Abstract

The relationship between epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) and midlife cognitive function remains unclear, with limited causal evidence. We investigated this association in 1252 Black and White middle-aged adults from the Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS) and conducted a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using GWAS summary statistics for EAA (N = 34,710) and cognition (N ≤ 106,162). In BHS, higher Hannum age acceleration, PhenoAge acceleration, and GrimAge acceleration (GrimAA) were each associated with slower processing speed (p < 0.05). Additionally, GrimAA was linked to lower global cognition scores (p < 0.001), independent of covariates. MR analysis suggested a potential link, showing that genetically predicted GrimAA was nominally associated with slower processing speed (p = 0.05). These findings suggest that epigenetic aging, particularly GrimAA, is independently associated with lower cognitive function in midlife and may play an important role in cognitive impairment, especially in processing speed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global population ages, it is projected that more than 150 million adults will live with dementia by 2050, posing substantial burdens to affected individuals, family members, and health care infrastructures1,2. Despite recent advances3, effective treatment options are still limited. In contrast, over 40% of dementia cases are potentially preventable through interventions of modifiable risk factors2. Preclinical cognitive changes are known to occur decades before the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementias4,5, with recent reports demonstrating strong, independent associations between midlife cognitive function and later-life dementia6. The long prodromal phase of dementias represents a critical time window when disease may be more effectively prevented or delayed7,8,9. While reports have highlighted the importance of identifying early biomarkers for cognitive impairment and dementias2,10, molecular precursors or markers that might be measurable by midlife have not been fully characterized4,5.

Epigenetic changes are independent to genetic alterations and potentially reversible determinants of aging11 and age-related conditions, including cognitive impairment and dementia susceptibility12,13. DNA methylation-based age, or epigenetic clock age, may be among the most accurate measures of aging14,15. Interestingly, deviation of epigenetic clock age from chronological age, termed epigenetic age acceleration (EAA), has also been identified as a powerful marker of chronic diseases16,17,18,19. Several EAA phenotypes have been widely studied over the past decade in relation to health and disease16,20. These include first-generation measures such as intrinsic EAA (IEAA), which is derived from the ‘pan-tissue’ Horvath epigenetic clock21 and reflects multi-tissue aging, as well as Hannum age acceleration (HannumAA)18, which captures aging in blood and immune cells. Second-generation EAA measures, namely PhenoAge acceleration (PhenoAA)22 and GrimAge acceleration (GrimAA)23 were developed to model aging in relation to chronic disease, multi-morbidity and mortality, respectively. Numerous epidemiologic studies have recently revealed associations of EAA with both cognitive decline and increased risks of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (AD/ADRD) in older adults24,25,26,27,28, suggesting potential utility in patient stratification and precision intervention. However, relatively few studies have focused on the EAA-cognition relationship in midlife. Aside from two reports29,30, most findings have been derived from small studies and findings have been conflicting31,32,33,34,35. Further, there is a dearth of causal evidence elucidating the role of EAA in cognitive impairment.

The current study assessed whether blood-derived EAA measures were associated with cognition in midlife by leveraging simultaneously measures of EAA and cognitive function among 1252 middle-aged participants (433 Black participants; 740 female participants; Supplementary Fig. S1) from the Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS). Additionally, the causal relationship between EAA and midlife cognitive function was investigated using genetic information from large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) utilizing a Mendelian Randomization (MR) framework. The study design is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results

Characteristics of BHS participants

Characteristics of the 1252 BHS participants with available cognitive function and methylation measures are shown in Table 1. The mean age of study participants was 48, 35% were Black participants, and 59% were female. Approximately half had at least a high-school education (49%) and were current drinkers (56%). Most BHS participants were non-smokers (81%]) and showed no evidence of depression (90%). On average, participants were obese, prediabetic, and had modestly elevated systolic BP and LDL-C values. In concurrence with previous observations, female participants were biologically younger (lower EAA)33.

Association of EAA and midlife cognitive function in BHS participants

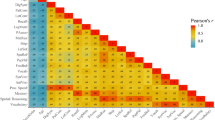

Findings from our main analyses are presented in Fig. 2. After adjusting for demographics, behavioral and clinical covariates (Model 3), increased HannumAA, GrimAA and PhenoAA were nominally or significantly associated with slower attention and processing speed (HannumAA, β = −0.049, 95% CI, −0.097 to −0.001; PhenoAA, β = −0.072, 95% CI, −0.121 to −0.023; GrimAA, β = −0.147, 95% CI, −0.211 to −0.083). In addition, greater GrimAA was strongly associated with lower global cognition score (β = −0.095, 95% CI, −0.151 to −0.039) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). In Model 1, nominal associations were also found between these three EAA measures and individual neurocognitive tests (Supplementary Fig. S2). No association was identified between IEAA and cognitive domains.

Forest plots show cross-sectional associations between midlife EAA and cognitive domain scores and a global cognition score. There are three cognitive domains, included, namely attention and processing speed, episodic memory, and working memory. A higher score indicates higher cognitive function. All cognition scores were normalized and effects of EAA were standardized.

Associations between categorized EAA tertile and cognitive domains were generally consistent with analyses examining the continuous EAA measures (Table 2). For example, in Model 1, compared to the first tertile, the last tertile of HannumAA, PhenoAA and GrimAA were associated with decreased attention and processing speed (P = 0.010, <0.001, and <0.001, for linear trend, respectively). Likewise, the last tertile of GrimAA was associated with decreased global cognition score (P < 0.001 for linear trend). As shown in a sensitivity analysis, APOE status did not affect these identified associations (Supplementary Table S1). Linear regression model fit and assumptions were systematically evaluated, revealing no evidence of heteroskedasticity, non-linearity, or other violations that would compromise the validity of our findings. Diagnostic plots, restricted cubic spline analyses, and results from heteroskedasticity tests and robust regression (Supplementary Figs. S3, S4, Supplementary Table S2) all support the validity of the linear models used in the current study.

Race and sex-stratified associations between EAA and midlife cognitive function in BHS participants

Stratified analyses were performed to discern sex and race-specific associations between EAA and cognitive function, as shown in Supplementary Figs. S5–S8. Estimated effects of the stratified analysis concurred with the combined analysis (Supplementary Table S3). While no interactions were detected at the cognitive domain level, stratified analysis identified associations of GrimAA and PhenoAA with TMT Part B performance were modified by sex (P for interaction = 0.02 and 0.004, respectively), independent of known risk factors (Supplementary Table S4). In female participants, each SD increase in GrimAA or PhenoAA was associated with worse performance of TMT Part B (i.e., a higher score) (GrimAA: 0.151, 95% CI 0.052–0.249; PhenoAA: 0.065, 95% CI −0.006 to 0.136), an association which was not observed in males. No significant race interactions were identified.

Causal estimates of genetically predicted EAA and cognitive function

In the 2-sample MR analysis, nominally significant associations between genetically predicted EAA and cognitive tests are presented in Table 3. Each 1-year higher genetic predisposition to GrimAA was associated with worse performance of TMT part A test among 99479 participants of European ancestry from the UK Biobank (β = 0.024, 95% CI, 0–0.049), but not associated with TMT part B or numeric memory test. Sensitivity analyses using multiple pleiotropy-robust methods showed generally consistent effect sizes compared with the primary IVW method. No causal associations were identified for HannumAA and PhenoAA (Supplementary Table S5), both of which showed associations with midlife cognition in our cross-sectional analysis. No association remained significant after accounting for multiple testing.

Discussion

This study investigated cross-sectional associations between EAA and cognition-related phenotypes using a racially diverse cohort of middle-aged participants from the BHS, and leveraged MR study to further support causal inference. Cross-sectional analyses revealed that increased HannumAA, PhenoAA and GrimAA were associated with lower cognitive function in midlife, independent of demographic, educational, behavioral, and major clinical and cardiometabolic risk factors. Among the EAA measures that associated with lower midlife cognition, MR analyses supported a potentially causal association of GrimAA with worse performance in TMT part A, a test reflecting processing speed. In aggregate, these findings support a potentially important relation between EAA and cognition and suggest that EAA-related decreases in cognitive function may be evident by middle age.

Associations between GrimAA and cognition were jointly supported by our observational and genomic studies. Furthermore, we report early evidence of a female-specific association between higher GrimAA and worse performance in TMT Part B, which aligns with a report of GrimAA mediating sex-specific cognitive aging in an older population36. In general, per standard deviation effect sizes for GrimAA measures were larger in magnitude than those identified for the other EAA measures. Like in our study, GrimAA has outperformed ‘first-generation’ EAA measures and PhenoAA in the prediction of decreased cognition in several previous reports25,27,28,29,35,37. One explanation is that GrimAA includes the highest number of cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites among the four common EAA measures, and is built to capture key aging and inflammatory biomarkers, which may be involved in cognitive aging processes23,29. Our MR analysis bolsters the link between GrimAA and midlife cognitive impairment, showing some of the first evidence that genetic liability of GrimAA may relate to slower processing speed, measured by TMT Part A. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution given the weak genetic instrument for GrimAA38 and nominal significance observed. Moreover, the relatively weak genetic instrument makes it difficult to discern if null findings for TMT Part B or numeric memory reflect low statistical power or true lack of association. Overall, our data suggests a potentially important role for GrimAA in midlife cognition.

PhenoAA was consistently associated with reduced attention and processing speed in midlife across all observational models, but this was not supported by our MR analysis. Among the limited studies examining this molecular phenotype for a relation with cognition phenotypes, a recent study reported similar findings, identifying a significant association between PhenoAA and processing speed, measured using the letter cancellation test, in a meta-analysis of 1602 adults 45–87 years of age37. The discrepancy between our observational and MR findings may reflect a non-causal relationship or insufficient power in the MR analysis. Further research is needed to clarify this association.

Higher HannumAA was associated with lower attention and processing speed in midlife but was not supported by our MR analysis. Similar to our results, a recent cross-sectional study limited to the assessment of ‘first-generation’ EAA identified an association between HannumAA with cognition in 2157 middle-aged Black participants, with replication in over 1600 White participants30. Likewise, a small longitudinal study recently reported associations between higher extrinsic EAA (EEAA), a slightly modified version of HannumAA, and faster declines in visual memory and attention/processing speed33. While the biological mechanisms underlying this relationship have not been completely elucidated, HannumAA has been temporally associated with accelerated blood cell aging and immunosenescence15,38, biological processes strongly implicated in cognitive decline39,40. However, our MR study did not support the role of HannumAA in cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, our study adds to the accumulating evidence implicating HannumAA as a biomarker of lower cognitive function.

In contrast, IEAA, another ‘first-generation’ EAA measure, showed no associations with cognitive function in midlife or with genetically predicted cognition. This aligns with most studies of midlife cognition29,30,31,33,35. Two smaller studies did report memory decline linked to IEAA over 10 years, but differences in populations, predominantly white or male in these small cohorts, may explain the discrepancy32,34. While the IEAA-cognition association was observed among elderly populations, genetic analyses, including our MR and prior genetic correlation studies, suggest IEAA is not a causal factor in midlife cognitive function 41.

As a large study investigating all four major EAA measures and midlife cognition29,30, our study was well-powered to detect important but modest effects of these measures on cognitive function. The large and diverse sample of men and women participating in the BHS enabled investigation into these associations according to race and sex groups, an examination that has been rarely conducted31,32,33,34,35. Additional strengths include the use of the deeply-phenotyped BHS cohort, with data from a large battery of cognitive tests allowing us to examine global cognitive function and multiple cognitive domains. Moreover, the use of MR analyses provided a unique method to help support temporality and potential causal relations with cognitive function, which is not possible in cross-sectional analyses.

Although we tried to shed light on temporality and causality through MR analyses, our findings are only nominally significant, and our null results in our MR studies do not rule out potential causals associations of EAA measures with decreased cognition. Our genetic instrument for EAA was weak38, with larger MR studies or longitudinal analyses needed to better articulate the relationship between EAA and cognitive impairment over time. While some SNPs selected as instruments are associated with blood traits, this reflects the biological basis of EAA and does not violate MR assumptions, as blood traits are not established risk factors for cognitive decline42 and are unlikely to violate the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) assumption43. Except for IEAA, a pan-tissue epigenetic clock, all other EAA measures were derived from blood, which may not reflect EAA values in cognition related brain tissue44,45. Despite leveraging a diverse sample of Black and White participants for cross-sectional analyses, there were a lack of GWAS studies conducted in diverse samples, which limited the generalizability of our MR analyses beyond predominantly white populations. These preliminary results are hypothesis-generating and warrant replication using GWAS data from larger and more diverse populations.

This observational and Mendelian randomization study found that EAA measures, particularly GrimAA, were associated with impairment in processing speed or global cognition in midlife. These findings suggest that epigenetic aging may influence midlife cognitive decline, serving as potential early indicators of future impairment. Further studies are needed to explore their role in dementia risk.

Methods

Study design

We examined cross-sectional associations between EAA measures and cognitive function in midlife within the BHS cohort, followed by MR analysis to help infer a causal role of EAA in midlife cognitive impairment (Fig. 1). Cross-sectional associations were tested in 1252 BHS participants with EAA and cognitive data from the 2013–2016 study visit. A 2-sample MR analysis used recent large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analyses of EAA measures (n = 34,710 individuals of European-ancestry)38 and cognitive function (up to 106,162 UK Biobank participants)46,47,48.

Bogalusa Heart Study population

The Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS) is a long-term, community-based study of cardiovascular disease among a racially diverse cohort from Bogalusa, Louisiana. The core cohort is comprised of 1298 middle-aged participants born between 1959 and 1979. During the 2013 to 2016 study visit, BHS cohort participants underwent epigenetics profiling and cognitive assessments. After excluding those missing cognition (N = 20) or DNA methylation data (N = 29), 1252 participants (mean age 48.2 years, 34.6% Black) were included in the current cross-sectional analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Measurement of epigenetic age acceleration in the BHS

Genome-wide epigenetic profiling was performed using whole blood drawn during the 2013–2016 BHS visit cycle, as described previously49. Briefly, BHS samples were processed at the Microarray Core Facility, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Texas, US49. Genomic DNA was first extracted from whole blood samples using the PureLink Pro 96 Genomic DNA Kit (LifeTechnology, CA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. DNA methylation was measured using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina, CA). The generated raw IDAT files were further processed by the Methylation Module in the GenomeStudio (Illumina, CA). The default normalization method was used by GenomeStudio to generate a final report of beta estimates at each CpG site.

The DNA methylation measures were then normalized and uploaded to Horvath’s DNA methylation age calculator available at https://dnamage.genetics.ucla.edu/new. Four measures of EAA, which correspond to EAA measures also available for MR study, namely, IEAA, HannumAA, PhenoAA, and GrimAA, were extracted from the generated output. To adjust for batch effects, an additional normalization step was performed internally within the Horvath’s DNA methylation age estimation algorithm. This normalization step was a modified version of the beta mixture quantile dilation (BMIQ) normalization method50, specifically designed for Horvath’s epigenetic age calculator. This method aligns user-inputted methylation data with gold standard methylation data, allowing a robust batch effect adjustment (available at https://horvath.genetics.ucla.edu/html/dnamage/faq.htm).

Measurement of cognition in the BHS

In accordance with the latest recommendations from the NIH toolbox51, the BHS participants underwent evaluations of four cognitive domains, i.e., attention and processing speed, verbal episodic memory, working memory and language. Trained technicians conducted a battery of eight standard tests (10 measurements). Attention and processing speed were assessed with the Digit Symbol Coding subtest (WAIS-IV), and Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A and B; episodic memory were assessed with the Logical Memory I and II and Recognition (WMS-IV) for short- and long term narrative memory under a free recall condition, and delayed recognition; working memory were assessed with the Digit Span Task forwards and backwards (WAIS-IV); and language were assessed with the Word and Letter Reading (Wide Range Achievement Test [WRAT] 4th edition) and Vocabulary (WAIS-IV). Higher scores indicated better performance on most tests, except for the TMT, where lower scores indicated better cognition.

To normalize the distribution of each cognitive test score, crude scores underwent a rank-based inverse normal transformation. Four domain-specific scores and the global cognitive score (GCS) were estimated by averaging Z-score transformed crude scores from the corresponding cognitive tests (see Supplementary Fig. S2). TMT scores were flipped so that higher scores reflect better performance. Both domain scores and GCS were subjected to the same normalization approach as the individual cognitive tests scores.

Measurement of study covariables in the BHS

Covariables were collected following stringent protocols, which have been used consistently at each BHS study visit and described in detail elsewhere52. Briefly, information on demographic characteristics (including age, sex, race, and education) and lifestyle risk factors (including cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption) were obtained by administered questionnaires. Depression was evaluated using the CES-D instrument53,54. Clinical covariables, including body mass index (BMI), blood pressures (BP), serum lipids, and blood hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), were measured by trained staff. Briefly, information on demographic characteristics (including age, sex, race, and education) and lifestyle risk factors (including cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption) were obtained by administered questionnaires. Depression was evaluated using the CES-D instrument53,54. Anthropometric measures were collected by trained staff with participants in light clothing without shoes. At each visit, body weight and height were measured twice to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was estimated using the mean values of weight and height, as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters squared). Blood pressure (BP) level was measured in the morning in triplicate by a trained staff using the OMRON HEM-907 XL digital BP monitor (Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) with the participant in a relaxed, sitting position. The mean of the three BP values were used to estimate BP. Participants were instructed to fast for 12 h prior to the blood sample collection. Serum lipids, including total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride (TG) levels were assayed using an enzymatic procedure as part of a lipid panel (Laboratory Corporation of America, Burlington, NC, USA). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated following the Friedewald equation (LDL-C = TC − HDL-C − TG/5) for those with TG less than 400 mg/dl55. Blood hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured by turbidimetric immunoinhibition assay on a Hitachi 902 Automatic Analyzer (Tina-quant, Roche Diagnostics)56. APOE genotype information was available in a subset of the BHS participants (n = 653) who underwent genome-wide genotyping using the Illumina Human610-Quad array57.

Achieved education and premorbid cognitive abilities (before examination or before the onset of any brain dysfunction) were estimated by a language index (i.e., language cognitive domain score). This is because social determinants affect the quality of education and are not fully reflected by the education measurement using grade-level cutoff58,59. Evidence from the BHS and others support the use of indicators of achieved education for more accurate comparisons involving traditionally marginalized racial groups58,59,60,61.

Statistical analysis

Multiple linear regression analyses were employed to examine cross-sectional associations of EAA with cognitive function measures in midlife. Three multivariable models were used, model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, and achieved education; model 2 adjusted for covariables in model 1, and additionally adjusted for smoking status, alcohol consumption, and depression; and model 3 adjusted for covariables in model 2, and additionally adjusted for systolic blood pressure, LDL-C, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), BMI, log-transformed white blood cell counts, and BP, lipid, and glucose lowering medications. A conservative Bonferroni correction was applied to account for the number of EAA-cognitive domain tests (α = 0.05/12 = 4.16 × 10−3). Original P values are displayed in tables and figures throughout this study with footnotes indicating their significance after the Bonferroni correction. For association of EAA and individual neurocognitive tests, a conservative Bonferroni correction was applied to account for the number of EAA-neurocognition tests (Bonferroni α = 0.05/32 = 1.56 × 10−3). The associations of categorized EAA tertiles with cognitive domains were also tested to assess dose-response relations. Tests of linear trend were calculated by assigning the median of each tertile to each participant in the tertile. Sex and race stratified analyses were conducted. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of APOE genotype on associations between EAA and cognition.

We assessed the validity of linear regression assumptions using multiple approaches in the BHS cohort analysis across all models examining associations between EAA and cognitive function scores. Model diagnostics included residual vs. fitted plots and Q–Q plots to visually inspect linearity and the distribution of residuals. Heteroskedasticity was formally tested using the studentized Breusch–Pagan test62, as implemented in lmtest R package. Robust regression analyses were conducted using MM-estimation63, as implemented in the robustbase R package, to evaluate the robustness of findings to potential model violations. Non-linearity was assessed using restricted cubic splines with three knots in fully adjusted models, as implemented in splines and rms R packages. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare models containing only a linear term with those including both linear and spline terms. If the spline model did not significantly improve model fit, a secondary test was conducted by comparing the full model (including the linear term and covariates) to a covariate-only model.

2-sample Mendelian randomization

Selection of genetic instruments

Genetic instruments for the four distinct EAA measures, i.e., IEAA, HannumAA, PhenoAA, and GrimAA, were derived from a recent GWAS meta-analysis of epigenetic aging38 (n = 34710 ancestrally European participants). Briefly, genetic instruments for each EAA variable were comprised of independent SNPs (500-kb window, r2 < 0.01) that achieved genome-wide significant associations (P = 5 × 10−8) with EAA in GWAS meta-analysis, with exclusion of SNPs robustly associated with hypertension, blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, cholesterol-lowering medications, BMI, obesity, and smoking (described in detail in the below section). Among SNPs selected for the EAA genetic instruments, no ambiguous and non-inferable palindromic SNPs were found. Steiger filtering64, a procedure that removes SNPs failing to explain significantly more variance in the exposure than the outcome after comparing their effect sizes, was performed to confirm the directionality of instrument SNPs. Summary statistics for individual genetic instruments are presented in Supplementary Tables S6–S9, with effect sizes aligned toward “increasing” EAA.

Excluding SNPs associated with potential confounders for EAA instruments

Genetic instruments for each EAA variable were comprised of independent SNPs associated with EAA in GWAS meta-analysis, with exclusion of SNPs associated with potential confounders. These confounders include hypertension, blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, cholesterol-lowering medications, body mass index (BMI), obesity, and smoking. To implement such filter, summary statistics of GWAS analysis results of corresponding traits based on UK Biobank were retrieved from an external resource available at https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/data/ukb_fastgwa/imp/. EAA index SNPs that had a genome-wide significant association (P = 5 × 10−8) with potential confounders were removed. This external GWAS was conducted using fastGWA65, and adjusted for age, sex, and the first 10 genetic principal components within the individual-level UK Biobank data.

Outcome data for the two-sample MR

Summary statistics of midlife cognitive function were obtained from large-scale GWAS in the UK Biobank participants of European ancestry (N ≤ 106,162)46,47,48. Cognitive assessments in the UK Biobank were administered via automated touchscreen or web-based questionnaires46,48. While the test battery is non-standard, it has evaluated for validity and reliability with standard cognitive tests66, including some used in the current study. Three cognitive tests, namely UKB Numeric Memory, UKB TMT part A, and TMT part B (UK Biobank Data-Fields 20240, 20156, 20157), were selected for MR analysis, corresponding closely to the cognitive tests used in the BHS analysis. Specifically, UKB Numeric Memory strongly correlated with the Digit Span Task (WAIS-IV), while UKB TMT Parts A and B correlated with the paper-and-pencil TMT tests66. GWAS summary statistics were retrieved via the MRC IEU OpenGWAS, which applied rank-based inverse normal transformation to the TMT tests and treated Numeric Memory results as ordered categorical data for the GWAS analysis67,68. There is no sample overlap between the GWAS meta-analysis of EAA and UK Biobank cognition data.

MR analysis framework

We applied the Rücker model-selection framework for MR analysis69,70. Briefly, the multiplicative random-effects inverse variance–weighted (IVW) method was used as the primary MR approach in the absence of significant horizontal pleiotropic effect. The IVW method has the best power when all SNPs are valid instrumental variables71. The MR-Egger method was used as the primary method when horizontal pleiotropy was detected and the MR-Egger43 demonstrated better fit than IVW. Model selection was based on a significant difference (P < 0.05) between Cochran’s Q statistic for the IVW method and Rücker’s Q’ for the MR-Egger method (with respect to a \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) distribution), along with a significant non-zero MR-Egger intercept (P < 0.1)69,70. Using this framework, a multiplicative random-effects inverse variance–weighted (IVW) method was used as the primary MR approach in the absence of significant horizontal pleiotropic effect. When horizontal pleiotropy was detected, the MR-Egger method was utilized as the primary MR approach. Results from the Steiger test64 for directionality were reported to further indicate whether assumed directionality was valid. We also employed additional methods that partially relax MR assumptions, including weighted median72 and weighted mode73, as sensitivity analyses to assess causality in the presence of unbalanced pleiotropy74. MR analyses were performed by the TwoSampleMR75 package in R. Multiple testing correction was applied, and no associations met the threshold for statistical significance after adjustment. P-values reported for MR analyses are unadjusted for multiple comparisons.

Pleiotropy-robust sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses using various MR methods to explore the validity of ‘independence’ and ‘exclusion-restriction’ assumptions in our primary MR analyses, which is a recommended practice for MR studies74. Methods including MR-Egger43, weighted median72 and weighted mode73 were all employed. In brief, MR-Egger43 regression is considered a pleiotropy-robust method that estimates and adjusts for an overall pleiotropic effect on all SNVs. The Egger intercept was also used in the Rücker framework69 for model section of our primary MR approach in this study. MR-Egger provides consistent estimates of the causal effect under the InSIDE assumption, which requires that pleiotropic effects of genetic variants be uncorrelated with the genetic variant–exposure association. Weighted median72 is robust to pleiotropy by relaxing the requirement of valid instrumental SNPs. This method produces consistent estimates when the majority, or more than half of the instrumental SNPs are valid. Weighted mode, using the mode-based estimate, can also obtain causal effect estimate robust to horizontal pleiotropy and is proposed to use in combination with other methods in sensitivity analysis 73.

Data availability

The present study utilized publicly available data of GWAS summary statistics for the MR analysis: GWAS Catalog ID GCST90014001-GCST90015000 for EAA GWAS, IEU OpenGWAS ukb-b-18683, ukb-b-16026, ukb-b-20140 for UK Biobank cognitive function GWAS. De-identified data from BHS is available by request. Further details and data not presented in the article can be shared upon request.

References

Nichols, E. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7, e105–e125 (2022).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396, 413–446 (2020).

van Dyck, C. H. et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA2212948/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA2212948_DATA-SHARING.PDF (2022).

Mortamais, M. et al. Detecting cognitive changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: areview of its feasibility. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 468–492 (2017).

Rajan, K. B., Wilson, R. S., Weuve, J., Barnes, L. L. & Evans, D. A. Cognitive impairment 18 years before clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology 85, 898–904 (2015).

Knopman, D. S. et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and midlife cognitive status in relation to prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in later life: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1406–1415 (2018).

Barnett, J. H., Lewis, L., Blackwell, A. D. & Taylor, M. Early intervention in Alzheimer’s disease: a health economic study of the effects of diagnostic timing. BMC Neurol. 14, 1–9 (2014).

Gandy, S., Bartfai, T., Lees, G. V. & Sano, M. Midlife interventions are critical in prevention, delay, or improvement of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. F1000Res. 6, 413 (2017).

Rebok, G. W. et al. Ten-year effects of the ACTIVE cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62, 16 (2014).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 390, 2673–2734 (2017).

Yang, J.-H. et al. Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging. Cell 186, 305–326.e27 (2023).

Nativio, R. et al. Dysregulation of the epigenetic landscape of normal aging in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci.21, 497–505 (2018).

Marioni, R. E. et al. Meta-analysis of epigenome-wide association studies of cognitive abilities. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 2133–2144 (2018).

Jylhävä, J., Pedersen, N. L. & Hägg, S. Biological age predictors. EBioMedicine 21, 29–36 (2017).

Marioni, R. E. et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 16, 25 (2015).

Horvath, S. & Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 371–384 (2018).

Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, R115 (2013).

Hannum, G. et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 49, 359–367 (2013).

Horvath, S. et al. An epigenetic clock analysis of race/ethnicity, sex, and coronary heart disease. Genome Biol. 17, 171 (2016).

Simpson, D. J. & Chandra, T. Epigenetic age prediction. Aging Cell 20, e13452 (2021).

Lowe, D., Horvath, S. & Raj, K. Epigenetic clock analyses of cellular senescence and ageing. Oncotarget 7, 8524–8531 (2016).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 10, 573–591 (2018).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 11, 303–327 (2019).

Sugden, K. et al. Association of pace of aging measured by blood-based DNA methylation with age-related cognitive impairment and dementia. Neurology 99, E1402–E1413 (2022).

Jain, P. et al. Analysis of epigenetic age acceleration and healthy longevity among older US women. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2223285–e2223285 (2022).

Shadyab, A. H. et al. Association of epigenetic age acceleration with incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia among older women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 77, 1239–1244 (2022).

Hillary, R. F. et al. An epigenetic predictor of death captures multi-modal measures of brain health. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3806–3816 (2021).

McCrory, C. et al. GrimAge outperforms other epigenetic clocks in the prediction of age-related clinical phenotypes and all-cause mortality. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 741–749 (2021).

Zheng, Y. et al. Mid-life epigenetic age, neuroimaging brain age, and cognitive function: coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Aging 14, 1691–1712 (2022).

Bressler, J. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and cognitive function in African American adults in Midlife: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 473–480 (2020).

Starnawska, A. et al. Blood DNA methylation age is not associated with cognitive functioning in middle-aged monozygotic twins. Neurobiol. Aging 50, 60–63 (2017).

Degerman, S. et al. Maintained memory in aging is associated with young epigenetic age. Neurobiol. Aging 55, 167–171 (2017).

Beydoun, M. A. et al. Accelerated epigenetic age and cognitive decline among urban-dwelling adults. Neurology 94, e613–e625 (2020).

Vaccarino, V. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and cognitive decline: a Twin study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 1854 (2021).

Reed, R. G., Carroll, J. E., Marsland, A. L. & Manuck, S. B. DNA methylation-based measures of biological aging and cognitive decline over 16-years: preliminary longitudinal findings in midlife. Aging14, 9423 (2022).

O’shea, D. M., Maynard, T. & Tremont, G. DNA methylation “GrimAge” acceleration mediates sex/gender differences in verbal memory and processing speed: findings from the health and retirement study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 77, 2402 (2022).

Maddock, J. et al. DNA methylation age and physical and cognitive aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 504 (2020).

McCartney, D. L. et al. Genome-wide association studies identify 137 genetic loci for DNA methylation biomarkers of aging. Genome Biol. 22, 1–25 (2021).

Solana, C., Tarazona, R. & Solana, R. Immunosenescence of natural killer cells, inflammation, and Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 3128758 (2018).

Bektas, A., Schurman, S. H., Sen, R. & Ferrucci, L. Human T cell immunosenescence and inflammation in aging. J. Leukoc. Biol. 102, 977 (2017).

Liu, H., Lutz, M. & Luo, S. Genetic association between epigenetic aging-acceleration and the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 77, 1734–1742 (2022).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 404, 572–628 (2024).

Bowden, J., Smith, G. D. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525 (2015).

Hannon, E., Lunnon, K., Schalkwyk, L. & Mill, J. Interindividual methylomic variation across blood, cortex, and cerebellum: implications for epigenetic studies of neurological and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Epigenetics 10, 1024–1032 (2015).

Levine, M. E., Lu, A. T., Bennett, D. A. & Horvath, S. Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging 7, 1198–1211 (2015).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature562, 203–209 (2018).

Lyall, D. M. et al. Cognitive test scores in UK biobank: data reduction in 480,416 participants and longitudinal stability in 20,346 participants. PLoS One 11, e0154222 (2016).

Sun, D. et al. Body mass index drives changes in DNA methylation: a longitudinal study. Circ. Res. 125, 824–833 (2019).

Teschendorff, A. E. et al. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics 29, 189–196 (2013).

Gershon, R. C. et al. Assessment of neurological and behavioural function: the NIH Toolbox. Lancet Neurol. 9, 138–139 (2010).

Foster, T. A. & Berenson, G. S. Measurement error and reliability in four pediatric cross-sectional surveys of cardiovascular disease risk factor variables-the Bogalusa Heart Study. J. Chronic Dis. 40, 13–21 (1987).

Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., Roberts, R. E. & Allen, N. B. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol. Aging 12, 277–287 (1997).

Herniman, S. E., Allott, K. A., Killackey, E., Hester, R. & Cotton, S. M. The psychometric validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D) in first episode schizophrenia spectrum. Psychiatry Res. 252, 16–22 (2017).

Friedewald, W. T., Levy, R. I. & Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18, 499–502 (1972).

Nguyen, Q. M., Srinivasan, S. R., Xu, J. H., Chen, W. & Berenson, G. S. Distribution and cardiovascular risk correlates of hemoglobin A1c in nondiabetic younger adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Metabolism 57, 1487–1492 (2008).

Vuoksimaa, E., Palviainen, T., Lindgren, N., Rinne, J. O. & Kaprio, J. Accuracy of imputation for apolipoprotein E ε alleles in genome-wide genotyping data. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e1919960–e1919960 (2020).

Manly, J. J., Jacobs, D. M., Touradji, P., Small, S. A. & Stern, Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 8, 341–348 (2002).

Ahl, R. E. et al. Defining MCI in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring: Education vs. WRAT-based norms. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 27, 330–336 (2013).

Sisco, S. et al. The role of early-life educational quality and literacy in explaining racial disparities in cognition in late life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 70, 557 (2015).

De Anda-Duran, I. et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and midlife cognitive function: impact of race and social disparities in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Neurology 98, E1828–E1836 (2022).

Breusch, T. S. & Pagan, A. R. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 47, 1287 (1979).

Koller, M. & Stahel, W. A. Sharpening Wald-type inference in robust regression for small samples. Comput Stat. Data Anal. 55, 2504–2515 (2011).

Hemani, G., Tilling, K. & Davey Smith, G. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. PLoS Genet. 13, e1007081 (2017).

Jiang, L. et al. A resource-efficient tool for mixed model association analysis of large-scale data. Nat. Genet.51, 1749–1755 (2019).

Fawns-Ritchie, C. & Deary, I. J. Reliability and validity of the UK Biobank cognitive tests. PLoS One 15, e0231627 (2020).

Elsworth, B. et al. The MRC IEU OpenGWAS data infrastructure. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.10.244293 (2020).

Millard, L. A. C., Davies, N. M., Gaunt, T. R., Smith, G. D. & Tilling, K. Software Application Profile: PHESANT: a tool for performing automated phenome scans in UK Biobank. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 29–35 (2018).

Rücker, G., Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R., Binder, H. & Schumacher, M. Treatment-effect estimates adjusted for small-study effects via a limit meta-analysis. Biostatistics 12, 122–142 (2011).

Bowden, J. et al. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat. Med. 36, 1783 (2017).

Lin, Z., Deng, Y. & Pan, W. Combining the strengths of inverse-variance weighting and Egger regression in Mendelian randomization using a mixture of regressions model. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009922 (2021).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 40, 304 (2016).

Hartwig, F. P., Smith, G. D. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1985–1998 (2017).

Burgess, S. et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations. Wellcome Open Res.4, 186 (2019).

Hemani, G. et al. The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 7, e34408 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the following NIH under award numbers: R01AG041200 and R33AG057983 for Dr. Bazzano, R01AG062309 for Dr. Bazzano, and Dr. Carmichael, R01AG077000 for Dr. Kelly, Dr. Bazzano, and Dr. Carmichael, P20GM109036 for Dr. Kelly, P30AG72975, R01AG15819, R01AG17917 and U01AG61356 for Dr. Bennett, R35AG071916 and R01AG063887 for Dr. Yaffe, and K99AG083214 for Dr. Pan. We are grateful for the contribution of all staff members who were involved in conducting and managing the Bogalusa Heart Study. We extend our gratitude to the participants of the Bogalusa Heart Study, many of whom have participated since they were children. GWAS summary statistics were contributed by IEU OpenGWAS project. The authors thank all investigators for providing the data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P. and Z.H. conducted the analysis, interpreted the findings, and wrote the first draft of the article. X.S., I.D.A.-D., W.C. and L.A.B. contributed the BHS methylation data and cognitive function data. R.Z., C.L., A.W.C., K.Y., J.Z. D.A.B. and O.T.C. helped with the cognition data analysis and interpretation and edited the manuscript; T.N.K. conceived of the study, provided the resource, and edited the article. All authors helped interpret the data and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consents were obtained from all the BHS participants after detailed explanation of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Tulane University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Y., Huang, Z., Sun, X. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and midlife cognition: joint evidence from observational study and Mendelian randomization. npj Aging 11, 75 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00265-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00265-6