Abstract

The wheat resistance gene Pm4 encodes a kinase fusion protein and has gained particular attention as it confers race-specific resistance against two major wheat pathogens: powdery mildew and blast. Here we describe the identification of AvrPm4, the mildew avirulence effector recognized by Pm4, using UV mutagenesis, and its functional validation in wheat protoplasts. We show that AvrPm4 directly interacts with and is phosphorylated by Pm4. Using genetic association and quantitative trait locus mapping, we further demonstrate that the evasion of Pm4 resistance by virulent mildew isolates relies on a second fungal component, SvrPm4, which suppresses AvrPm4-induced cell death. Surprisingly, SvrPm4 was previously described as AvrPm1a. We show that SvrPm4, but not its inactive variant svrPm4, is recognized by the nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat immune receptor Pm1a. These multiple roles of a single effector provide a new perspective on fungal (a)virulence proteins and their combinatorial interactions with different types of immune receptors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Wheat yields are severely impacted by pests and pathogens, accounting for over 20% of global losses1. Resistance breeding is a key strategy for crop protection and reduction of pathogen-inflicted damage. It often relies on dominant resistance (R) genes encoding immune receptors that recognize pathogen-delivered avirulence (Avr) effectors and activate immune responses, usually culminating in cell death2,3. While most cloned R genes in wheat encode nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) receptors, kinase fusion proteins (KFPs) are emerging as a distinct class of immune receptors specifically found in cereals4. Much of our current understanding of KFPs comes from tandem kinase proteins—a major KFP subclass—which consist of two kinase domains, sometimes with additional domains of unknown function5,6. Recent studies have demonstrated that some tandem kinase proteins rely on a helper NLR to trigger effector-induced cell death, as shown for Sr62 in Aegilops tauschii and RWT4 in wheat7,8.

Beyond tandem kinase proteins, other KFPs, composed of at least one kinase domain and additional domains, have been described in cereals but remain poorly understood9,10. Among them, Pm4, a protein containing a serine/threonine kinase, multiple C2 domains and transmembrane regions, is particularly notable: the Pm4 gene, located on wheat chromosome 2A, encodes two alternative isoforms derived by alternative splicing, Pm4-V1 and Pm4-V2, both required for resistance to the biotrophic pathogen Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici11. Pm4 occurs as several alleles (Pm4a–g), which encode highly similar proteins. Pm4a and Pm4b have been studied extensively in near-isogenic backgrounds, where they show partially overlapping race-specific resistance spectra against B. g. tritici11. Furthermore, recent work has shown that Pm4 also confers resistance to the hemibiotrophic wheat blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae12,13. In fact, the wheat blast resistance gene Rmg7 is identical to Pm4a, whereas the Rmg8 resistance gene on wheat chromosome 2B could be assigned to a Pm4 homoeologue with an identical sequence to that of Pm4f12. The corresponding wheat blast effector AVR-Rmg8 was cloned earlier14 and is recognized by multiple Pm4 alleles, including Pm4a, Pm4b and Pm4f12,13. The KFP encoded by Pm4 therefore represents a highly important resistance source in wheat with multiple alleles providing resistance to the obligate biotrophic B. g. tritici and the hemibiotrophic wheat blast pathogen simultaneously.

Despite the progress made in describing novel KFPs, a mechanistic understanding of how such proteins induce immunity is yet to be established. Kinase activity in KFPs was suggested to be relevant for Avr effector recognition and/or downstream signalling, a fact further supported by the finding of loss-of-function mutants affected in the kinase domain of KFPs such as Pm4 (ref. 11). Moreover, the tandem kinase protein RWT4, encoded by an allele of the powdery mildew resistance gene Pm24 (refs. 15,16), phosphorylates the avirulence but not the virulence variant of the wheat blast effector PWT4, suggesting that the phosphorylation of the Avr effector plays a key role in the resistance mechanism17. For the barley stem rust resistance protein RPG1, two fungal proteins work synergistically to induce phosphorylation and trigger a hypersensitive response (HR)18. These examples also highlight the importance of direct interaction between KFPs and their recognized effectors. Understanding these mechanisms will require the identification and characterization of Avr effectors that interact with KFPs such as Pm4.

Methods based on genetic association, such as biparental mapping or genome-wide association studies (GWAS), have been widely used to identify Avr loci in Blumeria and have been combined with cell death assays in heterologous systems such as Nicotiana benthamiana and host protoplasts19,20,21. More recently, AvrXpose, an approach based on UV mutagenesis and selection of gain-of-virulence mutants, has also proved effective in identifying genes controlling avirulence in B. g. tritici22. To date, all known Avr genes in B. g. tritici encode small (100–150 amino acid residues), secreted effector proteins with a predicted RNase-like structure and trigger a cell death response upon recognition by corresponding wheat NLR immune receptors (reviewed in ref. 23). In contrast, no B. g. tritici Avr effector recognized by a KFP has been identified so far.

Suppressors of R-gene-mediated immunity have been reported across bacterial, oomycete and fungal pathogens24. Notable examples from phytopathogenic fungi include the I locus in Melampsora lini, suppressing L7- and Lx-mediated resistance in flax25; AvrLm4-7 in Leptosphaeria maculans, suppressing Rlm3- and Rlm9-mediated resistance in oilseed rape26; and the SvrPm3 effector in B. g. tritici, with the ability to suppress resistance mediated by the wheat NLR Pm3 (refs. 19,27). Most suppressors identified so far suppress NLR-mediated immunity via diverse molecular mechanisms including interference with Avr recognition, NLR signalling or NLR homeostasis24. In contrast, little is known about the existence or mode of action of suppressor proteins affecting non-NLR resistance proteins such as KFPs.

In this study, we describe the identification of AvrPm4 from B. g. tritici using UV mutagenesis and show that the encoded protein is recognized by the wheat Pm4 resistance protein, resulting in cell death. AvrPm4 is a non-canonical Avr effector that directly interacts with Pm4. Furthermore, using genetic association and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping, we describe the identification of SvrPm4, a suppressor of AvrPm4-induced cell death, and show that SvrPm4 is the main factor allowing B. g. tritici to evade Pm4 resistance. We also show that SvrPm4, but not its inactive variant svrPm4, is recognized by the NLR Pm1a. Together, these findings represent a substantial step forward in understanding the resistance mechanisms of Pm4 and open new avenues for studying multi-pathogen resistance provided by KFPs in cereals.

Results

Powdery mildew mutants that simultaneously gain virulence on Pm4a and Pm4b exhibit mutations in a novel type of effector gene

To identify the B. g. tritici effector recognized by Pm4, we used the UV-mutagenesis-based approach AvrXpose22 and mutagenized the reference B. g. tritici isolate CHE_96224, avirulent on near-isogenic wheat lines containing Pm4a or Pm4b. Six mutants with gain of virulence on both Pm4 alleles were identified (hereafter, AvrPm4 mutants). By phenotyping the AvrPm4 mutants on a set of resistant wheat tester lines, we observed that their gain of virulence was specific to Pm4 and did not affect avirulence on other Pm genes (Extended Data Fig. 1). Whole-genome sequencing revealed that all six AvrPm4 mutants had mutations in the coding sequence of the effector gene Bgt-55142 (Fig. 1a). This was the only commonly mutated gene among all six AvrPm4 mutants (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), suggesting that Bgt-55142 is AvrPm4. We therefore focused on Bgt-55142 for further analyses.

a, Bgt-55142 protein structure, indicating the signal peptide (SP), predicted domains (described in detail in Extended Data Fig. 2d) and an NLS predicted by NLStradamus. The phenotypes and genotypes of the B. g. tritici gain-of-virulence mutants on Pm4a and Pm4b are shown above. STOP codons are represented by asterisks, *. b, Cartoon and surface representation of the AlphaFold3 structural prediction of Bgt-55142, with domains shown in different colours and labelled accordingly. Glutamate at position 360, altered in mutant 4AB-6 to a lysine, is represented by spheres and indicated in brown. The predicted aligned error is depicted in Extended Data Fig. 2b. c, Sequence alignment of the MEA domain of Bgt-55142 (amino acids 175 to 329) and AVR-Rmg8 reveals a region of high identity. The protein variant of the wheat blast isolate Br48 has been used for the alignment. In particular, the RGPGGPPP motif is 100% conserved and overlaps with the NLS (in yellow; Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Intriguingly, five AvrPm4 mutants had nonsense mutations in Bgt-55142 leading to a truncated protein or frameshifts, while only one (4AB-6) had a missense mutation leading to an amino acid change (E360K; Fig. 1a,b). Bgt-55142 is highly expressed at the haustorial stage28,29 and encodes a protein with a signal peptide and an amino-terminal domain with a predicted RNase-like structure, including the characteristic YxC motif and the conserved intron position found in all previously identified B. g. tritici Avr proteins (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2a)28,29,30. However, it differs from typical powdery mildew Avrs in length and structure, being considerably larger (372 amino acid residues) and containing a carboxy-terminal domain, which is predicted with low confidence by AlphaFold3, probably due to its repetitive and glycine- and proline-rich nature (Fig. 1a–c and Extended Data Fig. 2b,c). On the basis of a conserved domain search via the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), this domain shows sequence similarity to a MED15 domain, an EBNA-3B domain and a 104-kDa microneme/rhoptry antigen domain (Extended Data Fig. 2d), the first two being previously implicated in transcriptional regulation (see also ‘Discussion’)31,32. Given that the regions of sequence similarity with these three domains overlap, we defined the C-terminus of Bgt-55142 as a unique domain, which we renamed MEA (each bold letter representing one of the three identified hits: MED15, EBNA-3B and 104-kDa microneme/rhoptry antigen; Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2d). The MEA domain contains five repeated sequences (three complete, with 17 amino acids, and two incomplete, with 10 amino acids) as well as a predicted nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d). Furthermore, the software DP-bind indicates a high probability of binding DNA, particularly in the MEA domain of Bgt-55142 (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

The identity of the wheat blast effector AVR-Rmg8, recognized by Pm4 (Rmg8/Rmg7), is known12,13,14. We aligned its protein sequence with Bgt-55142 and found a region with high amino acid identity, corresponding to part of the MEA domain of Bgt-55142, which also contains the predicted NLS. Notably, an eight-amino-acid glycine- and proline-rich motif (RGPGGPPP) is identical between the two effectors (Fig. 1c).

Bgt-55142 96224 expression induces cell death in wheat protoplasts

To validate Bgt-55142 as AvrPm4, we performed a cell death assay in wheat protoplasts, similar to the one performed for AVR-Rmg8 (ref. 12). Gene sequences of the avirulence form and two mutated forms of Bgt-55142 (Bgt-5514296224, Bgt-551424AB-6 and Bgt-551424AB-2), along with those of known control Avrs (AVR-Rmg8, AvrPm3a2/f2 and AvrSr50), were codon-optimized for expression in planta and cloned into expression vectors without signal peptides. The constructs were cotransfected with a YFP reporter into protoplasts of the transgenic Bobwhite S26 wheat line stably expressing Pm4b-V1 and Pmb4b-V2, previously described11. A non-transgenic sister line lacking Pm4b served as a negative control. We observed a strong reduction in relative YFP fluorescence in the Pm4b-overexpressing line upon co-expression with AVR-Rmg8 and Bgt-5514296224, but not in the sister line (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast, neither of the two Bgt-55142 mutant alleles, Bgt-551424AB-6 and Bgt-551424AB-2, showed a reduction in relative YFP fluorescence; nor did the negative controls Avr-Pm3a2/f2 and Avr-Sr50 (Fig. 2a,b). This indicates that Bgt-5514296224, from now on referred to as AvrPm496224, is recognized in a Pm4b-dependent manner and subsequently triggers cell death. We then transfected Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2 in protoplasts of the wheat line Bobwhite S26 (lacking Pm4), alone and in combination with each other. Pm4b-V2 reduced fluorescence intensity by itself and in combination with Pm4b-V1, suggesting that it is partially autoactive (Fig. 2c). When transfecting both Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2 in combination with AvrPm496224, we observed a significant reduction in fluorescence intensity compared with avrPm44AB-2 (Fig. 2c), further confirming Pm4b-mediated cell death induction by AvrPm496224 in wheat. Co-expression of AvrPm496224 with Pm4 in N. benthamiana did not lead to cell death, indicating that one or more additional genetic components, present in wheat but not in N. benthamiana, are needed for triggering Pm4-mediated immunity (Extended Data Fig. 3).

a,b, Protoplasts generated from a transgenic line overexpressing Pm4b (a) and its Pm4b-free sister line (b) were transfected with different Avr effectors. AVR-Rmg8 was used as a positive control, while AvrPm3a2/f2 and AvrSr50 served as negative controls. In the presence of Pm4b, AvrPm496224 induced cell death in wheat protoplasts, in contrast to the mutant and truncated versions Bgt-551424AB-2 and Bgt-551424AB-6. c, Transfection of Pm4b-V1, Pm4b-V2 and AvrPm496224, but not Bgt-551424AB-2 (avrPm44AB-2), induced cell death in protoplasts of the wheat cultivar Bobwhite S26. Pm4b-V2 shows autoactivity, leading to increased cell death in all tests containing Pm4b-V2. For all three panels, each treatment was assessed with two technical and three biological replicates, and the experiments were repeated three times (total n = 9 biological replicates per experiment). The height of the bars shows the mean value for all the replicates, and the whiskers show the standard deviation. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined using a two-sided analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Bars with the same letter are not significantly different.

Pm4 directly interacts with AvrPm4, resulting in its localization to the endoplasmic reticulum network

Multiple tandem kinases interact with their corresponding Avr effectors as part of their resistance function7,8,17. We therefore investigated whether Pm4 binds AvrPm4 in a split-luciferase assay in N. benthamiana. We found that both AvrPm496224 and the truncated avrPm44AB-2 interacted with both Pm4b isoforms, Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2 (Fig. 3a,b). In contrast, we did not observe an interaction between Pm4 and the unrelated effector BgtE-5764 or between AvrPm496224 and WTK4, another KFP, confirming the specificity of the AvrPm4–Pm4 interaction (Fig. 3a,b). We consistently observed a stronger interaction signal between AvrPm4 and Pm4b-V1 than between AvrPm4 and Pm4b-V2, possibly reflecting differential protein accumulation between the isoforms (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The fact that the virulence variant avrPm44AB-2 also interacts with Pm4 suggests that the interaction alone is not sufficient to trigger an immune response.

a,b, Split-luciferase assay showing the interaction of NLUC-tagged Pm4b-V1 (a) and NLUC-tagged Pm4b-V2 (b) with CLUC-tagged AvrPm496224 and CLUC-tagged avrPm44AB-2 in N. benthamiana. Co-expression of the two Pm4b isoforms with BgtE-5764 and of AvrPm496224 with WTK4 served as negative controls. AvrPm496224 interacts with both Pm4b isoforms. Each treatment was assessed with two technical and six biological replicates, and the experiments were repeated three times (total n = 18 biological replicates). In each box plot, the median is shown as a central line in a box that spans from the 25th to the 75th percentile. The inner whiskers show the 95% confidence interval of the median, and the outer whiskers show the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Significance and P values (significance threshold of P < 0.05) were calculated with a two-sided ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons of means (contrast analyses) with Bonferroni correction (***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; NS, not significant). c,d, Subcellular colocalization in N. benthamiana of mTurquoise–AvrPm496224 (cyan), Pm4b-V1 (magenta) and Pm4b-V2 (yellow). When co-expressed with Pm4b-V1, AvrPm496224 colocalizes to the cytoplasm (c; scale bars, 10 μm), while co-expression with Pm4b-V2 redirects AvrPm4 to the ER (d; scale bars, 5 μm). The experiment was repeated twice. e, In vitro kinase assay showing autophosphorylation and transphosphorylation activity of purified Pm4 variants in the presence of [ɣ-32P]ATP. All constructs shown have an MBP tag. All reactions were supplemented with the common substrate MyBP (21 kDa, indicated by triangles). Constructs included Pm4b-V1, Pm4b-V2ΔTMD and their kinase-dead mutants (D170N and D188N), as well as a truncated construct containing only the kinase domain (Pm4b-Exon1–5; calculated protein size, 77.5 kDa). His-MBP alone served as a negative control. Wild-type Pm4b-V1 (calculated protein size, 106 kDa) and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD (calculated protein size, 107 kDa) were found to migrate at a size of around 120 kDa (see f and Extended Data Fig. 5a for better resolution). Wild-type Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD showed kinase activity (indicated by a single asterisk). Truncated proteins migrating at around 90 kDa (indicated by a double asterisk) were also detected. The substitutions D170N and D188N reduced or abolished kinase activity, respectively. Coomassie-stained proteins on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes served as loading controls. CBB, Coomassie brilliant blue. f, In vitro phosphorylation assay of AvrPm496224 and avrPm44AB-2 by Pm4. All constructs shown have an MBP tag. Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD were incubated with AvrPm496224 and avrPm44AB-2 in the presence of [ɣ-32P]ATP. AvrPm496224 (110 kDa, with truncated products ranging between 70 kDa and 100 kDa (Extended Data Fig. 5b), indicated by two single squares) and avrPm44AB-2 (indicated by a circle) were phosphorylated by both Pm4b isoforms. As a control, the same AvrPm4 constructs were incubated with kinase-dead Pm4b-V1(D188N). The kinase assays were repeated twice.

As previously reported, Pm4b-V1 predominantly localizes to the cytoplasm in the absence of Pm4b-V2, whereas Pm4b-V2 or Pm4b-V1–Pm4b-V2 complexes localize to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)11. To explore whether AvrPm4 and Pm4b share similar localization patterns indicative of a functional interaction, we assessed their subcellular localization in N. benthamiana. We co-expressed mTurquoise–AvrPm496224 with either mCherry–Pm4b-V1 or Venus–Pm4b-V2 and examined their subcellular localization via confocal microscopy. Intensity plot analyses revealed that mTurquoise–AvrPm496224 colocalizes with mCherry–Pm4b-V1 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 4b), whereas co-expression with Venus–Pm4b-V2 relocalizes AvrPm496224 to the ER network (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 4b). These findings provide additional evidence supporting the interaction between the two Pm4b isoforms and AvrPm496224.

Pm4 exhibits kinase activity and phosphorylates AvrPm4

Earlier work has shown that both Pm4 isoforms share a kinase domain that exhibits sequence characteristics of an active kinase. Furthermore, multiple loss-of-function mutants affecting this domain confirmed its essential role in resistance11. We therefore tested whether Pm4 exhibits kinase activity and whether AvrPm4 is a substrate for phosphorylation by Pm4.

We established an in vitro assay by expressing full-length Pm4b-V1 (kinase domain + C2C domain) and a truncated, soluble version of Pm4b-V2 (Pm4b-V2ΔTMD, kinase domain + C2D domain, lacking the transmembrane and PRT-C domains) with a maltose binding protein (MBP) tag in Escherichia coli. Both isoforms were purified using amylose resin, and protein integrity was assessed via Coomassie staining and immunoblotting (Fig. 3e,f and Extended Data Figs. 4c and 5). Pm4b-V1 (calculated protein size, 106 kDa) and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD (calculated protein size, 107 kDa) purification showed stronger protein accumulation at around 120 kDa and some smaller products, potentially truncated Pm4 proteins (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 4c).

Both Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD exhibited in vitro kinase activity and autophosphorylation (Fig. 3e, asterisks). Two bands were visible on the autoradiographs, corresponding to the previously mentioned larger band at around 120 kDa and a smaller band at around 90 kDa (Fig. 3e,f and Extended Data Fig. 5, asterisks). This indicates that either the smaller form is catalytically active, or a phosphorylation target of the larger protein is present in the extract. Importantly, both Pm4b isoforms also exhibited transphosphorylation activity, phosphorylating myelin basic protein (MyBP) as an exogenous substrate (Fig. 3e, triangle). A truncated construct containing only the kinase domain (exons 1–5, lacking a C2 domain) did not exhibit kinase activity, suggesting that the C2C domain in Pm4b-V1 and the C2D domain in Pm4b-V2 are required for kinase activity (Fig. 3e).

We previously identified two EMS mutants compromised in Pm4 resistance to powdery mildew, each carrying a non-synonymous mutation in the sequence encoding a conserved motif of the kinase domain: a D170N substitution in the HLDLKPAN motif of the catalytic loop and a D188N substitution in the activation loop11. To assess the functional impact of these substitutions, we introduced each substitution into both Pm4b isoforms and tested auto- and transphosphorylation activity using MyBP as a substrate. Auto- and transphosphorylation were strongly reduced by D170N and completely abolished by the D188N substitution (Fig. 3e), demonstrating a correlation between Pm4 kinase activity and resistance.

We further hypothesized that kinase activity may distinguish functional from non-functional Pm4 allelic variants. To test this, we evaluated the in vitro kinase activity of the proteins encoded by alleles Pm4a, Pm4f and Pm4g. Pm4a has been described to have a largely overlapping resistance spectrum against B. g. tritici with Pm4b, while Pm4f provides wheat blast resistance by recognizing the wheat blast effector AVR-Rmg8. Importantly, Pm4g was reported to lack resistance activity against both pathogens and is thus considered a non-functional allele11,12,13. We observed that both Pm4a and Pm4f isoforms exhibited auto- and transphosphorylation activity comparable to that of Pm4b, whereas Pm4g did not show detectable kinase activity (Extended Data Fig. 5a), further supporting the hypothesis that kinase activity is crucial for Pm4 resistance function.

Given the importance of kinase activity for Pm4 resistance and cell death induction, along with its ability to transphosphorylate proteins such as MyBP and its interaction and colocalization with AvrPm4, we investigated whether Pm4 can directly phosphorylate AvrPm4. To this end, we expressed MBP-tagged AvrPm496224 and the truncated virulence variant MBP–avrPm44AB-2 in E. coli, followed by protein purification using amylose resin. We incubated the purified effectors with Pm4b-V1, Pm4b-V2ΔTMD and the kinase-inactive mutant Pm4b-V1(D188N) as a negative control. Despite similar size ranges to Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD (indicated by asterisks), MBP–AvrPm496224 and MBP–avrPm44AB-2 (indicated by two squares and a circle, respectively) were clearly distinguishable from Pm4-derived bands (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 5b). Importantly, we observed phosphorylation of AvrPm496224 in the presence of Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2ΔTMD but not in the presence of the kinase-dead mutant Pm4b-V1(D188N) (Fig. 3f, square). Surprisingly, despite its inability to trigger cell death (Fig. 2), the virulence variant avrPm44AB-2 was also phosphorylated by both Pm4 isoforms (Fig. 3f, circle). These results confirm AvrPm4–Pm4 interaction in vitro but also suggest that phosphorylation of the Avr alone is insufficient to trigger an immune response.

B. g. tritici virulence on Pm4 is controlled by a suppressor locus on chromosome 8

Loss-of-function UV mutants of AvrPm4 result in virulence on both Pm4a and Pm4b (Fig. 1a). To elucidate the natural mechanism of B. g. tritici race specificity on Pm4a and Pm4b, we phenotyped a set of 78 B. g. tritici isolates selected from a worldwide collection33 on the near-isogenic lines (NILs) W804/8*Fed (Pm4b) and Khapli/8*CC (Pm4a) and their corresponding susceptible controls Federation (Fed) and Chancellor (CC). For most isolates, we observed identical virulence phenotypes on both Pm4 alleles (Supplementary Table 3), consistent with previous findings indicating that Pm4b and Pm4a have largely overlapping—although not identical—recognition spectra11.

We next assessed the genetic diversity of AvrPm4 in the same subset of 78 B. g. tritici isolates. AvrPm4 was present in all tested isolates, and it was largely conserved, with only 19 out of 78 isolates exhibiting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the coding sequence compared with the reference isolate CHE_96224 (Supplementary Table 3 and Extended Data Fig. 6). Importantly, no correlation was found between the AvrPm4 genotype and virulence phenotypes on Pm4b and Pm4a NILs. To rule out expression polymorphisms, we analysed available RNA-sequencing datasets and observed no significant variation in AvrPm4 expression between B. g. tritici isolates with contrasting phenotypes on Pm4, such as CHE_96224, CHE_94202 and ISR_7 (all avirulent on Pm4b/Pm4a) versus GBR_JIW2 (virulent on Pm4b/Pm4a) (Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8a)21,29. Taken together, these observations suggest that additional genetic components beyond AvrPm4 control virulence on Pm4. To identify such additional components, we used two independent approaches: GWAS and biparental QTL mapping.

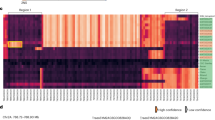

The above-mentioned B. g. tritici collection of 78 isolates, phenotyped on the NILs W804/8*Fed (Pm4b) and Khapli/8*CC (Pm4a), provided the basis for GWAS. Using an avirulent isolate as a reference (CHE_96224), GWAS revealed two significant genetic associations for virulence on Pm4b: a strong association at the end of chromosome 8, spanning from 10704663 to 10864069 bp in the reference assembly of CHE_96224, and a less pronounced association at the beginning of chromosome 4 (2736 to 457765 bp) (Fig. 4a). GWAS analysis on Pm4a revealed a single significant genetic association located on chromosome 8 (10721247 to 10841388 bp), overlapping with the locus identified for Pm4b (Fig. 4b).

a,b, GWAS analysis using 473,887 SNPs across the 11 B. g. tritici chromosomes, based on phenotypes of 78 isolates of the Pm4b NIL W804/8*Fed (a) and the Pm4a NIL Khapli/8*CC (b). The red dashed line indicates the significance threshold at P < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction. The genomic position of AvrPm4 is indicated by a grey dashed line. c, Results of a QTL analysis on Pm4a NIL Khapli/8*CC, using 118 F1 progenies of the biparental mapping population CHE_96224 (avirulent) × THUN-12 (partially virulent). The virulence phenotypes of the parental isolates on the Pm4a NIL are shown in the top left corner. The dashed line indicates the significance threshold logarithm of the odds (LOD) value at P < 0.05, determined by 1,000 permutations. d, Depiction of the genomic locus on chromosome 8 identified via GWAS and QTL analysis. Locus borders were defined on the basis of the GWAS analysis on the Pm4b NIL (W804/8*Fed). Candidate secreted effector genes are represented by yellow arrows, and non-effector genes by white arrows. Red triangles indicate candidate effectors exhibiting non-synonymous sequence polymorphisms between Pm4b/Pm4a virulent and avirulent reference isolates. The grey box indicates the location of the 13 best associated SNPs with the phenotype on Pm4b (W804/8*Fed) with an identical P value of 8.660015 × 10−12. Gene names are based on the gene annotation published for B. g. tritici reference isolate CHE_96224 (ref. 34). Gene models are not drawn to scale. Genomic confidence intervals identified by GWAS on Pm4b (blue), GWAS on Pm4a (dark green) or QTL mapping on Pm4a (light green) are indicated by coloured bars.

To complement the GWAS approach, we performed QTL mapping on Pm4a, using a biparental cross (originally described in ref. 34) between the Pm4a/b-avirulent B. g. tritici isolate CHE_96224 and the B. g. triticale isolate THUN-12, which displays partial virulence on Pm4a but is avirulent on Pm4b (Fig. 4c). To do so, we phenotyped 118 F1 progenies on the Pm4a NIL Khapli/8*CC and conducted a QTL analysis using 119,023 genetic markers between the parental isolates. Remarkably, a single QTL was identified on chromosome 8, spanning from positions 9931004 to 10932716 in the CHE_96224 reference assembly, overlapping with the chromosome 8 locus detected in the GWAS analysis (Fig. 4c).

Consistent with our previous observation that genetic diversity within AvrPm4 does not correlate with virulence phenotypes on Pm4b or Pm4a, neither GWAS nor QTL mapping identified a significant genetic association with the AvrPm4 gene located on chromosome 5 (Fig. 4a–c). Instead, both complementary approaches provide strong evidence for the presence of a major genetic component on chromosome 8 controlling B. g. tritici virulence on the Pm4b and Pm4a resistance alleles. Given that loss-of-function mutations in AvrPm4 alone are sufficient to result in virulence on Pm4b and Pm4a (Fig. 1a), it is unlikely that the locus on chromosome 8 contains an additional Avr component. We therefore hypothesized that this region contains a suppressor of avirulence (SvrPm4), which interferes with AvrPm4 recognition by Pm4.

SvrPm4 (Bgt-51526 JIW2) suppresses AvrPm4/Pm4-induced cell death in wheat protoplasts

We defined SvrPm4 candidate genes within the identified locus on chromosome 8 of the Pm4-avirulent isolate CHE_96224 on the basis of the GWAS analysis on Pm4b (Fig. 4d). Focusing on effector genes with a predicted signal peptide, we identified three candidate genes within this interval: Bgt-51526, BgtAcSP-30824 and BgtAcSP-31023. Analysis of their expression levels during infection in four RNA-sequenced B. g. tritici reference isolates exhibiting differential phenotypes on Pm4b and Pm4a (avirulent: CHE_96224, CHE_94202 and ISR_7; virulent: GBR_JIW2) revealed no major expression polymorphisms (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). We therefore focused on sequence polymorphisms between avirulent and virulent reference isolates to define promising SvrPm4 candidates. Whereas BgtAcSP-30824 did not exhibit any sequence polymorphisms, both Bgt-51526 and BgtAcSP-31023 were consistently polymorphic between the Pm4-virulent reference isolate GBR_JIW2 and the avirulent isolates CHE_96224, CHE_94202 and ISR_7. We found that the effector protein Bgt-51526JIW2 differs by 27 amino acids from Bgt-5152696224, whereas BgtAcSP-31023JIW2 exhibits two amino acid polymorphisms and a premature stop codon at position 142 of the effector protein, compared with BgtAcSP-3102396224, found in avirulent isolates (Fig. 5a). We therefore considered both genes as SvrPm4 candidates and proceeded to test their ability to suppress Pm4-mediated cell death in wheat protoplasts.

a, Protein sequence alignment of SvrPm4 candidates BgtAcSP-31023 and Bgt-51526 haplovariants found in the Pm4-virulent isolate GBR_JIW2 and in the Pm4-avirulent isolate CHE_96224. GBR_JIW2 is shown as a reference, with polymorphic residues in CHE_96224 highlighted. b, Wheat protoplast assay showing the suppression of AvrPm4-induced cell death by SvrPm4JIW2. Protoplasts isolated from the transgenic wheat line #52, overexpressing Pm4b (used in Fig. 2), were transfected with each Svr candidate individually or cotransfected with AvrPm4. Presumed suppressor-active candidates (BgtAcSP-31023JIW2 and Bgt-51526JIW2) and suppressor-inactive candidates (BgtAcSP-3102396224 and Bgt-5152696224) were tested. The experiment was performed twice with three biological replicates each (n = 6 total). The height of the bars shows the mean value for all the replicates, and the whiskers show the standard deviation. c, HR response in N. benthamiana upon Agrobacterium-mediated co-expression of Bgt-51526JIW2 or Bgt-5152696224 and Pm1a-HA or a negative GUS control. Close-up images of the HR response are shown at the top. The full-size image of the corresponding N. benthamiana leaf is provided in Extended Data Fig. 10. The assay was performed three times with n = 6 leaves per experiment (n = 18 total). In each box plot, the median is shown as a central line within a box that spans from the 25th to the 75th percentile. The inner whiskers show the 95% confidence interval of the median, and the outer whiskers show the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range. For all experiments, significance and P values (significance threshold of P < 0.05) were calculated with a two-sided ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test (Supplementary Table 3). Bars or boxes with the same letter are not significantly different.

We codon-optimized the two candidate genes without signal peptides and cotransfected them with a YFP reporter into protoplasts from the transgenic wheat line #52 stably expressing Pm4b-V1 and Pmb4b-V2, as described above. In the absence of AvrPm4, none of the SvrPm4 candidates triggered cell death in the Pm4 transgenic line, consistent with our initial hypothesis that the locus on chromosome 8 does not contain an Avr but rather an Svr factor (Fig. 5b). However, co-expression of Bgt-51526JIW2 with AvrPm4 significantly reduced the cell death response, whereas neither Bgt-5152696224 nor either of the two BgtAcSP-31023 variants had any detectable suppressive effect (Fig. 5b). We therefore concluded that Bgt-51526JIW2 (hereafter SvrPm4JIW2) is indeed a suppressor of Pm4-mediated cell death, whereas Bgt-5152696224 (hereafter svrPm496224) is unable to suppress Pm4 activity.

Among the 78 tested B. g. tritici isolates, we found extensive sequence variation within the SvrPm4 gene, identifying ten highly polymorphic haplovariants (Extended Data Fig. 9a and Supplementary Table 3). Importantly, all isolates carrying the inactive variant svrPm496224 exhibit an avirulent phenotype on Pm4b and Pm4a, whereas all isolates carrying SvrPm4JIW2 are virulent on both Pm4 alleles (Extended Data Fig. 9b), highlighting the importance of SvrPm4 in overcoming Pm4 resistance. We identified multiple other haplovariants that were exclusively present in either avirulent or virulent isolates, thereby probably representing additional inactive and active SvrPm4 variants, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Intriguingly, we also found three haplovariants (variants E, H and I in Supplementary Table 3) associated with B. g. tritici isolates showing differential phenotypes on Pm4b and Pm4a, suggesting that SvrPm4 allelic variation may contribute to the subtle differences in Pm4b and Pm4a recognition spectra (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Taken together, our data suggest a genetic two-component system controlling virulence on Pm4 in natural B. g. tritici isolates, in which the ability to overcome Pm4-mediated resistance is independent of the AvrPm4 genotype but rather controlled by the presence of the suppressor SvrPm4.

The active suppressor SvrPm4JIW2 but not svrPm496224 is recognized by the wheat NLR Pm1a

The gene Bgt-51526 (SvrPm4) encodes an RNase-like effector protein that was previously identified as an Avr recognized by the NLR immune receptor encoded by the wheat resistance gene Pm1a35. To determine whether SvrPm4JIW2 (defined as Bgt-51526_2 variant in ref. 35) and the previously undescribed svrPm496224 variant induce differential HR responses, we co-expressed each variant with Pm1a in N. benthamiana. Consistent with previous findings, we observed a strong HR response upon co-expression of SvrPm4JIW2 and Pm1a, confirming this variant’s avirulence towards Pm1a. Note that co-expression of svrPm496224 and Pm1a did not result in an HR response (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 10). We thus conclude that SvrPm4JIW2 is simultaneously an active suppressor of Pm4 and an Avr of Pm1a, whereas the inactive suppressor svrPm496224 escapes Pm1a recognition.

Discussion

Avirulence on Pm4 is controlled by at least two genes in B. g. tritici. AvrPm4 is an avirulence factor, and its disruption results in virulence on both Pm4a and Pm4b. Furthermore, AvrPm4-triggered immunity is suppressed by SvrPm4. This multi-component system was uncovered using UV mutagenesis, GWAS and QTL mapping, illustrating how the combination of gene identification tools allows the dissection of genetically complex systems in biotrophic fungal plant pathogens such as B. g. tritici.

Previously identified Avr effectors in B. g. tritici encode small (100–155 amino acid residues) RNase-like effectors recognized by NLR receptors23. In contrast, AvrPm4, recognized by the KFP Pm4, is a 372-residue chimeric protein with an N-terminal RNase-like domain and a C-terminal MEA domain and differs substantially from previously identified B. g. tritici Avr proteins.

Recent studies revealed that the Pm4 resistance gene corresponds to previously identified wheat blast resistances Rmg7 and Rmg8, and established that Pm4a, Pm4b and Pm4f can recognize the wheat blast effector AVR-Rmg8 (refs. 12,13). AVR-Rmg8 (110 residues) is considerably smaller than AvrPm4 and lacks an RNase-like domain14. However, it shares a nearly identical sequence motif with the MEA domain of AvrPm4 (Fig. 1c), suggesting the importance of this domain for Avr recognition by Pm4/Rmg8. Interestingly, we found that the MEA domain of AvrPm4 shows sequence similarity to MED15, a crucial coactivator in eukaryotic transcription, and to EBNA-3B from the Epstein–Barr virus, which is also implicated in transcriptional control (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 2)31,32,36. Additionally, the AvrPm4 MEA domain has a predicted NLS and a high probability of binding DNA (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). Future experiments should therefore explore whether the MEA domain plays a role in transcriptional manipulation of the host, which may contribute to B. g. tritici virulence. AvrPm4 and AVR-Rmg8 are conserved within the gene pools of B. g. tritici and wheat blast, respectively, indicating an important role of these effectors in pathogen fitness. Considering that the MEA domain might also be implicated in Avr recognition, as suggested by the nearly identical sequence motifs shared by AvrPm4 and AVR-Rmg8, this might represent an important trade-off between preservation of effector function and evasion of Pm4 recognition for the fungal pathogen.

Mutation or loss of Avr effectors is a common mechanism to evade R-gene-mediated immunity in fungal plant pathogens37. The loss of Avr effectors with crucial virulence functions might, however, result in reduced pathogen fitness. Multiple fungal plant pathogens therefore secrete suppressor proteins to mask Avr effectors or suppress NLR-mediated immunity, thereby allowing them to retain important Avr effectors24. Previous studies in B. g. tritici identified SvrPm3, an RNase-like effector that suppresses the recognition of AvrPm3 effectors by NLR-type Pm3 resistance proteins19,27. Like SvrPm3, the SvrPm4 effector belongs to the group of RNase-like effectors. Our study reveals that a member of this large effector group suppresses recognition by a KFP immune receptor. This underscores the diversity of molecular activities of these effectors and their importance as suppressors of race-specific resistance. Intriguingly, a study in the blast pathogen (Magnaporthe spp.) has identified the PWT4 effector, naturally present in oat-infecting blast isolates, as a suppressor of Pm4 (Rmg8) when expressed in wheat blast38. This finding further highlights the similarities in genetic control of avirulence/virulence on Pm4 between the powdery mildew and blast pathosystems.

Our GWAS and QTL analyses indicate that SvrPm4 is the main factor controlling virulence on Pm4a and Pm4b in the global B. g. tritici population (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 9). The importance of the SvrPm4 locus is further corroborated by the fact that a genetic association between this locus and Pm4 resistance in wheat was also described in a recent study using host–pathogen biGWAS39. Importantly, besides the active SvrPm4JIW2 and the inactive svrPm496224 variants, we found a staggering array of additional SvrPm4 variants in the B. g. tritici population that so far remain untested for their ability to suppress Pm4. Phenotype–genotype correlations suggest that additional SvrPm4 variants may act as active suppressors against Pm4 (Extended Data Fig. 9), while others might target only a subset of Pm4 alleles, thereby probably explaining the subtle differences in recognition spectra provided by different Pm4 alleles11 (see also this study).

The SvrPm4 effector gene (Bgt-51526) was previously described as an Avr factor of the wheat NLR-encoding gene Pm1a35. Interestingly, we found that the active suppressor variant SvrPm4JIW2 triggers Pm1a-mediated HR in N. benthamiana, while the inactive variant SvrPm496224 evades Pm1a recognition (Fig. 5c). This observation suggests that combining Pm4 and Pm1a in the same wheat genotype could provide complementary resistance activities towards B. g. tritici. Considering the diversity of the SvrPm4 gene, it will be important to establish whether the suppression of Pm4 and the evasion of Pm1a recognition are indeed mutually exclusive, which would allow the efficient generation of disruptive selection pressures on this effector through the combination of Pm4 and Pm1a in wheat breeding programmes. We hypothesize that such an approach may prove more robust than R gene stacks using independently acting resistance genes and could therefore represent a promising strategy to achieve durable resistance against B. g. tritici in wheat.

The GWAS analysis on Pm4b revealed a second minor locus residing on chromosome 4. However, the same locus did not show a significant association with virulence on Pm4a and was also not identified in our QTL mapping analysis, indicating that it represents a minor or Pm4b-specific factor. Future studies should dissect the complex interactions between the largely conserved AvrPm4, the large diversity of SvrPm4 and their consequences for Pm4 suppression as well as the potential existence of additional minor factors.

The Pm4 gene exhibits alternative splicing that results in two isoforms, Pm4-V1 and Pm4-V2, which share an identical kinase domain and are both necessary for resistance. Pm4b-V1 localizes to the cytoplasm but relocalizes to the ER membrane upon co-expression with Pm4b-V2 (ref. 11). We found that AvrPm4 interacts with both isoforms and relocalizes from the cytoplasm to the ER membrane upon co-expression with Pm4b-V2 (Fig. 3a–d). Furthermore, we found evidence for auto- and transphosphorylation activities of both Pm4 isoforms that result in AvrPm4 phosphorylation (Fig. 3e,f). The importance of Pm4 kinase activity for resistance is further highlighted by the observation that all Pm4 alleles with documented resistance activity against either B. g. tritici or wheat blast (namely, Pm4a, Pm4b and Pm4f) exhibit kinase activity, while the non-functional Pm4g allele does not. Strikingly, when investigating the ability of Pm4 to phosphorylate AvrPm4, we also observed phosphorylation of the non-recognized, truncated avrPm44AB-2 variant. This suggests that AvrPm4 phosphorylation alone is not decisive for the initiation of Pm4-mediated cell death. This finding contrasts with a recent report that observed phosphorylation of the Avr protein PWT4 in the presence of the KFP RWT4 but did not detect phosphorylation of a non-recognized PWT4 variant17. These differences could indicate that molecular resistance mechanisms among KFPs are diverse, similar to the functional diversity observed for NLR-type immune receptors.

The wheat KFPs Sr62 and WTK3 were recently found to depend on an NLR protein for HR induction7,8. Consistent with the existence of another wheat component, Pm4 and AvrPm4 co-expression in the heterologous N. benthamiana system failed to trigger HR (Extended Data Fig. 3). We therefore hypothesize that Pm4, like other KFPs, relies on another host protein, possibly an executor NLR conserved in the wheat gene pool, for cell death induction. Identifying this unknown component should be a priority of future studies to mechanistically understand the induction of Pm4-mediated resistance. Additionally, the striking parallels between B. g. tritici and wheat blast pathogens and their Avr and Svr effectors in the context of Pm4/Rmg8 resistance provides the unique opportunity to study the complex molecular events during Pm4-mediated immunity in two evolutionarily distant pathosystems.

With a quickly increasing number of identified and characterized R/Avr pairs, in both powdery mildew and wheat blast, a complex molecular network also involving suppressors, modifiers and additional resistance genes has begun to be unravelled. In fact, besides Pm4/Rmg8/Rmg7, recent studies showed further parallels between cereal powdery mildew and wheat blast pathosystems. The wheat RWT4 resistance gene, identified as a key host-specificity factor against the blast pathogen, is allelic to the B. g. tritici resistance gene Pm24 (ref. 16), and the barley powdery mildew resistance gene MLA3 recognizes the wheat blast effector PWL2 (ref. 40). Moreover, our finding that the active suppressor of Pm4, SvrPm4JIW2, is recognized by the NLR Pm1a, while the inactive svrPm496224 evades recognition, further highlights the complexity of the R–Avr molecular networks even within the wheat powdery mildew pathosystem. In conclusion, our study advocates for a shift from single-gene strategies to resistance gene stacking, combining kinase-based receptors such as Pm4 with NLRs such as Pm1a. We advocate joint wheat breeding programmes for mildew and blast resistance to efficiently use overlaps and synergies between resistance sources, resulting in multilayered and potentially more durable pathogen resistance.

Methods

Fungal and plant material and phenotyping experiments

The B. g. tritici reference isolate CHE_96224 and the mapping population CHE_96224 × THUN-12 were previously described34. The 78 B. g. tritici isolates used for virulence phenotyping and GWAS analysis were selected from a worldwide diversity panel33. Isolates were maintained clonally on leaf segments of the susceptible wheat cultivar Kanzler (K-57220) placed on food-grade agar (0.5% PanReac AppliChem) supplemented with 4.23 mM benzimidazole (Merck; CAS 51-17-2)41.

The NILs Khapli/8*CC/8*Fed (Pm4a), Khapli/8*CC (Pm4a) and W804/8*Fed (Pm4b) were previously described11. The Pm4b-overexpressing transgenic line (event #52; ref. 11) was self-fertilized to the T4 generation, producing T5 homozygous Pm4b transgenic plants. A segregating, transgene-free sister line (S#52) was used as a control. For virulence specificity testing of B. g. tritici mutants, NILs with specific resistance genes were used: Axminster/8*Chancellor (Pm1a)42, Federation*4/Ulka (Pm2a)43, Asosan/8*Chancellor, Chul/8*Chancellor, Sonora/8*Chancellor, Kolibri and Michigan Amber/8*Chancellor (Pm3a, Pm3b, Pm3c, Pm3d and Pm3f, respectively)44, transgenic Pm3e#2 (Pm3e)45, Kavkaz/4*Federation (Pm8)46, USDA_Pm24 (Pm24) and “Amigo” (1AL.1RS translocation line, Pm17)47. Additionally, A. tauschii accessions TOWWC087, TOWWC112 and TOWWC154 were included (WTK4)48.

B. g. tritici virulence phenotyping was performed using the primary leaf of 8–12-day-old wheat seedlings, grown under 16 h light/8 h dark cycles at 18 °C and 60% humidity. The leaves were cut into 3-cm fragments and placed on Petri dishes with 0.5% water-agar containing 4.23 mM benzimidazole (Merck; CAS 51-17-2). Spores were collected with a funnel and blow-inoculated onto the Petri dish. The phenotype was then evaluated by eye as the percentage of leaf coverage by sporulating colonies (0–100%) after six to eight days.

Mutagenesis and mutant analyses

B. g. tritici mutants were isolated as described previously22. Briefly, spores of the avirulent isolate CHE_96224 were irradiated with UV light and propagated on cv. Kanzler three times, before being used for infecting Pm4a- and Pm4b-containing NILs (see above). Colonies growing on Pm4a or Pm4b NILs were isolated from single spores, and their virulence phenotype was confirmed via an infection test. Finally, spores were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground using a tissue homogenizer, and DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB method (as described previously19). Library preparation and Illumina sequencing were performed at the Functional Genomics Center Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland) and Novogene (Cambridge, UK) using NovaSeq 6000 technology, as described previously22.

The raw reads obtained were trimmed using Trimmomatic v.0.39 (ref. 49), then mapped to the reference genome of the B. g. tritici isolate CHE_96224, v.3.16 (ref. 34) using bwa mem v.0.7 (ref. 50). The last steps involved sorting, removing duplicates and indexing the bam files, using Samtools v.1.9 (ref. 51). Haplotype calling, transposable element insertions and gene deletions or duplications were performed as described previously22. As performed in our previous study, variants less than 1.5 or 2 kb away (for SNPs and transposable element insertions, respectively) from annotated genes were considered for further investigations (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Confocal imaging

Live-cell imaging was performed using a Stellaris 5 inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with an external fluorescence light source (Lumencor LED3), a 405-nm diode laser, and a Leica white light laser. Confocal imaging was conducted as previously described11, with minor modifications. Briefly, four-week-old N. benthamiana plants were infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying the plasmids of interest. Three days post infiltration, 5 mm × 5 mm leaf samples were mounted between a glass slide and a coverslip in a drop of water. Fluorescence was observed using the following excitation and emission settings: mTurquoise, excitation at 405 nm, emission collected between 425 and 522 nm; Venus, excitation at 515 nm, emission collected between 520 and 550 nm; mCherry, excitation at 587 nm, emission collected between 592 and 652 nm. Fluorescence intensities in the cytosol and ER were measured using the Plot Line plugin in Fiji (https://fiji.sc/). All experiments were conducted under strictly identical confocal acquisition parameters, including laser power, gain, zoom factor, resolution and emission detection settings, ensuring minimal background noise and avoiding pixel saturation. Pseudo-coloured images were generated using the ‘Green’, ‘Magenta’ and ‘Turquoise’ look-up tables in Fiji.

Cloning of expression constructs

The coding sequences of AvrPm496224, avrPm44AB-2, avrPm44AB-6, SvrPm4JIW2, SvrPm496224 and BgtE-576496224 lacking the signal peptide (as detected by SignalP4.0; ref. 52), were codon-optimized for wheat expression using the codon-optimization tool from Integrated DNA Technologies (https://eu.idtdna.com) and subsequently gene-synthesized by our commercial partner BioCat GmbH (https://www.biocat.com). Codon-optimized SvrPm4 variants were cloned into the Gateway-compatible pENTR plasmid using In-Fusion cloning (Takara Bio) and then mobilized into the binary expression vector pIPKb004 (ref. 53) using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen). The pIPKb004-Pm1a-HA construct has been previously described42. AvrPm496224, avrPm44AB-2, BgtE-576496224 and WTK4 were cloned into the Gateway-compatible pDONR207 plasmid and then into the destination vectors for the split-luciferase assay (GW_NLUC, NLUC_GW, GW_CLUC and CLUC_GW54) using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen); LUC-tagged Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2 have been previously described11. For wheat protoplast expression, all previously described constructs were cloned into the pTA22 vector55. Additionally, avrPm44AB-6, AvrSr50 (ref. 56), AvrPm3a2/f2 (ref. 19), Pm4b-V1, Pm4b-V2, and GUS were PCR amplified, cloned into the pDONR207 vector and subsequently transferred into the binary expression vector pTA22 using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen). YFP-pTA22 was used as described previously55.

The coding sequence for mTurquoise-AvrPm496224 was codon-optimized for plant expression using the optimization tools provided by Integrated DNA Technologies (https://eu.idtdna.com). Synthesis of mTurquoise-AvrPm496224, mCherry-Pm4b-V1 and Venus-Pm4b-V2 as well as cloning into the Gateway-compatible vector pDONR221 was performed by Life Technologies Europe BV (Thermo Fisher Scientific). These constructs were subsequently transferred into the binary expression vector pIPKb004 (ref. 53) using LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen).

The coding sequences of Pm4b-V1, Pm4b-V1D170N, Pm4b-V1D188N, Pm4a-V1, Pm4f-V1 and Pm4g-V1 (full-length variants), as well as Pm4b-V2ΔTMD, Pm4b-V2ΔTMDD170N, Pm4b-V2ΔTMDD188N, Pm4a-V2, Pm4f-V2, Pm4g-V2 (kinase + C2D domain), AvrPm496224 and avrPm4AB22, were PCR amplified and cloned in frame into the vector pMAL-C4E between the restriction sites EcoRI and BamHI, to generate fusion proteins carrying an N-terminal MBP tag57. Ligation of the PCR product and vector backbone was performed using T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs). The His–MBP Exon 1–5 coding sequence was PCR amplified using primers PC_90 and PC_91 with flanking BsaI recognition sites and unique overhangs to enable directional and seamless assembly. The construct was assembled using the Golden Gate cloning system, using type IIS restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase in a one-tube reaction. The assembled product was cloned into the destination vector pET28a(+)-GG.

The constructs were verified via full plasmid sequencing (Microsynth AG). The primers used for cloning are listed in Supplementary Table 4. All codon-optimized effector and resistance gene sequences used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 5. All expression constructs were transformed into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 via electroporation.

Cell death assay in wheat protoplasts

For the cell death assay in wheat protoplasts, we followed the description in a previous study55. Briefly, Avr genes and R genes were cloned into the plasmid pTA22 without tags and subsequently extracted using the Xtra Midi Plus Endotoxin-free MidiPrep Kit (Macherey-Nagel). The DNA was eluted in ultra-pure water. Transgenic seedlings of susceptible cultivar Bobwhite S26 overexpressing Pm4b (#52) and its respective sister line (S#52) were grown in a chamber under a cycle of 12 h light (100 µmol m−2 s−1) and 12 h dark at 24 °C for seven days. The protoplasts were isolated by peeling off the epidermis and digesting the leaf in a cellulase RS and macerozyme R-10 (Onozuka; Yakult Honsha) solution (enzyme solution: 20 mM MES-KOH, 0.6 M mannitol, 10 mM KCl, Cellulase RS 1.5% (w/v), Macerozyme R-10 0.75% (w/v), 10 mM CaCl2, bovine serum albumin (BSA) 0.1% (w/v)). After the purification steps, performed as previously described55, the protoplast solution was diluted to a concentration of 3 × 105 cells per millilitre. The different plasmids were mixed for transfection in a 2-ml tube. Three picomoles (3 pmol) of the plasmids containing YFP and the individual Avrs were used for transfection. Due to Pm4b-V2 autoactivity and to maintain an equal ratio between Pm4b-V1 and Pm4b-V2, 0.5 pmol of plasmids containing Pm4b-V1, Pm4b-V1D188N, Pm4b-V2 and Pm4b-V2D188N were used. Where one DNA component is missing, the amount of DNA was compensated with a GUS-expressing construct. Two hundred microlitres of protoplasts were then added to the DNA together with a PEG solution (volume PEG solution, 200 μl; volume of DNA mix, ~230 μl; 40% w/v PEG-4000, 0.2 M mannitol, 100 mM CaCl2). After a gentle homogenization, the transfection reaction was stopped by adding W5 solution (2 mM MES-KOH, 5 mM KCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 154 mM NaCl). All the reagents used for preparing the solutions were from Sigma-Aldrich. After the protoplasts were transferred into a 12-well cell culture plate, they were incubated at 23 °C for 16–20 h in the dark. The next day, YFP fluorescence was measured (excitation, 500 nm; emission, 541 nm) with two technical replicates and three biological replicates per treatment using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek Instruments). Each experiment was repeated two to three times as indicated in the figure legends. All the measurements were normalized to the average of values from the GUS-transfected protoplasts for each experiment individually.

Agrobacterium-mediated gene expression in N. benthamiana

Agrobacterium-mediated expression in N. benthamiana was performed as previously described27. In brief, A. tumefaciens (strain GV3101) was grown in liquid lysogeny broth (LB) containing appropriate antibiotics overnight at 28 °C. For N. benthamiana infiltration, cultures were briefly washed in LB medium and resuspended in infiltration medium (200 µM acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES-KOH pH 5.6) to an OD600 of 1.2 for HR testing, and to an OD600 of 1 for split-luciferase and colocalization experiments, subsequently incubated at 28 °C for two to four hours and finally infiltrated into leaves of three- to four-week-old N. benthamiana plants.

Split-luciferase assay

All the constructs co-infiltrated were previously mixed in a 1:1:1 ratio with the third component being the p19-silencing-suppressor strain58. Transient expression via agroinfiltration in N. benthamiana was performed as described above. At three days post infiltration, 6-mm leaf discs were collected from each leaf and incubated in buffer containing 10 mM MES-KOH (pH 5.6) and 10 mM MgCl2. Subsequently, 1 mM luciferin (BioVision) in 0.5% DMSO was added, and after 5 min of incubation, luminescence was measured for 25 min (200 ms per well) using the LUMI imaging system (Tecan). The sum of the values per well was then used for statistical analyses. Two technical replicates and at least 16 biological replicates were measured for each treatment, for a total of three experiments.

Recombinant protein expression, purification and in vitro kinase assays

The N-terminally MBP-tagged constructs in the pMAL-c4E vector57 were transformed into BL21 pLYsS chemically competent Rosetta cells. Ten millilitres of an overnight culture was added to 1 l of LB media, the respective antibiotic and 20% glucose to an OD of 0.6 to 0.8. Protein expression was then induced with 300 mM IPTG, and the cells were grown overnight with shaking at a reduced temperature of 18 °C.

After the cells were harvested via centrifugation at 5,000 g for 20 min, the pellet was resuspended in 40 ml of purification buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 5% glycerol and 1x protease inhibitor tablets (cOmplete EDTA-free; Roche)) and lysed via sonication (4 × 20 s with 40-s breaks at high intensity). Next, the lysed cells were centrifuged at 35,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was further incubated with washed amylose resin (New England Biolabs) and an addition of 2 mM DTT and 300 mM NaCl. After 30 min of incubation at 4 °C on an overhead rotation system, the resin was collected via centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The extraction was then washed four times with a wash buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 5% glycerol and 300 mM NaCl, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail). The proteins of interest were then eluted using a maltose elution buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 5% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl and 200 mM maltose, 2 mM DTT). To exchange the buffer in which the proteins were eluted, the samples were run through 50-kDa exclusion centrifuge filters (Amicon, Ultra Zentrifugenfilter, 50 kDa MWCO) and diluted with the elution buffer lacking maltose. MBP–AvrPm496224 (expected size, 80 kDa) migrated as a band at around 110 kDa, with degradation products ranging from 110 to 70 kDa, while MBP–avrPm44AB-2 (expected size, 67 kDa) appeared as a strong band at 85 kDa and a minor band at 70 kDa (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Removal of the MBP tag from the AvrPm4 constructs resulted in insoluble protein. We therefore used tagged AvrPm4 proteins for the experiments (Extended Data Fig. 5b).

Expression and purification of the N-terminally His–MBP-tagged Exon1–5 construct were carried out following a previously described protocol59, with some modifications. For this construct, the lysis buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). For the purification procedure, HisPur Cobalt Resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. The wash buffer contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole and 1 mM PMSF. Proteins were eluted from the resin at 4 °C using elution buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 250 mM imidazole. Protein purity and concentration were assessed via SDS–PAGE, using BSA as a standard (loading 1 µg, 0.5 µg, 0.25 µg and 0.1 µg of BSA, respectively). The proteins (samples and BSA standard) were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, and protein abundance was estimated on the basis of band intensity analysis using ImageJ (version 1.54)60.

For the in vitro kinase assay, 1 µg of purified protein was incubated in a 20-µl reaction containing 1 µCi [γ-32P]ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnCl2, 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 5% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl and 2 mM ATP for 60 min at 37 °C. Proteins were separated via SDS–PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane, which was then exposed overnight to a phosphor screen before imaging using the Amersham Typhoon system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Protein detection

Immunoblotting was initiated by blocking the membrane with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. MBP-tagged proteins were detected using anti-MBP antibody (New England Biolabs; IgG2a, E8032S) at a 1:3,000 dilution. For LUC-tagged proteins, a polyclonal anti-luciferase antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; L0159) was used at 1:3,000 dilution, followed by a secondary anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated antibody (LabForce; sc-2357), also at 1:3,000 dilution. Detection of mTurquoise- and Venus-tagged proteins was carried out using anti-GFP antibody (clone B-2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-9996) at a 1:5,000 dilution. mCherry-tagged proteins were detected using anti-RFP antibody (clone 6G6; Chromotek) at a 1:5,000 dilution. In both cases, the corresponding secondary antibody was an anti-mouse HRP-conjugated antibody (Promega; W402B) at 1:10,000 dilution. Peroxidase chemiluminescence was detected using a Fusion FX Imaging System (Vilber Lourmat) after the application of Western Bright ECL HRP substrate (Advansta). The SuperSignal West Femto substrate (Thermo Scientific) was used when maximum sensitivity was required.

HR measurement in N. benthamiana

To assess HR responses upon co-expression of effector and R genes, Agrobacterium cultures were prepared as described above and mixed in a 4:1 ratio (effector:R) prior to infiltration. Four to five days post infiltration, imaging and quantification of HR responses were achieved using a Fusion FX Imaging System (Vilber Lourmat) and ImageJ as previously described27.

Total protein extraction from N. benthamiana

N. benthamiana tissue for total protein extraction was harvested three days after Agrobacterium infiltration by cutting ten leaf disks (6 mm in diameter) from three independent plants and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were collected in a 2-ml tube with three glass beads and next ground using a tissue homogenizer. Then, 1.5× Lämmli buffer was added, and the samples were incubated at 95 °C for 10 min. After 1 min of centrifugation at 16,200 g, the supernatant was collected. The proteins in the supernatant were separated via SDS–PAGE and subsequently blotted onto a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane, which was then subjected to immunoblotting (described above).

Structural modelling and other bioinformatic analyses

Domain prediction of AvrPm496224 was performed with an NCBI conserved domain search (available through https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi). Modelling of AvrPm496224 was performed using AlphaFold3, available through https://alphafoldserver.com/. Structural alignment of AvrPm4 with AvrPm2 (Extended Data Fig. 2a) was performed with TMalign61. The dot plot of AvrPm496224 was visualized using in-house software by T.W. based on the program dotter (available through Ubuntu repositories). Protein alignments were performed with ClustalOmega and visualized using CLC Main Workbench. The NLS was predicted using NLStradamus (http://www.moseslab.csb.utoronto.ca/NLStradamus/). The DNA binding probability was predicted using DP-bind (https://lcg.rit.albany.edu/dp-bind/) with the standard parameters; the raw data are in Supplementary Table 6. Bins of ten amino acid residues containing their average value (between 0 (non-binding) and 1 (binding)) were created and used for producing the density plot depicted in Extended Data Fig. 3d.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R/RStudio (v.4.3.1 (ref. 62) and v.2023.06.1 (ref. 63), respectively). To evaluate differences between treatments in all protoplast and N. benthamiana cell death assays, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test was performed (R package multcomp)64. For the split-luciferase assay, an ANOVA followed by multiple comparison of means was performed. To assign letters, the commands glht and cld from the R package multcomp64 were used. Package ggplot2 (ref. 65) was used for producing the graphs. The raw data are in Supplementary Table 7.

GWAS analysis

For the GWAS analysis, Illumina resequencing data were mapped against the B. g. tritici reference genome (Bgt_genome_v3_16) following a procedure described previously21. SNPs were identified using the FreeBayes tool with the command freebayes -p 1 (v.1.3.6)66. The identified polymorphic sites were then filtered using VCFtools (v.0.1.16)67 with the following specifications: max-alleles, 2; min-alleles; maf, 0.05; max-missing, 0.95; minDP, 8. They were then transformed to hapmap format using a custom Perl script available here: https://github.com/MarionCMueller/Scripts/tree/main/vcf_to_hapmap/. Subsequently, GWAS analysis was conducted with virulence phenotyping data of 78 B. g. tritici isolates on NILs Khapli/8*CC (Pm4a) and W804/8*Fed (Pm4b) (Supplementary Table 3) using GAPIT (v.3)68 with the following specifications: PCA.total = 3, model = c(“MLM”).

To estimate the interval underlying a significant association in the GWAS analysis, the pairwise R2 values between markers on chromosomes 4 and 8 with less than 1 Mbp distance were determined using the VCFtools commands ld-window-bp, 1000000; max-alleles, 2; min-alleles, 2; geno-r2 (v.0.1.16)67. Finally, SNPs with an R2 value greater than 0.6 upon pairwise comparison with the most significantly associated SNPs of the GWAS analysis were used to define the genomic candidate interval.

QTL mapping

QTL mapping was performed on the basis of the previously described genetic map of the cross between THUN-12 (B. g. triticale) and CHE_96224 (B. g. tritici)34,42, which is available from https://github.com/MarionCMueller. The QTL analysis was performed using the r/qtl package in R (v.1.70)69. First, the genetic map was processed using the command jittermap and calc.genoprob(step = 2,error.prob = 0.001), followed by QTL analysis using the command scanone(model = “np”). The significance threshold at α = 0.05 was determined via calculating 1,000 permutations with scanone. The 1.5LOD interval was determined using lodint.

Candidate identification and expression analysis of SvrPm4 candidates

To identify SvrPm4 candidate genes, the candidate interval on chromosome 8 was first inspected for spurious annotations. Two gene models were detected, Bgt-51527 and Bgt-20620-4, which lacked either a start or stop codon. These genes were therefore excluded from subsequent analysis. Next, sequence variants of the three candidate effectors located in the interval (Bgt-51526, BgtAcSP-30824 and BgtAcSP-31023) were detected in a set of reference isolates (CHE_96224, CHE_94202, GBR_JIW2 and ISR_7) on the basis of resequencing data (Supplementary Table 3).

To accurately determine the expression levels of the three candidate effector genes in the isolates CHE_96224, CHE_94202, GBR_JIW2 and ISR_7, RNA sequencing data from these isolates on the susceptible wheat cultivar Chinese Spring were used at two days post inoculation21,29. To quantify transcript abundance, the annotation of CHE_96224 was used (available at https://zenodo.org/records/7018501). To avoid quantification biases, the coding sequences of all gene variants present in the four reference isolates to the CHE_96224 coding sequence annotation file were added. Finally, the new Fasta file was processed using the salmon index command from the salmon package (v.1.4.0)70, with the chromosomes of the Bgt_genome_v3_16 assemblies as decoys. Transcripts were quantified using the salmon quant −l A command. Subsequently, expression data across all variants for each isolate were merged in R, and RPKM values were calculated using the rpkm function from the package edgeR (v.4.0.16)71.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw FASTA sequences of all B. g. tritici mutants generated in this study are available through NCBI (BioProject ID: PRJNA1016363). Sequences of the B. g. tritici isolates used for GWAS were previously described33 and are available through NCBI (PRJNA625429, SRP062198). The B. g. tritici isolates used in this study are maintained at the University of Zurich and are available upon request. However, as the isolates may die over time, their long-term accessibility cannot be guaranteed. Source data are provided with this paper. All remaining data are provided in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Code availability

The Perl script used for converting VCF to HapMap is available at: https://github.com/MarionCMueller/Scripts/tree/main/vcf_to_hapmap/. Scripts and input files used for QTL mapping are available at: https://github.com/MarionCMueller. Other code is available through the Ubuntu software repositories.

References

Savary, S. et al. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 430–439 (2019).

Dodds, P. N. & Rathjen, J. P. Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant–pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 539–548 (2010).

Ngou, B. P. M., Ding, P. & Jones, J. D. G. Thirty years of resistance: zig-zag through the plant immune system. Plant Cell 34, 1447–1478 (2022).

Chen, R., Gajendiran, K. & Wulff, B. B. H. R we there yet? Advances in cloning resistance genes for engineering immunity in crop plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 77, 102489 (2024).

Sánchez-Martín, J. & Keller, B. NLR immune receptors and diverse types of non-NLR proteins control race-specific resistance in Triticeae. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 62, 102053 (2021).

Reveguk, T. et al. Tandem kinase proteins across the plant kingdom. Nat. Genet. 57, 254–262 (2025).

Chen, R. et al. A wheat tandem kinase activates an NLR to trigger immunity. Science 387, 1402–1408 (2025).

Lu, P. et al. A wheat tandem kinase and NLR pair confers resistance to multiple fungal pathogens. Science 387, 1418–1424 (2025).

Fu, D. et al. A kinase-START gene confers temperature-dependent resistance to wheat stripe rust. Science 323, 1357–1360 (2009).

Liu, Y., Hou, S. & Chen, S. Kinase fusion proteins: intracellular R-proteins in plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 29, 278–282 (2024).

Sánchez-Martín, J. et al. Wheat Pm4 resistance to powdery mildew is controlled by alternative splice variants encoding chimeric proteins. Nat. Plants 7, 327–341 (2021).

Asuke, S. et al. Evolution of wheat blast resistance gene Rmg8 accompanied by differentiation of variants recognizing the powdery mildew fungus. Nat. Plants 10, 971–983 (2024).

O’Hara, T. et al. The wheat powdery mildew resistance gene Pm4 also confers resistance to wheat blast. Nat. Plants 10, 984–993 (2024).

Anh, V. L. et al. Rmg8 and Rmg7, wheat genes for resistance to the wheat blast fungus, recognize the same avirulence gene AVR-Rmg8. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 1252–1256 (2018).

Lu, P. et al. A rare gain of function mutation in a wheat tandem kinase confers resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Commun. 11, 680 (2020).

Arora, S. et al. A wheat kinase and immune receptor form host-specificity barriers against the blast fungus. Nat. Plants 9, 385–392 (2023).

Sung, Y.-C. et al. Wheat tandem kinase RWT4 directly binds a fungal effector to activate defense. Nat. Genet. 57, 1238–1249 (2025).

Nirmala, J. et al. Concerted action of two avirulent spore effectors activates Reaction to Puccinia graminis 1 (Rpg1) - mediated cereal stem rust resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14676–14681 (2011).

Bourras, S. et al. Multiple avirulence loci and allele-specific effector recognition control the Pm3 race-specific resistance of wheat to powdery mildew. Plant Cell 27, 2991–3012 (2015).

Saur, I. M. L., Bauer, S., Lu, X. & Schulze-Lefert, P. A cell death assay in barley and wheat protoplasts for identification and validation of matching pathogen AVR effector and plant NLR immune receptors. Plant Methods 15, 118 (2019).

Kunz, L. et al. The broad use of the Pm8 resistance gene in wheat resulted in hypermutation of the AvrPm8 gene in the powdery mildew pathogen. BMC Biol. 21, 29 (2023).

Bernasconi, Z. et al. Mutagenesis of wheat powdery mildew reveals a single gene controlling both NLR and tandem kinase-mediated immunity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 37, 264–276 (2024).

Bilstein-Schloemer, M., Müller, M. C., Saur, I. M. L., Muller, M. C. & Saur, I. M. L. Technical advances drive the molecular understanding of effectors from wheat and barley powdery mildew fungi. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 38, 213–225 (2025).

Wu, C. H. & Derevnina, L. The battle within: how pathogen effectors suppress NLR-mediated immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 74, 102396 (2023).

Dodds, P. N., Lawrence, G. J., Catanzariti, A.-M., Ayliffe, M. A. & Ellis, J. G. The Melampsora lini AvrL567 avirulence genes are expressed in haustoria and their products are recognized inside plant cells. Plant Cell 16, 755–768 (2004).

Plissonneau, C. et al. A game of hide and seek between avirulence genes AvrLm4-7 and AvrLm3 in Leptosphaeria maculans. N. Phytol. 209, 1613–1624 (2016).

Bourras, S. et al. The AvrPm3–Pm3 effector–NLR interactions control both race-specific resistance and host-specificity of cereal mildews on wheat. Nat. Commun. 10, 2292 (2019).

Bourras, S., McNally, K. E., Müller, M. C., Wicker, T. & Keller, B. Avirulence genes in cereal powdery mildews: the gene-for-gene hypothesis 2.0. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 241 (2016).

Praz, C. R. et al. Non-parent of origin expression of numerous effector genes indicates a role of gene regulation in host adaption of the hybrid triticale powdery mildew pathogen. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 49 (2018).

Pedersen, C. et al. Structure and evolution of barley powdery mildew effector candidates. BMC Genom. 13, 694 (2012).

Burgess, A., Buck, M., Krauer, K. & Sculley, T. Nuclear localization of the Epstein–Barr virus EBNA3B protein. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 789–793 (2006).

Malik, S. & Roeder, R. G. The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 761–772 (2010).

Sotiropoulos, A. G. et al. Global genomic analyses of wheat powdery mildew reveal association of pathogen spread with historical human migration and trade. Nat. Commun. 13, 4315 (2022).

Müller, M. C. et al. A chromosome-scale genome assembly reveals a highly dynamic effector repertoire of wheat powdery mildew. N. Phytol. 221, 2176–2189 (2019).

Kloppe, T. et al. Two pathogen loci determine Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici virulence to wheat resistance gene Pm1a. N. Phytol. 238, 1546–1561 (2023).

Krauer, K. G. et al. Regulation of interleukin-1β transcription by Epstein–Barr virus involves a number of latent proteins via their interaction with RBP. Virology 252, 418–430 (1998).

Petit-Houdenot, Y. & Fudal, I. Complex interactions between fungal avirulence genes and their corresponding plant resistance genes and consequences for disease resistance management. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1072 (2017).

Inoue, Y., Vy, T. T. P., Tani, D. & Tosa, Y. Suppression of wheat blast resistance by an effector of Pyricularia oryzae is counteracted by a host specificity resistance gene in wheat. N. Phytol. 229, 488–500 (2021).

Xie, J. et al. A biGWAS strategy reveals the genetic architecture of the interaction between wheat and Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.04.09.647224 (2025).

Brabham, H. J. et al. Barley MLA3 recognizes the host-specificity effector Pwl2 from Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Cell 36, 447–470 (2024).

Parlange, F. et al. A major invasion of transposable elements accounts for the large size of the Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici genome. Funct. Integr. Genomics 11, 671–677 (2011).

Hewitt, T. et al. A highly differentiated region of wheat chromosome 7AL encodes a Pm1a immune receptor that recognizes its corresponding AvrPm1a effector from Blumeria graminis. N. Phytol. 229, 2812–2826 (2021).

Sánchez-Martín, J. et al. Rapid gene isolation in barley and wheat by mutant chromosome sequencing. Genome Biol. 17, 221 (2016).

Brunner, S. et al. Intragenic allele pyramiding combines different specificities of wheat Pm3 resistance alleles. Plant J. 64, 433–445 (2010).

Koller, T. et al. Field grown transgenic Pm3e wheat lines show powdery mildew resistance and no fitness costs associated with high transgene expression. Transgenic Res. 28, 9–20 (2019).

Hurni, S. et al. Rye Pm8 and wheat Pm3 are orthologous genes and show evolutionary conservation of resistance function against powdery mildew. Plant J. 76, 957–969 (2013).

Singh, S. P. et al. Evolutionary divergence of the rye Pm17 and Pm8 resistance genes reveals ancient diversity. Plant Mol. Biol. 98, 249–260 (2018).

Arora, S. et al. Resistance gene cloning from a wild crop relative by sequence capture and association genetics. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 139–143 (2019).