Abstract

Although TDP-43 pathology is found in most sporadic and familial ALS and FTD cases, other shared pathogenic mechanisms remain largely unknown. Here we show that SIRT1 levels are decreased and acetylated p53 levels are increased in iPSC-derived neurons from sALS patients and with the FTD3-causing CHMP2B mutation. Ectopic expression of SIRT1 in these patient neurons rescues neurodegeneration and reduces acetylated p53 levels. DNA damage is elevated in both sALS and FTD3 neurons, leading to increased phosphorylation of p53 at Serine 15 and elevated levels of Ku80. Knockdown of either p53 or Ku80 rescues neurodegeneration and increases SIRT1 levels in these neurons. Moreover, ectopic expression of SIRT1 or genetic knockdown of either p53 or Ku80 suppresses retinal neurodegeneration caused by FTD3-associated mutant CHMP2B protein in an in vivo Drosophila model. These findings identify a dysregulated SIRT1–p53 feedback loop as a common pathogenic mechanism and promising therapeutic target in both sporadic and familial ALS/FTD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are progressive neurodegenerative diseases with distinct clinical features. FTD involves progressive atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes, leading to cognitive and behavioral impairments1,2,3,4, while ALS is primarily characterized by degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons5,6,7. Despite these clinical differences, many patients exhibit overlapping genetic, pathological, and molecular features8,9,10,11,12. Indeed, ALS and FTD are increasingly recognized as part of a clinicopathological continuum, sharing common genetic risk factors—such as mutations in C9ORF72, TARDBP, FUS, and CHMP2B—and convergent downstream mechanisms including RNA dysregulation, impaired autophagy, and cytoskeletal abnormalities9,10,13.

Although these pathogenic pathways have been primarily identified in familial cases, the majority of ALS (approximately 90%) and FTD (approximately 60%) patients lack known genetic mutations and are classified as sporadic11,12. The molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration in sporadic ALS and FTD remain largely unknown, and it is unclear whether the pathways discovered in familial forms also contribute to these sporadic cases. One key entry point is the fact that nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic aggregation of the DNA/RNA-binding protein TDP-43 are found in 97% of ALS cases and about half of FTD cases9. However, the pathogenic mechanisms that operate in ALS/FTD, both with and without TDP-43 pathology, are incompletely understood.

Among the genes implicated in both ALS and FTD, CHMP2B encodes a subunit of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport III (ESCRT-III), which plays a crucial role in multivesicular formation, cytokinesis, virus budding, nuclear membrane surveillance, and autophagy14. In patients with a rare familial form of FTD linked to chromosome 3 (FTD3), a single-nucleotide mutation in CHMP2B (G26403C) leads to abnormal pre-mRNA splicing and the generation of two mutant mRNA isoforms15. CHMP2BΔ10 arises from the skipping of the first 10 nucleotides of exon 6, resulting in a frameshift and an elongated C-terminal sequence. CHMP2BIntron5 (CHMP2BIn5) is produced by the retention of intron 5, introducing a premature stop codon and yielding a truncated protein. Although FTD3 caused by mutant CHMP2B is not associated with TDP-43 pathology16, previous works from us and others have shown that CHMP2BIn5 disrupts the autophagy pathway17,18,19,20,21. Moreover, CHMP2BIn5 expression in Drosophila neurons causes synaptic overgrowth at the neuromuscular junction22, and in mouse brain excitatory neurons it leads to social behavioral deficits23. However, the neurotoxic consequences of CHMP2BIn5 in human neurons remain poorly defined.

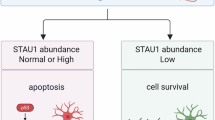

In this study, we used human iPSC-derived cortical neurons containing the FTD3-causing CHMP2B G26403C mutation and motor neurons from four patients with sporadic ALS (sALS) to reveal common pathogenic mechanisms in these diseases. We found that the SIRT1-p53 signaling axis was dysregulated in these human neurons. SIRT1, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, plays a pivotal role in neuronal survival by maintaining genomic stability and regulating stress responses24,25,26,27,28. One of its critical targets is p53, which SIRT1 deacetylates at lysine 382 (K382), thereby suppressing its transcriptional activity and pro-apoptotic effects29,30,31,32. We show that SIRT1 expression is reduced, while both p53 and Ku80 are dysregulated in sALS and FTD3 neurons—characterized by increased p53 acetylation and Ku80 accumulation—leading to enhanced apoptosis. Importantly, restoring SIRT1 levels or suppressing p53 or Ku80 expression significantly alleviated neurodegenerative phenotypes in both sALS and FTD3 neurons, which is further confirmed in vivo using a Drosophila model of FTD3. Together, our findings here identify the SIRT1-p53 feedback loop as another pathogenic pathway disrupted in both familial and sporadic ALS and FTD. Targeting this pathway may offer a unified therapeutic strategy for these currently untreatable neurodegenerative diseases.

Results

iPSC-derived cortical neurons with the FTD3-causing CHMP2B mutation exhibit neurodegenerative phenotypes, accompanied by decreased SIRT1 levels and increased acetylated p53

To model FTD3 in human neurons, we obtained an isogenic pair of iPSC lines generated via CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing33, in which the FTD3-causing CHMP2B G26403C mutation was engineered into a healthy control iPSC line using the CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Although the pathogenicity of the CHMP2B G26403C mutation is 100% penetrant15, we sought to strengthen our conclusions by generating an additional isogenic iPSC pair (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). To this end, we introduced the CHMP2B G26403C mutation into a healthy human iPSC line, employing a single-stranded oligonucleotide (ssODN) as a homology-directed repair template (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Sanger sequencing of targeted clones confirmed successful heterozygous editing at nucleotide position 26403 (G > C) (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

We next differentiated these genome-edited iPSC lines from two subjects into cortical neurons and assessed the expression of CHMP2B variants (Fig. 1a). For the sake of simplicity, we refer to these as FTD3 cortical neurons in this study. qPCR analysis revealed that mRNA levels of CHMP2BΔ10 and CHMP2BIn5 were substantially lower than those of wild-type CHMP2B, and were comparable between neurons differentiated from the iPSC lines of both subjects (Supplementary Fig. 1d), consistent with the notion that nonsense-mediated decay results in lower levels of mutant CHMP2B mRNAs. Western blot analysis revealed the absence of full-length CHMP2B protein in FTD3 cortical neurons with the homozygous G > C mutation (Supplementary Fig. 1e), further confirming the presence of the mutation.

a Schematic of the experimental timeline of cortical neuron differentiation from iPSCs. b Time-course analysis of neuronal viability using the LDH release assay revealed a progressive increase in neurodegeneration in FTD3 cortical neurons. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from n = 3 biologically independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (c) and quantification (d) of cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) levels in 3-month-old iPSC-derived FTD3 neurons after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. CC3 levels were quantified from biologically independent differentiation experiments (Subject 1: n = 4; Subject 2: n = 5) and are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (e) and quantification of SIRT1 (f), acetylated p53 (Ac-p53, Lys382) (g), total p53 (h) protein levels in 2-month-old iPSC-derived FTD3 neurons. Data were quantified from biologically independent differentiation experiments (Subject 1: n = 3; Subject 2: n = 5) and are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Significance levels were defined as *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001; ns: not significant. The exact p values and all source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To examine whether FTD3 cortical neurons exhibit neurodegenerative phenotypes in 2-month-old cultures, we performed a cytotoxicity assay following growth factor withdrawal, measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release over time. As expected, time-course analysis revealed a time-dependent decline in the viability of FTD3 cortical neurons compared to control neurons (Fig. 1b). No differences were observed between heterozygous and homozygous mutant neurons, indicating that the heterozygous CHMP2B G26403C mutation alone is sufficient to drive neurodegeneration in this iPSC-based model of FTD, consistent with the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of CHMP2B-related FTD15. Moreover, we assessed the expression of cleaved caspase-3 (CC3), a hallmark of apoptosis. Western blot analysis revealed a significant increase in CC3 expression in FTD3 cortical neurons relative to control neurons 7 days after growth factor withdrawal (Fig. 1c, d), further supporting the conclusion that the CHMP2B mutation promotes neuronal cell death in human neurons.

To identify molecular pathways mediating CHMP2B-induced neurodegeneration, we re-examined results from our previous CHMP2B immunoprecipitation (IP) from HEK293 cells followed by mass spectrometry34, and noticed that SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase involved in neuronal stress responses, was one of the CHMP2B-interacting proteins (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We confirmed the endogenous interaction between CHMP2B and SIRT1 in iPSC-derived neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and further validated that tagged CHMP2B variants (WT and In5) interact with endogenous SIRT1 under various IP conditions in HEK293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). Interestingly, iPSC-derived FTD3 cortical neurons with either heterozygous or homozygous CHMP2B G26403C mutations exhibited a significant reduction in SIRT1 protein levels (~40%) compared to control neurons (Fig. 1e, f). Notably, this decrease in SIRT1 coincided with a marked increase in acetylated p53 at lysine 382, with only modest changes in total p53 levels (Fig. 1e, g, h), indicating a dysregulated SIRT1-p53 axis in FTD3 cortical neurons.

SIRT1 overexpression rescues neurodegeneration in iPSC-derived FTD3 cortical neurons and Drosophila models

The observed reduction in SIRT1 levels, accompanied by elevated p53 acetylation and increased apoptotic markers in FTD3 cortical neurons (Fig. 1), suggests that dysregulation of the SIRT1–p53 signaling axis may directly contribute to neurodegeneration. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether restoring SIRT1 expression could mitigate these pathogenic effects. We therefore overexpressed SIRT1 via lentiviral transduction in FTD3 cortical neurons. Interestingly, SIRT1 overexpression significantly improved neuronal viability over time in FTD3 cortical neurons (Fig. 2a), and also led to a modest increase in viability in control neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3a). SIRT1 overexpression via lentiviral transduction in control neurons was verified by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). Mechanistically, consistent with its role as a deacetylase, SIRT1 overexpression led to a marked reduction in acetylated p53 (Lys382) levels without altering total p53 levels (Fig. 2b–d), indicating that SIRT1 reverses the pathogenic p53 acetylation observed in FTD3 cortical neurons. Since acetylated p53 is a pro-apoptotic form, this reduction suggests that SIRT1 protects against neuronal degeneration by inhibiting p53-driven apoptotic signaling. Indeed, CC3 levels were also significantly reduced in SIRT1-overexpressing FTD3 cortical neurons (Fig. 2b, e), further supporting the notion that the beneficial effects of SIRT1 are mediated by p53. Western blot analysis confirmed that lentiviral transduction resulted in more than a threefold increase in SIRT1 protein levels relative to neurons transduced with a control vector (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3d).

a Time-course analysis of neuronal viability using the LDH release assay in iPSC-derived neurons carrying the heterozygous FTD3-causing CHMP2B G26403C mutation, transduced with control vector (red) or SIRT1 overexpression constructs (SIRT1 OE-1 (lime) and OE-2 (fern)). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from six biologically independent samples per group, generated from three independent differentiations of iPSCs derived from two subjects (CHMP2B+/−, Subject 1 and CHMP2B+/–, Subject 2). Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (b) and quantification of acetylated p53 (Ac-p53, Lys382) (c), total p53 (d), and CC3 (e) protein levels in 2-month-old FTD3 cortical neurons after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. SIRT1 overexpression was achieved using two different lentiviral overexpression (OE) constructs (SIRT1 OE-1 (lime) and OE-2 (fern)), compared to neurons transduced with a control vector (red for FTD3, black for control). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from four biologically independent Western blot samples per group, obtained by differentiating neurons twice independently from isogenic iPSCs of two subjects. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (f) and quantification of Sirt1 protein levels (g) in CHMP2BIn5-expressing flies under the GMR-Gal4 driver. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed Student’s t test. Representative images (h) and quantification of retinal degeneration (i) in Drosophila eyes expressing CHMP2BIn5, with or without Sirt1 overexpression. The total number of flies of each genotype is shown in each column. Statistical significance was assessed by chi-square test. Significance levels were defined as *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns not significant. The exact p values and all source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To validate these findings in an in vivo model, we examined the effect of CHMP2BIn5 expression in Drosophila. CHMP2BIn5 expression under the GMR-Gal4 driver led to a strong reduction in Sirt1 protein levels in the fly eye (Fig. 2f, g), further supporting the idea that mutant CHMP2B downregulates SIRT1 signaling. Importantly, overexpression of Sirt1 in this model significantly rescued the CHMP2BIn5-induced retinal degeneration, as shown by the improved external eye morphology (Fig. 2h, i), with a significant reduction in the proportion of flies showing severe phenotypes. The extent of Sirt1 overexpression in flies was verified by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Together, these findings suggest that restoring SIRT1 expression mitigates neurodegeneration in FTD3 cortical neurons by reducing acetylated p53 and CC3 levels, and that this protective mechanism is conserved in vivo in a Drosophila model of FTD3.

sALS iPSC-derived motor neurons also show decreased SIRT1 levels, and its overexpression rescues neurodegeneration in these neurons

While CHMP2B mutations are rare, the SIRT1–p53 axis may be relevant to other forms of ALS and FTD. To investigate this, we assessed iPSC-derived motor neurons (iMNs) from four sALS patients and four control subjects published previously35. 3-month-old sALS iMNs showed a significant reduction in neuronal viability over time after growth factor withdrawal (Fig. 3a), paralleling the phenotype observed in FTD3 cortical neurons (Fig. 1b). Consistent with this, Western blotting revealed reduced SIRT1 expression and elevated acetylated p53 and CC3 levels in sALS iMNs compared to controls (Fig. 3b–e). These results suggest that SIRT1 downregulation and p53 hyperacetylation may represent a shared molecular mechanism driving neurodegeneration in both sporadic and familial ALS and FTD.

a Time-course analysis of neuronal viability by LDH release assay. Neuronal viability was measured over a 25-day period using LDH release assay in control and sALS iPSC-derived motor neurons (iMNs). Each group consisted of four iPSC lines, and each line underwent three biologically independent differentiation experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. Statistical comparison between the two groups was performed using a paired two-tailed t test. Western blot analysis (b) and quantification of SIRT1 (c), acetylated p53 (d), and CC3 (e) protein levels in 3-month-old sALS iMNs after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from four biologically independent differentiation experiments per iPSC line, using four control and four sALS iPSC lines (iMNs-1/2/3/4). Statistical comparisons between the two groups (control in black, sALS in red) were performed using an unpaired two-tailed t test (n = 4 lines per group). f Time-course analysis of neuronal viability assessed by LDH release assay in sALS iMNs. Neurons were differentiated from three biologically independent experiments using three distinct sALS iPSC lines and transduced with control vector, SIRT1 OE-1, or SIRT1 OE-2 (red, lime, fern, respectively). Each line represents the group mean (n = 3 per group), and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Western blot (g) analysis and quantification of SIRT1 (h) and CC3 (i) protein levels in 3-month-old sALS iMNs following neurotrophic factor withdrawal. SIRT1 was overexpressed using two lentiviral constructs (SIRT1 OE-1: lime; SIRT1 OE-2: fern) and compared to control vector (red). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three biologically independent experiments using three distinct sALS iPSC lines (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Significance levels were defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns not significant. The exact p values and all source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next examined whether SIRT1 overexpression could mitigate these pathogenic effects in sALS iMNs. To test this, we overexpressed SIRT1 using lentiviral transduction. This significantly improved the viability of sALS iMNs, as assessed by LDH release assay over 25 days (Fig. 3f). Western blot analysis confirmed that, while p53 levels remained unchanged, SIRT1 overexpression reduced CC3 levels in iMNs of all three sALS patients (Fig. 3g–i and Supplementary Fig. 4a), consistent with the improved viability.

sALS iMNs show an increased DNA damage response and p53 knockdown rescues neurodegeneration in these neurons

To examine what molecular pathways are responsible for the elevated neurodegeneration seen in sALS iMNs, we found that total p53 protein levels were significantly increased in these patient neurons compared to controls (Fig. 4a, b), consistent with observed total p53 increase in FTD3 cortical neurons (Fig. 1e, h). More importantly, we found that levels of phosphorylated p53 at Ser15—which occurs specifically in response to DNA damage36,37—were also significantly increased in sALS iMNs (Fig. 4a, c), indicating elevated DNA damage. Indeed, levels of γH2AX (Fig. 4a, d), a well-established marker of DNA damage, and Ku80 (Fig. 4a, e), the first protein that binds to double-strand DNA breaks and initiates DNA damage repair36,37, as well as phosphorylated ATM (p-ATM; Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), were also significantly upregulated in sALS patient neurons.

Western blot analysis (a) and quantification of total p53 (b), phosphorylated p53 (p-p53) (c), phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) (d), and Ku80 (e) protein levels in 3-month-old sALS iMNs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from four biologically independent differentiation experiments per iPSC line, using four control and four sALS iPSC lines (iMNs-1/2/3/4). Statistical comparisons between the two groups (control in black, sALS in red) were performed using an unpaired two-tailed t test (n = 4 lines per group). f Time-course analysis of neuronal viability using LDH release assay in sALS iMNs. Neurons were differentiated from three biologically independent experiments using three distinct sALS iPSC lines and transduced with control shRNA, p53 shRNA-1, or p53 shRNA-2 (red, magenta, grape, respectively). Each line represents the group mean (n = 3 per group), and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Immunoblot (g) analysis and quantification of CC3 (h) and SIRT1 (i) protein levels in 3-month-old sALS iMNs after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. p53 knockdown was performed using two independent shRNAs (p53 shRNA-1: magenta; p53 shRNA-2: grape) and compared to control shRNA (red). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three biologically independent experiments using three distinct sALS iPSC lines (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Significance levels were defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns: not significant. The exact p values and all source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine whether elevated p53 activity directly contributes to neurotoxicity in sALS neurons, we knocked down p53 using two different shRNAs and monitored neuronal viability using the LDH release assay. p53 knockdown significantly enhanced viability of sALS iMNs over time compared to neurons treated with control shRNA (Fig. 4f), supporting a neurotoxic role for p53 overactivation in these neurons. Western blot analysis confirmed that p53 knockdown led to a marked reduction in total p53 protein levels (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 5c). Notably, knockdown of p53 also decreased CC3 levels without altering Ku80 expression (Fig. 4g, h and Supplementary Fig. 5d), consistent with the improved neuronal viability observed. These findings indicate that p53 contributes to neurodegeneration in sALS patient neurons through apoptotic signaling, downstream of activated Ku80.

FTD3 cortical neurons also show increased DNA damage and p53 knockdown rescues neurodegeneration in these neurons

Similar to sALS iMNs, FTD3 cortical neurons displayed significantly increased levels of Ku80 and Ku70 compared to control neurons (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), indicating activation of the DNA damage repair pathway. In parallel, levels of phosphorylated p53 at Ser15 (Fig. 5a, b), γH2AX (Fig. 5a, c) and p-ATM (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d) were also elevated in FTD3 cortical neurons, paralleling the DNA damage response observed in sALS patient motor neurons.

Western blot analysis (a) and quantification of p-p53 (b) and γH2AX (c) proteins in 3-month-old iPSC-derived cortical neurons. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 5 biologically independent differentiation experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Representative comet assay images (d) and quantification of relative tail length (e) in iPSC-derived 3-month-old neurons. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from the following numbers of randomly selected comets: Control (Subject 1): n = 53; CHMP2B+/– (Subject 1): n = 55; Control (Subject 2): n = 64; CHMP2B+/– (Subject 2): n = 62; CHMP2B–/– (Subject 2): n = 53. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. f Time-course analysis of neuronal viability using the LDH release assay in iPSC-derived neurons carrying the heterozygous FTD3-causing CHMP2B G26403C mutation, transduced with control shRNA (red), p53 shRNA-1 (magenta), or p53 shRNA-2 (grape). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6 biologically independent samples per group, generated from three independent differentiations of iPSCs derived from two subjects. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (g) and quantification of CC3 (h) and SIRT1 (i) protein levels in 2-month-old cortical neurons after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 4 biologically independent Western blot samples per group, obtained from two independent differentiations of isogenic iPSCs derived from two subjects. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. j Quantification of p53 mRNA levels in the head of CHMP2BIn5-expressing flies. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 5 biologically independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed Student’s t test. Representative images (k) and quantification (l) of retinal degeneration in Drosophila eyes expressing CHMP2BIn5 with control RNAi (against the mCherry gene) or p53 RNAi. The total number of flies of each genotype is indicated in each column. Statistical significance was assessed by chi-square test. Significance levels were defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns not significant. The exact p values and all source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To directly assess genomic instability in FTD3 neurons, we also performed a DNA comet assay, a sensitive method to detect DNA strand breaks at the single-cell level. FTD3 neurons exhibited significantly longer comet tail lengths, increased percentage of DNA in the tail, and elevated Olive tail moments compared to control neurons (Fig. 5d, e, and Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). The Olive tail moment—defined as the product of tail length and the fraction of DNA in the tail36,38,39—is widely used as a quantitative metric of DNA damage. These data confirm that genomic integrity is severely compromised in FTD3 neurons, which coincides with increased levels of phosphorylated p53 and γH2AX observed in these neurons.

To determine whether p53 overactivation also contributes to neurodegeneration in FTD3, we performed LDH release assays. p53 knockdown significantly enhanced neuronal viability in FTD3 cortical neurons over time (Fig. 5f), while control neurons showed minimal changes (Supplementary Fig. 7a), indicating that p53 hyperactivation indeed contributes to mutant CHMP2B-induced toxicity. Immunoblotting further validated the efficient p53 knockdown by shRNAs in control neurons (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). In FTD3 neurons, p53 knockdown led to a robust reduction in total p53 and acetylated p53 protein levels (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 7d, e), accompanied by a significant decrease in CC3 levels (Fig. 5g, h), consistent with improved neuronal viability. Notably, SIRT1 expression was significantly restored to control levels following p53 knockdown (Fig. 5g, i), similar to the increase observed in sALS neurons (Fig. 4g, i). These findings support the existence of a conserved negative feedback loop between SIRT1 and p53 in sALS and FTD3 neurons, in which p53 hyperactivation suppresses SIRT1, and SIRT1 activation reduces acetylated p53 and CC3 levels.

To corroborate these results in vivo, we examined a Drosophila model expressing CHMP2BIn5 in the eye. Consistent with findings in human neurons (Figs. 1e, h and 4a, b), CHMP2BIn5 expression elevated p53 mRNA levels in fly heads (Fig. 5j). Importantly, p53 knockdown using multiple independent RNAi lines significantly rescued photoreceptor degeneration in CHMP2BIn5-expressing flies (Fig. 5k, l), indicating that suppression of p53 activity is also neuroprotective in vivo. Moreover, p53 expression greatly enhanced CHMP2BIn5 toxicity in the Drosophila eye (Supplementary Fig. 7f, g). Together, these data strongly support a model in which overactivation of p53—regulated through a SIRT1–p53 feedback loop—drives neurodegeneration in both sporadic and familial ALS and FTD.

Ku80 knockdown suppresses neurodegeneration in iPSC-derived sALS and FTD3 neurons

Finally, we tested whether overactivated Ku80 represents another potential therapeutic target for sALS cases. To this end, we knocked down Ku80 using two different shRNAs in three sALS patients iPSC-derived neurons and assessed neuronal viability. Ku80 knockdown significantly improved neuronal viability over time compared to control shRNA-treated neurons (Fig. 6a), suggesting that Ku80 overactivation contributes to neurodegeneration in sALS. Western blot analysis confirmed that Ku80 shRNA treatment in sALS iMNs effectively reduced Ku80 protein levels compared to neurons treated with control shRNA (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 8a). Notably, Ku80 knockdown also led to a marked decrease in total p53 protein levels (Fig. 6b, c), accompanied by significant restoration of SIRT1 expression (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 8b), indicating that the SIRT1-p53 feedback loop acts downstream of Ku80, consistent with the finding that SIRT1 overexpression did not affect Ku80 level (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Furthermore, Ku80 knockdown significantly reduced CC3 levels (Fig. 6b, d), correlating with the improved neuronal viability, but without affecting the extent of DNA damage, as evidenced by same levels of γH2AX (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d), indicating that the beneficial effects of Ku80 knockdown in sALS patient neurons are downstream of DNA damage.

a Time-course analysis of neuronal viability using LDH release assay in sALS iMNs. Neurons were differentiated from three distinct sALS iPSC lines and transduced with control shRNA (red), Ku80 shRNA-1 (aqua), or Ku80 shRNA-2 (blueberry). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent differentiations. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Immunoblot (b) analysis and quantification of total p53 (c) and CC3 (d) protein levels in 3-month-old sALS iMNs after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent differentiation experiments, each data point is the average of 3 iPSC lines. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. e Time-course analysis of neuronal viability using LDH release assay in iPSC-derived neurons carrying the heterozygous FTD3-causing CHMP2B G26403C mutation, transduced with control shRNA (red), Ku80 shRNA-1 (aqua), or Ku80 shRNA-2 (blueberry). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6 samples per group, generated from three independent differentiations of iPSCs derived from two subjects. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (f) and quantification of CC3 (g) and total p53 (h), and SIRT1 (i) protein levels in 2-month-old FTD3 cortical neurons after neurotrophic factor withdrawal. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from four biologically independent Western blot samples per group, obtained from two independent differentiations of isogenic iPSCs derived from two subjects. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Western blot analysis (j) and quantification (k) of Ku80 protein levels in heads of 10-day-old flies expressing CHMP2BIn5 under the control of the GMR-Gal4 driver. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7). Statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed Student’s t test. Representative images (l) and quantification (m) of retinal degeneration in CHMP2BIn5-expressing flies co-expressing control RNAi (against the mCherry gene) or Ku80 RNAi lines. The total number of flies per genotype is indicated in each column. Statistical significance was assessed by chi-square test. Significance levels were defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns not significant. The exact p values and all source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Consistent with the results in sALS neurons, Ku80 knockdown in iPSC-derived FTD3 neurons significantly improved neuronal viability compared to control shRNA (Fig. 6e). By contrast, control neurons were largely unaffected upon Ku80 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 9a), indicating that the effect is specific to disease context. Western blot confirmed the efficiency of Ku80 knockdown by shRNAs in control neurons (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). In FTD3 neurons, Ku80 knockdown led to reduced CC3 levels, total p53 and phosphorylated p53 (Fig. 6f–h, and Supplementary Fig. 9d, e), and notably restored SIRT1 expression (Fig. 6f, i). Moreover, Ku80 knockdown did not affect the extent of DNA damage, as evidenced by same levels of γH2AX (Supplementary Fig. 9f, g). These results suggest that Ku80 functions downstream of DNA damage but upstream of the SIRT1-p53 axis and contributes to neurodegeneration in FTD3 neurons.

To determine whether mutant CHMP2BIn5 similarly triggers Ku80-dependent DNA damage in vivo, we analyzed Ku80 expression in Drosophila models. Western blot analysis of fly heads expressing CHMP2BIn5 under the GMR-Gal4 driver revealed a marked increase in Ku80 protein levels (Fig. 6j, k). Although total H2Av levels remained unchanged, phosphorylated H2Av (γH2Av)—the Drosophila homolog of γH2AX40—was significantly elevated (Fig. 6j and Supplementary Fig. 10a, b), indicating increased DNA damage. To assess the functional role of Ku80 in CHMP2B-induced neurodegeneration in vivo, we performed genetic knockdown using four independent Ku80 RNAi lines. Knockdown efficiency was validated by Western blot (Supplementary Fig. 10c). Ku80 knockdown significantly rescued retinal degeneration in CHMP2BIn5-expressing flies (Fig. 6l, m), suggesting that Ku80 overactivation and the subsequent DNA damage signaling cascade contribute directly to neurotoxicity.

Discussion

Using iPSC-derived neurons under growth factor deprivation and a Drosophila model, we show that increased DNA damage occurs in both sALS and FTD3 caused by a CHMP2B mutation, further highlighting DNA damage as a key common pathogenic mechanism in different forms of ALS and FTD. It is worth noting that TDP-43 pathology is found in 97% of ALS cases and approximately 50% of FTD cases9. Loss of nuclear TDP-43 or disease-associated mutant TDP-43 results in increased DNA damage41,42,43,44,45. Thus, TDP-43 represents a convergence point and shared pathogenic mechanism in both sporadic and familial ALS and FTD with increased DNA damage46. Interestingly, FTD3 caused by mutant CHMP2B is not associated with TDP-43 pathology16. Thus, our findings here indicate that increased DNA damage occurs more commonly than previously thought in ALS/FTD, both with and without TDP-43 pathology.

In this study, we also highlight dysregulation of the SIRT1–p53 signaling axis as a shared mechanism in both motor neurons derived from sALS patients and cortical neurons carrying the FTD3-causing CHMP2B G26403C mutation. Among these molecular players, SIRT1 warrants particular attention. A growing body of evidence highlights its involvement in chromatin remodeling, DNA repair, and neuroprotection24,25,27,47,48. However, its functional relevance in ALS/FTD pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Our findings demonstrate that SIRT1 levels are decreased in neurons from both sALS and familial FTD (fFTD) under stress conditions, contributing to elevated levels of acetylated p53 and cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) activation, ultimately leading to neuronal death. Notably, SIRT1 overexpression was sufficient to restore neuronal viability, reduce p53 acetylation, and suppress neurodegeneration in these neurons, underscoring its therapeutic potential in both sporadic and familial forms of ALS and FTD.

The role of p53 as a central regulator of neurodegeneration in C9ORF72-ALS/FTD has been previously reported by us and others36,37,49,50,51. Our results significantly extend this notion by demonstrating that neurons from both sALS and FTD3 cases exhibit increased p53 activity, as evidenced by elevated levels of acetylated p53 and CC3. Importantly, both markers were reversed by p53 knockdown. However, given p53’s broad and important roles in regulating diverse cellular processes, direct inhibition of p53 may present challenges for therapeutic development52,53. In contrast, Ku80 is a protein dedicated to binding to double strand DNA break ends, thus it may serve as a feasible therapeutic target for sporadic and familial ALS and FTD. Increased expression of a DNA repair pathway gene, such as Ku80, in diseased neurons leads to the overactivation of downstream pathways, such as p53 and CC3-mediated cell death pathway. Partial downregulation of Ku80 does not comprise the DNA repair pathway and attenuates the overactivation of the p53-mediated cell death pathway, resulting in partial rescue of neurodegeneration.

While our study highlights the dysregulated SIRT1–p53 signaling axis and overactivated Ku80 as common downstream mechanisms, the upstream causes of these molecular events in sporadic and familial ALS and FTD appear to be heterogeneous. For example, in C9ORF72-ALS/FTD, toxic dipeptide repeat (DPR) proteins such as poly(GR) impair mitochondrial function and increase oxidative stress, thereby inducing DNA damage49,50. Likewise, TDP-43 pathology disrupts DNA repair by impairing the recruitment of NHEJ factors, including Ku70/80, as well as ATM and H2AX activation42,51. In sporadic ALS, factors that likely contribute to DNA damage in the nervous system include environmental insults such as traumatic brain injury54 and aging-associated genomic instability such as telomere shortening55,56, retrotransposon activation57,58, and somatic mutations59. How these diverse upstream events converge on common neurodegenerative signaling pathways remains an important topic for future investigation. Nonetheless, identifying and targeting such common downstream pathways could offer effective therapeutic strategies for treating the majority of ALS and FTD cases.

Methods

This study complies with all relevant ethical regulations as approved by the UMass Chan Medical School Institutional Biosafety Committee (Protocol I-435-25).

Generation of the CHMP2B Danish mutation in control iPSCs

The Danish CHMP2B mutation (genomic variant c.26403 G > C) was introduced into an iPSC line from a healthy male individual60 using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing with a single-strand donor oligonucleotide (ssODN) as a template. Sex is not considered a variable here because isogenic lines were used as controls. The 182-bp ssODN contained the g.26403 G > C mutation and two silent mutations to prevent recutting by CRISPR-Cas9 and to introduce a PvuII restriction site for screening. A plasmid expressing both the sgRNA (5’-GGTAAGCTTCGAGCAGCTGATGG-3’) and enhanced specificity Cas9 (pCAG-eCas9-GFP-U6-gRNA, Addgene #79145) was used. Two million iPSCs were nucleofected with 1 μg of the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and 4 μl of the ssODN using a 4D-Nucleofector (Amaxa, program CA137). Forty-eight hours later, GFP-positive cells were sorted by FACS and plated at a density of 15,000–50,000 cells per 10-cm dish in post-FACS recovery medium containing ROCK inhibitor. Single-cell derived colonies were picked and expanded for genotyping. Genomic DNA was isolated from each iPSC clone, and a 444-bp region flanking the edited locus was amplified by PCR using specific primers (5’-ACGAAGAAGAAAGCCAGGAT-3’; 5’-TCTGCACTGTGCTTGGTTTA-3’). PCR products were digested with PvuII and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Positive clones were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

For the second set of isogenic lines, we obtained three lines from Kristine K. Freude at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark: healthy iPSCs, heterozygous CHMP2B+/G26403C iPSCs, and homozygous CHMP2BG26403C/G26403C iPSCs. These mutant lines were generated from healthy iPSCs of a male individual using CRISPR-Cas9 in combination with a single-strand donor oligonucleotide (ssODN)33.

Cortical neuron differentiation

Human iPSCs were differentiated into cortical neurons using a modified protocol19. iPSCs were expanded in Matrigel-coated wells (Corning, 354230) and passaged with Accutase (EMD Millipore, SCR005) at 60% confluency. The next day, the culture medium was replaced with neuroepithelial progenitor (NEP) medium, and differentiation was induced over multiple stages, including NEP induction, neural progenitor expansion, and neuron maturation. Differentiated neurons were plated on Matrigel-coated plates, and then maintained for 1–3 months.

Motor neuron differentiation

Control iPSC lines (ND03231, ND03719, ND05280, ND00184 from two male and two female subjects) and sporadic ALS (sALS) patient-derived iPSC lines (ND09292, ND10739, ND13454, ND11813 from four male patients) were obtained from Dr. Justin K. Ichida (University of Southern California)35. Sex is not a variable for molecular and cellular phenotypes examined in the current study. Human iPSCs were differentiated into motor neurons following a modified protocol61. Briefly, iPSCs were expanded in Matrigel-coated wells (Corning) and passaged with Accutase (Millipore, SCR005) at 60% confluency. The next day, cells were cultured in neuroepithelial progenitor (NEP) induction medium for 6 days, followed by motor neuron progenitor (MNP) induction medium containing retinoic acid and Purmorphamine for another 6 days. MNPs were then transferred to suspension culture and maintained in motor neuron differentiation medium with continued exposure to retinoic acid and Purmorphamine. After 6 days, neurospheres were dissociated and plated on Matrigel-coated plates in motor neuron maturation medium containing Compound E, cAMP, Laminin, GDNF, and BDNF. Differentiated motor neurons were maintained for up to 3 months, with partial medium changes twice per week.

Immunoblotting

The cultured cells and iPSC-derived cortical or motor neurons were washed with PBS (Corning, 21–031-CV) prior to lysis. For cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) analysis, growth factor withdrawal was performed for 7 days in 2-month-old iPSC-derived FTD3 cortical neurons and for 10 days in 3-month-old iPSC-derived sALS motor neurons before collection. The cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89901) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78442) and incubated for 30 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris, and the supernatants were collected and proteins were quantified using a Pierce BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23227). Protein samples were mixed with Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610747) containing beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, M3148) and heated at 95 °C for 10 min. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, IPFL00010) using a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer device (Bio-Rad, 1704150). Membranes were blocked with Odyssey PBS Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, 927–40010) at room temperature for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CHMP2B (Abcam, ab33174, 1:1000 and Invitrogen, MA5-21591, 1:1000), FLAG (Sigma, F1804, 1:10,000 and Cell Signaling, 2368S, 1:1000), SIRT1 (Proteintech, 13161-1-AP, 1:1000; Abcam, ab110304, 1:1000; and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, p4A10, 1:100), mCherry (Abcam, ab167453, 1:1000 and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-101526, 1:1000), Acetylated p53 (Lys382) (Cell Signaling Technology, 2525S, 1:1000), p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-126, 1:3000; Proteintech, 10442-1-AP, 1:1000; and Cell Signaling Technology, 2524S, 1:1000), Phosphorylated p53 (Ser15) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9284 L, 1:1000), GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-32233, 1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology, 2118S, 1:2000; and Proteintech, 10494-1-AP, 1:2000), Beta-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-47778; 1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology, 4970 L, 1:2000; and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, JLA20, 1:2000), Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9661 L, 1:1000), XRCC5/Ku80 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2753S, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, 2180S, 1:1000; and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-5280, 1:1000), XRCC6/Ku70 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-17789, 1:1000 and Cell Signaling Technology, 4588S, 1:1000), Phosphorylated H2AX (Sigma, 05-636, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, 9718S; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-517348, 1:2000; and Abcam, ab11174, 1:1000), Histone H2Av (Active Motif, 61751, 1:1000), Phosphorylated H2Av (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, UNC93-5.2.1, 1:500), Phosphorylated ATM (Abcam, ab81292, 1:1000). After washing with TBST (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28360), membranes were incubated with IRDye secondary antibodies against IRDye® 800CW Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-32212, 1:10,000), IRDye® 800CW Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-32213, 1:10,000), IRDye® 680CW Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-68070, 1:10,000) and IRDye® 680CW Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-68071, 1:10,000) and visualized using the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Quantification of CHMP2BWT, CHMP2BΔ10, and CHMP2BIn5 expression

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy kit and treated with DNase I. RNA (500–900 ng) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using random hexamers and MultiScribe reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 system with SYBR Select Master Mix. Ct values were normalized to cyclophilin, and the relative expression of each CHMP2B variant was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primers used were:

CHMP2BWT: 5′-CAATGCAGAATTTCCAGAAGG-3′, 5′-GCTTTGGCCATCTTTCCAGA-3′

CHMP2BΔ10: 5′-CAATGCAGAATTTCCAGAAGG-3′, 5′-AGCTGATGGAGCTTTCCAGA-3′

CHMP2BIn5: 5′-CAATGCAGAATTTCCAGAAGG-3′, 5′-GATGATGTTCATACCTTTCCAGA-3′

Quantification of mutant and wild-type CHMP2B mRNA transcripts

The relative abundance of CHMP2BWT, CHMP2BΔ10, and CHMP2In5 isoforms was determined by qPCR using isoform-specific primers and a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of a plasmid containing all three amplicons. PCR products were inserted using specific restriction enzymes (CHMP2BWT: HindIII/BamHI, CHMP2BΔ10: NotI/XbaI, CHMP2BIn5: BamHI/NotI). The relative transcript levels were calculated and expressed as a percentage of CHMP2BWT.

Comet assay

The comet assay was performed in 3-month-old iPSC-derived cortical neurons using the Comet Assay Kit (Abcam, ab238544). The assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, neurons were embedded in agarose and lysed to remove cellular proteins, leaving DNA in its native state. The samples were subjected to electrophoresis in TBE Electrophoresis Solution, which facilitates the migration of fragmented DNA. After electrophoresis, slides were stained with a fluorescent DNA-binding dye and analyzed under a fluorescence microscope. DNA damage was quantified by measuring tail length, tail moment, and tail DNA percentage using the OpenComet plugin in ImageJ.

Neuronal viability

Neuronal viability was assessed in 2-month-old iPSC-derived FTD3 cortical neurons and 3-month-old iPSC-derived sALS motor neurons after growth factor withdrawal. At the indicated time points, culture media were collected and analyzed using the Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH; Roche, 11644793001) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay quantifies the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the culture medium as an indicator of membrane damage. After incubation with the detection reagent, absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader. Neuronal viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the control group by normalizing the absorbance values.

Cytotoxicity (%) was calculated based on the manufacturer’s manual, by subtracting the spontaneous LDH release (low control) from the experimental value and dividing it by the difference between the maximum (high control) and low control LDH release, followed by multiplication by 100. To represent neuronal viability, Inverse LDH release (%) was calculated by subtracting the cytotoxicity value from 100. Thus, lower LDH release corresponds to higher neuronal viability, and data are expressed as the percentage of viable neurons relative to the control group.

Lentivirus production and infection

Lentiviral shRNA clones targeting p53 (TRCN0000003755, TRCN0000003753) or XRCC5 (TRCN0000039838, TRCN0000039839) were obtained from the RNAi Core Facility at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. Lentiviral backbone and packaging plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 3000. After 48 h, the viral supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and concentrated using the Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech, 631231). The virus was resuspended in PBS and stored at −80 °C until use. For overexpression or knockdown experiments, 1.5-month-old iPSC-derived cortical neurons were transduced with lentivirus for two weeks. To induce cellular stress, neurons were subjected to neurotrophic factor withdrawal for an additional two weeks, followed by immunoblot or cytotoxicity assay.

Drosophila strains

Flies were maintained on a standard yeast diet at 25 °C in an incubator. w1118 was used as a wild-type control. The following fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center or the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center: w1118, GMR-Gal4, and UAS-mCherry RNAi (BL35785), UAS-Ku80 RNAi-1 (v37110), UAS-Ku80 RNAi-2 (v37111), UAS-Ku80 RNAi-3 (BL62531), UAS-Ku80 RNAi-4 (BL27710), UAS-SIRT1-1 (BL444216), UAS-SIRT1-2 (BL444217), GUS-p53 (BL6584), UAS-p53 RNAi-1 (v38235), UAS-p53 RNAi-2 (v10692), UAS-p53 RNAi-3 (v103001), and UAS-p53 RNAi-4 (v45139). Recombinant flies expressing GMR-Gal4, UAS-CHMP2BIn5 and GMR-Gal4, UAS-CHMP2BWT were generated previously19.

Drosophila eye morphological defects analysis

Flies for eye phenotype analysis were crossed and raised at 27 °C to enhance CHMP2BIn5 expression. Adult flies aged for ~10 days were examined under a dissecting microscope (Nikon, SMZ 1500). The severity of eye morphological defects, including pigmentation loss and rough eye phenotype, was categorized as low, medium, or high. The percentage of flies in each category was quantified and analyzed using a chi-square test. Both male and female flies were included in all experiments.

Quantitative analysis of the adult Drosophila eye surface area

Male adult flies were collected 3–5 days after eclosion, and eye images were captured using a Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope equipped with a digital camera. The surface area of the compound eye was quantified by outlining the perimeter of ommatidia using ImageJ software. Relative eye surface areas were calculated and compared among different genotypes.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Forty fly heads were collected in 1.5-ml tubes and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Qiagen, 79306) and purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74106). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, N8080234). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Select Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4472918) on a QuantStudio 3 System. The primers used were Drosophila p53 (forward: 5′-ACATGAGCCGGTCTGTAACC-3′ and reverse: 5′-TTTCTTTTCGCCCGATACAC-3′) and Actin42A (forward: 5′-TCTTACTGAGCGCGGTTACAG-3´ and reverse: 5′-ATGTCGCGCACAATTTCAC-3′). Ct values were normalized to internal controls, and relative mRNA expression was calculated using the delta-delta Ct method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using chi-square tests, paired or unpaired two-tailed t-tests, one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc tests, or two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison tests in GraphPad Prism version 10. Statistical significance was defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns: not significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. Raw data are available upon request from the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bang, J., Spina, S. & Miller, B. L. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet 386, 1672–1682 (2015).

Grossman, M. et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9, 40 (2023).

Boeve, B. F., Boxer, A. L., Kumfor, F., Pijnenburg, Y. & Rohrer, J. D. Advances and controversies in frontotemporal dementia: diagnosis, biomarkers, and therapeutic considerations. Lancet Neurol. 21, 258–272 (2022).

Greaves, C. V. & Rohrer, J. D. An update on genetic frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. 266, 2075–2086 (2019).

Taylor, J. P., Brown, R. H. Jr. & Cleveland, D. W. Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 539, 197–206 (2016).

Feldman, E. L. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 400, 1363–1380 (2022).

Mead, R. J., Shan, N., Reiser, H. J., Marshall, F. & Shaw, P. J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a neurodegenerative disorder poised for successful therapeutic translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 185–212 (2023).

Neumann, M. et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133 (2006).

Ling, S. C., Polymenidou, M. & Cleveland, D. W. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron 79, 416–438 (2013).

Gao, F. B., Almeida, S. & Lopez-Gonzalez, R. Dysregulated molecular pathways in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia spectrum disorder. EMBO J. 36, 2931–2950 (2017).

Karch, C. M. et al. Selective genetic overlap between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and diseases of the frontotemporal dementia spectrum. JAMA Neurol. 75, 860–875 (2018).

Abramzon, Y. A., Fratta, P., Traynor, B. J. & Chia, R. The overlapping genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Front. Neurosci. 14, 42 (2020).

Cook, C. & Petrucelli, L. Genetic convergence brings clarity to the enigmatic red line in ALS. Neuron 101, 1057–1069 (2019).

Vietri, M., Radulovic, M. & Stenmark, H. The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 25–42 (2020).

Skibinski, G. et al. Mutations in the endosomal ESCRTIII-complex subunit CHMP2B in frontotemporal dementia. Nat. Genet. 37, 806–808 (2005).

Hofmann, J. W., Seeley, W. W. & Huang, E. J. RNA binding proteins and the pathogenesis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 14, 469–495 (2019).

Lee, J. A., Beigneux, A., Ahmad, S. T., Young, S. G. & Gao, F. B. ESCRT-III dysfunction causes autophagosome accumulation and neurodegeneration. Curr. Biol. 17, 1561–1567 (2007).

Lu, Y., Zhang, Z., Sun, D., Sweeney, S. T. & Gao, F. B. Syntaxin 13, a genetic modifier of mutant CHMP2B in frontotemporal dementia, is required for autophagosome maturation. Mol. Cell 52, 264–271 (2013).

Jun, Y. W., Lee, S., Ban, B. K., Lee, J. A. & Gao, F. B. Non-muscle MYH10/myosin IIB recruits ESCRT-III to participate in autophagosome closure to maintain neuronal homeostasis. Autophagy 19, 2045–2061 (2023).

Filimonenko, M. et al. Functional multivesicular bodies are required for autophagic clearance of protein aggregates associated with neurodegenerative disease. J. Cell Biol. 179, 485–500 (2007).

Rusten, T. E. et al. ESCRTs and Fab1 regulate distinct steps of autophagy. Curr. Biol. 17, 1817–1825 (2007).

West, R. J., Lu, Y., Marie, B., Gao, F. B. & Sweeney, S. T. Rab8, POSH, and TAK1 regulate synaptic growth in a Drosophila model of frontotemporal dementia. J. Cell Biol. 208, 931–947 (2015).

Gascon, E. et al. Alterations in microRNA-124 and AMPA receptors contribute to social behavioral deficits in frontotemporal dementia. Nat. Med. 20, 1444–1451 (2014).

Dobbin, M. M. et al. SIRT1 collaborates with ATM and HDAC1 to maintain genomic stability in neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1008–1015 (2013).

Wu, Q. J. et al. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 402 (2022).

Herskovits, A. Z. & Guarente, L. SIRT1 in neurodevelopment and brain senescence. Neuron 81, 471–483 (2014).

Oberdoerffer, P. et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell 135, 907–918 (2008).

Thapa, R. et al. The role of sirtuin 1 in ageing and neurodegenerative disease: a molecular perspective. Ageing Res. Rev. 102, 102545 (2024).

Vaziri, H. et al. hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell 107, 149–159 (2001).

Gu, W. & Roeder, R. G. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell 90, 595–606 (1997).

Yang, H., Yan, B., Liao, D., Huang, S. & Qiu, Y. Acetylation of HDAC1 and degradation of SIRT1 form a positive feedback loop to regulate p53 acetylation during heat-shock stress. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1747 (2015).

Ford, J., Jiang, M. & Milner, J. Cancer-specific functions of SIRT1 enable human epithelial cancer cell growth and survival. Cancer Res. 65, 10457–10463 (2005).

Zhang, Y. et al. Patient iPSC-derived neurons for disease modeling of frontotemporal dementia with mutation in CHMP2B. Stem Cell Rep. 8, 648–658 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. The enhanced association between mutant CHMP2B and spastin is a novel pathological link between frontotemporal dementia and hereditary spastic paraplegias. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 10, 169 (2022).

Linares, G. R. et al. SYF2 suppression mitigates neurodegeneration in models of diverse forms of ALS. Cell Stem Cell 30, 171–187.e114 (2023).

Lopez-Gonzalez, R. et al. Partial inhibition of the overactivated Ku80-dependent DNA repair pathway rescues neurodegeneration in C9ORF72-ALS/FTD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9628–9633 (2019).

Maor-Nof, M. et al. p53 is a central regulator driving neurodegeneration caused by C9orf72 poly(PR). Cell 184, 689–708.e620 (2021).

Olive, P. L. & Banáth, J. P. The comet assay: a method to measure DNA damage in individual cells. Nat. Protoc. 1, 23–29 (2006).

Hong, Y. et al. Deep learning method for comet segmentation and comet assay image analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 18915 (2020).

Madigan, J. P., Chotkowski, H. L. & Glaser, R. L. DNA double-strand break-induced phosphorylation of Drosophila histone variant H2Av helps prevent radiation-induced apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3698–3705 (2002).

Hill, S. J. et al. Two familial ALS proteins function in prevention/repair of transcription-associated DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E7701–e7709 (2016).

Mitra, J. et al. Motor neuron disease-associated loss of nuclear TDP-43 is linked to DNA double-strand break repair defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 4696–4705 (2019).

Konopka, A. et al. Impaired NHEJ repair in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is associated with TDP-43 mutations. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 51 (2020).

Giannini, M. et al. TDP-43 mutations link Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with R-loop homeostasis and R loop-mediated DNA damage. PLoS Genet. 16, e1009260 (2020).

Fang, M. et al. Loss of TDP-43 function contributes to genomic instability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1251228 (2023).

Kok, J. R. et al. DNA damage as a mechanism of neurodegeneration in ALS and a contributor to astrocyte toxicity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 5707–5729 (2021).

Nakahata, Y. et al. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control. Cell 134, 329–340 (2008).

Yang, X. et al. The neuroprotective effects of SIRT1 on NMDA-induced excitotoxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2823454 (2017).

Lopez-Gonzalez, R. et al. Poly(GR) in C9ORF72-related ALS/FTD compromises mitochondrial function and increases oxidative stress and DNA damage in iPSC-derived motor neurons. Neuron 92, 383–391 (2016).

Choi, S. Y. et al. C9ORF72-ALS/FTD-associated poly(GR) binds Atp5a1 and compromises mitochondrial function in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 851–862 (2019).

Konopka, A. & Atkin, J. D. DNA damage, defective DNA repair, and neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 786420 (2022).

Vousden, K. H. & Prives, C. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell 137, 413–431 (2009).

Kastenhuber, E. R. & Lowe, S. W. Putting p53 in context. Cell 170, 1062–1078 (2017).

Taskina, D., Zhu, C., Schwab, N. & Hazrati, L. N. Brain pathology and symptoms linked to concussion history: beyond chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Commun. 6, fcad314 (2024).

Blackburn, E. H., Epel, E. S. & Lin, J. Human telomere biology: a contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science 350, 1193–1198 (2015).

Welch, G. & Tsai, L. H. Mechanisms of DNA damage-mediated neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease. EMBO Rep. 23, e54217 (2022).

Liu, E. Y. et al. Loss of nuclear TDP-43 is associated with decondensation of LINE retrotransposons. Cell Rep. 27, 1409–1421 (2019).

Chang, Y. H. & Dubnau, J. The Gypsy endogenous retrovirus drives non-cell-autonomous propagation in a Drosophila TDP-43 model of neurodegeneration. Curr. Biol. 29, 3135–3152 (2019).

Miller, M. B. et al. Somatic genomic changes in single Alzheimer’s disease neurons. Nature 604, 714–722 (2022).

Almeida, S. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell models of progranulin-deficient frontotemporal dementia uncover specific reversible neuronal defects. Cell Rep. 2, 789–798 (2012).

Lee, S. et al. Downregulation of Hsp90 and the antimicrobial peptide Mtk suppresses poly(GR)-induced neurotoxicity in C9ORF72-ALS/FTD. Neuron 111, 1381–1390.e1386 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yu Zhang for generating the published mutant CHMP2B iPSC lines in Dr. Kristine Freude’s lab. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37NS057553 and R01NS101986 to F.-B.G.), Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2019R1A6A3A03034014 to Y.-W.J.). The generation of one pair of isogenic FTD3 lines by S.A. was partially supported by Alzheimer’s Association (2016-NIRG-396129).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-W.J. and S.L. performed most experiments. S.A. generated one pair of isogenic iPSC lines with or without the FTD3 point mutation. K.K.F. provided another pair of isogenic iPSC lines with or without the FTD3 point mutation. J.I. provided 4 control and 4 sALS iPSC lines. Y.-W.J., S.L. and F.-B.G. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. F.-B.G. directed the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Josh Dubnau and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jun, YW., Lee, S., Almeida, S. et al. The Ku80-p53-SIRT1 axis in DNA damage response contributes to sporadic and familial ALS and FTD. Nat Commun 17, 1007 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67749-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67749-7

This article is cited by

-

Mislocalization of FTD3-associated mutant CHMP2B to the nucleus of human neurons due to loss of a nuclear export signal

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2026)