Abstract

More than 50% of patients with kidney failure undergoing maintenance hemodialysis die within 5 years, a fate unexplained by traditional risk factors. To identify biological risk factors, we analyze 6287 circulating proteins and mortality in 893 participants undergoing hemodialysis in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) and Predictors of Arrhythmic and Cardiovascular Risk in End-Stage Renal Disease (PACE) studies. Proteins are measured shortly after (incident period) and one year after (prevalent period) dialysis initiation. In CRIC prevalent period, Sushi von Willebrand factor type A EGF and pentraxin domain-containing protein 1(SVEP1), R-spondin 4, tetranectin and 24 other proteins attain Bonferroni significance (p < 7 × 10-6). At false discovery rate<0.05, 184 proteins are significant in CRIC; 123/184 remain significant after adjustment for covariates including those linked to inflammation. Pathways related to insulin-like growth factor are prominent. In the pooled CRIC + PACE cohort, prevalent time period, AUC(95%CI) for a 3-protein model of 5-year mortality is 0.826 (0.742, 0.896), compared to 0.629 (0.528, 0.722) for a Cohort Clinical model (p < 0.001). Adding the 3 proteins (SVEP1, R-spondin 4 and tetranectin) to the Cohort Clinical model significantly improves the AUC (p < 0.001). These biomarkers should be validated in future studies and their roles as potential disease mediators elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite implementation of modern guidelines for dialysis efficiency, vascular access and medical management, patients with kidney failure receiving maintenance hemodialysis continue to suffer exceptionally high mortality rates out of proportion to age and conventional risk factors1,2. Patients treated with maintenance hemodialysis for less than 3 months have a 5-year mortality rate of 60%2,3. Compared to such ‘incident’ patients, ‘prevalent’ patients who have undergone three or more months of hemodialysis have slightly better survival4. Patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis represent a wide spectrum of age and comorbidities. Many patients expect hemodialysis to provide a bridge to kidney transplantation, yet only a minority remain healthy enough to meet typical waitlisting criteria or to survive until a deceased donor kidney becomes available. Regrettably, trials of dialysis dose5, new drugs for anemia6 and calcimimetics7 have not shown clear benefit. More than 50% of deaths on hemodialysis are due to cardiovascular disease (CVD)8, yet risk factors observed in populations with normal or near normal kidney function such as dyslipidemia and obesity have neutral or negative associations with CVD outcomes in the kidney failure population9; in fact, large trials of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) showed no benefit for patients undergoing hemodialysis10,11. Antagonists of aldosterone pathways lack the same therapeutic benefits for patients on dialysis as in other populations, and risk worsening hyperkalemia12,13. A novel approach is warranted to identify non-traditional biological risk factors in patients receiving dialysis.

Clinical risk factors and risk scores for death exist in this population, but since they are largely based on non-modifiable factors such as age and comorbidities, their utility lies in predicting costs of care14 or guiding end-of-life discussions15, rather than identifying individuals apt to benefit from a particular therapy. A modified comorbidity index based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index16 was developed by Liu et al.17 for use in incident and prevalent patients undergoing hemodialysis, whereby a score >6 was associated with 40% 2-year unadjusted mortality17. Wagner et al. developed a mortality risk score for incident patients, comprised of comorbidities and routine laboratory measures18. Several additional risk factors are non-modifiable, such as reduced residual urine volume19. Partially modifiable risk factors include markers of malnutrition and inflammation such as lower body mass index, lower serum albumin and higher C-reactive protein20. Identification of modifiable risk factors would greatly benefit this population.

In order to identify biological risk factors for mortality in patients receiving hemodialysis, we conducted a large-scale proteomics investigation of cryopreserved plasma samples from participants undergoing maintenance hemodialysis enrolled in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)-sponsored Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study, and validated our findings in participants enrolled in the NIDDK-sponsored Predictors of Arrhythmic and Cardiovascular Risk in End-Stage Renal Disease (PACE) study. In many different settings, multi-protein risk models predict clinical outcomes as well as or better than traditional clinical models21,22 or genetic scores23. In both cohorts, we thus measured 6287 proteins with SomaScan V4.1, at the first study visit following hemodialysis initiation and then at a subsequent visit for participants who remained on hemodialysis one year later, aligning with incident and prevalent time periods. We prioritized the prevalent time period when the circulating proteome is more likely to have achieved a steady state. Our aims were 1) to rank individual circulating proteins by effect size and statistical significance for their association with the primary outcome of mortality; 2) to ascertain whether a change in circulating protein concentrations predicted mortality; 3) to understand biological themes among proteins associated with mortality; and 4) to construct risk models of mortality based on proteins and compare their performance to clinical models or hybrid clinical-protein models.

Herein, we report the top proteins and biological pathways associated with mortality, and we show that a 3-protein risk model has superior performance to clinical models in these cohorts.

Results

Characteristics of CRIC and PACE participants

Baseline characteristics for participants from CRIC and PACE are shown in Supplemental Data 1. In both cohorts, about 60% were male, and Black participants outnumbered white participants. CRIC participants were older than PACE participants (median[Interquartile range(IQR)] 62[54, 69] vs. 55[48, 63] years), and more CRIC participants had diabetes (74% vs.59%) or prevalent CVD (67% vs. 29%). In both cohorts, most participants had kidney failure attributed to diabetes or hypertension. Fifty-two (13%) of PACE participants had kidney failure due to glomerulonephritis, whereas glomerulonephritis was not specifically adjudicated as a cause of kidney failure in CRIC (active immunosuppression was an exclusion criterion for CRIC enrollment). Fewer PACE participants had arteriovenous vascular access for hemodialysis (34% vs. 68%), and PACE participants had higher parathyroid hormone (PTH) (median[IQR] 428 [273, 621] pg/ml vs 194 [125, 300] pg/ml). Median[IQR] comorbidity index (without gastrointestinal disease, which was not available) calculated as a baseline score in CRIC and PACE were 6 [3, 8] and 4 [3, 6] respectively; scores > 6 correlate with 40% 2-year mortality in prior studies17. Proteomics were assayed at two time points in each cohort. At the first proteomics time point in CRIC, median[IQR] months on dialysis was 5.7 [3.0, 8.2] and in PACE 3.7 [2.7, 5.8]. At the second proteomics time point in CRIC, median[IQR] months on dialysis 18.5 [15.0, 22.8] and in PACE, 17.0 [15.4, 19.4].

Deaths in CRIC and PACE

All-cause 5-year mortality rates subsequent to study baselines in CRIC and PACE were 33% and 40%, respectively (where baseline is the first study visit following hemodialysis initiation, occurring during the incident time period). Subsequent to the second time point (when patients had been on hemodialysis ≥1 year, referred to as prevalent time period), 5-year mortality was virtually identical in CRIC and PACE (40% and 39%, respectively) and CVD death was higher in CRIC than in PACE (14% vs. 10%, respectively). In PACE, sudden cardiac deaths occurred in 7% over 5 years in either time period, and for the current analyses these events are included in CVD deaths. In CRIC, sudden cardiac death was not adjudicated; fewer deaths were attributed to non-cardiovascular causes and more deaths were labelled as “unknown cause” (Supplemental Data 2).

Single proteins associated with mortality in CRIC and PACE

We performed our initial survey using proteins normalized to median absolute deviation(MAD), as it may be more robust for skewed protein distributions. Both normalization strategies are shown in the Supplement, but for clarity only HR per log2 is reported here. In CRIC, we observed higher numbers of significant protein associations in the prevalent compared to the incident time period (184 vs. 80 proteins significant at false discovery rate(FDR) < 0.05), and in PACE, 68 proteins met criterion for validation for the prevalent time period vs. 48 proteins in the incident time period. These findings motivated us to prioritize analyses in the prevalent time period; accordingly, we focus on these results here, while analogous results for proteins measured during the incident time period are found in Supplemental Data 3–5.

Overall, in CRIC prevalent period, there were 27 proteins significant at Bonferroni p < 7 × 10-6 and 184 at FDR < 0.05; over half were inversely associated with mortality (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Data 6–8). In order to prioritize biological risk factors common to CRIC and PACE, we selected 68 proteins significant at FDR < 0.05 in both cohorts, and among these, we focused on 28 proteins with the most extreme hazard ratios(HR), to highlight in Tables 1 and 2. Sushi von Willebrand factor type A EGF and pentraxin domain-containing protein 1 (SVEP1) was directly associated with mortality during the prevalent time period in both cohorts (p < 7 × 10-6). Three of these proteins are related to insulin-like growth factor 1(IGF-1): Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex acid labile subunit, and IGF-1.

Volcano plot illustrates proteins associated with mortality in 436 CRIC participants with kidney failure on hemodialysis ≥1 year, using 14-year follow-up, log2 normalization, no adjustment for covariates. There are 27 proteins significant at p < 7 × 10-6 and 184 at FDR < 0.05. GDF growth differentiation factor, SVEP1:Sushi von Willebrand factor type A EGF and pentraxin domain-containing protein 1, IGFALS insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex acid labile subunit, C7 complement component C7, TGFB1 transforming growth factor-β1. Associations tested with Cox HR and two-sided p-values.

In order to identify factors most likely to generalize across demographic subgroups and to represent specific pathophysiology, we adjusted protein associations for sociodemographics, comorbidities, and markers of malnutrition and/or inflammation. Among 184 proteins significant in CRIC, prevalent time period, at FDR < 0.05, 123 proteins were independently associated with mortality at FDR < 0.05 after full adjustment (Supplementary Data 9). In Table 3, we show 10 proteins selected from Tables 1 and 2, including those positively associated with mortality such as SVEP1 and R-spondin 4, and those negatively associated with mortality such as IGF-1, growth differentiation factor 11/8, tetranectin, and Complement C1q tumor necrosis factor-related protein 3.

Within-subject longitudinal changes in proteins

Overall, absolute and percent within-subject changes in protein levels during an average 1-year interval were small. In CRIC, the median [IQR] absolute change was 11.1 [4.0, 52.3] relative fluorescent units (RFU) per year, percent change: 1.9% [1.1%, 3.4%] per year. To provide context of the magnitude of these changes, the split duplicate median [IQR] aggregate coefficient of variation (CV) was 3.2% [2.4,4.6]; longitudinal change aggregate CV was 8.8% [6.0,13.7] (Supplementary Data 10). In PACE, the median[IQR] absolute change was 15.2 [4.6, 51.4] RFU per year, percent change: 1.9% [0.8%, 4.5%] per year. In CRIC, an increase in chitinase-3-like protein 1(CHI3L), an inflammatory mediator that has been proposed as a marker for atherosclerotic CVD24, was directly associated with mortality at p = 1.2 × 10-6. Changes in insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP) 2 and 5 were associated with mortality at p < 0.01. After adjustment for the protein level at first time point, these had higher significance: CHI3L p = 2.1 × 10-8, IGFBP2 p = 3.7 × 10-7, IGFBP5 p = 8.8 × 10-7 (Supplementary Data 11). In PACE, proteins whose change associated with mortality included SVEP1 (p = 1.1 × 10-5) and neuroligin 1 (p = 6.9 × 10-6), and after adjustment for first protein level, SVEP1 (p = 4.8 × 10-7) and neuroligin 1 (p = 2.7 × 10-6) (Supplementary Data 12). There were 24 proteins whose change in both cohorts was associated in concordant direction of HR above or below 1 at p < 0.05 (Supplementary Data 13).

Functional enrichment of proteins associated with mortality

In order to better understand biological processes underlying the excessive mortality rates in this population, we mapped individual proteins to biological networks using functional enrichment. We selected 144 proteins significant at FDR < 0.1 in both cohorts during the prevalent time period, and performed over-representation analyses using Gene Ontology, Reactome, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Wikipathways. Other than inflammatory pathways, the Reactome pathway related to IGF-1 uptake and transport had the most extreme level of statistical significance (FDR q = 3.2 × 10-10.) Top KEGG terms include the JAK-STAT (FDR q = 1.2 × 10-5) and HIF-1 pathways (FDR q = 2 × 10-4) (Supplementary Data 14). We then queried this same list of 144 proteins in the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins(STRING) interaction database. Of the 154 proteins returned, the largest network was comprised of 55 proteins, including 8 IGF-related proteins and 24 inflammatory proteins. In Fig. 2 we show that multiple biochemical interactions converge on IGF-1.

In the STRING network, red or blue nodes correspond to hazard ratio (HR) > 1 or HR < 1, and node shading corresponds to transformed HR = (-(1/HR)). If the protein is an indirect neighbor other than the 144 list of ‘top hits,’ there is no corresponding HR value and it is shaded in grey. Node size reflects the degree, or number of connections between each protein and other proteins. Proteins related to insulin-like growth factor(IGF) have a yellow border, and inflammation-related proteins a black border. Protein names are listed in Supplementary 14.

Risk models for five-year mortality developed in CRIC, prevalent period

In order to gauge replication for clinical and protein models, we first developed risk models using CRIC for derivation and PACE for external validation. We based the Comorbidity Model on the modified Comorbidity Index published by Liu et al.17 that was developed and validated in >200,000 incident and prevalent patients undergoing hemodialysis. The published score includes diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arrhythmia, malignancy, gastrointestinal bleeding and heart failure. We did not include gastrointestinal bleeding in our model because it was not adjudicated in CRIC or PACE. Our Clinical Model was based on the model published by Wagner et al.18, developed and validated in >5000 patients. Their model is comprised of age, sex, self-reported race, diabetes, etiology of kidney failure, CVD, diabetes x CVD, smoking, and serum creatinine, hemoglobin, albumin, and calcium. We did not include serum creatinine due to missingness of the variable in PACE and a non-significant coefficient for creatinine within the model in CRIC. Complete methods relevant to Comorbidity and Clinical models are found in Online Methods. To treat the clinical and proteomics models similarly, we refit variables in the Comorbidity and Clinical models to CRIC, and these models and refit coefficients were validated in PACE. Variables in the multi-protein and protein-clinical hybrid models were selected using elastic net in CRIC, then coefficients were fit to CRIC using a traditional Cox model and validated in PACE. Elastic net algorithms are described in Online Methods.

Model discrimination and calibration for models developed in CRIC prevalent period are summarized in Fig. 3. In the CRIC 20% testing set, Area Under the Curves(AUC) (95%CI) were similar for the Comorbidity (0.599 (0.48, 0.73)) and Clinical models (0.590(0.47, 0.71)). AUC (95%CI) for a 14-protein model was 0.695 (0.58, 0.81) and for a hybrid model (age + 10 proteins) 0.710 (0.59, 0.82), both numerically higher than Comorbidity and Clinical models without reaching significance of p < 0.05. In PACE, protein and hybrid models validated with higher AUCs than in CRIC (0.709 (0.64, 0.77) and 0.727 (0.66, 0.79), respectively.) In PACE, AUCs for these models were both significantly better than the Comorbidity model, which had an AUC (95%CI) of 0.552 (0.48, 0.65) (p < 0.001), but similar to the Clinical model, 0.694(0.62, 0.76). Variables and coefficients for models fit to CRIC are listed in Supplementary Data 15 and 16.

Data are presented as AUC +/- standard error for risk models predicting time to death occurring within 5-years in participants who have undergone hemodialysis ≥ 1 year(prevalent time period). Top panel: Variable selection and model fitting were performed in CRIC 80% training set, and models were validated in PACE(whole cohort). CRIC AUCs are shown for the 20% testing set (N = 87). CRIC calibration N = 349, PACE N = 230. Bottom panel: Variable selection and model fitting were performed in pooled cohort 80% training set. AUCs are shown for the pooled cohort 20% testing set (N = 133). Calibration was performed in the training sets: N = 530 for clinical models, N = 533 for protein models. The Comorbidity model is based on the index developed by Liu et al.17 and includes diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arrhythmia, malignancy, gastrointestinal bleeding and heart failure. The Clinical model is based on the model developed by Wagner et al.18 and includes age, sex, self-reported race, diabetes, etiology of kidney failure, CVD, diabetes x CVD, smoking, and serum creatinine, hemoglobin, albumin, and calcium. The Cohort Clinical was developed by screening comorbidity and other clinical variables in the pooled cohort, and includes age, log(serum albumin), hemoglobin, log(time since dialysis initiation), triglycerides, BMI, log(PTH), phosphate. The 3-protein model includes SVEP1, R-spondin 4 and tetranectin. Model coefficients are listed in Supplementary Data 15–17. One-sided p-values were obtained with paired bootstrapping t-tests. P-values < 0.001 indicate that, in the 1000 bootstrap replicates, the model AUC exceeded the comparator. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Risk models for five-year mortality developed in the pooled cohort, prevalent period

While high mortality rates lent sufficient statistical power to analyses in separate cohorts, we nevertheless recognized that analyses would be facilitated by a larger sample size in a pooled cohort of CRIC + PACE. For these analyses we refit the variables in the Comorbidity and Clinical models to the 80% training set of the pooled cohort and tested discrimination in 20%. Additionally, we devised a Cohort Clinical Model as a benchmark comparison for protein models. We considered variables included in the Comorbidity or Clinical Model, as well as variables associated with mortality at p < 0.05 in either cohort (diastolic blood pressure(DBP), body mass index(BMI), PTH, LDL-C, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and phosphate) and other plausible factors (HDL-C, systolic blood pressure(SBP), months since starting dialysis, vascular dialysis access) and allowed elastic net to choose predictive variables in the incident or prevalent periods. In order to finalize the Cohort Clinical, Protein, and Hybrid Clinical-Protein models, we ran elastic net in 50 random 80% splits within the original 80% training set and selected factors that recurred in ≥30 of 50 splits and then evaluated AUCs in the original 20% testing set.

For the prevalent time period, the final protein model was comprised of only three proteins: SVEP1, R-spondin 4, and Tetranectin (AUC(95%CI) 0.826 (0.74, 0.90). The Cohort Clinical model included age, log(serum albumin), hemoglobin, log(time since dialysis initiation), triglycerides, BMI, log(PTH), phosphate (AUC(95%CI) 0.629 (0.53, 0.72)). The AUC for the 3-protein model was higher than AUCs for all three clinical models (p < 0.001 for all). The AUC(95%CI) for Cohort Clinical model combined with the 3 proteins was 0.778 (0.70, 0.85), significantly better than Cohort Clinical model alone (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). We allowed elastic net to choose among all proteins, and all clinical factors in the three models, and the resulting best risk model included the 3 proteins in prior model and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1, but no clinical factors (AUC(95%CI) 0.825 (0.74, 0.90)). Calibration for the 3-protein model is shown in Fig. 4, (p = 0.67). Variables and coefficients for pooled cohort models are enumerated in Supplementary Data 15 and 17.

Deciles of predicted risk are plotted alongside observed risk in the full pooled cohort (CRIC + PACE, N = 655), for the 3-protein model predicting time to death occurring within 5-years, among participants who had already survived ≥1 year on dialysis (prevalent time period). Calibration p = 0.673. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Sensitivity analyses and alternate time horizons for the three-protein model

Using coefficients fit to 5-year mortality, prevalent period, we evaluated 5-year mortality AUCs for the 3-protein model in various subgroups of the pooled cohort (all AUCs calculated in 20% test sets). AUC(95%CI) for incident period was 0.795 (0.73, 0.86), and while performance was similar in subgroups of age, race, prevalent CVD, diabetes, and Comorbidity Index, the AUC(95%CI) was lower in women (0.631 (0.48, 0.78) (p = 0.04)) (Table 4). AUCs(95%CI) for the final 3-protein model of 5-year mortality evaluated separately in CRIC and PACE testing sets, prevalent period, were 0.839 (0.74,0.92) for CRIC, and 0.855 (0.73,0.96) for PACE. For incident period, testing sets, AUC(95%CI) were 0.808 (0.71,0.89) for CRIC, and 0.777 (0.68, 0.87) for PACE. For 2-year mortality, pooled cohort, prevalent period, AUC(95%CI) was 0.823 (0.71, 0.92). For 10-year mortality (CRIC, prevalent period), the AUC(95%CI) was 0.827 (0.74, 0.90).

Risk models for mortality developed for incident time period

When risk models were trained during the incident period, we observed that clinical factors had higher or equivalent prognostic utility compared to proteins. For example, in CRIC, AUC(95%) for age alone was 0.730(0.60, 0.84). AUC(95%CI) for the Comorbidity model was 0.730(0.61, 0.84), and the Clinical model was 0.725 (0.61, 0.83). Replication in PACE for the Comorbidity model yielded an AUC of 0.512(0.46, 0.58) and Clinical model 0.673 (0.62, 0.73). In the pooled cohort we implemented training of models over 50 splits, yielding a Cohort Clinical model that included BMI, log(serum albumin), phosphate, hemoglobin, PTH, log(calcium) (AUC(95%CI) 0.611(0.54, 0.68)), and a 5-protein model (R-spondin 4, Villin 1, Interleukin 8, Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase, T-complex protein 1 subunit epsilon) (AUC(95%CI) 0.658 (0.58, 0.74)). Variables and coefficients of the models developed or fit in the incident period are shown in Supplementary Data 15–17.

Discussion

We present what is, to our knowledge, the largest proteomic study performed to date in patients with kidney failure undergoing hemodialysis, incorporating 9.8 million protein measures performed during incident and prevalent time periods relative to hemodialysis initiation, in 893 study participants in two separate cohort studies sponsored by the National Institutes of Health(NIH). Proteomics assayed in CRIC during the prevalent period, when patients had been on hemodialysis ≥1 year, yielded 184 proteins significant at FDR < 0.05, of which 68 replicated in PACE. SVEP1, R-spondin 4 and tetranectin were among 27 proteins that reached Bonferroni significance of p < 7 × 10-6 in CRIC over 14-year follow-up, and a risk model for 5-year mortality of these three proteins yielded higher discrimination than models comprised of clinical factors.

Many proteins showed inverse associations with death. Circulating IGF-1 concentrations were inversely associated with mortality whereas IGFBPs were directly associated with mortality in both cohorts, for both incident and prevalent time periods (Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Data 5). IGF-1 may play roles in multiple biological networks represented among proteins associated with mortality (Fig. 2). IGF-1, also known as somatomedin C, mediates the effects of growth hormone. It has widespread effects, including promoting skeletal muscle growth25 and an anti-inflammatory effect on the endothelium, potentially protecting against atherosclerosis26. In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), lower circulating IGF-1 concentrations may be due to decreased clearance of IGF-1 binding proteins, which lowers the levels of bioavailable IGF-1; this functional deficiency contributes to several complications of CKD, including growth failure in children27.

SVEP1, R-spondin 4 and tetranectin have not previously been considered protein biomarkers in studies of patients undergoing hemodialysis. SVEP1 was directly associated with mortality in both cohorts during incident and prevalent periods (p < 7 × 10-6 for both cohorts in the prevalent period.) In PACE analyses, between two proteomic time points, an increase in SVEP1 was associated with mortality at p = 4.6 × 10-8. SVEP1 is an extracellular matrix protein found in vascular smooth muscle that has been shown in Mendelian randomization and animal studies to be atherogenic28. Its role in atherogenesis is not entirely understood, but may involve platelet activation29. SVEP1 may mediate mortality in patients with kidney failure by promoting atherosclerotic CVD. R-spondin 4 was directly associated with mortality in both cohorts, prevalent period (CRIC unadjusted HR per log2 2.5, p = 2.5 × 10-10, adjusted HR 2.0, p = 1.8 × 10-4; PACE unadjusted HR 2.5 per log2, p = 5 × 10-4.) R-spondins 1-4 are secreted activators of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway that induces atherosclerosis30. Tetranectin was inversely associated with mortality in both cohorts, both time periods (CRIC prevalent unadjusted HR per log2 0.29, p = 2.5 × 10-10, adjusted HR 0.42 p = 3.7 × 10-4; PACE unadjusted HR 0.29 per log2, p = 0.004). Tetranectin is a plasminogen binding protein involved in fibrinolysis. It is detected in myocardium, and may play a role in myocardial fibrosis31. Circulating concentrations were inversely associated with risk of cardiovascular outcomes in the Framingham Heart Study32.

Other than CVD, sepsis is the most common cause of death in patients with kidney failure on hemodialysis8. Patients are at high risk of infection, not only due to use of tunneled catheters for dialysis access, but also relative immune deficiency33. Notably, in our functional enrichment analysis, two highly significant Gene Ontology terms were Regulation of immune system process (FDR q = 1.8 × 10-10) and Regulation of T cell activation (FDR q = 3.1 × 10-9) (Supplementary Data 14). Such pathways may have roles in both CVD and infection, since inflammatory mediators produced as a protective reaction to infection could conceivably have adverse effects such as reducing levels of potentially protective factors such as IGF-125 or hastening atherosclerosis34.

For 5-year mortality in the pooled cohort, prevalent period, the sparse 3-protein model had significantly better discrimination (AUC(95%CI) 0.826 (0.742, 0.896) than the cohort clinical model (AUC (95%CI) 0.629 (0.528, 0.722) (p < 0.001)). Adding the 3 proteins to the cohort clinical model improved the AUC(95%CI) to 0.778 (0.70, 0.85). The difference in AUC of 0.15 exceeds smaller improvements to AUCs observed in studies where, for example, an increase of 0.05 was considered clinically relevant35. The model’s performance was similar for incident period: AUC(95%CI) of 0.795 (0.725, 0.857). The advantage of creating sparse protein models by performing iterative stability analyses on proteomic datasets has been shown in recent studies36,37. While these results should be interpreted with caution, given this 3-protein model was developed in the pooled cohort and has not been externally validated, we are encouraged by the excellent performance of proteomic modeling. First, preliminary multi-protein risk models had even higher AUCs in PACE validation than in CRIC derivation, despite differences in age and comorbidities between the two cohorts. Furthermore, the 3-protein model developed in the pooled cohort performed equally well in CRIC and PACE. Nonetheless, the model’s generalizability should be tested in external cohorts in future studies. Second, the higher AUC of protein models in the prevalent cohorts suggests they might best serve patients who have survived at least one year on hemodialysis. One might hypothesize that protein concentrations have higher variability shortly after hemodialysis initiation due to fluid removal, downstream changes in response to infection-related complications, procedures to establish vascular access, and treatment of anemia and disorders of bone and mineral metabolism. Reduced or absent residual urine volume is a risk factor for mortality in this population19 and also a physiological determinant for low molecular weight proteins. Since residual urine volume is minimal in most patients after one year on hemodialysis, this could have reduced physiological heterogeneity during the prevalent period. While the AUC for the 3-protein model was highest in the prevalent period, it is notable that in the pooled cohorts, incident time period, the 3-protein model yielded an AUC(95%CI) of 0.795 (0.725, 0.857). If models are developed in larger cohorts, there is potential to optimize protein or hybrid models for incident as well as the prevalent time periods. The subgroup analyses of the 3-protein model suggest diminished discrimination in women. Although our subgroup analysis had few women, stratification by self-reported sex should be considered if the model is tested in larger cohorts.

We propose that protein models could be developed and validated in external cohorts as potentially modifiable risk stratification tools, which are currently not available in this population. As compared to static factors such as age, sex, or most comorbid conditions, proteins are more likely to vary in response to patient’s diet38, medications39, or adherence to dialysis. The participants in the highest deciles shown in Fig. 4, with >80% risk of dying over 5 years, could be selected for closer monitoring, alternate dialysis regimens or trials of new therapies. The nephrologist could monitor the patient’s risk score longitudinally and show whether better adherence has lowered the patient’s risk of death; such information could be used as tool to motivate patients to adhere to recommended strategies. If evidence of pathogenicity for certain proteins is shown in future studies, clearance of such proteins during hemodialysis could be desirable, but would depend on the proteins’ molecular weight and protein binding. While conventional hemodialysis permits clearance of small molecular weight proteins with low protein binding, hemodiafiltration removes middle weight molecules, and thus could remove smaller proteins <50 kDa listed in Tables 1 and 2. Future studies could establish whether hemodiafiltration removes specific injurious proteins more efficiently than hemodialysis, or if maneuvers such as ultrapure dialysate or high-volume hemofiltration influence a protein risk score. It is possible that a protein-based risk model could then be used to ascertain which patients would likely benefit from hemodiafiltration rather than conventional hemodialysis.

This observational study does not support causal inferences about the proteins’ effects on disease processes. While a significant hazard ratio in this type of analysis could reveal a causal factor, it could also reflect a compensatory or confounding process. Nevertheless, it is notable that several proteins highlighted here have been studied in other populations, and some have established or experimental drug ligands. A query in the Therapeutic Target Database returned 3 approved, 16 clinical trial and 2 preclinical drugs for IGF-140. IGFBPs bind circulating IGF-1, and their roles in CVD are under investigation41,42,43. Neuroligin 1 (aka neuregulin) emerged in the longitudinal analyses in PACE, in that higher Neuroligin 1 was associated with death at p = 3.0 × 10-6. This protein has homologous regions with epidermal growth factor, and the NRG1β variant is thought to be protective against atherosclerosis, cardiac remodeling, and possibly arrhythmia, the latter effect via ErbB receptors influencing potassium channels44. Neucardin, a recombinant Neuroligin fragment has been fast-tracked by the FDA as a heart failure therapy (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/ NCT05949801), and a small molecule ligand is in development45. Overall, 13 proteins among our top protein biomarkers have established or experimental drug ligands (Supplementary Data 18).

Our study has many strengths. CRIC and PACE are prospective observational studies funded by the NIH with excellent phenotyping of the participants initiated on hemodialysis. The studies are distinguished by the care with which blood samples were collected and meticulous collection of clinical data and outcomes, which undoubtedly contribute to the high statistical significance and fidelity of protein associations between CRIC and PACE. The heterogeneity between CRIC and PACE is also a strength, representing the diversity of patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis and augmenting generalizability of results. Our previously published quality control studies of assay and within-subject variability46, coupled with the excellent validation in the current analyses, support validity of our findings. A unique perspective is gained by fitting each clinical and protein model to the derivation cohort and performing external validation, facilitating a head-to-head comparison of clinical and protein models.

Limitations and future directions

We also acknowledge limitations. The final 3-protein risk model for 5-year mortality was developed in the pooled cohort, and we currently lack a source for external validation. This model would need to be externally validated to show whether its superiority to clinical models is consistent in other populations. Since both CRIC and PACE study visits were conducted on non-dialysis days, dialysis-related data are sparse (i.e., Kt/Vurea, hours of dialysis prescribed, residual urine volume, erythropoietin stimulating agent dose). Volume status ascertained using bioimpedance, ultrafiltration volume, and/or interdialytic weight gain were not available and thus we could not evaluate the role of volume status on the proteome or clinical risk models. We realize that incorporating time-varying anthropometrics and clinical labs may improve prognostic utility of clinical data47; however, we focused on single time point risk factors because they are more practical for clinicians. High mortality rates contributed statistical power to the analyses, but the relatively small sample sizes limited sub-group analyses. We did not analyze cause of death, which limits speculation regarding the pathobiology of proteins for specific disease processes; moreover, causal effects cannot be inferred from this observational study. The effect of a hemodialysis procedure on the circulating proteome, and a parallel investigation of patients on peritoneal dialysis, were beyond the scope of this manuscript and should be the subject of future studies.

In conclusion, these analyses demonstrate the capacity for large-scale proteomics to identify numerous new biomarkers and potential mediators of mortality in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Particularly in the prevalent time period, multi-protein risk models of 5-year mortality demonstrate better performance than clinical models. Future studies are needed for external validation of the final protein model and should additionally elucidate the extent to which predictive proteins may cause disease and whether they can be modified by medications or dialysis procedure.

Methods

Ethics statement

The CRIC and PACE studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating centers and the research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants provided written informed consent. For these analyses, Principal Investigator Dubin obtained additional IRB approval at UT Southwestern Medical Center. All study participants provided written informed consent that included use of their data for analyses reported here.

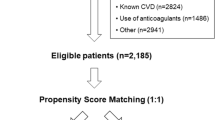

Participants

The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study was designed to investigate risk factors for progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), incident CVD, and overall mortality in persons with CKD48. Between 2003 and 2008, the CRIC study enrolled a total of 3,939 ethnically diverse men and women at 13 sites affiliated with 7 clinical centers, ages 21–74 years, with eGFR 20–70 ml/min/1.73m2 by the simplified (4-variable) Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation48. Eligibility criteria and baseline characteristics of the CRIC cohort have been published48,49. The CRIC study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating centers and the research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were compensated, and compensation was determined by study sites. Between 2004 and 2020, 1123 CRIC participants reached kidney failure and started dialysis. Among these participants, 251 (22.4%) had no further study visits and another 232 (20.7%) provided no blood samples after starting dialysis. Due to the potential interference of lupus antibodies with aptamers (communication from SomaLogic), we excluded 10 (0.9%) CRIC participants with systemic lupus erythematosus. For the present analysis, we included 630 CRIC participants with kidney failure receiving maintenance dialysis, enrolled from all 13 sites at 16 different study visits (Supplementary Data 19). We ran SomaScan V4.1 on plasma EDTA samples drawn at the first study visit following initiation of dialysis; we assayed samples on 421 (66.8%) participants who remained on hemodialysis a mean of 1.1 ± 0.8 years following the first proteomics sample. In order to harmonize CRIC and PACE on dialysis vintage (time since initiation of dialysis), we categorized CRIC blood samples in either the incident time period (i.e., <1 year, n = 483) or prevalent time period ( ≥ 1 year, n = 436). Ninety-seven percent of CRIC participants had hemodialysis thrice weekly; based on post-hoc interviews with CRIC study sites, approximately 80% blood samples were drawn on a non-dialysis day, (with the remainder drawn on the dialysis day prior to initiation of the hemodialysis procedure). Seventy-five percent of CRIC participants were fasting at the time of blood draw. Blood was promptly centrifuged and sent on dry ice to the Central Lab at University of Pennsylvania where it was aliquoted and stored at -80oC.

Predictors of Arrhythmic and Cardiovascular Risk in End-Stage Renal Disease (PACE) was designed to study risk factors for sudden cardiac death in patients with kidney failure who had recently been started on hemodialysis. PACE enrolled participants from 27 dialysis units in the Baltimore area; there were four annual study visits over the course of 2008–2012. Participants were ≥18 years old, English-speaking, and had initiated thrice weekly in-center hemodialysis fewer than six months earlier. Exclusion criteria included cancer, presence of pacemaker or automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator, and other criteria previously described50. Information on glomerulonephritis, but not specifically lupus, was collected in PACE. We assayed SomaScan 4.1 on plasma EDTA samples from 418 participants at Visit 1 and 229 participants from Visit 2 (separated by mean (SD) 1.1 (0.2) years). Ninety-nine percent of PACE participants had hemodialysis thrice weekly; PACE blood samples were collected on a non-dialysis day, specifically 73% were collected one day after, 18% two days after, 6% three days after, and 3% four days after the last hemodialysis session. Participants fasted for blood draws. Plasma tubes were centrifuged immediately and stored in a -20oC freezer; within 2–4 hours, samples were aliquoted and transferred to a -80oC freezer.

SomaScan assay and quality control

SomaScan is an assay based on modified aptamers, which are chemically modified single strands of deoxyribonucleic acid ~40 nucleotides long, as binding reagents for target proteins51,52,53,54,55,56. Modified aptamers bind to proteins with high affinity similar to antibodies (lower limit of detection 10-15 moles per liter.)51,53,54 “Pull-down” studies, in which the aptamer-protein complexes were isolated and the identities of the bound proteins were verified by targeted mass spectrometry and gel electrophoresis, have been performed for 920 proteins among 1305 proteins in a previous version of the assay55. These studies showed that >95% of aptamers correctly targeted the intended proteins (for those proteins in concentrations sufficient to be detected by mass spectrometry). Samples on the SomaScan assay are run at three different dilutions to assay each analyte within its linear range of concentrations. Assay results are quantified on a hybridization microarray and reported in relative fluorescent units (RFU). SomaLogic has procedures for data calibration, standardization and internal controls, typical of microarray technologies. SomaLogic normalizes the entire protein dataset using Adaptive Normalization by Maximum Likelihood (ANML) to remove unwanted biases in the assay. ANML is an iterative procedure that adjusts values for analytes that fall outside expected measurements from a reference distribution46.

The SomaScan V4.1 menu includes 7596 aptamers. We excluded 308 aptamers paired to non-human proteins, and 117 incompletely characterized investigational aptamers. Circulating concentrations of numerous analytes are 2- to 10-fold higher in patients with kidney failure compared to those without kidney disease. We excluded about 0.4% of aptamers (32 for CRIC, 31 for PACE) that saturated the SomaScan assay due to high concentrations. We included split duplicates of CRIC samples in CRIC batches to allow for quality control. There were four proteins with intra-assay CV > 50% in these duplicates, and these were excluded from CRIC and PACE analyses. Given that some proteins are measured by two or more aptamers, we analyzed 7135 aptamers (6287 unique proteins) in CRIC, and 7140 aptamers (6291 unique proteins) in PACE. Proteins included in the SomaScan V4.1 menu, and the reasons we excluded any protein, are listed in Supplementary Data 20. SomaScan intra-assay CVs from plasma of healthy individuals are reported as ≤5%57,58. We previously published a quality control study of proteins in the SomaScan 4.0 platform46 (4607 unique proteins) in plasma samples of 40 participants of the Cardiac, Endothelial Function and Arterial Stiffness in End-Stage Renal Disease (CERES) study. Median [IQR] intra-assay CV was 2.4% [1.8%, 3.4%]. Median[IQR] inter-assay CV was evaluated by inserting CERES blinded, duplicate samples in batches of CRIC and PACE samples run approximately one month apart, and was 7.4% [4.6%, 13.1%]. In CERES samples, short-term within-subject CV over one week was 5.8% [3.4%, 9.7%]. Also using CERES data, we explored the ANML data format versus raw formatted protein data for 1) assay variability and 2) protein fold change in those who died versus survived over 2.5 years. Technical and short-term biological variability in paired samples were lower when we used ANML-formatted data, but fold-change in survivors was minimally affected by ANML format46. We chose to use ANML formatted data for the current analyses in CRIC and PACE to facilitate comparison to other studies. In the present study we also analyzed intra- and inter-assay CVs for the 2298 proteins in the Somascan 4.1 that were not in version 4.0: median intra-assay CV was 3.3% and inter-assay CV 7.9%.

Study outcomes and censoring

In CRIC, outcome events were reported at 6-month intervals, and the specific event dates were confirmed by adjudication of medical records. Deaths were ascertained from next of kin, death certificates, obituaries, hospital records, the Social Security Death Master File, and the National Death Index. Mortality outcomes for this analysis were adjudicated through May 202059. In CRIC, survival time was censored for kidney transplantation (N = 94 participants for time starting from first visit). Participants were queried about dialysis modality at each study visit, and those who had changed to peritoneal dialysis were not included in the samples from the first or second time point. However, dialysis modality was not specifically documented on the dates of clinical outcomes.

In PACE, all-cause mortality was ascertained using reports from dialysis units confirmed with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Form 2746. Outcomes for the current study were adjudicated through May 2014. In PACE, survival time was censored at kidney transplantation (N = 66 for time starting from first visit) or change to peritoneal dialysis (N = 19 during time starting from first visit).

Covariate definitions

In CRIC, sociodemographic data were obtained at baseline using self-reported questionnaires, including self-reported sex, self-reported race/ethnicity, and smoking status. Comorbidity data by self-report were updated at each study visit. Diabetes mellitus was defined by a fasting glucose of ≥126 mg/dL or the use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications. Hypertension was defined by a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, or the use of antihypertensive medications. Prevalent or new onset CVD was assessed at each study visit (including study visits for patients who had initiated dialysis for the current analysis) by a self-reported history of prior myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart failure, stroke, or peripheral artery disease. Body mass index was calculated using measured height and weight and expressed in kilograms per meter squared. Serum lipids and phosphate were measured at study baseline (concurrent with proteomic assays during the incident time period), at CRIC Central Lab specifically for the current study.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics and protein normalization

Continuous values of participants’ baseline characteristics were summarized as median[IQR]. We utilized SomaScan protein values measured in relative fluorescent units that had been normalized using ANML, with subsequent median absolute deviation (MAD)-based standardization and Winsorizing (outlier clipping) at the median ± 5 MAD, as we have previously published22. For a data set, \({x}_{1},\,{x}_{2},\,{x}_{3},\,\ldots,\,{x}_{n}\), the MAD is defined as the median of the absolute deviation from the data’s median: MAD = median( | \({x}_{i}\) - \({x}_{{median}}\) | ), where \(i\) = \({{\mathrm{1,2,3}}},\ldots,n\), and \({x}_{{median}}\) is the median of the data set. For each protein, we first capped the extreme values +/-5 x MAD and then standardized it by subtracting the median and dividing by the MAD.

Imputation for missing clinical or laboratory variables

We performed multiple imputation in most instances of missing variables, which are listed herein as (% missing at incident time point, % missing at prevalent time point). We applied multiple imputation using chained equations as implemented in the R package mice. Five imputed datasets were created with synthesized estimates and attendant standard errors obtained via Rubin’s pooling method. For CRIC, multiply imputed variables were SBP (4%, 6%), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (5%, 7%), phosphorus (0%, 52%), hemoglobin (6%, 2%), calcium (4%, 1%), albumin (4%, 1%), while for PACE multiply imputed variables were SBP (8%, 11%), DBP (8%, 11%), body mass index (1%, 11%), as well as laboratory markers that were missing in 12% of patients at the prevalent time point in PACE (PTH, phosphorus, hemoglobin, calcium, serum albumin.) Imputation for missing C-reactive protein (CRP) in CRIC (99%, 97%) and PACE (8%, 98%) was performed using a regression model developed in PACE participants possessing both aptamer and traditional assays. (PACE rho for CRP = 0.89) In CRIC, PTH (78%, 84%) was based on a regression model developed in CRIC participants with both aptamer and traditional PTH assay. (CRIC rho for PTH = 0.80). Lipids (low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C), triglycerides, total cholesterol) were missing in a majority of participants at 2nd time points for both cohorts: CRIC (1%, 66%) and PACE (8%, 98%). We performed an elastic net regression on all SomaScan proteins separately in CRIC and PACE for samples with aptamers and measured lipids, and then utilized the elastic net model to calculate imputed lipid values for missing values in the respective cohorts. Scatterplots for aptamer-based values and traditional assay values of PTH, CRP and lipids are shown in the Supplementary Data 21. For missing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or malignancy status in the modified CI, we used the modal value from corresponding visit. For missing COPD or malignancy status in the modified CI, we used the modal value from corresponding visit. These were implemented in CRIC, missing COPD (1%, 3%), and malignancy (1%, 2%); and in PACE missing COPD (2%, 2%), and malignancy (0.48%, 2%). Hybrid clinical-protein models were developed using elastic net, which is not amenable to multiply imputed variables. These hybrid models were developed on datasets utilizing the median value at corresponding visit for hemoglobin, albumin and calcium, which were missing in <5% of participants, except the PACE second visit at which these were missing in 12% of participants.

Reliable imputation was not feasible for the following variables, and we did not utilize them in the analyses. For CRIC, these included: Kt/Vurea (55%, 65%); arteriovenous fistula or graft versus tunneled catheter for hemodialysis access (14%, 11%), use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents (49%, 59%), heart rate (32%, 30%). For PACE, these included: serum creatinine concentration (20%, 100%), arteriovenous fistula or graft versus tunneled catheter for hemodialysis access (1%, 100%); hemodialysis session frequency(1%, 100%); Kt/Vurea (7%, 13%); erythropoiesis stimulating agents use (3%, 11%).

Single protein associations with mortality

The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the association between individual proteins and survival time. We chose to select ‘top hits’ from among the protein associations (Hazard Ratio (HR) per MAD) with a false discovery rate obtained via the Benjamini-Hochberg method) threshold of FDR < 0.0560,61. Top hits are presented as HR per log2, a more widely used standardization that facilitates interpretation of effect size. Proteins which also achieve Bonferroni-corrected significance (p < 7.0 × 10-6 after adjusting for ~7000 tests) are indicated. For 184 proteins measured during the prevalent time period in CRIC meeting FDR < 0.05, we performed multivariable adjustment with a model comprised of age, sex, race, diabetes, CVD, history of hypertension, tobacco use, dialysis vintage, SBP, DBP, BMI, calcium, hemoglobin, PTH, albumin, LDL-C, triglycerides, total cholesterol and CRP. We included covariates that were associated with mortality in CRIC at p < 0.05, with the following exceptions: we included SBP, and dialysis vintage because of biological plausibility; and we included diabetes, hemoglobin and calcium due to associations observed in PACE but not CRIC. We analyzed change in protein between first and second time points in association with deaths occurring after proteomics time point 2, as HR per annual change in RFU, and HR per annual percent change, each presented with and without adjustment for level of protein as first time point.

Functional enrichment and network analysis

To better understand biological pathways represented by our ‘top hit’ proteins, we performed functional enrichment for 144 proteins measured during the prevalent time period that replicated at FDR < 0.1 in both cohorts. First, we applied over-representation analysis (ORA) using the databases of Gene Ontology (GO), Reactome and KEGG. ORA is used to determine the proportion of proteins within a particular GO term (a biological pathway typically comprised of >5 gene names) that are found among the group of 144 ‘top hit’ proteins, and compare this proportion to the proportion that would be found using the background of all proteins measured by SomaScan. For a given protein that was measured by two or more aptamers, we employed the aptamer measurement with the largest effect size. For a given aptamer that was annotated by multiple UniProt identifiers, we used the first identifier62,63,64. GO biological process terms were ranked using Hypergeometric distribution with statistical correction as implemented in the R package, clusterProfiler65.

Next, we investigated biological interactions between proteins included in the set of 144 proteins. Starting with 144 proteins, we utilized the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins(STRING) interaction database using stringApp66 or Cytoscape67 and used an interaction score cutoff of 0.8, allowing 10 indirectly connected neighboring proteins to reconstruct a STRING network68. Applying these criteria, we found 154 proteins in the STRING database, with the largest network consisting of 55 proteins. We then used the largest network to perform enrichment analysis, to investigate functional consistency between networked subsets of proteins.

Clinical Models of Mortality We formulated three Clinical Models: a refit Comorbidity, refit Clinical, and refit Cohort-specific Clinical model. We based the Comorbidity model on the modified Comorbidity Index published by Liu et al.17. In the published index, comorbidities are scored on a point system as diabetes (1), myocardial infarction (1), cerebrovascular attack (2), peripheral arterial disease (2), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2), arrhythmia (2), malignancy (2), gastrointestinal bleeding (2) and heart failure(3). We did not include gastrointestinal bleeding in our model because it was not adjudicated in CRIC or PACE. We used atrial fibrillation instead of generalized arrhythmia. The Clinical model was based on the model published by Wagner et al.18, comprised of age, sex, designated race, diabetes, etiology of kidney failure, CVD, diabetes x CVD, smoking, and serum creatinine, hemoglobin, albumin, and calcium. Serum creatinine was missing in 98% of PACE participants at the second time point. We explored its contribution to risk prediction when integrated into a model comprised of variables listed above, refit to CRIC. The β for serum creatinine was non-significant (p > 0.7) for both incident and prevalent time periods. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) (95%CI) in a model with or without creatinine were: 0.724 (0.610, 0.829) vs 0.725 (0.613, 0.830), incident time period; 0.590 (0.470, 0.707) vs 0.590 (0.470, 0.706), prevalent time period. Due to its negligible contribution to the risk model in CRIC and high missingness in PACE, we excluded serum creatinine from the Clinical model. In the pooled cohort, we devised a Cohort Clinical Model as a benchmark comparison for protein models. We made a list of variables included in Comorbidity or Clinical Model, as well as variables associated with mortality at p < 0.05 in either cohort (smoking, DBP, BMI, PTH, LDL-C, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and phosphate) and other plausible factors (HDL-C, SBP, months since starting dialysis, vascular dialysis access) and allowed elastic net to choose predictive variables in the incident or prevalent periods. In order to make fair comparisons with the protein models that were developed in these cohorts, our Comorbidity and Clinical models were fit models to the derivation cohort (80% testing set in CRIC, or 80% testing set in pooled cohort), and tested AUCs in the 20% testing sets. The variables and coefficients are listed in Supplementary Data 15.

Multi-protein risk models

We developed multi-protein and hybrid clinical factor-protein risk models for the primary outcome, 5-year mortality, and compared their predictive performance to Comorbidity, Clinical and Cohort Clinical models. We built hybrid models by allowing all clinical factors in the three models to compete with all measured proteins. Risk models were trained in a random partition of 80% of the CRIC participants and tested in the remaining 20%. We then validated the model in the full PACE cohort for the corresponding incident or prevalent time period. In a companion analysis, we pooled CRIC and PACE and split the pooled cohort into 80%/20% for training and testing models. For the pooled analyses, we added an indicator variable to identify the origin cohort forcing it into the model in one instance and allowing it to compete with clinical variables and proteins in another. Our frontline technique for developing protein risk prediction models was elastic-net Cox regression which combines ridge (L2) and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (L1) penalties. The relative contributions of the two penalties are controlled by a mixing parameter α which we set to 0.5 for balance. The shrinkage (regularization) parameter λ which controls model complexity (the number of included proteins) was determined by 10-fold cross validation and the “1 standard error rule”. After the final selection of proteins, to reduce bias in estimated regression coefficients69, we refit the selected features for the elastic-net model in another Cox regression, as previously published70. We performed model fitting using the R package glmnet, and fit protein models in the 80% training sets and tested the models in the 20% testing sets. AUCs for risk models were compared using paired bootstrapped t-tests with one-sided p-values71, and p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Due to the small sample available in the testing sets, we assessed calibration in the training set using a model-based test that can accommodate survival endpoints in addition to continuous and binary outcomes72. We conducted stability analyses of our elastic net models to ensure that results were not overly dependent on the specific training / test set partition deployed. This process involved repeating the entire elastic-net procedure on five alternate random partitions into training and testing sets. Additionally, in the pooled cohort, to exclude factors with minimal contribution to the model, we performed stability analyses for the Cohort Clinical Model, the Protein model, and the Hybrid model, by applying Cox model elastic net to 50 different random splits of the original 80% training set, reserving the original 20% set to test model discrimination. The final version of each of these three models in the pooled cohort includes clinical or protein risk factors that were selected in ≥30 of 50 splits. Variables and coefficients for protein models are listed in Supplementary Data 16 and 17.

External validation

We validated in PACE those proteins that, in CRIC, were associated with mortality in full follow-up time at FDR < 0.05 in unadjusted analyses. We designated significant validation in PACE as FDR < 0.05 in the context of the number of proteins tested. Individual protein associations and multi-protein risk models were validated in the corresponding incident or prevalent time period in PACE, full cohort. We conducted statistical analyses using R, version 4.2.2 (RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA. URL http://www.rstudio.com/), with the packages of glmnet (version 4.1-8), survival (version 3.5-0), survivalROC (version 1.0.3.1), survcomp (version 1.48.0), tidyverse (version 1.3.2), magrittr (version 2.0.3), tableone (version 0.13.2), mice (version 3.15.0).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The CRIC data included in these analyses will be available to approved requestors in the future in the NIDDK Central Repository and at dbGaP. Prior to the availability of data in the repositories, requests can be made to the CRIC Study group by contacting the CRIC Scientific and Data Coordinating Center at cri-projmgmt@lists.upenn.edu. Appropriate regulatory and scientific approvals are required. The data are not publicly available due to individual-level informed consent restrictions. The CRIC Study group will typically respond to requests within 1 week, but the timeframe for providing data will vary depending on the timeline for completion of a Data Use Agreement between Penn and the receiving institution. If at the time of the data request, the data are available through a federal repository, the requestor will be referred to the appropriate repository to submit a data request. The PACE data included in these analyses are not publicly available due to individual-level informed consent restrictions. Requests for PACE data may be sent to Principal Investigator Rulan Parekh, MD, Rulan.Parekh@wchospital.ca or administrative assistant, Andrea.Verdugo@wchospital.ca. Requests for PACE data access will be addressed with 1–2 weeks and data access will require a data use agreement. Raw proteomics data generated for these analyses of CRIC and PACE participants are not deposited in a public repository due to individual-level informed consent restrictions in place for these cohorts. The results generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data files. A portion of the data reported here has been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

USRDS. End stage renal disease incidence, prevalence, patient characteristics and treatment modalities. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2022/end-stage-renal-disease/1-incidence-prevalence-patient-characteristics-and-treatment-modalities (2022).

USRDS. End stage renal disease. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2023 (2023).

Wachterman, M. W. et al. One-year mortality after dialysis initiation among older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 179, 987–990 (2019).

USRDS. End stage renal disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/usrds/prior-data-reports/2019 (2019).

Eknoyan, G. et al. Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 2010–2019 (2002).

Eckardt, K. U. et al. Safety and efficacy of vadadustat for anemia in patients undergoing dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1601–1612 (2021).

Investigators, E. T. et al. Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2482–2494 (2012).

USRDS. End stage renal disease. Mortality. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2023/end-stage-renal-disease/6-mortality#:~:text=Adjusted%20all%2Dcause%20mortality%20among,191.5%20per%201000%20person%2Dyears (2023).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Block, G., Humphreys, M. H. & Kopple, J. D. Reverse epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in maintenance dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 63, 793–808 (2003).

Fellstrom, B. C. et al. Rosuvastatin and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1395–1407 (2009).

Wanner, C. et al. Study I. Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 238–248 (2005).

Zannad, F. et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events in end-stage renal disease: results of a randomized trial of fosinopril and implications for future studies. Kidney Int. 70, 1318–1324 (2006).

Charytan, D. M. et al. Safety and cardiovascular efficacy of spironolactone in dialysis-dependent ESRD (SPin-D): a randomized, placebo-controlled, multiple dosage trial. Kidney Int. 95, 973–982 (2019).

Beddhu, S., Bruns, F. J., Saul, M., Seddon, P. & Zeidel, M. L. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am. J. Med. 108, 609–613 (2000).

Akbilgic, O. et al. Machine learning to identify dialysis patients at high death risk. Kidney Int. Rep. 4, 1219–1229 (2019).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40, 373–383 (1987).

Liu, J., Huang, Z., Gilbertson, D. T., Foley, R. N. & Collins, A. J. An improved comorbidity index for outcome analyses among dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 77, 141–151 (2010).

Wagner, M. et al. Predicting mortality in incident dialysis patients: an analysis of the United Kingdom Renal Registry. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 57, 894–902 (2011).

Shafi, T. et al. Association of residual urine output with mortality, quality of life, and inflammation in incident hemodialysis patients: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 56, 348–358 (2010).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kopple, J. D., Block, G. & Humphreys, M. H. A malnutrition-inflammation score is correlated with morbidity and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 38, 1251–1263 (2001).

Dubin, R. F. et al. Incident heart failure in chronic kidney disease: proteomics informs biology and risk stratification. Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae288 (2024).

Dubin, R. F. et al. Proteomics of CKD progression in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort. Nat. Commun. 14, 6340 (2023).

Helgason, H. et al. Evaluation of large-scale proteomics for prediction of cardiovascular events. JAMA 330, 725–735 (2023).

Yu, J. E. et al. Significance of chitinase-3-like protein 1 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 1–18 (2024).

Martin, A. I. et al. IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in inflammatory cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179469 (2021).

Higashi, Y., Gautam, S., Delafontaine, P. & Sukhanov, S. IGF-1 and cardiovascular disease. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 45, 6–16 (2019).

Oh, Y. The insulin-like growth factor system in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiology and therapeutic opportunities. Kidney Res. Clin. Pr. 31, 26–37 (2012).

Jung, I. H. et al. SVEP1 is a human coronary artery disease locus that promotes atherosclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abe0357 (2021).

Elenbaas, J. S. et al. SVEP1 is an endogenous ligand for the orphan receptor PEAR1. Nat. Commun. 14, 850 (2023).

Foulquier, S. et al. WNT signaling in cardiac and vascular disease. Pharm. Rev. 70, 68–141 (2018).

McDonald, K. et al. Tetranectin, a potential novel diagnostic biomarker of heart failure, is expressed within the myocardium and associates with cardiac fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 10, 7507 (2020).

Ho, J. E. et al. Protein biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the community. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.008108 (2018).

Steiger, S., Rossaint, J., Zarbock, A. & Anders, H. J. Secondary immunodeficiency related to kidney disease (SIDKD)-definition, unmet need, and mechanisms. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 33, 259–278 (2022).

Moore, K. J. & Freeman, M. W. Scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis: beyond lipid uptake. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1702–1711 (2006).

Detrano, R. et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1336–1345 (2008).

Carrasco-Zanini, J. et al. Proteomic signatures improve risk prediction for common and rare diseases. Nat. Med. 30, 2489–2498 (2024).

Zanetti, D. et al. Plasma proteomic signatures of a direct measure of insulin sensitivity in two population cohorts. Diabetologia 66, 1643–1654 (2023).

Du, S. et al. Plasma protein biomarkers of healthy dietary patterns: results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study and the Framingham Heart Study. J. Nutr. 153, 34–46 (2023).

Williams, S. A. et al. A proteomic surrogate for cardiovascular outcomes that is sensitive to multiple mechanisms of change in risk. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabj9625 (2022).

Therapeutic Target Database. (2025). https://db.idrblab.net/ttd/ Access date April 2025.

Su, M. et al. Endothelial IGFBP6 suppresses vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 4, 145–162 (2025).

Pemberton, C. J. et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) measurement in the detection of significant CAD in acute chest pain patients triaged using the No Objective Testing (NOT) rule. Eur. Heart J. 45, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae666.1572 (2024).

Hoeflich, A., David, R. & Hjortebjerg, R. Current IGFBP-related biomarker research in cardiovascular disease—we need more structural and functional information in clinical studies. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 388 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Neuregulin-1, a potential therapeutic target for cardiac repair. Front. Pharm. 13, 945206 (2022).

Cools, J. M. T. et al. Small-molecule-induced ERBB4 activation to treat heart failure. Nat. Commun. 16, 576 (2025).

Ren, Y. et al. Evaluation of a large-scale aptamer proteomics platform among patients with kidney failure on dialysis. PLoS ONE 18, e0293945 (2023).

Goldstein, B. A. et al. Designing an implementable clinical prediction model for near-term mortality and long-term survival in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 84, 73–82 (2024).

Feldman, H. I. et al. The chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study: design and methods. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, S148–153 (2003).

Lash, J. P. et al. Chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) Study: baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4, 1302–1311 (2009).

Parekh, R. S. et al. Rationale and design for the predictors of arrhythmic and cardiovascular risk in end stage renal disease (PACE) study. BMC Nephrol. 16, 63 (2015).

Brody, E. N., Gold, L., Lawn, R. M., Walker, J. J. & Zichi, D. High-content affinity-based proteomics: unlocking protein biomarker discovery. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 10, 1013–1022 (2010).

Ganz, P. et al. Development and validation of a protein-based risk score for cardiovascular outcomes among patients with stable coronary heart disease. JAMA 315, 2532–2541 (2016).

Gold, L. et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS ONE 5, e15004 (2010).

Rohloff, J. C. et al. Nucleic acid ligands with protein-like side chains: modified aptamers and their use as diagnostic and therapeutic agents. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 3, e201 (2014).

Sun, B. B. et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 558, 73–79 (2018).

Williams, S. A. et al. Plasma protein patterns as comprehensive indicators of health. Nat. Med. 25, 1851–1857 (2019).

Candia, J. et al. Assessment of variability in the SOMAscan assay. Sci. Rep. 7, 14248 (2017).

Niewczas, M. A. et al. A signature of circulating inflammatory proteins and development of end-stage renal disease in diabetes. Nat. Med. 25, 805–813 (2019).

USRDS. 2024 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States (National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2024).

Harrell, F. E. Jr., Califf, R. M., Pryor, D. B., Lee, K. L. & Rosati, R. A. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA 247, 2543–2546 (1982).

Hochberg, Y. & Benjamini, Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 9, 811–818 (1990).

Ferrannini, E. et al. Mechanisms of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition: insights from large-scale proteomics. Diabetes Care 43, 2183–2189 (2020).

Williams, S. A. et al. Improving assessment of drug safety through proteomics: early detection and mechanistic characterization of the unforeseen harmful effects of torcetrapib. Circulation 137, 999–1010 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Impact of kidney function on the blood proteome and on protein cardiovascular risk biomarkers in patients with stable coronary heart disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e016463 (2020).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Doncheva, N. T., Morris, J. H., Gorodkin, J. & Jensen, L. J. Cytoscape StringApp: network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J. Proteome Res. 18, 623–632 (2019).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

STRING. https://string-db.org (2025). Access date July 2025.

Meinshausen, N. Relaxed lasso. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 52, 374–393 (2007).

Deo, R. et al. Proteomic cardiovascular risk assessment in chronic kidney disease. Eur. Heart J. 44, 2095–2110 (2023).

Konietschke, F. & Pauly, M. Bootstrapping and permuting paired t-test type statistics. Stat. Comput. 24, 283–296 (2014).

Crowson, C. S., Atkinson, E. J. & Therneau, T. M. Assessing calibration of prognostic risk scores. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 25, 1692–1706 (2016).

Kong, P. et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 131 (2022).

McDowell, K. et al. Incremental prognostic value of biomarkers in PARADIGM-HF. Eur. J. Heart Fail 25, 1406–1414 (2023).

Guadall, A. et al. Fibulin-5 is up-regulated by hypoxia in endothelial cells through a hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1alpha)-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7093–7103 (2011).

Vergeer, M. et al. Genetic variation at the phospholipid transfer protein locus affects its activity and high-density lipoprotein size and is a novel marker of cardiovascular disease susceptibility. Circulation 122, 470–477 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (IGFBP7) links senescence to heart failure. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 1, 1195–1214 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Aptamer proteomics for biomarker discovery in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 146, 1411–1414 (2022).

Daher, R. et al. Heterozygous mutations in BMP6 pro-peptide lead to inappropriate hepcidin synthesis and moderate iron overload in humans. Gastroenterology 150, 672–683.e674 (2016).

Birkner, K. et al. Neuronal ICAM-5 plays a neuroprotective role in progressive neurodegeneration. Front. Neurol. 10, 205 (2019).

Kiechl, S. et al. Osteoprotegerin is a risk factor for progressive atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 109, 2175–2180 (2004).

Ueland, T. et al. Dysregulated osteoprotegerin/RANK ligand/RANK axis in clinical and experimental heart failure. Circulation 111, 2461–2468 (2005).

Marques, G. L. et al. Osteoprotegerin is a marker of cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5. Sci. Rep. 11, 2473 (2021).

Liu, D. et al. Myocardial recovery in recent onset dilated cardiomyopathy: role of CDCP1 and cardiac fibrosis. Circ. Res. 133, 810–825 (2023).

Chen, K. et al. FGL1-LAG3 axis impairs IL-10-Producing regulatory T cells associated with Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. Heliyon 9, e20806 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Fibrinogen-like protein 1 is a novel biomarker for predicting disease activity and prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Immunol. 11, 579228 (2020).

Lin, M. et al. Targeting fibrinogen-like protein 1 enhances immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 133, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI164528 (2023).

Qian, W., Zhao, M., Wang, R. & Li, H. Fibrinogen-like protein 1 (FGL1): the next immune checkpoint target. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 147 (2021).

Judge, S. M. et al. MEF2c-dependent downregulation of myocilin mediates cancer-induced muscle wasting and associates with cachexia in patients with cancer. Cancer Res. 80, 1861–1874 (2020).

Baxter, R. C. Endocrine and cellular physiology and pathology of the insulin-like growth factor acid-labile subunit. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-024-00970-4 (2024).

Meyer, R. C., Giddens, M. M., Coleman, B. M. & Hall, R. A. The protective role of prosaposin and its receptors in the nervous system. Brain Res. 1585, 1–12 (2014).

Hamid, S., Rhaleb, I. A., Kassem, K. M. & Rhaleb, N. E. Role of kinins in hypertension and heart failure. Pharmaceuticals 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13110347 (2020).

Forrest, G. L., Gonzalez, B., Tseng, W., Li, X. & Mann, J. Human carbonyl reductase overexpression in the heart advances the development of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 60, 5158–5164 (2000).

Loffredo, F. S. et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 153, 828–839 (2013).

Olson, K. A. et al. Association of growth differentiation factor 11/8, putative anti-ageing factor, with cardiovascular outcomes and overall mortality in humans: analysis of the Heart and Soul and HUNT3 cohorts. Eur. Heart J. 36, 3426–3434 (2015).

Walker, R. G. et al. Biochemistry and biology of GDF11 and myostatin: similarities, differences, and questions for future investigation. Circ. Res. 118, 1125–1141; discussion 1142 (2016).

Bataille, S., Chauveau, P., Fouque, D., Aparicio, M. & Koppe, L. Myostatin and muscle atrophy during chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 36, 1986–1993 (2021).

Li, Y., Wright, G. L. & Peterson, J. M. C1q/TNF-related protein 3 (CTRP3) function and regulation. Compr. Physiol. 7, 863–878 (2017).

Acknowledgements