Abstract

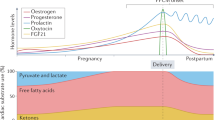

The peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase 2 (PTRH2, Bit-1, BIT1) gene plays a pro-survival role during development with loss of function gene mutations causing congenital infantile multisystem disease (IMNEPD). In wild-type female mice hearts, Ptrh2 protein levels significantly increase during pregnancy and decrease postpartum, demonstrating a protective role in response to pregnancy-initiated cardiac stresses. Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is due to dysregulated protective signaling in the pregnant heart. The genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying PPCM remain poorly defined with no specific therapies. Here, we engineered a cardiac-specific Ptrh2 knockout (Ptrh2-CKO) mouse and show these maternal mice develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction, exhibit high rates of postpartum heart failure, and model key features of human PPCM. Infusion of a caspase 3-specific inhibitor attenuated the PPCM phenotype. Collectively, our findings demonstrate Ptrh2 is a negative regulator of pregnancy-induced cardiac stresses by activating pro-survival signals and blocking apoptotic signals, suggesting Ptrh2 may be a therapeutic target for the treatment of PPCM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

PPCM is a life-threatening disease unique to pregnant women whereby left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure develop towards the end of pregnancy or within the first five months after delivery in women with no other identifiable cause of heart failure1. It varies in women of different ethnicities and geographic locations with the highest incidences occurring in Asia and Africa2,3,4,5,6. PPCM is a disease of unknown etiology, however, increasing evidence points to an underlying genetic component with 20% of PPCM patients having a loss-of-function or truncating mutations in sarcomere genes, including TITIN (TTN), BETA-MYOSIN HEAVY CHAIN (β-MHC; encoded by MYH7), cardiac troponin T (TTNT2), myosin binding protein C-3 (MYBPC3), and desmoplakin (DSP)7,8,9,10. Furthermore, PPCM may present with a co-occurrence of familial dilated cardiomyopathy (FDCM), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) or arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) revealing some genetic and phenotypic overlap11,12,13,14,15. Whether mutations in other genes predispose pregnant women to develop PPCM is not known; however, the majority of PPCM patients have no known gene mutations16 suggesting that genetic determinants of PPCM have yet to be identified. Currently, there are no reliable biomarkers or therapies for PPCM highlighting the medical need for identification of PPCM drug targets and candidate biomarkers.

How PPCM develops and which specific molecular pathways protect the maternal heart from peripartum stresses remain unclear. Accumulating evidence, primarily from mouse studies, suggests that PPCM occurs because of a dysregulated response to the extreme cardiac stresses associated with the late stages of pregnancy and delivery, all of which may induce molecular remodeling within the maternal heart to modulate stress-responsive genes leading to oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte cell death17,18,19,20. In pregnant hearts from wild type mice Pi3k/Akt activity increases in response to enhanced mechanical stresses on the heart and exposure to high estrogen levels, both of which relay a protective effect on the maternal heart21. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) is cardioprotective during pregnancy and the postpartum period21,22. Dysregulation of either Stat323, proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1α (PGC1-α)24,25, or Akt activity21 induces pathological responses to peripartum stresses by promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis and subsequent PPCM16,20. Taken together, PPCM progression occurs, in part, due to dysregulation of cardioprotective signaling pathways that protect the maternal heart from the extreme stresses of pregnancy. Identification of these cardiac stress regulators may facilitate the development of gene-based therapies for the treatment of PPCM.

Peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase 2 (PTRH2, Bit-1; BIT1) is a nuclear-encoded protein ubiquitously expressed in all tissue types26. It was initially identified as an integrin effector protein and a mediator of NFκB signaling27,28. PTRH2 is essential for skeletal muscle development and myogenic differentiation29. Patients with mutations in the catalytic domain of the PTRH2 gene develop congenital skeletal muscle myopathy30 and an infantile-onset multisystem disease characterized by intellectual disability, microcephaly, progressive ataxia, and muscle weakness (IMNEPD)31,32,33,34,35. The function of PTRH2 has not been studied in the normal or pathological heart. In this study, we demonstrate that PTRH2 protein levels are suppressed in pathological human PPCM hearts. In wild type mouse hearts, Ptrh2 protein levels significantly increase during pregnancy and decrease after delivery. By engineering a cardiac-specific Ptrh2 knockout (Ptrh2-CKO) mouse, we demonstrate that Ptrh2 suppresses pathological cardiac remodeling elicited by the extreme stresses of pregnancy. The protective effects of Ptrh2 on the maternal heart are confirmed in RNA-seq analysis of the Ptrh2-CKO postpartum hearts compared to age- and pregnancy matched controls. Our mechanistic investigations emphasize loss of Akt-Bcl-2 signaling and increased caspase 3 activation upon Ptrh2 deletion. This integrated approach enhances our understanding of gene changes that occur in PPCM and may lead to potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of PPCM and heart failure.

Results

PTRH2 mRNA and protein are decreased in PPCM patient hearts

PTRH2 functions as a pro-survival response to cell stress. PPCM is a pathological consequence to the increased cardiac mechanical stresses associated with the late stages of pregnancy and delivery. To determine if PTRH2 mRNA expression and protein levels were altered in PPCM patient hearts, we performed mRNA qPCR analysis (Fig. 1a), Western blotting and quantitation (Fig. 1d), and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 1f) of human left ventricle (LV) heart tissue from individual normal donor and PPCM patient hearts (Supplementary Fig. 1a). PTRH2 mRNA and protein were significantly reduced in PPCM patient hearts compared with normal donor hearts (Fig. 1a, d). mRNA analysis demonstrated hypertrophic markers Alpha Actin 1 (ACTA1) and MYH7 (encoding for β-MHC) mRNA expression were significantly increased in PPCM patient hearts (Fig. 1b, c) compared to controls. Consistently, PPCM patient hearts showed significantly decreased PTRH2 protein levels and increased hypertrophic and PPCM markers (Fig. 1d-e) ACTA1 (Fig. 1d) and β-MHC (Fig. 1e). Immunostaining confirmed PTRH2 protein levels were significantly reduced in patient PPCM LV samples compared with normal donor LV samples (Fig. 1f). Collectively, these findings identify PTRH2 mRNA and protein are downregulated in PPCM patient hearts, demonstrating a role for PTRH2 in regulating stresses within the pregnant heart and during postpartum period.

a–c PTRH2, ACTA1, and MYH7 mRNA quantitation from female normal donor and PPCM LV samples. Data shown is from biologically independent human samples/group. PTRH2 (n = 4; p = 0.001), ACTA1 (n = 5; p = 0.00073), and MYH7 (n = 5; p = 0.0198). d, e Immunoblot (left) and protein quantification (right) of PTRH2 (n = 5; p < 0.0001) and cardiomyopathy markers ACTA1(n = 5; p < 0.0001) and β-MHC (n = 5; p = 0.003) in normal donor and PPCM LV samples. Data shown is from biologically independent human LV samples/group. Statistical test (a–e) was by Two-tailed unpaired t-test. Error bars are mean + s.e.m. Each dot on graph represents an independent biological LV sample from either normal donor or PPCM. f Normal donor or PPCM LV sections immunostained for PTRH2. Scale bar, 50 μm. g Experimental workflow for RNA-seq on normal donor and PPCM LV heart samples. h Differential gene expression (DEG) from RNA-seq analysis of PPCM compared to normal donor LV heart samples. i Heat map of 50 DEGs (row normalized) in PPCM versus normal donor LV samples; increased (red), decreased (green), baseline value (black). j STRING network map of up- and down-regulated genes identified in PPCM/DCM, Cardiac Hypertrophy, PI3K/AKT and Integrin signaling pathways in PPCM LVs compared to normal donor LVs. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Schematic in g was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com). See Supplementary Fig. 1.

RNA-seq analysis of PPCM patient heart samples

We next performed deep sequencing RNA (RNA-seq) to investigate differential gene expression (DEGs) changes in PPCM patient hearts compared to normal donor hearts (Fig. 1g). RNA-seq analysis from normal donor and patient PPCM LV heart tissue was performed and we detected expression changes in 5,000 protein coding or multiple complex genes (Fold Change (FC)= > 1.5 and <−1.5; p < 0.05; 1,505 upregulated; 1724 downregulated; Fig. 1h, Supplementary Fig. 1b-h) including genes involved in PPCM and DCM such as TNNC1 (encodes for cardiac Troponin C), ACTA1 and TTN. Pathway score matrix analysis of the top 50 up- and down-regulated DEGs in normal donor versus PPCM patient hearts was visualized as a heat map (Fig. 1i). The heat map includes genes known to be upregulated in PPCM, including the genetic marker TTN and cardiomyopathy markers ACTA and TNNC1. Integrin, PI3K/AKT signaling and apoptosis genes were also dysregulated in PPCM hearts (Fig. 1i). STRING analysis of DEGs involved in signaling pathway interactions identified PPCM/DCM, cardiac hypertrophy, PI3K/AKT and integrin mediated signaling pathways in PPCM patient hearts compared to normal donor hearts (Fig. 1j). This analysis also connected PTRH2 with multiple genes involved in hypertrophy, DCM, and PPCM (CAST, TTN, MYH7, TNNT2, TNNC1; Fig. 1j).

Ptrh2 deletion in the heart recapitulates PPCM in mice

Because PTRH2 was significantly reduced in PPCM patient hearts, we examined Ptrh2 mRNA expression and protein levels before and during pregnancy in non-transgenic wild type mice and determined that Ptrh2 mRNA and protein levels significantly increased during pregnancy and decreased postpartum (Fig. 2a, b), demonstrating a functional role of Ptrh2 in the pregnant heart. To investigate whether loss of Ptrh2 expression, specifically in the heart, affected pregnancy-mediated cardiac stress responses, we generated cardiac specific Ptrh2 knock out (Ptrh2-CKO) mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a-d) by crossing our floxed Ptrh2 mice with the MyH6-cre (B6.FBN-Tg) mouse line in which the gene deletion occurs in cardiomyocytes after the initial stages of cardiac development are complete. The tissue-specific loss of Ptrh2 protein only in the hearts of Ptrh2-CKO mice was confirmed by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 2 b, c). We mated female mice and monitored pregnancy of Ptrh2-CKO mice. Age- and pregnancy-matched Ptrh2flox/flox non-transgenic (Ptrh2-flox(NT)) control mice were subjected to an identical mating and pregnancy regimen and served as controls. Ptrh2-CKO never pregnant (NP) mice lived to adulthood (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig 2d) with no abnormalities in heart structure or function under basal conditions. However, upon pregnancy, 90% of Ptrh2-CKO mice died during the end of their second pregnancy (Fig. 2d) between two to five days postpartum (Fig. 2e) with no maternal Ptrh2-CKO mice surviving four pregnancies (Fig. 2d). Ptrh2-CKO postpartum (PP) mice exhibited remarkably exacerbated cardiac dilation and dysfunction on echocardiography evaluation compared with age-and pregnancy-matched Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls (Fig. 2f). LV fractional shortening (LVFS) and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) were significantly decreased in Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice compared to postpartum control mice (Fig. 2g, h). LV internal diameter at end-diastole (LVIDd) and LV internal diameter at end systole (LVIDs) were significantly increased in Ptrh2-CKO _PP compared to Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls (Fig. 2i, j). EKG analysis indicated a dysregulated rhythm in Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice compared to controls (Fig. 2f; Supplementary Fig. 2f, g). Furthermore, Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice demonstrated significantly increased ratios of heart to body weight (HW/BW; Fig. 2k) and heart weight to tibia length (HW/TL; Fig. 2l) in addition to increased cardiomyocyte cross sectional area (Fig. 2m). While hearts from Ptrh2-CKO_NP mice were similar to never pregnant Ptrh2-flox(NT)_NP control hearts, all Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice demonstrated significant heart hypertrophy and increased cardiomyocyte size as identified by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-stained LV heart sections compared to Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls (Fig. 2n). Picrosirius red (PSR)-stained LV heart sections exhibited prominent interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice compared with Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls (Fig. 2n; Supplementary Fig. 2e). Hydroxyproline, a marker for Collagen 1 deposition and fibrosis significantly increased in the LVs from Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice (Fig. 2o) but not in Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls. Moreover, mRNA expression of fibrotic markers collagen III (Col3a1) and connective tissue growth factor (Ccn2) was significantly increased in the hearts of Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice compared with Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls (Fig. 2p, q). Taken together, only maternal Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice demonstrate hypertrophy of the heart, which progresses to dilated cardiomyopathy induced by pregnancy leading to heart failure and death. This pathological progression recapitulates PPCM in patient hearts that undergo pregnancy-induced hypertrophy progressing to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. These data demonstrate that Ptrh2 deletion in the heart sensitized the female mice to pregnancy-induced cardiac stresses, resulting in increased fibrosis, enlarged cardiomyocytes and development of PPCM and heart failure.

a Ptrh2 mRNA levels in wildtype Ptrh2flox/flox non-transgenic (Ptrh2-NT) control female mice (Never Pregnant vs. Pregnant; n = 4 biologically independent LV samples/group; p = 0.017 or Pregnant vs. PostPartum; n = 4 biologically independent LV samples/group; p < 0.0167). b Ptrh2 LV immunoblot from Ptrh2-NT control female mice; Never Pregnant, Pregnant and Post Partum. Quantification performed in triplicate normalized to Never Pregnant Gapdh levels. n = 4 biologically independent LV samples/group. Statistical test (a) Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. (b) Two-tailed unpaired t-test. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. c–e Survival curves (%; α-Mhc-Cre+/-, Ptrh2-NT, and Ptrh2-CKO) in (c) Never pregnant. n = 20 biologically independent mice/genotype/group), (d) Pregnant, or (e) Postpartum groups. d, e n = 60 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. f Echocardiography M-mode images and EKGs (inset) from Ptrh2-NT_NP versus Ptrh2-CKO_NP or Ptrh2-NT_PP versus Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice. g–j Echocardiography measurements: % LV Fractional Shortening (g; LVFS; p < 0.0001), Ejection Fraction (h; LVEF; p < 0.0001), Internal Diameter at End-Diastolic (i; LVIDd; p = 0.0236), and Internal Diameter at End-Systole (j; LVIDs; p = 0.0001) between Ptrh2-NT versus Ptrh2-CKO Never Pregnant or Postpartum groups. n = 8 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. k Heart/body weight (HW/BW; (p < 0.0001)) or (l) Heart weight/tibia length (HW/TL; p < 0.0001) ratios. n = 11 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. m Cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area. n = 3 biologically independent mice/group (p = 0.006). n Ptrh2-NT and Ptrh2-CKO NP (left) or PP (right) gross hearts (first row, scale bar, 5000 μm); H&E stained LV sections (second row: longitudinal; third row: cross-sectional, scale bar, 1000 μm; fourth row, scale bar, 50 μm), WGA (fifth row; scale bar, 100 μm), PSR (sixth row: interstitial; seventh row perivascular, scale bar, 50 μm), n = 3 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. o Hydroxyproline quantitation of Ptrh2-NT versus Ptrh2-CKO from NP or PP groups. n = 6 biologically independent mice/group, p < 0.0001. p–q LV mRNA expression of Col 3a1(p = 0.001) and CCN2 (p = 0.001) in Ptrh2-NT, Ptrh2-CKO NP and PP groups. n = 7 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. Statistical test (g–q) Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. Each dot represents an independent biological sample. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. See Supplementary Fig. 2.

RNA-seq differential gene response signatures of Ptrh2-CKO_PP hearts reveal a PPCM/DCM gene expression signature

mRNA analysis of Ptrh2-CKO and Ptrh2-flox (NT) controls in never pregnant and postpartum mice demonstrated a significant increase in the hypertrophic response genes Nppa and Nppb only in Ptrh2-CKO_PP female mice LV hearts compared to Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP control hearts (Fig. 3a, b). Importantly,

a–d mRNA expression of hypertrophic and cardiomyopathy marker genes (Nppa, Nppb, Acta1, and Myh7) in LV heart samples from Ptrh2-NT and Ptrh2-CKO NP and PP groups. a Nppa: n = 5 (p = 0.0339) biologically independent mice/genotype/group; b Nppb: n = 7 (p = 0.0037) biologically independent mice/genotype/group, (c) Acta 1: n = 5 (p = 0.0082) biologically independent mice/genotype/group and (d) Myh7: n = 7 (p = 0.0362) biologically independent mice/genotype/group. Statistical test (a–d) by Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison performed in triplicate. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. Immunoblot (left) and quantification (right) of Acta1(e; n = 3, p = 0.0163) and β-Mhc (f; encoded by the Myh7 gene; n = 5; p = 0.0158) in LV samples normalized to Gapdh from biologically independent mice/genotype/group. Statistical test (e, f) by Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison performed in triplicate. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. g Experimental workflow for RNA-seq of Postpartum LV heart samples (Ptrh2-NT versus Ptrh2-CKO). h DEGs from RNA-seq analysis of Postpartum LV heart samples (Ptrh2-NT versus Ptrh2-CKO). i KEGG pathway enrichment. j Heat map of 100 DEGs (row normalized); upregulation (orange); downregulation (blue); baseline value (white). k STRING network map of up- and down-regulated genes identified in PPCM/DCM, Cardiac Hypertrophy, Pi3k/Akt and integrin signaling pathways in Ptrh2-NT versus Ptrh2-CKO LVs. Source data provided as a Source Data file. Schematic in (g) was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com). See Supplementary Fig. 3.

mRNA transcript analysis for the cardiomyopathy and PPCM markers (Acta1, Myh7) also significantly increased only in Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal mice (Fig. 3c, d). Moreover, Western blotting of LV heart tissue from Ptrh2-CKO and Ptrh2-flox (NT) controls in never pregnant and postpartum mice for Acta1 and β-Mhc (encoded by the Myh7 gene) indicated a significant increase in protein levels only in Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal mice (Fig. 3e, f). We therefore examined whether a heart specific deletion of Ptrh2 induces a PPCM gene expression signature using RNA-seq analysis comparing LV hearts from Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls versus Ptrh2-CKO_PP female mice (Fig. 3g-j; Supplementary Fig. 3a-e). The most significantly affected genes identified in Gene Ontology pathways of the top 100 up- and down-regulated DEGs in Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP control versus Ptrh2-CKO_PP hearts were visualized as a heat map (Fig. 3j). The differential expression changes of coding and multiple genes were detected in 1135 genes (776 upregulated and 359 downregulated; p < 0.05; Fig. 3h Supplementary Fig. 3e). Genes known to be upregulated in PPCM (Myh7, Acta1) and hypertrophic response genes (Nppa and Nppb) were significantly increased in Ptrh2-CKO_PP LV hearts compared to Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls as shown in the heat map (Fig. 3j). The biomarker Nppa is upregulated in response to cardiac stresses including hypertrophy and heart failure. Indeed, mRNA expression of these hypertrophic response related genes was significantly upregulated only in the Ptrh2-CKO_PP group (Fig. 3i, Supplementary Fig. 3f-g). Protein-protein interactions from STRING database analysis demonstrated the most significantly affected pathways between PPCM, DCM, HCM, and diabetic cardiomyopathy (Fig. 3k); all of which have, in part, converging signals9,16. As identified in our analysis of patient PPCM hearts, protective stress response PI3K/AKT and integrin-mediated signaling pathways were among the most changed pathways (Fig. 3k). Analysis of the interaction network pathway generated for Ptrh2 to DEGs in the Ptrh2-CKO_PP vs. Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls showed Ptrh2 downregulation induced signaling pathways involved in cardiomyopathies, including PPCM, DCM, and HCM (Fig. 3k). These data robustly verify that Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice recapitulate the PPCM gene response signature.

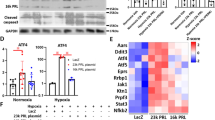

PTRH2 regulates cardioprotective signals in the heart during pregnancy

A cluster of Ptrh2 gene mutations or loss of the gene itself causes progressive congenital skeletal myopathy in humans and mice29,30. To investigate a cardioprotective role of Ptrh2 in pregnancy, we examined the effect of Ptrh2 on the cardioprotective Akt-Bcl-2 pathway before and after pregnancy. No difference in this pathway was detected in the hearts of Ptrh2-CKO_NP and Ptrh2-flox(NT)_NP controls (Fig. 4a). Importantly postpartum, Akt activity, as measured by phosphorylation at S473 and Bcl-2 protein levels were significantly decreased in Ptrh2-CKO_PP compared to Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP control hearts (Fig. 4b). Loss of cardioprotective signals, in response to cardiac stresses, during pregnancy leads to increased caspase 3 activity and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and subsequent PPCM17,20. We therefore examined whether loss of Ptrh2 in the heart during pregnancy increased caspase 3 activity and apoptosis. Cleaved caspase 3 levels in the hearts of Ptrh2-CKO_NP and Ptrh2-flox(NT)_NP controls were similar as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 4c). However, active caspase 3 levels were significantly increased only in the LVs from Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice (Fig. 4d). Double immunostaining for α-actinin, a cardiomyocyte marker, and TUNEL, which detects apoptotic cells, demonstrated that cardiomyocytes from Ptrh2-CKO_NP and Ptrh2-flox(NT)_NP controls had equivalent minimal apoptosis (Fig. 4eleft panel). However, Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal hearts showed significantly increased apoptosis compared to Ptrh2-flox(NT)_PP controls (Fig. 4eright panel). These data point to a cardioprotective role for Ptrh2 in the pregnant heart whereby loss of cardiac Ptrh2 significantly increases caspase 3 activity and apoptosis.

pAkt, Akt, and Bcl-2 immunoblots (left) and quantification (right; pAkt/Akt, p = 0.002; Bcl-2/Gapdh, p = 0.002) in LVs from Ptrh2-NT and Ptrh2-CKO mice in Never Pregnant (a) or Postpartum (b) groups normalized to Gapdh. n = 3–4 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. Caspase 3 immunoblot (left) and quantification (right; p = 0.019) in LVs from Ptrh2-NT and Ptrh2-CKO Never Pregnant (c) or PostPartum (d) groups normalized to Gapdh. n = 5 biologically independent mice/genotype/group. Statistical test (a–d) by Two-Tailed unpaired t-test in triplicate. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. e Representative LV samples co-stained with TUNEL (green color), DAPI (blue color) and α-actinin (red color) and quantified (right bar graph) from Ptrh2-NT and Ptrh2-CKO mice: Never Pregnant (left panels) or Postpartum (right panels). n = 3 biologically independent mice/genotype/ group with 9 fields/replicate (p < 0.0001). Statistical test by Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison performed in triplicate. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. f Experimental workflow of caspase 3 inhibitor experiments in Ptrh2-CKO mice. g Ptrh2-CKO survival curves (%) treated with caspase 3 inhibitor or its inactive control. n = 7 biologically independent mice/treatment group performed in triplicate. h H&E (scale bar, 1000 μm), WGA (scale bar, 50 μm) or PSR (scale bar, 50 μm) stained LV sections of Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO+Active inhibitor or Inactive inhibitor control. i HW/BW ratio from Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO mice+Active inhibitor or Inactive inhibitor (n = 7; p < 0.0001) from biologically independent mice/treatment group. j Cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (μm2) from Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO+Active inhibitor or Inactive control treated mice (n = 4; p < 0.0001) from biologically independent mice/treatment group with ≥300 cells/mouse. k Fibrotic area (%) from Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO+Active inhibitor or Inactive control (n = 4; p < 0.0001) from biologically independent mice/treatment group with 112-17 fields/mouse. Quantification of (l) TUNEL (%) positive cells (n = 5; p = 0.012) or (m) active caspase 3 (n = 3; p = 0.0004) relative to total nuclei in LV sections from Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO+Active inhibitor or Inactive inhibitor treated female mice from biologically independent mice/treatment group. Statistical test (i–m) by Two-tailed unpaired t-test in triplicate. Error bars are mean± s.e.m. Source data provided as a Source Data file. Schematic (f) created using BioRender (https://biorender.com). See Supplementary Fig. 4.

Infusion of a caspase 3 specific inhibitor during pregnancy ameliorates Ptrh2-CKO_PP-mediated PPCM

In several PPCM mouse models, caspase 3 activity is upregulated in the heart23,36. To test whether blocking the increased caspase 3 activity observed in the hearts of Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal mice would abrogate PPCM induced by loss of the Ptrh2 gene in these maternal hearts, Ptrh2-CKO pregnant mice were treated with a 11-day infusion of either the caspase 3 specific inhibitor (Z-DEVD-FMK) or its inactive control (Z-FA-FMK) beginning at day 10 of pregnancy (Fig. 4f). Indeed, all Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with the caspase 3 specific inhibitor survived pregnancy and the postpartum period (Fig. 4g), whereas 100% of Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with the inactive control died during pregnancy or shortly after delivery (Fig. 4g), which is what we consistently observed in untreated Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice (Fig. 2d). Echocardiography measurements from Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with the active caspase 3 inhibitor exhibited significantly reduced cardiac dysfunction compared with age- and pregnancy-matched Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with the inactive inhibitor control (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Notably, Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with the caspase 3 active inhibitor demonstrated a significant increase in percent fractional shortening (Supplementary Fig. 4b), an enlargement and dilation of the heart as identified by H&E-stained heart sections (Fig. 4h), a significant reduction in HW/BW (Fig. 4i), and significantly decreased cardiomyocyte cross sectional area (Fig. 4j) compared to age- and pregnancy-matched Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with inactive inhibitor control. Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with active caspase 3 inhibitor showed significantly decreased LV interstitial and perivascular fibrosis as indicated by PSR staining (Fig. 4h; Supplementary Fig. 4c) with significantly overall reduced fibrotic area (Fig. 4k) compared to Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with inactive inhibitor control. Apoptosis markers including active caspase 3 and TUNEL staining were markedly reduced in LVs of Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with active caspase 3 inhibitor compared with LVs from Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice treated with the inactive inhibitor control (Fig. 4l, m; Supplementary Fig. 4c). Taken together, chronic infusion of a caspase 3 specific inhibitor, beginning in early pregnancy, promoted survival of the Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal mice through the peripartum period and provided a significant rescue of heart function, suggesting that Ptrh2-mediated cardioprotection is, in part, dependent on abrogating apoptotic signals in the heart.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that PTRH2 is essential for cardioprotection from peripartum mechanical stresses that occur in the healthy pregnant heart. PTRH2 mRNA expression and protein levels are significantly decreased in PPCM patient hearts. Furthermore, in wild type mouse hearts Ptrh2 protein levels increase during pregnancy and subsequently decrease during the postpartum period, suggesting a compensatory role for Ptrh2 in response to the exaggerated cardiac mechanical stresses associated with pregnancy. Loss of Ptrh2 in the maternal Ptrh2-CKO_PP heart promotes enhanced susceptibility to pregnancy-mediated mechanical stresses that occur during hypertrophy and recapitulates human PPCM with heart failure. PTRH2 protein levels were significantly reduced in PPCM patient heart samples. Protein-protein interaction from STRING database analysis links PTRH2 to signaling networks that when dysregulated cause PPCM, DCM, and HCM.

Recently, loss-of-function mutations in the PTRH2 gene have been identified that cause congenital muscle myopathy and infantile onset multisystem disease (IMNEPD) pointing to an important function of the PTRH2 gene in human development and skeletal muscle differentiation29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Indeed, patients with a biallelic PTRH2 gene loss-of-function mutation present with minimal PTRH2 protein levels and reduced integrin-mediated signaling31. Published data on IMNEPD patients spans infants through adolescence with no reports on heart function31,32,33,34,35. Our RNA-seq analysis of patient hearts indicates the PTRH2 gene is dysregulated, and PTRH2 mRNA expression and protein levels are significantly reduced compared to normal donor hearts. A future area of investigation is to perform whole exome sequencing on PPCM patients to identify potential PTRH2 gene mutations involved in PPCM.

Because the heart requires activation of pro-survival pathways and suppression of apoptosis pathways to protect against the exacerbated mechanical stresses of pregnancy16,20, we developed a heart specific Ptrh2 knockout mouse. We found that PPCM is recapitulated in maternal Ptrh2 knockout mice as 90% of these mice die postpartum of the second pregnancy and 100% of these mice die by the fourth pregnancy between postpartum days two to five. These mice present with dramatically increased HW/TL and an enlarged heart with LV dilation as the pregnant heart progresses from the initial hypertrophy stage to end stage dilated cardiomyopathy and subsequent heart failure. RNA-seq analysis on Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal hearts identified differentially expressed genes in key pathways involved in PPCM as well as hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy compared to wild type age- and pregnancy-matched PP controls. Furthermore, integrin and pro-survival signaling was only decreased in Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal hearts. PTRH2 signals on an integrin mediated mechanical stress-response pathway27,28. Pregnancy promotes dramatic hemodynamic changes in the heart, including reduced resistance during systole and a 50% increase in cardiac output and blood volume37. The subsequent remodeling of cardiac tissue may activate stress response genes such as PTRH2 to function as negative regulators of PPCM and provide cardioprotective signals during the extreme mechanical stresses that occur in the later stages of pregnancy and during delivery. This is the first report of PTRH2 regulating cardioprotective signals in the maternal heart.

Two top pro-survival signaling pathways identified in RNA-seq analysis of PPCM patient hearts and our maternal Ptrh2-CKO mouse hearts were PI3K/AKT and integrin mediated signaling pathways. In a healthy heart during pregnancy PI3K/AKT activity is significantly increased in response to the extreme mechanical stresses within the heart, pointing to a cardioprotective role throughout pregnancy38. Maternal hearts isolated from Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice demonstrate significantly reduced Akt activity and Bcl-2 protein levels suggesting that Ptrh2, in part, regulates its cardioprotective function through activating a mechanical stress cardioprotective Akt/Bcl-2 pathway. PTRH2 is downstream of integrin adhesion, which relays signals to control mechanostress-induced apoptosis through up-regulation of a PI3K/AKT/NFκB pathway27. Integrin mediated survival signaling occurs in a variety of cell types, including endothelial cells where α5β1 or αvβ3 integrin adhesion to ECM activates a signal transduction pathway resulting in upregulation of the pro-survival protein Bcl-239. Indeed, PTRH2 was identified as a part of an integrin-Bcl-2 pro-survival adhesion pathway28, which may also be important in promoting endothelial survival under stress conditions. Moreover, our data demonstrates that in the stressed heart loss of PTRH2 increases fibrosis and ECM gene expression suggesting loss of integrin-mediated adhesion signaling induces changes in ECM composition including increased collagen deposition by cardiac fibroblasts. Targeting PTRH2 in cardiac fibroblasts may be a new way to control fibrosis in heart disease.

Increased apoptosis is a key parameter of PPCM17,25,36,40. Inhibiting apoptosis in the cardiac-specific PGC1-α null mice, which develop PPCM, promotes overall long-term survival of these maternal mice36. Recently, PPCM was induced in rats injected with β1-Adrenoceptor antibodies that specifically inhibit the PGC-1α pathway by significantly increasing both caspase 3 activity and the apoptosis rate of LV cardiomyocytes24,25. Increased release of a fragment of prolactin or dysregulation of Pgc1-α, Stat3, or Akt signaling all promote pathological responses to peripartum stresses by inducing caspase 3 activity and subsequent apoptosis in the heart23,36,38, which induces PPCM onset and progression to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Collectively, these findings point to caspase 3 activation as a potential hallmark of PPCM. Our data demonstrates caspase 3 activity and apoptosis are markedly increased only in maternal hearts of Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice. Therefore, we tested whether abrogating caspase 3 activity blocks PPCM in our Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice. Indeed, 100% of Ptrh2-CKO_PP mice, chronically administered a caspase 3 specific inhibitor, survived the postpartum period with a dramatic increase in heart function and significant decrease in cardiac enlargement, fibrosis and LV apoptosis, whereas Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal mice treated with an inactive inhibitor control died during the late stages of pregnancy or 2 days after delivery. Taken together, these findings point to a convergence of signaling pathways that lead to cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the development of PPCM. Blocking caspase 3 activity and subsequent apoptosis may be a key to treating PPCM.

Because pregnancy is a cardiac stress-associated condition, stress-protective heat shock proteins have been identified as potential modifiers of PPCM onset16,17. Under stress conditions, heat shock proteins are essential in maintaining cellular proteostasis, and an increase in the accumulation of misfolded proteins promotes cardiac toxicity and cardiomyocyte apoptosis that may lead to PPCM41. Mutations in the cardiomyopathy genes Bcl2-associated athanogene 1 and 3 (BAG1; BAG3) result in loss of cardioprotective signaling. These proteins act as a scaffold to link HSP 70 to small heat shock proteins and provide protection against mechanical stresses in the heart by regulating Bcl-2 levels41. Our RNA-seq analysis identified the Bag1 gene as downregulated in Ptrh2-CKO_PP maternal hearts in addition to PPCM inducing genes Ttn and and Myh7, thereby confirming PPCM pathways are activated upon loss of Ptrh2 in the maternal heart. We now add the PTRH2 gene as a stress-protective modulator in response to the high mechanical load placed on the pregnant heart.

There are several limitations to this study. The small sample size of the present RNA-seq analysis on normal donor and PPCM patient LV samples limited our ability to identify statistically significant DEGs. A larger sample size is needed for sufficient power to determine moderate genetic signature changes that occur in PPCM. In addition, access to external validation sets would enhance our findings but at this time none are available. To date, there are no public gene expression data sets available for PPCM, and we were unable to identify age-matched non pregnant or never pregnant patients presenting with non-PPCM induced DCM. Moreover, age- and ischemic time-matched donor and PPCM induced DCM heart samples are not available. In the future, we hope to develop large validation sets of PPCM and DCM patients for comparison.

The pregnant heart requires an enhanced protective response against mechanical-induced stresses throughout pregnancy, delivery and the initial postpartum period. In the healthy heart, PTRH2 may fulfill this role, in part, by responding to signals imparting increased pregnancy-associated cardiac stresses, including hypertrophy-mediated mechanical forces to negatively regulate PPCM. Upon the extreme mechanical stresses the heart experiences during pregnancy, PTRH2 activates a cardioprotective AKT-Bcl-2 pathway (Fig. 5). Loss of PTRH2 in the heart suppresses these cardioprotective signals and increases caspase 3 activity, leading to LV cardiomyocyte apoptosis and PPCM. Abrogating caspase 3 activity in the Ptrh2 null maternal mouse heart blocks PPCM progression to DCM and heart failure (Fig. 5), demonstrating that PTRH2 is cardioprotective by regulating apoptotic signals in the heart. Taken together, our data place the PTRH2 gene as a primary driver in maintaining cardioprotection in response to the mechanical stresses that occur in the pregnant heart.

The heart undergoes hypertrophy to account for the augmented mechanical load required during pregnancy to compensate for the increased blood flow to the fetus. This places extreme mechanical stresses on the heart. In the healthy heart such pregnancy associated stresses activate cardiomyocyte pro-survival pathways, including PTRH2. Upon the loss of PTRH2 expression, PTRH2-mediated cardio-protective signals are not activated, promoting increased caspase 3 activity and cardiomyocyte apoptosis that leads to PPCM progression to heart failure postpartum. Inhibiting caspase 3 blocks PPCM progression to heart failure. Schematic was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com).

Methods

This research only included the female gender because we were investigating the effects of pregnancy-induced stress on the maternal heart. This research complies with all the relevant ethical regulations. The biorepositories obtained informed consent from all donors and collected the samples, in accordance with ethical regulations. Biorepositories sent us only de-identified samples. The University of Hawaii and Tulane University Medical School IRB Committees approved the use of these human samples for the conduct of this study and waived the need for additional consent due to the samples being de-identified. Animal experiments were conducted in full compliance with the Tulane University Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee approval (IACUC; protocol #1776).

Human heart tissues

Normal donor (average age 55.6 years) and PPCM patient (average age 28.6 years) left ventricular tissue samples were procured from the biorepository at the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA, USA, supported by NIH grant U42OD11158), or Accio BiobankOnline.com (Tissue for Research). The ethnicity of samples was white and black participants. Informed consent was obtained from all donors by the biorepositories at the time of tissue collection, in accordance with ethical regulations.

Mouse studies

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animals were kept on normal chow, housed in a pathogen-free animal facility with a 14 h light cycle and 10 h dark cycle, and maintained at 72°F and 55% humidity. All animals were maintained according to current policies by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Ptrh2-floxed mice were made by Ozgene (Cambridge, MA) using molecular cloning and transfected into C57BL/6 ES cells42. The floxed mice were crossed to obtain Ptrh2 heterozygotes, which were backcrossed to wild-type BL/6 mice to obtain a pure Ptrh2+/- line. These mice were intercrossed to generate transgenic global Ptrh2 null mice42 on a C57BL/6 genetic background. To generate cardiomyocyte-specific Ptrh2 knockout mice (Ptrh2-CKO) we crossed Ptrh2 floxed mice with MyH6-Cre (B6.FVB-Tg; Jackson Labs, Portland, MA) transgenic mice that express Cre-recombinase only in cardiomyocytes starting at E8.5. Wild type mice harbor two copies of the floxed Ptrh2 allele without the αMHC-Cre+/0 transgene (Ptrh2-NT controls). Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation or by transcardial perfusion, following sedation using an avertin solution in line with local guidelines and approved protocols. All animal experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines.

Genotyping

Mouse tail tips were clipped and digested in STE buffer with Proteinase K (10 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, and 0.5 mg/ml Proteinase K) at 55 °C overnight. Genomic DNA was isolated and stored at −20 °C. PCR for genotyping was performed in a 15 μL reaction: 1 μL template DNA, 7.5 μL IBI Taq Keen Green 2X Master Mix (IBIRP004, IBI Scientific, Dubuque, IA, USA), 5.5 μL nuclease-free water, 1 μL 10 mM forward primer and 1 μL 10 mM reverse primer. PCR temperature and cycling conditions involved: 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 60 s in an Eppendorf Mastercycler epgradient (22331 Hamburg, AG 5341). A 2% agarose gel (SeaKem® LE Agarose, 50004 Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) was run to visualize DNA band sizes. The primer pair (G2F and G1R) sequences used to genotype the conditional cardiac-specific Ptrh2 knockout are provided in Supplementary Table 4. Electrophoresis gel was imaged and analyzed using a molecular imager (ChemiDoc™ XRS + System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Mating and pregnancies

Non-transgenic and transgenic C57BL/6 mice between 8 and 10 weeks old were used. While female mice were used for our experiments, we used male and female mice for mating. Age-matched littermates, one male per two female mice between 8-10 weeks old were paired for mating per cage. Separated cages of wild type (Ptrh2-flox) and knockout (Ptrh2-CKO) mice were arranged at the same time. Pregnant mice were transferred to new cages, allowed to give birth, and sacrificed at various days postpartum (PP). Age-matched Never Pregnant (NP) non-transgenic (NT) and transgenic (CKO) female mice were used as pre-pregnancy controls. The different groups studied are as follows: Ptrh2-flox_NP; Ptrh2-CKO_NP; Ptrh2-flox_PP; and Ptrh2-CKO_PP.

Mouse heart extraction

Never pregnant (NP) and Post-Partum (PP) female CKO mice and age-matched controls were weighed and anesthetized by injecting 0.4 mg/g body weight of avertin solution intraperitoneally using a 1 mL syringe/25 gauge. Mice were monitored for 5–10 min for an appropriate plane of anesthesia determined by observations of spontaneous respiration and pain reflexes (toe pinch). Loss of the toe pinch reflex indicated the presence of surgical anesthesia. After placing the animal in a supine position and using sterile instruments, the thoracic cavity was opened to expose the heart. Hearts were excised, weighed, and placed in 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for atria and blood removal. Left Ventricles were fixed for histological analyses or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further total protein extraction.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining

Excised mouse LVs and fresh human heart samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin as previously described43. Heart sections, cross and longitudinally cut at 5 μm, were deparaffinized in 3 washes of xylene, hydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and submerged in double-distilled water. Heart sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) following standard procedures. Cell structure was evaluated using a brightfield microscope.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Formalin-Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) human heart sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated as described above. Slides were subjected to antigen retrieval (10 mmol/L citrate buffer, pH 6.0) followed by 3% hydrogen peroxide incubation and blocking in 1.5% normal goat serum. Slides were then incubated with anti-PTRH2 primary antibody (HPA012897, Atlas Antibodies, Stockholm, Sweden) for 30 min, followed by incubation with biotinylated linking IgG secondary antibody for 20 min. Incubation with avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 20 min and 3,3’-diaminobenzidine substrate (SK-4100, Vector Laboratories) for 10 min was performed for protein detection and hematoxylin for nuclei counterstaining. Slides were visualized in a brightfield microscope and images processed in Fiji-ImageJ 1.53c software. The LV region used for histological staining corresponded to the LV papillary muscle intraventricular septum (IVS) region assessed by echocardiography.

Fibrosis

Mouse LV FFPE sections, transversely cut at 5 μm, were deparaffinized and hydrated as described above followed by a 10 min high-pressure antigen retrieval using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 at boiling temperature. Rehydrated paraffin sections were stained with picrosirius red (PSR) using a staining kit (24901-250, Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) to assess collagen deposition as an indicator of cardiac fibrosis. Mounted sections were visualized in a Zeiss microscope (AxioVision Rel.4.8). Left ventricular fibrosis was expressed as the percentage of PSR stain of the total area; at least 25 fields per group were evaluated. PSR images were processed using Fiji-ImageJ 1.53c software. For PSR quantification, ImageJ-FIJI software was used to quantify PSR images. Between 30-40 images were taken per sample and analyzed.

Hydroxyproline assay

Hearts from Never Pregnant and Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO female mice and age-matched non-transgenic (NT) controls were excised and LVs used to perform Hydroxyproline Assays following the manufacturer’s protocol (ab222941, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, 10 N NAOH was added to each sample and subjected to 1 h of hydrolysis at 120 °C, cooled on ice, and neutralized with 10 N HCL. Samples were centrifuged and supernatants collected into fresh tubes. Standard was prepared separately by diluting to 0.1 mg/ml. Both sample and standard were loaded in triplicate into wells and chloramine T reagent was added for 5 min. Liquid was evaporated by heating to 65 °C and oxidation reagent added to dissolve the crystalline residue. After 20 min incubation developer was added for 5 min, R.T. DMAB concentrate was then added to each well and incubated for 45 min at 65 °C. Samples were read on a microplate reader at 560 nm.

Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)

Rehydrated FFPE mice heart sections were stained with WGA fluorescein conjugate (W834, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to detect cardiomyocyte cross-sectional areas according to manufacturer’s instructions. Four, six-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-containing mounting medium (P36971, Invitrogen) was used as a nuclear counterstain. Mounted sections were visualized using a Zeiss microscope (AxioVision Rel.4.8) and areas of at least 100 LV cardiomyocytes from at least 3 mice per group were measured. WGA images were processed using Fiji-ImageJ 1.53c software.

Pump implantation and inhibitor chronic infusion

Before pregnancy, Ptrh2-CKO female mice were subjected to an echocardiogram to record heart function. At day 10 of pregnancy, mice received subcutaneous infusion of caspase 3 inhibitor (Z-DEVD-FMK; 550378, BD Pharmingen, Frankland Lakes, NJ, USA) or inactive inhibitor control (Z-FA-FMK; 550411, BD Pharmingen) at 142.86 µg/day, both released by ALZET® osmotic pumps at a delivery flow rate of 1.0 μL/h. The pumps were inserted subcutaneously on the dorsum of each mouse that had been anesthetized by inhalation of 2.5% isoflurane (Abbott AG, Baar, Switzerland). Active inhibitor and inactive control were prepared and sterilized by membrane filtration right before filling up the pumps. At day 17 of pregnancy a second echocardiogram was performed. Mice were sacrificed, and hearts removed for histological analysis at various time points.

TUNEL assay

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded sections on microscope slides were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and rinsed in distilled water. For immunofluorescence detection of apoptotic cells in the LVs, the TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (#A050, ABP-Biosciences, Beltsville, MD, USA.) was used following protocol directions. Briefly, slides were permeabilized with 1X proteinase K solution for 30 min at R.T. followed by two 1X PBS washes. DNase I solution was prepared as directed and each section treated for 30 min followed by one rinse with de-ionized water. Samples were then treated with TdT reaction cocktail, incubated for 3 hr at 37 °C in the dark, washed with 3% BSA buffer and treated with Andy Fluor 488-streptavidin staining solution for 1 h at R.T. in the dark. Sections were co-stained with α-actinin primary antibody (#PA5-21396; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) O.N. at 4 °C in the dark with rocking, washed with 1X PBS, treated with secondary antibody for 1 h at R.T. in the dark, stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI #P36971, Invitrogen). Slides were mounted with Dako fluorescence mounting medium (#s3023, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and visualized using a confocal microscope. The quantification of TUNEL-positive nuclei was performed by calculating the percentage of green FITC-labeled apoptotic nuclei relative to the total number of DAPI-stained nuclei within each field. Multiple non-overlapping fields (4–5 per section across 3–4 sections per heart) were analyzed per animal using ImageJ. TUNEL assay negative control: TdT enzyme was not added but α-Actinin primary and secondary antibodies were. Double negative control: Both the TdT enzyme and the α-Actinin primary antibody were not applied to the slide and only the secondary antibody was applied to sections on the slides.

3,3’diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining

The In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (MK500, Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) was used per company protocol. Briefly, labeling mixture was applied on each heart tissue section and slides were incubated for 90 min at 37 °C. Slides were washed with three times with 1X PBS for 5 min. Anti-FITC HRP conjugate was applied on each section and slides were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Slides were washed three times with 1X PBS for 5 min. Positive cells were visualized with the DAB substrate (SK-4100, Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA). Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin. After washing with running tap water, slides were dehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted in Acrytol (#13518, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) mounting medium and visualized in a brightfield microscope. Images were processed in Fiji-ImageJ 1.53c software.

Echocardiographic (EKG) measurements

In anesthetized (2–2.5% isoflurane) Never Pregnant and Postpartum Ptrh2-CKO female mice and age-matched non-transgenic (NT) controls, left ventricular function was assessed with trans-thoracic echocardiography (Vevo 2100, Visual Sonics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). LV parasternal short-axis views were obtained in M-mode imaging at the level of the papillary muscle. Measurements were based on the short axis view (SAX-LV protocol) of the heart acquired in B-mode and M-mode. Three consecutive beats in M-mode images were used for measurements of Left Ventricular Internal Diameter (LVID), interventricular septum (IVS) and Left Ventricular Posterior Wall (LVPW) in both diastole (d) and systole (s)44,45,46,47.

EKG analysis

M-mode physio data for the EKG recordings were analyzed. Systolic or diastolic peak distance of the M-mode images, and the R wave peak on the EKG physio data between the peaks were calculated by the image analysis software GraphPad prism 10. A minimum of five cardiac cycles were calculated for the analysis of the duration of P wave, PQ, QRS and St wave (ms). R-R wave duration (ms) and the amplitude of the R-wave (mV).

Western blot analysis

Total cardiac protein lysates were prepared from excised LV of NT and CKO age matched Never Pregnant (NP) and Post Partum (PP) female mice48. Liquid nitrogen-minced tissue was added to a modified RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl; 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1% NP-40; 0.5% Na-deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS) with 100X Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (11836170001, Millipore Sigma Danvers, MA, USA), 1 mM phenylmethyl sulphonyl fluoride, 50 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4. Fifty micrograms of protein was separated on an 8% or 14% SDS-Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1.5 M Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 0.5 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 30% acrylamide, N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylene diamine (TEMED), 10% SDS, and 10% w/v ammonium persulfate) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (#A29528232, Amersham™ Protran™ Premium 0.2 μm NC, Buckinghamshire, UK) followed by incubation with specific primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) at 4 °C overnight on a rocking platform. Membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (IRDye®800CW or 680LT Goat anti-Rabbit IgG H + L; LI-COR Biosciences Lincoln, NE, USA) and band intensities visualized using an Odyssey CLx LI-COR imager and protein expression levels quantified by scanning densitometry on Image Studio™ Lite Ver 5.2. normalized to GAPDH protein levels. Antibodies used for Western blotting are listed in Supplementary Table 2 and full immunoblot scans are in the Source data files.

Quantitative-real time-polymerase chain reaction (Q-rt-PCR)

Q-rt-PCR was performed49. Total RNA was extracted from 80 μm of FFPE tissue blocks (from normal and PPCM human donors) using the RecoverAll™ Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (AM1975, Thermo Scientific Waltham, MA, USA) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using Oligo (dT) primers with a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-PCR (AMV) (11483188001, Roche) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR for the genes of interest was performed in triplicate using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX) (04913850001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). PCR temperature and cycling conditions involved: a pre-incubation cycle at 95 °C, 10 min, 45 cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 10 s, and DNA synthesis at 72 °C, 20 s in a StepOne™ Real-Time PCR thermal cycler. Primer pair sequences used are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Comparative Ct values with GAPDH as the housekeeping gene were used to calculate relative mRNA expression levels.

Human and mouse RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (15596-018, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) from Normal donor and PPCM patient LV heart tissue and from Ptrh2-flox(NT) controls and Ptrh2-CKO female mouse hearts from Never Pregnant (NP) and PostPartum (PP) groups, following manufacturer’s instructions.

Human RNA-seq

RNA-seq was performed by BGI Genomics (Cambridge, MA, USA). Quantity and quality of RNA were assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 and RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (5067-1511, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), high-quality RNA samples with RIN number > 7.0 were used to construct the sequencing library (MGIEasy RNA library Prep Set; BGI). Messenger RNA (mRNA) was then purified from total RNA (5 μg) using Dynabeads Oligo (dT; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, CA, USA) with two rounds of purification. Following purification, the mRNA was fragmented into short fragments using divalent cations under elevated temperature (under 94 °C, 5–7 min; Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module e6150, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Cleaved RNA fragments were reverse-transcribed to create cDNA by SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (1896649, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), which were used to synthesize U-labeled second-stranded DNAs with E. coli DNA polymerase I (m0209, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), RNase H (m0297, New England Biolabs) and dUTP Solution (R0133, Thermo Fisher). An A-base was then added to the blunt ends of each strand, preparing them for ligation to the indexed adapters. Each adapter contained a T-base overhang for ligating the adapter to the A-tailed fragmented DNA. Dual-index adapters were ligated to the fragments, and size selection was performed with AMPureXP beads. After the heat-labile UDG enzyme (m0280, New England Biolabs) treatment of the U-labeled second-stranded DNAs, the ligated products were amplified with PCR by the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; 8 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 15 s, annealing at 60 °C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and then final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The average insert size for the final cDNA libraries was 300 ± 50 bp. 2 × 150 bp paired-end sequencing (PE150) on an DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI) was performed. The profiling of differentially expressed genes and transcripts was performed according to the methodology used by LC Sciences50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. Heat maps of human heart were generated using iDEP (Version .96). Fifty DEGs were associated with pathways, including PPCM/DCM, cardiac hypertrophy and conduction were analyzed. Only genes with an FDR below 0.5 and absolute fold change (FC) between −1.5 to 1.5 were analyzed.

Mouse RNA-seq

RNA sequencing and analysis was performed by the Translational Genomics Core at the Louisiana State University Health Science Center (New Orleans, LA). RNA quality (Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) concentration (Qubit RNA HS Assay kit, 11732088; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were assessed. Illumina Stranded Total RNA prep with Ribo-Zero Plus (400800; Agilent Technologies) generated libraries according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ribosomal RNA was depleted from total RNA (100 ng), purified, fragmented, and first- and second-strand cDNA synthesized. cDNA libraries were made from by adenylating the 3′ end and ligating anchors to the ends. A PCR amplification step (13 cycles) added unique indexes to the ligated products. The libraries were quantified (Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit;11732020, Invitrogen), size, and purity assessed using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequence platform.

RNA sequencing and analysis

FASTQ files were downloaded from the Illumina BaseSpace Hub and uploaded to Partek Flow. Contaminants (rDNA, tRNA, mtrDNA) were removed using Bowtie 2.2.5 and then aligned to STAR 2.7.8a (to the mm10 version of the mouse genome) and quantified with RefSeq Transcripts 96. Genes with less than 5 reads across all samples were filtered out from any further analyses. Genes with false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were considered significantly different between groups. Heatmaps, pathway analysis and gene ontology analysis were all performed in Partek Flow. The first 100 genes with the parameter of false discovery rate (FDE, q-value) below 0.05 and absolute fold change (FC) between −1.5 to 1.5 were analyzed.

STRING network analysis

String analysis was performed using STRING (Version 12.0). The network view summarizes predicted associations for groups of proteins. Default analysis provides calculations for enrichment scores p-values and FDR values.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using software GSEA (v4.1.0) and MSigDB to identify whether a set of genes in specific GO terms, KEGG pathways, DO terms, and Reactome showed significant differences in two groups. Briefly, gene expression matrix was inputted, and genes ranked by Signal-to-Noise normalization method. Enrichment scores and p-values were calculated in default parameters. GO terms and KEGG pathways (DO terms, Reactome) meeting this condition with |NES | > 1, NOM p-value < 0.05, FDR q-value < 0.25 were considered to be different in two groups61,62.

Statistical analysis

Differences between two groups were assessed by unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-tests or Two-way ANOVA. Data are analyzed from at least three independent assays and results shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance of p-values < 0.05 or greater was accepted.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are available in the article, in the Supplementary Information file, and in the Source data file. The processed and raw data files generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession code GSE31256. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE312561) Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Davis, M. B., Arany, Z., McNamara, D. M., Goland, S. & Elkayam, U. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. College Cardiol. 207–221 (2020).

Jha, N. & Jha, A. K. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail. Rev. 26, 781–797 (2021).

Douglass, E. J. & Blauwet, L. A. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Cardiology Clinics, 119–142 (2021).

Kolte, D. et al. Temporal trends in incidence and outcomes of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: A nationwide population-based study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, (2014).

Arany, Z. & Elkayam, U. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation 133, 1397–1409 (2016).

Bauersachs, J. et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Study Group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21, 827–843 (2019).

Goli, R. et al. Genetic and phenotypic landscape of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation 143, 1852–1862 (2021).

Smith, E. D. et al. Desmoplakin cardiomyopathy, a fibrotic and inflammatory form of cardiomyopathy distinct from typical dilated or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation 141, 1872–1884 (2020).

Morales, A. et al. Rare variant mutations in pregnancy-associated or peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation 121, 2176–2182 (2010).

van Spaendonck-Zwarts, K. Y. et al. Titin gene mutations are common in families with both peripartum cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 35, 2165–2173 (2014).

Ommen, S. R. et al. AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 142, e558–e631 (2020). 2020.

Garfinkel, A. C., Seidman, J. G. & Seidman, C. E. Genetic pathogenesis of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail. Clin. 14, 139–146 (2018).

Zamorano, J. L. et al. ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: The task force for the diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 35, 2733–2779 (2014). 2014.

Spudich, J. A. Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy: Four decades of basic research on muscle lead to potential therapeutic approaches to these devastating genetic diseases. Biophys. J. 106, 1236–1249 (2014).

Towbin, J. A. et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 16, e301–e372 (2019).

Spracklen, T. F. et al. Genetics of peripartum cardiomyopathy: current knowledge, future directions and clinical implications. Genes 12, 1–14 (2021).

Chakafana, G. et al. Heat shock proteins: potential modulators and candidate biomarkers of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 633013 (2021).

Sliwa, K. et al. Risk stratification and management of women with cardiomyopathy/heart failure planning pregnancy or presenting during/after pregnancy: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Study Group on Peripartum Cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 23, 527–540 (2021).

Yotti, R. et al. Advances in the genetic basis and pathogenesis of sarcomere cardiomyopathies. Annu Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 20, 129–153 (2019).

Honigberg, M. C. & Givertz, M. M. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. BMJ 364, k5287 (2019).

Ricke-Hoch, M. et al. Opposing roles of Akt and STAT3 in the protection of the maternal heart from peripartum stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 101, 587–596 (2014).

Lee, Y. Z. J. & Judge, D. P. The role of genetics in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 10, 437–445 (2017).

Hilfiker-Kleiner, D. et al. A Cathepsin D-Cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy. Cell 128, 589–600 (2007).

Shi, L. et al. β1 adrenoceptor antibodies induce myocardial apoptosis via inhibiting PGC-1α-related pathway. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20, 269 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Shi, L., Chen, M. & Liu, J. β1-Adrenoceptor antibodies induce PPCM via inhibition of PGC-1α related pathway. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 55, 160–167 (2021).

Corpuz, A. D., Ramos, J. W. & Matter, M. L. PTRH2: an adhesion regulated molecular switch at the nexus of life, death, and differentiation. Cell Death Discov. 6, 124 (2020).

Griffiths, G. S. et al. Bit-1 mediates integrin-dependent cell survival through activation of the NFκB pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 14713–14723 (2011).

Jan, Y. et al. A mitochondrial protein, Bit1, mediates apoptosis regulated by integrins and Groucho/TLE corepressors. Cell 116, 751–762 (2004).

Griffiths, G. S. et al. Bit-1 is an essential regulator of myogenic differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 128, 1707–1717 (2015).

Doe, J. et al. PTRH2 gene mutation causes progressive congenital skeletal muscle pathology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 1458–1464 (2017).

Hu, H. et al. Mutations in PTRH2 cause novel infantile-onset multisystem disease with intellectual disability, microcephaly, progressive ataxia, and muscle weakness. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 1, 1024–1035 (2014).

Le, C. et al. Infantile-onset multisystem neurologic, endocrine, and pancreatic disease: case and review. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 46, 459–463 (2019).

Picker-Minh, S. et al. Phenotype variability of infantile-onset multisystem neurologic, endocrine, and pancreatic disease IMNEPD. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 11, 52 (2016).

Sharkia, R. et al. Homozygous mutation in PTRH2 gene causes progressive sensorineural deafness and peripheral neuropathy. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 173, 1051–1055 (2017).

Khamirani, H. J. et al. A novel PTRH2 missense mutation causing IMNEPD: a case report. Hum. Genome Var. 8, 23 (2021).

Hayakawa, Y. et al. Inhibition of cardiac myocyte apoptosis improves cardiac function and abolishes mortality in the peripartum cardiomyopathy of Gαq transgenic mice. Circulation 108, 3036–3041 (2003).

Cole, P., Cook, F., Plappert, T., Saltzman, D. & st. John Sutton, M. Longitudinal changes in left ventricular architecture and function in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 60, 871–876 (1987).

Chung, E., Yeung, F. & Leinwand, L. A. Akt and MAPK signaling mediate pregnancy-induced cardiac adaptation. J. Appl. Physiol. 112, 1564–1575 (2012).

Matter, M. L. & Ruoslahti, E. A signaling pathway from the alpha5beta1 and alpha(v)beta3 integrins that elevates bcl-2 transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27757–27763 (2001).

Sliwa, K. et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: Inflammatory markers as predictors of outcome in 100 prospectively studied patients. Eur. Heart J. 27, 441–446 (2006).

McLendon, P. M. & Robbins, J. Proteotoxicity and cardiac dysfunction. Circ. Res. 116, 1863–1882 (2015).

Kairouz-Wahbe, R. et al. Anoikis effector Bit1 negatively regulates Erk activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1528–1532 (2008).

Deng, K. Q. et al. Suppressor of IKKe is an essential negative regulator of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Commun. 7, 11432 (2016).

Tanaka, N. et al. Transthoracic echocardiography in models of cardiac disease in the mouse. Circulation 94, 1109–1117 (1996).

Gardin, J. M., Siri, F. M., Kitsis, R. N., Edwards, J. G. & Leinwand, L. A. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular mass and systolic function in mice. Circ. Res. 76, 907–914 (1995).

Syed, F., Diwan, A. & Hahn, H. S. Murine echocardiography: a practical approach for phenotyping genetically manipulated and surgically modeled mice. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 18, 982–990 (2005).

Tsujita, Y., Kato, T. & Sussman, M. A. Evaluation of left ventricular function in cardiomyopathic mice by tissue Doppler and color M-mode doppler echocardiography. Echocardiography 22, 245–253 (2005).

Peter, A. K. et al. Expression of normally repressed myosin heavy chain 7b in the mammalian heart induces dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e013318 (2019).

Gandhi, K. et al. Ontogeny and programming of the fetal temporal cortical endocannabinoid system by moderate maternal nutrient reduction in baboons (Papio spp. Physiol. Rep. 7, e14024 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D545–D551 (2021).

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. Quantitative trait Loci analysis using the false discovery rate. Genetics 171, 783–790 (2005).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Sahraeian, S. M. E. et al. Gaining comprehensive biological insight into the transcriptome by performing a broad-spectrum RNA-seq analysis. Nat. Commun. 8, 59 (2017).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet 25, 25–29 (2000).

Carbon, S. et al. The Gene Ontology resource: Enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D325–D334 (2021).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J., Smyth, G. K. & Edge, R. A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2009).

Pertea, M., Kim, D., Pertea, G. M., Leek, J. T. & Salzberg, S. L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1650–1667 (2016).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 20, 278 (2019).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH/NICHD RO1HD091162 to M.L. Matter). Human RNA-seq and analysis were performed by BGI Genomics. Mouse heart RNA-seq and analysis were performed by the Translational Genomics Core (TGC) at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, LA, that is supported by NIH COBRE III P30GM114732 and 1P20GM12188 grants. We thank Melody C. Baddoo and the Tulane Cancer Center Next Generation Sequence Bioinformatics Core for RNA-seq support and analysis (Tulane Cancer Center, Cancer Crusaders Next Generation Sequence Bioinformatics Core and the LCRC (funded, in part, by an NCI-supported P01 Program Project Grant (P01CA214091) in partnership with the University of Florida, “Gammaherpesvirus noncoding RNAs in AIDS malignancies” and the LSUHSC Tumor Virology COBRE). We also acknowledge the assistance of The University of Hawaii Cancer Center Pathology Core and the Genomics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource (GSR; supported in part by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA071789). We acknowledge the use of human heart tissues procured by the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI; with support from NIH grant no. U42OD11158) and Accio BiobankOnline.com (Tissue for Research). Figures 1a, 3a, 4h, 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2a were prepared using www.biorender.com (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.M. conceived and designed the study. P.C., S.L., V.M.-U., C.B.W., K.P., B.Y.H., and M.L.M. acquired the data. P.C., V.M.-U., S.L., C.B.W., N.G., J.W.R. and M.L.M. analyzed and interpreted the data. P.C., V.M.-U. and M.L.M. wrote the manuscript. P.C., J.W.R. and M.L.M. edited the manuscript. P.C., C.B.W., N.G., F.J.A. and M.L.M. revised the manuscript. P.C., V.M.-U., and F.J.A. performed statistical, genetic, protein and bioinformatics analysis of the mouse and mouse genotyping. P.C. and S.L. performed echocardiography, EKG data acquisition and analysis. C.B.W. performed caspase 3 inhibitor and inactive control experiments, echocardiography and statistical analysis. P.C. performed hydroxyproline assays. V.M.-U. and K.P. prepared samples for RNA-seq. F.J.A. and V.M.-U. and WSY performed mRNA Q-rt-PCR and analysis. P.C., V.M.-U., B.Y.H. performed immunostaining assays, imaging acquisition and analysis. P.C. performed Tunel Assay and quantification. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Dean Burkin, Tatsuya Morimoto and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya-Uribe, V., Choubey, P., Walton, C.B. et al. Peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase 2 is a negative regulator of peripartum cardiomyopathy with heart failure in female mice. Nat Commun 17, 1091 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67852-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67852-9