et al. Universal approach toward hysteresis-free perovskite solar cell via defect engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1358–1364 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Retarding solid-state reactions enable efficient and stable all-inorganic perovskite solar cells and modules. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg0087 (2023).

Gao, X. X. et al. Engineering long-term stability into perovskite solar cells via application of a multi-functional TFSI-based ionic liquid. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2, 2666–3864 (2021).

Huo, X. M. et al. Unraveling the relationship between the phenethylammonium-induced 2D phase on the perovskite surface and inverted wide bandgap perovskite solar cell performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 8658–8669 (2024).

Wang, H. F. et al. 2D capping layer passivation toward inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite minimodule. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2423397 (2025).

Shin, Y. S. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic determinants of stability in spiro-OMeTAD-based hole-transporting layers in perovskite solar cells: mechanistic insights and strategic perspectives. Adv. Mater. e13270. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202513270 (2025). Online ahead of print.

Hawash, Z., Ono, L. K., Raga, S. R., Lee, M. V. & Qi, Y. B. Air-exposure induced dopant redistribution and energy level shifts in spin-coated spiro-meotad films. Chem. Mater. 27, 562–569 (2015).

Hawash, Z., Ono, L. K. & Qi, Y. B. Recent advances in spiro-meotad hole transport material and its applications in organic-inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1700623 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Energy Materials and Surface Sciences Unit of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, the OIST R&D Cluster Research Program, and the OIST Proof of Concept (POC) Program. G.T. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62474057), Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province, China (2308085QE137), Key Research and Development Plan of Anhui Province (2023t07020005), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JZ2024HGTB0249). Y.B.Q. acknowledges the support from the Global Institute of Future Technology and Zhangjiang Institute for Advanced Study in Shanghai Jiao Tong University. L.M. acknowledges the JSPS postdoctoral fellowship (P24716). The authors thank Dr. Satoshi Takebayashi from the Organometallic Chemistry Group at OIST for helping with collecting single crystal data. We thank the OIST Micro/Nanofabrication Section, Imaging Section, and Engineering Section for the support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.B.Q. conceived the idea and supervised this project. J.Z. conducted experiments, performed the data analysis, and wrote the draft manuscript. G.T. and X.L. fabricated PSCs. P.J. performed UPS and LEIPS measurements. L.M., K.M., D.M., and R.K. helped with the UV–Vis, TRPL, and TAS measurements and related discussion about the results. Y.B.Q., L.K.O., G.T., X.L., H.F.W., S.Y., H.W., T.G., S.M., I.R., X.H., T.W., and T.B. participated in the discussion about the experiments and results. C.Z., C.D., D.S., Z.X., Z.W., Y.L., and Y.Z. helped with manuscript revision. All authors provided valuable suggestions to this work and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shaun Tan, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Liu, X., Wang, H. et al. Synergistic versatile bistriflimide salts in light-accelerated spiro-OMeTAD oxidation and perovskite module photovoltaics engineering. Nat Commun 17, 89 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66752-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66752-2