Abstract

In-sensor computing holds great promise for ultrafast and energy-efficient machine vision. However, the development of a versatile in-sensor computing system that can integrate image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions remains a challenge, primarily due to the scarcity of photosensors that can offer both dynamic photoresponse and programmable photoresponsivity. Here, we successfully integrate these multi-functions into a ferroelectric photosensor-based array. The key enabler is the ferroelectric photosensor operating via the bulk photovoltaic effect, which exhibits above-bandgap, dynamically responding, and electrically switchable photovoltages. By using the dynamic photovoltage response, the array is capable of memorizing and pre-processing images, with the ability to adjust the memory and pre-processing effects by ferroelectric polarization. On the other hand, the electrically switchable photovoltages, featuring multi-level switchability and retrievability, enable the array to perform in-sensor high-level computing, achieving 100% accuracy in a 4-class image recognition task (noise level ≤ 10%). Notably, the high precision and reliability of photovoltage-based image memorization and processing greatly benefit from the high photovoltage produced by the ferroelectric photosensor — a distinct advantage for this application. This study lays the foundation for developing versatile in-sensor computing systems that could be utilized across a wide range of machine vision scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the era of artificial intelligence, machine vision is playing a vital role in various applications such as facial recognition, autonomous driving, and automated manufacturing1,2. Conventional machine vision systems capture and process visual images by using physically separated sensing, memory, and processing units. Massive data shuffling between these units, however, often causes significant latency and energy consumption2. To tackle this issue, a promising solution known as in-sensor computing has emerged and attracted tremendous attention3,4. In this technique, visual information is directly processed within photosensors, relieving the burden of data shuffling and hence resulting in boosted speed and energy efficiency.

So far a variety of in-sensor computing systems have been developed, which can mainly be classified into two types according to their functions. The first type are in-sensor pre-processing systems capable of implementing image memorization and low-level processing, e.g., noise reduction, contrast enhancement, and visual adaptation5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. These systems can enhance the quality of sensory data and help improve the efficiency of further processing. On the other hand, the second type are in-sensor high-level computing systems which can directly perform high-level image processing, e.g., recognition and autoencoding3,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. These systems enable simultaneous sensing and interpretation of visual information with exceptionally low latency and energy consumption. To handle diverse machine vision tasks and capitalize on the advantages of both types of systems, it is essential to develop a versatile in-sensor computing system that can integrate image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). However, to our knowledge, such a system has not yet been realized. It is worth noting that despite recent advances in neuromorphic vision systems with multifunctional capabilities15,17,30,31,32, these systems consistently utilized a near-sensor computing architecture (Supplementary Fig. 2), where a front-end module performs image sensing/pre-processing while a back-end module implements high-level computing. This architectural distinction clearly differentiates them from the proposed versatile in-sensor computing system.

a Schematics of photosensors exhibiting only dynamic photoresponse (DP) or programmable photoresponsivity (PP), and multifunctional photosensors exhibiting both the DP and PP. The multifunctional photosensors are used to construct a versatile in-sensor computing system that can integrate image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions. b Schematics illustrating the operation mechanism of a photovoltage-based multifunctional photosensor. This device operates by using its photo-generated charges to charge up itself and an external capacitor. The internal field (Eint) within the device provides the photovoltaic driving force. Tuning the Eint results in the PP. Additionally, the photo-generated charges induce an electric field Eph that can in turn modify the photovoltaic driving force, leading to the DP. till refers to illumination time.

To construct a versatile in-sensor computing system, multifunctional photosensors with dynamic photoresponse and programmable photoresponsivity are demanded. The dynamic photoresponse allows for image memorization and low-level processing (top panel of Fig. 1a), while the programmable photoresponsivity can serve as synaptic weight for high-level computing, which involves multiplying the photoresonsivity by an input light intensity to produce an electrical output (bottom panel of Fig. 1a). However, integrating these multi-functionalities into a single device is challenging. This is because the dynamic photoresponse typically results in an illumination history dependence, whereas the programmable photoresponsivity for high-level computing should either be independent of the illumination history or retrievable upon clearing the illumination history.

Photovoltage-based photosensors emerge as a well-suited candidate for achieving the desired multi-functionalities. Such a device operates by using its photo-generated charges to charge up itself and an external capacitor (Fig. 1b). The dynamic charging/discharging process naturally results in gradual photovoltage rise/decay with an RC time constant determined by the photosensor and the capacitor. This characteristic enables the implementation of image memorization and low-level processing. In addition, the internal field in the photosensor, serving as the photovoltaic driving force, can be tuned to achieve programmable photoresponsivity. Importantly, the photo-generated charges are stored in the electrodes of the photosensor and the capacitor, which can be easily removed through short-circuiting. This allows for a quick retrieval of the programmed photoresponsivity without the need for re-programming, significantly reducing the operational complexity in high-level computing. Therefore, the photovoltage-based photosensors hold great promise to enable the integration of image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions. Also noteworthy is that these devices require no current-voltage conversion, which can help reduce hardware overhead and energy consumption at the system level.

To realize such a photovoltage-based multifunctional photosensor, ferroelectric photosensor (FE-PS) is resorted to for its distinctive features as follows. First, unlike conventional photosensors whose photovoltages are restricted by materials’ bandgaps, the FE-PS based on the bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect can exhibit an above-bandgap photovoltage33,34, even reaching several kilovolts35,36. The high photovoltage is advantageous for ensuring the precision and reliability of photovoltage-based image memorization and processing. In addition, the FE-PS typically exhibits a low leakage current34, which can suppress the current backflow during the charging process and hence enable the output photovoltage to reach high. The low leakage current also contributes to the dynamic behavior of the photovoltage response as it increases the RC time constant, facilitating the implementation of image memorization and low-level processing. Besides, the photovoltage and associated photoresponsivity of the FE-PS can be tuned by ferroelectric polarization37,38. This enables the implementation of high-level image processing. Despite these merits, the FE-PS has yet to be effectively harnessed for constructing versatile in-sensor computing systems.

Here, we develop a BPV effect-based FE-PS exhibiting above-bandgap, dynamically responding, and electrically switchable photovoltages, and demonstrate a proof-of-concept for the integration of image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions into a FE-PS-based array. By using the dynamic charging/discharging process, the FE-PS shows gradual photovoltage rise/decay, mimicking optoelectronic synaptic behavior. Based on these characteristics, the FE-PS-based array demonstrates image memorization and pre-processing (e.g., visual adaptation) functions, with the ability to adjust the memory and pre-processing effects by ferroelectric polarization. On the other hand, the FE-PS exhibits a giant switchable photovoltage (~30 V) for high-level computing, along with multi-level switchability and retrievability. Using the photovoltage-defined photoresponsivity to map the synaptic weight, the FE-PS-based array acts as an in-sensor artificial neural network (ANN), which can be trained to realize high-accuracy image recognition. The FE-PS-based array thus represents a versatile in-sensor computing system which is promising for use in various machine vision scenarios.

Results

Basic photovoltaic properties of FE-PS

Figure 2a shows a schematic of the device structure of the proposed FE-PS, consisting of a piece of (Pb0.97La0.03)(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 (PLZT) ceramic and Au interdigital electrodes. The PLZT ceramic (thickness: 0.3 mm) exhibits pure perovskite phase (Supplementary Fig. 3), dense microstructure (Supplementary Fig. 4), and robust ferroelectricity with a remanent polarization as high as ~45 μC/cm2 (Supplementary Fig. 5), confirming the high quality of the PLZT ceramic. The photography and geometric parameters of the interdigital electrodes are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6.

a Schematics illustrating the device structure of the FE-PS with interdigital electrodes, and the experimental setup for the photovoltage measurement. b Temporal photovoltage responses of the FE-PS to the same light pulse (intensity: 98 mW/cm2; width: 2.5 s) when Cex = 0, 100 pF, 680 pF, 1.5 nF, and 10 nF are used. Schematics illustrating (c) the gradual photovoltage rise during illumination and d the gradual photovoltage decay after illumination. e Photovoltaic current-voltage (I–V) characteristics of the FE-PS in the 200 V- and −200 V-poled states (light intensity: 78 mW/cm2), along with its dark I–V characteristics. In (e), Cex = 0 is used. Insets show the schematics of the photovoltaic effects in the FE-PS in different polarization states. f Comparison of switchable photovoltages and open-circuit voltages between our FE-PS, typical photovoltaic devices used for in-sensor high-level computing (solid symbols), and typical BPV-based devices (hollow symbols). “FE-based devices (BPV)” refers to previously reported ferroelectric-based devices operating via the BPV effect, while “FE-based devices (non-BPV)” denotes those functioning through other photovoltaic mechanisms. “FETs” refer to the field-effect transistors. “Ionic devices” refer to the devices whose switchable photovoltaic behavior is induced by the ion migration. The data in (f) are extracted from refs. 3,22,24,25,26,27,28,33,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,63.

The PLZT ceramic-based FE-PS is first poled by 200 V DC voltage for 5 min (note: hereafter unless otherwise specified, the poling time is always 5 min). Then, it is exposed to 365 nm ultraviolet (UV) illumination to generate charges to charge up itself and a capacitor Cex (Fig. 2a). The voltage across the FE-PS (or the capacitor) represents the output photovoltage, i.e., Vph. Figure 2b shows the temporal photovoltage responses of the FE-PS to the same light pulse (intensity: 98 mW/cm2; width: 2.5 s) when different Cexs are used. Note that Cex = 0 refers to the case where the FE-PS is directly connected to the source meter. In this case, only the capacitance of the FE-PS works. As shown in Fig. 2b, the output Vph increases gradually during illumination, and then it decays gradually after illumination. This gradual variation in Vph is a natural consequence of the dynamic charging/discharging process. In brief, when illuminating the FE-PS (Fig. 2c), its photovoltaic effect generates charges to charge up itself and the Cex, thereby increasing the Vph. The Vph is in turn applied to the FE-PS, reducing the photovoltaic driving force. The overall charging current therefore gradually decreases as the Vph increases, slowing down the charging process and causing a gradual Vph increase. When the illumination is withdrawn (Fig. 2d), the FE-PS and Cex discharge via leakage currents, reducing the Vph. The reduction in Vph in turn reduces the leakage currents. Consequently, the discharging process slows down over time, leading to a gradual Vph decay. Besides, Fig. 2b further shows that the rate of the Vph rise/decay decreases with increasing Cex. This confirms that the dynamic variation in Vph results from the charging/discharging process with an RC time constant influenced by the Cex. Such dynamic photovoltage response endows the FE-PS with optoelectronic synaptic behavior, and also allows it to implement image memorization and low-level processing (to be demonstrated later).

Another striking observation from Fig. 2b is that the output Vph can reach a remarkably high level. For example, when Cex = 0, the Vph right after the light pulse is 5.4 V, already exceeding the bandgap of PLZT (i.e., 3.35 eV)39. Moreover, as the illumination time is elongated, the Vph can further increase and eventually saturates at an open-circuit voltage (VOC) of ~15 V (see Supplementary Fig. 7). Such high photovoltages can be observed across different devices (Supplementary Fig. 8), evidencing the ubiquity of above-bandgap photovoltages in our FE-PSs. The high photovoltage can benefit the precision and reliability of photovoltage-based image memorization and processing, providing a distinct application-specific advantage.

The origin for the above-bandgap photovoltage is primarily attributed to a well-established photovoltaic mechanism known as the BPV effect40,41,42,43,44. The BPV effect occurs in non-centrosymmetric materials like ferroelectrics, where crystal asymmetry induces separation of photo-generated charge carriers. This is unlike the charge separation caused by an interfacial built-in field in conventional photovoltaic devices. As a result, the BPV effect allows for an exceptionally high photovoltage which is not limited by the material’s bandgap. More evidence for the BPV effect in our FE-PS is presented in Supplementary Figs. 9–11 and Note 1. Another factor contributing to the high photovoltage of our FE-PS is its low leakage current. As shown in Fig. 2e, the leakage current of the FE-PS is only ~30 pA @ 15 V. Such a low leakage current indicates that the current backflow through the FE-PS is very small during the charging process, which is beneficial for preserving a high photovoltage. Additionally, the low leakage current of the FE-PS also suppresses the discharge, contributing to the gradual photovoltage decay after removing illumination.

In addition to high photovoltage and dynamic photovoltage response, our FE-PS also exhibits switchable photovoltages arising from polarization modulation of photovoltaic behavior. This feature is demonstrated by measuring the photovoltaic current-voltage (I–V) characteristics of the FE-PS after poling with different polarities, where Cex = 0 is used. As shown in Fig. 2e, the FE-PS in the 200 V-poled state exhibits a VOC of 15.2 V and a short-circuit current (ISC) of −1.1 nA. After the −200 V poling, the VOC and ISC are switched to −15.2 V and 1.1 nA, respectively, which are just opposite to those in the 200 V-poled state. Such switchable photovoltaic behavior is well associated with the poling-induced polarization switching (Supplementary Fig. 12). The polarization-controlled switchable photovoltaic behavior can be used for high-level image processing. However, most previous studies utilized the switchable photocurrent for computing22,23,24,25,26, where the computed results still required conversion into voltage signals before being sent to next neuronal layers or CMOS-based peripheral circuits for further processing. To streamline this process, we directly use the switchable photovoltage for high-level image processing (to be demonstrated later). Note that the switchable photovoltage of our FE-PS is as high as ~30 V (from 15.2 V to −15.2 V or vice versa), far surpassing those of previously reported photovoltaic devices used for in-sensor high-level computing (solid symbols in Fig. 2f). Because the switchable photovoltage determines the range and precision of programmed weights, our FE-PS thus offers a clear advantage for photovoltage-based computing. The high switchable photovoltage of our FE-PS is attributed to the BPV effect, which not only generates a high photovoltage but also allows it to be switchable. In contrast, earlier photovoltaic devices3,24,25,26,27,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, including ferroelectric-based ones22,28,56,57,58,59, mainly relied on interfacial photovoltaic effects, resulting in a limited VOC, let alone the switchable photovoltage. On the other hand, although prior BPV-based devices exhibited high switchable photovoltages (hollow symbols in Fig. 2f)33,60,61,62,63, they have not been applied to in-sensor high-level computing. Our FE-PS effectively bridges this gap by harnessing the high switchable photovoltage generated by the BPV effect for in-sensor high-level computing.

The above results have demonstrated that our FE-PS exhibits high and electrically switchable photovoltage as well as dynamic photovoltage response. Then, we will demonstrate that the dynamic photovoltage response allows for image memorization and low-level processing, while the switchable photovoltage enables high-level computing. The combination of these features qualifies our FE-PS as an all-in-one multifunctional photosensor.

Image memorization and low-level processing based on dynamic photovoltage response of FE-PS

Conventional photosensors can only sense images, requiring additional memory and processing units to store and process images. This limited function is mainly due to that the conventional photosensors respond instantly to light signals. In contrast, our FE-PS exhibits dynamic photovoltage response. This characteristic enables the FE-PS to integrate image memorization and in situ pre-processing functions. Prior to demonstrating these functions, we first investigate the optoelectronic synaptic behavior of the FE-PS, which is a prerequisite for these functions. Figure 3a shows the photovoltage evolution of the FE-PS in response to a single light pulse with 98 mW/cm2 intensity and 2.5 s width, where Cex = 100 pF is used. The output Vph rises to a peak during the light pulse, followed by a decay after the light pulse, which well mimics the excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) of a biological synapse64,65.

a EPSC behavior of the FE-PS in response to a light pulse. b PPF behavior of the FE-PS stimulated by a pair of light pulses. c PPF index as a function of the interval between light pulses (Δt). Each PPF index is averaged from 5 independent tests, with the error bar indicating the standard deviation. Inset shows a schematic of the PPF effect for illustrating how the PPF index is defined. Temporal photovoltage responses of the FE-PS under repeated light pulses with different d amplitudes (Ilight), e widths (tw), and f numbers (Npulse). g Ilight-dependent temporal photovoltage responses of the FE-PS in different polarization states. Insets show the 3 different states: States I, II, and III, which are obtained by applying 200 V, −25 V, and −50 V sequentially. In (a–g), Cex = 100 pF is used.

Besides the EPSC, another important short-term synaptic function called paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) can also be emulated by the FE-PS. The PPF manifests itself as a phenomenon that when two successive pulses are applied to a presynaptic neuron, the second EPSC is higher than the first one. As shown in Fig. 3b, the photovoltage spike induced by the second light pulse is apparently higher than that induced by the first light pulse, well resembling the PPF behavior. The ratio between the height of the second photovoltage spike (A2) and that of the first one (A1) is defined as the PPF index. As displayed in Fig. 3c, the PPF index gradually increases as the interval between the two light pulses (Δt) decreases. Note that a shorter Δt results in less time for discharge. This means that more charges are retained in the FE-PS and Cex after the interval, thereby allowing them to be charged to higher voltages during the second light pulse. Figure 3c further reveals that the dependence of the PPF index on Δt can be fitted with a double-exponential function66:

where Ci and τi are the initial facilitation magnitude and characteristic relaxation time, respectively, and i = 1 (2) corresponds the rapid (slow) relaxation process. The fitting gives τ1 = 5 s and τ2 = 55 s. It is noted that τ2 is one order of magnitude larger than τ1, agreeing well with the rule observed in biological synapses67.

Applying repetitive pulse stimulation to a biological synapse can cause its short-term plasticity (STP) to transform into a long-term plasticity (LTP). This capability is essential for memory and learning functions. To imitate the STP-to-LTP transition, repeated light pulses with different amplitudes, widths, and numbers are applied to the FE-PS, and its temporal photovoltage responses are recorded. As shown in Fig. 3d–f, the photovoltage spike increases in height as the pulse amplitude, width, or number increases, which is well attributed to the increased production of photo-generated charges in the FE-PS. Additionally, the photovoltage retained after the pulse stimulation also rises to a higher level with increasing pulse amplitude, width, or number. These results demonstrate the realization of the STP-to-LTP transition in the FE-PS.

Moreover, the optoelectronic synaptic behavior of the FE-PS can be modulated by the polarization. As shown in the inset of Fig. 3g, the FE-PS is first set in a high-polarization state (State I) by a 200 V poling. Then, the polarization is reduced in magnitude (without changing its direction) by sequentially applying −25 V and −50 V poling, resulting in intermediate- and low-polarization states (States II and III, respectively) (see the insets of Fig. 3g). In each of these states, the photovoltage responses of the FE-PS to repeated light pulses are measured. As shown in Fig. 3g, the photovoltage spike decreases in magnitude with reducing polarization, despite the application of the same light pulses. This originates from the fact that the photovoltaic behavior of the FE-PS is controlled by the polarization. The polarization-modulated synaptic plasticity is a key advantage of our FE-PS over other optoelectronic synaptic devices5,14,68,69,70.

As demonstrated above, our FE-PS with dynamic photovoltage response vividly emulates optoelectronic synaptic behavior. Moreover, the synaptic plasticity can be tuned by the polarization. These device characteristics enable the polarization-tunable image memorization and low-level processing. To demonstrate this, we experimentally construct a 3 × 3 FE-PS-based array (as schematically illustrated in Fig. 4a), and use it to sense and memorize a letter “T” (3 × 3 pixels; pixel value: 0 or 1). Each FE-PS in the array is connected to a Cex of 100 pF in parallel, and all these FE-PSs are pre-poled into the same state, i.e., State I, II, or III. The constructed array exhibits a minor pixel-to-pixel variation of ~5% (Supplementary Fig. 13). Then, the letter “T” is projected onto the array, where each FE-PS is exposed to a light pulse train (light intensity: 98 mW/cm2; pulse width: 2.5 s; pulse number: 10) if the pixel value is 1 or left in dark if the pixel value is 0. The output photovoltages of all the FE-PSs are recorded, constituting an output image.

a Schematic diagram of a 3 × 3 FE-PS-based array for memorizing a 3 × 3 image of a letter “T”. b Output images constituted by the output photovoltages of the 9 FE-PSs in States I (left column), II (middle column), and III (right column). The upper and lower rows show the output images obtained immediately and 30 s after the image presentation, respectively. c Schematic diagram of a FE-PS-based array for pre-processing images, which is connected to an ANN for subsequent recognition. d Typical original image before pre-processing (4th column), output images after different pulse numbers (Npulse) used for pre-processing when all the FE-PSs in the array are in the same State I (1st to 3rd columns), and output images at Npulse = 6 when all the FE-PSs are in State I, II, and III (5th to 7th columns). e Comparison of recognition accuracies between the original images and the pre-processed images after different Npulse. f Comparison of recognition accuracies between the original images and the pre-processed images by using the FE-PSs in different states.

As shown in the left top of Fig. 4b, when all the FE-PSs are in State I (i.e., the high-polarization state), an output image displaying a clear “T” is produced immediately after the light stimuli. As time progresses, the “T” becomes faded (Supplementary Fig. 14). Nevertheless, even after a prolonged period (e.g., 30 s, as depicted in the left bottom of Fig. 4b), the “T” still remains distinguishable, demonstrating an image memory effect for the FE-PSs in State I. Moreover, this image memory effect can be tuned by the polarization, as evidenced by the image intensity variation from the left to right columns in Fig. 4b. This capability allows better mimicry of human visual memory, which is highly tunable by factors like personal interest, mood, and attention71,72.

Besides image memorization, low-level image processing can also be demonstrated with the FE-PS-based array. One such demonstration involves visual adaptation, which refers to the adaptive imaging of objects under different levels of illumination18,47,49,73,74. In a human visual system, the visual adaptation relies on the adaptive modulation of the sensitivity of photoreceptors in the retina. For our FE-PS, the visual adaptation is enabled by its light intensity-dependent photovoltage rising behavior, as shown in Fig. 3d. Supplementary Fig. 15 further shows that the ratio between the photovoltages at the high and low light intensities (148 and 16 mW/cm2, respectively) is smaller than the input light intensity ratio, indicating that the FE-PS is relatively more (less) responsive to weaker (stronger) light stimuli. Moreover, the photovoltage ratio decreases with the number of light pulses, meaning that the difference in photovoltage responses under weak- and strong-light conditions can be narrowed as more light stimuli are applied. These results demonstrate the visual adaptation capability of the FE-PS, which can be attributed to the dynamic modulation of the charging process by photo-generated charges. Specifically, when applying a stronger illumination to the FE-PS, more photo-generated charges are produced for charging, resulting in a higher output Vph. However, the gain in Vph is under-proportional to the light intensity because the Vph can in turn hinder the charging process. This effect is also the reason for the gradual rise of photovoltage under illumination, as explained previously.

The FE-PSs with visual adaptation capability can be used to build an in-sensor image pre-processing system capable of improving the accuracy of subsequent recognition. To demonstrate this, a FE-PS-based array for image pre-processing, integrated with an ANN for subsequent recognition, is simulated, as schematically shown in Fig. 4c. The original images before pre-processing are modified handwritten digit images (28 × 28 pixels) from the Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (MNIST) dataset (see Methods). The foreground pixels of these images are assigned random values to represent the non-uniform illumination which is ubiquitous in real-world scenarios, while the background pixels are set at 0. These images are sensed and pre-processed by a 28 × 28 FE-PS-based array. Each FE-PS in the array is connected to a Cex of 100 pF in parallel, and all these FE-PSs are pre-poled into the same state, i.e., State I, II, or III. During image presentation, each FE-PS is stimulated by a light pulse train (pulse number Npulse is a variable) with light intensity defined by the image pixel value (see Methods). The photovoltage responses of all the FE-PSs are assumed to obey the behavior shown in Fig. 3g. The output photovoltage is further converted to a binary value of 1 if it exceeds 3 V or 0 otherwise. This binarization operation can be executed using a voltage comparator, which inevitably introduces additional hardware overhead. The binarized outputs of all the FE-PSs constitute an output image. Figure 4d (1st to 4th columns) shows the original image and output images after different Npulses when all the FE-PSs in the array are in State I. It is seen that the feature of the digit “2” becomes more distinct with increasing Npulse. This phenomenon is well attributed to the visual adaptation effect of the FE-PS. Specifically, the photovoltage response under weak light increases and becomes relatively closer to that under strong light as Npulse increases. Consequently, more foreground pixels of the output image become 1 as Npulse increases, gradually highlighting the feature of the digit. The pre-processed images are then sent to a purely software-based 784 × 10 ANN for recognition. As shown in Fig. 4e, the recognition accuracy increases as the Npulse used for adaptation increases, consistent with the enhancement in the clarity of the pre-processed images (Fig. 4d). Notably, the recognition accuracy after the 6-pulse adaptation reaches ~90%, which is ~5% higher than that without pre-processing. These results demonstrate that the in-sensor pre-processing system based on FE-PSs with visual adaptation capability can improve the image recognition accuracy.

Besides, it is shown in Fig. 3g that the visual adaptation behavior of the FE-PS strongly depends on its polarization state. Consequently, the clarity of the pre-processed images and the recognition accuracy can be significantly influenced by the polarization state, as demonstrated in Fig. 4d (4th to 7th columns) and Fig. 4f. Such tunable visual adaptation behavior is conducive for visual perception in complex environments18.

High-level image processing based on switchable photovoltage of FE-PS

Besides image memorization and low-level processing, our FE-PS also enables high-level image processing based on its switchable photovoltage. As already shown in Fig. 2e, the FE-PS exhibits switchable bi-state photovoltages. In fact, more photovoltage states can be achieved by applying appropriate poling voltages. To demonstrate this, the FE-PS is pre-poled with −200 V (200 V) and then poled with positive (negative) voltages with amplitudes varying from 25 V to 200 V (−25 V to −200 V). After each poling procedure, the photovoltaic I–V characteristics of the FE-PS with Cex = 0 are measured.

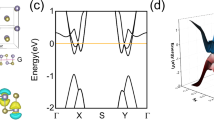

It is seen from Fig. 5a that with the increase of positive poling voltage, the I–V curve shifts gradually from the second quadrant to the fourth quadrant. Conversely, the direction of the I–V curve shift is reversed by applying negative poling with increasing voltages (Fig. 5b). Based on these I–V curves, multi-level photovoltages are extracted and plotted against poling voltages in Fig. 5c. A clear hysteresis loop is observed, suggesting that the switchable multi-level photovoltages are associated with the polarization states set by the poling voltages. Notably, the multi-level photovoltage switching enables programmable photoresponsivity when the photoresponsivity is defined as a linear function of an output photovoltage divided by an input light intensity. This programmable photoresponsivity can map synaptic weight in an ANN, thus achieving in-sensor high-level computing.

Photovoltaic I–V characteristics of the FE-PS after applying amplitude-increasing a positive and b negative poling voltages (light intensity: 78 mW/cm2). In (a, b), the device is pre-poled with −200 V and 200 V, respectively. c Hysteretic evolution of VOC with poling voltage, which is extracted from (a, b). d Multi-cycle photovoltage measurements for the FE-PS in different states (light intensity: 78 mW/cm2). Before each measurement cycle, the FE-PS is short-circuited. e Relationships between output photovoltage and input light intensity at different illumination times (till). f Temporal photovoltage responses of the FE-PS in 16 different states (light intensity: 54 mW/cm2), along with the well-separated photoresponsivities (RPV) corresponding to these states (shown in the inset). In (a–d), Cex = 0 is used, while in (e, f), Cex = 2200 pF is used.

However, as already shown in Fig. 3, the photovoltage is dependent on illumination history. This means that even when the FE-PS is programmed into a specific polarization state, its photovoltage and associated photoresponsivity can be altered each time the illumination is applied. This variability is unfavorable for the high-level computing, because the high-level computing requires the photoresponsivity, once programmed, to remain unchanged across different computing events. This issue can be easily addressed by short-circuiting the FE-PS prior to each computing event. As shown in Fig. 5d, the temporal photovoltage responses in different polarization states can be well reproduced once the device is short-circuited before each cycle. This indicates that the programmed photoresponsivity of the FE-PS can be successfully retrieved through the short-circuiting. The reason for this success is that the short-circuiting only removes the accumulated charges without changing the polarization state and its associated photoresponsivity. Note that for previous photocurrent-based photodetectors exhibiting an illumination history dependence, re-programming methods like electrical reset were often employed to retrieve the photoresponsivity17,18,19,75. Compared with these re-programming methods, the short-circuiting in our FE-PS is much simpler and more energy-efficient.

Besides the illumination history dependence of photovoltage, another challenge for high-level computing is the sublinear variation of photovoltage with light intensity (Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). In the high-level computing, multiplication manifests itself as multiplying a programmed photoresponsivity by an input light intensity to generate a photovoltage. For accurate multiplication, the photoresponsivity should not change with the light intensity, requiring a linear photovoltage-light intensity (Vph-Ilight) relationship. Fortunately, a quasi-linearity can be achieved by selecting an appropriate time period for reading the photovoltage. For example, quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationships (R2 > 0.99) are observed across illumination times (till) from 12.3 s to 24.6 s for the FE-PS connected to a Cex of 2200 pF (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Figs. 16, 17). We hereafter use the Vph-Ilight relationship at till ~ 20 s (R2 = 0.9974) to define the photoresponsivity, which follows the equation below.

where Rpv is the photoresponsivity and Voffset is an offset voltage.

Notably, the quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationship remains consistent with minor variations in Rpv and Voffset for at least 11 days without the need for re-poling (Supplementary Fig. 18), which can be extended to 296 days when re-poling is allowed (Supplementary Fig. 19). In addition, the quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationship can be preserved after repeated illumination (up to 1000 cycles; Supplementary Fig. 20) and at elevated temperature (up to 85 °C; Supplementary Fig. 21). Besides, consistent quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationships are observed across 15 FE-PSs with small device-to-device (D2D) variation (<5%; Supplementary Fig. 22). Therefore, our FE-PSs show good robustness in maintaining Vph-Ilight linearity over time, temperature, and illumination cycle, and across multiple devices.

Such a robust quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationship ensures Rpv to be independent of Ilight, consequently guaranteeing high accuracy and reliability of multiplication. In addition, thanks to the switchable photovoltaic behavior, the Rpv of the FE-PS can be programmed into multi-values, e.g., 4 bits, as shown in Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 23. Besides, a programmed Rpv can be easily retrieved by using the short-circuiting method, as demonstrated earlier (Fig. 5d). The multi-bit programmability, retrievability, and Ilight-independence ensure that the Rpv defined by the photovoltage of the FE-PS can serve as a synaptic weight, which lays the foundation for high-level computing.

To implement in-sensor high-level computing, a FE-PS-based array that itself constitutes an in-sensor ANN is constructed. We first demonstrate multiply-accumulate (MAC) operation, i.e., a fundamental operation in ANN, by using a 1 × 2 FE-PS-based array. In this array, each FE-PS is connected to a Cex of 2200 pF in parallel, and the two FE-PSs are connected in series (Fig. 6a). The two FE-PSs are first set in the same state with Rpv-1 = Rpv-2 = 0.048 V·cm2·mW-1 and Voffset-1 = Voffset-2 = 0.7 V. Various combinations of light intensities, Ilight-1 and Ilight-2, are applied to the two FE-PSs, respectively. Under each combination of Ilight-1 and Ilight-2, the total voltage across the two FE-PSs (Vph-1&2) is measured and its value at till ~ 20 s is regarded as the result. Prior to the application of Ilight-1 and Ilight-2, both FE-PSs are short-circuited. Figure 6b shows the measured Vph-1&2 results for different combinations of Ilight-1 and Ilight-2. It is revealed that the Vph-1&2 is just the sum of the photovoltages produced by the two FE-PSs, which follows the equation below:

a Schematic circuit diagrams of a 1 × 2 FE-PS-based array for demonstrating in-sensor MAC operation. b, c Measured output photovoltages of the 1 × 2 array (i.e., Vph-1&2) at till ~ 20 s when different combinations of Ilight-1 and Ilight-2 are applied to the two FE-PSs in the array. In (b), the two FE-PSs are set in the same state with Rpv-1 = Rpv-2 = 0.048 V·cm2·mW-1 and Voffset-1 = Voffset-2 = 0.7 V, while in (c), they are set in the opposite states with −Rpv-1 = Rpv-2 = 0.048 V·cm2·mW-1 and −Voffset-1 = Voffset-2 = 0.7 V. The theoretical values of Vph-1&2 are indicated by the star symbols. d Schematic diagram of a 4 × 9 FE-PS-based array for the recognition of letters “S”, “C”, “N”, and “U”. e Expected and f measured Vph values (@ till ~ 20 s) of the FE-PSs after programming, which are arranged into 4 groups with each connected to a specific output neuron. The expected Vph values are obtained from the trained weights. The weights are first trained ex situ, then binarized to 1 and −1, and eventually programmed into the array. After programming, the weight 1 (−1) corresponds to an expected Vph value (@ till ~ 20 s) of 2.4 (−2.4) V under the Ilight of 70 mW/cm2. g Temporal output Vphs at different neurons when the letter “C” is presented to the array. h Summary of the measured output Vphs (@ till ~ 20 s) at different neurons for different input letters. The corresponding expected Vph values are shown in the brackets.

Additionally, Eq. (3) also applies when the two FE-PSs are set in the opposite states (−Rpv-1 = Rpv-2 = 0.048 V·cm2·mW-1 and −Voffset-1 = Voffset-2 = 0.7 V), as illustrated in Fig. 6c. These results demonstrate that the FE-PS-based array can implement the MAC operation by using photovoltages. This capability is well attributed to (1) the quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationship of the FE-PS that ensures accurate multiplication and (2) the series connection between FE-PSs that enables the summation of photovoltages.

With the MAC capability, the FE-PS-based array can readily implement high-level image processing functions such as image recognition. An image recognition task is demonstrated experimentally with 4 letters “S”, “C”, “N”, and “U” as input images, as illustrated in Fig. 6d. Each letter image consists of 3 × 3 pixels, with foreground and background pixels valued at 1 and 0, respectively. To classify these letters, a 4 × 9 FE-PS-based array is employed. Here, 9 is the number of pixels. In each pixel, there are 4 subpixels with each corresponding to one FE-PS. The experimental implementation of this array is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 24. When an input letter is projected to the array, the 4 FE-PSs in one pixel are illuminated with an Ilight of 70 mW/cm2 (for the pixel value 1) or left in dark (for the pixel value 0). The FE-PSs with the same subpixel index among different pixels are connected in series, and hence their photovoltages are summed, yielding a total voltage given by:

where Vph-m is the total photovoltage at the m-th output neuron, Rpv-mn is the photoresponsivity of the photosensor with the sub-pixel index m and the pixel index n, Ilight-n is the input light intensity at the n-th pixel. The Vph-m (m = 1, 2, 3, and 4) values are then sent to a softmax function to generate the categorical probabilities. The output neuron with the highest probability determines the predicted class of the input letter.

Ex situ training of the FE-PS-based array is performed using the 4 letter images shown in Fig. 6d as inputs (Supplementary Fig. 25). Subsequently, the trained weights are binarized (Supplementary Fig. 26), and then programmed into the array using a write-and-verify scheme. During programming, the binarized weight 1 (−1) is intended to map an Rpv of 0.03 (−0.03) V·cm2·mW-1 along with a Voffset of 0.3 (−0.3) V. Based on these Rpv and Voffset values, the output Vph (@ till ~ 20 s) of the FE-PS corresponding to the weight 1 (−1) under the Ilight of 70 mW/cm2 is expected to be 2.4 (−2.4) V. Figure 6e, f show that the actual Vph values of all the FE-PSs after programming are closed to the expected Vph values, confirming the success in programming.

Next, the programmed FE-PS-based array is deployed for test, where the letter images same as those used in training are first tested. Figure 6g shows the temporal output Vphs at different neurons when the letter “C” is presented to the array. It is seen that the 2nd neuron with the label “C” outputs the highest Vph, demonstrating the correct recognition of the letter “C”. Figure 6h summarizes the output Vphs (@ till ~ 20 s) at different neurons for different input letters. It is always the neuron whose label matches the input letter that outputs the highest Vph, indicating that all the input letters are correctly recognized. Moreover, the actual output Vph values agree well with the expected values, verifying the high accuracy of the MAC operation in the FE-PS-based array. Further tests with noisy images (Supplementary Fig. 27) demonstrate that the array can maintain 100% recognition accuracy as the noise level increases to 10% (Supplementary Fig. 28). Beyond this noise level, the accuracy begins to decline. Nevertheless, the accuracy at each noise level remains closely aligned with its corresponding theoretical upper limit.

To further evaluate the FE-PS-based array’s capability in handling large images, a simulation of an in situ trained 784 × 10 array for recognizing fashion product images (28 × 28 pixels) is conducted. The simulation methodology is detailed in Methods. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, the FE-PS-based array achieves a recognition accuracy of 80.2% on the test set, approaching the software-based benchmark of 80.8%. These results suggest the great potential of the large-scale FE-PS array for large image recognition.

Discussion

The above results validate the FE-PS-based array as a proof-of-concept for a versatile in-sensor computing system integrating image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions. The array’s functional modes can be rapidly reconfigured by adjusting its circuit interconnections, as schematically illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1 and experimentally demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 30. Therefore, the FE-PS-based array boasts minimal hardware complexity compared to other emerging multifunctional neuromorphic vision systems15,17,30,31,32,76,77,78 (Supplementary Table 1). Although the present FE-PS-based array is experimentally implemented on a small scale, it has great potential for scaling up (Supplementary Note 2). Also noteworthy is that the FE-PS-based array achieves theoretically zero energy consumption in sensing and processing phases, as each FE-PS operates in a self-powered photovoltaic mode (Supplementary Note 3). Additionally, its latency for these phases can be reduced to 100 ms or even lower through device optimization (Supplementary Note 4). These properties highlight the FE-PS-based array’s superiority over conventional von Neumann machine vision systems (Supplementary Note 5).

As the fundamental building block, the FE-PS exhibits both dynamic photovoltage response (for image memorization/pre-processing) and programmable photoresponsivity (for high-level computing). Besides these two essential properties, the FE-PS offers several advantageous features that can enhance system-level performance. First, the above-bandgap photovoltage of the FE-PS greatly benefits the precision and reliability of photovoltage-based image memorization and processing (Supplementary Note 6). In addition, the self-powered photovoltage-based working mode eliminates the needs for current-voltage conversion and external bias application, leading to reduced hardware complexity and energy consumption. Besides, the FE-PS distinguishes itself from emerging optoelectronic synaptic devices for its wide tuning range of retention times (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting its potential in dynamic visual information pre-processing. Specifically, the maximum retention time is extended to ~1100 s (Supplementary Fig. 31), enabling long-term image memorization79,80. Moreover, the robust quasi-linear Vph-Ilight relationship (Supplementary Figs. 18–22), multi-level programmability (Fig. 5f), and retrievability (Fig. 5d), ensures reliable and accurate high-level computing.

However, the present ceramic-based FE-PS exhibits large device area, high voltage/energy consumption for programming, and relatively low photoresponse speed. These limitations can be effectively addressed by leveraging a thin film-based vertically-structured FE-PS. First, the thin film-based FE-PS has been downscaled to ~7.85 × 103 μm2, with substantial potential for further downscaling (Supplementary Note 2). This holds promise for large-scale array integration. In addition, the thin film-based FE-PS can be programmed by using pulse voltages within 2.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 32), showcasing good compatibility with the CMOS circuitry. Besides, its programming energy consumption is significantly reduced to only ~1.6 nJ (Supplementary Note 3), on par with emerging programmable photosensors56,59,75. Moreover, the thin film-based FE-PS can complete the integrated sensing-computing process within 100 ms (Supplementary Note 4), demonstrating comparable speed to its counterparts (Supplementary Table 1).

To sum up, we have demonstrated a versatile in-sensor computing system based on FE-PSs with integrated image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions. The key to achieving these multi-functions lies in the FE-PS which exhibits above-bandgap, dynamically responding, and electrically switchable photovoltages. By leveraging the charging/discharging process, the FE-PS displays gradual photovoltage rise/decay. Such dynamic photovoltage response enables the FE-PS to mimic optoelectronic synaptic behavior, and moreover, renders the FE-PS-based array capable of memorizing images and performing image pre-processing via visual adaptation. Notably, the memory and pre-processing effects can be tuned by ferroelectric polarization, leading to better mimicry of human visual systems. On the other hand, the FE-PS exhibits a giant switchable photovoltage (~30 V) originating from the BPV effect, facilitating high-level computing implementation. Harnessing this switchable photovoltage characteristic, photoresponsivity can be programmed into multi-values (4 bits). In addition, the programmed photoresponsivity can be easily retrieved via short-circuiting. Using the photoresponsivity to map the synaptic weight, the FE-PS-based array acts as an in-sensor ANN, demonstrating MAC capability and achieving 100% accuracy in a 4-class image recognition task (noise level ≤ 10%). Our study offers a solution for integrating image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing functions by using FE-PSs, facilitating the development of versatile in-sensor computing systems for multi-scenario machine vision.

Methods

Device preparation

The PLZT ceramics were purchased from the Dongguan Demi Metal material Co., Ltd company. The company claimed that the PLZT ceramics were prepared by the conventional solid-phase sintering method. The raw materials included PbO (99.9%), ZrO2 (99.9%), TiO2 (99.9%), and La2O3 (99.9%) powders, which were weighed according to the stoichiometry of the desired ceramic composition, i.e., (Pb0.97La0.03)(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3. These powders were ball milled in the ethanol medium. The mixed powders were dried and then calcined at 980 °C for 6 h. The calcined powders were cold pressed into pellets. The pellets were debinded at 550 °C for 6 h, followed by a sintering at 1260 °C for 3 h to obtain the PLZT ceramic samples.

The Au interdigital electrodes were sputtered onto the PLZT ceramics through shadow masks under vacuum, resulting in the Au/PLZT/Au FE-PS devices. The geometric parameters of the Au interdigital electrodes can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Characterizations

The crystalline structure of the PLZT ceramic was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (PANalytical ‘X’ Pert PRO). The cross-section of the PLZT ceramic was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (TESCAN MIRA LMS).

Electrical measurements

The polarization-voltage (P–V) hysteresis loops were measured with a ferroelectric workstation (Radiant Precision Multiferroic). The current-voltage (I–V) characteristics were measured with a source meter (Keithley 6430). In the photovoltaic measurements, 365 nm UV light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with tunable light intensities were used as the light sources while the source meter recorded the photovoltage. In the array-level measurements, multiple FE-PSs were used to construct the arrays with customized interconnections for image memorization, pre-processing or high-level computing.

Simulation of 28 × 28 FE-PS-based array for image pre-processing

To demonstrate that the FE-PS-based array can pre-process images and in turn improve the accuracy of subsequent recognition, a 28 × 28 FE-PS-based array integrated with a 784 × 10 ANN (for subsequent recognition) was simulated.

The original images were modified from the handwritten images (28 × 28 pixels) from the MNIST dataset. The pixel values of the MNIST images were first normalized to 0–1. The normalized images from the training set were used to train the ANN, while those from the test set were further modified as follows. First, the normalized images from the test set were binarized, where the pixels with values higher (lower) than 0.5 were regarded as foreground (background) pixels. Then, the background pixels were all set to a value of 0, while the foreground pixels were randomly assigned one of four values: 1, 0.67, 0.23, and 0.11. These images after binarization and randomization were the original images to be pre-processed by the FE-PS-based array.

The original images were projected onto a 28 × 28 FE-PS-based array for pre-processing, where each FE-PS was connected to a Cex of 100 pF in parallel and all the FE-PSs were pre-poled into the same state (State I, II, or III). Each FE-PS in the array was stimulated by a light pulse train (pulse width: 2.5 s; interval: 3 s; pulse number Npulse was a variable) with light intensity defined by the image pixel value. The pixel values of 1, 0.67, 0.23, 0.11, and 0 corresponded to light intensities of 148, 98, 34, 16, and 0 mW/cm2, respectively. The photovoltage responses of all the FE-PSs were assumed to obey the behavior shown in Fig. 3g. The output photovoltage was further converted to a binary value of “1” if it exceeded 3 V or “0” otherwise. The binarized outputs of all the FE-PSs constituted an output image.

The pre-processed images were sent to a software-based 784 × 10 ANN for label prediction. The output layer of the ANN ultilized a softmax activation function to normalize prediction probabilities. Training of the ANN leveraged the back-propagation (BP) algorithm with a cross-entropy loss metric, optimized via a stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer. For efficient training, a mini-batch approach with a batch size of 20 was adopted. The learning rate was set to 0.15 to ensure stable gradient updates without compromising convergence speed.

Simulation of 784 × 10 FE-PS-based array for high-level image processing

To show the potential of the FE-PS-based array in large image recognition, a 784 × 10 array was constructed by simulation for recognizing 28 × 28-pixel fashion product images from the Fashion-MNIST dataset81. This dataset comprises 70,000 images across 10 distinct clothing categories, with a standard split of 60,000 images for training and 10,000 images for test. Each image after binarization was projected onto the 784 × 10 FE-PS-based array (Supplementary Fig. 29). The array executed MAC operations based on input light intensities and device photoresponsivities, generating 10 different summed photovoltages. These photovoltage values were sent to a softmax function to generate categorical probabilities, with the highest probability determining the predicted category.

In situ training of this large-scale array was simulated using the aforementioned BP algorithm, incorporating a cross-entropy loss function and a SGD optimizer. The batch size and learning rate were set as 16 and 0.002, respectively. During weight update, it was assumed that all the devices in the array followed identical programmable photoresponsivity behavior as shown in Fig. 5f.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the article and the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this study can be requested from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes for simulating a 4 × 9 array for ex situ training, a 28 × 28 array for image pre-processing, and a 784 × 10 array for image recognition are available in Supplementary Software 1.

References

Steger, C., Ulrich, M. & Wiedemann, C. Machine vision algorithms and applications (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Golnabi, H. & Asadpour, A. Design and application of industrial machine vision systems. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 23, 630–637 (2007).

Mennel, L. et al. Ultrafast machine vision with 2D material neural network image sensors. Nature 579, 62–66 (2020).

Zhou, F. & Chai, Y. Near-sensor and in-sensor computing. Nat. Electron. 3, 664–671 (2020).

Zhou, F. et al. Optoelectronic resistive random access memory for neuromorphic vision sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 776–782 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Optoelectronic graded neurons for bioinspired in-sensor motion perception. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 882–888 (2023).

Tan, H. & van Dijken, S. Dynamic machine vision with retinomorphic photomemristor-reservoir computing. Nat. Commun. 14, 2169 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Wearable in-sensor reservoir computing using optoelectronic polymers with through-space charge-transport characteristics for multi-task learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 468 (2023).

Lao, J. et al. Ultralow-power machine vision with self-powered sensor reservoir. Adv. Sci. 9, 2106092 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. All-in-one two-dimensional retinomorphic hardware device for motion detection and recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 27–32 (2022).

Ahmed, T. et al. Fully light-controlled memory and neuromorphic computation in layered black phosphorus. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004207 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Building light stimulated synaptic memory devices for visual memory simulation. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2000945 (2021).

Ma, F. et al. Optoelectronic perovskite synapses for neuromorphic computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908901 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Photo-induced non-volatile VO2 phase transition for neuromorphic ultraviolet sensors. Nat. Commun. 13, 1729 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Networking retinomorphic sensor with memristive crossbar for brain-inspired visual perception. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa172 (2021).

Du, J. et al. A robust neuromorphic vision sensor with optical control of ferroelectric switching. Nano Energy 89, 106439 (2021).

Cai, Y. et al. Broadband visual adaption and image recognition in a monolithic neuromorphic machine vision system. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212917 (2023).

Liao, F. et al. Bioinspired in-sensor visual adaptation for accurate perception. Nat. Electron. 5, 84–91 (2022).

Choi, C. et al. Curved neuromorphic image sensor array using a MoS2-organic heterostructure inspired by the human visual recognition system. Nat. Commun. 11, 5934 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. High performance artificial visual perception and recognition with a plasmon-enhanced 2D material neural network. Nat. Commun. 15, 2471 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Gate-tunable van der Waals heterostructure for reconfigurable neural network vision sensor. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba6173 (2020).

Cui, B. et al. Ferroelectric photosensor network: an advanced hardware solution to real-time machine vision. Nat. Commun. 13, 1707 (2022).

Jang, H. et al. In-sensor optoelectronic computing using electrostatically doped silicon. Nat. Electron. 5, 519–525 (2022).

Pi, L. et al. Broadband convolutional processing using band-alignment-tunable heterostructures. Nat. Electron. 5, 248–254 (2022).

Wu, G. et al. Ferroelectric-defined reconfigurable homojunctions for in-memory sensing and computing. Nat. Mater. 22, 1499–1506 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Computational event-driven vision sensors for in-sensor spiking neural networks. Nat. Electron. 6, 870–878 (2023).

Fu, X. et al. Graphene/MoS2−xOx/graphene photomemristor with tunable non-volatile responsivities for neuromorphic vision processing. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 39 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Mesoscopic sliding ferroelectricity enabled photovoltaic random access memory for material-level artificial vision system. Nat. Commun. 13, 5391 (2022).

Zhang, G. X. et al. Broad band sensory networks with locally stored responsivities for neuromorphic machine vision. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi5104 (2023).

Zhou, G. et al. Full hardware implementation of neuromorphic visual system based on multimodal optoelectronic resistive memory arrays for versatile image processing. Nat. Commun. 14, 8489 (2023).

Dang, B. et al. Reconfigurable in-sensor processing based on a multi-phototransistor–one-memristor array. Nat. Electron. 7, 991–1003 (2024).

Huang, H. et al. Fully integrated multi-mode optoelectronic memristor array for diversified in-sensor computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 93–103 (2025).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferroelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 143–147 (2010).

Lai, S. C., Yao, K. & Chen, Y. F. A battery-less photo-detector enabled with simultaneous ferroelectric sensing and energy harnessing mechanism. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 092903 (2013).

Glass, A. M., Linde, D. V. D. & Negran, T. J. High-voltage bulk photovoltaic effect and the photorefractive process in LiNbO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 25, 233 (1974).

Brody, P. S. High voltage photovoltaic effect in barium titanate and lead titanate-lead zirconate ceramics. J. Solid State Chem. 12, 193–200 (1975).

Yi, H. T., Choi, T., Choi, S. G., Oh, Y. S. & Cheong, S. W. Mechanism of the switchable photovoltaic effect in ferroelectric BiFeO3. Adv. Mater. 23, 3403–3407 (2011).

Ji, W., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. Bulk photovoltaic effect at visible wavelength in epitaxial ferroelectric BiFeO3 thin films. Adv. Mater. 22, 1763–1766 (2010).

Haertling, G. H. PLZT electrooptic materials and applications—a review. Ferroelectrics 75, 25–55 (1987).

Lopez-Varo, P. et al. Physical aspects of ferroelectric semiconductors for photovoltaic solar energy conversion. Phys. Rep. 653, 1–40 (2016).

Young, S. M. & Rappe, A. M. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601 (2012).

Martínez, A. B., Grysan, P., Girod, S., Glinsek, S. & Granzow, T. Direct evidence for bulk photovoltaic charge transport in a ferroelectric polycrystalline film. Scr. Mater. 211, 114498 (2022).

Abdelsamie, A. et al. Crossover between bulk and interface photovoltaic mechanisms in a ferroelectric vertical heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 024047 (2022).

Alexe, M. & Hesse, D. Tip-enhanced photovoltaic effects in bismuth ferrite. Nat. Commun. 2, 256 (2011).

Molina-Mendoza, A. J., Paur, M. & Mueller, T. Nonvolatile programmable WSe2 photodetector. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2000417 (2020).

Kumar, M., Lim, J., Kang, H., Kim, S. & Seo, H. Photon-triggered self-powered all electronics with graphene-silicon hybrid device. Nano Energy 82, 105668 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. Switchable perovskite photovoltaic sensors for bioinspired adaptive machine vision. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 2000122 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. A three-dimensional neuromorphic photosensor array for nonvolatile in-sensor computing. Nano Lett. 23, 4524–4532 (2023).

Fu, C. et al. Dual-mode semiconductor device enabling optoelectronic detection and neuromorphic processing with extended spectral responsivity. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409406 (2024).

Gong, G. et al. An antagonistic photovoltaic memristor for bioinspired active contrast adaptation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409844 (2024).

Kumar, M., Lim, J. & Seo, H. Highly transparent reconfigurable non-volatile multilevel optoelectronic memory for integrated self-powered brain-inspired perception. Nano Energy 89, 106471 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. Perovskite-based memristor with 50-fold switchable photosensitivity for in-sensor computing neural network. Nanomaterials 12, 2217 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Reconfigurable, non-volatile neuromorphic photovoltaics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1303–1310 (2023).

Yu, Y., Deng, Q., Xin, K., Huo, N. & Wei, Z. In-sensor polarimetric optoelectronic computing based on gate-tunable 2D photodetector. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 45, 645–648 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Van der Waals contacted WSe2 ambipolar transistor for in-sensor computing. Nano Res. 16, 12713–12719 (2023).

Cai, Y. et al. In-situ artificial retina with all-in-one reconfigurable photomemristor networks. npj Flex. Electron. 7, 29 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. High photoresponsivity and fast response speed ferroelectric photomemristor for artificial visual system application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2406666 (2024).

Yan, T. et al. A ferroelectric p–i–n heterostructure for highly enhanced short-circuit current density and self-powered photodetection. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2101385 (2022).

Lin, H. et al. In situ training of an in-sensor artificial neural network based on ferroelectric photosensors. Nat. Commun. 16, 421 (2025).

Bhatnagar, A., Chaudhuri, A. R., Kim, Y. H., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat. Commun. 4, 2835 (2013).

Yao, K., Gan, B. K., Chen, M. & Shannigrahi, S. Large photo-induced voltage in a ferroelectric thin film with in-plane polarization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 444 (2005).

Wu, L., Podpirka, A., Spanier, J. E. & Davies, P. K. Ferroelectric, optical, and photovoltaic properties of morphotropic phase boundary compositions in the PbTiO3–BiFeO3–Bi(Ni1/2Ti1/2)O3 system. Chem. Mater. 31, 4184–4194 (2019).

Liang, K. Y. et al. Above-band-gap voltage from oriented bismuth ferrite ceramic photovoltaic cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 12703–12708 (2021).

Salin, P. A., Scanziani, M., Malenka, R. C. & Nicoll, R. A. Distinct short-term plasticity at two excitatory synapses in the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13304–13309 (1996).

Nicoll, R. A. & Schmitz, D. Synaptic plasticity at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 863–876 (2005).

He, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal information processing emulated by multiterminal neuro-transistor networks. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900903 (2019).

Zucker, R. S. & Regehr, W. G. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 355–405 (2002).

Yu, J. et al. Bioinspired mechano-photonic artificial synapse based on graphene/MoS2 heterostructure. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd9117 (2021).

He, H. K. et al. Photonic potentiation and electric habituation in ultrathin memristive synapses based on monolayer MoS2. Small 14, 1800079 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Photonic synapses based on inorganic perovskite quantum dots for neuromorphic computing. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802883 (2018).

Gao, S. et al. An oxide Schottky junction artificial optoelectronic synapse. ACS Nano 13, 2634–2642 (2019).

Yu, R. et al. Programmable ferroelectric bionic vision hardware with selective attention for high-precision image classification. Nat. Commun. 13, 7019 (2022).

Ma, S. et al. A 619-pixel machine vision enhancement chip based on two-dimensional semiconductors. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9328 (2022).

Tan, Y. et al. A bioinspired retinomorphic device for spontaneous chromatic adaptation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206816 (2022).

Lee, S., Peng, R., Wu, C. & Li, M. Programmable black phosphorus image sensor for broadband optoelectronic edge computing. Nat. Commun. 13, 1485 (2022).

Zeng, J. et al. Multisensory ferroelectric semiconductor synapse for neuromorphic computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313010 (2024).

Bai, J. Full van der waals ambipolar ferroelectric configurable optical hetero-synapses for in-sensor computing. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401060 (2024).

Angizi, S., Tabrizchi, S., Pan, D. Z. & Roohi, A. PISA: a non-volatile processing-in-sensor accelerator for imaging systems. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 11, 962–972 (2023).

Talanti, S. et al. CMOS-integrated organic neuromorphic imagers for high-resolution dual-modal imaging. Nat. Commun. 16, 4311 (2025).

Lee, D. et al. In-sensor image memorization and encoding via optical neurons for bio-stimulus domain reduction toward visual cognitive processing. Nat. Commun. 13, 5223 (2022).

Xiao, H., Rasul, K. & Vollgraf, R. Fashion-MNIST: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07747 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (Grant No. 2022YFB3807603), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 92163210 and 52172143), the Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (Grant Nos. 202201000008 and 2022A04J00031), and the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (Grant No. 2024B1515020053).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F. conceived and supervised the research. K.L., S.T., and W.H. prepared the devices. J.C., W.L., B.C., G.T., and X.G. performed the XRD and SEM characterizations. K.L., S.T., H.L., J.O., Z.C., R.T., X.L., and G.Z. conducted the electrical measurements. K.L., S.T., and H.D. carried out the simulations. K.L., S.T., H.L., Z.F., X.G., and J.-M.L. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks In Hyuk Im, Mohit Kumar and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, K., Tan, S., Fan, Z. et al. In-sensor image memorization, low-level processing, and high-level computing by using above-bandgap photovoltages. Nat Commun 17, 408 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67103-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67103-x