Abstract

Nanofiltration (NF) is a key membrane separation technology that is promising in various chemical and environmental applications. The need for high-performance thin-film composite (TFC) NF membranes, particularly those with enhanced salt selectivity and fouling resistance, necessitates effective strategies for optimizing their fabrication processes—interfacial polymerization (IP). In this study, we demonstrate an effective strategy for fine-tuning of IP process through integrating lyotropic liquid crystals (LLCs), which self-assemble into an interlayer with hexagonal structure on substrates. Performing IP on the LLC-coated substrates leads to the formation of polyamide with characteristic tubular structure. Compared with conventional TFC membranes, the LLC-modulated TFC membranes display doubled water permeability while preserving comparable Na2SO4 selectivity, thereby achieving an enhanced water/salt selectivity. Moreover, these membranes demonstrate high ion/ion selectivity (e.g., Na+/Ca2+ and Li+/Mg2+) and enhanced fouling resistance, rendering them highly desirable for various separation processes. Further exploration into interfacial structures and mechanisms reveals the pivotal role of the LLC-interlayers in affecting the diffusion of the diamine monomer (i.e., piperazine), thereby resulting in the polyamide layer with the distinctive tubular structure and improved separation properties. Our results highlight the promise and potential of utilizing interlayers with self-assembled structures for creating high-performance NF membranes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanofiltration (NF) represents a cutting-edge technology in membrane separation1,2. This process utilizes membrane materials featuring pore sizes of ~1 nm, enabling effective separation of solutes on a sub-nanometer scale3. As such, NF membranes exhibit unparalleled selectivity towards both ionic and organic species. Such characteristic renders them practical solutions for various applications, such as water softening, lithium extraction, and solvent separation4,5,6,7.

The forefront of NF membrane technology relies on the development of thin-film composite (TFC) membranes8. These membranes consist of a polyamide active layer created via interfacial polymerization (IP) on top of a porous substrate9,10,11,12. Despite the advance of NF process, developing NF membranes with enhanced selectivity remains challenging due to the selective-permeability trade-off3,13. That is, an increase in water permeability is associated with a corresponding rise in salt permeability, thereby leading to a reduction in membrane selectivity. In addition, the accumulation of the rejected substances, such as organic, inorganic, or biologic compounds, on membrane surfaces poses another daunting challenge of fouling14,15,16,17. Such unprecedented fouling significantly increases operating costs and reduces the life span of the NF membranes.

Recent studies have highlighted significant enhancement of NF membrane performance through integrating nanomaterial interlayers13,18. These advancements involve the deposition of various nanomaterials, such as nanotubes19,20, nanostrand21, graphene22, or metal-organic frameworks23, onto substrates, followed by IP process to form polyamide layers (Fig. 1a)11,24,25,26,27. The introduction of these interlayers altered physiochemical properties of the substrates, including surface tension, porosity, and morphology. Consequently, the modified substrates further affect IP process to form polyamide layers with high separation performance or fouling resistance28,29,30. However, although these interlayers have been shown to modulate the IP process, the relationship between the fundamental properties of the interlayer structure and the resulting polyamide morphology remains unclear. Moreover, the mechanistic basis by which interlayer design influences polyamide performance has yet to be systematically elucidated11. Such discrepancy and knowledge gaps are largely ascribed to the fact that the existing strategies for constructing interlayers relied on uncontrolled, free deposition processes. As a consequence, the resulting interlayers often exhibit disordered, non-tunable features, thereby obscuring the delineation of exact mechanisms of the interlayers in influencing IP processes.

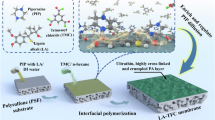

a Previous approaches in using various nanomaterials as interlayers. These nanomaterials were directly deposited on a substrate, thus exhibiting disordered, non-tunable structures on the surface. b Strategies on using self-assembled lyotropic liquid crystal (LLC) interlayers. Polymerizable surfactant molecules (i.e., MA11-6-11MA) self-assemble into hexagonal columnar LLC layer, thereby displaying a highly ordered, tunable structure on the surface.

Lyotropic liquid crystals (LLCs) are a class of amphiphilic molecules that can self-assemble in water to form ordered structures, such as columnar, cubic, and lamellar phases. These ordered structures could be maintained through polymerization of LLC monomers in aqueous phase into solid state. Such distinctive feature enable the design of LLC architectures for various applications, including drug delivery31,32, energy storage33,34, and biological imaging35,36. Furthermore, recent efforts have explored LLC materials as building blocks for fabricating separation membranes, especially for NF applications37,38. For example, LLCs were utilized to synthesize NF membranes with bicontinuous cubic structures, leading to the formation of interpenetrating networks. These networks exhibited an effective pore size of 0.75 nm, which was capable of high salt rejection while displaying comparable water permeability to that of commercial membranes36. In another study, researchers leveraged LLCs with direct cylindrical mesophase (HI) to fabricate NF membranes featuring hexagonally packed cylinders. Such structure enabled water permeance through the gap between cylindrical nanofibers but excluding larger-size solutes via size exclusion37. While these studies highlight the potential of LLCs as a selective layer for the direct fabrication of NF membranes, substantial efforts are needed to systematically evaluate their performance in real-world applications, including fouling propensity, chlorine resistance, and long-term stability39. Given the established scalability and widespread application of the interfacial polymerization (IP) process—the gold standard in NF membrane manufacturing13—incorporating LLCs as an interlayer offers a facile and practical strategy for tailoring polyamide properties. This approach will enable the effective modulation of polyamide NF membranes with well-defined structures and enhanced performance, more importantly, aligning with industrial requirements for large-scale implementation.

In this study, we demonstrate an effective strategy in regulating IP process by incorporating interlayer made of LLCs. The LLC molecules self-assemble into hexagonal columnar phases, thus generating interlayers with highly-ordered structure on substrate surface (Fig. 1b). In the following IP process, the presence of the LLC interlayer facilitates the formation polyamide layer with tubular structure and internal nanocavities. Evaluating performance of the resulting TFC membranes reveals an enhanced water/salt and ion/ion selectivity, as well as enhanced anti-fouling properties. We also carry out systematic characterization of interfacial structures and elucidate mechanisms and effects of the LLC interlayer in regulating IP process. Our results underscore the potential in using self-assembled interlayers in IP reaction for fabricating high-performance NF membranes.

Results

Loading of lyotropic liquid crystal (LLC) interlayers on substrate surface

We synthesized a polymerizable amphiphilic surfactant, MA11-6-11MA, whose chemical structure is illustrated in Fig. 1b40. This molecule consist of a hydrophilic head with two quaternary ammonium groups and two hydrophobic tails, each containing 11 carbon atoms (synthesized procedure illustrated in the Supplementary Figs. 1). The MA11-6-11MA/water binary phase diagram illustrates the transitions through micellar solution (LI) to hexagonal columnar (HI), lamellar (Lα), and crystal (K) phases, as the surfactant concentration increased from 0 to 100 wt% at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 4). When mixed with water at a weight ratio of 3:1, this molecule undergoes self-assembly into a hexagonal columnar phase liquid crystal, referred as HI-LLC. Observation under polarized optical microscopy (POM) revealed a distinct fan-like texture (Fig. 2a), which is the characteristic of the HI mesophase structure.

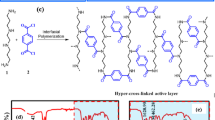

POM images of LLC columnar mesophase (a), pristine polysulfone (PSf) substrate (b), and PSf surface after coating LLC Col mesophase (c), where a birefringence fan-like texture was observed. SEM images of the surface of pristine PSf (d) and PSf-LLC composite (e). f ATR-FTIR spectra of PSf support (red) and LLC (yellow), and PSf-LLC composite (blue). XPS C1s and O1s spectra of pristine PSf (g) and PSf with LLC (h). i Schematic illustration of SAXS measurements. The LLC-coated film was placed perpendicularly to the propagation of X-rays (upper panel). Miller indices (hk0) of 2-D hexagonal lattice (reciprocal space), the rings indicate the reciprocal points with the same q spacing (middle panel). Table of the {10}, {11}, and {20} families of lattice planes and their q values (lower panel). j 1-D integrated SAXS data displays the structure of LLC hexagonal structure (yellow) and PSf surface after LLC coating (blue).

We then coated the HI-LLC mixture onto a microporous polysulfone (PSf) support, which was subsequently used as a substrate for interfacial polymerization (IP) reaction. During surface coating, we added ethanol into the LLC mixture to enhance even spreading of the viscous LLCs on the surface. By dispersing LLC in ethanol at different concentrations and loading it onto the substrate, we obtained LLC layers with varying thicknesses (Supplementary Fig. 5). Specifically, the thickness of the LLC layer at concentrations 2% and 20% was 180 and 500 nm, respectively. The LLC-impregnated substrate was then shaken for 2 min to facilitate solvent evaporation. Then, a focused spot UV beam was shed on the coated-surface to initiate the crosslinking of the LLC monomers to form a solid LLC-film on the PSf substrate. Notably, the POM texture remained unchanged before and after UV-induced crosslinking, indicating the phase stability of this HI-LLC (Supplementary Fig. 6). Following the coating process, the LLC-coated PSf substrate also exhibited the fan-like texture under POM (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 7), while the transmission intensity of the pristine PSf was undetectable (Fig. 2b). Moreover, numerous pores were observed on the pristine PSf surface (Fig. 2d), consistent with the pore size of 42.8 nm determined from molecular-weight cut-off (MWCO) measurements (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, these pores were not observable on the surface of the LLC-coated sample (Fig. 2e), indicating uniform coverage of the LLC layer on the substrate. Notably, the presence of the LLC interlayer resulted in an interface with smaller-sized, uniform pores, as evident from MWCO result (Supplementary Fig. 9).

FTIR spectra displayed a new peak at 1721 cm−1 for the LLC-coated sample (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 10), attributed to the stretching of the ester group (O-C = O). XPS spectra of both pristine (Fig. 2g) and LLC-coated PSf substrates (Fig. 2h) exhibited strong C1s signals at 284.6 eV. Deconvolution of this peak revealed sub-peaks corresponding to C–O (286.4 eV), C–C (284.6 eV), and C–S (285.1 eV), respectively41,42. The LLC-coated sample shows a decreased intensity of the C–S peak, a characteristic fingerprint of PSf material, along with an emergence of a peak at 288.3 eV (characteristic O–C=O of LLC). Taken together, these results verify the successful coating of the LLC-layer on top of the PSf substrate.

We further employed small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) to investigate the assembled structure of the crosslinked LLC on the surface (Fig. 2i). X-rays were propagated perpendicularly through the film plane, as illustrated in the schematic (the upper panel). Collected crystal plane families are indexed using Miller indices {hk}. The resulting LLC hexagonal structure was evident from the SAXS pattern, displaying scattering rings from {10}, {11}, and {20} lattice planes (the middle panel)43. The corresponding lattice families are also tabulated in the lower panel. Integration of the scattering intensity over the scattering vector revealed a scattering wave vector (q) relative to the Bragg reflection (Q) at ratios q/Q* = 1:√3:√4 (Fig. 2j), corroborating with the hexagonal structure of the LLCs. The d-spacing of the hexagonal structure was determined using Bragg’s law:

where θ is scatting angle, \(\lambda\) is X-ray wavelength, n is the diffraction order, d is Bragg spacing. Based on this equation, the calculated d-spacing was 3.4 nm. Considering the weight ratio of 3:1 (surfactant: water) used in our LLC system, the estimated diameter of the free volume was ~1 nm. Notably, the PSf substrate was essentially free of scattering signal (red curve in Fig. 2j), and the {10} plane scattering peak was retained after loading the LLC layer (blue curve in Fig. 2j), demonstrating the effective introduction of the LLC layer onto the PSf substrate. To further investigate the presence of the LLC interlayer throughout the IP process, we analyzed 2D SAXS patterns at various polymerization stages (Supplementary Fig. 11). The results showed that when the LLC interlayer was immersed in the PIP aqueous solution, both the {11} and {10} scattering rings remained intact. Upon subsequent exposure to the TMC hexane solution, the {11} scattering ring disappeared, while the {10} scattering ring remained observable. However, during the final step of the IP process—where the membranes were rinsed with hot water—the {10} scattering ring also disappeared. These findings confirm that the LLC structures were effectively removed upon completion of the IP reaction.

Fabrication of tubular polyamide NF membranes

Polyamide active layer is produced by IP reaction between piperazine (in aqueous phase) and trimesoyl chloride (in hexane phase) on a support. We aimed to tune IP reaction by introducing the interlayer of the self-assembled HI-LLC, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 3a. Subsequently, IP was carried out on top of the LLC-coated support to yield a polyamide selective layer. The cross-section structure of the resulting thin-film composite membrane was visualized by SEM images (Fig. 3b), in which elemental mapping displays a clear interface between the nitrogen-rich polyamide and sulfur-rich PSf (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13).

a Schematic diagram of interfacial polymerization on top of an LLC layer. An LLC layer is uniformly deposited on the PSf surface, followed by interfacial polymerization of piperazine (aqueous phase) and trimesoyl chloride (hexane phase) to form a polyamide active layer on top. b SEM cross-sectional image of asymmetric polyamide active layer formed on PSf support. c Elemental mapping image of N element and S element. d SEM surface image of polyamide. e SEM cross-sectional image of the cavity structure inside the polyamide. f TEM cross-sectional image of the crumpled polyamide formed on PSf support. g AFM image and schematic representation of the crumpled polyamide formed on PSf support. h AFM image and schematic representation of the smooth PSf substrate.

Notably, a characteristic tubular structure with a width of ~1 μm and a length of ~10 μm was observed on the polyamide layer (Fig. 3d). A closer examination of this tubular structure revealed a hollow internal cavity (Fig. 3e). The presence of tubular protuberances in polyamide was also observed by the cross-sectional image obtained through transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Fig. 3f). This tubular structure is evenly distributed across the surface, contributing to a rough morphology (Fig. 3g) on top of the smooth PSf substrate (Fig. 3h). While a similar internal cavity has been widely observed in the characteristic ridge-and-valley structure of TFC membranes made from the IP reaction between m-phenylenediamine (MPD) and trimesoyl chloride (TMC)44,45, the size of the tubular structure (~1 μm) in our membranes is significantly larger than that of for the typical ridges (~100 nm). We surmised the emergence of this tubular structure is largely ascribed to the introduction of the LLC interlayer, whose exact role in manipulating IP thus necessitates further investigation and elucidation.

Effects of LLC interlayer on polyamide structure

To investigate the role of the LLC interlayer in affecting IP reaction, we first assessed and compared the impacts of LLC concentrations. The LLC mixture was dissolved in ethanol at different concentrations and deposited on PSf substrate. We then performed IP on these substrates to produce polyamide thin-film nanocomposite (TFN) membranes, which were respectively denoted as TFN0%LLC, TFN2%LLC, and TFN20%LLC. The control sample (i.e., TFN0%LLC) displayed a smooth surface (Fig. 4a), consistent with the typical surface structure of NF membranes made from the PIP-TMC reaction24,46,47,48. Deposition of low concentration LLC (2 wt%) leads to the emergence of crescent-shaped protrusions on the surface (Fig. 4b). This structural feature evolved into a distinctive Y-shape tubular shape using a 20 wt% LLC interlayer (Fig. 4c). Further increasing LLC concentration to 50 wt% and 100 wt% maintain the presence of the protrusion features across the entire LLC concentration range (Supplementary Fig. 14). In general, an increase in LLC concentration resulted in protrusions with smaller lateral sizes but higher surface densities. As a consequence, these protrusions lead to increased polyamide thickness (Fig. 4d–f, from 250 nm of TFN0%LLC to 382 nm of TFN20%LLC) and increased surface roughness (Supplementary Fig. 15). Notably, the protrusion structure remained unchanged after operating at 5 bar—a typical pressure used in NF system (Supplementary Fig. 16), demonstrating their structural stability.

SEM and AFM surface images of polyamide structure formed after adding different concentrations of LLC (a TFN0%LLC, b TFN2%LLC, c TFN20%LLC). SEM cross-sectional images of polyamide structure formed after adding different concentrations of LLC supported on PSf membrane (d TFN0%LLC, e TFN2%LLC, f TFN20%LLC). XPS C1s and O1s spectra of TFN membranes (g TFN0%LLC, h TFN2%LLC, i TFN20%LLC).

Analysis of C1s and O1s spectra revealed a notable decrease in the content of carboxylic acid groups (O–C=O) with the introduction of LLC interlayers (Fig. 4g–i). XPS analysis of the elemental composition of the polyamide layer indicated the degrees of crosslinking (DOC) of 40.4% and 70.0% for TFN0%LLC and TFN20%LLC (Fig. 4g–i, Supplementary Figs. 17, and Supplementary Table 1), respectively. Deconvolution of the high-resolution C1s and O1s spectra of the pristine TFN0%LLC (Fig. 4g) revealed a distinct peak at 533.51 eV corresponding to the carboxylic acid (–COOH) group. In contrast, this peak was not observable in the TFN20%LLC membrane, implying the disappearance of –COOH group. This result aligns with the increased degree of crosslinking for this membrane, indicating the presence of a more uniform network for the resulting polyamide layer. To further quantify the carboxyl group content, we employed a silver ion probe method49,50. Specifically, an adsorption–desorption procedure was conducted using Ag⁺ ions, and the desorbed silver concentration was quantified via inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). TFN0%LLC exhibited a carboxyl group density of 16.6 sites nm−2, while TFN20%LLC showed a reduced density of 12.8 sites nm−2. This result provides further evidence that the LLC interlayer reduces the formation of unreacted or hydrolyzed carboxyl groups (Supplementary Fig. 19). We also tested the DOC of polyamide formed after grafting a higher concentration of LLC, but the value slightly decreased relative to the TFN20%LLC membrane (Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 1). As the LLC concentration further increases, the viscosity of the dispersion also rises due to the reduced ethanol content, reaching a gel-like state at 100% LLC concentration. This high viscosity leads to poor flowability and hinders uniform spreading, resulting in visibly uneven coating and defect formation upon deposition (Supplementary Fig. 21). Consequently, when LLC was loaded onto the substrate at high concentrations, the formation of defects became more likely. Additionally, AFM thickness measurements indicate that when the LLC concentration exceeds 50%, the thickness can increase to the micrometer scale, which further hinders the efficient reaction between PIP and TMC monomers during interfacial polymerization.

Enhanced separation performance and fouling resistance of LLC-modulated polyamide membranes

We further evaluated membranes performance using a lab-scale crossflow NF system. The presence of LLC interlayer significantly enhances the water permeance (Fig. 5a), with the 20% LLC membrane achieving 22.2 ± 0.3 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, nearly doubled that of the pristine TFN0%LLC (12.3 ± 0.2 L m−2 h−1 bar−1). This improvement is primarily attributed to the enlarged surface area resulting from the formation of Y-shape structure on the polyamide surface. Notably, the Na2SO4 rejection remained statistically comparable between the TFN0%LLC control (99.1 ± 0.1%) and the TFN20%LLC membrane (98.2 ± 0.2%) at the 95% confidence level (p = 0.08, n = 3; see Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 2), indicating that ion selectivity was largely preserved. Together, these results demonstrate enhanced water/salt selectivity enabled by LLC-modulated interfacial polymerization.

a Water permeance and Na2SO4 rejection of TFN0%LLC, TFN2%LLC, and TFN20%LLC membranes. b Normalized water flux during fouling-rinsing cycles tests of TFN membranes with a feed solution containing 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, and 50 mg/L sodium alginate. c, d Rejection of different cations and their selectivity (Na+/Ca2+, Li+/Mg2+) for different TFN membranes. e Comparison of the separation performance of TFN20%LLC membrane (red pentagram) with other reported membranes. The black dashed line represents the observed trade-off between water permeability and Na2SO4 rejection. The error bars represent the standard deviation of data from three replicate measurements.

The antifouling properties of the membranes were evaluated through three cycles of fouling-rinsing experiments using 50 mg L−1 sodium alginate (with 0.5 mM CaCl2) as model foulants (Fig. 5b). During the first cycle, the pristine TFN0%LLC membranes exhibited the most severe fouling, resulting in a 32% reduction in water flux. In comparison, the flux of TFN2%LLC and TFN20%LLC decreased by 25% and 23%, respectively. In the second and third cycles, water flux of TFN0%LLC also experienced a higher pronounced drop compared to that of TFN2%LLC and TFN20%LLC. Notably, the flux recovery of the TFN20%LLC membrane was over 90% after rinsing, suggesting that physical rinsing effectively removed majority of foulants. Over the 12-h fouling run, the control TFN0%LLC membrane exhibited the most severe fouling, with water flux reduction of >60%, whereas TFN2%LLC and TFN20%LLC were much less affected (Supplementary Fig. 22). SEM images of the fouled membrane surfaces revealed that the fouling coverage of TFN2%LLC and TFN20%LLC was significantly less compared to the TFN0%LLC membrane (Supplementary Fig. 23). This enhanced fouling resistance is likely attributed to two factors. First, the incorporation of the LLC interlayer resulted in TFN membranes with a lower density of –COOH groups. This reduction minimized Ca2⁺-mediated bridging effect, thereby mitigating fouling caused by alginate molecules. Second, the presence of the large tubular protrusions likely induced turbulence near the membrane surface. Such interfacial turbulence disrupted foulant deposition and reduced accumulation, thus enhancing the antifouling performance of the membranes.

Selective separation of monovalent and divalent ions from a mixture represents another major application of NF membranes, aiming at mitigating inorganic metal scaling51 or extracting lithium from salt lakes/brines52. The higher DOC and fewer carboxyl groups on the surface of TFN20%LLC membrane imply a more integral network within the polyamide layer, thereby enhancing selectivity toward ionic species. At the same time, the reduced negative surface potential, as confirmed by zeta potential measurements (Supplementary Fig. 24), weakens the electrostatic attraction to positively charged ions, further contributing to the improved ion separation performance. Notably, we further evaluate the rejection of the TFN20%LLC membrane also exhibited a higher rejection toward divalent cation (Ca2+ or Mg2+) compared to monovalent cation (Na+ or Li+), leading to a five-fold increase for the Na+/Ca2+ pair (Fig. 5c) and ten-fold increase for the Li+/Mg2+ pair (Fig. 5d). In particular, the TFN0%LLC membrane displays low rejection of both monovalent cations (37% for Na+ and 17% for Li+) and divalent cations (34% for Ca2+, and 16% for Mg2+). The TFN2%LLC membrane resulted in rejection of 19% for Na+, 51% for Li+, and 42% for Ca2+, 82% for Mg2+, while the TFN20%LLC exhibited high rejection of both divalent cations (87% for Ca2+ and 95% for Mg2+) and monovalent cations (28% for Na+, 48% for Li+). Using Eq. 3, we calculated the selectivity for monovalent (Na+, Li+) and divalent ions (Ca2+, Mg2+) for different membranes, i.e., the selectivity of pristine TFN0%LLC for Na+/Ca2+, Li+/Mg2+ is 0.96, 0.98, and the selectivity of TFN20%LLC for Na+/Ca2+, Li+/Mg2+ is 5.8 and 11.4. These results reveal the promise of the TFNLLC membranes in separating monovalent and divalent ions, which hold potential in various applications (e.g., water softening and lithium recovery). Despite the inherent trade-off in NF membranes, the TFN20%LLC membrane exhibits an enhanced performance in the permeability–selectivity trade-off plot (Fig. 5e), outperforming many NF membranes reported in previous studies.

Proposed impacts of LLC interlayer on interfacial polymerization

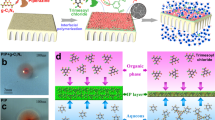

We further characterize the LLC-coated substrate for elucidating its regulated IP reaction mechanism. The LLC interlayer is deposited on the PSf substrate, leading to the formation of uniform channels for PIP molecule transport (Fig. 6b). In bulk solution, our LLC molecules self-assembled into a hexagonal columnar structure, evidenced by distinct {10}, {11}, and {20} scattering rings in SAXS patterns (Fig. 6c). Upon loading onto the substrate, only {10} scattering ring remains (Fig. 6d), ascribing to the thin-layer of the LLC layer coated onto the PSf surface. The 1D SAXS data, extracted from the 2D patterns in Fig. 6e, show an unchanged location of peak {10}, indicating that the hexagonal packing structure is maintained. In addition, the two-dimensional signals are shown as scatting rings instead of scatting points, indicating planar deposition of this hexagonal columnar LLC on the PSf substrate, and exposing positively charged hydrophilic groups to the surface. As a result, we observed an increase of surface hydrophilicity on the surfaces via water contact angle measurements (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 25 and 78° for pristine PSf vs. 40° for PSf20%LLC). To further investigate the state of hexane diffusion to the substrate surface during the IP process, we measured the underwater contact angle of hexane on the PSf and PSf20%LLC surface (Fig. 6f). The results showed a contact angle of 63°and 122° for PSf and PSf20%LLC, respectively, indicating greater oleophobicity toward hexane after the introduction of the LLC interlayer. These results indicated that the presence of the LLC layer enhanced the surface’s repulsion toward the organic phase, thereby increasing resistance to hexane wetting (Fig. 6a). During IP reaction, PIP molecules first penetrate the porous PSf and subsequently migrate into the homoporous LLC layer. Owing to the increased hydrophilicity of the LLC-modified surface, these molecules tend to spread and flatten, exhibiting enhanced wetting behavior. Importantly, the LLC interlayer restricts the vertical diffusion of PIP toward the organic phase interface due to both physical and chemical effects.

a Schematic diagram illustrating the effect of LLC surface on the wetting behaviors of the aqueous piperazine (PIP) solution and the hexane phase containing the trimesoyl chloride (TMC) monomer during interfacial polymerization. Compared to the pristine PSf substrate, the PSf-LLC substrate exhibits a lower water contact angle (ɵ1) and a higher hexane contact angle (ɵ2). b Schematic diagram illustrating transport PIP molecules during interfacial polymerization. Upon contact with TMC solution (in hexane), PIP molecules transport through the uniform channel with ~1 nm and adsorb on the surface. c 2D SAXS pattern of hexagonal columnar LLC. d 2D SAXS pattern of hexagonal columnar LLC coated on PSf substrate. The isotropic rings in the SAXS patterns indicated a parallel arrangement of the LLC on the PSf substrate. e 1D integrated SAXS data of LLC and PSf with LLC loading from the 2D patterns in (c, d). f Water contact angle (in air) and hexane contact angle (in water) of the substrate membranes. With increasing LLC concentration, water contact angle decreases, while the hexane contact angle gradually increases. The error bars represent the standard deviation of data from three replicate measurements. g Molecular dynamics simulation box depicting the diffusion of PIP molecules in pure water. h Simulation box of PIP diffusion in water containing the LLC molecule. i Mean square displacement (MSD) curves of PIP molecules in both systems. The diffusion coefficients were calculated from the slope of the linear region of the MSD curves using Einstein’s relation.

To further investigate the influence of the LLC interlayer on the substrate surface properties, we measured the zeta potential of pristine PSf and LLC-loaded PSf substrates. Pristine PSf exhibited a negative surface potential at pH > 3.5. In contrast, the zeta potential increased significantly with LLC loading, reaching 6.2 and 9.5 for 2 wt% and 20 wt% LLC, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 26). These results indicate that the LLC layer renders the substrate surface nearly electrically neutral at higher pH values. Given the positively charged nature of PIP molecules, this near-neutral surface weakens electrostatic attraction, further slowing PIP diffusion toward the reaction interface. Taken together, the nanoscale confinement and reduced electrostatic driving force constitute a dual hindrance mechanism, which lowers PIP flux at the interface and promotes the formation of protruded, wrinkle-like features in the resulting PA layer.

We also performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to determine diffusion coefficients of PIP molecules in pure water and in water containing LLC53,54. As shown in Fig. 6g, h, simulation boxes were constructed for both systems, and the mean square displacement (MSD) of PIP molecules was analyzed using Einstein’s relation. The diffusion coefficient of PIP was found to decrease from 2.50 × 10−9 m2 s-1 in pure water to 1.81 × 10−9 m2 s−1 in the LLC-containing environment. These results confirm that the presence of LLC significantly hinders the diffusion of PIP molecules, which play a critical role in regulating the polymerization kinetics and resulting membrane morphology.

In summary, we constructed the self-assembled LLC interlayer on PSf substrates. The presence of the LLC interlayer affected the IP reaction and thus yield a polyamide film with a characteristic Y-shaped tubular structure. Such LLC-modulated polyamide membrane not only exhibited enhanced ion-ion selectivity but also demonstrated exceptional resistance to fouling. The presence of the LLC layer significantly hinders the vertical diffusion of the aqueous-phase monomer (PIP) through physical confinement and reduced electrostatic interactions. Simultaneously, the increased interfacial hydrophilicity promotes lateral (in-plane) diffusion of PIP across the reaction interface. This anisotropic diffusion behavior leads to localized monomer enrichment, which in turn facilitates the formation of distinctive Y-shaped tubular nanostructures within the polyamide layer. Our study not only presents a platform for revealing the role of interlayer structure on manipulating the structure and performance of polyamide layer, but also offers a potential strategy using self-assemble interlayers with controlled surface properties for fabricating high-performance NF membranes.

Methods

Synthesis of lyotropic liquid crystal (LLC) monomer

LLC monomer used in this study is Gemini polymerizable surfactant MA11-6-11MA. Synthesis of this surfactant involves two steps (Supplementary Fig. 1). First, esterification of 11-bromo-1-undecanol and methacryloyl chloride was carried out to form methacryloyloxy as the polymerizable group. Then, the positively charged quaternary ammonium salt was covalently bonded through a quaternization reaction. The resulting material was verified using 1H NMR, with a final yield was ~60%. (Supplementary Fig. 2). Detailed synthesis procedure of MA11-6-11MA is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Preparation of LLC-loaded substrates

LLC with hexagonal columnar structure was formed by mixing MA11-6-11MA surfactant (70 wt%) and water (30 wt%). The obtained LLC mixture was added into ethanol at various mass ratios (2, 20, 50, and 100 wt%), and uniformly spread on polysulfone (PSf) supports. These supports were respectively labeled as PSf2%LLC, PSf20%LLC, PSf50%LLC, and PSf100%LLC. To facilitate ethanol evaporation, the supports were shaken at 200 rpm for 2 min on a plate shaker under a nitrogen atmosphere. After complete evaporation of ethanol, the LLC retained its self-assembled morphology, indicating that ethanol did not disrupt the self-assembly process. The LLC structures remained stably deposited on the PSf surface (Supplementary Fig. 3). Next, the LLC-coated PSf supports were then irradiated under UV (365 nm) for 60 s to initiate polymerization of the LLC monomer, forming anisotropic, solid LLC films on PSf surface.

Interfacial polymerization

To fabricate polyamide selective layer, IP reaction was conducted on top of the LLC-coated PSf supports. The pristine PSf, PSf2%LLC, PSf20%LLC, PSf50%LLC, and PSf100%LLC substrates were initially immersed in a 1 wt% PIP aqueous solution for 3 min. Excess PIP solution on the surface was removed using an air knife. Next, the PIP-saturated substrate was immersed in a 0.15 wt% TMC hexane solution to initiate poly-condensation of PIP with TMC, resulting in the formation of crosslinked polypiperazine film. To enhance water permeability, we also investigated alternative monomer concentrations—specifically, 0.5 wt% PIP and 0.1 wt% TMC—with the aim of forming a thinner selective layer with enhanced water transport. The resulting membrane was subsequently washed with pure hexane and cured in DI water at 65 °C for 10 min. The obtained NF membranes were stored in DI water at 4 °C before testing.

Characterization of membranes

Surface and cross-section morphology of NF membranes were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Gemini 450, Zeiss). Surface roughness and thickness of membrane were measured by atomic force microscopy (AFM, MultiMode, Veeco). Cross-sectional images of TFN membranes prepared were obtained using a field-emission transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-2100F, JEOL). Self-assembly textures were observed using polarized optical microscopy (POM, DM750, Leica). Surface hydrophilicity of membranes were tested by a tensiometer (Theta Flex, Biolin). Molecular structure and chemical bonding were tested by attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR, Nicolet 8700, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Surface zeta potential of membrane was evaluated using a solid surface Zeta potential analyzer (SurPASS 3, Anton Paar). Elemental content of membranes surfaces was detected by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Self-assembled ordered structures were tested on 1D and 2D small-angle X-ray diffraction (SAXS) using a diffractometer coupled with synchrotron source at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Beamlines BL16B1 and BL10U1) and the National Facility for Protein Science in Shanghai (Beamline BL19U2).

Evaluation of membranes separation performance

The performance of all NF membranes was evaluated using a lab-made system with cross-flow filtration cells (effective area of 19.5 cm2). Prior to the measurements, membrane coupons were compacted at 6 bar for 4 hours to obtain a stable water flux. Pure water flux was determined at 5 bar and cross-flow velocity of 1.07 cm s−1 at 25 °C. Salt rejection was determined using 1 g L−1 Na2SO4 or 50 mM NaCl solution as a feed solution. Salt rejection, R, was calculated by:

where Cf and Cp represent conductivity of feed and the permeate.

Membrane selectivity was tested with a mixture solution containing 5 mM NaCl (LiCl) and 1 mM CaCl2 (MgCl2). Selectivity of monovalent cations (Na+/Li+) to divalent cations (Ca2+/ Mg2+) was calculated using:

where Cf and Cp represent the ion concentrations in the feed and permeate, respectively. Average selectivity for each membrane type is calculated by averaging the selectivity of Li+ and Mg2+ obtained from individual membrane coupons.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Petersen, R. J. Composite reverse osmosis and nanofiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 83, 81–150 (1993).

Hilal, N., Al-Zoubi, H., Darwish, N. A., Mohamma, A. W. & Abu Arabi, M. A comprehensive review of nanofiltration membranes: treatment, pretreatment, modelling, and atomic force microscopy. Desalination 170, 281–308 (2004).

Werber, J. R., Osuji, C. O. & Elimelech, M. Materials for next-generation desalination and water purification membranes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–15 (2016).

Mohammad, A. W. et al. Nanofiltration membranes review: recent advances and future prospects. Desalination 356, 226–254 (2015).

Luo, J. & Wan, Y. Effects of pH and salt on nanofiltration—a critical review. J. Membr. Sci. 438, 18–28 (2013).

Marchetti, P., Jimenez Solomon, M. F., Szekely, G. & Livingston, A. G. Molecular separation with organic solvent nanofiltration: a critical review. Chem. Rev. 114, 10735–10806 (2014).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500323 (2016).

Lau, W. J., Ismail, A. F., Misdan, N. & Kassim, M. A. A recent progress in thin film composite membrane: a review. Desalination 287, 190–199 (2012).

Lu, X., Arias Chavez, L. H., Romero-Vargas Castrillon, S., Ma, J. & Elimelech, M. Influence of active layer and support layer surface structures on organic fouling propensity of thin-film composite forward osmosis membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 1436–1444 (2015).

Ahmad, A. & Ooi, B. Properties–performance of thin film composites membrane: study on trimesoyl chloride content and polymerization time. J. Membr. Sci. 255, 67–77 (2005).

Gui, L. et al. Ultrafast ion sieving from honeycomb-like polyamide membranes formed using porous protein assemblies. Nano Lett. 20, 5821–5829 (2020).

Freger, V. Nanoscale heterogeneity of polyamide membranes formed by interfacial polymerization. Langmuir 19, 4791–4797 (2003).

Lu, X. & Elimelech, M. Fabrication of desalination membranes by interfacial polymerization: history, current efforts, and future directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6290–6307 (2021).

Meng, F. et al. Recent advances in membrane bioreactors (MBRs): membrane fouling and membrane material. Water Res. 43, 1489–1512 (2009).

Xu, P., Drewes, J. E., Kim, T.-U., Bellona, C. & Amy, G. Effect of membrane fouling on transport of organic contaminants in NF/RO membrane applications. J. Membr. Sci. 279, 165–175 (2006).

Ritt, C. L., Werber, J. R., Deshmukh, A. & Elimelech, M. Monte Carlo simulations of framework defects in layered two-dimensional nanomaterial desalination membranes: implications for permeability and selectivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 6214–6224 (2019).

Liu, C., Lee, J., Ma, J. & Elimelech, M. Antifouling thin-film composite membranes by controlled architecture of zwitterionic polymer brush layer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2161–2169 (2017).

Ni, L. et al. Synchronizing formation of polyamide with covalent organic frameworks towards thin film nanocomposite membrane with enhanced nanofiltration performance. J. Membr. Sci. 646, 120253 (2022).

Vatanpour, V., Madaeni, S. S., Moradian, R., Zinadini, S. & Astinchap, B. Fabrication and characterization of novel antifouling nanofiltration membrane prepared from oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotube/polyethersulfone nanocomposite. J. Membr. Sci. 375, 284–294 (2011).

Zhu, Y. et al. Single-walled carbon nanotube film supported nanofiltration membrane with a nearly 10 nm thick polyamide selective layer for high-flux and high-rejection desalination. Small 12, 5034–5041 (2016).

Karan, S., Jiang, Z. & Livingston, A. G. Sub–10 nm polyamide nanofilms with ultrafast solvent transport for molecular separation. Science 348, 1347–1351 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. Large-area graphene-nanomeshcarbon-nanotube hybrid membranes for ionic and molecular nanofiltration. Science 364, 1057–1062 (2019).

Zhu, J. et al. MOF-positioned polyamide membranes with a fishnet-like structure for elevated nanofiltration performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 16313–16322 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. Tannic acid/Fe(3+) nanoscaffold for interfacial polymerization: toward enhanced nanofiltration performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 9341–9349 (2018).

Song, Q. et al. A zwitterionic copolymer-interlayered ultrathin nanofilm with ridge-shaped structure for ultrapermeable nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 657, 120679 (2022).

Tan, Z., Chen, S., Peng, X., Zhang, L. & Gao, C. Polyamide membranes with nanoscale Turing structures for water purification. Science 360, 518–521 (2018).

Yang, G., Zhang, Z., Yin, C., Shi, X. & Wang, Y. Polyamide membranes enabled by covalent organic framework nanofibers for efficient reverse osmosis. J. Polym. Sci. 60, 2999–3008 (2021).

Lianchao, L., Baoguo, W., Huimin, T., Tianlu, C. & Jiping, X. A novel nanofiltration membrane prepared with PAMAM and TMC by in situ interfacial polymerization on PEK-C ultrafiltration membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 269, 84–93 (2006).

Zhao, Y. et al. Capillary-assisted fabrication of thin-film nanocomposite membranes for improved solute–solute separation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5849–5859 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. A critical review on thin-film nanocomposite membranes with interlayered structure: mechanisms, recent developments, and environmental applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 15563–15583 (2020).

Cui, W., Li, J. & Decher, G. Self-assembled smart nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 28, 1302–1311 (2015).

Negrini, R. & Mezzenga, R. pH-responsive lyotropic liquid crystals for controlled drug delivery. Langmuir 27, 5296–5303 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. A lyotropic liquid-crystal-based assembly avenue toward highly oriented vanadium pentoxide/graphene films for flexible energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1606269 (2017).

Ibrahim, A. R. et al. p-methoxy azobenzene terpolymer as a promising energy-storage liquid crystal system. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 22472–22482 (2021).

Brake, J. M., Daschner, M. K., Luk, Y.-Y. & Abbott, N. L. Biomolecular interactions at phospholipid-decorated surfaces of liquid crystals. Science 302, 2094–2097 (2003).

Woltman, S. J., Crawford, G. P. & Jay, G. D. Liquid-crystal materials find a new order in biomedical applications. Nat. Mater. 6, 929–938 (2007).

Zhou, M. et al. New type of membrane material for water desalination based on a cross-linked bicontinuous cubic lyotropic liquid crystal assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9574–9575 (2007).

Feng, X. et al. Precise nanofiltration in a fouling-resistant self-assembled membrane with water-continuous transport pathways. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav9308 (2019).

Elimelech, M. & Phillip, W. A. The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology, and the environment. Science 333, 712–717 (2011).

Abe, M. et al. Polymerizable cationic gemini surfactant. Langmuir 22, 8293–8297 (2006).

Sarkar, P., Modak, S. & Karan, S. Ultraselective and highly permeable polyamide nanofilms for ionic and molecular nanofiltration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007054 (2020).

Wavhal, D. S. & Fisher, E. R. Modification of polysulfone ultrafiltration membranes by CO 2 plasma treatment. Desalination 172, 189–205 (2005).

Feng, X. et al. Single crystal texture by directed molecular self-assembly along dual axes. Nat. Mater. 18, 1235–1243 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Elements provide a clue: nanoscale characterization of thin-film composite polyamide membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 16917–16922 (2015).

Yan, H. et al. The porous structure of the fully-aromatic polyamide film in reverse osmosis membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 475, 504–510 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Novel sulfonated thin-film composite nanofiltration membranes with improved water flux for treatment of dye solutions. J. Membr. Sci. 394, 218–229 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Nanoparticle-templated nanofiltration membranes for ultrahigh performance desalination. Nat. Commun. 9, 2004 (2018).

Yuan, B., Zhao, S., Hu, P., Cui, J. & Niu, Q. J. Asymmetric polyamide nanofilms with highly ordered nanovoids for water purification. Nat. Commun. 11, 6102 (2020).

Coronell, O., González, M. I., Mariñas, B. J. & Cahill, D. G. Ionization behavior, stoichiometry of association, and accessibility of functional groups in the active layers of reverse osmosis and nanofiltration membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 6808–6814 (2010).

Chen, D., Werber, J. R., Zhao, X. & Elimelech, M. A facile method to quantify the carboxyl group areal density in the active layer of polyamide thin-film composite membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 534, 100–108 (2017).

Li, Q. & Elimelech, M. Organic fouling and chemical cleaning of nanofiltration membranes: measurements and mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 4683–4693 (2004).

Zelner, M., Jahn, P., Ulbricht, M. & Freger, V. A mixed-charge polyelectrolyte complex nanofiltration membrane: preparation, performance and stability. J. Membr. Sci. 636, 119579 (2021).

Han, S. et al. Microporous organic nanotube assisted design of high performance nanofiltration membranes. Nat. Commun. 13, 7954 (2022).

Zhao, C. et al. Polyamide membranes with nanoscale ordered structures for fast permeation and highly selective ion-ion separation. Nat. Commun. 14, 1112 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52170094) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility of BL16B1 and BL10U1, and the National Facility for Protein Science in Shanghai of BL19U2 for the assistance on SAXS and WAXS measurements. Some material characterization for this study was carried out at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) Center for Micro- and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication, and the Instruments Center for Physical Science at USTC. The computational analysis involving molecular dynamics simulation was conducted at the Supercomputing Center at USTC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. conceived the initial idea. X.L. and F.X. designed the experiments. F.X. carried out the experiments. X.L., X.F., and Y.Y. provided insights into characterization and data analysis. F.X. and X.L. wrote the first draft, and X.L. edited the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, F., Yang, Y., Feng, X. et al. Self-assembled lyotropic liquid crystal interlayer regulated interfacial polymerization for modulating structure and performance of nanofiltration membranes. Nat Commun 17, 1367 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68116-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68116-2