Abstract

Cholera, a severe diarrhoeal illness caused by Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae), poses a significant threat to public health worldwide. The emergence of multidrug-resistant V. cholerae strains underscores the urgent need for preventive and therapeutic interventions. In this study, we elucidate the role of outer membrane protein V (OmpV) in the virulence of V. cholerae and propose a therapeutic strategy targeting OmpV. Subcellular localization analysis shows that OmpV is present in both the bacterial outer membrane (OM) and bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs). When V. cholerae enters the small intestine, OmpV is activated by the CarSR two-component system in response to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) in the small intestine, leading to increased bacterial pathogenicity. The upregulation of ompV not only augments bacterial adhesion but also promotes the internalization of BEVs into host cells, thereby increasing the delivery of cholera toxin (CT) to host cells. Computational aided drug design (CADD) shows that the small-molecule inhibitor C607-0736 is capable of disrupting the virulence functions of OmpV. Animal experiments show that C607-0736 efficiently inhibits the colonization and pathogenicity of the V. cholerae O1 and O139 strains. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of OmpV-targeting strategies and offer promising avenues for addressing multidrug-resistant V. cholerae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

V. cholerae, the bacterium responsible for the deadly disease cholera, has been a significant public health concern for centuries. Since 1817, seven cholera pandemics have plagued humans worldwide. The ability of V. cholerae to cause large-scale outbreaks and pandemics has made it a major focus of research and public health efforts1,2. Among the various serogroups of V. cholerae, O1 and O139 are primarily responsible for pandemic outbreaks. O1 has been linked to six of the seven recorded cholera pandemics, whereas O139 emerged in 1992 and caused a spread in parts of Asia owing to its unique ability to circumvent immunity in populations previously exposed to O11,3. Oral rehydration solution (ORS) and antibiotics are typically used to treat cholera4,5. However, the global issue of bacterial antibiotic resistance, particularly the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) V. cholerae, is increasingly concerning6. As a result, the identification of targets and therapies for the prevention and control of cholera is urgently needed.

V. cholerae typically infects hosts after the oral ingestion of contaminated food or water. Once ingested, V. cholerae survives the acidic gastric environment, penetrates the mucus layer and adheres to the epithelium of the small intestine7. At the infection site, V. cholerae produces an array of virulence factors, including cholera toxin (CT) and toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP). CT encoded by ctxAB on the filamentous CTXΦ is responsible for acute secretory diarrhea7,8. The expression of these virulence factors is tightly controlled by a hierarchical regulatory cascade involving ToxR-ToxS, TcpP-TcpH and cytosolic ToxT9,10. During infection, CT can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). This triggers the activation of central innate immune pathways, which in turn activate the secretion of several proinflammatory cytokines11,12.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs), such as α-defensins, β-defensins, and cathelicidin LL-37, are small cationic molecules that exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity through both direct pathogen neutralization and immunomodulatory functions13. Notably, Paneth cells localized at the base of small intestinal crypts secrete α-defensins (termed cryptdins in mice) in response to bacterial stimuli to combat invasive enteric infections14. Nonetheless, certain pathogens, such as Shigella spp. and V. cholerae, have evolved mechanisms to sense CAMPs and enhance their virulence in vivo15. During infection, V. cholerae colonizes in the intestinal crypts and develops CAMPs resistance via the CarSR two-component system by upregulating the almEFG operon16. Furthermore, HD-5, one of the most abundant α-defensins secreted by Paneth cells, promotes V. cholerae colonization through the CarSR two-component system-mediated virulence pathway by upregulating tcpP expression17.

Adhesion to the host cell is the first step in bacterial infection. During this process, pathogens express a variety of adhesion factors to facilitate host-pathogen interactions. Understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms governing these interactions is essential for the development of new “antiadhesive” therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing pathogen colonization. Recently, a group of outer membrane protein (OMP) adhesins was identified as playing key roles in bacterial adherence to specific host molecules. For example, OmpA and Omp33 produced by Acinetobacter baumannii are involved in binding to human lung epithelial cells18,19. OmpV, produced by Salmonella Typhimurium facilitates bacterial adherence to intestinal epithelial cells via fibronectin20. In V. cholerae, OmpU has been reported to function as an adhesin, although its role in adhesion remains controversial21,22. Despite these findings, the roles of OMPs in V. cholerae adhesion remain largely unknown.

In addition, bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) have diverse pathophysiological functions, including facilitating adherence to host cells, delivering virulence factors, and modulating immune responses23,24. BEVs are nanoscale vesicles that are released by bacteria through a contact-free transport and communication mechanism and serve as carriers of virulence factors23. BEVs shed from the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria are spherical membranous structures primarily composed of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), phospholipids, OMPs, and a lumen filled with cargos that consist mainly of periplasmic proteins25. The interaction between bacteria and host cells triggers the release of BEVs. Once secreted, OMPs on BEVs enhance the ability of BEVs to bind to host cells26,27. Following adherence, BEVs can be internalized into host cells, allowing the transfer of virulence factors and other components into the host cell. This BEV-mediated delivery of virulence factors is recognized as a potent mechanism utilized by many bacterial pathogens. Virulence factors such as the ClyA cytotoxin, haemolysin F, and CNF1 of Escherichia coli, as well as vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) from Helicobacter pylori, are secreted through BEVs28,29,30. Similarly, BEV-mediated secretion of the CT and Vibrio cholerae cytolysin (VCC) has also been reported in V. cholerae31,32.

In this study, we revealed the role of OmpV in V. cholerae pathogenicity and developed a drug targeting OmpV as a potential treatment for cholera infection. We found that OmpV enhances the intestinal colonization and cytotoxicity of V. cholerae. The expression of ompV is activated by the two-component system (TCS) CarSR, with phosphorylated CarR binding directly to the ompV promoter in response to HD-517. OmpV, located in the OM, facilitates bacterial adhesion to the intestinal epithelium, whereas OmpV in BEVs contributes to the internalization of BEVs by host cells. This process enhances the delivery of CT into host cells, leading to the induction of proinflammatory cytokine production. On the basis of the structural and functional characteristics of OmpV, we used computational-aided drug design (CADD) to identify an antibacterial drug33, C607-0736, which effectively inhibits OmpV-mediated bacterial adherence and delivers cholera toxins. Furthermore, we showed that C607-0736 can significantly inhibit the colonization of V. cholerae O1/O139 and OmpV-containing V. parahaemolyticus strains harboring ompV in animal experiments. These results suggest that C607-0736 has potential for the treatment of infections caused by pandemic V. cholerae.

Results

CAMPs promote ompV expression via TCS CarSR

Previous research showed that TCS CarSR can sense various CAMPs and regulate gene expression17. Transcriptomic analysis elucidated that the expression of ompV was significantly upregulated in response to CAMPs17. Genomic analysis elucidated that ompV and carSR are located close to each other in the genome (Fig. 1a); thus, we hypothesized that ompV is regulated by TCS CarSR in response to CAMPs. To test this hypothesis, qRT-PCR assays were performed. The results revealed that the expression of ompV was significantly decreased (5.20-fold) in the ΔcarR strain compared with the wild-type (WT) V. cholerae strain EL2382 (O1) strain (Fig. 1b), indicating that CarR positively regulates the expression of ompV.

a Schematic diagram of the structure of the carR, carS and ompV region. b The expression level of ompV in the WT, ΔcarR and ΔcarR+ strains in AKI medium (n = 3 independent experiments). c, d The expression level of ompV in WT (c) and ΔcarR (d) strains in AKI medium supplemented with 0 or 50 μg/mL HD-5 (n = 3 independent experiments). e–g EMSA of the specific binding of purified CarR to the promoter regions of ompV (e), rrsA (negative control) (f), and ompV without the -28 and −45 elements (PompV-1) (g) with 30 mM (Acp) to activate CarR. h Fold enrichment of rpoS and PompV in CarR-ChIP samples, as measured by qPCR (n = 3 independent experiments). rpoS was used as a negative control. Significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (b–d, h) and is indicated by the p value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns no significant difference. The data were the mean ± s.d. (b–d, h). Results are representative of three biological replicate experiments (e–g). The source data were included in the Source Data file.

Next, we investigated the mechanism by which HD-5 induces ompV expression through TCS CarSR. The qRT-PCR results revealed that ompV expression was significantly upregulated (4.83-fold) in the WT strain after treatment with HD-5 compared with that in the untreated control (Fig. 1c). In contrast, ompV expression in the ΔcarR strain was not significantly different in AKI medium with or without HD-5 (Fig. 1d). These results indicate that HD-5 induces ompV expression via CarSR.

To further elucidate the regulatory mechanism through which ompV expression is regulated by the phosphorylation of CarR, sequence analysis of the promoter region of ompV was performed. A potential CarR box (5’-TACAGTGTTCACATCCA-3’) was detected from -45 to −28 bp in the ompV promoter region, indicating that CarR may directly regulate ompV expression by binding to the promoter region of ompV. To prove this hypothesis, the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) revealed that when CarR was phosphorylated by acetyl phosphate (Acp), the migrating bands were observed for the ompV promoter (PompV) (Fig. 1e) but not for rrsA (negative control) (Fig. 1f), indicating that phosphorylated CarR specifically binds to the PompV region in vitro. Furthermore, EMSAs revealed that CarR cannot bind to PompV-1 (the potential CarR box deleted in PompV) (Fig. 1g), suggesting that the potential CarR box in PompV is vital for the interaction between CarR and PompV. Then, ChIP-qPCR further revealed 17.05-fold greater enrichment of PompV in the CarR-ChIP samples than in the mock-ChIP samples (Fig. 1h), whereas there was no significant difference in the enrichment of rpoS between the CarR-ChIP and mock-ChIP samples (Fig. 1h). Collectively, these results indicate that phosphorylated CarR by CAMPs positively regulates ompV expression by directly binding to PompV.

OmpV contributes to the pathogenicity in response to CAMPs

CAMPs have the potential to promote the pathogenicity of V. cholerae17. To confirm whether CAMPs are present in the infant mouse intestine during infection, the expression of the murine Cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (mCRAMP), encoded by the Cnlp gene in mice34, was examined during V. cholerae infection. The immunostaining was performed to detect the expression and location of mCRAMP in the small intestines of V. cholerae-infected and uninfected mice. The results confirmed that mCRAMP expression was markedly increased in infected mice and distributed throughout the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 2a). Quantitative fluorescence analysis and qRT-PCR results showed that mCRAMP levels were significantly upregulated in V. cholerae-infected mice (Fig. 2b–d). Importantly, mCRAMP co-localized with the TcpA of V. cholerae during infection, with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.71 ± 0.08 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). These data indicate that mCRAMP is induced globally in the small intestine while spatially associated with adherent V. cholerae.

a Immunostaining assay of mCRAMP in the small intestine of uninfected and WT-infected infant mice. mCRAMP was stained with an anti-CRAMP antibody (red), V. cholerae was stained with an anti-TcpA antibody (green), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The images showed the co-localization of TcpA and mCRAMP in the small intestine after V. cholerae infection (n = 15). Scale bar, 50 μm. b, c Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) analysis of mCRAMP (b) and intestinal cells (c) in each field (n = 15). Three visual fields from each mouse were analyzed, and five mice were examined. Box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles. Whiskers represent the minimum and maximum data points. Horizontal bars indicate the median. d The expression of Cnlp in the small intestine of uninfected and WT-infected infant mice (n = 3 mice per group). e The expression level of ompV in the small intestine of mice and LB medium (n = 3 mice per group). f Evaluation of the colonization ability of the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains in the small intestine of mice (n = 6 mice per group). Significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (b–e) or two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test (f) and is indicated by the p value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns no significant difference. The data were presented as the mean ± s.d. (b–f). The source data are included in the Source Data file.

Based on these results, we hypothesize that OmpV may enhance the pathogenicity of V. cholerae in vivo in response to CAMPs during infection. To test this hypothesis, we first compared ompV expression in WT in the infant mouse intestine and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth medium via qRT-PCR. The results revealed that the expression of ompV in the small intestine of mice was significantly increased by 5.57-fold compared with that in LB medium (Fig. 2e). We subsequently constructed ompV mutant (ΔompV) and ompV complement strains (ΔompV+). A mouse colonization assay revealed that the colonization ability of the ΔompV strain was significantly lower than that of the WT strain (Fig. 2f), and it was restored to the WT level in ΔompV+ (Fig. 2f), indicating that OmpV promotes V. cholerae colonization in the small intestine. In addition, growth curve analysis revealed that there was no significant difference in the growth of the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains in LB medium (Supplementary Fig. 1b), indicating that the impact of OmpV on V. cholerae pathogenicity is not due to differences in bacterial growth. Collectively, these results indicate that OmpV enhances V. cholerae pathogenicity in vivo.

OmpV is located in the outer membrane and promotes bacterial adhesion

To elucidate the role of OmpV in pathogenesis, we examined its subcellular localization via PRED-TMBB and SWISS-MODEL35,36, which predicted that OmpV is located in the bacterial outer membrane (Fig. 3a). We expressed the OmpV-FLAG fusion protein in ΔompV. The western blot results showed that OmpV-FLAG could be detected in the cytosolic fraction, outer membrane and BEVs (Fig. 3b). These findings indicate that OmpV may contribute to bacterial pathogenesis through multiple pathways.

a 3D modeling of OmpV via SWISS-MODEL. OUT indicates the extracellular space. OM indicates the outer membrane. IN indicates intracellular components. b Western blot of OmpV-FLAG from the outer membrane (OM), BEVs, and cell lysate (CL). c Adherence of V. cholerae WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains to Caco-2 cells (n = 3 independent experiments). d qRT-PCR analysis of virulence gene expression in the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains in AKI medium (n = 3 independent experiments). e, f Western blot and quantitative analysis of cholera toxin in the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains in AKI medium (n = 3 independent experiments). RNA polymerase (RNAP) was used as a loading control. g, h Western blot and quantitative analysis of cholera toxin in Caco-2 cells infected with WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains (n = 3 independent experiments). β-actin was used as a loading control. Significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (c, d, f, h) and is indicated by the p value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns no significant difference. The data were presented as the mean ± s.d. (c, d, f, h). Results are representative of three biological replicate experiments (b). The source data are included in the Source Data file.

Given that OMPs play a key role in mediating bacterial attachment to host cells in many bacteria37,38. We hypothesized that OmpV promotes the pathogenicity of V. cholerae by increasing its ability to adhere to cells. The results revealed that the ability of the ΔompV strain to adhere to Caco-2 cells was significantly lower than that of the WT and ΔompV+ strains (Fig. 3c). These data indicate that OmpV promotes the ability of V. cholerae to adhere to cells in vitro. We further investigated whether OmpV influences the expression of key virulence genes (tcpP, toxT, toxR, and ctxA). The qRT-PCR results revealed that the expression of these virulence genes exhibited no significant difference among the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains in AKI medium (Fig. 3d). The western blot results also revealed that the protein levels of CT among the WT, ΔompV, and ΔompV+ strains were not significantly different (Fig. 3e, f). These results indicate that OmpV has no effect on the expression of CT in V. cholerae. We then asked whether OmpV influences the delivery of CT into host cells. Surprisingly, intracellular CT was significantly reduced in ΔompV-infected cells compared with WT or ΔompV+, indicating that OmpV facilitates CT delivery to host cells (Fig. 3g, h). Together, these findings suggest that OmpV may enhance the delivery of CT into host cells beyond promoting bacterial adhesion.

OmpV in BEVs promotes the delivery of CT to host cells

OMPs in BEVs can drive the uptake of the vesicles by intestinal epithelial cells, enabling BEVs to deliver CT into host cells, and promoting the pathogenic effects31,39. Our previous results showed that OmpV can also be located in BEVs (Fig. 3b). Therefore, we hypothesize that OmpV may act as an adhesion for BEVs, facilitating their internalization and delivery of CT into host cells.

To confirm this hypothesis, we first purified BEVs from culture supernatants of the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains, examined them via transmission electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Then, whether OmpV in BEVs promotes the internalization of BEVs into host cells was analysed via fluorescence measurements in combination with the fluorescent dye rhodamine R18. Purified rhodamine-R18-labeled BEVs from WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ culture supernatants were incubated with Caco-2 cells, the infected cells were labeled with DAPI, and the fluorescence intensity was quantified. The results revealed that at 30 min p.i., BEVs derived from the WT and ΔompV+ strains (but not from the ΔompV strain) were internalized by Caco-2 cells (Fig. 4a). Moreover, an increase in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was observed when WT- and ΔompV + -derived BEVs were used to treat Caco-2 cells (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the MFI in Caco-2 cells treated with ΔompV-derived BEVs did not obviously increase above the background level (Fig. 4b). These results demonstrate that OmpV in BEVs facilitates BEV internalization by epithelial cells.

a, b Membrane fusion mediated by BEVs derived from WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ was observed via confocal microscopy (a), and the fluorescence intensity of BEVs (b) was measured to reflect BEV uptake (n = 15 representative fields of view per group). BEVs were stained with rhodamine isothiocyanate B-R18 (orange), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. c, d Amounts of cholera toxin in equal amounts of BEVs derived from the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains (n = 3 independent experiments). Coomassie blue staining was used to quantify the amount of sample protein and as a loading control (c). e, f Cholera toxin in BEVs derived from the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains were observed via confocal microscopy (e), and the fluorescence intensity of cholera toxin (f) was measured to reflect the ability of BEVs to deliver cholera toxin (n = 15 representative fields of view per group). Cholera toxin was stained with an anti-cholera toxin antibody (green), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. g qRT-PCR analysis of TNFα and IL 1β induction by BEVs derived from the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains in Caco-2 cells (n = 3 independent experiments). h, i Representation (h) and histological score (i) of WT,- ΔompV-, and ΔompV + -derived BEVs in the infant mouse intestine 22 h p.i. (n = 3 independent experiments). Significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (b, d, f, g, i) and is indicated by the p value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns no significant difference. The data were presented as the mean ± s.d. (b, d, f, g, i). The source data were included in the Source Data file.

As OmpV promotes BEV internalization by host cells, we next investigated the impacts of OmpV on CT delivery into host cells. We first quantified the total proteins in BEVs derived from the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains through sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 4c) and then determined the CT level via western blot. Similar CT levels were detected in the BEVs derived from the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains (Fig. 4d), indicating that OmpV has no effect on the CT level in BEVs, which is consistent with the above finding that OmpV does not influence the production of CT. We subsequently analysed the level of CT delivered into host cells after incubation with BEVs derived from the WT, ΔompV and ΔompV+ strains by immunofluorescence. The results revealed that the CT level in Caco-2 cells infected with ΔompV-derived BEVs was lower than that in Caco-2 cells infected with WT- and ΔompV + -derived BEVs (Fig. 4e, f), suggesting that the promotion of BEV internalization by OmpV increases the delivery of CT into host cells. Meanwhile, the innate immune responses induced by CT were analysed via qRT-PCR. Compared with those infected with WT- and ΔompV + -derived BEVs, Caco-2 cells infected with ΔompV-derived BEVs presented significantly decreased TNFα and IL 1β expression (Fig. 4g), indicating that the CT delivery promoted by OmpV-mediated BEV internalization facilitates TNFα and IL 1β expression in intestinal epithelial cells. To assess the role of BEVs in vivo, mice were orally gavaged with WT, ΔompV, or ΔompV + -derived BEVs. The results showed that mice receiving ΔompV-derived BEVs exhibited significantly lower intestinal histopathology scores than those treated with WT or ΔompV + -derived BEVs (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Collectively, these results indicate that OmpV in BEVs promotes CT delivery to host cells and intestinal inflammation and disease severity.

To further determine whether BEVs are required for bacterial adherence and colonization, we conducted a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments. In vitro, BEVs were purified from the culture supernatants of WT, ΔompV, and ΔompV+ strains. Caco‑2 cells were pretreated with BEVs derived from each strain and subsequently infected with the corresponding bacteria. Adherence assays revealed that BEV pretreatment did not alter the adhesion of WT, ΔompV, or ΔompV+ (Supplementary Fig. 3c–e), indicating that OmpV on BEVs does not influence bacterial adherence. In vivo, mice were orally administered BEVs derived from WT, ΔompV, and ΔompV+ strains, followed by infection with the corresponding strains. BEVs treatment did not affect intestinal colonization (Supplementary Fig. 3f–h). These findings suggest that OmpV in BEVs does not influence bacterial adherence or colonization.

Small-molecule compound inhibits OmpV-mediated pathogenicity

The above results showed that OmpV is important for V. cholerae pathogenicity. Inhibiting the role of OmpV in virulence may represent a promising strategy for effectively combating V. cholerae infection. Therefore, CADD was used to identify potential compounds that could serve as inhibitors of OmpV function. The 3D structure of OmpV in V. cholerae EL2382 was generated via AlphaFold, and the potential binding regions were identified via the SiteMap module on the basis of the site score (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Among the binding regions, pocket 1 not only has the highest score but also has the largest pocket. Therefore, we chose pocket 1 for the virtual screening.

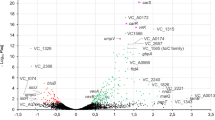

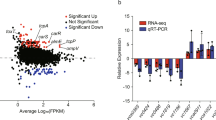

A compound library consisting of 1,620,000 compounds from the ChemDiv and TargetMol databases was utilized to identify OmpV inhibitors. After library preparation, the ligands were used for docking against the target protein OmpV via the glide module in a virtual screening flow. After the high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), standard precision (SP), and extra precision (XP) stages, we obtained 1256 compounds, as shown in Supplementary Data 1. These compounds were subsequently assessed according to the Lipinski rules and combined with absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) predictions to select the top 36 compounds with the most favorable scores in Supplementary Data 2. Among these 36 potential ligands, E521-1356, S823-2720, V020-3795, Y020-0697, and C607-0736 presented the maximum negative binding energies (−11.3782, −11.1603, −11.0093, −10.8831, and −10.8606, respectively). The ligand-receptor interactions were visualized via a ligand interaction diagram module and depicted in both 2D and 3D diagrams (Supplementary Fig. 4b–k). As V020-3795 was unavailable for purchase, four small-molecule compounds, namely, C607-0736 (TargetMol, USA), E521-1356 (TargetMol, USA), S823-2720 (TargetMol, USA) and Y020-0697 (TargetMol, USA), were acquired for further functional validation. Further surface plasmon resonance (SPR) kinetic analyses revealed that the Kd values of C607-0736, E521-1356, S823-2720, and Y020-0697 with OmpV were 0.1227 to 0.3247 μ M (Fig. 5a–d). The SPR results showed that these four small-molecule compounds with strong affinities predicted by virtual screening indeed bind to OmpV.

a–d Biacore SPR kinetic analyses of C607-0736 (a), E521-1356 (b), Y020-0697 (c), and S823-2720 (d) binding to OmpV. Sensorgram and saturation curve of the titration of different substrates on OmpV immobilized on a CM5 chip. e–h Adherence of V. cholerae WT and ΔompV incubated with or without the small-molecule inhibitors C607-0736 (e), E521-1356 (f), Y020-0697 (g), and S823-2720 (d) to Caco-2 cells (n = 3 independent experiments). i–l Membrane fusion mediated by BEVs derived from the WT and ΔompV strains incubated with or without small-molecule inhibitors was observed via confocal microscopy (i, k), and the fluorescence intensity of BEVs (j, l) was measured to reflect BEV uptake (n = 15 representative fields of view per group). BEVs were stained with rhodamine isothiocyanate B-R18 (orange), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. m, n CETSA assays and quantitative analysis determined the effect of C607-0736(m) and DMSO(n) on the thermal stability of OmpV-FLAG and RNAP (negative control) at whole-cell level (n = 3 independent experiments). Significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (e–h, j, l, m, n) and is indicated by the p value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns no significant difference. The data were presented as the mean ± s.d. (e–h, j, l, m, n). The source data are included in the Source Data file.

A bacterial adherence assay was subsequently performed to assess the impact of these small-molecule inhibitors on V. cholerae adhesion. The results demonstrated that at a concentration of 20 µM, E521-1356, C607-0736, and Y020-0697, but not S823-2720, significantly inhibited the adherence ability of the WT strain (Fig. 5e–h). Additionally, E521-1356 and Y020-0697 also reduced the adherence ability of the ΔompV strain (Fig. 5f, g), suggesting that their influence on bacterial adherence is independent of OmpV. Conversely, C607-0736 did not affect the adherence ability of the ΔompV strain (Fig. 5e), indicating that C607-0736 inhibits the adherence ability of the WT strain by targeting the function of OmpV. Immunofluorescence assays revealed a significant decrease in the internalization of WT-derived BEVs into Caco-2 cells in the presence of C607-0736 and E521-1356 (20 µM). However, S823-2720 and Y020-0697 did not influence the internalization of WT or ΔompV-derived BEVs (Fig. 5i, j). Only C607-0736 had no effect on the entry of ΔompV-derived BEVs into Caco-2 cells (Fig. 5k, l), indicating that C607-0736 can reduce the internalization of BEVs derived from V. cholerae by blocking the function of OmpV. The qRT-PCR results revealed that treatment with these compounds did not influence the expression of virulence genes in V. cholerae in AKI medium (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Furthermore, these small-molecule inhibitors (at a concentration of 20 µM) did not significantly influence the growth of the WT or ΔompV strains (Supplementary Fig. 5b–e).

In addition, the binding specificity of C607-0736 to OmpV were further confirmed at the whole-cell level using a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA). The results showed that at a concentration of 20 µM, C607-0736 significantly increased the thermal stability of OmpV-FLAG, ranging from 47 to 67 °C, compared to the DMSO control in bacteria (Fig. 5m, n). Furthermore, the thermal stability of RNAP (negative control) shared similar trends in response to DMSO and C607-0736 in ΔompV + (FLAG) (Fig. 5m, n). Collectively, these results support the conclusion that C607-0736 can directly bind to OmpV at the cell level. So, our subsequent analyses focused on elucidating the effects of C607-0736 on V. cholerae pathogenicity.

C607-0736 is a broad-spectrum inhibitor of infection caused by pandemic V. cholerae

The V. cholerae O1 and O139 serogroups are the main strains responsible for epidemic cholera8. Comparative genomics analysis has demonstrated that ompV is present in all available V. cholerae O1 and O139 genomes, highlighting its potential as a promising target for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.

To determine the appropriate in vivo dosage of C607-0736, we first evaluated its toxicity and potential side effects in C57BL/6 mice over a 2-week period following oral administration of 1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg C607-0736. The haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining results showed that all four tested concentrations did not cause any significant histological abnormalities in the hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, or kidneys of the mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Compared with the DMSO group, administration of all four tested concentrations of the C607-0736 did not significantly affect the body weight change rates, food intake levels, or liver weights of the mice, indicating that no toxicity and side effects of C607-0736 were observed (Supplementary Fig. 6b–d).

Then, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of oral C607-0736 at 1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg against V. cholerae using an infant mouse colonization assay. The results indicated that, compared to the DMSO control group, C607-0736 significantly inhibited V. cholerae colonization in the small intestine only at concentrations of 10 and 20 mg/kg (Supplementary Fig. 6e). This suggests that C607-0736 exhibits limited therapeutic efficacy at lower concentrations (1 and 5 mg/kg) but significant treatment effects at higher concentrations (10 and 20 mg/kg). Therefore, we selected 10 mg/kg as the minimum effective concentration of the C607-0736 for subsequent in vivo experiments.

To further verify the inhibitory effect of C607-0736 on the pathogenicity of V. cholerae O1 and O139 in vivo, three pandemic V. cholerae O1 strains (EL2382, EL2281, and EL1605) and O139 strains (strains MO45, 0820, and 0539) were selected, and corresponding ΔompV strains were constructed. Then, mouse colonization assays were performed with each strain. The results revealed that the colonization of the WT strain in the small intestine of mice administered 10 mg/kg of the C607-0736 was significantly lower than that in the small intestine of mice not receiving C607-0736, indicating that C607-0736 significantly inhibited the colonization ability of these V. cholerae strains in the small intestine (Fig. 6a, b). In addition, C607-0736 administration had no effect on colonization of ompV mutants in the small intestine of mice (Fig. 6c, d), indicating that C607-0736 widely inhibits the colonization ability of different pandemic V. cholerae strains by blocking the function of OmpV.

a, b Evaluation of the colonization ability of three pandemic V. cholerae O1 strains (EL2382, EL2281, and EL1605) (a) and three V. cholerae O139 strains (MO45, 0820, and 0539) (b) in the small intestine of mice administered 10 mg/kg of the C607-0736 (+) or placebo (−) after 22 h (n = 6 mice per group). c, d Evaluation of the colonization ability of three ΔompV pandemic V. cholerae O1 strains (ΔompV-(EL2382), ΔompV-(EL2281), and ΔompV-(EL1605)) (c) and three ΔompV V. cholerae O139 strains (ΔompV-(MO45), ΔompV-(0820), and ΔompV-(0539)) (d) in the small intestine of mice administered 10 mg/kg of the C607-0736(+) or placebo (−) after 22 h (n = 6 mice per group). e–g Evaluation of the colonization ability of ΔompV + (EL2382) and ΔompV + (EL2382-N28A) (e), ΔompV + (MO45) and ΔompV + (MO45-N28A) (f), and ΔompV + (G2871) and ΔompV + (G2871-N28A) (g) in the small intestine of mice administered 10 mg/kg of the C607-0736(+) or placebo (−) after 22 h (n = 6 mice per group). Significance was determined by a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test (a–g) and is presented as the p value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns no significant difference. The data were presented as the mean ± s.d. (a–g). The source data are included in the Source Data file.

In addition to V. cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus is a clinically important pathogen with substantial public health relevance40. Further comparative genomics analysis revealed that OmpV is also distributed in some V. parahaemolyticus strains (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Next, we investigated whether C607-0736 has an inhibitory effect on the OmpV-containing V. parahaemolyticus strain G2871. Compared to the control group, C607-0736-treated mice exhibited a significant reduction of G2871 bacterial load in the small intestine (Supplementary Fig. 7b) without affecting the growth of these bacteria (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

The 3D structures of the OmpV protein in the V. parahaemolyticus strain G2871 was subsequently generated via SWISS-MODEL. The interactions between C607-0736 and OmpV proteins in V. parahaemolyticus was visualized with the ligand interaction diagram module and represented as 2D and 3D diagrams (Supplementary Fig. 7d, e), which confirmed that C607-0736 can also specifically bind to the OmpV of V. parahaemolyticus strain G2871. Furthermore, combined analysis of the docking results indicated that Asn28 is conserved in OmpV from the V. cholerae O1/O139 and V. parahaemolyticus strains and may be essential for facilitating the binding of C607-0736 to OmpV proteins.

To test this hypothesis, the bN28A OmpV of V. cholerae O1 EL2382 strain was generated. The SPR assay showed that C607-0736 failed to interact with purified N28A OmpV, which is different from the results found for wild-type OmpV (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 8a). To further confirm the binding specificity of N28A OmpV to C607-0736 at the whole-cell level, we analyzed the binding specificity of C607-0736 to the ΔompV strain expressing the N28A OmpV-FLAG fusion protein (ΔompV + (N28A-FLAG)). The results showed that, both DMSO and C607-0736 had no effects on the thermal stability of N28A OmpV-FLAG in ΔompV + (N28A-FLAG) (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c).

Furthermore, we complemented the Vibrio cholerae O1 ΔompV strain with wild-type ompV and N28A-ompV derived from V. cholerae O1 EL2382 (generating strains ΔompV + (EL2382) and ΔompV + (EL2382-N28A)), V. cholerae O139 MO45 (generating strains ΔompV + (MO45) and ΔompV + (MO45-N28A)), and V. parahaemolyticus G2871 (generating strains ΔompV + (G2871) and ΔompV + (G2871-N28A)). The results of the mouse colonization assay demonstrated that C607-0736 effectively inhibited the colonization ability of the ΔompV + (EL2382), ΔompV + (MO45), and ΔompV + (G2871) strains. Conversely, the administration of C607-0736 did not impact the colonization of the ΔompV + (EL2382-N28A), ΔompV + (MO45-N28A), or ΔompV + (G2871-N28A) strain (Fig. 6e–g). These results suggest that the conserved Asn28 residue is critical for the interaction between C607-0736 and OmpV, through which C607-0736 impedes the colonization ability of pandemic V. cholerae strains and OmpV-containing V. parahaemolyticus strains. These findings provide a foundation for further development of C607-0736 as a potential therapeutic agent for treating Vibrio infections.

Discussion

Upon entering the gut, pathogens employ various strategies to adapt to the intestinal environment and increase their pathogenicity. In this study, we found that the two-component system CarSR of V. cholerae senses CAMPs and activates the expression of ompV by directly binding to its promoter region. This activation not only facilitates V. cholerae adherence to the intestinal epithelium but also promotes the entry of CT into epithelial cells through BEVs. These results highlight the complex strategies V. cholerae uses to adapt to the intestinal environment, thereby increasing its pathogenicity. Moreover, we showed that the small-molecule inhibitor C607-0736, which was identified through CADD, is an effective therapy for several Vibrio species infections. This study not only revealed the role of OmpV in the pathogenesis of Vibrio species but also introduced new therapeutic strategies involving the targeting of pathogen-host interactions.

In bacteria, OMPs have a diverse range of functions, including importing nutrients and translating signals from the outside environment. During infection, OMPs play pivotal roles in adhesion, colonization, regulation of pathogenic factor expression and resistance to antibiotics. For example, OipA of Helicobacter pylori is required for adhesion to host cells and the induction of inflammatory cytokine production38,41. OMPs (OmpA and CarO) in Acinetobacter baumannii are essential for establishing infection and interact with β-lactamase to regulate antibiotic inactivation42. OmpV is also present in several other pathogens in addition to Vibrio species, including Salmonella Typhimurium and Cronobacter20,43, suggesting that drugs targeting OmpV may be effective against a broad range of pathogens, thereby increasing the clinical relevance of such treatments. Additionally, the stable structure of OmpV makes it more difficult for pathogens to develop resistance through genetic mutations, providing a long-term effective therapeutic strategy and helping to combat the rise of resistant bacterial strains. Furthermore, the surface exposure of OmpV on both bacteria and bacterial extracellular vesicles not only enhances drug recognition but also simplifies drug delivery, thereby preventing issues such as inadequate permeability and/or export via efflux pumps44. Since OmpV plays important roles in bacterial infection and adhesion, targeting OmpV has the potential to disrupt pathogenic mechanisms effectively, resulting in potent antimicrobial effects.

The development of small-molecule drugs generally involves multiple stages, including screening, optimization, preclinical studies, and clinical trials. High-throughput screening techniques and CADD have significantly accelerated the discovery of small-molecule drugs33. Moreover, advancements in pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism studies have greatly improved the safety and efficacy of these drugs. Previous studies have demonstrated the widespread utilization of CADD for screening natural small molecules as potential antimicrobial agents42,45. In this study, we utilized CADD to target the interaction between drug molecules and OmpV, identifying several potential small-molecule inhibitors. Further validation confirmed that C607-0736 could specifically reduce both V. cholerae adhesion in vitro and colonization in vivo. Given the widespread distribution of OmpV among various pathogens, these small-molecule inhibitors may also have potential for combating other bacterial infections beyond V. cholerae. This approach not only highlights the effectiveness of CADD in the development of anti-infective agents but also underscores its potential in rapidly advancing infectious disease treatment. Future research will focus on optimizing these small molecules for clinical use.

Cholera remains a major health problem in developing countries2. Although oral rehydration therapy is regarded as the treatment of choice to control cholera, antibiotics are commonly used to treat this disease4. However, increasing antibiotic resistance in V. cholerae has diminished the effectiveness of these drugs6. Thus, approaches to prevent or treat V. cholerae infection are urgently needed. One promising approach is targeted molecular therapy using small-molecule drugs. Unlike traditional antibiotics, small-molecule drugs can interact with specific targets, such as enzymes, receptors, and proteins, thereby modulating the pathogenic process with minimal impact on the host. This enhances therapeutic effectiveness and reduces side effects. In recent years, small-molecule drugs have emerged as valuable tools for developing antibacterial agents on the basis of antiadhesion strategies. Examples include the antiadhesion salvianolic acid B against Neisseria meningitidis, the use of cranberry proanthocyanidins against uropathogenic E. coli, and the use of antiadhesive peptides derived from the enzymatic hydrolysis of pea seeds (Pisum sativum) against Helicobacter pylori FnBP46,47,48. Therefore, naturally occurring small molecules identified as potential therapeutic agents for treating cholera show potential for the development of innovative treatments.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables 1, 2. Briefly, V. cholerae O1 EL Tor strains EL2382, EL2281, and EL1605; V. cholerae O139 strains MO45, 0820, and 0539; and Vibrio parahaemolyticus strain G2871 were all preserved strains in our laboratory. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) was used for recombinant protein expression. The E. coli S17/λpir strain was used for conjugation. The bacterial strains were subsequently grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1% NaCl), LBS (3% NaCl) or AKI medium (1.5% Bacto peptone, 0.4% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, and 0.3% NaHCO3)49,50. Bacteria were grown at 37 °C or 16 °C with shaking at 180 rpm. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: polymyxin B, 30 μg/mL; ampicillin, 50 μg/mL; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/mL; and kanamycin, 50 μg/mL.

Mutant construction and complementation

All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The construction of the mutants was performed via the suicide vector pRE11251. For complementation, genes with native promoters were amplified via PCR, cloned and inserted into the pBAD33 vector. For ChIP-qPCR, carR was amplified along with its promoter region and cloned and inserted into pBAD33 in frame with a C-terminal 3×FLAG. For protein purification, carR or ompV was amplified, cloned and inserted into the pET28a vector. For the fusion protein, ompV was amplified via PCR and cloned and inserted into pTrc99A in frame with a C-terminal 3×FLAG.

Infant mouse colonization assay

An infant mouse intestinal colonization assay was used to evaluate the pathogenic capacity of each V. cholerae strain or the therapeutic efficacy of C607-073652. Five-day-old CD-1 mice of both sexes were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China), placed in incubators at 30 °C with a relative humidity of 50 ± 5%, and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12 h light/dark cycle.

To assess the colonization capacity of different bacterial strains and the therapeutic efficacy of the small-molecule inhibitor, ~105 CFU of V. cholerae cells were intragastrically administered to groups of six anaesthetized mice. When necessary, different doses of the C607-0736 (1 to 20 mg/kg) or 10 μg BEVs was administered by gavage immediately after or with bacterial challenge53,54. Twenty-two hours after infection, the mice were euthanized, and the small intestine of each mouse was removed, weighed, homogenized, and plated on LB agar plates containing polymyxin B (30 μg/mL).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

To detect ompV or Cnlp expression in vivo, samples were harvested from the small intestine of the mice. To analyse the expression of ompV in vitro, the samples were incubated in AKI medium with or without HD-5 (50 μg/mL) until they reached the stationary phase. To analyse the expression of virulence genes in vitro, samples were collected from cells grown in AKI medium under aerobic conditions with or without inhibitors. To analyse the expression of inflammatory factors, Caco-2 cells were cultured in DMEM with or without BEVs (5 μg/mL) for 4 h. Total RNA was isolated via TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Next, the total RNA concentration was determined via a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Three independent experiments were performed. cDNA was synthesized via StarScript III RT MasterMix (Genestar, A233) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR analysis was conducted with an Applied Biosystems ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green fluorescence dye (Genestar, A304). To normalize the sample data, the rrsA, rpoS and GAPDH genes were used as normalization controls, and relative expression levels were calculated as fold change values via the 2−ΔΔCT method. The experiments were independently performed three times.

Growth curve

To determine the growth curve of each strain in LB medium, overnight cultures were washed with PBS three times and diluted to 106/ml in LB broth. A 200 μL aliquot was added to a 96-well microplate and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with shaking. The absorbance was recorded at 600 nm via a BioTek LogPhase 600 (Agilent). When necessary, various concentrations of small-molecule inhibitors were added to the culture medium. The experiments were performed independently three times.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

The 6×His-tagged CarR protein was expressed and purified in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The target DNA fragments were amplified and purified with a SPARKeasy Gel DNA Extraction Kit (Sparkjade, AE0101). The purified DNA fragments (40 ng) were incubated at 25 °C for 30 min with the 6×His-tagged CarR protein at concentrations ranging from 0-3 µM in 20 μL of binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 30 mM acetyl phosphate). The protein–DNA fragments were electrophoretically separated on a native polyacrylamide gel at 4 °C and 90 V/cm. UV transillumination was used to visualize the DNA bands on the gel after 10 min of staining in 0.1% GelRed. The experiments were performed independently three times.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR

Exponentially growing bacterial cultures of the CarR-ChIP strain were induced with 0.2% L-arabinose (wt/vol) and 50 μg/mL HD-5 until the mid-log phase before being treated with 1% formaldehyde for 25 min at 25 °C. Crosslinking was stopped by the addition of 0.5 M glycine. The samples were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C and washed three times with cold PBS. Next, the samples were resuspended and sonicated to generate DNA fragments of 100–500 bp. The samples were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma, B3111) and protein A magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Waltham, United States; #10002D) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An aliquot with no added antibody served as the negative control (mock). The samples were incubated with 8 μL of 10 mg/mL RNaseA for 2 h at 37 °C and with 4 μL of 20 mg/mL proteinase K at 55 °C for 2 h. The DNA fragments were purified with a PCR purification kit (SparkJade, AE0101-C). To measure the enrichment of CarR-binding peaks, ChIP‒qPCR was performed on an ABI 7500 sequence detection system. The rpoS gene (nonspecific enrichment) was used as a normalization control, and relative expression levels were calculated as fold change values via the 2−ΔΔCT method. The experiments were performed independently three times.

Isolation and labeling of BEVs

Cultures of V. cholerae were grown at 37 °C and 180 rpm in LB before the cells were removed from the supernatant by centrifugation (9000×g, 15 min). The supernatant was filtered through 0.22-μm pore size filters to remove intact cells. The OD600 of each culture was determined via photometric measurements with a GENESYS 10 s spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for BEV quantification. To ensure that no bacteria remained in the supernatant, 1 ml of the filtrate was plated on LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C. The BEVs present in the supernatant were pelleted through subsequent ultracentrifugation (150,000×g, 4 °C, 4 h). The protein concentration was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Sangon Biotech, C503021) according to the manufacturer’s manual. The purified BEVs were stored at −80 °C. When necessary, the BEVs were fluorescently labeled with octadecyl rhodamine B chloride (R18) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, O246) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

For the OMVs, 20 μL droplets of vesicle suspensions were placed onto carbon-coated 200-mesh copper grids. The samples were then stained with a 1% (w/v) phosphotungstate acid solution for 5 min. The excess fluid was removed with a piece of filter paper. The grids were allowed to air dry and then imaged with a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400PLUS SOP, Japan).

Preparation of outer membrane proteins and whole-cell lysates

Proteins from the outer membrane were prepared essentially55. The V. cholerae strains were grown overnight and harvested by centrifugation (6500×g, 10 min, 4 °C), washed once in HEPES buffer and resuspended in 750 µl of HEPES buffer followed by cell disruption. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation (22,000×g, 30 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was then centrifuged again (138,000×g, 60 min, 4 °C). The membrane fraction was solubilized with 0.3% N-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (Solarbio; D8890). After centrifugation (22,000×g, 60 min, 4 °C) of the solubilized membrane fraction, the supernatant containing OmpV was subsequently purified using Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow with 0.03% DDM. The protein concentrations of the outer membrane preparations were determined with a BCA protein assay kit. For whole-cell lysates, V. cholerae cultures were harvested via centrifugation (3200×g, 10 min, 4 °C). The cell pellets were directly resuspended in SDS‒PAGE loading buffer, boiled for 10 min and subjected to SDS‒PAGE.

SDS‒PAGE and western blot

To detect cholera toxin expression in the strains, samples were harvested from AKI medium56. To evaluate the presence of cholera toxins in the vesicles, V. cholerae BEVs were separated. The BEVs were mixed with SDS‒PAGE loading buffer, boiled for 10 min and loaded onto SDS‒PAGE gels. Gels stained with Coomassie blue were processed in parallel with the same samples used for immunoblot analyses and served as a loading control. To observe the localization of OmpV in V. cholerae, the outer membrane, vesicles and whole-cell lysates were analysed via SDS‒PAGE. To observe the amount of CT delivered into Caco-2 cells by BEVs, the infected cells were harvested. The samples were separated via 10% SDS‒PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) by electroblotting. Blots for RNA polymerase (RNAP), FLAG-tag, and cholera toxin were incubated with β-actin and anti-RNA polymerase beta (Abways, CY7097), anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma, B3111), anti-beta subunit cholera toxin antibodies (Abcam, ab123129), and anti β-actin antibody (CW0096M and CWBIO). The blots were further incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG (Sparkjade, EF0001) and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Sparkjade, EF0002) tagged with horseradish peroxidase. Detection was carried out with a Sparkjade ECL Plus (ED0016; Sparkjade) detection system. Images were acquired with an Amersham Imager 600 system (General Electric).

Bacterial adherence assays

Caco-2 cells were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology of the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China), and were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2 until they reached confluence and then subcultured in a 6-well plate for 24 h. Before infection, the cells were washed with PBS three times, and fresh DMEM without antibiotics or fetal bovine serum was added. The cell monolayers were then infected with exponential-phase bacteria grown in DMEM at an MOI of 100 or 5 ug/mL BEVs. Two hours after incubation, unattached bacteria were removed by washing with PBS. The cells were then disrupted with 0.1% SDS, and lysate dilutions were plated on LB agar plates. The adhesion rate was calculated as previously described. To block adherence mediated by OmpV, 20 µM concentrations of small-molecule inhibitors were added to the culture medium. The experiments were performed independently three times.

Immunofluorescence

To monitor BEVs entry into Caco-2 cells, fluorescence staining assays were performed57. Briefly, the cell monolayers were incubated with R18-labeled BEVs (2 μg/well) at 37 °C for 30 min. The coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. The cell nuclei were labelled with DAPI. To block adherence mediated by OmpV, 20 µM concentrations of small-molecule inhibitors were added to the culture medium.

To evaluate the presence of CT obtained from vesicles in Caco-2 cells, the cell monolayers were incubated with BEVs (2 μg/well) at 37 °C for 30 min. The coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, permeabilized, and blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies (Abcam, ab123129) overnight at 4 °C, washed three times with PBS, incubated with secondary antibodies (Sparkjade, EF0007) for 1 h, and stained with DAPI for 5 min (Solarbio, C0065). Following staining, a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM800) was used for image acquisition, and ImageJ software (Fiji) was used to analyse the fluorescence intensity. Pearson correlation coefficients were generated using the Zen software.

Surface plasmon resonance

Analyses of ligand binding and binding kinetics were performed at 25 °C on a Biacore X100 (BR110073). All the experiments were carried out with HBSP as the running buffer, with a constant flow rate of 10 μL/min at 25 °C. OmpV or N28A OmpV, which was diluted with 10 mmol/L sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) to a final concentration of 10 μM, was immobilized on the surface of a CM5 sensor chip via an EDC/NHS crosslinking reaction according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The target immobilization level of OmpV or N28A OmpV was set at 3000 RU. Small-molecule inhibitors were diluted with running buffer to concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 25 μM and injected into the reference channel and OmpV or N28A OmpV channel at a flow rate of 10 μL/min. The coupling and dissociation times were both set to 120 s. Biacore X100 evaluation software was used to fit the affinity curves via the steady-state affinity model (1:1), and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was calculated.

Adult mouse colonization assay

An adult mouse intestinal colonization assay was used to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of C607-0736 against V. parahaemolyticus as previously described58. For the V. parahaemolyticus intestinal colonization experiment, eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were gavaged with streptomycin (20 mg) and orally infected with 109 CFU of bacteria 24 h later. When necessary, 10 mg/kg of the C607-0736 was administered by gavage immediately after bacterial challenge. Twenty-two hours after infection, the mice were euthanized, and the small intestine of each mouse was removed, weighed, homogenized, and plated on LBS agar plates.

Biological safety evaluation

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were treated with C607-0736 (1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) by gavage daily for 2 weeks. Mice treated with PBS as controls (six mice per group). The body weight change rates and food intake levels of the mice were monitored daily. The main organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys, were collected after the final treatment, weighed and subjected to haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to detect toxicity in vivo.

BEVs in intestinal injury

To assess the effect of BEVs on intestinal epithelial cell damage, 10 μg of BEVs was intragastrically administered to each mouse. Twenty-two hours post-administration, the mice were euthanized, and intestinal tissues were collected for H&E staining.

Histology and immunostaining

For hematoxylin and eosin staining, the small intestines of infected adult and infant mice were collected for analysis. The small intestine was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The histological score was calculated based on the following parameters: the intensity of mononuclear cell and polymorphonuclear cell (neutrophil) infiltration, mucosal architectural changes, villus height, goblet cell depletion, epithelial integrity, and adherent bacteria. For each parameter, the grading criteria were defined as follows: 0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe.

For immunostaining, after dewaxing, blocking in hydrogen peroxide/methanol solution, rehydration, and antigen retrieval, the slides were subjected to immunostaining. The mCRAMP and cholera toxin were incubated with CAMP rabbit antibody (ABclonal, A1640) and anti-TcpA monoclonal antibodies (Willget Biotech Co., Ltd.). DAPI staining for cell nuclei.

Computationally aided drug design

To predict the presence of a signal peptide in the target protein, we used SignalP 6.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0/) to analyse the protein sequences for potential signal peptides. The transmembrane protein model was analysed via PRED-TMBB and displayed via SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.ExPASy.org/).

The OmpV protein sequence was retrieved from the UniProt database (UniProt ID-P06111), and the three-dimensional structure was developed by using the AlphaFold protein database. The Protein Preparation Wizard module was used to hydrogenate the protein, add missing side chains, and then perform energy optimization (OPLS2005 force field). The Sitemap module was used to predict the binding site of the processed protein; the same binding pocket observed in the template protein substrate was selected as the center to generate a grid file, and the box size was set to 20 Å × 20 Å × 20 Å.

The Chemdiv (D001) and TargetMol (T001) databases were prepared using the LigPrep module of Schrodinger. The ligands were prepared by considering parameters such as optimization, determination of promoters, tautomers, stereochemistry, 2D to 3D conversion, ionization state at pH 7.0, ring confirmation, and correction of partial atomic charges via the OPLS4 force field.

After library preparation, the ligands were used for docking against the target protein OmpV via the glide module in a virtual screening flow. This process includes three sequential phases, i.e., high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), standard precision (SP), and extra precision (XP). The top 10% of the ligands from HTVS docking were selected for SP docking via Glide. Furthermore, the top 10% of the ligands with high docking scores according to the SP results were subjected to XP docking. Finally, the top compounds were selected based on the Lipinski rules and scoring, and the physical and chemical properties and ADMET predictions were evaluated via the Datawarrior tool and SwissADME server. MOE and PyMOL were used to create all the graphical representations of the 2D and 3D models.

Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

Overnight cultures were washed three times with PBS and then diluted to 109 cells/mL in LB broth. They were incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 2.5 h. Then the cells were resuspended in PBS containing 20 µM C607-0736 or an equivalent concentration of DMSO. After being incubated at 37°C for 30 min, they were incubated at 47, 52, 57, 62, and 67 °C for 3 min, respectively. The samples were subjected to four freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen. Then, they were centrifuged to collect the supernatant for analysis via SDS–PAGE59.

Statistical analyses

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes. Animals were randomly assigned to the control and manipulation groups for data collection. The researchers were unaware of the experimental conditions of the mice at the time of testing. Other data collection methods were not randomized, but test groups were always analysed in parallel with the controls. No animals or data points were excluded from the reported data.

The data were analysed via t-tests or Mann–Whitney U- tests, as indicated in the specific figure legends. Values with p < 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001 were considered statistically significant (*), highly significant (**), or extremely significant (***), respectively; n.s. indicates no significance. The data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. Figures were generated via GraphPad 7 and Adobe Illustrator 2024.

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were performed according to the standards set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal studies were conducted according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Nankai University (Tianjin, China) and performed under protocol no. IACUC 2016030502.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The relevant data are provided within the manuscript, Supplementary Information and Supplementary Data files. Uncropped scans of all western blots and EMSAs, including a molecular weight marker, are provided in the Source Data file.

References

Faruque, S. M. et al. Emergence and evolution of Vibrio cholerae O139. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1304–1309 (2003).

Hu, D. et al. Origins of the current seventh cholera pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E7730–E7739 (2016).

Ali, M. et al. The global burden of cholera. Bull. World Health Organ 90, 209–218 (2012).

Chowdhury, F., Ross, A. G., Islam, M. T., McMillan, N. A. J. & Qadri, F. Diagnosis, management, and future control of cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 35, e0021121 (2022).

Lindenbaum, J., Greenough, W. B. & Islam, M. R. Antibiotic therapy of cholera in children. Bull. World Health Organ. 37, 529–538 (1967).

Das, B., Verma, J., Kumar, P., Ghosh, A. & Ramamurthy, T. Antibiotic resistance in Vibrio cholerae: Understanding the ecology of resistance genes and mechanisms. Vaccine 38, A83–A92 (2020).

Almagro-Moreno, S., Pruss, K. & Taylor, R. K. Intestinal colonization dynamics of Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004787 (2015).

Harris, J. B., LaRocque, R. C., Qadri, F., Ryan, E. T. & Calderwood, S. B. Cholera. Lancet 379, 2466–2476 (2012).

Bina, T. F. et al. Bile salts promote ToxR regulon activation during growth under virulence-inducing conditions. Infect. Immun. 89, e00441–21 (2021).

Demey, L. M., Sinha, R. & DiRita, V. J. An essential host dietary fatty acid promotes TcpH inhibition of TcpP proteolysis promoting virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. mBio 15, e00721–e00724 (2024).

Kim, D. et al. Nod2-mediated recognition of the microbiota is critical for mucosal adjuvant activity of cholera toxin. Nat. Med. 22, 524–530 (2016).

Olvera-Gomez, I. et al. Cholera toxin activates nonconventional adjuvant pathways that induce protective CD8 T-cell responses after epicutaneous vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 2072–2077 (2012).

Talapko, J. et al. Antimicrobial peptides-mechanisms of action, antimicrobial effects and clinical applications. Antibiotics 11, 1417 (2022).

Salzman, N. H., Ghosh, D., Huttner, K. M., Paterson, Y. & Bevins, C. L. Protection against enteric salmonellosis in transgenic mice expressing a human intestinal defensin. Nature 422, 522–526 (2003).

Xu, D. et al. Human enteric α-Defensin 5 promotes Shigella infection by enhancing bacterial adhesion and invasion. Immunity 48, 1233–1244.e7 (2018).

Herrera, C. M. et al. The Vibrio cholerae VprA-VprB two-component system controls virulence through endotoxin modification. mBio 5, e02283–14 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Vibrio cholerae senses human enteric α-defensin 5 through a CarSR two-component system to promote bacterial pathogenicity. Commun. Biol. 5, 559 (2022).

Nie, D. et al. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) as a potential therapeutic target for Acinetobacter baumannii infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 27, 26 (2020).

Smani, Y., Dominguez-Herrera, J. & Pachón, J. Association of the outer membrane protein Omp33 with fitness and virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 1561–1570 (2013).

Kaur, D. & Mukhopadhaya, A. Outer membrane protein OmpV mediates Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells via fibronectin and α1β1 integrin. Cell Microbiol. 22, e13172 (2020).

Sperandio, V., Girón, J. A., Silveira, W. D. & Kaper, J. B. The OmpU outer membrane protein, a potential adherence factor of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 63, 4433–4438 (1995).

Nakasone, N. & Iwanaga, M. Characterization of outer membrane protein OmpU of Vibrio cholerae O1. Infect. Immun. 66, 4726–4728 (1998).

Xie, J., Haesebrouck, F., Van Hoecke, L. & Vandenbroucke, R. E. Bacterial extracellular vesicles: an emerging avenue to tackle diseases. Trends Microbiol. 31, 1206–1224 (2023).

Toyofuku, M., Schild, S., Kaparakis-Liaskos, M. & Eberl, L. Composition and functions of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 415–430 (2023).

Pardue, E. J. et al. Dual membrane-spanning anti-sigma factors regulate vesiculation in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2321910121 (2024).

Shoberg, R. J. & Thomas, D. D. Specific adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi extracellular vesicles to human endothelial cells in culture. Infect. Immun. 61, 3892–3900 (1993).

Karvonen, K., Tammisto, H., Nykky, J. & Gilbert, L. Borrelia burgdorferi outer membrane vesicles contain antigenic proteins, but do not induce cell death in human cells. Microorganisms 10, 212 (2022).

Wai, S. N. et al. Vesicle-mediated export and assembly of pore-forming oligomers of the enterobacterial ClyA cytotoxin. Cell 115, 25–35 (2003).

David, L. et al. Outer membrane vesicles produced by pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli block autophagic flux and exacerbate inflammasome activation. Autophagy 18, 2913–2925 (2022).

Davis, J. M., Carvalho, H. M., Rasmussen, S. B. & O’Brien, A. D. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 delivered by outer membrane vesicles of uropathogenic Escherichia coli attenuates polymorphonuclear leukocyte antimicrobial activity and chemotaxis. Infect. Immun. 74, 4401–4408 (2006).

Zingl, F. G. et al. Outer membrane vesicles of Vibrio cholerae protect and deliver active cholera toxin to host cells via porin-dependent uptake. mBio 12, e00534-21 (2021).

Elluri, S. et al. Outer membrane vesicles mediate transport of biologically active Vibrio cholerae cytolysin (VCC) from V. cholerae strains. PLoS ONE 9, e106731 (2014).

Tao, A. et al. ezCADD: a rapid 2D/3D visualization-enabled web modeling environment for democratizing computer-aided drug design. J. Chem. Inf. Model 59, 18–24 (2019).

Ren, Z. et al. Gut microbiota-CRAMP axis shapes intestinal barrier function and immune responses in dietary gluten-induced enteropathy. EMBO Mol. Med. 13, e14059 (2021).

Bagos, P. G., Liakopoulos, T. D., Spyropoulos, I. C. & Hamodrakas, S. J. PRED-TMBB: a web server for predicting the topology of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W400–W404 (2004).

Waterhouse, A. et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018).

McClean, S. et al. Linocin and OmpW are involved in attachment of the cystic fibrosis-associated pathogen burkholderia cepacia complex to lung epithelial cells and protect mice against infection. Infect. Immun. 84, 1424–1437 (2016).

Yamaoka, Y., Kwon, D. H. & Graham, D. Y. A M(r) 34,000 proinflammatory outer membrane protein (oipA) of Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7533–7538 (2000).

Bielaszewska, M. et al. Host cell interactions of outer membrane vesicle-associated virulence factors of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: intracellular delivery, trafficking and mechanisms of cell injury. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006159 (2017).

Baker-Austin, C. et al. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 4, 1–19 (2018).

Xu, C., Soyfoo, D. M., Wu, Y. & Xu, S. Virulence of Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins: an updated review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39, 1821–1830 (2020).

Negahdari, B., Sarkoohi, P., Ghasemi nezhad, F., Shahbazi, B. & Ahmadi, K. Design of multi-epitope vaccine candidate based on OmpA, CarO and ZnuD proteins against multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Heliyon 10, e34690 (2024).

Kothary, M. H. et al. Analysis and characterization of proteins associated with outer membrane vesicles secreted by Cronobacter spp. Front. Microbiol. 8, 134 (2017).

Theuretzbacher, U., Blasco, B., Duffey, M. & Piddock, L. J. V. Unrealized targets in the discovery of antibiotics for Gram-negative bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 957–975 (2023).

Singothu, S., Devsani, N., Jahidha Begum, P., Maddi, D. & Bhandari, V. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies of natural products unravel potential inhibitors against OmpA of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 42, 9064–9075 (2024).

Huttunen, S., Toivanen, M., Liu, C. & Tikkanen-Kaukanen, C. Novel anti-infective potential of salvianolic acid B against human serious pathogen Neisseria meningitidis. BMC Res Notes 9, 25 (2016).

Rodríguez-Pérez, C. et al. Antibacterial activity of isolated phenolic compounds from cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) against Escherichia coli. Food Funct. 7, 1564–1573 (2016).

Niehues, M. et al. Peptides from Pisum sativum L. enzymatic protein digest with anti-adhesive activity against Helicobacter pylori: structure-activity and inhibitory activity against BabA, SabA, HpaA and a fibronectin-binding adhesin. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 54, 1851–1861 (2010).

Getz, L. J. et al. Attenuation of a DNA cruciform by a conserved regulator directs T3SS1 mediated virulence in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 6156–6171 (2023).

Iwanaga, M. et al. Culture conditions for stimulating cholera toxin production by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Microbiol. Immunol. 30, 1075–1083 (1986).

Xu, T. et al. RNA-seq-based monitoring of gene expression changes of viable but non-culturable state of Vibrio cholerae induced by cold seawater. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 10, 594–604 (2018).

Cheng, A. T., Ottemann, K. M. & Yildiz, F. H. Vibrio cholerae response regulator VxrB controls colonization and regulates the Type VI secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004933 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. Extracellular vesicles of Fusobacterium nucleatum compromise intestinal barrier through targeting RIPK1-mediated cell death pathway. Gut Microbes 13, 1–20 (2021).

Mondal, A. et al. Cytotoxic and inflammatory responses induced by outer membrane vesicle-associated biologically active proteases from Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 84, 1478–1490 (2016).

Liu, B. et al. Escherichia coli O157:H7 senses microbiota-produced riboflavin to increase its virulence in the gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2212436119 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Vibrio cholerae virulence is blocked by chitosan oligosaccharide-mediated inhibition of ChsR activity. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 2909–2922 (2024).

Cañas, M.-A. et al. Outer membrane vesicles from the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and the commensal ECOR12 enter intestinal epithelial cells via clathrin-dependent endocytosis and elicit differential effects on DNA damage. PLoS ONE 11, e0160374 (2016).

Yang, H. et al. A novel mouse model of enteric Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection reveals that the Type III secretion system 2 effector VopC plays a key role in tissue invasion and gastroenteritis. mBio 10, e02608-19 (2019).

Hart, E. M. et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of BamA impervious to efflux and the outer membrane permeability barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 21748–21757 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Key R&D Program of China Grant 2024YFE0198900 (to Y.L.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Grants 32100144 (to Y.L.), 32370088 (to D.H.), 32170086 (to D.H.), 32170119(to X.J.); CMC Excellent-talent Program Grants 2024kjTzn01 (to X.J.); National Key Research and Development Program of China 2022YFC2305302 (to D.H.); and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2025M772657 to X.L.), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (grant no. GZC20251763 to X.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.L., D.H., and X.J. Methodology: Y.L., D.H., X.J., and R.L. Investigation: R.L., X.L. (Xingmei Liu), X.L. (Xueping Li), Y.H., J.Q., M.Z., T.W., and Y.P. Visualization: R.L., Y.H., Y.N., T.X., and Q.W. Supervision: Y.L. Writing-original draft: Y.L. Writing-review and editing: Y.L., D.H., X.J., R.L., and X.L. (Xingmei Liu).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kohei Yamazaki, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Liu, X., Li, X. et al. Small molecule inhibitor targets OmpV to treat pandemic Vibrio cholerae infection. Nat Commun 17, 826 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67532-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67532-8