Abstract

In this phase 2 trial, patients diagnosed with locally advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma underwent three cycles of neoadjuvant therapy comprising serplulimab, carboplatin, and albumin paclitaxel. The primary endpoint was the pathological complete response assessed by two independent pathologists and was defined as no residual viable tumours at both the primary tumour site and all the lymph nodes. The secondary endpoints included adverse events and overall survival time. In total, 85.4% of patients experienced adverse events of any grade, and 4.2% reported Grade 3 adverse events; 45 patients underwent pathological evaluation, 14 (31.1%, 95% confidence interval, 18.2–46.6%) achieved pathological complete response, and the two-year survival rate was 88.3%. Imaging mass cytometry revealed that patients without pathological complete response presented immunosuppressive molecule expression, and expanded immunosuppressive fibroblast neighbourhoods. Here we show, serplulimab and chemotherapy are associated with modest antitumour activity and a tolerable safety profile in patients with locally advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. A phase 3 randomised trial featuring continued follow-up is essential for a formal evaluation. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05659251.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most prevalent histological form of oesophageal cancer is oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), which accounts for more than 80% of cases1,2. Because early-stage ESCC has few clinical symptoms, the majority of patients are often diagnosed at a more advanced stage, leading to relatively poor survival rates despite the application of multimodal treatment strategies3,4. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery is the principal therapeutic approach used for potentially resectable ESCC5. However, recent multicentre evidence indicates that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by surgery, yield comparable 3-year survival rates of 64.1% and 54.9%, respectively6. In alignment with findings from the JCOG1109 NExT trial, the addition of radiotherapy to doublet chemotherapy did not lead to a significant increase in survival rates compared with doublet chemotherapy alone, and the 3-year survival rate was significantly greater for patients receiving triplet chemotherapy (72.1%) than for those receiving doublet chemotherapy (62.6%), with no significant difference observed in patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (68.3%)7. Therefore, there is a pressing need to explore additional multimodal neoadjuvant therapeutic strategies for the treatment of locally advanced ESCC. In recent years, immunotherapy for resectable ESCC patients has evolved from adjuvant treatment to neoadjuvant therapy8,9. This change offers a new treatment approach for patients with locally advanced ESCC. Theoretically, neoadjuvant immunotherapy, which functions by inhibiting the immune evasion of tumour cells and enhancing the capacity of the immune system to eradicate these cells through activation of the immune response10, has the potential to reduce the risk of postoperative recurrence and improve survival rates. Nevertheless, the considerable variability in treatment response presents a significant challenge, with the spatial heterogeneity of the tumour microenvironment (TME) and dynamic immunosuppressive mechanisms being critical determinants of immunotherapy efficacy11. Therefore, the integration of high-dimensional spatial omics is imperative for elucidating the mechanisms underlying the diverse responses to immunotherapy.

In patients with advanced ESCC, the combination of serplulimab (HLX10, a fully human anti-PD-1 antibody) and chemotherapy is associated with favourable antitumour activity and manageable safety as an initial treatment, as evidenced by ASTRUM-0072. Serplulimab combined with chemotherapy has been approved as a first-line treatment for advanced ESCC in China. In addition, the combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy has been shown to have synergistic antitumour effects on ESCC in several studies12,13. Imaging mass cytometry (IMC) integrates mass spectrometry with cytometry to visualise and quantify multiple proteins at the single-cell level within tissue sections, offering valuable insights into the TME in cancer research14,15. Although the IMC technique has been utilised in neoadjuvant immunotherapy for locally advanced ESCC16, there remains a paucity of research employing this method to compare pathological complete response (PCR) and non-PCR patients. Furthermore, studies are needed to investigate the functional relationships between spatial multicellular interaction patterns and the potential identification of cell phenotypes that may predict the efficacy of immunotherapy in locally advanced ESCC.

Here, we show this phase 2 trial investigates the efficacy and safety of a combination of serplulimab with chemotherapy alongside subsequent minimally invasive oesophagectomy for locally advanced ESCC.

Results

Patient and surgery summary

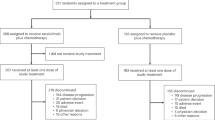

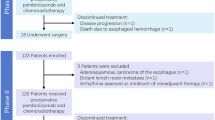

A total of 55 patients were evaluated between December 1, 2022, and October 31, 2024 (Fig. 1). Seven patients were excluded for having either unresectable tumours or a history of other tumours; 48 patients were successfully enroled in this study and received treatment. Three patients completed the neoadjuvant therapy but subsequently refused to receive surgery and declined to continue participating in the study. Thus, a total of 45 patients who underwent oesophagostomy were evaluated to determine pathological efficacy and survival outcomes.

As detailed in Table 1, the average age of the enroled patients was 64.5 years, with more than half (52.1%) of the patients being older than 65 years. Prior to neoadjuvant treatment, 27 patients (56.3%), 19 patients (39.6%), and 2 patients (4.2%) were diagnosed with clinical stages II, III, and IVA disease, respectively.

As shown in Table 2, the mean duration between the last neoadjuvant therapy and surgery was 33.7 days, and there were no surgical delays related to neoadjuvant treatment. A total of 28 patients (62.2%) underwent the minimally invasive Ivor‒Lewis procedure, whereas 17 patients (37.8%) underwent the minimally invasive McKeown procedure. The median operative duration was 240 minutes, with a median blood loss of 50 mL, and the median number of resected lymph nodes was 33. In addition, no patients required conversion to open surgery, and all patients successfully achieved R0 resection. The major postoperative complications included anastomotic leakage and vocal cord paralysis, each of which occurred in two patients (4.4%). One patient suffered from chylothorax and underwent reoperation, followed by unexpected admission to the intensive care unit. No mortality was observed within the 90-day postoperative period in this study. Following surgery, 46.7% of patients opted for maintenance therapy with serplulimab, 37.8% of patients selected a combination of serplulimab and chemotherapy, and 4.4% of patients selected a combination of serplulimab and radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment. In contrast, 11.1% of patients did not receive any further adjuvant therapy.

Efficacy

No patients experienced disease progression during neoadjuvant treatment. Among these patients, three patients (6.2%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3–17.2%) achieved a complete response, 30 patients (62.5%; 95% CI, 47.4–76.0%) achieved a partial response, and 15 patients (31.2%, 18.7–46.3%) had stable disease. Therefore, the disease control rate was 100.0% (95% CI, 92.6–100.0%), and objective responses were observed in 33 patients (68.8%; 95% CI, 53.7–81.3%) (Table 2).

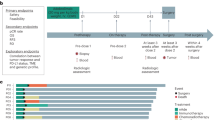

Among the 45 patients who underwent pathological evaluation (Fig. 2A), 19 (42.2%) patients had lymph node metastasis, and 22 (48.9%) patients had a lower stage than the clinical stage. Fourteen patients (31.1%; 95% CI, 18.2–46.6%) exhibited a PCR (ypT0N0), whereas the other 31 patients (68.9%; 95% CI, 53.4–81.8%) did not exhibit a PCR (Table 2). Among these patients, 4 patients exhibited PCR for the primary tumour but also had positive lymph nodes (ypT0N1-3). With respect to the data cut-off on April 1, 2025, the median follow-up duration was 18.1 months, during which 45 patients completed the follow-up. The median survival, event-free survival time and disease-free survival times were not reached. A total of four patients died, and three fatalities were attributed to distant metastasis (specifically, one due to liver metastasis and two due to multiple metastases). The overall survival rate at two years was 88.3% (Fig. 2B). Notably, no patients in the PCR group died, whereas the two-year survival rate in the non-PCR group was 84.3%, with no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.219) (Fig. 2C). During follow-up, 2 patients experienced local recurrence, and 3 patients experienced distant metastasis. The event-free survival rate at two years was 82.4% (Fig. S1A), and the disease-free survival rate at two years was 82.7% (Fig. S1B).

A Clinical metadata and analyses for each patient, including smoking and drinking status, clinical response metrics based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1, clinical stage, lymph node (LN) metastasis status, and pathological downstaging compared with clinical stage. LN metastasis and pathologic response were determined via a histologic assessment. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease. B Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative survival rates of all patients (n = 45). C Kaplan–Meier curves for cumulative survival rates of pathological complete response (PCR) (n = 14) and non-PCR (n = 31) patients. Log-rank test was used and p = 0.219 (two sided).

Treatment-related AEs

Table 3 presents a summary of treatment-related adverse events (AEs) observed during neoadjuvant therapy. Overall, 85.4% (41 out of 48) of patients experienced AEs of any grade, whereas only 2 patients (4.2%) reported treatment-related AEs classified as Grade 3. The most frequently observed treatment-related AEs included anaemia (72.9%), decreased white blood cell count (47.9%), decreased neutrophil count (39.6%), nausea (37.5%), decreased appetite (25.0%), decreased platelet count (20.8%) and increased alanine aminotransferase (20.8%). The Grade 3 treatment-related AEs included one case each of anaemia and increased alanine aminotransferase. In this study, no immune-related AEs, including myositis, pneumonia, hypothyroidism, or pituitary dysfunction, were observed. No Grade 4 or 5 AEs were reported, and the AEs did not cause dose reductions or treatment discontinuation.

Immune landscape and cellular distribution characteristics

No significant differences were observed in the baseline demographic or clinical baseline data between the 10 patients in the PCR and non-PCR groups used for IMC (Supplementary Table 1). Automated cell segmentation of stained images using the DeepCell algorithm indicated that the non-PCR group presented a significantly greater cell density per unit area than the PCR group did (p = 0.032) (Fig. 3A–C). Both groups demonstrated substantial immune cell infiltration, which was predominantly localised in stromal regions (Fig. 3D, E, Fig. S2B, C). Despite the abundance of immune cells had no siginifcant difference between the two groups (Fig. S2D), the dense spatial distribution of immune cells was associated with elevated expression levels of immunosuppressive molecules in the non-PCR group when compared with PCR group, including HIF1A, CD163, and FoxP3 (Fig. 3F, G, Fig. S2E).

A,B Representative cell segmentation maps were generated using the DeepCell algorithm for both the pathological complete response (PCR) and non-PCR groups. C Comparative analysis of absolute cell counts per unit area between the non-PCR (n = 10) and PCR (n = 10) groups. A t test was used to and p = 0.032 (two sided). The whiskers indicate the range from minimum to maximum values, and the bounds of the boxes represent the 25 and 75th percentiles. The centres denote the medians. D,E Two of ten patients for tissue architecture and spatial distribution of major immune cell subsets in both the non-PCR and PCR groups. F,G One of ten patients for expression patterns of functional markers in both the non-PCR and PCR groups.

Multicellular composition and functional assessment

We used canonical immune markers to identify 25 distinct cell populations (Fig. 4A, Fig. S2A), which consisted of 13 nonimmune subsets (Fig. S3A) and 12 immune subsets (Fig. S3B). Proportional analysis indicated that regulatory T cells (Tregs) constituted the most abundant immune infiltrate in both groups. However, the non-PCR group was predominantly characterised by Ki67⁺ Tregs (Fig. 4B, C). Additionally, cellular infiltration frequency analysis revealed significantly greater prevalences of HIF1Ahi/Hsp90hi tumour cells, PDL1⁺Ki67⁺ tumour cells, FAP⁺ fibroblasts, Tregs, M2 macrophages, and MPO+ neutrophils in the non-PCR group than in the PCR group. In contrast, the numbers of αSMA⁺ fibroblasts, collagen I⁺ fibroblasts, and CD8⁺ Trm cells were significantly greater in the PCR group than in the non-PCR group (Fig. 4D).

A Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of imaging mass cytometry (IMC) segmentation single-cell clusters. EP epithelial cells, Endo endotheliocytes, SMC smooth muscle cells, FB fibroblasts, Trm cells tissue-resident memory T cells, Tregs regulatory T cells, and M2, M2 macrophages. B,C Scatter plots illustrating the proportions of cellular populations in the pathological complete response (PCR) (n = 10) and non-PCR (n = 10) groups. D Statistical analysis comparing the frequencies of cell populations between the non-PCR (n = 10) and PCR (n = 10) groups. A t test was used to and p value was two sided. Whiskers indicate the range from minimum to maximum values, and the bounds of the boxes represent the 25 and 75th percentiles. The centres denote the medians.

Cell‒cell interactions and spatial neighbourhood characteristics

Figure 5A presents a quantitative analysis of the cell‒cell interaction intensities, identifying four distinct interaction modules between the non-PCR and PCR groups. In BOX1, epithelial cells characterised by high expression levels of HIF1A and HSP90 in the non-PCR group presented strong positive correlations with other epithelial cells. BOX2 shows that MPO⁺CXCL10⁺ macrophages in non-PCR tumours engaged in robust interactions with tumour cells. BOX3 highlights a tightly interconnected network centred on CD44⁻FAP⁺ fibroblast subsets, demonstrating strong interactions with Ki67⁺ Tregs, Ki67- Tregs, M2 macrophages, and CD8⁺ TRMs in non-PCR patients. These interactions were attenuated or absent in PCR patients. BOX4 reveals that Tregs engaged in significant interactions with multiple immune cell populations, including neutrophils, B cells, and CD8⁺ TRMs and M2 macrophages. This type of cellular crosstalk, particularly through the Tregs–M2 macrophage axis, may sustain the immunosuppressive microenvironment in non-PCR patients.

A Heatmap of interaction strengths among cellular subpopulations using neighbourhood analysis with permutation testing. sum_sigval: Summed signal intensity of all ligand‒receptor interactions between sender‒receiver subpopulation pairs;Rows: Sender cell subpopulations/clusters;Columns: Receiver cell subpopulations/clusters. Colour scale: blue: negative sum_sigval values indicating spatial avoidance between subpopulations;deep red: positive sum_sigval values indicating enhanced interactions between subpopulations;white: no significant interaction or avoidance (values approaching zero). Intensity: Colour saturation corresponds to effect magnitude (deeper colours = stronger biological effects). B The spatial distribution of cellular neighbourhoods (CNs) alongside the corresponding regions stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). C Statistical analysis of the abundance of CNs in the pathological complete response (PCR) (n = 10) and non-PCR (n = 10) groups. A t test was used to and p value was two sided. Whiskers indicate the range from minimum to maximum values, and the bounds of the boxes represent the 25 and 75th percentiles. The centre lines denote the medians.

We performed cellular neighbourhood analysis to explore functional synergies among nearby cell populations in the tissue microenvironment. By analysing the 20 nearest neighbours of each cell, we identified the structural characteristics of 10 distinct cellular neighbourhoods (CNs) (Fig. S4A). Both groups exhibited significant infiltration of CD8⁺ T cells (CN9); however, the PCR group exhibited a diffuse pattern of CD8⁺ T cell infiltration, whereas the non-PCR group presented CD8⁺ T cells spatially confined by immunosuppressive cell aggregates surrounding tumour nests (Fig. 5B, Fig. S5). The immunosuppressive cellular neighbourhood CN6, centred on FAP⁺ fibroblasts as spatial organisers. This domain was coenriched Ki67⁺ Tregs, TCF1hiTregs, and PD-L1hiM2 macrophages (Fig. S4A), collectively forming a functional immunosuppressive hub. No significant difference in the quantity of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) (CN4) was detected between the PCR and non-PCR groups (Fig. 5C). Nevertheless, functional profiling indicated that TLSs in the non-PCR group presented elevated expression levels of immunosuppressive molecules, including FOXP3, HIF1A, CD38, PD1, and HSP90 (Fig. S4B).

Discussion

This single-arm, phase 2 study revealed that the combination of serplulimab with carboplatin and nab-paclitaxel is associated with promising antitumour efficacy, has manageable safety profiles and does not delay surgery in the treatment of locally advanced ESCC. Additionally, potential TME characteristics were identified in patients with varying responses to combined immunotherapy and chemotherapy regimens using IMC.

For patients with resectable ESCC, the primary challenge for surgeons lies in the implementation of effective neoadjuvant therapy to achieve pathological downstaging and facilitate radical resection of the tumour and lymph nodes during surgical intervention. Previous studies have investigated the effects of combining serplulimab with chemotherapy as a treatment for recurrent or advanced ESCC. The randomised, double-blind, phase 3 ASTURM-007 study demonstrated that the combination of serplulimab and chemotherapy significantly improved progression-free survival and overall survival rates beyond the levels that can be achieved when chemotherapy is used in isolation as a first-line treatment for patients with previously untreated advanced ESCC2. Therefore, for patients with locally advanced ESCC, the combination of neoadjuvant serplulimab and chemotherapy represents a potential treatment strategy.

Notably, the PCR rate observed with neoadjuvant therapy in this trial was 31.1% (95% CI, 18.2–46.6%), which was similar to previously reported rates of 28.0% for neoadjuvant camrelizumab and chemotherapy12, 41% for pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy17, and 43.9% for neoadjuvant camrelizumab combined with apatinib and chemotherapy18. Additionally, this PCR rate was comparable to that reported for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. For example, trials such as NEOCRTEC5010 trial19, JCOG1109 NExT trial7 and FFCD9901 trial20 reported PCR rates of 43.2%, 38.5% and 33.3%, respectively. In addition, a previous meta-analysis that examined 21 studies involving 1,233 patients with locally advanced ESCC who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy reported an overall PCR rate of 32% (95% CI, 26–39%)21. In terms of the short-term primary endpoint of this trial, our neoadjuvant therapy regimen showed modest antitumour efficacy for locally advanced ESCC.

Previous research has also suggested that a decrease in viable tumour cells following neoadjuvant therapy is associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with cancer22,23. Consistent with our study, the two-year survival rate in the PCR group was 100%. Although adjuvant therapy remains a critical determinant of long-term survival, the completion of adjuvant chemotherapy presents substantial challenges for patients who often experience compromised health following radical oesophagectomy, as described in the JCOG1109 NExT trial7. The CheckMate577 study demonstrated that a 12-month regimen of nivolumab is efficacious for patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and oesophagectomy. As an adjuvant treatment, nivolumab significantly enhanced disease-free survival (hazard ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.56–0.86, p < 0.001) while maintaining manageable toxicity and exerting minimal impact on health-related quality of life compared with placebo8. Consequently, its use is now recommended, as single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors, in contrast to cytotoxic chemotherapy, present an appealing option in the adjuvant setting24. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the primary objective was to investigate neoadjuvant treatment. Like other neoadjuvant immunotherapy12, adjuvant immunotherapy can be administered for one year to all patients without restrictions to improve patient survival outcomes. In the present study, the two-year overall survival rate was 88.3%, which is comparable with those previously reported in JCOG1109 NExT trial7 and NEOCRTEC5010 trial19, which reported two-year overall survival rates of approximately 80% for neoadjuvant triplet chemotherapy and 75.1% for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced oesophageal cancer. The present findings are consistent with our previous results, which demonstrated an 85.9% two-year survival rate for the combination of neoadjuvant camrelizumab, apatinib, and chemotherapy18. This finding is also in line with the 91% survival rate observed with neoadjuvant pembrolizumab in conjunction with chemotherapy17. Additionally, although 61.3% (19/31) of non-PCR patients presented with lymph node metastasis upon pathological assessment, the two-year survival rate in this group exceeded 80%. Long-term follow-up is necessary to confirm survival benefits for patients with pathological stages exceeding IIIA. Based on these findings, the present neoadjuvant therapy regimen exhibits promising antitumour activity for locally advanced ESCC, and longer follow-up is still needed to verify this possibility.

In terms of the safety profile, the neoadjuvant administration of serplulimab in conjunction with chemotherapy is consistent with prior research involving serplulimab combined with chemotherapy. All enroled patients successfully completed three cycles of neoadjuvant therapy without experiencing any treatment-related discontinuation. Most adverse events were classified as Grade 1 or 2, and only a small proportion of patients experienced Grade 3 adverse events. Similar results have been reported in other trials investigating the combination of PD-1 inhibitors with chemotherapy for the neoadjuvant treatment of locally advanced ESCC. The NIC-ESCC2019 study assessed the efficacy of neoadjuvant camrelizumab in conjunction with albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with locally advanced ESCC and reported an incidence of treatment-related Grade 3 AEs of 10.7%, with no occurrence of Grade 4 or higher AEs25. These results represent a lower incidence than the rates associated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or PD-1 inhibitors with chemoradiotherapy for Grade 3 and higher AEs, which are approximately 60%19,26. Overall, the safety profile for the combination of serplulimab with chemotherapy is manageable, and no novel safety concerns are associated with serplulimab.

Concerning surgical safety and complexity, neoadjuvant treatment did not increase the risk of surgical complications, nor did it compromise the achievement of R0 resection or the number of lymph nodes harvested. The incidence of anastomotic leakage and vocal cord paralysis was 4.4%, with no 90-day mortality or surgical delays observed during the trial. The rates of major complications and mortality in this trial were lower than those reported in previous studies on neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy20, which is consistent with the outcomes observed in minimally invasive oesophagectomy without neoadjuvant treatment27,28. Furthermore, the present study reported an R0 resection rate of 100% and a median of 33 resected lymph nodes. The R0 resection rate is crucial for oesophagectomy, as failure to achieve R0 resection can lead to early postoperative tumour recurrence and, consequently, a lower survival rate. The R0 resection rate observed in the present study was higher than the 60% reported for neoadjuvant chemotherapy29 and was comparable to the 92–98% range documented for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy19,30. The median number of harvested lymph nodes was 33, which was higher than that of patients receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by oesophagectomy; the median numbers of lymphadenectomies reported in the FFCD990120 and NEOCRTEC5010 trials19 were 16 and 20, respectively. These findings indicate that the integration of serplulimab with chemotherapy followed by minimally invasive oesophagectomy results in a favourable surgical quality profile.

The present study employed IMC to offer a multidimensional perspective on the mechanisms underlying immunity combined with chemotherapy resistance. Critically, although non-PCR tumours exhibited higher cellular density and immune infiltration, these cells were spatially constrained within immunosuppressive niches characterised by elevated expression levels of HIF1A, CD163, and FoxP3. These findings align with those of Wu et al.16, who identified S100A9⁺ macrophages in fibrotic regions as drivers of therapy resistance, emphasising that an immunosuppressive TME spatially orchestrates treatment failure. The Ki67⁺ Treg subset is characterised by increased proliferative activity and immunosuppressive capacity31. In addition, M2 macrophages pose a significant obstacle to maximising the clinical potential of immunotherapy32. Furthermore, the expression profiles of HIF1Ahi and Hsp90hi have been implicated in the maintenance of cancer stem cell characteristics and the facilitation of immune evasion via PD-L1 upregulation and T cell exhaustion33,34,35. Thus, the significant accumulation of Ki67⁺ Tregs, M2 macrophages, and HIF1Ahi/Hsp90hi epithelial cells suggested that the synergistic interplay between immunosuppressive factors and intrinsic tumour cell resistance mechanisms may critically contribute to immune and chemotherapy treatment failure.

At the cellular interactome level, FAP⁺ fibroblasts in non-PCR tumours serve as spatial organisers that colocalize with Ki67⁺ Tregs and M2 macrophages to form functional immunosuppressive hubs. Previous research has demonstrated that FAP⁺ cancer-associated fibroblasts recruit Tregs through the secretion of certain chemokines, such as CXCL12, and obstruct T cell infiltration by forming physical barriers36,37,38. These findings are consistent with those of the present study, which revealed the expansion of FAP⁺ fibroblast-enriched immunosuppressive cellular environments in patients who did not achieve PCR. The present interaction network analysis also revealed significant crosstalk among FAP⁺ fibroblasts, Ki67⁺ Tregs, and M2 macrophages, indicating their collaborative role in establishing an immune-privileged niche that restricts effector T cell function. Additionally, the spatial distribution patterns of CD8⁺ T cells differed markedly between the PCR and non-PCR groups, in which non-PCR tumours presented sequestered CD8⁺ T cells that were spatially segregated from tumour nests. This observation is in line with previous work showing that the spatial proximity between effector T cells and tumour cells is predictive of clinical outcomes and therapeutic efficacy39,40. Therefore, further investigation into the findings obtained from IMC could contribute to the optimisation of more reliable neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy treatment strategies for locally advanced ESCC.

The present study has several limitations. First, given the exploratory nature and limited duration of follow-up of the present study, in combination with its limited sample sizes and lack of a control group, potential selection bias could not be eliminated. Therefore, further longitudinal studies with large sample sizes are needed to decrease selection bias and assess the potential survival benefits associated with the present neoadjuvant therapy regimen for patients. Second, at the beginning of the experimental design, the expression level of PD-L1 in tumours was not considered. The expression level of PD-L1 can serve as an initial predictor of the immunotherapy response in patients with ESCC. However, low or even negative expression does not necessarily preclude the efficacy of immunotherapy. Post hoc analysis of the JUPITER-06 trial41 demonstrated that, despite low PD-L1 expression, the combination of PD-1 antibodies and chemotherapy was superior to chemotherapy alone in these patients. Third, the TME characteristics of patients with varying immune combined with chemotherapy responses were not thoroughly explored in the present study, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

In summary, for locally advanced ESCC, the neoadjuvant regimen of serplulimab in combination with chemotherapy has modest antitumour activity, manageable safety, and feasibility. A phase 3 randomised trial featuring continued follow-up is essential for a formal evaluation.

Methods

Patients

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (Approval No. 2022–1022); this approval is available in the supplementary information. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05659251) on December 13, 2022. We screened patients aged 18–75 years with histologically confirmed ESCC. Prior to enrolment, standard examinations included magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, enhanced computed tomography scans of the chest and abdomen, neck ultrasound, and single-photon emission computed tomography bone scans. Attending physicians in the thoracic and oncology departments were responsible for staging these patients and evaluating their resectability. The eligibility criteria were as follows: stage II-IVA ESCC as per the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual; provision of informed consent; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; and no prior history of anticancer treatment. Patients who exhibited distant metastasis; who were receiving antiviral therapy (i.e., chronic hepatitis B virus carriers who needed antiviral therapy) at the time of this study; who had a history of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or molecular targeted therapy; who had a history of other malignancies within the past five years; who had either active autoimmune diseases or immune deficiencies or a history of such issues; or who were intolerant to oesophagectomy were excluded from the study. Individuals of both sex who met the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were allowed to participate in the trial.

Study design and treatment

This prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial was initiated by an investigator and conducted at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. After the participants provided informed consent, all patients underwent three cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, with each cycle administered at 21-day intervals. The treatment regimens included intravenous administration of serplulimab at a dosage of 4.5 mg/kg on Day 1, albumin-bound paclitaxel at a dosage of 260 mg/m² on Day 1, and carboplatin with an area under the drug concentration–time curve of 5 on Day 1. Following the completion of the final cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, minimally invasive oesophagectomy (Ivor–Lewis or McKeown) was performed 4–6 weeks later. The resection should extend at least 5 cm from the tumour’s origin, as determined by pre-neoadjuvant endoscopy. The initial follow-up was conducted one month posttreatment, followed by subsequent assessments at three-month intervals for a duration of two years and, thereafter, at six-month intervals. Base on the final pathological assessment, the investigator and the participant could collaboratively determine the appropriate subsequent treatment. Patients were then eligible to receive serplulimab for a period of up to one year. For patients who achieved PCR, a single administration of serplulimab was recommended. In contrast, patients who did not achieve PCR were advised to undergo an additional cycle of chemotherapy along with continued immunotherapy. Furthermore, for patients with positive lymph nodes, radiotherapy was recommended.

End points and assessments

The principal end point of this study was PCR, which was evaluated within one month after the surgery by two independent senior pathologists and defined as the absence of residual viable tumours at both the primary tumour site and all harvested lymph nodes.

The secondary endpoints included the R0 resection rate, AEs, objective response rate, event-free survival time, disease-free survival time and overall survival time. The R0 resection rate refers to the absence of cancer cells at the margin of the incision according to the pathological results. AEs in all treated patients were assessed and classified by the investigators according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 5.0. Three weeks after the last neoadjuvant, enhanced thoracic computed tomography was performed, and the radiologist assessed the objective response rate according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1. The surgical outcomes, including the operative duration, postoperative hospital length of stay, incidence of major complications, and 90-day mortality rate, were recorded. In addition, the overall survival time was calculated from the date of enrolment to either the last follow-up on April 1, 2025, or the date of death from any cause. The event-free survival time was calculated from the date of enrolment to the time of the first date of disease recurrence or date of death due to any cause, whichever occurred first. Disease-free survival time was calculated from the date of surgery to the time of the first date of disease recurrence or date of death due to any cause, whichever occurred first.

IMC preprocessing and clustering

Patients who achieved PCR at both the primary tumour site and the lymph nodes were assigned to the PCR group, whereas the other patients were assigned to the non-PCR group. Haematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was performed to identify regions of interest with dense immune cell infiltration. After IMC staging, imaging was conducted using a Hyperion system (Fluidigm, USA) at 1 μm resolution. The raw data were segmented with DeepCell to extract spatial, morphological, and marker features. The IMC staining procedures, all the markers used in this study and data preprocessing are detailed in the supplementary methods.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation was performed with PASS version 21.0. Previous research has revealed a 9% (95% CI, 6–14%) PCR rate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with ESCC21. Thus, we hypothesised that the addition of serplulimab to chemotherapy may increase the PCR rate to 29%. At a significance level (α) of 0.025 (one-sided), a sample size of 45 participants was considered sufficient to achieve a statistical power of at least 94% to detect such a difference. To accommodate an anticipated dropout rate of 10% in this study, we planned to enrol a total of 50 participants.

Data analyses for clinical data were originally planned in the statistical analysis plane and were performed with the assistance of SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The data are expressed as medians (ranges), means (standard deviations) or proportions (percentages) where suitable. The PCR rate was summarised for the efficacy-evaluable population as the number of patients (percentage), and 95% CI was employed to estimate the potential range for the PCR. The 95% CI was calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method. To evaluate the cumulative survival rate, the Kaplan–Meier method was used, and the log-rank test was used to compare differences between the PCR and non-PCR groups.

The IMC analysis in this study was a post hoc analysis that was not included in the initial research design. The imcRtools package (version 1.14.0) was used to create a spatial experiment object, integrating segmentation results with raw images. The multichannel images, nuclear masks and cytoplasmic masks were imported into a CytoImageList using Cytomapper (version 1.20.0). Single-cell expression data were associated with spatial coordinates and image metadata. FastMNN was used to correct batch effects. PhenoGraph was used to identify the subpopulations, and the cluster markers were determined using Wilcoxon tests.

The test interaction function in the imcRtools package was used to calculate empirical p values by permuting the cell labels 1,000 times. Colocalization was categorised as follows: interaction, in which the observed counts exceeded the 95th percentile of the null distribution; avoidance, in which the observed counts were below the 5th percentile; and cross-sample aggregation, in which the significance scores (−1, 0, and +1) were summed across images and visualised as a heatmap. To construct the spatial graph, a k-nearest neighbour graph (k = 20, validated through spatial autocorrelation) was constructed based on cell centroids. In neighbourhood profiling, the aggregate neighbour function was used to compute phenotype composition vectors for the local neighbourhood of each cell. CN clustering was performed via k-means clustering (k = 8, determined by the elbow method) to partition cells into CNs, which were subsequently functionally annotated. Data analysis for IMC was performed with the assistance of R version 4.4.2. A t test was used to evaluate the differences in cell proportions and functional marker expression between the PCR and non-PCR groups, and statistical significance was defined by a two-tailed p value less than 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The IMC data reported in this paper are available at the figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30466160.v1). Other Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Arnold, M., Ferlay, J., van Berge Henegouwen, M. I. & Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of oesophageal and gastric cancer by histology and subsite in 2018. Gut 69, 1564–1571 (2021).

Song, Y. et al. First-line serplulimab or placebo plus chemotherapy in PD-L1-positive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 29, 473–482 (2023).

Uhlenhopp, D. J., Then, E. O., Sunkara, T. & Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer: update in global trends, etiology and risk factors. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 13, 1010–1021 (2020).

Pennathur, A., Gibson, M. K., Jobe, B. A. & Luketich, J. D. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 381, 400–412 (2013).

Obermannová, R. et al. Oesophageal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33, 992–1004 (2022).

Tang, H. et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by minimally invasive esophagectomy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective multicenter randomized clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 34, 163–172 (2023).

Kato, K. et al. Doublet chemotherapy, triplet chemotherapy, or doublet chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced oesophageal cancer (JCOG1109 NExT): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 404, 55–66 (2024).

Kelly, R. J. et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1191–1203 (2021).

Yin, J. et al. Neoadjuvant adebrelimab in locally advanced resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a phase 1b trial. Nat. Med. 29, 2068–2078 (2023).

Li, Q., Liu, T. & Ding, Z. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for resectable esophageal cancer: a review. Front. Immunol. 13, 1051841 (2022).

Song, X. et al. Spatial multi-omics revealed the impact of tumor ecosystem heterogeneity on immunotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with bispecific antibody. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e6234 (2023).

Qin, J. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without camrelizumab in resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the randomized phase 3 ESCORT-NEO/NCCES01 trial. Nat. Med. 30, 2549–2557 (2024).

Sun, J. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 398, 759–771 (2021).

Glasson, Y. et al. Single-cell high-dimensional imaging mass cytometry: one step beyond in oncology. Semin. Immunopathol. 45, 17–28 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Envafolimab plus lenvatinib and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective, single-arm, phase II study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 280 (2024).

Wu, C. et al. Spatial proteomic profiling elucidates immune determinants of neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 43, 2751–2767 (2024).

Shang, X. et al. A prospective study of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the Keystone-001 trial. Cancer Cell 42, 1747–1763 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Camrelizumab, chemotherapy and apatinib in the neoadjuvant treatment of resectable oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm phase 2 trial. Eclinicalmedicine 71, 102579 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (NEOCRTEC5010): a phase III multicenter, randomized, open-label clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2796–2803 (2018).

Mariette, C. et al. Surgery alone versus chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for stage I and II esophageal cancer: final analysis of randomized controlled phase III Trial FFCD 9901. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 2416–2422 (2014).

Gaber, C. E. et al. Pathologic complete response in patients with esophageal cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 13, e7076 (2024).

Pataer, A. et al. Histopathologic response criteria predict survival of patients with resected lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 7, 825–832 (2012).

Shen, J. et al. Pathological complete response after neoadjuvant treatment determines survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients (NEOCRTEC5010). Ann. Transl. Med. 9, 1516 (2021).

Yang, H., Wang, F., Hallemeier, C. L., Lerut, T. & Fu, J. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet 404, 1991–2005 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab plus chemotherapy for resectable, locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (NIC-ESCC2019): a multicenter, phase 2 study. Int. J. Cancer 151, 128–137 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Preoperative pembrolizumab combined with chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (PALACE-1). Eur. J. Cancer 144, 232–241 (2021).

Biere, S. S. et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 379, 1887–1892 (2012).

Luketich, J. D. et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 256, 95–103 (2012).

Group, M. R. C. O. Surgical resection with or without preoperative chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359, 1727–1733 (2002).

van Hagen, P. et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2074–2084 (2012).

Huang, S. et al. Systemic longitudinal immune profiling identifies proliferating Treg cells as predictors of immunotherapy benefit: biomarker analysis from the phase 3 CONTINUUM and DIPPER trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 285 (2024).

Luo, J. et al. ISCU-p53 axis orchestrates macrophage polarization to dictate immunotherapy response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 16, 462 (2025).

Filatova, A. et al. Acidosis Acts through HSP90 in a PHD/VHL-Independent Manner to Promote HIF Function and Stem Cell Maintenance in Glioma. Cancer Res 76, 5845–5856 (2016).

Pan, Y. et al. Cancer stem cells and niches: challenges in immunotherapy resistance. Mol. Cancer 24, 22–52 (2025).

Min, S. et al. Chetomin, a Hsp90/HIF1α pathway inhibitor, effectively targets lung cancer stem cells and non-stem cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 21, 698–708 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Identification of a tumour immune barrier in the HCC microenvironment that determines the efficacy of immunotherapy. J. Hepatol. 78, 770–782 (2023).

Varveri, A. et al. Immunological synapse formation between T regulatory cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes tumour development. Nat. Commun. 15, 4988 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Presence of onco-fetal neighborhoods in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with relapse and response to immunotherapy. Nat. Cancer 5, 167–186 (2024).

Galon, J. & Bruni, D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 197–218 (2019).

Galon, J. et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 313, 1960–1964 (2006).

Wu, H. et al. Clinical benefit of first-line programmed death-1 antibody plus chemotherapy in low programmed cell death ligand 1–expressing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a post hoc analysis of JUPITER-06 and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 1735–1746 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Province Key Technology R&D Programme (“Leading Goose” Research and Development Project of Zhejiang Province; No. 2023C03064 to Ming Wu) and the National Key R&D Programme of China (No. 2023YFF1204404 to Ming Wu). The authors would like to express their thanks to all the patients and their families. Serplulimab was supported by Henlius Biotech, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X.W., C.Q.W., Y.P.W., H.S., and M.W. contributed to the study design and protocol draughting. Z.X.W., C.Q.W., G.S., H.S., and M.W. contributed to patient recruitment. M.W. and S.H. supervised the study. Z.X.W., C.Q.W., Y.P.W., F.X.L., L.N.Q., K.L.W., and J.F.L. contributed to the data collection, analysis and interpretation. Z.X.W., C.Q.W., and H.S. contributed to the draughting of the manuscript. The manuscript was critically revised by all the authors, who also approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Edith Borcoman, Hong Yang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Z., Wu, C., Wang, Y. et al. Neoadjuvant serplulimab combined with chemotherapy for resectable oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Nat Commun 17, 871 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67589-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67589-5