Abstract

Polymicrobial biofilms are acknowledged as evolutionary hotspots; however, the influence of interspecies interactions on adaptive processes remains ambiguous. Using custom-engineered 3D-printed flow systems, biofilms were grown over an 18-day period to explore the evolutionary dynamics over time between two competing species, Pseudomonas defluvii and Pseudomonas brenneri, within communities of differing complexity, using whole-population and whole-genome sequencing methodologies. P. defluvii demonstrated significant phenotypic and genetic diversification in simple biofilms, yet this variation was reduced in complex biofilms, implying that interspecies interactions constrained its adaptation. In contrast, P. brenneri exhibited negligible evolutionary changes irrespective of the diversity present. Genomic analysis correlated the adaptation of P. defluvii with biofilm regulation and chemotaxis. The co-culture with evolved strains indicated that the variants of P. defluvii outperformed their ancestral forms, while P. brenneri remained unchanged. These results show that while the biofilm lifestyle generally fosters adaptive evolutionary processes, interspecies diversity can restrict diversification in a manner specific to each species. This study provides novel insights into the evolution of bacteria within complex biofilm environments, with implications for understanding microbial behavior in both clinical and industrial settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biofilms are ubiquitous in nature, encompassing 40–80% of bacterial populations1. The biofilm lifestyle often selects diverse phenotypes within single-species biofilms, promoting intraspecific diversity2,3,4,5. This diversification is driven by the heterogeneous environments within biofilms, characterized by gradients in the composition of nutrients, oxygen, and the matrix6. Despite extensive research on single-species biofilms, the evolutionary dynamics within polymicrobial biofilms has not yet gained the same focus. An important question in polymicrobial biofilms is the degree to which interspecies interactions substitute for intraspecific diversity7 and influence species co-adaptation8,9. Interspecies interactions and diversification impact various biofilm characteristics, such as spatial arrangement and architecture10,11, productivity, synergy, and stability, which can influence adaptation12,13,14,15,16. However, the extent to which these interactions drive or constrain evolutionary dynamics in established polymicrobial biofilms over extended periods of time has not been fully elucidated.

Previous studies on biofilm evolution have focused mainly on daily bead transfers of biofilm populations17,18,19,20 for a maximum of 180 days4, to examine formation and dispersal dynamics. Flow cells also allow the study of established mature biofilms, although for a reduced period of time, up to 7 days21,22,23. Studies seeking to unravel co-adaptation patterns of defined biofilms typically involve 2–3 species7,13,16,24, with the exception of a four-species biofilm15. Moreover, biofilm evolution studies have so far primarily explored the adaptation of one focal species, and although there are examples of research that specifically track the evolution of two species, these have mostly been conducted in dual-species combinations13,25,26. Consequently, our understanding of how interspecies interactions influence the evolutionary dynamics of several species within established biofilms does not yet include a complexity greater than 3 species over extended periods (>7 days). Novel experimental setups are needed to bridge this gap, track evolution in complex biofilms, and contribute to deciphering prolonged adaptive landscapes within complex microbial communities.

In this study, we investigated the impact of species diversity on evolutionary dynamics within established biofilms over 18 days using custom-designed 3D-printed flow models. We focus on Pseudomonas brenneri and Pseudomonas defluvii in multispecies communities of wastewater bacteria (5 species). P. brenneri and P. defluvii, together with Bacillus thuringiensis were isolated from the same WWTP in Kalundborg (Denmark), whereas Brevundimonas diminuta and Pandoraea communis were isolated in the WWTP in Odense (Denmark)27. We chose P. brenneri and P. defluvii as focal species because of their known antagonistic interactions, where P. brenneri tends to dominate and significantly reduce the presence of P. defluvii. We measured community composition using 16S amplicon sequencing and identified mutations using whole-population and whole-genome longitudinal sequencing (WGS), revealing changes in biofilm formation and chemotaxis. Tracking two focal species, we were able to conclude that the biofilm lifestyle can promote diversification, while interspecific diversity restricts adaptation in P. defluvii but not in P. brenneri. Intriguingly, despite their close taxonomy, our results showed distinct evolutionary trajectories for the focal species. The results of this study show that interspecies interactions substitute for intraspecific diversification over extended periods of time (up to 18 days) and in complex communities (>3 species).

With our collected data, we highlight the dual role of diversity as both a driver—promoting adaptive evolution through increased competition and niche colonization—and a constraint, where competitive exclusion and resource limitations hinder evolutionary progress. By extending the study period and examining two competing Pseudomonas species, this research provides relevant insights into how biodiversity shapes evolutionary pathways in established multispecies biofilms, with significant implications for predicting how species adapt while co-existing in a biofilm.

Results

A novel experimental method enables the study of the effects of prolonged interspecies interactions on genetic diversity in biofilms

Understanding the effects of interspecies interactions on emergent genetic variation in established multispecies biofilms is an area of ongoing exploration. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted an 18-day evolution experiment to investigate the impact of complex biofilm communities on de novo genetic diversity using custom-designed 3D-printed biofilm flow models (Fig. 1). Top and side views of the model can be seen in Fig. S1.

Experimental evolution setup to analyze the impact of diversity on long-term evolution in multispecies biofilms (upper panel). Beige and brown cells represent P. defluvii, and light and blue cells represent P. brenneri. A schematic representation of vertical sections of 3D-printed flow models used for biofilm growth in this study (lower panel). Slides 1 and 2 are placed in parallel, and the media flows in between the two slides.

P. defluvii (PD) and P. brenneri (PB) were isolated from the same wastewater treatment facility and were chosen as focal species within the communities due to their known antagonistic interactions, which decreased the abundance of P. defluvii within mixed communities (Fig. S2). Previous work revealed that the presence of P. defluvii and P. brenneri enhanced the selection of B. thuringiensis variants in biofilms27. In this work, we focused on tracking the interactions between these two Pseudomonas species during prolonged co-culture in a biofilm. We chromosomally-tagged them to enable division into subpopulations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). As depicted in Fig. 1, we grew these strains in combinations of single, dual, triple, quadruple, and quintuple species to create more complex communities, including B. thuringiensis (BT), B. diminuta (BD), and P. communis (PC) (Table S1). Even though B. diminuta and P. communis were not co-isolated, they originated from a similar environment to the rest and were considered adequate for these combinations. Acronyms are used to describe combinations. These communities were grown as established biofilms in triplicate over 18 days, and each replicate was run in four models, one for each day of sampling (days 4, 10, 14, and 18).

The total population sizes increased slightly over time for all combinations but decreased again on day 18 (Fig. 2a). Despite fluctuations in individual species populations, biofilm biomass was relatively stable over time, which confirmed the use of flow systems to grow stable biofilms. The design of the 3D-printed models allowed us to have two replicate slides per biofilm combination and sampling day at our disposal. One of the slides was examined by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM). With the second slide, we evaluated the relative abundance of all species by 16S amplicon sequencing, as well as the phenotypic and genotypic variation of specific subpopulations of P. defluvii and P. brenneri by flow cytometry. This setup allowed us to evaluate correlations between intraspecific diversity, variation, and interspecies interactions, while simultaneously examining the spatial position of the species within the biofilm. These multi-method analyses provide a comprehensive picture of microbial interactions and evolution within multispecies biofilms.

a CFU/slide of each biofilm combination over time. Single-species biofilms are shown in brown (P. defluvii) or blue (P. brenneri), while combinations are shown in black. Each point is the mean of three technical replicates ± SEM. CFU changes were not statistically different (Tukey’s post-hoc test, p > 0.05), except for the PD:PB:BT community that increased from days 4 to 10 (p = 0.0273) and decreased from days 10 to 18 (p = 0.0408). b Relative abundance of each bacterial species in every combination over time. The values shown are normalized to 1 from total CFU counts, and the error bars represent SD (n = 3). PD P. defluvii, PB P. brenneri, BT B. thuringiensis, BD B. diminuta, PC P. communis.

P. defluvii can persist in complex biofilms, although in a low abundance

Species abundance ratios may be affected by biodiversity levels and the characteristics of cross-species relationships. These relationships between species are often unpredictable in biofilms, which motivated the detailed quantification of communities over time. P. brenneri was more abundant in all communities and on each sampling day (50–96%) (Fig. 2b). Consistent with the results of a 24-h biofilm experiment (Fig. S2), P. brenneri dominated P. defluvii, achieving its highest abundance (96%) in dual biofilms (PD:PB). In particular, P. defluvii forms biofilm in similar amounts to P. brenneri when grown alone (Fig. S2), and their growth rates as monocultures are not significantly different (Table S2). Despite the dominance of P. brenneri, P. defluvii was able to persist and co-exist in all dual and multispecies communities (Fig. 2b). When other bacterial species were added to the community, the abundance of P. defluvii decreased from 2–14% to 0.3–4%. This observation was further corroborated by monitoring fluorescence by flow cytometry in the two strains, which also revealed a decrease in the presence of P. defluvii with increased community diversity (Fig. S3). Statistical analysis of the data presented in Fig. S3 revealed no significant differences in colony-forming unit (CFU) counts across days (except for day 10 in the four- and five-species combinations) nor combinations (except for day 4 and 14 in PD:PB, and days 4 and 10, and days 4 and 14 in PD:PB:BT). Nonetheless, the decrease in the abundance of P. brenneri suggests that the introduction of additional strains disrupts the competitive advantage of P. brenneri over P. defluvii. This disruption may result from resource partitioning or niche overlap, wherein the introduced strains diminish P. brenneri’s access to resources.

The three additional strains also showed distinct persistence patterns. The abundances of B. thuringiensis (from ~12% to ~2%) and P. communis (from ~2% to ~0.4%) decreased over time but persisted in the biofilms. In contrast, the abundance of B. diminuta (from ~9% to ~30%) increased throughout the experiment, suggesting that the growth of B. thuringiensis and, to a lesser extent, P. communis could be suppressed by the presence of other species. Variable abundances of B. thuringiensis, B. diminuta, and P. communis highlight the fluctuations observed in multispecies biofilms over time, as well as the limitations of end-point measurements.

Diversity shapes the phenotypic adaptation differently in P. defluvii and P. brenneri

To assess potential adaptations in this system, we conducted high-throughput screening for phenotypic changes, focusing on colony morphology, as these changes are often indicative of biofilm adaptations28,29,30. We observed higher phenotypic variation in populations of P. defluvii (Fig. 3a, brown) compared to P. brenneri (Fig. 3a, blue). Further, P. defluvii biofilm populations became more diverse when grown alone than when grown with other species, with morphotypic variation dropping from 50–70% in monoculture to 0–20% in co-culture or multispecies combinations (Fig. 3a, brown). We observed an experimental outlier on day 10 where a five-species combination showed 100% morphotypic frequency. Colonies identified as phenotypic variants across combinations and sampling days were not identical to each other, but rather reflected varying degrees of morphological divergence from the wild-type colony. Figure 3b shows a representative overview of the different phenotypic variants. This finding highlights the relevance of studying the effects of interspecies interactions on adaptive processes.

a Percentages of P. defluvii (brown) and P. brenneri (blue) phenotypic variants in each combination through the 18-day experiment. The numbers were obtained by phenotypic assessment of 92–96 isolated samples from each biological replicate in Congo red plates in every combination (a total of 5667 P. defluvii samples and 5710 P. brenneri samples were screened). The bars show the mean (n = 3) and SEM, and the individual values are presented in Table S3. PD P. defluvii, PB P. brenneri, BT B. thuringiensis, BD B. diminuta, PC P. communis. b Comparison of colony phenotypes of selected P. defluvii variants to their ancestor strain. The variants are presented according to the combination from which they were isolated. These images are representative of all the variants observed on Congo red plates. c Metagenomics analysis of samples of P. defluvii-derived variants obtained from different combinations after the 18-day experiment and analysis of genomes of selected evolved P. defluvii variants. Color gradient represents mutation frequencies across combinations in metagenomic samples (gray: 100%; light brown: 0%); gray boxes represent 100% frequency in isolated variants. DGC diguanylate cyclase. A detailed list of all the mutations is summarized in Table S4.

Observations in P. brenneri populations were almost opposite to those of P. defluvii, despite their close taxonomy. Interspecific diversity had a minor effect on phenotypic variation in P. brenneri, with only a slight increase in co-cultures, reaching up to 25% morphotypic frequency in the four-species community (Fig. 3a, blue). This suggests that interspecies interactions may favor phenotypic variation in P. brenneri, albeit to a limited extent. The frequency of phenotypic variation in P. brenneri was substantially lower within the biofilm of a single species (Fig. 3a, blue, PB, 0–7%) compared to P. defluvii (Fig. 3a, PD, 50–70%). Unlike P. defluvii, these results demonstrate that diversity has a weaker effect on the prolonged adaptation of P. brenneri after 18 days of coevolution. This limited diversification may be context-dependent, as P. brenneri’s dominance in the mixed-species biofilm could reduce selective pressure for adaptation. Overall, the effect of interspecies interactions on phenotypic diversity within the two focal Pseudomonas species appears to be species-specific.

P. defluvii exhibited several morphologies, including distinct wrinkled phenotypes and larger colony sizes compared to the ancestor strain (Fig. 3b), while variants of P. brenneri showed only slight differences in color and did not show wrinkled phenotypes (Fig. S4a). The variants of P. defluvii and P. brenneri presented in Figs. 3b and S4a were selected for further genotypic characterization.

Interspecies interactions have a stabilizing effect on genotypic traits in P. defluvii populations as opposed to P. brenneri

We sequenced populations of P. defluvii (see Fig. 3c) and P. brenneri (see Fig. S4b) that evolved under various species mixtures to identify the most common mutations. Our approach allowed for the confident identification of all mutations reaching frequencies >5%. Similarly to our observations on phenotypic variation, P. defluvii populations revealed varying levels of genotypic variation, while P. brenneri populations showed minimal genotypic changes. However, genotypic variation was higher in P. brenneri populations than predicted by phenotype assessment, indicating that colony variation is not always a proxy of genetic variation.

More genes were observed to mutate in P. defluvii when grown alone than in combination with other species (Fig. 3c; PD and PD:PB:BT), which is consistent with our observations of the decrease in phenotypic variation in combinations of mixed species. The mutations present in P. defluvii grown as a single species included nine gene targets, while only 4–5 gene targets were mutated in variants of P. defluvii isolated from dual and multispecies combinations. However, the frequency of selected mutations tended to increase in multispecies communities compared to when P. defluvii was grown alone. Mutations can be classified into three main groups according to their target genes: c-di-GMP metabolism/biofilm metabolism, membrane protein/general signal transduction, and chemotaxis. Table S4 provides a detailed summary of the mutations found in the predicted proteins (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that the presence of other species influences the adaptation of P. defluvii by leading to the fixation of specific mutations involved in niche specialization.

To validate our inferences from deep sequencing, we isolated and sequenced individual clones that represented the observed morphotypes of P. defluvii (Fig. 3b) and P. brenneri (Fig. S4a). Clone mutations were correlated with those found at various frequencies in populations, although observed mutations acquired in different combinations (single, dual, or multispecies) are different between isolated variants (Table S4; insertions, deletions, and single nucleotide polymorphisms), suggesting that different mutation acquisition mechanisms could be in place (i.e., replication errors, replication slippage). P. defluvii morphotypes acquired mutations in three diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and six aerotaxis/chemotaxis proteins (Aer4, Aer5, CheA, CheB3, CheY, and a chemotaxis transducer). The associations between mutations and observed phenotypic changes (summarized in Table S5) suggest that mutations in predicted DGCs produce a more wrinkled phenotype (V4, V5, V7, and V8) than mutations in chemotaxis proteins (V2 and V3), except for V6, which has a mutation in cheY and the most extreme wrinkled phenotype. The mutations did not affect any essential genes and therefore, were not expected to have a significant impact on fitness. Taken together, these results show that the continued abundance of P. defluvii (Fig. 2b) is related to phenotypic and genotypic changes in biofilm formation and chemotaxis, which are stabilized by interspecies interactions in high-diversity communities (Fig. 3).

Mutations in P. brenneri occurred more frequently in mixtures of dual species (PD: PB) (Fig. S4b) than in combinations of single species and four species. The two selected variant clones of P. brenneri exhibited small phenotypic differences compared to the ancestor strain (Fig. S4a), with the most frequently mutated genes observed (predicted proteins with sensor domains (LysM and PAS) and acetyl-CoA synthetase) (Fig. S4b). Despite the low frequency of phenotypic variation in P. brenneri, genome sequencing suggests that there are some changes in the genotype that are also influenced by interspecies interactions, as the number of mutated genes is reduced in the four-species combinations. The data collected on the adaptation patterns of P. brenneri show a generally low phenotypic and genotypic variation in monoculture biofilms for extended periods, as well as in co-existence with other species, in sharp contrast to the competing species, P. defluvii.

The biofilm architecture reveals the intermixing between competing strains rather than intraspecific segregation

We speculated that the relative abundances of P. brenneri and P. defluvii would be reflected in the biofilm organization and that interspecies interactions could cause repositioning in combinations of three species or more. To understand the spatial location of these two species, we used confocal microscopy to study the biofilm architecture of both P. brenneri and P. defluvii over time. Microscopy images reflect significant fluctuations in the abundance of P. defluvii, particularly when combined with P. brenneri and three additional species during the evolution experiment (Fig. 4, green and red, respectively). Consistent with our 16S amplicon sequencing data (Fig. 2b), the presence of P. defluvii is considerably lower in the five-species community compared to other low-diversity combinations. The distribution of the two focal species was not affected by additional interspecies interactions (Fig. 4). P. defluvii co-existed similarly with P. brenneri in all combinations throughout the experiment, and all combinations of P. defluvii and P. brenneri showed intermixing, which is typically linked to cooperative interactions. This intermixing appears to intensify towards day 18 of the experiment, especially in the dual-species biofilm. It can be hypothesized that increased intermixing on day 18 could influence the decrease in genotypic variation of P. defluvii detected in the sequencing data.

Biofilm formation of the communities and single species biofilms (P. defluvii and P. brenneri) by confocal microscopy throughout the sampling days of the experiment (4, 10, 14, and 18 days). The strains P. defluvii (green) and P. brenneri (red) were tagged with GFP and mCherry, respectively. Lectin WGA (Alexa-Fluor 647) binding (yellow) represents B. thuringiensis and glycoconjugates. The scale bar represents 20 µm. PD P. defluvii, PB P. brenneri, BT B. thuringiensis, BD B. diminuta, PC P. communis.

Our pairwise cross-correlation (PCC) analysis on the CLSM images revealed that P. brenneri and P. defluvii are randomly intermixed despite the competition dynamics (Fig. S5a; PD:PB and PD:PB:BT), and a more stabilized positioning (less random) in the more complex communities (four and five species). The implications of these fluctuating dynamics on the selection pressure for new variants in multispecies biofilms warrant further investigation.

We also tracked B. thuringiensis using WGA, which binds to N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) in the gram-positive peptidoglycan layer. This allows visualization of B. thuringiensis in the biofilm due to the distinct size difference, even though GlcNAc can also be found in the lipopolysaccharides of the Gram-negative outer membrane. However, lectin WGA leads to matrix staining as seen in the PB:PD co-culture in Fig. 4 (yellow), as well as P. defluvii and P. brenneri monocultures (Fig. S6), highlighting the complex role of matrix components in biofilm formation and spatial organization. Although not central to our main findings, these observations may provide useful context for future investigations into matrix-related biofilm dynamics.

The evolved variants promote the co-existence of P. defluvii with P. brenneri

The mutations observed in P. defluvii variants showed changes in biofilm formation and chemotaxis. To investigate the impact of evolved mutants on co-cultures, we conducted a 10-day experiment with these variants in custom-designed 3D-printed biofilm flow models (see combinations in Table S6). Although new mutations could arise during this evolution experiment due to its duration (10 days), the aim was to assess whether the original mutations produced a fitness advantage in the biofilm model.

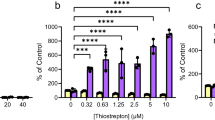

Based on the abundance of species, we tested whether adapted strains of P. defluvii and P. brenneri influenced strain co-existence and the ability to establish biofilms within a community. The two variants derived from P. brenneri showed that they continued to dominate P. defluvii, without changes compared to the ancestor (Fig. 5a) or the original experiment (Fig. S3). In particular, P. defluvii persisted even in combinations with evolved variants of P. brenneri. Compared to the ancestor combination, the abundance of P. defluvii variants increased by a mean of 6 times in co-culture with the ancestral strain of P. brenneri (Fig. 5a). This change highlights the adaptive capacity of P. defluvii variants to co-exist when co-cultured with P. brenneri.

a Proportion between P. defluvii (brown) and P. brenneri (blue). 100,000 cells were counted for each biological replicate by flow cytometry from one of the PC slides (in total, 300,000 fluorescent cells). Data represent the mean and SEM (n = 3). The differences in percentages were tested as non-statistically significant with the PD:PB ancestor combination as a reference (Dunnett’s post-hoc test, p > 0.05), except for PD.V2 (p = 0.0195) and PD.V5 (p = 0.0101). b CFU/slide of all bacteria grown in each combination shown over time, representing biofilm formed on the PC slide. Data represent the mean (n = 3) and SEM, with three technical replicates each. CFU counts showed no significant difference between any combination for either strain (Tukey’s post-hoc test; p > 0.05). c CLSM images from some of the different dual combinations on day 10 of the experiment. P. defluvii and its derived variant (PD.V2) are shown in green, whereas P. brenneri and its derived variant (PB.V2) are shown in red. The images were taken with a 63x oil objective. The chosen images are representative of three biological replicates, recorded with at least six positions. The scale bar represents 20 µm.

The spatial organization of the two strains was further investigated through microscopy imaging (Fig. 5c). The increased abundance of variants of P. defluvii within the biofilm alongside P. brenneri in microscopy images confirms the ability of P. defluvii to co-exist more effectively than the parental strain in a biofilm-selecting environment. These results suggest that the mutations identified in genes related to biofilm and chemotaxis provide adaptations for these variants to co-exist with P. brenneri, likely supporting the stability of the community.

Discussion

Biofilms exhibit greater genotypic and phenotypic variation than planktonic populations for two nonexclusive reasons: population subdivision caused by environmental structure, and selection for more diverse traits due to niche heterogeneity and ecological interactions among strains or species17,31,32,33,34,35. While interspecies interactions influence the spatial arrangement of species in biofilms36, their impact on evolution and co-adaptation remains poorly elucidated. A greater understanding of evolution in complex communities such as polymicrobial biofilms is vital to predict novel variants or emergent properties and ultimately to manipulate bacterial communities in clinical and industrial applications. The complexity of interspecies interactions is a key challenge in experimental evolution. Here, we sought to determine how interspecies interactions can affect adaptation during prolonged co-culture by examining species abundance, co-localization strategies, and phenotypic and genotypic variation.

We investigated the process and adaptation mechanisms of two competing Pseudomonas species within established biofilm communities comprised of up to five species for 18 days. Our findings reveal disparities in how interspecies interactions affect evolutionary trajectories among Pseudomonas species (Figs. 3 and S4). By combining the use of 3D-printed flow models with two labeled focal strains, we were able to track dynamics among and within two species while simultaneously measuring co-localization patterns within biofilms. We determined that P. defluvii co-existed with P. brenneri and other species in diverse communities despite being the least abundant (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we confirmed that evolved subpopulations of P. defluvii were better adapted to form biofilms in conjunction with P. brenneri (Fig. 5) and identified the genes involved in the emergence of these community-optimized variants.

Interspecies interactions influenced adaptation by constraining diversification in a species-dependent way. P. defluvii showed a decrease in phenotypic variation in mixed-species communities compared to single-species biofilms (Fig. 3a), while P. brenneri exhibited minimal variation under all conditions (Fig. 3a, blue). This study supports the notion that interspecific diversity, when present, reduces and substitutes for intraspecific diversity, based on previous findings in less complex communities and over shorter periods7,15. Furthermore, our results agree with the observation that bacterial adaptation is reduced in highly diverse environments37 and suggest that competitive interactions exert constraining selective pressure. The limited diversification of P. brenneri may be context-dependent, as P. brenneri’s dominance in these biofilm co-cultures could contribute to the limited evolutionary changes. In contrast, diversity created intense selection pressure for community-optimized variants of P. defluvii that are better adapted to co-exist with P. brenneri (Fig. 5). Therefore, the effect of interspecies interactions on adaptation cannot be predicted on the basis of phylogenetic proximity and can change depending on the ecological scenario.

Differences in mutation rate observed between P. defluvii and P. brenneri could also be influenced by population size and growth rate dynamics. Faster-growing populations can accumulate more mutations simply due to more replication cycles. Both species showed no significant differences in growth rate (P value < 0.01) when grown as monocultures in rich media (Table S2), suggesting that they grow similarly. Smaller populations, like P. defluvii, may retain slightly deleterious mutations due to weaker selection; therefore, it cannot be excluded that the impact of competition on population sizes leads to an overestimation of the mutation rate.

Heterogeneity within biofilms imposes selective pressures on all co-existing species, often resulting in subpopulations of genotypic variants that specialize in colonization of different niches. Based on the mutations found in DGCs, which are expected to increase biofilm formation38, and chemotaxis proteins23,39 (Fig. 3c), we suggest a link between enhanced biofilm formation and spatial positioning within communities. Consistent with our results, elevated levels of c-di-GMP are typically related to pro-biofilm traits and pathways that control bacterial interactions40. In Pseudomonas species, high levels of c-di-GMP by DGCs favor biofilm formation41,42,43. Lind et al. showed a link between the appearance of wrinkled phenotypes and mutations in DGCs in Pseudomonas fluorescens38, similar to wrinkled variants of P. defluvii with mutations in four DGCs (Fig. 3). We also found mutations in CheB and CheY in three variants, which are homologous to WspF and WspR, respectively. Mutations in wspF in P. aeruginosa result in enhanced biofilm formation by constitutive activation of DGC WspR, which produces c- di-GMP23,39. Although energetically costly, chemotaxis plays a role in initial biofilm attachment—facilitating niche colonization—as well as nutrient acquisition44,45. It can be hypothesized that observed mutations in chemotaxis and aerotaxis proteins (Aer5, Aer4, CheA, CheB3, and CheY) also play a role in the initial attachment and positioning of P. defluvii within a biofilm, contributing to the establishment of variants developed by P. defluvii. The effect of spatial organization is key in the co-adaptation of competing species46,47, and these results indicate potential new relationships between cell-cell communication, biofilm formation, and interspecies interactions in the context of co-adaptation patterns.

Lastly, by using replicate slides, we were able to simultaneously visualize the intermixing of the competing species in the biofilm (Fig. 4). This spatial arrangement remained unchanged in biofilm populations of variants evolved from P. defluvii, suggesting that mutations do not alter their position within the biofilm, even though the abundance had increased compared to the biofilm of the ancestor (Fig. 5). Future research could help us differentiate between the positioning of ancestors and variant populations, answering whether P. defluvii subpopulations originate in one biofilm layer/position or are common to all the P. defluvii niches observed in microscope images. However, our unique experimental design enabled us to examine both the biofilm architecture and the evolution of the two focal species.

In conclusion, we developed a novel 3D-printed flow model for evolutionary experiments in established biofilms. This setup is particularly beneficial for the study of evolutionary trajectories of complex communities, as manipulation is reduced compared to other biofilm models that rely on daily transfers. By investigating the adaptive trajectories of two Pseudomonas species in co-culture, we showed that the impact of competitive interactions on phenotypic and genotypic variation is dependent on species. Besides this observation, we also found enhanced co-existence of P. defluvii variants with P. brenneri, suggesting that co-existence may facilitate sharing of matrix components and co-metabolism. Our insights into how diversity differently shapes the adaptation of competing species in complex biofilms advance our understanding of bacterial interspecies interactions and highlight the challenges of predicting biofilm evolution. Using a similar approach to ours, the directed evolution of a focal species can be applied to optimize the productivity and efficiency of bacterial communities used for bioproduction or bioremediation. These findings have implications for anticipating biofilm establishment and persistence patterns in industrial and clinically relevant settings, although questions remain about how cooperative, rather than competitive, interactions between the other two focal species would shape evolutionary trajectories.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study were previously isolated from two wastewater treatment facilities in Denmark. Pandoraea communis (PC) and Brevundimonas diminuta (BD) were isolated from Odense WWTP, while Pseudomonas defluvii (PD), Pseudomonas brenneri (PB), and Bacillus thuringiensis (BT) were isolated from Kalundborg facility (Denmark)48. The strains were grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, VWR International, Leuven, Belgium)49. 1.5% agar (VWR International, Leuven, Belgium) was added to the TSB to create Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) when needed. To assess biofilm-related phenotypes, a Congo red assay was performed by adding Congo red (40 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and Coomassie brilliant blue G250 (20 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) to the TSA50.

Fluorescent tagging of focal species

P. defluvii and P. brenneri were genetically modified to express GFP16 and mCherry51, using plasmids pUC18T-miniTn7-PlppGFPmut3-TcR and pUC18T-miniTn7-PlppmCherry-TcR, respectively. Briefly, the pUC18-derivative plasmids and the helper plasmid pTNS252 were introduced into P. defluvii and P. brenneri through a four-parental mating process involving the helper plasmid pRK60053. PCR and microscopy confirmed the specific integration of the miniTn7 cassettes and the resulting fluorescence, respectively.

Set-up and analysis of experimental evolution

For our experimental evolution setup, we utilized custom-designed 3D-printed flow models (Fig. 1) with two sets of rails to hold polycarbonate slides (1.2 cm× 1.2 cm× 0.75 mm). The models were printed with Ultrafuse PLA Pro1 filament in an Ultimaker S3 (Prusa, Prague, Czech Republic) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and sterilized by 70% ethanol washing and autoclaving.

The biofilm evolution experiment lasted for 18 days and was conducted in 3D-printed flow models at room temperature (RT). Six combinations (Table S1) were sampled four times during the 18 days (days 4, 10, 14, 18). Each combination was tested with three biological replicates for each sampling point. This resulted in 72 biofilm system samples plus one system running with only media as a negative control during the trial. Overnight cultures were adjusted to OD600 1.0, and combinations were mixed with equal volumes of the adjusted cultures. The flow models were inoculated with 3 ml of adjusted culture injected into the sealed model with a syringe, and the injection point was sealed with silicone immediately after the inoculation. The supply tube was clamped off 1 h before the flow was started, allowing the bacteria time to settle. The flow was adjusted with a 205S peristaltic pump (Watson-Marlow Limited, Cornwall, UK) set to 0.6 rpm, so the media in the model was replaced once per 24 h. To support biofilm formation while avoiding nutrient oversaturation, we maintained a constant flow of 20% diluted TSB. In the flow model, the design ensured media to flow between both slides at the same time (Figs. 1 and S1), and two slides were inserted, allowing for multiple analyses to be performed.

A second experiment was conducted using selected isolated variants from the first experimental evolution assay to test their effect when co-existing with either P. brenneri or P. defluvii. This experiment ran for 10 days, and all combinations were run with three biological replicates. Controls were both wild-type ancestor strains grown together. P. defluvii wild-type was tested with two different P. brenneri variants, while P. brenneri wild-type was tested with 7 different P. defluvii variants.

For biofilm retrieval from the 3D-printed models, the pellicle found inside was removed with a sterile inoculation loop. The polycarbonate slides were carefully removed with sterilized forceps and washed in 2 ml 1x PBS. To retrieve the biofilm attached to polycarbonate slides, the slides were placed in a 5 ml tube containing 2 ml of 1x PBS and sonicated for 5 min at power 8 in the sonication bath Ultrasonic Cleaner USC-THD (VWR International, Leuven, Belgium). Total CFUs per slide were estimated by plating serial dilutions.

DNA extraction and analysis of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing

DNA for the 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing was extracted from biofilm cells retrieved from polycarbonate slides. One milliliter of the sample was used for flow cytometry before being frozen at −20 °C. The DNA extraction was done by spinning down the samples for 50 min at 10,000 × g, carefully removing the supernatant, and adding 20 µl of InstaGene Matrix (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Amplicon sequencing libraries were prepared using a two-step PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 regions. PCR was performed for 30 cycles using primers Uni341F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) and Uni806R (5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′) as previously described54. First, PCR amplification products were purified using HighPrep PCR clean-up (MagBio Genomics, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) using a 0.65:1 (beads:PCR reaction) volumetric ratio. A second PCR reaction was performed to add Illumina sequencing adapters and sample-specific dual indexes (IDT Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) using PCRBIO HiFi (PCR Biosystems Ltd., London, UK) for 15 cycles. For the second PCR, products were purified with the HighPrep PCR Clean Up System, as described for the first PCR. Sample concentrations were normalized using the SequalPrep Normalization Plate (96) Kit (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were then pooled and up-concentrated using the DNA Clean and Concentrator-5 Kit (Zymo Research, Tustin, CA, USA). The library pool’s concentration was determined using the Quant-iT High-Sensitivity DNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies by ThermoFisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and diluted to 4 nM. The library was denatured, diluted to 9 pM, and sequenced following the manufacturer’s instructions on an Illumina MiSeq platform (University of Copenhagen), using Reagent Kit v3 [2 × 300 cycles] (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Primers and quality trimming were performed using the Cutadapt v.2.3 tool55. Reads were processed for error correction, merging, and amplicon sequence variants (ASV) generation using the DADA2 version 1.10.0 plugin for QIIME256,57. Taxonomic annotation was done using the q2-feature-classifier classify-sklearn module trained with SILVA SSU rel. 132 database58. The dataset was further cleaned using the Phyloseq R package59. ASVs were filtered based on 16 s rRNA V3-V4 region size and manually checked for taxonomic annotation towards PD, PB, BT, BD, and PC. Decontam60 was used to check for PCR contaminants as determined by the prevalence of ASVs in the negative controls. Finally, ASVs with less than 100 reads across the whole dataset were removed, and the detection limit for ASV occurrence in each sample was set to 0.02% of the total reads count.

Flow cytometry and FACS

For flow cytometry and FACS, retrieved biofilm cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD FACSAria IIIu (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using BD FACSDiva software v 8.0.3 (BD Biosciences) for general operation. GFP was excited by a 488 nm laser (20 mW) and detected on a 530/30 nm bandpass filter. The mCherry signal was excited by a 561 nm laser (50 mW) and detected on a 610/20 nm bandpass filter. Axenic overnight cultures for each strain, including the corresponding non-fluorescent strain, were used as controls to construct the gating strategy for cell sorting and PMT voltage settings. Sorting samples were diluted in 1x PBS until reaching ~2500 events/s. Counting was done by recording 100,000 events at a flow rate of ~10 µl/min. Thresholds on the forward scatter were kept at 200, with an “AND” threshold on the side scatter kept at 200, and the minimum threshold for both. An 85 µm nozzle was used; for sorting in 96-well plates, the “single cell” sort precision was used, whereas for sorting in 5 ml round-bottom tubes, the “purity” sort precision was used.

For cell sorting, the aim was to sort out 100,000 cells of either P. brenneri or P. defluvii using bulk sorting followed by plating onto Congo Red TSA plates. Because of the low amount of P. defluvii during the 18-day experiment, if the number of sorted cells was below 20,000 after half an hour of sorting, additional single-cell sorting into 96-well plates harboring 230 µl of TSB media was performed. In both cases, plates containing sorted cells were incubated for 48 h.

Phenotypic analysis

The phenotypic screening was performed on sorted and plated P. defluvii and P. brenneri cells, previously checked for fluorescence with a transilluminator after a 48-h incubation. Single random colonies were picked with a toothpick and inoculated into a 96-well plate containing 230 µl TSB. This was done for three biological replicates for each combination at each time point for either P. defluvii or P. brenneri. This resulted in approximately 12,000 colonies that were isolated and screened in a total of 120 96-well microtiter plates for variant screening. After incubation at 24 °C, fluorescence was again confirmed with transillumination. The microtiter plates were stored at −80 °C after adding glycerol to 20%. The variant’s screening was done with a 96-pin replicator, and a small drop from each well was added to the Congo red square plates. The plates were incubated for 48 h, and selected P. defluvii variants were re-streaked twice to distinguish stable phenotypes.

Metagenomic analysis of P. defluvii and P. brenneri populations and sequencing of individual clones

Metagenomic analysis and genome sequencing of isolated variants were performed using the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform (University of Pittsburgh). For the metagenomics samples, 30 µl were collected from each well with cultures started from one sorted cell in the microtiter plates before they were pooled together in one tube for each single plate and frozen at −20 °C. The DNA was extracted as previously described and sent for sequencing with a sequence depth of at least 1 Gbps per sample. Six samples from day 18 were analyzed to estimate the general variance of the genomes in single-species and more complex biofilm communities for either P. defluvii or P. brenneri. For whole-genome sequencing of individual clones of selected variants, genomic DNA was extracted from two phenotypic variants of P. brenneri and seven P. defluvii variants from day 10 of the experimental evolution experiment, using DNeasyR Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sent for sequencing at the Microbial Genome Sequencing Center, MiGS. The samples were sequenced on a NextSeq 2000 platform utilizing Illumina DNA library preparations. Analysis of variants and metagenomics samples was performed with breseq (v0.35.0) to call variants with or without the –p flag, respectively61, against P. defluvii and P. brenneri (NCBI accessions CP123067.1 and CP122540.1, respectively)48. Mutations detected between our ancestral strains and the reference genomes were not considered. Furthermore, a cut-off threshold of 5% was used for the metagenomic analysis. Function predictions in Table S3 were assigned by blasting the gene sequences in the Pseudomonas Genome database62 using Pseudomonas sp. HLS-6 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 as references.

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy

The second 3D model slides were transferred for staining and fixation, enabling examination of the spatial structure. For general biofilm staining, 50 μl of 50 µM solution (1x PBS) of SYTO40 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) was added directly to the slide and incubated for 30 min at RT in the dark. The SYTO40 stain was washed off by dipping the slide three times in 2 ml 1x PBS and letting it dry at RT. The dry biofilm slide was fixated for 15 min at 37 °C in a 2 ml formalin solution containing ~4% formaldehyde. The slides were washed twice in 2 ml 1x PBS and dried at RT. To stain the cell wall of B. thuringiensis, samples were stained for 2 h at 4 °C with 50 μl of Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) lectin Alexa-647 conjugated fluorochrome (10 μg/ml, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA). The stain was removed by washing three times in 2 ml 1x PBS, followed by drying at RT. The samples were embedded with Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) mounting medium by heating the Mowiol solution for 10 min to 50–60 °C and adding a 15–20 μl drop on a coverslip. The slide was placed upside down into the medium and left to dry.

Six different positions were recorded for each biofilm slide using an inverted confocal laser-scanning microscope LSM 800 (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany). Fluorescence images were captured with a 63x/1.4 numerical aperture oil objective. Z-stacks were recorded with the following excitation wavelengths: 668 nm for Alexa-Fluor 647, 561 nm for mCherry, 488 nm for GFP, and 405 nm for SYTO40. PCC analysis of the community, based on the Z-stack images and design algorithm, was performed as previously described11.

Growth curves in liquid media

Briefly, strains were cultured overnight in liquid TSB medium. The following day, 1:100 dilutions of these cultures were prepared in fresh TSB and used to inoculate 96-well plates, with three biological and three technical replicates per strain. Growth was monitored over 24 h at 24 °C with double orbital shaking at 282 rpm, and OD600 measurements were taken every 10 min. Growth parameters were calculated using the R package Growthcurver63.

Statistical analysis and software

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.2.3 (403)). A two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (α = 0.05) was used in the data from Fig. 2a for statistical analysis of CFUs. To assess differences in the proportions of P. defluvii and P. brenneri across microbial combinations and over time, we performed a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (α = 0.05) to identify significant differences. A one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (α = 0.05), using the ancestor combination (PD: PB) as the control, was applied to the data in Fig. 5a. For CFU counts in Fig. 5b, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (α = 0.05) was performed. Unpaired t-tests were conducted to compare growth rate and generation time between strains (α = 0.01). Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software. Figures were designed with Inkscape, and Fig. 1 was created with BioRender.com.

Data availability

All sequencing data are available at NCBI BioProject accession number PRJNA1098242 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1098242) (SRA: SRP500601). The authors declare that all materials described in this study, including relevant raw data, will be freely available for noncommercial purposes, without breaching participant confidentiality.

References

Flemming, H. C. et al. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 247–260 (2019).

Boles, B. R. et al. Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16630–16635 (2004).

Zhang, Q. G. et al. Coevolution between cooperators and cheats in a microbial system. Evolution 63, 2248–2256 (2009).

Poltak, S. R. et al. Ecological succession in long-term experimentally evolved biofilms produces synergistic communities. ISME J. 5, 369–378 (2011).

Ponciano, J. M. et al. Evolution of diversity in spatially structured Escherichia coli populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6047–6054 (2009).

Flemming, H. C. et al. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633 (2010).

Lee, K. W. et al. Interspecific diversity reduces and functionally substitutes for intraspecific variation in biofilm communities. ISME J. 10, 846–857 (2016).

Rendueles, O. et al. Multi-species biofilms: How to avoid unfriendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 972–989 (2012).

Elias, S. et al. Multi-species biofilms: living with friendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 990–1004 (2012).

Sadiq, F. A. et al. Trans-kingdom interactions in mixed biofilm communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46, fuac024 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Micro-scale intermixing: a requisite for stable and synergistic co-establishment in a four-species biofilm. ISME J. 12, 1940–1951 (2018).

Sadiq, F. A. et al. Dynamic social interactions and keystone species shape the diversity and stability of mixed-species biofilms—an example from dairy isolates. ISME Commun. 3, 118 (2023).

Hansen, S. K. et al. Evolution of species interactions in a biofilm community. Nature 445, 533–536 (2007).

Madsen, J. S. et al. Coexistence facilitates interspecific biofilm formation in complex microbial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2565–2574 (2016).

Røder, H. L. et al. Interspecies interactions reduce selection for a biofilm-optimized variant in a four-species biofilm model. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 11, 835–839 (2019).

Røder, H. L. et al. Enhanced bacterial mutualism through an evolved biofilm phenotype. ISME J. 12, 2608–2618 (2018).

McElroy, K. E. et al. Strain-specific parallel evolution drives short-term diversification during Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E1419–E1427 (2014).

Traverse, C. C. et al. Tangled bank of experimentally evolved Burkholderia biofilms reflects selection during chronic infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E250–E259 (2013).

Henriksen, N. et al. Biofilm cultivation facilitates coexistence and adaptive evolution in an industrial bacterial community. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 8, 59 (2022).

Trampari, E. et al. Exposure of Salmonella biofilms to antibiotic concentrations rapidly selects resistance with collateral tradeoffs. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 3 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Acceleration of emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance in connected microenvironments. Science 333, 1764–1767 (2011).

Periasamy, S. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 exopolysaccharides are important for mixed species biofilm community development and stress tolerance. Front. Microbiol. 6, 851 (2015).

Nair, H. A. S. et al. Carbon starvation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms selects for dispersal insensitive mutants. BMC Microbiol. 21, 255 (2021).

Lee, K. W. et al. Biofilm development and enhanced stress resistance of a model, mixed-species community biofilm. ISME J. 8, 894–907 (2014).

Natan, G. et al. Mixed-species bacterial swarms show an interplay of mixing and segregation across scales. Sci. Rep. 12, 16500 (2022).

Mitri, S. et al. Social evolution in multispecies biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10839–10846 (2011).

Amador, C. I. et al. Evolution of genotypic and phenotypic diversity in multispecies biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 118 (2025).

Cooper, V. S. Experimental evolution as a high-throughput screen for genetic adaptations. mSphere 3, e00121–18 (2018).

Cooper, V. S. et al. Parallel evolution of small colony variants in Burkholderia cenocepacia biofilms. Genomics 104, 447–452 (2014).

Thompson, J. D. Phenotypic plasticity as a component of evolutionary change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 6, 246–249 (1991).

Webb, J. S. et al. Bacteriophage and phenotypic variation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 186, 8066–8073 (2004).

Kirov, S. M. et al. Biofilm differentiation and dispersal in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microbiology 153, 3264–3274 (2007).

Koh, K. S. et al. Phenotypic diversification and adaptation of Serratia marcescens MG1 biofilm-derived morphotypes. J. Bacteriol. 189, 119–130 (2007).

Penesyan, A. et al. Rapid microevolution of biofilm cells in response to antibiotics. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 5, 34 (2019).

Penesyan, A. et al. Three faces of biofilms: a microbial lifestyle, a nascent multicellular organism, and an incubator for diversity. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 80 (2021).

Lawrence, D. et al. Species interactions alter evolutionary responses to a novel environment. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001330 (2012).

Scheuerl, T. et al. Bacterial adaptation is constrained in complex communities. Nat. commun. 11, 754 (2020).

Lind, P. A. et al. Experimental evolution reveals hidden diversity in evolutionary pathways. eLife 4, e07074 (2015).

Hickman, J. W. et al. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14422–14427 (2005).

Römling, U. et al. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77, 1–52 (2013).

Díaz-Salazar, C. et al. The stringent response promotes biofilm dispersal in Pseudomonas putida. Sci. Rep. 7, 18055 (2017).

Jiménez-Fernández, A. et al. The c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase BifA regulates biofilm development in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 7, 78–84 (2015).

Lichtenberg, M. et al. Cyclic-di-GMP signaling controls metabolic activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Rep. 41, 111515 (2022).

Tolker-Nielsen, T. et al. Spatial organization of microbial biofilm communities. Microb. Ecol. 40, 75–84 (2000).

Decho, A. W. Chemical communication within microbial biofilms: chemotaxis and quorum sensing in bacterial cells. In Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances: Characterization, Structure and Function (eds Wingender, J. Neu, T. R. & Flemming, H.-C.) 155–169 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1999).

Kim, W. et al. Importance of positioning for microbial evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E1639–E1647 (2014).

Liu, W. et al. Interspecific bacterial interactions are reflected in multispecies biofilm spatial organization. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1366 (2016).

Maccario, L. et al. Draft genomes of seven isolates from Danish wastewater facilities belonging to Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Pseudochrobactrum, Brevundimonas, and Pandoraea. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 12, e0052923 (2023).

Tan, D. et al. High cell densities favor lysogeny: induction of an H20 prophage is repressed by quorum sensing and enhances biofilm formation in Vibrio anguillarum. ISME J. 14, 1731–1742 (2020).

Römling, U. et al. Multicellular and aggregative behaviour of Salmonella typhimurium strains is controlled by mutations in the agfD promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 28, 249–264 (1998).

Olsen, N. M. C. et al. Priority of early colonizers but no effect on cohabitants in a synergistic biofilm community. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1949 (2019).

Choi, K.-H. et al. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2, 443–448 (2005).

Kessler, B. et al. A general system to integrate lacZ fusions into the chromosomes of gram-negative eubacteria: regulation of the Pm promoter of the TOL plasmid studied with all controlling elements in monocopy. Mol. Gen. Genet. 233, 293–301 (1992).

Sundberg, C. et al. 454 pyrosequencing analyses of bacterial and archaeal richness in 21 full-scale biogas digesters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 612–626 (2013).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet 17, 3 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

McMurdie, P. J. et al. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Davis, N. M. et al. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome 6, 226 (2018).

Deatherage, D. E. et al. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol. Biol. 1151, 165–188 (2014).

Winsor, G. L. et al. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D646–D653 (2016).

Sprouffske, K. et al. Growthcurver: an R package for obtaining interpretable metrics from microbial growth curves. BMC Bioinform. 17, 172 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge Anette Løth and Ayoe Lüchau for excellent technical assistance and Magnus Søndergaard and Jens Hedelund Madsen for technical assistance in testing prototypes of the 3D-printed flow model. H.L.R. acknowledges funding from the Villum Foundation grant (no. 34434). V.S.C. is supported in part by NIH award U19AI158076.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.R. conceptualized the study and developed the methodology together with V.S.C. H.L.R., I.S.K., C.I.A., L.M., and A.K.O. were responsible for data acquisition. R.E. performed the data analysis and wrote the original draft with inputs from H.L.R., C.I.A., L.M., I.S.K., A.K.O., and V.S.C. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.L.R. and V.S.C. supervised the project and acquired funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Espinosa, R., Kramer, IS., Amador, C.I. et al. Competition between Pseudomonas species constrains ecological diversification in polymicrobial biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 234 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00863-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00863-y