Abstract

Multimorbidity of cardiometabolic disease (CMD) and cancer is a growing but understudied global challenge in an aging world. Here, we perform multistate analysis in 429,555 UK Biobank participants to investigate transition patterns, identify multiomics signatures, and construct prediction models from baseline to single and multiple morbidities. During a median follow-up of 15 years, 105,903 participants develop single morbidity and 15,088 develop multimorbidity of CMD and cancer. Participants with multimorbidity have a 13%-33% higher mortality probability than those healthy or with single morbidity. In individuals living with multimorbidity, the development of CMD before cancer presents a higher mortality risk than the reverse order. Distinct and shared multiomics signatures are identified, with proteomics scores outperforming other omics in predicting disease trajectories (ΔC-statistic vs. base model: 0.03–0.14). This study reveals distinct transition patterns in CMD-cancer multimorbidity cluster and develops potentially useful prediction tools for supporting risk management if externally validated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multimorbidity is a major health concern worldwide due to the fast pace of population aging1. Approximately 30% of individuals aged 45–65 years live with 2 or more chronic diseases, and over 80% have multiple chronic conditions among those aged 80 or more2. Compared to those with a single chronic condition, individuals with multimorbidity are more likely to experience significant decreases in physical and mental capacity and face a higher risk of premature death1. However, current studies mainly focus on disease-specific care, leaving a gap in understanding the trajectories and interplay of multiple chronic diseases simultaneously3. Further understanding and early prediction of disease trajectories in a multimorbidity cluster are important for improving healthcare systems and promoting precision prevention and intervention strategies.

Cardiometabolic diseases (CMD), including cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D), and cancer are the most prevalent and leading causes of death among chronic diseases4. Approximately 30–50% of cancer survivors had concurrent morbidities of CMD2. Previous studies have suggested that the development between CMD and cancer was bidirectional and they shared common risk factors (e.g., aging and obesity) as well as pathophysiological pathways (e.g., inflammation and hypoxia)5,6. However, how coexisting diseases develop over time within a multimorbidity cluster of CMD and cancer, and whether mortality risk varies by morbidities or multimorbidity with different temporal orders remain to be investigated.

Among aging diseases, diagnosis is commonly delayed by months or even years from the initial onset of pathologies or symptoms7. Recent studies suggested that multiomics profiles with comprehensive information relevant to human health conditions and physiological states have shown moderate to good performance for the occurrence of each individual disease up to 10–15 years before the onset8,9,10. However, among elderly populations with high multimorbidity risk, single disease prediction is still insufficient for providing personalized healthcare and optimal prognosis. Whether multiomics profiles could effectively capture the characteristics of disease transitions and achieve improved predictions for disease trajectories requires investigation.

In this work, we characterize disease trajectories from health to chronic morbidity, multimorbidity, and mortality within the CMD and cancer multimorbidity cluster, assess mortality risk across morbidities and multimorbidity with different temporal orders, and investigate multiomics signatures associated with disease transitions and develop machine learning-based omics scores to assess their predictive performance for disease trajectories within this multimorbidity cluster.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 429,555 participants were included for analysis (Fig. S1). The median age of the participants was 55.9 years (standard deviation, 8.1). Among them, 194,907 (45.4%) were male, and 404,461 (94.2%) were White (Supplementary Table 1). During a median follow-up of 14.5 (interquartile range, 13.5–15.3) years, 64,990 individuals developed CMD (including a total of 27,114 T2D cases and 54,523 CVD cases), and 71,089 developed cancer. Moreover, 49,902 individuals developed single CMD morbidity without subsequent cancer diagnosis, 56,001 developed single cancer morbidity without subsequent CMD diagnosis, and 15,088 participants developed multimorbidity of CMD and cancer. Individuals diagnosed with multimorbidity tended to be male and older compared with those who had CMD or cancer as a single diagnosis. During the follow-up, 6035 (Transition V, 10.7%) of 56,651 individuals with CMD and 11,062 (Transition VII, 17.2%) of 64,340 individuals with cancer as the first diagnosis died, and 6749 (Transition IV, 11.9%) of those with CMD and 8339 (Transition VI, 13.0%) of those with cancer further developed multimorbidity. Among participants with multimorbidity, 2435 (Transition VIII, 36.1%) of 6749 individuals with CMD-cancer and 2640 (Transition IX, 31.7%) of 8339 individuals with cancer-CMD died afterward (Fig. 1).

Transitions include: I, baseline to cardiometabolic disease; II, baseline to cancer; III, baseline to death; IV, cardiometabolic disease to cancer; V, cardiometabolic disease to death; VI, cancer to cardiometabolic disease; VII, cancer to death; VIII, cardiometabolic disease to cancer to death; IX, cancer to cardiometabolic disease to death. CA, cancer; CMD, cardiometabolic disease.

Transition probabilities and prognostic outcomes

Participants with multimorbidity had a 28–33% higher probability of death compared to healthy individuals, with a loss of 5.0–5.3 years in mean survival time, and an 11–23% higher probability of death compared to those with single morbidity, with a loss of 2.4–3.6 years in mean survival time (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Dataset 1). A rapid rise in the probability of developing multimorbidity was observed approximately 5 years after the initial diagnosis of either CMD or cancer morbidity. Compared to those first diagnosed with CMD, participants initially diagnosed with cancer had an 8% higher probability of death at 5 years, with the difference narrowing at 10 and 15 years, and a 3% higher probability of developing multimorbidity at 15 years. Within the multimorbidity of CMD and cancer, developing CMD first presented a 1–2% higher mortality risk and a greater loss of 0.3 years in survival time compared to developing cancer first (all p < 0.01).

a Transition probabilities from baseline to first disease or death, first disease to second disease or death, and second disease to death during follow-up (n = 429,555 individuals). Data are presented as estimated transition probabilities and 95% confidence intervals in bar plots. The transition probabilities were calculated using a multistate model adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, employment status, education level, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, diet quality score, sleep duration, BMI, family history of T2D, CVD, and cancer, medication use for CMD and cancer, and participation in cancer screening. T-tests were used to compare the transition probabilities. p was calculated with a 2-sided test. The detailed results are shown in Supplementary Dataset 1. b Restricted mean survival time of morbidities or multimorbidity with different temporal orders (n = 429,555 individuals). The curves represent survival estimates, and the shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Restricted mean survival time was calculated from the time of diagnosis of the last disease within a fixed follow-up period of 15 years. c The proportions of subsequent events across subtypes of cardiometabolic disease or cancer morbidity. CA, cancer; CAD, coronary artery disease; CMD, cardiometabolic disease; HF, heart failure; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

After propensity score matching, baseline characteristics became more comparable across the 5 states, although minor differences remained between the healthy, morbidity, and multimorbidity groups. Importantly, comparability improved significantly between the 2 single morbidity groups (single CMD and cancer morbidity groups) and between the 2 multimorbidity groups (CMD-cancer and cancer-CMD multimorbidity groups) (Supplementary Table 2). The mean survival times across CMD morbidity, cancer morbidity, CMD-cancer multimorbidity, and cancer-CMD multimorbidity remained consistent compared with the primary result (Fig. S2).

Subgroup analysis by CMD and cancer types

For specific CMD subtypes, participants with stroke and heart failure had a higher probability of direct death, while the probability of further developing cancer was similar across participants with different CMD subtypes (Fig. 2c). For high-survival-rate cancers, 11% of participants with prostate cancer died directly, while 18% further developed CMD, higher than that observed in skin and breast cancers. Among low-survival-rate cancers, 72% of participants with pancreatic cancer experienced direct mortality, much higher than that in people with other cancers; 25% of participants with liver cancer further developed CMD, followed by those with pancreatic cancer (19%) and esophageal cancer (17%). Participants with low-survival-rate cancers generally had a 6% higher probability of subsequently developing CMD than those with high-survival-rate cancers (Fig. S3 and Supplementary Dataset 1). The development of CMD before cancer showed a 7% lower probability of death compared to the development of cancer before CMD in the high-survival-rate cancer subgroup, while showing a 9% higher probability of death in the low-survival-rate cancer subgroup.

Among participants who initially developed either benign or in situ tumors or malignant tumors, the probabilities of subsequently developing CMD were similar (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Dataset 1). In the benign or in situ tumor subgroup, developing CMD before cancer presented a slightly lower probability of mortality compared to the reverse order. In contrast, in the malignant tumor subgroup, the onset of CMD before cancer showed a 3% higher probability of death than the reverse sequence. Similar results were observed across mild and severe CMD subgroups (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Dataset 1). Specifically, the probability of developing cancer remained similar among participants who first developed mild or severe CMD. In the severe CMD subgroup, multimorbidity of CMD to cancer had an 8% higher probability of death compared to the reverse order, while in the mild CMD subgroup, the probabilities were similar. Furthermore, in the subgroup of both severe CMD and malignant tumor, developing multimorbidity of from CMD to cancer was associated with a 9% higher probability of death compared to the reverse order, and this probability of transitioning to death was also significantly higher than in cases with only a single severe disease (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Dataset 1). Conversely, developing malignant tumors before severe CMD exhibited a similar probability of death to those with only a single severe disease.

a Transition probabilities in benign or in situ tumor subgroup (n = 366,001 individuals); b Transition probabilities in malignant tumor subgroup (n = 421,828 individuals); c Transition probabilities in mild CMD subgroup (n = 410,414 individuals); d Transition probabilities in severe CMD subgroup (n = 383,706 individuals); e Transition probabilities in both severe CMD and malignant tumor subgroup (n = 377,154 individuals). Data are presented as estimated transition probabilities and 95% confidence intervals in forest plots. The 10-year transition probabilities were calculated using a multistate model adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, employment status, education level, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, diet quality score, sleep duration, BMI, family history of T2D, CVD, and cancer, medication use for CMD and cancer, and participation in cancer screening.

Multiomics signatures and biological mechanisms

Genomics dataset (N = 375,239), metabolomics dataset (N = 234,452), and proteomics dataset (N = 44,816) were constructed among participants with corresponding omics data. The associations of omics-based markers with the 9 transitions in both the discovery and replication datasets are summarized in Supplementary Datasets 2 and 3, with significant markers presented in Supplementary Dataset 4. Polygenic risk score (PRS) for CMD (PRS-CMD) was positively associated with the development of CMD morbidity, CMD and cancer multimorbidity, and mortality, and PRS for cancer (PRS-cancer) was positively associated with baseline cancer and cancer-death (Fig. 4a). The top 4 positively and negatively associated metabolites and proteins for 9 transitions are annotated. Among the significant metabolites, phospholipids, triglycerides, and their related metabolites exhibited strong positive associations across 9 transitions. Glucose and glycoprotein acetyls were strongly associated with morbidity-related and multimorbidity-related death. Conversely, cholesteryl esters and related metabolites showed the strongest negative associations with most transitions. Across all the proteins, PRAP1 was strongly linked to CMD morbidity and progression from CMD to cancer, while KLK3 exhibited a strong positive association with cancer morbidity and the development of cancer-CMD multimorbidity. Notably, GDF15 had the strongest positive associations with most transitions. In contrast, ITGA11 and MXRA8 had strong negative associations with baseline-CMD, CMD and cancer multimorbidity, and mortality.

a Volcano plots of omics-based markers with the 9 transitions in the discovery and replication datasets (n = 375,239 for genomics dataset, n = 234,452 for metabolomics dataset, and n = 44,816 for proteomics dataset). The associations were estimated based on multistate models adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, employment status, education level, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, diet quality score, sleep duration, BMI, family history of T2D, CVD, and cancer, medication use for CMD and cancer, and participation in cancer screening. The volcano plots were drawn using the regression coefficients from the discovery dataset. False discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p values were applied for multiple comparisons in the discovery dataset, and raw p values were applied in the replication dataset. The top 4 positively and negatively associated metabolites and proteins for 9 transitions are labeled with the abbreviations, and their full names are provided in Supplementary Information. b The number of shared and distinct metabolomics and proteomics markers for the 9 transitions. c The top 5 biological pathways enriched in KEGG based on significant metabolomics and proteomics markers for the 9 transitions, respectively. One-sided hypergeometric tests (or Fisher’s exact tests) were used, and raw p values were reported to indicate potential biological functions. CA cancer, CMD cardiometabolic disease, PRS polygenic risk score.

Distinct and shared metabolites and proteins for transitions at different stages were identified, with a higher proportion of shared markers identified in the metabolomics dataset and more distinct markers for different transitions found in the proteomics dataset (Fig. 4b). Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed no significant outliers or distinct clustering across the 5 disease states (Fig. S4). Amino acids, including branched-chain amino acids, alanine, aspartate, and others, are primarily involved in the development of CMD or cancer morbidity (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Dataset 5). Amino acids and carbohydrates are crucial in the progression of CMD to multimorbidity and death, while the biosynthesis of neomycin, kanamycin, and gentamicin is associated with the development of cancer to multimorbidity and mortality outcomes. Significant inflammatory processes enriched by proteins were identified across the 9 transitions, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, lysosome, Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation, and key signaling pathways such as PI3K-Akt, NF-kappa B, and IL-17. Moreover, these inflammatory biological pathways were particularly activated during transitions from cancer to CMD or death, as well as from CMD-cancer multimorbidity to death (Fig. S5a). Similar inflammatory alterations were identified based on significant proteomics signatures through the Gene Ontology database (Fig. S5b and Supplementary Table 3).

Model development and performance

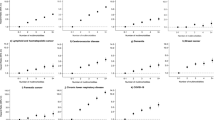

Omics-based scores were developed according to the procedures shown in Fig. 5a. Significant omics-based markers for each transition were used to develop prediction models using LASSO in the discovery dataset, with the coefficients presented in Supplementary Dataset 6. After LASSO regression, key predictors across 9 trajectory outcomes were identified (Fig. 5b). Among all metabolites and proteins, phospholipids to total lipids in very small VLDL percentage, glucose, linoleic acid to total fatty acids percentage, GDF15, WFDC2, and AREG were key predictors most frequently included in morbidity, multimorbidity, and mortality models. These frequently observed markers presented dose-response characteristics from health to morbidity and multimorbidity (Fig. S5c). In the replication dataset, genomics score (Gen-Score) and metabolomics score (Met-Score) showed modest to moderate predictive performance, and proteomics score (Prot-Score) performed the best for all 9 outcomes (Fig. 5c–e and Supplementary Table 4). Across the 9 outcomes, Prot-Score achieved Δ C-statistic (95% confidence intervals [CI]) of 0.14 (0.12, 0.16) for only CMD, 0.04 (0.03, 0.05) for only cancer, 0.03 (0.02–0.05) for only CMD-cancer, 0.04 (0.01–0.07) for only cancer-CMD, 0.08 (0.06–0.11) for direct death, 0.10 (0.07–0.13) for CMD-death, 0.05 (0.03–0.07) for cancer-death, 0.10 (0.06–0.15) for CMD-cancer-death, and 0.05 (0.02–0.09) for cancer-CMD-death.

a Overview of the model development procedures. Created in BioRender. Jiang, X. (2025) https://BioRender.com/u3bef2j. b Frequent genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics predictors identified through LASSO regression across 9 outcomes (n = 375,239 for genomics dataset, n = 234,452 for metabolomics dataset, and n = 44,816 for proteomics dataset). Predictors with non-zero coefficients were considered as selected features across the 9 outcomes. The Δ C-statistics between the base model and omics-based scores for c single morbidity outcomes, d multimorbidity outcomes, and e mortality outcomes (n = 375,239 for genomics dataset, n = 234,452 for metabolomics dataset, and n = 44,816 for proteomics dataset). ΔC-statistics and 95% confidence intervals are shown. The ΔC-statistics were estimated using time-dependent Cox models with 100 bootstrap resamples in the replication dataset. CA cancer, CMD cardiometabolic disease.

In the combined dataset, 22,789 participants remained with complete data for genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics. Prot-Score performed comparable to the combined score (Combined-Score), much better than the base model, lifestyle model, clinical model, and other omics-based scores at 10 and 15 years (Figs. 6 and S6). The corresponding area under receiver-operating characteristic curves (AUCs [95% CI]) of Prot-Score for only CMD, only cancer, only CMD-cancer, only cancer-CMD, direct death, CMD-death, cancer-death, CMD-cancer-death, and cancer-CMD-death at 10 years were 0.79 (0.78–0.81), 0.66 (0.64–0.67), 0.82 (0.80–0.85), 0.78 (0.75–0.81), 0.82 (0.80–0.85), 0.90 (0.88–0.93), 0.76 (0.73–0.78), 0.88 (0.84–0.92), and 0.80 (0.76–0.85), respectively, with a median improvement in AUCs of 0.09 compared with the base model (p ≤ 0.001). Similar improvements were also observed at 15 years.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for a single morbidity outcomes, b multimorbidity outcomes, and c mortality outcomes at 10 years (n = 22,789 individuals). Area Under the Curve (AUC) values were compared across the base model, lifestyle model, clinical model, genomics score, metabolomics score, proteomics score, and the combined omics score. Pairwise AUC comparisons were performed using non-parametric, 2-sided bootstrap resampling, and raw p values were reported. CA cancer, CMD cardiometabolic disease.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis, baseline characteristics were found to be comparable across the 3 omics datasets and the overall study population (Supplementary Table 5). Similar transition probabilities were observed after excluding skin cancer from cancer diagnosis, both overall and across the 3 individual omics datasets (Figs. S7–8 and Supplementary Table 6).

To further confirm and explore transition patterns, the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS) was utilized as an external cohort for validation. A total of 8418 participants in HRS were eligible for analysis (Fig. S9). Among the 8418 individuals in HRS, 2343 developed single CMD, 606 developed single cancer, and 298 experienced CMD and cancer multimorbidity during a follow-up of 12 years. Compared to the UK Biobank, participants in HRS had a baseline age of approximately 10 years older, a higher proportion of unemployment, and relatively lower educational attainment (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 7). Similar transition patterns were observed in HRS. Specifically, participants first diagnosed with cancer had a 10% higher probability of death at 8 years and a 12% higher probability of developing multimorbidity compared to those first diagnosed with CMD (Fig. S10 and Supplementary Table 8). Among individuals with CMD and cancer multimorbidity, developing CMD before cancer was associated with an 18% higher mortality probability. Different from the UK Biobank, a much higher proportion of participants in HRS developed CMD first, and those with multimorbidity had a lower probability of death compared to individuals with a single cancer.

Prot-Score showed robust predictive performance after skin cancer cases were excluded from cancer diagnosis (Fig. S11a and Supplementary Table 9). Further analysis revealed that among participants with pre-baseline CMD and cancer, Prot-Score significantly outperformed the base model for 8 outcomes, except for cancer alone (Fig. S11b and Supplementary Table 9). This predictive performance remained consistent between northern and southern UK populations (Supplementary Table 9). Prot-Score maintained consistently high predictive performance when the elastic net model was used (Supplementary Table 9). Prot-Score consistently outperformed the score consisting of a comprehensive biochemical profile across the majority of disease trajectories (Fig. S12).

Discussion

In the multimorbidity cluster of CMD and cancer, participants with multimorbidity had a 28–33% higher mortality risk and a loss of 5.0–5.3 survival years than those who remained healthy, and an 11–23% higher mortality risk and a loss of 2.4–3.6 survival years than those with only single morbidity. Initial development of cancer showed a higher probability of death and developing multimorbidity compared with an initial diagnosis of CMD. The probability of developing subsequent multimorbidity was primarily observed within 5 years after the onset of the first morbidity. Development of CMD-cancer presented a poorer prognosis than the reverse order, especially in severe cancer and CMD cases. Distinct and shared multiomics signatures captured features of disease sequences and prognosis. For most disease trajectories, Prot-Score achieved good predictive performance, with AUCs up to 0.90 at 10 years, and was better than traditional lifestyle and clinical models.

Studies have increasingly focused on multimorbidity development in the context of population aging, but most defined static clustering of diseases from a cross-sectional perspective and ignored the dynamic disease transitions and trajectories2,11,12. By tracing the temporal trajectories within the multimorbidity cluster of CMD and cancer, this study determines the occurrence, transitions, and prognosis of multimorbidity in this cluster. In this study, participants initially diagnosed with cancer had a particularly higher mortality risk at 5-year follow-up and a higher multimorbidity risk at 15-year follow-up than those with CMD as the first diagnosis. Similarly, a US study also reported a high mortality rate in cancer patients, with long-term cancer survivors more likely to die of noncancer-related causes, primarily due to heart disease13. The higher probability of multimorbidity in individuals with an initial cancer diagnosis may be attributed to multiple factors, including shared risk factors and biological pathways between CMD and cancer, as well as the significant role of cardiotoxicity associated with anti-cancer therapies5,14. Studies have indicated that prolonged chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer can lead to oxidative stress and cellular damage, resulting in cardiomyocyte injury, impaired left ventricular function, and subsequent development of overt heart failure, arrhythmias, and myocardial ischemia14. In addition to these functional cardiotoxic effects, several studies have also reported disruptions in lipid metabolism induced by anti-cancer therapies, specifically elevated triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) levels, which may further increase the risk of atherosclerotic CVD15. These results highlight the importance of specialized care for cancer survivors at different stages, focusing on short-term cancer management and long-term cardiovascular health. Interestingly, participants who first developed cancer followed by CMD had a slightly better prognosis, gaining 0.3 years of survival time, than those with CMD followed by cancer. This might be a result of enhanced monitoring and management among participants with cancer as the first diagnosis, such as through routine clinics, leading to better overall wellbeing16. Additionally, the CMD-cancer multimorbidity sequence may pose an added burden on pre-existing CMD conditions due to the cardiotoxic effects of cancer treatments14. Although such a small improvement in survival time might not be significant at the individual level, it provides evidence at the population level to guide CMD patients to enhance health monitoring and cancer screening. However, the potential benefits of implementing such preventive health services depend on the types of healthcare systems and the efficiency of the implementing institutions in the real world.

Among all CMD and cancer subtypes, stroke and low-survival-rate cancers had a 21–72% probability of direct death, much higher than other subtypes, which is consistent with the findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study and Cancer Statistics4,17. A US study found that participants with atherosclerotic CVD had a 20% higher risk of cancer than those without CVD and an 11% higher risk of cancer compared to those with nonatherosclerotic CVD18. However, this study observed similar probabilities of developing cancer between participants with atherosclerotic CVD (coronary artery disease and stroke) and those with nonatherosclerotic CVD (heart failure). Whether the discrepancy is driven by different study populations, various genetic backgrounds, or heterogeneities among subtypes of atherosclerotic or nonatherosclerotic CVD requires further investigation. During the follow-up, 11–25% of participants with incident cancer transitioned to incident CMD, with the highest proportion observed in those with liver and pancreatic cancer. Consistent with a study in China, participants with pancreatic cancer and liver cancer presented the highest risk of CVD19. Notably, the higher mortality probability in the CMD-cancer multimorbidity sequence was observed in cases of severe CMD, malignant tumors, or low-survival-rate cancers. Specifically, among individuals with both severe CMD and malignant tumors, developing CMD before cancer was associated with an approximately 10% higher probability of death compared to the reverse sequence. This may be attributed to intensive and prolonged treatments required for more severe cancers, which likely induce greater cardiotoxic effects14, resulting in a higher probability of transition from multimorbidity to mortality, especially in those with severe CMD. The above results indicated the risks of multimorbidity and mortality for patients with different subtypes of CMD and cancer, providing individualized guidance in clinical settings.

Previous studies have repeatedly reported the associations of genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics states with individual disease outcomes8,9,10. Beyond individual disease occurrence, this study first revealed that multiomics profiles provided comprehensive insights into disease trajectories of CMD and cancer, including disease transitions, multimorbidity development, and prognosis. For genomics, our findings indicated that PRS-CMD and PRS-cancer were significantly associated with the progression of CMD and cancer morbidity or multimorbidity, but the associations indicated by hazard ratios (HRs) were very modest. These results suggested that CMD or cancer progression and its subsequent events may largely be determined by environmental factors in later life9. Glucose and lipid metabolism are key factors in determining the occurrence and prognosis of CMD and cancer20,21. In our study, among all metabolites, triglyceride and phospholipid metabolism emerged as key markers across nine transitions, while glucose and glycoprotein acetyls were specifically associated with transitions to multimorbidity and mortality during the development of CMD and cancer. Notably, GDF15 may serve as a compelling target in the CMD and cancer trajectories given its robust associations with seven of the nine transitions in this study. As mentioned previously, GDF15 serves as a critical biomarker of cellular stress response and mitochondrial dysfunction, with strong relationships with various obesity-related metabolic disorders22. Our findings further suggested that the GDF15 expression level was a strong predictor of higher multimorbidity risk and worse clinical outcomes following a dose-response pattern. Furthermore, based on the key proteins and metabolites identified above, no significant clustering effects were observed across the five disease states. Previous studies have emphasized that metabolomics and proteomics capture molecular features associated with various biological processes8,10. However, the substantial individual heterogeneity within disease states may complicate the interpretation of metabolite and protein effects, particularly given that the first two PCs explained only a small proportion of the overall variance. The findings revealed that while several key proteins and metabolites were identified for specific disease transitions, significant individual variability existed.

The top protein-enriched pathways, such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, PI3K-Akt signaling, and lysosome-related pathways, were mainly associated with inflammatory and immune processes and were present across nearly all transitions23,24. Moreover, more altered inflammation- and immune-related signaling was observed in transitions from cancer to CMD, cancer to death, and CMD-cancer to death. Beyond the high baseline inflammation levels, many cancer therapies, such as radiation and immune therapies, can induce acute inflammatory changes25,26, potentially contributing to the high multimorbidity risk and poor outcomes in individuals initially diagnosed with cancer or those developing cancer after CMD. The identification of these shared and distinct biological pathways provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms associated with different disease states, supporting our understanding of disease progression and highlighting potential opportunities for early intervention.

Among three omics-based scores, Gen-Score showed a modest predictive performance for different disease trajectories. Although PRSs have been widely applied in research, these genomics scores cannot capture environmental exposures and physical conditions of individuals and may be limited in predicting complex age-related diseases or multimorbidity9. Met-Score showed moderate to good performance in predicting CMD development and progression, but showed only modest performance for cancer-related outcomes. This may be attributed to a relatively narrow metabolite coverage of current metabolomic techniques, with many disease signals undetected. Additionally, cancer-related metabolic alterations could be localized to distal or more refined tissues, making it more challenging to detect early through blood-based metabolomics. Prot-Score achieved the best performance among omics profiles, comparable to the combination of demographic, lifestyle, clinical, and multiomics markers, in predicting disease trajectories of CMD and cancer up to ~15 years in advance. The AUCs of Prot-Score ranged from 0.76 to 0.90 at 10 years and 0.77 to 0.91 at 15 years across 8 disease trajectory outcomes. The performance of Prot-Score for predicting cancer alone was relatively modest, although it remained statistically significant. This observation may be attributable to the fact that detectable proteomics markers are more likely to exist in specific tissues among individuals with cancer alone, compared to those with high multimorbidity and mortality risk. In contrast, robust performance of Prot-Score was observed in predicting both cancer-CMD multimorbidity and cancer-related mortality in people with cancer. These findings suggest that more detectable proteomics markers in the blood can be observed in cancer patients with poor prognosis than in cancer-only individuals, thereby enhancing the identification of high-risk cancer patients who would benefit most from early intervention and intensive monitoring. Importantly, without leveraging any laboratory or clinical information, our study strongly emphasizes the predictive value of Prot-Score as a single-source, individualized health assessment tool for predicting disease trajectories.

The robust performance of Prot-Score highlights the potential utility of incorporating a targeted set of proteins into routine clinical assessments for informing risk management of multimorbidity development and progression, particularly in older adults. This approach closely aligns with the use of routine biochemical profiles in clinical practice for monitoring general health and detecting potential disease risks27. However, unlike conventional biochemical tests that focus primarily on general physiological parameters, proteomics offers a deeper layer of biological insights. Protein-level data reflect upstream processes, such as gene expression regulation, activation of signaling pathways, and metabolic dysregulation, underlying the development of CMD and cancer multimorbidity cluster. This molecular-level resolution provides precise targets for disease prediction, personalized treatment, and early intervention strategies. Furthermore, even when compared to a comprehensive panel of 22 standard blood biochemical markers, Prot-Score presented superior predictive power and accuracy in forecasting disease transitions. These findings underscore the added value of proteomics in potentially enhancing conventional risk stratification approaches.

This study has several limitations. First, this study only focused on the 2 most common and related chronic diseases—CMD and cancer. More comprehensive multimorbidity patterns may be investigated in future studies with larger sample sizes. Second, dynamic changes in metabolomics and proteomics states during follow-up were not measured. However, baseline omics data provides an early snapshot to identify potential biomarkers and initial disease mechanisms, setting the stage for future studies that incorporate longitudinal data. Third, CMD and cancer diagnoses were obtained from hospital inpatient records and national cancer registries. Misdiagnosis or missed diagnoses may exist and introduce outcome misclassification. Fourth, the UK Biobank is a volunteer cohort. Participants may be generally healthier than the total population, which may introduce selection biases28. Fifth, information on participants’ medication use or other treatment during follow-up cannot be obtained in UK Biobank, which may influence the risk of subsequent events. Sixth, we used HRS as an external cohort to replicate the transition patterns, but the geographic location, survey approaches, and baseline characteristics vary significantly between HRS and the UK Biobank. Additionally, the 2-year survey intervals in HRS may result in loss of follow-up or incomplete outcome recording. However, these differences also confirm the population-level generalizability. Finally, the comprehensive analysis of disease trajectories poses substantial challenges in finding suitable external cohorts with multiomics data and long follow-up for validation of our identified multiomics signatures and omics-based risk scores. Although the discovery and replication datasets were rigorously designed internally, with participants selected from different geographical regions, and omics-based risk scores were thoroughly validated through multiple sensitivity analyses, further studies with well-characterized cohorts are still needed to establish the generalizability of the study findings.

In conclusion, this study found that the prognosis varied with different morbidities and multimorbidity with different temporal orders, as well as different subtypes in the multimorbidity cluster of CMD and cancer. Shared and distinct multiomics signatures were identified in the developmental trajectories of CMD and cancer. Prot-Score, independent of complex laboratory tests or clinical measures, showed good predictive capability of disease trajectories. This study identified a potentially useful proteomics-based approach for predicting disease trajectories within specific multimorbidity clusters. The findings may guide further validation studies in independent populations to assess its effectiveness and applicability in risk management of CMD and cancer multimorbidity, with the ultimate goal of informing future healthcare strategies in a rapidly aging world.

Methods

Study design and participants

The UK Biobank is a large population-based prospective cohort study consisting of approximately 0.5 million UK residents. UKB received approval from the National Information Governance Board for Health and Social Care and the National Health Service North West Centre for Research Ethics Committee (Ref11:/NW/0382). All participants provided written informed consent. This research was conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under application number 101169, utilizing data provided by patients and collected by the National Health Service as part of their care and support. Participants aged 37–73 years were enrolled from 2006 to 2010 from 22 assessment centers located in England, Wales, and Scotland29. Following the standardized process of interviews and questionnaires, extensive information on sociodemographics, health behaviors, and medical conditions was collected. All participants provided written informed consent. Information on participant compensation followed UK Biobank’s standard procedures, and participants received feedback on their health measurements. Participants without baseline CMD and cancer were included in this study.

Multiomics data collection and processing

Genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics data used in this study were collected at a single time point during baseline assessment (2006–2010). No repeated or longitudinal omics measurements were included in the analysis.

Genomics

Genome-wide genotype data have been collected from all participants at baseline (2006–2010). DNA was extracted from whole blood samples and genotyped using Applied Biosystems™ UK BiLEVE Axiom™ Array by Affymetrix (10% participants) and Applied Biosystems™ UK Biobank Axiom Array (90% participants)30. Phasing and imputation were performed based on the merged UK10K and 1000 Genomes Phase 3 reference panels and the HRC reference panel. Comprehensive quality control was conducted, including both marker-level and sample-level assessments30. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms for CMD and cancer were obtained from publicly available summary statistics from published genome-wide association studies (GWAS)31,32,33,34,35. PRS-CMD and PRS-cancer were calculated by the sum of an individual’s risk alleles, weighted by risk allele effect sizes derived from GWAS data. Details on the selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms are shown in Supplementary Dataset 7.

Metabolomics

Metabolomics data were generated by a high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics platform using baseline plasma samples (2006–2010) from a randomly selected subset of approximately 280,000 UK Biobank participants36. Metabolic measures from each plasma sample, including both absolute values and ratios, were quantified. A quality control protocol was conducted, addressing technical and biological repeatability, quality control flags, technical variation, and outlier plates37,38. Metabolomic variables with over 80% missing values across samples were removed. The remaining missing values were imputed using the K-nearest neighbors algorithm39.

Proteomics

Proteomics data were measured using the antibody-based Olink Explore 3072 proximity extension assay technology based on plasma samples collected randomly during the initial visit (2006–2010) from UK Biobank participants. Proteins were measured across 8 protein panels (cardiometabolic, cardiometabolic II, inflammation, inflammation II, neurology, neurology II, oncology, and oncology II). Quality control was performed to confirm no observed batch effects, plate effects, or abnormalities in protein coefficients of variation40. Proteomics data with more than 80% missing values across samples were excluded. The remaining missing values were imputed using the K-nearest neighbors algorithm39.

All omics data were standardized to ensure a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The 3 omics datasets included 2 PRSs, 251 metabolomics markers, and 2920 proteomics markers, respectively.

Outcomes and follow-up

Incident CMD, incident cancer, death, and diagnosis time were obtained from hospital inpatient records, national cancer registries, and national death registries during follow-up. Death and death time were sourced from the NHS Information Centre (England and Wales) and the NHS Central Register (Scotland) until 30 October 2023. CMD diagnoses were defined by the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) and included T2D (E11), coronary artery disease (I20-I25), stroke (I60-I64), and heart failure (I50), as detailed in Supplementary Table 1041,42. All-cause cancer was obtained through linkage to national cancer registries. The top low- and high-survival-rate cancer subtypes were defined by using the following ICD-10 codes recorded on the cancer registry: skin cancer (C44), breast cancer (C50), prostate cancer (C61), liver cancer (K760 and C22), lung cancer (C33-C34), esophageal cancer (C15), and pancreatic cancer (C25). Cancers were categorized into benign or in situ tumors and malignant tumors according to the behavior of cancer tumors (UK Biobank Field 40012). According to the top 4 risk factors for death among CMD individuals (high systolic blood pressure, high LDL, high body mass index [BMI], and high plasma glucose). High systolic blood pressure was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg; high LDL as LDL ≥ 2.6 mmol/L; high BMI as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; and high glucose as blood glucose ≥7 mmol/L. CMD was further grouped into mild (<3 risk factors) and severe (≥3 risk factors) subgroups. Participants were considered at risk from enrollment to death, loss to follow-up, or 30 October 2023, whichever came first.

Covariates

The covariates included demographic (age, sex, and ethnicity), socioeconomic characteristics (Townsend deprivation index [TDI], employment status, and education level), lifestyle factors (smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, diet quality score, sleep duration, and BMI), family history (family history of T2D, CVD, and cancer), medication use for CMD and cancer, and participation in cancer screening. Sex was defined based on self-report information. Ethnicity was self-reported and categorized as White and others. Education level was categorized as a higher degree (college degree, university degree, or professional qualifications), any school degree (advanced levels, advanced subsidiary levels, ordinary levels, General Certificate of Secondary Education, Certificate of Secondary Education, or equivalent), vocational qualification (National Vocational Qualification, Higher National Diploma, Higher National Certificate, or equivalent), and none of the preceding groups. Smoking and drinking status were categorized as never, ever, and current. Physical activity was defined by total metabolic equivalent task minutes per week for all activity. Diet quality score was calculated based on seven commonly eaten food groups according to the American Heart Association guidelines43. Medication use for CMD was defined as medication for cholesterol, blood pressure, or diabetes (UK Biobank Field 6177). Cancer-related medications were derived from treatment or medication records (UK Biobank Field 20003), primarily including immunomodulatory and cytotoxic therapies. Participation in cancer screening was defined as undergoing screening for breast, bowel, or prostate cancer.

Statistical analysis

Transition patterns

Baseline characteristics were described using means and standard deviations or counts and percentages. The proportion of missing covariate data was shown in Supplementary Table 11 and missing data were imputed using multiple imputations through chained equations with the R package “mice”. A total of five imputed datasets were created, and the results were pooled following Rubin’s rules.

Multistate models were used to analyze the transition probabilities in the temporal disease progression from health (i.e., free of CMD and cancer) to a single CMD or cancer, multimorbidity with both CMD and cancer, and death. The multistate model was conducted using Markov proportional hazards, an extension of competing risks survival analysis44,45. Competing risks deal with one initial state and several mutually exclusive absorbing states. This study applied a 4-state model with all individuals starting in a disease-free state (Fig. 1). From this state, individuals could transition to single CMD or cancer morbidity, multimorbidity, or death. The model facilitates the simultaneous estimation of each trajectory by analyzing all potential forward transitions between different health states.

Nine transitions in the multimorbidity cluster were constructed in this study (Fig. 1): Transition I, baseline-CMD; Transition II, baseline-cancer; Transition III, baseline-death; Transition IV, CMD-cancer; Transition V, CMD-death; Transition VI, cancer-CMD; Transition VII, cancer-death; Transition VIII, CMD-cancer-death; Transition IX, cancer-CMD-death. Participants diagnosed with CMD and cancer on the same date were excluded from the analysis because the temporal order of disease occurrences could not be ascertained. For participants who were diagnosed with CMD or cancer and died on the same date, we assigned the death date as the previous disease state plus 0.5 day.

Transition probabilities for the 9 transitions were estimated at 5, 10, and 15 years. Transition probabilities from baseline to CMD, cancer, or death were assessed in all participants, while transition probabilities from single morbidities to multimorbidity or death were evaluated in those with a diagnosed morbidity. Transition probabilities from multimorbidity to death were assessed in participants with both CMD and cancer. For participants at baseline or with a single morbidity, subsequent events were treated as mutually competing states (e.g., first diagnosis of CMD, first diagnosis of cancer, and direct death). Since the probability of transitioning from multimorbidity to death was the final state in our multi-state framework, no further competing events were defined beyond this point. Covariates, including age, sex, ethnicity, TDI, employment status, education level, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, diet quality score, sleep duration, BMI, family history of T2D, CVD, and cancer, medication use for CMD and cancer, and participation in cancer screening, were adjusted when estimating transition probabilities for participants at different stages. T-tests were used to compare the probabilities between transitions.

Subgroup analysis

Proportions of subsequent events for major subtypes of CMD (type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart failure) and cancer (skin, breast, prostate, liver, lung, esophageal, and pancreatic cancers) were calculated. Subgroup analyses were further conducted across various categories, including participants with benign or in situ tumors, malignant tumors, mild CMD, severe CMD, malignant tumors combined with severe CMD, low-survival-rate cancers, and high-survival-rate cancers. Transition probabilities were then estimated within each subgroup at a 10-year follow-up with the same adjustment above.

Survival analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to construct survival curves for the health state, single CMD morbidity, single cancer morbidity, CMD-cancer multimorbidity, and cancer-CMD multimorbidity. As the proportional hazards assumption was violated, restricted mean survival time (RMST) with an upper limit of 15 years was estimated for the 5 states using the R package “survRM2” to compare their prognostic outcomes. To enhance the comparability of covariates across the five states, propensity score matching was performed to account for covariates with substantial differences among the five states in the sensitivity analysis. The adjusted covariates included age, sex, ethnicity, education level, employment status, smoking status, drinking status, and BMI. RMST was calculated in the dataset after matching to further evaluate the robustness of the results.

Multiomics signatures

Participants born in England were used as the discovery dataset, while those born in non-England regions were held out as the replication dataset. To identify significant multiomics signatures associated with the nine transitions, multistate models were used to assess the associations of omics-based markers with nine transitions in the discovery and replication datasets. The same full set of covariates was adjusted. HRs and CIs were estimated for the nine transitions. In each omics dataset, significant omics-based markers were identified with FDR-adjusted p < 0.05 in the discovery dataset to account for multiple tests, a nominal p < 0.05 in the replication dataset, and consistent direction of associations. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is a comprehensive database for the systematic analysis of gene functions, metabolic pathways, cellular processes, and molecular interactions, offering valuable biological insights for both metabolomics and proteomics markers46. Pathway analysis was conducted using significant metabolomics and proteomics markers based on the human KEGG database. To further validate the pathways enriched by significant proteomics markers, an additional pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the Gene Ontology database. The top five significantly enriched pathways (p < 0.05) from KEGG and Gene Ontology were presented. Subsequently, inflammation-related pathways meeting the criteria of p < 0.05 and gene ratio >0.05 in KEGG were further identified for each transition, and their key contributing proteins were systematically summarized.

PCA was further applied to assess the variation and clustering structure of participants based on the top five and bottom five metabolites and proteins identified by HRs ranking in the discovery set. All variables were mean-centered and scaled to unit variance. Participants were grouped to assess whether metabolomics and proteomics profiles exhibited distinct separation or clustering patterns across five disease states (i.e., healthy, single CMD, single cancer, CMD-cancer, and cancer-CMD). The first 2 principal components (PC1 and PC2) were extracted for visualization and interpretation.

Model development and comparison

Significant omics-based markers were retained for model development for each transition outcome. Nine outcomes in the multimorbidity cluster were predicted, including (1) single morbidity outcomes: only CMD and only cancer; (2) multimorbidity outcomes: CMD-cancer and cancer-CMD; and (3) mortality outcomes: direct death, CMD-death, cancer-death, CMD-cancer-death, and cancer-CMD-death. We employed a 4-step machine learning framework consisting of: (1) feature selection, (2) hyperparameter tuning, (3) omics-based score calculation, and (4) performance evaluation. First, in the discovery dataset, feature selection was performed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox models for each outcome, incorporating age, sex, and significant omics-based markers in the 3 omics datasets separately. This approach enabled the data-driven identification of the most predictive markers, as our machine learning framework applies coefficient shrinkage to highly correlated markers. Second, the hyperparameter lambda values were determined using ten-fold cross-validation within the discovery dataset, implemented via the “caret” package in R. Model coefficients were then derived with the optimal lambda value identified through this process. Third, Gen-Score, Met-Score, and Prot-Score were calculated for each outcome as the weighted sum of the selected variables, using the coefficients obtained from the LASSO procedure. Fourth, in the replication set, Harrell’s C-statistic was estimated for the base model (age and sex) and three omics-based scores in three omics datasets, respectively; improvements in prediction were evaluated by comparing the two models using ΔC-statistic. The 95% CI for ΔC-statistic was calculated based on the bootstrap samples (n = 200).

To compare the predictive performance of different models, we further evaluated the performance of the base model, lifestyle model, clinical model, 3 individual omics-based scores (Gen-Score, Met-Score, and Prot-Score), and the Combined-Score in participants with all multiomics data. The base model included age and sex. The lifestyle model consisted of age, sex, 4 lifestyle behaviors (smoking status, physical activity, diet quality score, and sleep duration) based on Life’s Essential 847, and participation in cancer screening. The clinical model was adapted from Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation 2 (SCORE2) prediction models and included age, sex, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, non-HDL, and glucose48. The Combined-Score integrated base model, lifestyle model, clinical model, Gen-Score, Met-Score, and Prot-Score. Cox proportional-hazard models were fitted using the base model, lifestyle model, clinical model, Gen-Score, Met-Score, Prot-Score, and Combined-Score in the combined dataset. To assess the predictive performance of the Cox models, time-dependent AUCs at 10 and 15 years were calculated using the predicted probabilities of each outcome and the corresponding true event status for each individual. The distribution of bootstrapped differences in the time-dependent AUCs was used to statistically infer differences between the models.

Sensitivity analysis

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to confirm the stability and generalizability of the transition patterns. First, skin cancer was excluded from the cancer diagnosis since it is typically less severe and has a high survival rate17. Second, transition patterns were further examined in the three individual omics datasets to confirm the comparability and representativeness across datasets. Third, an external validation was conducted based on the HRS cohort. Specifically, HRS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of more than 37,000 individuals over age 50 in the USA. The detailed study design of HRS has been described elsewhere49. Questionnaire interviews were conducted every wave (2 years apart on average), while physical examination was conducted every 2 waves (4 years apart on average). To ensure a comparable baseline period between HRS and the UK Biobank, waves 9 to 15 of HRS (2008–2020) were used for replication in the sensitivity analysis. All participants provided written informed consent. The HRS was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and the National Institute on Aging. Participants without self-reported CMD and cancer before baseline were included in the HRS. CMD was defined as diabetes, heart disease, heart attack, heart failure, and stroke. In each interview wave, participants were asked whether they had been diagnosed with CMD or cancer by a doctor. If so, the earliest wave year of diagnosis was recorded as the time of diagnosis. Similar covariates, including age, sex, education level, employment status, income, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, and BMI, were considered. Education level was categorized as less than primary school, primary school, high school, and college or higher. Income was classified into low, intermediate, and high levels. Smoking and drinking status was categorized into current and never or ever. Physical activity was categorized into hardly ever or never, once a week or less, and more than once a week. Other variables with substantial missing data or not collected in HRS were not adjusted for. Transition probabilities were estimated at an 8-year follow-up.

Prot-Score was further validated in five aspects: (1) evaluate the performance after excluding skin cancer from cancer diagnosis; (2) assess its performance in participants with pre-existing CMD and cancer diagnoses before baseline, who were excluded from the primary analysis; (3) estimate its performance across different geographical regions, specifically among individuals from the northern and southern areas of the UK, with the classification criteria detailed in Supplementary Table 12; (4) use the elastic net model to construct prediction models and assess its performance; and (5) compare its 10-year predictive performance, measured by AUCs, with that of a comprehensive biochemical profile consisting of 22 standard biochemistry markers. The biochemical profile included albumin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, apolipoprotein A, apolipoprotein B, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, urea, cholesterol, creatinine, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, gamma glutamyltransferase, glucose, HbA1c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, insulin-like growth factor 1, LDL, lipoprotein A, total bilirubin, triglycerides, and urate.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.0. Major R packages used in the analysis included caret (v7.0.1) and glmnet (v4.1-10) for model training and regularized regression; mstate (v0.3.3) for multi-state modeling; dplyr (v1.1.4) for data manipulation; mice (v3.18.0) for multiple imputation; and survival (v3.8-3) for survival analysis.

Statistics and reproducibility

This research was conducted as an observational cohort study using data obtained from the UK Biobank. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Sample inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Fig. S1 and the “Study design and participants” section. Participants with pre-existing cardiometabolic diseases or cancer at baseline were excluded from the analysis. The study design did not involve any intervention, and therefore, traditional experimental procedures such as randomization and blinding are not applicable. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment, as this was an observational study analyzing pre-existing data.

Ethical approval

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. UKB received approval from the National Information Governance Board for Health and Social Care and the National Health Service North West Centre for Research Ethics Committee (Ref11:/NW/0382). The HRS was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and the National Institute on Aging.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The UK Biobank data used in this study are available under restricted access for approved research purposes. Access can be obtained by submitting a research application through the UK Biobank Access Management System at www.ukbiobank.ac.uk. All genomics, plasma metabolomics, and plasma proteomics are publicly available at the UK Biobank and could be accessed with a reasonable request. This research was conducted under UK Biobank Application Number 101169. The raw UK Biobank participant-level data are protected and are not available due to data privacy laws and the terms of our data access agreement. The Health and Retirement Study data used for external validation in this study are available in the HRS database under public use datasets at https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/ following completion of a data use agreement. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The R code used for all analyses in this study is publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/jiangxuanwei/Disease-Trajectory-Code50. Additional figures were created using the BioRender platform. Figures created with BioRender are in compliance with BioRender’s Academic License Terms and are intended for publication purposes.

References

Skou, S. T. et al. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 8, 48 (2022).

Barnett, K. et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 380, 37–43 (2012).

Farmer, C., Fenu, E., O’Flynn, N. & Guthrie, B. Clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 354, i4843 (2016).

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800 (2015).

Koene, R. J., Prizment, A. E., Blaes, A. & Konety, S. H. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation 133, 1104–1114 (2016).

de Boer, R. A., Meijers, W. C., van der Meer, P. & van Veldhuisen, D. J. Cancer and heart disease: associations and relations. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21, 1515–1525 (2019).

Guo, J. et al. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 1–40 (2022).

Buergel, T. et al. Metabolomic profiles predict individual multidisease outcomes. Nat. Med. 28, 2309–2320 (2022).

Lewis, C. M. & Vassos, E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 12, 44 (2020).

Carrasco-Zanini, J. et al. Proteomic signatures improve risk prediction for common and rare diseases. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03142-z (2024).

Jani, B. D. et al. Relationship between multimorbidity, demographic factors and mortality: findings from the UK Biobank cohort. BMC Med. 17, 74 (2019).

Raina, P. et al. The combined effect of cancer and cardiometabolic conditions on the mortality burden in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 74, 366–372 (2019).

Zaorsky, N. G. et al. Causes of death among cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 28, 400–407 (2017).

Lenneman, C. G. & Sawyer, D. B. Cardio-oncology: an update on cardiotoxicity of cancer-related treatment. Circ. Res. 118, 1008–1020 (2016).

Vergès, B., Walter, T. & Cariou, B. Endocrine side effects of anti-cancer drugs: effects of anti-cancer targeted therapies on lipid and glucose metabolism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 170, R43–R55 (2014).

Amin, M. B. et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more ‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 93–99 (2017).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 7–30 (2020).

Bell, C. F. et al. Risk of cancer after diagnosis of cardiovascular disease. JACC CardioOncol 5, 431–440 (2023).

He, D. et al. Increased incidence risks of cardiovascular disease among cancer patients: evidence from a population-based cohort study in China. Int. J. Cardiol. 396, 131362 (2024).

Zhang, Q., Xiao, S., Jiao, X. & Shen, Y. The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: evidence from NHANES 2001-2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 279 (2023).

Snaebjornsson, M. T., Janaki-Raman, S. & Schulze, A. Greasing the wheels of the cancer machine: the role of lipid metabolism in cancer. Cell Metab. 31, 62–76 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. GDF15: emerging biology and therapeutic applications for obesity and cardiometabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 592–607 (2021).

Fruman, D. A. et al. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell 170, 605–635 (2017).

Rabin, R., Reeves, H. C., Wegener, W. S., Megraw, R. E. & Ajl, S. J. Glyoxylate in fatty-acid metabolism. Science, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3703.1548 (1965).

Stewart, J. R., Fajardo, L. F., Gillette, S. M. & Constine, L. S. Radiation injury to the heart. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 31, 1205–1211 (1995).

Riley, R. S., June, C. H., Langer, R. & Mitchell, M. J. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 175–196 (2019).

Cebul, R. D. & Beck, J. R. Biochemical profiles. Applications in ambulatory screening and preadmission testing of adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 106, 403–413 (1987).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1026–1034 (2017).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Sato, G. et al. Pan-cancer and cross-population genome-wide association studies dissect shared genetic backgrounds underlying carcinogenesis. Nat. Commun. 14, 3671 (2023).

Malik, R. et al. Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat. Genet. 50, 524–537 (2018).

Vujkovic, M. et al. Discovery of 318 new risk loci for type 2 diabetes and related vascular outcomes among 1.4 million participants in a multi-ancestry meta-analysis. Nat. Genet. 52, 680–691 (2020).

Shah, S. et al. Genome-wide association and Mendelian randomisation analysis provide insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure. Nat. Commun. 11, 163 (2020).

Nelson, C. P. et al. Association analyses based on false discovery rate implicate new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 49, 1385–1391 (2017).

Würtz, P. et al. Quantitative serum nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics in large-scale epidemiology: a primer on -omic technologies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1084–1096 (2017).

Julkunen, H. et al. Atlas of plasma NMR biomarkers for health and disease in 118,461 individuals from the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 14, 604 (2023).

Ritchie, S. C. et al. Quality control and removal of technical variation of NMR metabolic biomarker data in ~120,000 UK Biobank participants. Sci. Data 10, 64 (2023).

Lee, J. Y. & Styczynski, M. P. NS-kNN: a modified k-nearest neighbors approach for imputing metabolomics data. Metabolomics 14, 153 (2018).

Sun, B. B. et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 329–338 (2023).

Eastwood, S. V. et al. Algorithms for the capture and adjudication of prevalent and incident diabetes in UK Biobank. PLoS ONE 11, e0162388 (2016).

Bosco, E., Hsueh, L., McConeghy, K. W., Gravenstein, S. & Saade, E. Major adverse cardiovascular event definitions used in observational analysis of administrative databases: a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 21, 241 (2021).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction. Circulation 121, 586–613 (2010).

de Wreede, L. C., Fiocco, M. & Putter, H. The mstate package for estimation and prediction in non- and semi-parametric multi-state and competing risks models. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 99, 261–274 (2010).

Putter, H., Fiocco, M. & Geskus, R. B. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat. Med. 26, 2389–2430 (2007).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s Essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 146, e18–e43 (2022).

SCORE2 working group and ESC Cardiovascular risk collaboration SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 42, 2439–2454 (2021).

Sonnega, A. et al. Cohort Profile: the health and retirement study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 576–585 (2014).

Jiang, X. Jiangxuanwei/disease-trajectory-code: multiomics insight into disease trajectories of cardiometabolic diseases and cancer (multi-state). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16750278 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thanked the UKB participants for their dedication to participating in ongoing research and EHR linkage. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 101169, utilizing data provided by patients and collected by the National Health Service as part of their care and support. This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2506700, awarded to V.W.Z.); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373551, awarded to V.W.Z.); Public Welfare Technology Research Funding Project of Zhejiang (LTGY24H020004, awarded to C.Z.); Medical School Joint Innovation and Open Fund of Lishui University (No. X111001, awarded to C.Z.); and the Innovative Research Team of High-Level Local Universities in Shanghai (awarded to V.W.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J., G.Y., X.D., C.Z., and V.W.Z. designed the study. X.J., G.Y., and M.C. performed data analysis and figure generation. X.J., G.Y., and V.W.Z. drafted the manuscript. X.J., G.Y., M.C., N.F., L.X., X.D., C.Z., and V.W.Z. contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Heinz Freisling, Jonathan K. L. Mak, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Yang, G., Chen, M. et al. Multiomics insight into disease trajectories of cardiometabolic diseases and cancer. Nat Commun 17, 813 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67510-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67510-0