Abstract

The fusion of experimental automation and machine learning has catalyzed a new era in materials research, prominently featuring Gaussian Process (GP) Bayesian Optimization (BO) driven autonomous experiments. Here we introduce a Dual-GP approach that enhances traditional GPBO by adding a secondary surrogate model to dynamically constrain the experimental space based on real-time assessments of the raw experimental data. This Dual-GP approach enhances the optimization efficiency of traditional GPBO by isolating more promising space for BO sampling and more valuable experimental data for primary GP training. We also incorporate a flexible, human-in-the-loop intervention method in the Dual-GP workflow to adjust for unanticipated results. We demonstrate the effectiveness of the Dual-GP model with synthetic model data and implement this approach in autonomous pulsed laser deposition experimental data. This Dual-GP approach has broad applicability in diverse GPBO-driven experimental settings, providing a more adaptable and precise framework for refining autonomous experimentation for more efficient optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The combination of experimental automation and machine learning techniques has ushered in a transformative era of autonomous experimentation, revolutionizing materials research by accelerating scientific discovery through high-throughput processes and data-driven decision-making1. Bayesian Optimization2 (BO) plays a pivotal role in autonomous experiments for efficient optimization of target (objective) properties and exploration across extensive experimental conditions3,4. BO starts by making a statistical approximation of the unknown objective function in the experimental space, called a surrogate model, based on results from previously conducted experiments. The surrogate model for BO could be a random forest5 or neural network6,7 but is most commonly a Gaussian Process (GP)8 due to its non-parametric nature and built-in uncertainty quantification9,10. Once the surrogate model is constructed, a variety of acquisition functions11 can be calculated to determine the next set of experimental conditions that potentially reduce the surrogate’s uncertainty, approach the global optimum, or maximize understanding of the system. Through this process, GPBO efficiently navigates vast experimental spaces, optimizing a target property or enhancing understanding with a minimum number of costly experiments.

GPBO has demonstrated applications in many materials science areas from theoretical predictions and materials design to materials synthesis and characterization. GPBO has been used for the prediction of crystal structures12,13 and for theoretical design of materials14,15,16. Autonomous synthesis methods that employ GPBO to efficiently optimize a target property vary from carbon nanotube growth17,18,19, chemical synthesis20,21, physical vapor deposition22,23,24, and additive manufacturing25,26,27,28. It has enabled autonomous exploration and discovery in piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM)29,30,31, scanning tunneling microscopy32,33, and scanning transmission electron microscopy34.

In the examples discussed above, a GP is utilized to map the relationship between inputs (e.g., chemical compositions, synthesis parameters, and characterization parameters) and outputs (e.g., target material properties). When target properties are quantifiable through scalar measurements, the scalar descriptors of target properties can be directly employed with the corresponding input parameters for GP training. However, in many real-world experiments, material properties are characterized by non-scalar data like spectroscopy, images, hyperspectral images, or higher dimensional and multi-modal data. This necessitates the use of “scalarizer functions” that derive meaningful scalar descriptors from the non-scalar raw data; subsequently, these scalar descriptors, instead of the raw data, are employed along with the corresponding measurement or synthesis parameters for GP training. Scalarizer functions can vary from simple functions like peak identification35 to custom algorithms for specific physical attributes like the coercive field from polarization-voltage hysteresis loops in PFM29,36,37 or even pre-trained neural networks designed to reduce high-dimensional data into simpler physical descriptors. Typically, in a GPBO-driven experiment, a scalarizer function is predefined before the experiment based on prior knowledge or expectation of experiment outcomes; then, the same scalarizer function is applied throughout the entire GPBO-driven experiment.

The process of materials and scientific discovery can be intertwined with the framework of “known knowns, known unknowns, unknown knowns, and unknown unknowns”. The “known knowns” represent the established prior knowledge and “known unknowns” are the gaps in current understanding that can be explored. Scalarizer functions are often designed based on prior knowledge (i.e., known knowns), improving scalarizer functions can potentially allow to address expected gaps (i.e., known unknowns) in the experimental systems. Notably, the real-world complexity of experiments often leads to unanticipated assumptions and phenomena (i.e., unknown knowns and unknown unknowns), which can revolutionize our understanding at the frontier of scientific research. However, pre-defined scalarizer functions based on prior knowledge often lack the flexibility for analyzing these unanticipated results. For example, a scalarizer function used to identify the maximum peak intensity in spectroscopic data will fail to discern distinct spectra with peaks at different frequency and consequently will assign the identical scalar descriptor to peaks with different meanings (e.g. peaks with the same amplitude but at a different frequency). Moreover, in real experimental data, the occurrence of unanticipated modulations in the data such as additional background signal from unexpected light scattering in optical spectroscopy, complete lack of signal due to an experimental error during unsupervised, automated experiments, or any number of other complications, cannot be effectively anticipated during the creation of a scalarizer function. These can distort the true relationship between experiment conditions and target properties and significantly mislead the GP. Therefore, we need a quality control of the raw experiment results to check their compatibility with the predefined scalarizer function, in doing so, ensure the quality of the converted scalarizers and the training dataset.

To tackle the above challenges and limitations of scalarizer functions used in GPBO-driven experimentation, we propose to use a 2nd GP in tandem with the primary GPBO, as a solution to dynamically constrain the exploration space to areas that potentially produce more valuable results. This Dual-GP approach maintains the target property optimization driven by the traditional GPBO process and adds a 2nd GP to dynamically constrain the experimental space based on observation of raw experimental data. The constraint of the 2nd GP can be according to the compatibility between raw experimental data and scalarizer function, or the quality of the raw data, or additional assessment of material properties, etc. We also add an interface that allows human-in-the-loop intervention to account for unanticipated results. We demonstrate the application of the Dual GP in synthetic model data and experimental pulsed laser deposition (PLD) synthesis data; however, this approach can be applied to any other GPBO-driven experiments as well.

Results

The Dual-GP workflow

Traditionally, as shown in Fig. 1a, a single GP within a BO framework starts by assessing seed experiment conditions. The seed conditions are selected either randomly or by human choice. In this GPBO driven experiment loop, it is the scalar physical descriptor rather than raw experiment data that is used for GPBO analysis. Therefore, defining a scalarizer function, based on prior knowledge, is a crucial step for deriving physical descriptors from raw experimental data. As previously discussed, pre-defined scalarizer functions may fail to apply meaningful descriptors to certain data, resulting in irrelevant or meaningless scalar values that contaminate the dataset and mislead the GP approximation and BO selection. Failure of a scalarizer function can arise from various factors, such as large noise in the spectra, the presence of outliers, or the emergence of new physical phenomena not accounted for by the pre-defined scalarizer function. Additionally, it is virtually impossible to form a robust scalarizer to handle data that we cannot anticipate.

a The workflow for traditional GPBO driven experiments starts with a few seed experimental conditions; performing experiments followed by preprocessing of converting the raw experimental data to scalar physical descriptors using a predefined scalarizer function; then the experiment conditions and scalar descriptors form a trainset to train a GP (surrogate model); next acquisition function determines the next experimental conditions based on the GP prediction and uncertainty. b–g examples of raw experimental photoluminescence (PL) results of hybrid organic inorganic compounds and corresponding scalar descriptors. The find_peaks function in SciPy is used as a scalarizer function to convert raw PL to scalar descriptor of emission wavelength. b, c shows scalar descriptors of high quality, while the scalar descriptors (that only represent the wavelength of the highest PL peak) in (d–g) miss crucial information in the raw spectra. This variation in scalarizer quality can mislead the GPBO driven experiments.

Figure 1b–g showcases the use of a scalarizer function to transform raw data into a scalar descriptor, illustrating the limitations of a predefined scalarizer function in analyzing experimental results. The raw spectral data displayed in Fig. 1b-g are from the HybriD3 materials database, (https://materials.hybrid3.duke.edu/) which provides a collection of experimental and computational data on hybrid organic-inorganic (HOI) compounds. These figures specifically present experimental photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy results for HOI including hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites (HOIPs). An essential application of HOIPs lies in photovoltaic and light-emitting devices, where tuning the bandgap is crucial for either enhancing light absorption for photovoltaics or achieving emitting light of a specific color for light-emitting devices. The bandgap can be inferred from the PL emission wavelength, thus it has been used as a valuable physical descriptor for optimizing HOIPs bandgap35. The PL emission wavelength can be extracted from the raw spectrum by identifying the PL peak position, which can be accomplished using the find_peaks function in SciPy38. This function allows users to customize parameters like peak height and width, and returns details of the identified peaks, including peak positions. Thus, we use this find_peaks function as a scalarizer function to convert PL raw spectrum to physical descriptor of emission wavelength, details regarding the analysis of these PL spectra and scalar descriptors conversion can be found in the Supplementary Notebook I that is also publicly available on GitHub, a link is available in the Methods section.

As indicated by the vertical red dashed lines in Fig. 1b–g, the scalarizer function effectively identifies the wavelength of the highest peak. However, the quality of these scalarizers varies significantly. For instance, the scalarizers in Fig. 1b and c are of high quality, where the raw PL spectra predominantly contain a single major peak39,40. In contrast, scalarizers from Fig. 1d–f reveal significant limitations: the scalarizer only marks the highest emission peak, failing to account for additional phenomena in the spectra—e.g., a secondary broad peak appearing after 400 nm in Fig. 1d40, significant asymmetry of the peak in Fig. 1e41, and a secondary shoulder peak in Fig. 1f and g42,43. These features, which involve additional physics like broad emission40, self-trapped exciton41, and ligand-contributed emissions42,43, are critical for bandgap engineering but are overlooked by the predefined scalarizer function. Notably, it is virtually impossible to define a scalarizer function that can capture all known physical phenomena in the raw results, let alone unknown aspects.

Therefore, the quality of scalar physical descriptors can significantly vary due to complexities in the raw experimental data. Using these descriptors of varying quality in a training set could potentially mislead the GPBO-driven experiment; for instance, although Fig. 1e and f result in similar scalarizers (415 nm vs. 418 nm), the exact materials’ properties, which can be examined from the raw spectra, are significantly different. To address this issue, we propose to use a 2nd GP as an observer, as shown in Fig. 2, which assesses the quality of the raw data or its compatibility with the predefined scalarizer function to predict the applicability of the scalarizer function in the experimental space. This approximation can be used to assign a quality score to the experimental space, which examines the relevance of the acquired raw data and the predefined scalarizer function. Subsequently, the quality score can be used as a dynamic constraint on the exploration space, constraining the BO to focus on the space where the scalarizer is likely of high quality. This dynamic constraint has the potential to further accelerate the BO workflow by filtering out the space with the low probability of acquiring useful data and low-quality scalarizers.

A 2nd GP analyzes the quality of resultant scalarizer, this quality can be obtained via examining the compatibility of the scalarizer function and the raw data. This prediction is used to actively refine the exploration space and modify the acquisition values. In doing so, the aim is to make the primary GPBO (which is driving experiment) avoid noisy or infeasible space.

We propose to design an observer function by comparing the on-the-fly raw experimental spectral data against a reference spectrum, this reference spectrum embodies the expected outcomes and is highly compatible with the predefined scalarizer function. The reference spectrum can be from seed experiments or theory. This comparison can be quantified by metrics such as Structural Similarity Index (SSI), Mean Square Error (MSE), etc., to assess whether the real-time raw spectrum is compatible with the predefined scalarizer function. The 2nd GP is trained on the metric and refines the experimental space to focus on regions likely to yield spectra relevant to the predefined scalarizer function. This strategy dynamically adjusts the exploration space of the primary GPBO with insights from the 2nd GP, increasingly focusing on the space predicted to align with experimental goals. Thus, the integration of a 2nd GP enables a dynamic, goal-aligned refinement of the experimental landscape, ensuring a more streamlined and efficient exploration.

Comparing single GPBO and Dual-GP BO

To illustrate how Dual-GP can discern and prioritize the experimental space, we conducted a numerical experiment using a synthetic spectrum model with varying noise and compared the single GP and Dual-GP methods’ ability to reconstruct the ground truth and determine the model’s parameters based on limited observations. Each input x produces a spectrum with a single Gaussian peak whose amplitude is given by Eq. 1:

where A = 0.5; B = −1.2; and C = 0.5. We introduced higher noise to the spectra in the range x ∈ [0.7, 1.0] to simulate “bad” experimental measurement conditions. Consequently, the amplitude extracted by the scalarizer function deviates from the true function within this range, as shown in Fig. 3a, which can potentially mislead the GPBO optimization. A few examples of spectra are presented in Fig. 3b. We implemented a structured GP (sGP)44 for the primary GP in order to predict the model parameters. In sGP, we structured the mean function of the GP with the functional form of the amplitude model and placed a prior distribution on the parameters. We refer ref. 44 for further interest in sGP. The scalarizer function is constructed with find_peaks method to extract the peak amplitude as the scalar physical descriptor and the BO used an uncertainty-based acquisition function that selects the next point based on maximum GP uncertainty. The quality metric for 2nd GP training is quantified via SSI between measured spectra and a reference spectrum; this reference spectrum is an example of a low noise spectrum that has a good compatibility with the predefined scalarizer function and results in a scalarizer of high quality. The SSI of all synthetic spectra is in Supplementary Notebook II that is also publicly available in GitHub, a link is provided in the Methods section; high noise spectrum generally led to low SSI. The 2nd GP is trained by the SSI of measured spectra and predicts the SSI in the unexplored space. Thus, the predicted SSI of the unexplored space indicates the possibility of the unexplored space to produce high-quality scalarizers. The acquisition function of the primary GPBO is set to zero where the predicted SSI score < 0.3, in doing so, a constraint is applied to the primary GPBO to only explore the space where the SSI score is larger than 0.3, which has a larger potential to produce high-quality results and scalarizers.

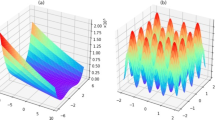

a amplitude of the synthetic peak model data for the Dual-GP test, here the noise quickly increases when x > 0.7, leading to resultant scalarizers diverging from the true function. b Examples of a good raw spectrum and noisy spectra. c Single GP exploration result after 50 iterations, d Dual-GP exploration result after 50 iterations. e–g Show the sGP parameter prediction of Dual-GP approaches the true values more quickly than the single GP.

Results for the single GP and Dual-GP are shown in Fig. 3c and d, respectively, after 50 exploration steps. The single GPBO selected many points within the high noise subspace which reduce the GP surrogate’s reconstruction accuracy, hence hindering the optimization process. In comparison, the 2nd GP in the Dual-GP effectively identified that the subspace with high noise is the region x ∈ [0.7, 1.0], and hence ensures the primary GPBO avoids this subspace. Throughout exploration, the parameters of the structured mean function are updated to capture the underlying system behavior. Thus, by comparing the evolution of mean function parameters with the ground truth parameters, we can gain insights into the optimization process of single GP and Dual-GP. As shown in Fig. 3e–g, the predicted parameters approach the ground truth quicker in Dual-GP driven optimization, indicating a more efficient optimization with Dual-GP.

We also analyzed the run-to-run variability of single GP and Dual GP approaches across 10 runs with varying initial seed measurement points. The results are in shown in Supplementary Information Figure S1–S3. It indicates that the Dual-GP incorporating an observer function to assess raw data quality not only approaches the ground truth quicker but also presents lower variability across 10 runs, suggesting a more robust performance of Dual-GP approach.

Human-in-the-loop

Above we used a predefined metric (i.e., SSI of raw experimental spectra to a reference spectrum) to assess the quality of raw experimental data and its compatibility with the predefined scalarizer function, this metric is defined according to our prior knowledge and/or anticipation of the experimental results. In some cases of real experiments, it is not possible to anticipate how the real-time experimental results will look like, and hence the quality of raw results cannot be assessed via a predefined metric; in these cases, real time human evaluation becomes an invaluable metric for determining the quality of the raw data and if it can yield meaningful scalarizers. To integrate human in the GPBO loop using the Dual-GP approach, human experts can review the collected raw spectral data and assign a quality score to each spectrum according to knowledge and/or interest. These scores, reflecting the relevance and the quality of the spectra, are then used to train the 2nd GP. Incorporating human assessment in this manner offers significant flexibility and adaptability, making it a universally applicable approach in scenarios where prior knowledge and reasonable anticipation about the material system is limited or unavailable.

To demonstrate how the human-in-the-loop Dual-GP model can prioritize the experimental domain, we generated another synthetic spectral dataset using Eq. (1) with peak amplitude parameters A = 0.3; B = −1; and C = 0.5 and, instead of increased noise as before, we introduced random distortions which alter the raw spectra in the region x ∈ [0.3, 0.6]. The distortion is introduced by adding an additional peak with random location, amplitude, and width. The likelihood of introducing this distortion to a specific raw data set is also determined randomly. This random distortion to raw data is to mimic the ‘unanticipated’ scenario in a real experiment, it is noteworthy that some of the real experimental spectral data in Fig. 1 exhibit similar distortion. The true amplitude function is shown in Fig. 4a and the examples of distorted spectra are shown in Fig. 4b. The assumption is that these distortions are unknown prior to experiment and cannot be reasonably represented by a predefined metric, necessitating real-time human assessment of the quality of raw spectra and their compatibility with the scalarizer function. We used the same sGP scheme and acquisition function as the previous experiment to demonstrate the human-in-loop Dual GP exploration of this model data. For the 2nd GP, after every 9 (this can be modified by users) exploration steps, the human expert is prompted to rank the last 9 spectra from 1–10 with 10 being “good” and this score was given to the 2nd GP to predict where high score spectra may be. Based on the prediction, the next iteration sampling is constrained in the subspace where the predicted score is >3, which is likely to lead to higher quality experimental data.

a Amplitude of the synthetic peak model data, random distortion is added in the raw data in the space x ∈ [0.3, 0.6], leading to resultant scalarizers diverging from the true function. b Examples of a good raw spectrum and distorted spectra. c Single GP exploration result after 50 iterations, d Dual-GP exploration result after 50 iterations, here human experts assess raw spectra every 9 iterations (this can be flexible) and assign a quality score to the raw spectra based on the assessment; low-quality score indicates the raw spectrum is not compatible with the predefined scalarizer function for various reasons. e–g Show that Dual-GP approximated the true function parameter better than the single GP.

Results for the single GP and Dual-GP are shown in Fig. 4c and d, respectively, after 50 exploration steps. Again, the single GPBO fails to reconstruct the true function in the distorted subspace. In contrast, the 2nd GP in the Dual-GP again identified that the distorted space is x ∈ [0.3, 0.59], which is well aligned with the ground truth x ∈ [0.3, 0.6]. Subsequently, the Dual-GP workflow filtered out the acquired data from this subspace and constrained the exploration space to avoid sampling in this subspace. Through this approach, the Dual-GP effectively identifies valuable data, ensuring the primary GP focuses on high-quality spectra for more accurate and efficient optimization. A comparison of true function parameters predicted by the single GP and Dual-GP is shown in Fig. 4e–g, with Dual-GP demonstrating better estimations of all three parameters, suggesting the potential of Dual-GP with human assessment for accelerated and efficient optimization.

We further analyzed the run-to-run variability of the human-in-the-loop Dual-GP approach. The results across 10 runs with different seed measurement points are presented in Supplementary Information Figures S4–S6. The findings indicate that the human-in-the-loop Dual-GP converges to the ground truth more quickly. However, it exhibits greater variability compared to the Dual-GP approach that incorporates an observer function. This increased variability is likely due to the influence of subjective factors such as intuition, experience, and cognitive biases in human decision-making. In contrast, Dual-GP incorporated with an observer function is conducted without human intervention, which allows for higher consistency and lower variability.

Human-in-the-loop Dual-GP for real experimental data

After demonstrating the principle of Dual GP, we implemented this methodology in an autonomous PLD experiment data to assess its effectiveness for real-world application. The full details of the autonomous PLD experiment can be found in our previous work22. Briefly, WSe2 thin films of nominally monolayer thickness were grown by PLD using co-ablation of WSe2 and Se targets varying 4 growth parameters: pressure (P), substrate temperature (T), and laser energy on the WSe2 and Se targets E1 and E2, respectively. The scalarizer function used the Raman spectrum of each film after growth and calculated the ratio of the primary WSe2 E2g + A1g Raman peak height and width – a high “score” is achieved from intense, narrow peaks. Traditional GPBO was used to explore the 4D parameter space to maximize the Raman score using the expected improvement (EI) acquisition function. While this experiment was successful, the GPBO directed the synthesis of many films in regions of the parameter space that continually produced poor-quality samples. This is because a high dimensional space populated with only 10 s of samples results in high GP uncertainty and the BO tended to favor exploration. Because the growth window was narrow in at least 1 of the parameters, prolonged exploration led to numerous poor-quality samples. This effect is expected in traditional GPBO but when the maximum budget for total samples is small, as it is with PLD experiments, it is highly undesirable. Further, pure optimization is not always of interest to synthesis science. Experimentalists usually want to understand the synthesis response surface to determine the mechanisms of film growth. In this case, uncertainty-based acquisition is desired to achieve a representative GP surrogate, but human guidance is needed to prevent frivolous exploration.

In the Dual-GP PLD experiment, we used the final GP surrogate from the initial study to act as the “experimental ground truth” to evaluate the reconstruction error from uncertainty-based exploration (UE) using single GPBO, Dual-GP, and random sampling. The Raman scores for the whole parameter space are sampled from the “experimental ground truth”. For the quality score of raw data in Dual-GP, we constructed it by ranking 108 Raman spectra from the experiment to make an approximation with a GP. The human quality score is a 1–10 ranking based on experimentalist experience and, while naturally arbitrary, high rankings generally go to spectra where the main WSe2 peak (~250 cm−1) is stronger than the Si substrate peak (at 520.7 cm−1) and is narrow while low rankings are assigned to spectra with weak or broad peaks. Examples of the human quality score and corresponding, previously developed Raman “score” derived from a multiple Lorentzian peak fitting and background subtraction routine22 are shown in Fig. 5j–l. While the Raman “score” and human quality ranking are roughly proportional, using the human-in-the-loop approach with the Dual-GP bypasses the difficulties associated with developing a robust (and inflexible) curve fitting routine for the Raman data, which allows for rapid assessment and human-guidance of autonomous PLD experiments.

a, b The ground truth response surface projected into the P vs. T and E1 vs. E2 planes. c, d The Dual-GP reconstruction closely matches the ground truth. e, f Random sampling performs better than (g, h) pure uncertainty exploration with traditional GPBO. The points in each map represent sampled points, where the red color indicates a high score. The axes of each map are normalized. i The root mean squared error of ground truth reconstruction vs sample number for all three cases shows that human-in-the-loop Dual-GP quickly outperforms random sampling and traditional GPBO when using uncertainty-based exploration, which is attractive for synthesis science applications where pure optimization is not the goal of the experiment. Examples of the human score (ranking 1–10) are shown in j–l and compared with the original Raman score which was based on a more complicated peak-fitting model.

During the human-in-the-loop Dual-GP experiment, the quality score was sampled to train the 2nd GP. With UE, the primary GPBO selects the next point based on maximum uncertainty. For each scenario, the same 10 samples were used as seed points. In the Dual-GP case, the exploration is constrained in the subspace where the quality score is >7 for the first 50 steps and >5 after that to allow for increased exploration. This decrease of the quality score constraint after 50 steps was based on human opinion that the constraint should be relaxed. The human-in-the-loop approach allows for flexible and dynamic changes to the constraint, to guide the GPBO exploration/exploitation. The parameter space was discretized into 15 × 15 × 15 × 15 to have 50625 possible combinations of parameters. Each experiment was run for 200 steps, sampling 0.4% of the total space.

Figure 5a, b show the experimental ground truth of the Raman score response surface projected into the P vs. T and E1 vs. E2 planes, respectively. The Dual-GP reconstruction closely matches the ground truth and sampled the space efficiently to reduce the root mean squared error (RMSE) of reconstruction rapidly within the first 50 steps (Fig. 5i). Random sampling performed the next best, but still poorly reconstructs the ground truth. Lastly, traditional GPBO completely failed to reconstruct the ground truth with very little improvement in the RMSE over all 200 steps. The high uncertainty in the sparsely sampled space leads to many samples at the edges in the E1 vs E2 plane (Fig. 5h) and sampled the high-pressure region almost exclusively. When increasing the dimensionality of the parameter space, the surface area to volume ratio of the parameter hypercube scales like 2 N/L where N is the number of dimensions and L is the edge length. This results in uncertainty-based exploration being increasingly biased towards edge points as dimensionality increases. This could be mitigated in other ways such as including a decay function in the acquisition near the edges or by designing a different kernel. But here, the dual-GP approach that we present proves to be an effective, adaptive method to modify the acquisition function to both dimmish the influence of high uncertainty edge points, as well as focus exploration/exploitation in a region defined by a human-in-the-loop. The full evolution of the single and dual-GP mean, variance, and acquisition functions are available on Github. It should be noted that the goal of this synthesis simulation was not to locate the maximum as quickly as possible but rather to quickly build an effective surrogate model for the synthesis space with sparse sampling. The role of the human in this scenario is to assess the raw experimental data, this assessment can be used to dynamically adjust the feasible space while still allowing for uncertainty-based exploration. These results indicate that Dual-GP with human assessment can lead to more efficient optimization in experiments.

Discussion

In summary, we demonstrate that the Dual-GP approach represents an advancement in GPBO-driven autonomous experimentation, addressing a key limitation inherent to GPBO applications in real-world experiments. By introducing a 2nd GP to dynamically constrain the experimental space based on the observation of raw experimental results, the Dual-GP approach mitigates the shortcomings of traditional GPBO optimization and enhances the adaptability and accuracy of the optimization process. This approach effectively isolates more promising experimental spaces for BO sampling and improves the quality of obtained data. Furthermore, we also developed a strategy for human-in-the-loop Dual GP optimization, allowing experts to assess and adjust experiments, ensuring that unanticipated scenarios in real-world experiments are appropriately managed. It has also been shown that similar human-AI collaboration improves semiconductor process development efficiency45. The demonstrated application of the Dual-GP approach in both synthetic and real-world experimental settings indicates its potential in broad autonomous experiments across various domains. This work primarily focuses on function approximation to demonstrate the capability of Dual-GP, this focus allows us to leverage clear metrics (i.e., parameters of the corresponding functions) to effectively evaluate the performance of the developed method. However, it is noteworthy that function approximation can be a crucial process for uncovering physical laws and plays role in knowledge generation that can inform further materials optimization. Therefore, Dual-GP has great potential for application in various optimization problems within scientific research as well. For materials developments that are expensive, time-consuming, and difficult to automate, the Dual-GP approach is an effective technique to rapidly understand quantitative trends of material properties vs. experimental conditions in large parameter spaces with a minimal number of samples by effectively infusing human expertise into the autonomous workflow. The Dual-GP approach can also be used to incorporate on-the-fly experimentation in autonomous platforms, offline in-depth investigation, and theory, etc., enabling cross-facilities, asynchronous co-optimization for accelerated research46.

Methods

Synthetic data

The raw spectra shown in Figs. 3 and 4 are synthesized using a standard Gaussian function:

where A is the amplitude, µ is the mean, and σ is the standard deviation. Details of the spectra synthesis process can be found in the Python Notebooks available at https://github.com/yongtaoliu/dual-GP.git.

Gaussian Process Model

Gaussian process models and hypderparameter optimization were implemented with the GPax package (https://gpax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/.) GP hyperparameters were optimized on every iteration and is done automatically by GPax using stochastic variational inference with the evidence lower bound (ELBO) loss criterion. A Matérn kernel was used in all cases. The mean functions were structured using Eq. (1) for the studies described in Figs. 3, 4 while a constant (zero) mean was used for the PLD data experiments shown in Fig. 5.

Data availability

The data and code for this study are provided at https://github.com/yongtaoliu/dual-GP.git and https://github.com/sumner-harris/dual-GP-for-PLD. The approach is built using GPax https://gpax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/.

Code availability

The code for is study are provided at https://github.com/yongtaoliu/dual-GP.git and https://github.com/sumner-harris/dual-GP-for-PLD. The approach is built using GPax https://gpax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/.

References

Stach, E. et al. Autonomous experimentation systems for materials development: A community perspective. Matter 4, 2702–2726 (2021).

Greenhill, S., Rana, S., Gupta, S., Vellanki, P. & Venkatesh, S. Bayesian optimization for adaptive experimental design: a review. IEEE Access 8, 13937–13948 (2020).

Ziatdinov, M., Liu, Y., Kelley, K., Vasudevan, R. & Kalinin, S. V. Bayesian active learning for scanning probe microscopy: From Gaussian processes to hypothesis learning. ACS Nano 16, 13492–13512 (2022).

Liang, Q. et al. Benchmarking the performance of Bayesian optimization across multiple experimental materials science domains. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 188 (2021).

Lampe, C. et al. Rapid data-efficient optimization of perovskite nanocrystal syntheses through machine learning algorithm fusion. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208772 (2023).

MacLeod, B. P. et al. Self-driving laboratory for accelerated discovery of thin-film materials. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8867 (2020).

Epps, R. W. et al. Artificial chemist: an autonomous quantum dot synthesis bot. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001626 (2020).

Frean, M. & Boyle, P. In AI 2008: Advances in Artificial Intelligence. (eds W. Wobcke & M. Zhang) 258-267 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg).

Noack, M. M. et al. Autonomous materials discovery driven by Gaussian process regression with inhomogeneous measurement noise and anisotropic kernels. Sci. Rep. 10, 17663 (2020).

Noack, M. M. et al. Gaussian processes for autonomous data acquisition at large-scale synchrotron and neutron facilities. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 685–697 (2021).

Jones, D. R. A. Taxonomy of global optimization methods based on response surfaces. J. Glob. Optim. 21, 345–383 (2001).

Yamashita, T. et al. Crystal structure prediction accelerated by Bayesian optimization. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 013803 (2018).

Ueno, T., Rhone, T. D., Hou, Z., Mizoguchi, T. & Tsuda, K. COMBO: An efficient Bayesian optimization library for materials science. Mater. Discov. 4, 18–21 (2016).

Tran, A., Tranchida, J., Wildey, T. & Thompson, A. P. Multi-fidelity machine-learning with uncertainty quantification and Bayesian optimization for materials design: Application to ternary random alloys. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 074705 (2020).

Gómez-Bombarelli, R. et al. Automatic chemical design using a data-driven continuous representation of molecules. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 268–276 (2018).

Pyzer-Knapp, E. O. Bayesian optimization for accelerated drug discovery. IBM J. Res. Dev. 62, 2:1–2:7 (2018).

Chang, J. et al. Efficient closed-loop maximization of carbon nanotube growth rate using Bayesian optimization. Sci. Rep. 10, 9040 (2020).

Rao, R. et al. Advanced machine learning decision policies for diameter control of carbon nanotubes. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 157 (2021).

Park, C., Rao, R., Nikolaev, P. & Maruyama, B. Gaussian Process Surrogate Modeling Under Control Uncertainties for Yield Prediction of Carbon Nanotube Production Processes. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 144 https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4051915 (2021).

Shields, B. J. et al. Bayesian reaction optimization as a tool for chemical synthesis. Nature 590, 89–96 (2021).

Deringer, V. L. et al. Gaussian process regression for materials and molecules. Chem. Rev. 121, 10073–10141 (2021).

Harris, S. B. et al. Autonomous synthesis of thin film materials with pulsed laser deposition enabled by in situ spectroscopy and automation. Small Methods 8, 2301763 (2024).

Shimizu, R., Kobayashi, S., Watanabe, Y., Ando, Y. & Hitosugi, T. Autonomous materials synthesis by machine learning and robotics. APL Mater. 8, 111110 (2020).

Fébba, D. M. et al. Autonomous sputter synthesis of thin film nitrides with composition controlled by Bayesian optimization of optical plasma emission. APL Mater. 11, 071119 (2023).

Deneault, J. R. et al. Toward autonomous additive manufacturing: Bayesian optimization on a 3D printer. MRS Bull. 46, 566–575 (2021).

Gongora, A. E. et al. A Bayesian experimental autonomous researcher for mechanical design. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz1708 (2020).

Snapp, K. L. et al. Autonomous Discovery of Tough Structures (arXiv:2308.02315, 2023).

Sattari, K. et al. Physics Constrained Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization to Accelerate 3D Printing of Thermoplastics (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental discovery of structure-property relationships in ferroelectric materials via active learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 341–350 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Automated experiments of local non-linear behavior in ferroelectric materials. Small 18, 2204130 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Exploring the relationship of microstructure and conductivity in metal halide perovskites via active learning-driven automated scanning Probe Microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 3352–3359 (2023).

Thomas, J. C. et al. Autonomous scanning probe microscopy investigations over WS2 and Au{111}. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 99 (2022).

Narasimha, G., Hus, S., Biswas, A., Vasudevan, R. & Ziatdinov, M. Autonomous convergence of STM control parameters using Bayesian optimization. APL Mach. Learn. 2, 016121 (2024).

Roccapriore, K. M., Kalinin, S. V. & Ziatdinov, M. Physics discovery in nanoplasmonic systems via autonomous experiments in scanning transmission electron Microscopy. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203422 (2022).

Sanchez, S. L. et al. Physics-driven discovery and bandgap engineering of hybrid perovskites. Digit. Discov. 3, 1577–1590 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Learning the right channel in multimodal imaging: automated experiment in piezoresponse force microscopy. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 34 (2023).

Liu, Y., Ziatdinov, M. A., Vasudevan, R. K. & Kalinin, S. V. Explainability and human intervention in autonomous scanning probe microscopy. Patterns 4, 100858 (2023).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Hsu, H.-P., Li, L.-C., Shellaiah, M. & Sun, K. W. Structural, photophysical, and electronic properties of CH3NH3PbCl3 single crystals. Sci. Rep. 9, 13311 (2019).

Du, K.-Z. et al. Two-dimensional lead (II) halide-based hybrid perovskites templated by acene alkylamines: crystal structures, optical properties, and piezoelectricity. Inorg. Chem. 56, 9291–9302 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Highly efficient white-light emission in a polar two-dimensional hybrid perovskite. Chem. Commun. 54, 4053–4056 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Novel〈 110∟-oriented organic-inorganic perovskite compound stabilized by N-(3-Aminopropyl) imidazole with improved optical properties. Chem. Mater. 18, 3463–3469 (2006).

Zhu, L.-L. et al. Stereochemically active lead chloride enantiomers mediated by homochiral organic cation. Polyhedron 158, 445–448 (2019).

Ziatdinov, M. A., Ghosh, A. & Kalinin, S. V. Physics makes the difference: Bayesian optimization and active learning via augmented Gaussian process. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 3, 015003 (2022).

Kanarik, K. J. et al. Human–machine collaboration for improving semiconductor process development. Nature 616, 707–711 (2023).

Strieth-Kalthoff, F. et al. Delocalized, asynchronous, closed-loop discovery of organic laser emitters. Science 384, eadk9227 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences (CNMS), which is a US Department of Energy, Office of Science User Facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. conceived the idea. Y.L. performed the investigation. S.H. performed the PLD experiment and data analysis. Y.L. and S.H. wrote the manuscript, and R.V. edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, S.B., Vasudevan, R. & Liu, Y. Active oversight and quality control in standard Bayesian optimization for autonomous experiments. npj Comput Mater 11, 23 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01485-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01485-2