Abstract

Drug-tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) may delay treatment response while drug hypersusceptibility should improve treatment. We investigate the transcriptional regulation of these states in Mtb using a Transcriptional Regulator Induced Phenotype screen combined with an extended, steady-state rifampicin exposure method. We identify three transcription factors (TFs): Rv1359, Rv2887, and Rv3833, whose induction enhances rifampicin tolerance, and four TFs, Rv1189 (sigI), Rv1846c (blaI), Rv2069 (sigC), and Rv3736, whose induction elicits hypersusceptibility. Inducing the TFs blaI and Rv2887 produces opposite phenotypes due to their divergent regulation of the cydA and icl1, genes that we find to reduce redox stress when overexpressed. Thus, Rv2887 induces icl1 expression which contributes to drug tolerance whereas blaI downregulates cydA, which contributes to drug hypersusceptibility. In contrast, divergent regulation of tgs1 and Rv3083 by the TF Rv3736 results in a convergent hypersusceptible phenotype due to the opposing effects of tgs1 and Rv3083 on Mtb permeability to rifampicin. Our findings demonstrate the complex transcriptional regulation of drug tolerance and hypersusceptibility that cannot be captured by studying the activity of individual effector genes. Induction of TFs that regulate Mtb response to drug exposure may either augment or diminish treatment efficacy. These TFs are thus potential new targets for drug development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

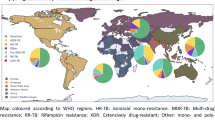

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) currently requires a prolonged 4–6 month course of treatment for drug-susceptible TB and longer treatments for drug-resistant disease1,2. These requirements present a challenge for controlling TB worldwide3,4,5,6,7 especially as approximately 5% of TB patients will still fail treatment and an additional 5% will relapse despite having received a full course of therapy6. Delayed TB treatment responses and subsequent disease relapse have been attributed to drug-tolerant forms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) that necessitate extended treatment due to their slow clearance from the host8,9. Unlike antibiotic resistance, which is the inherited ability of bacteria to grow at high concentrations of antibiotics, drug-tolerance is the ability of a bacterial population to survive better under lethal concentrations of antibiotics without any change in their MIC10. Drug tolerance also provides a reservoir for the evolution of drug resistance by facilitating selection of resistance mutations11,12,13 due to their ability to survive under extended antibiotic exposure10,11.

Drug-tolerant forms of Mtb often employ physiological and metabolic remodeling to withstand drug-mediated killing. Host microenvironments can also induce drug tolerance by modulating growth and metabolism14,15,16. Mycobacterial adaptation to hypoxia through bacteriostasis17,18, phase variation19,20, perturbation in cellular respiration21, mistranslation22 and metabolic shifts23,24 are also known to elicit drug tolerance. Many of these adaptive responses to drug exposure are transcriptionally regulated25,26,27,28,29. Measuring these transient phenotypic changes in isogenic populations is challenging, and in the case of heterogeneous bacterial populations, the results of in vitro time-kill kinetic assays often represent mean population responses, leaving drug-tolerant subpopulations difficult to study10.

Drug hypersusceptibility could be considered as a phenotype opposite of drug tolerance. In general, bacterial metabolic activation can increase susceptibility across several drug classes30,31,32; however, like drug tolerance, hypersusceptible Mtb can sometimes be caused by mechanisms that are specific to individual drugs27,32. Genome-wide CRISPRi knockdown libraries have identified several genes whose repression results in increased susceptibility to one or more classes of anti-tubercular drugs33. Studying transcriptional regulation of drug tolerance and drug hypersusceptibility in the same model system may provide new insights into mechanisms that impact both of these phenotypes.

Genes associated with drug tolerance or hypersusceptibility can be identified through gene disruption34 or by gene knockdown33,35 assays. However, these methods do not describe the regulatory networks associated with the drug-tolerant or hypersusceptible phenotypes. The development of an anhydrotetracycline (ATc) “transcription factor inducible” (TFI) Mtb library containing transcription regulator-induced phenotype (TRIP) plasmids that are designed to recapitulate many transcriptionally regulated phenotypes27,36 has opened up the possibility of characterizing the Mtb regulons and genes responsible for drug-tolerance and hypersusceptibility. We had previously used an in vitro “Transwell-Tolerance-Resistance (TTR)” method to identify drug-tolerant Mtb populations by performing multiple, parallel time-kill assays of barcoded Mtb cultures under steady-state drug concentrations37. Here, we screened a TRIP library using the TTR method to identify regulators of rifampicin tolerance and hypersusceptibility and to identify specific genes and mechanisms responsible for these phenotypes.

Results

Regulators of rifampicin tolerance and hypersusceptibility

To identify Mtb transcriptional regulators responsible for rifampicin tolerance and hypersusceptibility, we performed competition time-kill assays using an Mtb TFI library containing 206 putative transcription factors (TFs) and DNA-interacting proteins. The TFI library included >80% of all predicted Mtb TFs, hypothetical genes and uncharacterized proteins identified as interacting with DNA by ChIP sequencing36. Each strain of the TFI library expressed one of these TFs under an ATc inducible promoter36,38 and the relative fitness of each strain was estimated by deep sequencing27. We reasoned that this TFI library would exhibit a wide range of transcriptionally regulated phenotypes of Mtb. To identify TFs regulating drug tolerance and hypersusceptibility, we exposed the TFI library to prolonged periods of steady-state rifampicin under conditions favoring selection of drug-tolerant strains and negatively selecting hypersusceptible strains using our previously described robotic TTR system37. This assay was performed in a multi-well format enabled us to identify and eliminate culture wells containing high-level drug-resistant mutants, which risked confounding our screen for drug tolerant subpopulations (Fig. 1A). The TFI library in ATc-induced versus uninduced cultures showed comparable time-kill kinetics (Fig. 1B). However, high-resolution studies of the individual TFI strains based on the relative abundance of each TF-specific sequence (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B, Supplementary note) revealed a subset of strains with either increased levels of tolerance or hypersusceptibility to rifampicin compared to the TFI library as a whole. Seven TFI strains continued to show significantly altered rifampicin tolerance or hypersusceptibility after excluding growth defective and underrepresented strains from the TFI library (Fig. 1C). We found that the induction of four TFs: Rv1189 (sigI), Rv1846c (blaI), Rv2069 (sigC), and Rv3736 significantly enhanced rifampicin susceptibility, while three TFs (Rv1359, Rv2887, and Rv3833) augmented tolerance (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Table 1). Like the majority of TFI strains, the empty vector control did not exhibit any significant difference in rifampicin susceptibility upon ATc induction (Fig. 1D).

A An actively growing TFI library was divided into two, and one part is induced with ATc for 20 hours, followed by steady state 10 X MIC (0.1 µg/mL) rifampicin exposure for 16 days in a 24-well transwell plate along with uninduced controls. Cultures from multiple wells were harvested at regular intervals and plated on hygromycin-containing agar media with and without rifampicin. Figure generated using BioRender. B Rifampicin time-kill kinetics, based on total CFU counts of a TFI library exposed to rifampicin as described in (A) above. Each dot represents the CFU from a separate well with at least 4 replicates from day 0 and day 4, 8 replicates from day 12, and 12 replicate cultures from day 16 were considered. C Competitive drug-free growth versus rifampicin time-kill kinetics of the TFI library based on deep sequencing. The relative abundance (ATc-induced versus uninduced) of each TFI strain in the library cultured in the absence of antibiotics (X-axis) is plotted against their relative abundance (ATc-induced versus uninduced) after four days in the presence of steady state rifampicin (Y-axis). The relative abundance of each strain was measured by deep sequencing TF specific regions of the TFI library using a pool of reverse primers specific to each TF contained in the library and one universal forward primer. Enlarged red dots show selected rifampicin tolerant TFI strains while green dots show rifampicin hypersusceptible TFI strains. Empty vector control (VC) is indicated by the black dot. Strains with no significant difference, low abundance or growth defects are shown in gray. D Volcano plot depicting selected TFI strains that developed significant rifampicin hypersusceptibility or tolerance upon ATc induction compared to their uninduced controls. X-axis denotes the fold difference in the relative abundance of the ATc induced versus uninduced TFI library strains and the Y-axis denotes significance. The TFI strain harboring an empty vector control is indicated by a black dot. Significance is estimated using multiple unpaired t-test without correction for multiple comparisons using GraphPad Prism 9.1.

We performed a modified population analysis profiling39 of the TFI library as an orthogonal approach for identifying tolerance and hypersusceptibility associated TFI strains. The entire TFI library (with and without ATc preinduction) was plated on agar medium containing 10X the rifampicin MIC at a cell density ten-fold lower than the natural rifampicin resistance frequency of Mtb (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D). We then identified and eliminated any plates with colonies that became visible by day 21 of incubation as rifampicin-resistant. The plated cultures were then incubated for an additional 14 days, and all new colonies that appeared during this period were collected, pooled and further characterized as potentially tolerance-associated TFI strains that had been able to form colonies once the rifampicin present in the agar media had decreased to below the MIC11. Deep sequence analysis of these emerging colonies showed a relative abundance profile similar to that observed in our liquid TTR study. We found that the hypersusceptible TFI strain containing sigI, blaI, sigC and Rv3736 had a relatively lower abundance in ATc-induced cultures compared to uninduced control, and the tolerance-associated TFI strains containing Rv1359 and Rv2887 showed an elevated relative abundance (Supplementary Fig. 1E). However, unlike our time-kill data, the Rv3833 TFI strain did not show an increased relative abundance. These results parallel the findings in our TTR-based screen and strongly suggest that the ATc induction of the TFs noted above regulates rifampicin susceptibility.

Individual TFI strain time-kill kinetics

We studied the seven aforementioned TFI strains individually for their rifampicin time-kill kinetics. Compared to control cultures, all the ATc-induced TFI strains noted to be hypersusceptible showed a rapid decline in CFU upon exposure to rifampicin (Fig. 2A–D). Notably, the blaI overexpressing TFI strain was completely sterilized by day 16 of rifampicin exposure (Fig. 2B). Conversely, all the TFI strains noted to be rifampicin-tolerant in the TFI library screening showed significant rifampicin tolerance compared to their uninduced controls (Fig. 2E–G). The vector control did not show any difference in their time-kill kinetics upon ATc induction (Fig. 2H). We noted that the rifampin MIC of the ATc-induced TFI strains did not change compared to their uninduced control, confirming that their improved drug fitness phenotype was not due to TF-induced rifampicin resistance (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

A–H Time-kill kinetics of individual TFI strains during steady state 10 X MIC rifampicin exposure. All rifampicin hypersusceptible strains (A–D) showed significantly faster killing compared to their uninduced counterparts. Conversely, rifampicin tolerant TFI strains (E–G) show significantly slower killing upon ATc induction compared to the vector control (H). Studies were performed in quadruplicate transwells and each dot represents one replicate. I Fold difference in (A–H) the CFU between ATc-induced and uninduced replicate cultures of TFI strains at four days of rifampicin exposure. J Determining which hypersusceptible or tolerant TFs reverse their phenotype when knocked down by CRISPRi. TF knockdown strains were pooled and their competitive time-kill kinetics was studied after exposure to steady state rifampicin concentration using TTR. Of the seven TFs, blaI and sigC showed a reversal of the rifampicin susceptible phenotype. The X-axis shows the relative (ATc induced versus uninduced) growth rate of the knockdowns in the absence of rifampicin exposure while the Y-axis shows the relative survival (induced versus uninduced) after four days of rifampicin exposure. K Phenotypes of postulated hypersusceptibility or tolerance effector genes when overexpressed. Each dot represents the mean relative abundance of a given mutant from triplicate culture based on the normalized read count frequency. L Growth versus kill kinetics of CRISPRi knockdown strains. Each dot represents the mean value of three replicates collected from different transwells. M Volcano plot of mRNA expression in ATc induced versus uninduced blaI TFI strains showing significant downregulation of the cydABDC operon (red dots). N Time-kill kinetics of the cydA (mutant 3) knockdown strain when exposed to rifampicin (10 X MIC) for up to 12 days using the TTR method (line indicates mean CFU from 3 biological replicates). Estimated CFU was generated by multiplying the relative abundance of each strain against the total observed CFU from replicates. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, statistical significance estimated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test, GraphPad Prism 9.1. VC = vector control.

Antibiotic tolerance in bacteria can be estimated by measuring their minimum duration of killing (MDK99), which is the time required for a 2 log10 reduction in the starting CFU upon exposure to the antibiotic10. We had found that the TTR assay produced a 2 log10 kill in cultures of wild-type Mtb strain H37Rv mc26230 when incubated in 10 X the rifampicin MIC for 4 days. We thus quantitated the level of ATc-induced rifampicin tolerance or hypersusceptibility in each of the seven selected TFI strains based on the reduction in their CFU after 4 days of rifampicin exposure compared to their uninduced controls. Our results showed varying levels of tolerance and hypersusceptibility, with the blaI-inducing strain showing the maximum susceptibility (0.15-fold survival) and the Rv2887-inducing strain showing the highest level of tolerance to rifampicin (6.6-fold survival) (Fig. 2I).

We investigated whether repression of our seven TFs would reverse their hypersusceptible/tolerant phenotype. Each of these TFs were knocked down in a wild-type H37Rv-mc26230 strain using an ATc-regulated CRISPRi approach40 (Supplementary Fig. 2B, C). Using the TTR assay on the TF knockdown library, we found that the blaI and sigC knockdown strains showed phenotype reversal (Fig. 2J), with the sigC knockdown resulted in rifampicin tolerance in the early time points and the blaI knockdown showed tolerance at all time points (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). On the other hand, the CRISPRi knockdowns of the tolerance-causing TFs did not confer rifampicin hypersusceptibility. We noted that CRISPRi-mediated repression of SigI resulted in a growth-defective phenotype (in the absence of rifampicin exposure) (Fig. 2J). These results suggest that the expression level of some TFs can impact drug tolerance, while other TFs regulate responses specific to either tolerance or hypersusceptibility.

Transcriptional profiling and phenotype modeling

We next sought to identify the transcriptional regulons and effector genes responsible for rifampicin tolerance and hypersusceptible phenotypes. We profiled the transcriptome of each selected TFI strain upon ATc induction and after rifampicin exposure (Supplementary data 1). We then used the transcriptome to statistically associate the magnitude of differentially expressed genes among the TFI strains with their experimentally observed drug response phenotypes. To identify the commonly regulated effector genes among the tolerant and susceptible strains, we performed an elastic net regression analysis, which makes predictions by statistically associating differentially expressed genes with the extent of measured bacterial fitness change (ranging from tolerance to hypersusceptibility) in the presence of rifampicin (Supplementary data 2). Initial unbiased regressions between the differentially expressed genes of the seven selected TFI strains relative to the extent of their tolerance and hypersusceptibility phenotypes at days 4 and 12 of rifampicin exposure revealed a diverse set of preliminary effector genes predicted to have an outsized impact on response to rifampicin. To target our search toward genes that are broadly influential in the rifampicin response, we identified genes of interest that were significantly predictive of rifampicin tolerance phenotypes at both day 4 and 12. We then applied functional ontology labels shared between these genes and repeated a regression analysis for genes grouped by functional label. The functional model using cellular respiration-related genes produced a particularly significant fit (R2 = 0.98, p < 0.005) and highlighted six genes with expression values predictive of rifampicin tolerance: Rv0467 (icl1), Rv2029c (pfkB), Rv3251c (rubA), Rv1623c (cydA), and Rv3174, and Rv0077c (Supplementary Table 2).

Impact of cydA and icl1 on tolerance and hypersusceptibility

We selected five genes (icl1, pfkB, rubA, cydA and Rv3174) to test the impact of model-predicted effector genes on the tolerance/hypersusceptibility spectrum. First, the expression of these five genes was induced under the ATc-inducible TetRO promoter. We then subjected a pool of these five overexpression strains plus a strain containing the empty plasmid to a competition TTR time-kill kinetic assay (Fig. 2K). From this pool, we found that overexpression of cydA and icl1 led to a relative increase in strain survival compared to the empty plasmid control. Overexpression of icl1 imparted sustained tolerance throughout the treatment, whereas overexpression of cydA showed a limited impact (Supplementary Fig. 4A–D). Induction of rubA, pfkB, or Rv3174 expression did not alter the rifampicin susceptibility (Fig. 2K). To further explore the role of cydA and icl1 in rifampicin tolerance, we used CRISPRi-based knockdowns to downregulate the expression of each of these genes individually and determine if this resulted in a reversal of their predicted overexpression phenotype in TTR competition time-kill assays. Each gene was knocked down with three separate guide RNAs (except for rubA due to the relatively small size of this gene) having different predicted knockdown efficiency35. Notably, all three cydA knockdown strains showed increased susceptibility to rifampicin (Fig. 2L, Supplementary Fig. 5A–D). This observation is in consensus with the rifampicin hypersusceptibility upon blaI induction which downregulated the cydABDC operon (Fig. 2M). We found that the time-kill kinetics of the cydA mutants were proportional to the magnitude of cydA knockdown (Fig. 2N, Supplementary Fig. 5E, F) with the cydA_3 knockdown showing a 10-fold decrease in relative abundance compared to the control. The qRT-PCR assay showed different levels of CRISPR interference in the cydA transcription where the cydA_3 mutant showed maximum knockdown compared to the other mutants (Supplementary Fig. 6). Similarly, the transcriptional repression of icl1 also reduced the rifampicin tolerance in the two most downregulated strains icl1_2 and icl1_3, leading to a nearly half-a-log reduction in their relative abundance (Fig. 2L). Notably, cydA is repressed upon bla1 induction, resulting in rifampicin hypersusceptibility, whereas icl1 is induced in the ATc-treated Rv2887 TFI strain, leading to rifampicin tolerance. Together, these results confirm that cydA and icl1 are associated with mycobacterial rifampicin tolerance or hypersusceptibility depending on their expression level. It follows that the Rv2887 and bla1 TFI drug tolerance and hypersusceptibility phenotypes are likely to be at least partly due to their divergent regulation of cydA and icl1.

Suppression of cydA and icl1 potentiate oxidative stress

Since CydA and Icl1 are involved in mitigating oxidative stress in Mtb41,42,43, we measured the redox status of cydA and icl1 knockdown strains using a general oxidative stress marker dye CellRox DeepRed44. The actively growing cydA_3 knockdown strain was marked by a 1.5-fold increase in the mean fluorescence intensity compared to the control strain (Fig. 3A). Exposure to rifampicin further elevated the oxidative stress signal to a 2.5-fold increase in mean fluorescence intensity. The cydA_2 and cydA_1 strains, which showed lower levels of cydA suppression, had proportionally lower levels of oxidative stress (Supplementary Fig. 7A–C). Unlike the cydA knockdown phenotype, the icl1 knockdown did not result in an enhanced signal during the phase of active growth; however, rifampicin exposure substantially increased the oxidative stress (Fig. 3B) compared to the empty vector control (Fig. 3C). In an alternative assay for oxidative stress, we measured protein carbonylation levels of each knockdown strain before and after rifampicin exposure. Our results showed elevated carbonylation of the cydA mutant in the absence of rifampicin, that further increased with rifampicin exposure (Fig. 3D) while the icl1 mutant showed a marked difference in the carbonylation levels only after rifampicin exposure compared to the control (Fig. 3E). Empty vector plasmid controls did not show any differences between uninduced and ATc-induced replicates (Fig. 3F). To test whether induction of the bla1 TF would phenocopy our cydA knockdown findings, we measured the redox status of the blaI TFI strain with CellRox before and after rifampicin exposure. Upon ATc induction, the blaI TFI strain showed significantly higher ROS levels during rifampicin exposure (Supplementary Fig. 7D, E).

A,B CellRox DeepRed staining of (A) cydA and (B) icl1 CRISPRi knockdown strains showing significantly higher fluorescence upon exposure to 10 X MIC rifampicin. Note that the cydA knockdown showed elevated oxidative stress even before the rifampicin exposure in contrast to the icl1 knockdown where oxidative stress was increased only upon by rifampicin exposure. The vector control (C) did not show any difference between the induced and uninduced samples before and after rifampicin exposure. D–F Protein carbonylation assay to measure the oxidative stress of (D) cydA and (E) icl1 CRISPRi knockdown strains before and after rifampicin exposure. The cydA knockdown showed elevated carbonylation before and after rifampicin exposure while the icl1 mutant showed significantly higher levels of carbonylated proteins upon rifampicin exposure. No significant difference was observed in the induced and uninduced samples of vector control (F). G–I Susceptibility of cydA (G) and icl1 (H) knockdown mutants to hydrogen peroxide. Both cydA and icl1 knockdowns were hypersusceptible to H2O2 compared to the vector control (I). Exposure to 0.1% H2O2 led to sterilization of all cultures in 24 h. Data from triplicate cultures are shown. Error bar indicates standard deviation. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, statistical significance estimated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test, GraphPad Prism 9.1). KD= knockdown.

Since knocking down cydA and icl1 compromised the ability of Mtb to counter oxidative stress, we also investigated whether these knockdowns would show enhanced susceptibility to external oxidative agents, such as H2O2. We found that both knockdown strains exhibit H2O2 hypersensitivity (Fig. 3G, H) compared to the vector control (Fig. 3I). The icl1 knockdown showed the most H2O2 sensitivity with a nearly 100-fold reduction in the observed CFU at 0.01% concentration of H2O2 compared to the cydA mutant, which showed 10-fold decrease in CFU. Similar results were observed after exposure to menadione (Supplementary Fig. 8A–C). The bla1 TFI strain also showed high sensitivity to H2O2, while none of the other TFI strains showed increased susceptibility to H2O2 upon ATc induction (Supplementary Fig. 8D). Finally, we tested whether the increased rifampicin tolerance among the cydA and icl1 overexpression strains is due to their antioxidant activity. Indeed, the overexpression of cydA reduced oxidative stress but not upon icl1 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 8E, F). However, we did not see any significant change in their susceptibility to H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 8G). These results suggest that both cydA and icl1 genes are directly involved in maintaining the intracellular redox status of rifampicin-treated Mtb, which also enables them to modulate rifampicin susceptibility.

We also measured the sensitivity of cydA and icl1 knockdowns to anti-TB drugs other than rifampicin, hypothesizing that altered bacterial redox status would increase susceptibility to other antibiotics that induce redox-mediated physiological changes42,43,44,45. Measuring MICs, we found that the cydA knockdown showed increased susceptibility to bedaquiline (BDQ), and the cytochrome bc1:aa3 inhibitor telacebec (Q203)46 (Supplementary Table 3). These results are consistent with prior observations47,48. On the other hand, the icl1 knockdown showed increased susceptibility only to INH. We also performed time-kill assays on the cydA and icl1 knockdown strains in the presence of these drugs. Consistent with the MIC data, the cydA mutant was killed at a greater rate by BDQ and Q203 (Fig. 4A, B). Exposure to Q203 resulted in complete sterilization of the cydA mutant culture as early as 4 days, highlighting the hypersusceptible phenotype of Mtb lacking an alternative terminal oxidase48. The cydA knockdown did not show increased kill rates upon exposure to INH in our study (Fig. 4C), and it was killed more slowly by moxifloxacin and ethambutol (Fig. 4D, E) compared to the rifampicin time-kill assay performed in parallel (Fig. 4F). Reduced killing by moxifloxacin may be due to interference of moxifloxacin-mediated killing under a deregulated terminal oxidation pathway49, but the reason underlying reduced killing of the cydA knockdown by ethambutol is unclear. In contrast, icl1 knockdown did not show altered susceptibility to any drugs tested (Fig. 4G-L), except for INH at day 4 (Fig. 4I) and Rifampicin (Fig. 4L). This observation is in accordance with the previous report on the role of icl1 in survival under INH exposure42. Together, these results show both commonalities and differences in the effect of cydA versus icl1 knockdowns on susceptibility to anti-TB drugs, suggesting that even related drug tolerance mechanisms may lead to different treatment outcomes.

TTR based time-kill kinetic assays of (A–F) cydA knockdown strain performed against A bedaquiline (BDQ), B telacebec (Q203), C isoniazid (INH), D moxifloxacin (MXF) E ethambutol (EMB) and F rifampicin (RIF). G–L Time-kill kinetics of icl1 knockdown strain against G bedaquiline (BDQ), H telacebec (Q203), I isoniazid (INH), J moxifloxacin (MXF) K ethambutol (EMB) and L rifampicin (RIF). Data from biological triplicates are shown. High CFU shown in the INH treated cultures are drug resistant mutants appeared during the late time points (C,I). Kill curves of cydA and icl1 are represented with different color dots for clarity. Line indicates mean CFU obtained from three biological replicates. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, statistical significance estimated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test, GraphPad Prism 9.1.

TF-induced altered cell wall permeability

Our RNA sequencing studies of rifampicin-treated Mtb TFI strains suggested that activation of distinct regulons could produce hypersusceptible or drug-tolerant phenotypes distinct from the bla1 and Rv2887 controlled regulons or levels of cydA and icl1 expression. Reduced drug permeability is a known mechanism of drug tolerance in bacteria, and Mtb possesses a complex cell wall with high lipid content that makes it tolerant to many currently used antibiotics50,51. We hypothesized that other TFI strains might develop drug tolerance or hypersusceptibility by altering their drug permeability. To test this, we incubated each TFI strain in FITC-conjugated rifampicin (RIF-FITC)52 to measure their cell wall permeability. Flow cytometry assay showed a concentration-dependent accumulation of the RIF-FITC in the wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Of the four rifampicin hypersusceptible TFI strains, sigC and Rv3736 showed a higher uptake of RIF-FITC with 1.2 and 2.4-fold increase in mean fluorescence intensity compared to the uninduced control, respectively (Fig. 5A–D). However, no change in RIF-FITC fluorescence was observed among the bla1 and sigI hypersusceptible TFI strains or among any of the tolerant TFI strains (Fig. 5A). Also, we did not see any phenotype reversal upon knockdown of the sigC or Rv3736 genes (Fig. 5E–G, Supplementary Fig. 9B, C). Mtb is prone to developing deactivation mutations in genes related to phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIMs) synthesis when repeatedly cultured in vitro53. Since PDIMs are known to be associated with drug tolerance and changes in membrane permeability54, we measured the PDIM levels of selected TFI strains, confirming that both sigC and Rv3736 possessed normal PDIM concentrations. The tolerant Rv3833 TFI strain, however, was found to be missing PDIMs (Supplementary Fig. 9D).

A Flow cytometry analysis of hypersusceptible (green) and tolerant (red) TFI strains with and without ATc induction, followed by incubation with RIF-FITC. Y-axis indicates the mean fold difference in the mean fluorescence intensity of ATc induced versus uninduced cultures of three replicates. B–D Histograms of the data shown in panel A for B sigC, C Rv3736 and D vector control (VC). Light blue = ATc induced, red = uninduced, dark blue = overlap. E–G Flow cytometry histograms of CRISPRi knockdowns of TFs in panel A with and without ATc induction followed by incubation with RIF-FITC E sigC, F Rv3736 and G vector control. Light blue = ATc induced, red = uninduced, dark blue = overlap. H RIF-FITC fluorescence-based cell sorting of the knockdown library distributing CRISPRi mutants based on cell wall permeability. Each dot represents a single mutant. X-axis indicates the sort fractions collected (F1 = lowest fluorescence, F4 = highest fluorescence). Y-axis indicates the average fold difference in the relative abundance of each mutant (ATc versus No-ATc) in each fraction (data from 4 biological replicates). Enlarged black dots indicate vector control (VC). Colored dots indicate mutants that have significantly higher representation in F4 and lower representation in F1 when ATc is induced. Gray dots indicate insignificant phenotypes. I Drug-free growth versus rifampicin kill kinetics of the knockdown mutant library based on the relative abundance of each mutant. Enlarged version of the selected region (dotted) is shown in linear scale for clarity. (J–M, left) Flow cytometry histograms of CRISPRi strains knocking down the TFI-regulated genes postulated to be responsible for increased permeability to RIF-FITC (J) tgs1, (K) fabD, (L) rocD1, (M) PPE1. (J–M, right) Time-kill kinetics of the CRISPRi knockdown strains, with and without ATc induction, shown in their respective left panel. Each data point is derived from the relative abundance of the individual knockdown strain and observed CFU from three biological replicates. Mean CFU with standard deviation is shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, statistical significance estimated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test, GraphPad Prism 9.1.).

We further investigated the effector genes regulated by sigC and Rv3736 whose induction increased cell wall permeability. At least 30 genes were differentially expressed in either ATc-induced sigC or Rv3726 TFI strains compared to their uninduced controls. Of these, we used CRISPRi to knockdown all genes that were independently expressed as well as the first gene from each differentially expressed operon (for a total of 16 knockdowns, Supplementary Table 4). This “knockdown library” was stained with RIF-FITC and sorted into four fractions based on fluorescence intensity ranging from low to high. Deep sequencing analysis of the sort fractions (with and without ATc), revealed increased relative abundance of tgs1 (Rv3130), fabD (Rv2243, KAS operon), rocD1 (Rv2322) and PPE1 (Rv0096) mutants in the highest fluorescence fraction and relative depletion in the lowest fluorescence fraction (Fig. 5H). In parallel, we performed a competitive rifampicin time-kill assay using the library to see if the altered permeability correlated with rifampicin susceptibility (Fig. 5I). Three of the four knockdown strains became attenuated for growth upon ATc induction, especially the fabD knockdown, making it difficult to interpret ATc-induced versus uninduced time kill studies of these three strains in the presence of rifampicin (Fig. 5I, J–M). We also tested the susceptibility of the knockdown strains towards isoniazid (INH) and Moxifloxacin. We found that Rv3083 knockdown strain was tolerant to INH but not to Moxifloxacin (Supplementary Fig. 10A, B). However, the tgs1 knockdown appeared to have normal growth in both the presence and absence of ATc induction, and comparative time-kill assays of the tgs1 knockdown confirmed that this strain was indeed hypersusceptible to rifampicin, INH and moxifloxacin (Fig. 5I, J; Supplementary Fig. 10A, B).

Finally, to confirm the role of effector genes in rifampicin tolerance and susceptibility, we selected TFI strain Rv2887, which exhibits rifampicin tolerance at least partially through the upregulation of icl1 and the TFI strain Rv3736, which exhibits rifampicin hypersusceptibility at least partially through the upregulation of Rv3083. We then generated double transformants of TFI Rv2887 harboring a CRISPRi KD construct for icl1 and a double transformant of TFI Rv3736 with Rv3083 knockdown construct. When induced with ATc, the double transformants simultaneously activated their respective TF and knocked down their putative effector gene. We then performed a TTR study with the double transformants, exposing them to 10X MIC rifampicin for 4 and 12 days. As expected, the ATc-induced TFI-Rv2887 + pLJR965-icl1 double transformant showed a reduced rifampicin-tolerant phenotype compared to the controls (Fig. 6A). Whereas the ATc-induced TFI-Rv3736 + pLJR965-Rv3083 double transformant showed a mitigation of the rifampicin hypersusceptible phenotype of TFI 3736 (Fig. 6B).

Change in CFU counts for ATc induced versus uninduced strain constructs in the absence of rifampicin (X-axis) and upon exposure to steady state 10X MIC of rifampicin for 4 days (closed circles) and 12 days (open circles) (Y axis). A Drug tolerant Rv2887 TFI strain (red) compared to icl1 (tolerance effector gene when induced) knockdown (KD) strain (gray) and the double transformant Rv2887 induced plus icl1 KD strain (orange). B Hypersusceptible Rv3736 TFI strain (green) compared to Rv3083 KD strain (gray) and double transformant Rv3736 induced plus Rv3083 KD strain (orange). In both cases, the single KD strains show a phenotype that is opposite to their respective TFI strain (in which the effector gene is positively regulated), while the respective double transformant (TFI induced - effector gene KD) strains show a partial reversal of their respective TFI strain phenotype. Data obtained from three biological replicates. The mean CFU from replicates was used to estimate the fold difference with and without ATc induction.

Discussion

Bacterial gene expression is modulated primarily by transcriptional regulators that enable dynamic adaptation to transiently changing environments by fine-tuning relevant phenotypes. Regulators of transcription include sigma factors, alternate sigma factors, which directly assist RNA polymerase to initiate transcription, and other nucleoid-associated proteins that indirectly modulate transcription by changing the topology of chromosomal DNA. The TRIP library used in our study contained all Mtb genes that are associated with the DNA binding network identified by ChIP sequencing, representing >80% of all Mtb TFs36. Our TRIP screening approach is expected to recapitulate most transcriptionally regulated phenotypes of Mtb, making it well-suited to identify the transcriptional networks and effector genes regulating antibiotic tolerance and hypersusceptibility17,27,36. Our study identified at least two transcriptionally regulated mechanisms of drug tolerance and hypersusceptibility in Mtb, one involving differential susceptibility to rifampicin-induced redox stress and a second involving drug penetration. Both mechanisms could be induced by at least two different TFs, each with only partially overlapping transcriptomes. Mtb TFI strains that conferred drug tolerance or hypersusceptibility as measured by time-kill assays did so without causing an apparent change in their MIC. These observations conform to classical definitions of drug tolerance. Contrary to previous reports on the impact of growth rate and metabolism in modulating mycobacterial antibiotic tolerance24,55, the mechanisms we describe showed no apparent association between TF-induced growth defect and rifampicin tolerance. Performing TRIP assays using the TTR platform enabled us to extend time-kill kinetic studies for up to 16 days as required to detect changes in killing in a slow responding pathogen, such as Mtb. The multi-well and serial well harvesting approach used with this platform also enabled us to remove test wells containing drug-resistant mutants, excluding results generated by de novo resistance rather than drug tolerance37.

Our identification of different TFs that are each individually able to induce drug tolerance or hypersusceptibility suggested several possibilities. First, several TFs may co-regulate genes responsible for these phenotypes. Alternatively, several TFs might control distinct regulons, but these regulons could each impact common metabolic pathways. Our transcriptomic analysis suggested that TF controlled regulons have minimal overlap. Perhaps one of our most important observations relates to the complexity of tolerance and hypersusceptibility phenotypes. For example, although induction of icl1 or cydA confers similar drug tolerance phenotypes through redox homeostasis42,56, the divergent expression of these genes under the regulation of different transcription factors resulted in drug tolerance or drug hypersusceptibility depending on their positive or negative regulation. The TF Rv2887 upregulated icl1 expression, which contributed to rifampicin tolerance, whereas the TF bla1 (Rv1846c) downregulated cydA, contributing to rifampicin hypersusceptibility. We also discovered an analogous phenomenon in a third TF, Rv3736 that increased rifampicin entry into Mtb, producing a hypersusceptible phenotype. Interestingly, Rv3736 upregulated Rv3083 expression while downregulating tgs1. The knockdown of Rv3083 caused a decrease in Mtb permeability to rifampicin, while the tgs1 knockdown increased Mtb permeability. Thus, the divergent expression of these two genes under the regulation of Rv3736 led to a convergence on the same hypersusceptible phenotype. In sum, our work describes the complexity underlying drug tolerance and hypersusceptible phenotypes when studied at the level of transcriptional regulation that cannot be captured by studying the activity of individual effector genes (Supplementary Fig. 11).

We speculate that cydA directly reduces ROS formation associated with rifampicin treatment, as suggested by the dose-dependent knockdown response to ROS formation among the cydA CRISPRi mutants, where the maximum knockdown was associated with the highest ROS signal. We also speculate that the absence of cydA might elevate the activity of Cytochrome bc1:aa3, thereby increasing bacterial membrane potential41 and indirectly promoting the generation of ROS through NDH-2. Unlike cydA, which possesses a housekeeping function of neutralizing the respiratory ROS, the knockdown of icl1 showed elevated ROS only upon rifampicin treatment. Although a direct link between icl1 and oxidative stress is not known57, icl1 downregulation has been associated with the differentially detectable forms of Mtb, which exhibit elevated oxidative stress response58. Deletion of icl1 has also resulted in decreased Mtb survival in activated murine macrophages59. Taken together, we speculate that rifampicin exposure leads to ROS generation that is directly or indirectly neutralized by the cydA or icl1 and their absence could result in elevated oxidative damage and cell death60. Although we speculate that the phenotype of the icl1 knockdown is related to suppression of its function as a key enzyme in the glyoxylate cycle, icl1 also has a role in the methylcitrate cycle and propionate metabolism, which could also be related to our findings61.

We identified a second TF-regulated mechanism of drug hypersusceptibility that appeared to be caused by altered cell wall permeability. Reduced cell wall permeability is a known mechanism of antibiotic tolerance50,62. Here, we show that two of the four rifampicin susceptible TFI strains (sigC and Rv3736) exhibited elevated permeability due to the TF-induced changes to their cell walls, demonstrating that changes in cell wall permeability can also have effects opposite to drug tolerance. Our results suggest that permeability changes due to sigC and Rv3736 induction and the action of these TFs on tgs1, fabD, the kas operon, rocD1 and PPE1 gene expression results in intracellular accumulation of rifampicin. The tgs1 gene codes for a triacylglyceride synthase that is required for the bioenergetics during dormancy and cell wall integrity63, and was found to modulate tolerance to rifampicin, INH and Moxifloxacin. On the other hand, the kas operon is associated with mycolic acid synthesis, and the downregulation considerably affected the growth rate64. While the hypersusceptibility phenotype that we observed might have been caused by perturbation in the redox homeostasis or by altered metabolism, this would not explain the increased fluorescence caused by FITC accumulation within the Mtb cells. Alternatively, our results are consistent with proposals that destabilizing mycobacterial cell wall by targeting lipid biosynthesis could be synergistic with intracellular-acting drugs, such as rifampicin52.

Although our study does not recapitulate the interactions between different transcription factors, our results point to multiple opportunities to subvert key Mtb regulons so that drug activity and/or intrabacterial drug penetration is enhanced. The current study was unable to identify the mechanisms of sigI-mediated rifampicin hypersusceptibility or the tolerance induced by Rv1359 or Rv3833; therefore, the action of these transcription factors requires further investigation. Nevertheless, the observation that the phenotypes caused by these three TFI strains were not explained by either drug penetration or redox status clearly demonstrates the multiple mechanisms by which Mtb can control key phenotypes.

We demonstrated (Fig. 2) that survival differences between ATC-induced versus uninduced TFI strains were statistically significant at virtually all time points (except for Rv3833), strongly suggesting that these observations are robust. We believe that the changes in drug tolerance and hypersusceptibility observed are also likely to have clinical significance, especially when viewed in the context of a disease, such as TB, where months-long treatment could compound even relatively small changes in survival during drug exposure. Also, when one considers the analogous situation of MIC testing, a fourfold change MIC is considered clinically significant. Furthermore, we have previously reported that even <2 fold differences in MIC can be highly significant clinically when treatment outcomes are concerned65. In conclusion, our results point to multiple opportunities to subvert key Mtb regulons so that drug activity and/or intrabacterial drug penetration is enhanced. Agents that can use Mtb’s own regulatory activity against itself could represent a new way to treat this disease.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture methods

We used an auxotrophic mutant of M. tuberculosis mc26230 for the experiments. Cells were cultured in MiddleBrook 7H9 media containing 0.2% glycerol, 0.05%Tween 80, 10% OADC with 24 µg/mL calcium pantothenate. We used 7H11 agar medium for plating and CFU enumeration in all time-kill kinetic experiments. TFI transformants were generated using individual plasmids harboring TFs under the Tetracycline promoter. For transforming Mtb, actively growing cells were harvested, washed thrice with 10% glycerol in deionized water and resuspended in 10% glycerol. 100 ng of plasmid DNA was added into 200 µL of cell suspension and electroporated using BioRad electroporator (1000 Ω, 2.5 kV and 25 µF) in a 2 mm cuvette and recovered in drug-free 7H9 media supplemented with 10% OADC and 24 µg/mL calcium pantothenate for one day. Cells were then plated over hygromycin (50 µg/mL) containing 7H11 agar medium to select the TFI transformants. One colony from each transformant plate was selected and verified by PCR using a TF specific forward primer with a constant reverse primer for the vector backbone sequence. To generate the TFI library, individual TFI transformants and an empty vector control strain were cultured in 7H9 medium with hygromycin and pooled at equal cell density.

The TTR experiment was performed as described previously37. In brief, secondary cultures of TFI pool from early log-phase (0.2 OD595nm) were divided into two and one culture was induced with 100 ng/mL of ATc for 18 h at 37 °C. The cultures were then diluted 1:10 using fresh 7H9 medium with or without ATc and distributed (200 µL) in 24 well transwell plates with 0.1 µg/mL (10X MIC) rifampicin (Sigma #R3501), INH (0.5 µg/mL, Sigma #I3377) or moxifloxacin (0.5 µg/mL, Sigma #SML1581) containing 7H9 medium in the basolateral wells using a Hamilton STAR robotic liquid handler. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a shaker incubator and the media containing rifampicin (±ATc) was replaced on alternate days. At every time point, 50 µL culture from quadruplicate transwells were collected, washed once to remove traces of the drug, and directly plated undiluted in equal halves over drug-free (for deep sequencing) and on rifampicin (1 µg/mL) agar plates to detect the presence of any drug-resistant mutant in the culture at that time point. Any well that contained one or more rifampicin resistant mutant colonies was excluded from the analysis to avoid confounding resistant mutants generated de novo during extended rifampicin treatment. Serial dilution and plating were also performed from the same cultures to estimate the original CFU per well.

DNA isolation, library preparation, and deep sequencing

Colonies isolated from different time points were used for DNA extraction using the phenol: chloroform method. Briefly, the cells were resuspended in Tris-EDTA (Ph 8.0) containing 4 mg/mL of lysozyme (Sigma L6876) and lipase (Sigma #62302) and incubated at 37 °C dry bath for overnight. Lysis was carried out by adding 2% SDS (final concentration) and incubated at 60 °C for 20 min with intermittent mixing. The lysate was mixed with equal volume of phenol: cholorofm:isoamyl alcohol solution (ThermoFisher Scientific #17909), centrifuged and the aqueous phase was collected. This step was repeated, and the aqueous phase was extracted once with chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (sigma C0549). The DNA was precipitated by adding 1/10th volume of 3 M Sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and three volumes of ethanol. The precipitated DNA was washed once with 70% ethanol and dissolved in 1 X TE buffer (pH 8.0, ThermoFisher Scientific #12090015). DNA was quantitated using the Qubit™ dsDNA quantification kit (ThermoFisher Scientific #Q32851).

For the library preparation, TF specific region was amplified from the pEXCF plasmid using the previously reported protocol36. All primers and oligos used in this study were purchased from Sigma as 100 uM solution (Supplementary data 3). Briefly, a pool of TF-specific primers (206) (mixed at equimolar concentrations) used along with a vector backbone-specific reverse primer. We performed a 20 cycle PCR amplification using the Phusion® high fidelity polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific #F532S). The amplicons were gel purified and used for library preparation using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina as per the manufactures protocol. The samples were end-repaired, adapter ligated, and duel indexed using Illumina Nextera XT V2 indexing primers. Samples were purified by AMPure XP, magnetic beads (Beckman Colter #A63880), quantitated using Nanodrop and pooled at equimolar concentrations. The library quality was checked using Tapestation (Agilent) and used for the Next-generation sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq platform in a single end sequencing format.

The deep sequence data was analyzed using a pipeline created using MATLAB. First, the reads were extracted using the TF specific primer and vector backbone-specific sequence. To further increase the stringency, we iterated the sequences with a TF specific internal sequence. Sequences with read counts above the previously described cut-off limit were considered for further analysis and graph plotting and significance calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.2. The abundance of a given mutant is estimated by dividing the number of read counts of each TFI-specific sequence by the total number of reads in each sample. To estimate the relative abundance, the abundance of each TFI in the ATc-induced sample is divided by the abundance of the same sequence in the uninduced control sample. The mean relative abundance of a given TFI strain was estimated from replicate samples.

Antibiotic depletion assay

The drug depletion assay measured rifampicin tolerance among the TFI strains. In brief, actively growing TFI pools (with and without ATc induction) were plated over 10 X MIC rifampicin (0.1 µg/mL) containing agar medium (in addition to hygromycin, with and without ATc) at a density of 107 per plate (one log below their natural mutation frequency) and incubated at 37 °C. Colonies appeared on the 5th week of incubation after the antibiotic in the agar medium got depleted. Any plate observed with colony on or before 3 weeks of incubation was considered as a rifampicin resistant mutant and excluded from the analysis. The colonies were used for genomic DNA isolation, library preparation and deep sequencing to estimate the relative abundance of TFI strains as described earlier. The tolerance of each TFI strain was measured by estimating their relative abundance compared to the uninduced control cultures; the empty vector strain was used as an internal control.

RNA sequencing and transcriptome analysis

Secondary cultures of actively growing TFI strains (0.6 OD 600 nm, in triplicates) (with and without ATc induction) exposed to 10 X MIC rifampicin for one day were harvested and used for RNA isolation using the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (74104). The cells were resuspended in 500 µl TRIzol™ (ThermoFisher Scientific #15596026) and lysed by bead beating (two cycles of 45 seconds each, lysing Matrix B, MP biomedical). The lysate was mixed with 100 µl of chloroform:isoamyl alchohol and centrifuged. The supernatant was mixed equal volume of 70% ethanol and passed through the RNeasy spin column. The column was washed once with 700 µl buffer RW1 and twice with 500 µl RPE buffer and the RNA was eluted using DEPC treated water. DNase1 treatment of the RNA samples was performed (ThermoFisher Scientific # EN0521) as per the manufacturers protocol. RNA was quantitated using the Qubit™ RNA high sensitivity kit (ThermoFisher Scientific #Q32852). The rRNA depletion was carried out using the riboPOOL™ kit (siTOOLs Biotech) as per the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was used for library preparation using NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina as per the manufacturer's protocol. Dual-indexed samples were purified using AMPure XP magnetic beads and quantified using Qubit fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The samples were pooled at equimolar concentrations and used for deep sequencing using Illumina NextSeq platform. The differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 software.

Phenotype modeling of tolerant and hypersusceptible strains

Gene expression levels in the various TFI strains were regressed against observed phenotypes using elastic-net regularization66, using a grid-search 4-fold cross-validation strategy to optimize the ratio of L1 and L2 penalties used. Model predictors were limited to significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs; >2-fold change, p < 0.05) between induced and uninduced samples in the presence of RIF (294 genes), as assessed via DESeq267 in R using the DESeq2 package. Models were generated against day 4 and day 12 CFU readouts for each strain. Genes identified as predictive in multiple models were grouped by functional category as annotated in Mycobrowser68. Repeat regressions were then run, limiting predictors to DEGs labeled with each of these functional categories, respectively. Elastic-net regression and subsequent analysis was performed in Python using the scikit-learn and seaborn packages.

CRISPRi knockdown and gene overexpression

Knockdown of selected TF genes was performed using the previously described protocol40 (Supplementary Table 5). Briefly, available PAM sequences with a maximum reported repression were selected based on the previous report40. One or more PAM sequences were identified and a 20-nucleotide sequence downstream of the PAM was selected with a dinucleotide spacer between the PAM and guide sequences. The forward and reverse oligo sequences were custom synthesized (Sigma Aldrich) having BsmBI restriction site overhangs (Supplementary data 4). The oligonucleotides (25 µM each) were mixed in the NEBuffer™ 2 (NEB #B7002S) and annealed in a boiled water with gradual cooling in room temperature. The annealed product was cloned into BsmBI predigested pLJR965 using T4 DNA Ligase (ThermoFisher Scientific #EL0011) and the ligated product was used for transforming E. coli (TOP10 chemically competent cells) via heat shock method and selected over Kanamycin LB agar plates. Plasmid isolated from a clone verified, single E. coli transformant culture was used for electroporation of wild-type mc26230 cells. For the conditional knockdown of TFs, transformants were subcultured in 7H9 media with and without ATc (100 ng/mL) induction for 5 days to achieve target gene depletion, followed by the TTR assay. The ATc concentration was maintained throughout the period of antibiotic exposure by including it in all TTR media exchanges. To estimate the knockdown efficiency of the transformants, we isolated RNA from the ATc-induced and control cultures using TRIzol™ method as described above. The samples were DNase I-treated (ThermoFisher Scientific #EN0521), and the RNA concentration was estimated using Quibit. For qPCR assay, we used TaqPath™ one-step RT-PCR (ThermoFisher Scientific #A15299) 4 X master mix with gene-specific primers and the DNA-binding fluorophore EvaGreen® using LightCycler® 480 real time PCR (Roche). Knockdown efficiency was estimated based on the ΔΔCt method with 16S rRNA used as the internal control. To estimate the relative abundance of the knockdown strains, colonies were harvested from experiments and used for DNA extraction. Amplification of the region containing the guide sequence was performed using primers carrying Illumina adapter overhangs (Supplementary Table 6), followed by dual indexing and next-generation sequencing on the MiSeq platform.

For gene overexpression studies, we replaced the hsp60 promoter of the pMV306 vector with the tetRO promoter from the pKW08-Lx plasmid (pMV306-tetRO-T2)69. The TF genes were amplified from the Mtb genomic DNA using a forward primer containing Xba1 restriction sequence and a reverse primer carrying an 11-base pair barcode along with the HindIII restriction site using Phusion™ high-fidelity polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific #F530S). The PCR product was gel-purified, double-digested with Xba1 and HindIII, (ThermoFisher Scientific #FD0684, FD0504) and ligated into the predigested vector using the same set of enzymes. This construct was used for transforming E. coli and selected over Hygromycin agar plates (50 µg/mL). Plasmids isolated from the positive clones (verified by double digestion to see the released product) were used for transforming Mtb mc26230 and selected over 7H11 hygromycin agar plates. For overexpression, early log-phase cultures (0.2 OD 600 nm) were induced with 100 ng/mL ATc for 24 h and used for the time-kill experiments and next-generation sequencing.

Flow cytometry assay for permeability and oxidative stress

To measure the permeability of the TFI transformants towards rifampicin, a previously reported Rifampicin-FITC conjugate was used52. To check the concentration-dependent uptake of the conjugate, wild-type mc26230 from mid-log phase culture (100 µL) was harvested and resuspended in 500 µL of 7H9 medium containing Rifampicin-FITC in 2-fold increasing concentrations (0.125 µg/mL to 32 µg/mL). The tubes were incubated at 37 °C shaker for 3 hours. The cells were harvested and washed once with an excess volume of ice-cold PBS and fixed in 2% formaldehyde for 30 min in ice. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in PBS and used for flow cytometry analysis using BD FACSCelestaTM. A gated population of 20,000 cells was analyzed from all samples and the fluorescence intensity was estimated using FlowJo software. Gating cells were based on the coordinate readouts obtained from running intact cells over forward and side scatter. A standard curve was plotted from known concentrations of the Rifampicin-FITC conjugate and a concentration from the linear range was selected (2 µg/mL) for further experiments. To estimate the altered membrane permeability due to TF induction, 100 µl of actively growing TFI strains (+/- ATc pre-induction) were washed once with 7H9 media (to remove any trances of ATc) and incubated with fresh 7H9 broth containing 2 µg/mL of Rifampicin-FITC conjugate for 3 h at 37 °C and processed as described earlier. For sorting experiments, rifampicin-FITC-stained CRISPRi pool (with and without ATc preinduction) was directly used for sorting into four fractions based on their fluorescence intensity on a BD FACSARIA™ III cell sorter in a BLS2 facility. At least two million cells from each fraction were collected, and genomic DNA was isolated. The sgRNA sequence region was amplified and used for library preparation as described above. Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo software_v10.10. The ratio of mean fluorescence intensity between TF induced versus uninduced cultures was used for calculating the relative permeability. Statistical significance was estimated using Students T test (GraphPad Prism 10).

To measure the redox homeostasis upon TF induction, we stained cells from TF-induced and uninduced cultures with 1 µM CellROXTM Deep Red dye for 3 h at 37 °C. For positive control, cells were pre-exposed to 100 µM menadione for one hour 37 °C and used for staining in parallel. Stained cells were washed and fixed as described previously and used for flow cytometry analysis. To estimate the early changes in the redox status of TFI strains, ATc-induced and uninduced cultures were exposed to 10X MIC rifampicin for 24 h followed by staining with CellROXTM Deep Red dye and processed similarly for flow cytometry analysis.

Protein carbonylation assay

Mtb cells from actively growing phase (0.6 OD600nm, 3 mL) and 10 X MIC rifampicin treated cultures were collected and washed once in 1 X PBS and resuspended in 700 µl of BPER™ reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific #78243). Cells were lysed by bead beating using matrix II (MP biomedicals) with two cycles of 45 s each with 2 min incubation in ice in between the cycles. The lysate was centrifuged to collect the supernatant (500 µl) and the genomic DNA was removed by DNase1 treatment (1 unit of DNase1 per 200 µl of lysate). The protein concentration in the lysates was estimated using Pierce™ BCA protein assay Kit (Thermo Scientific # 23227) and the samples were diluted to make a concentration of 10 µg/mL. Concentration-normalized samples were used for the carbonylation assay using the OxiSelect Protein carbonyl ELISA kit (CellBiolabs # STA-310) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Oxidative stress susceptibility assay

To check the susceptibility to external oxidative stress on the TFI and knockdown mutants, we exposed the Mtb strains to three different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1%) or Menadione (0.1, 1.0, 10 µg/mL). For this, actively growing cells (1 mL) from the mid-log phase were harvested and washed twice in 1X PBS (containing 0.05% Tween 80) to remove traces of catalase and resuspended in the same buffer containing H2O2 or menadione for 12 h. Cells were plated before and after the H2O2 treatment to see the reduction in the CFU and the difference in the CFU between the induced vs uninduced was used for measuring the relative sensitivity towards H2O2.

Assay for Minimum inhibitory concentration

Drug spotted 384 well plates were prepared using Eco®. Antibiotics of the desired concentration range in two-fold increasing concentration were selected and actively growing cells (100 µl, 104 per well) were seeded. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 7 days for growth. Alamar blue (5%) and Tween-80 (0.6%) were added to each well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured using Bioteck spectrophotometer at 550 and 600 nm. A ratio of 550/600 was used to estimate growth inhibition.

Thin Layer Chromatography

Apolar lipids were analyzed from Mtb to study PDIMs as described previously53,70. Briefly, 4 ml Mtb cultures were grown to OD600 of ~1.0, and supplemented with 8 μCi 14C-propionate each (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, MO). After incubation at 37 °C for 48 h, the cell pellets were harvested and apolar lipids extracted with 2 ml CH3OH/0.3% NaCl (10:1) and 1 ml petroleum ether by vortex mixing for 15 min. The phases were separated by centrifugation and the upper layer dried under air, resuspended in petroleum ether (200 μl), each sample (20,000 cpm) was analyzed on normal-phase TLC plates with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (98:2, v/v, three times). The TLCs were visualized using a phosphorimager (Typhoon 9400).

Statistics and reproducibility

Details on the statistical method used for each experiment are provided in the corresponding figure legends. We used GraphPad Prism 9.1. for calculating significance. Phenotypes observed from screening experiments were confirmed by using axenic mutants. At least three biological replicates were used for all experiments, and additional replicates were used when necessary. Data exclusion details are provided in the figure legends and in the reporting summary.

Biosafety statement

We used an avirulent, pantothenate auxotrophic strain of M. tuberculosis (MC2 6230) for all experiments. Bacterial cultures were handled in a biosafety level 2 facility in biosafety cabinets using established protocols approved by the Rutgers Institutional Biosafety Committee. Bacterial cell sorting was performed in a FACS ARIA sorter installed within a class II biosafety cabinet at the Flowcytometry core facility at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All relevant raw data for the figures and Supplementary Figs are provided in the source data. All oligos and primer sequences used in this manuscript are provided in the supplementary data files. The next generation sequencing raw data files including the RNA sequencing data pertaining to this study are deposited and publicly available in NCBI SRA under the Bioproject ID PRJNA1298380. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom MatLab codes for analyzing the NGS data is available at https://github.com/jeesms39/TTR_TRIP-NGS-analysis (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17393375). Detailed description of the code usage is provided as a supplementary note.

References

Nyang’wa, B. T. et al. A 24-week, all-oral regimen for rifampin-resistant tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 2331–2343 (2022).

Mase, S. R. & Chorba, T. Treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin. Chest Med. 40, 775–795 (2019).

Dartois, V. & Rubin, E. J. Shortening tuberculosis treatment-a strategic retreat. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 939–941 (2023).

Dorman, S. E. et al. Four-month rifapentine regimens with or without moxifloxacin for tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1705–1718 (2021).

Nahid, P. et al. Executive summary: official American thoracic society/centers for disease control and prevention/infectious diseases society of America clinical practice guidelines: treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 63, 853–867 (2016).

Marx, F. M. et al. The temporal dynamics of relapse and reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 58, 1676–1683 (2014).

Ruan, Q. L. et al. Recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis after treatment success: a population-based retrospective study in China. Clin. Microbiol Infect. 28, 684–689 (2022).

McCune, R. M., Feldmann, F. M., Lambert, H. P. & McDermott, W. Microbial persistence. I. Capacit. Tuber. Bacilli Surviv. Steriliz. Mouse Tissues J. Exp. Med. 123, 445–468 (1966).

Wallis, R. S. et al. Drug tolerance in mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial agents Chemother. 43, 2600–2606 (1999).

Balaban, N. Q. et al. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 441–448 (2019).

Sebastian, J. et al. De Novo Emergence of Genetically Resistant Mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the Persistence Phase Cells Formed against Antituberculosis Drugs In Vitro. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 61, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01343-16 (2017).

Levin-Reisman, I. et al. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science 355, 826–830 (2017).

Jones, R. M., Adams, K. N., Eldesouky, H. E. & Sherman, D. R. The evolving biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1027394 (2022).

Manina, G., Dhar, N. & McKinney, J. D. Stress and host immunity amplify Mycobacterium tuberculosis phenotypic heterogeneity and induce nongrowing metabolically active forms. Cell Host Microbe 17, 32–46 (2015).

Chang, D. P. S. & Guan, X. L. Metabolic Versatility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during Infection and Dormancy. Metabolites 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11020088 (2021).

Sarathy, J. P. et al. Extreme Drug Tolerance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Caseum. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 62, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02266-17 (2018).

Galagan, J. E. et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory network and hypoxia. Nature 499, 178–183 (2013).

Wayne, L. G. & Sohaskey, C. D. Nonreplicating persistence of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 139–163 (2001).

Bellerose, M. M. et al. Common Variants in the Glycerol Kinase Gene Reduce Tuberculosis Drug Efficacy. mBio 10, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00663-19 (2019).

Safi, H. et al. Phase variation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis glpK produces transiently heritable drug tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19665–19674 (2019).

Lobritz, M. A. et al. Antibiotic efficacy is linked to bacterial cellular respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 8173–8180 (2015).

Javid, B. et al. Mycobacterial mistranslation is necessary and sufficient for rifampicin phenotypic resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1132–1137 (2014).

Lee, J. J. et al. Transient drug-tolerance and permanent drug-resistance rely on the trehalose-catalytic shift in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 10, 2928 (2019).

Baek, S. H., Li, A. H. & Sassetti, C. M. Metabolic regulation of mycobacterial growth and antibiotic sensitivity. PLoS Biol. 9, e1001065 (2011).

Deter, H. S., Hossain, T. & Butzin, N. C. Antibiotic tolerance is associated with a broad and complex transcriptional response in E. coli. Sci. Rep. 11, 6112 (2021).

Goh, E. B. et al. Transcriptional modulation of bacterial gene expression by subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 17025–17030 (2002).

Ma, S. et al. Transcriptional regulator-induced phenotype screen reveals drug potentiators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 44–50 (2021).

Ma, S. et al. Integrated modeling of gene regulatory and metabolic networks in mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004543 (2015).

Peterson, E. J. R., Ma, S., Sherman, D. R. & Baliga, N. S. Network analysis identifies Rv0324 and Rv0880 as regulators of bedaquiline tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16078 (2016).

Stokes, J. M., Lopatkin, A. J., Lobritz, M. A. & Collins, J. J. Bacterial metabolism and antibiotic efficacy. Cell Metab. 30, 251–259 (2019).

Allison, K. R., Brynildsen, M. P. & Collins, J. J. Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature 473, 216–220 (2011).

Batchelder, J. I., Taylor, A. J. & Mok, W. W. K. Metabolites augment oxidative stress to sensitize antibiotic-tolerant Staphylococcus aureus to fluoroquinolones. mBio. 15, e0271424 (2024).

Li, S. et al. CRISPRi chemical genetics and comparative genomics identify genes mediating drug potency in mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 766–779 (2022).

Sassetti, C. M., Boyd, D. H. & Rubin, E. J. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 77–84 (2003).

Bosch, B. et al. Genome-wide gene expression tuning reveals diverse vulnerabilities of M. tuberculosis. Cell 184, 4579–4592 (2021).

Minch, K. J. et al. The DNA-binding network of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 5829 (2015).

Sebastian, J. et al. Origin and dynamics of mycobacterium tuberculosis subpopulations that predictably generate drug tolerance and resistance. mBio 13, e0279522 (2022).

Snasel, J. et al. Phosphofructokinases A and B from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Display Different Catalytic Properties and Allosteric Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031483 (2021).

Andersson, D. I., Nicoloff, H. & Hjort, K. Mechanisms and clinical relevance of bacterial heteroresistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 479–496 (2019).

Rock, J. M. et al. Programmable transcriptional repression in mycobacteria using an orthogonal CRISPR interference platform. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16274 (2017).

Mascolo, L. & Bald, D. Cytochrome bd in mycobacterium tuberculosis: a respiratory chain protein involved in the defense against antibacterials. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 152, 55–63 (2020).

Nandakumar, M., Nathan, C. & Rhee, K. Y. Isocitrate lyase mediates broad antibiotic tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 5, 4306 (2014).

Joshi, H., Kandari, D., Maitra, S. S., Bhatnagar, R. & Banerjee, N. Identification of genes associated with persistence in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1302883 (2024).

Shee, S. et al. Moxifloxacin-mediated killing of mycobacterium tuberculosis involves respiratory downshift, reductive stress, and accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 66, e0059222 (2022).

Dwyer, D. J. et al. Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E2100–E2109 (2014).

Pethe, K. et al. Discovery of Q203, a potent clinical candidate for the treatment of tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 19, 1157–1160 (2013).

Berney, M., Hartman, T. E. & Jacobs, W. R. Jr A Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome bd oxidase mutant is hypersensitive to bedaquiline. mBio 5, e01275–01214 (2014).

Kalia, N. P. et al. Exploiting the synthetic lethality between terminal respiratory oxidases to kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis and clear host infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7426–7431 (2017).

Lee, B. S. et al. Inhibitors of energy metabolism interfere with antibiotic-induced death in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 1936–1943 (2019).

Abadi, F. J., Carter, P. E., Cash, P. & Pennington, T. H. Rifampin resistance in Neisseria meningitidis due to alterations in membrane permeability. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 40, 646–651 (1996).

Jarlier, V. & Nikaido, H. Mycobacterial cell wall: structure and role in natural resistance to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123, 11–18 (1994).

McNeil, M. B., Chettiar, S., Awasthi, D. & Parish, T. Cell wall inhibitors increase the accumulation of rifampicin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Access Microbiol. 1, e000006 (2019).

Domenech, P. & Reed, M. B. Rapid and spontaneous loss of phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown in vitro: implications for virulence studies. Microbiology 155, 3532–3543 (2009).

Wang, Q. et al. PE/PPE proteins mediate nutrient transport across the outer membrane of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 367, 1147–1151 (2020).

Zheng, E. J. et al. Modulating the evolutionary trajectory of tolerance using antibiotics with different metabolic dependencies. Nat. Commun. 13, 2525 (2022).

Schildkraut, J. A. et al. RNA sequencing elucidates drug-specific mechanisms of antibiotic tolerance and resistance in mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 66, e0150921 (2022).

Ahn, S., Jung, J., Jang, I. A., Madsen, E. L. & Park, W. Role of Glyoxylate Shunt in Oxidative Stress Response. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 11928–11938 (2016).

Saito, K. et al. Oxidative damage and delayed replication allow viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis to go undetected. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabg2612 (2021).

McKinney, J. D. et al. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406, 735–738 (2000).

Kohanski, M. A., Dwyer, D. J., Hayete, B., Lawrence, C. A. & Collins, J. J. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 130, 797–810 (2007).

Gould, T. A., van de Langemheen, H., Munoz-Elias, E. J., McKinney, J. D. & Sacchettini, J. C. Dual role of isocitrate lyase 1 in the glyoxylate and methylcitrate cycles in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 940–947 (2006).

Hui, J., Gordon, N. & Kajioka, R. Permeability barrier to rifampin in mycobacteria. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 11, 773–779 (1977).

Daniel, J. et al. Induction of a novel class of diacylglycerol acyltransferases and triacylglycerol accumulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as it goes into a dormancy-like state in culture. J. Bacteriol. 186, 5017–5030 (2004).

Slayden, R. A. & Barry, C. E. 3rd. The role of KasA and KasB in the biosynthesis of meromycolic acids and isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 82, 149–160 (2002).

Colangeli, R. et al. Bacterial factors that predict relapse after tuberculosis therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 823–833 (2018).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B: Stat. Methodol. 67, 301–320 (2005).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Kapopoulou, A., Lew, J. M. & Cole, S. T. The MycoBrowser portal: a comprehensive and manually annotated resource for mycobacterial genomes. Tuberculosis 91, 8–13 (2011).

Williams, K. J., Joyce, G. & Robertson, B. D. Improved mycobacterial tetracycline inducible vectors. Plasmid 64, 69–73 (2010).

Wilson, R. et al. Antituberculosis thiophenes define a requirement for Pks13 in mycolic acid biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 499–506 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI162598 and AI146194) to DA, SM and DS. This work utilized ECHO 650 Liquid Handler that was purchased with funding from a National Institutes of Health SIG grant 1S10OD026890-01A1. Dr. William Jacobs is acknowledged for providing the auxotrophic strain of Mtb MC(2)6230. We thank Mainul Hoque and Veera D’Mello at the Rutgers Genomic core for performing next generation sequencing. We thank Tammy Galenkamp from the Rutgers Flow Core for helping with flow cytometry experiments. We are thankful to Tanya Parish from Seattle Children’s Research Institute for providing Rifampicin-FITC conjugate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S., S.M., D.S., and D.A. conceptualized the project. J.S., P.K., S.M., D.S., and D.A. developed the methodology. J.S., S.M., E.B., S.S., and P.K. conducted experiments. J.S., S.M., E.B., T.R., and A.T. performed data analysis and visualization. J.S. and D.A. wrote the original draft. J.S., D.A., S.M., and D.S. reviewed and edited the paper. D.A. and D.S. acquired the funding, coordinated and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Babak Javid-, who co-reviewed with Hemant Joshi, Elizabeth Campbell, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions