Abstract

Pressure injuries (PIs) are prevalent clinical complications arising from excessive normal and shear stresses, severely impacting patients’ lives and increasing healthcare burdens. Current prevention strategies are limited by subjective nature of nursing assessments and inadequate monitoring systems with insufficient durability, limited sensing area, and poor shear sensitivity. Here, we develop a soft, durable, large-area tri-axial stress sensing array optimized via magnetoelastic model. Thin-film encapsulation with interfacial lubrication minimizes strain in large-area multi-layer assembly, while hybrid stiffness architecture reduces interface stresses to 24% of fracture stress. This design is durable (exceeding 100 hours) and cost-effective ($100/unit). Crucially, it enabled quantitative positioning optimization to reduce peak stress by 5.7 kPa (66.8% reduction compared to empirical placements). This is the first tri-axial stress sensing system to offer full-area coverage for PIs prevention and the first to quantitatively optimize skin-interface stress, offering a practical solution to improve surgical safety and postoperative care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pressure injuries (PIs) are common complications worldwide1,2, affecting 1–3 million patients annually in the US alone3 and increasing treatment costs by $21,767–$46,514 per case4. The latest Clinical Practice Guideline defines PIs as localized skin and tissue damage from excessive pressure and shear stress1, emphasizing shear stress as a key pathogenic factor. Superficial PIs result from high shear stress disrupting the epidermal barrier5, while deep PIs arise from combined pressure and shear stress over bony prominences6. Studies reveal that shear stress enhances the risk of PIs by disrupting cellular transport control mechanisms and distorting microvasculature7,8. For example, 3.1 kPa shear stress with 4.6 kPa pressure reduces skin oxygen tension by 37%9, and 20 N shear with 17 N normal force decreases arterial flow by an additional 19% compared to normal force alone10. The combination of shear stress (up to 5 kPa11) and normal stress (peaking at 10-30 kPa12,13) observed in bedridden patients presents a significant risk factor for the PIs development over time. Current PIs risk assessments rely on the subjective Braden Scale14, which leads to elevated risks in surgical settings15. Immobilized patients in high-shear positions, such as prone (23% PIs incidence16,17) and lithotomy (32.4% PIs incidence18), face greater risks than general inpatients (3.3%–14.7% incidence19,20,21,22). Thus, tri-axial stress monitoring in high-risk areas is essential for PIs prevention. Given the variable locations of PIs1 and the risk of device-induced injury, sensing array must fully cover target areas, such as gluteal and lumbosacral regions ( ~ 700 cm²)23, and match human skin stiffness (140–600 kPa)24 for accurate detection and safety. Therefore, there is an urgent need for soft ( ≤ 140 kPa), durable, large-area ( ≥ 700 cm2), tri-axial stress sensing arrays capable of resolving normal ( ≥ 30 kPa) and shear stresses ( ≥ 5 kPa) with real-time visualization to enhance PIs prevention.

Flexible stress sensors based on capacitance25,26,27, inductance28,29,30, resistivity31,32, and piezoelectricity33,34 have gained significant prominence for conformal measurements, but they still face critical limitations for PIs monitoring. Existing pressure-sensing arrays have been deployed for PIs prevention due to the flexibility and robustness12,35,36,37,38. However, these sensors capture only pressure, lack shear stress sensitivity, and remain costly39. Integrating single shear stress sensors with pressure arrays improves skin-interface shear monitoring11, but limited resolution restricts PIs prevention efficacy. Tri-axial force sensors, achieved through multi-element integration40,41, stacked single-axis sensors42,43, and optical method44,45,46,47,48, are limited by small sensing areas (typically ≤3 × 4 cm2) due to complex mechatronic designs and fabrication challenges44,45,49. Moreover, rigid and bulky components such as photodetectors ( ~ 1 GPa, 3.5 × 3.5 cm2)50 risk device-induced injury, and the complex structures are prone to mechanical failure under prolonged nonlinear strains. To the best of our knowledge, flexible stress-sensing arrays that are suitable for clinical PIs monitoring have yet to demonstrate the crucial combination of a large sensing area, robustness, and tri-axial sensitivity. (Table S1).

Recently, magnetic sensing has emerged as a promising approach for force detection by leveraging the continuous, vector nature of magnetic fields to simplify sensor structures. By correlating elastomer deformations with magnetic fields in three-dimensional space, external forces can be derived from the elastomer’s constitutive equations. This approach has shown promise for contact force estimation in small-area robotic finger skin (4 × 4 cm2)51,52. Scalable, large-area, soft sensing arrays with multiple low- Young’s modulus nodes present a promising approach for PIs monitoring. However, the lack of theoretical model linking material properties to sensing range and precision hinders quantitative design, a challenge exacerbated by complex magnetic fields and nonlinear elastomer deformations. Additionally, stiffness mismatch at rigid-flexible interfaces, particularly at chip joints, induce stress concentration53. Previous studies demonstrated that crack propagation occurred at the chip joint under 5-6 MPa stress54, limiting sensing durability under normal-shear stresses. While aligning multiple layers during assembly of small-area arrays is straightforward, assembling large-area soft sensing layers remains challenging55 due to unrecoverable strain accumulation in the elastic layers caused by combined self-weight and surface adhesion, ultimately degrading assembly precision.

To address the limitations of current stress-based PIs monitoring devices, we developed the soft, durable, tri-axial stress sensing array (3D-SSA) with large sensing area, optimized using the magnetoelastic model and fabricated via the improved assembly process. Skin-interface stresses are derived from magnetic flux intensities coupled with tri-axial elastomer deformations. Hybrid stiffness architecture minimizes stress concentrations to achieve long-term durability, while thin-film encapsulation with interfacial lubrication eliminates strain accumulation in large-area multilayer assembly. Inexpensive materials and simplified fabrication reduce the cost to $100. 3D-SSA achieves full-area monitoring of tri-axial stress distributions for over 100 hours across multiple surgeries, enabling quantitative positioning optimization that reduces skin-interface stresses by up to 3.3 kPa (shear) and 2.4 kPa (normal) compared to empirical placements. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first tri-axial skin-interface stresses sensing system with full-area coverage for PIs prevention and the first to quantitatively optimize intraoperative skin-interface stress. It is expected that the proposed method paves a practical way for PIs prevention.

Results

Material, device, and system design

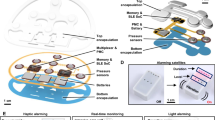

Figure 1a, b presents the exploded view schematic illustration and the photograph of the 3D-SSA including the sensing array, multiplexers and data transmission module. Polyimide (PI) membrane (15 µm in thickness) at the bottom layer serves as a substrate to shield the in-plane stretching of the elastic layer. The system consists of 192 sensing nodes connected via flexible printed circuits (FPC) made of patterned copper on polyimide (PI/Cu/PI, 50/35/50 µm thick, 500 mm long, 20 mm wide). Each node integrates magnetic film, elastic layer, functional chip, flexible circuit and stress reduction components (Fig. 1a). Specifically, magnetic films (diameter of 1.5 mm, thickness of 1.0 mm) are made of Nd2Fe4B with the remanence of 0.44 T. The elastic layer is a 10 mm thick silicone gel with the Young’s modulus of 112 kPa. Functional chips are tri-axis magnetic sensors (MMC5603NJ, CN) with dimensions of 0.8 mm × 0.8 mm × 0.4 mm. Stress reduction structure comprises the rigid shell, cover, and sheet. Furthermore, the shells act as shear keys that mechanically interlock with corresponding grooves in the elastic layer under normal stress (Fig. 1a). Structural stability is further reinforced with a high-strength adhesive (peel strength of 100 ppi, Sil-Poxy, US) to prevent interlayer sliding and detachment throughout long-term operation. The multiplexers, connecting the sensing nodes and the data transmission module, enable sequential data acquisition via the I2C protocol. Data from the sensing nodes are wirelessly transmitted to the back-end server via IEEE 802.11 Wi-Fi protocol and converted to stresses using calibrated models. Consequently, tri-axial stress distributions, reconstructed from discrete sensing nodes, are displayed in real-time as shown in Fig. S1.

a Exploded-view schematic illustrating the layered structure of the array. b Photograph of the device. c Photograph and FEA of FPC in a bending configuration. d Photograph of the lithotomy position used in laparoscopic surgery. e FEA of the normal and shear skin-interface stress distributions in the lithotomy position.

Figure 1c shows the photograph of the flexible circuit encapsulated with PI, which mechanically and electrically protects the electronic components. Parallel wiring enables multiple node configurations within the constrained wiring space. Beam bending theory and Hooke’s law show that bending strain increases with the wire thickness, while tensile strain decreases with the wire width. To achieve the trade-off between wiring density and mechanical robustness, wire width and thickness are set to be 380 μm and 35 μm, respectively. Since FPC and gel layer are adhesively bonded, strains remain compatible at their interface. Given the significantly larger Young’s modulus of the FPC’s copper conductors ( ~ 110 GPa) compared to that of the gel layer ( ~ 112 kPa), stress concentrates substantially in the FPC, and any micro-crack development in the copper conductors could interrupt signal transmission.

Finite element analysis (FEA) confirms that strains in the copper layer remain below the yield strain (0.3%) at a 280 mm bending radius with this configuration (Fig. 1c). This response, together with the elastic stretching (tensile force ~35 N) and twisting ( < 90˚), ensures the robust and conformal skin interface (Fig. S2). In laparoscopic surgery, lithotomy position (Fig. 1d) induces normal and shear stress concentrations in the lumbosacral region, as revealed by FEA (Fig. 1e), consistent with clinical PIs risk observations, justifying its selection as the primary sensing area.

Design approaches

Human skin’s ability to sense mechanical touch from multiple directions relies on the integration of signals from an array of mechanoreceptors, including Merkel disks, Meissner corpuscles, and Ruffini endings. Upon mechanical stimulation, these specialized receptors convert the stimulus into corresponding signals that are propagated along axons to the cerebral cortex for processing. Ultimately, the somatosensory cortex analyzes these signals to distinguish touch position, direction, and magnitude (Fig. 2a). The human tactile perception system exhibits a hierarchical structure, with different receptors at varying skin depths. Inspired by this biological tactile mechanism, we developed the multi-axial load sensing method based on the magnetoelastomer. Similar to the structure of human skin, the 3D-SSA incorporates three functional layers in a hierarchical structure, with magnetic layer on top, elastic layer in the middle and sensing layer at the bottom. Unlike scalar quantities of capacitance, resistance, and inductance, magnetic flux density as a vector enables the calculation of both load direction and magnitude. Functional chips in sensing layer capture flux variations and back-end server calculates the tri-axial loads based on the calibrated model.

a Sensing mechanism and cross-sectional schematic illustration of the sensing node. b Schematic defining the key parameters of the magnetoelastic model. c Relationship between Bz and z for varying Br, rpm, and t. d Relationship between By and y at different z. e Stress-strain curves for elastomer materials of different hardness. Simulated crosstalk interference in Z-direction (f) and X/Y-directions (g) between adjacent sensing nodes as a function of node spacing. h Simulated tilting angles of magnet under uniformly applied normal and shear stress distributions. i Absolute ratios of elastomer deformation errors relative to their maxima along X-, Y-, and Z-directions under uniform normal and shear stresses. j FEA of stress reduction structures.

To quantify the relationship between tri-axial stresses and magnetic flux density, the magnetoelastic model is proposed (Supplementary Note S1) with parameters illustrated in Fig. 2b. Sensitivity and range depend on the properties of elastomer (Young’s modulus E, Poisson’s ratio ν, thickness h) and magnet (remanence Br, diameter rpm, and thickness t). Stress-strain curves for elastomers of different Young’s modulus are shown in Fig. 2e. To avoid device-induced injury, Gel-9300 is selected for the elastic layer due to the similar Young’s modulus to that of human skin. The elastic layer, with dimensions of 450 mm × 350 mm, was designed to fully cover the lumbosacral region. In a typical compliant film, wrinkling is driven by a lower total energy in the conformal contact state compared to the non-conformal contact state56. This energy minimization produces a wrinkling criterion in terms of the material properties and the resulting wrinkle morphology as \(\pi {E}_{target}{h}_{rough}^{2}/\gamma {\lambda }_{rough}\, < 16+{E}_{target}{\lambda }_{rough}^{3}/{\pi }^{3}\overline{EI}\), where Etarget is elastic modulus of the contact surface, γ is the work of adhesion between contact surfaces, hrough and λrough are the vertical height and horizontal spacing of wrinkle protrusions, respectively, and \(\overline{EI}\) = Eh3/[12(1-ν2)] is the bending stiffness of the film. For a standard surgical bed (width = 50 cm, bed foam Etarget = 20 MPa, γ = 0.05 J/m2 between bed foam and silicone film57), hrough and λrough are assumed to be 2 cm and 5 cm (one-tenth of the bed width), respectively; with E = 112 kPa and ν = 0.5 for the elastic layer, wrinkling only occurs when h < 0.86 mm. A 10-mm thickness was selected to provide sufficient compression depth for optimal conformity while preventing wrinkling. This choice ensures large contact areas and reduced skin-interface stresses, and is consistent with the typical thickness of commercial products (Maquet, Fig. S3). Furthermore, the deformation curvature of sensing array under clinical conditions was experimentally characterized using an aluminum foil analog. It revealed gentle bending with curvature radii about 100 cm at the lumbosacral region and 200 cm at the scapular region (Fig. S4, Note.S2). These large radii of curvature effectively mitigate the risk of array wrinkling and folding during patient monitoring.

Given the maximum skin-interface pressure (35 kPa), normal compressive strain reaches 30% with the maximum normal deformation Umax,z = 3 mm. Under these conditions, the magnet parameters were set as follows: t = 1 mm, rpm = 0.75 mm and Br = 0.44 T. This configuration produces a strong Bz variation across the Z-axial sensing distance (green line, Fig. 2c). Figure 2d reveals the non-monotonic relationship between By and y-position across varying z-height. The shear deformation ranges Umax,x/y are set as ±2.4 mm, in which range By exhibits substantial changes. Due to the symmetry of Bx and By, only By variation is presented. These pronounced variations in Bx, By, and Bz collectively enhance sensing sensitivity. To mitigate inter-node crosstalk, the SNR ( = ∆Bnear / ∆Bself) was used to quantify the noise from adjacent node motion. The spacing of 25 mm was selected to maintain a SNR below 3% (Fig. 2f, g).

To quantify potential precision losses from magnet tilting, the computational model integrating elastic and magnetic modeling was developed to evaluate tilting effects and calculate deviations in elastomer deformations under distributed stress gradient β (Supplementary Note S3, Fig. S5). Since the magneto-elastomer exhibits a near-linear elastic response within its operational range, the relative deformation error (δU / Umax = [δx/Umax,x, δy/ Umax,y, δz/ Umax,z]T) is proportional to the relative stress error, which enables direct conversion of deformation inaccuracies into stress measurement errors. Simulated results indicate that the magnet’s maximum tilting angle is <0.4° under uniform Z-normal and Y-shear stress, with shear sensing errors <4% and normal stress errors being negligible (Fig. 2h, i). A comprehensive analysis of varying β (Fig. S6) shows that in clinical settings, where tri-axial skin–interface stresses are typically <15 kPa with β > 0.6, the resulting relative sensing errors are bounded <8.5% for shear stress and <1.0% for normal stress (shear deformation <2.4 mm, normal deformation <1.3 mm, Fig. S6). Furthermore, significant stress concentration was identified at the chip joints due to stiffness differences at the rigid-flexible interfaces (Fig. 2j). To mitigate this, three structural designs are proposed and computationally evaluated via FEA: Design 1 (no protection), Design 2 (rigid shell protection), and Design 3 (rigid shell and reinforcing sheet protection). Design 3 is the most effective by reducing the maximum joint stress to 1.2 MPa, well below crack propagation threshold of 5 MPa, thereby ensuring long-term durability of sensing array.

The assembly accuracy of 3D-SSA was challenged by unrecoverable strains in the large-area gel layer, a result of its surface tackiness and self-weight. To address this, two strategies were employed (Fig. S7): (ⅰ) Thin-film encapsulation to reduce surface tackiness of gel array from 1.55 to 0.15 N (Fig. S8); (ⅱ) interfacial lubrication to minimize array-platform friction. These combined approaches enhance strain recovery and assembly precision, as detailed in ‘Fabrication of 3D Stress Sensing Array’.

Performance specification

The 3D-SSA was designed with essential properties, including sensitivity, range, and waterproofing, to withstand challenges in clinical settings such as bodily fluid contamination, skin temperature fluctuations, and magnetic noise. Figure S9 shows the experimental setup for evaluating sensing performance (detailed in Method) consists of a motorized tri-axial motion stage, six-axis F/T sensor (Nano 17, ATI) and microcontroller (ESP 32, Espressif). This system simultaneously applies loads and measures the resulting magnetic flux density. The tri-axial stresses are then derived from the magnetic data using a calibrated model (Supplementary Note S4). The device demonstrated exceptional thermal stability, with tri-axial magnetic responses showing negligible variation during temperature cycles between 25 °C and 45 °C (Fig. 3a). Both peak amplitudes (Bx = 4.269 ± 0.0064 Gs, CV = 0.15%; By = -1.552 ± 0.0043 Gs, CV = 0.27%; Bz = 19.990 ± 0.0000 Gs, CV = 0.00%) and baselines (Bx = 2.141 ± 0.0092 Gs, CV = 0.43%; By = -2.200 ± 0.0000 Gs, CV = 0.00%; Bz = 13.360 ± 0.0230 Gs, CV = 0.17%) exhibited high consistency, with all coefficients of variation (CVs) below 0.43%. Furthermore, the device showed remarkable mechanical durability, maintaining stable performance during 20,000 pressure cycles with a repeatability error (Δ|B|peak / | B | , where B = [Bx By Bz]T) of only 0.63% (Fig. 3b). Its sensing performance proved consistent across contacting surfaces with different elastic moduli (Ecoflex, E = 100 kPa; PDMS, E = 1 MPa), as shown in Figs. 3c and S10. The drift error (( | BEcoflexi | -|BPDMSi | ) / | BPDMSi | , where i means time during load changes) of 0.5% and 1.7%, and root mean square of errors (RMSE) of 2% and 2.3% for normal and shear stress, respectively. The sensing array also performed robustly on curved surfaces, exhibiting near-identical magnetic responses at flat and curved (100 cm curvature radii) substrates (RMSE for Bx, By, and Bz < 0.04 Gs, 0.05 Gs, and 0.09 Gs, respectively, Fig. S11). In surgical environments, magnetic interference from common instruments (e.g., ultrasonic scalpels, ventilators, anesthesia machines, endoscopes, and shadowless lamps) on the 3D-SSA was negligible (standard deviation of Bx, By, and Bz < 0.002 Gs, 0.006 Gs, and 0.004 Gs, Fig. S12). The system’s performance was further validated considering geomagnetic interference due to bed orientation. Figure 3d shows that changes in surgical bed position (pitching 0° to 20°and rolling 0° to 15°) induced magnetic flux variation (ΔBtot) of up to 2.8 Gs, 5 Gs, and 2.7 Gs along the X-, Y-, Z-axes, significantly exceeding the inherent geomagnetic noise (ΔBgeo) of 0.3 Gs, 0.1 Gs, and 0.1 Gs, respectively. The resulting SNR from adjacent node motion in these directions are 2.9%, 0.9%, and 6.0%, respectively (Fig. 3e). The sensor’s reliability in the presence of bodily fluids and disinfectants was confirmed through immersion and exposure tests. The magnetic response remained invariant after six hours underwater (Fig. 3f) and showed consistent readings during loading and unloading before and after a six-hour exposure to a mixture of porcine blood and alcohol (RMSE of Bx, By, Bz < 0.02 Gs, 0.05 Gs, 0.08 Gs, respectively, Fig. S13). In Fig. 3g, calibration of a single node showed loading ranges of 15.9 kPa (X), 16.3 kPa (Y) and 37.5 kPa (Z) with small RMSE values of 0.12 kPa, 0.11 kPa, and 0.086 kPa, respectively. The average calibrated RMSE across all nodes are 0.12 kPa, 0.3 kPa, and 0.16 kPa along the X-, Y- and Z-directions (Fig. S14). The 3D-SSA captured stress distributions in the lumbosacral region of one human subject (Fig. 3h), with applied shear stresses highlighting its tri-axial sensing capability. Stress field reconstruction method for discrete nodes is described in Supplementary Note S5. Due to the lack of commercial products for tri-axial stress field sensing, normal stresses from three nodes were compared with commercial pressure sensors, yielding errors of less than 1.3 kPa (Fig. 3i).

a Response to temperature changes under cyclic loading. b Durability under 20,000 loading cycles. c Magnetic flux density vs. interfacial substrate modulus (E) under constant normal and shear stresses. d Response to the subject weight and geomagnetic factors during surgical bed rotation. e Cross-talk analysis between adjacent sensing nodes. f Signal stability during 6-hour aqueous immersion. g Tri-axial sensing node calibration: range and accuracy. h 3D-SSA measured stress distributions in the lumbosacral region. i Comparison of pressure measurements with commercial sensor.

Continuous monitoring of tri-axial skin-interface stresses throughout sleep

To evaluate the long-term stability and safety of 3D-SSA, tri-axial stresses were continuously monitored at the lumbosacral skin interface of a healthy subject during 7-hour sleep. The monitoring revealed a biphasic pattern (Fig. 4a, Movie S1): one hour of pre-sleep wakefulness with frequent postural shifts and high stress variability, followed by six hours of sleep with stabilized stress patterns. Corresponding infrared (IR) photographs and stress heatmaps (Fig. 4) illustrate how different postures affect stress distributions. For instance, the supine position (i) generated the shear stresses (τx, τy) up to 8.7 kPa and 6.9 kPa, respectively. In the unilateral hip-knee flexion (ii), the shifted center of gravity altered the shear stresses (maximum τx and τy of 9.5 kPa and 7.3 kPa, respectively) and the compressive stress (σz rising to 14.2 kPa) in the coccygeal region. Side-lying postures (iii, iv) increased the maximum σz to 15.5 kPa due to a reduced contact area, with body turning leading to the maximum τx and τy of 6.7 kPa and 11.1 kPa, respectively. Crossing legs (v) shifted the center of gravity to the sacral region, producing the maximum σz to 14.9 kPa while reducing τx and τy in coccygeal region. Turning to the right side (vi) stretched the skin and increased the maximum τx to 10.9 kPa. Crucially, post-monitoring inspection showed no skin erythema at the lumbosacral skin photographs (Fig. S15), confirming the safety of the 3D-SSA. Notably, spontaneous posture changes every <30 minutes during sleep offer a nature mechanism to mitigate prolonged stress.

Intraoperative monitoring of tri-axial skin-interface stresses

The clinical viability of the 3D-SSA was validated by continuous intraoperative monitoring of skin-interface stresses in supine surgical positions. Case 1 was a 56-year-old female undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Table S1). Figure 5a illustrates the experimental setup, where the sensing array was placed beneath the lumbosacral region and secured to the surgical bed using double-sided adhesive tape (Fig. S16). Device operation and data collection required no modification to standard surgical preparation. Notably, the array was not physically fixed to the skin to allow natural movements during patient transfer and minimize discomfort from restricting contact. Furthermore, the sensing area of the array was designed to be larger than the target skin region to ensure full-area coverage monitoring. During surgery, stress distributions were monitored in real time as the operating table was adjusted according to the surgeon’s instructions and nurse’ clinical experience. In this case, the patient was initially placed in a supine position, and the operating bed was then rolled to the left, followed by head elevation to optimize the surgical view (Fig. 5b), before finally returning to the supine position for wound closure.

Tri-axial average stresses (\({\bar{\tau }}_{x}\),\({\bar{\tau }}_{y}\),\({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}\)) across nine partitions were recorded continuously during the surgical procedure (Fig. 5a, c). During consciousness (i), stresses fluctuated as the patient adjusted the postures; these variations ceased and stresses stabilized upon anesthesia induction (ii). Lateral tilting (iii) increased significantly by 1.02 kPa and 1.58 kPa in partitions ① and ⑦, respectively, with \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}\) remaining stable. Meanwhile, \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}\) increased by 1.4 kPa, 0.96 kPa, and 1.07 kPa in partitions ②, ⑤, and ⑦, respectively, and decreased by 1.4 kPa and 0.76 kPa in partitions ⑧ and ⑨, respectively. Head-up pitching (iv) raised \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}\) significantly by 0.82 kPa, 0.57 kPa, 0.63 kPa and 0.83 kPa in Partitions ①, ②, ④, and ⑤, respectively, with the maximum \({\bar{\tau }}_{x}\) increase of 0.4 kPa in partition ⑦ and the maximum \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}\) increase of 0.52 kPa in partition ④. Tri-axial stresses diminished across most partitions upon returning to the supine position (v). Thus, 3D-SSA effectively captures dynamic changes in tri-axial stresses resulting from intraoperative positioning adjustments.

Optimizing intraoperative skin-interface stresses with 3D-SSA

Intraoperative optimization of skin-interface stresses using 3D-SSA was demonstrated through lithotomy positioning adjustment in the endoscopic surgery (Fig. 1d). In hysteroscopic and laparoscopic surgeries, the lumbosacral region was positioned at the distal end of the surgical bed to facilitate operation (Fig. 1d), and the sensing array was fixed to a standardized location aligned with this region to ensure a consistent monitoring area across multiple surgeries. Finite element analysis initially identified normal and shear stress concentrations in scapular and lumbosacral regions (Fig. 1e). To mitigate this, we established a relation between the bed angles (θ₁, θ₂) and average skin-interface stresses (\({\bar{\tau }}_{y}^{ss},{\bar{\sigma }}_{z}^{ss}\)) using data from five healthy subjects with varying body mass indices (Fig. 6a, b and Movie S2). These relations were visualized as normalized heatmaps (Fig. 6c). Specifically, \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}^{ss}\) and \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}^{ss}\) increased proportionally with θ1 due to lower-limb weight shifting to the sacral region, while both initially decreased and then rose with increasing θ2 as the headboard resisted sliding initially and then compressing the body. The maximum \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}^{ss}\) occurs at θ1 = 30°and θ2 = 0°, corresponding to the maximal sliding force; and maximum \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}^{ss}\) occurs at θ1 = 30° and θ2 = 30°. In clinical practice, empirical lithotomy positions in laparoscopic pelvic surgeries, set by nurses with clinical experience > 10 years, exhibited subjective bias (red points, Fig. 6c). Using the pre-established stress-angle map, nurses were able to interpret real-time 3D-SSA data to adjust bed angles, simultaneously optimizing the surgical view and minimized skin stresses. The high cosine similarity ( > 0.93) of normalized \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}\) and \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}\) heatmaps in the lumbosacral and scapular regions among five subjects confirms the generalizability of this stress-position mapping (Fig. 6d).

a Overview of the lithotomy position setup and the defined bed angles (θ1, θ2). b Distribution of BMIs for five healthy subjects. c Heatmaps visualizing relationship between bed angles and normalized skin-interface stresses. d Inter-subject consistency validated by cosine similarity of normalized stress heatmaps. e Postoperative inspection of sacral skin. f Dynamic changes in average and peak Y-/Z-axis stress across the nine lumbosacral partitions.

The efficacy of data-driven positioning was validated across multiple surgical cases. Adjustments to the bed angles consistently reduced skin-interface stresses without compromising physiological stability. In hysteroscopic surgery (Case 2: 51-year-old female, 62 kg, 157 cm), adjusting the angles from the empirical setting (9°, 2°) to an optimized (9°, 8°) reduced stress across most partitions. The most significant decreases in \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}\) and \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}\) across all partitions (0.8 kPa and 0.41 kPa, respectively) occurred in partition ⑤ (Fig. 6f-i). Furthermore, the maximum τy and σz saw even greater decreases, namely 2.1 kPa (66.8% reduction) and 1.7 kPa (62.9% reduction), respectively, in partition ⑦ (Fig. 6f-ii). In laparoscopic surgery (Case 3: 47-year-old female, 53 kg, 159 cm, Movie. S3), optimizing the angles from (29°, 18°) to (20°, 8°) yielded substantial stress relief. The largest reductions in \({\bar{\tau }}_{y}\) and \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}\) were observed as 0.8 kPa and 0.49 kPa in partition ⑤ (Fig. 6f-iii), while partition ⑦ showed the largest decreases of 3.3 kPa (48.5% reduction) and 2.4 kPa (44.4% reduction) in the maximum τy and σz, respectively (Fig. 6f-iv). This optimization strategy proved sustainable and the force redistribution was not a transient effect, as the optimized configuration maintains stable stress reductions (mean standard deviation ≤ 0.07 kPa) in all cases. Retrospective analysis confirmed that empirical positioning was associated with postoperative PIs (Fig. 6e-i), whereas optimized positions led to reduced skin-interface stress and no observable skin damage (Figs. 6e-ii, S17–S20).

Statistical analysis identified the sacrum area (Partition ⑤) as a consistent focus of maximal stress. Based on this finding, a prophylactic pressure ulcer pad was applied to the sacrum of a high-risk patient (Case 4, 70 years old, high Braden score), and the position was optimized intraoperatively (Fig. S17), resulting in no postoperative injury (Fig. 6e-iii). Critically, all positioning adjustments were performed safely, with stable patient physiology (airway pressure, blood pressure, and heart rate) throughout every procedure (Table S3), indicating no adverse effects from the positioning adjustments.

Discussion

This paper introduced a soft (Young’s modulus: 112 kPa), large-area (1030 cm2), durable ( > 100 hours), tri-axial stress sensing array capable of mapping normal (37 kPa) and shear (15 kPa) stresses across the entire skin-interface. By guiding endoscopic surgery positioning using real-time stress data, this system reduces peak stress by 5.7 kPa with the maximum reduction of 66.8%. This represents a significant advance over existing platforms (Table S1) by enabling durable, full-area, tri-axial stress monitoring through three key innovations: (i) the magnetoelastic model that optimizes design parameters for tri-axial stress sensing; (ii) the hybrid stiffness architecture that confines concentrated stress at flexible-rigid interface to 24% of fracture stress for long-term stability; and (iii) the thin-film encapsulation strategy with interfacial lubrication that prevents strain accumulation and facilitates large-area multilayers assembly. Benchtop studies, numerical simulations, and clinical validation demonstrate the technology’s foundational and practical merits. As a pioneering approach, it offers an advanced pathway to develop devices for preventing surgery-acquired PIs, with broader applications for other medical contexts such as bedridden patients and prosthetic limb users. Further work will integrate hemodynamics, humidity, and temperature sensors to elucidate skin damage mechanisms, while large-scale clinical data collection will refine predictive algorithms and establish quantitative thresholds for PIs risk, thereby advancing personalized precision healthcare.

Methods

Fabrication of 3D stress sensing array

The process began with the creation of the gel layer by brushing the solution of Ecoflex 0010 to the thickness of 0.05 mm onto the cavity surfaces of both the bottom and upper molds. Next, the gel solution, prepared by mixing 9300-A and B (GuoYuan, CN) components at the 1:1 volume ratio, was poured into the container formed by bolting the upper and bottom molds. After curing at 80 °C for 4 hour, the gel layer (350 mm × 450 mm × 10 mm) with its integrated thin rubber membrane was released from the molds and then placed on the bench with alcohol to release the gravity-induced strain prior to handling and assembly. Chemical plating of copper yielded the conductive layer (35 µm) on the PI substrate (50 µm), followed by forming patterned wires with photoresist and etchant. Magnetic chips, resistors, and capacitors were then mounted on the circuits via reflow soldering. To protect these sensitive components from mechanical stresses, an acrylic round sheet (Φ4 mm in diameter, and 0.1 mm in thickness) and shell (Φ2.5 mm in inner diameter, Φ4 mm in outer diameter, 1.5 mm in hole depth and 2 mm in thickness) were bonded to each sensing node using an epoxy resin (7148 AB, Deli). The FPCs were aligned and bonded to the gel layer using the silicone adhesive (Sil-Poxy, US), with the rigid shells serving as alignment pins. Each magnetic film was attached on the elastomer using the same silicone adhesive. Finally, a 15 µm thick PI membrane was bonded on the bottom of the FPCs to shield the soft pad from in-plane stretching.

Characterization of tri-axial stress sensing array

The experimental setup was designed to apply calibrated loads and record sensor output. The motorized test stands applied normal and shear loads with controlled loading and unloading rates. The applied loads were measured by a commercial six-axis F/T sensor (Nano 17, ATI). The data acquisition system synchronized the magnetic flux density from the sensing node with the force measurements from the F/T sensor.

Finite element analysis

ABAQUS was utilized to simulate the skin stress distribution on patients in the lithotomy position and optimize the mechanical performance of FPC interconnects. The FPC analysis ensured that the copper layer experienced no plastic deformation under various external loads, including stretching, bending, and twisting. Concurrently, analysis of the human body identified areas of maximum stresses and its distribution in the intraoperative patients. The copper and PI layers were modeled with hexahedron elements (C3D8R), while the body and surgical bed were modeled with composite shell elements (S4R). The mesh was refined to ensure solution convergence and accuracy. The material properties used were as follows: Elastic modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio (υ) were ECu = 119 GPa and υCu = 0.34 for copper; EPI = 3.2 GPa and υPI = 0.34 for PI; EBed = 10 kPa and υBed = 0.34 for bed; EBody = 10 MPa and υBody = 0.4 for the human body.

Clinical validation protocol with subjects

The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology under number TJ-IRB 202308132. Gender was not considered in the study design as they are not risk factors for PIs. No compensation was provided to the participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. For the preliminary experiment, a healthy volunteer was recruited at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. After being fully informed of the study contents, the volunteer provided written consent (Fig. S21) prior to participating in the skin-interface stress monitoring experiment. Posture changes of the volunteer were simultaneously recorded using an infrared camera (TL-IPC45AW, TP-LINK). In the intraoperative monitoring experiment, the disinfected 3D-SSA was placed on the surgical bed before the patient’s arrival. The system continuously measured pressure and shear stress at the skin interface at high-risk locations, correlating the data with changes in the patient’s position. All data were recorded at the sampling rate of 1.4 Hz, with post-processing enabling real-time calculation and visualization. Following the surgical procedure, skin condition at the sensor mounting location was visually inspected in consultation with nurses to identify any abnormalities. Furthermore, feedback on the device’s acceptance and ease of use was collected from both the attending nurses and subjects via a survey, provided in Supplementary materials (Fig. S22).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are provided in the source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kottner, J. et al. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: The protocol for the second update of the international Clinical Practice Guideline 2019. J Tissue Viability 28, 51–58 (2019).

Lustig, A. et al. The mechanobiology theory of the development of medical device-related pressure ulcers revealed through a cell-scale computational modeling framework. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 20, 851–860 (2021).

Hajhosseini, B., Longaker, M. T. & Gurtner, G. C. Pressure injury. Ann. Surg. 271, 671–679 (2020).

Wassel, C. L., Delhougne, G., Gayle, J. A., Dreyfus, J. & Larson, B. Risk of readmissions, mortality, and hospital-acquired conditions across hospital-acquired pressure injury (HAPI) stages in a US National Hospital Discharge database. Int. wound J. 17, 1924–1934 (2020).

Kottner, J., Black, J., Call, E., Gefen, A. & Santamaria, N. Microclimate: a critical review in the context of pressure ulcer prevention. Clin. Biomech. 59, 62–70 (2018).

Portoghese, C. et al. The role of shear stress and shear strain in pressure injury development. Adv. Skin Wound Care 37, 20–25 (2024).

Shoham, N. & Gefen, A. Deformations, mechanical strains and stresses across the different hierarchical scales in weight-bearing soft tissues. J. Tissue Viability 21, 39–46 (2012).

Slomka, N. & Gefen, A. Relationship between strain levels and permeability of the plasma membrane in statically stretched myoblasts. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40, 606–618 (2012).

Goossens, R. H. M., Zegers, R., van Dijke, G. A. H. & Snijders, C. J. Influence of shear on skin oxygen tension. Clin. Physiol. 14, 111–118 (1994).

Manorama, A., Meyer, R., Wiseman, R. & Bush, T. R. Quantifying the effects of external shear loads on arterial and venous blood flow: implications for pressure ulcer development. Clin. Biomech. 28, 574–578 (2013).

Han, H. et al. Battery-free, wireless multi-modal sensor, and actuator array system for pressure injury prevention. Small 20, 2405493 (2024).

Oh, Y. S. et al. Battery-free, wireless soft sensors for continuous multi-site measurements of pressure and temperature from patients at risk for pressure injuries. Nat. Commun. 12, 5008 (2021).

Mimura, M., Ohura, T., Takahashi, M., Kajiwara, R. & Ohura, N. Jr. Mechanism leading to the development of pressure ulcers based on shear force and pressures during a bed operation: influence of body types, body positions, and knee positions. Wound Repair Regen. 17, 789–796 (2009).

Hoogendoorn, I., Reenalda, J., Koopman, B. F. J. M. & Rietman, J. S. The effect of pressure and shear on tissue viability of human skin in relation to the development of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. J. Tissue Viability 26, 157–171 (2017).

Karahan, E., Ayri, A. U. & Çelik, S. Evaluation of pressure ulcer risk and development in operating rooms. J. Tissue Viability 31, 707–713 (2022).

Lin, S. et al. Prevalence and predictors of pressure injuries from spine surgery in the prone position: do body morphological changes during deformity correction increase the risks?. Spine 42, 1730–1736 (2017).

Choi, S. et al. Factors associated with perioperative hospital acquired pressure injury in patients undergoing spine surgery in the prone position: a prospective observational study. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 36, 45–52 (2024).

Tatsuta, K. et al. Impact of shear stress on sacral pressure injury from table rotation during laparoscopic colorectal surgery performed in the lithotomy position. Sci. Rep. 14, 9748 (2024).

Gefen, A., Creehan, S. & Black, J. Critical biomechanical and clinical insights concerning tissue protection when positioning patients in the operating room: a scoping review. Int. Wound J. 17, 1405–1423 (2020).

Gefen, A. Gravity is our best friend yet can also be our worst enemy: tissue deformations and pressure ulcer risk on the operating table. J. Elast. 145, 153–162 (2021).

Gefen, A., Farid, K. J. & Shaywitz, I. A review of deep tissue injury development, detection, and prevention: shear savvy. Ostomy/Wound Manag. 59, 26–35 (2013).

Chen, Y., Wang, W., Qian, Q. & Wu, B. Comparison of four risk assessment scales in predicting the risk of intraoperative acquired pressure injury in adult surgical patients: a prospective study. J. Int. Med. Res. 51, 03000605231207530 (2023).

Standring, S. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (Elsevier Limited, 2016).

Li, S. et al. An all-protein multisensory highly bionic skin. ACS Nano 18, 4579–4589 (2024).

Xiong, Y. et al. A flexible, ultra-highly sensitive and stable capacitive pressure sensor with convex microarrays for motion and health monitoring. Nano energy 70, 104436 (2020).

Choi, J. et al. Synergetic effect of porous elastomer and percolation of carbon nanotube filler toward high performance capacitive pressure sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 12, 1698–1706 (2019).

Shi, Y. et al. Flexible capacitive pressure sensor based on microstructured composite dielectric layer for broad linear range pressure sensing applications. Micromachines 13, 223 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. A novel induction-type pressure sensor based on magneto-stress impedance and magnetoelastic coupling effect for monitoring hand rehabilitation. Small 20, 2400797 (2024).

Wang, Y., Qu, H. & Diao, S. Flexible inductance pressure sensor for wearable electronic devices. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 18, 652–662 (2023).

Hong, Y. et al. Tactile sensor capable of distinguishing materials based on opposing inductance coils. IEEE Sensors Journal 25, 10673–10684 (2025).

Kim, H. et al. Nonpatterned soft piezoresistive films with filamentous conduction paths for mimicking multiple-resolution receptors of human skin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 55088–55097 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Flexible pressure sensors with ultrahigh stress tolerance enabled by periodic microslits. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 24 (2024).

Ju, M. et al. Piezoelectric materials and sensors for structural health monitoring: fundamental aspects, current status, and future perspectives. Sensors 23, 543 (2023).

Lin, W. et al. Skin-inspired piezoelectric tactile sensor array with crosstalk-free row+ column electrodes for spatiotemporally distinguishing diverse stimuli. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002817 (2021).

Han, S. et al. Battery-free, wireless sensors for full-body pressure and temperature mapping. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaan4950 (2018).

Kwak, J. W. et al. Wireless sensors for continuous, multimodal measurements at the skin interface with lower limb prostheses. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eabc4327 (2020).

Zhang, G., Li, P., Wang, X., Xia, Y. & Yang, J. Flexible battery-free wireless sensor array based on functional gradient-structured wood for pressure and temperature monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2208900 (2023).

Cho, S. et al. Wireless, multimodal sensors for continuous measurement of pressure, temperature, and hydration of patients in wheelchair. npj Flex. Electron. 7, 8 (2023).

Shin, S.-H. et al. Integrated arrays of air-dielectric graphene transistors as transparent active-matrix pressure sensors for wide pressure ranges. Nat. Commun. 8, 14950 (2017).

Jen, Y. H. et al. Development and characterization of vertically stacked tactile sensor with hollow structure. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 5809–5818 (2021).

Xu, T. et al. High-sensitivity flexible tri-axial capacitive tactile sensor for object grab sensing. Measurement 202, 111876 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Human skin-inspired integrated multidimensional sensors based on highly anisotropic structures. Mater. Horiz. 7, 2378–2389 (2020).

Lei, P. et al. Bioinspired integrated multidimensional sensor for adaptive grasping by robotic hands and physical movement guidance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313787 (2024).

Preti, M. L., Bernabei, F., Nardin, A. B. & Beccai, L. Triaxial 3-D-channeled soft optical sensor for tactile robots. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 27956–27965 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. An optical-based multipoint 3-axis pressure sensor with a flexible thin-film form. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi2445 (2023).

Tang, Z., Wang, S., Li, M. & Shi, C. Development of a distal tri-axial force sensor for minimally invasive surgical palpation. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics 4, 145–155 (2022).

Si, C. et al. Highly sensitive and robust soft tri-axial tactile sensors enabled by dual inductive sensing mechanisms. Soft Sci. 5, 6 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Real-time 3-D force measurements using vision-based flexible force sensor. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–10 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. A three-dimensionally architected electronic skin mimicking human mechanosensation. Science 384, 987–994 (2024).

Fang, B. et al. Force measurement technology of vision-based tactile sensor. Adv. Intell. Syst. 7, 2400290 (2025).

Hellebrekers, T. et al. Soft magnetic tactile skin for continuous force and location estimation using neural networks. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 3892–3898 (2020).

Tomo, T. P. et al. A new silicone structure for uSkin—a soft, distributed, digital 3-axis skin sensor and its integration on the humanoid robot iCub. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 3, 2584–2591 (2018).

Khan, Y. et al. A new frontier of printed electronics: flexible hybrid electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905279 (2020).

Alam, M. O., Lu, H., Bailey, C. & Chan, Y. C. Fracture mechanics analysis of solder joint intermetallic compounds in shear test. Comput. Mater. Sci. 45, 576–583 (2009).

Duan, Y., He, S., Wu, J., Su, B. & Wang, Y. Recent progress in flexible pressure sensor arrays. Nanomaterials 12, 2495 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Mechanics of epidermal electronics. J. Appl. Mech 79, 031022 (2012).

Ghatak, A., Vorvolakos, K., She, H., Malotky, D. L. & Chaudhury, M. K. Interfacial rate processes in adhesion and friction. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 4018–4030 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51875221, J.G.; U22A20249, Z.L.; 52188102, J.G.; 52027806, J.G.; 92248304, J.G.; 52173071, Z.L.), Tongji Hospital Research Fund for Nursing Special Project (2023C01, H.C.), National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFE0207000, J.G.) and International Science and Technology Cooperation Project from China Electronics Technology Group Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J.L., H.C. and J.G. conceived the concept and designed the research. Z.J.L. and J.G. formulated the method, designed the experiments and analyzed the results. Z.J.L. and Y.Z. developed the sensing component. Z.J.L. and Y.C. developed the simulated model. Z.J.L., C.G., Y.L., Y.B., B.L. and C.Z. conducted the experiments. Z.J.L. wrote the manuscript. J.G. revised the manuscript. H.C. and Z.L. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaogang Guo, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Chen, Y., Guo, C. et al. Large-area and soft magnetoelastic sensing for normal and shear stress distribution toward pressure injury prevention. Nat Commun 17, 457 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67146-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67146-0