Abstract

The cognitive function of tracking multiple objects, essential for autonomous mobile vehicles or autonomous robots, involves object detection and their temporal associations. While significant progress has recently been made in machine learning to elaborate the similarity matrix between the objects that have been recognized and the objects detected in the current video frame, less progress has been made on the assignment problem that ultimately determines temporal associations, which is a combinatorial optimization problem. Here we show a vehicle-mountable multiple object tracking system with a flexible assignment function for tracking through multiple long-term occlusion events. To solve the flexible assignment problem, formulated as a nondeterministic polynomial-time hard problem, the system relies on an embedded Ising machine based on a quantum-inspired algorithm called simulated bifurcation. Using a vehicle-mountable computing platform, we demonstrate real-time system-wide throughput of more than 20 frames per second with the enhanced functionality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

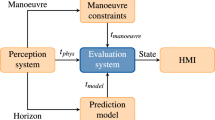

Autonomous control in mobile vehicles, for advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and toward fully automated driving, as well as in mobile robots is achieved through high-speed real-time systems that periodically execute a task pipeline comprising sensing, understanding, planning, and control1,2,3. Understanding the surrounding environment and ego motion involves advanced information processing, including object detection and tracking4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, as well as localization and mapping12. These processes must be performed efficiently on vehicle-mountable computing platforms13,14,15, which are constrained by size, power consumption, and cost.

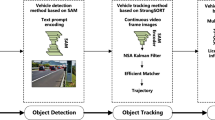

Multiple object tracking (MOT) is a cognitive process that identifies and maintains awareness of multiple objects despite their movement, even through temporary occlusion events such as object crossings. Modern MOT systems4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 use a tracking-by-detection strategy, in which the objects that have been identified and continuously followed by the system (hereafter, tracks) are associated with the objects detected in the current video frame (hereafter, detections) and then updated using the information from the matched detections (see Fig. 1). The tracks thus draw the trajectories of the objects. The assignment (matching) between tracks and detections is determined based on a similarity (or association) matrix, where each matrix element corresponds to the similarity between a track and a detection. Various sophisticated definitions of similarity have recently been proposed based on advanced machine learning methodologies4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. The assignment problem, which aims to maximize the overall likelihood and ultimately determines the temporal association of objects, is a combinatorial (or discrete) optimization problem, more specifically, a bipartite graph matching problem. The assignment problems in those MOT systems4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 that assume one-to-one correspondence between tracks and detections are linear (i.e., they are linear assignment problems) and can therefore be solved in polynomial time using an exact algorithm known as the Hungarian algorithm16. However, during periods of object crossing (occlusion), a many-to-one correspondence (i.e., many tracks to one detection) may be more plausible. Assignment problems that consider the possibility of many-to-one correspondence are more complex combinatorial optimization problems and are difficult to solve on conventional von Neumann computers.

The system relies on the embedded Ising machine to solve a flexible assignment problem formulated as an NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem. The left-side images were generated using CARLA simulator (MIT License) and assets (CC-BY License)64.

Following the introduction of D-wave’s quantum annealer in 201117, domain-specific computers designed to solve difficult combinatorial optimization problems in a short time17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, known as Ising machines, have attracted attention for their potential to substantially accelerate the solution of such problems. The Ising machines aim to find the lowest-energy states of Ising spin models44, which consist of binary variables (called spins) coupled through pairwise interactions. The Ising problem, which is equivalent to quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO), belongs to the class of the nondeterministic polynomial-time hard (NP-hard) problems45,46. A wide range of computationally hard combinatorial problems can be formulated as the Ising problems46. The Ising machines have been implemented using a variety of hardware platforms18 including superconducting qubits17,26, optical systems27,28,29, memristor-based neural networks30, probabilistic bits31,32, spintronics systems33, coupled oscillators19,34,35,36,37, analog computing units38, application specific integrated circuits (ASICs)39,40, field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs)19,20,21,22,24,25,41,43, and graphics processing units (GPUs)19,21,42.

Vehicle-mountable computing platforms for autonomous control13,14,15 must be equipped with parallel and programmable coprocessors, such as embedded FPGAs, GPUs, neural processing unit (NPUs), to efficiently execute diverse and computationally intensive workloads. Among various types of Ising machines, some19,20,21,22,41,42,43 are based on highly parallelizable algorithms that are not limited to specialized hardware and do not require special equipment such as lasers or dilution refrigerators, and thus can potentially be implemented and accelerated with vehicle-mountable parallel coprocessors. These embeddable Ising machines may enable more rational judgments and functional information processing based on NP-hard combinatorial optimization for automated control. Some studies47,48,49,50 have investigated the applicability of quantum mechanics-based Ising machines (quantum annealers) to assignment problems in MOT under the assumption of one-to-one correspondence. Other studies have reported centralized (out-of-vehicle) systems using quantum annealers for traffic flow optimization51 or swarm robot control52. High-speed financial trading systems using Ising machines have also been demonstrated53,54,55. However, vehicle-mountable systems using Ising machines for autonomous control have not yet been studied or demonstrated.

To demonstrate the potential and feasibility of enhancing vehicle-mountable control systems using emerging Ising machines, we propose and implement a real-time MOT system featuring an enhanced temporal association mechanism, called the flexible assignment function, which is based on NP-hard combinatorial optimization and enabled by an embedded Ising machine.

With this flexible assignment mechanism, the proposed system enables robust object tracking through multiple long-term occlusion events. The assignment problem between detections and tracks is formulated as a QUBO problem, whose total cost function is a linear combination of an objective function that maximizes overall likelihood and a penalty function corresponding to the constraint for one-to-one correspondence. The system solves the QUBO problem twice per video frame while changing the weight coefficient for the penalty function (i.e., adjusting the strictness for one-to-one correspondence) and then detects the occlusion events and their locations as the difference between the two solutions (i.e., the two assignment tables), where an assignment table with many tracks being matched to one detection (a constraint-violation solution) may be selected if it is more plausible in terms of the total cost function upon the execution with the small weight coefficient. The QUBO formulation for the flexible assignment is related to but distinct from the time-series assignment QUBO recently proposed in ref. 49. The difference between them is discussed.

The system employs an embeddable Ising machine based on a quantum-inspired algorithm known as simulated bifurcation (SB)19,20,21,22,23,24,25, which enables solving the QUBO twice per video frame while maintaining real-time throughput. The SB algorithm was originally derived in 201919 by classicizing a quantum-mechanical Hamiltonian describing a quantum adiabatic optimization method56 and was further improved in 202121. It numerically simulates the time evolution of a classical nonlinear oscillator network exhibiting bifurcation phenomena, where the two branches of bifurcation in each oscillator correspond to the two states of an Ising spin. The operational mechanism of SB, which consistently finds better solutions with higher probability, is based on an adiabatic and ergodic search19. The MOT system is implemented using two vehicle-mountable, mid-range FPGAs: one is for object detection and the other for the assignment by the SB-based Ising machine. We demonstrate a real-time system-wide throughput exceeding 20 frames per second along with the Ising machine-enhanced MOT functionality. To evaluate the tracking capability through long-term and complex occlusion events, a systematic set of benchmark sequences has been prepared and is provided as the Supplementary Movies and Data.

Results

Figure 1 presents the block diagram of the proposed real-time, vehicle-mountable MOT system incorporating an SB-based embedded Ising machine. The system manages a set of tracks, which are objects currently being identified and followed, and updates them frame by frame using detections, which are the objects detected in the current video frame. The correspondence between tracks and detections is determined by solving a flexible assignment problem, which is central to this work and is formulated as a QUBO problem. The MOT system is implemented on a vehicle-mountable computing platform designed to meet constraints on size, power, and cost. It achieves real-time processing speeds and demonstrates improved tracking performance compared with a baseline system that solves a conventional linear assignment problem. The following subsections describe, in order, the QUBO formulation of the flexible assignment function, the enhanced MOT algorithm, the system architecture and implementation, the experimental demonstration, and a comparison with an alternative QUBO-based assignment method.

Flexible assignment

A similarity matrix S (also referred to as an association matrix in other literature) is defined as a measure of distance in real and/or feature spaces for all pairs (t, d) between tracks and detections, with each matrix element St,d being a real number. Based on the similarity matrix, an assignment function subject to the constraint for one-to-one correspondence determines an assignment table, where each element bt,d is a binary decision variable indicating either match or unmatch. The proposed flexible assignment function (Fig. 2), which uses two binary assignment tables, introduces a third state, potentially-match, to represent a track being matched with an occluded object (i.e., a hidden detection). The state of potentially-match is utilized to more accurately estimate the dynamics of tracks, as discussed in the next subsection.

a Submodules in the assignor. The assignment result between tracks and detections considering the possibility of many-to-one correspondence is determined from two assignment tables. These tables are generated by the Ising machine, which solves the similarity matrix-based assignment problem twice per frame while changing the weight coefficient λ for the penalty function corresponding to the constraint for one-to-one correspondence. b The solution space of the decision variables, including both constraint-violating and constraint-satisfying solutions. c A scene without occlusion and the corresponding similarity matrix, with the resultant assignment tables (d, e). f A scene with occlusion and the corresponding similarity matrix, with the resultant assignment tables (g, h).

The flexible assignment function enables the detection of occlusion events and their locations. In this subsection, we explain the QUBO formulation of the flexible assignment problem step by step. For details on the QUBO/Ising formulation and their conversion, refer to the Methods section. We begin with the formulation of the linear assignment problem (i.e., a bipartite graph matching problem) under the assumption of one-to-one correspondence. Given Nt tracks and Nd detections in a video frame, we define NtNd binary variables, {bt,d}, each representing whether tth track is matched with dth detection:

As a combinatorial optimization problem, we search for a bit configuration {bt,d} (i.e., an assignment table) that minimizes the objective function Hobject, which corresponds to maximizing the overall likelihood:

subject to the linear equality constraints enforcing one-to-one correspondence:

where we assume Nd = Nt.

The assignment problem described in Eqs. (2) and (3) is a constrained binary optimization problem. To convert it into an unconstrained form (QUBO), we apply the penalty method described in the Methods section. This approach minimizes the total cost function Hcost, which is a linear combination of the objective function Hobject and a penalty function Hpenalty corresponding to the constraints for one-to-one correspondence:

Here, λ is a weight coefficient for the penalty function. Hpenalty is minimized to zero when the constraints of Eq. (3) are satisfied (i.e., each column and row of the assignment table contains exactly one non-zero element). If constraint violations occur, Hpenalty increases. However, Hcost may still decrease if the reduction in Hobject outweighs the increase in Hpenalty. To ensure equivalence between the constrained and unconstrained formulations, Hcost must always increase when a constraint violation occurs, compared with a constraint-satisfying and Hobject-minimum bit configuration (i.e., an exact solution). The bit configuration shown in Fig. 2e satisfies the constraints and can therefore be considered an example of an exact solution. When a bit flips from zero to one in such a configuration, the resulting change in Hcost is given by ( − St,d + 2λ). This expression defines the critical condition for determining an appropriate value of λ. Since the similarity score St,d is a relative measure, it can generally be normalized to the range [0, 1]. In this work, we use the Intersection over Union (IOU), denoted as IOU(t, d)4, as the similarity measure St,d (also see the next subsection), which by definition lies within [0, 1]. Therefore, the lower bound for the weight coefficient is λ > 1/2.

In the flexible assignment function, we first extend the penalty function to accommodate one-to-zero and zero-to-one correspondences when Nd ≠ Nt. In the case where Nt > Nd, tracks without corresponding detections (i.e., one-to-zero correspondence) are permitted. This situation typically arises when there are candidate tracks to be deleted, such as objects exiting the frame (i.e., frame-out objects). Conversely, when Nt < Nd, detections without corresponding tracks (i.e., zero-to-one correspondence) are allowed. This typically occurs when there are candidates for additional tracks (e.g., frame-in objects). However, any double coincidences (i.e., many-to-one correspondence) are treated as constraint violations.

The extended cost and penalty functions are defined as follows.

where \({\sum }_{t\ne {t}^{{\prime} }}\) (or \({\sum }_{d\ne {d}^{{\prime} }}\)) represents the summation \({{{\rm{over }}}}_{{N}_{t}}{C}_{2}\) (\({{{\rm{or}}}}_{{N}_{d}}{C}_{2}\)) pairwise combinations of bits in a column (or a row). Here, the constraints corresponding to the penalty function (Hpenalty1 + Hpenalty2) are explicitly expressed by

The penalty function, Hpenalty1 + Hpenalty2, is minimized to zero when the constraints of Eqs. (9) and (10) are satisfied. Suppose the case of Nt > Nd. If \({\sum }_{d=1}^{{N}_{d}}{b}_{t,d}=1\) for tth row in Eq. (10), then \({\sum }_{d\ne {d}^{{\prime} }}{b}_{t,d}{b}_{t,{d}^{{\prime} }}\) for the same row in Eq. (8) is 0 (no penalty) since a non-zero bit is paired with a zero bit in any pairwise combinations. In contrast, if \({\sum }_{d=1}^{{N}_{d}}{b}_{t,d}=2\) (a constraint violation), then \({\sum }_{d\ne {d}^{{\prime} }}{b}_{t,d}{b}_{t,{d}^{{\prime} }}\) in Eq. (8) is 1 (a penalty for many-to-one correspondence) since both bits of one of pairwise combinations are 1.

Let us consider the critical condition for determining λ in Eq. (6). The bit configuration illustrated in Fig. 2h can be regarded as an example of an exact solution when Nt > Nd. Compared to this exact solution, if a bit flips from zero to one, as shown in the example in Fig. 2g, it induces a change of ( − St,d + λ) in Hcost. This represents the minimum possible change in Hcost, and it must be greater than zero. Hence, for the flexible assignment function, the bound condition for the weight coefficient is λ > 1, assuming \({S}_{t,d}^{\max }\)=1. If λ is set to less than 1, a bit configuration that includes double coincidences (i.e., many-to-one correspondences) may be selected, since the bit flip corresponding to such a double coincidence could result in a decrease in Hcost.

To implement the flexible assignment function illustrated in Fig. 2a, we solve the QUBO problem twice per video frame (i.e., per similarity matrix) using two different weight coefficients: a large λ (λlarge) and a small λ (λsmall). These are processed using an Ising machine (a heuristic solver), resulting in two assignment tables. The table generated with λlarge is more likely to satisfy the constraints in Eqs. (9) and (10), whereas the one generated with λsmall is more likely to tolerate many-to-one assignments (i.e., constraint violations). We then arbitrage between the two potentially different tables to produce a final assignment result. First, we determine the state of each track as either match or unmatch based on the table for λlarge. Then, for the unmatched tracks, those that have corresponding detections in the table for λsmall are labeled as potentially-match. In this work, we use 1.0 and 0.1 for λlarge and λsmall, respectively. The value of λlarge is chosen based on the bound condition. Although \({\lambda }_{{{{\rm{large}}}}} > {S}_{t,d}^{\max }\)(=1) is required, we set λlarge = 1.0 because the occurrence of St,d = 1 is rare. This choice is validated through an ablation study for λlarge (see the Methods section). The value of λsmall is similarly determined through an ablation study for λsmall (also detailed in the Methods section).

Figure 2c, f illustrate two successive frames: one showing a scene with one-to-one correspondence between tracks and detections (Nt = Nd), and the other depicting an occlusion event (Nt > Nd) where the object tracked as track ID=5 is occluded by (i.e., not detected due to) the object tracked as track ID=2. For the scene in Fig. 2c, the panels in Fig. 2d, e show the resultant assignment tables for λsmall and λlarge, respectively, in the format of arranging a bit configuration {bt,d} in an Nt × Nd matrix. Fig. 2g, h present the corresponding tables for the scene in Fig. 2f. In each matrix, the sum of bt,d across a row (or a column) indicates the number of matched detections (or tracks) with the track (or the detection) corresponding to the row (or the column).

For the scene in Fig. 2c (without occlusion), the assignment tables in Fig. 2d, e for λsmall and λlarge are identical and satisfy the constraint for one-to-one correspondence (i.e., all the sums of bt,d in rows/columns are 1). In contrast, for the scene in Fig. 2f (with occlusion), the assignment table in Fig. 2h for λlarge satisfies the constraint. Based on this table, track ID = 5 is initially determined to be unmatch by the arbiter (depicted in Fig. 2a). At this stage, two possibilities exist for the object tracked by track ID = 5: either it has exited the scene (frame-out or left behind buildings) or it is temporarily occluded (crossing). The assignment table in Fig. 2g for λsmall, however, violates the constraint, as both tracks ID=5 and ID = 2 are matched with detection ID = 4. Such a solution may be selected by the Ising machine when the reduction in the objective function, due to more matched tracks, outweighs the increase in the penalty function caused by constraint violations. Based on the table in Fig. 2g, the arbiter finally determines the state of track ID = 5 to be potentially-match. Thus, the system detects both the occurrence and the location of an occlusion event.

Figure 2b illustrates the solution space of the decision variables (i.e., all the possible bit configurations) including both constraint-satisfying and constraint-violating solutions. Assuming Nt = Nd ( = No) for simplicity, the size of the solution space is \({2}^{{N}_{o}^{2}}\), while the number of solutions that satisfy the one-to-one correspondence constraint is No!, which constitutes only a small fraction of the total space. The bit configurations shown in Fig. 2d, e, h belong to the constraint-satisfying subset, whereas the configuration in Fig. 2g belongs to the constraint-violating subset. The linear assignment algorithm (e.g., the Hungarian algorithm) searches exclusively within the subset of constraint-satisfying solutions. In contrast, the Ising machine explores the entire solution space, including configurations that violate constraints. This broader search capability is essential for identifying plausible many-to-one assignments. It is crucial to evaluate the degree of constraint violation using the penalty functions (the quadratic functions), represented by the quadratic terms in Eqs. (7) and (8), rather than binary judgments imposed by the equality constraints (Eqs. (9) and (10)).

Multiple object tracking

Many modern MOT systems4,5,6,7,8,9,10 rely on the Kalman filter framework57 to estimate the motion dynamics of tracks. In this framework, the states of tracks are first predicted based on a motion model at each frame and then corrected (updated) using the information from matched detections (i.e., measurement results) at that frame (see also Fig. 1 and Fig. 2a). This approach enables more accurate motion estimation by incorporating a series of measurements observed over time rather than relying on a single measurement, which may be affected by statistical noise or other inaccuracies.

Figures 1 and 2a show the block diagram of the MOT system, which consists of a camera, a detector, a predictor, a corrector, an associator, and an assignor. The pseudocode in Algorithm 1 (see the Methods section) outlines the information processing procedure within the system. In this work, we adopt the Simple Online and Real-time Tracking (SORT) system4 as a baseline because it is a representative example of modern MOT systems and is simple to implement on vehicle-mountable computing resources. We then modify it in two key aspects: First, we replace the assignment function in the assignor. Instead of using the linear assignment method that assumes one-to-one correspondence (i.e., the Hungarian algorithm), we introduce the flexible assignment method using an Ising machine and an arbiter (see Fig. 2a). Second, we modify the procedure in the corrector to incorporate the newly introduced potentially-match state, which enables robust tracking through occlusion events.

The status data of ith track include a vector Ti:

where ri represents the location and size of the bounding box for the track, \({\dot {{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}\) is the time derivative of ri, and agei is the age of the track, defined as the number of frames (i.e., the time) elapsed since it last acquired a matched detection. At the beginning of the procedure for each frame (see Algorithm 1), the statuses of tracks are predicted by approximating the inter-frame displacements of objects, and the age of all tracks are incremented by one. At the end of the procedure, tracks whose age exceeds a predetermined lifetime, max_age, are deleted. The processing for each track in the corrector depends on the assignment result (match, potentially_match, or unmatch) determined by the assignor. The assignor determines the assignment result based on the predicted tracks and the detections obtained at the current frame. A matched track is updated using the corresponding detection (based on the Kalman filter theory), and its age is reset to zero. A potentially-matched track is not updated (its predicted status is retained for the next frame), but its age is decreased by a predetermined constant, anti_aging. An unmatched track is left unchanged and is deleted if its age exceeds max_age. Additionally, a new track is appended for each unmatched detection (if exists). In this work, both max_age and anti_aging are set to 5.

Once a track is determined to be in the potentially_match state, it is not deleted for at least subsequent anti_aging frames. Furthermore, if it is again classified as potentially_match again during the period, its age is further decreased by anti_aging (allowing the age to become negative). This mechanism enables the track to re-establish correspondence with a detection after an occlusion event, which typically lasts for several frames. These special treatments are applied only to specific tracks, namely, those in the potentially-match state. In contrast, tracking through occlusion could also be achieved by simply increasing max_age without introducing the potentially_match state. However, this approach has significant drawbacks. In such cases, tracks corresponding to objects that should be deleted (e.g., frame-out objects or those left behind buildings) may persist for a long period. This leads to unnecessary computational overhead in managing an inflated number of tracks within the Kalman filter framework and increases the risk of erroneous match between those unfavorable tracks and detections. For a quantitative verification of this discussion, see the ablation study for max_age in the Supplementary Information 1.

System architecture

To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed MOT system under constraints of size, power, and cost for vehicle-mountable computing platforms, we prototyped the system on two vehicle-mountable computing boards. Each board is equipped with an embedded FPGA (serving as a parallel and programmable coprocessor) and a general-purpose microprocessor unit (MPU). Figure 3 shows the hardware configuration of the system and indicates where the modules depicted in Figs. 1 and 2a are implemented. Among these modules, the computationally intensive components are the Ising machine and detector, which are hardwired (i.e., implemented as custom circuits) on the two FPGAs to ensure efficient processing in terms of speed and power. The remaining modules are implemented as software objects and executed on the MPUs.

a Photograph of the system showing a camera and two computing boards, each equipped with a monolithic MPU-FPGA chip (MPU microprocessor unit; FPGA field programmable gate array). b Hardware configuration and block diagram of the modules implemented on the platform. c Placement of the modules within the monolithic MPU-FPGA chip for the assignor. The custom circuit for simulated bifurcation, serving as an embedded Ising machine, is highlighted in red within the FPGA fabric.

The Ising machine used in this work supports a 512-spin configuration with all-to-all spin-spin connectivity, allowing real numbers (32-bit precision) to be set in any coupling coefficients (Ji,j). The QUBO problem (with decision variables, bi ∈ {0, 1}) defined by Eqs. (1) and (6) is represented as an Ising problem (with decision variables, si ∈ { − 1, 1}) and then solved using the Ising machine. See the Methods section for details on the one-to-one correspondence between QUBO and Ising formulations. The current implementation supports up to 22 tracks (Nt=22, Nd=22, NtNd=484).

SB is a highly parallelizable metaheuristic algorithm for solving discrete optimization problems. For N-spin Ising problems with full connectivity, the maximum numbers of parallelizable operations in SB and simulated annealing (SA, a conventional metaheuristic)58,59 are, respectively, N2 and N20,22. Custom-circuit implementations of SB20,22,24 on modern FPGAs with island-style architectures60 have demonstrated a degree of computational parallelism exceeding the problem size N. Among the various SB variants, we adopt the ballistic SB algorithm21 in this work, as it is well-suited for single-shot processing necessary for high-speed real-time systems53,54,55. See the Methods section for further details on SB.

Using a scalable design of the accelerator for ballistic SB, written in a high-level synthesis language and based on circuit architectures similar to those in Refs. 20,61, we built the embedded 512-spin SB-based Ising machine shown in Fig. 3c. It features 2048 parallel processing elements (PEs). These 2048 PEs compute 2048 pair interactions simultaneously in a single clock cycle. These interactions are part of total 512 × 512 interactions to be calculated per SB time step (corresponding to the term of \({\sum }_{j}^{N}{J}_{i,j}{x}_{j}\) in Eq. (20)). The degree of computational parallelism was chosen based on estimated cost constraints for commercial vehicle applications: the number of logic elements was kept below 250 K, and the number of 32-bit digital signal processor (DSP) units below 400. When Nstep, an operational parameter for SB, is 400 (the case for this work), the time required to obtain a solution with the SB-based Ising machine is 284 μs. Since the QUBO problem is solved twice per frame (see Flexible assignment subsection), the total computation time per frame is 568 μs. The operating power of the Ising machine during real-time operation of the MOT system was measured to be 3.4 W. See the Methods section for further details on the implementation of the MOT system.

Demonstration

The proposed MOT system, equipped with an embedded Ising machine and implemented on vehicle-mountable computing boards, demonstrates real-time processing speed and enhanced tracking capability through NP-hard (quadratic) combinatorial optimization, in contrast to the baseline system that relies on linear combinatorial optimization (i.e., the original SORT4). In addition to standard benchmark sequences from the MOT challenges62,63, we have prepared a systematic set of benchmark sequences designed to evaluate tracking performance under long-term and complex occlusion events. These sequences were generated using CARLA simulator (MIT License) and assets (CC-BY License)64, which are provided as the Supplementary Data 1.

We first demonstrate that the proposed system achieves real-time processing speed, with the calculation time of the embedded Ising machine being minor compared to the overall processing time. Figure 4a shows a histogram of the computation times for the modules in the MOT system when processing a benchmark video sequence (600 frames), titled “MOT17-02-FRCNN”62,63. Figure 4b illustrates the tracks as colored bounding boxes in a scene extracted from the same sequence. The inset in Fig. 4a presents a timing chart of the MOT system. In this chart, the operation of the detector (Tdetector) is overlapped with that of the other tracking modules (Ttracking) including the assignor (Tassignor). The processing time per frame is determined by \(\max \{{T}_{{{{\rm{detector}}}}},{T}_{{{{\rm{tracking}}}}}\}\), which is 44.2 ms on average, corresponding to a processing speed of 23 frames per second. The computation time of the embedded Ising machine (TIsing_machine) is deterministic (568 μs) and minor compared to (or not affecting) the overall processing time. Note that Tassignor is measured by the MPU on the left board in Fig. 3, and includes the time for inter-board communication as well as the computation times for the preprocessor and the arbiter. See the Methods section for further details on system-wide throughput. The detector receives video frames either from onboard memory or directly from the camera. See the Supplementary Movie 1 for a demonstration of real-time operation using live camera input. The authors affirm that all participants appearing in the Supplementary Movie 1 have provided informed consent for the publication of the images.

a Histogram of the computation times for the modules in the MOT system when processing an MOT benchmark sequence (600 frames) titled “MOT17-02-FRCNN”62,63 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 License). The inset shows a timing chart illustrating the overlapping operation of the detector and the other tracking modules. b A scene from “MOT17-02-FRCNN” with tracks indicated as bounding boxes. Facial regions have been blurred to protect privacy. c, d, e Five-object tracking through a complex occlusion event involving simultaneous occurrences of three-object crossing and two-object crossing, where the scenes in (c, d, e) show, respectively, the frames #50, #80, and #110 extracted from a sequence (142 frames) provided as the Supplementary Movie 2. The movie was generated using CARLA simulator (MIT License) and assets (CC-BY License)64. The bounding boxes indicate tracks. f, g, h Similarity matrices corresponding to c, d, e, with red and blue boxes indicating the assignment results between tracks and detections.

The proposed MOT system enables robust tracking through long-term and complex occlusion events, a capability that cannot be achieved with the baseline system. To demonstrate this, we designed a custom video sequence (the Supplementary Movie 2) featuring simultaneous occurrences of three-object and two-object crossings. Here, the three-object crossing is involved in the long-term two-object occlusion event, where two objects move in the same direction, and one overtakes the other at a small relative speed. The proposed system correctly tracks the five objects through those occlusion events, while the baseline fails to track. A comparative video showing the tracking results of both systems is provided in the Supplementary Movie 2. Figure 4c–e show three scenes before, during, and after the complex occlusion event. During the simultaneous occurrences of three-object and two-object crossings, the states of tracks ID=0, 1, 4 are potentially-match as shown in Fig. 4g. The proposed system is capable of tracking through even more complex occlusion events. The Supplementary Movie 3 provides an example with simultaneous occurrences in four locations of five-object crossings.

To quantitatively evaluate the enhancement in tracking performance of the proposed MOT system, we compare it to the baseline using a common parameter of max_age (=5), across a series of benchmark sequences that are assessed using an MOT evaluation metric called HOTA (higher order tracking accuracy)65,66. HOTA is a unified and balanced metric comprising three sub-metrics: AssA (association accuracy), DetA (detection accuracy), and LocA (localization accuracy). While many recent MOT papers use the MOT challenges datasets4,5,6,7,9,10,11,49, these benchmark sequences are not specifically designed to evaluate various occlusion scenarios, and the occurrence of occlusion events is moderate. Therefore, we designed nine benchmark sequences that include complex crossing events (provided with ground truth data in the Supplementary Data 1) to evaluate tracking performance under long-term and complex occlusion conditions, where the frequency of occlusion events is systematically varied. See the Methods section for details on the benchmark sequences.

Table 1 summarizes the measured results for seven benchmark sequences, MOT17-{02, 04, 05, 09, 10, 11, 13}-FRCNN, from the MOT challenges, and the nine benchmark sequences for crossing, Cross-{DLVL, DLVM, DLVH, DMVL, DMVM, DMVH, DHVL, DHVM, DHVH}, where the numbers (percentages) in parentheses indicate the relative improvements over the baseline. Movies comparing the tracking and assignment results between the proposed MOT system and the baseline, when processing the Cross benchmark sequences, are provided as Supplementary Movies 4 to 12. The overall HOTA score is improved for the proposed MOT system, primarily due to enhancements in AssA achieved through the flexible assignment function, rather than improvements in detection and localization accuracies (DetA and LocA). The improvements in HOTA for the proposed MOT system tend to be more significant for benchmark sequences that include a higher number of occlusion events. See the ablation studies in the Methods section and Supplementary Information 1 for further details on comparison between the proposed system and baseline.

QUBO-based assignment

The flexible assignment function proposed in this work is realized by solving the QUBO problem defined with Eqs. (6) to (8). While many MOT systems4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,50 rely on linear assignment, Zaech et al. recently introduced a QUBO-based (quadratic) assignment for MOT49, which is theoretically grounded in Refs. 47,48. Below, we describe how Zaech’s QUBO differs from ours.

Unlike our QUBO, which is intended for online (or real-time) processing, Zaech’s QUBO is designed for offline (or batch) processing. Specifically, our MOT system updates tracks frame by frame, while Zaech’s MOT system determines plausible assignments between tracks and detections over a time span (for a batch of frames). Hereafter, our QUBO and Zaech’s QUBO are referred to as the flexible assignment QUBO and the time-series assignment QUBO, respectively.

For the time-series assignment QUBO, we prepare F assignment tables, each consisting of NtNd binary variables, where F is the batch size (i.e., the number of frames in a batch), and Nt and Nd are the numbers of tracks and detections, respectively. Thus, the QUBO involves a total of FNtNd binary variables.

Similarity is defined for pairs of detections across different frames, and the objective function includes a quadratic term of the form \({S}_{{d}_{i},{d}_{j}}{b}_{t,{d}_{i}}{b}_{t,{d}_{j}}\), where i and j are frame indices, \({S}_{{d}_{i},{d}_{j}}\) represents the similarity between detections di and dj, and \({b}_{t,{d}_{i}}\) is a binary variable defined as:

The quadratic term represents a gain when dith detection at ith frame and djth detection at jth frame are assigned to the same tth track (i.e., when \({b}_{t,{d}_{i}}{b}_{t,{d}_{j}}=1\)). By solving the QUBO under the constraint of one-to-one correspondence within each frame, we can simultaneously determine the F assignment tables, thereby constructing the trajectories over time.

In the flexible assignment QUBO, the quadratic terms for pairwise combinations of binary variables (Eqs. (7) and (8)) are evaluated to quantify the degree of constraint violations related to one-to-one correspondence, thereby enabling plausible many-to-one assignments. To further enhance tracking accuracy, it may be possible to incorporate the quadratic term from the time-series assignment QUBO into the objective function of the flexible assignment QUBO (Eq. (2)). This integration is left for future work.

Discussion

We have demonstrated a vehicle-mountable MOT system equipped with a flexible assignment function that enables tracking through long-term and complex occlusion events, such as simultaneous multiple occurrences of many-object crossing. The proposed flexible assignment framework considers both the possibilities of many-to-one correspondence and one-to-one correspondence between tracks and detections, and enables detection of occlusion events and their locations. This functionality is formulated as a QUBO problem and realized by solving the QUBO twice per frame while adjusting the strictness of one-to-one correspondence. To solve the QUBO in real time under constraints of size, power, and cost, the prototype system employs an SB-based embeddable Ising machine. The enhanced tracking capability, compared to the baseline method using linear assignment, has been validated using both standard benchmark sequences and custom-designed sequences tailored for complex crossing scenarios. The flexible assignment QUBO proposed in this work is also compared with a recently introduced time-series assignment QUBO49, particularly in terms of the role and formulation of quadratic terms. The methodology presented in this study paves the way for advancing assignment functionality beyond traditional linear assignment approaches, toward those requiring computationally hard (NP-hard) combinatorial optimization.

There are three possible directions for future work. First, the flexible assignment function could be enhanced by incorporating more advanced similarity definitions, such as distances in feature space5,6,7,8,9,10,11 or unified measures derived from multimodal sensor information67. Second, the methodology of flexible assignment could be extended to a quadratic object function of the form, \({H}_{{{{\rm{object}}}}}\,=\,-{\sum }_{(t,d)}{\sum }_{({t}^{{\prime} },{d}^{{\prime} })}{S}_{t,d,{t}^{{\prime} },{d}^{{\prime} }}{b}_{t,d}{b}_{{t}^{{\prime} },{d}^{{\prime} }}\), where \({S}_{t,d,{t}^{{\prime} }\ne t,{d}^{{\prime} }\ne d}\) represents a bonus or penalty for the simultaneous matching of two pairs of (t, d) and (\({t}^{{\prime} }\), \({d}^{{\prime} }\)), corresponding to conditional likelihoods or tradeoff relationships. Note that in the QUBO formulation of this work, the penalty functions (Eqs. (7) and (8)) are quadratic, while the object function (Eq. (2)) is linear. Third, the concept of a vehicle-mountable computing platform with embedded Ising machines could be applicable to various tasks other than MOT, such as simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM)12, scheduling, or path planning.

Methods

QUBO and Ising problems

The QUBO and Ising problems are mathematically equivalent and classified as nondeterministic polynomial-time hard (NP-hard) problems45,46. Many NP-hard and NP-complete problems, including all of Karp’s 21 NP-complete problems, can be formulated as QUBO or Ising problems46.

The N-variable QUBO problem is to find a bit configuration (from among 2N candidates) that minimizes the cost function:

where bi ( ∈ {0, 1}) denotes ith bit, b = (b1, ⋯ , bN) is the vector representation of a bit configuration, Qij( = Qji) is a quadratic coefficient for ith and jth bits, Q is the matrix representation of {Qij}. Since \({b}_{i}^{2}={b}_{i}\), the diagonal elements Qii represent linear coefficients for bi.

The N-variable Ising problem is to find a spin configuration that minimizes the Ising energy45:

where si ( ∈ { − 1, 1}) is ith Ising spin, s = (s1, ⋯ , sN) is the vector representation of a spin configuration, Jij( = Jji) is a coupling coefficient between ith and jth spins (Jii = 0), J is the matrix representation of {Jij}, and hi is a bias (or linear) coefficient for ith spin, and h is the vector representation of {hi}.

The QUBO problem in the form of Eq. (13) can be written as an equivalent Ising problem in the form of Eq. (14) using the following relations:

Penalty method

To solve constrained binary minimization problems using (unconstrained) QUBO (or Ising) solvers, a penalty method46,47,49 is often employed. This method reformulates a constrained problem as an unconstrained one, with the solution ideally converging to that of the original constrained problem. The unconstrained problem is created by adding a term called a penalty function to the original objective function.

A quadratic bit minimization problem with linear equality constraints (Gb = d) is generally expressed as:

where G and d are the coefficient matrix and constraint vector, respectively. This constrained problem is transformed into the following unconstrained problem:

where the second term, \(\parallel G{{{\bf{b}}}}-{{{\bf{d}}}}{\parallel }_{F}^{2}\), serves as the penalty function. Here, λ is a weight coefficient (a positive constant) for the penalty function, and the Frobenius norm is defined as \(\parallel A{\parallel }_{F}=\sqrt{{\sum }_{i,j}{A}_{ij}^{2}}\) (i.e., \(\parallel A{\parallel }_{F}^{2}={\sum }_{i,j}{A}_{ij}^{2}\)). The penalty function is minimized to zero if the equality constraints are satisfied (i.e., if Gb = d); otherwise, it increases quadratically depending on the degree of constraint violation. The expression of Eq. (19) is quadratic and unconstrained (it can be reformulated in the form of Eq. (13)), and thus can be solved using QUBO (/Ising) solvers.

The penalty weight λ is an important hyper-parameter that must be appropriately determined depending on the problem. To ensure the constraints are satisfied, λ needs to be large. However, an excessively large λ creates a steep energy landscape (HQUBO/Ising), which potentially destabilizes the dynamics within Ising solvers. Therefore, in practice, λ should be as small as possible while still ensuring equivalence between Eqs. (18) and (19).

Simulated bifurcation

SB19,21 is a quantum-inspired19,68, highly parallelizable20,22,24, metaheuristic algorithm for computationally hard combinatorial (or discrete) optimization. SB-based Ising machines belong to a class of oscillator-based Ising machines27,28,29,34,35,36,37,43. The SB algorithm finds optimal (exact) or near-optimal solutions to the Ising problem by simulating the time-evolution of coupled nonlinear oscillators according to Hamilton’s equations of motion (without energy-dissipative or noise-based mechanisms). Several variants of SB exist, including adiabatic SB, ballistic SB, and discrete SB, which differ in nonlinearity69 and discreteness21.

In the SB algorithm, the ith nonlinear oscillator corresponds to the ith Ising spin and its state is described by its position and momentum (xi, yi). The update procedure for xi and yi in the ballistic SB, used in this work, is as follows21:

where a0, c0 and η are positive constants, \({a}^{{t}_{k}}\) is a control parameter increasing from zero to a0, and \({{{\rm{sgn}}}}(x)\) (equal to ± 1) is the sign function. Eq. (22) represents a nonlinear transfer function69, which physically corresponds to a perfectly inelastic wall at x = ± 1. The time increment is denoted as Δt, such that tk+1 = tk + Δt. After iterating this update procedure for a predetermined number of time steps (Nstep), the final ith position xi is binarized to yield the ith spin ( ± 1) by taking the sign of xi. In this work, a0=1, c0 = η = 0.8, Δt = 0.3, and Nstep = 400.

The ballistic SB algorithm has been demonstrated to produce higher-quality solutions more efficiently than the simulated annealing (SA) algorithm, for both academic benchmark problems21 and practical applications25,53,54,55,61.

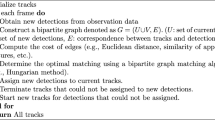

Algorithm 1

MOT with the flexible assignment

MOT algorithm

Algorithm 1 outlines the processing step in the MOT system with flexible assignment, comprising the following components: camera, detector, predictor, corrector, associator, and assignor, as illustrated in the block diagrams in Figs. 1 and 2a.

The detector detects objects of the “car” or “person” classes in each frame using a real-time object detection algorithm, YOLO70,71 and outputs the corresponding detections (including the bounding boxes for detected objects). Similar to SORT4, the predictor is based on a linear constant velocity model, and the associator uses the Intersection over Union, IOU(t, d), of the bounding boxes for tth track and dth detection as the similarity measure St,d. The assignor and corrector are described in detail in the Main text.

Implementation

To implement the proposed MOT system, we used two vehicle-mountable SoC (System-on-a-Chip)-FPGA boards, each equipped with a monolithic MPU-FPGA chip.

The first board is the Intel Arria 10 SX SoC Development Kit (DK-SOC-10AS066S-D), featuring a 10AS066N3F40E2SG1 monolithic chip that integrates a dual-core ARM Cortex-A9 MPCore processor and an embedded FPGA. The FPGA (660K logic elements, 4-input LUT equivalent) has 251,680 adaptive logic modules (ALMs) including 251,680 adaptive lookup tables (ALUTs, 6-input LUT equivalent) and 1,006,720 flip-flop registers, 2131 20Kbit-size RAM blocks (BRAMs)72, and 3374 18-bit × 19-bit multipliers (DSPs).

The SB-based Ising machine was implemented with this FPGA using a high-level synthesis (HLS) language (Intel FPGA SDK for OpenCL, ver. 18.1). Table 2 summarizes the architecture and the implementation results. The system clock frequency (Fsys) after synthesis, placement, and routing is 254 MHz. The operating power of the Ising machine is 3.4 W, as measured by PowerMonitor tool that uses the onboard MAX V CPLD to monitor current on the FPGA power rails. Software components executed on the MPU were written in C/C++ programming language and ran on the Angstrom Linux OS (v2014.12).

The second board is the AMD Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC (ZCU104), which features a XCZU7EV-2FFVC1156 monolithic chip including a quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 MPCore processor and an embedded FPGA. The FPGA (504K logic cells, 4-input LUT equivalent) has 28,800 configurable logic blocks (CLBs) including 230,400 adaptive lookup tables (ALUTs, 6-input LUT equivalent) and 460,800 flip-flop registers, 312 36Kbit-size RAM blocks (BRAMs)/96 288Kbit-size RAM blocks (UltraRAMs), and 1728 27-bit × 18-bit multipliers (DSPs).

The detector was implemented on this FPGA as a custom circuit for YOLOv271, yolov2_voc_pruned_0_77, provided by Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. Software components for the MPU were written in Python (version 3.8) and executed on Ubuntu Linux OS (20.04.5/6 LTS).

Both boards are equipped with Ethernet Media Access Controllers (EMACs) and are interconnected via a 1 Gbps Ethernet cable using the UDP protocol.

Benchmark sequences for crossing

Table 3 lists nine benchmark sequences designed to evaluate crossing scenarios. Each sequence is characterized by the number of frames (#frames), the maximum and average number of objects (#objects), the average object velocity (in meters per second, assuming 20 FPS), and the average occlusion ratio. In the ground truth data, objects are labeled as either visible or invisible (occluded). The occlusion ratio for a given frame is defined as (number of objects - number of visible objects) / (number of objects).

Ablation study for λ large and λ small

The two weight coefficients, λlarge and λsmall, are important hyper-parameters in the proposed MOT system. Figure 5a, b show the variation in the overall HOTA score (MOT17+Cross) when (a) both λlarge and λsmall are varied together and when (b) λsmall is varied while keeping λlarge = 1.0, respectively.

a Averaged HOTA score over 16 benchmark sequence listed in Table 1 when varying λlarge ( = λsmall). b Averaged HOTA score when varying λsmall with a fixed λlarge of 1.0.

The value of λlarge was set to 1.0 based on the bound condition described in the Main text. When increasing λlarge ( = λsmall) toward 1.0, the overall HOTA score improves and then saturates near λlarge = 1.0, the bound condition. The proposed MOT system with λlarge = λsmall = 1.0 is substantially the same as the baseline (the original SORT4). In fact, the overall HOTA scores for the proposed MOT system with λlarge = λsmall = 1.0 and the baseline are 50.24 and 50.21, respectively (both are almost identical).

As shown in Fig. 5b, when decreasing λsmall from 1.0 to 0.0 while keeping λlarge at 1.0, the overall HOTA score increases (indicating enhancement compared to the baseline) and peaks at λsmall = 0.1. Therefore, λsmall was determined to 0.1 in this work. Note that if λsmall is too small ( < 0.1), unnecessary tracks in potentially-match states may be generated, leading to erroneous associations.

System-wide throughput

Table 4 lists measured system-wide throughput when processing the benchmark sequences (Cross+MOT17) with the prototyped vehicle-mountable system shown in Fig. 3. The baseline does not use the right board and runs the linear assignment function (i.e., the Hungarian algorithm) with the MPU on the left board. As stated in the Main text and shown in the inset of Fig. 4a, the processing time of the embedded Ising machine (TIsing_machine) is 568 μs and is not a limiting factor in determining the overall processing time. The overall processing time is mainly determined by the time to manage tracks in the Kalman filter framework, and thus the processing time increases with the number of tracks required (depending on the benchmark sequences). The additional time components observed for the proposed system are due to the inter-board communication time and the computation times of the preprocessor and the arbiter (with the MPU on the right board), which also depend on the number of tracks. To minimize these additional times, all system components should be integrated into a single SoC board. Processing time for MOT17-{04, 10, 11, 13}-FRCNN is unavailable for the proposed system because the required number of tracks exceeds the Ising machine’s size limitation (see System architecture subsection). The accuracy data in Table 1 for these sequences were obtained with a similar but larger (2048-spin configuration) Ising machine61.

Data availability

The authors declare that all relevant data are included in the manuscript and Supplementary Information, Movies, and Data. Additional data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

Extensions introduced in this work, relative to the baseline (SORT4), along with hyper-parameter values, are detailed in the main text using pseudocode and mathematical equations.

References

Yurtsever, E., Lambert, J., Carballo, A. & Takeda, K. A survey of autonomous driving: common practices and emerging technologies. IEEE Access 8, 58443–58469 (2020).

Levinson, J. et al. “Towards fully autonomous driving: systems and algorithms,” Proc. of IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), pp. 163–168, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/IVS.2011.5940562 (IEEE, 2011).

Nakade, T., Fuchs, R., Bleuler, H. & Schiffmann, J. Haptics based multi-level collaborative steering control for automated driving. Commun. Eng. 2, 2 (2023).

Bewley, A., Ge, Z., Ott, L., Ramos, F. & Upcroft, B. “Simple online and realtime tracking,” Proc. of IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), pp. 3464–3468, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2016.7533003 (IEEE, 2016).

Wojke, N., Bewley, A., Paulus, D. “Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric,” Proc. of IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), pp. 3645–3649, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296962 (IEEE, 2017).

Wang, Z., Zheng, L., Liu, Y., Li, Y. & Wang, S. “Towards real-time multi-object tracking,” Proc. of European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), pp. 107–122, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58621-8_7 (ECCV, 2020).

Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Wang, X., Zeng, W. & Liu, W. FairMOT: on the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking. Int. J. Comp. Vis. 129, 3069–3087 (2021).

Du, Y. et al. “GIAOTracker: A comprehensive framework for MCMOT with global information and optimizing strategies in VisDrone 2021,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 2809–2819, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW54120.2021.00315 (IEEE, 2021).

Wang, Z. Do different tracking tasks require different appearance models? Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 726–738 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. “ByteTrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box,” Proc. of European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), pp. 1–21, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20047-2_1 (ECCV, 2022).

Chu, P., Wang, J., You, Q., Ling, H. & Liu, Z. “TransMOT: Spatial-temporal graph transformer for multiple object tracking,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on applications of computer vision (WACV), pp. 4870–4880, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV56688.2023.00485 (WACV, 2023).

Mur-Artal, R. & Tardós, J. D. ORB-SLAM2: an open-source SLAM system for monocular, stereo, and RGB-D cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 33, 1255–1262 (2017).

Su, C.-L., Lai, W.-C. & Te Li, C. “Pedestrian detection system with edge computing integration on embedded vehicle,” Proc. of Int. Conf. on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), pp. 450–453, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAIIC51459.2021.9415262 (ICAIIC, 2021).

Yamada, Y. et al. A 20.5 TOPS multicore SoC with DNN accelerator and image signal processor for automotive applications. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 55, 120–132 (2019).

Fujii, T. et al. “New generation dynamically reconfigurable processor technology for accelerating embedded AI applications,” Proc. of IEEE Symposium on VLSI Circuits (VLSI), pp. 41–42, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/VLSIC.2018.8502438 (IEEE, 2018).

Kuhn, H. W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 2, 83–97 (1955).

Johnson, M. W. et al. Quantum annealing with manufactured spins. Nature 473, 194–198 (2011).

Finocchio, G. et al. Roadmap for unconventional computing with nanotechnology. Nano Futures 8, 012001 (2024).

Goto, H., Tatsumura, K. & Dixon, A. R. Combinatorial optimization by simulating adiabatic bifurcations in nonlinear Hamiltonian systems. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav2372 (2019).

Tatsumura, K., Dixon, A. R. & Goto, H. “FPGA-based simulated bifurcation machine,” Proc. of IEEE International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), pp. 59–66, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/FPL.2019.00019 (IEEE, 2019).

Goto, H. et al. High-performance combinatorial optimization based on classical mechanics. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe7953 (2021).

Tatsumura, K., Yamasaki, M. & Goto, H. Scaling out Ising machines using a multi-chip architecture for simulated bifurcation. Nat. Electron. 4, 208–217 (2021).

Kanao, T. & Goto, H. Simulated bifurcation for higher-order cost functions. Appl. Phys. Express 16, 014501 (2023).

Kashimata, T., Yamasaki, M., Hidaka, R. & Tatsumura, K. Efficient and scalable architecture for multiple-chip implementation of simulated bifurcation machines. IEEE Access 12, 36606–36621 (2024).

Matsumoto, N., Hamakawa, Y., Tatsumura, K. & Kudo, K. Distance-based clustering using QUBO formulations. Sci. Rep. 12, 2669 (2022).

King, A. D. et al. Quantum critical dynamics in a 5000-qubit programmable spin glass. Nature 617, 61–66 (2023).

Honjo, T. et al. 100,000-spin coherent Ising machine. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh0952 (2021).

Kalinin, K. P., Amo, A., Bloch, J. & Berloff, N. G. Polaritonic XY-Ising machine. Nanophotonics 9, 4127–4138 (2020).

Böhm, F., Verschaffelt, G. & Van der Sande, G. A poor man’s coherent Ising machine based on opto-electronic feedback systems for solving optimization problems. Nat. Commun. 10, 3538 (2019).

Cai, F. et al. Power-efficient combinatorial optimization using intrinsic noise in memristor Hopfield neural networks. Nat. Electron. 3, 409–418 (2020).

Borders, W. A. et al. Integer factorization using stochastic magnetic tunnel junctions. Nature 573, 390–393 (2019).

Aadit, N. A. et al. Massively parallel probabilistic computing with sparse Ising machines. Nat. Electron. 5, 460–468 (2022).

Litvinenko, A. et al. A spinwave Ising machine. Commun. Phys. 6, 227 (2023).

Graber, M. & Hofmann, K. An integrated coupled oscillator network to solve optimization problems. Commun. Eng. 3, 116 (2024).

Moy, W. et al. A 1,968-node coupled ring oscillator circuit for combinatorial optimization problem solving. Nat. Electron. 5, 310–317 (2022).

Albertsson, D. I. et al. Ultrafast Ising Machines using spin torque nano-oscillators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 112404 (2021).

Wang, T., Wu, L., Nobel, P. & Roychowdhury, J. Solving combinatorial optimisation problems using oscillator based Ising machines. Nat. Comput. 20, 287–306 (2021).

Sharma, A., Afoakwa, R., Ignjatovic, Z. & Huang, M. “Increasing Ising machine capacity with multi-chip architectures,” Proc. of Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), pp. 508–521, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1145/3470496.3527414 (ISCA, 2022).

Kawamura, K. et al. “Amorphica: 4-replica 512 fully connected spin 336MHz metamorphic annealer with programmable optimization strategy and compressed-spin-transfer multi-chip extension,” Proc. of IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), pp. 42–43, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ISSCC42615.2023.10067504 (IEEE, 2023).

Matsubara, S. et al. “Digital annealer for high-speed solving of combinatorial optimization problems and its applications,” Proc. of Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), pp. 667–672, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ASP-DAC47756.2020.9045100 (ASP-DAC, 2020).

Waidyasooriya, H. M. & Hariyama, M. Highly-parallel FPGA accelerator for simulated quantum annealing. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 9, 2019–2029 (2021).

Okuyama, T., Sonobe, T., Kawarabayashi, K. & Yamaoka, M. Binary optimization by momentum annealing. Phys. Rev. E 100, 012111 (2019).

Leleu, T. et al. Scaling advantage of chaotic amplitude control for high-performance combinatorial optimization. Commun. Phys. 4, 226 (2021).

Brush, S. G. History of the Lenz-Ising model. Rev. Mod. Phys. 39, 883–893 (1967).

Barahona, F. On the computational complexity of Ising spin glass models. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 15, 3241–3253 (1982).

Lucas, A. Ising formulations of many NP problems. Front. Phys. 2, 5:1–5:15 (2014).

Govaers, F., Stooß, V. & Ulmke, M. “Adiabatic quantum computing for solving the multi-target data association problem,” Proc. of IEEE Int’l Conf. on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems (MFI), pp. 1–7, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/MFI52462.2021.9591187 (MFI, 2021).

Birdal, T., Golyanik, V., Theobalt, C. & Guibas, L. J. “Quantum permutation synchronization,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 13122–13133, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01292 (CVPOR, 2021).

Zaech, J.-N., Liniger, A., Danelljan, M., Dai, D. & Van Gool, L. “Adiabatic quantum computing for multi object tracking,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 8811-8822, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00861 (2022).

McCormick, T. M., Osborn, B. P., Angle, R. B. & Streit, R. L. “Implementation of a multiple target tracking filter on an adiabatic quantum computer,” Proc. of IEEE Aerospace Conference (AERO), pp. 1–14, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO53065.2022.9843451 (2022).

Neukart, F. et al. Traffic flow optimization using a quantum annealer. Front. ICT 4, 29 (2017).

Ohzeki, M., Miki, A., Miyama, M. J. & Terabe, M. Control of automated guided vehicles without collision by quantum annealer and digital devices. Front. Comp. Sci. 1, 9 (2019).

Tatsumura, K., Hidaka, R., Yamasaki, M., Sakai, Y. & Goto, H. “A currency arbitrage machine based on the simulated bifurcation algorithm for ultrafast detection of optimal opportunity,” Proc. of IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), pp. 1–5, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCAS45731.2020.9181114 (IEEE, 2020).

Tatsumura, K., Hidaka, R., Nakayama, J., Kashimata, T. & Yamasaki, M. Pairs-trading system using quantum-inspired combinatorial optimization accelerator for optimal path search in market graphs. IEEE Access 11, 104406–104416 (2023).

Tatsumura, K., Hidaka, R., Nakayama, J., Kashimata, T. & Yamasaki, M. Real-time trading system based on selections of potentially profitable, uncorrelated, and balanced stocks by NP-hard combinatorial optimization. IEEE Access 11, 120023–120033 (2023).

Goto, H. Bifurcation-based adiabatic quantum computation with a nonlinear oscillator network. Sci. Rep. 6, 21686 (2016).

Kalman, R. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problem. J. Basic Eng. 82, 35–45 (1960).

Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220, 671–680 (1983).

Isakov, S. V., Zintchenko, I. N., Rønnow, T. F. & Troyer, M. Optimised simulated annealing for Ising spin glasses. Comp. Phys. Commun. 192, 265–271 (2015).

Betz, V., Rose, J. & Marquardt, A. “Architecture and CAD for deep-submicron FPGAs,” Springer New York, NY, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-5145-4 (Springer, 1999).

Hidaka, R., Hamakawa, Y., Nakayama, J. & Tatsumura, K. Correlation-diversified portfolio construction by finding maximum independent set in large-scale market graph. IEEE Access 11, 142979–142991 (2023).

Milan, A., Leal-Taixé, L., Reid, I., Roth, S. & Schindler, K. “MOT16: a benchmark for multi-object tracking,” arXiv:1603.00831, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1603.00831 (2016).

Leal-Taixé, L. et al. MOT17-{02, 04, 05, 09, 10, 11, 13}-FRCNN, Accessed: Sep. 17, [Online]. Available: https://motchallenge.net/data/MOT17/ (2024).

Dosovitskiy, A., Ros, G., Codevilla, F., Lopez, A. & Koltun, V. “CARLA: an open urban driving simulator,” Proc. of the 1st Annual Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR 78:1-16 [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v78/dosovitskiy17a.html

Luiten, J. et al. HOTA: A higher order metric for evaluating multi-object tracking. Int. J. Comp. Vis. 129, 548–578 (2021).

Luiten, J. et al. “TrackEval,” Github, last modified: Nov. 30, 2022, last accessed: May 02, [Online]. Available: https://github.com/JonathonLuiten/TrackEval (2023).

Caesar, H. et al. “nuScenes: A multimodal dataset for autonomous driving,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 11621–11631, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01164 (IEEE, 2020).

Zeng, Q.-G. et al. Performance of quantum annealing inspired algorithms for combinatorial optimization problems. Commun. Phys. 7, 249 (2024).

Böhm, F., Van Vaerenbergh, T., Verschaffelt, G. & Van der Sande, G. Order-of-magnitude differences in computational performance of analog Ising machines induced by the choice of nonlinearity. Commun. Phys. 4, 149 (2021).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. “You only look once: unified, real-time object detection,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 779-788, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.91 (CVPR, 2016).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. “YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger,” Proc. of IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 7263–7271, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.690 (IEEE, 2017).

Tatsumura, K., Yazdanshenas, S. & Betz, V. “High density, low energy, magnetic tunnel junction based block RAMs for memory-rich FPGAs,” Proc. of Int’l Conf. on Field-Programmable Technology (FPT), pp. 4–11, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/FPT.2016.7929181 (FPT, 2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yoshihiko Isobe, Masataka Hirai, Ryo Hidaka, Yutaka Yamada, Yutaro Ishigaki, Tomoya Kashimata, Kei Nihei, Ryota Umino, Hayato Goto, Hiroomi Chono, Akiko Yuzawa, Sakie Nagakubo for the fruitful discussion and their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the whole aspects of this work, with each making the following major contribution. K.T., K.O., and H.F. conceived and managed the project. K.T. devised the flexible assignment method and wrote the manuscript. Y.H. architected the whole system and designed the custom circuit of SB-based Ising machine. M.Y. implemented and integrated the system. K.O. considered the driving scenario. Y.H. and K.O. evaluated the system.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.T., Y.H., and M.Y. are included in inventors on two U.S. patent applications related to this work filed by the Toshiba Corporation (no. 17/249353, filed 20 February 2020; no. 18/456494, filed 27 August 2023). The remaining authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shahrokh Heidari and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tatsumura, K., Hamakawa, Y., Yamasaki, M. et al. Enhancing vehicle-mountable multiple object tracking systems with embeddable Ising machines. Nat Commun 17, 584 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67282-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67282-7