Abstract

We present a multi-objective Bayesian active learning strategy, which greatly accelerates the discovery of super high-strength and high-ductility lead-free solder alloys. The active learning strategy demonstrates that a machine learning model will have high generalizability if experimental data uncertainty is included, which greatly improves the model prediction or the material design accuracy. The feature-point-start forward method in multi-objective optimization adopts two Gaussian process regression (GPR) models, one for strength and one for elongation, and their outputs build up the acquisition-function-modified objective space of strength and elongation. Then, Bayesian sampling is applied to design the next experiments by balancing exploitation and exploration. Seven multi-objective active learning iterations discovered two novel super high-strength and high-ductility lead-free solder alloys. After that, various material characterizations were conducted on the two novel solder alloys, and the results exhibited their high performances in melting properties, wettability, electrical conductivity, and shear strength of the solder joint and explored the mechanism of high strength and high ductility of the alloys. The present work systematically analyzes the important role of experimental uncertainty in machine learning, especially in the global optimization for material design, which demands high generalizability of predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, Sn-Pb solder alloys have been used for a long time because of their good wettability, excellent melting properties, and mechanical properties1. Since lead is a toxic metal, that pollutes the environment and endangers human health, lead-free solders have replaced Sn-Pb solders2. The binary and ternary lead-free solder has been systematically and extensively studied3, such as Sn-Ag4, Sn-Cu5, Sn-Zn6, Sn-Bi7, Sn-In8, Sn-Ag-Cu9, and Sn-Cu-Ni10. Among them, Sn-Ag-Cu (SAC) based alloys, near eutectic composition with low melting point and excellent solderability, are widely used as lead-free solders11,12. The fast-increasing microelectronic and electronic products, such as flexible soft electronics, biomedical devices, solar cells, etc. demand for advanced solder alloys, while how to further enhance the performance lead-free solders is a great scientific and technologic challenge.

Outstanding lead-free solders have a prerequisite that raw solders should have high strength and high ductility, although many properties are characterized when solders are bonded with substrates. The improvement in strength is usually accompanied by ductility loss and vice versa, which is a long-standing dilemma referred to as the strength-ductility trade-off. It is a great challenge to and the goal of materials scientists and engineers to enhance strength and ductility simultaneously. In materials science and engineering, the optimal multiple properties of materials can be achieved by two basic approaches, changing the chemical composition and varying the microstructures via various material processes. Since solders are re-melt during soldering, the present work takes the alloying approach to discover novel lead-free solders with both high strength and high ductility. When the Sn-Ag-Cu lead-free solder alloys are taken as the base materials, many alloying elements, such as Ni, Bi, Co, Ti, Al, Pt, Pd, Zr, Ag13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, and rare-earth elements21,22,23,24, have been added into the base alloys to refine the primary β-Sn grains21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 and the size, morphology and distribution of intermetallic compounds (IMCs) formed in the alloyed solders to enhance both strength and ductility. The size, morphology, and distribution of IMCs and the microstructure of the matrix play extreme roles in the properties of lead-free solders, which are, in turn, dependent on the alloying elements28,29,30,31,32,33. The traditional approach in the research and development of lead-free solders is the trial-and-error method, which is costly and time-consuming.

Along with the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), the data-driven materials informatics paradigm has rapidly become popular in materials science and engineering, by integrating AI with experiments, theory, computation, and simulations34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. The data-driven paradigm, combined with expert domain knowledge, provides state-of-the-art methodologies for understanding and predicting complex material behaviors, achieving significant accomplishments in materials informatics. Over the past 2–3 years, the data-driven materials informatics paradigm has made remarkable achievements in predicting the mechanical properties of lead-free solder alloys and in discovering a series of novel lead-free solders48,49,50. For example, Yuan et al.48 established an ML model for SAC-based lead-free solder alloys, with the alloy chemical composition or the atomic parameters as input features, and the tensile strength and fracture elongation as the target properties. They proposed a novel indicator for comprehensive mechanical performance, i.e., the L2 norm of strength and ductility, and discovered two outstanding lead-free solder alloys. Wei et al.49 studied the effects of alloying on the mechanical properties of lead-free solders \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{bal}}.}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{1}}{{\rm{Zn}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}{{\rm{Sb}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{3}}{{\rm{In}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{4}}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{5}}{{\rm{Ni}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{6}}{{\rm{Al}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{7}}\). To address the challenge of limited and noisy experimental data against a vast design space, they developed the strategy of “divide and conquer” and proposed a novel data preprocessing algorithm, Tree-classifier for Gaussian process regression (TCGPR). The TCGPR effectively divided an original dataset in a huge design space into three appropriate sub-domains, and then three ML models conquered the three sub-domains, achieving significantly improved prediction accuracy and generality. They successfully discovered a series of lead-free solder alloys with both high strength and high ductility by employing the “divide and conquer” strategy. Cao et al.50 employed a Bayesian active learning strategy to address the strength-ductility trade-off in \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{bal}}.}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{1.0}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.5}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{1}}{{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{3}}\) lead-free solders. After just three iterations, a new \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{bal}}.}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{1.0}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.5}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{1.5}{{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}}_{4.4}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{0.2}\) low-silver SAC solder was discovered, exhibiting 73.94\(\pm\)5.05 MPa ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and 24.37\(\pm\)5.92% fracture elongation. Fig. 1 summarizes the reported experimental results of strength and ductility of lead-free solders collected from the literature, including a series of novel solder alloys discovered in the present work. It should be mentioned again that excellent lead-free solders require balanced multiple properties, rather than just mechanical properties. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 1, the commercial lead-free solder Sn90.88Ag3.8Cu0.7Ni0.15Sb1.5Bi3.0 exhibits an excellent combination in strength and ductility51,52,53, the previously reported lead-fee solders have high ductility, while their strengths are all lower than the commercial one. It is the present discovered two alloys exhibit simultaneously excellent strength and ductility, both higher than the commercial one.

These ML models48,49,50 have achieved great success in the accelerated discovery of novel lead-free solder alloys, even without considering experimental data uncertainty, which is caused by unknown factors and called error bars in experiments and noise in AI and ML. In materials informatics, there are generally two main types of uncertainties for target Y: experimental uncertainty54 and predicted uncertainty55. From the probabilistic point of view, each test in the experiment can be regarded as a sampling from the target Y distribution, thereby yielding the experimental uncertainty in repeated tests under identical experimental conditions on the same materials, which magnitude obviously depends on the nature of the problem studied, tested material, and experimental techniques including equipment and methods. The values measured in repeated tests follow a normal distribution and the mean and standard deviation (variance) can be calculated from the repeated test results54,55. Although the reasons for the uncertainty are explored in order to control and minimize the unknown factors by certain measures, experimental uncertainty always exists, and reliable mean and variance demand sufficient repeated tests. Bayesian active learning is widely used in materials informatics to accelerate the discovery of novel materials, while the reported works only focus on the prediction uncertainty (noise) without considering experimental data uncertainty56,57,58,59,60. Experimental data uncertainty is the observed uncertainty and truly represents the uncertainty caused by the random nature of materials microstructure distribution and the limited accuracy and repeatability error of a used experiment set-up. Therefore, experimental data uncertainty plays an extremely important role in materials science and engineering, especially in dealing with small data34, while one of the merits of Bayesian active learning with GPR is the power of learning small data. Considering experimental data uncertainty demands many repeated testing results to produce reliable experimental uncertainty. The present work emphasizes the integration of irreducible experimental uncertainty into Bayesian active learning and demonstrates that considering both experimental data uncertainty and prediction uncertainty greatly enhances the ML prediction generalizability. In Bayesian global optimization, acquisition functions take both ML predicted mean and variance (uncertainty) to balance exploration-exploitation61,62 and recommend candidates for the next experiment.

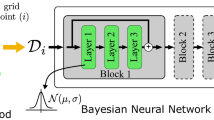

The present work proposes a multi-objective Bayesian active learning strategy, considering experimental data uncertainty, to discover novel super-strength and high-ductility lead-free solder alloys. The Snbal.-Ag3.8-Cu0.7 (SAC387) solder alloy exhibits outstanding comprehensive properties63 and our preliminary work49 reveals the great potential of alloying Bi, In, and Ti into SAC387 solder alloy. Therefore, this study focuses on the lead-free \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{bal}}.}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{1}}{{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{3}}\) system and adopts active learning to discover novel lead-free alloys. Fig. 2 illustrates the framework of active learning. The dynamic experimental dataset includes the mean and variance of UTS and fracture elongation, which are obtained from repeated tests. In each iteration of active learning, experimental data are used to train two GPR models, one for strength and one for fracture elongation, and the trained models predict UTS and fracture elongation, in terms of mean and variance, for all points in the search space. Three acquisition functions—expected improvement (EI), probability of Improvement (POI), and upper confidence bound (UCB)—are utilized to implement the global optimization with the predicted mean and variance of UTS and elongation. Each of the acquisition functions delivers a 2D acquisition-function-modified objective space on the search space and the virtual samples on the Pareto front are filtered with other constraints and hence recommended for the next experiment. After seven such active learning iterations, the present work discovers two novel super high-strength and high-ductility SAC387-based solder alloys, as shown in Fig. 1. After that, other characterizations on the two newly discovered alloys prove that they possess also low melting points, good wettability, high electrical conductivity, and high shear strength when bonded on Cu substrate.

Framework of the proposed multi-objective Bayesian active learning with included experimental data uncertainty, for designing super high-strength and high-ductility lead-free solder alloys. a Dataset with experimental uncertainty. b Two developed Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) models, one for strength and one for elongation. c Multi-objective Bayesian sampling based on the acquisition-function-modified objective space. d Iteration results with experimental feedback. e Experimental characterization and mechanism exploration.

Methods

Initial training dataset, selection of repeated testing data, and search space

The initial training data of SAC387-based alloys, \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{bal}}.}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{1}}{{\rm{In}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{3}}\), were generated from in-house experiments, which compositions in wt.% include fixed Ag content of 3.8 wt.% and Cu concentration of 0.7 wt.%, three adjustable alloying elements \({{\rm{Bi}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{1}}\), \({{\rm{In}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}\) and \({{\rm{In}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}\), and balanced by Sn. The initial training dataset contains 18 different alloys, selected by orthogonal design, as listed in Table 1. Eight repeated tests were conducted for each alloy, except that only six repeated tests were conducted for alloy P3, which resulted in eight uniaxial tensile stress-strain curves for each alloy, except for alloy P3. The UTS (MPa) and fracture elongation (%) were extracted from each curve. All repeated testing data for UTS and elongation in the initial dataset are listed in Supplementary Table 1. For instance, Fig. 3a shows the stress-strain curves, UTS and elongation values, and optical images of the eight tested samples of alloy P1. From the repeated experimental data, the initial mean and initial standard deviation are calculated for both UTS and elongation. As an example, Fig. 3b, c plot the distributions of UTS and elongation, respectively, for alloy P1. Each of the repeated tests can be regarded as a random sampling thus we have Gaussian distribution \(y={\mathscr{N}}\left(\mu ,\sigma \right)\) with mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\). For alloy P1, the elongation has the initial mean (29.38%) and initial standard deviation (3.86%), while the UST has the initial mean (47.23 MPa) and initial standard deviation (1.26 MPa). The coefficient of variation (CV), CV = Standard deviation/mean, is statistically and widely used to compare the scattering magnitude between two distributions, which is employed here to select more reliable data. For alloy P1, the elongation CV is 0.13, which is higher than the 0.03 value for UTS. Based on the CV result, we propose a preprocessing method based on the elongation data to select more reliable experimental data. The preprocessing method, named the “Elongation-Based One-Sigma Repeated Testing Data Selection”, employs the one standard deviation \(\sigma\) criterion, meaning that samples with elongation value smaller or larger than one standard deviation \(\sigma\) from the original mean value will be moved out. As shown in Fig. 3c, samples 2, 5, and 7 are removed for alloy P1. After that, the input mean and variance are re-calculated on the selected data. The selected five repeated testing samples of alloy P1 give the results of 47.07 ± 1.49 MPa and 30.31 ± 1.49% for the alloy P1 UTS and elongation, respectively. The “Elongation-Based One-Sigma Repeated Testing Data Selection” method is used hereafter for the analysis of all experimental data, and Table 1 lists the alloy composition, UTS\(\left(\mu \pm \sigma \right)\), elongation \(\left(\mu \pm \sigma \right)\), and number of repeated tests for each alloy in the initial training dataset. For detailed information, the Supplementary Table 1 lists all initial repeated testing data of UTS and elongation.

a Eight repeated stress-strain curves, UTS and elongation values, and optical images. Distributions of b UTS and c elongation of the eight repeated tests, where the initial mean \(\mu\), initial standard deviation \(\sigma\), and the coefficient of variation \(\left(\mu /\sigma \right)\) are also indicated in the figure. Based on the proposed “Elongation-Based One-Sigma Repeated Testing Data Selection”, samples 2, 5, and 7 are removed, and hence the input data of UTS and elongation are from samples 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7.

GPR model with embedded experimental uncertainty

Repeated tests for a given alloy \(X\) under the same testing conditions yield the mean and standard deviation of a measured property, which is expressed by (\(X\), \(y\pm \sigma\)), where y and \(\sigma\) are the mean and standard deviation or variance if the number of repeated tests is sufficiently large. The variance \(\sigma\) of the property represents the experimentally observed uncertainty (heterogeneous noise), and the observation uncertainty for \(n\) alloys can be expressed by an \(n\times n\) diagonal matrix \({\varSigma }_{n}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}{\sigma }_{1}^{2} & \cdots & 0\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & \cdots & {\sigma }_{n}^{2}\end{array}\right]\).

A brief introduction of GPR algorithm is given in the Supplementary Information, and the detailed description can be found in the monograph64 and refs. 65,66. The GPR model embedding experimental uncertainty and homogeneous noises is given by

where \(y\left(X\right)\) and \({y}_{* }\left({X}_{* }\right)\) denote the training and predictive data, respectively, \(K\) and\(\,{K}_{* * }\) are the kernel functions of \(X\) and \({X}_{* }\), respectively, called the covariance matrixes for data \(X\) and \({X}_{* }\) as well, \({K}_{* }\) is the kernel function or covariance matrix between data \(X\) and \({X}_{* }\), \({\rm{I}}\) is the \(n\times n\) unity matrix, and \({\tau }^{2}\) is the homogeneous noise, which behaves the hyperparameter in \({L}_{2}\) regularization and its optimal value is obtained by cross-validation.

The Gaussian squared-exponential covariance kernel, also known as the radial basis function (RBF) kernel, is used in the present GPR, which is defined by

where \({\sigma }_{f}^{2}\) and \(l\) are called the signal variance and the width of RBF, respectively. Two GPR models with the RBF kernel, but different optimal \({\sigma }_{f}^{2}\) and \(l\), are developed to predict the means and variances of UTS and elongation, respectively. In this study, both the heterogeneous and the homogeneous noises are embedded in the GPR model. The width parameter (\(l\)) is optimized within the range (1, 100) for UTS and (0.1, 10) for elongation, while no constraint is applied to the signal variance (\({\sigma }_{f}^{2}\)). For comparison, the three kernels of RBF, Dot-Product, \(K\left(X,{X}^{{\prime} }\right)={\sigma }_{0}^{2}+X\cdot {X}^{{\prime} }\), and Exp-Sine-Squared, \(K\left(X,{X}^{{\prime} }\right)=\exp \left(-\frac{\left(2\sin \frac{{{||}X,{{X}}^{{\prime} }{||}}^{2}}{p}\right)}{{l}^{2}}\right)\) are employed in the GPR models trained on the 18 initial training data, where \({\sigma }_{0}\) is allowed to vary within (0.01, 1000) for UTS and (0.01, 100) for elongation, and parameters \(p\) and \(l\) varying within (0.00001, 100,000) for both UTS and elongation. The performances of the three kernel functions are evaluated by the LOOCV and shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, indicating that the RBF kernel performs better than the Dot-Product and Exp-Sine-Squared kernels.

Bayesian sampling

The Bayesian sampling in the present work adopts three acquisition functions: EI with “plugin” (EI)67, POI68, and UCB69, to balance exploration and exploitation for each objective. For a given single objective \(y\), the acquisition functions EI, POI, and UCB are defined respectively by

where \({\mu }_{i}\) and \({\sigma }_{i}\) are the predicted mean and variance of the given single objective \(y\) at the point \(i\) in the search space, respectively; \(\varphi (\cdot )\) and \(\phi \left(\cdot \right)\) are the distribution density and cumulative function, respectively; \(T\) is the pre-set target value for the given single objective \(y\); \({\rm{\alpha }}\) is a pre-set weight to linearly combine the terms of mean and variance in UCB. In this study, the weight \({\rm{\alpha }}\) is fixed at 0.5 throughout all iterations of active learning; the pre-set target value \(T\) is dynamically adjusted in each iteration, following the strength-ductility enhancement direction. Supplementary Table 4 lists the \(T\) values used in EI and POI, for each objective in each iteration of active learning. Each acquisition function recommends two alloys on the Pareto Front for the next experiment.

The feature-point-start forward method in multi-objective optimization

Consider multi-objectives \({y}^{(k)}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}\right)\left(k=1,\cdots ,K\right)\), \({\boldsymbol{y}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{K}\), where \({\boldsymbol{y}}\) is an objective point in the objective space and \({\boldsymbol{x}}\) is a feature point in the m-dimensional feature space, i.e., \({\boldsymbol{x}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m}\). When conducting experiments and computations on a given material specimen, its feature point \({\boldsymbol{x}}\) is fixed, and its multi-objectives are all functions of \({\boldsymbol{x}}\). Similarly, the prediction of every component \({\hat{y}}^{(k)}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}\right)\) in AI and ML must be based on the same feature point so that we can have \({\boldsymbol{y}}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}\right)\). The feature-point-start forward method ensures \({\boldsymbol{y}}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}\right)\) in multi-objective optimization. In this method, the forward process in each of the multi-models starts from one common feature point, and hence each model predicts one component of an objective point70,71,72,73,74, and the multi-models predict only one objective point corresponding to the starting feature point. Then, the predicted points form the objective space, where Pareto front appears. All objective points on the Pareto front are currently optimal and the Bayesian active learning aims at the further pushing Pareto front forward in order to discover novel materials. Based on the design goal, one has to balance among multi-objectives to select the right point on Pareto front. The present study aims at the discovery of high-strength and high-ductility lead-free solder alloys.

As described above, experimental data uncertainty plays an extremely important role in materials science and engineering, especially in dealing with small data. When considering prediction uncertainty, the objective space is slightly modified by an adopted acquisition function. The three acquisition functions of EI, POI and UCB are used in the present work with the mean and variance of UTS (or elongation) predicted by the GPR model. Thus, the acquisition-function-modified objective space illustrates the Pareto front more clearly. Fig. 4 is a schematic plot of the feature-point-start forward method in the dual-objective optimization.

In summary, a feature space is first constructed with about 9,000 alloys of the \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{{\rm{bal}}.}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{1}}{{\rm{In}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{2}}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}_{3}}\) system, where 0 wt.%≤\({{\rm{x}}}_{1}\) ≤ 6 wt.%, 0 wt.%≤\({{\rm{x}}}_{2}\) ≤ 6 wt.%, and 0 wt.%≤\({{\rm{x}}}_{3}\) ≤ 1 wt.% and variation step sizes are 0.2 wt.%, 0.2 wt.%, and 0.1 wt.% for the concentrations \({{\rm{x}}}_{1}\), \({{\rm{x}}}_{2}\) and \({{\rm{x}}}_{3}\), respectively. Then, the workflow described below shows the steps at each iteration in the Bayesian optimization active learning used in the present work.

-

(1)

Train two GPR models, one for UTS and one for elongation;

-

(2)

Map the 3D feature-space to the 2D acquisition-function-modified objective space by using the feature-point-start forward method, the two trained GPR models, and the three acquisition functions of EI, POI, and UCB;

-

(3)

Select the right points on the Pareto Front in the 2D acquisition-function-modified objective space;

-

(4)

Map back the selected points on the Pareto Front back to the feature space;

-

(5)

Carry out repeated experiments on the recommended alloys and do the data preprocessing;

-

(6)

Add the experimental data of means and standard deviation into the dataset.

Experiment and evaluation parameters

The raw materials are Sn, Ag, Cu, Bi, In, and Ti, with a purity of 99.99%. The raw alloy mixtures were melted in an induction furnace, and the molten solder alloys were cast into a cuboid steel mold. With the cast, the tested samples were prepared with a dog bone shape with a size of 12 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm. Tensile tests at room temperature were conducted using a universal material testing system at a constant strain rate of \({1.67\times 10}^{-3}{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\). Eight repeated tensile tests were conducted for each alloy, which gave the means and standard deviations of UTS (MPa) and fracture elongation (%). Microstructure examination was performed using an optical microscope (DYJ-980BD) and a scanning electron microscope (SEM; HITACHI FlexSEM 1000 II) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Bruker Esprit Compact). The crystalline phase analysis was performed using an X-ray Diffractometer (Bruker D2 Phaser) using Cu-Kα radiation with an accelerating voltage of 40 kV. The scanning step was set to 0.02° across the angle (2θ) range of 20°–100°. The melting property of the alloys was examined using differential thermal analysis (DTA), and the DTA curve was measured by a simultaneous thermal analyzer. The DTA test was conducted by heating an 80 mg alloy sample to a temperature of 260 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and then cooling it down to 100 °C at a cooling rate of 10 °C/min in an argon atmosphere. The electrical resistivity of the prepared solder alloys was measured using an Eddy Current Conductivity Meter (FD102). For the wettability test, 200 mg of solder alloy was placed on a polished Cu substrate with resin flux, heated to 230 °C, kept for 10 min in a reflow oven with a nitrogen atmosphere, and then cooled down to room temperature. The contact angle of the melted solder was measured using an angle tester (OCA25HTV). In the shear strength test, the solder was made into a sphere with a diameter of 630 µm. The solder sphere was placed on the PCB pad substrate with resin flux, heated to 230 °C, kept for 10 min in a reflow oven with a nitrogen atmosphere, and then cooled down to room temperature. The reflowed solder was used to conduct the shear strength test, using a shear force test system (Sigma), to obtain the shear force of the solder joint. The shear test was performed at room temperature with a shear speed of 500 μm/s and a shear height of 60 μm, and the maximum shear force during the loading process was recorded to calculate the shear strength. Twenty repeated shear strength tests were conducted for each solder alloy, and their mean and standard deviation are reported here.

In this study, various parameters are utilized to evaluate the goodness of fitting, including the Coefficient of Determination (R2)

the mean absolute error (MAE)

and the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE)

where \(n\) is the number of data, \({y}_{i}\) is the true value, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) is the prediction and \(\bar{{\rm{y}}}\) is the mean of \({y}_{i}\).

The Coefficient of Determination, \({R}^{2}=1-\frac{\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{n}{({y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{i})}^{2}}{\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{n}{({y}_{i}-\bar{{\rm{y}}})}^{2}}\), is a commonly used metric for evaluating the goodness of fit in regression models. It takes the mean \(\bar{{\rm{y}}}\) as the reference to evaluate the prediction \({\hat{y}}_{i}\). When all \({\hat{y}}_{i}=\bar{{\rm{y}}}\), \({R}^{2}=0\). The R2 is sensitive to large \({({y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{i})}^{2}\). \({\rm{MAE}}=\frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{n}\left|{y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{i}\right|\) measures the average of the absolute errors, but has a physical dimension as that of the objective and therefore, cannot be used to compare regression goodness of different objectives with different physical dimensions. \({\rm{MAPE}}=\frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{n}\left|\frac{{y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{i}}{{y}_{i}}\right|\times 100\) expresses accuracy as a percentage, making it easier to understand the size of the error relative to the actual values. Employing multiple evaluation metrics of R2, MAE, and MAPE provides a comprehensive evaluation of the GPR models from different perspectives.

Results

GPR models with and without experimental uncertainty

We investigated the influence of experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises) on GPR models for UTS and elongation by conducting leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) performance analysis, under three different circumstances: without considering experimental uncertainty (noise-free), considering experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises), and considering both the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises) and the optimized homogeneous noise. The comprehensive comparison results on 18 initial training data (1th iteration) are shown in Fig. 5a–f.

a, b Without considering uncertainty (noise-free), c, d considering the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises), and e, f considering both the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises) and the optimized homogeneous noise. The insets of e, f plot the LOOCV-R2 value against the homogeneous noise value τ.

Fig. 5a, b show the coefficient of determination (R2) and MAE between the experimental and predicted values of the 18 initial training data, by the GPR models without considering uncertainty (noise-free GPR models), where the LOOCV-R2 values are 0.917 and 0.818 for UTS and elongation, respectively. Fig. 5c, d show that after adding experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises) into the GPR models, the prediction accuracy LOOCV-R2 improved significantly, from 0.917 to 0.938 for UTS and from 0.818 to 0.856 for elongation. This result clearly illustrates that considering experimental uncertainty enhances the generalization capacity of the GPR models. Furthermore, Fig. 5e, f show LOOCV results of GPR models for UTS and elongation, considering both experimental uncertainties (heterogeneous noises) and optimized homogeneous noise, where the prediction accuracy LOOCV-R2 is further improved compared to only considering the experimental uncertainty; specifically, from 0.938 to 0.957 for UTS and from 0.856 to 0.870 for elongation. The insets of Fig. 5e, f show the LOOCV-R2 value versus the homogeneous noise value τ, where the maximal LOOCV-R2 value determines the optimal τ value for UTS and elongation GPR models as 2.2 and 0.8, respectively.

In the above three circumstances, the GPR models for UTS and elongation exhibited the lowest LOOCV prediction accuracy when not considering the uncertainty. This might be due to the fact that the small dataset in this study easily causes overfitting, resulting in low prediction accuracy. The experimentally observed uncertainty depends on the nature of the studied material and experimental techniques, including equipment and methods. Usually, the experimentally observed uncertainty level (variance) of the property for different composition solders varies (heterogeneous). In GPR models, this heterogeneous experimental uncertainty acts as a heterogeneous constraint for the data, i.e., different training data points in GPR are constrained by corresponding different experimental uncertainty values. This heterogeneous constraint can reduce overfitting and improve generality. The experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noise) is fixed in the GPR model, while the homogeneous noise τ is treated as an optimizable parameter; its value is optimized during training to optimize the GPR regressor.

Overall, we demonstrate that the use of experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noise) and the optimized homogeneous noise in GPR is advantageous for making better LOOCV predictions and improving generality, compared to that without using them. Therefore, the GPR models considering both the heterogeneous and homogeneous noises are used to make predictions.

Bayesian sampling

The objective surface of the GPR prediction over the whole search space is built up by the prediction means with variances, as shown in Fig. 6a. The high prediction variances make it hard to determine the Pareto front and to recommend candidates for the next experiment accordingly. The Bayesian global optimization uses acquisition functions to balance exploration and exploitation. The pre-set target value \(T\), as listed in Supplementary Table 4, is UTS = 75 MPa and elongation = 10% in the first iteration. Then, each of the three acquisition functions yields one acquisition-function-modified objective space, as shown in Fig. 6b–d for the EI, POI, and UCB, respectively. Each of the three acquisition-function-modified objective spaces shows a clear Pareto front, with 17, 26, and 29 virtual samples located on these fronts for EI, POI, and UCB, respectively. Each acquisition function recommends two samples from its respective Pareto front that satisfy the pre-set target value T, and the recommended points are represented by stars in Fig. 6b–d. Three acquisition functions recommend six alloys, among which two alloys are recommended by multiple acquisition functions in the first iteration, and hence only four alloys are recommended for experiment in the first iteration. Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 list the UTS and elongation for all recommended alloys and all experimentally measured data from repeated tests.

a Predicted means and associated variances of UTS and elongation at each point in the search space, where the red circles represent the means and the associated error bars denote the variances. b EI, c POI, and d UCB acquisition function values of UTS and elongation for all points in the search space, exhibiting clear Pareto Front in red points, where the recommended points are represented by stars.

Iteration results with experimental feedback

Seven iterations of active learning are conducted with the three acquisition functions. Although each acquisition function is allowed to recommend 2 alloy candidates in each iteration, the three acquisition functions can sometimes recommend the same alloy. Thus, a total of 30 new alloys across the seven iterations are recommended, as listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

To further emphasize the significant role of experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noise) and optimized homogeneous noise in the GPR model, we plot the LOOCV-R2 values across the 7 iterations in Fig. 7a, b with and without the uncertainty, illustrating the prediction improvement by considering the experimental uncertainty. Fig. 7a, b show that across 14 different datasets, seven iterations with two tensile properties of UTS and elongation, adding the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noise) into the GPR models resulted in significant improvements in prediction accuracy of LOOCV-R2 on 13 datasets (compared to noise-free model) except of one UTS dataset at the second iteration. Fig. 7c–h indicate the comparison in the 7th iteration, and Supplementary Figs. 2–6 in the Supplementary Information show the comprehensive comparison results of LOOCV prediction, at the 2–6 iterations of multi-objective active learning, respectively. All results further demonstrate the enhancement with experimental uncertainty on GPR model performance.

a, b Comparison of LOOCV-R2 values across the seven iterations. Clearly, adding the experimental uncertainty into the GPR models can greatly improve the prediction accuracy or the material design accuracy, compared to the noise-free model (without considering uncertainty). c–h Comparison of LOOCV prediction by GPR models at the 7th iteration: c, d without considering uncertainty (noise-free), e, f considering the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises), and g, h considering both the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noises) and the optimized homogeneous noise. The insets of g, h plot the LOOCV-R2 value against the homogeneous noise value τ.

The goal of the multi-objective Bayesian active learning is to accelerate the discovery of high strength and high ductility of lead-free solder alloys. Fig. 8a shows the predictive values and the experimental values for the UTS in the seven iterations, illustrating obviously that almost all the predictive values are lower than the experimental values. Especially in the fourth iteration, the predicted UTS means range from 88.88 MPa to 103.52 MPa, much higher than the corresponding experimental means, ranging from 75.96 MPa to 79.55 MPa. There are two possible reasons for the large deviation between the predicted and experimental UTS. One reason is that the indium (In) content in the recommended alloys at the fourth iteration reached 4.8 wt.% to 5.8 wt.%, far exceeding the maximum In content of 4.4 wt.% in the alloys of the training dataset for the fourth iteration. The other reason might lie in the preprocessing of the repeated testing data. At the moment, the data preprocessing is purely on the elongation values, because their standard deviations are generally much higher than the corresponding ones of UTS data. Thus, this preprocessing method of the repeated testing data leads to the experimental noise level in the UTS data being larger than that in the elongation data and, subsequently, less accurate UTS predictions by the ML models. The two aspects will be considered and improved in the near future work. For the elongation predictions in the seven iterations, as expected, some predictive values are larger than the experimental data, and some are smaller, as shown in Fig. 8b.

The experimental measured and GPR predicted values of a ultimate tensile strength (UST) and b fracture elongation, where the error bar denotes the variance. c, d Comparison of prediction errors (Mean Absolute Percentage Error, MAPE) on the recommended alloys for the GPR models at each iteration, where the blue columns represent GPR models without considering uncertainty (noise-free), and the black columns represent GPR models considering both the experimental uncertainty (heterogeneous noise) and the optimized homogeneous noise. e All experimental data and the reported alloys shown in Fig. 1, in the strength-ductility plane. f The representative stress-strain curves for alloy Si-4, alloy Se-5, and commercial alloy.

For quantitative analysis, Fig. 8c, d show the MAPE of the GPR predictions on the recommended alloys at each iteration, indicating that the GPR models considering experimental uncertainty and homogeneous noise generally have much smaller prediction errors on the recommended alloys (i.e., much higher generalizability), compared to the GPR models that do not use them. These comparison results strongly support the general principle that incorporating reliable experimental uncertainty can enhance the accuracy and generalizability of ML models, showing the important role of experimental uncertainty in Materials Informatics.

Fig. 8e shows the objective surface for all experimental data, including the iteration number. The first iteration enhances the strength and reduces the ductility, showing the strength-ductility dilemma. In the following iterations, the Pareto front gradually moves up-forwards step by step, as shown in Fig. 8e. After the fifth iteration, novel lead-free solder alloys come out with high-strength and high-ductility, implying the effectiveness of the active learning in the optimization of strength-ductility simultaneously. Especially, the novel alloy Si-4 (\({{\rm{Sn}}}_{87.7}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{2.6}{{\rm{In}}}_{5.0}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{0.2}\)) and alloy Se-5 (\({{\rm{Sn}}}_{88.7}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{1.6}{{\rm{In}}}_{4.8}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{0.4}\)) exhibit outstanding mechanical properties in terms of strength and ductility, super than all alloys in the other sted alloys as well as the commercial solder Sn90.88Ag3.8Cu0.7Ni0.15Sb1.5Bi3.0, which is the lead-free solder with the best comprehensive mechanical properties51,52,53. The samples of the commercial solder are synthesized and tested in our lab, and the measured UTS and elongation are 85.41\(\pm\)0.91 MPa and 18.20\(\pm\)0.84%, respectively, in which both the UTS and elongation are slightly larger than the reported values of UTS of 83.0 MPa and elongation of 17.8%52,53. Supplementary Fig. 7a–c shows the repeated testing stress-strain curves for alloy Si-4, alloy Se-5, and commercial solder, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 7d shows the UTS and elongation values obtained from repeated tests for the three above-mentioned alloys. By employing the “Elongation-Based One-Sigma Repeated Testing Data Selection” method, seven, four, and five repeated test samples were selected for alloy Si-4, alloy Se-5, and commercial solder, respectively, to provide the reliable mean values and standard deviations (representing experimental uncertainty) for UTS and fracture elongation of the aforementioned alloys. Subsequently, the alloy Si-4 exhibits a tensile strength of about 89.74\(\pm\)1.56 MPa and an elongation of 21.6\(\pm\)1.39%, and the alloy Se-5 shows a tensile strength of about 86.01\(\pm\)1.31 MPa and an elongation of 23.80\(\pm\)2.49%, which are all surpassing the commercial solder. Fig. 8f shows one representative stress-strain curve for alloy Si-4, one for alloy Se-5, and one for commercial solder. The microstructures, fracture morphologies, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) phase analysis are conducted on the two novel alloys (Si-4 and Se-5) to understand the strengthening and toughening mechanisms.

Experimental characterization and mechanism exploration

Fig. 9a, b shows the optical micrographs of alloys Si-4 and Se-5, both consisting of two distinct regions: the Sn-based solid solution region (light regions) and the eutectic region (dark regions). Both alloys exhibit a special interlaced reticular structure in the eutectic region, formed by fine IMCs (Ag3Sn, Cu6Sn5) interspersed in the Sn matrix grains. This reticular structure is a key factor contributing to the high-strength and high-ductility of the designed two alloys, the details will be discussed later.

Optical microstructure images of alloys: a Si-4 and b Se-5; Backscattered electron (BSE) images of alloys: c Si-4, d Se-5; e EDS elemental distribution mapping of two alloys (Si-4 and Se-5), which correspond to the regions marked in (c, d); f X-ray Diffraction Patterns; SEM images (Secondary electron image) of fracture fractographs of g, h Si-4 and i, j Se-5.

Fig. 9c, d show the SEM images of alloys Si-4 and Se-5, indicating both alloys consist of a β-Sn region with dispersed IMC and/or precipitates. To identify the IMCs and precipitates, energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was carried out to analyze elemental distribution quantitatively over the regions marked in Fig. 9c, d. Fig. 9e shows the element distribution maps and Supplementary Tables 5, 6 show the elemental quantitative analysis. For both alloys Si-4 and Se-5, the Sn and In are distributed relatively evenly in the matrix, and the Ag and Cu are mainly enriched in the IMC (Ag3Sn, Cu6Sn5) precipitates. Additionally, for alloy Si-4, Bi is enriched in Bi precipitates, while for alloy Se-5, Ti is enriched in IMC Ti2Sn3 precipitates. Besides, the element In can also be dissolved into β-Sn matrix, causing solution-strengthening effect, considering In atomic radius of 0.155 nm and Sn atomic radius 0.144 nm75. In addition to substituting Sn atoms in β-Sn matrix, In atoms can replace the Sn atoms in IMCs Ag3Sn, Cu6Sn5, and Ti2Sn3, forming Ag3(Sn, In), Cu6(Sn, In)5 and Ti2(Sn, In)3.

Although both alloys contain Bi and In elements, the Bi precipitate particles are only observed in alloy Si-4 and the strip-shaped IMCs Ti2(Sn, In)3 are only observed in alloy Se-5. The Bi atoms can be dissolved into the Sn matrix with a solid solubility ~1.8 wt.%76,77,78,79. The 2.6 wt.% Bi concentration in alloy Si-4 causes the Bi precipitate particles, while its Ti concentration is 0.2 wt.%, which is low to cause detectable IMCs Ti2(Sn, In)3. In alloy Se-5, the Ti concentration is 0.4 wt.%, which leads to the IMCs Ti2(Sn, In)3, while the Bi concentration is 1.6 wt.% lower than the solid solubility about 1.8 wt.%66,67,68,69. Fig. 9f shows the XRD analyses for alloys Si-4 and Se-5, where the difference between the XRD patterns of the two alloys is very subtle. The XRD analysis confirmed that the two alloys including the dominant β-Sn phase and the IMCs Ag3Sn or Ag3(Sn, In) and Cu6Sn5 or Cu6(Sn, In), which are consistent with the previously reported results that the Ag3Sn and Cu6Sn5 IMC phases can exist in SAC solder alloys, as determined by the transmission electron microscopy (TEM)80,81,82.

Both Bi and In solute atoms in the β-Sn lattice yield the solid solution strengthening by creating lattice distortions that hinder the movement of dislocations, thereby increasing the strength of the material. The presence of the various IMCs of Ag3(Sn, In), Cu6(Sn, In)5 and Ti2(Sn, In)3 and Bi precipitates lead to precipitation strengthening, which effectively blocks the dislocation movements. However, large IMCs and precipitates might impair the ductility of the solder alloy since cracks could be initiated at the interface between the large precipitates and the Sn matrix. As mentioned above, both alloys exhibit a special interlaced reticular structure in the eutectic region, formed by fine IMCs interspersed within the Sn matrix grains. This microstructure has dense phase boundaries and hence causes the grain-boundary strengthening. Optimizing this microstructure can enhance both the strength and ductility simultaneously, as illustrated by the alloys Si-4 and Se-5.

Fig. 9g–j show the SEM fractography of alloys Si-4 and Se-5, after the tensile tests. Both alloys exhibit the mixture of dimples and quasi-cleavages, which is considered as the ductile/brittle mixed fracture mode, corresponding to the well-balanced mechanical properties.

Melting properties, wettability, and conductivity of solder alloys, and shear strength of solder joints

Solder alloys are generally used for joint connections. The other major intrinsic properties, including the melting properties, wettability and electrical conductivity, as well as the shear strength of the solder joint, should be considered besides the essential intrinsic strength and ductility of the solder alloys.

Melting properties are critical in the soldering process. A lower melting temperature is always desired to eliminate any potential damage caused by the soldering temperature3. The melting properties are determined by conducting DTA. Fig. 10a–c shows the DTA curves of the compared commercial solder alloy, Si-4 alloy, and Se-5 alloy. The liquidus temperature (Tim), solidus temperature (Tem) and the undercooling (∆T = Tim−Tem) of these three alloys were calculated based on the DTA curves and shown in Fig. 10d. The liquidus temperatures of alloys Si-4 and Se-5 are 199.4 °C and 201.4 °C, respectively, lower than the 207.4 °C of the commercial solder alloy; the undercooling of alloys Si-4 and Se-5 are 16.4 °C and 11.4 °C, respectively, also lower than the 17.8 °C of the commercial solder alloy. Both the novel solder alloys Si-4 and Se-5 exhibit lower melting temperatures and narrower undercooling than the compared commercial solder, indicating both excellent melting properties.

Wettability is one of the main factors affecting the bonding quality of solders. Excellent wettability is essential for forming a reliable joint for industrial applications83. Generally, a smaller contact angle indicates better wettability. Fig. 10g–i shows the measured contact angles of the three alloys, where the contact angles of the compared commercial solder alloy, Si-4 alloy, and Se-5 alloy are 36.7°, 38.1°, and 40.9°, respectively. Both of the novel solder alloys exhibit slightly larger contact angles than the commercial solder, meaning slightly poorer wettability. Even though, the contact angles of 38.1° and 40.9° of the novel alloys still indicate good wettability84.

Electrical conductivity of solder alloys is critical in their electronic package application, higher conductivity enabling better flow of electrical current for reliable connections between components. Fig. 10e shows the electrical conductivity comparison results, in units of IACS (International Annealed Copper Standard for conductivity), where the conductivity of alloys Si-4 and Se-5 are 13.51% IACS and 14.42% IACS, respectively, compared to 12.9% IACS for the commercial solder alloy. Both of the novel solder alloys exhibit superior electrical conductivity compared to the commercial solder.

Shear strength is the key property of the solder joint, as it determines the ability of the joint to withstand mechanical stresses and vibrations during the lifecycle of the electronic device. Insufficient shear strength of solder joints can cause them to easily break under mechanical stress, resulting in unstable connections, electrical interruptions, or even detachment of electronic components. Fig. 10f shows the comparison of the shear strength of solder joints of the three alloys, where the shear strength of the solder joint is 104.61 MPa, 99.96 MPa and 97.20 MPa for the compared commercial solder alloy, the Si-4 alloy, and the Se-5 alloy, respectively. The commercial solder exhibits the maximum shear strength of the solder joint. The reason for the slight difference between the shear strength and the UTS might be caused by the interface bonding between the solder and the Cu substrate, which might highly depend on the contact angle. Nevertheless, the shear strengths of the two novel alloys might meet the requirement in some electronic packaging applications.

Discussion

The present multi-objective Bayesian active learning framework shows that adding experimental data uncertainty into the GPR models can greatly enhance the prediction accuracy. Specifically, across 14 different datasets (from seven iterations with two tensile properties of UTS and elongation), adding the experimental uncertainty into the GPR models resulted in significant improvements in prediction accuracy of LOOCV-R2 on 13 datasets, compared to the models that without the consideration of data uncertainty; in particular, at the last iteration, from 0.609 to 0.814 for UTS and from 0.716 to 0.794 for elongation. The results demonstrate that experimental data uncertainty must be considered especially when the data is small. Small data must be reliable in terms of mean and standard deviation. As described in the statistical learning of small data34, the χ2 test and t-test can statistically test whether the standard deviation and mean of small data are reliable. Unreliable experimental data will greatly damage ML models and, hence, active learning.

Active leaning is a dynamic iteration process and each iteration updates the dataset, ML models, Bayesian sampling and experiment. Caution must be used in the recommendation of candidates for next experiment that the prediction uncertainty and the thresholds must be appropriate, otherwise the experimental results will deviate from the predictions. The active learning of seven iterations discovers two novel solder alloys of \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{87.7}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{2.6}{{\rm{In}}}_{5.0}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{0.2}\)(Si-4) and \({{\rm{Sn}}}_{88.7}{{\rm{Ag}}}_{3.8}{{\rm{Cu}}}_{0.7}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{1.6}{{\rm{In}}}_{4.8}{{\rm{Ti}}}_{0.4}\)(Se-5) with super high strengths of 89.74\(\pm\)1.56 MPa and 86.01\(\pm\)1.31 MPa and high-ductilities of 21.6\(\pm\)1.39% and 23.80\(\pm\)2.49%, respectively, super than the corresponding values of the commercial solder Sn90.88Ag3.8Cu0.7Ni0.15Sb1.5Bi3.0.

The novel alloys Si-4 and Se-5 also exhibit excellent comprehensive properties in terms of the intrinsic mechanical properties, melting properties, electrical conductivity, wettability, and shear strength of the joint, which are expected to be widely applied in industry.

Data availability

All experimental data in the study are contained in Main Text and Supplementary Information.

References

Cheng, S., Huang, C. M. & Pecht, M. A review of lead-free solders for electronics applications. Microelectron. Reliab. 75, 77–95 (2017).

Siahaan, E. Behavior of Sn-0.7 Cu-xZn lead free solder on physical properties and micro structure. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 237, 12044 (2017).

Lu, T., Yi, D., Wang, H., Tu, X. & Wang, B. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and interfacial reaction with Cu substrate of Zr-modified SAC305 solder alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 781, 633–643 (2019).

Tang, C., Zhu, W., Chen, Z. & Wang, L. Thermomechanical reliability of a Cu/Sn-3.5 Ag solder joint with a Ni insertion layer in flip chip bonding for 3D interconnection. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 32, 11893–11909 (2021).

Soares, T. et al. Interplay of wettability, interfacial reaction and interfacial thermal conductance in Sn-0.7 Cu solder alloy/substrate couples. J. Electron. Mater. 49, 173–187 (2020).

Al-Ezzi, A., Al-Bawee, A., Dawood, F. & Shehab, A. A. Effect of bismuth addition on physical properties of Sn-Zn lead-free solder alloy. J. Electron. Mater. 48, 8089–8095 (2019).

Hirata, Y., Yang, C. H., Lin, S. K. & Nishikawa, H. Improvements in mechanical properties of Sn–Bi alloys with addition of Zn and In. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 813, 141131 (2021).

Chen, W. M., Zhang, L. J., Du, Y. & Huang, B. Y. Diffusivities and atomic mobilities of Sn-Ag and Sn-In melts. J. Electron. Mater. 43, 1131–1143 (2014).

Zhang, L., Long, W. M. & Wang, F. J. Microstructures, interface reaction, and properties of Sn–Ag–Cu and Sn–Ag–Cu–0.5 CuZnAl solders on Fe substrate. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 31, 6645–6653 (2020).

Fan, J. et al. Effect of Ni content on the microstructure formation and properties of Sn-0.7Cu-xNi solder alloys. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 29, 4934–4943 (2020).

Suganuma, K. Advances in lead-free electronics soldering. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 5, 55–64 (2001).

Wu, J. et al. Recent progress of Sn–Ag–Cu lead-free solders bearing alloy elements and nanoparticles in electronic packaging. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 27, 12729–12763 (2016).

Chen, X., Ma, X., Deng, Y., Gao, P. & Li, L. The microstructure, melting properties and wettability of Sn–3.5Ag–0.7Cu–xIn lead-free solder alloys. Philos. Mag. 102, 321–339 (2022).

Wang, Y., Wang, G., Song, K. & Zhang, K. Effect of Ni addition on the wettability and microstructure of Sn2.5Ag0.7Cu0.1RE solder alloy. Mater. Des. 119, 219–224 (2017).

Ali, B., Sabri, M. F. M., Jauhari, I. & Sukiman, N. L. Impact toughness, hardness and shear strength of Fe and Bi added Sn-1Ag-0.5Cu lead-free solders. Microelectron. Reliab. 63, 224–230 (2016).

Ma, Z. L., Belyakov, S. A. & Gourlay, C. M. Effects of cobalt on the nucleation and grain refinement of Sn-3Ag-0.5Cu solders. J. Alloy. Compd. 682, 326–337 (2016).

Kim, D. H., Cho, M. G., Seo, S. K. & Lee, H. M. Effects of Co addition on bulk properties of Sn-3.5Ag solder and interfacial reactions with Ni-PUBM. J. Electron. Mater. 38, 39–45 (2009).

Shang, H., Ma, Z. L., Belyakov, S. A. & Gourlay, C. M. Grain refinement of electronic solders: the potential of combining solute with nucleant particles. J. Alloy. Compd. 715, 471–485 (2017).

Nadhirah, M. N., Maslinda, K., Nurulakmal, M. S. & Anasyida, A. S. Isothermal aging of low-Ag SAC with Al addition. Procedia Chem. 19, 492–497 (2016).

Sabri, M. F. M. et al. Microstructural stability of Sn–1Ag–0.5Cu–xAl (x= 1, 1.5, and 2 wt.%) solder alloys and the effects of high-temperature aging on their mechanical properties. Mater. Charact. 78, 129–143 (2013).

Wang, J. X. et al. Effects of rare earth Ce on microstructures, solderability of Sn–Ag–Cu and Sn–Cu–Ni solders as well as mechanical properties of soldered joints. J. Alloy. Compd. 467, 219–226 (2009).

Zhang, L., Fan, X. Y., Guo, Y. H. & He, C. W. Properties enhancement of SnAgCu solders containing rare earth Yb. Mater. Des. 57, 646–651 (2014).

Tu, X., Yi, D., Wu, J. & Wang, B. Influence of Ce addition on Sn-3.0Ag-0.5Cu solder joints: thermal behavior, microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 698, 317–328 (2017).

Gao, L. et al. Effects of trace rare earth Nd addition on microstructure and properties of SnAgCu solder. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 21, 643–648 (2010).

Belyakov, S. A. & Gourlay, C. M. Heterogeneous nucleation of βSn on NiSn4, PdSn4 and PtSn4. Acta Mater. 71, 56–68 (2014).

Lin, F., Bi, W., Ju, G., Wang, W. & Wei, X. Evolution of Ag3Sn at Sn–3.0Ag–0.3Cu–0.05Cr/Cu joint interfaces during thermal aging. J. Alloy. Compd. 509, 6666–6672 (2011).

Giuranno, D., Delsante, S., Borzone, G. & Novakovic, R. Effects of Sb addition on the properties of Sn-Ag-Cu/(Cu, Ni) solder systems. J. Alloy. Compd. 689, 918–930 (2016).

Osório, W. R., Peixoto, L. C., Garcia, L. R., Mangelinck-Noël, N. & Garcia, A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Sn–Bi, Sn–Ag and Sn–Zn lead-free solder alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 572, 97–106 (2013).

Siewert, T., Liu, S., Smith, D. R. & Madeni, J. C. Database for solder properties with emphasis on new lead-free solders. NIST Colo. Sch. Mines 4, 1–77 (2002).

El-Daly, A. A., El-Hosainy, H., Elmosalami, T. A. & Desoky, W. M. Microstructural modifications and properties of low-Ag-content Sn–Ag–Cu solder joints induced by Zn alloying. J. Alloy. Compd. 653, 402–410 (2015).

Kang, S. K. et al. Interfacial reactions of Sn-Ag-Cu solders modified by minor Zn alloying addition. J. Electron. Mater. 35, 479–485 (2006).

Kang, S. K. et al. Controlling Ag 3 Sn plate formation in near-ternary-eutectic Sn-Ag-Cu solder by minor Zn alloying. JOM 56, 34–38 (2004).

El-Daly, A. A. & El-Taher, A. M. Evolution of thermal property and creep resistance of Ni and Zn-doped Sn–2.0Ag–0.5Cu lead-free solders. Mater. Des. 51, 789–796 (2013).

Wang, J. H., Jia, J. N., Sun, S. & Zhang, T. Y. Statistical learning of small data with domain knowledge-sample size-and pre-notch length-dependent strength of concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 259, 108160 (2022).

Rao, Z. et al. Machine learning–enabled high-entropy alloy discovery. Science 378, 78–85 (2022).

Lu, T., Li, M., Lu, W. & Zhang, T. Recent progress in the data-driven discovery of novel photovoltaic materials. J. Mater. Inform. 2, 7 (2022).

Wen, C. et al. Machine learning assisted design of high entropy alloys with desired property. Acta Mater. 170, 109–117 (2019).

Chong, X. et al. Understanding oxidation resistance of Pt-based alloys through computations of Ellingham diagrams with experimental verifications. J. Mater. Inform. 3, 21 (2023).

Shi, B. et al. Estimating the performance of a material in its service space via Bayesian active learning: a case study of the damping capacity of Mg alloys. J. Mater. Inform. 2, 8 (2022).

Vandermause, J., Xie, Y., Lim, J. S., Owen, C. J. & Kozinsky, B. Active learning of reactive Bayesian force fields applied to heterogeneous catalysis dynamics of H/Pt. Nat. Commun. 13, 5183 (2022).

Khatamsaz, D. et al. Multi-objective materials bayesian optimization with active learning of design constraints: design of ductile refractory multi-principal-element alloys. Acta Mater. 236, 118133 (2022).

Zhang, D., Yi, P., Lai, X., Peng, L. & Li, H. Active machine learning model for the dynamic simulation and growth mechanisms of carbon on metal surface. Nat. Commun. 15, 344 (2024).

Cao, B., Yang, S., Sun, A., Dong, Z. & Zhang, T. Domain knowledge-guided interpretive machine learning: formula discovery for the oxidation behavior of ferritic-martensitic steels in supercritical water. J. Mater. Inform. 2, 4 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Machine learning assisted multi-objective optimization for materials processing parameters: a case study in Mg alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 844, 156159 (2020).

Xi, S. et al. Machine learning-accelerated first-principles predictions of the stability and mechanical properties of L12-strengthened cobalt-based superalloys. J. Mater. Inform. 2, 15 (2022).

Li, K. et al. Exploiting redundancy in large materials datasets for efficient machine learning with less data. Nat. Commun. 14, 7283 (2023).

Wu, D. Y. & Hufnagel, T. C. Efficient searching of processing parameter space to enable inverse microstructural design of materials. Acta Mater. 264, 119562 (2024).

Yuan, H., Cao, B., Dong, Z. & Zhang, T. Y. Mechanical properties prediction and alloy design of lead-free solder alloy assisted by machine learning (in Chinese). Sci. Sin. 46, 79–90 (2022).

Wei, Q. et al. Divide and conquer: Machine learning accelerated design of lead-free solder alloys with high strength and high ductility. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 201 (2023).

Cao, B. et al. Active learning accelerates the discovery of high strength and high ductility lead-free solder alloys. Mater. Des. 241, 112921 (2024).

Chowdhury, M. R., Ahmed, S., Fahim, A., Suhling, J. C. & Lall, P. Mechanical characterization of doped SAC solder materials at high temperature. In: 15th IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016, pp.1202–1208, https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHERM.2016.7517684 (2016).

MacDermid Alpha. ALPHA® INNOLOT SOLDER ALLOY. www.macdermidalpha.com. URL: https://www.macdermidalpha.com/sites/default/files/2021-11/ALPHA-Innolot-Solid-Solder-EN-09Mar21-TB.pdf (2021).

MacDermid Alpha. ALPHA® INNOLOT SOLDER PREFORMS. www.macdermidalpha.com. URL: https://www.macdermidalpha.com/assembly-solutions/products/solder-preforms/alpha-innolot-solder-preforms (2024).

Lookman, T., Balachandran, P. V., Xue, D. & Yuan, R. Active learning in materials science with emphasis on adaptive sampling using uncertainties for targeted design. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 21 (2019).

Acar, P. Recent progress of uncertainty quantification in small-scale materials science. Prog. Mater. Sci. 117, 100723 (2021).

Vela, B., Khatamsaz, D., Acemi, C., Karaman, I. & Arróyave, R. Data-augmented modeling for yield strength of refractory high entropy alloys: a bayesian approach. Acta Mater. 261, 119351 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Bayesian-optimization-assisted discovery of stereoselective aluminum complexes for ring-opening polymerization of racemic lactide. Nat. Commun. 14, 3647 (2023).

Dalton, K. M., Greisman, J. B. & Hekstra, D. R. A unifying Bayesian framework for merging X-ray diffraction data. Nat. Commun. 13, 7764 (2022).

Tian, Y. et al. Determining multi‐component phase diagrams with desired characteristics using active learning. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003165 (2021).

Yuan, R. et al. Accelerated search for BaTiO3‐based ceramics with large energy storage at low fields using machine learning and experimental design. Adv. Sci. 6, 1901395 (2019).

Kusne, A. G. et al. On-the-fly closed-loop materials discovery via Bayesian active learning. Nat. Commun. 11, 5966 (2020).

Sauer, A., Gramacy, R. B. & Higdon, D. Active learning for deep Gaussian process surrogates. Technometrics 65, 4–18 (2023).

Sun, Y., Liang, J., Xu, Z. H., Wang, G. & Li, X. Nanoindentation for measuring individual phase mechanical properties of lead free solder alloy. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 19, 514–521 (2008).

Zhang T.-Y. An introduction to materials informatics (I): the elements of machine learning. Beijing, Science Press (2022).

Williams, C. & Rasmussen, C. Gaussian processes for regression. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS'95). MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 514–520 (1995).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. Gaussian processes for machine learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT press (2006).

Jones, D. R., Schonlau, M. & Welch, W. J. Efficient global optimization of expensive black-box functions. J. Glob. Optim. 13, 455–492 (1998).

Kushner, H. J. A new method of locating the maximum point of an arbitrary multipeak curve in the presence of noise. J. Basic Eng. 86, 97–106 (1964).

Auer, P. Using confidence bounds for exploitation-exploration trade-offs. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 397–422 (2002).

MacLeod, B. P. et al. A self-driving laboratory advances the Pareto front for material properties. Nat. Commun. 13, 995 (2022).

Jiang, L. et al. Synchronously enhancing the strength, toughness, and stress corrosion resistance of high-end aluminum alloys via interpretable machine learning. Acta Mater. 270, 119873 (2024).

Chitturi, S. R. et al. Targeted materials discovery using Bayesian algorithm execution. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 156 (2024).

Startt, J., McCarthy, M. J., Wood, M. A., Donegan, S. & Dingreville, R. Bayesian blacksmithing: discovering thermomechanical properties and deformation mechanisms in high-entropy refractory alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 164 (2024).

Ji, F. et al. Multi-objective Bayesian active learning for MeV-ultrafast electron diffraction. Nat. Commun. 15, 4726 (2024).

Slater, J. C. Atomic radii in crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 41, 3199–3204 (1964).

Beáta, Š., Erika, H. & Ingrid, K. Development of SnAgCu solders with Bi and In additions and microstructural characterization of joint interface. Weld. World 61, 613–621 (2017).

He, M., Ekpenuma, S. N. & Acoff, V. L. Microstructure and creep deformation of Sn-Ag-Cu-Bi/Cu solder joints. J. Electron. Mater. 37, 300–306 (2008).

Braga, M. H. et al. The experimental study of the Bi–Sn, Bi–Zn and Bi–Sn–Zn systems. Calphad 31, 468–478 (2007).

Witkin, D. Creep behavior of Bi-containing lead-free solder alloys. J. Electron. Mater. 41, 190–203 (2012).

Cui, Y. et al. Nucleation and growth of Ag3Sn in Sn-Ag and Sn-Ag-Cu solder alloys. Acta Mater. 249, 118831 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Preparation, characterization and mechanical properties analysis of SAC305-SnBi-Co hybrid solder joints for package-on-package technology. Mater. Charact. 208, 113624 (2024).

Liu, J., Xu, J., Paik, K. W., He, P. & Zhang, S. In-situ isothermal aging TEM analysis of a micro Cu/ENIG/Sn solder joint for flexible interconnects. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 169, 42–52 (2024).

Mhd Noor, E. E., Mhd Nasir, N. F. & Idris, S. R. A. A review: lead free solder and its wettability properties. Soldering Surf. Mt. Technol. 28, 125–132 (2016).

Erer, A. M., Oguz, S. & Türen, Y. Influence of bismuth (Bi) addition on wetting characteristics of Sn-3Ag-0.5Cu solder alloy on Cu substrate. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 21, 1159–1163 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the Shanghai Pujiang Program (Grant no. 20PJ1403700), the Guangzhou-HKUST(GZ) Joint Funding Program (nos. 2023A03J0003 and 2023A03J0103) and the Opening Project Fund of Materials Service Safety Assessment Facilities (MSAF-2024-107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, writing-original draft. Y.W., G.Y., T.L., and S.Y. analyzed the experimental data. Z.D.: supervised and guided the experimental research, analyzed the experimental data, and revised the manuscript. T.-Y.Z.: supervision, methodology, final writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Q., Wang, Y., Yang, G. et al. Discovering novel lead-free solder alloy by multi-objective Bayesian active learning with experimental uncertainty. npj Comput Mater 11, 10 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01480-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01480-7

This article is cited by

-

AI-aided bi-objective optimization of honeycomb metastructures for enhanced microwave absorption and mechanical resistance

Science China Technological Sciences (2025)

-

Past, present, prospect: AI-driven evolution of low-dimensional material design for sustainable environmental solutions

Rare Metals (2025)