Abstract

Menopause-related metabolic remodeling may contribute to the excess cardiovascular disease (CVD) burden in aging women, yet the longitudinal metabolic correlates of time since menopause (TSM) and their prognostic value are unclear. In this prospective analysis of 67,582 postmenopausal women without baseline CVD from the UK Biobank, we profiled 251 plasma metabolites by nuclear magnetic resonance and followed participants for a median 13.7 years (8313 incident CVD events). Elastic net regression identified a 95‑metabolite TSM-associated metabolomic signature (Spearman r with TSM = 0.29). In multivariable Cox models, each 5-year increment in TSM (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.16) and each 1–standard deviation increases in the metabolomic signature (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.15–1.21) were independently associated with higher composite CVD risk, with consistent associations across myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure and stroke. Mendelian randomization supported potential causal roles for 29 of the signature metabolites in CVD. Adding TSM or the metabolomic signature to SCORE2 improved 10‑year risk discrimination (area under the curve 0.584 to 0.657 and 0.660, respectively) and reclassification (net reclassification improvement +0.027 and +1.043). These findings implicate cumulative postmenopausal metabolic alterations in vascular risk and support metabolomic enhancement of risk stratification in postmenopausal women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain the leading cause of mortality and disease burden globally, particularly among women1. The risk of CVD increases substantially after menopause, a phenomenon attributed to declining estrogen levels, metabolic disturbances, and vascular dysfunction2. While previous studies have primarily focused on traditional CVD risk factors (such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance) in relation to menopause3, the complex metabolic alterations and underlying biological mechanisms associated with menopausal transition remain incompletely understood.

Recent advances in metabolomics technologies have provided new perspectives for investigating disease mechanisms. Metabolomics, through high-throughput measurement of metabolites in blood or other biological samples, offers comprehensive insights into dynamic metabolic states, reflecting the interplay between genetic and environmental factors while potentially revealing disease pathways4. Studies have demonstrated that specific metabolomic signatures are closely associated with CVD and its risk factors5. For instance, certain lipid metabolites, amino acids, and intermediates of glucose metabolism have been identified as potential biomarkers for CVD6. Metabolomic studies in postmenopausal women are limited, especially regarding the link between time since menopause (TSM), metabolomic signatures, and CVD risk. While metabolomic profiles are associated with cardiovascular outcomes, their ability to enhance risk prediction beyond traditional models remains unclear.

Menopause represents a critical physiological transition in women’s lives, with metabolic changes potentially extending over years and having long-term health implications7. Age at menopause and time since menopause (defined as the duration from age at menopause to current age) may be key indicators for assessing the metabolic impact of menopause. Previous studies have largely treated menopause as a static exposure variable, overlooking the dynamic changes that occur over time post-menopause8. In addition, the metabolic pathways underlying the association between TSM and CVD risk remain poorly understood, and it is unknown whether TSM and its related metabolomic signature can enhance the prediction of cardiovascular events. Identifying metabolomic signature associated with TSM and elucidating their relationship with cardiovascular risk may offer novel insights into the mechanisms underlying menopause-related CVD and inform risk stratification and intervention strategies for postmenopausal women.

Based on these considerations, this study aims to systematically investigate the relationships between time since menopause (TSM), metabolomic signature, and CVD risk using metabolomics data from the UK Biobank (Fig. 1). Specific objectives were to: (1) identify and construct a metabolomic signature associated with time since menopause; (2) analyze the associations of time since menopause and the metabolomic signature with CVD risk; (3) investigate potential causal relationships between the metabolomic signature and CVD risk using Mendelian randomization; and (4) assess the predictive value of TSM and the metabolomic signature for CVD risk in postmenopausal women.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The study included a total of 67,582 participants with metabolites at baseline, with a mean (SD) age of 59.8 (5.4) years. The majority of participants were White (96.35%). After a median follow-up of 13.7 years, 8313 people developed CVD. Participants with incident CVD were more likely to have lower education levels (≤10 years: 58.45% vs. 50.40%) and lower annual household income (<£18,000: 35.98% vs. 26.33%) compared to those without incident CVD. The incident CVD group also showed a higher prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²: 30.57% vs. 20.35%) and current smoking (11.12% vs. 7.48%). Poor sleep quality was more common in the incident CVD group (71.31% vs. 66.67%), as was the use of medications such as statins (19.07% vs. 10.46%) and aspirin (15.64% vs. 7.44%) (Table 1). The characteristics of participants at baseline were similar to those observed in the first repeat data (Supplementary Table S8).

Metabolomic signature in response to time since menopause (TSM)

The correlation matrix of all metabolites exhibited an obvious clustering pattern due to the strong correlation between lipids and lipoprotein lipid subclasses (Supplementary Fig. S1). Elastic net regressions on 251 metabolites in baseline data were performed to determine the metabolomic signature in response to TSM. A total of 95 metabolites were selected from the model to calculate the total metabolomic signature, which was significantly correlated with year since menopause (baseline data: r = 0.29, P < 0.001; first repeat assessment: r = 0.26, P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The metabolomic signature spanned various metabolic classes including lipids, lipoprotein subclass, amino acids, fatty acids, ketone bodies, fluid balance-related, glycolysis-related, and inflammation-related metabolites (Supplementary Fig. S2). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that these metabolites were predominantly associated with four metabolic pathways: glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism; valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis and degradation; alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism; and phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis (Supplementary Table S9). As per the metabolites’ coefficients (weights) in the signature (Supplementary Fig. S3), the most pronounced contribution to the positive coefficient of the metabolomic signature came from triglycerides in large LDL, triglycerides in large HDL, and phospholipids to total lipids in Small LDL percentage. Conversely, choline, free cholesterol to total lipids in small VLDL percentage, triglycerides in small LDL, and albumin played a significant role in influencing the reverse coefficient of the metabolomic signature. Associations between TSM and the 95 metabolites comprising the metabolomic signature, as well as the relationships between these metabolites and the risk of CVD and its subtypes were illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Associations of time since menopause, metabolomic signature with CVD risk

In the fully adjusted model, i.e., after TSM and metabolomic signature were mutually adjusted, we observed that TSM per 1 unit (representing a 5-year interval) increment associated with an increased risk of CVD (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.16) and its subtypes of IHD (1.16, 1.12–1.21), AF (1.15, 1.11–1.19), HF (1.18, 1.12–1.24), MI (1.18, 1.12–1.25) and stroke (1.12, 1.06–1.29) (Table 2). The associations also behaved in a dose-response manner (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Metabolomic signature per 1-SD increment associated with increased risk of CVD (HR 1.18, 1.15–1.21) and its subtypes of IHD (1.21, 1.17–1.26), AF (1.15,1.11–1.20), HF (1.30, 1.23–1.36), MI (1.21, 1.15–1.28), and stroke (1.18, 1.11–1.25) (Table 2). The dose–response curves depicted an increased trend of CVD and its subtypes’ risk with increment of the metabolomic signature (Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition, a log-rank test indicated a significant difference among individuals with low (Q1), intermediate (Q2–Q4), and high (Q5) metabolomic signature in the probability of CVD and its subtypes at any time point in Kaplan–Meier analysis (Fig. 3). Pathway-specific analyses also revealed consistent associations with CVD risk across all five group-based metabolomic signatures (Supplementary Table S10). Replication analysis using metabolites at first repeat assessment showed similar findings to the primary analysis using metabolites at baseline (Supplementary Table S11).

Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses

After the analysis was stratified by baseline age (<60 years and ≥60 years) and MHT status (ever used and never used), we observed consistent findings as the primary analysis (Supplementary Table S12). In sensitivity analyses, the findings remained robust after excluding participants who developed incident CVD within the first three years of follow-up and with additional adjustment for medication use, including menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), lipid-lowering agents, and aspirin (Supplementary Tables S13 and S14).

Proportion mediated by metabolomic signature between TSM and CVD

Mediation analysis showed that the metabolomic signature partially mediated the association between TSM and CVD and its subtypes, accounting for 11.6% of CVD, 11.3% of ischemic heart disease, 10.6% of myocardial infarction, 9.2% of atrial fibrillation, 13.8% of heart failure, and 12.4% of stroke risk (Supplementary Fig. S6). Further analyses of metabolite classes showed that relative lipoprotein lipid concentrations, lipoprotein subclasses, fatty acids, amino acids, and inflammation-related metabolites had higher mediation proportions (Supplementary Fig. S7). These proportions should be interpreted as indicative of potential mechanistic pathways rather than definitive causal effects, given the assumptions required in observational mediation analyses.

Mendelian randomization analyses

For the 95 metabolites identified as components of the metabolomic signature, we conducted two-sample Mendelian randomization to assess the causal associations between each metabolite and CVD as well as its subtypes. No evidence of horizontal pleiotropy and heterogeneity was observed. We identified causal associations for 29 metabolites with CVD, 23 metabolites with MI, 4 metabolites with AF, 6 metabolites with HF, 2 metabolites with IHD, and 7 metabolites with stroke (Fig. 4). For example, genetically elevated levels of clinical LDL cholesterol, total lipids in medium LDL, saturated fatty acid were associated with a higher CVD risk and genetically elevated levels of phospholipids to total lipids in medium LDL percentage and cholesteryl esters to total lipids in small LDL percentage were found to be linked a lower risk of CVD.

10-year cardiovascular risk prediction with TSM and metabolomic signature

The addition of the metabolomic signature to SCORE2 significantly increased the AUC from 0.584 to 0.660 (DeLong test P < 0.001), and the addition of TSM increased the AUC from 0.584 to 0.657 (DeLong test P < 0.001). Net reclassification improvement (NRI) analysis further indicated that SCORE2 plus metabolomic signature increased the total NRI by 1.043, and SCORE2 plus TSM increased the total NRI by 0.027, relative to SCORE2 alone (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study identified 95 metabolites significantly associated with TSM using elastic net regression, which were primarily involved in lipid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and amino acid metabolism. A metabolomic signature was constructed based on these metabolites. We found that each SD increase in the TSM-related metabolomic signature was significantly associated with a higher risk of CVD. Additionally, the metabolomic signature mediated the relationship between TSM and CVD risk, suggesting that it may be a critical mechanism underlying the increased CVD risk observed in postmenopausal women. Mendelian Randomization (MR) analysis further revealed that 37 of the 95 metabolites were potentially causally associated with CVD, supporting the potential utility of the metabolomic signature in assessing CVD risk among postmenopausal women.

Premature menopause (<40 years) has been recognized as a risk enhancer for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease due to the cardiometabolic changes that occur earlier3. While 1% of women undergo premature menopause, up to 10% of women experience early menopause, defined as <45 years9. A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that early menopause (<45 years) significantly increases the risk of CVD. For instance, Honigberg et al.10 reported in a study involving 144,260 women that early menopause was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) (HR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.10–1.57) and stroke (HR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.03–1.46)10. Similarly, Zhu et al.11, in a pooled analysis of individual patient data, found that each additional year of delay in menopause reduced CHD risk by 3% (HR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.96–0.98) and stroke risk by 2% (HR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99)11. Moreover, the time since menopause has been identified as a critical predictor of CVD risk. Muka et al.8 reported that CVD risk significantly increased within the first 10 years post-menopause (HR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.05–1.20) and plateaued thereafter8. The associations between age at menopause and CVD subtypes are not consistent. A nationwide cohort study of Korea found that postmenopausal women with a history of premature menopause had 33% higher risk of heart failure (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.26−1.40) and 9% higher risk of Atrial fibrillation (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02−1.16)12.

While the menopause transition contributes to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system as a result of estrogen loss, the current analysis on MHT and CVD suggests that the mechanism underlying the increased risk cannot be attributed solely to estrogen. Instead, estrogen deficiency may be just one component of the causal link between menopause and CVD. Additional intermediate or mediating factors likely contribute to the relationship, warranting further investigation9. Despite growing epidemiological evidence, the mechanistic link between menopause and CVD remains unclear, with limited insights from omics, especially metabolomics. Existing studies indicated that postmenopausal women experience significant metabolic changes, including disruptions in lipid, amino acid, and glucose metabolism7,13, which may underlie increased cardiovascular risk. These findings suggest that analyzing postmenopausal metabolomic profiles could unveil the mechanisms bridging menopause and CVD risk, offering insights for precision intervention strategies.

Menopause marks a key life transition for women, defined by significant endocrine changes, particularly a decline in estrogen. These hormonal shifts lead to extensive remodeling of the metabolomic profile. These metabolic disruptions not only elucidate the mechanisms underlying the elevated CVD risk observed in postmenopausal women but also highlight potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for intervention.

First, menopause induces marked changes in lipid metabolism, evidenced by increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles, as well as diminished functionality of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)7,14. Studies have demonstrated that HDL particles in postmenopausal women tend to shift toward smaller, less functional subtypes, thereby impairing cholesterol efflux capacity and contributing to atherogenesis6,15. Concurrently, elevated triglyceride (TG) levels exacerbate dyslipidemia, a key driver of heightened CVD risk, particularly atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)13,16. Our study also found that over 50% of postmenopausal altered metabolites are lipid-related metabolites. Consistently, we observed more stable associations among participants with a higher baseline lipid burden. In addition, the mediation analysis indicated that lipoprotein lipids accounted for the largest proportion of the association between TSM and CVD.

Second, menopause significantly impacts amino acid metabolism, particularly branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) such as leucine, isoleucine, and valine, as well as aromatic amino acids (AAAs) like phenylalanine and tyrosine17,18. Elevated BCAA levels have been strongly linked to insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and adipose tissue dysfunction19,20. Moreover, BCAAs may exacerbate oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, further amplifying CVD risk21,22. Similarly, elevated AAA levels have been implicated in vascular damage and atherogenesis through the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)16,23. In the pathway-based analysis, our constructed amino acid signature showed stronger associations with CVD and its subtypes than other pathway-based signatures, indicating that postmenopausal amino acid metabolic changes are more closely associated with CVD.

Third, glucose metabolism dysregulation represents another hallmark of postmenopausal metabolic changes. Postmenopausal women frequently exhibit reduced insulin sensitivity and elevated fasting glucose levels15,24. This insulin-resistant state not only directly promotes atherogenesis but also interacts with lipid metabolism to accelerate cardiovascular complications6,23. Furthermore, estrogen deficiency has been shown to influence hepatic lipid metabolism by modulating gene expression, indirectly disrupting fatty acid synthesis and breakdown, thus compounding glucose-lipid metabolic dysfunction14,21.

Finally, menopause-associated metabolic changes are intricately linked to inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways, which further exacerbate cardiovascular risk. Elevated levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and glycoprotein acetyls (GlycA), both inflammatory markers strongly associated with CVD, have been observed in postmenopausal women18,20. Additionally, the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products may activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, triggering inflammatory responses and vascular damage17,22.

A study revealed that the majority of metabolic alterations observed at the onset of menopause persisted or intensified throughout the postmenopausal period. This suggests the persistence of postmenopausal metabolomic changes and their potential cumulative impact on future cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk24. We observed that the metabolomic signature accounted for 12% of the association between TSM and CVD risk, highlighting the unique biological pathways identified through metabolomics. This signature represents a comprehensive depiction of overall metabolic homeostasis in response to TSM. Leveraging the metabolomic signature allows for a more objective and direct understanding of the cumulative metabolic effects associated with time since menopause.

The observed discrete effects (HRs 1.14–1.18) indicate small relative risk increases. Among high baseline risk populations or over extended follow-up periods, these small relative risks may accumulate into more appreciable absolute risk differences. Additionally, from a public health perspective, even small relative risks can have significant implications for overall disease burden when applied to large populations or prolonged exposures. Thus, these discrete effects are better interpreted as incremental signals for risk stratification and predictive modeling rather than standalone triggers for clinical intervention.

One strength of this study is its large-scale prospective cohort with long-term follow-up (∼14 years) and standardized data collection, ensuring robust statistical power and reliable outcomes. The use of untargeted metabolomics reveals diverse metabolic changes beyond predefined pathways, aiding the discovery of novel biomarkers linked to postmenopausal aging. Its longitudinal design captures cumulative metabolic effects across different durations since menopause. Additionally, the well-characterized cohort and detailed clinical and biochemical assessments allow for comprehensive adjustments for potential confounders, including lifestyle factors, comorbidities, and MHT status. However, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, our study was conducted in the UK Biobank, a cohort that is predominantly White and generally healthier than the broader population. These characteristics may limit generalizability, especially for absolute risk predictions. Future work will focus on external validation and model adjustment in more diverse cohorts and healthcare settings to assess transportability and utility. Second, we observed sociodemographic differences between participants with and without CVD. Although these variables were adjusted for in our analysis, residual confounding may still exist due to unmeasured factors or their dynamic changes over time. Accordingly, the reported hazard ratios are best interpreted as relative associations, not causal effects, and should not be interpreted as direct evidence of biological mechanisms or intervention-responsive causal impacts. Third, in this study, we used Cox proportional hazards models and treated non-CVD death as independent censoring. This does not account for non-CVD death as a competing event and may bias the interpretation of cumulative incidence, particularly in populations with a high incidence of non-CVD death. Fourth, one limitation of our mediation analysis is the reliance on strong identification assumptions, including no unmeasured confounding among TSM, the metabolomic signature, and CVD, and the correct model specification. These assumptions cannot be fully verified in observational studies, and the reported mediated proportions should be interpreted as indicative of potential mechanistic pathways rather than definitive causal effects.

In this large-scale prospective cohort study of postmenopausal women, we demonstrated that time since menopause is significantly associated with adverse alterations in the metabolomic profile and increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, independent of chronological age and traditional risk factors. We identified a metabolomic signature linked to time since menopause that not only predicted incident CVD but also partially mediated the association between menopause duration and CVD risk. Mendelian randomization further supported the causal roles of several metabolites in CVD development. These findings highlight the importance of metabolic changes following menopause in shaping long-term cardiovascular health and suggest that metabolomic profiling may provide novel biomarkers and mechanistic insights for CVD risk stratification and prevention in postmenopausal women.

Methods

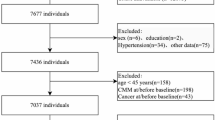

Study design and participants

The UK Biobank is a prospective population-based cohort, recruited over 500,000 volunteers aged 40–69 years between 2006 and 2010. Individuals were invited to attend one of the 22 centers across England, Scotland, and Wales for baseline assessment. Written informed consent was obtained for collection of questionnaire and biological data. UK Biobank has approval from the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/learn-more-about-uk-biobank/about-us/ethics). This research was conducted under UK Biobank application number 227947. Women who were postmenopausal at baseline and had no missing key covariates were included. A prospective design was adopted based on participants with no CVD at baseline (Fig. 6). This study is reported as per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (Supplementary Table S1).

Age at natural menopause and time since menopause

Natural menopause was defined as the absence of menstruation for a consecutive 12-month period, without a history of hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy prior to this time. The duration of the postmenopausal period, measured in time since menopause (TSM), was calculated by subtracting the age at natural menopause from the baseline age at enrollment. For analytical purposes, the calculated time since menopause was standardized by dividing the value by 5, such that a single unit corresponds to a 5-year interval. To limit misclassification from self-reported menopause, we used a standardized definition, excluded uncertain cases (e.g., hysterectomy without bilateral oophorectomy if <55 years), validated self-reports against age, reproductive/surgical history, and medication records, and adjusted for menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).

Metabolomics profiling

This study employed a high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) metabolomics platform (Nightingale Health Ltd, Finland) to analyze EDTA plasma samples from approximately 280,000 participants in the UK Biobank. A total of 251 metabolic biomarkers were measured, including 170 metabolites quantified in absolute levels and 81 composite ratio indices (Supplementary Table S2). These biomarkers represent a diverse array of metabolic pathways, encompassing 14 subclasses of lipoprotein lipids, fatty acids, and their compositions, as well as low-molecular-weight metabolites such as amino acids, ketone bodies, and glycolysis-related metabolites25. To ensure data integrity, rigorous quality control measures were implemented. Natural logarithm transformations and z-score standardization (mean 0, SD 1) were applied to the metabolite concentration data to mitigate systemic and technical variability.

The data analyzed were derived from phase 1 and phase 2 of the UK Biobank study, with around 16,000 participants completing a repeat assessment visit. All metabolic biomarkers were quantified in molar concentration units, providing a comprehensive characterization of the metabolic profiles of the participants. Detailed methodologies regarding the measurement of metabolic biomarkers and quality control procedures have been published in the relevant literature26.

Ascertainment of cardiovascular diseases

The primary endpoint of the study was the occurrence of incident CVD, defined as a composite outcome encompassing myocardial infarction (MI), chronic ischemic heart disease (IHD), heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation (AF), and stroke. Among these, MI and stroke were identified within category 47 of the UK Biobank, based on algorithmically defined outcomes derived from linkage of baseline self-reported data, hospital admission records, and death registry data27. IHD, HF and AF were defined based on the first occurrence data assembled in category 1712 from the UK Biobank. The data includes the first reported occurrence of a disease in either the linked primary care data (cat. 3000), inpatient hospital admissions (cat. 2000), death registry (fields: 40001, 40002), or self-reported data through questionnaires (field: 20002). Detailed information on field IDs and outcome cases was provided in the Supplementary Table S3.

Covariates

We included the following factors in the analyses as covariates according to evidence from previous studies: age at baseline, race/ethnicity, years of education, income levels, Townsend deprivation index, smoking status, alcohol intakes, BMI, sleep status, diet, family history of CVD, and medications, including menopause hormone therapy status, aspirin use, and statins use. Ethnicity was categorized as White, and non-white. Years of education was categorized as ≤10, 11-12, >12. Annual household income level was divided into four categories as level 1 (Less than £18,000), level 2 (£18,000 to £30,999), level 3 (£31,000 to £51,999), and level 4 (greater than 52,000). The Townsend deprivation index, which reflects the area-level socio-economic status, was based on participants’ residential postcode at recruitment and categorized based on quartile. Higher value indicates greater levels of deprivation. Smoking status was categorized as current, former, or never smokers. Alcohol intake was categorized as current, former, or never drinks. BMI was categorized according to the World Health Organization criteria as <18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and ≥30 kg/m2. Diet consumption was classified into ideal or poor according to whether adequate intake of at least half of 10 diet components28. Sleep quality was defined by the criteria recommended by the National Sleep Foundation, which integrates five sleep behaviors (sleep duration, chronotype preference, insomnia, snoring, and daytime sleepiness)29. Participants were divided into two groups: “good sleep quality” and “poor sleep quality”. The family history of CVD was categorized as yes or no. The status of medication usage was categorized into use and non-use. For detailed information on covariate collection and definitions, see Supplementary Tables S4–S6.

Statistical analysis

Identification of the metabolomic signature reflecting menopause duration

We identified metabolites associated with TSM in postmenopausal women using baseline metabolomics data from the UK Biobank. To exclude outliers, metabolite levels falling outside of 4 interquartile ranges from the median were removed. Prior to conducting the planned analyses, all 251 metabolites were log-transformed and standardized to the same scale using z-scores, and correlations among them were examined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The associations of each metabolite with TSM were explored using multivariable linear regression, with a false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-value of 0.05 considered statistically significant.

To identify a metabolomic signature associated with TSM, we applied an elastic net regression model. This regularized regression approach combines the strengths of both Lasso and Ridge methods, effectively addressing multicollinearity, reducing overfitting, and selecting relevant features. Specifically, we regressed TSM on 251 named and standardized plasma metabolites. The optimal penalty parameter (lambda) was determined using a 10-fold cross-validation procedure, selecting the largest lambda value that produced a mean squared error within one standard error of the minimum. The resulting metabolomic signature was calculated as the weighted sum of metabolites with nonzero coefficients, where the weights corresponded to the coefficients estimated by the elastic net model. Finally, the metabolomic signature was standardized using z-scores (mean 0, SD 1), with each unit change in the signature reflecting the combined effect of the selected metabolites’ weighted contributions30. We evaluated the Spearman correlation between TSM and the derived metabolomic signature at baseline (2006–2010) and the first repeat assessment visit (2012–2013).

To further investigate the patterns of the metabolomic signature, we stratified it into three categories based on quintiles: low (Q1), intermediate (Q2-Q4), and high (Q5). This categorization allowed us to examine whether the metabolic alterations associated with post-menopausal duration showed distinct patterns across different groups. Additionally, we built pathway-based signatures. The 251 metabolites were grouped into five categories—amino acids, fatty acids, lipoprotein subclasses, relative lipoprotein lipid concentrations, and other metabolites. For each group, we used the same workflow to derive TSM-associated signatures and assessed their associations with CVD.

Associations between time since menopause, the metabolomic signature and CVD risk

Cox proportional hazard models were also conducted to obtain HRs and 95% CIs for the associations of time since menopause and metabolomic signature with CVD risk. We first assessed the proportional hazards assumption by analyzing the relationship between standardized Schoenfeld residuals and time, confirming that the assumption was not violated. Four nested models were developed, sequentially including four sets of covariates to account for potential confounders. In model 1, age was adjusted; in model 2, ethnicity, socioeconomic status variables of education, income and Townsend index of deprivation were further adjusted based on model 1; in model 3, smoking status, alcohol intake, sleep status, diet status, BMI, and family history of CVD were further adjusted based on model 2; in model 4 (full adjusted model), we further included mutual adjustments for both TSM and metabolomic signature to assess their independent associations. We also examined potential non-linear associations between metabolomic signature, TSM, and CVD risk using restricted cubic spline analysis. Meanwhile, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted to estimate the CVD risk between low, intermediate, and high levels of metabolomic signature groups.

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

To distinguish the effects of chronological age from postmenopausal duration, we conducted a stratified analysis based on baseline age (<60 years and ≥60 years), as these two factors are closely intertwined. We also examined whether the associations of TSM and metabolomic signature with CVD varied by baseline MHT status. To assess the robustness of these findings, several sensitivity analyses were performed, including: (1) exclusion of participants who developed incident CVD within the first 3 years of follow-up; and (2) additional adjustment for medication use, including menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), lipid-lowering drugs, and aspirin.

Mediation analysis

We conducted mediation analyses to investigate whether the association between TSM and CVD could be mediated by metabolomic signature. Using the “mediation” packages of R software, the proportion of mediation was determined by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect, with 95% CIs estimated via bootstrapping. Covariates from the multivariate-adjusted Cox model were included in the mediation analysis to account for potential confounders. Furthermore, we evaluated the contribution of specific metabolite classes in mediating the association between TSM and the risk of CVD, including its subtypes.

Mendelian randomization analyses

Two-sample MR analyses were performed to explore the potential causal associations between the identified metabolites and risk of CVD. We obtained the genetic variants that were considered as instrumental variables for MR from published genome-wide association study summary statistics for each identified metabolite. Summary statistics for CVD and its subtypes were derived from open genome-wide association study projects (Supplementary Table S7). To ensure independence, exposure, and outcome, GWAS were drawn from independent consortia with non-overlapping cohorts.

We conducted stringent linkage disequilibrium (LD) clumping thresholds (10,000 kb clumping window and r2 threshold = 0.1) to select independent single-nucleotide polymorphisms. The random-effects inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method was employed as the primary analysis31,32, as it yields a more precise Mendelian randomization estimate when all instruments are valid33.

10-year cardiovascular risk prediction with TSM and metabolomic signature

To assess the potential improvement in 10-year cardiovascular risk prediction by incorporating time since menopause (TSM) and a metabolomic signature, we added these variables to the recently introduced SCORE2 model, which was developed in 2021 for European individuals without prior cardiovascular disease34. Individuals with a 10-year cardiovascular risk of ≥7.5% were considered to be at high risk. Model performance improvement was evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC) and net reclassification improvement (NRI).

Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P-values were corrected for multiple comparison using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR adjustment. The primary R packages used in the analysis included ‘glmnet’ for elastic net regression and “survival” for Cox regression.

Data availability

The data described in the manuscript will be made available for researchers who apply to use the UK Biobank data set by registering and applying at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/register. Code availability: The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Vervoort, D. et al. Addressing the global burden of cardiovascular disease in women: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 2690–2707 (2024).

Davis, S. R., Pinkerton, J., Santoro, N. & Simoncini, T. Menopause-biology, consequences, supportive care, and therapeutic options. Cell 186, 4038–4058 (2023).

El Khoudary, S. R. et al. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 142, e506–e532 (2020).

Fuller, H. et al. Metabolomic epidemiology offers insights into disease aetiology. Nat. Metab. 5, 1656–1672 (2023).

Ajoolabady, A., Pratico, D., Dunn, W. B., Lip, G. Y. H. & Ren, J. Metabolomics: implication in cardiovascular research and diseases. Obes. Rev. 25, e13825 (2024).

Iliou, A. et al. Metabolic phenotyping and cardiovascular disease: an overview of evidence from epidemiological settings. Heart 107, 1123–1129 (2021).

Clayton, G. L., Borges, M. C. & Lawlor, D. A. The impact of reproductive factors on the metabolic profile of females from menarche to menopause. Nat. Commun. 15, 1103 (2024).

Muka, T. et al. Association of age at onset of menopause and time since onset of menopause with cardiovascular outcomes, intermediate vascular traits, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 767–776 (2016).

Torbati, T., Shufelt, C., Wei, J. & Noel Bairey Merz, C. Premature menopause and cardiovascular disease: can we blame estrogen? Eur. Heart J. 43, 4158–4160 (2022).

Honigberg, M. C. et al. Association of premature natural and surgical menopause with incident cardiovascular disease. JAMA 322, 2411–2421 (2019).

Zhu, D. et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Public Health 4, e553–e564 (2019).

Shin, J. et al. Age at menopause and risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 43, 4148–4157 (2022).

Auro, K. et al. A metabolic view on menopause and ageing. Nat. Commun. 5, 4708 (2014).

Tian, X. et al. Association of lipid, inflammatory, and metabolic biomarkers with age at onset for incident cardiovascular disease. BMC Med. 20, 383 (2022).

Streese, L. et al. Metabolic profiling links cardiovascular risk and vascular end organ damage. Atherosclerosis 331, 45–53 (2021).

Ussher, J. R., Elmariah, S., Gerszten, R. E. & Dyck, J. R. The emerging role of metabolomics in the diagnosis and prognosis of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 2850–2870 (2016).

Lv, J. et al. Plasma metabolomics reveals the shared and distinct metabolic disturbances associated with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease. Nat. Commun. 15, 5729 (2024).

McGarrah, R. W., Crown, S. B., Zhang, G. F., Shah, S. H. & Newgard, C. B. Cardiovascular metabolomics. Circ. Res. 122, 1238–1258 (2018).

Ruiz-Canela, M. et al. Comprehensive metabolomic profiling and incident cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005705 (2017).

Tahir, U. A. et al. Metabolomic profiles and heart failure risk in black adults: insights from the Jackson Heart Study. Circ. Heart Fail. 14, e007275 (2021).

Zhang, B. & Schmidlin, T. Recent advances in cardiovascular disease research driven by metabolomics technologies in the context of systems biology. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44324-024-00028-z (2024).

Muller, J. et al. Narrative review of metabolomics in cardiovascular disease. J. Thorac. Dis. 13, 2532–2550 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Metabolomic profiles, ideal cardiovascular health, and risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation: insights from the Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e028022 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Metabolic characterization of menopause: cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. BMC Med. 16, 17 (2018).

Ritchie, S. C. et al. Quality control and removal of technical variation of NMR metabolic biomarker data in ~120,000 UK Biobank participants. Sci. Data 10, 64 (2023).

Wurtz, P. et al. Quantitative serum nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics in large-scale epidemiology: a primer on -omic technologies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1084–1096 (2017).

Rani, V., Deep, G., Singh, R. K., Palle, K. & Yadav, U. C. Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders: pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci. 148, 183–193 (2016).

Said, M. A., Verweij, N. & van der Harst, P. Associations of combined genetic and lifestyle risks with incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the UK Biobank Study. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 693–702 (2018).

Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 1, 40–43 (2015).

Hui, Z. & Trevor, H. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 67, 301–320 (2005).

Burgess, S. et al. Using published data in Mendelian randomization: a blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 30, 543–552 (2015).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 37, 658–665 (2013).

Burgess, S., Bowden, J., Fall, T., Ingelsson, E. & Thompson, S. G. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology 28, 30–42 (2017).

Group, S. W. & Collaboration, E. S. C. C. R. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur. Heart J. 42, 2439–2454 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource (application number 227947). The authors are grateful to UK Biobank participants. We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273702). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed substantially to the completion of this study. DZ conceived of the presented idea. Q.W. and B.X. performed the data analyses, established the machine learning models, and drafted the manuscript. Q.W., B.X., C.F., M.L., and X.W. participated in data collection. N.S., S.S.V., and S.R.M. provided critical feedback. Q.W., B.X., and D.Z. had primary responsibility for study design and data interpretation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Xie, B., Fu, C. et al. Integrating menopause duration and plasma metabolomics enhances cardiovascular risk stratification in aging women. npj Aging 12, 24 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00323-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00323-z