Abstract

Recent evidence highlights the significance of a new type of tumour suppressors, which are not frequently mutated but inhibited by metabolic cues in cancers. Here, we identify BATF2 as a tumour suppressor whose expression is epigenetically silenced by glutamine in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas (HNSCC). BATF2 correlates with type-I interferon and Th1 signatures in human HNSCC, with correlation coefficients even stronger than those of the positive control, STING. The phosphorylation of BATF2 at serine 227 promotes the oligomerization of STING. BATF2 deficiency or high glutamine levels result in higher oxygen consumption rates and metabolic profiles unfavorable for type-I interferon production. An isocaloric glutamine-rich diet abolishes STING-mediated effector cell expansion in tumours, weakening STING agonist-induced tumour control. Cancer cell-specific BATF2 expression promotes an Id2-centered T-cell effector signature, reduces T-cell exhaustion, and triggers spontaneous HNSCC rejection in a type-I interferon-dependent fashion. Utilizing syngeneic subcutaneous, orthotopic, and 24-week-long cigarette smoke carcinogen-induced HNSCC models, we demonstrate that host Batf2 deficiency results in increased infiltration of CD206+ myeloid cells and reduced effector CD8+ T-cells, accelerating the initiation of cancers. Overall, we reveal a tumour suppressor BATF2 whose loss is mediated by unique metabolic cues in the TME and drives cancer immune escape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The clinical success of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) proves that cancers can be separated from the normal tissue in which they arise by the immune system. The tumour mutational burden has been extensively characterized to test the hypothesis that the number of tumour-specific antigens underpins the immunogenicity of cancers. Recognizing the evidence substantiating this theory in several cancer types, some cancers with modest responses to ICI, however, harbor high mutational loads1. To understand the mechanism governing the immunogenicity of these cancers, we employed head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) as a model. Two distinct sets of etiological factors drive HNSCC initiation and both subsets contain high and similar levels of mutational burdens2. The human papillomavirus (HPV)-negative HNSCC is associated with cigarette smoke and heavy alcohol consumption. The HPV+ HNSCC often occurs in the Waldeyer’s ring, where lymphoid structures are enriched. Gleaning evidence from two large cohorts of patients with HNSCC, we found that the Stimulator of Interferon Genes (STING)–type-I interferon (IFN-I) pathway underpins the immunogenicity of HNSCC. Oncogenes, high-risk HPV and metabolic conditions can all dampen STING response3,4,5. Recent structural evidence shows that STING functions by assembling into large multimeric protein complexes6. Despite the clear delineation of the canonical STING-TANK Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1)-Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 (IRF3) signaling axis, key components in the STING complex contributing to cancer immune surveillance remain to be discovered.

Here, we show that Basic Leucine Zipper ATF-Like Transcription Factor 2 (BATF2) functions as a tumour suppressor by sustaining the fitness of STING. BATF2 is indispensable for the activation of the STING pathway and not required for cytoplasmic dsRNA-mediated IFN-I activation. BATF2 translocates to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated membranes upon STING stimulation and interacts with STING. We identify Serine 227 as a critical site for phosphorylation during BATF2 activation. High glutamine levels suppress the expression of BATF2 epigenetically and elevate oxidative phosphorylation to dampen IFN-I responses. BATF2 expression leads to IFN-I and γδ T-cell-dependent HNSCC rejection. A deficiency in BATF2 results in the expedited onset of cigarette smoke carcinogen-induced HNSCC with infiltration of increased M2-like macrophages and decreased Th1 effector cells. Using human HNSCC specimens, we show that high levels of BATF2 correlate with increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration and that glutamine metabolism is inversely correlated with BATF2-IFN-I signatures.

Results

BATF2 positively correlates with an IFN-Ihigh and effector T-cellhigh signature in patients with HNSCC

HNSCC frequently dampens the production of IFN-I through distinct mechanisms. To identify central pathways that determine HNSCC immunogenicity, we analyzed a single-cell RNA-Seq data set of human HNSCC tumour-infiltrating immune cells (PRJNA579178). After filtering out low-quality cells, we integrated 38,862 transcriptomes from HPV− HNSCC and 20,703 transcriptomes from HPV+ HNSCC. To stabilize immune cell lineage segregation, we included ~70 additional marker genes in addition to the top 3000 most differentially expressed genes to identify immune populations, as we recently reported7,8. We identified a total of 25 clusters and eight of them were significantly different from HPV− and HPV+ tumour microenvironment (TME). We developed a robust visualization tool for single-cell data sets, supervised capacity preserving mapping (supCPM), which is adept at preserving the global geometry and correlating biological distance with geographic distance8,9. We rendered the structure of cellular subsets in human HNSCC using supCPM (Fig. 1a). Clusters 10, 19 and 20 were characterized by myeloid cells expressing high levels of CXCL10, ISG15 and CD80. Notably, these clusters were also distinguished by the cells expressing high levels of BATF2 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). HPV+ TME contained fewer γδ T-cells (cluster 4), Batf3+ conventional dendritic cells type 1 (cDC1) (cluster 25), fewer mast cells (cluster 22) and fewer M1-like macrophages (clusters 10, 19 and 20) (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Because cells in clusters 10, 19 and 20 expressed high levels of IFN-I signatures, we next assessed the correlation between BATF2 and IFN-I target genes in the TME. We analyzed 520 HNSCC specimens in the TCGA database and found that the levels of BATF2 were significantly positively correlated with those of IFNB1 (ρ = 0.28, ****p < 0.0001) and IFN target genes, including MX1 (ρ = 0.66, ****p < 0.0001), ISG54 (ρ = 0.66, ****p < 0.0001), ISG15 (ρ = 0.63, ****p < 0.0001), PD-L1 (ρ = 0.54, ****p < 0.0001) and TNF (ρ = 0.23, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Notably, the Spearman coefficients noted in these correlations were even stronger than those for STING in the same data set4. We deconvolved the immune subsets in this data set using a robust cellular deconvolution tool, FARDEEP10. We found that the expression levels of BATF2 were significantly positively correlated with the abundance of CD8+ T-cells (ρ = 0.39, ****p < 0.0001), CD4+ memory T-cells (ρ = 0.53, ****p < 0.0001), γδ T-cells (ρ = 0.29, ****p < 0.0001) and M1-like macrophages (ρ = 0.38, ****p < 0.0001). The expression levels of BATF2 were significantly negatively correlated with the abundance of regulatory T-cells (ρ = −0.27, ****p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1d).

a A supCPM rendering of 38,862 transcriptomes from HPV− HNSCC and 20,703 transcriptomes from HPV+ HNSCC is shown. The significantly altered clusters between the two groups are highlighted in red. b Scatter plots for the correlation between the expression levels of BATF2 and those of IFNB1, MX1 and ISG54 in n = 520 HNSCC specimens from the TCGA database are shown. c The correlation between the expression levels of BATF2 and TIL subsets deconvolved by FARDEEP in HNSCC specimens (n = 520) from the TCGA database is shown. d, e After filtering out suboptimal cores, cores from 200 patients with HNSCC were included for BATF2 staining scoring. Correlations between HNSCC-specific/TME-specific BATF2 and CD8 staining scores are shown. f, g Paired specimens from five patients who progressed from OPMD to oral squamous cell carcinoma were stained for BATF2, whose staining was quantified using ImageJ (n = 22 ROI for OPMD, n = 24 ROI for HNSCC; data are presented as mean ± SEM; unpaired two-tailed t-test). h, i A portion of each human oral squamous cell carcinoma specimen was used to prepare TMA for BATF2 staining, while the remaining tissue was injected with CDA for qPCR quantification of the IFNB1/PTPRC ratio (n = 8). Spearman correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between BATF2 staining scores and the IFNB1/PTPRC ratio. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. Data in (b, c, e and i) were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation test (****P < 0.0001). Scale bars in (d, f and h) represent 100 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To validate the key findings, we stained a human HNSCC tissue microarray (TMA) consisting of 677 cores from 258 patients with a median follow-up of 60.1 months. After removing suboptimal cores, we had cores from 200 patients whose demographic characteristics are summarized (Supplementary Data 1). BATF2 showed a broad range of staining intensity in tumour cells and stroma. HNSCC-specific and TME-specific BATF2 staining scores were both positively correlated with CD8 scores (Fig. 1d, e). Next, we analyzed five TCGA data sets, including HNSCC (n = 522, *p = 0.034), high-grade serous carcinoma (OV, n = 303, *p = 0.0181), sarcoma (SARC, n = 260, *p = 0.0208), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM, n = 471, **p = 0.00106), and stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD, n = 415, *p = 0.0428), and found that higher expression levels of BATF2 were positively correlated with patient outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 1e–i). To assess the role of BATF2 in suppressing tumour initiation, we next analyzed a group of patients with oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMD) specimens with confirmed malignant transformation (Supplementary Data 2). We performed BATF2 staining on the paired longitudinal specimens and found that BATF2 expression levels were lower in paired HNSCC than in OPMD (Fig. 1f, g). Next, to directly assess whether the expression levels of BATF2 in fresh HNSCC regulate their response to IFN agonists, we analyzed fresh human HNSCC from eight patients. We trisected the tissue into three pieces of comparable size. The first piece was injected with PBS ex vivo, the second piece was injected with 5.0 μg CDA, and the third piece was formalin fixed and integrated into a tissue microarray (Fig. 1h). We performed qPCR using tissue homogenates and normalized the levels of IFNB1 by PTPRC, the latter of which encodes CD45. We quantified BATF2 staining using ImageJ and generated BATF2 scores. Then, we performed a Spearman correlation analysis between BATF2 scores and normalized IFNB1 expression and identified a strong positive correlation with a ρ-value of 0.86 (**p < 0.01) (Fig. 1i). The HNSCC TCGA data set does not have responder status for immunotherapy. Thus, we next examined four data sets that contained responder status to anti-PD111. We found that the responders among patients with STAD (****p < 0.0001), SKCM (****p < 0.0001), bladder squamous cell carcinoma (BLCA, *p = 0.02), or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, ****p < 0.0001) showed significantly higher levels of BATF2 expression than non-responders (Supplementary Fig. 1j–m). Overall, these data show that BATF2 inhibits the initiation of HNSCC and promotes anti-tumour immunity in human specimens.

BATF2 controls cytoplasmic DNA-mediated IFN-I response in macrophages

Because of the strong correlation between BATF2 and IFN-I signatures in the TME of HNSCC, we generated littermate control wildtype and Batf2−/− mice and validated the expression of Batf2 in bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) (Fig. 2a). We transfected the cells with a STING agonist, interferon-stimulatory DNA (ISD), or poly(I:C), which activates the cytoplasmic dsRNA-sensing mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) pathway. Then, we performed bulk RNA-Seq to compare the transcriptomes between wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM at baseline and stimulated conditions. We found that ISD and poly(I:C) induced potent IFN-I activation, with the upregulation of 13 Ifna subtypes, Ifnb1, Sting and Tnf. The absence of Batf2 lead to dampened IFN-I activation in response to ISD. However, Batf2−/− BMDM showed comparable IFN-I production when transfected with poly(I:C) (Fig. 2b). Notably, the expression levels of Arg1 and Mrc1 were suppressed when IFN-I was activated. The deletion of Batf2 resulted in elevated levels of Arg1 and Mrc1 at baseline and ISD-stimulated conditions. No apparent difference in the expression of Arg1 or Mrc1 was noted when cells were transfected with poly(I:C) (Fig. 2b). Then, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and identified the most significantly altered pathways between wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM when stimulated with ISD. The top five enriched pathways were cytokine receptor signaling, RNA splicing, unfolded protein binding, defense response and response to virus (Fig. 2c). To validate these findings, we performed qPCR to assess the mRNA abundance of Ifnb1, pan-Ifna, Cxcl10 in wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM treated with two STING agonists, ISD or 2′3′-Cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP). We found that the deletion of Batf2 significantly reduced the transcription of IFN-I signature genes (Fig. 2d, e). In contrast, when the wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM were transfected with MAVS agonists poly(I:C) or 5′ppp-dsRNA, both stimuli induced potent IFN-I pathway activation. However, there was no difference between the wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM (Fig. 2f, g).

a We confirmed the establishment of Batf2-targeted deletion in mice (left panel). The mRNA levels of Batf2 in BMDM from indicated genotypes are shown (right panel, n = 3 biologically independent samples; data are presented as mean ± SEM; unpaired two-tailed t-test). b BMDM were transfected with 2.0 µg/mL ISD and 1.0 µg/mL poly(I:C) for 8 h, and total mRNA was extracted for bulk RNA sequencing. The transcriptomes were compared between wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM. Data represent biologically independent samples (n = 2 per group). c GSEA shows the significantly altered pathways between wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM in response to STING stimulation. d–g BMDM from wildtype and Batf2−/− mice were transfected with 3.0 µg/mL ISD (d), 1.0 µg/mL cGAMP (e), 1.0 µg/mL poly(I:C) (f) or 1.0 µg/mL 5′ppp-dsRNA (g) for 16 h. Total mRNA was extracted for qPCR. The fold changes of Ifnb1, pan-Ifna and Cxcl10 are shown as indicated. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3). h, i Wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM were transfected with 3.0 µg/mL ISD (h) or 1.0 µg/mL cGAMP (i) for 24 h. The concentration of Ifn-β in the supernatant was measured by ELISA. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3). j Wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM were incubated with 10.0 µg/mL diABZI for 8 h. Ifn-β in the supernatant was measured by ELISA. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3). k, l Wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM were transfected with 1.0 µg/mL poly(I:C) (k) or 1.0 µg/mL 5′ppp-dsRNA (l) for 24 h. Ifn-β in the supernatant was quantified by ELISA. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3). m, n Wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM were transfected with 3.0 µg/mL ISD (m) or 1.0 µg/mL cGAMP (n). Cell lysates were collected at the indicated time points for immunoblot analysis. The experiment was performed in two biologically independent experiments. Comparisons in (d–l) were made using two-way ANOVA followed by multi-comparison tests and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To substantiate the findings, we performed ELISA to measure the protein concentration of Ifn-β in the supernatant. ISD transfection resulted in about 20 ng/ml Ifn-β release by the wildtype BMDM. ISD-induced Batf2−/− BMDM produced less than 10 ng/ml of Ifn-β in the supernatant (Fig. 2h). Similarly, a defect in Batf2 almost abrogated cGAMP-mediated Ifn-β production (Fig. 2i). We also noted a significant yet less prominent reduction in Ifn-β production from the Batf2−/− BMDM when the cells were incubated with a non-nucleotide-based STING agonist, diABZI (Fig. 2j). In contrast, Batf2−/− BMDM were equally competent as the wildtype control cells in producing Ifn-β when transfected with poly(I:C) or 5′ppp-dsRNA (Fig. 2k, l). Similar results were observed when we measured the protein levels of Tnf-α (Supplementary Fig. 2a–e), showing the selectivity of Batf2 in regulating IFN-I pathways. Then, we sought to characterize the signaling events downstream of Batf2. Transfection with ISD resulted in the phosphorylation of Tbk1, Irf3, Sting and Stat1 as early as 4 hrs post-treatment in wildtype BMDM. Batf2 deficiency resulted in substantial repression of these key signaling events, abrogating the phosphorylation of Irf3 (Fig. 2m). Similarly, Batf2−/− BMDM exhibited lower levels of phosphorylation of Tbk1, Irf3, Sting and Stat1 when transfected with cGAMP (Fig. 2n). In contrast, no difference in signaling was noted between wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM when they were challenged with MAVS agonists (Supplementary Fig. 2f, g). These findings suggest that BATF2 selectively engages STING to maintain the optimal levels of IFN-I production.

BATF2 promotes STING signaling in HNSCC cells

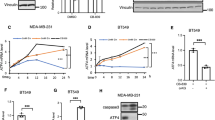

Because BATF2 is highly expressed by myeloid cells and epithelial cells, we performed a screen of a panel of HNC cell lines. FaDu and UMSCC22A cells express low levels of BATF2, while UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 express high endogenous levels of BATF2 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). First, we generated empty vector (EV) control and stable BATF2-expressing FaDu cells using retroviruses. We transfected EV control or BATF2-expressing FaDu cells with STING plasmid and found that BATF2 significantly promoted the transcription of IFN-I signature genes, including IFNB1, CXCL10, CXCL9 and ISG54 (Fig. 3a). This finding was also recapitulated in UMSCC22A cells (Fig. 3b). Although most HNSCC cells, including FaDu and UMSCC22A, do not show robust IFN-I activation when transfected with cGAMP4,5, we found that BATF2 could still enhance the IFN-I response (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). During tumour initiation, when immune surveillance determines the outcomes of epithelial transformation, the proper activation of the innate immune pathways enables the maturation of antigen-presenting cells and subsequent cross-priming of T-cells. To evaluate whether BATF2 helps to launch the IFN-I pathway against epithelial malignant transformation, we expressed BATF2 in NOM9-TK normal oral keratinocytes, which directly triggered the phosphorylation of TBK1 and STING (Supplementary Fig. 3d). To substantiate the findings, we generated EV and BATF2-deficient UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 cells using CRISPR-Cas9 lentiviruses. In agreement, BATF2 deficiency in UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 cells significantly reduced STING-mediated IFN-I signature gene expression (Fig. 3c, d). Then, we examined signaling alteration by immunoblotting phosphorylation of TBK1 and STING in HNSCC cells. The expression of BATF2 substantially increased the activation markers of the STING pathway (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 3e). BATF2 was STING-inducible, and BATF2 depletion resulted in compromised STING activation in UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 cells (Fig. 3f).

a, b FaDu and UMSCC22A cells were transduced with empty vector (EV) or pMXs-BATF2-2HA retrovirus to generate stable BATF2 overexpression HNSCC cell lines. The cells were transfected with 1.0 µg/mL STING plasmid for 16 h. Total mRNA was collected for qPCR quantification of IFN-I signature genes. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3). c, d UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 cells were transduced with EV or CRISPR-Cas9 lentiviruses and then selected using 10 µg/mL puromycin to obtain stable cell lines. The EV control and BATF2−/− cells were transfected with 1.0 µg/mL STING plasmid for 16 h. Total mRNA was collected for qPCR quantification of IFN-I signature genes. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3). e EV and BATF2-expressing FaDu and UMSCC22A cells were transfected with 1.0 µg/mL STING plasmid for 24 h. The protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting of the indicated markers. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 2). f EV and BATF2−/− UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 cells were transfected with 1.0 µg/mL STING plasmid for 24 h. The protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting of the indicated markers. Data represent biologically independent experiments (n = 2). Comparisons in (a–d) were made using two-way ANOVA followed by multi-comparison tests and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

BATF2 translocates to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to interact with STING

To characterize the staining pattern of BATF2 in the TME, we performed an immunohistochemical stain of human HNSCC specimens with an anti-BATF2 antibody. Among the BATF2+ HNSCC cases, BATF2 shows a perinuclear punctate staining pattern, which can be seen in proteins localized to ER or Golgi apparatus, in addition to nuclear staining (Fig. 4a). Thus, we performed a sucrose gradient to fractionate cytosol, nuclei and ER as reported12,13,14. We found that STING was enriched in the ER compartment and not identified in free cytosol, as expected. BATF2 was present in the cytosol and at a lower level in the ER in the resting state. When THP-1 cells were treated with cGAMP overnight, there was a substantial translocation of BATF2 into the ER (Fig. 4b). We also identified phosphorylated TBK1 and IRF3, two central STING signaling molecules enriched in the ER fraction when the cells were treated with cGAMP. Consistent with the transcription factor function, phosphorylated IRF3 was most highly enriched in the nuclei fraction. As controls, VDAC, a mitochondrial protein was largely absent in the ER and cytosol fractions. Lamin B1 (LMNB1) is a component of the nuclear lamina and was enriched in the nuclear fraction, as expected (Fig. 4b). To visualize the localization of BATF2, we performed a confocal imaging analysis of BATF2. We co-stained HNSCC cells with STING and MitoTracker. We noticed that BATF2 colocalized with STING but not with mitochondria (Fig. 4c). This prompted us to directly assess BATF2-STING interaction using biochemical methods. We pulled down STING under stringent buffer conditions and identified a strong interaction with BATF2 in HEK-293T cells (Fig. 4d), a model cell line free of oncogenic mutations that often interfere with the STING-IFN-I pathway. Similarly, we pulled down BATF2 and identified STING as a binding partner (Fig. 4e). Then, we performed co-immunoprecipitation in FaDu and RAW 264.7 cells and found that BATF2 interacted with STING strongly (Fig. 4f–h). To further investigate which domain of STING specifically interacts with BATF2, we deleted the N-terminus, the Ligand-Binding Domain, or the C-terminus of STING. All STING domain truncation mutants can be expressed. We immunoprecipitated BATF2 and found that only the LBD domain was required for the BATF2-STING interaction (Fig. 4i). LBD is also the domain critical for STING oligomerization15. Thus, it is likely that the BATF2-STING interaction stabilizes the STING oligomers in an LBD-dependent fashion.

a Human HNSCC (n = 2) FFPE slides were stained with an antibody against BATF2. b THP-1 cells were incubated with 10 µg/mL cGAMP mixed with human albumin at 1:1 ratio overnight. The nuclei, cytosol and ER-associated membrane components were obtained by sucrose gradient centrifugation. Immunoblotting was performed for proteins as shown. c UMSCC22A-BATF2 cells were transfected with 0.08 µg/well FLAG-STING plasmids and 0.35 µg/well cGAMP for 16 h. The staining pattern of STING, BATF2 and mitochondria was evaluated using confocal microscopy (scale bar: 5.0 μm). d–g HEK-293T and FaDu cells were co-transfected with 1.0 µg/mL BATF2-HA and 1.0 µg/mL FLAG-STING plasmids for 24 h. Reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation of BATF2 and STING was performed. h co-IP was performed to verify the interaction between Sting and Batf2 in RAW246.7 cells. i HEK-293T cells were transfected with 1.0 μg/mL BATF2-HA and 1.0 μg/mL FLAG-tagged STING truncation mutant plasmids for 24 h. Co-IP was performed to examine the interaction between BATF2 and STING truncation mutants. j Wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM were transfected with 3.0 µg/mL ISD for 0, 2, 4 and 8 h. Protein lysates were resolved using native PAGE and then immunoblotted to assess the oligomerization of STING. k A cartoon shows the domain structure of BATF2. The phosphorylation sites were predicted using PhosphoSitePlus. l THP-1 cells were incubated with 10 µg/mL cGAMP admixed with human albumin overnight. Protein lysates from the control and treated groups were resolved using phos-tag gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted to assess the phosphorylation of BATF2 and IRF3. The protein samples from the same experiment were also subjected to SDS-PAGE as another control. m Batf2−/− bone marrow cells were transduced with full-length or 179 A or 227 A BATF2 mutant retroviruses and differentiated into BMDM, which were then transfected with 2.0 µg/mL ISD for 8 h. The protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted against the indicated markers. The experiments in (b, c, h–j and l) were performed in two biologically independent experiments. The experiments in (d–g and m) were performed in three biologically independent experiments.

To directly assess whether BATF2-mediated IFN-I activation is STING-dependent, we depleted STING in Batf2-expressing tumour cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Batf2 significantly increased the transcription levels of Ifnb1, Isg54 and Cxcl9 in response to transfection of 1.0 μg/mL ISD. Sting deficiency abrogated Batf2-driven IFN-I activation (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d). Similarly, Batf2 expression directly increased the transcription levels of Ifnb1, Pan-Ifna and Cxcl10 in wild-type BMDM, which was abrogated in Sting−/− BMDM (Supplementary Fig. 4e–g). These results substantiate the BATF2-STING-IFN-I signaling pathway.

Phosphorylation of BATF2 is essential for its function in supporting STING signaling

Because the activation of STING depends on its oligomerization into a higher-order molecular complex15 and BATF2 binds to the STING LBD domain essential for oligomerization, we sought to determine whether BATF2 was involved in the STING complex formation under native conditions. We stimulated wildtype and Batf2−/− BMDM with ISD and performed native gel electrophoresis. We found that the STING oligomers started to form as early as 4 h post-transfection and became prominent at the 8-h time point. Batf2 depletion substantially repressed the oligomerization of STING (Fig. 4j). The oligomerization of STING promotes its phosphorylation and downstream signaling. Then, we investigated whether BATF2 was phosphorylated during STING activation. Using PhosphoSitePlus, we found that there were two predicted phosphorylation sites for Batf2 at serine 179 and serine 227 (Fig. 4k). Then, we set out to determine whether Batf2 is phosphorylated upon STING stimulation. Because there is no phosphorylation-specific antibody available for Batf2 yet, we ran a phos-tag gel to determine whether the protein was phosphorylated. THP-1 cells were incubated with cGAMP admixed with human albumin, and we found that BATF2 was indeed phosphorylated upon stimulation. IRF3 was also immunoblotted using phos-tag gel as a positive control (Fig. 4l). To determine which phosphorylation site is indispensable for Batf2’s function in regulating STING, we performed a reconstitution experiment where we transfected full-length and site-specific mutant Batf2 plasmids to Batf2−/− BMDM. We treated wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM, in the absence or presence of reconstitution, with ISD. In agreement with Fig. 2m, Batf2 deficiency suppressed STING signaling. Reconstituting the Batf2−/− BMDM with wild-type Batf2 or Batf2-179A mutant, the latter of which contained a serine to alanine mutation and cannot be phosphorylated at 179S, restored STING signaling. In contrast, reconstitution with the Batf2-227A mutant failed to restore signaling, suggesting that the phosphorylation of the 227 serine residue of Batf2 is essential for its function (Fig. 4m). To confirm whether S227 is also essential for BATF2 activation in cancer cells, we expressed wild-type BATF2 and BATF2-227A mutant in the human UMSCC22A cell line. We found that the full-length BATF2 substantially enhanced cGAMP-mediated STING activation, which was abolished by mutating S227 to an alanine (Supplementary Fig. 4h).

Glutamine inhibits the STING-IFN-I pathway by suppressing the expression of BATF2

By examining the TCGA data set, the loss of BATF2 at the genetic level is uncommon. We next sought to investigate the mechanism underpinning the suppression of BATF2 expression in the TME. First, we tested BATF2 expression in nutrient-defined media specifically deficient for one of the essential or non-essential amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We found that deficiency in glutamine, tyrosine, valine, isoleucine and methionine resulted in significantly elevated expression of BATF2 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Recent evidence suggests that glutamine is a central anaplerotic nutrient sustaining the tricarboxylic acid cycle in cancers. Inhibition of glutamine metabolism inhibits the generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) and suppresses tumour growth16. Conceptually in agreement, glutaminolysis is pivotal for alternative (M2-like) activation of macrophages17. In addition to immune cells, cancer cells show an even higher ability to uptake glutamine in the TME18. Because the lack of IFN-I signaling in the TME leads to MDSC expansion and M2-like differentiation, we next sought to determine whether glutamine inhibits STING-mediated IFN-I activation. We cultured BMDM in glutamine-free media, media with 0.5 g/L glutamine, i.e., at the concentration of regular complete media, and media with 5.0 g/L glutamine. Transfection of BMDM with cGAMP resulted in significantly increased transcription of Batf2 and IFN-I genes. Higher levels of glutamine significantly repressed cGAMP-induced expression of Batf2, Ifnb1 and pan-Ifna (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Similarly, we transfected BMDM with ISD and found that glutamine significantly suppressed the STING-induced expression of Batf2 and IFN-I signature genes (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5d–g). Treatment of cGAMP-activated BMDM with a selective glutaminase inhibitor, Bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES), significantly elevated the expression levels of Batf2, Ifnb1 and pan-Ifna in media containing either 0.5 g/L or 5.0 g/L glutamine (Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Fig. 5h, i). To substantiate the findings, we measured the protein levels of Ifn-β (Fig. 5e, f), Tnf-α (Supplementary Fig. 5j, k) and Cxcl10 (Supplementary Fig. 5l) in the supernatant and recapitulated the findings using qPCR. We harvested the cells and performed immunoblotting of STING signaling markers. The addition of glutamine dampened the phosphorylation of Tbk1, Sting and Irf3 (Fig. 5g). Similarly, in THP-1 cells, we found that 0.5 g/L and 5 g/L glutamine suppressed the transcriptional expression of BATF2 and IFN-I target genes (Supplementary Fig. 6a). At the protein level, high concentrations of glutamine not only reduced BATF2 expression but also led to decreased phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3, ultimately resulting in impaired IFN-β production (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c). To confirm glutamine-mediated BATF2-IFN-I suppression also similarly occurs in cancer cells, given their high dependence on glutamine metabolism, we transfected UMSCC49 cells with 2.0 μg/mL ISD with or without glutamine in the culture media. In agreement, glutamine potently inhibited the expression of BATF2 and IFN-I target genes (Supplementary Fig. 6d). At protein levels, glutamine also inhibited the expression of BATF2, the phosphorylation of TBK1 and the phosphorylation of STING (Supplementary Fig. 6e). To determine whether glutamine-mediated IFN-I suppression depends on BATF2, we transfected Batf2−/− BMDM with ISD with or without glutamine. In contrast to wildtype BMDM, the deficiency in Batf2 abolished glutamine-driven suppression of Ifn-β production, suggesting that glutamine inhibits IFN-I in a Batf2-dependent fashion (Supplementary Fig. 6f).

a, b BMDM were cultured in media containing glutamine (0 g/L, 0.5 g/L or 5.0 g/L) for 24 h, followed by transfection with STING agonists. c, d BMDM were cultured in media containing 0.5 g/L (c) or 5 g/L (d) glutamine and transfected with cGAMP with or without of BPTES. Data are compared using one-way ANOVA. e, f Ifn-β in the supernatant from this figure (a, b) was quantified by ELISA. g BMDM were cultured in media containing varied levels of glutamine and then transfected with cGAMP. The protein lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. Data represent two biologically independent experiments. h BMDM were cultured in media containing varied levels of glutamine and transfected with ISD. ChIP analysis of the H3K27me3 mark in the promoter regions of Batf2 is compared using one-way ANOVA. i BMDM were cultured in media containing 0 g/L or 5.0 g/L glutamine for 24 h and transfected with ISD and OCR was compared. j Wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM were transfected with ISD and OCR was compared. k Female C57BL6/J mice on a control diet or glutamine-rich diet were implanted with NOOC1 cells subcutaneously. Mice were treated with PBS or c-di-AMP intratumoural injection (n = 8). l, m The combination of CDA and JHU-083 was administered for 2 weeks (n = 8). n UMAP rendering of scRNA-Seq of the TILs separated from 5k (n = 8 mice per group), shown above is generated. o The relative cluster size change percent is shown. p The Batf2 expression level in each cluster is shown. q The expression levels of Batf2 were compared using a Wilcoxon test. r Bulk RNA-Seq was performed for 15 HNSCC specimens. A correlation analysis between BATF2-IFN-I target genes and glutamine metabolism is shown. Data in this figure (a–h) represent biologically independent experiments (n = 3, mean ± SEM). Data in this figure (i, j) were compared by an unpaired two-tailed t-test and represent biologically independent samples (n = 3, mean ± SEM). Comparisons in (a, b and e, f) were made using two-way ANOVA, followed by multi-comparison tests. The tumour growth in this figure (k–m) was compared using the generalized estimating equation (GEE) model.

To understand the mechanism underpinning glutamine-mediated suppression of BATF2, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiment to examine glutamine-mediated epigenetic regulation of Batf2 and IFN-I target genes in BMDM. We found that glutamine significantly increased the levels of a repressive marker, H3K27me3 on the promoters of Batf2, Ifnb1 and Cxcl9 (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. 6g). This glutamine-mediated epigenetic regulation was specific because glutamine had no impact on the H3K4me3 marker on the promoters of Batf2 and Ifnb1 (Supplementary Fig. 6h).

We showed that depletion of Batf2 increased the expression of marker genes for the alternatively activated macrophages, such as Arg1 and Mrc1 (Fig. 2b). STING-IFN-I signaling promotes the classical activation of macrophages, which primarily relies on aerobic glycolysis to meet the rapidly increased energy demand. In contrast, alternative activation in macrophages favors oxidative metabolism and maintains a robust glutaminolysis program. The addition of glutamine increased the basal and maximal oxygen consumption rates (OCR) at baseline and STING-induced conditions (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Although wild-type and Batf2−/− BMDM showed comparable basal and maximal OCR at baseline without immune activation, Batf2−/− BMDM demonstrated a significantly higher basal and maximal OCR than the wild-type cells under STING-induced conditions (Fig. 5j and Supplementary Fig. 7c, d), similar to the high glutamine culture conditions. To further evaluate the impact of glutamine upon STING activation in vivo, we employed an isocaloric diet model where we fed C57BL/6J mice with a control diet or a glutamine-rich diet. Mice in both groups showed comparable body weight throughout the experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7e). We implanted an aggressive HNSCC model, NOOC1, which shows ~91% similarity in mutational signatures to human tobacco-associated cancers and is refractory to ICB19, in mice on a control regular diet and an isocaloric, glutamine-enriched diet. NOOC1 grew even more aggressively in mice on the glutamine-rich diet at baseline (Fig. 5k). To assess whether glutamine-mediated tumour aggression depends on the suppression of Batf2, we implanted the same tumour model into Batf2−/− mice on either a regular diet or an isocaloric, glutamine-rich diet. We found that a glutamine-rich diet could no longer promote tumour growth in the absence of host expression of Batf2 (Supplementary Fig. 7f). For mice on a regular diet, intra-tumoural injection of STING agonists resulted in significant tumour volume reduction, as expected (Fig. 5k). However, in mice fed with a glutamine-rich diet, STING agonists failed to show any efficacy (Fig. 5k). We used a tumour volume of 500 mm³ as the cutoff point to assess mouse survival. We found that mice on a glutamine-enriched diet had significantly lower survival rates compared to those on a control diet, and CDA treatment did not improve their survival. In contrast, CDA treatment extended the survival of mice on a regular diet (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Then, we assessed the impact of inhibition of glutamine metabolism on tumour response to IFN-I agonists. In the same experiment shown in Fig. 5k, we also included two additional groups that received intra-tumoural injection of CDA and a glutaminase inhibitor, JHU083. One of these groups was on a regular diet, and the other was on an isocaloric glutamine-rich diet. Interestingly, although JHU083 did not further improve the anti-tumour efficacy of CDA in the regular diet group, it significantly improved tumour control in mice on a glutamine-rich diet (Fig. 5l, m).

To determine the mechanism of glutamine-rich diet-mediated desensitization of cancer to STING stimulation, we performed scRNA-Seq to examine changes in the TME (Fig. 5n). We utilized an optimized analytical pipeline where we included additional feature genes for lineage segregation and stabilization to identify ten main clusters7,8. In mice on a regular diet who were treated with STING agonists, we observed an increase in CXCR5+ B cells (cluster 7) and T-cells (cluster 6), along with a reduction in granulocytic MDSC infiltration (clusters 3 and 8) in the TME. In contrast, when mice were fed with an isocaloric glutamine-rich diet, intra-tumoural STING stimulation failed to increase T-cell infiltration (cluster 6) but increased the expansion of granulocytic MDSC (clusters 3 and 8). In the glutamine-rich diet group, we also observed an expansion of endothelial cells (cluster 9) and basophils (cluster 10) (Fig. 5o). To assess whether glutamine suppressed Batf2 in vivo as a mechanistic link of dampening STING-mediated anti-tumour immunity, we examined the expression levels of Batf2 and found that Batf2 was most highly expressed by tumour cells (cluster 5), Ifnb1+Cxcl10+ myeloid cells (cluster 1), MHC-II+ myeloid cells (cluster 2) and dendritic cells (cluster 4) (Fig. 5p). Notably, glutamine significantly decreased the expression of Batf2 in vivo (Fig. 5q). In the myeloid cell cluster that features high expression levels of Ifnb1 and Cxcl10, a glutamine-rich diet significantly reduced the levels of Batf2 and Ifnb1 (Supplementary Fig. 7h, i). We and others have shown that STING agonists significantly expanded the infiltration of effector and stem-like T-cells5,20,21. Thus, we sub-clustered T-cells (cluster 6) into functional subsets to better assess the impact of a glutamine-rich diet on cancer STING response (Supplementary Fig. 7j, k). In agreement with the literature, STING agonists substantially expanded intra-tumoural CD8+ T-cells (subcluster 2), NK cells (subcluster 3) and Tcf7+ T-cells (subcluster 4) in mice on a regular diet. In contrast, STING agonists failed to expand these key anti-tumour immune subsets in mice on an isocaloric glutamine-rich diet (Supplementary Fig. 7j, k). As we saw a noted B-cell expansion in response to STING stimulation only among mice on a regular diet, we next examined the B-cell signatures and found that STING stimulation is more prominently promoting the upregulation of multiple functional B-cell subset markers in tumours grown in mice on a regular diet than those grown in mice on a glutamine-rich diet, including Cr2, Fcer2a, Igkc, Ighm, Ighd, Sell, Ms4a1, Sdc1, CD79a, CD19 and Cxcr5 (Supplemental Fig. 7l). In agreement, we quantified CD20 staining of tumours from different treatment groups and found that STING stimulation expanded B-cells in the tumours grown in mice on a regular diet but not in mice on a glutamine-rich diet (Supplemental Fig. 7m). To substantiate the physiological relevance of the glutamine-BATF2 pathway, we collected fresh HNSCC tissue from 15 patients (Supplementary Data 3) and performed bulk RNA-Seq. Then, we performed a correlation analysis between BATF2-IFN-I pathway genes and glutamine metabolism markers. We found that BATF2 was strongly positively correlated with Th1 genes, including CXCL9, CXCL10, ISG15, IFNB1, OASL and TNF. Notably, we also found that BATF2 was inversely correlated with glutamine metabolism pathway genes, such as SLC7A5, SLC1A5, SLC38A2 and GLS. In agreement, the Th1 cytokines, including IFNG, IFNB1 and TNF, all show an inverse correlation with glutamine metabolism (Fig. 5r). Collectively, these findings suggest that high glutamine levels silence the expression of BATF2 by increasing the trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 protein, promoting a metabolic profile recalcitrant to STING stimulation.

HNSCC-specific BATF2 promotes IFN-I- and γδ T-cell-dependent tumour immunogenicity

The use of a cigarette smoke carcinogen, 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO), could generate tumour cells with high similarity mutational profiles to human tobacco-associated cancers, such as HNSCC19,22. Thus, we treated C57BL/6J mice with 50 μg/mL 4-NQO-containing drinking water for 16 weeks. Then, we switched the mouse cages to regular water and monitored the development of HNSCC. A histology-verified tongue squamous cell carcinoma was processed to produce single-cell clones. Every single cell-derived line was expanded and screened in C57BL6/J mice for tumour establishment. Most clones were spontaneously rejected except for two 4-NQO-induced Oral Cancer (NOOC) lines, NOOC1 and NOOC2. Similar to NOOC1, which has a combined 91% similarity in mutational signatures to human tobacco-associated cancers, NOOC2 has a combined >95% similarity in mutational signatures to human tobacco-associated cancers, including 68.1% similarity to Single Base Substitution (SBS)4 (tobacco smoking), 18.3% similarity to SBS5 (tobacco smoking), and 13.6% similarity to SBS14 (defective DNA mismatch repair) (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Common HNSCC missense mutations, such as Trp53 (R178P), Erbb2 (P1034L), Nsd1 (E1342*), Kmt2d (R5157L, R3551L, E3060K), Kdm5c (E1496*), Kdm6a (Q475H), Fgfr3 (G444S), Fat1 (Q901K), Fat1 (S1372I) and Fat1 (V2754M), were identified in NOOC2 (Supplementary Data 4). Unlike NOOC1, which is completely refractory to high doses of ICI19, NOOC2 partially responds to a combination of anti-Pd-1 and anti-Ctla4 (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

To directly assess the role of cancer cell-specific Batf2 expression in tumour immunogenicity, we first measured Batf2 expression levels in MOC2-E6/E7, NOOC1 and NOOC2 cells using qPCR and found that Batf2 expression was lowest in MOC2-E6/E7, which corresponded to the lowest transcription levels of Ifnb1 at baseline (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Then, we generated stable Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells (Supplementary Fig. 9b). We previously showed that MOC2-E6/E7 is refractory to anti-PD-L1 and partially responsive to non-formulated CDN5. Similar to human HNSCC cells shown in Fig. 3, Batf2 upregulated STING-induced transcription of IFN-I target genes and Ifn-β secretion into the supernatant (Fig. 6a, b). Batf2 expression also increased STING-induced phosphorylation of Tbk1, Irf3 and Sting in MOC2-E6/E7 cells (Fig. 6c). We did not find any differences in colony formation or proliferation between the empty vector (EV) control and Batf2-expressing cancer cells in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 9c, d). However, Batf2-expressing tumours were spontaneously rejected in wild-type C57BL6/J mice (Fig. 6d). We extracted mRNA from homogenized tumour tissues from both groups and found that the transcription levels of IFN signature genes, including Mx1, Cxcl9, Cxcl10 and Ifng were much higher in Batf2-expressing tumours (Supplementary Fig. 9e). To determine whether Batf2-mediated tumour rejection was dependent on IFN-I, we implanted EV and Batf2-expressing tumour cells in Ifnar1−/− mice and completed rescued the phenotype (Fig. 6e). To determine whether Batf2-mediated tumour rejection depends on Sting, we generated stable empty vector control and Sting-deficient Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells. We found that cancer cell-specific Batf2-mediated tumour rejection depended on cancer cell expression of Sting because knocking down Sting abrogated Batf2-mediated protection (Supplementary Fig. 9f, g). To discover the mechanism of cancer cell-specific Batf2 activation in tumour suppression, we characterized the temporal dynamics of the TME between control and Batf2-expressing tumours by analyzing TILs procured on days 7, 14 and 21 post-tumour implantation (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Batf2-expressing tumours demonstrated a more favorable TME at the earliest time point, as evidenced by the early expansion of CD45+CD3−CD11b+ myeloid cells that are positive phospho-Tbk1 and phospho-Irf3. Also noticeable at this early time point was the expansion of γδ T-cells. Then, at the later time points, Batf2-expressing tumours started to show significantly more CD8+ T-cells infiltration than control tumours, although this advantage appeared to become smaller as the tumour size continued to increase (Fig. 6f–i). These findings suggested that cancer cell-specific Batf2 expression reprograms innate and adaptive immune wiring in a stepwise fashion, with IFN-I activation in CD11b+ myeloid cells and γδ T-cells expansion as the earliest response feature, followed by expansion of CD8+ T-cells.

a, Stable EV control and Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells were transfected with Sting plasmid for 16 h. The mRNA was quantified by qPCR (n = 3). b, c EV control and Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells were transfected with Sting plasmid for 24 h. b The amount of Ifn-β in the supernatant was measured by ELISA (n = 3). c protein lysates were harvested for immunoblotting against the indicated markers. d EV or Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells were implanted subcutaneously and monitored for tumour burden in the wild-type female C57BL6/J mice (n = 5 each group). The tumour growth was compared using the GEE model. e EV or Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells were implanted in Ifnar1−/− mice (n = 9 in EV group; n = 10 in Batf2-MOC2-E6/E7 group). Tumour growth was compared using the GEE model. f–i One million the EV or Batf2-expressing MOC2-E6/E7 cells were implanted subcutaneously in wild-type mice. On days 7, 14 and 21 after implantation, tumour tissues were processed into single-cell suspensions. Flow cytometry was used to evaluate the presence of p-Tbk1+, p-Irf3+, CD8⁺ and TCRγδ⁺ cells in the TME (n = 4 in the Day 7 Batf2 and the Day 14 EV groups; n = 5 for other groups). j UMAP rendering of single-cell immune profiling of the TILs separated from the control (n = 5) and Batf2-expressing (n = 5) tumours grown in wild-type C57BL6/J mice from this figure (d) is shown. The significantly altered clusters between the two groups are labeled in red. k The relative percentage of TILs is shown. l T-cell clusters (13 + 16) were separated, and the volcano plot shows the differentially expressed genes between groups. m A gene set enrichment analysis was performed to identify the most significantly altered pathways in T-cells from this figure (d). Comparisons in (a, b) were made using two-way ANOVA followed by multi-comparison tests. Comparisons in (f–i) were made using an unpaired two-way t-test. Data in (a, b and d–i) are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided.

Then, we profiled the tumour-infiltrating immune cells at single-cell resolution. The significantly expanded clusters in the Batf2-expressing tumours included a subset of Cxcl10high myeloid cells, endothelial cells and γδ T-cells (Fig. 6j, k). To interrogate the differences in T-cell functions, we separated T-cells (clusters 13 and 16) and identified a list of genes that were differentially expressed between T-cells from EV and Batf2-expressing tumours. The T-cells in the control TME expressed high levels of exhaustion signatures such as Pdcd1, Havcr2 and Icos. In contrast, the T-cells in the TME of Batf2-expressing tumours expressed significantly higher levels of Id2 (Fig. 6l), which is indispensable for the generation of memory and effector T-cells23. Then, we performed a GSEA. We found that the pathways that were significantly upregulated in T-cells from Batf2-expressing tumours included effector functions, such as Ifn-γ response, allograft rejection, Ifn-α response, as well as cell proliferation, such as E2F targets, mitotic spindle, G2M checkpoint and Myc targets (Fig. 6m). Because we observed a significant expansion of γδ T-cells in BATF2-expressing human and murine HNSCC (Figs. 1c and 6h, j, k), we then investigated whether this population was essential for tumour immunogenicity. We implanted EV and Batf2-expressing tumours in Tcrd−/− mice and found that the lack of γδ T-cells abrogated Batf2-mediated tumour rejection, highlighting the importance of this subset in early tumour suppression (Supplementary Fig. 9h). Cxcl10 is a key target gene of Ifn-β, and Batf2 led to a significant expansion of Cxcl10⁺ myeloid cells. Thus, we evaluated whether the anti-tumoural function of BATF2 depends on Cxcl10. We administered 200 μg of anti-Cxcl10 neutralizing antibody on day 7 after Batf2-MOC2-E6/E7 tumour implantation, followed by 100 μg twice per week for a total of five dosages. We found that neutralizing Cxcl10 reversed the antitumour effect of Batf2 (Supplementary Fig. 9i). Then, we sought to determine whether Batf2-mediated protection depends on αβ effector T-cells. We administered 0.5 mg of anti-CD8 antibody intraperitoneally for three consecutive days starting three days before tumour implantation, followed by twice per week injections for a total of five doses. We found that depletion of CD8⁺ T cells abrogated Batf2-mediated protection (Supplementary Fig. 9j). To determine whether cancer cell-specific Batf2 expression has an abscopal effect, we implanted the EV control and Batf2-expressing tumours on the right flank. As expected, we observed a significant reduction in tumour volume when Batf2 was expressed. However, the EV control tumours grown in the left flank of mice that bear Batf2-expressing tumours in the right flank did not show a difference in volume compared to those EV tumours grown in the left flank of mice that bear EV tumours in the right flank (Supplementary Fig. 9k). These data suggest that the BATF2-expressing tumour activates a local immune response without triggering a notable abscopal effect.

To further support our findings, we knocked down Batf2 in NOOC2 cells, which have higher endogenous Batf2 expression levels. Depletion of Batf2 significantly reduced the production of Ifnb1 (Supplementary Fig. 9l). In agreement, sh-Batf2 NOOC2 tumours grew significantly faster than EV control tumours (Supplementary Fig. 9m). We demonstrated the role of the S227 phosphorylation site in Batf2 activation. To substantiate the physiological relevance of this finding, we established tumour models that stably express empty vector, wild-type Batf2 and 227 A mutant Batf2. In agreement with our other data, expression of Batf2 inhibited tumour growth. However, Batf2-mediated protection was abrogated by mutating serine 227 to alanine and disabling phosphorylation at this amino acid (Supplementary Fig. 9n).

BATF2 expression in the host deters the initiation of HNSCC

To understand the impact of host BATF2 signaling on the immunogenicity of HNSCC, we first implanted MOC2-E6/E7 cells into littermate control wild-type and Batf2−/− mice. We observed significantly accelerated MOC2-E6/E7 tumour growth in the Batf2−/− host (Fig. 7a). Flow cytometric analysis of the TME showed that fewer p-Irf3+, CD4+, CD8+ and CD8+Ifn-γ+ T cells were present in tumours growing in Batf2−/− mice (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 10b). Similarly, we observed fewer γδ T-cells in tumours grown in the Batf2−/− hosts (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Using another model, we implanted NOOC2 into littermate control wild-type and Batf2−/− mice and consistently found that the tumour burden was significantly higher in the Batf2−/− mice (Fig. 7c). Consistent with previous results, host deficiency in Batf2 resulted in fewer p-Irf3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells infiltration in the TME (Fig. 7d). To further substantiate the findings, we employed the third model, 4MOSC1, which only grows orthotopically in the tongue. Batf2−/− hosts developed the largest tongue tumours (Fig. 7e).

a One million MOC2-E6/E7 cells were implanted into female littermate control wild-type (n = 8) and Batf2−/− (n = 7) mice subcutaneously. b TILs were enriched by Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation and subjected to multispectral flow cytometric analysis (n = 5 for the p-Irf3+ panel; n = 8 for other panels). c Three million NOOC2 cells were implanted into female littermate control wild-type (n = 5) and Batf2−/− (n = 6) mice subcutaneously. d, p-Irf3+ cells (n = 4 in the control group; n = 7 in the Batf2−/− group), CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells (n = 6 in the control group; n = 4 in the Batf2−/− group) in the TME were quantified by flow cytometry. e One million 4MOSC1 cells in 40 μL PBS were injected into the tongues of female wild-type and Batf2−/− mice (n = 4). Tumour growth between groups shown in this figure (a, c and e) was compared using the GEE model. Comparisons in b and d were made using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. Data in (a–e) are presented as mean ± SEM. f, g Using a 4-NQO model, lesion-free survival was compared between wild-type (n = 17, 9 male and 8 female) and Batf2−/− (n = 16, 9 male and 7 female) mice using a Log-rank test (f). The characteristics of disease burden in the oral cavity were compared using the GEE model (g). h, i Multispectral imaging analysis was compared after HNSCC histology was verified. Cell phenotypes were established utilizing image features obtained from texture analysis and cell segmentation. The count of CD206+ myeloid cells (h) and the expression levels of nuclear Tbet among CD8+Tbet+ T-cells (i) were compared using a Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction. The comparison was based on whole-slide analyses of 10 tongue specimens (n = 5 per genotype). The box plots show the median (center line), 25th and 75th percentiles (bounds of the box). The whisker extends to 1.5 interquartile ranges. Scale bars represent 100 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Implantable tumour models can provide insight into the role of cancer cell-immune cell interaction in the TME, but bypass an important phase in cancer establishment – malignant transformation. HNSCC is preceded by precursor lesions known as epithelial dysplasia. Given the critical role of IFN-I in immune surveillance, we next sought to determine whether BATF2 suppresses tumour initiation using a 22-week-long carcinogen exposure model for HNSCC. The 4-NQO-induced HNSCC follows the pathological course of epithelial dysplasia transformation. We fed wildtype and Batf2−/− mice with drinking water containing 50 μg/mL 4-NQO for 16 weeks and switched to regular water afterward. We found that Batf2−/− mice showed shorter oral lesion-free survival (Fig. 7f). We started monitoring oral lesions weekly 10 weeks post-treatment start date. The oral lesions started to appear 14 weeks post-treatment initiation. We classified tumours based on their clinical measurements and found that the Batf2−/− mice showed a higher disease burden (Fig. 7g and Supplementary Fig. 10b). Notably, the deficiency in Batf2 lead to broad-field cancerization. The 4-NQO model in wild-type mice almost exclusively induces lesions in the tongue, in agreement with the literature24. We found that Batf2−/− mice were much more prone to developing tumours in the buccal mucosa and palate, in addition to the oral tongue (Supplementary Fig. 11c).

The 4-NQO model bears a high histologic resemblance to human HNSCC, with architectural disturbance, the transition between dysplastic epithelium and invasive tumour islands, keratin pearl formation, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic count, stromal complexity and variably dense inflammatory cell infiltrate (Supplementary Fig. 11d). To determine whether a Batf2 defect remodeled the infiltrating immune cell landscape, we performed spatial protein marker analyses. We first examined the percentage of different immune subsets and found that the HNSCC in the Batf2−/− hosts showed significantly increased levels of CD206+ macrophages, PD-L1+ myeloid cells, Ly6g+ MDSC, decreased levels of Tbet+CD4+ and significantly decreased expression of nuclear T-bet in CD8+ T-cells (Fig. 7h, i and Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). To map the intercellular relationships, we performed the nearest neighbor analysis and found that the distances between the following pairs of markers were significantly reduced in 4-NQO-induced HNSCC in Batf2−/− mice: from CD206+ to CD206+ cells, from PD-L1+ to CD206+ cells, from CD4+ to CD206+ cells, and from Tbet+CD4+ to CD206+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 11g). These findings suggest that BATF2 promotes the expansion of effector population in the TME of HNSCC.

Discussion

Clinical evidence shows that the number of tumour-specific antigens in HNSCC does not correlate with their immunogenicity1. HNSCC are highly mutated yet only show a modest response rate to ICB. We previously found that STING is indispensable for the immunogenicity of HNSCC4. STING stimulation sensitized cancer to ICB in mouse models5,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Multiple clinical strategies, such as irradiation and DNA damage repair inhibition, converge on the STING pathway for effective immune priming. However, recent phase I trials showed that a substantial portion of patients with cancer were insensitive to STING agonists, even in combination with ICB20,32. The data suggest that additional mechanisms dictate cancer responses to STING stimulation. Although point mutations or genetic deletion of STING are uncommon in squamous cell carcinomas, it is heavily targeted through four types of mechanisms. First, HNSCC oncogenes, such as SOX2, and HPV16 E7, promote the rapid turnover of STING, suppressing the downstream signaling4,5. Second, the expression of STING is often lost through post-transcriptional or post-translational modifications26. Third, palmitoylation is a unique modification for STING that directs it to the ER membrane33. Cancers can suppress the palmitoylation of STING by inhibiting the protein S-acyltransferases, also known as the DHHC enzymes, which are a family of enzymes responsible for attaching a palmitate molecule to cysteine residues on proteins34. Last but not least, certain metabolic conditions can serve as a rheostat for the downstream TBK1 signaling. For example, we previously found that saturated fatty acids, but not unsaturated fatty acids, potently inhibit STING, driving more aggressive HNSCC growth in obese mice3. This study identified a glutamine-inhibited tumour suppressor, BATF2, which maintains the fitness of STING-IFN-I signaling. This is conceptually in agreement that glutaminolysis underpins M2-like polarization of macrophages17. Inhibition of glutamine metabolism can reduce MDSC and improve effector T-cell infiltration16,35. Human cancers frequently exhibit resistance to STING-inducing therapies, but the mechanism is not entirely clear. Using fresh human oral squamous cell carcinoma specimens, which showed a broad dynamic range of IFN-I production in response to STING agonists, we identified a positive correlation between BATF2 and tumour response to STING agonists. In addition, we found that BATF2 and IFN-I target genes were largely inversely correlated with glutamine metabolism genes, substantiating the physiological relevance of glutamine-mediated BATF2-IFN-I suppression.

Epigenetic control of macrophage alternative activation has been characterized in depth. The repressive mark H3K27me3 deposition on the promoters of immune suppressive Arg1 and Mrc1 can be reduced by IL4 through Jmjd3-dependent demethylation36. Glutamine potentiates M2-like polarization of macrophages by enabling Jmjd3-dependent reduction of H3K27me3 deposition on the promoters of Arg1, Ym1, Retnla and Mrc117. Conceptually in agreement, here we show that glutamine can simultaneously promote the deposition of H3K27me3 on the promoter of BATF2 and IFN-I target genes. Enhancer Of Zeste 2 Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Subunit (EZH2) is a key enzyme that methylates H3K27. Recent studies show that inhibition of EZH2 potentiates IFN-I37, which supports this mechanistic link. Thus, in addition to improving the pharmacokinetic properties of STING agonists, the development of strategies to overcome BATF2-dependence, such as inhibition of EZH2 or glutamine metabolism, is promising to sensitize cancers to STING-mediated immune priming approaches. Indeed, we found that although inhibition of glutamine metabolism did not further strengthen low-dose, non-formulated CDN’s effect on tumour control in mice on a regular diet, JHU083, a glutaminase inhibitor, sensitized tumours to STING stimulation in mice on an isocaloric glutamine-rich diet.

The classical tumour suppressor genes are defined as those whose loss at the genetic level or mutations enable early tumour onset. Here, we show that BATF2 potentially informs a class of genes with tumour-inhibitory function but are primarily regulated at epigenetic levels by the unique metabolic cues in the TME. Interestingly, glutamine is not the only metabolite that dampens BATF2 expression. Through a comprehensive screen using defined nutrient deficiency media, we tested five non-essential amino acids and ten essential amino acids and found that only five amino acids, including glutamine, tyrosine, valine, isoleucine and methionine, can repress BATF2. Conceptually in agreement with our findings of glutamine-rich diet’s suppression of the STING-IFN-I pathway, dietary methionine restriction enhances STING-IFN-I activation38. We developed robust, high-fidelity NOOC1 and NOOC2 syngeneic models, in combination with carcinogen-induced models, to substantiate the tumour-inhibitory function of BATF2 in HNSCC. However, the tumour suppressor role of BATF2 is not limited to HNSCC. BATF2 was shown to sensitize gastric cancer to 5-FU39. BATF2 can promote CD8+ T-cell infiltration in patients with NSCLC40. BATF2 is also a tumour suppressor in glioblastoma by inhibiting the recruitment of MDSC41. Here, we coined a molecular mechanism underpinning the tumour suppressor function of BATF2. BATF2 binds to the LBD of STING to facilitate STING oligomerization. The phosphorylation of BATF2 at S227 is critical for its immune-activating role. Tumours expressing wild-type BATF2 are spontaneously rejected, while tumours expressing the S227A BATF2 mutant failed to be recognized by the immune system. BATF2-mediated immune recognition of cancer is potentiated by stepwise infiltration of phospho-Tbk1+, phospho-Irf3+ CD11b+ cells and γδ T-cells at early timepoints, followed by significant expansion of effector αβ T-cells. BATF2 is most highly expressed by epithelial cells and myeloid cells. In addition to its cancer cell-specific role, host BATF2 expression potentiates effector T-cell expansion. To mitigate BATF2 suppression, we identified glutamine metabolism in the TME as a central metabolic cue that suppresses IFN-I response in a BATF2-dependent fashion. Diet enrichment of glutamine dampens cancer response to IFN-I agonists. In agreement, pharmacological inhibitors of glutamine metabolism significantly restored IFN-I response and sensitized refractory tumours to STING agonists, especially in hosts on a glutamine-rich diet. Overall, by taking integrated analyses of human samples, molecular pathways and pre-clinical models, we have identified BATF2 activation as a central glutamine-responsive, tumour-suppressive pathway shaping the plasticity of STING response and HNSCC immunogenicity.

Methods

Cell culture and treatments

The HNSCC cell lines FaDu, UMSCC22A, UMSCC22B, UMSCC108, PCI13 and UMSCC49 were maintained in DMEM (10-013-CV, Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Life Technologies) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (15-140-122, Gibco). THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (MT10040CV, Corning) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco, Life Technologies and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (15-140-122, Gibco). HEK-293T and RAW264.7 were cultured in the same medium as HNSCC cell lines. MOC2-E6/E7, NOOC1 and NOOC2 cell lines were cultured in the 60% IMDM (SH30228.01, HyClone) with 30% F12 nutrient mix (11764-054, Gibco), 5% FBS, 5 μg/mL insulin, 40 ng/mL hydrocortisone, 5 ng/mL EGF, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. 4MOSC1 cells were cultured as previously reported22. NOM9-TK cells were cultured in oral keratinocyte medium (Sciencell, Catalog No.#2611). The defined amino acid deficiency media were formulated as previously reported42. BMDM were isolated from both male and female littermate wild-type C57BL/6J and Batf2− mice femurs and differentiated as described earlier3. The experimental BMDM were plated in DMEM containing 20% heat-inactivated FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin for the indicated treatment. In the experiments evaluating the impact of glutamine on the IFN-I pathway, BMDM were seeded in a medium containing 90% glutamine-free RPMI 1640 (21870076, Gibco), 10% dialyzed FBS (SH30079.01, HyClone) and indicated levels of L-glutamine (25030081, Gibco). Cells were cultured in a 37 °C humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Treatments included 2′3′-cGAMP (tlrl-nacga23, Invivogen), ISD (tlrl-isdn, Invivogen), poly(I:C) (tlrl-pic, Invivogen), 5′ppp-dsRNA (tlrl-3prna, Invivogen), diABZI (tlrl-diabzi-2, Invivogen) and BPTES (SML0601, Sigma) as described in paper. NOOC1, NOOC2 and UMSCC cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling. FaDu, HEK-293T cells and THP-1 cells were from ATCC. Other cell lines were not authenticated. All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Animals

We obtained six to eight-week-old C57BL/6J (strain 000664) mice from the Jackson Laboratory. The Ifnar1−/− strain backcrossed to the C57BL6/J background for over nine generations was reported3. The Rag1−/− (strain 002216) and Sting−/− (Strain 017537) mice were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory. The sperms of Batf2−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Shizuo Akira. The cryorecovery was performed by Taconic. The mice were genotyped by the following primers: Batf2 shextra 5′-ACATCGGTCTCAGAGAGTTTGGAGTGG-3′, Batf2 WT 5′-TAGGCCCCTTCTCTAGAAGAAGGATGG-3′, Batf2 KO 5′-CTAAAGCGCATGCTCCAGACTGCCTTG-3′. Mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle with a room temperature of 72 °F and an air relative humidity of 57%. For the 4-NQO-induced HNSCC mouse model, wildtype and Batf2−/− mice were fed with drinking water containing 50 μg/mL 4-NQO for 16 weeks before regular water feeding for an additional six weeks. We started to monitor oral lesions ten weeks post-starting date. For the glutamine diet experiments, 6–12-week-old C57BL/6J mice were provided with a diet that contained 15 kcal% fat, 200 × g glutamine and 181 × g carbohydrates/3947 kcal (A16070103, Research Diets) or a control diet that contained 15 kcal% fat and 381 × g carbohydrates/3947 kcal (A11112201, Research Diets) on the same day when tumour cells were implanted. Anti-mouse CD8α (BE0061, Bio X Cell, Clone: 2.43), anti-mouse Cxcl10 (BE0040, Bio X Cell, Clone: 1F11), anti-Pd-1 (BP0033-2, Bio X Cell, Clone: J43) and anti-Ctla-4 antibody (BP0131, Bio X Cell, Clone:9H10) were administered by intraperitoneal injection. Free c-di-AMP (tlrl-nacda-5, Invivogen) was administered via intra-tumoural injections or in combination with JHU-083 (HY-122218, MCE) by PO at 1.82 mg/kg when the average tumour size reached 150 mm3. Mice were humanely euthanized when the tumour volume reached 2000 mm³ or the ulceration exceeded 50% of the tumour surface area.

Human specimen analysis

Human specimens were from the Oral Pathology and Head and Neck Surgery services. HNSCC specimen analysis was approved by IRB protocols HUM00113038 and HUM00042189 at the University of Michigan and 2024-0364 at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Informed consent was obtained for specimens utilized for bulk RNA-Seq. All specimens were de-identified, and the aggregated patient’s demographic information is summarized in Supplementary Data 1–3. The HNSCC tissues used in this experiment have been exhausted and are unavailable. In the TMA analysis shown in Fig. 1e, the investigators were blinded to the CD8+ T-cell counts within the TME.

Gene expression and knockout

We generated BATF2-expressing retroviruses and transduced human HNSCC cells (FaDu and UMSCC22A) and murine HNSCC cells MOC2-E6/7 with retroviruses to produce stable cell lines. We generated the BATF2-179A and BATF2-227A mutants, which contain serine-to-alanine mutations and cannot be phosphorylated at 179S and 227S by using a Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (E0554S, NEB). We generated BATF2-targeted CRISPR-Cas9 lentiviruses using a single-guide RNA (sgRNA): 5′-CACCGTGCACCTCTGTGGGGGCAAT-3′. We transduced UMSCC108 and UMSCC49 with the BATF2-targeted CRISPR/Cas9 lentiviruses and generated stable cell lines. We generated Batf2-targeted and Sting-targeted lentiviruses using shRNA (shBatf2: 5′-GCACGAATCCTTGGAGAAACA-3′ and shSting: 5′-CAACATTCGATTCCGAGATAT-3′) and transduced them with MOC2-E6/7 or NOOC2 cells. We transduced the same cell line with empty vector lentiviruses to generate the control cells. STING domain truncation mutants were generated by PCR amplification using sequence-specific primers. The PCR product and the pcDNA3.1-Flag backbone were digested with NotI and EcoRI restriction endonucleases, gel-purified and subsequently ligated with T4 DNA ligase. The ligation mixture was transformed into Stbl3 competent cells, and colonies were selected on LB agar containing ampicillin (100 µg/mL). After plasmid extraction, the constructs were validated by Sanger sequencing and further confirmed by Western blot analysis to ensure optimal expression.

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation

Cells were washed with 1× PBS twice and then lysed in 1× RIPA buffer (9806, Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (11836170001, Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (78420, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The protein concentration was measured by a BCA kit (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and boiled with 4× sample buffer (NP0007, Invitrogen) for 5 min at 95 °C. Prepared lysates were loaded on NuPAGE 4 to 12% (NP0323BOX, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 16% (XP00162BOX, Thermo Fisher Scientific) Bis-Tris Gel. Followed by blocking in 10% milk, membrane was incubated in 5% milk with the primary antibodies: BATF2 Antibody (ab204510, Abcam, dilution 1:400), Phospho-TBK1(Ser172) Antibody (5483S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), TBK1 Antibody (3504S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), Phospho-STING (Ser365) Antibody (72971S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), STING Antibody (13647S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), phospho-IRF-3 (Ser396) Antibody (4947S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), IRF-3 Antibody (4302S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) Antibody (9167S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), STAT1 Antibody (14994S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), VDAC Antibody (4661S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), Lamin B1 Antibody (ab16048, Abcam, dilution 1:1000), α-Tubulin Antibody (3873S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000) and anti-β-actin antibody (ab49900, Abcam, dilution 1:1000). The secondary antibodies anti-rabbit IgG-HRP antibody (ab97051, Abcam, dilution 1:20000) and anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody (ab97023, Abcam, dilution 1:20000) were incubated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To determine phosphorylated proteins, samples in 1× Sample Buffer (191-13272, Fujifilm) were loaded into SuperSep™ Phos-tag™ gel (199-18011, Fujifilm) and were blotted for BATF2 and IRF3.

To immunoblot native proteins, the cells were lysed in 1× NativePAGE™ Sample Buffer and 1% Digitonin (BN2008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and sonicated 15 s for 3 times. The BCA protein assays were performed to quantify lysate protein concentrations. The samples were loaded into NativePAGE 4–16%, Bis-Tris, 1.0 mm, Mini Protein Gels (BN1002BOX, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and were run in the NativePAGE Running Buffer (BN2007, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, the proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane in the NuPAGE Transfer Buffer and blotted by a STING Antibody (13647S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000).

HEK-293T and FaDu cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes and were transfected with 1 µg/mL FLAG-STING and 1 µg/mL BATF2-HA plasmids for 24 h to assess the interaction between BATF2 and STING. Experimental cells were lysed on ice by NP40 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% NP-40) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Anti-FLAG M2 Affinity gel (A2220, Millipore Sigma) and anti-HA Agarose (26181, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to pull down FLAG-STING and BATF2-HA proteins. The immunoprecipitated proteins were blotted for anti-FLAG M2 Antibody (14793, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000) and anti-HA-Tag Antibody (3724, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000).

Immunofluorescent confocal microscopy

Cells grown in 4-well chamber culture slides were stained with 100 nM MitoTracker (M7510, Invitrogen) Orange for 15 min at 37 °C, followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton ×-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies anti-HA-488 (2350S Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:800) and anti-STING (13647S, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:50) for 1 h. After washing, cells were incubated with AF647 labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h followed by staining with Hoechst 33342 (H3570, Life Technologies, dilution 1:5000). Coverslips were mounted in ProLong antifade mountants and imaged with a Nikon A1SI inverted confocal microscope.

Subcellular fractionation

The purification protocol of the nuclei, cytosol and ER membranes by serial centrifugation was adapted from a reported protocol43. Briefly, THP-1 STING WT cells were lysed by ~70 iterations of up and down passes of the pestle in a hypotonic buffer. Nuclei were obtained by centrifugation of the lysed cells at 600 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The nuclear pellet (P600) was resuspended and incubated in the nuclei lysis buffer for 30 min on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected as the nuclear fraction. Post-nuclear supernatant (S600) was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove mitochondrial fraction (P5000) and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove lysosomal and plasma membrane fraction (P20000). The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to obtain the ER fraction (P100000) and the cytosolic fraction (S100000).

Quantification of gene expression levels

Total RNA was extracted by RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (74136, Qiagen). The RNA concentration was determined using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Subsequently, the RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit along with RNase inhibitor (4368814 and N8080119, respectively, Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences have been previously reported3,4. Additional primers are as follows: human BATF2 forward 5′-3′ CAGCTGAAGAAGCAGAAGAACCG, reverse 5′-3′ TTTTCCAGAGACTCGTGCTGC; mouse Batf2 forward 5′-3′, CACCGCGATCGCATGCAACTCTGTGGGAGTAG, reverse 5′-3′ CTAGAAGTGGACTTTTGCAGAAG; Mouse Oas1 forward 5′-3′, GCCTGGTCACGCACTGGTA, reverse 5′-3′ AAGCCCTGGGCTGTGTTG; mouse Mx1 forward 5′-3′, GGGGAGGAAATAGAGAAAATGAT, reverse 5′-3′ GTTTACAAAGGGCTTGCTTGCT; human CXCL9 forward 5′-3′, GTGGTGTTCTTTTCCTCTTGGG, reverse 5′-3′ ACAGCGACCCTTTCTCACTAC; human CXCL10 forward 5′-3′, CTCCAGTCTCAGCACCATGA, reverse 5′-3′ GCTCCCCTCTGGTTTTAAGG; mouse Ifng forward 5′-3′ TCAAGTGGCATAGATGTGGAAGAA, reverse 5′-3′ TGGCTCTGCAGGATTTTCATG; human ISG54 forward 5′-3′, ACGGTATGCTTGGAACGATTG, reverse 5′-3′ AACCCAGAGTGTGGCTGATG.

ELISA and Luminex

Cells were seeded into six-well or 96-well plates and treated with agonists as indicated. The amount of Ifn-β and Tnf-α in the supernatant was measured by a mouse Ifn-β kit (luex-mifnbv2, Invivogen) and a Tnf-α ELISA kit (BMS6073, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A mouse Luminex Discovery Assay kit (LXSAMSM, R&D Systems) was also used to quantify cytokines.

Tissue histology, immunohistochemistry and multispectral imaging

Tongue specimens from mice in the 4-NQO model were fixed in 10% formalin and then serially sectioned before paraffin embedding. The slides were deparaffinized and stained in Mayers Hematoxylin. After washing four times with tap water, the slides were washed with 1× PBS and distilled water. Then, they were stained with Alcoholic-Eosin and dehydrated through ethanol followed by xylene wash.

Human HNSCC specimens were included in tissue microarrays (TMAs). TMAs were stained with anti-BATF2 antibody at 1:200 dilution (ab204510, Abcam). Paired longitudinal specimens from patients who progressed from OPMD to oral cancer were stained for BATF2 using the same protocol. Anti-CD20 antibody (ab64088, Abcam, dilution 1:200) and anti-Tcr γ/δ antibody (#14-5711-82, ThermoFisher Scientific, dilution 1:100) were used for syngeneic murine tumour specimens. The specimens were incubated with a secondary antibody (PK-4001, Vectastain, dilution 1:100). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining intensity was quantitated in tumour tissue by selecting a region of interest using Aperio ImageScope or ImageJ, followed by quantification.