Abstract

Accessing trans-fused N-fused tricyclic frameworks with multiple contiguous stereocenters remains a major challenge in synthesis. We report a synergistic isothiourea/Ir-catalyzed [3 + 2] annulation of arylacetic acid esters with azabenzonorbornadienes, providing trans-fused tricyclic γ-lactams with three contiguous tertiary stereocenters in high regio-, enantio-, and diastereoselectivity. The method tolerates diverse arylacetates, heterocycles, and pharmaceutically relevant carboxylates, and is amenable to gram-scale synthesis. Mechanistic studies support a cooperative cycle involving C1-ammonium enolate formation and enantioselective SN2’ attack on the Ir-activated azabenzonorbornadiene. Downstream functionalizations, including epoxidation, hydrogenation, and amino alcohol formation, demonstrate the versatility of the products. This work establishes a concise and efficient platform for constructing sterically challenging trans-fused tricyclic γ-lactams, highlighting the potential of synergistic catalysis for complex stereocontrolled transformations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

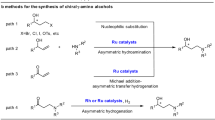

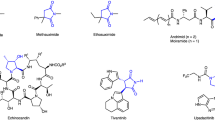

The stereoselective construction of fused heterocyclic architectures is of great importance in pharmaceutical research, as their three-dimensional complexity imparts distinct physicochemical and biological properties1,2,3. Among these, chiral N-fused tricyclic frameworks represent privileged scaffolds in natural products, bioactive molecules, and catalysts, exemplified by strigolactam, carboxylic acid receptors, rivastigmine analogs, and chiral NHC precursors (Fig. 1A)4,5,6,7. Conventional approaches to N-fused tricyclic skeletons bearing multiple stereocenters, particularly chiral tricyclic γ-lactams, typically rely on multistep de novo synthetic routes that are both laborious and resource-intensive8. Recently, Zhang and co-workers reported a direct ruthenium-catalyzed tandem dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR)/asymmetric reductive amination (ARA)/lactamization of ketoesters with ammonium salts, which furnishes cis-fused tricyclic lactams in a single step but requires high-pressure hydrogen gas and offers limited modularity (Fig. 1B)9. Given the broad utility of these structurally complex motifs, the development of efficient and general synthetic strategies to access chiral tricyclic γ-lactams from readily available starting materials remains a critical goal.

A Chiral N-fused tricyclic scaffold as a privileged motif in functional molecules. B A reported method for the synthesis of chiral tricyclic lactams9. C Asymmetric functionalization of activated esters via synergistic catalysis. D Asymmetric ring-opening and annulation of azabenzonorbornadienes. E Synergistic ITU/Ir catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation of esters and azabenzonorbornadienes (this work).

Synergistic catalysis has emerged as a powerful platform for the stereoselective construction of structurally complex molecules10,11,12,13,14,15. Over the past two decades, isothiourea (ITU) catalysis has become a particularly versatile organocatalytic strategy, enabling significant advances in asymmetric transformations, especially in synergistic settings16,17. Since the seminal report by Snaddon and co-workers in 201618, synergistic catalysis involving chiral C(1)-ammonium enolates—generated via ITU-catalyzed substitution of electron-deficient aryl esters followed by deprotonation—has driven remarkable progress in the asymmetric functionalization of esters (Fig. 1C). A wide range of electrophiles, including η³-allyl species and imines, have been successfully coupled through synergistic ITU/transition-metal and ITU/organocatalysis, affording chiral α-functionalized esters19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Despite these achievements, synergistic annulative transformations for the construction of pharmaceutically preferred chiral heterocycles remain largely underexplored31,32. Thus, expanding the scope of ITU-mediated synergistic catalysis to efficiently access pharmaceutically relevant heterocycles is highly desirable.

Strained azabicyclic olefins, particularly azabenzonorbornadienes—a distinctive subclass defined by a bridgehead nitrogen atom and an internal C = C bond—offer powerful platforms for complexity generation through transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric ring-opening (ARO) reactions (Fig. 1D)33,34,35. The bridgehead nitrogen and olefin moieties enable metal coordination and promote selective C–N bond cleavage, while the substantial ring strain (~5.2kcal/mol) arising from shortened bond distances renders the ring-opening process energetically favorable34. Mechanistically, this transformation can proceed via carbometallation followed by β-heteroatom elimination to afford cis-ring-opening products36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49, or through oxidative C–N insertion followed by SN2′ nucleophilic displacement to yield trans-ring-opening products (Fig. 1D, top)50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63. To date, only three examples of asymmetric annulation of azabenzonorbornadienes have been reported, employing organic halides, alkynes, or directing-group (DG)-arenes as coupling partners64,65,66. These strategies, integrating asymmetric ring-opening with oxidative insertion, oxidative cyclization, or transition-metal-catalyzed C–H activation, exclusively afford cis-fused annulated products. Despite this progress, the asymmetric construction of sterically disfavored trans-fused frameworks remains elusive, hindered by competing facile nucleophilic ARO/protonation pathways and the substantially higher ring strain of trans-fusion (Fig. 1D, bottom). Consequently, the development of a general catalytic asymmetric strategy to access enantio- and diastereoselectively enriched trans-fused products from azabenzonorbornadienes represents a compelling and unmet challenge.

Building on the sustained interest in strained oxa/azabicyclic alkenes67 and the growing potential of synergistic catalysis, we now disclose a general asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation of actived arylacetic acid esters with azabenzonorbornadienes, enabled by synergistic ITU/Ir catalysis (Fig. 1E). This strategy provides streamlined access to a broad family of trans-fused tricyclic γ-lactams—structural motifs that have remained synthetically elusive—bearing three contiguous tertiary stereocenters with excellent levels of regio-, and enantio-, and diastereoselectivity. The modularity of this protocol, together with its ability to forge sterically disfavored trans-fused architectures from readily available starting materials, highlights its potential as a powerful platform for the synthesis of pharmaceutically relevant heterocycles.

Results

Optimization studies

We initiated our investigation by employing aryl acetic acid pentafluorophenyl esters 1 and azabenzonorbornadiene 2 as model substrates in MeCN at 70 °C (Fig. 2). Under a synergistic catalytic system comprising [Ir(COD)Cl]2/(S)-DM-SEGPHOS (L1) and (S)-BTM, with DIPEA as the base, the asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation proceeded smoothly, delivering the chiral trans-fused tricyclic γ-lactam in 76% yield with excellent enan-tioselectivity (>99% ee) and diastereoselectivity (>20:1 dr). Alternative diphosphine ligands (L2 and L3) also promoted the transformation, albeit with slightly diminished yields. In contrast, other common ligand classes—including Trost ligand (L4), Josiphos (L5), tBu-Phosferrox (L6), Ph-Pybox (L7), and phosphoramidite (L8)—failed to catalyze the reaction, with most starting material recovered. Lowering the temperature to room temperature or 40 °C completely halted the reaction, and no conversion was observed in alternative solvents such as DCE, THF, or DMSO. Other metal precursors, including CuOTf, Co(acac)₂, NiCl₂, Pd(OAc)₂, RuCl₂, and various rhodium complexes, were also ineffective (see Supplementary Fig. S6 in the SI for details). Reducing the catalyst loading was feasible but resulted in diminished yields. Several common chiral isothiourea catalysts were also evaluated; however, none afforded promising results (see Supplementary Fig. S7 in the SI). Replacing (S)-BTM with (R)-BTM led to decreases in both yield and enantioselectivity. Control experiments confirmed that [Ir(COD)Cl]₂/L1 was essential; although the reaction still proceeded without either (S)-BTM or DIPEA, yields were significantly reduced. Finally, evaluation of the ester leaving group revealed that only strongly electron-deficient phenol derivatives (4-SO₂Me, 4-NO₂, 4-CN) afforded the product with moderately diminished yields, whereas weakly electron-deficient (4-F, 3,4-F₂), neutral (4-H), and electron-rich (4-OMe) esters failed to promote the transformation. These results underscore the crucial role of a strongly electron-withdrawing leaving group for successful reaction outcomes.

A Standard conditions. B Impact of ligands. C Impact of reaction condition. D Impact of leaving group of esters. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2 (0.44 mmol, 2.2 equiv.), [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (3.0 mol%), L1 (6.3 mol%), (S)-BTM (10.0 mol%), DIPEA (2.0 equiv.), MeCN (2.0 mL), 70 °C, 10 h. a Isolated yield. b The enantiomeric excess (ee) was determined by HPLC analysis. See Section VI in the SI for complete screening details.

Substrate scope

With optimized conditions in hand, we explored the substrate scope of the asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation (Fig. 3). The method tolerated a broad range of functional groups and accommodated electronically and structurally diverse pentafluorophenyl esters and azabicyclic alkenes. Arylacetates bearing electron-withdrawing groups such as halogens (F, Cl, Br, I; 4 − 9) or -CF3 (10,11) underwent smooth transformation. The absolute configuration of compound 6 was determined via X-ray crystallography (CCDC 2487060). Electron-rich substrates containing Me (12), NMe₂ (13), and OMe (14, 15) groups also reacted with excellent stereoselectivity. Notably, substrates with highly reactive functionalities—including boronic ester (16), ester (17), and NHBoc (18)—were compatible without significant complications. Substrates bearing OPh (19), SMe (20), or alkenyl (21) groups similarly furnished the desired products in high efficiency. Polycyclic and heterocyclic substrates—including naphthalene (22), quinoline (23), indole (24), benzofuran (25), furan (26), dihydrobenzofuran (27), benzodioxole (28), and thiophene (29)—also underwent the reaction with high enantioselectivity (99- > 99% ee). A range of pharmaceutically relevant carboxyla-tes, including derivatives of Indometacin (30), Actarit (31), Ibufenac (32), Tolmetin (33), Diclofenac acid (34), Felbinac (35), and Isoxepac (36), provided satisfactory yields. Various secondary carboxylic acid esters were also found to be ineffective (see Supplementary Fig. S9 in the SI). Symmetric azabicyclic alkenes with substituents such as F (37), Br (38), methyl (39), and naphthalene (40) underwent the desired [3 + 2] annulation in moderate to high yields with excellent stereocontrol. The benzodioxole-derived azabicyclic alkene (41) was unsuitable due to competitive isomerization under transition-metal catalysis68. Compared to Boc protection, isopropoxycarbonyl (41) and benzyloxycarbonyl groups (42) led to reduced enantioselectivity, highlighting that bulky protecting groups on the bridgehead nitrogen are crucial for achieving high enantioselectivity.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2 (0.44 mmol, 2.2 equiv.), [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (3.0 mol%), L1 (6.3 mol%), (S)-BTM (10.0 mol%), DIPEA (2.0 equiv.), MeCN (2.0 mL), 70 °C, 10 h. Isolated yield. Unless otherwise noted, all products were obtained with > 20:1 dr. a (S)-BINAP instead of (S)-DM-SEGPHOS. b After recrystallization. See Section IV in the SI for complete details.

Synthetic applications

The practicality and robustness of this methodology were further demonstrated through gram-scale synthesis and diverse downstream derivatizations (Fig. 4). The gram-scale reaction of carboxylic ester 1 with azabicyclic alkene 2 afforded product 3 in 61% yield, >99% ee, and >20:1 dr. Epoxidation of the olefin in 3 with m-CPBA proceeded smoothly to give 44 without loss of stereochemical integrity. Chemoselective hydrogenation of the alkene using Pd/C under H2 furnished the saturated product 47, while treatment of 3 with LiAlH4 yielded amino alcohol 48. Sequential dibromination and Boc deprotection of 3 provided 45, and subsequent NaH-mediated HBr elimination afforded vinyl bromide 46. Following Boc deprotection, the resulting amine 49 was protected as a benzyl derivative (50) and could also be elaborated into a chiral NHC precursor 51 via a three-step sequence.

See Supplementary Fig. S1 in the SI for complete details.

Mechanistic studies

Combining our mechanistic studies with literature precedents51,52, we propose a plausible catalytic cycle for this cooperative process (Fig. 5). The acyl ammonium ion pair I is formed upon acylation of the isothiourea Lewis base catalyst by arylacetic acid ester 1, followed by deprotonation with the aryloxide counterion to generate the reactive C1-ammonium enolate II. Concurrently, the [Ir] catalyst coordinates to azabenzonorbornadiene 2 on the exo face and promotes C–N bond cleavage to form intermediate III. Nucleophilic attack of enolate II on the endo face of III at the C3 position occurs via TS1 through an SN2′ pathway, delivering intermediate IV. Subsequent lactamization furnishes the [3 + 2] annulation product 3 and regenerates both catalysts. Notably, the byproduct 13′, generated via aryloxy rebound and protonation of the NMe₂-containing intermediate IV, can be converted to the final product 13 in 50% yield with >99% ee and >20:1 dr under the standard conditions, providing strong support for the proposed mechanism.

In summary, we have developed a general and highly stereoselective [3 + 2] annulation of arylacetic acid esters with azabenzonorbornadienes, enabled by synergistic isothiourea/Ir catalysis. This strategy provides streamlined access to trans-fused tricyclic γ-lactams bearing three contiguous tertiary stereocenters with excellent regio-, enantio-, and diastereoselectivity. The methodology exhibits broad substrate scope, tolerating diverse electronic and steric environments, including functionalized arylacetates, heterocycles, and pharmaceutically relevant carboxylates. Key features of this approach include the use of readily available starting materials, the ability to construct sterically disfavored trans-fused frameworks, and the potential for further structural elaboration through versatile downstream derivatizations. Mechanistic studies support a cooperative catalytic cycle involving C1-ammonium enolate generation and enantioselective SN2′ attack on the Ir-activated azabenzonorbornadiene.

Methods

General procedure of synergistic ITU/Ir catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation of esters and azabenzonorbornadienes

In an atmosphere-controlled glovebox [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (0.006 mmol, 3.0 mol%) and (S)-DM-SEGPHOS (0.0126 mmol, 6.3 mol%) were added to a 2-dram vial charged with a stir bar, followed by the addition of anhydrous MeCN (2.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 min. Carboxylic ester (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), azabicyclic alkene (0.44 mmol, 2.2 equiv.), (S)-BTM (0.02 mmol, 10.0 mol%) and DIPEA (0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were added to another 2-dram vial charged with a stir bar. Subsequently, the solution of Ir catalyst was transferred into this vial. The vial was sealed with a PTFE-lined cap and removed from the glovebox. The reaction was stirred at 70 ˚C in an aluminum block. Upon completion of the reaction (10 h), the mixtures were concentrated in vacuo and directly purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the final product. The ee values were determined by HPLC using a Daicel chiral column.

Data availability

All data, including experimental details, characterization data, NMR and HPLC, are available in the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, under deposition number CCDC 2487060 (6). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Aldeghi, M., Malhotra, S., Selwood, D. L. & Chan, A. W. E. Two- and three-dimensional rings in drugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 83, 450–461 (2014).

Taylor, A. P. et al. Modern advances in heterocyclic chemistry in drug discovery. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 6611–6637 (2016).

Talele, T. T. Opportunities for tapping into three-dimensional chemical space through a quaternary carbon. J. Med. Chem. 63, 13291–13315 (2020).

Lachia, M., Wolf, H. C., Jung, P. J. M., Screpanti, C. & De Mesmaeker, A. Strigolactam: New potent strigolactone analogues for the germination of Orobanche cumana. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 2184–2188 (2015).

Moore, G., Papamicaël, C., Levacher, V., Bourguignon, J. & Dupas, G. Synthesis and study of a heterocyclic receptor designed for carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron 60, 4197–4204 (2004).

Bolognesi, M. L. et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of conformationally restricted rivastigmine analogues. J. Med. Chem. 47, 5945–5952 (2004).

Enders, D., Niemeier, O. & Balensiefer, T. Asymmetric intramolecular crossed-benzoin reactions by N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 1463–1467 (2006).

Ge, Y., Chen, X., Khan, S. N., Jia, S. & Chen, G. Synthesis and germination activity study of novel strigolactam/strigolactone aalogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 115, 154315 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Concise synthesis of chiral tricyclic lactams by tandem dynamic kinetic asymmetric reductive amination/lactamization using ammonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303868 (2023).

Allen, A. E. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Synergistic catalysis: A powerful synthetic strategy for new reaction development. Chem. Sci. 3, 633–658 (2012).

Afewerki, S. & Córdova, A. Combinations of aminocatalysts and metal catalysts: a powerful cooperative approach in selective organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 116, 13512–13570 (2016).

Kim, D.-S., Park, W.-J. & Jun, C.-H. Metal–organic cooperative catalysis in C–H and C–C bond activation. Chem. Rev. 117, 8977–9015 (2017).

Wei, L., Fu, C., Wang, Z.-F., Tao, H.-Y. & Wang, C.-J. Synergistic dual catalysis in stereodivergent synthesis. ACS Catal. 14, 3812–3844 (2024).

Sun, H., Ma, Y., Xiao, G. & Kong, D. Stereodivergent dual catalysis in organic synthesis. Trends Chem. 6, 684–701 (2024).

Sayed, M., Han, Z.-Y. & Gong, L.-Z. Pd-H/Lewis base cooperative catalysis confers asymmetric allylic alkylation of esters atom-economy and stereodivergence. Chem. Synth. 3, 20 (2023).

Merad, J., Pons, J. M., Chuzel, O. & Bressy, C. Enantioselective catalysis by chiral isothioureas. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5589–5610 (2016).

McLaughlin, C. & Smith, A. D. Generation and reactivity of C(1)-ammonium enolates by using isothiourea catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 1533–1555 (2020).

Schwarz, K. J., Amos, J. L., Klein, J. C., Do, D. T. & Snaddon, T. N. Uniting C1-ammonium enolates and transition metal electrophiles via cooperative catalysis: the direct asymmetric α-allylation of aryl acetic acid esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5214–5217 (2016).

Jiang, X., Beiger, J. J. & Hartwig, J. F. Stereodivergent allylic substitutions with aryl acetic acid esters by synergistic iridium and lewis base catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 87–90 (2017).

Schwarz, K. J., Pearson, C. M., Cintron-Rosado, G. A., Liu, P. & Snaddon, T. N. Traversing steric limitations by cooperative lewis base/palladium catalysis: an enantioselective synthesis of α-branched esters using 2-substituted allyl electrophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7800–7803 (2018).

Scaggs, W. R. & Snaddon, T. N. Enantioselective α-allylation of acyclic esters using B(pin)-substituted electrophiles: independent regulation of stereocontrol elements through cooperative Pd/Lewis base catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 14378–14381 (2018).

Hutchings-Goetz, L., Yang, C. & Snaddon, T. N. Enantioselective α-allylation of aryl acetic acid esters via C1-ammonium enolate nucleophiles: identification of a broadly effective palladium catalyst for electron-deficient electrophiles. ACS Catal. 8, 10537–10544 (2018).

Fyfe, J. W. B., Kabia, O. M., Pearson, C. M. & Snaddon, T. N. Si-directed regiocontrol in asymmetric Pd-catalyzed allylic alkylations using C1-ammonium enolate nucleophiles. Tetrahedron 74, 5383–5391 (2018).

Schwarz, K. J., Yang, C., Fyfe, J. W. B. & Snaddon, T. N. Enantioselective α-benzylation of acyclic esters using π-extended electrophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12102–12105 (2018).

Rush Scaggs, W., Scaggs, T. D. & Snaddon, T. N. An enantioselective synthesis of α-alkylated pyrroles via cooperative isothiourea/palladium catalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 1787–1790 (2019).

Kim, B., Kim, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Stereodivergent carbon–carbon bond formation between iminium and enolate intermediates by synergistic organocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 73–79 (2021).

Zhao, F. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of α-aryl-β2-amino-esters by cooperative isothiourea and brønsted acid. Catal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 11999–12007 (2021).

Lin, H.-C., Knox, G., Pearson, C., Carta, V. & Snaddon, T. A PdH/Isothiourea cooperative catalysis approach to anti-aldol motifs: enantioselective α-alkylation of esters with oxyallenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201753 (2022).

Zhu, M., Wang, P., Zhang, Q., Tang, W. & Zi, W. Diastereodivergent aldol-type coupling of alkoxyallenes with pentafluorophenyl esters enabled by synergistic palladium/chiral lewis base catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207621 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Zhu, M. & Zi, W. Synergizing palladium with Lewis base catalysis for stereodivergent coupling of 1,3-dienes with pentafluorophenyl acetates. Chem 8, 2784–2796 (2022).

Song, J., Zhang, Z.-J., Chen, S.-S., Fan, T. & Gong, L.-Z. Lewis base/copper cooperatively catalyzed asymmetric α-amination of esters with diaziridinone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3177–3180 (2018).

Wang, Q., Fan, T. & Song, J. Cooperative isothiourea/iridium-catalyzed asymmetric annulation reactions of vinyl aziridines with pentafluorophenyl esters. Org. Lett. 25, 1246–1251 (2023).

Rayabarapu, D. K. & Cheng, C.-H. New catalytic reactions of oxa and azabicyclic alkenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 971–973 (2007).

Vivek Kumar, S., Yen, A., Lautens, M. & Guiry, P. J. Catalytic asymmetric tansformations of oxa- and azabicyclic alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 3013–3093 (2021).

Pounder, A., Neufeld, E., Myler, P. & Tam, W. Transition-metal-catalyzed domino reactions of strained bicyclic alkenes. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 19, 487–540 (2023).

Lautens, M. & Dockendorff, C. Palladium(II) catalyst systems for the addition of boronic acids to bicyclic alkenes: new scope and reactivity. Org. Lett. 5, 3695–3698 (2003).

Nishimura, T., Tsurumaki, E., Kawamoto, T., Guo, X.-X. & Hayashi, T. Rhodium-catalyzed csymmetric ring-opening alkynylation of azabenzonorbornadienes. Org. Lett. 10, 4057–4060 (2008).

Ogura, T., Yoshida, K., Yanagisawa, A. & Imamoto, T. Optically active dinuclear palladium complexes containing a Pd−Pd bond:preparation and enantioinduction ability in asymmetric ring-opening reactions. Org. Lett. 11, 2245–2248 (2009).

Fan, B. et al. Palladium/copper complexes co-catalyzed highly enantioselective ring opening reaction of azabenzonorbornadienes with terminal alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 2827–2832 (2013).

Mannathan, S. & Cheng, C. H. Nickel-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective reductive coupling of Oxa- and azabicyclic alkenes with enones and electron-rich alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 356, 2239–2246 (2014).

Huang, Y., Ma, C., Lee, Y. X., Huang, R. Z. & Zhao, Y. Cobalt-catalyzed allylation of heterobicyclic alkenes: ligand-induced divergent reactivities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13696–13700 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Enantioselective ring opening reactions of azabenzonorbornadienes with carboxylic acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 358, 3167–3172 (2016).

He, Z. X. et al. Asymmetric ring-opening reaction of azabenzonorbornadienes with phenols promoted by palladium/(R, R)-DIOP complex. Tetrahedron 74, 2174–2181 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed asymmetric reactions of heterobicyclic alkenes with in situ generated organozinc halides. Org. Chem. Front. 5, 1108–1112 (2018).

Yang, X., Zheng, G. & Li, X. Rhodium(III)-catalyzed enantioselective coupling of Indoles and 7-Azabenzonorbornadienes by C−H activation/desymmetrization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 322–326 (2018).

Shen, G. et al. Pd/Zn Co-catalyzed asymmetric ring-opening reactions of Aza/oxabicyclic alkenes with oximes. Asian J. Org. Chem. 8, 97–102 (2018).

Luo, Y. et al. Oxa- and azabenzonorbornadienes as electrophilic artners under hotoredox/nickel dual catalysis. ACS Catal. 9, 8835–8842 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. Directing-group-controlled ring-opening addition and hydroarylation of Oxa/azabenzonorbornadienes with arenes via C–H activation. Org. Lett. 22, 3339–3344 (2020).

Zheng, Y., Zhang, W.-Y., Gu, Q., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Cobalt(III)-catalyzed asymmetric ring-opening of 7-oxabenzonorbornadienes via indole C–H functionalization. Nat. Commun. 14, 1094 (2023).

Lautens, M., Fagnou, K. & Zunic, V. An expedient enantioselective route to diaminotetralins: application in the preparation of analgesic compounds. Org. Lett. 4, 3465–3468 (2002).

Cho, Y. -h, Zunic, V., Senboku, H., Olsen, M. & Lautens, M. Rhodium-catalyzed ring-opening reactions of N-Boc-azabenzonorbornadienes with amine nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6837–6846 (2006).

Yang, D., Long, Y., Wang, H. & Zhang, Z. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric ring-opening reactions of N-Boc-azabenzonorbornadiene with secondary Amine. Org. Lett. 10, 4723–4726 (2008).

Long, Y. et al. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric ring opening of Aazabicyclic Alkenes by Amines. J. Org. Chem. 75, 7291–7299 (2010).

Yang, D. et al. Iridium-catalyzed anti-stereocontrolled asymmetric ringppening of azabicyclic ~ lkenes with P_supplementaryrimary Aromatic Amines. Organometallics 29, 5936–5940 (2010).

Fang, S. et al. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric ring-opening of azabicyclic alkenes with phenols. Organometallics 31, 3113–3118 (2012).

Yang, D. et al. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric ring-opening of azabicyclic alkenes with alcohols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 4871–4881 (2013).

Zhang, L., Le, C. M. & Lautens, M. The use of silyl ketene acetals and enol ethers in the catalytic enantioselective alkylative ring Opening of Oxa/Aza bicyclic Supplementarylkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5951–5954 (2014).

Zeng, C., Yang, F., Chen, J., Wang, J. & Fan, B. Iridium/copper-cocatalyzed asymmetric ring opening reaction of azabenzonorbornadienes with amines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 8425–8428 (2015).

Yang, F. et al. Palladium/lewis acid co-catalyzed divergent asymmetric ring-opening reactions of azabenzonorbornadienes with alcohols. Org. Lett. 18, 4832–4835 (2016).

Chen, J., Zou, L., Zeng, C., Zhou, Y. & Fan, B. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric arylative ring-opening Reactions of heterobicyclic alkenes with anilines. Org. Lett. 20, 1283–1286 (2018).

Luo, R. S. et al. Enantioselective iridium-catalyzed ring opening of low-activity azabenzonorbornadienes with Amines. Organometallics 37, 1652–1655 (2018).

Yang, X., Yang, W., Yao, Y., Deng, Y. & Yang, D. Ir-Catalyzed ring-opening of oxa(aza)benzonorbornadienes with water or alcohols. Org. Chem. Front. 6, 1151–1156 (2019).

Kamzol, D., Bahramiveleshkolaei, M. & Wilhelm, R. Camphor-based NHC ligands with a sulfur ligator atom in rhodium catalysis: catalytic advances in the asymmetric ring opening of N-protected azabenzonorbornenes. Org. Lett. 27, 8417–8422 (2025).

Huang, K. L. et al. Enantioselective palladium-catalyzed tiing-opening Reaction of Azabenzonorbornadienes with Methyl 2-Iodobenzoate: An Efficient Access to cis-Dihydrobenzo[c]phenanthridinones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 2833–2838 (2013).

Wang, S. G., Park, S. H. & Cramer, N. A readily accessible class of chiral Cp ligands and their application in ruII-catalyzed enantioselective syntheses of dihydrobenzoindoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5459–5462 (2018).

Mi, R., Zheng, G., Qi, Z. & Li, X. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective oxidative [3+2] annulation of arenes and azabicyclic olefins through twofold C−H activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17666–17670 (2019).

Xiao, G., Chen, Y., Wan, Z. & Kong, D. Asymmetric multi-atom insertion of esters via Rh-catalyzed ring opppening of Oxabicyclic Alkenes. Org. Lett. 27, 3782–3788 (2025).

Villeneuve, K. & Tam, W. Ruthenium-catalyzed somerization of oxa/azabicyclic alkenes: an expedient route for the synthesis of 1,2-Naphthalene Oxides and Imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3514–3515 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (2232015), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22471011), Beijing Nova Program (20230484447).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K. designed the project and directed the work; G.X. developed the catalytic method; G.X. and M.Y. performed all synthetic experiments. D.K. and G.X. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Baomin Fan and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, G., Yang, M. & Kong, D. Concise synthesis of chiral tricyclic γ-lactams via synergistic isothiourea/Ir catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] annulation. Nat Commun 17, 644 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67390-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67390-4