Abstract

As a sister genus to Taxus, Pseudotaxus holds significant importance for studying the origin and evolution of the taxane biosynthesis pathway. However, the reference genome of Pseudotaxus chienii is yet unavailable. Here, we report a chromosome-level genome assembly of P. chienii (15.6 Gb). We show that P. chienii only possesses a partial taxane pathway, which terminates before taxane 2α-O-benzoyl transferase (TBT), a crucial enzyme responsible for the production of 10-deacetylbaccatin III. With the emergence of the Taxus genus, the limitation posed by the lacking of functional TBT is overcome, allowing for the extension of the existing taxane biosynthesis pathway into a complete Taxol biosynthesis. The protein structure of metal ion catalysis sites in taxadiene synthase (TS) is conserved across the Pseudotaxus and Taxus genera, providing potential sites for enhancing TS activity through enzyme engineering. This comparative genomic analysis contributes to our understanding of the origin and evolution of taxane biosynthesis within the Taxaceae family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Taxaceae, a well-known family of non-flowering conifers with considerable medicinal and ecological value, is primarily distributed across Asia, North America, and Europe1. Plants of the genus Taxus, which belong to the Taxaceae family, have gained prominence for their secondary metabolite, paclitaxel (also named as Taxol), a chemotherapeutic agent applied in the treatment of various cancers2. Due to its low abundance in natural Taxus tissues, the price of Taxol has been steadily increasing3,4. Therefore, studying the origin and evolution of Taxus-specific Taxol biosynthesis is of great significance for future research.

Phylogenetic analysis speculated that Taxaceae sensu lato comprises six extant genera: Amentotaxus, Austrotaxus, Pseudotaxus, Taxus, Torreya, and Cephalotaxus 5. Pseudotaxus chienii, belonging to the monotypic genus Pseudotaxus, is an endangered conifer endemic to China6. The iconic feature of the P. chienii tree is the peculiar white aril and stomatal bands on the backlit surface of leaves1,7. As an old, rare tree, P. chienii is an ideal material for studying environmental adaptation and evolution. The Pseudotaxus genus, which has one living representative, diverged from its sister genus, Taxus, approximately 54-65 million years ago (MYA) (Palaeocene or Eocene), making it an evolutionary relict7,8. Evolutionary analyses of P. chienii genus provided insights into the mechanisms driving speciation for conifers9.

Diterpenoids, comprised of several isoprene structural cores, are derived from geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP)10. Most diterpenoids share a common upstream biosynthetic pathway known as the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, which supplies essential precursors. They depend on diterpene synthases (diTPSs) to initiate the species-specific diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway11. The functional diversity of diterpenoids is attributed to the core sequences of diTPS, which are categorized into three distinct types: class I (DDXXD/E motif), class II (DXDD motif), and bifunctional class I/II diTPSs12. In gymnosperms, bifunctional diTPSs are the predominant type, in contrast to the monofunctional diTPSs found in angiosperms13. For example, AgAS from Abies grandis, GbLPS from Ginkgo biloba, and SmCPSKSL1 from Selaginella moellendorffii are typical bifunctional diTPSs14,15,16. Despite being a gymnosperm, the taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene derived from Taxus plants is synthesized directly by a class I diTPS, taxadiene synthase (TS)17. Once the taxane core is formed, a series of taxoid hydroxylases, including the 2α-, 5α-, 7β-, 9α-, 10β-, and 13α-hydroxylases, are involved in modifying the core18. The origin and evolution of such a complex pathway for synthesizing Taxol in Taxus plants remain unknown.

Since the first isolation of Taxol from the stem bark of T. brevifolia, researchers have also detected taxanes in other plant species19. Taxol and its precursor, baccatin III, were identified in the leaves of Cephalotaxus hainanensis, an important member of the Taxaceae family20. Anticancer taxanes, including 10-deacetylbaccatin III, baccatin III, cephalomannine, and paclitaxel, were detected in Turkish Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.)21. However, it remains unclear whether the Taxol biosynthesis pathway in P. chienii is fully established. Recently, chromosome-level genomes of Taxus and Torreya have been published in succession, deepening our understanding of Taxaceae plants22,23,24,25. Recently, the coding genes for the last several key enzymes, such as TOT1, T9a oxidase, TCPR, and CYP1, were cloned, which improved the Taxol biosynthesis pathway26,27,28,29.

In this study, we assemble the genome of P. chienii. Our comparative genomic analysis contributes to our understanding of the origin and evolution of taxane biosynthesis and provides insights into the genome structure and organization of the Taxaceae family.

Results

Visualization of metabolite locations in the stems and leaves of P. chienii

P. chienii is a rare gymnosperm with limited research, and its economic value remains unclear. Exploring the medicinal active ingredients of P. chienii is essential for the effective and protective utilization of this ancient and rare species, which has a long history. Given that taxanes, iconic metabolites of the Taxus genus, are a type of diterpenoid compound, MALDI-IMS was employed to detect various potential diterpenoids in the leaves and stems of P. chienii (Fig. 1a). The optical images of its leaf and stem sections are shown in Fig. 1b. The MALDI-IMS analysis produced a series of colored maps comprising a total of 9,999 data points, indicating the tissue-specific accumulation of active ingredients (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Data 1). After database matching, most metabolites were annotated and categorized into various KEGG pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a A picture of the twig of P. chienii. The blue line indicated the sample site of the leaf, and the red line indicated the sampling site of the stem. b The optical images of the P. chienii leaf and stem sections. c Mean mass spectrogram and segmentation analysis of the P. chienii samples. Stem and leaf samples were performed on a single chip. d Imaging analysis of ten typic diterpenes in the leaves and stems of P. chienii. Color scale ranges from 0 to 100%. Blue indicated a low accumulation level, and red indicated a high accumulation level. e Proportion of various metabolites in leaves and stems was showed by a histogram. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

All identified metabolites were separated into five principal components (PCs) associated with different stem and leaf tissues. For the stems, four major tissues, including endodermis (PC1), epidermis (PC2/5), xylem (PC4), and pith (PC3), were visualized (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). To identify stem tissue-specific accumulated metabolites (SAMs), clustering analyses identified 1512 endodermis-, 3237 epidermis-, 1494 pith-, and 1531 xylem-SAMs. In addition, 390 metabolites accumulated in both epidermis and xylem (Supplementary Fig. 2c). For the leaves, three major tissues, including epidermis (PC1), mesophyll (PC2/3/5), and bundle sheath (PC4), were visualized (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). To identify leaf tissue-SAMs, clustering analyses identified 1833 epidermis-, 5201 mesophyll-, and 1248 bundle sheath-SAMs. In addition, 336 metabolites accumulated in both epidermis and mesophyll (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Several active diterpenoids were detected using the MS-Imaging analysis method (Supplementary Data 2). In the stems, geranyl-PP, a core precursor for terpenoid synthesis, and 3D,7D,11D-phytanic acid were predominantly accumulated in the epidermis; while ζ-carotene epoxide, presqualene-PP, and taxine B were highly concentrated in the xylem. Additionally, erinacine D, resiniferatoxin, jesaconitine, and azadirachtin exhibited a non-tissue-specific accumulation pattern (Fig. 1d). The proportions of different active ingredients in the stems and leaves are shown in Fig. 1e.

Genome assembly and annotation

To explore the chromosome-level genome of P. chienii, twigs from a wild P. chienii tree were collected for genome sequencing (Fig. 2a). A total of 652.4 Gb of Illumina clean data was obtained. The P. chienii genome was estimated to be 16.8 Gb (~ 39ⅹ) based on 19-mer analyses (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). By using 586.5 Gb PacBio HiFi reads, a 15.6 Gb non-redundant assembly was generated, comprising 954 contigs with a contig N50 of 65.6 Mb and a GC content of 35.2% (Supplementary Table 1). Using 2.34 Tb Hi-C clean data, a total of 15.5 Gb (99.0%) of the assembled sequences were anchored on 12 pseudochromosomes ranging in size from 0.8 Gb to 1.5 Gb (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4c).

a Pictures of a wild P. chienii tree used for genomic DNA sequencing. b Circos plot of P. chienii genome. Track Ⅰ represents the length of the chromosomes (Gb); Ⅱ and Ⅲ represent GC content and gene density, respectively; Ⅳ-Ⅵ represent gene expression without or with MeJA treatment, respectively; Ⅶ-Ⅸ show the distribution of transposons, Gypsy, and Copia LTRs, respectively. These features were calculated in 10 Mb windows. Center, the syntenic regions were linked by curve lines. c Analysis of insertion time based on the total LTR. d Analysis of insertion time based on different types of LTR. e Venn diagram for orthologous protein-coding gene clusters in P. chienii, T. grandis, T. mairei, T. yunnanensis, and T. wallichiana. The number in each sector of the diagram represents the total number of genes across different comparisons. f Gene family expansion and contraction during the evolution of green plants. The maximum likelihood phylogeny was built with a number of low-copy orthologous groups. Numbers on branches are the sizes of expanded (red) and contracted (green) gene families at each node.

To evaluate the completeness and accuracy of the assembly, the Illumina short reads and transcriptome data were aligned to the assembly. The result showed mapping rates of 99.33% and 98.58%, respectively. BUSCO evaluation using the protein model revealed that 85.2% (1,376 out of 1614) of the core embryophytic genes were identified in the P. chienii genome, showing relatively high completeness of genome assembly among gymnosperms (Supplementary Table 2). The LAI value was estimated to be 10.1, which is larger than the proposed standard for a reference-level assembly (LAI > 10)30, indicating a high quality of the chromosome-level assembly of P. chienii.

Genome annotation yielded 35,404 protein-coding genes with an average mRNA length of 29,725 bp were annotated. The average CDS length is 1060 bp, and the average number of exons per gene is 4.2 (Supplementary Table 3). A total of 32,166 (90.9%) completed genes could be functionally annotated by searching against various known databases (Supplementary Data 3).

Analysis of repeat sequence

The genome size of P. chienii is much larger than that of the closely related Taxus species (~ 10 Gb). We identified a greatly high percentage of repetitive sequences (86.12%) in the P. chienii genome, with transposable elements (TEs) and tandem repeats accounting for 82.73% and 3.39% of the genome, respectively. Most of the Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposon (LTR-RT) expansions in gymnosperms happened between 25 to 7 MYA. The estimation of the insertion time showed that the LTR-RT expansion in P. chienii experienced an extremely long period, the burst of LTR-RT insertions range from about 60 to 10 MYA, with the accumulation reaching a peak at about 23 MYA (Fig. 2c). These results suggested that continuous insertions of LTR-RTs leads to the giant genome of P. chienii. LTR-RTs comprise the majority of those TEs (82.06%), with Gypsy and Copia contributing 40.87% and 9.04% of the total, respectively (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 4). The results of tandem repeat sequence analysis are shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Whole genome duplication (WGD)

A synteny analysis between P. chienii and two other Taxaceae species (T. grandis and T. mairei) found that 86% and 81% of genes in P. chienii had one-to-one syntenic orthologs in T. mairei and T. grandis, respectively, while only 1% and 3% of genes in P. chienii had one-to-more synteny orthologs in T. mairei and T. grandis, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). These results indicated the lack of a recent WGD event in P. chienii. We next tried to seek evolutionary relics of WGD in P. chienii by detecting paralogous synteny gene blocks. However, we only detected 60 synteny blocks including 672 genes (~ 2.0 % of all genes), further supporting the absence of recent WGD.

Synteny comparison and gene family evolution

Homologous synteny blocks between P. chienii and other Taxaceae species were identified. The results showed that nearly perfect macro-synteny is observed among the three Taxus species, suggesting a high degree of similarity in their genomic structures. Although macro-synteny is also present between P. chienii and the Taxus species, extensive chromosomal rearrangements and intra-chromosomal inversions exist. The reorganization of the genome is even more evident when comparing the genomic structures of P. chienii and T. grandis (Supplementary Fig. 5c). These results coincide with the phylogeny of these species. We identified a core set of 10,419 gene families shared among these species, along with 5977 gene families specific to P. chienii (Fig. 2e). To investigate the evolutionary processes of gene families in P. chienii, we identified 20,986 orthologous groups across 16 land plant species, including 10 gymnosperms, 5 angiosperms, and 1 lycophyte (Fig. 2f). Phylogenetic analysis and molecular dating using 184 single-copy genes indicated that P. chienii diverged from Taxus around 48.3 million years ago. Furthermore, we found 190 expanded and only 1 contracted gene family in the common ancestor of the Taxaceae family. The extinct ancestors of Pseudotaxus and Taxus exhibited expansions and contractions of 73 and 38 gene families, respectively. The Taxus lineages uniquely contain 170 expanded and 32 contracted gene families, which may be related to their diversification compared to other Taxaceae species (Fig. 2f). P. chienii demonstrated an expansion of 161 gene families, many of which contained conserved domains linked to catabolic processes, responses to abiotic stimuli, secondary metabolic processes, and reproduction.

Identification of functional genes

GO analysis revealed a great number of environmental adaptation-related genes, including 275 defense response-related genes, 237 herbicide response-related genes, and 147 oxidative stress response-related genes (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Moreover, many metabolism-related genes, including 342 carbohydrate metabolic process-related genes, 194 lipid metabolic process-related genes, and 114 glutathione metabolic process-related genes (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Our study provides sufficient candidates to improve the metabolic flux and enhance the environmental adaptation of P. chienii. It is worth mentioning that 587 genes were grouped into a taxane biosynthesis-related GO term “paclitaxel biosynthetic process”, suggesting a potential biosynthetic ability for taxanes in P. chienii (Supplementary Fig. 6c and Supplementary Data 4).

A total of 591 putative TF genes belonging to 10 major metabolism-related TF families were identified in P. chienii (Supplementary Data 5). To investigate the evolutionary processes of TF families in the Taxaceae family, we identified an average of 1075 and 1877 TFs consisting of ten families in ten gymnosperm and eight angiosperm genomes, respectively. This indicated a 1.8-fold and a 3.2-fold increase compared to P. chienii (Supplementary Fig. 7). This suggests that the genome of P. chienii is relatively ancient and that copy number expansion of these TF families has occurred in other plant species.

Origin and evolution of the taxane biosynthesis pathway

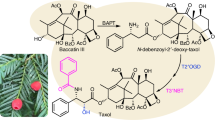

We observed that the genome of P. chienii contains many genes involved in the taxane biosynthesis, making P. chienii an ideal species for investigating the evolution of the Taxol biosynthetic pathway. A comprehensive search of the P. chienii genome revealed a complete MEP pathway, suggesting that P. chienii has the capacity to provide precursors for taxane biosynthesis. A nearly complete Taxol biosynthesis pathway has been published recently26,31. In the P. chienii genome, a partial Taxol biosynthesis pathway was identified. It is interesting that neither TBT nor BAPT genes were detected (Fig. 3a). Similar to the Taxus genus plants, most of the genes involved in the taxane biosynthesis pathway in P. chienii are arranged into two gene clusters located on Chr 9 and 11, respectively (Fig. 3b).

a The possible taxol biosynthetic pathway. The solid and dotted arrows represent the characterized and unknown reactions, respectively. Red forks indicated the genes that do not exist in P. chienii. The abbreviation is as follows: taxadiene synthase (TS), taxane 5α-hydroxylase (T5OH), taxane 13α-hydroxylase (T13OH), taxadien-5α-ol-O-acetyltransferase (TAT), Taxus cytochrome P450 reductase (TCPR), taxane 2α-hydroxylase (T2OH), taxane 7β-hydroxylase (T7OH), taxane 10β-hydroxylase (T10OH), taxane 9-oxidase (T9OH), taxane oxetanase 1 (TOT1, also named CYP1 or CYP725A55), taxane 2α-O-benzoyl transferase (TBT), 10-deacetyl-baccatin III-10-O-acetyltransferase (DBAT), 13-O-(3-amino-3-phenylpropanoyl) transferase (BAPT), taxane 2’α-hydroxylase (T2’OH), N-debenzoyl-2’-deoxytaxol-N-benzoyltransferase (DBTNBT). b Overview of the known genes involved in taxane biosynthesis. (c) Genome rearrangements between P. chienii and T. wallichiana. Physical and genetic maps of the 142.04–245.71 Mb region of chromosome 9 and 6.56–101.93 Mb region of chromosome 11 were extracted from the P. chienii genome, and the 195.41–486.53 Mb region of chromosome 10 was extracted from the T. wallichiana genome. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we found that 14 identified taxane biosynthesis-related genes were located in the 142.04–245.71 Mb region of chromosome 9 and the 16.56–101.93 Mb region of chromosome 11, respectively (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Data 6). Previous study showed that all these corresponding genes are distributed on the 195.41–486.53 Mb region of chromosome 10 of T. wallichiana23. Given the conserved genome structures between P. chienii and T. wallichiana, as well as their phylogenetic relationship, it appears that the taxane biosynthesis gene-enriched regions of chromosomes 9 and 11 in P. chienii have undergone translocations with inversions, aligning with the corresponding region of chromosome 10 in T. wallichiana (Fig. 3c). Despite evolutionary divergence, P. chienii and T. wallichiana still share an ancestral lineage, suggesting that taxane biosynthesis pathway has a common origin.

Taxusin is one of potential end products of taxane biosynthesis pathway in P. chienii

Untargeted metabolomic analysis was conducted to detect the variations in the metabolic profiles of three typical Taxaceae species (Supplementary Fig. 8a and Supplementary Data 7). A PCA indicated clear separation among the metabolomes of P. chienii, T. wallichiana, and T. grandis (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Based on their annotations, 8,780 metabolites were identified (Supplementary Fig. 8c).

To elucidate the completeness of the Taxol biosynthesis pathway in three closely related Taxaceae species, we compared the genomes of P. chienii, T. wallichiana, and T. grandis23,25. The complete MEP pathway exists in all three selected Taxaceae species (Fig. 4a). TBT catalyzes the conversion of 2-debenzoyl-7,13-diacetylbaccatin III to 7,13-diacetylbaccatin III32. TOT1 (from T. mairei), also named CYP1 (from T. media), catalyzes an oxidative rearrangement in paclitaxel oxetane formation26,28,29. The absence of TBT and TOT1 (also known as CYP1 or CYP725A55) may be a significant reason why P. chienii is unable to synthesize 10-deacetylbaccatin III and the subsequent intermediates following 10-deacetylbaccatin III. Certainly, there may be another pathway that consumes an amount of 10-deacetylbaccatin III or baccatin III, making them undetectable. Moreover, the T2OH and T7OH genes were identified in P. chienii (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 9). A feeding experiment showed that the activities of T2OH and T7OH from P. chienii were similar to those from T. mairei (Supplementary Fig. 10). The quality control parameters and raw spectra were showed in Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Fig. 11–15. Considering the presence of both T2OH and T7OH, taxusin can be hydroxylated into 2α,7β-dihydroxytaxusin33. Taxusin and its analogs are highly acetylated intermediates in an alternative route of the Taxol biosynthesis pathway26. We hypothesized that blocking at TBT and TOT1 (CYP1) might redirect metabolic flow towards taxusin or its analogs instead of Taxol (Fig. 4b). No homologous genes for TS were identified in T. grandis, indicating that this species lacks the taxane biosynthesis pathway.

a The number of genes encoding each key enzyme involved in the taxane biosynthesis. b Speculative metabolic pathway block in P. chienii. c Determination of the contents of taxusin and 10-deacetylbaccatin III in P. chienii, T. wallichiana, and T. grandis. d MS spectra of taxusin in P. chienii and T. wallichiana. e The contents of taxusin in the P. chienii and T. wallichiana twigs. ****P < 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values +/− SD of six biological repeats. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. Bar graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 10.6. f Determination of the contents of taxol and its derivatives, including 10-deacetyltaxol, 10-deacetyl-7-xylosyltaxol C, 13-acetyl-9-dihydrobaccatin III, and cephalomannine. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As expected, taxusin is highly accumulated in P. chienii, particularly in its stems, while it is minimally accumulated in T. wallichiana and undetected in T. grandis. 10-Deacetylbaccatin III is highly accumulated T. wallichiana and undetected in both of P. chienii and T. grandis (Fig. 4c). LC-MS/MS analysis confirmed that the content of taxusin in the twigs of P. chienii is 3.5-fold higher than that in T. wallichiana (Fig. 4d, e). Several other taxoids, including Taxol, 10-deacetyltaxol, and 10-deacetyl-7-xylosyltaxol C, were only detected in T. wallichiana through untargeted metabolomic analysis (Fig. 4f). Taxusin can serve as a precursor for Taxol synthesis because of its exceptionally high content in P. chienii.

Functional identification of the TS genes in P. chienii

To date, Taxus is the only genus among gymnosperms known to produce Taxol, although all plants possess the TPS enzymes, which catalyze isoprenoid cyclization reactions to produce a variety of natural products34. The TS enzymes catalyze the initial key step of taxane biosynthesis from GGPP. Phylogenetic analysis has revealed that TPSs from gymnosperms form a distinct clan, while TPSs from angiosperms are grouped into two separate branches, consisting of Class I and Class II TPSs (Fig. 5a).

a Phylogenetic analysis of the TPS family members in different plants. Purple stars indicated the TPS from P. chienii (PcTS1/2). Green dots indicated the TPS containing Class I (DDXXD/E) motif, red dots indicated the TPS containing Class II (DXDD) motif, and yellow dots indicated the TPS containing the bifunctional motif (DDXXD/E + DXDD). b Identification of positive transgenic tobacco expressing PcTS1 and TwTS1, respectively. c GC–MS analysis of hexane extracts from the seedlings expressing PcTS1 and TwTS1, and controls (CK), respectively. Time (11.857) indicates the target peak of taxadiene. d Mass spectra profile of the compound at 11.857 min matched exactly with the taxadiene mass spectra. e Multiple sequence alignment analysis of the DXDD and DDXXD/E motifs from different TPS proteins. f Structure modeling of PcTS1 by the SWISS-MODEL program using 3p5p.1.A model as template. The bioactive center of PcTS1 zoom in through a red box. g Protein structure analysis of the typical TPSs from the Angiosperm (Class I), Angiosperm (Class II), and other gymnosperms (bifunctional TPS), respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To confirm the function of PcTS1 in the initial step of the taxane biosynthesis pathway, pBWA(V)HS-PcTS1 vector was constructed and genetic transformed into N. benthamiana to produce transgenic seedlings (Fig. 5b). The leaf samples expressing PcTS1 were extracted using hexane and analyzed via GC-MS. As expected, we a peak at a RT of 11.875 mins in samples expressing PcTS1 and TwTS1, respectively (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 16). The mass spectrum matched with the analog of taxadiene, eicosane (Fig. 5d). Similar to its homologous gene in Taxus, the heterologous expression of PcTS1 can also be utilized for the heterologous production of taxadiene in tobacco.

Protein structure analysis of TPSs from Taxaceae

Interestingly, TPSs from the Taxaceae family differ from those found in other gymnosperms, as they belong to Class I, while TPSs from other gymnosperms are classified as bifunctional. Multiple sequence alignment analysis showed that the TPSs from other gymnosperms contain both of the DXDD and DDXXD/E motifs, as well as the (N,D)DXX(S,T)XXXE motif; however, TPSs from the Taxaceae family lack the characteristic DXDD motif (Fig. 5e). A previous study reported the X-ray crystal structure and substrate binding sites of the TS from the Pacific yew (T. brevifolia)35. Using the known 3p5p.1.A model as a template, the 3D structure and substrate/Mg2+ binding sites of TS1 from P. chienii were predicted using the SWISS-MODEL program. The amino acid residues forming DDXXD/E motif, such as 668-D, 669-D, 670-M, 671-A, and 672-D, and (N,D)DXX(S,T)XXXE motif, such as 812-N, 813-D, and 820-E, were surrounding the Mg2+ binding sites, suggesting that the DDXXD/E and (N,D)DXX(S,T)XXXE motifs are essential for catalytic activity, whereas the DXDD motif is not (Fig. 5f). The 3D structures of six typic TPSs, OcCPSsyn and ScCPS from Class II, GrTPS4 and AtEKS from Class I, and PsTPS_LAS and AgAS from bifunctional TPS group, were analyzed (Fig. 5g). TM-score analysis demonstrated that PcTS1 exhibit a greatest structural similarity to the bifunctional TPSs and a lowest structural similarity to the Class II TPSs (Supplementary Table 8).

CYP super-family in P. chienii

CYP superfamily-mediated oxygenation plays crucial roles in the regulation of plant secondary metabolism. Genes from the CYP725 clan have been reported to participate in Taxol biosynthesis36. In P. chienii, 548 genes from the CYP superfamily were identified and categorized into 52 clans, with 62 of these genes belonging to the CYP725 clan (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Data 8). Phylogenomic analysis demonstrated that several CYP Clans, including CYP725, CYP728, CYP867, and CYP98, were greatly expanded in the Taxaceae family compared to nine other representative species, which encompass gymnosperms, angiosperms, and bryophytes (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Data 9). The genes from the CYP725 clan are primarily distributed in Chr 9 (24 genes) and Chr11 (37 genes), suggesting that the CYP725 clan has undergone large-scale expansion due to tandem duplication events (Fig. 6b).

a Heat map of the number of CYP450 genes in P. chienii and other 10 representative plant species. Each CYP450 family is represented as a square, with the blue color representing the number of genes in the corresponding family. The heatmap scale ranges from 0 to 100. b Distribution of CYP725 subfamily genes on the chromosomes 9 and 11 in P. chienii. The color bar showed the number of CYP725 genes distributed in different chromosomes. c The expression pattern of CYP450 family genes under MeJA treatments. d The expression levels of taxusin biosynthesis-related genes under MeJA treatments. The heatmap scale ranges from 0 ~ 1000 FPKM. e MS spectra of taxusin in CK and MeJA treated samples. f The accumulation level of taxusin in the twigs of P. chienii under CK and MeJA treatments (24 h and 48 h). Each value is the mean ± standard deviation of six biological repeats. ****P < 0.0001 and **P < 0.01. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. Bar graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 10.6. g The average numbers of two reported MeJA responsive cis-elements, G-box (CACGTGG) and G-box like (AACGTG), in the promoters of CYP genes and CYP725 genes, were counted in ‘+’ and ‘−’ directions, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Expression response to MeJA treatment

Under MeJA treatment, a total of 3,338 and 4,191 DEGs were identified at 24 h and 48 h, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18a). Most of the DEGs were regulated by MeJA treatment at both 24 h and 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 18b). GO enrichment analysis revealed that the MeJA-responsive genes were significantly enriched in the GO terms ‘paclitaxel biosynthetic process’ and ‘taxoid 14-beta-hydroxylase activity’ (Supplementary Fig. 18c).

Expression analysis showed that only the P. chienii CYP725 subfamily genes were specifically up-regulated compared to the other CYP subfamilies by MeJA treatments (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, the majority of the identified taxane biosynthesis-related genes were significantly up-regulated by MeJA treatment (Fig. 6d), suggesting that taxane biosynthesis was induced by MeJA treatment. LC-MS/MS analysis confirmed that the content of taxusin in the MeJA-treated twigs of P. chienii is 4.7- and 4.4-fold higher than that in the CK twigs (Fig. 6e, f and Supplementary Table 9).

To elucidate the genetic basis of the MeJA-induced expression patterns of CYP725 subfamily genes and other identified taxane biosynthesis-related genes, we extracted their 1500-bp promoter sequences from the P. chienii genome. We counted the average numbers of two reported MeJA-responsive cis-elements, G-box (CACGTGG) and G-box-like (AACGTG), in the promoters of CYP genes and CYP725 genes in both the ‘+’ and ‘−’ directions, respectively. The average numbers of these cis-elements in the promoters of all protein-coding genes were treated as controls. The average number of G-box (+) and G-box (−) in the CYP725 promoters were 0.23 and 0.08, respectively, higher than those in the CYP promoters (0.07 and 0.06). The average numbers of G-box-like (+) and G-box-like (−) in the CYP725 promoters were 0.33 and 0.47, respectively, also significantly higher than those in the CYP promoters (0.14 and 0.16). Interestingly, the above MeJA-responsive cis-elements were greatly enriched in the promoters of the identified taxane biosynthesis-related genes (Fig. 6f). This suggests a possible explanation for the increased expression levels of CYP725 family genes and taxane biosynthesis-related genes under MeJA treatment.

Transcription regulation of taxusin biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of active ingredients in medicinal plants is coordinated by various complex transcriptional regulatory networks37. We identified 78 MeJA responsive TFs by integrating genomic and transcriptomic data (Supplementary Data 10 and Supplementary Fig. 19a). Most of the MeJA responsive TFs were significantly up-regulated by the MeJA treatment, indicating their important roles in the MeJA-induced accumulation of active ingredients in P. chienii (Supplementary Fig. 19b). Pearson correlation analysis revealed several taxane biosynthesis-related TF genes (Supplementary Fig. 19c). Four important cis-elements, including ABRE and G-box (bHLH binding elements), MBE (MYB binding element), and W-box (WRKY binding element), were identified in the promoter regions of the taxane biosynthesis-related genes (Supplementary Fig. 19d). Our data suggest that MYB12, MYB13, bHLH18, and WRKY6 may serve as potential regulators involved in the regulation of taxane biosynthesis in P. chienii.

Discussion

P. chienii, commonly known as white-berry yew, has a limited geographical distribution in several southern provinces in China38. Taxus is the sister genus of Pseudotaxus, which is well-known for its capability of producing the anti-cancer active ingredient Taxol and has been extensively studied in recent years26,39. The natural populations of P. chienii are relatively dispersed throughout China, exhibiting reproductive isolation among them. In our previous study, we reported the presence of 10-deacetylbaccatin III and paclitaxel in P. chienii samples collected from a wild population located in Mount Tianmu (30.33° N/119.42° E, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China)40. However, paclitaxel was not detected in P. chienii samples reported in the present study, which were collected from a wild population located in Nanjianyan Scenic Resort (28.36° N/119.09° E, Lishui, Zhejiang, China). We speculated that we might have mistakenly collected some Taxus specimens and considered them as P. chienii due to the lacking of experience in distinguishing Taxus and Pseudotaxus for our previous study40. Phenotypes of Taxus and Pseudotaxus are highly similar. It’s critical to sample the plant materials in the fall when the colors of the fruits are developed, which are the critical character to distinguish Taxus and Pseudotaxus. Since the plant materials used for the current study coming from different batch of sampling, we are confident that the spatial distribution of various types of active compounds reported in the current study is reliable (Fig. 1).

Although the complete genomes of various Taxaceae plants are publicly available, the reason why Taxol is synthesized exclusively in Taxus species remains unclear22,23,24. Our study presents the complete genome of P. chienii (Fig. 2a, b), a relict conifer endemic to China that belongs to a monotypic genus closely related to Taxus41. The genome size of P. chienii (2n) is approximately 15.6 Gb, which is larger than the known genomes of Taxus species, such as T. mairei (10.2 Gb), T. wallichiana (10.9 Gb), and T. yunnanensis (10.7 Gb)22,23,24. WGD is a dramatic genomic event that supplies a source of genetic material, thereby increasing both the complexity and size of the genome in angiosperms42. However, the occurrence of WGD events in gymnosperms has been a subject of controversy43. Previous studies have reported that a recent WGD event has happened during the evolution of T. mairei, whereas no obvious WGD was observed for T. wallichiana22,23. Our data also indicated the absence of a recent WGD event in the P. chienii genome (Supplementary Fig. 5c), suggesting that the complexity of WGD within gymnosperms, particularly within the Taxaceae family, is noteworthy44. Most of the LTR-RT expansions in the Taxus genomes happened between 24 to 8 MYA22; however, the expansion in the P. chienii genome experienced an exceptionally long duration, ranging from approximately 60 to 10 MYA (Fig. 2c, d). Continuous insertions of LTR-RTs have enlarged the size of P. chienii genome45.

The origin and evolution of the taxane biosynthesis pathway have consistently been a focal point in plant secondary metabolism46. Previous research pointed out that the loss of essential gene families, particularly the orthologues of TS, results in the absence of Taxol and its analogs in T. grandis25. Evolutionary analysis suggests that T. grandis is the oldest plant in the Taxaceae family, based on five selected species with complete genomes (Fig. 2f). Following the emergence of the Taxaceae family, P. chienii has evolved TPS with taxadiene synthase activity and diverged from T. grandis approximately 48.3 MYA. Although P. chienii has entered the initial stages of taxane biosynthesis, it possesses only a partial pathway for Taxol biosynthesis, which terminates before the production of the enzyme responsible for synthesizing 10-deacetylbaccatin III, known as TBT47. Approximately 24.3–25.6 MYA, the evolution of the Taxus genus formed an independent branch, diverging from the Pseudotaxus lineage (Fig. 2f). With the formation of the Taxus genus, the limitation caused by the absence of TBT was addressed, leading to the extension of the existing taxane biosynthesis pathway in P. chienii and resulting in a complete Taxol biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 3).

In P. chienii, the incomplete Taxol biosynthetic pathway results in the accumulation of an acetylated taxane, taxusin (Fig. 4a, b), which exhibits minimal anti-tumor activity48. Taxol contains only two acetylated sites (C4 and C10), whereas taxusin contains four acetylated sites (C5, C9, C10, and C13)49. Previous study has demonstrated that taxusin can be efficiently deacetylated by treatment with K2CO3 in THF/MeOH at 0 °C for 3 days33. Consequently, taxusin was selected as an industrial substrate for the production of taxoids due to its high natural abundance in yew heartwoods50. Our study showed that P. chienii contains a large amount of taxusin and is a good raw material for industrial production of Taxol (Fig. 4e, f). Undoubtedly, P. chienii has both ecological and medicinal value.

In Taxus plants, taxane biosynthetic genes are arranged in one or two gene clusters, which is also observed in P. chienii22,23,24. Taking T. wallichiana as an example, several taxane biosynthesis-related gene clusters were located in Chr10, which expanded on this chromosome through tandem duplication23. We verified genomic rearrangements between the Chr9/11 of P. chienii and the Chr10 of T. wallichiana (Fig. 3). These results confirm a common origin between the taxane biosynthetic pathway of P. chienii and the Taxol biosynthetic pathway of T. wallichiana.

Investigating terpene synthases, which catalyze isoprenoid cyclization reactions, offers valuable insights into the evolution of plant-specific terpenoid biosynthesis in terrestrial plants34. Diterpenoid biosynthesis can be initiated by three distinct enzymes: Class I TPSs, Class II TPSs, and bifunctional Class I/Class II TPSs, all utilizing GGPP as a precursor51. Bifunctional TPSs have been identified in gymnosperms and lycophytes, such as Abies grandis, Abies balsamea, Ginkgo biloba, and Selaginella involvens15. The initial committed step in taxane biosynthesis involves the cyclization of linear GGPP to form taxa-4(5),11(12)diene, catalyzed by TS52. A previous study has indicated that the TS protein in T. brevifolia is a Class I TPS51. The classification of TPS proteins is primarily based on the presence or absence of two motifs: DXDD and DDXXD/E. It is noteworthy that the known TSs from the Taxaceae plants, which lack the classic “DDXD” motif, are classified as Class I TPSs rather than bifunctional TPSs, indicating a distinctive characteristic of the Taxaceae family within gymnosperms (Fig. 5a). Comprehensive sequence analysis showed that the protein sequence surrounding the core DXDD motif, which is the iconic sequence of Class II TPSs, has a high similarity between TPSs from Taxaceae and other gymnosperms, indicating its conserved role during the evolution process. In the future, this peculiar phenomenon needs further attention of researchers.

X-ray crystal structure analysis showed that a TS protein from T. brevifolia possesses a complete class I-type C-terminal domain and a vestigial class II-type N-terminal domain, suggesting it activates the isoprenoid substrate by ionization, rather than protonation35. Using the 3p5p.1.A model as a template, the structure of PcTS1 is closer to the Class I type TPSs than to the bifunctional TPSs present in gymnosperms, indicating that it may be an evolutionary transitional form. Previous studies uncovered the function of the DDXXD and (N,D)DXX(S,T)XXXE motifs as metal-binding sites in class I-type terpenoid cyclase35,53. In PcTS1, the residues D668 and D669 of the “DDXXD” motif, along with N812, D813, and E820 of the (N,D)DXX(S,T)XXXE motif, are predicted to be located the divalent cation binding site (Fig. 5b, c). This observation suggests that the structure of the metal ion catalysis site is conserved among TS enzymes across the Pseudotaxus and Taxus genera52. Heterologous expression of PcTS1 produced taxadiene in tobacco, confirming its complete functionality as TS (Fig. 5e–g).

In Taxus plants, several CYP725 subfamily genes were identified to be candidates for Taxol biosynthesis22. Comparative genomic analysis showed that CYP725 is a gymnosperm-specific CYP subfamily, indicating its specialized functions in the secondary metabolism of gymnosperm54. In plants, many members of the CYP family showed high inducibility in response to MeJA55. In Taxus cell suspension cultures, MeJA elicitation is an effective strategy to induce and enhance biosynthesis of Taxol56. RNA-seq analysis demonstrated that MeJA treatment significantly up-regulated the expression of CYP725 genes, implying a potential coordinated regulatory pattern in their expression. Gene expression is regulated by various cis-acting elements, and the distribution of these elements within the plant genome is uneven. Consequently, genes that are clustered together may be influenced by the same regulatory elements and display similar expression patterns. Most of the CYP725 genes are situated within a very restricted genomic region (Fig. 6), which may account for the consistent response of CYP725 to MeJA treatment. In Taxus, several TFs belonging to the MYB, bHLH, and WRKY families were identified as regulators involved in the regulation of Taxol biosynthesis57,58. Co-expression analysis identified a number of MeJA responsive TFs, such as MYB12, MYB13, bHLH18, and WRKY6, providing a valuable resource outlining the regulation of taxane biosynthesis.

In conclusion, analysis of the high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of P. chienii presented here reveals insights into the origin and evolution of taxane biosynthesis in the Taxaceae family. P. chienii, belonging to an older genus than Taxus, possesses only a partial pathway for Taxol biosynthesis, as it lacks a key enzyme known as TBT. This deficiency results in the accumulation of taxusin, a highly acetylated form of taxane. With the emergence of the Taxus genus, the limitations imposed by the absence of this transferase have been overcome, resulting in a complete biosynthetic pathway for Taxol. Protein structure analysis showed that the metal ion catalysis sites, TS, are conserved across both the Pseudotaxus and Taxus genera.

Methods

Plant material

The tissues of Pseudotaxus chienii (specimen ID: ZQBX) were collected from the Nan Jian Yan Scenic Area (28.0°20.0’39.19”N, 119.0°6.0'0.97”E, Altitude:1197 m) in Zhejiang Province, China, in November 2022, for genome sequencing. The distinguishing feature of P. chienii is the presence of a white aril and two distinct white stomatal bands on the underside of mature leaves.

MS imaging (MSI) analysis

Young leaves and stems of P. chienii were sheared into 20-μm sections on the MALDI-2 conductive slide using a freezing microtome (Leica CM1950). The sections were vacuum dried with N2 gas. The tissue sections were dried and kept in − 80 °C for long-term preservation after vacuum packaging. The MALDI-2 special matrix containing 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid and 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone was purchased from Bruker company. Prior to MS analysis, a MALDI-2 special matrix was sprayed onto the slides using a TM-sprayer (HTX Technologies) with the default parameters. No signa of the matrix background was detected. The size of MALDI-2 chip is 2.5 ⅹ 7.5 cm. We placed the leaf and stem materials on the same chip to ensure comparability between them.

Compounds in the slides were visualized using a timsTOF fleX MALDI2 (Bruker) equipped with a smartbeam 3D laser operating at 10 kHz. MSI was conducted in both of positive and negative ion modes across a m/z range of 50–1500. The spatial resolution of MSI was set to 20 μm, and the laser frequency was adjusted to 10 Hz. MS imaging data were firstly normalized using the Root Mean Square method and processed with SCiLS Lab software (ver. 2021c, Bruker, Billerica, USA). Metabolites were identified by comparing the measured m/z values (with an accuracy of < 0.006 Da) against an in-house standard database and the Bruker Library MS-Metabobase 3.0 database. Receiver Operation Characteristic analysis and Student’s t test analysis were applied to determine the significance of differences between the samples. Corrected p-value < 0.01 were used to screen significant changed metabolites.

Genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from the twigs of P. chienii using the classical cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide method. After quality checking, the genome was surveyed through the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform using a paired-end library (read length of 150 bp, insert size of 350 bp).

A HiFi SMRTbell library was constructed using the SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences of California) and sequenced on the PacBio Revio sequencing platform at Wuhan Benagen Tech Solutions Company Limited (Wuhan, China). The consensus HiFi reads were generated using circular consensus sequencing software (ver.6.4.0) with default parameters. The Hi-C library was prepared using fresh twigs of P. chienii. Briefly, the tissues of P. chienii were fixed with a 2% formaldehyde. Nuclei were extracted and then digested by the restriction enzyme DPN II. The end of digested fragments was labeled with biotin and ligated randomly with T4 DNA ligase (NEB) and reverse crosslinked using proteinase K (NEB). Then, DNA fragments were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Genome assembly

The raw data of short reads was filtered to remove adapters and low-quality reads using fastp software (ver. 0.21.0)59. The genome size and heterozygosity were estimated using Jellyfish v2.2.10 and GCE (ver.1.0.0) with the K-mer method60. The Hifi sequences were first assembled into contigs using hifiasm (ver. 0.16.1)61, followed by two rounds of polishing using Pilon with short reads62. Purge_dups (ver. 1.2.5) was used to eliminated redundant Haplotigs63. For pseudochromosome level scaffolding, clean reads of the Hi-C data were aligned to the pre-assembled genome using the HICUP software (ver. 0.8.0) to obtain unique mapped paried reads64. The preliminary assembly of the draft genome sequence was anchored onto chromosomes using ALLHIC (ver. 0.9.8)65. Finally, a chromosome-level assembly of P. chienii was obtained through manual curation using Juicebox (ver. 1.11.08)66. To estimate the assembly completeness, clean Illumina reads were mapped onto the reference sequence using the BWA software (ver. 0.7.17)67. BUSCO program (ver. 4.1.2) was used to evaluate the integrity of genome assembly based on lineage-specific profile library embryophyta_odb10.2024-01-0868.

Gene prediction and annotation

The gene structure of the P. chienii genome was predicted using three strategies, including transcript mapping, ab initio gene prediction, and homologous gene alignment69. For transcriptome-based prediction, full-length cDNA transcripts were first aligned to the reference sequence using Minimap2 (ver. 2.17) assembled with Stringtie2 (ver. 2.1.5)70,71, and gene models were then predicted using TransDecoder (ver. 5.7.0) (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). For homology-based gene prediction, peptide sequences from T. wallichiana, T. yunnanensis, T. mairei, and T. grandis were aligned to the P. chienii genome using tblasn (ver. 2.13.0) and gene models were predicted using Exonerate (ver. 2.4.0)72. For ab initio prediction, Augustus and GlimmerHMM were used with a custom training set from transcriptome and protein-based gene model73,74. At last, all the results from the above three distinct methods were combined and integrated to produce a high-confidence gene structure by Maker (ver. 2.31.10)75.

For functional annotation, the protein encoding sequences of P. chienii were searched against several protein databases, including NR (ver. 2022-03-09), UniProt and TrEMBL (ver. 2022-03-09), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) using the BLASTp program. The Pfam domain and Gene Ontology (GO) classification was performed using InterProScan (ver. 5.55-88.0)76.

Prediction of repeat sequence

To identify repeat sequences in the P. chienii genome, we first generated a de novo repeat sequence library using RepeatModeler (ver. 2.0.4)77. LTR elements were identified using LTR_FINDER and LTRharvest (ver. 1.6.0)78,79. The above two libraries were then combined with the Repbase library and used as the input data for RepeatMasker (ver. 2.0.4, https://www.repeatmasker.org/). The TE Protein type repeat sequences were predicted using RepeatProteinMask (ver. 4.1.5) in the RepeatMasker software. Tandem repeat prediction was performed using the software Look4TRs80. To calculate the insertion time (T) of LTRs, the following formula was used:

where the r for gymnosperm is 2.2 × 10−9 substitutions per year per synonymous site and the K value was calculated using Distmat from the EMBOSS (ver. 6.5.7.0) package81. The LTR Assembly Index was calculated using LTR_retriever (ver. 2.9.0)30.

Synteny and whole-genome duplication analysis

To investigate genome collinearity, syntenic gene pairs between P. chienii, T. yunnanensis, T. wallichiana, T. mairei, and T. grandis were identified using JCVI (ver. 0.84) with default parameters82. For whole-genome duplication analysis, an all-versus-all analysis with BLASTp was performed using all proteins sequences of P. chienii with an e-value cutoff of 10−5, query coverage of 0.3, and an alignment threshold of 100 amino acids. The syntenic regions with collinearity of paralog pairs were detected by MCScan X with default parameters83. Nucleotide substitutions (Ks) value of each syntenic gene pair was calculated using the PAML program (ver. 4.9 package)84.

Phylogenetic analysis and genomic comparison

The longest transcripts of each coding gene from 15 representative species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, Vitis vinifera, Oryza sativa, Nymphaea colorata, Amborella trichopoda, Taxus yunnanensis, Taxus wallichiana, Taxus mairei, Torreya grandis, Fokienia hodginsii, Gnetum montanum, Pinus densiflora, Ginkgo biloba, Cycas panzhihuaensis, Selaginella moellendorffii, and P. chienii were used to construct gene families using the program OrthoFinder (ver. 2.09)85. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using IQ-TREE (ver. 2.1.3) with the best model selected by ModelFinder86. The resultant phylogenetic tree was applied to calculate the divergence time by the MCMCTREE program from the PAML (ver. 4.9 package)84. Divergence times between O. sativa and G. biloba (326.4 - 336.8 million years ago [Mya]), G. montanum and C. panzhihuaensis (275.3–316.4 Mya), and A. trichopoda and N. colorata (179.9– 205.0 Mya) were collected from Timetree (http://timetree.org/) for use as fossil calibration points. The expansion and contraction of gene families were identified using CAFE (ver. 4.2.1)87.

Untargeted metabolomic profiling

The stem and leaf samples of different Taxaceae trees, including P. chienii, T. wallichiana, and T. grandis (50 mg each sample, N = 6), were ground with 800 μL pre-cooled methanol solution (50%) in a tube. The tissue samples were added with 500 μL of pre-cold chloroform/methanol/H2O (v:v:v, 1:3:1) and subjected to ultrasonication for 5 min at 4 °C. The chromatographic separation of the tissue sample was carried out using a SCIEX UPLC system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) with an ACQUITY BEH Amide column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size; Waters, Milford, USA). The flow rate in the column was 0.4 mL/min, and the working temperature was 35 °C88.

An efficient MS/MS SCIEX Triple-TOF-5600 plus system (Applied Biosystems) was used to detect metabolites eluted by the reversed-phase separation. The MS data pretreatments, such as peak picking, peak grouping, retention time (RT) correction, and adduct annotation, were conducted using XCMS software. The MS data was converted into an mz.XML format file and identified by checking the RT and m/z values. The metabolite was annotated by matching the exact m/z value of each MS ion to the KEGG database. The molecular formula of each presumptive compound was validated by the isotopic distribution according to an in-house MS library. The intensity of each ion peak was calculated by software metaX. The Wilcoxon test was conducted to analyze the metabolic differences between the two sample groups. The P value was adjusted and corrected by false discovery rate (FDR) with the Benjamini–Hochberg method. A VIP cut-off value of 1.0 was used to select important features.

Identification of taxane biosynthesis-related genes

The full sequences of taxane biosynthesis-related proteins were downloaded from the published Taxus genomes and used as baits to search against the P. chienii genome22,23,24. Homologous genes in P. chienii were obtained by using OrthoFinder ver.2.09 with default parameters85. Furthermore, important gene classes, including the CYP (Pfam ID: PF00067), TRF (Pfam ID: PF02458), and TPS (Pfam ID: PF03936 and PF00432) families, were identified by performing HMM searches. To identify the gene with a complete function domain, a gene body containing a continuous long gag (N > 10) in the multiple sequence alignment was removed. Multiple sequence alignment analysis was performed using the ClustalOmega program (http://www.clustal.org/).

Homology modeling of TPS family members

The 3D models of TPS proteins were built using the SWISS-MODEL program (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/). The protein 3D structures were predicted based on the published crystal structure of T. brevifolia TS protein (PDB ID: 3p5p.1, resolution: 2.25 Å)35. For each TPS family member, the sequence alignments between template and target sequences were performed by Clustal Omega (http://www.clustal.org/). The model with the lowest overall energy was selected as the final structure of the target protein. The PBD files of selected TPS proteins were generated and download from the SWISS-MODEL program. TM score was analyzed using the alphafold3 online tool with referring PBD file.

MeJA treatment and RNA-seq analysis

P. chienii cutting seedings were used for MeJA treatment and RNA-seq analysis. For MeJA treatment, 100 μM MeJA ethanol solution was sprayed onto the leaves of P. chienii seedings and inoculated for 24 h and 48 h, respectively. Leaves inoculated with ethanol were harvested as the controls. RNA extraction, cDNA library construction, Illumina sequencing, sequence alignment, and quality evaluation were performed. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed using the DESeq2 program according to criteria: the FDR < 0.05 and absolute fold change ≥ 289.

Promoter analysis

The 1500-bp promoters of 581 CYP superfamily genes and 16 taxane biosynthesis pathway genes were extracted from the P. chienii genome. The promoter sequences were scanned using the PlantCARE software (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). Two MeJA-related cis-elements, including G-box (CACGTGG) and G-box like (AACGTG), and four TF binding elements, including ABRE (ACGTG), G-box (CACGAC and TAACACGTAG), MBE (CAACTG and CAACCA), W-box (TTGACC), were screened and visualized by TBtools90.

Transient expression in N. benthamiana and substrate feeding experiments

The full-length sequences of T2OH (PchiChr11G298480.1) and T7OH (PchiChr11G298490.1) from P. chienii, and T2OH (ctg2120_gene.6) and T7OH (ctg2120_gene.1) from T. mairei were cloned into pBWA(V)HS vectors and transferred into Agrobacterium (strain GV3101). Agrobacterium strains containing the gene constructs were grown in 10 mL of LB with antibiotics (50 mg/L kanamycin and 25 mg/L rifampicillin) for 16 h at 28 °C and 200 rpm, then the cells were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed. After incubation at room temperature for 2 h, infiltration was performed using a 1 mL syringe without needle on underside side of 4- week-old N. benthamiana leaves. After 4 days, 100 μg/mL taxusin was infiltrated into the underside side of previously Agrobacterium-infiltrated leaves with a needleless 1 mL syringe. Leaves were collected after 1 day post-infiltration, extracted and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

LC-MS/MS analysis of taxusin content

The twig samples are harvested from P. chienii cuttings and ground with liquid nitrogen. The sample power was added with 800 μL of extract solution containing zirconia beads. Then, the sample solution was sonicated in ice for 25 min and kept in a constant temperature extract solution for 1 h. The entire supernatant was precisely transferred to a new clean microtube and vacuum dried.

Taxusin standard (CAS: 19605-80-2, ≥ 99.0%) was purchased from Shyuanye company (https://www.shyuanye.com/). An appropriate amount of standard solution was used to prepare a gradient calibration curve working solution. The parameters of LC-MS/MS analysis are as follows. Column: ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm); Mobile phase: 0.1% formic acid water solution (A solution) and methanol solution (B solution); Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min; Injection volume: 10 μL; Column temperature: 30 °C; Ion source: ESI; Ion scanning mode: multiple reaction monitoring; Ion source temperature: 500 °C; Ion source voltage: 4500 V; Collision gas: medium; Air curtain pressure: 35 psi; and atomizing gas and auxiliary gas: 50/55 psi. Multiquant 3.0.2 software was used to extract chromatographic peak area and RT. The standard of the target compound was used to correct the RT. The retention time of taxusin is 7.48 min. The transition of m/z 527.3 → 467.2 was used for taxusin quantification, and the transitions of m/z 527.3 → 407.2 were utilized for confirmation. Limit of detection is 2 ng/mL.

Experimental validation of PcTS genes

Total RNA was isolated from the twigs of P. chienii using an RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). High-quality RNA was used for cDNA library construction using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit. ORF of TS1 (PchiChr11G299420.1) was amplified with Biorun Pfu PCR Mix (Up-cagtGGTCTCacaacatggctcagccctcatttaattcagctc/ cagtGGTCTCatacatcatactttaattggttcaatataaacttttcttatataat-Down) and ligated into pBWA(V)HS vector (Biorun Bio-tech, https://plant.biorun.com/). Purified construct was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells (GV3101) using Eppendorf Eporator (Hamburg, Germany). After preparing a resuspension of A. tumefaciens with OD600 = 0.2, the tobacco leaves were inoculated with the resuspension for 10 min91.

GC-MS analysis of taxadiene

For GC-MS analysis, 500 mg of transgenic tobacco leaves were harvested and ground to powder in liquid N2. The powder was extracted with 5 mL hexane for 20 min sonication treatment. Tissue samples were extracted with mixed solution (hexane:ethyl acetate = 4:1, v/v) containing 200 ng of internal standard (eicosane, CAS: 112-95-8). After dried under a stream of N2 gas, the samples were redissolved in 1 mL of hexane: ethyl acetate (4:1, v/v) mixed solution. Then, 1 μL of each sample solution was injected into a Trace GC Ultra gas chromatograph coupled to an ISQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Separation was performed with an HP5ms column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) in splitless mode92. Taxadiene was detected according to the peak area of the internal standard. All analyses were conducted using three biologically independent samples.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Genome assembly has been deposited in GenBank under accession GCA_053640655.1 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_053640655.1]. The genomic raw sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under accession PRJNA1205499. The transcriptomic raw sequencing data generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession GSE288094. Genome annotation files are available at Figshare [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29084240]. The raw data of MS imaging analysis has been uploaded to the Metaspace database with project ID m-2025 [https://metaspace2020.org/api_auth/review?prj=07a71fa8-5c9a-11f0-a049-b3ec65131efb&token=KzN_YV6IGpbf]. Source data are provided in this paper.

Code availability

Codes used to perform the analyses are available at Figshare [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29084240].

References

Dörken, V. M., Nimsch, H. & Rudall, P. J. Origin of the Taxaceae aril: evolutionary implications of seed-cone teratologies in Pseudotaxus chienii. Ann. Bot. 123, 133–143 (2019).

Yu, C. et al. Integrated mass spectrometry imaging and single-cell transcriptome atlas strategies provide novel insights into taxoid biosynthesis and transport in Taxus mairei stems. Plant J. 115, 1243–1260 (2023).

Sabzehzari, M., Zeinali, M. & Naghavi, M. R. Alternative sources and metabolic engineering of Taxol: Advances and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 43, 107569 (2020).

Yu, C. et al. Role of an endodermis-specific miR858b-MYB1L module in the regulation of Taxol biosynthesis in Taxus mairei. Plant J. 122, e70135 (2025).

Ghimire, B., Lee, C. & Heo, K. Leaf anatomy and its implications for phylogenetic relationships in Taxaceae s. l. J. Plant Res. 127, 373–388 (2014).

Liu, L., Wang, Z., Su, Y. & Wang, T. Population transcriptomic sequencing reveals allopatric divergence and local adaptation in Pseudotaxus chienii (Taxaceae). BMC Genomics 22, 388 (2021).

Kou, Y. et al. Evolutionary history of a relict conifer, Pseudotaxus chienii (Taxaceae), in south-east China during the late Neogene: old lineage, young populations. Ann. Bot. 125, 105–117 (2020).

Leslie, A. B. et al. Hemisphere-scale differences in conifer evolutionary dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16217–16221 (2012).

Bolte, C. E. & Eckert, A. J. Determining the when, where and how of conifer speciation: a challenge arising from the study ‘Evolutionary history of a relict conifer Pseudotaxus chienii’. Ann. Bot. 125, v–vii (2020).

Lange, B. M. & Conner, C. F. Taxanes and taxoids of the genus Taxus - A comprehensive inventory of chemical diversity. Phytochemistry 190, 112829 (2021).

Zerbe, P. & Bohlmann, J. Plant diterpene synthases: exploring modularity and metabolic diversity for bioengineering. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 419–428 (2015).

Tong, Y. et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into the precise product synthesis by a bifunctional miltiradiene synthase. Plant Biotechnol. J. 21, 165–175 (2023).

Keeling, C. I. et al. Identification and functional characterization of monofunctional ent-copalyl diphosphate and ent-kaurene synthases in white spruce reveal different patterns for diterpene synthase evolution for primary and secondary metabolism in gymnosperms. Plant Physiol. 152, 1197–1208 (2010).

Mafu, S., Hillwig, M. L. & Peters, R. J. A. novel labda-7,13e-dien-15-ol-producing bifunctional diterpene synthase from Selaginella moellendorffii. Chembiochem 12, 1984–1987 (2011).

Peters, R. J. et al. Abietadiene synthase from grand fir (Abies grandis): characterization and mechanism of action of the “pseudomature” recombinant enzyme. Biochemistry 39, 15592–15602 (2000).

Schepmann, H. G., Pang, J. & Matsuda, S. P. Cloning and characterization of Ginkgo biloba levopimaradiene synthase which catalyzes the first committed step in ginkgolide biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 392, 263–269 (2001).

He, S., Abdallah, I. I., van Merkerk, R. & Quax, W. J. Insights into taxadiene synthase catalysis and promiscuity facilitated by mutability landscape and molecular dynamics. Planta 259, 87 (2024).

Chau, M., Jennewein, S., Walker, K. & Croteau, R. Taxol biosynthesis: Molecular cloning and characterization of a cytochrome P450 taxoid 7 beta-hydroxylase. Chem Biol 11, 663–672 (2004).

Wani, M. C., Taylor, H. L., Wall, M. E., Coggon, P. & McPhail, A. T. Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 2325–2327 (1971).

Qiao, F. et al. De novo characterization of a Cephalotaxus hainanensis transcriptome and genes related to paclitaxel biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 9, e106900 (2014).

Kutlutürk, G. Z. et al. Analysis of anticancer taxanes in Turkish Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) genotypes using high-performance liquid chromatography. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 21, 367–375 (2024).

Xiong, X. et al. The Taxus genome provides insights into paclitaxel biosynthesis. Nat. Plants 7, 1026–1036 (2021).

Cheng, J. et al. Chromosome-level genome of Himalayan yew provides insights into the origin and evolution of the paclitaxel biosynthetic pathway. Mol. Plant 14, 1199–1209 (2021).

Song, C. et al. Taxus yunnanensis genome offers insights into gymnosperm phylogeny and taxol production. Commun. Biol. 4, 1203 (2021).

Lou, H. et al. The Torreya grandis genome illuminates the origin and evolution of gymnosperm-specific sciadonic acid biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37038-2 (2023).

Jiang, B. et al. Characterization and heterologous reconstitution of Taxus biosynthetic enzymes leading to baccatin III. Science 383, 622–629 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Synthetic biology identifies the minimal gene set required for paclitaxel biosynthesis in a plant chassis. Mol. Plant 16, 1951–1961 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Biosynthesis of the highly oxygenated tetracyclic core skeleton of Taxol. Nat. Commun. 15, 2339 (2024).

Li, C. et al. A cytochrome P450 enzyme catalyses oxetane ring formation in paclitaxel biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202407070 (2024).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126–e126 (2018).

Liu, J. C., De La Peña, R., Tocol, C. & Sattely, E. S. Reconstitution of early paclitaxel biosynthetic network. Nat. Commun. 15, 1419 (2024).

Walker, K. & Croteau, R. Taxol biosynthesis: molecular cloning of a benzoyl-CoA:taxane 2alpha-O-benzoyltransferase cDNA from taxus and functional expression in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13591–13596 (2000).

Li, H., Horiguchi, T., Croteau, R. & Williams, R. M. Studies on Taxol biosynthesis: preparation of taxadiene-diol- and triol-derivatives by deoxygenation of Taxusin. Tetrahedron 64, 6561–6567 (2008).

Pemberton, T. A. et al. Exploring the influence of domain architecture on the catalytic function of diterpene synthases. Biochemistry 56, 2010–2023 (2017).

Köksal, M., Jin, Y., Coates, R. M., Croteau, R. & Christianson, D. W. Taxadiene synthase structure and evolution of modular architecture in terpene biosynthesis. Nature 469, 116–120 (2011).

Zhan, X. et al. Mass spectrometry imaging and single-cell transcriptional profiling reveal the tissue-specific regulation of bioactive ingredient biosynthesis in Taxus leaves. Plant Commun. 4, 100630 (2023).

Shi, M. et al. Molecular regulation of the key specialized metabolism pathways in medicinal plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 66, 510–531 (2024).

Deng, Q., Su, Y. J. & Wang, T. Microsatellite loci for an old rare species, Pseudotaxus chienii, and transferability in Taxus wallichiana var. mairei (Taxaceae). Appl. Plant Sci. 1, https://doi.org/10.3732/apps.1200456 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. Correlation analysis of secondary metabolism and endophytic fungal assembles provide insights into screening efficient Taxol-related fungal elicitors. Plant Cell Environ. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.15422 (2025).

Yu, C. et al. Omic analysis of the endangered Taxaceae species Pseudotaxus chienii revealed the differences in taxol biosynthesis pathway between Pseudotaxus and Taxus yunnanensis trees. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 104 (2021).

Li, S., Wang, Z., Su, Y. & Wang, T. EST-SSR-based landscape genetics of Pseudotaxus chienii, a tertiary relict conifer endemic to China. Ecol. Evol. 11, 9498–9515 (2021).

Jiao, Y. et al. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature 473, 97–100 (2011).

Van de Peer, Y., Mizrachi, E. & Marchal, K. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 411–424 (2017).

Stull, G. W. et al. Gene duplications and phylogenomic conflict underlie major pulses of phenotypic evolution in gymnosperms. Nat. Plants 7, 1015–1025 (2021).

Zhao, M. & Ma, J. Co-evolution of plant LTR-retrotransposons and their host genomes. Protein Cell 4, 493–501 (2013).

Kui, L., Majeed, A. & Dong, Y. Reference-grade Taxus genome unleashes its pharmacological potential. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 10–12 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Construction of acetyl-CoA and DBAT hybrid metabolic pathway for acetylation of 10-deacetylbaccatin III to baccatin III. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11, 3322–3334 (2021).

Bai, J. et al. Taxoids and abietanes from callus cultures of Taxus cuspidata. J. Nat. Prod. 68, 497–501 (2005).

Horiguchi, T., Rithner, C. D., Croteau, R. & Williams, R. M. Studies on taxol biosynthesis. Preparation of taxa-4(20),11(12)-dien-5 alpha-acetoxy-10 beta-ol by deoxygenation of a taxadiene tetraacetate obtained from Japanese yew. J. Org. Chem. 67, 4901–4903 (2002).

Perez-Matas, E. et al. Exploring the interplay between metabolic pathways and taxane production in elicited Taxus baccata cell suspensions. Plants12, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12142696 (2023).

Hu, Z. et al. Recent progress and new perspectives for diterpenoid biosynthesis in medicinal plants. Med. Res. Rev. 41, 2971–2997 (2021).

Hezari, M., Lewis, N. G. & Croteau, R. Purification and characterization of taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene synthase from Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) that catalyzes the first committed step of taxol biosynthesis. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 322, 437–444 (1995).

Schrepfer, P. et al. Identification of amino acid networks governing catalysis in the closed complex of class I terpene synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E958–E967 (2016).

Liao, W. et al. Transcriptome assembly and systematic identification of novel cytochrome P450s in Taxus chinensis. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1468 (2017).

Du, Z. et al. Identification and functional characterization of three cytochrome P450 genes for the abietane diterpenoid biosynthesis in Isodon lophanthoides. Planta 257, 90 (2023).

Patil, R. A., Lenka, S. K., Normanly, J., Walker, E. L. & Roberts, S. C. Methyl jasmonate represses growth and affects cell cycle progression in cultured Taxus cells. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 1479–1492 (2014).

Yu, C. et al. Tissue-specific study across the stem of Taxus media identifies a phloem-specific TmMYB3 involved in the transcriptional regulation of paclitaxel biosynthesis. Plant J. 103, 95–110 (2020).

Zhan, X. et al. Single-cell ATAC sequencing illuminates the cis-regulatory differentiation of taxol biosynthesis between leaf mesophyll and leaf epidermal cells in Taxus mairei. Ind. Crop. Prod. 205, 117411 (2023).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Liu, B. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. Quant. Biol. 35, 62–67 (2013).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9, e112963 (2014).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898 (2020).

Wingett, S. et al. HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Res. 4, 1310 (2015).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Zhao, Q., Ming, R. & Tang, H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nat. Plants 5, 833–845 (2019).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js Provides a cloud-based visualization system for Hi-C data. Cell Syst. 6, 256–258.e251 (2018).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Leng, L. et al. Cepharanthine analogs mining and genomes of Stephania accelerate anti-coronavirus drug discovery. Nat. Commun. 15, 1537 (2024).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 20, 278 (2019).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Slater, G. S. C. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinform. 6, 31 (2005).

Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19, ii215–ii225 (2003).

Majoros, W. H., Pertea, M. & Salzberg, S. L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879 (2004).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinform. 12, 491 (2011).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinform. 9, 18 (2008).

Velasco, A. II, James, B. T., Wells, V. D. & Girgis, H. Z. Look4TRs: a de novo tool for detecting simple tandem repeats using self-supervised hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 36, 380–387 (2019).

Rice, P., Longden, I. & Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 16, 276–277 (2000).

Tang, H. et al. JCVI: A versatile toolkit for comparative genomics analysis. iMeta 3, e211 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49 (2012).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Han, M. V., Thomas, G. W., Lugo-Martinez, J. & Hahn, M. W. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1987–1997 (2013).

Yu, C. et al. Comparative metabolomics reveals the metabolic variations between two endangered Taxus species (T. fuana and T. yunnanensis) in the Himalayas. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 197 (2018).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 16, 1733–1742 (2023).

Sunilkumar, G., Vijayachandra, K. & Veluthambi, K. Preincubation of cut tobacco leaf explants promotes Agrobacterium-mediated transformation by increasing vir gene induction. Plant Sci. 141, 51–58 (1999).

Li, J. et al. Chloroplastic metabolic engineering coupled with isoprenoid pool enhancement for committed taxanes biosynthesis in Nicotiana benthamiana. Nat. Commun. 10, 4850 (2019.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271905 (C.J.S.) and 32270382 (C.N.Y.)), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY23C160001 (C.J.S.), LY18C050005 (C.J.S.), LY19C150005 (C.J.S.), and LY19C160001 (C.J.S.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.Y., C.J.S., and M.S.W. conceived and designed the study. R.Y.M., C.L.Y., and C.J.S. prepared the genome sequencing material. M.S.W., R.Y.M., Z.J.F., L.X.Z., and Y.B.Z. led the bioinformatics analyses. S.L.W. and H.Z.W. provided the Taxus and P. chienii materials. M.Y.Z., E.H.B., W.T.L., and Y.Z. performed the untargeted metabolome and RNA-seq analyses. R.Y.M., Y.Y.P., and H.J.M. cloned the PcTS1 and TwTS1 genes. M.S.W., S.G.F., X.X.Z., and C.J.S. developed the figures. M.S.W., R.Y.M., C.N.Y., C.L.Y., and C.J.S. interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. M.S.W., C.L.Y., and C.J.S. wrote the manuscript. M.S.W., S.L.W., H.Z.W., C.L.Y., and C.J.S. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article