Abstract

Aqueous zinc-ion batteries have emerged as a promising system for safe and sustainable energy storage. However, their practical application is hindered by detrimental interfacial side reactions and inadequate low-temperature performance. Herein, we report the design of a gradient chaotropic ionic liquid (IL)-based aqueous electrolyte (Emim⁺-TFA⁻/OTf⁻-Zn2+-H2O), which can simultaneously fulfil the conflicting demands of dendrite-free zinc deposition and low-temperature operation. By forming an antifreeze electrolyte with a hydrophobic yet salt-philic interface, the proposed formulation overcomes the limitations of conventional IL-based systems that rely on H2O-lean compositions, complex additives, or elaborate solvent mixtures. Thus, the assembled zinc-ion cells exhibit improved zinc plating/stripping stability. At a current density of 0.1 mA cm−2 and 0.1 mAh cm−2, the Zn | |Zn symmetric cells endure prolonged zinc plating/stripping, exceeding 13,000 h at −30 °C and 6690 h at −40 °C. In full cells, Zn | |VO2@VO maintains nearly 100% capacity retention over 3500 cycles at 0.2 A g−1 and −40 °C. This gradient chaotropic Zn2+ electrolyte design provides a versatile platform for effective antifreeze Zn2+ solvation chemistry and accelerated interfacial ion transport, enabling high-performance zinc batteries in subzero environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growing demand for safe and sustainable alternatives to lithium-based systems1,2,3, aqueous zinc metal batteries (ZMBs) are gaining increasing attention for future stationary energy storage systems, due to their intrinsic safety, economic viability, and satisfactory performance4,5,6. However, the zinc metal negative electrode is thermodynamically instability in aqueous electrolytes, leading to irreversible parasitic reactions including hydrogen evolution and the formation of by-products (e.g., ZnO, Zn(OH)42−). Besides, internal short circuits and eventual battery failure can occur because of uncontrolled zinc dendrite growth, which originates from non-uniform Zn2+ deposition at the electrode interface. Furthermore, when the temperature drops below 0 °C, H2O molecules in the electrolyte tend to form additional hydrogen bonds (H-bonds, ~0.52 per molecule), driving a transition from a disordered liquid state to an ordered crystalline structure, resulting in ice formation7,8. Therefore, despite their high ionic conductivity, aqueous electrolytes are prone to freezing at low temperatures, which significantly hinders Zn2+ transport and reduces battery lifespan9. Thus, these challenges restrict the practical implementation of ZMBs, especially under low-temperature conditions.

Various approaches have been explored to overcome the challenges associated with zinc metal negative electrodes, such as constructing protective interfacial layers, introducing functional additives, and designing co-solvent systems10,11,12. Among these strategies, co-solvent engineering is an effective approach for simultaneously stabilizing the zinc metal negative electrode and enhancing low-temperature tolerance. Co-solvents act by disrupting the structured H-bonds network of aqueous electrolytes, reducing interfacial H2O activity and promoting solvent-salt decoupling, which collectively contribute to improved negative electrode stability and antifreeze performance13. It is crucial to minimize interface H2O activity to further enhance the electrochemical performance of zinc metal negative electrodes. However, conventional strategies based on hydrophobic or H2O-lean interfacial designs would inevitably increase interfacial resistance and impede Zn2+ transport kinetics, compromising battery performance under cold conditions14. Furthermore, excessive incorporation of antifreeze co-solvents would significantly lower ionic conductivity, which induces severe concentration polarization, dendrite formation, and parasitic side reactions15. As a result, simultaneously protecting the zinc negative electrode from side reactions, regulating Zn2+ deposition, and lowering the freezing point of aqueous electrolytes to improve the low-temperature performance of ZMBs presents a significant challenge for electrolyte engineering.

Compared with the above-mentioned methods, optimizing electrolytes will directly regulate the solvation structure to decrease the H2O activity, reducing the possibility of side reactions. The anions or organic fractions tend to form a stable solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) by electrochemical decomposition or spontaneous chemical reactions, facilitating a high-quality Zn2+ stripping/plating process16. Significantly, certain ionic species or specific functional groups in the electrolyte can disrupt the H-bonds network of H2O, lowering the freezing point of aqueous electrolytes17. From these design perspectives, ionic liquids (ILs) are ionic compounds composed of organic cations and anions, featuring tunable structures and functionalities, making them ideal candidates for comprehensive electrolyte-component regulation18. Attributable to their inherent merits, such as high ionic conductivity, high electrochemical stability, wide electrochemical window, low volatility, and low melting points, ILs have been widely utilized as electrolyte additives in ZMBs19. Correspondingly, extensive research has been devoted to tailoring cation-anion chemistry to optimize their electrochemical performance20. Specifically, the steric shielding effect and hydrophobicity of bulky IL cations help stabilize the zinc surface, while reactive anions participate in interfacial chemistry to form an inorganic-rich layer (e.g., ZnF2, ZnCO3, ZnO, and ZnS) with fast ion-conducting pathways21. Nevertheless, their role in forming a H2O-deficient electric double layer (EDL) at the zinc negative electrode necessitates precise content control, as excessive amounts may hinder ion transport and interfacial kinetics due to their inherent hydrophobicity and cation-shielding effects22. Alternatively, ILs have been employed in H2O-lean quasi-solid or solid electrolytes, aiming to eliminate active H2O and construct highly stable zinc battery systems, albeit at the expense of ionic conductivity23. As a result, only a few studies have explored the combination of ILs with other antifreeze solvents to develop low-temperature electrolytes24. However, the introduction of such co-solvents always leads to a significant decrease in ionic conductivity, safety risks, environmental concerns, and poor compatibility with implantable biomedical applications15. Therefore, using ILs as comprehensive electrolyte regulators in aqueous systems to optimize both interfacial structure and low-temperature performance remains challenging and often requires additional modulation with complex co-solvents or engineered additives, increasing system complexity and cost. The Hofmeister series, also known as ion-specific effects, categorizes ions based on their relative capacity to influence protein solubility in solutions, resulting in a characteristic ordering25. Ions identified as chaotropic anions exhibit a pronounced ability to destabilize protein conformation and stability. Moreover, it has been confirmed that they will break the H-bonds network formed by H2O molecules26.

Herein, we propose a holistic component-modulation engineering for aqueous electrolytes, achieving robust Zn2+ solvation chemistry and enhanced electrochemical performance in aqueous zinc-based batteries. Taking ILs as a demonstration, we introduce a gradient chaotropic Zn2+ electrolyte formulation to construct antifreeze Zn2+ solvation chemistry and achieve improved zinc metal negative electrode stability. Retaining the interfacial EDL modulation capability of hydrophobic bulky cations, the gradient chaotropic anions were introduced to mitigate the excessive accumulation of IL cations at the interface, allowing ILs to effectively function as a single co-solvent in aqueous electrolytes. Both theoretical calculations and a series of in-situ/ex-situ characterizations demonstrate that the proposed electrolyte configuration fundamentally transforms the Zn2+ solvation chemistry, yielding an antifreeze electrolyte with a hydrophobic yet salt-philic interfacial environment. This transformation profoundly alters the H-bond networks within aqueous Zn2+ electrolytes, promoting the formation of an H2O-deficient and Zn2+ conductive SEI layer, and effectively suppressing the dissolution of metal oxide positive electrodes. Thus, stable cycling performance is achieved even under low-temperature conditions. At 25 °C, the zinc negative electrode delivers a zinc plating/stripping lifespan nearly 25 times longer than that in the blank electrolyte under 1.0 mA cm−2 and 1.0 mAh cm−2. Besides, Zn||Zn symmetric cells achieve stable operation for over 13,000 h at −30 °C and 6692 h at −40 °C (0.1 mA cm−2, 0.1 mAh cm−2). Significantly, at a temperature of −40 °C, the Zn | |VO2@VO presents virtually no decline in discharge-specific capacity over 3500 cycles under 0.2 A g−1. Our electrolyte formulation could establish a versatile platform for effective antifreeze Zn2+ solvation chemistry and highly stable ZMBs.

Results and discussions

Reconstructing Zn2+ solvation chemistry via ILs

The proposed gradient chaotropic Zn2+ electrolyte was prepared by introducing 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate ([Emim][TFA], denoted as EFA) as a single cosolvent into a zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate-H2O (Zn(OTf)2-H2O) electrolyte system. Firstly, the associated interactions between these ions are weakened due to the significant volume difference between the cations and anions of the Zn(OTf)2-H2O-EFA system27. Secondly, the independently dispersed Emim+ possesses the positively charged imidazole ring that prefers to absorb on the surface of the zinc surface, which is conducive to decreasing the free H2O molecules in the inner Helmholtz plane (IHP). Attributed to the spontaneous electrostatic reaction, the positively charged IHP promotes the accumulation of anions within the EDL, forming an anion-derived SEI in the subsequent cycle. Thirdly, the TFA− anions from Emim-based ILs and the OTf− anions from zinc salts are relatively inert and are positioned adjacent in the Hofmeister series. As prototypical chaotropic anions, they will cooperate to disrupt the H-bonds network and modulate the molecular organization of H2O, resulting in increased structural disorder and lowering the freezing point of the whole electrolyte28,29. Its strong coordination affinity further enables reversible Zn2+ ion transport across the IL-modified IHP, whereas the adjacent chaotropic OTf− anion introduces moderate hydrophobic character to the electrolyte, contributing to interfacial stability.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were employed to elucidate the regulatory effect of EFA on the EDL structure (Supplementary Fig. 1). The results reveal that the adsorption energy of Emim+ on the surface of zinc foils significantly exceeds that of the anions (TFA− and OTf−) and H2O. This strong interaction ensures the preferential adsorption of Emim+ onto the electrode surface, rather than H2O, resulting in a reduction in interfacial H2O content30. Additionally, the binding energies of the Emim+-TFA− (−0.527 eV) and Emim+-OTf− (−0.528 eV) are notably higher than Emim+-H2O (−0.215 eV) (Supplementary Fig. 2a), demonstrating that anions are preferentially migrating into and aggregating in IHP (Fig. 1a, b). Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulation displays the distribution of ions and molecules near the zinc negative electrode surface. The abundant H2O molecules aggregate within the ~5–10 Å from the surface of the zinc negative electrode in the blank electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). However, strong adsorption of Emim+ via its hydrophobic alkyl chains, together with robust ion pairing with chaotropic anions, impedes H2O from accessing the zinc surface, thereby reducing interfacial H2O and producing a hydrophobic, salt-philic interface (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). Thus, a robust SEI with high conductivity, composed of ZnF2, ZnO, ZnS, and ZnCO3, is formed on the surface of the zinc negative electrode, due to the formation of H2O-poor and anion-rich EDL31.

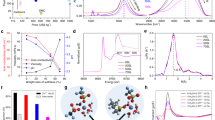

a, b Schematic diagrams of the EDL structure with and without EFA addition (IHP and OHP are inner Helmholtz plane and outer Helmholtz plane, respectively). c MD simulation and d RDF of EFA-containing electrolytes. e Zn K-edge XANES spectra, f FT-EXAFS spectra in R space; g and h WT-EXAFS spectra of blank and EFA-containing electrolytes. i SAXS of electrolytes. j–l 2D 19F-1H HOESY of electrolytes.

Electrostatic potential (ESP) analysis and the results of binding energies reveal that the TFA⁻ possesses a stronger interaction with Zn2+ compared to those in H2O and OTf⁻ (Supplementary Fig. 2f–i)29. Therefore, different from traditional electrolytes ([Zn(H2O)6]2+), the anions will partly replace the H2O molecule in the Zn2+-H2O structure in the electrolytes to reshape the coordination environment of Zn2+. To further investigate the Zn2+ solvation structures across different electrolytes, MD simulations were performed. In the Zn2+-OTf⁻-H2O system (blank electrolyte), H2O molecules form the inner solvation shell by coordination with Zn2+ (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). For the EFA-containing electrolyte, the anions tend to partly replace the H2O and access the first solvation shell of Zn2+ (Fig. 1c). Radial distribution function (RDF) and coordination number (CN) analysis can quantify the number of TFA− participating in the initial solvation layer (Fig. 1d). The CNs of Zn-O (H2O), Zn-TFA−, and Zn-OTf− of 4.9, 0.75, and 0.35, respectively, a well-defined complex of [Zn(H2O)4.9(TFA−)0.75(OTf−)0.35]+. The decreasing H2O ratio in the inner solvation layer will mitigate the HER and side reaction caused by active H2O32.

To evaluate the essential role of gradient chaotropic anions (as opposed to a single species) in optimizing solvation structure and electrochemical performance, we substituted EmimTFA with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([Emim][OTf], denoted as ETF) and conducted detailed solvation structural characterization. As shown in the Zn K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra, the lowest absorption edge of zinc foil is due to its zero-valence state (Fig. 1e). Solvated species differ in electron-donating ability, and these differences drive the changes in absorption edge energy across electrolytes33. Therefore, the lower energy of EFA demonstrates that the chaotropic anions (OTf− and TFA−) donate more electrons to Zn2+ and the existence of more contact ion pairs (CIP)34,35. The local coordination environment of the Zn2+ solvation shell was investigated by Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra and wavelet-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (WT-EXAFS). Compared with the blank and ETF-containing electrolytes, the lower Zn-O peak in EFA-containing electrolytes indicates reduced Zn2+-H2O coordination in the Zn2+ solvation structure (Fig. 1f)35. Furthermore, a split feature at 2.16 Å is indicative of Zn-F (TFA−) coordination, originating from direct interactions between Zn2+ and the F atoms of the chaotropic anions36. These results confirm the coordination of chaotropic anions and Zn2+. The results of WT-EXAFS further confirm this conclusion (Fig. 1g, h and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) proves the evolution of the solvation structure of Zn2+ in various electrolytes (Fig. 1i). A broad scattering peak at 1.86 Å−1 accompanied by an enlarged 2D SAXS scattering ring is characteristic of a classic aqueous hydration shell in blank electrolytes. In the presence of IL, the lower-q peak and the smaller 2D SAXS ring are consistent with an increased real-space correlation length (d = 2π/q) and larger solvation nanoclusters37. Importantly, the 2D SAXS pattern for the EFA-containing electrolyte exhibits a blurred ring contour, in contrast to the ETF system. This difference confirms a more disordered solvation structure, where gradient chaotropic anions of TFA⁻ and OTf⁻ have successfully penetrated and replaced H2O molecules in the Zn2+ solvation shell38. Furthermore, the 2D 19F-1H heteronuclear Overhauser spectroscopy (HOESY) provides effective evidence for the breaking of the H-bond network by the gradient chaotropic anions (Fig. 1j–l and Supplementary Fig. 3d–g). Compared with the blank and ETF-containing electrolytes, where only F (OTf−)-H (H2O) interactions are observed (inside the brown circles), the EFA exhibits a coupling peak between F (TFA⁻) and H (H2O) (inside the blue circles), confirming the cooperation of these anions in breaking the H-bond network39.

To elucidate the cosolvent effect of EFA, a series of electrolytes with varied EFA concentrations was formulated and subjected to comprehensive physicochemical and electrochemical characterization. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 4a, compared with the blank electrolyte, 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR) peaks of EFA-containing electrolytes are collectively shifted downfield, indicating a decreased electron density and proton shielding in H2O. This phenomenon is attributed to the disruption of the original intermolecular H-bond network of H2O by the chaotropic anions40,41. As the EFA concentration increased, the ¹H peak progressively shifted upfield, indicating the gradual release of H2O molecules from the Zn2+ solvation shell, thereby increasing the involvement of anions in the Zn2+ solvation environment42.

The evolution of the Zn2+ solvation structure and H-bonds as different proportions of EFA were added was further probed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopies. The corresponding Zn2+-solvating peaks become more pronounced as the amount of IL increases (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The O-H stretching band of H2O molecules exhibits a broad absorption range between 3800 ~ 2800 cm−1, corresponding to various H-bond strengths from weak to strong interactions (Supplementary Fig. 4c–f). With increasing EFA concentrations, the percentage of strong hydrogen (S-H) bonds decreased significantly, while that of weak hydrogen (W-H) bonds increased. This result is ascribed to TFA− ions acting as H-bond acceptors, disrupting the original H-bond network17,29. The Raman spectra revealed the –SO3 vibrational band (1010 ~ 1050 cm−1) of OTf−, which could be further deconvoluted into three distinct components: free anions (FA, OTf⁻, 1023 cm−1), solvent-separated ion pairs (SSIP, Zn2+-H2O, 1030 cm−1), and CIP (Zn2+-TFA−-OTf−, 1035 cm−1), as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4g. The proportion of CIPs increases upon the addition of EFA, which facilitates the formation of an anion-derived ion-conductive SEI (Supplementary Fig. 4h)3,43,44. Such an anion-rich solvation structure, modulated by the gradient chaotropic anions, further induces substantial H-bonds disorder within the electrolyte matrix. Based on the gradient chaotropic anions and the bulk Emim+ cations, these results demonstrate that the disruption of the H-bond network in EFA-containing electrolytes, coupled with the formation of an anion-rich solvation structure, facilitates the suppression of side reactions and fosters uniform Zn2+ deposition at both low and ambient temperatures.

Gradient chaotropic Zn2+ electrolyte for zinc metal compatibility

The effects of EFA in improving zinc charge/discharge behavior are evaluated by Zn||Zn symmetric cells. In 20% EFA electrolyte, the cell demonstrates a steady zinc plating/stripping behavior over 2500 h at 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2 (at 25 °C). By comparison, the cell failed after only 125 h in the blank electrolyte, primarily attributed to the uncontrolled zinc dendrites growth (Fig. 2a). In addition, the Zn||Zn cells in 10, 30, and 40% EFA electrolyte exhibit stable zinc plating/stripping performance of 480, 450, and 370 h, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, increasing the EFA concentrations (such as 70% EFA and 90% EFA) leads to a decline in cycle life, accompanied by a significant voltage polarization increase, which may stem from the high viscosity of EFA impeding ion transport.

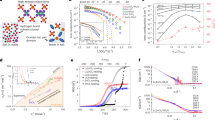

Zinc plating/stripping life of Zn||Zn cell at 25 °C: a 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2, b 20.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2. c Depth of discharge (DOD) test. d Rate ability. e CE of Zn||Cu cell at 5.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2. EIS and corresponding DRT of f blank electrolyte and g 20% EFA electrolyte. h, i 2D GIWAXS and j, k (002) pole figures of zinc negative electrode in different electrolytes after 50 cycles at 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2 (the testing temperature is 25 °C).

The ion conductivity of the EFA-containing electrolyte is decreased from 4.58 to 2.24 × 10−2 S cm−1 with the increase of EFA (Supplementary Fig. 6). As the performance observed above, the 20% EFA electrolyte is identified as an optimized formulation for subsequent characterizations and electrochemical testing. As anticipated, the zinc negative electrode in the 20% EFA electrolyte stabilizes for more than 5400 cycles at 20.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2, markedly outperforming the blank electrolyte (Fig. 2b). To probe its feasibility under the practical conditions, Zn||Zn symmetric cells were subjected to high depth of discharge (DOD) testing. When the high DOD is increased to 81.2%, the symmetrical cell with 20% EFA delivered a stable plating/stripping process over 780 h, which is significantly longer than the cells assembled using blank electrolytes (about 20 h) (Fig. 2c)45. Attributed to the establishment of H2O-poor and anion-rich EDL, the cell with the hybrid electrolyte illustrates an enhanced rate capability. The cell in 20% EFA electrolyte can cycle stably even after experiencing a high current density of 45.0 mA cm−2 and 1.0 mAh cm−2, indicating an enhanced reaction kinetics (Fig. 2d)9. Besides, the Zn||Cu cell in the 20% EFA displays a significantly prolonged zinc plating/stripping processes with an average coulombic efficiency (CE) over 99.3 % during the whole 1000 cycles at 5.0 mA cm−2 and 1.0 mAh cm−2 (Fig. 2e). In comparison, in the blank electrolyte, the cell suffers from a decay within the initial 50 cycles, primarily attributed to parasitic reactions driven by the presence of free H2O at the electrode-electrolyte interface46.

In-situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed during the zinc plating/stripping processes of Zn||Zn symmetric cells to evaluate the distribution of relaxation times (DRT), which enables comprehensive tracking of the zinc deposition/dissolution behavior and decouples the relationship between H2O-poor and anion-rich EDL and the electrochemical performance. The peaks along with the relaxation times (τ) from 10−5 to 10 s confirm the relaxation of electrons (C1), the absorption and desolvation of the [Zn(H2O)6]2+ on the interface (C2), the migration and crystallization of Zn2+ and zinc atom on the electrode (C3), and electron transfer and ion diffusion (C4), respectively47,48,49. Compared with the blank electrolyte, the cell with 20% EFA stabilize rapidly after only the first cycle and with a smaller τ value, demonstrating a stabler interfacial and faster interface reaction kinetics (Fig. 2f, g and Supplementary Fig. 7)48,50. X-ray diffraction (XRD) results confirm the interfacial stability of the electrodes. The distinct characteristic peaks corresponding to by-products (Znx(OTf)y(OH)2x-y·H2O) are observed after zinc plating/stripping in the blank electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In contrast, the H2O-poor and anion-rich EDL formed in 20% EFA effectively suppresses side reactions. In addition, an enhanced (002) crystal plane is observed, indicating a dense (002) oriented deposition, which is attributed to the preferential adsorption of Emim+ on the (002) crystal planes, thereby reducing the growth rate of this plane and resulting in the final exposure of (002)-oriented texture51. To further corroborate the preferred zinc deposition along the (002) plane, 2D grazing incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (2D GIWAXS) complemented by XRD texture analysis was used to perform detailed structural characterization. After zinc plating/stripping in the blank electrolyte, the negative electrode displays weak and diffuse Debye–Scherrer rings corresponding to the (101), (100), and (002) planes of zinc, suggesting polycrystalline and randomly oriented deposition (Fig. 2h). However, the negative electrode cycled in the 20% EFA shows a sharp and continuous diffraction ring assigned to the (002) plane, indicating highly oriented crystallization (Fig. 2i). These results are further supported by the (002) pole figures analysis (Fig. 2j, k). In contrast with the blank electrolyte, the negative electrode cycled from the 20% EFA electrolyte displays a pronounced high-intensity region at the center. These results unambiguously confirm that the EFA will promote the Zn (002) oriented deposition52. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) patterns reveal the zinc deposition morphology in electrolytes. In the blank electrolyte, the Cu substrate in the Zn||Cu cell shows an uneven surface, along with significant separator contamination after 50 cycles at 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 8b). The results of AFM further confirm the heterogeneous morphology with a huge height variation (Supplementary Fig. 8d). A denser zinc deposition layer forms on the Cu substrate in 20% EFA, aligning with the AFM results (Supplementary Fig. 8c and e).

As mentioned above, these anions are aggregated in the IHP. Using frontier molecular orbital theory, the stability of various complexes in the electrolyte was investigated. Although Zn2+-H2O exhibits the highest reduction propensity, the strong adsorption of Emim⁺ effectively excludes interfacial H2O, thereby preventing H2 evolution and corrosion caused by H2O decomposition. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) value of [Zn2+-OTf−]+ (−2.69 eV) is lower than that of [Zn2+-TFA−]+ (−2.49 eV), suggesting that the [Zn2+-OTf−]+ complex is preferred to decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 9). These findings suggest that the anions prefer to decompose preferentially, and simultaneously from a high-conductivity SEI on the surface of the zinc negative electrode53. To verify that the highly ion-conductive and anion-derived SEI, the composition of zinc deposits after plating/stripping was characterized and analyzed. As demonstrated in Fig. 3a, the zinc deposits are tightly covered by a moderately thick layer of SEI, about 30 nm. Especially, those inorganic compounds such as ZnF2, ZnS, ZnO, and ZnCO3 are distributed in the SEI (Fig. 3b, c). Ar+ sputtering X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Time-of-flight secondary-ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) reveal the spatial distribution of these compounds in SEI. In F 1s spectra, the peaks at 688.1 eV and 685.5 eV are associated with the –CF3 and ZnF2, respectively. As the etching progresses, the peaks belonging to the ZnF2 are gradually obvious, which can be attributed to the decomposition of the anion (OTf− and TFA−) (Fig. 3d). One detail that needs to be noted is that when the etching depth continues to 30 nm, the peak value attributed to –CF3 disappears. Similarly, a predominant ZnS (162.6 eV) signal and a diminished −CF3SO3 (169.9 eV) peak are displayed in the S 2p spectrum. The intensity of –CF3 signal (293.0 eV, C 1s spectrum) and C = O/S-O signal (533.9 eV, O 1s spectrum) derived from the incomplete reduction of anions decreases with the etching process. The inorganic component of ZnCO3 in SEI is attributed to the dissolution of CO2 and the TFA− decomposition16,54. Besides, the favorable composition of ZnO is observed after etching. Reversely, in the blank electrolyte, the high content of organic components can still be detected in the later stage of the etching process (Supplementary Fig. 10). Based on the above analysis, it is reasonable to propose that the robust inorganic nanocrystalline compounds constitute the predominant component of the SEI, facilitating Zn2⁺ transport in 20% EFA electrolyte. Furthermore, most organic compounds are distributed in the outer layer of the SEI, isolating the active H2O to inhibit the side reactions and adapting the electrode volume variation in zinc plating/stripping55,56. For the blank electrolyte, the randomly distributed compounds in the SEI could not effectively suppress the side reactions and dendrite formation. TOF-SIMs further confirm the absolute occupation of these inorganic compounds ZnF2, ZnO, ZnS, and ZnCO3 in the SEI layer of the zinc negative electrode after plating/stripping in 20% EFA electrolyte (Fig. 3e). The structural contrast between SEI layers formed with and without EFA is clearly depicted in Fig. 3f, g.

a–c HRTEM images, d XPS depth profiles, and e TOF-SIMS results of the spatial distribution of ZnF−, ZnO−, S−, and CO3− on the zinc surface in a 20% EFA electrolyte at 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2 after 50 cycles (the testing temperature is 25 °C). Schematic illustration of SEI derived from f 20% EFA and g blank electrolytes at 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2 after 50 cycles (the testing temperature is 25 °C).

Uniform zinc deposition and suppression of side reactions

Contact angle measurements show improved interfacial wettability with the 20% EFA electrolyte (58.4°) compared to the blank electrolyte (79.2°) (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b), which will promote more uniform zinc deposition57,58. The zeta potential of zinc powder increases from −4.11 mV to 6.21 mV with EFA addition (Supplementary Fig. 11c), resulting from the anchoring of Emim⁺ cations on the zinc surface59. At the same time, the differential capacitance curves demonstrate a considerable decrease in 20% EFA electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 11d). This result corresponds to the Zeta potential test findings, which originated from the replacement absorption of bulky Emim+ to H2O, leading to a thicker EDL18,60. The nucleation overpotential of Zn2+ is notably higher in the 20% EFA electrolyte (90.0 mV) than in the blank electrolyte (46.5 mV) (Supplementary Fig. 11e), which will promote the uniform and dense deposition of Zn2+ 61. To observe the influence of EFA on Zn2+ deposition, in-situ optical microscopy was employed. In the blank electrolyte, zinc deposits agglomerate at specific sites due to the “tip effect”, leading to loosen and nonuniform dendrites (Fig. 4a). In contrast, in the 20% EFA electrolyte, a compact and uniform zinc deposition layer is formed during the plating process (Fig. 4b).

In-situ optical microscope images of zinc deposition in a blank and b 20% EFA at 1.0 mA cm−2 (the testing temperature is 25 °C). Two kinds of electrolytes during plating/stripping at 30 mA cm−2 within 120 min: two-dimensional contour diagram of H2 production in c blank, d 20% EFA. In-situ FTIR patterns of e blank and f 20% EFA during plating/stripping process at 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2 (S-H, M-H, and W-H are strong, medium, and weak H-bonds, respectively.). COMSOL simulations about g, h electric field intensity and i, j Zn2+ concentration across the negative electrode surface.

The effectiveness of the Emim⁺-rich EDL in suppressing side reactions was further confirmed by Tafel and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) analyses. The addition of EFA shifts the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) potential from 0.09 V to −0.11 V (Supplementary Fig. 11f) and lowers the corrosion current density from 28.8 mA cm−2 to 8.13 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Meanwhile, the results of in-situ electrochemical Gas Chromatography (EC-GC) measurement and in-situ pH test directly confirm the inhibition effect of H2 evolution by EFA. After 120 min at 30 mA cm−2, 51.60 ppm H2 is detected in the blank electrolyte, which greatly exceeds 20% EFA (4.90 ppm) (Figs. 4c, d and Supplementary Fig. 12b). It’s worth noting that the pH value of 20% EFA is 3.97, which may be due to the hydrolysis of TFA− 21. Nonetheless, the in-situ formation of a stable SEI during zinc plating/stripping effectively protects the zinc surface, inhibiting further reactions with the electrolyte. Within 30 min at 5.0 mA cm−2, the pH value of the blank electrolyte increases significantly, from 4.98 to 5.45, which is higher than that of the 20% EFA (3.97 to 4.1) (Supplementary Fig. 12c–e). This much less pH variation and H2 evolution amount strongly indicate suppressed HER in the 20% EFA electrolyte system62. The dynamic interface microevolution of the zinc negative electrode during plating/stripping has been characterized by in-situ FTIR (Supplementary Fig. 13). The relative absorption intensity of v(SO3) (OTf−) shows a sustained negative drift. The consumption of the W-H bond plays a dominant role in the evolution of the H-bonds. These results reveal the fact that uncontrolled consumption of both active H2O and OTf− on the surface of the zinc negative electrode promotes severe H2 evolution and side reactions in the blank electrolyte during zinc plating/stripping, resulting in a rapid decline of the cell’s performance (Fig. 4e)63. However, the addition of EFA significantly reduces free H2O molecules at the electrode interface due to the absorption of Emim⁺. The conversion of W-H to S-H/M-H directly confirms the suppression of H2 evolution (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, the reversible decrease and increase in the absorption intensity of the v(SO3) (OTf−)during zinc plating/stripping indicate a dynamic and reversible process of desolvation/resolvation64. COMSOL Multiphysics simulations were employed to analyze the distribution of electric field intensity and Zn2+ concentration across the negative electrode surface. The 20% EFA electrolyte promotes the formation of a relatively positive electrostatic layer, due to the preferential adsorption of Emim⁺ cations, which effectively homogenizes the interfacial electric field distribution, as supported by electric field intensity simulations (Fig. 4g)65. Besides, the simulated Zn2+ concentration profiles reveal a more homogeneous ion distribution in the presence of EFA, indicating suppressed ion accumulation and depletion effects (Fig. 4i). Inversely, in blank electrolytes, a mass of Zn2+ accumulates at the tips of the protrusions, and an uneven electric field is observed, leading to the disordered growth of zinc dendrites during the plating/stripping process (Fig. 4h, j).

Electrochemical evaluation of Zn||VO2@VO full cells

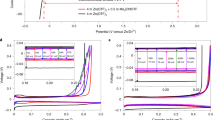

To evaluate the practical performance of the 20% EFA electrolyte, Zn||VO2@VO cells were constructed. The corresponding material characteristics are provided in Supplementary Fig. 14. Compared with blank electrolytes, the cyclic voltage (CV) of cells in 20% EFA shows similar redox peaks with a higher current signal, indicating a more beneficial electrochemical reactivity (Supplementary Fig. 15a)66. The rate capability of Zn||VO2@VO cells is exhibited in Fig. 5a, delivering discharge-specific capacities of 325.44, 302.34, 278.39, 248.36, 201.47, and 161.14 mAh g−1 at specific currents of 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, and 10.0 A g−1, respectively, in 20% EFA electrolyte. Upon reverting to 0.2 A g−1, a high capacity of 313.81 mAh g−1 was recovered, confirming their enhanced rate capability.

To rule out that the improved battery performance originates merely from the specific anion effect rather than the increased ionic concentration, the cycling ability of cells using the different electrolytes is systematically compared. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15b, at 2.0 A g−1, the cells with 20% EFA demonstrate significantly enhanced cycling stability (86.6% capacity retention, 500 cycles), whereas the blank and 3 M Zn(OTf)2 electrolyte exhibit rapid capacity decay with a capacity retention of about 22.2% and 68.5%, respectively. These results conclusively confirm the highly stable electrochemical performance of cells from the EFA-induced reconstruction of the solvation structure, H-bond, and EDL environment, rather than a trivial concentration increase of ions.

Besides, the stability and reliability of cells are also measured by performing self-discharge. Compared with the blank electrolyte (58.6%), the Zn||VO2@VO in 20% EFA retains 88.12% of its initial capacity after 24 h resting, suggesting the effectiveness of EFA for electrode protection (Fig. 5b)67. Static soaking and in-situ Raman experiments are conducted to systematically evaluate the vanadium dissolution inhibition effect of EFA on positive electrode materials. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, the blank electrolyte exhibits marked discoloration after 14 days, indicating a serious vanadium dissolution. In contrast, the 20% EFA electrolyte demonstrates only subtle color variation, suggesting effective vanadium dissolution inhibition. Similarly, in-situ Raman spectroscopy characterization reveals distinct differences in the vanadium dissolution behavior of VO2@VO between the electrolyte systems. In the process of charge-discharge cycling, the blank electrolyte shows characteristic vibration of δ(-O-V-O-V-, 150 cm−1) and δ(V = O, 260 cm−1), indicating a large amount of vanadium is dissolve from the framework into the electrolyte, which ultimately will lead to the fading of cell’s capacity (Fig. 5c). Differently, the 20% EFA shows no detectable vanadium-related vibrational signatures, confirming a suppressed vanadium dissolution (Fig. 5d). The stability of VO2@VO in the 20% EFA is further demonstrated in the long-cycle performance test. After 3000 cycles, the Zn||VO2@VO cell in 20% EFA delivers a high-capacity retention of 75% at 10.0 A g−1 (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 17a, b). In contrast, cells using blank electrolyte suffered from rapid capacity decay, with discharge capacity nearly disappearing after 2000 cycles. Furthermore, a 4 × 4 cm pouch cell is fabricated to evaluate the effectiveness of EFA on practical application. Following activation and stabilization, the cell, with a high active mass loading of approximately 10.0 mg cm−2, delivered a stable capacity of 202.1 mAh g−1 and maintained 132 mAh g−1 after 500 cycles at 1.0 A g−1 (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 17c). Furthermore, the pouch cell delivered sufficient power to successfully operate a mobile phone, demonstrating its practical viability. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 17d and 18 and Supplementary Table 1, the pouch cell demonstrates a considerable energy density.

Effective antifreeze Zn2⁺ solvation chemistry

According to the Hofmeister series, TFA⁻, as a typical chaotropic anion, disrupts the intrinsic H-bond network of H2O, thus significantly depressing the freezing point of the electrolyte. Meanwhile, the TFA− and OTf− exhibit Hofmeister series compliance, with their chaotropic potency demonstrating a gradient enhancement. This gradient combination establishes an anion-rich solvation shell ([Zn(H2O)4.9(TFA−)0.75(OTf−)0.35]+), favoring the deposition of Zn2+. The regulation mechanism of TFA− on the H-bond of bulk electrolyte is shown in Fig. 6a. The restructuring of H-bond networks in the electrolyte, driven by highly chaotropic anions, significantly decreases its freezing point. As shown in Fig. 6b, for blank electrolytes, an exothermic peak at −19.18 °C is ascribed to the crystallization of the electrolyte. The frozen electrolyte will lead to a separation electrolyte/electrode interface, resulting in an assignable interface impedance. Besides, the limiting ion migration does not provide sufficient ion conductivity to support effective cycling at low temperatures (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 19a). With the addition of the EFA, the original H-bond network corresponding to the H2O is broken, causing a greatly lower freezing point of the 20% EFA electrolyte (−53.21 °C) (Fig. 6b) and providing a high ion conductivity of about 2.2 1 mS cm−1 at −40 °C (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 19b). Therefore, the low freezing point ensures that the cell in 20% EFA electrolytes can operate stably at low temperatures. Besides, the activation energy (\({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\)) of 20% EFA is about 33.34 kJ mol−1, lower than that of the blank electrolyte (55.58 kJ mol−1), indicating a high temperature independence (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 19c–e and Supplementary Table 2)68,69.

a Schematic of chaotropic anions regulating H-bond structure in bulk electrolyte. b DSC curves (−60 to 0 °C). c Ionic conductivity at low temperatures. d Arrhenius curves and activation energies. e, f Symmetric cell plating/stripping behavior at −30 °C and −40 °C in 20% EFA. g Zn||VO2@VO performance across temperatures. h Long-term cycling at −40 °C. i Comparison with previously reported low-temperature batteries.

As shown in Fig. 6e, f and Supplementary Fig. 20a, b, the zinc negative electrode in the 20% EFA electrolyte exhibits high reversibility at low temperatures. The cell demonstrates a long zinc plating/stripping life over 13,000 h at −30 °C and 0.1 mA cm−2, 0.1 mAh cm−2, along with a lifetime of 6692 h even at −40 °C. Supplementary Fig. 20c–e presents the practical applications-relevant zinc plating/stripping behavior of symmetric cells under higher current density and low-temperature. At −30 °C, the cell maintains stable operation for over 1600 h and 220 h at 0.5 mA cm−2, 0.5 mAh cm−2, and 1.0 mA cm−2, 1.0 mAh cm−2, respectively. Even at −40 °C, the cell delivered a stable cyclability for nearly 100 h under 0.5 mA cm−2, 0.5 mAh cm−2. Moreover, the Zn||Cu cell achieved an average CE of 99.6% over 300 cycles at −40 °C (0.1 mA cm−2, 0.1 mAh cm−2). This highly stable CE, combined with the long stripping/plating life of Zn||Zn symmetric cells, collectively demonstrates that our electrolyte enables improved reversibility of zinc plating/stripping even under low-temperature conditions (Supplementary Fig. 21).

To evaluate the temperature adaptability of hybrid electrolytes, the performance of Zn||VO2@VO cells in 20% EFA is tested at various temperatures. The full cell exhibited average discharge capacities of approximately 338.81, 230.10, 180.98, 120.90, and 89.77 mAh g−1 at 25, −10, −20, −30, and −40 °C, respectively. Upon returning to 25 °C, the capacity recovered to 317.77 mAh g−1 at 0.2 A g−1 (Fig. 6g). More significantly, even at −40 °C, the Zn||VO2@VO delivers a long cycling life over 3500 cycles along with almost no capacity degradation at 0.2 A g−1 (Fig. 6h). The comparison between this work and reported similar literature is shown in Fig. 6i and Supplementary Table 3. The phase transformation of VO2@VO after cycling at −40 °C was verified by ex-situ XRD measurement. When the potential of the positive electrode reaches low voltage, a diffraction peak located at 12.6° has been observed, which can be ascribed to the formation of Zn3(OH)2V2O7·2H2O (ZVO) (Supplementary Fig. 22). However, the peak of ZVO gradually disappears during the charging process, demonstrating a reversible transformation. This result can be attributed to Emim⁺ absorption on the VO2@VO surface, ensuring high positive electrode stability during prolonged cycling. To further verify the practical application of 20% EFA at low temperatures, the performance of the pouch cell at −30 °C was tested. It exhibits an initial capacity of 191.34 mAh g−1 and maintains stable operation over cycling at 0.1 A g−1 (Supplementary Fig. 23). The above analysis demonstrates this hybrid electrolyte’s effectiveness in low-temperature applications.

In summary, we have achieved a full-component electrolyte design by simply introducing a chaotropic ionic liquid (IL, EMIM⁺-TFA−) into Zn2+-OTf−-H2O electrolyte, enabling effective antifreeze Zn2+ solvation chemistry (−40 °C) and stable cycling in aqueous zinc-based batteries. Guided by their adjacent positions in the Hofmeister series, TFA− and OTf− anions are selected as cooperative anionic components and paired with bulky IL cations to construct a gradient chaotropic Zn2+ electrolyte, thereby eliminating the need for additional antifreeze co-solvents. A H2O-poor and anion-rich interfacial environment is established at the zinc negative electrode, which effectively suppresses parasitic reactions, regulates uniform zinc deposition, and ensures rapid Zn2+ transport because of the strong coordination ability of TFA−. Furthermore, the gradient chaotropic Zn2+ electrolyte formulation establishes a rapid ion transport network that supports stable positive electrode cycling, primarily by suppressing the dissolution of transition metals from the positive electrode. Thus, the proposed electrolyte formulation delivers enhanced zinc plating/stripping performance in both Zn||Zn symmetric cells and full cells under ambient conditions and high current densities, reflecting its high ionic conductivity. At 0.1 mA cm−2 and 0.1 mA cm−2, the assembled Zn||Zn symmetric cells also exhibit stable zinc plating/stripping behavior for over 13,000 and 6692 h at −30 °C and −40 °C, respectively. Furthermore, at −40 °C, the Zn||VO2@VO full cell maintains nearly a stable discharge capacity over 3500 cycles without noticeable degradation at 0.2 A g−1. This gradient chaotropic anion architecture could provide a multifunctional design paradigm for advanced zinc batteries, simultaneously ensuring operational safety, freeze-resistant capability, accelerated ion transport kinetics, and enhanced cycling stability.

Methods

Electrolyte preparation

A 2 mol L−1 blank electrolyte was prepared by dissolving zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate (Zn(OTf)2, 98%, Bide Pharm Co., Ltd.) in deionized water (H2O). Then, mixing 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate ([Emim][TFA], 98%, Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd.) with H2O in volume ratios of 1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6, 7:3, and 9:1, respectively, to form homogeneous solutions. Zn(OTf)2 was subsequently added to these solutions, resulting in a series of electrolytes, each with a concentration of 2 mol L−1. These were denoted as 10% EFA, 20% EFA, 30% EFA, 40% EFA, 70% EFA, and 90% EFA corresponding to the respective [Emim][TFA] contents. Besides, to verify that a gradient chaotropic anions (rather than a single type) is crucial for optimizing the solvation structure and achieving enhanced performance, substituting EmimTFA with 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([Emim][OTf], denoted as ETF, 98%, Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd.). In addition, the volume ratio of ETF and H2O is 2:8.

Preparation of VO2@VO positive electrode material

2.4 g V2O5 (99%, Aladdin Scientific Co., Ltd.) and 3.6 g H2C2O4·2H2O (99.5%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) were dissolved in 75 mL H2O and stirred continuously at 70 °C for 2 h, and subsequently transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 180 °C for 10 h. After cooling to 25 °C, the precipitate was collected and washed several times with ethanol and deionized water, followed by drying at 80 °C for 12 h.

Electrode preparation

For the coin cell, a slurry was prepared by mixing VO2@VO, acetylene black (99.9%, Canrd Technology Co. Ltd.), and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF 5130, Mw about 1100000, Canrd Technology Co. Ltd.) in a weight ratio of 7:2:1, then dispersing the mixture in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP, 99%, Aladdin Scientific Co., Ltd.). This slurry was subsequently uniformly coated onto a titanium (Ti) foil (10 μm in thickness, 99.9%, Tianjin EVS Chemical Technology Co., Ltd.) to form a single-sided coating using a heating-type cast coater (Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co., Ltd., MSK-AFA-HC100) and dried at 80 °C for 12 h. The dried electrode was then punched into disks with a diameter of 10 mm using a precision disc cutting machine (Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co. Ltd., MSK-T10). The mass loading of VO2@VO was maintained at 1.0 mg cm−2. For the pouch cell, the same slurry was applied onto a Ti foil (4 cm × 4 cm), achieving a higher VO2@VO mass loading of 10.0 mg cm−2.

Cell assembly

Symmetric and asymmetric cells were configured in CR2025-type coin cells. The assembly consisted of two working electrodes separated by a single layer of glass fiber filter (Whatman GF/D, 16 mm in diameter, 675 μm in thickness, and an average pore size of 2.7 μm), with a stainless steel spacer (1.0 mm thickness) and a spring-loaded plunger (stainless steel, 1.5 kN constant force) completing the stack. In the Zn||Zn cell, two pieces of zinc foil with a diameter of 12 mm (100 μm thickness, 99.9%, Haoxuan Metal Materials Co., Ltd.) are used as electrodes. A volume of 90 μL of electrolyte was injected into each cell. For Zn||Cu or Zn||Ti cells, Cu foil (a diameter of 12 mm, 40 μm thickness, 99.9%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) or Ti foil (a diameter of 12 mm, 10 μm in thickness, 99.9%, Tianjin EVS Chemical Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to replace one side of the zinc foil. For Zn||VO2@VO full cell, the zinc foil is the negative electrode, VO2@VO as the positive electrode, and the volume of electrolyte is 100 μL. The pouch cell was assembled by stacking one piece of zinc foil (a thickness of approximately 13 μm, 99.9%, Haoxuan Metal Materials Co., Ltd.) and one piece of single-sided coated positive electrodes (mass loading of 10.0 mg cm−2) with a glass fiber filter (OLEGEEINO GF/A, 280 μm in thickness and an average pore size of 1.63 μm). The stacked assembly was vacuum-sealed in an aluminum-laminated pouch bag, leaving one port open for electrolyte injection. A volume of about 0.6 mL of electrolyte was injected through the open port, then fully sealed under vacuum. The cells were then rested for 12 h to ensure sufficient wetting. During cycling, an external pressure of 1.0 MPa was applied to the pouch cells using a fixture plate.

Electrochemical characterizations

Electrochemical charge/discharge tests were carried out on the Neware battery testing system (NEWARE, Shenzhen, China). The assembled pouch cells and coin cells were activated to 3 formation cycles at 0.5 A g−1 in the voltage range of 0.2 ~ 1.6 V, before proceeding to the long-term cycling tests. All electrochemical cycling tests were carried out in a climate chamber (Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co. Ltd., MSK-TE906-100P-70-5).

CE data for the Zn||Cu cell were obtained using a battery tester (LAND CT2000A), with a cut-off voltage set as 0.5 V. LSV was conducted for the Zn||Ti cell at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 and the voltage window from 4.0 to −1.0 V, while the Tafel plot was measured using a Zn||Zn symmetric cell, both performed on the Autolab electrochemical workstation (PGSTA T302N). The ionic conductivity (σ) and desolvation activation energy (Eₐ) of the electrolytes were evaluated via EIS using an Autolab PGSTA T302N electrochemical workstation. Measurements were carried out in potentiostatic mode with a sinusoidal amplitude of 10 mV. The frequency range was scanned from 105 Hz to 10−2 Hz, with 10 data points collected per frequency decade. Before each measurement, the cell was stabilized at the open-circuit potential (OCP) for at least 2 h until the voltage change was less than 1 mV per minute. The test of ionic conductivity was fabricated in a symmetric configuration comprising two stainless steel spacers, a glass fiber separator, and the electrolyte and calculated according to the following formula:

where L (cm) is the thickness; A (cm−2) is the electrode contact area, and R is the bulk resistance value. The Zn||Zn cell was used to perform the \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\), the calculation based on the Arrhenius equation:

Where \({R}_{{{{\rm{ct}}}}}\) denotes the charge transfer resistance, A is the preexponential constant, T is the absolute temperature, and R is the standard gas constant.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) data and DRT were tested on the Autolab workstation (PGSTA T302N). DRT were calculated from the EIS results in conjunction with the DRT-TOOLS toolbox, developed by Professor Francesco Ciucci’s research group. The toolbox is freely available under the GNU license and can be accessed at: https://sites.google.com/site/drttools/.

Preparation and characterization of the ex-situ samples

To investigate the electrode surface chemistry after cycling, the cells were disassembled in an air atmosphere. The cycled electrodes were carefully harvested and rinsed three times with H2O to remove residual electrolyte salts. Subsequently, the samples were dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 2 h. The dried electrode samples were then transferred from the vacuum oven to the instrument using a dedicated airtight transfer vessel. All characterization test analysis was conducted at a constant temperature of 25 ± 1 °C.

Material characterizations

Material were characterized: Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra were achieved on a Thermo Fisher Nicolet Antaris II spectrometer over the range of 4000–500 cm−1 (zinc selenide (ZnSe) trapezoid prism serving as the reflective element for in situ measurements); Raman spectroscopy was conducted using a HORIBA LabRAM HR Evolution system equipped with a 532 nm laser; NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV II-600 MHz instrument; XRD data were collected via a D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Bruker AXS); Morphological analysis was carried out using a Tescan MAIA3 XMU field-emission SEM; The composition of the solid electrolyte interface (SEI) was examined via high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, JEOL F200). The phase transition temperature (Tt) of the samples was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) on a Mettler Toledo DSC 3+ instrument. Chemical states were probed by XPS on a Thermo Fisher K-Alpha spectrometer using Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV). Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) was conducted on a PHI nanoTOF II system (ULVAC-PHI, Japan) with a 30 keV Bi+ primary ion source. Data acquisition covered rectangular regions of 400 × 400 μm. The Ar⁺ sputtering rate, calibrated against a SO2 standard, was 0.83 ± 0.05 nm/s under consistent operational conditions. Gas chromatography (Ceaulight, GC-7920) was used to monitor gas production during the zinc plating/stripping process in electrolytes. The direct current to direct current (DC-DC) converter has dimensions of 25 × 18 mm, with an input voltage range of 0.9V–5 V, an output voltage of 5 V, and an output current of 600 mA. The X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) were explored by EasyXAFS300+ and analyzed using the ATHENA software package. SAXS and 2D grazing incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (2D GIWAXS) data were collected on Xenocs Xeuss 2.0. and Xenocs Xeuss 2.0. respectively.

Density functional theory (DFT) computations

The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package was employed to compute the adsorption and binding energies. Within this framework, electron interactions for both core and valence states were treated using the projector augmented wave approach. The exchange-correlation effects were accounted for by the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional. A plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV was used to expand the wavefunctions, and Brillouin zone integration was performed at the k-point. The binding energy between Zn2+ and various solvents and ions (adsorption energy between zinc surface and various solvents and ions) was determined using the following equation:

where E(a-b), E(a), and E(b) are the total electronic energies of Zn2+ binds with a solvent molecule or ions (solvent molecule or ions absorb on the zinc surface), Zn2+ (zinc surface), and solvent molecule or ions, respectively. The calculation parameters and the corresponding initial and final configurations are in Supplementary Data 5–16.

All relevant molecular models were structurally optimized in the Gaussian software and were performed at the DFT level using the B3LYP function combined with the 6–311 G(d,p) basis set. Subsequent electronic structure analysis, including Electrostatic Potential (ESP) mapping and Frontier Molecular Orbital calculations, was executed on the optimized geometries utilizing the Multiwfn program. Visualization of molecular structures, electron density isosurfaces, and ESP results was facilitated by the VMD software package. The calculation parameters and the corresponding initial and final configurations are in Supplementary Data 21–26.

Molecular dynamics simulations

All MD simulations in this study were carried out using the open-source software GROMACS 2020.6. The MD simulations were performed in 2 M Zn(OTf)2 electrolytes, both with and without EFA co-solvents. In the initial stages of the simulation, the steepest descent algorithm was utilized to reduce the total energy of the system and avoid excessively short interatomic distances in the starting configuration. Following this, an NPT ensemble was used for 10 ns of equilibration, and the leapfrog algorithm was applied with a time step of 2 fs. Temperature was maintained at 298.15 K using the V-rescale algorithm, which had a relaxation time of 0.1 ps. The total simulation duration was 5 ns, during which the density distributions of all components were analyzed statistically. The calculation parameters and the corresponding initial and final configurations in Supplementary Data 1–4 and Supplementary Data 17–20.

COMSOL simulation

To simulate the spatial variation of the electric field and the corresponding ion concentration at the interface, the current module and the tertiary current distribution module in COMSOL Multiphysics were employed. A simplified battery model was established to account for the distinctive properties of the zinc negative electrode and the SEI. In the 2D model, the overall size was set as 8 μm in length and 7 μm in width, with a semicircular protrusion at the bottom representing the interface and a radius of 0.5 μm. Smaller circles within this structure represent the organic and inorganic components, each with a radius of 0.2 μm. For the boundary conditions in the current module, one terminal was assigned a voltage of 0.03 V, while the other terminal was grounded. Within the tertiary current-distribution interface, the concentration of Zn2+ was specified as 2 mol·L–1. A voltage of 0.1 V was applied to the positive electrode, accompanied by an average current density of 10 A m−2, while the negative electrode was held at a constant potential of 0 V.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are presented in the manuscript and Supplementary Information, or are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, Z. et al. In-situ construction of solid electrolyte interphases with gradient zincophilicity for wide temperature zinc ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2404108 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. An advanced Ca/Zn hybrid battery enabled by the dendrite-free zinc anode and a reversible calcification/decalcification NASICON cathode. Sci. Bull. 68, 56–64 (2023).

Qu, G. et al. A temperature self-adaptive electrolyte for wide-temperature aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2400370 (2024).

Zhao, M. et al. Ordered zinc electrodeposition from single-crystal units to polycrystalline stacking within solid-electrolyte interphase in battery anodes. Nat. Commun. 16, 2843 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Amorphous heterostructure derived from divalent manganese borate for ultrastable and ultrafast aqueous zinc ion storage. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205794 (2023).

Chen, K. et al. Correlating the solvating power of solvents with the strength of ion-dipole interaction in electrolytes of lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312373 (2023).

Tamtögl, A. et al. Motion of water monomers reveals a kinetic barrier to ice nucleation on graphene. Nat. Commun. 12, 3120 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Comprehensive understandings of hydrogen bond chemistry in aqueous batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308628 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Multifunctional interface layer constructed by trace zwitterions for highly reversible zinc anodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202411884 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. Zinc chemistries of hybrid electrolytes in zinc metal batteries: from solvent structure to interfaces. Adv. Mater. 36, 2411802 (2024).

Qu, Y.-F. et al. Constructing 3D crosslinked macromolecular networks as a highly efficient interface layer for ultra-stable Zn metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 37, 2413370 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Anion-cation synergy enables reversible seven-electron redox chemistry for energetic aqueous zinc-iodine batteries. Nano Energy 138, 110884 (2025).

Hu, Z. et al. Reconstructing hydrogen bond network enables high voltage aqueous zinc-ion supercapacitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309601 (2023).

Lin, L. et al. High-entropy aqueous electrolyte induced formation of water-poor Zn2+ solvation structures and gradient solid-electrolyte interphase for long-life Zn-metal anodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202425008 (2025).

Hu, B. et al. Reconfiguring the electrolyte network structure with bio-inspired cryoprotective additive for low-temperature aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2401470 (2024).

Xu, P. et al. In-situ solid electrolyte interface via dual reaction strategy for highly reversible zinc anode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407909 (2024).

Shi, M. et al. Super hydrous solvated structure of chaotropic Ca2+ contributes superior anti-freezing aqueous electrolytes and stabilizes the Zn anode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407659 (2024).

Xiao, T. et al. All-round ionic liquids for shuttle-free zinc-iodine battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318470 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. A Janus-type quasi-solid-state electrolyte enabling dual-ion relay for long lifespan of nonaqueous zinc batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 18, 8618–8630 (2025).

Yu, L. et al. Ionic liquid “water pocket” for stable and environment-adaptable aqueous zinc metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210789 (2023).

Wen, J. et al. Enhancing Zn-metal anode stability: key effects of electrolyte additives on ion-shield-like electrical double layer and stable solid electrolyte interphase. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2314347 (2024).

Lv, Y. et al. Synergistic anion-cation chemistry enables highly stable Zn metal anodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 8523–8533 (2025).

Chen, Z. et al. Fluorinated-oligomeric ionic liquids for high-performance wide-temperature solid zinc batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 18, 3296–3304 (2025).

Zhong, M. et al. Zinc-coordinated imidazole-based ionic liquid as liquid salt for all-temperature aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2316788 (2024).

Xiong, T. et al. Design and structure of electrolytes for all-weather aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2421240 (2025).

Qiu, M. et al. Tailoring water structure with high-tetrahedral-entropy for antifreezing electrolytes and energy storage at −80 °C. Nat. Commun. 14, 601 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Solvation structures in aqueous metal-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2202068 (2022).

Cecchi, T. et al. Retention mechanism for ion-pair chromatography with chaotropic reagents. J. Chromatogr. A 1216, 1789–1797 (2009).

Zhang, Q. et al. Chaotropic anion and fast-kinetics cathode enabling low-temperature aqueous Zn batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2704–2712 (2021).

Gao, G. et al. Customizing the water-scarce, zinc ion-rich Helmholtz plane of a zinc anode for Ah-scale Zn metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 7850–7859 (2024).

Jiang, L. et al. Electric double layer design for Zn-based batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 62, 102932 (2023).

Xu, D. et al. Chelating additive regulating Zn-ion solvation chemistry for highly efficient aqueous zinc-metal battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402833 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Electrolyte design for reversible zinc metal chemistry. Nat. Commun. 16, 71 (2025).

Yang, Z. et al. Amphiphilic electrolyte additive as an ion-flow stabilizer enables superb zinc metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 3443–3453 (2024).

Chang, L. et al. High-entropy solvation chemistry towards affordable and practical Ah-level zinc metal battery. Nat. Commun. 16, 6134 (2025).

Ren, H. et al. Tailoring water-in-DMSO electrolyte for ultra-stable rechargeable zinc batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202423302 (2025).

Li, Q. et al. Designing a bridging solvation structure using recessive solvents for high energy density aqueous zinc-ion batteries with 88% depth of discharge zinc rechargeability. Energy Environ. Sci. 18, 1489–1501 (2025).

Wang, N. et al. High-entropy deep eutectic solvent achieves ultra-low polarization zinc anode chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202502761 (2025).

Tang, J. et al. Neighboring alkenyl group participated ether-based electrolyte for wide-temperature lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 16, 7917 (2025).

Meng, Q. et al. Attenuating water activity through impeded proton transfer resulting from hydrogen bond enhancement effect for fast and ultra-stable Zn metal anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2302828 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Zincophilic and hydrophobic groups of surfactant-type electrolyte additive enabled stable anode/electrolyte interface toward long-lifespan aqueous zinc ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 70, 103500 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Facet-governed Zn homoepitaxy lattice potential regulation. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 5563–5575 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Multifunctional dual-metal-salt derived ternary eutectic electrolyte for highly reversible zinc ion battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402186 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Constructing robust interphase via anion-enhanced solvation structure for high-voltage fast charging sodium metal batteries. Nano Energy 138, 110913 (2025).

Meng, Y. et al. Robust bilayer solid electrolyte interphase for Zn electrode with high utilization and efficiency. Nat. Commun. 15, 8431 (2024).

Wu, M. et al. Harnessing ion-dipole interactions for water-lean solvation chemistry: achieving high-stability Zn anodes in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407439 (2024).

Cai, D.-Q. et al. Understanding the structure-activity relationship of additives for durable Zn metal batteries: a case study of aromatic molecules. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 8349–8359 (2024).

Li, H. et al. A bio-inspired trehalose additive for reversible zinc anodes with improved stability and kinetics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310143 (2023).

Huang, J. et al. Interfacial biomacromolecular engineering toward stable Ah-level aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406257 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Highly reversible Zn metal anode securing by functional electrolyte modulation. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400872 (2024).

Ma, G. et al. Organic cations texture zinc metal anodes for deep cycling aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2408287 (2024).

Peng, Z. et al. Water-shielding electric double layer and stable interphase engineering for durable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 16, 4490 (2025).

Luo, J. et al. Stable zinc anode solid electrolyte interphase via inner Helmholtz plane engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 6471 (2024).

Huang, R. et al. Dual-anion chemistry synchronously regulating the solvation structure and electric double layer for durable Zn metal anodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 3179–3190 (2024).

Xu, W. et al. Fluoride-rich, organic-inorganic gradient interphase enabled by sacrificial solvation shells for reversible zinc metal batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22456–22465 (2023).

Meng, C. et al. A eutectic electrolyte for an ultralong-lived Zn//V2O5 cell: anin situgenerated gradient solid-electrolyte interphase. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 3587–3599 (2023).

Ma, G. et al. Reshaping the electrolyte structure and interface chemistry for stable aqueous zinc batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 47, 203–210 (2022).

You, S. et al. Achieving highly stable Zn metal anodes at low temperature via regulating electrolyte solvation structure. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402245 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Facet-termination promoted uniform Zn (100) deposition for high-stable zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301517 (2023).

Ma, C. et al. Dual-parasitic effect enables highly reversible Zn metal anode for ultralong 25,000 cycles aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 24, 4020–4028 (2024).

Zong, Q. at al. Tailoring the whole deposition process from hydrated Zn2+ to Zn0 for stable and reversible Zn anode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409957 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. Superhydrophobic and robust hetero-metal-polymer hybrid interphase enables deep-cycling zinc metal anodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 9611–9622 (2024).

Yu, X. et al. Deciphering multi-dimensional interfacial mechanisms via organic cosolvent engineering for sustainable zinc metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 16, 3820 (2025).

Yu, X. et al. Unlocking dynamic solvation chemistry and hydrogen evolution mechanism in aqueous zinc batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 17103–17113 (2024).

Tan, H. et al. Boosting zinc anode durability through synergistic inner Helmholtz plane and interfacial electric field regulation. Sci. Bull. 69, 2025–2029 (2024).

Song, W. et al. Insight into sulfur-containing zwitter-molecule boosting Zn anode: from electrolytes to electrodes. Adv. Sci. 11, 2400094 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Transforming zinc-ion batteries with DTPA-Na: a synergistic SEI and CEI engineering approach for exceptional cycling stability and self-discharge inhibition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409642 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Regulating interfacial reaction through electrolyte chemistry enables gradient interphase for low-temperature zinc metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 5443 (2023).

Ma, D. et al. An electrochemically driven hybrid interphase enabling stable versatile zinc metal electrodes for aqueous zinc batteries. Nat. Commun. 16, 4817 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52425207 and 52171198 received by S.C.), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L245007 received by S.C.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (buctrc202104 received by S.C.). Thank the support by the Australian Research Council through the ARC Discovery Project (DP230101579 received by G.W.). We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility of BL06B for the assistance on experimental measurements. We thank the X-ray & Elemental Facility, Mark Wainwright Analytical Center, UNSW Sydney, for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. was responsible for conducting the experimental work and writing the manuscript. S.Z. provided crucial experimental insights and carried out the DFT simulations. The COMSOL simulations were performed by H.X. Material characterization was assisted by X.W. and X.H. Q.Y. provided the theoretical guidance. Y.C., G.W., and S.C. participated in the results discussion and manuscript revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chaoji Chen, and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Zhao, S., Xu, H. et al. Gradient chaotropic regulation of Zn2+ solvation chemistry for low-temperature zinc metal batteries. Nat Commun 17, 736 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67426-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67426-9