Abstract

Here, we demonstrate that the lattice oxygen release on the high-capacity cathode, Li1.2Ni0.6Mn0.2O2 (LNMO) surface can be successfully suppressed through S-anion-substitution using density functional theory (DFT) calculations and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations. The oxygen evolution mechanisms on pristine and sulfur (S)-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces in the presence of an electrolyte mixture are compared. Over-oxidation of O2− anions during delithiation in the pristine surface results in oxygen evolution and subsequent structural deformation. Whereas, in the S-substituted LNMO, S2− anions primarily participate in charge compensation and further inhibit oxygen evolution and O vacancy formation at high degrees of delithiation. Furthermore, the S-substitution effectively prevents the formation of Ni3+ ions and Jahn-Teller distortion, retaining the layered structure during delithiation. Our findings provide insight into improving the structural stability of the LNMO (003) surface, paving the way for developing Li-rich LNMO cathode materials for next-generation LIBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past few decades, high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have been extensively investigated and widely used as a major power source owing to the emerging market for electronic devices and electric vehicles1,2,3,4,5. However, increasing the energy density of commercial LIBs will be necessary to meet the growing demand for large-scale energy storage devices. Therefore, the design and development of innovative cathode materials with high specific capacities and redox potential becomes of utmost importance6,7. Recently, Li-rich layered transition-metal (TM) oxides, including Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.8O2 (LNMO), have attracted considerable attention due to their large theoretical specific capacity (up to 300 mA h g−1)2,8,9,10. Furthermore, oxygen vacancies in LNMO cathode materials are considered beneficial defects since they can regulate the electrochemical properties and electrical conductivity of cathode materials11,12,13,14. Tang et al. have shown that the formation of oxygen vacancies in LNMO cathode materials can have a significant impact on LIBs performance, such as charge transfer resistance, specific capacity, and the rate of charging and discharging11. However, an excess of oxygen vacancies in LNMO materials resulted in the structural transformation layered to spinel-like or rock-salt phases, which leads to low efficiency and fast-fading capacity as well as fading voltage in LIBs1,5,15,16,17,18,19,20. In addition, lattice-oxygen evolution is strongly associated with oxygen vacancy formation in these LNMO materials during delithiation11,21. The over-oxidation of some O2− anions during delithiation is widely assumed to be the primary cause of the formation of oxygen vacancies and lattice-oxygen evolution in cathode materials22,23,24.

Understanding the triggering factors for the oxygen evolution mechanism and circumventing capacity fading and structural degradation limitations in LNMO cathode materials are therefore essential for developing better cathode materials in LIBs. Tarascon et al. have shown that under-coordinated surface oxygen prefers over-oxidation during charging, resulting in the formation of O2 molecules and peroxide-like (O2)n− species25. They also demonstrated that a particular environment of metal–oxygen hybridization in LNMO cathode materials has a significant impact on oxygen evolution. Ceder et al. identified that the O2− p-orbital along with the Li–O–Li direction generated a specific non-bonding band with a higher energy level, increasing the O redox activity and facilitating oxygen evolution of LNMO cathode materials26. To overcome this limitation, element doping or inert-layer coating are commonly used to suppress oxygen evolution or alleviate structural deformation during cycling. Zhang et al. reported that the inherent stability of the structure can be ameliorated, and lattice-oxygen release can be suppressed by fabricating a spinel Li4Mn5O12 coating on a Li-rich layered cathode material27. In addition, surface doping is a promising modification method that can improve the structural stability of LNMO cathode materials and suppress irreversible oxygen evolution on the surface28,29,30. Various heteroatom dopants can affect the structural stability and electronic properties of cathode materials in different ways. For instance, our previous study demonstrated that doping the Ni site of the Li-rich LNMO material with Cd ions can effectively inhibit the structural change and suppress the Jahn-Teller distortion during the delithiation process31. Similarly, Nayak et al. demonstrated that the addition of Al3+ in the LNMO cathode material has a surface stabilization effect, improving structural stability by alleviating oxygen evolution32. In addition to cationic substitutions, Jiang et al. have shown that sulfur-doped LiMn2O4 exhibits improved cycling stability and a higher capacity during cycling33. Additionally, sulfur doping into MnO2 nanosheets is also being investigated as a high-performance cathode for Zn-ion batteries due to the addition of Zn storage sites that exhibit pseudocapacitive properties34. Along with the effects of sulfur doping on these cathode materials, Zhang et al. also demonstrated that S-substitution in the O site of LNMO could stabilize and improve the cycling stability and rate performance (a capacity of 117 mA h g−1 is maintained)35.

However, a fundamental understanding of the formation of O vacancy, lattice-oxygen-evolution mechanism, and structural deformation during delithiation in S-substituted LNMO cathode materials have not been thoroughly examined, particularly the role of S-substitution at the O site. We recently reported the oxygen oxidation mechanisms in the LNMO (003) surface by considering different local oxygen-coordination environments and investigating their oxidation process during various degrees of delithiation36. We observed that the oxygen–dimer formation could be attributed to the over-oxidation of the O2− anions by forming an irreversible superoxide O2− at a high degree of delithiation. However, the lattice-oxygen evolution and structural stability of the LNMO (003) surface in the presence of an electrolyte mixture were not considered in our previous study. Thus, in this work, we used DFT and AIMD simulations to investigate the oxygen evolution mechanism and the oxidation state of TM ions and O2− anions in both pristine and S-substituted LNMO surfaces with electrolytes, with a focus on the role of sulfur substitution in lattice-oxygen formation and structural degradation.

Results and discussion

Oxygen evolution mechanism and electronic characteristics during delithiation

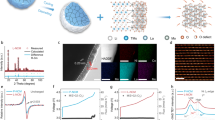

To further investigate the oxygen evolution mechanism in LNMO (003) surfaces during delithiation, we have compared each delithiated structure and the oxidation state of O2− anions and TM metals using AIMD simulations. During the delithiation process, we considered different delithiation states from x = 0 to 0.8 in the pristine Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) surfaces. A step-by-step delithiation process was performed on the Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) surface by removing four lithium atoms at a time. The simulated pristine model before delithiation is illustrated in Fig. 1a, and the optimized geometries of electrolyte components are shown in Fig. 1b. After the removal of Li ions from the LNMO (003) surface, the system was equilibrated for 5 ps, during which it demonstrated a structural change and reached a new equilibrium. In addition, the energy was determined by calculating the lowest total energy over the final half of the trajectory. The intercalation potential (V) vs. Li/Li+ can be determined as Eq. (1)31

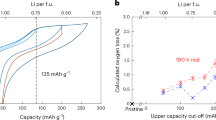

where \({\rm{E}}\left( {{\rm{Li}}_{{{{\mathrm{1}}}}{{{\mathrm{.2}}}}}{{{\mathrm{Ni}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{0}}}}{{{\mathrm{.2}}}}}{{{\mathrm{Mn}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{0}}}}{{{\mathrm{.6}}}}}{\rm{O}}_2} \right)\) and \({\rm{E}}\left( {{\rm{Li}}_{{{{\mathrm{1}}}}{{{\mathrm{.2 - x}}}}}{{{\mathrm{Ni}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{0}}}}{{{\mathrm{.2}}}}}{{{\mathrm{Mn}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{0}}}}{{{\mathrm{.6}}}}}{\rm{O}}_2} \right)\) are the calculated total energies of the system before and after Li-ion intercalation, respectively, and E(Libulk) is the total energy of the bulk Li metal. The calculated intercalation potential of Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) as a function of the delithiation state is shown in Fig. 1c. In addition, we demonstrate the configurations of the cathode/electrolyte interface from low to high delithiation levels of x = 0.13, 0.26, 0.4, 0.53, 0.67, and 0.80, as shown in Fig. 2. From Fig. 1c, the LNMO cathode material demonstrates a high voltage of ~4 V at a delithiation level of x = 0.07. The observations from the voltage profile indicate that the voltage gradually increases with an increase in the degree of delithiation. Furthermore, we analyzed the configurations of the LNMO (003) surface during delithiation, and the configurations are shown in Fig. 2. The decomposition of the LiPF6 and solvent molecules (EC and DEC) were not observed, indicating their great stability on the LNMO (003) surface during delithiation. The LNMO (003) surface demonstrates high structural stability at the delithiation level of x = 0.26; in contrast, oxygen molecule formation at the interface between the LNMO (003) surface and electrolytes is observed at the delithiation level of x = 0.4. When the delithiation level reaches x = 0.67, we found the second oxygen molecule formation at the second layer of the Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) surface, indicating that some of the O atoms are under-coordinated (fewer than three cations) at high degrees of delithiation. Such under-coordinated O atoms may undergo oxygen evolution and further degrade the LNMO (003) surface, resulting in an irreversible reaction and fading capacity.

a Pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces, and b electrolyte including Li salt (LiPF6) and solvent mixture (EC/DEC). c Voltage profile for the pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces calculated at different delithiation levels. During the delithiation process, Li ions were removed from the first- and second-layer LNMO (003) surface. After the removal of Li ions from both layers, the system was equilibrated for 5 ps.

The participation of lattice oxygen in delithiation is related to the oxidation activity of the O2− anion. Bader charge analysis was employed to characterize and visualize the change in atomic charge on the LNMO (003) surface during delithiation. The calculated Bader charges of the O anions at different delithiation levels are shown in Fig. 3a. At an initial state of x = 0, the average charge for O anions is approximately −1.3|e|. When the delithiation level is increased, the average atomic charge of the O anions becomes less negative, indicating that the lattice oxygen anions significantly participated in the charge compensation process during delithiation. When LNMO (003) was changed from the initial state to x = 0.33, no over-oxidation of the O anions was detected. However, a sudden increase in the atomic charge (orange line in Fig. 3a) was observed from −1.0 to −0.2|e| at the delithiation level of x = 0.4, indicating a significant change in the oxidation state from O2− to O2n−. The calculated Bader charge shows the formation of oxygen via a sudden increase in the atomic charge (larger than −0.4|e|), which can serve as a baseline for oxygen evolution. Furthermore, we observed the second oxygen formation at the delithiation level x = 0.67, and the value of the atomic charge also exceeds the baseline of oxygen evolution from −0.9 to −0.3|e| (green line in Fig. 3a).

a Calculated Bader charge (|e|) of individual O atoms in the pristine LNMO (003) surface. The transparent line indicates the Bader charge of On− anion, and all the value of Bader charge is blow than the black dashed line (a critical point of −0.4). The orange and green line in a represents the Bader charge of O atoms in the O2 molecule. The red dashed line indicates the average charge of O atoms in the system. b The change of atomic charge (ΔQ in |e|/atom) of O, Ni, and Mn atoms in the pristine LNMO (003) surface at different levels of delithiation. c Calculated Bader charge (|e|) of individual O atoms in the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface. d An investigation into the ΔQ (|e|/atom) of O and S atoms in the pristine and S-substituted surfaces.

To further understand the detailed mechanism of oxygen evolution in the LNMO (003) surface, we calculated the change in atomic charge (ΔQ) for the O anions and TM ions (Ni and Mn) in the LNMO (003) surface at various delithiation levels, and the results are plotted in Fig. 3b. A positive value of ΔQ indicates that the atom loses electrons and increases its oxidation state. The ΔQ value of Mn atoms shows a slight increase and then remains almost constant during the entire delithiation process, indicating that Mn atoms are not involved in the charge compensation process. The ΔQ values of Ni atoms undergo a relatively significant increase during the delithiation process compared to those of Mn atoms, and it demonstrates that the Ni atoms are primarily involved in the oxidation process, which is consistent with our previous and other studies22,23,31. The value of ΔQ for O anions significantly increases, implying that the oxidation activity of O anions in LNMO (003) surface is more than those of Ni2+ and Mn4+ ions. The charge compensation process in the LNMO (003) surface during the whole delithiation process is dominated by the O2−/O2n− couple, as observed in Fig. 3a, b.

Effects of S-substitution on oxygen evolution

Oxygen release in Li-rich LNMO cathode materials usually causes undesired structural degradation, resulting in the rapid fading of capacity/voltage in LIBs. Therefore, proposing a strategic method for suppressing oxygen release was a challenge in this study. Considering the similar electronic configurations of S and O, we employed S−2 substitution in the LNMO (003) surface by replacing the O−2 anions. The simulated S-substituted LNMO before delithiation is illustrated in Fig. 1a. As a further investigation into the effects of S-substitution on oxygen evolution during delithiation, we calculated the intercalation potential of the S-substituted LNMO cathode material as a function of the delithiation state, as shown in Fig. 1c. The calculated voltage value for the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface is ~3.5 V at the initial delithiation level, which is lower than the value for the pristine system (4.0 V). We also illustrated the optimized configurations of electrolytes on the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface from low to high degrees of delithiation in Fig. 4, which demonstrates that sulfite-like species (SO2)n− are generated on the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface at delithiation levels of x = 0.4 and 0.8. At delithiation level x = 0.53, the formation of (SO3)m− species on the S-substituted LNMO surface is observed, but there is no oxygen evolution on the S-substituted surface. The formation of (SO2)n−/(SO3)m− indicates a shift in the redox center from the more electronegative O atoms to the less electronegative S atoms after the sulfur substitution, which plays an important role in charge compensation during delithiation. Although S-substitution lowers the electrode potential, our structural analysis of the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface at different delithiation levels shows that the substitution of S anion could effectively suppress oxygen evolution.

To compare the oxidation state of O atoms in the pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces, we calculated the Bader charge corresponding to the O atoms in the S-substituted system at various delithiation levels and are illustrated in Fig. 3c. The average atomic charge of the O atoms in the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface gradually increased during delithiation, as we noticed in the pristine LNMO surface (Fig. 3a). However, all the O atomic charge in the S-substituted system is below the baseline of −0.4|e|, suggesting that there is no over-oxidation of lattice oxygen anions at the S-substituted LNMO surface. This result indicates that S-substitution effectively suppresses the redox activity of O atoms and inhibits the over-oxidation of O atoms; therefore, no O2 molecule formation occurred even at a higher degree of delithiation. Furthermore, we analyzed the change in the atomic charge (ΔQ) of anions and TMs on the S-substituted LNMO surface to confirm the suppression of oxygen redox activity. The ΔQ values for the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface are summarized in Table 1, where positive values represent electron loss. Notably, S anions exhibit significant electron loss upon delithiation, confirming that the redox center is transferred from O atoms to S atoms. On the other hand, the ΔQ value for the O anions in the S-substituted system is changed to 0.064|e|/atom during delithiation, which is lower than 0.46|e|/atom in the pristine system (Fig. 3d). The large ΔQ for S anions is due to the formation of sulfite-like (SO2)n−/(SO3)m− species on the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface, as shown in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the huge oxidation of S anions can be considered as an electron buffer; consequently, S anions can participate in charge compensation to effectively prevent lattice-oxygen evolution. This result supports that the presence of S anions can significantly inhibit oxygen oxidation in LNMO cathode materials.

We further investigated the redox activity of TM atoms in the S-substituted LNMO surface by calculating the change in atomic charge (ΔQ) and electronic properties during the delithiation process, and the results are given in Table 1. The ΔQ values of Ni atoms are changed significantly after delithiation compared to those of Mn atoms, indicating that the Ni atoms in the S-substituted LNMO surface are primarily involved in the oxidation process, as like pristine surface. To further explore the changes in the electronic properties of Ni upon extraction of Li atoms in the pristine and S-substituted LNMO surfaces, we projected the density of states (PDOS) of the 3d-orbital of Ni and Mn atoms in the first and second TM layers at delithiation levels of x = 0 and 0.4, as shown in Fig. 5. In the pristine system, the Ni d states are shifted from below the Fermi level to above the Fermi level at the delithiation level x = 0.4 compared to the initial state (x = 0), indicating that Ni atoms lose electrons from the Ni d-orbital (Fig. 5a, b). Moreover, we integrated the areas under the PDOS peaks above the Fermi level at the delithiation levels of x = 0 and x = 0.4, which are 16.1 and 17.0, respectively. The increased oxidation of the Ni atoms at x = 0.4 is supported by the increase in the area above the Fermi level during delithiation.

The PDOS of the S-substituted LNMO surface (Fig. 5c) shows that the Ni valance band is significantly up-shifted and close to the Fermi level at x = 0 compared to the pristine system (Fig. 5a), suggesting that Ni oxidation is more favorable in the S-substituted system than in the pristine system. As shown in Fig. 5d, the 3d states of Ni atoms in the S-substituted system are shifted more from the valence band to the conduction band after delithiation (x = 0.4) than in the pristine system (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the integral areas above the Fermi level for the 3d states of Ni atoms in the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface at delithiation levels of x = 0 and x = 0.4 are 16.2 and 17.4, respectively, demonstrating that S-substitution can improve Ni atoms’ ability to lose electrons compared to the pristine system. In general, increasing the oxidation of Ni atoms can improve capacity retention significantly2,29. Apart from the capacity retention, the oxidation change of Ni atoms during delithiation would also influence the stability of LNMO (003) surfaces. It is reported that the Ni3+ atoms in the LNMO materials would induce the Jahn-Teller distortion and cause structural instability31,37,38,39. Hence, we have examined the oxidation states of Ni ions using the magnetic moment at two delithiation levels, x = 0.4 and 0.8, respectively, which are given in Table 2. The calculated magnetic moment of Ni on the pristine LNMO (003) surface at the delithiated state of x = 0.4 indicates that Ni atoms are +3 oxidation state (~1.3 μB), while the Ni atoms on the S-substituted surface exhibit a +4 oxidation state (~0.3 μB). For x =0.8, some Ni atoms change their oxidation state from Ni3+ to Ni4+, causing a decrease in average magnetic moment. Nevertheless, we found that the average magnetic moment of Ni atoms on the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface remains ~0.3 μB (+4 oxidation state), preventing the formation of Ni3+ ions, as well as avoiding the Jahn-Teller distortion and structural deformation during delithiation. Our results show that the substitution of the S atom significantly reduces O atom oxidation due to charge compensation from the electron buffer of the S atom and inhibits the formation of Ni3+ ions and the Jahn-Teller distortion.

Oxygen vacancy formation during delithiation

The formation of lattice oxygen in Li-rich LNMO cathode materials during delithiation usually generates undesired O vacancies, and the excess of O vacancies would cause structural degradation of LNMO cathode, resulting in the rapid fading of capacity/voltage in LIBs. To study the effect of S-substitution on the O vacancy formation on the LNMO surface, a step-by-step delithiation process was performed on the pristine and S-substituted Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) surfaces. Then, we considered all possibilities of O vacancy sites at the first and second O-layer in the pristine and S-substituted LNMO surface, and we chose the most favorable O vacancy site for the following calculations. Figure 6a shows the optimized structures of the pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces at the delithiated state of x = 0 and 0.4. The black dashed circle represents the position of O vacancy in the unit cell. Then, we evaluated the formation of O vacancy in the unit cell as the delithiated state of the Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 refers to Li0.4Ni0.2Mn0.6O2, and the formation energy of O vacancy versus the delithiated state is depicted in Fig. 6b. As shown in Fig. 6b, we can find that the formation energy of O vacancy is sharply reduced once removing Li atoms from the pristine LNMO (003) surface, indicating that the O vacancy formation becomes more thermodynamically favorable. When the delithiated state reaches x = 0.4, the formation energy of O vacancy becomes negative, implying that the formation of O vacancy could occur spontaneously on the pristine surface. Nevertheless, the substitution of S anions inhibits the O vacancy formation on the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface. The formation energy changes slowly from positive to negative when the delithiated state reaches x = 0.67, demonstrating that S-substitution can effectively suppress the O vacancy formation. According to the oxidation state of O atoms and O vacancy formation, it can be found that S-substitution into Li-rich LNMO cathode materials could further inhibit lattice oxygen evolution on the surface.

Effects of S-substitution on phase transition

The irreversible phase transition from the layered structure to a new phase caused by oxygen vacancies and TM migration during cycling affects the structural stability of LNMO cathodes, resulting in voltage decay and capacity fading15. To understand this, we explored the detailed configurations of each TM ion during the delithiation of both pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces. The number of octahedral and tetrahedral sites for Mn and Ni atoms in the first layer of the pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces are listed in Table 3. Figure 7 illustrates the structural deformation before and after delithiation in the pristine and S-substituted Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) surfaces. We observed that structural deformation occurred at the delithiation level of x = 0.4 in the pristine LNMO surface, owing to the increased amounts of Mn and Ni atoms from the octahedral to tetrahedral configuration. For the pristine system, the MnO6 and NiO6 octahedra are changed to MnO4 and NiO4 tetrahedra, with surface oxygen formation from the Mn–O environment at the delithiation level of x = 0.4. Furthermore, structural deformation in the S-substituted surface can be observed when the delithiation state reaches x = 0.67, and the extent of this structural change is less than that of the pristine surface at a higher degree of delithiation, as shown in Table 2. This result suggests that the structural change of S-substituted LNMO (003) is insignificant at low degrees of delithiation state. In addition, the S-substituted LNMO (003) maintains a layered structure at the delithiation level of x = 0.4 (Fig. 7), suggesting that S-substitution can effectively prevent structural deformation during the charging process. Thus, we can conclude that S-substitution in the Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 cathode material plays a significant role in the electron buffer to participate in charge compensation, which further circumvents lattice-oxygen formation and release and effectively reduces structural deformation during the delithiation process.

Side views of the optimized geometries for the pristine and S-substituted LNMO surfaces at the delithiation levels of x = 0 and x = 0.4. The black circle indicates the lattice oxygen evolution and the displacement of Ni and Mn atoms on the LNMO surface. [Color code: red- oxygen; gray- manganese; green- nickel; purple-lithium.].

In conclusion, we systematically investigated and compared the O vacancy formation and the mechanism of lattice-oxygen evolution in the pristine and S-substituted LNMO (003) surfaces in the presence of electrolyte mixture using DFT and AIMD simulation methods. The structural and electronic properties of the pristine LNMO (003) surface are analyzed during delithiation, and some over-oxidized O anions are observed at a high level of delithiation, and these O anions undergo oxygen evolution, causing O vacancy formation. We found that the O vacancy formation on the pristine LNMO (003) surface is thermodynamically favorable and forms spontaneously at a high degree of delithiation. The favorable formation of O vacancy implies that oxygen evolution and release could easily occur on the pristine surface. However, the oxygen formation and O vacancy on the LNMO surface can be significantly suppressed by S-substitution at the O site because of the formation of (SO2)n−/(SO3)m− species associated with the electron buffer behavior; these species primarily participate in charge compensation and further preserve the reversibility of the O2−/O2n− redox reaction at a higher level of delithiation. Additionally, the formation of (SO2)n−/(SO3)m− species also creates appropriate O vacancies on the S-substituted surface. It is noticed that appropriate O vacancies can reduce charge transfer resistance and increase the capacity and the rate of charging and discharging of the LNMO cathode material11. Moreover, (SO2)n−/(SO3)m− species inhibit the excess formation of O vacancies resulting from the oxygen evolution, thereby preventing severe structural deformation at a high level of delithiation. Besides, S-substitution can effectively prevent the formation of Ni3+ ions, inhibiting the Jahn-Teller distortion during delithiation. According to the delithiated structures, we observed that the structural deformation of S-substituted LNMO (003) during delithiation is negligible, and the layered structure is maintained during cycling. Our results contribute to the understanding of the oxygen evolution mechanism in LNMO cathode materials, with a particular emphasis on a strategy for suppressing lattice-oxygen formation for developing high-performance cathode materials with high reversibility and high structural stability for LIBs.

Methods

The DFT and AIMD calculations were performed using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)40,41,42. The generalized-gradient approximation (GGA) and the long-range dispersion correction incorporated in the optB88-vdW functional was adopted to describe the van der Waals (vdW) interactions43. The Hubbard U corrections of 5.96 and 5.10 eV were considered to include the self-interaction energy of the correlated d-electrons of Ni and Mn atoms in the system, respectively44,45. Similar to our previous study36, we considered bulk LNMO unit cell with the rhombohedral symmetry (R\(\bar 3\)m space group). All the geometrical parameters are relaxed until the total energy is converged to 10−4 eV and the Hellmann−Feynman forces are smaller than 0.01 eV/Å. The optimized structure of bulk LNMO unit cell and simulated XRD pattern are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. In comparison to previous experimental XRD patterns, both our simulated and experimental results demonstrate the (003) orientation as the preferred one31,36,46. Furthermore, we considered different terminations, such as O-terminated, TM-terminated, and Li-terminated surfaces. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates the optimized structures and total energy of each termination surface. Accordingly, the Li-terminated LNMO (003) surface shows the lowest total energy and was constructed for the following calculations.

To study the doping effects on oxygen evolution and structural stability during delithiation, we considered sulfide anion (S−2) doping into the first layer of the O site in the LNMO (003) surface. A suitable site for sulfide anion substitution was determined by calculating the formation energies (Ef) of S−2 anions substituted at different O sites of the LNMO (003) surface, which is defined as Eq. (2)47

where, Edoped and Ecell are the total energies of the S-substituted LNMO (003) surface and pristine surface structure, respectively. ES and EO are the total energies of one S atom and one O atom from the gaseous S8 and O2 molecule calculations, respectively. The optimized structures and calculated formation energy values for different substitution sites on the LNMO (003) surface are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. Lower values indicate that the surface is thermodynamically more favorable. Supplementary Fig. 4 demonstrates that configuration (b) exhibits the most favorable formation of S-substitution with the formation energy of 0.29 eV. We also considered the thermodynamic stability of S-substitution (configuration b) at varying temperatures, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The formation of S-substitution is thermodynamically favorable, and the formation will occur spontaneously when the temperature increases to 500 K. Moreover, for the investigation into the formation of O vacancy, the formation energy of O vacancy on the pristine and S-substituted LNMO surfaces is evaluated by the following Eq. (3)

where Esurface with O vacancy, Esurface, and \({\rm{E}}_{{\rm{O}}_2}\) are the total energies of the LNMO (003) surface in the presence and absence of O vacancy and the oxygen molecule, respectively.

To study the oxygen evolution in the LNMO (003) surface, we constructed a cathode/electrolyte interface to study the influences of electrolytes on the structural stability of Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 cathode materials in different delithiation states using AIMD simulations. Organic electrolytes often consist of mixtures of multiple solvents and different lithium salts. In this study, we considered Li salt (LiPF6) and the solvent mixture (ethylene carbonate (EC) and diethyl carbonate (DEC)) and optimized these molecules at the B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) level of theory using the Gaussian 09 package48,49,50,51. The p(4 × 1) supercell of the LNMO (003) surface is generated to performed AIMD simulations for 1 M LiPF6 in an EC/DEC mixture (3:7 v/v%). The numbers of EC and DEC molecules in the simulation cell were chosen as 4 and 6, corresponding to densities of 1.32 and 0.975 g cm−3 for EC and DEC, respectively. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 1 × 1 × 1 Gamma k-point mesh, and the cut-off energy of the plane-wave basis expansion was set to 500 eV. The convergence criteria for electronic self-consistent iteration were set to 10−4. Besides, we considered one layer of He atoms and fixed their positions to prevent the electrolyte interactions between the neighboring slabs due to the periodic boundary conditions in the AIMD simulations. To simulate the delithiation process, a step-by-step delithiation process was performed on the Li1.2 − xNi0.2Mn0.6O2 (003) surface by removing four lithium atoms at a time. After removing four lithium atoms, the AIMD simulations were equilibrated at 400 K in a canonical ensemble (NVT) for a total time of 5 ps with a time interval of 1 fs. Then, we optimized the LNMO structures with electrolytes according to the lowest total energy over the final half of the trajectory for further electronic analyses such as Bader charge and projected densities of states (PDOS)52,53. Figure 8 shows an overview of the AIMD simulation procedure carried out in this study.

The five steps include 1. Surface optimization from the p(4 × 1) supercell of the LNMO (003) surface, 2. The development of AIMD models with electrolytes, 3. The AIMD simulations equilibrated at 400 K in a canonical ensemble (NVT) for a total time of 5 ps with a time interval of 1 fs, 4. The optimization of LNMO structures according to the lowest total energy over the final half of the trajectory, and 5. The analysis of Bader charge and projected density of states (PDOS).

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the paper and its associated Supplementary Information. All other relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All density functional theory calculations in this work were performed using the VASP code (version 5.4.4), which is a licensed software package.

References

Zhao, S., Yan, K., Zhang, J., Sun, B. & Wang, G. Reaction mechanisms of layered lithium-rich cathode materials for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2208–2220 (2021).

Cui, S.-L., Gao, M.-Y., Li, G.-R. & Gao, X.-P. Insights into Li-rich Mn-based cathode materials with high capacity: from dimension to lattice to atom. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2003885 (2021).

Zeng, X. et al. Commercialization of lithium battery technologies for electric vehicles. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900161 (2019).

Zuo, W. et al. Li-rich cathodes for rechargeable Li-based batteries: reaction mechanisms and advanced characterization techniques. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 4450–4497 (2020).

Jiang, M., Danilov, D. L., Eichel, R.-A. & Notten, P. H. L. A review of degradation mechanisms and recent achievements for Ni-rich cathode-based Li-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2103005 (2021).

Liu, Y., Zhu, Y. & Cui, Y. Challenges and opportunities towards fast-charging battery materials. Nat. Energy 4, 540–550 (2019).

Assat, G. & Tarascon, J.-M. Fundamental understanding and practical challenges of anionic redox activity in Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 373–386 (2018).

Hu, S. et al. Li-rich layered oxides and their practical challenges: recent progress and perspectives. Electrochem. Energ. Rev. 2, 277–311 (2019).

Nayak, P. K. et al. Review on challenges and recent advances in the electrochemical performance of high capacity Li- and Mn-rich cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702397 (2018).

Zheng, J. et al. Li- and Mn-rich cathode materials: challenges to commercialization. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1601284 (2017).

Tang, Z.-K., Xue, Y.-F., Teobaldi, G. & Liu, L.-M. The oxygen vacancy in Li-ion battery cathode materials. Nanoscale Horiz. 5, 1453–1466 (2020).

Hu, W., Wang, H., Luo, W., Xu, B. & Ouyang, C. Formation and thermodynamic stability of oxygen vacancies in typical cathode materials for Li-ion batteries: density functional theory study. Solid State Ion. 347, 115257 (2020).

Posada-Pérez, S., Hautier, G. & Rignanese, G.-M. Effect of aqueous electrolytes on LiCoO2 surfaces: role of proton adsorption on oxygen vacancy formation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 110–119 (2022).

Yan, P. et al. Injection of oxygen vacancies in the bulk lattice of layered cathodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 602–608 (2019).

Kong, F. et al. Kinetic stability of bulk LiNiO2 and surface degradation by oxygen evolution in LiNiO2-based cathode materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1802586 (2019).

Erickson, E. M. et al. Review—recent advances and remaining challenges for lithium ion battery cathodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, A6341–A6348 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Three-dimensional fusiform hierarchical micro/nano Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 with a preferred orientation (110) plane as a high energy cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 5942–5951 (2016).

Sathiya, M. et al. Origin of voltage decay in high-capacity layered oxide electrodes. Nat. Mater. 14, 230–238 (2015).

Zheng, J. et al. Mitigating voltage fade in cathode materials by improving the atomic level uniformity of elemental distribution. Nano Lett. 14, 2628–2635 (2014).

Zheng, J. et al. Corrosion/fragmentation of layered composite cathode and related capacity/voltage fading during cycling process. Nano Lett. 13, 3824–3830 (2013).

Li, Q. et al. Improving the oxygen redox reversibility of Li-rich battery cathode materials via Coulombic repulsive interactions strategy. Nat. Commun. 13, 1123 (2022).

Sharifi-Asl, S., Lu, J., Amine, K. & Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Oxygen release degradation in li-ion battery cathode materials: mechanisms and mitigating approaches. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900551 (2019).

Sharpe, R. et al. Redox chemistry and the role of trapped molecular O2 in Li-rich disordered rocksalt oxyfluoride cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21799–21809 (2020).

Chen, H. & Islam, M. S. Lithium extraction mechanism in Li-Rich Li2MnO3 involving oxygen hole formation and dimerization. Chem. Mater. 28, 6656–6663 (2016).

Grimaud, A., Hong, W. T., Shao-Horn, Y. & Tarascon, J. M. Anionic redox processes for electrochemical devices. Nat. Mater. 15, 121–126 (2016).

Seo, D.-H. et al. The structural and chemical origin of the oxygen redox activity in layered and cation-disordered Li-excess cathode materials. Nat. Chem. 8, 692–697 (2016).

Zhang, X.-D. et al. Suppressing surface lattice oxygen release of Li-rich cathode materials via heterostructured spinel Li4Mn5O12 coating. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801751 (2018).

Yu, R. et al. Effect of magnesium doping on properties of lithium-rich layered oxide cathodes based on a one-step co-precipitation strategy. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 4941–4951 (2016).

Song, J.-H. et al. Anionic redox activity regulated by transition metal in lithium-rich layered oxides. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001207 (2020).

Gao, Y., Wang, X., Ma, J., Wang, Z. & Chen, L. Selecting substituent elements for Li-rich Mn-based cathode materials by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Chem. Mater. 27, 3456–3461 (2015).

Lo, W. T., Yu, C., Leggesse, E. G., Nachimuthu, S. & Jiang, J. C. Understanding the role of dopant metal atoms on the structural and electronic properties of lithium-rich Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 4842–4850 (2019).

Nayak, P. K., et al. Al Doping for Mitigating the Capacity Fading and Voltage Decay of Layered Li and Mn-Rich Cathodes for Li-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, (2016).

Jiang, Q., Liu, D., Zhang, H. & Wang, S. Plasma-assisted sulfur doping of LiMn2O4 for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 28776–28782 (2015).

Zhao, Y. et al. Uncovering sulfur doping effect in MnO2 nanosheets as an efficient cathode for aqueous zinc ion battery. Energy Stor. Mater. 47, 424–433 (2022).

An, J. et al. Insights into the stable layered structure of a Li-rich cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 19738–19744 (2017).

Nachimuthu, S., Huang, H.-W., Lin, K.-Y., Yu, C. & Jiang, J.-C. Direct visualization of lattice oxygen evolution and related electronic properties of Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 cathode materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 563, 150334 (2021).

Dixit, M. et al. Thermodynamic and kinetic studies of LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O2 as a positive electrode material for Li-ion batteries using first principles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 6799–6812 (2016).

Zeng, D., Cabana, J., Bréger, J., Yoon, W.-S. & Grey, C. P. Cation ordering in Li[NixMnxCo(1–2x)]O2-layered cathode materials: a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), pair distribution function, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, and electrochemical study. Chem. Mater. 19, 6277–6289 (2007).

Xu, B., Fell, C. R., Chi, M. & Meng, Y. S. Identifying surface structural changes in layered Li-excess nickel manganese oxides in high voltage lithium ion batteries: a joint experimental and theoretical study. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2223–2233 (2011).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Klimeš, J., Bowler, D. R. & Michaelides, A. Chemical accuracy for the van der Waals density functional. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 022201 (2009).

Liechtenstein, A. I., Anisimov, V. I. & Zaanen, J. Density-functional theory and strong-interactions-orbital ordering in mott-hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B. 52, R5467–R5470 (1995).

Hinuma, Y., Meng, Y. S., Kang, K. S. & Ceder, G. Phase transitions in the LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2 system with temperature. Chem. Mater. 19, 1790–1800 (2007).

Lin, M. H. et al. Revealing the mitigation of intrinsic structure transformation and oxygen evolution in a layered Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 cathode using restricted charging protocols. J. Power Sources 359, 539–548 (2017).

Lin, K. Y., Nguyen, M. T., Waki, K. & Jiang, J. C. Boron and nitrogen Co-doped graphene used as counter electrode for iodine reduction in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 26385–26392 (2018).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Lee, C. T., Yang, W. T. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron-density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Stephens, P. J., Devlin, F. J., Chabalowski, C. F. & Frisch, M. J. Ab-initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular-dichroism spectra using density-functional force-fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623–11627 (1994).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT (2009).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jonsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

Tang, W., Sanville, E., Henkelman, G. A grid-based Bader analysis algorithm without lattice bias. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 21, 084204 (2009).

Acknowledgements

All the authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 110-2639-E-011-001-ASP, MOST 110-2923-E-011-002 and MOST 110-2923-M-011-003-MY2). The authors are also thankful to the National Center of High-Performance Computing (NCHC) for donating computer time and facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y.L. and H.W.H. performed the computations under the supervision of J.C.J. All authors discussed the computational results and contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, KY., Nachimuthu, S., Huang, HW. et al. Theoretical insights on alleviating lattice-oxygen evolution by sulfur substitution in Li1.2Ni0.6Mn0.2O2 cathode material. npj Comput Mater 8, 210 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00893-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00893-6

This article is cited by

-

Unraveling the role of Fe and Ni in oxygen evolution reaction on pentlandite using three generations of computational surface models

npj Computational Materials (2026)

-

A study of the thermodynamic stability of lattice oxygen in Li-rich cathode Li1.25Ni0.5Mn0.25O2 during operation

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2025)

-

Enhanced electrochemical performance of Li-rich cathode materials at high temperatures through fluorine and magnesium modification

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2024)