Abstract

The viromes of maternal peripheral blood (MPB) and umbilical cord blood (UCB) provide crucial insights into mother-to-infant transmission and the associations of maternal health with early-life viral colonization. Using viral metagenomic sequencing of 433 MPB and 426 UCB samples, we assembled 57 near-complete genomes from four core viral families (Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, Parvoviridae, Flaviviridae). MPB viromes were primarily composed of bacteriophages and Anelloviridae, while UCB exhibited relatively increased abundances of Parvoviridae and Human Endogenous Retroviruses. Maternal disease correlated with reduced α-diversity in MPB but elevated richness in UCB. β-Diversity varied significantly with both health status and sample type. Differential abundance analysis identified health-specific signatures, including enriched Parvoviridae in diseased UCB. Phylogenetic evidence indicated possible vertical transmission and high genetic diversity among identified viruses. This study systematically characterizes the maternal–fetal blood virome and reveals associations between maternal health status and viral community structure, providing a basis for understanding early-life viral exposure and informing future preventive strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) forms a critical bridge between the maternal and fetal circulatory systems during pregnancy. Beyond its well-established role in mediating nutrient and gas exchange, growing evidence suggests UCB may also serve as a conduit for early microbial and viral exposure. This distinctive biological compartment captures a snapshot of the perinatal virome, offering a unique window into mother-to-infant viral transmission, initial microbial colonization, and the developing neonatal immune system1,2. Notably, emerging research on the cord blood virome is shedding light on its potential role in early-life viral exposure and the subsequent immunological consequences for the neonate, as well as its implications for maternal-fetal immune crosstalk3.

Physiologically, UCB constitutes a specialized environment enriched with hematopoietic cells, immunomodulatory factors, and signaling molecules4. In recent years, metagenomic analyses have progressively overturned the traditional “sterile womb” hypothesis, demonstrating that blood carries complex viral communities comprising both eukaryotic viruses and bacteriophages, whose composition often reflects the host’s health status2. Among the viral families consistently identified in UCB are Herpesviridae, Anelloviridae, and Papillomaviridae5,6. It should be noted that not all of these families undergo true latency; while Herpesviridae can establish latent infections, Anelloviridae typically cause persistent infections. Viruses within these families can persist in various states and may participate in the developmental process of the fetal immune system. Particularly compelling is the detection of bacteriophage DNA in human cord blood at delivery, providing molecular evidence of in utero viral exposure and supporting the possibility of vertical viral transmission7. Maternal viromes may also indirectly modulate fetal immune development by shaping the intrauterine environment. Dynamic correlations between maternal and infant viral communities have been observed across body sites, including the gut, before and after birth. Moreover, the abundance of certain blood-borne viruses such as Anelloviridae has been correlated with immunological status and inflammatory markers, underscoring their potential utility as biomarkers for immune monitoring8. Although viral populations in maternal plasma, vaginal secretions, and other sites have been increasingly mapped9, systematic metagenomic comparisons between paired MPB and UCB samples remain limited10. Perhaps more importantly, the influence of maternal health status on the blood virome and its implications for vertical transmission have not been thoroughly elucidated. Our study seeks to address these unanswered questions by exploring mother–infant virome dynamics and their health relevance11.

Strong epidemiological evidence links maternal viral infection and immune activation during pregnancy to adverse outcomes, including preterm birth, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, and neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring12,13,14. Even without direct fetal infection, viral presence can disrupt the intrauterine milieu by provoking placental or fetal inflammatory responses. The composition and dynamics of the cord blood virome may thus reflect maternal health status, including immune competence, co-infections, and microbial stability, highlighting its potential as a biomarker for assessing infant exposure and developmental risk6. Profiling the cord blood virome metagenomically remains technically demanding, primarily due to low viral nucleic acid abundance and high background host DNA. These challenges necessitate optimized purification protocols and deep-sequencing strategies.

Metagenomic sequencing powerfully captures the complete genetic landscape of all microorganisms, including viruses, within biological samples like UCB15. Unlike culture-dependent or PCR-based methods, metagenomics requires no prior knowledge of viral sequences, enabling unbiased detection of both known and novel viruses16. This advantage proves essential in UCB studies, where viral loads are typically low and many viruses remain uncultivable or poorly characterized17. The application of metagenomic approaches allows for broad profiling of eukaryotic viruses and bacteriophages in UCB. Recent bioinformatic advances—including refined machine learning algorithms—have substantially improved the prediction of virus–host interactions and enhanced the accuracy of viral genome assembly and taxonomic classification18. Together, these developments establish metagenomic sequencing as an indispensable tool for characterizing the UCB virome and illuminating its role in maternal–infant health.

In this study, we leveraged viral metagenomic strategies to systematically analyze the viromes of paired MPB and UCB samples. Combining deep sequencing with advanced bioinformatic pipelines, we compared viral community structures and diversity patterns between maternal peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood. Phylogenetic investigations further elucidated evolutionary relationships among key viral families and assessed their potential for cross-generational transmission. Our findings offer new insights into the architecture of the perinatal virome and uncover potential mechanisms governing vertical virus transmission.

Results

Viral metagenomic overview

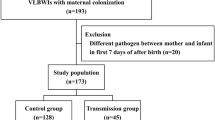

To comprehensively profile the blood virome in maternal and umbilical cord blood samples, we collected 433 qualified maternal peripheral blood (MPB) and 426 paired umbilical cord blood (UCB) specimens following quality control assessment. These 7 MPB samples lacking UCB pairs were pooled into a single sequencing library. In total, 175 sequencing libraries were constructed and analyzed on the Illumina NovaSeq platform, generating 3,583,289,218 raw reads, ranging from 193,972 to 116,998,298 reads per library, with an average GC content of 44.7%. All sequences were demultiplexed, de novo assembled, and aligned against the GenBank non-redundant protein database using BLASTx to identify viral reads. Altogether, 5,208,976 viral genomic reads, ranging from 234 to 391,377 per library, were identified as belonging to known eukaryotic viruses. Based on maternal health status and sample type, the 175 libraries were classified into four groups: the Maternal Peripheral Blood Healthy group (n = 37, Blood01–Blood37), the Maternal Peripheral Blood Disease group (n = 51, Blood38–Blood88), the Umbilical Cord Blood Healthy group (n = 37, Blood89–Blood125), and the Umbilical Cord Blood Disease group (n = 50, Blood126–Blood175). The Disease group included individuals diagnosed with a single, specific pregnancy complication, namely Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (n = 13), Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy (n = 10), Anemia in pregnancy (n = 9), or Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (n = 19), where n indicates the number of maternal peripheral blood sequencing libraries. Maternal health status determined the classification of all groups. Detailed metadata for each library are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Through sequence assembly, a total of 57 distinct complete or near-complete viral genomes (CDS) were identified in this study. These genomes were classified into four defined viral families. Among them, 51 originated from maternal peripheral blood and 6 from umbilical cord blood. These included DNA viruses from Anelloviridae (n = 41, ssDNA), Circoviridae (n = 6, ssDNA), and Parvoviridae (n = 7, ssDNA), and RNA viruses from Flaviviridae (n = 3, ssRNA). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using amino acid or nucleotide sequences from the most conserved genomic regions, specifically ORF1 for Anelloviridae, the Rep protein for Circoviridae, the NS1 protein for Parvoviridae, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain for Flaviviridae.

Composition of the virome in maternal and umbilical cord blood

At the family level, viral reads were assigned to 37 families, including 22 DNA and 15 RNA virus families. The overall taxonomic profiles are shown in a circular heatmap (Supplementary Fig. 1). Relative abundance analyses revealed key structural and compositional patterns across libraries (Fig. 1a, b). Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae were consistently dominant. Anelloviridae were markedly higher in MPB than in UCB. Pie charts (Fig. 1c) show that in maternal peripheral blood (MPB), Siphoviridae constituted the largest proportion (26.05%), followed by Myoviridae (18.63%), Podoviridae (15.69%), and Anelloviridae (13.24%); together these families dominated the MPB virome, with Flaviviridae also present at notable levels (6.69%). In UCB, Siphoviridae remained most abundant (26.5%), trailed by Myoviridae (21.32%) and Podoviridae (17.17%). Human Endogenous Retroviruses were substantially enriched in UCB (11.6%). Conversely, Anelloviridae were frequently detected in MPB but scarce in UCB, suggesting confinement mainly to maternal circulation. Flaviviridae were present in MPB (6.69%) but not significantly detected in UCB. Although Parvoviridae occurred at low abundance in MPB (1.02%), their relative abundance increased in UCB (1.38%), suggesting either neonatal-specific enrichment or distinct structural organization of the UCB virome. UpSet analysis (Fig. 1d) identified 374 viral species across all groups. The UCB-Disease group exhibited the highest species richness (n = 86), substantially surpassing the other three groups. A total of 111 viral species were shared among all groups, representing a core virome. Notably, only a single viral species was uniquely shared between the MPB-Healthy and UCB-Healthy groups. This exclusively shared virus was identified as Gokushovirinae Bog1183_53, a member of the Microviridae phage family. In contrast, a significantly greater number of species (n = 15) were uniquely shared between the MPB-Disease and UCB-Disease groups. These results suggest that maternal health status may be associated with specific viral distribution patterns and could potentially influence mother-infant viral transmission characteristics. Collectively, this study reveals potential relationships between maternal health status and the structure of the cord blood virome, as well as viral exchange features between mothers and their infants.

a Comparison of community composition at the viral family level in the maternal and umbilical cord blood samples. The stacked bar chart shows the relative abundance of the top 11 viral families in maternal peripheral blood and neonatal umbilical cord blood, with the remaining viral families grouped under “others”. Detailed information on the number of samples pooled per library is provided in Supplementary Data 1. b Based on maternal health status and sample type, the bar chart shows the top 10 viral families in relative abundance across four groups, with the remaining viral families grouped under “others”. c Pie charts showing the relative abundance composition of viral families in maternal peripheral blood (MPB) and umbilical cord blood (UCB). Only the top 11 viral families by read count are listed, with the remaining low-abundance viral families grouped under “others”. d UpSet plot showing the number of shared viral species across the four groups. Filled dots with connected vertical lines represent intersections, and unfilled dots in light gray represent sets that do not belong to the intersections. The vertical bars represent the number of viral species within the intersections, and the horizontal bars represent the total number of viral species in each group.

Virome diversity analysis of maternal and umbilical cord blood

To evaluate species richness and sampling completeness, we constructed rarefaction and accumulation curves. The rarefaction curves approached saturation with increasing sequencing depth, suggesting sufficient sequence coverage (Supplementary Fig. 2). The percentage contribution of viral sequence reads from each library is shown in a pie chart (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similarly, the species accumulation curves plateaued as sample size increased, confirming representative sampling (Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, more than 300 viral species were identified across all libraries. We compared α-diversity among the four groups using Shannon and Simpson indices (Fig. 2a). The MPB-Disease group exhibited significantly lower Shannon and Simpson indices compared to MPB-Healthy (P < 0.05). Between UCB-Healthy and UCB-Disease, Shannon diversity differed significantly (P < 0.05), though the Simpson index did not reach significance. Under healthy conditions, α-diversity did not differ significantly between MPB-Healthy and UCB-Healthy. In contrast, under disease conditions, both Shannon and Simpson indices were significantly higher in UCB-Disease than in MPB-Disease (P < 0.001), indicating enhanced virome diversity in cord blood relative to maternal blood in the context of maternal disease. β-diversity was assessed using PCoA based on Bray–Curtis distances, which revealed clear separation among groups (Fig. 2b). MPB samples showed greater dispersion than UCB samples, and sample type (MPB vs. UCB) significantly influenced community structure (P = 0.001). Maternal health status also markedly affected viral community composition (P = 0.001). Multi-group comparisons confirmed highly significant β-diversity differences among all four groups. These results indicate that both sample source and maternal health status interact to shape viral β-diversity.

a Alpha diversity analysis. The alpha diversity of maternal and umbilical cord blood samples across four groups was assessed using the Shannon and Simpson indices, with the significance of intergroup differences tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. In the box plots, the horizontal line within the box represents the median, the upper edge of the box corresponds to the 75th percentile (Q3, upper quartile), and the lower edge corresponds to the 25th percentile (Q1, lower quartile). Statistical significance thresholds: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. b Beta diversity analysis. Beta diversity analysis based on Bray-Curtis distances, visualized through principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). The percentages of variance explained by PCoA1 and PCoA2 are indicated on the respective axes. Ellipses represent the 95% confidence intervals for each group.

Differential virome profiles in maternal and umbilical cord blood under healthy and diseased conditions

STAMP analysis is widely used for detecting metagenomic differences and provides confidence intervals for biological interpretation19. STAMP identified significant differences in viral abundance between healthy and diseased groups at both the family and species levels.

In MPB, 17 viral families exhibited significant differences (Fig. 3a). Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Poxviridae were enriched in MPB-Healthy, while Siphoviridae and Podoviridae were more abundant in MPB-Disease. At the species level (Fig. 3b), nearly 40 species exhibited significant differences, with the majority being enriched in MPB-Healthy. Notably, Escherichia phage Lambda and Enterobacteria phage O276 (Siphoviridae) showed elevated abundance in MPB-Disease. In UCB, 23 families demonstrated differential abundance (Fig. 3c). Human Endogenous Retroviruses, Poxviridae, Herpesviridae, among others, were enriched in UCB-Healthy, whereas Myoviridae, Podoviridae, Virgaviridae, and several other viral families were predominated in UCB-Disease. Interestingly, Parvoviridae were significantly more abundant in UCB-Disease—a pattern contrasting with MPB—suggesting possible vertical transmission and fetal replication20. At the species level (Fig. 3d), 80 taxa differed significantly, most being enriched in the disease group. Notably, the BeAn 58058 virus, an unclassified virus within the family Poxviridae was relatively enriched in both healthy MPB and UCB samples. This unique pattern reveals a previously unrecognized ecological distribution of viruses at the maternal-fetal interface, the underlying mechanisms of which warrant further investigation.

a, b STAMP analysis of differences in relative abundance of viral families and viral species between MPB-Healthy and MPB-Disease. c, d STAMP analysis of differences in relative abundance of viral families and viral species between UCB-Healthy and UCB-Disease. For all panels, differences were tested using a two-sided Welch’s t-test, and p-values were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini-Hochberg method).

To assess the influence of maternal health on viral community structure across taxonomic ranks, viromes were compared at class, order, and family levels. Among 21 detected viral classes, five differed significantly (fold change ≥ 2; Supplementary Data 3). Flasuviricetes were predominant in the healthy group (7.87%; 102.28-fold higher than diseased), with Herviviricetes and Pokkesviricetes also enriched. In contrast, Laserviricetes and Monjiviricetes were more abundant in the diseased group. Co-occurrence analysis revealed widespread negative correlations among seven classes, indicating competitive interactions (Supplementary Fig. 5). At the order level, six orders differed significantly (Supplementary Data 3). Although Caudovirales dominated both groups (healthy: 58.78%; diseased: 67.29%), other orders varied considerably. Chitovirales, Herpesvirales, and Amarillovirales were enriched in healthy samples, whereas Zurhausenvirales, Halopanivirales, and Mononegavirales were more abundant in diseased samples. Network analysis showed predominantly negative correlations, except for a positive association between Picornavirales and Martellivirales, suggesting distinct interaction dynamics relative to class-level patterns (Supplementary Fig. 6). At the family level, 12 of 52 families exhibited significant differences (Supplementary Data 3). Thirteen families exceeded 1% relative abundance in the healthy group, with Flaviviridae (9.14%), Poxviridae (2.34%), and Herpesviridae (0.53%) being most prominent. In the diseased group, Papillomaviridae and Sphaerolipoviridae were markedly enriched (0.06% each), showing > 20-fold increases. In contrast to the competitive relationships observed at higher taxonomic levels, family-level networks revealed positive correlations among several families (e.g. Picornaviridae with Virgaviridae and Iridoviridae), suggesting potential cooperative ecological interactions (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Based on 175 metagenomic libraries, samples were categorized into four groups by maternal health status and sample type: MPB-Healthy, MPB-Disease, UCB-Healthy, and UCB-Disease. Viral family composition within each group is depicted in pie charts (Fig. 4a, b). Human Endogenous Retroviruses were substantially enriched in UCB compared to MPB, implying a possible role in neonatal virome establishment and maternal–fetal transmission. Flaviviridae abundance varied with maternal health status, being higher in MPB-Healthy but reduced in MPB-Disease and UCB samples. Conversely, Parvoviridae consistently increased in diseased groups across sample types, indicating a strong association with maternal–infant health and suggesting potential utility as a disease biomarker, though causal mechanisms remain unclear.

To further clarify maternal–infant differences and possible transmission routes, we analyzed four viral families with fully assembled genomes—Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, Parvoviridae, and Flaviviridae—evaluating their distribution in MPB and UCB and the influence of maternal health status. A paired analysis of 87 matched MPB–UCB samples (excluding Library 88, which lacked a UCB pair) was conducted. After normalizing raw read counts for library size and applying Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, Anelloviridae (p < 0.0001), Circoviridae (p < 0.0001), and Flaviviridae (p < 0.05) were significantly more abundant in MPB than UCB, whereas Parvoviridae showed the opposite trend, with higher UCB abundance (p < 0.001). Stratifying the pairs into healthy (n = 37) and diseased (n = 50) groups revealed consistent MPB enrichment of Anelloviridae in both groups (p < 0.0001). Circoviridae also displayed MPB enrichment in both subgroups, with a stronger effect in healthy (p < 0.0001) than diseased (p < 0.01) pairs. Parvoviridae exhibited a striking reversal: in healthy pairs, it was more abundant in MPB (p < 0.0001), but in diseased pairs, UCB abundance was significantly higher (p < 0.01). Flaviviridae showed MPB enrichment overall (p < 0.05) and in the healthy group (p < 0.001), but no significant difference was found in diseased pairs (p > 0.05). These results suggest that maternal health status may modulate placental barrier function, leading to increased UCB abundance of Circoviridae and Parvoviridae under disease conditions, in contrast to the consistently MPB-enriched Anelloviridae (Fig. 5a–d).

a–d Abundance differences of Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, Parvoviridae, and Flaviviridae in MPB and UCB are shown. Based on 87 maternal-infant paired samples (excluding Library 88, which lacked a UCB pair, further divided into healthy subgroups n = 37 and disease subgroups n = 50), the raw read counts were normalized and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.5 software with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess the differences between groups.

Anelloviruses found in the study

Anelloviridae are small, nonenveloped viruses with circular single-stranded negative-sense DNA genomes ranging from 1.6−3.9 kb. Viral particles exhibit icosahedral capsid symmetry, with diameters of 18–30 nm, and lack a lipid envelope21. To date, three genera within this family are known to infect humans: Alphatorquevirus (including torque teno virus, TTV), Betatorquevirus (including torque teno mini virus, TTMV), and Gammatorquevirus (including torque teno midi virus, TTMDV). These viruses are ubiquitously detected in human plasma and represent a core component of the blood virome in healthy individuals6. A hallmark genomic feature of this family is the presence of a single ORF1, which encodes the capsid protein containing a conserved jelly-roll fold. Because ORF1 sequences exhibit both cross-genus conservation and genus-level specificity, and because their features are directly linked to viral taxonomy, ORF1 has become the principal genetic marker for phylogenetic analyses of Anelloviridae.

Anelloviridae are widely distributed in the human population, with an estimated adult infection rate of ~90%. They can establish persistent colonization in multiple organs such as the liver and kidney, as well as in body fluids including blood and urine. Within the blood virome of healthy individuals, Anelloviridae account for >70% of the total viral community, making them one of the most abundant viral groups in humans22. Large-scale viromic studies have revealed their extraordinary genetic diversity, frequent recombination events, and worldwide distribution, with hundreds of distinct lineages detectable even within healthy individuals23. Importantly, both the viral load and diversity of Anelloviridae are closely associated with host immune function. In immunocompromised populations, such as organ transplant recipients and HIV-1–infected patients, viral levels are typically elevated. This observation suggests that Anelloviridae, particularly TTV, may serve as surrogate markers of immune competence and could be useful for monitoring maternal immune status during pregnancy24,25.

Based on metagenomic data from MPB and UCB, we analyzed the distribution and vertical transmission potential of Anelloviridae. Assembly recovered 41 complete ORF1 sequences, and their taxonomic assignments revealed marked differences across genera and sample sources. At the genus level, 12 sequences clustered within Alphatorquevirus, while 29 belonged to Betatorquevirus/Gammatorquevirus. With respect to sample origin, only one ORF1 sequence was derived from UCB, whereas the remaining 40 sequences originated from MPB. This result confirms the strong enrichment of Anelloviridae within maternal circulation and reveals a characteristic composition, with Betatorquevirus/Gammatorquevirus accounting for 70.7% and Alphatorquevirus representing 29.3%. This pattern is consistent with Timmerman et al., who observed that Betatorquevirus/Gammatorquevirus became dominant in maternal serum and breast milk 6 months postpartum, suggesting that MPB at delivery may already be shifting toward dominance by Betatorquevirus/Gammatorquevirus26.

From 175 MPB and UCB libraries, a total of 41 Anelloviruses were assembled, including 11 complete circular genomes. Genome sizes ranged from 1920 to 2939 bp, with representative circular structures illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 8. These genomes exhibited a conserved organization of ORF1, ORF2, and ORF3. BLASTx analysis showed that the amino acid sequences of the 41 viruses shared 67.36%–99.11% identity with previously deposited sequences in GenBank. Considerable genetic heterogeneity was observed, as multiple Anelloviruses detected within the same library were not completely identical. Subsequently, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on ORF1 amino acid sequences (Fig. 6a). The phylogenetic analysis included 86 publicly available reference sequences to provide taxonomic context (see Supplementary Data 2 for accession numbers). The 41 Anelloviruses clustered into three distinct clades, containing 12, 24, and 5 viruses, respectively. To further investigate genetic relationships and evolutionary divergence among the three genera of Anelloviridae, whole-genome similarity analyses were conducted (Fig. 6b). Pairwise alignment of all genomes revealed clear boundaries among Alphatorquevirus, Betatorquevirus, and Gammatorquevirus, with no evidence of cross-genus clustering or overlap. Notably, multiple Anelloviruses from different genera were identified in library Blood41, and their sequence similarities strictly adhered to genus-specific boundaries. This finding highlights the enrichment and considerable genetic diversity of Anelloviridae in maternal and umbilical cord blood.

a Phylogenetic tree constructed based on the amino acid sequences of ORF1 and visualized with iTOL. Names in red indicate sequences obtained in this study. The scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. b Whole-genome sequence similarity analysis of Anelloviruses assembled from individual libraries. The analysis was performed on near-complete genomes derived from each specific library, illustrating the genetic relationships and clear demarcations among the genera Alphatorquevirus, Betatorquevirus, and Gammatorquevirus.

Circoviruses found in the study

Circoviridae, a member of the CRESS (circular Rep-encoding single-stranded) DNA virus family, has attracted considerable attention in virological research. Viruses within this family possess circular, covalently closed single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genomes, typically ranging from 1.7 to 2.4 kilobases (kb) in length27. The genomes exhibit a ambisense organization, containing two major open reading frames (ORFs): the replication-associated protein (rep) gene and the capsid protein (cap) gene28. This streamlined genomic architecture underlies their ability to efficiently replicate and adapt to diverse hosts. According to the classification criteria established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), Circoviridae is divided into two genera: Circovirus and Cyclovirus29. Species demarcation within these genera is primarily based on whole-genome nucleotide sequence identity, with sequences sharing <80% identity typically classified as distinct species27.

In this study, six Circoviridae sequences were recovered from maternal and umbilical cord blood samples, including five sequences assigned to Circovirus and one to Cyclovirus. Genome lengths ranged from 657 to 1,969 base pairs (bp), with an average GC content of 43.81%. The observed genus-level distribution aligns with prior knowledge of Circoviridae host range and epidemiological characteristics: Circovirus members are more commonly reported in mammalian hosts, including humans, whereas Cyclovirus demonstrates rapidly expanding genetic diversity and potential for cross-host transmission. However, consistent detection of Cyclovirus in defined human populations or under specific exposure conditions remains limited, emphasizing the need for further validation and integration of host exposure history in future analyses30,31.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the Rep protein (Fig. 7a) revealed that Blood41-1808 clustered with a feline-derived cyclovirus (Feline cyclovirus, GenBank accession: YP_009052458), exhibiting 84.21% amino acid identity and supporting its classification within the genus Cyclovirus. In contrast, Circovirus sequences formed four distinct clades. Blood41-54603 clustered with a parrot-derived circovirus (GenBank accession: WGL41063) with 96.22% amino acid identity, while Blood133-235 was most closely related to the integrated Rep gene of Cynopterus sphinx circular DNA virus 6 (GenBank accession: WOE49735), sharing 95.1% sequence identity. Blood50-6147 showed highest similarity to a turtle-derived circovirus (GenBank accession: WRQ56666), with 96.01% amino acid identity. Notably, Blood16-15453 and Blood104-354543, derived from maternal peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood, respectively, clustered within Cynopterus sphinx circular DNA virus 2 (GenBank accession: WOE49730) with 99% amino acid sequence identity, exhibiting highly consistent phylogenetic patterns. This result supports the possibility of mother-to-child transmission for this viral family and suggests potential phylogenetic conservation between paired samples. The phylogenetic analysis was based on an alignment of 41 publicly available reference sequences (accession numbers and details are provided in Supplementary Data 2).

a Phylogenetic tree constructed based on the amino acid sequences of the Rep protein, visualized using iTOL software. Viruses identified in this study are highlighted in red within the tree. The scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. b Pairwise comparison analysis of whole-genome sequences of Cyclovirus within the phylogenetic tree. One Cyclovirus identified in this study is highlighted in red. c Pairwise comparison analysis of whole-genome sequences of Circovirus. Circoviruses identified in this study are highlighted in red.

Pairwise whole-genome comparison of the Blood41-1808 strain revealed 40%–82.40% sequence identity with other Cyclovirus members (Fig. 7b). Within Circovirus, aside from the nearly identical Blood16-15453 and Blood104-354543, pairwise comparisons of Rep proteins from all circoviruses detected in maternal and umbilical cord blood revealed sequence identities as low as 30%, indicating a high level of genetic diversity among Circovirus genomes from these samples (Fig. 7c).

Parvoviruses found in the study

Parvoviridae comprises non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA viruses with genomes ranging from 4 to 6 kb, typically encoding two major open reading frames (ORFs), NS1 and VP1, which correspond to non-structural protein 1 and structural protein 1, respectively32. Based on molecular evolution and host specificity, Parvoviridae is currently divided into three core subfamilies: Parvovirinae, which specifically infects vertebrates; Densovirinae, primarily targeting arthropods; and Hamaparvovirinae, which infects both invertebrate and vertebrate hosts. This classification framework reflects the remarkable diversity of Parvoviridae at both the genomic and host-spectrum levels and provides a critical reference for phylogenetic, epidemiological, and functional studies of the family33. According to the latest standards, taxonomic classification within Parvoviridae relies primarily on NS1 protein sequence homology. Typically, members within the same genus share ≥35%–40% amino acid identity in NS1, and if two strains exhibit >85% NS1 sequence identity with >80% coverage, they can be considered the same species34.

In maternal–neonatal contexts, Parvoviridae has attracted considerable attention due to its potential involvement in vertical transmission and interactions with the placental barrier. Recent studies indicate that parvoviruses, particularly human parvovirus B19 (B19V), are capable of crossing the placenta to achieve mother-to-child vertical transmission. During maternal infection, B19V can traverse the placental barrier, enter the fetal circulation, and efficiently replicate in cord blood as well as fetal hematopoietic cells35. This process is primarily mediated by the recognition of P antigen (globoside) on placental and fetal cell surfaces, with higher expression levels of P antigen during early pregnancy increasing the risk of transplacental viral passage. Although the placenta generally provides a biological barrier against most pathogens, B19 infection can induce apoptosis and functional impairment of trophoblast cells, thereby weakening the barrier and facilitating maternal–fetal transmission. Furthermore, maternal B19 infection has been associated with a significantly elevated risk of adverse fetal outcomes, including anemia, hydrops fetalis, and miscarriage, underscoring the critical importance of viral monitoring and preventive measures during pregnancy36.

Based on NS1 amino acid sequences, a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Fig. 8a), which included 29 publicly available reference sequences to establish the phylogenetic framework (see Supplementary Data 2 for accession numbers). The tree shows that parvovirus sequences derived from maternal and umbilical cord blood (highlighted in red) clustered with multiple known mammalian parvoviruses. Blood145-18746 grouped with bovine parvovirus 2 (GenBank accession: QYW06847), indicating close evolutionary relatedness to cattle-derived parvoviruses. Blood18-11667, Blood133-165528, Blood19-7574, and Blood140-361998 clustered with ovine copiparvoviruses (GenBank accessions: QYW06845 and QYW06831), suggesting a potential evolutionary link between parvoviruses detected in cord blood and viruses originating from ruminants. Additionally, two sequences, Blood48-3924 and Blood84-19672, were assigned to the subfamily Densovirinae and clustered closely with two bat-derived viruses (GenBank accessions: XBS25702 and XBS26080), implying that bats may serve as hosts or reservoirs and potentially contribute to transmission to humans, including via maternal and umbilical cord blood.

a Phylogenetic tree constructed based on the amino acid sequences of the NS1 protein of parvoviruses, with sequences obtained in this study highlighted in red. b Phylogenetic tree constructed based on the nucleotide sequences of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) region of flaviviruses, with viruses identified in this study highlighted in red.

Flaviviruses found in the study

Flaviviridae is an important family of zoonotic RNA viruses, with a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of ~9–13 kb, typically containing a single open reading frame (ORF). This ORF encodes a polyprotein that is cleaved by viral and host proteases to generate structural proteins (C, prM/M, E) and nonstructural proteins (NS1–NS5). Among these, NS5 serves as the core component of the viral replication complex, exhibiting both methyltransferase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activities. It is highly conserved and plays a crucial role in viral replication and host adaptation37,38.

According to the latest classification by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), the family Flaviviridae is divided into four genera: Orthoflavivirus, Hepacivirus, Pegivirus, and Pestivirus. Orthoflavivirus primarily comprises arthropod-borne viruses, including dengue virus, yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and Zika virus, which are mainly transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks, infect humans as well as a wide range of wild animals, and constitute a major global public health threat39. Hepacivirus is dominated by hepatitis C virus, which primarily infects the human liver and can lead to chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Pegivirus infects humans and other mammals, typically causing persistent infections with relatively low pathogenicity. Pestivirus mainly infects ruminants, causing various animal diseases with significant implications for the livestock industry40.

Recent studies investigating mother-to-child transmission mechanisms of Flaviviridae have increased, particularly regarding Zika virus (ZIKV), which can cross the placental barrier, leading to fetal infection and severe congenital defects41. This highlights the ability of flaviviruses to traverse host barriers and underscores the significance of vertical transmission in viral epidemiology. In the present study, three Pegivirus sequences were assembled from maternal peripheral blood samples, while no complete flavivirus sequences were recovered from umbilical cord blood. Although Pegivirus typically establishes persistent infections, its pathogenicity remains largely unclear. Regarding vertical transmission, a retrospective study in Brazil reported that 25% of HIV-infected pregnant women were positive for human Pegivirus (HPgV), with a vertical transmission rate of 31% to neonates42. However, other reports indicate that even in cases of high maternal viremia, vertical transmission may not occur; for example, one mother displayed high HPgV levels during two pregnancies, and while placental tissues tested positive, both chorionic villi and umbilical cord blood were negative43. These observations suggest that the vertical transmission mechanisms of Pegivirus require further investigation.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the nucleotide sequences of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) region of Flaviviridae (Fig. 8b) was conducted using 27 publicly available reference sequences to establish the phylogenetic context (see Supplementary Data 2 for accession numbers). The analysis revealed that the three Pegivirus sequences assembled exclusively from maternal peripheral blood (highlighted in red) formed a distinct cluster within the genus Pegivirus, grouping with known human pegivirus reference sequences (MH746815 Human pegivirus, AF006500 Hepatitis G virus, etc.) in an independent branch. Notably, no complete Flaviviridae genomes were assembled from umbilical cord blood samples. BLASTn analysis indicated nucleotide sequence identities exceeding 90%, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship with human pegiviruses and providing a robust phylogenetic framework for further studies on the vertical transmission potential and evolutionary adaptation of Pegivirus in the maternal–fetal context.

Discussion

Utilizing high-throughput metagenomic sequencing, this study systematically profiled the viromes of 433 maternal peripheral blood and 426 umbilical cord blood samples, offering the first large-scale and comprehensive characterization of viral communities across the maternal–neonatal axis. We delineated virome diversity patterns and their associations with maternal health status, confirming the presence of complex viral assemblages in cord blood and demonstrating that their composition is influenced by both sample origin and maternal health status. Critically, the correlated viral distribution patterns observed in some mother-neonate pairs offer new perspectives for understanding the existence and dissemination characteristics of viruses across the placental interface.

Analysis of the virome composition revealed that bacteriophages, including Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae, dominated both maternal and neonatal viral communities, consistent with previous human blood virome studies44,45. These phages likely originate from gut or other microbial reservoirs and may enter systemic circulation via mucosal barriers, reflecting immune activity rather than active infection46. Notably, our data also showed a relative increase in bacteriophage abundance under maternal disease conditions, in both maternal and cord blood samples. While this trend may potentially reflect underlying microbial dysbiosis or altered host immunity, recent reports have speculated that phage dynamics could serve as a surrogate marker for disease risk or severity. However, the mechanisms driving this increase remain to be elucidated, and further studies are warranted to assess the reliability and specificity of phage-based biomarkers in perinatal contexts47. A notable observation was the relative enrichment of sequences derived from Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVs) in umbilical cord blood. This trend may hold potential biological relevance48. It should be noted, however, that due to inherent technical limitations of the analytical approach, the current data cannot determine whether these detected sequences are transcriptionally active. Furthermore, the majority of HERV elements are thought to have accumulated mutations that impair their coding capacity; thus, the detection of these sequences alone does not support the inference that intact viral particles are being produced. As remnants of ancient retroviral integration events, HERV sequences constitute ~8% of the human genome49. Some studies have suggested that they may participate in specific epigenetically regulated processes during embryonic development. Evidence also indicates that certain HERV families, such as HERV-W, may contribute—possibly through their expressed products—to processes including trophoblast fusion and syncytiotrophoblast formation during placental development50,51. In this context, the observed enrichment of HERV-derived sequences in cord blood in our study provides a basis for further investigating the potential role of these endogenous elements in the dynamic regulation of the fetal–placental interface52. Determining whether these HERV loci are transcriptionally active and elucidating their potential biological roles remain to be investigated in future studies, which should constitute important next steps. Specifically, transcriptomic approaches such as RNA-seq will be critical for this purpose.

A central observation of this work is the pronounced effect of maternal health status on the maternal–neonatal virome. Diseased mothers exhibited reduced α-diversity (Shannon and Simpson indices) in peripheral blood, likely indicative of immune dysregulation that permits dominance of certain viruses and suppresses others, thereby homogenizing the viral community. Notably, cord blood from neonates of diseased mothers displayed higher viral diversity than their maternal counterparts and sometimes even exceeded that of healthy neonate-mother pairs. This suggests a more permissive intrauterine environment under maternal disease, potentially facilitating crossing of diverse viruses across the placenta. β-diversity analysis (PCoA) clearly distinguished viral communities between health and disease groups, reinforcing maternal condition as a key determinant of virome structure. The analysis of Upset plots indicated a greater number of viral species unique to diseased mother-neonate pairs (15 species) compared to those unique to healthy pairs (1 species). STAMP analysis identified several viral families and species enriched under disease conditions, suggesting that maternal disease could potentially affect placental selectivity and might contribute to vertical transmission, thereby possibly influencing the assembly of the neonatal virome53. Notably, the BeAn 58058 virus (family Poxviridae) has been recurrently identified across distinct human anatomical compartments—demonstrating remarkable predominance in the pulmonary virome of COPD patients (relative abundance: 90–94%)54 and exhibiting comparable prevalence in lacrimal sac specimens from PANDO cases55. These consistent observations provide compelling evidence for its establishment within the human microbiome. Within this established context, the viral enrichment we observed specifically in healthy mother-neonate dyads delineates a previously unrecognized ecological configuration at the maternal-fetal interface. We hypothesize that while the BeAn 58058 virus may colonize multiple human ecological niches, its abundance dynamics and phenotypic expression appear to be tightly regulated by both local microenvironmental conditions and host systemic immune status. In localized pathological milieus—such as the COPD-affected lung or obstructed lacrimal sac—specific microenvironmental characteristics may facilitate its aberrant proliferation, whereas its relative enrichment in the systemic circulation might reflect a state of balanced coexistence under conditions of immune homeostasis. The precise mechanisms underlying these observations—potentially involving virus-host interactions and specific immunomodulatory pathways—warrant further investigation.

Substantial disparities in viral abundance were noted between maternal and umbilical cord blood, especially among Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, Parvoviridae, and Flaviviridae. Anelloviridae were far more abundant in maternal blood, consistent with limited vertical transmission and suggesting that mothers serve more as reservoirs than direct transmitters23,56. This underscores the importance of maternal immunity and the perinatal environment in early virome establishment57. Notably, the disease group in our study showed a modest reduction in the abundance of Anelloviridae. Although viral loads of this family typically increase in states of systemic immunosuppression, its replication dynamics may be influenced by the local immune milieu and viral competition58. The specific inflammatory or immune-activated state associated with maternal disease in our cohort may have partially compromised the persistence of Anelloviridae, thereby contributing to the observed decrease in abundance. Alternatively, the expansion of other viral families, such as Parvoviridae, under disease conditions could also contribute to the relative reduction in Anelloviridae abundance at the community level. Importantly, despite these fluctuations in viral abundance within the maternal circulation, the consistently observed disparity between MPB and UCB underscores that the placental barrier may effectively restrict the mother-to-infant transmission of Anelloviridae under both physiological and pathological conditions59. The minimal presence of Anelloviruses in umbilical cord blood aligns with longitudinal human and nonhuman primate studies, supporting that neonatal virome assembly occurs largely after birth via feeding, colonization, and environmental exposure60,61,62.Circovirus sequences displaying high homology (>99% identity) were detected in paired maternal–umbilical samples, offering compelling evidence supporting transplacental passage. Similar phenomena have been reported in animal models, with porcine circoviruses crossing the placenta and maintaining high sequence conservation63,64. Although human and porcine placentas exhibit anatomical differences65, the high sequence identity identified here suggests that human Circoviridae may cross the placental barrier, highlighting the need to explore viral tropism and immune evasion within the human placenta66,67. In addition to detecting highly homologous circovirus sequences suggestive of potential transplacental transmission, this study identified a sequence (Blood41-54603) exhibiting 96.22% amino acid identity with the Rep protein of a parrot-derived circovirus strain. This finding offers new perspectives for understanding viral transmission mechanisms: it may reflect cross-species transmission events or indicate functional conservation of the Rep protein during evolution. With continued advances in research on human-associated circoviruses and the ongoing discovery of novel sequences, it is anticipated that human circovirus variants showing even higher similarity to the sequences identified in this study may be discovered in the future. Collectively, these results suggest the possible existence of a previously underrecognized community of circoviruses within the human blood virome, whose diversity appears to extend beyond current understanding, warranting further investigation into their transmission routes and adaptation mechanisms. Parvoviridae demonstrated a more complex distribution pattern, with significantly higher abundance in the umbilical cord blood of diseased mothers. This observation supports the possibility that maternal disease status may alter placental permeability and facilitate fetal replication—a pattern consistent with the well-documented behavior of human parvovirus B19. On the other hand, their detection in maternal peripheral blood from healthy individuals may reflect only low-level persistent or latent infection or asymptomatic carriage, as widely documented for human parvovirus B19 in healthy populations. This presence does not necessarily indicate active infection, but rather may represent a baseline viral component that contributes to overall viral community diversity68,69. In contrast, although Flaviviridae (Pegivirus) sequences were detected in maternal peripheral blood, no complete genomes were assembled in umbilical cord blood, implying constrained transmission due to placental regulation or complex viral dynamics. Notably, all pegivirus sequences identified in our cohort were derived from healthy pregnant women without HIV co-infection or apparent immunosuppression. This finding provides a unique perspective for understanding the ecological behavior of HPgV-1 in immunocompetent hosts and lends support to the emerging view of its potential role as a commensal member of the blood virome. This observation does not contradict its established function as a biomarker in immunocompromised individuals, but rather collectively reveals the context-dependent nature of virus–host interactions: the ecological behavior of the same virus may vary considerably depending on the host’s immune status.

These findings suggest that maternal–fetal viral transmission varies substantially across viral families and appears to be influenced by a combination of environmental factors, placental selectivity, and maternal health status70,71,72,73 The marked enrichment of Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, and Flaviviridae in MPB implies that the placenta serves as an effective filter limiting transmission—a phenomenon consistent with clinical observations that many orthoflaviviruses (e.g. Zika virus) are transmitted vertically only at low rates, likely due to placental immune defense74. Phylogenetic analysis further substantiates this restricted transmission pattern. For Anelloviridae, the only UCB-derived sequence had no complete sequence assembled from its matched MPB sample and did not cluster with any MPB-derived sequences in the ORF1-based phylogeny. In parallel, no complete Flaviviridae genomes were recovered from any UCB samples. Together, these results underscore the efficiency of the placental barrier in limiting transmission of these viral families. Notably, an increased abundance of Parvoviridae was specifically observed in UCB from diseased mothers, raising important questions about the underlying transmission mechanism. Our phylogenetic analysis, however, revealed a more complex picture: although seven sequences were assembled (four from MPB and three from UCB), none exhibited direct mother-neonate pairing. One plausible interpretation is that maternal disease status may alter placental permeability, potentially facilitating the entry of environmental or reservoir-derived parvoviruses into the fetal circulation, rather than enabling direct vertical transmission of homologous maternal strains. This could suggest a distinct mode of viral exposure in utero, where the diseased maternal environment permits the passage of parvoviruses that are phylogenetically unrelated to those circulating in maternal blood. In contrast, Circoviridae provided more suggestive evidence for potential vertical transmission. Sequences from one matched MPB–UCB pair co-clustered in Rep-based phylogeny with high (99%) amino acid sequence identity, providing phylogenetic support for transplacental passage. These findings indicate that Parvoviridae and Circoviridae may occupy distinct ecological niches in vertical transmission, warranting further mechanistic investigation. Therefore, risk assessment of vertical viral transmission should account for taxonomic differences and avoid uniform interpretation across viral families.

However, this study has several limitations worthy of consideration. Although we employed strategies such as random primers and optimized PCR cycling conditions, PCR-based metagenomic approaches remain susceptible to amplification bias (including PCR jackpotting effects), which may affect the detection of low-abundance viruses21. To mitigate these potential biases, we implemented multiple safeguards in our experimental design: the use of random primers during reverse transcription and library preparation helped reduce sequence-specific bias, while our sample pooling strategy combining 4 to 7 individual samples served to average out amplification variations. Additionally, we employed a moderate 18 PCR cycles during library construction to balance material yield and amplification artifacts. Furthermore, our primary focus on comparative analyses between groups rather than absolute quantification enhances the robustness of our findings against systematic technical variations. While these measures strengthen the validity of our comparative results, we acknowledge that some degree of amplification bias may persist. Beyond methodological considerations, the study design itself presents inherent constraints. As a cross-sectional analysis, this work reveals associations between maternal health status and the maternal–neonatal virome but cannot establish causal relationships or fully delineate the dynamics of viral transmission3. On the other hand, the generally low viral load in blood samples, combined with the inherent limitations of short-read sequencing technology in genome assembly, may somewhat restrict the detection capability for low-abundance viruses and impede fine-resolution analysis of viral transmission routes27. Although phylogenetic analysis provides preliminary evidence supporting the possibility of vertical viral transmission, the precise transplacental pathways and underlying mechanisms still require further validation through approaches such as ex vivo placental models or longitudinal sampling throughout pregnancy75.

In summary, this large-scale metagenomic study reveals that both maternal peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood host complex viral communities, whose composition is influenced by the selective permeability of the placental barrier and maternal health status. Notably, we demonstrate that maternal disease alters viral profiles in both compartments and may enhance viral sharing and cord blood virome diversity3,76. Together, these findings establish a foundational framework for elucidating the ecological principles governing maternal–neonatal virome interactions and their impact on perinatal health. Our work thus provides a basis for potential strategies aimed at monitoring or modulating the maternal virome to improve infant outcomes, while also guiding future research into the evolutionary dynamics and functional mechanisms of viral assembly in early life.

Methods

Subjects and clinical data

To investigate the virome composition of maternal peripheral blood (MPB) and umbilical cord blood (UCB) and its potential association with maternal health status, we recruited parturients from the Affiliated Wujin Hospital of Jiangsu University. Initially, 434 maternal peripheral blood (MPB) samples and 426 paired umbilical cord blood (UCB) samples were collected. Following quality control assessment, one MPB sample was excluded due to quality issues. Ultimately, a total of 433 eligible MPB samples (including 7 without matched UCB specimens) and 426 eligible paired UCB samples were obtained for subsequent analysis. Based on two primary factors—sample type (Maternal Peripheral Blood, MPB, or Umbilical Cord Blood, UCB) and maternal health status (Healthy or Disease)—the samples were categorized into 175 subgroups. This classification defined four main cohorts: MPB-Healthy (37 subgroups), MPB-Disease (51 subgroups), UCB-Healthy (37 subgroups), and UCB-Disease (50 subgroups). Each subgroup corresponds to a single sequencing library and was constructed by pooling 4–7 individual samples that were identical in both sample type and maternal health status. Among these, subgroups 1–87 and 89–175 consisted of maternal peripheral blood and their paired umbilical cord blood samples, respectively, whereas subgroup 88 contained only maternal peripheral blood owing to the absence of a paired umbilical cord blood sample. Detailed metadata for each sequencing library are provided in Supplementary Data 1. All specimens were obtained through routine clinical procedures, anonymized prior to analysis, and exempted from individual informed consent. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Wujin Hospital of Jiangsu University (Approval Number: 2023-SR-103).

Sample collection, processing, and sequencing

Umbilical cord blood was collected immediately after delivery in accordance with international NetCord-FACT guidelines. Following neonatal cord clamping, trained obstetric staff performed aseptic collection using two clinical methods depending on the delivery process77: (i) In utero collection: before placental expulsion, a 10–15 cm segment near the placental end of the cord was disinfected. A sterile collection bag preloaded with CPDA-1 anticoagulant was then used to puncture the umbilical vein, and blood was allowed to drain by gravity. (ii) Ex utero collection: after placental delivery, the placenta was transferred to a sterile workbench, suspended with the fetal surface facing downward, and the umbilical vein was punctured for gravity drainage using the same method. Throughout both procedures, strict aseptic technique was maintained, and thorough mixing of blood with anticoagulant was ensured. The interval between cord clamping and sample collection was maintained within 5 min to prevent coagulation. Collected samples were labeled, stored in cold-chain boxes at 4°C, and delivered to the laboratory within 6 h for downstream processing78. Whole blood was centrifuged (10 min, 15,000 × g) to collect the supernatant, which was aliquoted into 1.5 mL sterile tubes. For each subgroup, an equal volume of ~100 µL of supernatant from each constituent individual sample was pooled to create a single sequencing library. This pooling strategy was essential to increase viral nucleic acid yield for robust metagenomic detection from low-biomass, low-viral-load blood samples. The pooled supernatant was then filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) to remove eukaryotic and bacterial cell-sized particles79. The filtrates enriched in viral particles were incubated at 37 °C with DNase (Ambion) and RNase (Fermentas) for 90 min to digest unprotected host and microbial nucleic acids80. Following enzymatic digestion, total nucleic acids were extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN), which recovers both viral RNA and DNA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. No DNase treatment was applied post-extraction. Reverse transcription was carried out with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and random hexamer primers to generate first-strand cDNA, followed by second-strand synthesis with the Klenow fragment polymerase (New England BioLabs), yielding double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates. Finally, 175 sequencing libraries were constructed using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) with 18 cycles of PCR amplification and subjected to 150 bp paired-end sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform81,82.

Bioinformatics analysis

Raw 150 bp paired-end reads were first processed using Illumina-provided software. The data were processed on an internal analysis pipeline running on a 32-node Linux cluster. Adapter sequences and low-quality bases were trimmed with Trim Galore v0.6.7 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) using the parameters: trim_galore -q 25 -j 40 --phred33 --clip_R1 10 --clip_R2 10 --length 35 --stringency 3 --paired. PCR duplicates were removed based on the internal analysis pipeline. Specifically, reads with identical bases from positions 5 to 55 were identified as duplicates, with only one copy randomly retained and clonal reads discarded. Subsequently, Host-derived nucleic acids were removed by aligning reads against the human reference genome (Homo sapiens, GCF_000001405.40) using Bowtie2 v2.4.583,84. All host-mapped reads were discarded. De novo assembly of host-filtered reads was conducted independently for each library with MEGAHIT v1.2.985,86 using default parameters. To minimize false negatives, unmapped reads and contigs shorter than 500 bp were further assembled with the de novo assembler in Geneious Prime (https://www.geneious.com). After reassembly, only contigs ≥1500 bp were retained, and sequences containing frameshift mutations were manually inspected and removed87. Following sample pooling at the subgroup level for library construction, all bioinformatic processes, including de novo assembly, were performed on a per-library basis. The high-quality contigs (≥1500 bp) obtained thus preserved their library-specific identity, ensuring traceability throughout the downstream analyses.

Viral genome identification and annotation

Viral sequences derived from MPB and UCB libraries were characterized through a multi-step pipeline. First, all assembled contigs were queried against the viral subset of the non-redundant (nr) protein database (downloaded on March 30, 2025) using BLASTx in DIAMOND v2.1.1288,89 with an E-value threshold of <10⁻⁵. To increase annotation accuracy and exclude false positives, candidate sequences were subsequently compared against the complete nr database. The resulting contigs were then imported into Geneious Prime® 2024.0.5 for refinement and inspection90. Potential vector-derived contaminants were removed using VecScreen (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/vecscreen), an NCBI BLASTn-based tool. Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted in Geneious Prime with parameters set to a minimum length of 100 bp and ATG as the start codon. Conserved protein domains were annotated using the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) v3.21 (E-value < 10⁻⁵)91, which integrates curated NCBI models and entries from Pfam, SMART, COG, PRK, and TIGRFAM92. Contigs containing viral marker genes representative of major taxonomic groups were retained for downstream phylogenetic inference.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic relationships among viral groups were inferred using predicted viral amino acid or nucleotide sequences, the closest homologs identified by BLASTx/ BLASTn searches against GenBank, and representative reference sequences retrieved from the GenBank non-redundant protein database using targeted queries: “ORF1 AND Anelloviridae” for Anelloviridae, “Rep AND Circoviridae” for Circoviridae, “NS1 AND Parvoviridae” for Parvoviridae, and “RdRp AND Flaviviridae” for Flaviviridae. During the selection process, we prioritized complete and representative sequences that encompassed the diversity of major subfamilies or genera within each viral family. A total of 86, 41, 29, and 27 reference sequences were included for each family, respectively, with detailed accession numbers provided in Supplementary Data 2. Multiple sequence alignments were performed in MEGA v11.0.1393 using MUSCLE with default settings. Sites with >50% missing data were excluded. Bayesian inference (BI) phylogenetic trees were generated in MrBayes v3.2.794, with the substitution model set as prset aamodelpremixed. Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs were conducted until the average standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01. The first 25% of sampled trees were discarded as burn-in. Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were reconstructed in MEGA v11.0.1393 to validate BI topologies. Final tree visualization was performed using iTOL95 and graphically edited in Adobe Illustrator 2025 (https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator/free-trial-download.html)96.

Statistical analysis

Viral composition across 175 libraries was analyzed with MEGAN v6.22.297, which applies the lowest common ancestor (LCA) algorithm to assign reads to taxonomic groups and generate hierarchical summaries98. Furthermore, the “compare” function in MEGAN was utilized to systematically compare viral community structures across different libraries. To evaluate the coverage of viral diversity by sequencing depth, rarefaction curves were generated using the built-in rarefaction analysis tool in MEGAN. The hierarchical summaries and comparative community data obtained from these analyses were subsequently exported and served as the foundation for further statistical analysis. Statistical analyses and visualizations were performed in R v4.4.2 and ChiPlot (https://www.chiplot.online/). Viral α-diversity (Shannon and Simpson indices) was calculated using the R packages vegan v2.6.6 and picante v1.8.2. Intergroup differences were tested with the Mann–Whitney U test. β-diversity was estimated using Bray–Curtis distance matrices and visualized with principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). Intergroup variation in community structure was assessed with PERMANOVA (Adonis) based on permutation tests. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Differential abundance analysis at the family and species levels was performed using STAMP v2.1.319. Specifically, two-sided Welch’s t-test was used to compare viral abundance between healthy and diseased groups, with confidence intervals calculated by the DP: Welch’s inverted method. The Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied, and an FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Community composition and abundance were visualized with heatmaps, stacked bar charts, pie charts, and UpSet plots generated in R and ChiPlot. Family-level abundance differences were further assessed using GraphPad Prism v9.5, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Quality control

All procedures were performed in a BSL-2 cabinet with aerosol-resistant filter tips to avoid nucleic acid contamination. All tubes and consumables were certified nuclease-free. DEPC-treated water (Sangon Biotech) was used throughout nucleic acid handling.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study are available at the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn) under BioProject accession number PRJCA045326. Details are provided in Supplementary Data 1. All sequences have also been deposited in NGDC without restrictions, with accession numbers listed in Supplementary Data 2.

References

Parker, E. L., Silverstein, R. B., Verma, S. & Mysorekar, I. U. Viral-immune cell interactions at the maternal-fetal interface in human pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 11, 522047 (2020).

Kandathil, A. J. & Thomas, D. L. The blood virome: a new frontier in biomedical science. Biomed. Pharmacother. 175, 116608 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Maternal and neonatal viromes indicate the risk of offspring’s gastrointestinal tract exposure to pathogenic viruses of vaginal origin during delivery. mLife 1, 303–310 (2022).

Yordanova, A. et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell secretome: A potential regulator of B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 12515 (2024).

Noroozi-aghideh, A. & Kheirandish, M. Human cord blood-derived viral pathogens as the potential threats to the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation safety: a mini review. World J. Stem Cells 11, 73–83 (2019).

Stout, M. J., Brar, A. K., Herter, B. N., Rankin, A. & Wylie, K.M. The plasma virome in longitudinal samples from pregnant patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1061230 (2023).

Sequoia, J. A. et al. Identification of bacteriophage DNA in human umbilical cord blood. JCI Insight 10, e183123 (2025).

Garmaeva, S. et al. Transmission and dynamics of mother-infant gut viruses during pregnancy and early life. Nat. Commun. 15, 1945 (2024).

Lu, X. et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals the diversity of the vaginal virome and its association with vaginitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15, 1582553 (2025).

Bai, G.-H., Lin, S.-C., Hsu, Y.-H. & Chen, S.-Y. The human virome: viral metagenomics, relations with human diseases, and therapeutic applications. Viruses 14, 278 (2022).

Stupak, A. et al. A virome and proteomic analysis of placental microbiota in pregnancies with and without fetal growth restriction. Cells 13, 1753 (2024).

Elgueta, D., Murgas, P., Riquelme, E., Yang, G. & Cancino, G. I. Consequences of viral infection and cytokine production during pregnancy on brain development in offspring. Front. Immunol. 13, 816619 (2022).

Rathore, A. P. S., Costa, V. V. & St. John, A. L. Editorial: Viral infection at the maternal-fetal interface. Front. Immunol. 13, 828681 (2022).

Gigase, F. A. J. et al. Maternal immune activation during pregnancy and obstetric outcomes: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 132, 1307–1318 (2025).

D’Argenio, V. The prenatal microbiome: A new player for human health. High. Throughput 7, 38 (2018).

Schloss, P. D. & Handelsman, J. Biotechnological prospects from metagenomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14, 303–310 (2003).

Torres Montaguth, O. E., Buddle, S., Morfopoulou, S. & Breuer, J. Clinical metagenomics for diagnosis and surveillance of viral pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-025-01223-5 (2025).

Elste, J. et al. Significance of artificial intelligence in the study of virus–host cell interactions. Biomolecules 14, 911 (2024).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30, 3123–3124 (2014).

Puccetti, C. et al. Parvovirus B19 in pregnancy: possible consequences of vertical transmission. Prenat. Diagn. 32, 897–902 (2012).

Varsani, A. et al. Anelloviridae taxonomy update 2023. Arch. Virol. 168, 277 (2023).

Freer, G. et al. The virome and its major component, anellovirus, a convoluted system molding human immune defenses and possibly affecting the development of asthma and respiratory diseases in childhood. Front. Microbiol. 9, 686 (2018).

Cebriá-Mendoza, M. et al. Human anelloviruses: Influence of demographic factors, recombination, and worldwide diversity. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0492822 (2023).

Kyathanahalli, C., Snedden, M. & Hirsch, E. Human anelloviruses: prevalence and clinical significance during pregnancy. Front. Virol. 1, 782886 (2021).

Sabbaghian, M., Gheitasi, H., Shekarchi, A. A., Tavakoli, A. & Poortahmasebi, V. The mysterious anelloviruses: investigating its role in human diseases. BMC Microbiol 24, 40 (2024).

Timmerman, A. L. et al. Anellovirus constraint from 2 to 6 months postpartum followed by betatorquevirus and gammatorquevirus dominance in serum and milk. J. Virol. 99, e0084625 (2025).

Varsani, A. et al. 2024 taxonomy update for the family Circoviridae. Arch. Virol. 169, 176 (2024).

Delwart, E. & Li, L. Rapidly expanding genetic diversity and host range of the Circoviridae viral family and other rep encoding small circular ssDNA genomes. Virus Res. 164, 114–121 (2012).

Dai, Z. et al. Identification of a novel circovirus in blood sample of giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Infect. Genet. Evol. 95, 105077 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Novel circovirus in blood from intravenous Drug Users, Yunnan, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 1015–1019 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Novel cycloviruses identified by mining human blood metagenomic data show close relationship to those from animals. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1522416 (2025).

Cotmore, S. F. et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: parvoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 367–368 (2019).

Canuti, M. et al. Investigating the diversity and host range of novel parvoviruses from North American ducks using epidemiology, phylogenetics, genome structure, and codon usage analysis. Viruses 13, 193 (2021).

Pénzes, J. J. et al. Reorganizing the family Parvoviridae: a revised taxonomy independent of the canonical approach based on host association. Arch. Virol. 165, 2133–2146 (2020).

Dittmer, F. P. et al. Parvovirus B19 Infection and pregnancy: review of the current knowledge. J. Pers. Med. 14, 139 (2024).

Kagan, K. O., Hoopmann, M., Geipel, A., Sonek, J. & Enders, M. Prenatal parvovirus B19 infection. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 310, 2363–2371 (2024).

Simmonds, P. et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 98, 2–3 (2017).

Goh, J. Z. H., De Hayr, L., Khromykh, A. A. & Slonchak, A. The flavivirus non-structural protein 5 (NS5): structure, functions, and targeting for development of vaccines and therapeutics. Vaccines 12, 865 (2024).

Donaldson, M. K., Zanders, L. A. & Jose, J. Functional roles and host interactions of orthoflavivirus non-structural proteins during replication. Pathogens 14, 184 (2025).

Smith, D. B. et al. Proposed update to the taxonomy of the genera Hepacivirus and Pegivirus within the Flaviviridae family. J. Gen. Virol. 97, 2894–2907 (2016).

Ba, F. et al. Zika virus-related birth defects and neurological complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 35, e70019 (2025).

Santos, L. M. et al. Prevalence and vertical transmission of human pegivirus among pregnant women infected with HIV. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 138, 113–118 (2017).

Garand, M. et al. A case of persistent human pegivirus infection in two separate pregnancies of a woman. Microorganisms 10, 1925 (2022).

Kowarsky, M. et al. Numerous uncharacterized and highly divergent microbes which colonize humans are revealed by circulating cell-free DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 9623–9628 (2017).

Liang, G. & Bushman, F. D. The human virome: assembly, composition and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 514–527 (2021).

Tetz, G. V. et al. Bacteriophages as potential new mammalian pathogens. Sci. Rep. 7, 7043 (2017).

Vives, M. J. Decoding the human phageome helps to unravel microbial dynamics in health and disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 91, e00919–e00925 (2025).

Göke, J. et al. Dynamic transcription of distinct classes of endogenous retroviral elements marks specific populations of early human embryonic cells. Cell Stem Cell 16, 135–141 (2015).

Dou, A., Xu, J. & Zhou, C. The relationship between HERVs and exogenous viral infections: a focus on the value of HERVs in disease prediction and treatment. Virulence 16, 2523888 (2025).

Toudic, C. et al. Galectin-1 modulates the fusogenic activity of placental endogenous retroviral envelopes. Viruses 15, 2441 (2023).

Mi, S. et al. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature 403, 785–789 (2000).

Bergallo, M. et al. Human endogenous retroviruses are preferentially expressed in mononuclear cells from cord blood than from maternal blood and in the fetal part of placenta. Front. Pediatr. 8, 244 (2020).

Megli, C. J. & Coyne, C. B. Infections at the maternal-fetal interface: an overview of pathogenesis and defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 67–82 (2022).

Goolam Mahomed, T. et al. Lung microbiome of stable and exacerbated COPD patients in tshwane, south africa. Sci. Rep. 11, 19758 (2021).

Ali, M. J. Fungal microbiome (mycobiome) and virome of the lacrimal sac in patients with PANDO: the lacriome paper 5. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 108, 317–322 (2024).

De Vlaminck, I. et al. Temporal response of the human virome to immunosuppression and antiviral therapy. Cell 155, 1178–1187 (2013).

Sloan, P. et al. Alphatorquevirus is the most prevalent virus identified in blood from a matched maternal-infant preterm cohort. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 35, 1636–1642 (2022).

Kyathanahalli, C. et al. Maternal plasma and salivary anelloviruses in pregnancy and preterm birth. Front. Med. 10, 1191938 (2023).

Kaczorowska, J. & van der Hoek, L. Human anelloviruses: diverse, omnipresent and commensal members of the virome. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 305–313 (2020).

Liang, G. et al. The stepwise assembly of the neonatal virome is modulated by breastfeeding. Nature 581, 470–474 (2020).

Kaczorowska, J. et al. Early-life colonization by anelloviruses in infants. Viruses 14, 865 (2022).

Lim, E. S. et al. Early life dynamics of the human gut virome and bacterial microbiome in infants. Nat. Med. 21, 1228–1234 (2015).

Vargas-Bermudez, D. S., Polo, G., Mogollon, J. D. & Jaime, J. Longitudinal monitoring of mono- and coinfections involving primary porcine reproductive viruses (PCV2, PPV1, and PRRSV) as well as emerging viruses (PCV3, PCV4, and nPPVs) in primiparous and multiparous sows and their litters. Pathogens 14, 573 (2025).

Dvorak, C. M. T., Lilla, M. P., Baker, S. R. & Murtaugh, M. P. Multiple routes of porcine circovirus type 2 transmission to piglets in the presence of maternal immunity. Vet. Microbiol. 166, 365–374 (2013).

Furukawa, S., Kuroda, Y. & Sugiyama, A. A comparison of the histological structure of the placenta in experimental animals. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 27, 11–18 (2014).

da Silva, M. K. et al. A newly discovered circovirus and its potential impact on human health and disease. Int. J. Surg. 110, 2523–2525 (2024).

Schust, D. J. et al. The immunology of syncytialized trophoblast. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1767 (2021).