Abstract

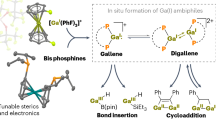

The homocatenation of electron-deficient Group 13 metals to form metal-metal multiple bonds through covalent self-assembly remains extremely challenging. Herein we demonstrate the synthesis and characterizations of N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-stabilized digallyl digallenes (1a and 1b), which exhibit unsaturated Ga-Ga=Ga-Ga chains with trans-bent geometries. These compounds were synthesized through salt-metathesis reactions using Cp*Ga, (L1)K2/(L2)Li2, and 1,3-diisopropyl-4,5-dimethylimidazol-2-ylidene (IiPr). Employing both experimental and computational techniques, our investigation reveals that the chain elongation of 1a was initiated by the in-situ generation of a gallium(I) carbene analog [(L1)GaK]. Additionally, the reactivity of compound 1a with I2, PhS-SPh, Ph3P = S, and Ph2C = O was explored, leading to the formation of tetra-gallium subhalides (4), disulfide addition product (5), a gallium thiirane analog (6), and a [2 + 2] cycloaddition product (7), respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Homocatenation is the process through which elements self-assemble covalently to create one-dimensional chain-like structures1,2,3,4. This phenomenon is prevalent among nonmetal elements and less common in metals5. Recently, structures featuring catenated metal-metal σ bonds have gained attention for their intriguing photophysical, magnetic, and redox properties, rendering them promising candidates for nanoscale applications such as wires, switches, single-molecule magnets, and luminescent materials1,6,7. While known metal chains are generally linked by σ bonds, the formation of unsaturated chains with alternating single and double metal-metal bonds through homocatenation is extremely rare, due to weaker orbital overlap and increased Pauli repulsion between metal centers8,9.

To date, only a limited number of metal catenation examples involving Group 14 and 15 elements have been reported10,11,12. For instance, Aldridge and his colleagues reported homocatenated heavier Group 14 complexes with unsaturated E-E=E-E (E = Ge or Sn) chains (Fig. 1)10,11. The hemi-labile pincer ligands with two flexible amine donors are crucial not only for stabilizing the active EI center but also for controlling the catenation behavior. Unlike [(ArNR2Ge)₄], which requires ligand assistance for conversion to [(ArNR2Ge)₂], the tetrameric structure [(ArNR2Sn)4] readily dissociates in benzene solution to form the dimer [(ArNR2Sn)2]10,11. Therefore, during small molecule activation, such as RSnH and CO2, it is the Sn-Sn single bond, rather than the Sn=Sn bond, functioning as the active site13. Very recently, Cornella and Neese et al. reported the synthesis of the heaviest known analogs of π-allyl cations featuring a (Bi)3+ core, which function as synthons for the transfer of Bi(I) cations12.

In contrast to Group 14 and 15 metals, Group 13 metals are intrinsically electron-deficient, predisposing them susceptible to decomposition and aggregation. Schnöckel14, Hill15, Linti16 and Jones17 have respectively discovered that Lewis-base-induced catenation of “GaI”/InI species can lead to the formation of chains exclusively linked by σ-bonds. Recently, Braunschweig and co-workers reported the synthesis and structural characterization of the first stable trialane, featuring a linear saturated Al-Al-Al chain18. The generation of unsaturated catenated chains with Group 13 metals has yet to be achieved. Herein, we describe the synthesis of digallyl digallenes (1a and 1b) featuring both Ga-Ga single and Ga=Ga double bonds, via the reaction of Cp*Ga (Cp* = pentamethylcyclopentadienyl) with two distinct Lewis bases: (L1)K2/(L2)Li2 (L1 = [(DipNCH)2]2−, L2 = [(DipNCH2)2]2−, Dip = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl) and 1,3-diisopropyl-4,5-dimethylimidazol-2-ylidene (IiPr). The reactivity study of compound 1a revealed versatile reaction modes, encompassing not only the oxidative cleavages of σ bonds with I2 and PhS-SPh, but also the facile activation of double bonds in triphenylphosphine sulfide (Ph3P=S) and benzophenone (Ph2C=O), in which the Ga=Ga moiety in the Ga4 chain serves as an intrinsically active site.

Results

When Cp*Ga was added dropwise into a mixture of (L1)K2 and IiPr in toluene, this combination immediately turned deep blue (Fig. 2a). The 1H NMR spectrum shows two distinct sets of signals corresponding to two new compounds, each containing [(DipNCH)2]2- and IiPr in a 1: 1 ratio. After workup, a deep blue powder 1a and a light-yellow solid 2 were isolated in 20% and 19% yields, respectively. Single crystals of 1a were obtained from a saturated toluene solution, and single crystal X-ray diffractometry (SC-XRD) analysis revealed a Ga4 chain with a trans-planar geometry (Fig. 2b). The Ga1-Ga2 and Ga1’-Ga2’ bond lengths of 2.433(13) Å fall within the range of those reported for Ga-Ga single bonds (2.33–2.54 Å). The Ga2-Ga2’ bond length of 2.332(10) Å is shorter than those in previously reported neutral digallenes [Ga2(tBu2MeSi)2(IiPr)2 (A): 2.341(3) Å; Ar’GaGaAr’ (B; Ar’ = 2,6-Dip2C6H3): 2.627(7) Å]19,20 and cyclic 2π-aromatic Gan (n = 3 or 4) sepecies21,22 [Na2[(Mes2C6H3)Ga]3 (Mes = 2,4,6-Me3C6H2): 2.441(1) Å; K2[Ga4(C6H3-2,6-Trip2)2] (Trip = C6H2-2,4,6-iPr3): 2.462–2.468 Å], indicating a metal-metal double bond in a homocatenated Group 13 chain23,24. Both Ga1 and Ga1’ atoms exhibit trigonal-planar geometry with a sum of the angles of 359.28°, while Ga2 and Ga2’ atoms adopt a trigonal pyramidal configuration (the sum of the internal angles at Ga2/Ga2’: 340.76°). The Ga1-Ga2-Ga2’-Ga1’ and C27-Ga2-Ga2’-C27’ units are coplanar, each with a torsion angle of 180.00°, and the dihedral angle between these two planes is 54.94°. Monitoring the ¹H NMR spectrum in C₆D₆ showed that 1a is unstable at room temperature and partially converts to compound 2, reaching 71% conversion after 20 days (Supplementary Fig. S1). This transformation was accompanied by precipitation of gallium metal, as confirmed by SEM-EDS analysis (Supplementary Fig. S7).

a Synthesis of compounds 1a, 1b, 2, and 3. b Molecular structure of 1a in the solid state. H atoms are omitted for clarity; Me-, iPr-, and Dip-substituents are depicted as a wireframe for simplicity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): Ga2-Ga2’ 2.332(10), Ga1-Ga2 2.433(13), Ga2-C27 2.084(12), Ga2’-C27’ 2.084(12), Ga1-N1 1.892(9), Ga1-N2 1.890(8); Ga1-Ga2-Ga2’ 127.41(21), C27-Ga2-Ga2’ 112.32(22), Ga1-Ga2-C27 101.03(30).

The identity of compound 2 was revealed by SC-XRD analysis as an IiPr-stabilized gallium hydride with a pentagonal GaN2C2 ring (Fig. 3a). In the IR spectrum, the Ga-H bond stretching vibration of 2 was at 1859 cm-1, which was consistent with the known N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-stabilized gallium hydride complex [GaH{NC(Dip)C(H)}2(IMes)] (IMes = 1,3-bis-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) (ν = 1854 cm−1) (Supplementary Fig. S33)25. To investigate the source of hydrogen atoms of Ga-H in 2, the preparation of 2 from the toluene-d8 solution of 1a was performed and the presence of the Ga−H stretching vibrations in IR spectrum (ν = 1859 cm−1) suggests that the hydrogen atom connected to gallium center derives from the ligand rather than the solvent (Supplementary Fig. S34).

a Molecular structure of 2 and 3 in the solid state. H atoms are omitted for clarity except for H on the Ga; Me-, iPr-, and Dip-substituents are depicted as a wireframe for simplicity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 2: Ga1-N1 1.932(17), Ga1-N2 1.919(16), Ga1-C27 2.076(21); N1-Ga1-N2 89.59(7), N1-Ga1-C27 101.79(8), N2-Ga1-C27 117.09(8). For 3: Ga1-N1 1.902(18), Ga1-N2 1.902(21), Ga1-C27 2.089(23); N1-Ga1-N2 88.82(8), N1-Ga1-C27 118.61(9), N2-Ga1-C27 103.65(9). b EPR spectrum of compound 3 measured in toluene solution at room temperature. X-Band EPR spectrum at a microwave frequency of 9.2041 × 103 MHz at 293 K.

To further explore the effects of ligands on the assembly of gallium chains, we substituted (L1)K2 with (L2)Li2, resulting in the formation of a deep blue species 1b and an NMR-silent purple compound 3, which were successfully separated by fractional crystallization in 24% and 10% yields, respectively. SC-XRD analysis of 1b unveiled a Ga4 chain adopting a trans-planar geometry, similar to that observed in 1a (Supplementary Fig. S3). The Ga2-Ga2’ bond length in 1b is 2.374(12) Å, slightly longer than that in 1a (2.332(10) Å). Meanwhile, the Ga1-Ga2 and Ga1′-Ga2′ distances in 1b measure 2.430(9) Å, comparable to those in 1a (2.433(13) Å). Compound 3 was characterized by SC-XRD analysis, revealing an IiPr-stabilized gallium radical with a GaN2C2 ring26,27,28. The Ga-N bond lengths in 3 (approximately 1.902 Å) are slightly longer than those in 2 (1.92–1.93 Å). The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum of 3 in toluene solution at room temperature exhibits g-value is 2.0032 (Fig. 3b). Due to the hyperfine splitting with gallium nuclei [69Ga (60.1%) and 71Ga (39.6%)] with I = 3/2 and 14N nuclei with I = 1, the coupling constants were estimated to be A(69Ga) = 0.65 G, A(71Ga) = 0.70 G, A(14N) = 4.70 G, and A(14N) = 3.40 G. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) level reveal that the spin density in compound 3 is primarily localized on the gallium atom (Supplementary Fig. S15). Unlike compound 2, which can form from the degradation of 1a, compound 3 cannot be obtained through the analogous degradation of 1b.

DFT calculations at the M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) level of theory were performed to investigate the intrinsic electronic properties of 1a. The optimized structure of 1a compares well with its solid-state structure. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is characterized by an out-of-plane polarized π-bond over the Ga2-Ga2’ bond, with slight delocalization to the Ga1/Ga1′ atoms. The HOMO-3 reveals a Ga−Ga σ-bonding along the Ga4 backbone chain. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) consists of the antibonding π* orbital of the Ga2-Ga2’ bond, overlapping with the formally vacant p-orbitals of the Ga1/Ga1’ atoms. Compound 1a exhibits smaller HOMO-LUMO energy gap (3.59 eV) compared to 1b (3.71 eV) and other known neutral digallenes, such as Ga2(tBu2MeSi)2(IiPr)2 (A, 4.00 eV) and Ar’GaGaAr’ (B, 4.32 eV) (Fig. 4a). Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis illustrates that the Ga2-Ga2’ bond contains both σ-orbital (1.90 e−) and π-orbital (1.77 e−) interactions (Table 1). This interaction pattern is distinct from that observed in B but is comparable to 1b (σ-orbital: 1.86 e− and π-orbital: 1.77 e−) and A (σ-orbital: 1.87 e− and π-orbital: 1.76 e−). The Wiberg bond index (WBI) of the Ga2-Ga2’ bond (1.59) in 1a is larger than those in 1b (1.55), A (1.56), and B (0.89), showing the shortest double-bond character among reported digallene species. Second-order perturbation theory analysis (SOPA) of 1a uncovers existing donor-acceptor interactions from Ga2-Ga2’ π electron density to the digallyl groups, suggesting π-conjugated properties (Supplementary Fig. S11). Natural population analysis (NPA) shows Ga2/Ga2’ atoms in 1a (–0.37) and 1b (–0.35) possess higher negative charges compared to those in A (+0.01/ + 0.20) and B (+0.72), which can be attributed to the enhanced σ-donating properties of the attached digallyl groups.

The quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analysis discloses bond paths (BPs) among the gallium atoms and three bond critical points (BCPs) along the Ga4 chain (Fig. 4b)29,30. The Laplacian of the electron density for 1a shows that the Ga1-Ga2/Ga1′-Ga2′ bonds (▽2ρ(BCP) = –0.0095) and the Ga2-Ga2′ bond (▽2ρ(BCP) = –0.0026) are shared-shell-type interactions31,32. The delocalization index (DI) value for the Ga2-Ga2′ (DIGa2-Ga2’ = 1.40) bond is larger than that in 1b (DIGa2-Ga2′ = 1.36) and B (DIGa-Ga = 0.98) but equal to that in A (DIGa-Ga = 1.40). Additionally, ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry was employed to study electronic transitions of 1a. The UV-Vis spectrum of 1a shows a maximum absorption band at 600 nm in the visible light region, corresponding to HOMO → LUMO (π→π*) electron transition, as supported by time-dependent DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. S6). This absorption is red-shifted compared to that of 1b (λmax: 581 nm) and A (λmax: 520 nm).

To gain insight into a plausible mechanism for the chain growth of 1a, a joint experimental and computational study was carried out. We hypothesized that a gallium(I) carbene analog [(L1)GaK]33,34 is possibly produced in situ during the initial step through the metathesis35,36 of Cp*Ga with (L1)K2, and that this species acts as a gallium-homocatenation intermediate. To test this hypothesis, we prepared isolable (L1)GaK according to previously reported methods33. Subsequently, the successful synthesis of the target compound 1a from (L1)GaK via reaction with Cp*Ga and IiPr substantiated the role of (L1)GaK as an intermediate in the process (Fig. 5). To further verify the proposed mechanism, we performed DFT calculations at the M06-2X/6-311G(d,p)/IEFPCM(Toluene) level of theory (Fig. 6). Initially, the interaction between (L1)K2 and Cp*Ga surmounts an energy barrier of 9.4 kcal/mol, leading to TS1 characterized by a potassium-gallium-potassium (K···Ga···K) interaction. Following this, the Cp* moiety of Cp*Ga migrates towards one of the potassium atoms, facilitating the release of Cp*K from the complex and resulting in the formation of the key intermediate Int2 [(L1)GaK + Cp*K]. Int3 [(L1)GaK] subsequently reacts with another molecule of Cp*Ga, overcoming a relatively modest energy barrier of 21.1 kcal/mol to form the intermediate Int5 [(L1)Ga-Ga + Cp*K]. Int6 [(L1)Ga-Ga] then undergoes coordination with IiPr carbene, resulting in the formation of IiPr–gallium complexes Int7 [(L1)Ga-Ga(IiPr)], which is highly exergonic with an energy release of –40.5 kcal/mol. Ultimately, the Int7 complex dimerizes, leading to the formation of the final product 1a. We also evaluated an alternative pathway involving dimerization of Int6 followed by IiPr coordination, but found it to be less favorable (Supplementary Fig. S22).

To explore the reactivity of compound 1a, characterized by its unsaturated Ga4 chain, we embarked on a series of experiments (Fig. 7). Upon introducing one equivalent of I2 into a toluene solution of 1a, an immediate color transition from deep blue to light yellow was observed. The resulting purification yielded the oxidized iodinated product 4. SC-XRD analysis revealed that compound 4 contains two molecules in the asymmetric unit, each with subtle differences in bond lengths and angles, with one illustrated in Fig. 8 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Structurally, compound 4 is characterized as a tetra-gallane with the saturated Ga₄ chain37,38,39. The bond length between Ga2 and Ga3 in 4 (2.457(7) Å) is significantly longer than that in 1a (Ga2-Ga2’: 2.332(15) Å). The bond lengths between Ga1 and Ga2 (2.446(5) Å) and between Ga3 and Ga4 (2.437(9) Å) in 4 are slightly longer than those in 1a (Ga1-Ga2/Ga1’-Ga2’: 2.433(8) Å). Remarkably, the reduction of 4 by KC8 successfully regenerated compound 1a. Similarly, when compound 1a was reacted with the stoichiometric oxidant PhS-SPh, the central Ga=Ga π-bond was cleaved, yielding compound 5 through straightforward S-S bond cleavage24. SC-XRD analysis indicated that compound 5, analogous to 4, possesses a saturated Ga4 chain adorned with SPh side groups.

H atoms are omitted for clarity; Me-, iPr-, Ph, and Dip-substituents are depicted as a wireframe for simplicity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 4: Ga2-I1 2.687(11), Ga3-I2 2.649(5), Ga1-Ga2 2.446(5), Ga2-Ga3 2.457(5), Ga3-Ga4 2.437(9); I1-Ga2-Ga3 100.59(28), I2-Ga3-Ga2 102.16(23), Ga1-Ga2-Ga3 122.34(40), Ga2-Ga3-Ga4 137.40(36); for 5: Ga2-S1 2.352(3), Ga3-S2 2.352(3), Ga1-Ga2 2.494(3), Ga2-Ga3 2.515(4), Ga3-Ga4 2.494(3); S1-Ga2-Ga3 96.04(5), Ga1-Ga2-Ga3 133.62(5), Ga2-Ga3-Ga4 133.62(5).

In addition to homolytic cleavages of I-I and S-S bonds, we also explore the bond activation of compound 1a with the polar P=S double bond40,41,42,43,44. While the activation of carbon-carbon multiple bonds has been extensively studied, the activation of digallenes with polar multiple bonds is much less explored. The reaction of compound 1a with triphenylphosphine sulfide (Ph3P=S) produced a high-strain thiagallacyclopropane analog 6 through a similar controlled [1 + 2] cycloaddition reaction45,46. This contrasts with the reaction of digallene B with S8, which forms species (Ar’GaS)2 containing a four-membered Ga2S2 ring19,47,48. Compound 6 was confirmed through multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and SC-XRD analysis. The crystals of 6 exhibit two molecules in the asymmetric unit, each displaying slightly varying bond lengths and angles, one of which is illustrated in Fig. 9 (Supplementary Fig. S5). The Ga-S bond lengths in 6 (ranging from 2.46 to 2.47 Å) are significantly extended compared to those in 5 (ca. 2.35 Å). NBO analysis of 6 indicates σ-bonding electron densities of 1.88 e− for the Ga–Ga bond and 1.94 e⁻ for each Ga–S bond within the Ga₂S ring. The WBI of the intra-ring Ga–Ga bond is 0.89 and the Ga–S bonds exhibit WBIs of 0.75. Notably, this represents the isolation of a gallium thiirane analog, distinguished by its unique three-membered Ga2S core structure.

H atoms are omitted for clarity; Me-, iPr-, Ph, and Dip-substituents are depicted as a wireframe for simplicity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 6: Ga2-S1 2.465(1), Ga3-S1 2.457(2), Ga1-Ga2 2.395(2), Ga2-Ga3 2.509(1), Ga3-Ga4 2.395(2); Ga2-S1-Ga3 60.28(4), S1-Ga2-Ga3 59.20(4), S1-Ga3-Ga2 59.52(4); for 7: Ga2-O1 1.886(1), Ga3-C38 2.169(1), O1-C38 1.411(1), Ga1-Ga2 2.515(1), Ga2-Ga3 2.509(1), Ga3-Ga4 2.571(1); O1-Ga2-Ga3 77.23(3), O1-C38-Ga3 100.07(4), C38-Ga3-Ga2 71.20(3).

Encouraged by this result, we further expanded the reactivity of compound 1a with C=O double bond. While the facile C=O bonding activation by homobimetallic species featuring non-polar multiple bonds has been reported, analogous reactivity involving Ga=Ga species remains unexplored13,49,50,51,52. The reaction between 1a and benzophenone resulted in the formation of [2 + 2] cycloaddition product 7. The SC-XRD analysis uncovered that compound 7 possess a nearly planar four-membered Ga2CO ring (the sum of the internal angles: 359.92°). The Ga2-O1 bond length of 1.886(1) Å falls within the typical range for Ga-O single bonds, whereas the slightly longer Ga3-C38 bond length of 2.169(1) Å is likely attributed to steric effects. Interestingly, we found that the [2 + 2] cycloaddition between 1a and benzophenone is reversible, as compound 1a can be regenerated from 7 through heat treatment or irradiation53,54. In contrast to previously reported irreversible systems, the [2 + 2] cycloaddition described here proceeds reversibly between a main-group element-based multiple bond and a ketone. Additionally, we examined the reactivity of 1a with other small molecules such as H₂, NH₃, and CO. However, likely due to the inherent instability of 1a, these reactions predominantly resulted in decomposition to compound 2.

In summary, this study unveils a methodology for synthesizing gallium chains, leading to the production of doubly IiPr-stabilized 1,2-digallyldigallenes (1a and 1b) through salt-metathesis reactions employing Cp*Ga, (L1)K2/(L2)Li2, and IiPr. SC-XRD analysis unambiguously confirms the unsaturated Ga₄ chain structure in 1a, while theoretical study provides its π-conjugated Ga4 chain with a notably small HOMO-LUMO gap of 3.59 eV. Exploration of compound 1a’s reactivity demonstrates that the Ga=Ga unit undergoes controlled oxidative additions with I2, forming tetra-gallium subhalides (4). The reaction between 1a and PhS-SPh yields disulfide-substituted product 5 via controlled addition to the Ga=Ga moiety. Additionally, compound 1a may activate P = S and C = O double bonds, potentially leading to the production of a gallium analog of thiirane (6) and a [2 + 2] cycloaddition product (7).

Methods

General considerations

All reactions were performed under an atmosphere of dry argon using standard Schlenk or dry box techniques; solvents were dried over Na metal, K metal or CaH2, and distilled under nitrogen. Reagents were of analytical grade, obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded on a Brucker Avance 400 and 500 MHz, spectrometers at 298 K. NMR multiplicities are abbreviated as follows: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, sept = septet, m = multiplet, br = broad. Compounds 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 for HRMS were analyzed by positive mode electrospray ionization (ESI) using Agilent 6530 QTOF mass spectrometer. Coupling constants J are given in Hz. Melting points were measured with BUCHI Labortechnik AG. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vertex 70 V spectrometer. Ultraviolet spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 750 UV/Vis spectrophotometer. The Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) spectrum was recorded by a JES X320 (JEOL Co.). The spectral simulations were performed using MATLAB R2024b and the EasySpin toolbox55. Element analyses were performed on an Elementar Vario EL III instrument.

Synthesis of 1a:Method A

A toluene solution (20.0 mL) containing (L1)K2 (L1 = [(DipNCH)2]2−) (0.908 g, 2.000 mmol) and IiPr (0.360 g, 2.000 mmol) was added with Cp*Ga (0.820 g, 4.000 mmol) at ambient temperature. The reaction mixture immediately exhibited a color transition from red to deep blue. After vigorous stirring for 2 h at room temperature, the suspension was filtered through a glass frit, and the retained solids were subjected to thorough extraction with tetrahydrofuran (40.0 mL). Concentration of the combined filtrates under reduced pressure yielded compound 1a as a deep blue crystalline solid (0.557 g, 20%) (Single crystals of 1a suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained from a hexane/toluene mixed solution). Mp: 163.7–164.8 °C (dec). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6): δ = 0.84–0.88 (m, 24 H, CH3), 1.01 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 24 H, CH3), 1.34 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 24 H, CH3), 1.64 (s, 12 H, CH3), 3.71 (sept, J = 6.9 Hz, 8 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.30 (sept, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 6.26 (s, 4 H, CH), 7.14 (m, 12 H, Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, D8-THF): δ = 10.1 (CCH3), 20.5 (CH(CH3)2), 21.5 (CH(CH3)2), 28.4 (CH(CH3)2), 54.2 (CH(CH3)2), 122.0 (CH), 122.9 (Ar-C), 124.5 (Ar-C), 126.8 (CCH3), 146.0 (Ar-C), 149.1 (Ar-C), 177.5 (NCN); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C74H112Ga4N8: 1389.6106 [(M + H)]+; found: 1389.6112; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C74H112Ga4N8: C 63.82, H 8.11, N 8.05; found: C 63.51, H 7.95, N 8.44. Method B: A toluene solution (20.0 mL) containing (L1)GaK·(Et2O) (1.119 g, 2.000 mmol) and IiPr (0.360 g, 2.000 mmol) was added with Cp* Ga (0.410 g, 2.000 mmol) at ambient temperature. The reaction mixture immediately exhibited a color transition from red to deep blue. After vigorous stirring for 2 h at room temperature, the suspension was filtered through a glass frit, and the retained solids were subjected to thorough extraction with tetrahydrofuran (40.0 mL). Concentration of the combined filtrates under reduced pressure yielded compound 1a as a deep blue crystalline solid (0.947 g, 17%).

Synthesis of 1b and 3

A hexane solution (15.0 mL) containing (L2)Li2 (L2 = [(DipNCH2)2]2−) (0.395 g, 1.000 mmol) and IiPr (0.180 g, 1.000 mmol) was added with Cp*Ga (0.410 g, 2.000 mmol) at ambient temperature. The reaction mixture immediately exhibited a color transition from red to deep blue. After stirring for 3 h at room temperature, the resulting suspension was filtered through a glass frit. The collected solid was washed with toluene and dried under vacuum to afford 1b as a deep blue solid (0.150 g, 24%). Single crystals of 1b suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from a hexane/toluene mixed solution. The filtrate was concentrated by slow evaporation at ambient temperature, yielding 3 as purple crystals (0.063 g, 10%). 1b: Mp: 169.0–171.7 °C (dec). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ = 0.82–0.87 (m, 24 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.02 (br, 24 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.41 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 24 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.65 (s, 12 H, CH3), 3.63 (s, 8 H, CH2), 3.97 (sept, J = 6.7 Hz, 8 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.29 (sept, J = 6.6 Hz, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 7.09–7.13 (m, 12 H, Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, D8-THF): δ = 10.1 (CCH3), 20.6 (CH(CH3)2), 21.1 (CH(CH3)2), 23.3 (CH(CH3)2), 28.3 (CH(CH3)2), 54.3 (CH(CH3)2), 58.8 (CH2), 123.4 (Ar-C), 123.5 (Ar-C), 126.8 (CCH3), 147.5 (Ar-C), 151.1 (Ar-C); The NCN (IiPr) carbon signals were not observed in the 13C{1H} spectrum probably due to coupling with the 69Ga nucleus. The 13C{1H} NMR measurement was performed with a deuterated solvent mixture of C6D6/D8-THF and the lock was achieved via D8-THF; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C74H116Ga4N8: 1393.6419 [(M + H)]+; found: 1393.6410; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C74H116Ga4N8: C 63.64, H 8.37, N 8.02; found: C 63.91, H 8.95, N 8.54. 3: Mp: 90.0–90.8 °C (dec). HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C37H58GaN4: 628.3990 [(M + H)]+; found: 628.3976; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C37H58GaN4: C 70.70, H 9.30, N 8.91; found: C 71.35, H 9.82, N 9.67.

Synthesis of 2

Cp*Ga (0.410 g, 2.000 mmol) was added into a mixture of [(L1)K2] (0.454 g, 1.000 mmol) and IiPr (0.180 g, 1.000 mmol) in toluene (30.0 mL) at room temperature. After stirring for one month, the color of the solution changed from deep blue to yellow. After filtration, volatiles of the filtrate were removed under vacuum. The residual solid was washed with hexane (4.0 mL), and then dried under vacuum to afford 2 as a yellow solid (0.116 g, 19 %) (Single crystals of 2 suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained from a hexane/toluene mixed solution). Mp: 96.4–97.7 °C (dec). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6): δ = 1.01 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 12 H, CH3), 1.25 (br, 12 H, CH3), 1.44 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 12 H, CH3), 1.47 (s, 6 H, CH3), 3.97 (br, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.38 (sept, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.99 (s, 2 H, CH), 7.18 - 7.26 (m, 6 H, Ar-H); The Ga-H hydrogen signals were not observed in the 1H spectrum probably due to coupling with the 69Ga nucleus; 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, C6D6): δ = 10.0 (CCH3), 21.8 (CH(CH3)2), 25.4 (CH(CH3)2), 28.0 (CH(CH3)2), 52.3 (CH(CH3)2), 122.1 (CH), 122.9 (Ar-C), 124.0 (Ar-C), 126.0 (CCH3), 146.4 (Ar-C), 149.3 (Ar-C), 166.8 (NCN); IR (solid, cm-1): 613, 678, 754, 795, 1041, 1251, 1351, 1459, 1554, 1625, 1664, 1862, 1864; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C37H57GaN4: 627.3912 [(M + H)]+; found: 627.3920; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C37H57GaN4: C 70.81, H 9.15, N 8.93; found: C 71.16, H 9.42, N 8.67.

Synthesis of 4

A mixture of compound 1a (0.140 g, 0.100 mmol) and I2 (0.051 g, 0.200 mmol) in toluene (10.0 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours, during which the solution color transitioned from blue to yellow. Subsequently, the mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was subjected to slow evaporation, yielding compound 4 as yellow crystals (0.049 g, 30%). Mp: 182.9–183.5 °C (dec). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6): δ = 1.00 (br, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.14 (br, 24 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.24 (br, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.33 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 24 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.62 (s, 12 H, CH3), 3.52 (sept, J = 6.8 Hz, 8 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.56 (br, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 6.23 (s, 4 H, CH), 7.16–7.18 (m, 12 H, Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, C6D6): δ = 10.3 (CCH3), 21.7 (CH(CH3)2), 23.3 (CH(CH3)2), 24.6 (CH(CH3)2), 24.7 (CH(CH3)2), 26.0 (CH(CH3)2), 26.1 (CH(CH3)2), 26.25 (CH(CH3)2), 26.3(CH(CH3)2), 28.4 (CH(CH3)2), 54.2 (CH(CH3)2), 123.0 (Ar-C), 123.2 (Ar-C), 125.1 (Ar-C), 127.4, 128.0, 128.2, 128.4, 128.6, 145.6 (Ar-C), 148.5 (Ar-C), 162.1 (NCN); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C74H112Ga4I2N8: 1643.4195 [(M + H)]+; found: 1643.4187; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C74H112Ga4I2N8: C 53.98, H 6.86, N 6.81; found: C 54.66, H 6.42, N 7.67.

Synthesis of 5

1a (0.140 g, 0.100 mmol) and PhS-SPh (0.022 g, 0.100 mmol) were added in toluene (10.0 mL) at room temperature. Subsequently, the color of the solution changed from blue to yellow. The mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was subjected to slow evaporation, yielding compound 5 as yellow crystals (0.071 g, 30%). Mp: 159.2–160.9 °C (dec). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ = 0.68 (br, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 0.94 (br, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.03 (br, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.23 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.27 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.37 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.42 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.57 (s, 12 H, CCH3), 1.61 (br, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 3.35 (sept, J = 6.8 Hz, 1 H, CH(CH3)2), 3.58 (br, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 3.68 (br, 3 H, CH(CH3)2), 4.44 (br, 1 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.50 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 6.21 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 4 H, CH), 6.34 (br, 1 H, CH(CH3)2), 6.68–7.54 (m, 22 H, Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, C6D6): δ = 10.4 (CCH3), 10.6 (CCH3), 21.7 (CH(CH3)2), 23.6 (CH(CH3)2), 24.4 (CH(CH3)2), 25.0 (CH(CH3)2), 25.7 (CH(CH3)2), 26.1 (CH(CH3)2), 26.7 (CH(CH3)2), 28.0 (CH(CH3)2), 28.1 (CH(CH3)2), 28.6 (CH(CH3)2), 29.0 (CH(CH3)2), 122.5, 122.6, 122.7, 123.7, 123.8, 124.0, 125.0, 125.2, 127.3, 128.0, 128.6, 131.7, 131.8, 142.8, 144.0, 145.2, 146.0, 147.3, 149.4, 149.5, 166.8 (NCN), 167.5 (NCN); The CH(CH3)2 (IiPr) carbon signals were not observed in the 13C{1H} spectrum; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C86H122Ga4N8S2: 1607.6330 [(M + H)]+; found: 1607.6317; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C86H122Ga4N8S2: C 64.12, H 7.63, N 6.96, S 3.98; found: C 63.61, H 7.99, N 7.44, S 3.55.

Synthesis of 6

A mixture of compound 1a (0.200 g, 0.144 mmol) and triphenylphosphine sulfide (Ph₃P = S, 0.063 g, 0.215 mmol) in toluene (10.0 mL) was heated at 90 °C for 3 h, during which the solution color changed from blue to organe. Subsequently, the volatile was removed under reduced pressure, yielding compound 6 as an orange solid (0.077 g, 50%) (Single crystals of 6 suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained from a hexane solution). Mp: 173.9–175.5 °C (dec). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ = 0.76 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 0.84 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 0.94 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 0.99 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.07 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.23 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.29 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.33 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 12 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.56 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.64 (s, 6 H, CH3), 3.59 (sept, J = 6.8 Hz, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 3.81 (br, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.03 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 6.26 (s, 4 H, CH), 6.38 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 7.09–7.19 (m, 12 H, Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, C6D6): δ = 9.6 (CCH3), 9.7 (CCH3), 20.5 (CH(CH3)2), 20.8 (CH(CH3)2), 21.7 (CH(CH3)2), 22.3 (CH(CH3)2), 24.6 (CH(CH3)2), 24.8 (CH(CH3)2), 25.0 (CH(CH3)2), 25.1 (CH(CH3)2), 28.3 (CH(CH3)2), 28.8 (CH(CH3)2), 52.8 (CH(CH3)2), 53.3 (CH(CH3)2), 122.5 (CH), 122.9 (Ar-C), 123.1 (Ar-C), 124.7 (CCH3), 145.5 (Ar-C), 145.8 (Ar-C), 148.6 (Ar-C), 169.8 (NCN); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C74H112Ga4N8S: 1421.5827 [(M + H)]+; found: 1421.5839; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C74H112Ga4N8S: C 62.39, H 7.92, N 7.87, S 2.25; found: C 63.51, H 7.55, N 8.44, S 2.68.

Synthesis of 7

A solution of compound 1a (0.200 g, 0.144 mmol) and benzophenone (Ph₂C = O, 0.052 g, 0.287 mmol) in diethyl ether (Et₂O, 5.0 mL) was prepared at room temperature. The reaction mixture underwent a color change from blue to orange-red, accompanied by the formation of yellow crystals. The supernatant was carefully removed using a dropper, and the crystalline residue was washed with diethyl ether (5.0 mL) and dried under vacuum, yielding compound 7 as a yellow solid (0.100 g, 44%) (Single crystals of 7 suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained from an Et2O solution). Mp: 145.0–146.5 °C (dec). 1H NMR (500 MHz, D8-THF): δ = 0.32 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 0.89 (m, 36 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.07 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 18 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.24 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.29 (m, 3 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.37 (m, 6 H, CH(CH3)2), 1.95 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.00 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.09 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.17 (s, 3 H, CH3), 3.09 (br, 4 H, CH(CH3)2), 4.11 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.02 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 5.75 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2), 6.52 (br, 2 H, Ar-H), 6.81 (br, 4 H, Ar-H), 6.93 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6 H, Ar-H), 7.00 (br, 10 H, Ar-H), 7.53 (br, 2 H, CH(CH3)2); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, D8-THF): δ = 10.0 (CCH3), 10.46 (CCH3), 10.5 (CCH3), 10.8 (CCH3), 20.6 (CH(CH3)2), 21.15 (CH(CH3)2), 21.2 (CH(CH3)2), 21.4 (CH(CH3)2), 21.9 (CH(CH3)2), 23.0 (CH(CH3)2), 25.5 (CH(CH3)2), 26.5 (CH(CH3)2), 28.7 (CH(CH3)2), 28.8 (CH(CH3)2), 51.7 (CH(CH3)2), 53.1 (CH(CH3)2), 122.0, 123.1, 123.2, 123.5, 124.5, 124.7, 124.8, 126.3, 126.9, 127.2, 127.5, 127.6, 130.7, 145.7 (Ar-C), 146.0 (Ar-C), 146.3 (Ar-C), 172.0 (NCN), 172.2 (NCN); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C87H122Ga4N8O: 1571.6838 [(M + H)]+; found: 1571.6827; Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C87H122Ga4N8O: C 66.35, H 7.81, N 7.12, O 1.02; found: C 66.85, H 8.45, N 7.64, O 1.57.

Computational methods

All theoretical calculations were carried out at the M06-2X/6-311 G(d,p) level of theory. To assess the reliability of the M06-2X functional for Ga-rich systems, we performed two benchmarks: (i) comparison of optimized geometries with crystallographic data (Supplementary Fig. S9 and Table S5), and (ii) comparison of relative energies with higher-level DLPNO-CCSD(T)56 single-point calculations (Supplementary Table S24). The benchmarking results confirm that M06-2X reliably describes the geometries and energetics of Ga-rich systems.

All wavefunction analyses and TD-DFT calculations were based on the gas-phase optimized geometries. Spin density, WBI, and QTAIM analyses were performed using the Multiwfn 3.8 (dev) program30,57, and the NBO analyses were carried out with NBO 7.058.

In the computational analysis of the reaction mechanism, geometries of all intermediates were fully optimized in the gas phase using Gaussian 16 C.01 program package. Approximate transition states (TS1 and TS2) were obtained from climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB)59 calculations using ORCA 6.060. Although the CI-NEB runs converged, subsequent eigenvector-following optimizations in both ORCA and Gaussian did not yield genuine first-order saddle points. Consequently, the highest-energy climbing images were taken as approximate transition states. To account for solvation, single-point electronic energies were computed on the gas-phase optimized geometries using the IEFPCM implicit solvation model (toluene).

Data availability

All data are also available from corresponding authors upon request. Supplementary Information is including further details of experimental procedures, crystallographic information, UV−vis spectra and DFT calculations. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2291195-2291196 and 2443687-2443692. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (fax:+44 1223 336033; deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

References

Hill, M. S. in Metal-Metal Bonding Ch. 3 (Springer, 2010).

Pau, J., Lough, A. J., Wylie, R. S., Gossage, R. A. & Foucher, D. A. Proof of concept studies directed towards designed molecular wires: property-driven synthesis of air and moisture-stable polystannanes. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 14367–14374 (2017).

Dhindsa, J. S., Jacobs, B. F., Lough, A. J. & Foucher, D. A. Push–push and push–pull” polystannanes. Dalton Trans. 47, 14094–14100 (2018).

Vidal, F. & Jäkle, F. Functional polymeric materials based on main-group elements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5846–5870 (2019).

Riley, R. D. et al. Heavy metals make a chain: a catenated bismuth compound. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 7711–7719 (2020).

Berry, J. F. & Lu, C. C. Metal–metal bonds: from fundamentals to applications. Inorg. Chem. 56, 7577–7581 (2017).

Poineau, F., Sattelberger, A. P., Lu, E. & Liddle, S. T. Molecular Metal-Metal Bonds: Compounds, Synthesis, Properties Ch. 7 (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., 2015).

Jacobsen, H. & Ziegler, T. Nonclassical double bonds in ethylene analogs: influence of Pauli repulsion on trans bending and π-bond strength. A density functional study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 3667–3679 (1994).

Power, P. P. An update on multiple bonding between heavier main group elements: the importance of pauli repulsion, charge-shift character, and london dispersion force effects. Organometallics 39, 4127–4138 (2020).

Caise, A. et al. Controlling catenation in germanium(I) chemistry through hemilability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 15606–15612 (2021).

Caise, A. et al. Controlling oxidative addition and reductive elimination at tin(I) via hemi-lability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114926 (2022).

Spinnato, D. et al. A trimetallic bismuth(I)-based allyl cation. Nat. Chem. 17, 265–270 (2025).

Caise, A., Griffin, L. P., McManus, C., Heilmann, A. & Aldridge, S. Reversible uptake of CO2 by pincer ligand supported dimetallynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202117496 (2022).

Schnepf, A., Doriat, C., Möllhausen, E. & Schnöckel, H. A simple synthesis for donor-stabilized Ga2I4 and Ga3I5 species and the X-ray crystal structure of Ga3I5·3PEt3. Chem. Commun. 21, 2111–2112 (1997).

Hill, M. S., Hitchcock, P. B. & Pongtavornpinyo, R. A linear homocatenated compound containing six indium centers. Science 311, 1904–1907 (2006).

Zessin, T., Anton, J. & Linti, G. Synthese und struktur von N,N’-diisopropylamidinat-substituierten oligogallanen GanRnI2 (n ≤ 4). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 639, 2224–2232 (2013).

Green, S. P., Jones, C. & Stasch, A. “Dissolution” of indium(I) Iodide: synthesis and structural characterization of the neutral indium sub-halide cluster complex [In6I8(tmeda)4]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 8618–8621 (2007).

Dhara, D. et al. A discrete trialane with a near-linear Al3 axis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 33536–33542 (2024).

Feng, Z. et al. Stable radical cation and dication of an N-heterocyclic carbene stabilized digallene: synthesis, characterization and reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6769–6774 (2020).

Hardman, N. J., Wright, R. J., Phillips, A. D. & Power, P. P. Synthesis and characterization of the neutral “Digallene” Ar’ GaGaAr’ and its reduction to Na2Ar’GaGaAr’ (Ar’ = 2,6-Dipp2C6H3, Dipp = 2,6-iPr2C6H3). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2842–2844 (2002).

Li, X.-W., Pennington, W. T. & Robinson, G. H. Metallic system with aromatic character, synthesis and molecular structure of Na2[[(2,4,6-Me3C6H2)2C6H3]Ga]3 the first cyclogallane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 7578–7579 (1995).

Twamley, B. & Power, P. P. Synthesis of the square-planar gallium species K2[Ga4(C6H3-2,6-Trip2)2] (Trip = C6H2-2,4,6-iPr3): The role of aryl–alkali metal ion interactions in the structure of gallium clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 3500–3503 (2000).

Barthélemy, A., Scherer, H., Weller, H. & Krossing, I. How long are Ga⇆Ga double bonds and Ga–Ga single bonds in dicationic gallium dimers? Chem. Commun. 59, 1353–1356 (2023).

Barthélemy, A., Scherer, H., Daub, M., Bugnet, A. & Krossing, I. Structures, bonding analyses and reactivity of a dicationic digallene and diindene mimicking trans-bent ditetrylenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311648 (2023).

Jones, C., Mills, D. P. & Rose, R. P. Oxidative addition of an imidazolium cation to an anionic gallium(I) N-heterocyclic carbene analogue: synthesis and characterisation of novel gallium hydride complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 691, 3060–3064 (2006).

Protchenko, A. V. et al. Stable GaX2, InX2 and TlX2 radicals. Nat. Chem. 6, 315–319 (2014).

Siddiqui, M. M. et al. Cyclic (Alkyl)(Amino)carbene-stabilized aluminum and gallium radicals based on amidinate scaffolds. Inorg. Chem. 59, 11253–11258 (2020).

Li, B. et al. Synthesis and redox activity of carbene-coordinated group 13 metal radicals. Chem. Commun. 58, 4372–4375 (2022).

Bader, R. F. W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 18, 9–15 (1985).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Kerridge, A. Quantification of f-element covalency through analysis of the electron density: insights from simulation. Chem. Commun. 53, 6685–6695 (2017).

Yang, H., Boulet, P. & Record, M.-C. A rapid method for analyzing the chemical bond from energy densities calculations at the bond critical point. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1178, 112784 (2020).

Baker, R. J., Farley, R. D., Jones, C., Kloth, M. & Murphy, D. M. The reactivity of diazabutadienes toward low oxidation state Group 13 iodides and the synthesis of a new gallium(I) carbene analogue. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 20, 3844–3850 (2002).

Jones, C., Junk, P. C., Platts, J. A. & Stasch, A. Four-membered group 13 metal(I) N-heterocyclic carbene analogues: synthesis, characterization, and theoretical studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2206–2207 (2006).

Kysliak, O., Görls, H. & Kretschmer, R. Salt metathesis as an alternative approach to access aluminium(I) and gallium(I) β-diketiminates. Dalton Trans. 49, 6377–6383 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. N-Heterocyclic imine-based bis-gallium(I) carbene analogs featuring a four-membered Ga2N2 ring. Dalton Trans. 52, 12454–12460 (2023).

Baker, R. J., Bettentrup, H. & Jones, C. The reactivity of primary and secondary amines, secondary phosphanes and N-heterocyclic carbenes towards group-13 metal(I) halides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 2446–2451 (2003).

Ball, G. E., Cole, M. L. & McKay, A. I. Low valent and hydride complexes of NHC coordinated gallium and indium. Dalton Trans. 41, 946–952 (2012).

Schuster, J. K., Muessig, J. H., Dewhurst, R. D. & Braunschweig, H. Reactions of digallanes with p- and d-block lewis bases: adducts, Bis(gallyl) complexes, and naked Ga+ as ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 9692–9697 (2018).

Uhl, W. et al. The insertion of chalcogen atoms into Al-Al and Ga-Ga bonds: monomeric compounds with Al-Se-Al, Ga-S-Ga and Ga-Se-Ga groups. Polyhedron 15, 3987–3992 (1996).

Iwamoto, T., Sato, K., Ishida, S., Kabuto, C. & Kira, M. Synthesis, properties, and reactions of a series of stable dialkyl-substituted silicon−chalcogen doubly bonded compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16914–16920 (2006).

Chu, T., Vyboishchikov, S. F., Gabidullin, B. & Nikonov, G. I. Oxidative cleavage of C=S and P=S bonds at an ali center: preparation of terminally bound aluminum sulfides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13306–13311 (2016).

Burnett, S. et al. Low-coordinate magnesium sulfide and selenide complexes. Inorg. Chem. 62, 16443–16450 (2023).

Ding, T., Nakano, R. & Yamashita, M. Base-stabilized gallium sulfides and selenides supported by a bis(oxazolinyl)(phenyl)methanide ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202401665 (2024).

He, G., Shynkaruk, O., Lui, M. W. & Rivard, E. Small inorganic rings in the 21st century: from fleeting intermediates to novel isolable entities. Chem. Rev. 114, 7815–7880 (2014).

Yan, C. & Kinjo, R. Three-membered aluminacycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12967–12986 (2023).

Hardman, N. J. & Power, P. P. Dimeric gallium oxide and sulfide species stabilized by a sterically encumbered β-diketiminate ligand. Inorg. Chem. 40, 2474–2475 (2001).

Zhu, Z. et al. Chalcogenide/chalcogenolate structural isomers of organo group 13 element derivatives: reactions of the dimetallenes Ar’MMAr’ (Ar’ = C6H3-2,6-(C6H3-2,6-Pri2)2; M = Ga or In) with N2O or S8 To Give (Ar’MIIIE)2 (E = O or S) and the synthesis and characterization of [Ar’EMI]2 (M = In or Tl; E = O, S). Organometallics 28, 2512–2519 (2009).

Weetman, C., Bag, P., Szilvási, T., Jandl, C. & Inoue, S. CO2 fixation and catalytic reduction by a neutral aluminum double bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 10961–10965 (2019).

Chen, M. et al. A silylene-stabilized germanium analogue of alkynylaluminum. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204495 (2022).

García-Romero, Á, Fernández, I. & Goicoechea, J. M. Stepwise acetylene insertion and ammonia activation at a digallene and diindene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202509661 (2025).

Schwamm, R. J., Bhide, M. A., Nichol, G. S. & Cowley, M. J. Reversible addition of ethene to gallium(I) monomers and dimers. Chem. Sci. 16, 13333–13344 (2025).

Caputo, C. A., Guo, J.-D., Nagase, S., Fettinger, J. C. & Power, P. P. Reversible and irreversible higher-order cycloaddition reactions of polyolefins with a multiple-bonded heavier group 13 alkene analogue: contrasting the behavior of systems with π–π, π–π*, and π–n+ frontier molecular orbital symmetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7155–7164 (2012).

Sharma, M. K., Wölper, C., Haberhauer, G. & Schulz, S. Reversible and irreversible [2+2] cycloaddition reactions of heteroallenes to a gallaphosphene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21784–21788 (2021).

Stoll, S. & Schweiger, A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 178, 42–55 (2006).

Riplinger, C., Pinski, P., Becker, U., Valeev, E. F. & Neese, F. Sparse maps—A systematic infrastructure for reducedscaling electronic structure methods. II. Linear scaling domain based pair natural orbital coupled cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 024109 (2016).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 082503 (2024).

Glendening, E. D., Landis, C. R. & Weinhold, F. NBO 7.0: new vistas in localized and delocalized chemical bonding theory. J. Comput. Chem. 40, 2234–2241 (2019).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA Program system—version 6.0. Wires Comput. Mol. Sci. 15, e70019 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is granted by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22001053) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. LQ20B010007). We also thank Mr. J. Liu (Zhejiang University) for single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. W. conceived and designed the experiments; N. Z., B. W., W. C., S. Z., and L. L. conducted the synthesis and characterization; D. W., Z. N., and Y. W. performed the DFT calculations; W. C. carried out EPR analysis; D. W. wrote the paper and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Felipe Fantuzzi and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Wang, B., Wu, Y. et al. Synthesis, structural characterization, and reactivity of homocatenated Ga₄ complexes with unsaturated Ga–Ga=Ga–Ga chains. Nat Commun 16, 11572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67892-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67892-1