Abstract

The Greenland Ice Sheet will significantly contribute to global mean sea-level rise this century. However, glacial isostatic adjustment is expected to cause regional sea-level fall around Greenland as the land rebounds and the gravitational pull of the shrinking ice sheet decreases. A fall in local sea level has implications for Greenlandic communities whose economy, near-shore infrastructure, and food security are vulnerable to coastal changes, and for the dynamics of marine-terminating glaciers. In this study, we use a glacial isostatic model paired with sea-level and vertical land motion observations to predict future sea-level change in this region. We find that local sea level will fall around the island by 2100 CE (relative to 2017 CE) reaching a median value and likely range (17th-83rd percentile) of − 0.9 m [ − 1.2 m to − 0.66 m] and − 2.5 m [ − 3.8 m to − 1.7 m] for Representative Concentration Pathways 2.6 and 8.5, respectively, with viscous effects contributing 20–40% of the predicted local sea-level signal associated with future ice change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As anthropogenic climate change continues, both the thermal expansion of ocean water and the melting of ice sheets and glaciers will contribute to a rise in global mean sea level (GMSL). The Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS) is expected to be a primary contributor to rising sea levels, projected to cause a median value and likely range (17th-83rd percentile) of GMSL rise by 2100 CE relative to 1995–2014 CE of 60 mm [10 mm to 100 mm] for Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 1–2.6 and 130 mm [90 mm to 180 mm] for SSP5-8.51. However, little research has been done to explore how the melting ice sheet will change sea level around the coastlines of Greenland itself. Since Greenland has nearly 60,000 permanent inhabitants, all of whom live in towns and settlements along the coast, changing sea levels will impact the majority of Greenland’s population. Sea-level change around Greenland deviates substantially from the global mean mainly due to glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA), which is the deformational response of the solid Earth and associated modulation in Earth’s gravitational field and rotational axis to changes in ice and ocean mass through time2,3. In the near field of a melting ice sheet, GIA causes a local sea-level fall, as the reduction in ice mass causes the Earth beneath it to rebound and a decrease in the gravitational attraction of the ice sheet causes the sea surface to lower4. This contrast in the sign of expected local sea-level change from that of the majority of other vulnerable coastlines around the world motivates the need for region-specific projections of sea-level change for Greenland. In this study, we will use the term relative sea level (RSL) to denote local sea surface height relative to bedrock topography5.

In order to predict future changes in sea level due to GIA around Greenland, we need to know past and future ice-mass change, as well as the rheology of Earth’s interior, which determines the magnitude and timescale of the solid Earth response. Regarding past ice-sheet changes, the GrIS peaked in extent around 16.5 kyr ago when it held an excess volume relative to present of approximately 5 m ice-equivalent sea level and extended over large swaths of the continental shelf 6. While the timing of its retreat from this position is believed to have varied spatially across the ice sheet6, the majority of the GrIS receded to or inland of the present-day shoreline by 10 ka6,7,8,9. The early-to-mid Holocene was marked by higher-than-present temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere10,11 and much of the GrIS and its peripheral glaciers retreated past their contemporary extent11,12,13,14. This was followed by the readvance of the GrIS past its present position during the Neoglacial cooling period, which began approximately 5000 yrs ago and culminated in the Little Ice Age (LIA) around 800–120 yrs ago15. The mass of the GrIS and its peripheral glaciers is estimated to have been 14,862 ± 3758 Gt larger than present during the LIA16,17,18. The onset of ice retreat from its LIA maximum extent varies spatially17, but is generally centered around 1850–1900 CE16. More recently, measurements from satellite altimetry reveal that the GrIS decreased in surface elevation along the majority of its margins, excluding those on the central east coast and a small area in the southeast, during the period 2012–2017 CE19. Today, the rate of mass loss from the GrIS and its peripheral glaciers is 262 ± 39 Gt/yr20 and 42 ± 6 Gt/yr21, respectively. Though projections to 2100 CE show decreases in ice thickness along all margins of the GrIS, the southwestern margin is especially susceptible to change, partially reflecting the pattern of surface elevation change seen today22. Accurately incorporating the evolution of the GrIS from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to 2100 CE is fundamental to reliably modeling the viscoelastic response of the Earth and the reshaping of the ocean’s surface to these mass changes.

Knowledge of Earth’s internal structure, especially mantle rheology, is equally important for accurately capturing the GIA response to changing surface loads. In GIA studies, Earth’s mantle is often considered to be a radially-symmetric (i.e., 1D) viscoelastic Maxwell body4. Solid Earth parameters are typically determined by tuning GIA models to fit paleo RSL data6,23,24,25, modern GPS data16,26,27, and Earth’s rotation parameters28. Lecavalier et al.6 find that GIA models forced by a GrIS deglaciation history (termed Huy3) derived from a dynamical ice-sheet model best fit RSL data in Greenland when using a 120 km thick elastic lithosphere and upper and lower mantle viscosities of 5 × 1020 Pa s and 2 × 1021 Pa s, respectively. However, these values are not consistent across all studies that tune their model parameters to fit Greenland RSL data. Tarasov & Peltier24 find that their GrIS history performs well when coupled with a lithosphere of 90 km. Fleming & Lambeck25 also show a preference for a thinner lithosphere (80 km), in addition to higher values for the viscosities of the upper mantle (4 × 1021 Pa s) and lower mantle (10 × 1021 Pa s). Each of these studies finds that their predictions of RSL are unable to match all of the observed RSL data, a consequence of uncertainties in both the ice reconstruction and prescribed Earth parameters. Regarding the latter, one assumption in all of these studies is that Earth’s properties vary with depth alone when evidence for a more complex, laterally-varying (i.e., 3D) Earth structure below Greenland is present[e.g. 29. Milne et al.30 predict Holocene RSL in Greenland using a 3D GIA model paired with Huy3 and find that this model can improve data-model residuals in some locations.

Contemporary observations of GIA include vertical land motion (VLM) measured with permanent Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS). Present-day VLM recorded at the 57 permanent GNSS stations that span coastal Greenland, called GNET, is caused by deformation driven by ice changes that have occurred in the past (most importantly over the last deglaciation, i.e., last 26 kyr) and that are occurring today (i.e., during the recorded period)31. These records are often corrected for the deformation caused by coeval ice change (assumed to be elastic), so that trends in the data can be directly compared to predictions of VLM driven by past ice changes from GIA models16,20,26,32. However, these models, which are tuned to fit paleo RSL data, consistently underpredict VLM observed from GNET16,20,26,30,32,33. One source of uncertainty in this comparison comes from the incomplete removal of the trend in elastic deformation. Berg et al.20 consider both longer time series (~ 2007–2023) of GNSS data and mass changes from the GrIS, its peripheral glaciers, and glaciers in the Canadian Arctic to derive more accurate elastic VLM solutions that can improve constraints on GIA models. They find that discrepancies still remain between their elastic-corrected GNET data and predictions from multiple GIA models forced by deglacial ice change. Milne et al.30 consider whether the influence of lateral variations in Earth structure could help explain poor fits to the present-day VLM observations, but conclude that the 3D viscosity structures considered in their study do not explain the large residuals.

Adhikari et al.16 propose that this inconsistency is due to the exclusion of ongoing deformation caused by more recent ice-mass change that has occurred since the beginning of the LIA. They show that including a LIA ice history paired with a reduced mantle viscosity for the time period encompassing these mass changes allows for a better fit between their predicted present-day VLM and the observed values at the majority of GNET stations. They suggest that this lowering in mantle viscosity over the timeframe of ice-sheet changes since the beginning of the LIA hints at the presence of transient deformation beneath Greenland. Transient deformation is an extension of the classical Maxwell rheology. While the latter consists only of an instantaneous elastic response and a steady-state viscous creep, transient deformation, as is, for example, captured by a Burgers rheology, allows for additional dissipative mechanisms which act to lower the apparent viscosity over short periods. This deformation style is supported by high-temperature high-pressure laboratory experiments of rock deformation34,35 and has been explored in other GIA studies e.g.,36,37,38,39,40. In the case of loading events that occur over centennial timescales (like the LIA), the viscosity of the mantle can effectively be lower than that inferred for longer-timescale events (like the LGM or mantle convection), allowing the mantle to deform more quickly and with a greater magnitude. Paxman et al.41 use rheological laws paired with an inference of the mantle thermodynamic state from seismic tomography to show that one indeed would expect a lowering in apparent viscosity for ice-mass changes that occur over decadal-to-centennial timescales consistent with LIA mass loading. However, Pan et al.42 caution that a sub-lithospheric low-viscosity layer with a regular Maxwell rheology would also be able to explain both deglacial RSL data and present-day VLM if the LIA ice history is included in the GIA model. Further work is needed to understand the possible extent of a sub-lithospheric low-viscosity layer around and below the cratonic keel of Greenland29,43.

The goal of this study is to produce reliable projections of sea-level change around Greenland for this century. We build on previous work by accounting for both lateral variability in viscosity over long timescales and a reduced mantle viscosity over shorter timescales in our projections. We assimilate paleo RSL data from the Holocene as well as VLM data from GNET stations to reduce uncertainty in our knowledge of solid Earth deformation. Finally, we produce a complete estimate of future sea-level change around Greenland by projecting sea level using a GIA model forced with predictions of past and future ice-sheet behavior and combining it with additional sources of future sea-level change (e.g., global-ocean thermal expansion and melt of global glaciers) under a low and high emission scenario.

In this work, we find that RSL will fall along Greenland’s coast, reaching a median value and likely range of −0.9 m [−1.2 m to −0.66 m] and −2.5 m [−3.8 m to −1.7 m] for Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 2.6 and 8.5, respectively, at 2100 CE relative to 2017 CE. The viscous contribution to projected RSL associated with future ice-sheet change is 20–40%, emphasizing the importance of modeling the full viscoelastic response to projected surface load changes over this century. A sea-level fall of this magnitude has implications for coastal communities and could affect ice-sheet dynamics at marine-based outlets.

Results and discussion

To make projections of 21st century sea-level change around Greenland we consider 3 contributions: (1) future sea-level change driven by historical ice-mass changes over the deglaciation (30 ka to 1 ka), (2) future sea-level change driven by historical and projected ice-mass changes from the LIA (beginning at 1000 CE) to 2100 CE, and (3) future sea-level change driven by processes unrelated to ice-sheet mass change and associated GIA (which we label the “other processes" contribution). For (1), we use a suite of 65 available 3D Maxwell GIA simulations (Supplementary Table 1) and weight them based on their fit to Holocene RSL data. For (2), we use a suite of 14,040 1D Maxwell GIA simulations. We first predict present-day VLM in Greenland driven by the LIA and compare these to observations of uplift measured at 55 GNET stations. In order to make a direct comparison, we correct the observed VLM for uplift associated with deglacial and coeval mass changes, the former of which is calculated in step (1) and the latter is taken from Berg et al.20. We further account for potential differences between the reference frame used in the 1D GIA model and that used for the VLM observations (Supplementary Section 1). We perform a Bayesian inversion to identify the distribution of most likely ice and Earth parameters varied in the 1D GIA model and create a posterior prediction of present-day VLM driven by the LIA in Greenland. We then use these optimal parameters to create a suite of 1D Maxwell GIA runs forced by LIA-to-2100 CE ice-mass change, using an ensemble of projections of Greenland and Antarctic ice change for both RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.522,44. These represent low and high scenarios for radiative forcing to 2100 CE45, which are considered in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Reports. Modeling contributions (1) and (2) separately allows for the consideration of different viscosities over different timescales to approximate a transient response. An assumption of 1D viscosity over shorter timescales (contribution 2) is made to improve computational efficiency and because the behavior of the mantle is inferred to be more laterally homogeneous over decadal-to-centennial timescales than over multi-millennial timescales41. For (3), we use published estimates1,46,47,48 associated with the IPCC AR6 for the contribution to sea-level change around Greenland from thermal expansion, ocean dynamics, land-water storage, and global glaciers. Projections of RSL from these contributions are provided for SSP1–2.6 and SSP5–8.5, which combine socioeconomic narratives defined by the SSPs with emission pathways based on the RCPs.

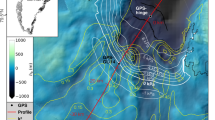

Present-day VLM from deglacial mass change

Our calculations indicate that GIA from deglacial ice loss causes present-day uplift of up to 3.3 mm yr−1 along the northern and eastern coasts of Greenland and subsidence at rates less than 2.5 mm yr−1 in the south and west (Fig. 1). Our modeled rates of present-day VLM caused by the deglaciation are in general agreement with previous estimates6,27,30,31. The spatial pattern is governed by multiple processes. First, uplift in response to overall ice-sheet retreat since the LGM dominates the northeastern margin, which began to retreat at 12 ka before remaining relatively stable around its present-day position since the mid-Holocene6,24. Second, subsidence in response to late-Holocene regrowth of the GrIS during the Neoglacial period contributes to negative VLM along the southwest coast6,49. And, third, subsidence due to Greenland’s position on the peripheral bulge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet results in larger subsidence rates along the western coast of Greenland compared to the east. Like previous studies16,20,26,30,32, we find that the rates of VLM caused by deglacial ice loss alone are insufficient to fit the elastic-corrected observations at the majority of GNET stations. The largest discrepancy is seen along the southeastern coast, where the residual between the elastic-corrected observed and the modeled deglacial VLM rates reaches a maximum of 6.2 mm yr−1.

The weights for the deglacial GIA simulations (normalized so that they sum to one) fall within the range of 0.0081 to 0.0227, and do not deviate substantially from the value that would be assigned if all predictions were weighted equally (1/65 = 0.0154). Our highest-weighted simulation is that from Antwerpen et al.49, which utilizes the Huy36 ice history and a combination of 2 seismic tomography models50,51 to infer the 3D viscosity structure of the mantle. Comparing the highest-weighted simulation with the lowest-weighted simulation from Austermann et al.52, in which the Earth structure is the same as that used in Antwerpen et al.49 but the ice history is given by ICE-6G53 instead of Huy3, suggests that the Huy3 ice reconstruction (rather than the Earth structure) is the key feature of the best-fitting prediction. This is expected, as additional and improved data constraints were used in the creation of Huy3 compared to the GrIS portion of ICE-6G.

Bayesian inversion of present-day VLM from LIA mass change

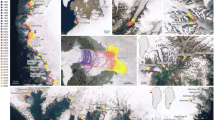

Incorporating VLM from LIA mass changes has been shown to reduce the residuals between modeled VLM and observed VLM within the period 2011–2017 CE16. In this study, the contribution of LIA mass change to present-day VLM is determined through assimilating VLM observations into our modeling framework. Figure 2 shows this quantity’s prior estimate (blue markers, note that this shows LIA’, which includes the correction for a difference in the reference frame between model predictions and observations), which is the unweighted average taken across our entire suite of GIA model predictions, and posterior estimate (red markers, note this also shows LIA’), which is the weighted average taken after performing the Bayesian inversion. There is only a slight difference in mean between our prior and posterior solutions, as the model parameters used in this study (Table 1) were sampled from the posterior distribution of parameters from Adhikari et al.16. Nonetheless, the posterior solutions have decreased variance at all stations and the predicted mean is closer to the observed mean at 34 out of the 55 stations when compared to the prior, which demonstrates learning from the data.

Black bars show the mean (solid line) and 2-σ uncertainty (shaded region) of observed uplift rates at 55 GNET stations. Blue bars show the mean (solid line) and 2-σ uncertainty (shaded region) of the prior uplift rate predictions. Red bars show the mean (solid line) and 2-σ uncertainty (shaded region) of the posterior uplift rate predictions. The predictions (termed LIA') are based on the sum of present-day uplift rates driven by the LIA and a reference-frame correction, while the observations are based on the observed uplift rates corrected for the elastic and deglacial contributions. Station numbers are shown on the map of Greenland and correspond to the white circles shown in Fig. 3a.

The posterior prediction of the LIA contribution to present-day VLM (LIA-VLM) shows positive uplift rates everywhere in Greenland, with the highest magnitude rates of up to 5.7 mm yr−1 seen along the southeast coast (Fig. 3). The standard deviation of the posterior solution has a similar pattern to the posterior mean and is 20–30% of its magnitude (averaged across GNET stations). Regions with outlet glacier systems whose mass has decreased significantly since the LIA, specifically the Kangerlussuaq Glacier and Helheim Glacier (station 23, Fig. 2) in the southeast15,16,17, show higher magnitudes of uplift than other regions along the ice sheet margin. The average reference frame contribution to the observed uplift rates (Supplementary Fig. 1) is between −1.8 mm yr−1 and 0.45 mm yr−1, with the maximum magnitude contribution seen along the southeast coast. The posterior LIA-VLM rates calculated in this study are of similar magnitude and spatial pattern to those predicted by Adhikari et al.16, suggesting that the prediction of present-day LIA-VLM is not heavily influenced by our use of different observed, elastic, and deglacial VLM rates or the difference in our methods for weighting the LIA-GIA model predictions.

Our solutions of LIA-VLM are sensitive to both mantle viscosity and lithospheric thickness and insensitive to LIA termination time and mass anomaly. Preferred values for mantle viscosity and lithospheric thickness are 6.3–7.0 × 1019 Pa s (probability = 0.33) and 200 km (probability = 0.17), respectively. The covariance between these parameters shows the expected trade-off where a thicker lithosphere requires a lower mantle viscosity (Supplementary Fig. 2). Our preferred mantle viscosity is significantly smaller than viscosities found by fitting deglacial data6,9,25. However, it is in agreement with the inferred apparent viscosity of the mantle beneath Greenland for centennial timescales determined by the use of full-spectrum rheological models that examine the influence of transient deformation41. Following this work and the interpretation of Adhikari et al.16, our LIA viscosity estimate may be indicative of transient deformation in the mantle beneath Greenland. Our preferred lithospheric thickness is larger than the best-fitting estimates found by reducing the misfit of deglacial GIA models to observations9,25, however, a higher apparent lithospheric thickness is expected for shorter LIA timescales41.

Adhikari et al.16 find a preferred viscosity of 6–11 × 1019 Pa s with little sensitivity to lithospheric thickness. This differs slightly from our results, which may be due to different choices in the data and their processing (between Adhikari et al.16 and Berg et al.20) or due to differences in the inference framework. To test these two options, we repeat our analysis with the observed and elastic VLM rates from Adhikari et al.16 instead of Berg et al.20. We find that this produces a preferred viscosity of 6–7 × 1019 Pa s (in line with our original inference) and a preferred lithospheric thickness of 60–80 km (different to both our original inference and the result by Adhikari et al.16). This shows that both choices in the data and the inference scheme lead to differences in the inferred Earth structure.

Projections of RSL change

Projections of RSL change along coastal Greenland to 2100 CE are a combination of changes driven by deglacial GIA (Fig. 4a, b), LIA GIA (Fig. 4c, d), GIA associated with future ice-sheet change (Fig. 4e, h), and processes unrelated to ice-sheet change and associated GIA (i.e., the “other processes"; Fig. 4i–l). All projections reported in this study are given as the median and likely range (17th–83rd percentile) and are relative to 2017 CE. The deglacial contribution causes a slight rise in RSL, reaching 0.21 m [0.17 m to 0.26 m], in west and southeast Greenland due mainly to Laurentide forebulge collapse and a fall in RSL, reaching −0.17 m [−0.46 m to −0.10 m], in the northeast caused by ongoing uplift in response to ice loss since the LGM (Fig. 4a). The LIA contributes a RSL fall along the entire coastline and is a significant influence in the northwest, where it reaches −0.33 m [−0.40 m to −0.24 m], and in the southeast, where it reaches −0.41 m [−0.50 m to −0.30 m] (Fig. 4c). The contribution from future ice-sheet mass change is calculated by pairing an ensemble of ice-sheet projections for RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.522,44 with preferred parameters from our LIA Bayesian inversion (see “Methods”). This contribution produces falling sea levels everywhere around Greenland (driven by mass loss from the GrIS), with the largest changes, reaching −0.88 m [−1.1 m to −0.73 m] for RCP 2.6 and −2.5 m [−3.9 m to −1.9 m] for RCP 8.5, occurring adjacent to the GrIS margin where melting is projected to be greatest (Fig. 4e, g).

Ensemble median and likely range (17th–83rd percentile) of the contributions to RSL change at 2100 CE relative to 2017 CE. RSL change is driven by historical ice changes that occurred during the deglaciation (a, b), the Little Ice Age (c, d) and projected ice-sheet changes under Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6 (e, f) or RCP 8.5 (g, h). Other processes, including thermal expansion and ocean dynamics, global glacier change, and land water storage for SSP1-2.6 (i, j) or SSP5-8.5 (k, l), also contribute to RSL change over this century. Projections do not exist within the white areas of panels (i–l).

We performed an additional calculation to quantify the relative influence of solid Earth deformation versus gravitational effects on our projection of RSL change driven by LIA-2100 CE ice load variations. Gravitational effects include both the ice and the solid Earth’s pull on the ocean’s surface and a uniform gravitational shift caused by the input of meltwater into the ocean. We calculate this by running the GIA code from the LIA to 2100 CE using the ensemble of ice-sheet projections for RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5 with one parameter combination that performs well in fitting observations (mantle viscosity = 7.9 × 1019 Pa s, lithospheric thickness = 200 km, LIA termination time = 1870 CE, LIA mass anomaly = 16,500 Gt) and separating the two components. We find that RSL at 2100 CE caused by ice-mass changes from the LIA to 2100 CE is dominantly driven by solid Earth deformation, with sea-level changes caused by gravitational effects constituting ~ 0–20% of the total for RCP 2.6 and ~ 10–30% of the total for RCP 8.5, depending on location around the coast (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The contribution to RSL at 2100 CE from thermal expansion and ocean dynamics, global glacier change, and land water storage1,46,47,48 is positive along Greenland’s coasts except for a small area of RSL fall in the northwest (Fig. 4i, k). Thermal expansion and ocean dynamics are the primary drivers of RSL rise along the coast, causing up to 0.28 m [0.15 m to 0.42 m] and 0.62 m [0.36 m to 0.87 m] at 2100 CE for SSP1–2.6 and SSP5–8.5, respectively. The contribution of land water storage to RSL change in Greenland is also positive, but insignificant and does not reach above 0.03 m [0.02 m to 0.04 m] for either scenario. The fall in RSL in northwest Greenland is caused by projected ice loss from the peripheral glaciers of Arctic Canada and their resulting GIA signal, which was calculated using an elastic Earth structure1,54. It reaches −0.38 m [−0.65 m to −0.10 m] for SSP1-2.6 and −1.0 m [−1.3 m to −0.70 m] for SSP5-8.5. Calculating the viscoelastic GIA response to future changes in mountain glaciers around Greenland and Arctic Canada using our preferred Earth structure for sub-centennial timescales may significantly increase the magnitude of this component.

Summing all contributions leads to a RSL change at 2100 CE (Fig. 5a, b) that, in pattern, resembles the contribution from GIA associated with the ice-sheet projections (Fig. 4e–h). At 2100 CE, the contributions to RSL change from GIA driven by past ice-mass variations and from the other processes have opposing signals around the coastline and tend to cancel out. The total projected fall in sea level reaches a maximum value of −0.90 m [−1.2 m to −0.66 m] near Sermeq Kujalleq (formerly known as Jakobshavn Isbrae) for RCP 2.6 and −2.5 m [−3.8 m to −1.7 m] near Helheim Glacier for RCP 8.5. Note that here and for the remainder of the text, we refer to the RSL projections as representing emissions scenarios RCP 2.6 and 8.5, which include the SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 projection components for the other processes. The spatial pattern of the likely range of total RSL at 2100 CE demonstrates that the largest source of uncertainty in the projections comes from the different ways in which the future ice models22 project marine-terminating glacier response to climate warming (Fig. 5c, d). This is illustrated further in Supplementary Fig. 4, which shows projected RSL change at 2100 CE under RCP 8.5 for each of the individual ice-sheet models considered in this study.

Ensemble median of the total RSL change at 2100 CE relative to 2017 CE, determined by summing all of the contributions shown in Fig. 4 for RCP 2.6 (a) and RCP 8.5 (b). The likely range (17th–83rd percentile) of the total RSL at 2100 CE is shown for RCP 2.6 (c) and RCP 8.5 (d). White stars in (c) represent locations of the 6 settlements whose projections to 2100 CE are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Black circles in (d) represent locations of 3 large marine-terminating glaciers discussed in this paper. The locations of settlements/glaciers are labeled accordingly: K (Kangerlussuaq Glacier), H (Helheim Glacier), T (Tasiilaq), Q (Qaqortoq), N (Nuuk), I (Ilulissat), SK (Sermeq Kujalleq), Ku (Kullorsuaq), P (Pituffik). Projections do not exist within the white areas on each map.

Time series of RSL from 2017–2100 CE for RCP 8.5 in Tasiilaq and Nuuk demonstrate that each contribution to RSL, and therefore the total RSL change, will vary for different settlements in Greenland (Fig. 6). In Tasiilaq, the most populous settlement along the eastern coast, made up of nearly 2000 inhabitants, RSL is projected to fall by -1.4 m [−1.8 m to −0.95 m] for RCP 8.5. Projected ice-sheet mass loss contributes −1.6 m [−1.9 m to −1.2 m] to this RSL fall, which is further exacerbated by the RSL fall driven by LIA mass loss and partially offset by the RSL rise from other processes. Nuuk, the capital of Greenland and the most populated area on the island with 19,611 inhabitants, is projected to experience a RSL fall of −0.83 m [−1.2 m to −0.54 m] by 2100 CE for RCP 8.5. Compared to Tasiilaq, the RSL fall driven by projected ice change and the LIA is smaller in Nuuk. This is combined with a larger RSL rise from deglacial ice change and other processes, leading to the smaller total RSL fall seen in Nuuk over this century. Though the magnitude of RSL change and the breakdown of its contributions will vary along Greenland’s coasts, RSL is projected to fall for both RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5 at all of the six selected settlements discussed in this study (shown with the white stars in Fig. 5c and discussed further in Supplementary Section 2). For all locations considered here, it is noteworthy that projections for the two future emissions scenarios (RCP 2.6 vs. 8.5) only start to diverge around 2050 CE, which is consistent with prior work on sea-level projections globally[e.g.1,55,56 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

GIA associated with deglacial ice change (orange), Little Ice Age ice change (yellow), projected ice-sheet change (blue), and processes unrelated to ice-sheet change and associated GIA (green) all contribute to the total change in RSL (red) projected in Tasiilaq and Nuuk under RCP 8.5. The solid line represents the ensemble median, and the shaded region is the likely range (17th–83rd percentile). The bars on the right represent the 5th-95th percentile ranges of projected RSL at 2100 CE. Projections are relative to 2017 CE.

The most recent Assessment Report (AR6) of the IPCC includes regional projections of sea-level change at 2100 CE relative to a 1995–2014 CE baseline1. These differ from our Greenlandic projections in both magnitude and sign. For SSP1-2.6, IPCC AR6 projects a RSL rise on the order of half a meter or less along most of Greenland’s coasts, except the northern and northeastern portions, where a RSL fall is projected. For SSP5-8.5, projected RSL change is similar to that for SSP1-2.6 in most areas, but RSL fall is now projected to occur in the northwest near Kullorsuaq and is stronger along the northern coast. Our projections differ from those in AR6 in three ways: (1) how GIA in response to past ice melt is calculated, (2) how GIA in response to future ice melt is calculated, and (3) the ice-sheet models that are used for future projections. Regarding the first point, the authors of AR6 estimate RSL caused by VLM from GIA driven by historical ice changes and additional processes with a Gaussian process regression method57 that utilizes tide-gauge data. This dataset does not include tide-gauges in Greenland, making their inference for the long-term VLM component of RSL change in Greenland uncertain. The authors of AR6 recognize the limitations in this method and assign their projections of long-term VLM and GIA low-to-medium confidence, stating that for many regions, a regional analysis would result in projections of greater confidence1. Regarding point (2), the authors of AR6 use a sea-level equation solver54 with an elastic Earth structure. Viscous deformation associated with future ice change, which we estimate to be significant (see next section), is not included. Both factors likely cause AR6 projections to under-predict the amount of RSL fall in Greenland over the next century. Lastly, regarding point (3), we highlight that our RSL projections were made using future ice-sheet mass changes from ISMIP6 simulations that were forced by CMIP5 (and not CMIP6) climate output. The range of climate sensitivities represented in the ensemble of CMIP6 models has an upper tail that exceeds the range of climate sensitivities from the CMIP5 models used to create the ice-sheet projections considered in this study58. Therefore, the ice-sheet projections used here represent a more conservative-to-moderate subset of those considered in AR6.

Implications of reduced mantle viscosity for sea-level projections

The ramifications of considering a lower mantle viscosity applied to sub-centennial timescales for projections of sea-level change around Greenland are quantified in Fig. 7, which shows the elastic and viscous contributions to RSL change at 2100 CE driven by projected ice-sheet mass loss. If the viscosity of the solid Earth is taken to be the steady-state viscosity used for long timescale loading events, it is common to calculate GIA associated with projections of ice-mass change using an elastic Earth structure[e.g., 1,54,59, as the viscosity is too high and timescale too short for there to be substantial viscous changes. However, if a shorter period forcing elicits a lowered mantle viscosity, the timescale in which the viscous response can become important is much shorter. Although the elastic contribution (Fig. 7a) is still dominant, the viscous signal (Fig. 7b) is responsible for 20–40% of the projected RSL change caused by future ice-sheet mass loss (Fig. 7c). Excluding this viscous response would lead to a significant underprediction of RSL fall around Greenland. This highlights the importance of calculating the full viscoelastic response of the solid Earth in response to future surface loading when projecting RSL, and the need for a continued focus on how to most appropriately model the seemingly time-dependent nature of mantle relaxation.

The fall in RSL by up to 2.5 m for RCP 8.5 that we project to occur along Greenland’s coasts by the end of this century could slow down the pace of grounding-line retreat for Greenland’s marine-terminating glaciers, as the position of the grounding line depends on sea level at the grounding line60,61,62. Ice discharge from marine-terminating glaciers was responsible for approximately two-thirds of Greenland’s total contribution to global sea level over the period 1972–2018 CE63,64. The response of the solid Earth and gravity field to this ice-mass loss can raise the bed topography and decrease RSL at the grounding line, which can lead to its stabilization and potential re-advance61,62. This effect may be particularly impactful for large marine-terminating glaciers that rest on bedrock that deepens inland (like Kangerlussuaq and Sermeq Kujalleq65) and are vulnerable to marine ice sheet instability feedbacks, where the flux of ice across the grounding line increases as it retreats60,66,67,68,69,70. Adhikari et al.67 find that uplift of 1–4 m by 2100 CE is sufficient to noticeably influence ice dynamics and promote the stabilization of marine segments of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. This amount of uplift is of similar magnitude to that projected to occur along Greenland’s coasts over a similar time frame; however, a direct comparison between the dynamics of Greenland and Antarctica’s marine-terminating glaciers is difficult given differences in buttressing and other factors. This motivates the need for a detailed analysis that couples GIA and ice-sheet models on centennial timescales in Greenland.

Furthermore, a RSL fall of the magnitude projected in this study can impact the coastal communities of Greenland. RSL fall on the order of multiple meters has the potential to increase navigational hazards and limit the accessibility of harbors to deep draft boats by reducing the water depth beneath their keels. Marine channels that are already shallow today are vulnerable to becoming exposed at low tide, disconnecting navigational routes and water flow, which may impact marine habitats. Port infrastructure, such as docks and mooring sites, could become less useful as the falling sea level would make access to them more difficult or even impossible. A reliance on global sea-level projections can lead to the perspective that sea level will rise in Greenland due to climate change71, which would create a very different set of hazards than those presented above. The regional RSL projections provided in this study can be used by communities to assess their site-specific risks to sea-level fall and prepare adaptation strategies accordingly. Subsequent interdisciplinary studies that consider these projections with regard to the national economy, coastal structure, and marine ecology are needed to better understand and communicate the impact that RSL fall could have on these communities.

Methods

Present-day VLM and projected RSL change driven by deglacial mass change

Ice changes over the deglaciation (30ka-1ka) affect both present-day VLM and RSL projections. For predictions of both, we use output from a suite of 65 3D GIA model runs in which the Earth structure varies laterally and with depth (Supplementary Table 1). The majority of runs (60) are adopted from Pan et al.72. They vary in choice of two global ice histories, ICE-6G53 and ANU73, four seismic tomography models, which inform lateral variability in viscosity50,51,74,75, two models for variations in lithospheric thickness76,77, and two values for the scaling factor used to map between temperature perturbations in the mantle and viscosity (0.02/∘C and 0.04/∘C). The spherical average of each 3D viscosity profile is equivalent to the 1D Earth model generally paired with each ice history72. We note that for the ANU simulations, two different spherical average viscosity profiles were used to explore the non-uniqueness reported in Lambeck et al.73 (Supplementary Table 1).

We further adopt output from four 3D GIA model runs presented in Austermann et al.52 and one from Antwerpen et al.49. Austermann et al.52 inferred a model of Earth’s 3D viscosity structure from the Schaeffer & Lebedev50 seismic tomography model for the mantle above the transition zone (<400 km depth) and the French & Romanowicz51 model for the mantle below that. The Earth models explore differences in the average lithospheric thickness, average mantle viscosity, and scaling from temperature perturbation to viscosity perturbation to mimic dislocation creep. Earth structures are paired with the ice reconstruction from ICE-6G for 150 ka to present. Antwerpen et al.49 used the 3D viscosity perturbations from Austermann et al.52 paired with the Greenland-specific ice reconstruction Huy36. While Huy3 and the GrIS portion of ICE-6G were created using glaciological models that account for ice dynamics, ANU and the other global ice masses in ICE-6G and Huy3 (excluding the North American portion) were not. All 3D GIA calculations were performed with the GIA code SEAKON78, which is gravitationally self-consistent and solves for solid Earth deformation, geoid changes, and impacts to Earth’s rotational axis while accounting for the migration of shorelines3.

We use output from the suite of 65 GIA model runs described above to calculate the contribution of the deglaciation to present-day VLM and future RSL change. The rate of present-day VLM is taken as the rate of solid Earth deformation between 250 years before present (BP) and today. For future RSL change, we calculate the rate of RSL change between 250 years BP and today and assume that this is an appropriate estimate for the rate of change over this century. We extrapolate this rate to 2100 CE to obtain the deglacial contribution to future RSL. To account for the possibility that some model runs are more accurate representations of Earth’s internal structure and deglacial ice history than others, we weight the predictions from each model based on their fit to late-Holocene (7 ka to present) RSL observations around Greenland from the GAPSLIP database23. The dataset we use consists of both sea-level index points (n = 125), which give an estimate for the elevation of sea level at a point in the past, and limiting data points (n = 268), which can only tell us that sea level was above (marine-limiting) or below (terrestrial-limiting) a certain elevation. We use a weighted residual sum of squares (WRSS) calculation79,80 for each model run’s prediction to combine the uncertainties associated with the index and limiting data, according to:

where erf represents the error function, rnm is the residual between the modeled and observed RSL at the age and location of data point n and model m, εn is the uncertainty in the observed RSL, and qn refers to the type of datum (1 for terrestrial limiting, −1 for marine limiting, and 0 for index). For a more detailed explanation of the equation for WRSSnm, please refer to Creel et al.79 and references within. The weight for each model is then calculated as the normalized inverse of WRSSnm summed over all data points. We use these weights to calculate the weighted average and weighted standard deviation of present-day VLM rates (Fig. 1). We also sample the deglacial contribution to future RSL change according to the model weights in order to combine them with the other contributions to projected RSL change.

Present-day VLM driven by ice changes since the beginning of the LIA

Ice changes since the beginning of the LIA (1ka–0ka) affect both present-day VLM and RSL projections. In this section, we describe the GIA model setup that captures the time period from the LIA to present-day, which we use to calculate present-day VLM. We calculate this contribution first since we can compare it to observations to better constrain uncertainties in the ice and Earth parameters of the GIA model (Table 1). These constraints are then propagated into our projections of RSL driven by ice-sheet changes from the LIA to 2100 CE.

Present-day VLM caused by the Earth’s response to LIA ice and ocean loading is predicted using a gravitationally self-consistent formalism that solves for solid Earth deformation, geoid changes, and impacts to Earth’s rotational axis while accounting for the migration of shorelines3. This 1D GIA model requires an input (1D) Earth structure and ice thickness history from the LIA to the beginning of the GPS record. Note that deformation associated with ice change during the GPS record is calculated separately and described in the next section. Calculations are run at spherical harmonic degree 512 for 12 timesteps from 1000 to 2022 CE. We vary lithospheric thickness, mantle viscosity, LIA mass anomaly, and LIA termination time following the posterior probability solutions for these parameters from Adhikari et al.16.

Adhikari et al.16 combined estimates of mass balance for the GrIS17 and its peripheral glaciers18 to create a history of post-LIA ice thickness anomaly relative to the year 2017 CE. We sample the mass anomaly of the ice sheet during the LIA from a range centered around the posterior mean (14,860 ± 2670 Gt) calculated by Adhikari et al.16 (Table 1, n = 13). Its magnitude is assumed to be constant throughout the duration of the LIA. The Greenland-wide termination time of the LIA is varied within the range from 1800–1910 CE (Table 1, n = 9). Adhikari et al.16 find that changing the preceding Medieval Warm Period (~ 1000 CE) mass anomaly and the LIA inception time do not affect their results significantly, so these parameters are kept constant in our models at 3673 Gt and 1450 CE, respectively. Ice change that approximately spans the time frame of GNET observations is set to zero to not double-count for coeval elastic deformation described in the next section.

We use a 1D homogeneous Maxwell model overlain by an elastic lithosphere, for which we vary the thickness. Our mantle viscosity ranges from 4 × 1019 Pa s to 25 × 1019 Pa s (Table 1, n = 12) and our lithospheric thickness varies from 60 to 240 km (Table 1, n = 10), with a higher sampling density around the highest posterior likelihood of each parameter16. The elastic and density structure vary with depth according to the Preliminary Reference Earth Model[PREM; 81. We assume a laterally and radially homogeneous viscosity structure because the inferred mantle viscosity over centennial timescales varies minimally for the upper mantle below Greenland41, and it is unlikely that small-scale load changes, like those experienced in Greenland since the beginning of the LIA, invoke deformation within the lower mantle42. However, we also acknowledge that omitting 3D variations in Earth structure, especially those driven by lateral variations in lithospheric thickness, may have some impact on our results. Combining all parameters leads to 14,040 GIA simulations.

Observations of present-day VLM and their elastic corrections

To better constrain the parameters described in Table 1, we compare predictions of VLM to observations. Here we describe the observations that are being used and additional corrections that need to be applied.

Observations of VLM were obtained from a network of 57 permanent GNSS stations located around Greenland’s coast, termed GNET. We use rates of VLM determined by Berg et al.20 that were calculated over the period of available data for each station. The majority of GNET stations were established between 2007 and 2009 CE, though there are some that were installed in the mid-to-late 1990s, and their observational records run to 2022 CE. Positive uplift rates are observed at all 57 stations, with rates that range in magnitude from 1.3 to 17.5 mm yr−1. Following Adhikari et al.16, we remove two stations located in central East Greenland near the Kangerlussuaq glacier from our analysis. The mantle viscosity beneath these locations is likely lowered locally due to mantle flow associated with the Icelandic plume16,26,82,83, which we don’t allow for in our calculations here. Observed uplift rates at each station (VOBS) are assumed to be the sum of VLM contributions due to ice-mass changes during the deglaciation (VDEG), ice-mass changes since the beginning of the LIA (VLIA), ice-mass changes during the GPS record (VELA) and a reference frame correction (VRF; Supplementary Section 1):

For the contribution of elastic deformation to present-day uplift rates, VELA, we use elastic VLM rates modeled by Berg et al.20. They obtain rates of mass change that span the last two decades for the GrIS84,85, Greenland’s peripheral glaciers21, and Canada’s peripheral glaciers20. In response to these ice changes, the solid Earth beneath Greenland has been uplifting at rates that range from 1.5 mm yr−1 to 13.8 mm yr−1. The GrIS is generally the largest contributor to these signals, though the contribution from peripheral glaciers can be significant, especially in North and East Greenland, where their presence is greatest20. The elastic, deglacial, and reference-frame contributions to present-day VLM rates are incorporated into the framework of our Bayesian analysis (next section), so that we can directly compare predictions of LIA-driven VLM to observations.

Bayesian framework

We find posterior distributions for our input parameters of the LIA-GIA model, summarized in Table 1, by combining model predictions of VLM with observations using a Bayesian inversion. Our approach is similar to that used by Piecuch et al.86 and uses the paradigm from Berliner87, which constructs a model with three levels of equations. First, process-level equations represent how the quantity of interest—here, the present-day VLM rate arising from the LIA—evolves in space and time. Second, data-level equations describe how the available observations relate to the underlying process. Finally, parameter-level equations place prior constraints on the model’s parameters. For more details on hierarchical modeling, see Cressie & Wikle88. Our posterior distributions are updates to those found in Adhikari et al.16 since we used improved GNET data and estimated elastic contributions20, which cover the longest time frames available for each GNET station and account for the elastic rebound caused by peripheral glacier melt from Greenland and Canada, as well as through our use of a more comprehensive Bayesian analysis to compare this data to our modeled predictions.

Data level

We have data \({{{\bf{x}}}}={[{x}_{1},...,{x}_{N}]}^{T}\) at N = 55 locations, which are GNSS rates corrected for elastic and deglacial contributions. Thus, these data reflect present-day VLM due to the LIA plus a reference frame correction (hereinafter LIA’ VLM). We assume that the data x are noisy versions of the true LIA’ VLM rate \({{{\bf{v}}}}={[{v}_{1},...,{v}_{N}]}^{T}\) according to:

where ~ means “is distributed as", \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}(a,b)\) is the multivariate normal distribution with mean vector a and covariance matrix b, and Δ = diag(\({\delta }_{1}^{2},...,{\delta }_{N}^{2}\)) is the diagonal matrix of the data error variances where we define \({\delta }_{i}^{2}\) as the sum of error variance of the ith GNSS data and the models of the elastic and deglacial contributions.

Process Level

We assume that the true LIA’ VLM rates v arise from GIA, as well as a residual large-scale (regional) process and a residual small-scale (local) process, both unrelated to GIA. Formally, we write:

where ϵ2 is the unknown spatial variance of the local VLM process unrelated to GIA, \({\mathsf{I}}\) is the identity matrix, and u is the large-scale LIA’ VLM process, which we write as:

where \({\mathsf{G}}\) is the [K × N] matrix of K = 14,040 GIA model solutions at the N locations, \({{{\bf{c}}}}={[{c}_{1},...,{c}_{k}]}^{T}\) is an unknown [K × 1] selection vector that picks out one of the GIA model solutions, and α1 and Ω are, respectively, the unknown mean vector and covariance matrix of the regional VLM process unrelated to GIA, such that:

where ω2 is an unknown variance, ρ is an unknown inverse length scale, and ∣si − sj∣ is the distance between the ith and jth locations; this structure assumes that the covariance between two locations decreases with increasing distance. We model c as a multinomial random variable:

where \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{\pi }}}})\) is the multinomial distribution with probabilities \({{{\boldsymbol{\pi }}}}={[{\pi }_{1},\ldots,{\pi }_{K}]}^{T}\). A helpful analogy is to imagine c as a (potentially weighted) K-sided die and π as the probabilities of rolling the respective sides of the die.

Parameter level

To complete the model, we place priors on the unknown parameters. We choose weak, uninformative priors so that posterior solutions are controlled more by the available data than prior beliefs encoded into the algorithm. We use a normal prior for α:

where \(\widetilde{{\eta }_{\alpha }}\) is the prior mean and \(\widetilde{{\zeta }_{\alpha }^{2}}\) is the prior variance. Note that we use superscripted tildes to identify hyperparameters (that is, parameters on the prior distributions). We use inverse-gamma priors for ϵ2 and ω2:

where \(\widetilde{\xi }\) is the shape parameter and \(\widetilde{\chi }\) is the scale parameter of inverse-gamma distribution \({{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}^{-1}\). For ρ, we use a log-normal prior:

where \(\widetilde{{\eta }_{\rho }}\) is the “mean" and \(\widetilde{{\zeta }_{\rho }^{2}}\) is the “variance" of the distribution. Finally, we use a symmetric Dirichlet prior for π:

where \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}(\widetilde{\mu })\) is the Dirichlet distribution with concentration parameter \(\widetilde{\mu }={K}^{-1}\) and Γ is the gamma function. Note that this prior on π gives equal weight to all GIA model predictions. In keeping with our earlier analogy, this is like starting with a fair (unweighted) die, which has uniform probability of rolling any side. However, through the data assimilation, our posterior inference on π corresponds to an unfair (weighted) die, which favors GIA solutions that correspond better to the observations.

Posterior distribution

Given Bayes’ rule, we assume the posterior distribution is:

Here, we use the symbols p, ∣, and ∝ to indicate probability distribution, conditionality, and proportionality, respectively. We draw samples from the posterior solution using standard numerical methods89. For u, v, and most parameters, we draw samples using a Gibbs sampler, whereas for ρ, which has a nonstandard conditional posterior distribution, we use a Metropolis sampler. We perform 200,000 iterations with the sampler. We omit the first 100,000 iterations, which we regard as burn in, to eliminate startup transients and the effects of initial conditions. To reduce serial correlation, we thin the remaining iterations, only keeping one out of every 100 remaining samples. We analyze the remaining 1000 joint posterior samples. We also computed standard model diagnostics89 to validate the model and interrogate its solutions (Supplementary Section 3, Supplementary Figs. 6-9). The Bayesian model code was written and executed using the MATLAB numeric computing platform and takes ~20 min to run on a 2023 MacBook Pro (Apple M2 Pro Chip; 32 GB Memory). The final results of our Bayesian analysis are posterior distributions on the GIA model parameters shown in Table 1 in the form of the posterior vector c that is then used to inform our prediction of present-day VLM driven by the LIA (Fig. 3) and our projections of LIA-to-2100 CE RSL change (next section).

Projections of RSL change driven by LIA-to-2100 CE ice-sheet change

Projected mass changes from Greenland and Antarctica to 2100 CE are adopted from eight ice-sheet modeling groups working under the framework of the Ice Sheet Model Intercomparison Project for CMIP6[ISMIP6; 22,44. For each modeling group, we use projections based on future emissions scenarios RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5. The projections are converted to ice thickness anomaly relative to 2017 CE and concatenated to the Greenland LIA ice history used to calculate present-day VLM caused by the LIA. We ran a total of 224,640 (14,040 LIA ice histories/Earth structures × 8 ISMIP6 modeling groups × 2 RCP scenarios) 1D Maxwell GIA simulations, where we vary the mantle viscosity, lithospheric thickness, LIA mass anomaly, and LIA termination time over the ranges listed in Table 1. Each model is run at spherical harmonic degree 512 for a total of 26 timesteps from 1000 CE to 2100 CE, with timesteps from 2020–2100 CE increasing to 5-year intervals. A control simulation, in which the GIA model is forced by future ice-mass anomalies projected for a fixed modern climate, is subtracted from the projections of RSL to correct for model drift that arises from the initialization strategies of the individual ice-sheet modeling groups22. This was done for each combination of GIA model parameters (i.e. required an additional 112,320 GIA simulations). To obtain the median and likely range of future RSL change across our suite of GIA simulations, we use the insight gained from our Bayesian inversion and multiply our modeled RSL values at each timestep with the posterior vector c (see previous section). We then calculate the median and likely range across the resulting posterior distribution.

Contributions to projected RSL change excluding ice-sheet mass changes and associated GIA

In addition to RSL change caused by variations in ice-sheet mass and related GIA, other processes will contribute to the RSL change experienced by coastal Greenland over this century. These processes include changes in global glaciers, thermal expansion and ocean dynamics, and changes in terrestrial water storage, excluding glaciers and ice sheets1. We refer to the combination of these as the “other processes" contribution. Note that the contribution from future ice change in Antarctica is already included in the previous section. Estimates for the RSL contribution of each of these processes to 2100 CE for SSP1-2.6 (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 1 paired with an approximate radiative forcing of 2.6 W/m2 by 2100 CE) and SSP5-8.5 (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5 paired with an approximate radiative forcing of 8.5 W/m2 by 2100 CE) were obtained from the dataset of RSL projections associated with the IPCC AR6 that excludes the signal driven by long-term vertical land movement1,46,47,48. The projections of RSL provided by this dataset are given as percentiles of a probability distribution at 10-year timesteps from 2020 to 2100 CE relative to a 1995–2014 CE baseline. We linearly extrapolate these percentiles to 2017 CE and make predictions from 2020–2100 CE relative to 2017 CE (instead of 1995–2014 CE). For each process, we construct a probability distribution at each timestep based on the percentiles. We then draw 1000 samples for each process and each timestep and combine them to obtain a distribution for the other processes component. This allows us to calculate the median and likely range for this component (Fig. 4i–l). For our total estimate of RSL change around Greenland (Fig. 5), we combine the 1000 random draws from the other processes component with random draws from the posterior distribution of future RSL driven by LIA-2100 CE ice-sheet change and the contribution from deglacial ice change. For the latter we sample predictions according to the deglacial model weights. We then calculate the median and likely range of total projected RSL across these combined samples.

Data availability

The inputs and results from the Bayesian algorithm used to used to invert for Little Ice Age vertical land motion, predicted present-day vertical land motion driven by deglacial ice mass change, and RSL predictions to 2100 CE, both on a spatial grid of Greenland and at select locations, are deposited in a Zenodo repository under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1687839290.

Code availability

The code used to produce 1D GIA models is available at https://github.com/jaustermann/SLcode/. The code for the Bayesian algorithm used to invert for Little Ice Age vertical land motion is available on Zenodo under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1678031591 or on Github at https://github.com/christopherpiecuch/bayesLIA.

References

Fox-Kemper, B. et al. Ocean, cryosphere and sea level change. In Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, book section 9, 1211–1361 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter09.pdf (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Farrell, W. E. & Clark, J. A. On Postglacial Sea level. Geophys. J. Int. 46, 647–667 (1976).

Kendall, R. A., Mitrovica, J. X. & Milne, G. A. On post-glacial sea level–II. numerical formulation and comparative results on spherically symmetric models. Geophys. J. Int. 161, 679–706 (2005).

Whitehouse, P. L. Glacial isostatic adjustment modelling: historical perspectives, recent advances, and future directions. Earth Surf. Dyn. 6, 401–429 (2018).

Gregory, J. M. et al. Concepts and terminology for sea level: Mean, variability and change, both local and global. Surv. Geophys. 40, 1251–1289 (2019).

Lecavalier, B. S. et al. A model of Greenland ice sheet deglaciation constrained by observations of relative sea level and ice extent. Quat. Sci. Rev. 102, 54–84 (2014).

Bennike, O. & Björck, S. Chronology of the last recession of the Greenland ice sheet. J. Quat. Sci. 17, 211–219 (2002).

Funder, S. & Hansen, L. The Greenland ice sheet - a model for its culmination and decay during and after the last glacial maximum. Bull. Geol. Soc. Denmark https://doi.org/10.37570/bgsd-1995-42-12 (1996).

Simpson, M. J., Milne, G. A., Huybrechts, P. & Long, A. J. Calibrating a glaciological model of the Greenland ice sheet from the last glacial maximum to present-day using field observations of relative sea level and ice extent. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 1631–1657 (2009).

Kaufman, D. et al. Holocene thermal maximum in the western arctic (0-180∘w). Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 529–560 (2004).

Axford, Y., de Vernal, A. & Osterberg, E. C. Past warmth and its impacts during the Holocene Thermal Maximum in Greenland. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 49, 279–307 (2021).

Larsen, N. K. et al. The response of the southern Greenland ice sheet to the Holocene thermal maximum. Geology 43, 291–294 (2015).

Farnsworth, L. B. et al. Holocene history of the Greenland ice-sheet margin in northern nunatarssuaq, northwest Greenland. arktos 4, 1–27 (2018).

Weidick, A. & Bennike, O.Quaternary glaciation history and glaciology of Jakobshavn Isbrae and the Disko Bugt region, West Greenland : a review. Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland bulletin, 14 (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, 2007).

Kjaer, K. H. et al. Glacier response to the Little Ice Age during the neoglacial cooling in Greenland. Earth-Sci. Rev. 227, 103984 (2022).

Adhikari, S. et al. Decadal to centennial timescale mantle viscosity inferred from modern crustal uplift rates in Greenland. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094040 (2021).

Kjeldsen, K. K. et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet since AD 1900. Nature 528, 396–400 (2015).

Marzeion, B., Leclercq, P., Cogley, J. & Jarosch, A. Brief communication: Global reconstructions of glacier mass change during the 20th century are consistent. Cryosphere 9, 2399–2404 (2015).

IMBIE Team Mass balance of the Greenland ice sheet from 1992 to 2018. Nature 579, 233–239 (2020).

Berg, D. et al. Vertical land motion due to present-day ice loss from Greenland’s and Canada’s peripheral glaciers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL104851 (2024).

Khan, S. A. et al. Accelerating ice loss from peripheral glaciers in north Greenland. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098915 (2022).

Goelzer, H. et al. The future sea-level contribution of the Greenland ice sheet: a multi-model ensemble study of ISMIP6. Cryosphere 14, 3071–3096 (2020).

Gowan, E. J. Paleo sea-level indicators and proxies from Greenland in the gapslip database and comparison with modelled sea level from the paleomist ice-sheet reconstruction. GEUS Bulletin https://doi.org/10.34194/geusb.v53.8355 (2023).

Tarasov, L. & Richard Peltier, W. Greenland glacial history and local geodynamic consequences. Geophys. J. Int. 150, 198–229 (2002).

Fleming, K. & Lambeck, K. Constraints on the Greenland ice sheet since the last glacial maximum from sea-level observations and glacial rebound models. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 1053–1077 (2004).

Khan, S. A. et al. Geodetic measurements reveal similarities between post–last glacial maximum and present-day mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600931 (2016).

Simpson, M. J., Wake, L., Milne, G. A. & Huybrechts, P. The influence of decadal-to millennial-scale ice mass changes on present-day vertical land motion in Greenland: Implications for the interpretation of GPS observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JB007776 (2011).

Nakada, M., Okuno, J., Lambeck, K. & Purcell, A. Viscosity structure of Earth’s mantle inferred from rotational variations due to gia process and recent melting events. Geophys. J. Int. 202, 976–992 (2015).

Darbyshire, F. A., Dahl-Jensen, T., Larsen, T. B., Voss, P. H. & Joyal, G. Crust and uppermost-mantle structure of Greenland and the northwest Atlantic from Rayleigh wave group velocity tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 212, 1546–1569 (2018).

Milne, G. A. et al. The influence of lateral earth structure on glacial isostatic adjustment in Greenland. Geophys. J. Int. 214, 1252–1266 (2018).

Wake, L. M., Lecavalier, B. S. & Bevis, M. Glacial isostatic adjustment (gia) in Greenland: a review. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2, 101–111 (2016).

van Dam, T. et al. Using GPS and absolute gravity observations to separate the effects of present-day and Pleistocene ice-mass changes in South East Greenland. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 459, 127–135 (2017).

Bevis, M. et al. Bedrock displacements in Greenland manifest ice mass variations, climate cycles and climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 11944–11948 (2012).

Faul, U. & Jackson, I. Transient creep and strain energy dissipation: an experimental perspective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 43, 541–569 (2015).

Takei, Y. Effects of partial melting on seismic velocity and attenuation: a new insight from experiments. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 45, 447–470 (2017).

Lau, H. C. Transient rheology in sea level change: implications for meltwater pulse 1a. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 609, 118106 (2023).

Caron, L., Métivier, L., Greff-Lefftz, M., Fleitout, L. & Rouby, H. Inverting glacial isostatic adjustment signal using a Bayesian framework and two linearly relaxing rheologies. Geophys. J. Int. 209, 1126–1147 (2017).

Coonin, A. N., Lau, H. C. & Coulson, S. Meltwater pulse 1a sea-level-rise patterns explained by global cascade of ice loss. Nat. Geosci. 18, 254–259 (2025).

Ivins, E., Caron, L., Adhikari, S., Larour, E. & Scheinert, M. A linear viscoelasticity for decadal to centennial time scale mantle deformation. Rep. Prog. Phys. 83, 106801 (2020).

Simon, K. M., Riva, R. E. & Broerse, T. Identifying geographical patterns of transient deformation in the geological sea level record. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 127, e2021JB023693 (2022).

Paxman, G. J., Lau, H. C., Austermann, J., Holtzman, B. K. & Havlin, C. Inference of the timescale-dependent apparent viscosity structure in the upper mantle beneath greenland. AGU Adv. 4, e2022AV000751 (2023).

Pan, L., Mitrovica, J. X., Milne, G. A., Hoggard, M. J. & Woodroffe, S. A. Timescales of glacial isostatic adjustment in Greenland: is transient rheology required? Geophys. J. Int. 237, 989–995 (2024).

Ajourlou, P., Darbyshire, F., Audet, P. & Milne, G. A. Structure of the crust and upper mantle in Greenland and northeastern Canada: insights from anisotropic rayleigh-wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 239, 329–350 (2024).

Seroussi, H. et al. Ismip6 Antarctica: a multi-model ensemble of the Antarctic ice sheet evolution over the 21st century. Cryosphere Discuss. 14, 1–54 (2020).

Van Vuuren, D. P. et al. The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Clim. change 109, 5–31 (2011).

Kopp, R. E. et al. The framework for assessing changes to sea-level (facts) v1. 0: a platform for characterizing parametric and structural uncertainty in future global, relative, and extreme sea-level change. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 7461–7489 (2023).

Garner, G. G. et al. IPCC AR6 sea level projections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6382554 (2021).

Kopp, R. E. IPCC AR6 relative sea level projections without background component. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5967269 (2021).

Antwerpen, R. et al. Holocene southwest Greenland ice sheet behavior constrained by sea-level modeling. Quat. Sci. Rev. 328, 108553 (2024).

Schaeffer, A. & Lebedev, S. Global shear speed structure of the upper mantle and transition zone. Geophys. J. Int. 194, 417–449 (2013).

French, S. & Romanowicz, B. A. Whole-mantle radially anisotropic shear velocity structure from spectral-element waveform tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 199, 1303–1327 (2014).

Austermann, J., Hoggard, M. J., Latychev, K., Richards, F. D. & Mitrovica, J. X. The effect of lateral variations in earth structure on last interglacial sea level. Geophys. J. Int. 227, 1938–1960 (2021).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. & Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: the global ice-6g_c (vm5a) model. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 120, 450–487 (2015).

Slangen, A. B. et al. Projecting twenty-first century regional sea-level changes. Clim. Change 124, 317–332 (2014).

Garner, A. J. et al. Evolution of 21st century sea level rise projections. Earth’s. Future 6, 1603–1615 (2018).

Horton, B. P. et al. Mapping sea-level change in time, space, and probability. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 481–521 (2018).

Kopp, R. E. et al. Probabilistic 21st and 22nd century sea-level projections at a global network of tide-gauge sites. Earth’s. future 2, 383–406 (2014).

Payne, A. J. et al. Future sea level change under coupled model intercomparison project phase 5 and phase 6 scenarios from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091741 (2021).

Spada, G., Bamber, J. & Hurkmans, R. The gravitationally consistent sea-level fingerprint of future terrestrial ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 482–486 (2013).

Weertman, J. Stability of the junction of an ice sheet and an ice shelf. J. Glaciol. 13, 3–11 (1974).

Gomez, N., Mitrovica, J. X., Huybers, P. & Clark, P. U. Sea level as a stabilizing factor for marine-ice-sheet grounding lines. Nat. Geosci. 3, 850–853 (2010).

Larour, E. et al. Slowdown in Antarctic mass loss from solid earth and sea-level feedbacks. Science 364, eaav7908 (2019).

Mouginot, J. et al. Forty-six years of greenland ice sheet mass balance from 1972 to 2018. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 9239–9244 (2019).

Slater, D. A. et al. Estimating Greenland tidewater glacier retreat driven by submarine melting. Cryosphere 13, 2489–2509 (2019).

Khan, S. A. et al. Greenland ice sheet mass balance: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 046801 (2015).

Schoof, C. Ice sheet grounding line dynamics: steady states, stability, and hysteresis. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surface https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JF000664 (2007).

Adhikari, S. et al. Future Antarctic bed topography and its implications for ice sheet dynamics. Solid Earth 5, 569–584 (2014).

Gomez, N., Pollard, D. & Holland, D. Sea-level feedback lowers projections of future antarctic ice-sheet mass loss. Nat. Commun. 6, 8798 (2015).

Konrad, H., Sasgen, I., Pollard, D. & Klemann, V. Potential of the solid-earth response for limiting long-term west antarctic ice sheet retreat in a warming climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 432, 254–264 (2015).

Barletta, V. R. et al. Observed rapid bedrock uplift in the Amundsen Sea embayment promotes ice-sheet stability. Science 360, 1335–1339 (2018).

Minor, K. et al. Greenlandic perspectives on climate change 2018–2019: Results from a national survey. Greenlandic Perspectives on Climate Change 2019, (2018).

Pan, L. et al. The influence of lateral earth structure on inferences of global ice volume during the last glacial maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 290, 107644 (2022).

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y. & Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15296–15303 (2014).

Ritsema, J., Deuss, A., Van Heijst, H. & Woodhouse, J. S40rts: a degree-40 shear-velocity model for the mantle from new rayleigh wave dispersion, teleseismic traveltime and normal-mode splitting function measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 184, 1223–1236 (2011).

Auer, L., Boschi, L., Becker, T., Nissen-Meyer, T. & Giardini, D. Savani: A variable resolution whole-mantle model of anisotropic shear velocity variations based on multiple data sets. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 119, 3006–3034 (2014).

Afonso, J. C., Salajegheh, F., Szwillus, W., Ebbing, J. & Gaina, C. A global reference model of the lithosphere and upper mantle from joint inversion and analysis of multiple data sets. Geophys. J. Int. 217, 1602–1628 (2019).

Yousefi, M., Milne, G. A. & Latychev, K. Glacial isostatic adjustment of the Pacific coast of North America: the influence of lateral earth structure. Geophys. J. Int. 226, 91–113 (2021).

Latychev, K. et al. Glacial isostatic adjustment on 3-D Earth models: a finite-volume formulation. Geophys. J. Int. 161, 421–444 (2005).

Creel, R. C. et al. Postglacial relative sea level change in Norway. Quat. Sci. Rev. 282, 107422 (2022).

Auriac, A. et al. Glacial isostatic adjustment associated with the Barents Sea ice sheet: a modelling inter-comparison. Quat. Sci. Rev. 147, 122–135 (2016).

Dziewonski, A. M. & Anderson, D. L. Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 25, 297–356 (1981).

Rogozhina, I. et al. Melting at the base of the Greenland ice sheet is explained by Iceland hotspot history. Nat. Geosci. 9, 366–369 (2016).

Weerdesteijn, M. F. & Conrad, C. P. Recent ice melt above a mantle plume track is accelerating the uplift of southeast Greenland. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 791 (2024).

Khan, S. A. et al. Greenland mass trends from airborne and satellite altimetry during 2011–2020. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surf. 127, e2021JF006505 (2022).

Smith, B. et al. Pervasive ice sheet mass loss reflects competing ocean and atmosphere processes. Science 368, 1239–1242 (2020).

Piecuch, C. G. et al. Origin of spatial variation in US East Coast sea-level trends during 1900–2017. Nature 564, 400–404 (2018).

Berliner, L. M. Hierarchical bayesian time series models. In Maximum entropy and Bayesian methods: Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, 1995 Proceedings of the fifteenth international workshop on maximum entropy and bayesian methods, 15–22 (Springer, 1996).

Cressie, N. & Wikle, C. K.Statistics for spatio-temporal data (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Gelman, A. et al. Bayesian Data Analysis. (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2013).

Lewright, L. Model output for Lewright et al. (2025): Projections of 21st-century sea-level fall along coastal Greenland [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16878392 (2025).

Piecuch, C. christopherpiecuch/bayeslia: Projections of 21st-century sea-level fall along coastal Greenland. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16780315 (2025).

Acknowledgments

LL, JA, and GJGP were supported by the National Science Foundation grant ICER 19-28146 and LL and JA were further supported by EAR 22-18664. The authors thank Karl Zinglersen and Aqqaluk Sørensen of the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources for their collaboration on this grant. JA acknowledges support from the Vetlesen Foundation. CGP was supported by the NASA Sea Level Change Team (grants 80NSSC20K1241, 80NSSC24K1546), National Science Foundation (award OCE-2002485), The GC McConnell Fellowship Fund and The George E. Thibault Early Career Scientist Fund at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Part of the research was conducted at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and funding support from the NASA Sea-level Change Team, Earth Surface and Interior Focus Area and Cryosphere Sciences Program. The authors acknowledge computing resources from Columbia University's Shared Research Computing Facility, and PALSEA, a working group of the International Union for Quaternary Sciences (INQUA) and Past Global Changes (PAGES), which is supported by the Swiss Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. We thank the projection authors for developing and making the sea-level rise projections available, multiple funding agencies for supporting the development of the projections, and the NASA Sea-Level Change Team for developing and hosting the IPCC AR6 Sea-Level Projection Tool.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. and L.L. designed the project. L.L. conducted the modeling and analysis with guidance from J.A. and C.G.P. J.A. wrote the 1D GIA code. C.G.P. created the Bayesian algorithm used to invert for LIA vertical land motion and guided LL in its use. CGP ran model diagnostics and validation for the Bayesian algorithm. S.A. provided guidance on the observed and elastic vertical land motion rates and on the LIA contribution to projected relative sea level. G.A.M. provided the 3D GIA model output. J.L.D. provided guidance on the reference-frame contribution to vertical land motion. G.J.G.P. provided the ice-sheet projections and guidance on modeling the LIA contribution to relative sea level. L.L. created figures and the original draft of the manuscript with help from J.A. All authors contributed to manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications Materials thanks Andra Garner and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lewright, L., Austermann, J., Piecuch, C.G. et al. Projections of 21st-century sea-level fall along coastal Greenland. Nat Commun 17, 353 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68182-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68182-6