Abstract

Strain engineering is a widely used technique for enhancing the mobility of charge carriers in semiconductors, but its effect is not fully understood. In this work, we perform first-principles calculations to explore the variations of the mobility of electrons and holes in silicon upon deformation by uniaxial strain up to 2% in the [100] crystal direction. We compute the π11 and π12 electron piezoresistances based on the low-strain change of resistivity with temperature in the range 200 K to 400 K, in excellent agreement with experiment. We also predict them for holes which were only measured at room temperature. Remarkably, for electrons in the transverse direction, we predict a minimum room-temperature mobility about 1200 cm2 V−1 s−1 at 0.3% uniaxial tensile strain while we observe a monotonous increase of the longitudinal transport, reaching a value of 2200 cm2 V−1 s−1 at high strain. We confirm these findings experimentally using four-point bending measurements, establishing the reliability of our first-principles calculations. For holes, we find that the transport is almost unaffected by strain up to 0.3% uniaxial tensile strain and then rises significantly, more than doubling at 2% strain. Our findings open new perspectives to boost the mobility by applying a stress in the [100] direction. This is particularly interesting for holes for which shear strain was thought for a long time to be the only way to enhance the mobility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Semiconductors are the core of the electronics industry. In particular, silicon is the most used material due to its electronic performances and the mature CMOS technology, leading to reduced manufacturing cost1. However, the relatively low electron (resp. hole) mobility of silicon compared to other semiconductors such as GaN2,3 and InGaAs4,5 (resp. Ge6) limits its use in high-speed devices, essential for optical7,8 and microwave9,10 communications.

Elastic strain is a proven technique to boost the performances of semiconductors, in particular to increase the mobility of their charge carriers at low additional cost11. Mechanical stress can be applied using different types of microfabrication schemes such as substrate-induced12,13, on-chip actuator14,15 or pressure-induced membrane16,17 methods.

The deformation of the crystal structure has, in fact, several possible benefits. It can be used for tuning the band gap in a range favorable for optoelectronic applications18,19, for varying the vibrational energies that can be exploited in metrology such as Raman spectroscopy20, and for modifying the carrier mobilities which can be used for strain sensing21, or to improve the conductivity of electronic devices22. The type of deformation applied to the crystal (uniaxial, biaxial, or hydrostatic) and the direction of the applied stress are critical for tuning the semiconductor properties23,24.

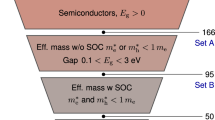

The mobility enhancement in strained devices is a well-known mechanism that has already been exploited to develop semiconductor strain gauges or high-mobility silicon transistors25,26. Different theoretical methods have been elaborated to predict the improvement or degradation of the mobility, starting from an empirical linear model27 valid at low strain, and later based on semi-empirical analysis using the calculated band structure of strained silicon24. The band structure and its strain dependence can be theoretically computed using semi-empirical approaches based on fitting parameters such as the k ⋅ p method28,29, empirical pseudopotentials30, and the tight-binding method31,32, or with ab initio computations based on density-functional theory (DFT) that do not require fitting parameters33. Previous mobility models were based on the theoretical knowledge of the band structure but they relied on empirical parameters for the electron-phonon scattering34,35 that is important in the transport mechanism in silicon. Only recently, first-principles calculations of the Boltzmann transport equation (BTE) have become available within EPW36,37, PERTURBO38, PHOEBE39 or ABINIT40,41, which made it possible to predict the mobility in semiconductors fully-theoretically42. These new techniques can now be used to compute the mobility variation in a deformed crystal from first principles, without the empirical bias.

In this work, the mobility variation for holes and electrons is computed from first principles for silicon tensely strained (up to 2%) in the [100] direction, and measured for n-doped sample, up to 1%, in the same crystallographic direction. The presented method is general and can be used for any strain type and direction for any semiconductor for which the mobilities are limited by the electron-phonon scattering. We find excellent agreement for the electron and hole mobility variations with strain and temperature compared to experimental data. In particular, resorting to first-principles calculations is found to be particularly crucial for the holes for which the proximity of the valence bands and the important modification of their shapes under strain conditions limit the accuracy that can be achieved when adopting an analytic approach. In addition, the calculations allow the study of intrinsic phenomena that cannot be achieved experimentally due to the challenge of obtaining low-doped samples43.

Results

Impact on the electronic structure

A direct impact of the crystal deformation under uniaxial tensile strain is the modification of the band structure, particularly the variations of the band edges, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In silicon, the six electron valleys are located along the high-symmetry path from Γ towards X while the top of the valence bands is located at Γ. The spin-orbit (SO) valence band is slightly separated (~47 meV) from the heavy-hole (HH) and light-hole (LH) valence bands due to the spin-orbit coupling (SOC). Under uniaxial stress in the [100] direction, the degeneracy of the conduction band minima is lifted and the two valleys (Δ2) along the symmetry path longitudinal to the stress direction increase in energy while the four others (Δ4) decrease, as shown in Fig. 1b. This effect increases the electron population at the conduction minima while decreasing it for the higher energy valleys. The variations of the band edges due to stress applied in the [100] direction with and without SOC taken into account are shown in Fig. 1c. In the case of the valence bands, the strain slightly separates the HH and LH bands up to 28 meV at 2% while pushing further down the SO band by 200 meV at 2% deformation. Apart from a reduction of the band gap of 17 meV, the edge variations of the electron valleys are not strongly impacted by the inclusion of SOC in the calculation.

a Illustration of the deformation of the silicon conventional cell under an applied stress along the [100] crystal direction and the reciprocal space equipotential surface of the six electron-valleys (brown) with the lift of the degeneracy between the Δ2-valleys (red) and the Δ4-valleys (blue). b Impact on the extrema of the valence bands and conduction bands. The density of states (DOS) of the three valence bands and the two valleys are indicated next to the band structure. Dashed brown curves are used for the unstrained case. c Band edges variations of the Δ4-valleys (blue), Δ2-valleys (red), heavy-hole (HH) band (orange), light-hole (LH) band (dark green) and spin-orbit (SO) band (light green) with the strain with spin-orbit coupling taken into account (continuous line) and without (dashed line). The energy is scaled to the valence band maximum at zero strain while the band gap (Eg) is obtained from the energy difference between the band edges.

The directional effective masses for the three valence bands (HH, LH and SO) have been computed using the second derivatives of the band energy along the [100], [001], [110], and [111] crystal directions and are shown in Fig. 2a–c, respectively. The high anisotropy of the HH band is reduced under uniaxial tensile strain as the effective masses in the [110] (resp. [111]) direction present a strong reduction from 0.539 me (resp. 0.678 me) to 0.203 me (resp. 0.223 me) at 0.03% strain. The LH band presents a sharp increase in the presence of strain, going from 0.137 me to 0.235 me for the masses computed in the [110] direction and from 0.130 me to 0.214 me for the ones computed in the [111] direction. The values in the absence of strain are discontinuous for the effective masses in the [001], [110] and [111] directions of the HH and LH bands due to the removal of band degeneracy. We illustrate in Fig. S1 of the SI44 this discontinuity between a strain-free structure and that strained at 0.03% by computing the electronic density at the zone center. We find that the density in the strain direction (heavy hole) stretches significantly while the transverse direction’s density, light hole, is reduced and less affected. The strain breaks the isotropy of the effective masses computed for the SO band that presents the same value of 0.224 me in the absence of strain. The electron effective masses are only computed along the [100] and [001] directions as the electron valleys have a regular ellipsoid shape that is preserved under this strain condition. The directional effective masses for the Δ2- and Δ4-valleys present small linear variations with the strain compared to the holes effective masses, as shown in Fig. 2d. The decrease (resp. increase) of the longitudinal component and the increase of the transverse one (resp. decrease) of the Δ4-valleys (resp. Δ2-valleys) are the sign of an elongation (resp. compression) of the ellipsoid shape that is formed by the equipotential surfaces, as illustrated in Fig. 1a.

Effective masses as a function of strain computed at the maxima of the valence bands along the [100], [001], [110] and [111] crystal directions for (a) the heavy-hole (HH) band (orange), (b) the light-hole (LH) band (dark green), and (c) the spin-orbit (SO) band (light green) with spin-orbit coupling included. d Effective masses computed at the minima of the conduction bands along the longitudinal and transverse directions for the Δ4-valleys (blue) and Δ2-valleys (red). e Valence density-of-states effective mass with the contribution of the three valence bands and (f) the conduction density-of-states effective mass with the contribution of the two types of valleys. The values in the absence of strain are discontinuous for the effective masses in the [001], [110], and [111] directions of the HH and LH bands and are not shown here.

The density-of-states (DOS) effective mass of a band is computed by integrating the DOS and is defined as the one giving the same density of states as if the band was parabolic. In the case of the valence band, it is obtained through45,46

where Ev is the energy of the valence band maximum and g(E) is the density of states integrated on a dense 150 × 150 × 150 momentum grid for each strained configuration. The energy integral makes it possible to take into account the lift of the degeneracy due to strain to retrieve a global DOS effective mass.

The evolution of the DOS effective masses is shown in Fig. 2e for the holes and Fig. 2f for the electrons. In silicon, the DOS effective mass of holes is dominated by the top band (HH) with the largest mass going down from 0.723 me to 0.498 me at 2%-strain, while the two other valence bands are pushed away due to strain. As the strain increases, the Δ2-valleys increase in energy compared to the Δ4-valleys and the contribution of the formers to the global DOS effective mass decreases. In the absence of strain, the global conduction effective mass gathers contributions from all 6 valleys equally and is of 1.116 me. At 1% strain, the global DOS effective mass is equal to that of the Δ4-valleys, i.e., 0.860 me.

Finally, in Table S1 of the SI44, we compare directional effective masses obtained for unstrained silicon and strained at 1% to the existing literature. We find an excellent agreement with experiment except for the HH band in the [001] direction where an underestimation of a factor of two is observed between the experimental observation and the computed value. This disagreement on the [001] effective mass of the HH band between experiment and first-principles calculations has been reported many times47,48,49,50,51 and is still an open question. Interestingly, all the masses (including HH [001]) found for the strained silicon are in good agreement with the literature, both at 0.1% compared to the experimental values measured52 for the HH and LH bands and at 1% with regards to other theoretical calculations49.

Phonon-limited mobility

In the low-field limit, the carrier mobility μαβ is defined as the ratio between the electrical conductivity σαβ and the product of the electron charge e by the carrier density nc:

where α and β are Cartesian directions. The conductivity is obtained by solving iteratively the BTE42 with the approach described in the methods section, which involves the direct calculation of the scattering rates \({\tau }_{n{\bf{k}}}^{-1}\) and electronic velocity vnk of a state with band index n and electron momentum k.

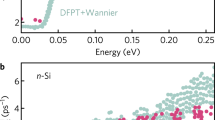

Figure 3a presents the phonon-limited scattering rates \({\tau }_{n{\bf{k}}}^{-1}\) computed for all k points with energy states near the minimum of the conduction band or the maximum of the valence band for a 0%, 0.3%, and 1%-strain and for a temperature of 200 K, 300 K, and 400 K. As the temperature increases from 200 K to 400 K, the maximum scattering rates in the absence of strain increase by 72% for the electrons and 52% for the holes as the temperature rises. The phonon band structure is only slightly altered by strain, resulting in a negligible impact on the scattering variations. An increase of 76% for the electrons and 54% for the holes is observed at 1% strain as the temperature rises from 200 K to 400 K. The evolution of the phonon band structure and the shift in the phonon energy due to strain are discussed in Fig. S2 of the SI44.

a Scattering rates for all relevant k points under 0%, 0.3%, and 1%-strain at 200 K (blue dots), 300 K (orange dots) and 400 K (red dots). The strain level is indicated on the right of the figure. The black lines are the scattering rates density at the three temperatures. b Scattering rates for all relevant k points at 300 K under strain ranging from 0% (blue) to 2% (red). The panels show the hole (left) and electron (right) scattering rates. The intravalley contribution of the electron scattering rates at 0%-strain dominates for energy below 53 meV and is highlighted (gray area), while the intervalley scattering is seen at higher energies. The minimum and maximum of the conduction and valence bands are indicated by Ec,0 and Ev,0, respectively.

In silicon, the electron scattering can be divided into two categories: intravalley scattering, where long-wavelength phonons (q → 0) scatter the electrons within a single valley (Δ2- or Δ4-valley), and intervalley scattering, where electrons scatter from one valley to another due to short-wavelength phonons (large q). Similarly, the hole scattering is described by intraband scattering, where phonons scatter a hole within a single band (LH, HH or SO), and interband scattering, where the holes are scattered from one band to another. Figure 3b presents the scattering rates at 300 K for the different strain levels. To get a deeper understanding, the intravalley scattering contributions have also been explicitly calculated by considering only higher-wavelength phonon modes with a norm ∣q∣ < 0.06 bohr−1. The results are given in Fig. S3a of the SI44. In the vicinity of the conduction band minimum (up to 53 meV at 0%-strain), intravalley scattering prevails for the electrons, as confirmed by Yang et al.53. More specifically, the calculations show the independence of the intravalley scattering with strain, as both the phonon band structure and the shape of the valley do not change significantly. In contrast, for energies above 53 meV, intervalley scattering becomes the dominant process but it is reduced by the splitting of the electron valleys with strain. Therefore, the energy limit between intra- and intervalley scattering increases linearly with strain and reaches 63 meV at 1%-strain. At higher strain, all electrons occupy the Δ4-valleys, resulting in a reduction of intervalley scattering by approximately one-third, as observed in the right panel of Fig. 3b. For the holes, the scattering rate is dominated by the intraband scattering of the HH band as shown in Fig. S3b of the SI44. The LH intraband scattering is almost one order of magnitude smaller than the HH scattering, similarly to the interband scattering. It can be observed that the intraband scattering is significantly impacted at low strain due to the variations of the band shapes around the Γ-point, as illustrated by the effective mass variations in Fig. 2. Furthermore, the splitting between the HH and LH bands, reaching a separation of 28 meV at 1%-strain, causes a reduction in the interband scattering. However, this has a limited impact on the total scattering rate.

The components of the electronic velocity vnk,α are shown in Fig. 4 as a function of state energy for different strain configurations. The separation of the Δ4-valleys and the Δ2-valleys leads to a separation of the longitudinal component of the velocity vnk,x (oriented along the direction of the applied stress) and the transverse components vnk,y and vnk,z.

Band velocities along the three Cartesian directions for all relevant k points under 0%, 0.3%, and 1%-strain indicated on the right of the figure. The velocities in the x, y, and z directions are indicated with blue, orange, and red dots, respectively. The minimum and maximum of the zero-strain conduction and valence bands are indicated by Ec,0 and Ev,0, respectively. The continuous and dashed lines represent the velocity density of the longitudinal (vnk,x) and transverse (vnk,y, vnk,z) components, respectively. They have been computed using linear-tetrahedron method88 with steps of 25 meV.

The room-temperature electron and hole mobilities attained at longitudinal strain levels up to 2% are shown in Fig. 5. Spin-orbit coupling has been taken into account and lead to significant change for holes but not for electron mobility and is discussed in detail in the next section. Under the applied strain conditions, the mobility tensor is no longer isotropic and gives rise to longitudinal and transverse mobilities. As can be seen, first-principles computations are able to reproduce the nonlinear behavior of the mobility with increasing strain, especially at larger strain levels for the electron mobility that saturates around 1%-strain at 2249 cm2 V−1 s−1 for the longitudinal component and 1321 cm2 V−1 s−1 for the transverse one, while the zero-strain mobility is 1366 cm2 V−1 s−1. Remarkably, we find a minimum in the transverse electron mobility at 0.3% strain with a value of 1195 cm2 V−1 s−1. In relaxed silicon, the longitudinal and transverse components are identical, and the six electron valleys contribute to the mobility. For the mobility in a specific Cartesian direction, the two valleys along this direction contribute with their low longitudinal curvature and velocity, while the four others contribute with their high longitudinal curvature and velocity. The reduction at low strain is explained by the significant depletion of electrons from the Δ2-valleys to the Δ4-valleys due to the energy splitting. The difference in valley occupancy results in the differentiation between the longitudinal and transverse mobility components. Additionally, the longitudinal mobility is oriented along the transverse axis of the Δ4-valleys, with low curvature resulting in a notable increase in mobility. On the other hand, the two equivalent transverse mobilities are oriented both longitudinally to two Δ4-valleys and transversely to the two others. The calculation of this component combines both low curvature from the transverse axis and high curvature from the longitudinal axis, resulting in a pronounced reduction of the mobility, particularly at lower strain levels. This is in contrast with the relaxed value, which considers two transverse curvatures and one longitudinal curvature from the valleys oriented along the transport direction. The reduction of intervalley scattering tends to increase the mobility. However, this is hidden at lower strains by the depletion of electrons into the lower energy valleys. At approximately 0.3%, more than 80% of the electron population can be found in the Δ4-valleys, and the increase due to the reduced scattering rates begins to be visible for the transverse mobility. At levels above 1%, the vast majority of electrons are localized in the Δ4-valleys and no longer interact with the Δ2-valleys, resulting in a stable intervalley scattering with the strain.

Phonon-limited mobilities as a function of the longitudinal strain in the transverse (green for the electrons and orange for the holes) and longitudinal (blue for the electrons and red for the holes) directions of the applied stress in the [100] crystal direction. The experimental data (white dots) have been obtained by scaling and offsetting the resistance variations obtained experimentally by the zero-strain mobility, i.e., 1366 cm2V−1s−1. The experimental linear model using the piezoresistive coefficients from Smith60 is indicated with the dashed black lines while the computation of the electron mobilities from Ma et al.69 and Ungersboeck et al.35 are represented by dotted and dash-dotted lines.

The change in resistivity of the transverse and longitudinal components was measured on a n-doped silicon sample with a doping level of approximately 5 × 1017 cm−3. The relative variations were scaled and offset by the zero-strain mobility, i.e., 1366 cm2 V−1 s−1. This was done to enable comparison of the experimental results with the theoretical ones. Excellent agreement was found, as illustrated by the white circles in Fig. 5. Although doping can affect the absolute value of mobility54, the relative variations in mobility with strain are not significantly influenced by doping, as evidenced both theoretically27 and experimentally55. It has been shown that ionized impurity scattering acts as a screening and renormalization of the intrinsic phonon-limited mobility42,51. The stress has been applied on the devices using a four-point bending equipment that brings constant strain field on the sample43. Strain levels up to 1% have been accurately measured using an aluminum strain gauge as reference bonded next to the silicon sample. The experimental results show the same trend as the first-principles calculations, with a saturation of the electron mobility for the longitudinal component starting at around 0.5%, but with a reduced intensity. The transverse mobility decreases similarly to the calculations but reaches a minimum just before the 0.3%-strain minimum, to finally reach the same reduction of about −3.4% at a strain of 1%. The enhancement (resp. reduction) found experimentally is 51% at 1%-strain (resp. −7% at 0.3%-strain) for the longitudinal (resp. transverse) component. The doped sample shows smaller variations compared to the theoretical values of 65% and −12.5% for the longitudinal and the transverse mobilities, respectively.

Since carrier mobility decreases with increase doping56, we expect a larger increase of mobility with strain when using a lower doping sample, even closer to the theoretical prediction. The hole mobility at zero strain is about 609 cm2V−1s−1, in agreement with previous calculations40,57, and presents initially little enhancement but strongly increases for strain levels above 0.4% to reach 1340 cm2V−1s−1 and 1330 cm2V−1s−1 for the longitudinal and transverse components at 2%, respectively. The obtained results highlight, for the first time, the potential of uniaxial strain in the [100] direction for hole mobility enhancement in both directions. We stress that these strain levels are achievable with microfabrication processes14,58,59, more than doubling the hole mobility, which could transform the high-speed sector of the semiconductor industry. These electron and hole mobility predictions as a function of strain and their experimental confirmation represent one of the key result of this work.

Importantly, the linear behavior of the mobility at low strain gives a direct access to piezoresistive coefficients. Indeed, at low strain level, a linear relation can be used to express the relative variation of the resistivity as a function of the applied stress60:

where πij are the piezoresistive coefficients using the Voigt notation61,62, σαβ are the stress components and \(\Delta {\rho }_{\alpha \beta }=({\rho }_{\alpha \beta }-{\rho }_{\alpha \beta }^{0})/{\rho }_{\alpha \beta }^{0}\) are the relative variations of the resistivity components with respect to the unstrained situation \({\rho }_{\alpha \beta }^{0}\). In the low electric field regime, the resistivity variation is inversely proportional to the change of carrier mobility:

Under a uniaxial stress applied in the [100] direction, the longitudinal and transverse mobility variations are respectively given by

where εxx is the longitudinal strain component and s11 = 6.032 TPa−1 is the principal stiffness component62.

In the case of silicon, the π44 piezoresistive coefficient determines the resistivity variations under shear strain. The shear coefficient is significant for the holes and has already been well studied with values ranging from 1018 TPa−1 to 1381 TPa−1 at 300 K for slightly doped samples60,63,64,65,66. The results obtained in this work however demonstrate that the shear contribution no more dominates the enhancement of the hole mobilities as the strain increases. The π44 coefficients for the electron is less important than π11 and π12 with values ranging from -123 TPa−1 to -200 TPa−1 at 300 K for slightly doped samples55,60,64. Here, this coefficient is not accessible with uniaxial strain along the [100] crystal direction. In contrast, the two piezoresistive coefficients π11 and π12 for the holes have been much less investigated while few works55,60,64 manage to obtain the coefficients for the electrons at low impurity concentration due to the challenge of producing low-doped samples. They can be respectively computed from the slope of the longitudinal and transverse mobility variations for the holes and electrons at low strain level. In practical terms, the slope has been calculated by taking the mobility variations between 0%-strain and 0.03%-strain. The values of the hole (resp. electron) coefficient is 148 TPa−1 (resp. -989 TPa−1) for π11 and -72 TPa−1 (resp. 502 TPa−1) for π12. The coefficients computed from the experimental results are -632 TPa−1 and 403 TPa−1 for the longitudinal and transverse contributions, respectively.

Previous experimental measurements of the piezoresistive coefficients for p-type and n-type silicon at low strain level are summarized in Table 1. The coefficients measured by Smith60 are also used in Fig. 5. The coefficients extracted from the first-principles results are in good agreement for electrons but slightly differ for holes. We suspect that the impurity scattering resulting from the fabrication and doping processes introduces a deviation among experimental measurements43,67 in addition to the reduction of the measured coefficients55,64, as shown in Table 1. It has been shown that despite the significant effect of strain on zero-strain mobility54,68, the relative changes due to strain are much less sensitive to the doping level when it is maintained at a low or moderate level27,55. In addition, the small variations associated with the non-linear behavior of the hole mobility introduce greater uncertainty into the experimental measurements at low strain64. Theoretical computations from Ungersboeck et al.35 and Ma et al.69 for the electron mobility have been able to reproduce the nonlinear behavior as represented in Fig. 5, but failed to predict the holes mobility due to the triple contributions of the valence bands (HH, LH, and SO) in addition to the high variations of the effective masses of those bands with the strain65,70. Here, the first-principles methodology is not restricted to single parabolic bands and constitute a novel computation method.

The temperature dependence of the mobilities and piezoresistive coefficients at low strain are presented in Fig. 6. The mobility variations present a typical T−1.5 decrease71, going from 3562 cm2 V−1 s−1 (resp. 1780 cm2 V−1 s−1) at 200 K to 601 cm2 V−1 s−1 (resp. 261 cm2 V−1 s−1) at 400 K for the electrons (resp. holes). The piezoresistive coefficients are less sensitive to the temperature but still decrease from -1265 TPa−1 (resp. 170 TPa−1) at 200 K to -816 TPa−1 (resp. 128 TPa−1) at 400 K for the longitudinal coefficient and from 676 TPa−1 (resp. -84 TPa−1) at 200 K to 411 TPa−1 (resp. -55 TPa−1) at 400 K for the transverse coefficient for the electrons (resp. holes). So far, the prediction of the temperature dependence of π11 and π12 has only be done relatively27, i.e., without computing the exact value of the coefficients.

a Phonon-limited mobilities and b piezoresistive coefficients as a function of temperature. The coefficients are computed by finite difference between the results at zero strain and 0.03% in the longitudinal direction (blue for the electrons and red for the holes) and transverse direction (green for the electrons and orange for the holes). Experiments by Smith60 and Tufte and Stelzer55 are indicated with white diamonds and black squares, respectively. The theoretical model from Kanda27 has been scaled using the piezoresistive values computed at 300 K, and is indicated with dotted lines.

Finally, we studied the impact of temperature together with the different strain levels as shown in Fig. 7. The impact is quite weak but we find that lower temperature samples show a smaller electron mobility variation with strain. The maximal value at 2%-strain of the longitudinal mobility increases by 50.3%, 63.1%, and 70.1%, and the transverse one decreases by 12.5%, 4.3%, and 0.3% at 200 K, 300 K, and 400 K, respectively. Regardless, the electron mobilities still present a saturation effect for strain larger than 1% and this limit is mainly related to the valleys splitting. As the strain increases, the electron population spreads on a larger energy range. The valley splitting needed to have all the carriers in the lower-energy valleys thus increases with the temperature. In contrast to electrons, the strain decreases the hole mobility with the temperature, going from an enhancement at 2%-strain of 155.7% at 200 K to 98.7% at 400 K for the longitudinal component and from 118.4% at 200 K to 107.2% at 400 K for the transverse one. As the temperature decreases, the hole population reduces into the upper HH band and partially in the LH band, which remain close to each other even at larger strains, as shown in Fig. 1. An important parameter for the enhancement (resp. reduction) of the high-strain mobilities for the electrons (resp. holes) with the temperature is the increase (resp. decrease) of the scattering rates variations with strain. The scattering rates to be considered are only the ones near the band edge where the carriers remain. As the temperature increases, scattering rates further away from the band edges starts to contribute to the mobility.

Relative variations of the phonon-limited mobilities with regards to the longitudinal strain for the electrons (blue for the longitudinal component and green for the transverse one) and the holes (red for the longitudinal component and orange for the transverse one) for a temperature of 200 K (dotted lines), 300 K (continuous lines), and 400 K (dashed lines). The zero-strain mobility is taken as a reference to compute the relative variations.

Discussion

The impact of SOC on the mobility enhancement for the holes at 300 K is shown in Fig. 8. The zero-strain value first shows an error around -5%, then the longitudinal component reaches a minimum value near 0% to finally increase up to -15% as the strain increases at 2%. An error of around -6% can be observed for the transverse component when the SOC is not considered. The curves for the transverse mobility are similar with and without the coupling taken into account but with an error factor while the discrepancy between the longitudinal mobilities vary with the strain.

Mobilities with longitudinal strain at 300 K (bottom panel) for the holes in the longitudinal (red) and transverse (orange) components with (continuous lines) and without (dashed lines) the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) taken into account, and the relative difference induced by the coupling (top panel).

Taking into account the coupling first lifts the degeneracy of the SO band, as shown in Fig. 1c. Furthermore, the linear strain dependence in absence of SOC of the SO and LH bands, respectively -97 meV/% and -7 meV/%, is showing non-linear trend at low strain when SOC is considered. The variations of these bands with SOC finally reached the same linear variations at high strain than without. The HH band variations do not show significant differences and maintain a linear variation of about -7 meV/% with and without SOC. The calculations with and without SOC did not present any significant difference for the electron mobilities as the coupling does not influence the shape and the splitting of the electron valleys51. In addition, the strain dependence of the valleys minima around -66 meV/% for the Δ4-valleys and 44 meV/% for the Δ2-valleys remain unchanged with the coupling taken into account, as shown in Fig. 1c.

Solving the Boltzmann transport equation instead of using an empirical model brings more confidence to the evolution of the electron mobility with the strain. Indeed, the studies from Ungersboeck et al.35 and Ma et al.69 seem to underestimate the enhancement factor at high-strain for the longitudinal component but we find the same mobility for the transverse one, as shown in Fig. 5. In addition, the low-strain variations predicted using first principles show excellent agreement with the experimental values found by Smith60. The analytical prediction of the electron mobility can be achieved as the variation mainly originates from the energies of one conduction band. Indeed, the band curvature, and so the effective mass, does not change significantly with the strain. The main phenomenon to be considered is then the energy shift between the Δ4− and Δ2−valleys that can be easily computed using DFT. Once all the electrons lie in the lower-energy valleys, the mobilities stabilize. The difference in the mobility shift of the longitudinal and transverse components is due to the difference in the longitudinal and transverse effective masses of the lower-energy valleys69. Other strain configurations with fourfold degenerated valleys lead to similar plateaus for both components. Strain configurations such as compressive uniaxial and tensile biaxial strain in the [100] direction or tensile uniaxial and compressive biaxial strain in the [110] direction present only a double-degenerated lower-energy valley that leads to larger mobility shifts, especially for the transverse component35,48,72.

The prediction of the hole mobility is more challenging using semi-empirical models. Indeed, the motion of the three valence bands (LH, HH and SO) has to be correctly predicted and the spin-orbit coupling has to be taken into account. Furthermore, important variations in the effective masses, which depend on the strain configuration applied to the material, have to be taken into account in addition to the distribution of holes between the valence bands. For these reasons, a first-principles scheme, such as the one presented here, is essential. The mobilities obtained by solving the iterative Boltzmann transport equation (IBTE) can be compared to the momentum relaxation time approximation (MRTA) or the self-energy relaxation time approximation (SERTA)73,74. The first approximation assumes only a component of the linear response in the direction of the band velocity and partially incorporates the effect of scattering, while the second approximation entirely neglect the rate for backscattering. The comparison between the SERTA, MRTA and IBTE results presented here are shown in Fig. S4 of the SI44. As expected, MRTA presents globally lower deviation (below 3%) compared to SERTA that shows a deviation as large as 7% (resp. 3%) for the electron (resp. hole) mobility in the longitudinal direction. The deviation with respect to the IBTE results is more important for the electrons under the SERTA, especially for the longitudinal contribution. The SERTA results for the hole mobility remain closer to the IBTE results, especially for the transverse contribution. At low-strain value, the MRTA presents very little variations that increase with the strain but stay below 1% for the transverse components and below 3% for the longitudinal ones. We note that this is specific to silicon but much larger differences between the SERTA, MRTA, and IBTE can be observed in other systems57,74,75. Piezoresistive coefficients π11 of -876 TPa−1 (resp. -841 TPa−1) and π12 of 475 TPa−1 (resp. 514 TPa−1) are obtained for the electrons while coefficients π11 of 139 TPa−1 (resp. 133 TPa−1) and π12 of -70 TPa−1 (resp. -79 TPa−1) are computed for holes under SERTA (resp. MRTA) at 300 K.

Our first-principles computations bring better confidence and reliability in the evolution of the mobilities in strained silicon and predict an important enhancement for the mobility of the holes at moderate strain. This contrasts with the limited variations observed experimentally at low strain. Our work highlights the potential to enhance the longitudinal component of holes and electrons by applying the same strain configuration, paving the way towards mobility-enhanced devices for both types of carriers. In addition, our computations allow for an in-depth study of the intrinsic values of the piezoresistances over a wide range of temperatures, bypassing the experimental constraints. The method presented here can be easily applied to other stress configurations or to other semiconductors to predict the variations of the phonon-limited mobilities due to the crystal deformation, leading to new discovery in the field of strain engineering.

Methods

Strained silicon structure

We used the ABINIT41,76 software with norm-conserving pseudopotentials from Pseudo Dojo77 in the generalized-gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)78 parametrization with a plane-wave cutoff of 20 Ha and a 18 × 18 × 18 k-point grid and we find a relaxed lattice parameter a0 of 0.547 nm, slightly overestimating the experimental value of 0.543 nm79.

The silicon crystal structure consists of two inter-penetrating face-centered cubic (FCC) lattices with two atoms in the primitive cell. In a crystal deformed along the [100] axis, the new set of lattice vectors (\({{\bf{a}}}^{{\prime} },{{\bf{b}}}^{{\prime} }\) and \({{\bf{c}}}^{{\prime} }\)) is given by

where I is the unit matrix, E100 is the tensor for uniaxial strain in the [100] crystal direction and (a b c) is the set of unstrained lattice vectors.

The deformation of the crystal with the applied stress can be expressed as62

where εαβ are the strain components from the E100 matrix, σαβ are the stress components, and sαβ are the stiffness components. In the particular configuration of stress applied in the [100] crystal direction, i.e., σαβ = 0 except for σxx, the strain components can be expressed as

As a consequence, the longitudinal strain component εxx is related to the transverse components εyy = εzz by

The strain tensor E100 for a uniaxial stress applied in the [100] direction can finally be written as

with εxx = s11 σxx.

Phonon-limited mobility

The mobility in Eq. (2) depends on the carrier density nc and electrical conductivity at low electric field \({\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }=(\partial {J}_{\alpha }/\partial {E}_{\beta }){| }_{{\bf{E = 0}}}\), defined as the ratio between the mean current density Jα in Cartesian direction α and the electric field Eβ in Cartesian’s direction β80. The carrier density nc for the electron or hole can be computed as42

where the band index n runs over the valence bands for the holes and over the conduction bands for the electrons, ΩBZ is the volume of the Brillouin zone, μ is the chemical potential, T is the temperature, εF is the Fermi energy, \({f}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{0}(\mu ,T)=1/\{\left.\right(\exp [({\varepsilon }_{n{\bf{k}}}-\mu )/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T]+1\}\) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution evaluated at the band energy εnk in the absence of electric field.

The conductivity can be expressed as

with Vcell the volume of the primitive cell, vnk,α = ℏ−1∂εnk/∂kα the component of the band velocity with crystalline moment k and band index n and \({\partial }_{{E}_{\beta }}{f}_{n{\bf{k}}}={(\partial {f}_{n{\bf{k}}}/\partial {E}_{\beta })\vert }_{{\bf{E}} = 0}\) where fnk is the electronic occupation distribution at the band energy εnk.

This last term can be computed recursively solving the IBTE51,81:

with the scattering rate

where \({n}_{{\bf{q}}\nu }=1/[\exp (\hslash {\omega }_{{\bf{q}}\nu }/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T)-1]\) is the Bose-Einstein distribution evaluated at the phonon energy ℏωqν and \(g\)mnν(k, q) is the e-ph matrix element for the scattering of an electron from state \({\psi}_{n{\mathbf{k}}}\) into state \({\psi}_{m{\mathbf{k}}+{\mathbf{q}}}\) with a phonon of mode ν and wavevector q. The matrix elements are given by82

where \({\psi}_{n{\mathbf{k}}}\) is the Kohn-Sham (KS) Bloch state and ΔqνVKS is the first-order variation of the self-consistent KS potential defined as75

where eκα,ν(q) is the α-th Cartesian component of the phonon eigenvector for the atom κ in the unit cell, Mκ its atomic mass, Rp are lattice vectors identifying the unit cell p, and τκα the ion position in the unit cell.

In practice, the scattering potentials were first computed from density-functional perturbation theory (DFPT) on a coarse 36 × 36 × 36 q-grid. Then, they were Fourier interpolated onto a fine 150 × 150 × 150 q-grid using dielectric tensors83 and quadrupoles40,84 for the long-range electrostatic contributions. Born effective charges are zero as strain along [100] direction does not break the symmetry of the silicon crystal. Changes of dielectric tensor and dynamical quadrupoles with strain are provided in SI44. The KS wavefunctions are obtained by performing a self-consistent (SCF) calculation on a coarse 18 × 18 × 18 k-grid before a non-self-consistent calculation (NSCF) on a fine 150 × 150 × 150 k-grid. To reduce the computation cost, the e-ph computation is only performed at the k-points with energies within a window of 200 meV above or below the band edges, i.e., close to the extrema of the valence and conduction bands. The spin-orbit coupling was taken into account to compute the electronic properties and neglected to retrieve the vibrational properties, dynamical quadrupoles and e-ph scattering potentials. A schematic representation of this framework is provided in Fig. S5 of the SI44.

Four-point bending measurements

A four-point bending setup is used to apply strain levels ranging from 0 to 1%, by steps of 0.02%, on an n-type silicon strain gauge supplied by Kyowa bonded on a polycarbonate substrate. The samples are obtained from a silicon beam oriented along the [100] crystal direction and encapsulated in two layers about 50 μm-thick of polyimide. Figure S8 of the SI44 shows the experimental setup and a microscope picture of the samples. The samples are 2mm-long with a cross-section of 250 μm by 20 μm. The resistivity has been estimated to 0.03 Ω cm, leading to a doping level to 5 × 1017 cm−3. An aluminum strain gauge from Micro-Measurements is placed next to the silicon to measure the strain applied by the bending equipment with a Keithley DMM7510 multimeter. The silicon resistance has been obtained from current-voltage measurements using an Agilent 4145 semiconductor analyzer in a voltage range from -0.5 V to 0.5 V with 20-mV steps.

The resistance variations computed from the current-voltage curves are shown in Fig. S9 of the SI44. The experimental results shown in Fig. 5 have been obtained with the devices oriented transversely and longitudinally to the strain direction. The zero-strain resistance of the two samples is 126 Ω and decreases (resp. increases) with a strain parallel (resp. perpendicular) to the current flowing in the device. Even though the mobility variations dominate, the dimensional variations have been subtracted from the resistance measurements to retrieve the resistivity changes by considering a Poisson’s ratio of 0.2885.

Data availability

The underlying code and generated datasets for this study are available on the Materials Cloud and can be accessed via this link https://doi.org/10.24435/materialscloud:sy-4g.

Change history

24 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01512-w

References

Foster, D. J. Silicon Processing: CMOS Technology, 173 (Springer US, 1991).

Jia, W. et al. Strain-tunable carrier mobility of Fe-doped GaN: A first-principles study. Micro Nanostruct. 168, 207300 (2022).

Fletcher, A. S. & Nirmal, D. A survey of Gallium Nitride HEMT for RF and high power applications. Superlattices Microstructures 109, 519 (2017).

Egard, M. et al. High-frequency performance of self-aligned gate-last surface channel In 0.53Ga 0.47as MOSFET. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 33, 369 (2012).

Rodrigues, I. H. & Vorobiev, A. Low-Field Mobility and High-Field Velocity of Charge Carriers in InGaAs/InP High-Electron-Mobility Transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 69, 1786 (2022).

Yeo, Y.-C., Gong, X., van Dal, M. J. H., Vellianitis, G. & Passlack, M. Germanium-based transistors for future high performance and low power logic applications. In 2015 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) (2015).

Du, C. et al. Tuning carrier lifetime in InGaN/GaN LEDs via strain compensation for high-speed visible light communication. Sci. Rep. 6, 37132 (2016).

Ochiai, T. et al. Ultrahigh-responsivity waveguide-coupled optical power monitor for Si photonic circuits operating at near-infrared wavelengths. Nat. Commun. 13, 7443 (2022).

Raghuveera, E., Rao, G. P. & Lenka, T. R. Prospects of III-V Semiconductor-Based High Electron Mobility Transistors (HEMTs) Towards Emerging Applications. In Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering. Vol. 1067, 123 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2024).

Sun, R., Lai, J., Chen, W. & Zhang, B. GaN power integration for high frequency and high efficiency power applications: a review. IEEE Access 8, 15529 (2020).

Thompson, S. E. et al. Future of strained Si/semiconductors in nanoscale MOSFETs. In 2006 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). (2006).

Kum, H. et al. Epitaxial growth and layer-transfer techniques for heterogeneous integration of materials for electronic and photonic devices. Nat. Electron. 2, 439 (2019).

Li, Y. S. & Nguyen, J. Tensilely strained Ge films on Si substrates created by physical vapor deposition of solid sources. Sci. Rep. 8, 16734 (2018).

Passi, V. et al. High-throughput on-chip large deformation of silicon nanoribbons and nanowires. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 21, 822 (2012).

Ureña, F. et al. Strain in silicon nanowire beams. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 114506 (2012).

Cavallo, F. & Lagally, M. G. Semiconductor nanomembranes: a platform for new properties via strain engineering. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 7, 628 (2012).

Sun, L. et al. 12-GHz thin-film transistors on transferrable silicon nanomembranes for high-performance flexible electronics. Small 6, 2553–2557 (2010).

Roisin, N., Brunin, G., Rignanese, G.-M., Flandre, D. & Raskin, J.-P. Indirect light absorption model for highly strained silicon infrared sensors. J. Appl. Phys. 130, 055105 (2021).

Roisin, N. et al. Band gap reduction in highly-strained silicon beams predicted by first-principles theory and validated using photoluminescence spectroscopy. Opt. Mater. 144, 114347 (2023).

Roisin, N., Colla, M.-S., Raskin, J.-P. & Flandre, D. Raman strain-shift measurements and prediction from first-principles in highly strained silicon. J Mater. Sci. Mater Electron. 34, 373 (2023).

Roisin, N., Delhaye, T., André, N., Raskin, J.-P. & Flandre, D. Low-power silicon strain sensor based on CMOS current reference topology. Sensors and Actuators A: Phys. 339, 113491 (2022).

Gnanachchelvi, P. et al. Performance enhancement in bipolar junction transistors using uniaxial stress on (100) silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron Dev. 63, 2643 (2016).

Li, S., Chou, J.-P., Zhang, H., Lu, Y. & Hu, A. A study of strain-induced indirect-direct bandgap transition for silicon nanowire applications. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 082520 (2018).

Fischetti, M. V. & Laux, S. E. Band structure, deformation potentials, and carrier mobility in strained Si, Ge, and SiGe alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 80, 2234 (1996).

Thompson, S. et al. A 90-nm logic technology featuring strained-silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 51, 1790 (2004).

Jaeger, R., Suhling, J., Ramani, R., Bradley, A. & Xu, J. CMOS stress sensors on [100] silicon. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 35, 85 (2000).

Kanda, Y. A graphical representation of the piezoresistance coefficients in silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 29, 64 (1982).

Dresselhaus, G., Kip, A. F. & Kittel, C. Plasma resonance in crystals: observations and theory. Phys. Rev. 100, 618 (1955).

Rideau, D. et al. Strained Si, Ge, and Si1−xGex alloys modeled with a first-principles-optimized full-zone k ⋅ p method. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195208 (2006).

Chelikowsky, J. R. & Cohen, M. L. Nonlocal pseudopotential calculations for the electronic structure of eleven diamond and zinc-blende semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 14, 556 (1976).

Slater, J. C. & Koster, G. F. Simplified LCAO method for the periodic potential problem. Phys. Rev. 94, 1498 (1954).

Niquet, Y. M., Rideau, D., Tavernier, C., Jaouen, H. & Blase, X. Onsite matrix elements of the tight-binding Hamiltonian of a strained crystal: Application to silicon, germanium, and their alloys. Phys. Rev. B 79, 245201 (2009).

Yin, M. T. & Cohen, M. L. Microscopic theory of the phase transformation and lattice dynamics of Si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1004 (1980).

Dhar, S., Ungersboeck, E., Kosina, H., Grasser, T. & Selberherr, S. Analytical Modeling of Electron Mobility in Strained Germanium. In 2006 International Conference on Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices. (IEEE, 2006).

Ungersboeck, E. et al. The effect of general strain on the band structure and electron mobility of silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 54, 2183 (2007).

Poncé, S., Margine, E. R., Verdi, C. & Giustino, F. EPW: Electron-phonon coupling, transport and superconducting properties using maximally localized Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 209, 116 (2016).

Lee, H. et al. Electron-phonon physics from first principles using the EPW code. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 156 (2023).

Zhou, J.-J. et al. Perturbo: A software package for ab initio electron-phonon interactions, charge transport and ultrafast dynamics. Computer Phys. Commun. 264, 107970 (2021).

Cepellotti, A., Coulter, J., Johansson, A., Fedorova, N. S. & Kozinsky, B. Phoebe: a high-performance framework for solving phonon and electron Boltzmann transport equations. J. Phys.: Mater. 5, 035003 (2022).

Brunin, G. et al. Phonon-limited electron mobility in Si, GaAs, and GaP with exact treatment of dynamical quadrupoles. Phys. Rev. B 102, 94308 (2020).

Gonze, X. et al. The ABINITproject: Impact, environment and recent developments. Comput. Phys. Commun. 248, 107042 (2020).

Poncé, S., Li, W., Reichardt, S. & Giustino, F. First-principles calculations of charge carrier mobility and conductivity in bulk semiconductors and two-dimensional materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 83, 036501 (2020).

Beaty, R., Jaeger, R., Suhling, J., Johnson, R. & Butler, R. Evaluation of piezoresistive coefficient variation in silicon stress sensors using a four-point bending test fixture. IEEE Trans. Compon., Hybrids, Manuf. Technol. 15, 904 (1992).

Roisin, N. et al. SI: Phonon-limited mobility for electrons and holes in highly-strained silicon. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 242 (2024).

Trimarchi, G. et al. Using design principles to systematically plan the synthesis of hole-conducting transparent oxides: Cu3VO4 and Ag 3VO4 as a case study. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 84, 165116 (2011).

Grosso, G. & Pastori Parravicini, G. Solid State Physics (Academic Press, New York, 2000), 1 edn.

Ramos, L. E. et al. Structural, electronic, and effective-mass properties of silicon and zinc-blende group-III nitride semiconductor compounds. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 63, 165210 (2001).

Yu, D., Zhang, Y. & Liu, F. First-principles study of electronic properties of biaxially strained silicon: Effects on charge carrier mobility. Phys. Rev. B 78, 245204 (2008).

Inaoka, T., Kinjyo, Y., Yanagisawa, S. & Tomori, K. Anisotropy of the silicon valence band induced by strain with various orientations. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 183718 (2013).

Janssen, J. L. et al. Precise effective masses from density functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205147 (2016).

Poncé, S., Margine, E. R. & Giustino, F. Towards predictive many-body calculations of phonon-limited carrier mobilities in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 97, 121201 (2018).

Ohyama, T. & Otsuka, E. Valence band cyclotron resonance of silicon under a uniaxial tensile stress. Phys. Lett. A 24, 586 (1967).

Yang, Q.-L., Li, W., Wang, Z., Ning, F.-l. & Luo, J.-W. Uncovering the important role of transverse acoustic phonons in the carrier-phonon scattering in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 109, 125203 (2024).

Thurber, W. R., Mattis, R. L., Liu, Y. M. & Filliben, J. J. Resistivity-dopant density relationship for boron-doped silicon. J. Electrochem. Soc. 127, 2291 (1980).

Tufte, O. N. & Stelzer, E. L. Piezoresistive properties of heavily doped n-type silicon. Phys. Rev. 133, A1705 (1964).

Leveillee, J., Zhang, X., Kioupakis, E. & Giustino, F. Ab initio calculation of carrier mobility in semiconductors including ionized-impurity scattering. Physical Review B 107, 125207 (2023).

Poncé, S. et al. First-principles predictions of Hall and drift mobilities in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043022 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Approaching the ideal elastic strain limit in silicon nanowires. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501382 (2016).

Bhaskar, U. et al. On-chip tensile testing of nanoscale silicon free-standing beams. J. Mater. Res. 27, 571 (2012).

Smith, C. S. Piezoresistance effect in germanium and silicon. Phys. Rev. 94, 42 (1954).

Voigt, W. Lehrbuch der kristallphysik (B.G. Teubner, 1910).

Madelung, O. Semiconductors: Group IV Elements and III–V Compounds (Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991). https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-45681-7.

Colman, D., Bate, R. T. & Mize, J. P. Mobility anisotropy and piezoresistance in silicon p-type inversion layers. J. Appl. Phys. 39, 1923 (1968).

Matsuda, K., Suzuki, K., Yamamura, K. & Kanda, Y. Nonlinear piezoresistance effects in silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 1838–1847 (1993).

Toriyama, T. & Sugiyama, S. Analysis of piezoresistance in p-type silicon for mechanical sensors. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 11, 598 (2002).

Lenkkeri, J. T. Nonlinear Effects in the Piezoresistivity of p-Type Silicon. Phys. status solidi (b) 136, 373 (1986).

Jaeger, R., Suhling, J. & Ramani, R. Errors associated with the design, calibration and application of piezoresistive stress sensors in (100) silicon. IEEE Trans. Compon., Packaging, Manuf. Technol.: Part B 17, 97 (1994).

Li, S. S. & Thurber, W. R. The dopant density and temperature dependence of electron mobility and resistivity in n-type silicon. Solid-State Electron. 20, 609 (1977).

Ma, J. L., Fu, Z. F., Wei, Q. & Zhang, H. M. Uniaxial stress induced electron mobility enhancement in silicon. Silicon 5, 219 (2013).

Kozlovskiy, S. & Boiko, I. First-order piezoresistance coefficients in silicon crystals. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 118, 33 (2005).

Morin, F. J., Geballe, T. H. & Herring, C. Temperature dependence of the piezoresistance of high-purity silicon and germanium. Phys. Rev. 105, 525 (1957).

Dhar, S., Kosina, H., Palankovski, V., Ungersbock, S. & Selberherr, S. Electron mobility model for strained-Si devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 52, 527 (2005).

Giustino, F. Electron-phonon interactions from first principles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 15003 (2017).

Claes, R., Brunin, G., Giantomassi, M., Rignanese, G.-M. & Hautier, G. Assessing the quality of relaxation-time approximations with fully automated computations of phonon-limited mobilities. Phys. Rev. B 106, 094302 (2022).

Poncé, S., Royo, M., Stengel, M., Marzari, N. & Gibertini, M. Long-range electrostatic contribution to electron-phonon couplings and mobilities of two-dimensional and bulk materials. Phys. Rev. B 107, 155424 (2023).

Gonze, X. et al. Recent developments in the ABINIT software package. Computer Phys. Commun. 205, 106 (2016).

Van Setten, M. et al. The pseudodojo: Training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Computer Phys. Commun. 226, 39 (2018).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Okada, Y. & Tokumaru, Y. Precise determination of lattice parameter and thermal expansion coefficient of silicon between 300 and 1500 K. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 314 (1984).

Sze, S. & Ng, K. K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices (Wiley, 2006).

Ziman, J. Electrons and Phonons (Oxford University Press, 1960).

Giustino, F., Cohen, M. L. & Louie, S. G. Electron-phonon interaction using Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165108 (2007).

Gonze, X. & Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10355 (1997).

Royo, M. & Stengel, M. First-principles theory of spatial dispersion: dynamical quadrupoles and flexoelectricity. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021050 (2019).

Hopcroft, M. A., Nix, W. D. & Kenny, T. W. What is the Young’s Modulus of Silicon? J. Microelectromech. Syst. 19, 229 (2010).

Cho, C. H., Jaeger, R. C. & Suhling, J. C. Characterization of the temperature dependence of the piezoresistive coefficients of silicon from -150 °C to +125 °C. IEEE Sens. J. 8, 1455 (2008).

Dorey, A. & Maddern, T. The effect of strain on MOS transistors. Solid-State Electron. 12, 185 (1969).

Blöchl, P. E., Jepsen, O. & Andersen, O. K. Improved tetrahedron method for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 49, 16223 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We thank Matteo Giantomassi for discussion and suggestion about the computation of the phonon-limited mobility taking into account the spin-orbit coupling using ABINIT software. S.P. and G.-M.R. acknowledge support from the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique de Belgique (FRS-FNRS). Computational resources have been provided by the supercomputing facilities of the Université catholique de Louvain (CISM/UCL) and the Consortium des Équipements de Calcul Intensif en Fédération Wallonie Bruxelles (CÉCI) funded by the Fond de la Recherche Scientifique de Belgique (F.R.S.-FNRS) under convention 2.5020.11 and by the Walloon Region. The present research benefited from computational resources made available on Lucia, the Tier-1 supercomputer of the Walloon Region, infrastructure funded by the Walloon Region under the grant agreement n∘1910247.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.R. adapted the initial code to generate the inputs, generated the data, performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. G.B. developed the initial code to generate the inputs, performed the analysis and reviewed the manuscript. G.-M.R., D.F., J.-P.R. supervised the work and reviewed the manuscript. S.P. performed the analysis, supervised the work and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roisin, N., Brunin, G., Rignanese, GM. et al. Phonon-limited mobility for electrons and holes in highly-strained silicon. npj Comput Mater 10, 242 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01425-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01425-0

This article is cited by

-

Nanosheet transistors: materials, devices, systems and applications

Journal of Materials Science (2025)

-

Phonon-limited mobility for electrons and holes in highly-strained silicon

npj Computational Materials (2024)