Abstract

Van der Waals antiferromagnetic semiconductors are promising platforms for energy-efficient two-dimensional spintronics. However, their intrinsic spin degeneracy and the difficulty of achieving electrical spin control pose major challenges for practical device implementation. Here, we present a distinct spintronic platform based on an antiferromagnetic semiconductor CrSBr, in which carrier doping induced by gate-controlled intercalation drives a reversible, zero-field antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic phase transition, enabling direct and full electrical control of both magnetic order and spin polarization. Exploiting this transition, we engineer CrSBr/graphene heterostructures that leverage interfacial charge transfer to spatially pattern magnetic phases, resulting in lateral spin valves with gate-controlled spin polarization reversal, all without ferromagnetic contacts. Crucially, this mechanism also enables electrical switching of magnetic order via spin-transfer torque at ultralow current densities (<103 A/cm2), demonstrating its efficiency and device compatibility. These findings open a new paradigm for reconfigurable, all-electrical spintronic systems based on van der Waals antiferromagnetic semiconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pursuit of electrical control over magnetic order and spin polarization in quantum materials stands at the forefront of condensed matter physics, offering a pathway to energy-efficient spintronic devices for information storage and processing1,2,3,4. Layered van der Waals (vdW) magnets have recently emerged as a highly promising platform due to their gate-tunable magnetic states and tailorable interlayer interactions5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Among them, A-type collinear antiferromagnets are of particular interest for their unique combination of intralayer ferromagnetism and interlayer antiferromagnetic (AFM) coupling, which results in layer-locked spin-polarized bands with zero net magnetization13,14,15. Recent work has demonstrated that electric-field-induced symmetry breaking in even-layer CrPS4 can spin-polarize conduction bands13,14, although this method preserves the interlayer AFM order. A more effective form of spin control involves directly manipulating the coupling between layers to drive an interlayer AFM-to-ferromagnetic (FM) transition, where the phase change can drastically alter the global magnetic state. However, realizing such deterministic spin control at zero magnetic field via the AFM-to-FM transition remains experimentally challenging9,10,11,16,17,18.

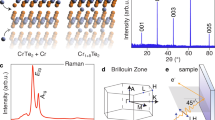

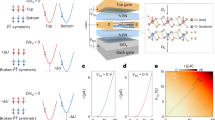

Carrier doping offers a powerful alternative for tuning magnetism and unlocking emergent quantum states, as illustrated in colossal magnetoresistance (MR) systems19 and high-temperature superconductors20. Electrical control of carrier concentration, in particular, has been implemented to modulate magnetic order8 via spin-charge coupling controlled by gating. A vdW semiconductor CrSBr (Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. S1), showing A-type AFM order (Fig. 1a), can host more dramatic doping responses: due to its weak interlayer coupling and strong charge-spin correlations16,21,22, doping CrSBr can directly induce both magnetic ordering and spin polarization. Theoretical calculations reveal a stark contrast between AFM and FM configurations in its spin-resolved density of states (DOS) (Fig. 1a, b): the AFM state exhibits spin degeneracy (net polarization P = 0), whereas the FM phase shows near-complete spin polarization at the conduction and valence band edges. Crucially, calculations of the AFM-FM energy difference (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S2) demonstrate that carrier doping stabilizes the FM state at experimentally accessible densities (1012 ~ 1014 cm2), aligning with previous predictions21, thus establishing carrier doping as an effective mechanism for modulating interlayer magnetic order and spin polarization.

a Schematic illustration of the layered A-type AFM state of CrSBr and corresponding spin-resolved DOS, exhibiting spin degeneracy (P = 0). b Schematic illustration of the layered FM state of CrSBr and corresponding spin-resolved DOS, showing spin asymmetry (P ≠ 0), which enables spin-polarized transport and tunable spin polarization. c Energy difference between the FM and AFM phases for trilayer CrSBr as a function of doping concentration, indicating that both electron and hole doping can induce the AFM-to-FM phase transition. d Our experimental strategy to enable electrical control of magnetic order and spin polarization in CrSBr: First, global carrier doping realizes a zero-field AFM-to-FM phase transition in CrSBr. Second, local doping by interfacial charge transfer from graphene induces confined magnetic order modulation, creating lateral spin-valve configurations with gate-tunable spin polarization. Third, ultralow-current spin-transfer torque manipulates the magnetic order in the CrSBr channel.

Guided by these insights, we demonstrate in situ electrical control of both magnetic order and spin polarization in CrSBr at zero external magnetic field. First, we use ionic gating to drive a reversible AFM-to-FM transition, manifested in distinct hysteretic MR signatures. Second, leveraging local interfacial charge transfer from graphene (Gr) contacts, we spatially modulate the magnetic order to form a lateral spin-valve configuration with gate-tunable spin polarization (Fig. 1d). Finally, we achieve electrical modulation of magnetic order in the lateral CrSBr channel via spin-transfer torque (STT) at ultralow current densities. These results together establish CrSBr as a versatile platform for all-electrical spintronics, enabling integrated control of magnetism and spins without relying on FM contacts23,24,25,26.

Results and Discussion

Zero-field magnetic phase transition driven by gate-controlled carrier doping

CrSBr is an air-stable A-type vdW AFM semiconductor with a band gap of ~1.5 eV27,28 and a high Neel temperature TN of ~132 K22,29,30. It exhibits intralayer FM ordering and AFM interlayer coupling, with the easy axis oriented along the b-direction (Fig. 1a)22,27,31. Previous attempts to modulate magnetism in CrSBr using conventional solid dielectrics have induced only modest changes in the coercive field of thin flakes16, while effective gate control in thicker flakes remains even more challenging. More recently, chemical lithium intercalation has been shown to induce an AFM-to-FM phase transition in bulk CrSBr32, highlighting the critical role of carrier doping in tuning its magnetic ground state. Here, we employ an electrically controlled ionic-liquid gating approach that enables reversible, high-density carrier accumulation and continuous control of the magnetic phase transition in CrSBr flakes, allowing systematic mapping of the phase diagram under electrostatic modulation.

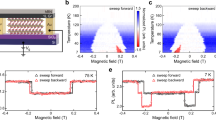

As illustrated in Fig. 2a, we first used LiClO4/PEO electrolyte as the ionic medium in our device (see Methods). The lithium intercalation was controlled by a liquid-gate voltage (VLG) to enable global carrier doping, monitored via room-temperature conductance measurements on a thick CrSBr device (~ 6 nm, Sample D1). At VLG = 6 V, the conductivity increases by over an order of magnitude (Fig. 2b). Pristine CrSBr exhibits semiconducting behavior, with conductance decreasing upon cooling and showing a local maximum near 132 K at VLG = 0 V (Fig. 2c). This maximum coincides with the onset of AFM ordering and is attributed to the associated suppression of spin-disorder scattering22. Upon intercalation doping (VLG = 6 V), the conductance maximum shifts to ~207 K, in consistent with earlier report32. In FM semiconductors, TC typically lies slightly above the conductance maximum33,34, as seen for monolayer CrSBr22. These results indicate that gate-controlled intercalation doping enables effective tuning of the magnetic phase and also increases the magnetic ordering temperatures.

a Schematic of the device structure by ionic gating. The ionic media LiClO4/PEO is chosen for global intercalation doping. b Conductance versus gate for a thick CrSBr device (Sample D1) at 300 K, showing more than one order of magnitude increase in conductivity after 6 V intercalation. c Temperature-dependent conductance at 0 V and 6 V, revealing a 75 K shift of the characteristic local maximum from the original Néel temperature (132 K). d \({\rm{MR}}\) measured at 2 K, where undoped state (0 V) shows AFM -like behavior and doped state (6 V) exhibits FM-like hysteresis, with zero-field resistance matching that at 1 T. e Magnetization (M) curves extracted from the MR data using micromagnetic simulations, confirming AFM (0 V) and FM (6 V) states. f Left and middle panels: MR difference \(\varDelta {MR}\) as functions of temperature and magnetic field for AFM and FM states, revealing a Néel temperature of ~132 K for AFM and a Curie temperature above 180 K for FM. Right panel: Coercive field (Bc) evolution with temperature, highlighting distinct thermal behaviors of the AFM and FM states.

To further verify this magnetic transition, we performed the MR measurements with the external magnetic field (B) sweeping along the easy axis (b-direction) at different liquid-gate voltages and temperatures. The systematic evolution of MR is provided in Supplementary Fig. S3. We define the relative MR as \({MR}\%=\frac{R\left(B\right)-R\left(0{{\rm{T}}}\right)}{R\left(0{{\rm{T}}}\right)}\times 100\%\). As shown in Fig. 2d, the MR at VLG = 0 V primarily decreases sharply at a coercive field of ~ 0.4 T, consistent with a field-induced FM transition superimposed on an AFM ground state, where antiparallel interlayer spins suppress electron hopping. In contrast, following intercalation at 6 V, the AFM signature vanishes, and the MR exhibits a butterfly-shaped hysteresis with zero-field resistance matching that at 1 T, indicating the formation of a stable FM ground state with the magnetic easy axis preserved along b-direction21,32. These changes underscore the strong sensitivity of MR to the underlying magnetic structure22,31,35. The gate-dependent MR features thus provide direct evidence for an AFM-to-FM transition driven by intercalation-induced carrier doping. Due to the in-plane spin orientation and pronounced transport anisotropy in CrSBr, direct Hall measurements to extract magnetization were not feasible27,29,30. Instead, as shown in Fig. 2e, micromagnetic simulations fitted to our MR data (also see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. S4) confirm the AFM and FM behaviors. Furthermore, temperature-dependent MR difference measurements (\({{\rm{defined}}}\; {{\rm{as}}}\;{\varDelta {MR}=M{R}}_{{forward}}\%-M{R}_{{backward}}\%\)) reveal distinct thermal evolutions of the coercive field (Bc) and an enhanced critical temperature (TC) for the AFM and FM states (Fig. 2f). As the magnitude of interlayer exchange coupling is smaller than intralayer ones by about two orders of magnitude (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Table S2), this increase in TC primarily arises from electron-doping-enhanced intralayer effective exchange interactions in CrSBr as supported by our first-principles calculations (Supplementary Figs. S5, S6), underscoring the effective thermal stabilization of FM order through carrier doping32.

Local magnetic order modulation and gate-controlled spin-valve behavior

Having confirmed carrier doping as the mechanism for modulating the magnetic order in CrSBr, we next employ the local-doping strategy that exploits interfacial charge transfer from graphene to spatially modulate the magnetic order of pristine CrSBr. This approach enables spin injection and detection through separated doping-induced FM regions and the resulting spin-filtering effect. Figure 3a, b show the schematic and optical image of our CrSBr/Gr heterostructure device (Sample D2), where two graphene stripes serve as electrodes and the global back-gate voltage VG is applied to the doped Si substrate. The CrSBr flake is identified as a trilayer based on optical contrast and atomic force microscopy (Methods, Supplementary Fig. S1), with a channel length of ~1 μm along the a-axis. Theoretical studies predict strong charge transfer at the CrSBr/Gr interface, leading to effective electron doping capable of inducing an AFM-to-FM transition in thin-layer CrSBr21 (also see Fig. 1c). To verify this in our device, we compared the transfer curves of pristine graphene with graphene in contact with CrSBr, as shown in Fig. 3c. The CrSBr/Gr interface induces a 73 V shift in graphene’s charge neutrality point, corresponding to a large charge transfer of ~ 5.5 × 1012 cm−2 (calculated from the 285 nm SiO2 gate capacitance and typically required high quality interface between graphene and CrSBr). This substantial charge transfer is sufficient to locally induce FM order21 at the two graphene-contacted regions, creating a lateral FM/AFM/FM configuration that supports a spin-valve effect for verifying spin polarization modulation.

a Schematic of the CrSBr lateral spin-valve with graphene contacts on a 285 nm SiO2/Si substrate. The global back-gate voltage VG is applied to the doped Si substrate; VDS is applied between the graphene source and drain electrodes. b Optical image of a trilayer CrSBr device with graphene contacts (Sample D2). Scale bar: 5 μm. c Transfer curves of the pristine graphene and graphene in contact with the CrSBr flake in Sample D2 measured at 2 K. d MR of the same CrSBr device measured with VDS = 0.48 V and VG = - 40 V at 2 K. The inset cartoons illustrate the corresponding magnetic configurations for resistance states “0” to “4” as the magnetic field sweeps forward (red curve) along the b-axis. The coercive field of the source Gr/CrSBr contact slightly differs from that of the drain contact, forming parallel (state “1” or “3”) and antiparallel (state “2”) magnetic configurations as the field sweeps, thus causing the spin-valve effect. e Spin-valve MR of the same device as VG changes from - 90 V to 80 V with a fixed VDS = 0.48 V, at 2 K with magnetic field B oriented along the b-axis. It clearly shows a sign change of the spin-valve MR when adjusting VG across - 72 V.

To demonstrate the resulting spin-valve behavior, we performed magneto-transport measurements at 2 K. Figure 3d presents the MR data measured using two graphene contacts under a bias voltage of \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\) = 0.48 V and a gate voltage \({V}_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) = - 40 V. During the magnetic field sweeps, an MR transition appears at a coercive field of ~ ± 0.35 T, labeled “AFM MR”, indicating spin flipping in the CrSBr channel from an AFM to an FM state22,27,36. Within the high-resistance plateau of the AFM ordering, abrupt drops in resistance occur near ± 0.2 T, depending on the sweep direction. These hysteretic drops are characteristic of spin-valve behavior28,37 (denoted as “spin-valve MR”) in our CrSBr device with graphene contacts. In the inset of Fig. 3d, we label discrete resistance states “0” to “4” and illustrate the corresponding magnetic states for the forward sweep of magnetic field (red curve). The associated spin configurations in the CrSBr layers are discussed in Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. S7. We note that the spin-valve behavior is also reproducible when the field sweep is confined within ± 0.3 T (Supplementary Fig. S7b). Finally, control experiments using Au-Au and Gr-Au contacts (Supplementary Fig. S8) do not exhibit similar spin-valve MR, confirming that the observed spin-valve behavior arises intrinsically from the lateral configuration created by local charge transfer from graphene. More discussion is provided in Supplementary Note 5 and Fig. S9.

More importantly, this spin-valve behavior is fully gate-tunable, featuring a sign reversal of the spin-valve MR that confirms electrical control of the spin polarization in our CrSBr device. We performed MR measurements at different gate voltages over a magnetic field sweep of ± 1 T (Supplementary Fig. S10) and the central ± 0.3 T window is shown in Fig. 3e. At a fixed VDS = 0.48 V, positive spin-valve MR is observed at \({V}_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) = - 90 and - 80 V, followed by complete suppression at a critical gate bias of \({V}_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) = - 72 V. Adjusting VG across the critical point restores the spin-valve MR with a reversed sign as VG is increased from −90 to 80 V. Similar gate tunability is observed at VDS = 0.4 V (Supplementary Fig. S11). In another CrSBr device (Sample D3) that is encapsulated with hBN and equipped with a high-k dielectric, the gate tunability is further enhanced, allowing the positive spin-valve MR to be modulated from 36% to nearly zero by increasing VG from -2 to 0 V (Supplementary Fig. S12). Such robust gate control represents a significant advance over the conventional spin-valve devices that rely on FM metal contacts24.

Gate-tunable spin polarization in CrSBr/Gr heterostructure

We attribute the sign reversal of the spin-valve MR near VG = −72 V (Fig. 4a) to the gate-tunable spin polarization of the two CrSBr/Gr electrodes under a large bias. The spin polarization of each electrode is determined by the distribution of spin-resolved electronic states within the transport energy window defined by its local electrochemical potential. Under a finite bias VDS, these transport windows are offset between the two contacts and can be rigidly shifted together by the global gate VG, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S13. When the dominant spin species within the respective energy windows differ, the two electrodes acquire opposite spin polarization. As illustrated in Fig. 4b, the net spin polarization of each CrSBr/Gr electrode thus depends jointly on \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\) and \({V}_{{{\rm{G}}}}\). When VG < −72 V, both electrodes exhibit positive spin polarization (left panel of Fig. 4b), resulting in a low-resistance state for the parallel alignment of their magnetizations (states “1” or “3”), and a high-resistance state for the antiparallel alignment (state “2”). Once \({V}_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) exceeds the critical bias, the electrodes acquire opposite spin polarizations (right panel of Fig. 4b), inverting the resistance state. Consequently, the sign of the spin-valve MR is determined by the product of the spin polarization of two electrodes (P1 and P2), assuming that spin polarization remains unchanged during spin diffusion through the channel.

a Spin-valve MR (extracted from Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. S8 for Sample D2) as a function of VG for VDS = 0.48 V and 0.40 V, respectively. b Illustration of the MR states depending on spin polarization and magnetic configurations of the CrSBr/Gr contacts. P1 > 0 and P2 > 0 at VG < −72 V, so the matched spin channels in the parallel configuration (state “1” or “3”) lead to a low-resistance (R) state. Conversely, it exhibits a higher resistance in the antiparallel configuration (state “2”). The situation reverses when P1 < 0 and P2 > 0 at VG > −72 V with the same bias. c Calculated spin polarization P of DOS as a function of energy for CrSBr/Gr heterostructures with various layer thicknesses, including one layer of CrSBr and one layer of graphene (1 CrSBr/1 Gr), 1 CrSBr/2 Gr, 1 CrSBr/3 Gr, and 2 CrSBr/3 Gr. The spin polarization is nearly insensitive to the thickness of all these heterostructures. d Calculated spin-valve MR under an AC bias of VDS = 0.48 V. The sign of spin valve MR is determined by the spin polarization product (P1P2) of two CrSBr/Gr contacts. The vertical dashed line marks the MR sign reversal at E = 0.28 eV, quantitatively matching with experimental results and confirming gate-controlled spin polarization reversal.

To further elucidate this behavior, we calculated the spin polarization P for the CrSBr/Gr heterostructures with various layer thicknesses using density functional theory (Fig. 4c). The corresponding band structures for different CrSBr/Gr configurations are shown in Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Fig. S14. These calculations reveal that the spin polarization is nearly insensitive to the thickness of graphene or CrSBr, highlighting its robustness across a wide range of device parameters. Figure 4d presents the calculated MR, which scales with \({P}_{1}{P}_{2}=P(E)[P(E+e{V}_{{\rm{DS}}})+P(E-e{V}_{{\rm{DS}}})]/2\), where \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\) = 0.48 V is the AC bias between the two CrSBr/Gr electrodes, and E is the electrochemical potential of the drain-side CrSBr/Gr electrode. The gate voltage simultaneously shifts the Fermi levels of both electrodes, leading to a sign reversal in calculated MR when the Fermi level moves to ~ 0.28 eV (dashed line in Fig. 4d). By estimating the carrier density in graphene under these conditions, we find excellent quantitative agreement with the experimental data (Fig. 3c), where the spin-valve MR sign reverses at \({V}_{\rm{{G}}}\) = - 72 V(Supplementary Note 7). This result confirms that the gate modulation can fully reverse the spin polarization in our CrSBr spin-valve device, demonstrating large tunability.

Electrical manipulation of magnetic order through STT

We also observe a pronounced STT effect in the lateral CrSBr channel, enabled by large spin-polarized current injected through doping-induced FM contact regions. STT transfers spin angular momentum, thereby altering the magnetic order of the CrSBr channel. To confirm this, we measured the MR at 2 K over a range of VDS, as shown in Fig. 5a. With VG = 0 V, the current increases nonlinearly from 18 to 856 nA as \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\) is raised from 0.2 to 0.51 V, while the spin-valve MR remains nearly constant. In contrast, the AFM MR gradually diminishes and eventually vanishes at higher \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\).

a Bias voltage (VDS)-dependent MR of the CrSBr device (Sample D2) measured at 2 K with a fixed VG = 0 V. The AFM MR diminishes while the spin-valve MR persists as VDS increases, indicative of the STT effect within the CrSBr channel. b The AFM MR and the spin-valve MR as a function of VDS, with the top axis representing the corresponding source-drain current density jDS. c Schematic of STT-driven magnetic order manipulation in the lateral CrSBr channel for small (top) and large (bottom) jDS. The intensified spin current enhances STT effects, switching the CrSBr channel from initial AFM order (blue region) to the FM order (red region). d MR of the same device measured at various temperatures from 2 K to 150 K with VDS = 0.2 V and VG = 0 V, illustrating the disappearance of the spin-valve MR near 10 K. e Bias voltage-dependent MR of the same device measured at 10 K with VG = 0 V. The AFM MR decreases with increasing VDS, further supporting the presence of the STT effect at elevated temperatures.

Figure 5b presents the evolution of the AFM and spin-valve MR with \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\). Theoretical calculations indicate that the spin polarization of CrSBr/Gr heterostructure remains nearly unchanged over this bias range (Supplementary Fig. S15). Hence, we attribute the disappearance of the AFM MR to the increased spin current density, which amplifies the STT in the channel and drives an AFM-to-FM magnetic order switching (Fig. 5c). As expected, adjusting the DC bias voltage can also modulate the magnetic state via STT, as confirmed in Samples D2 (Supplementary Fig. S16) and D3 (Supplementary Fig. S17). To validate this STT mechanism, we performed control experiments on CrSBr devices with Au electrodes (Supplementary Fig. S18). Increasing the current in these devices does not suppress the AFM MR, confirming that the STT effect is unique to our device configuration with graphene contacts. Such STT-driven magnetic order manipulation is rarely observed in lateral spin-transport devices using two-dimensional (2D) magnetic materials or thin magnetic films38,39.

We estimate that the threshold current density (jDS) required to induce STT in our devices is less than 103 A/cm2 (top axis of Fig. 5b, also see Supplementary Note 8 and Table S1), which is more than an order of magnitude lower than previously reported spin-torque thresholds in lateral structures38,40. This reduction likely stems from the clean vdW interfaces in our heterostructures, which minimize pinning centers relative to conventional FM-metal interfaces. Recent reports of layer-sharing lateral exchange bias effect in CrSBr also support our scenario of low current STT41.

We further explored the temperature dependence of the MR at \({V}_{{\rm{DS}}}\) = 0.2 V and \({V}_{{\rm{G}}}\) = 0 V from 2 to 150 K (Fig. 5d). The AFM coercive field decreases as the temperature is increased, and the AFM MR persists up to ~ 130 K, consistent with previous reports22,27,29,31. In contrast, the spin-valve MR vanishes near 10 K, presumably due to a reduced spin diffusion length at elevated temperatures. As shown in Fig. 5e, the AFM MR decreases whereas the coercive field remains unchanged with increasing \({V}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\) at 10 K, confirming that STT effects persist at elevated temperatures and ruling out purely thermal influences. Meanwhile, the emergence of positive MR in perpendicular fields and butterfly-shaped MR signals with parallel fields at higher VDS (Supplementary Fig. S9c and Fig. S19) further supports an STT-induced FM order. Similar butterfly-shaped MR signals also appear on the high-resistance AFM plateau when the temperature exceeds 10 K (Supplementary Fig. S20), indicating the coexistence of FM and AFM order42 in the CrSBr. This temperature-dependent spin-valve and MR behavior is likewise observed in a four-layer CrSBr device with graphene electrodes (Sample D4, Supplementary Fig. S21), underscoring the versatility and effectiveness of our approach for realizing gate-tunable lateral spin valves without conventional FM contacts.

In summary, we demonstrate that carrier doping serves as an effective and versatile mechanism for controlling both magnetic order and spin polarization in a single vdW antiferromagnet, CrSBr. By leveraging the strong coupling between charge density and interlayer exchange interactions, we achieve a deterministic and reversible AFM-to-FM phase transition at zero magnetic field. Complementary approaches of interfacial charge transfer and STT enable spatial and dynamic modulation of magnetic states, expanding the tunability of this system. Notably, we realize lateral spin-valve configurations with gate-controlled spin polarization reversal and large tunability, all without relying on FM contacts. Furthermore, the low current densities (<103 A/cm2) required for STT-driven switching point to the potential for energy-efficient spintronic operation. Together, these findings highlight CrSBr as a promising model system for all-electrical spintronic devices, integrating multiple spin functionalities within a single gate-tunable material.

Methods

Sample growth and device fabrication

High-quality CrSBr single crystals were successfully synthesized via the chemical vapor transfer (CVT) method, using high-purity chromium metal powder, sublimated sulfur powder, and liquid bromine as precursors. The growth conditions and steps are described in detail in Supplementary Note 1. We used a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp-assisted mechanical exfoliation technique to prepare CrSBr thin flakes in air. The layer number of the flakes was determined by height profiling using an atomic force microscope and observing optical contrast in optical micrographs (Supplementary Fig. S1).

CrSBr devices with graphene contacts were fabricated using a PC-based dry- transfer technique43. To ensure high-quality, bubble-free CrSBr/Gr interfaces, we adopted an additional thermal expansion-contraction control step during the transfer process. The PC film was heated to 150 °C for adhesion and slowly cooled to 60 °C for controlled release, while repeated mild thermal cycles during the drop-down process eliminated trapped bubbles. Finally, the PC layer was dissolved in trichloromethane to obtain a clean, residue-free interface. Typical CrSBr flakes are in a ribbon shape, with long and short edges corresponding to the a and b crystal axes, respectively. The CrSBr thin flakes were stacked onto the graphene electrodes on 285 nm SiO2/Si substrates with long edges aligned vertically to the graphene stripes. Subsequently, Cr/Au (5/70 nm) electrodes were defined and thermally evaporated onto CrSBr or graphene using a standard electron-beam lithography process.

Electrical transport measurements

The ionic medium LiClO4/PEO polymer electrolyte was applied to the top of the thin flake and the side gate electrode for ionic gating. The device configuration is illustrated in Fig. 2a. LiClO4 and PEO powders (0.3 g and 1 g, respectively) (PEO; Mw = 100,000) were mixed with 15 ml anhydrous methanol (Alfa Aesar). The mixture was then stirred overnight with the temperature kept at 50 °C44. The global intercalation doping is controlled by adjusting the gate voltage and its doping effect is monitored by measuring the conductivity of the CrSBr device at room temperature.

Low-temperature transport measurements down to 2 K were performed in a commercial Cryogenic Superconducting Magnet System (1.6–300 K, 12 T). Longitudinal resistance was measured in a two-terminal configuration, using an SR830 lock-in amplifier combined with an SR570 current amplifier for sourcing voltage and measuring current at a reference frequency of 17.77 Hz. For DC measurements, a Keithley 2636 A was used to source voltage and measure current. Gate-dependent measurements were conducted using a Keithley 2400 to apply voltages to the gates.

Theoretical calculations

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations, implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)45, to determine the carrier-doping-dependent energy difference between collinear FM and AFM states of CrSBr, as well as the electronic structure of the CrSBr/Gr heterostructures. The projector-augmented wave (PAW) method46 was employed to describe the interaction between ions and electrons. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)47 was used to treat the exchange-correlation effects. Further details of the theoretical calculations are provided in Supplementary Note 5. We also verified that including the vdW interactions produces negligible changes in the calculated results presented here.

The magnetic properties of CrSBr under carrier doping were systematically investigated through a combination of experimental measurements and computational modeling. Magnetization curves were reconstructed from MR data using established anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) and giant magnetoresistance (GMR) frameworks, providing a non-destructive approach to quantitatively track the evolution of magnetization under different magnetic fields. To complement our experiments, we performed Monte Carlo simulations of the CrSBr system using an extended Heisenberg Hamiltonian that incorporates both intralayer and interlayer exchange interactions35. The experimental and computational results demonstrated consistent results of magnetization curves. Further details of these theoretical calculations are provided in Supplementary Note 5 and Fig. S2.

Data availability

The Source Data underlying the figures of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30630737. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323–410 (2004).

Datta, S. & Das, B. Electronic analog of the electro-optic modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 56, 665–667 (1990).

Chuang, P. et al. All-electric all-semiconductor spin field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 35–39 (2015).

Datta, S., Salahuddin, S. & Behin-Aein, B. Non-volatile spin switch for boolean and non-boolean logic. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 252411 (2012).

Huang, B. et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 546, 270–273 (2017).

Gong, C. et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265–269 (2017).

Yang, H. et al. Two-dimensional materials prospects for non-volatile spintronic memories. Nature 606, 663–673 (2022).

Deng, Y. et al. Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018).

Jiang, S., Li, L., Wang, Z., Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Controlling magnetism in 2D CrI3 by electrostatic doping. Nat. Nanotech. 13, 549–553 (2018).

Huang, B. et al. Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 544–548 (2018).

Fu, Z. et al. Tunneling current-controlled spin states in few-layer van der Waals magnets. Nat. Commun. 15, 3630 (2024).

Jiang, S., Li, L., Wang, Z., Shan, J. & Mak, K. F. Spin tunnel field-effect transistors based on two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Electron. 2, 159–163 (2019).

Yao, F. et al. Switching on and off the spin polarization of the conduction band in antiferromagnetic bilayer transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 609–616 (2025).

Gong, S. J. et al. Electrically induced 2D half-metallic antiferromagnets and spin field effect transistors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8511–8516 (2018).

Liu, G. & Ke, S.-H. Electronic and transport engineering of A-type antiferromagnets with ferroelectric sandwich structure: toward multistate nonvolatile memory applications. Nano Lett. 24, 10776–10782 (2024).

Tabataba-Vakili, F. et al. Doping-control of excitons and magnetism in few-layer CrSBr. Nat. Commun. 15, 4735 (2024).

Cenker, J. et al. Reversible strain-induced magnetic phase transition in a van der Waals magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 256–261 (2022).

Jo, J. et al. Nonvolatile electric control of antiferromagnet CrSBr. Nano Lett. 24, 4471–4477 (2024).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Orbital physics in transition-metal oxides. Science 288, 462–468 (2000).

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba−La−Cu−O system. Eur. Phys. J. B. 64, 189–193 (1986).

Xie, K., Zhang, X. W., Xiao, D. & Cao, T. Engineering magnetic phases of layered antiferromagnets by interfacial charge transfer. ACS Nano 17, 22684–22690 (2023).

Telford, E. J. et al. Coupling between magnetic order and charge transport in a two-dimensional magnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 21, 754–760 (2022).

Crooker, S. A. et al. Imaging spin transport in lateral ferromagnet/semiconductor structures. Science 309, 2191–2195 (2005).

Tombros, N., Jozsa, C., Popinciuc, M., Jonkman, H. T. & van Wees, B. J. Electronic spin transport and spin precession in single graphene layers at room temperature. Nature 448, 571–574 (2007).

Lou, X. et al. Electrical detection of spin transport in lateral ferromagnet–semiconductor devices. Nat. Phys. 3, 197–202 (2007).

Koo, H. C. et al. Control of spin precession in a spin-Injected field effect transistor. Science 325, 1515–1518 (2009).

Telford, E. J. et al. Layered antiferromagnetism induces large negative magnetoresistance in the van der Waals semiconductor CrSBr. Adv. Mater. 32, e2003240 (2020).

Ghiasi, T. S. et al. Electrical and thermal generation of spin currents by magnetic bilayer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 788–794 (2021).

Wilson, N. P. et al. Interlayer electronic coupling on demand in a 2D magnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 20, 1657–1662 (2021).

Wu, F. et al. Quasi-1D electronic transport in a 2D magnetic semiconductor. Adv. Mater. 34, e2109759 (2022).

Boix-Constant, C. et al. Probing the spin dimensionality in single-layer CrSBr van der Waals heterostructures by magneto-transport measurements. Adv. Mater. 34, e2204940 (2022).

Feuer, M. L. et al. Charge density wave and ferromagnetism in intercalated CrSBr. Adv. Mater. 37, 2418066 (2025).

Alexander, S., Helman, J. S. & Balberg, I. Critical behavior of the electrical resistivity in magnetic systems. Phys. Rev. B 13, 304–315 (1976).

Balberg, I. & Helman, J. S. Critical behavior of the resistivity in magneticsystems. II. Below Tc and in the presence of a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 18, 303–318 (1978).

Boix-Constant, C. et al. Multistep magnetization switching in orthogonally twisted ferromagnetic monolayers. Nat. Mater. 23, 212–218 (2023).

Majumdar, P. & Littlewood, P. B. Dependence of magnetoresistivity on charge-carrier density in metallic ferromagnets and doped magnetic semiconductors. Nature 395, 479–481 (1998).

Appelbaum, I., Huang, B. & Monsma, D. J. Electronic measurement and control of spin transport in silicon. Nature 447, 295–298 (2007).

Wang, Q. et al. Magnetism modulation in Co3Sn2S2 by current-assisted domain wall motion. Nat. Electron. 6, 119–125 (2022).

Buhl, M. et al. Lateral spin transfer torque induced magnetic switching at room temperature demonstrated by x-ray microscopy. Sci. Rep. 3, 2945 (2013).

Fong, X. et al. Spin-transfer torque devices for logic and memory: prospects and perspectives. IEEE Trans. Comp.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 35, 1–22 (2016).

Sun, Z. et al. Resolving and routing magnetic polymorphs in a 2D layered antiferromagnet. Nat. Mater. 24, 226–233 (2025).

Deng, Y. et al. Quantum anomalous hall effect in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Science 367, 895–900 (2020).

Lin, Y.-C. et al. Clean transfer of graphene for Isolation and suspension. ACS Nano 5, 2362–2368 (2011).

Yu, Y. et al. Gate-tunable phase transitions in thin flakes of 1T-TaS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 270–276 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yuanbo Zhang, Mingyuan Huang and Weichao Yu for their helpful discussions. Part of the sample fabrication was performed at the Fudan Nanofabrication Laboratory. This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFB3614103 (W.S.), No. 2024YFA1409003 (W.S.), No. 2021YFA1400400 (J.-W.M.)), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12574187 (W.S.), No. 12274090 (W.S.), No. 12574115 (Z.Y.), No. 12374101 (Y.L.), No.12474143 (J.-W.M.) and No. 62274087 (J.-W.M.)), the Shenzhen Fundamental Research Program (Grant No. JCYJ20220818100405013 (J.-W.M.) and JCYJ20230807093204010 (J.-W.M.)), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant No. RCYX20221008092848063 (J.-W.M.)) and Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative (GDZX2401010 (J.-W.M.)). J.T.Y. acknowledges the Project TOPCORE (with project number OCENW.GROOT.2019.048) of the research programme Open Competition ENW Groot, which is (partly) financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and the research program ‘Materials for the Quantum Age' (QuMat) for financial support. This program (registration number 024.005.006) is part of the Gravitation program financed by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.S. conceived and supervised the project. Q.L., Y.C., and J.-W.M. grew the CrSBr bulk crystals. G.R.Z., Y.B.Z, K.L.Y., Z.J.G., J.Q.L., and T.Y.Z. fabricated the devices and performed transport measurements. W.S., G.R.Z., Y.B.Z, Z. W., C. Z., J.-W.M., and Z.Y. analyzed the data, Z.Y., Y.L., Y. Z., K.Y., and X.B.C. carried out theoretical calculations. W.S., G.R.Z., J.T.Y., J.-W.M., and Z.Y. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pritam Deb and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, G., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y. et al. Doping-induced magnetic phase transition enables all-electrical spin control in CrSBr. Nat Commun 17, 853 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67561-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67561-3