Abstract

We introduce and discuss a method for global optimization of atomic structures based on the introduction of additional degrees of freedom describing: 1) the chemical identities of the atoms, 2) the degree of existence of the atoms, and 3) their positions in a higher-dimensional space (4-6 dimensions). The new degrees of freedom are incorporated in a machine-learning model through a vectorial fingerprint trained using density functional theory energies and forces. The method is shown to enhance global optimization of atomic structures by circumvention of energy barriers otherwise encountered in the conventional energy landscape. The method is applied to clusters as well as to periodic systems with simultaneous optimization of atomic coordinates and unit cell vectors. Finally, we use the method to determine the possible structures of a dual atom catalyst consisting of a Fe-Co pair embedded in nitrogen-doped graphene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The design and discovery of new materials and nanoparticles with particular physical or chemical properties have recently seen major improvements due to the introduction of machine-learning approaches. In many cases, the main advantage is the replacement of time-consuming density functional theory (DFT) calculations with much faster predictions of properties based on machine-learning techniques, for example tree methods1, kernel regression2,3,4, and neural networks5,6,7,8,9.

The development has included the construction of new interatomic potentials based on Gaussian processes2,10 or using equivariant neural networks11,12,13. It has even been shown possible to construct “universal” interatomic potentials that work not only for particular systems but for a broad class of materials with different chemical compositions14,15.

The replacement of DFT with much faster machine-learning calculations is of utmost importance in many applications such as molecular dynamics simulations. However, machine-learning and probabilistic approaches can also contribute in new, more fundamental ways for materials design beyond the mere speed-up of calculations. One example of this is the recently developed generative models where suggestions for new, stable materials are predicted based on training of neural networks on databases of known materials16,17,18,19,20.

The work presented here is in the category where machine learning fundamentally expands on the available approaches to a given problem. The topic we address is the global optimization of atomic structures, and we will demonstrate how introducing new variables, implemented within an atomic fingerprint, enhances optimization efficiency.

The structure of a material, i.e. the positions of the constituent atoms, does to a large extent determine its properties. A material may exhibit several different atomic structures, but at low temperatures, the structures with the lowest potential energies will dominate, and it is therefore of key importance to identify such structures. The main challenge in doing so comes from the fact that typical potential energy surfaces (PESs) are high-dimensional and exhibit many local minima, which are separated by energy barriers, and which have to be explored to find the ones with the lowest energies. Machine-learning the PES may help considerably by speeding up the calculation of the energy and the forces on the atoms, but still the challenge of exploring the atomic configuration space remains.

Many methods for exploring the PES have been devised. One such method is random sampling in which sensible random structures are constructed according to physically valid unit cell sizes, atomic distances, symmetries etc. and subsequently relaxed by means of DFT or machine learning methods21,22. The generation of sensible structures has likewise been addressed by genetic algorithms23,24,25,26. The dynamical crossing of energy barriers is addressed in basin hopping27, minima hopping28, simulated annealing29,30,31, meta-dynamics32, and particle swarm algorithms33,34. Both challenges have been sought solved by either pre-relaxing or intermittently relaxing structures in complementary energy landscapes35,36,37. Yet other methods seek to bias the PES itself towards systems of higher symmetry and desirability38.

Recently, machine-learned PESs have been combined with Bayesian search strategies leading to considerable improvement of the search efficiency. The PESs are modelled by Gaussian processes, where predicted energies and their uncertainties guide the further model construction10,39,40. Likewise, neural networks have been used for PES prediction in uncertainty-guided active learning via the query-by-committee ensemble approach.8,41,42

In the present work, we shall demonstrate how the extension of the atomic configuration space with new degrees of freedom can lead to efficient barrier circumvention and fast structure determination when combined with Bayesian search in a Gaussian process framework. Extra dimensions are introduced using a fingerprint and they describe 1) the chemical identity of the atoms allowing for interpolation between chemical elements (“ICE”); 2) the degree of existence of an atom allowing for interpolation between ordinary atoms and vacuum (“ghost” atoms); and 3) the positions of the atoms in a higher dimensional space of 4-6 dimensions (“hyperspace”). Some of the ideas behind these additional degrees of freedom have been recently discussed. Some of the present authors introduced ICE43 and ghost atoms44, while the hyperspatial coordinates were discussed by Pickard for clusters with a predefined analytical potential45. The present work distinguishes itself from the earlier work with four main contributions: Firstly, we formulate a fingerprint generalizing the distance and angle-distribution of the fingerprint used in ref. 40 to arbitrarily many spatial dimensions. This allows for the description of hyperspatial atomic structures not only for analytic potentials as in ref. 45 but with DFT precision through a Gaussian process based surrogate model. Secondly, we extend the methods described in refs. 43 and 44 to arbitrarily many elements. Thirdly, we develop a framework that allows for the simultaneous use of ICE, ghost, and hyperspatial coordinates, and lastly, we implement the calculation of stresses allowing for simultaneous optimization of periodic unit cells. We note that even though the description involves hyperspatial coordinates and fractional atoms, the training and the finally predicted atomic structures always represent real physical systems. Furthermore, the Gaussian processes are trained using both energies and forces to efficiently use the data from DFT calculations similar to the work in refs. 40,43,44.

Results

In the following, we shall present a brief overview of the methodology developed here. We first describe the introduction of the additional degrees of freedom in the representation of the atomic structure. We then show how the representation is used in a Bayesian search loop for global structure optimization as proposed in the GOFEE approach39, and also implemented in the BEACON code40 before we present the results. Most of the methodology is described in the Methods section.

Structure representation

The training of a machine to predict the energy and forces of atoms as a function of the atomic positions requires a representation of the atomic structure to the machine. Except for the now rather popular, equivariant graph neural networks11,12,13, this is usually done with a vectorial fingerprint, which explicitly implements the translational, rotational, and permutational symmetries of the system2,3,46,47,48,49,50,51 as recently extensively reviewed by Musil et al.52. The choice of the atomic structure representation may often be regarded as a technicality, but in our case this choice is at the heart of the method, which is also why we describe it here up front.

An atom is usually described by its chemical identity and its position as given by three spatial coordinates. We are now generalizing this description in two ways. First, we extend the coordinates of (say atom i) xi to arbitrarily many dimensions. We shall take the first three components to describe the usual space, when the coordinates of the higher dimensions vanish. Secondly, we introduce for each atom, i, a variable, qi,e, which represents the degree to which this atom exists with the chemical element e. Whereas the normal and extra spatial coordinates can take any real values, the elemental coordinates, qi,e, are restricted to the interval qi,e ∈ [0, 1] with 0 and 1 representing atom i being respectively zero and a hundred percent element e. The sum across all atoms for any given element, e, is equal to a constant, ∑iqi,e = Ne, conserving the total amount of each element for all atoms. Likewise, the atomic existence, qi, of atom i is calculated as the sum over all chemical elements qi = ∑eqi,e and is a number between 0 and 1, qi ∈ [0, 1].

Figure 1 illustrates different situations for an atomic system represented by its spatial and elemental coordinates. The simple situation, where all the elemental coordinates are either 0 or 1 so that only the spatial coordinates enter the description, is depicted in Fig. 1a).

The first yellow-green block illustrates the usual three-dimensional coordinates, while the second red-blue block represents the extra 4th and 5th dimensions. The elemental coordinates are represented by the third block. a The elemental coordinates are all 0 and 1, so there are no ICE-groups or ghost atoms. b The elements (Al, Cu, Ag) and (Au, Ni) constitute two separate ICE-groups of fractional elements, while Pd and Pt are not part of any ICE-group. c There is no interpolation between chemical elements, but five ghost atoms have been added: two Al atoms, two Cu atoms, and one Pd atom. d There are two ICE-groups. The (Al, Cu, Ag) ICE-group has four ghost atoms, while the (Au, Ni) ICE-group has no ghost atoms. Pd has a single ghost atom, but is not in an ICE-group.

Atoms, which are allowed to have fractional values of a subset of elements, will be able to interpolate between these elements, and we shall refer to such an elemental subset as an ICE-group, and the atoms belonging to this group are called its atomic members. It is possible to define several independent ICE-groups each containing arbitrarily many elements as long as the ICE-groups do not overlap, meaning that no atom will be a member of two separate ICE-groups. Figure 1b) illustrates the situation with two ICE-groups. One of them has seven atomic members and interpolates between Al, Cu, and Ag, while the other group has four members and interpolates between Au and Ni. The two Pd and Pt atoms do not participate in any ICE-group.

It is possible to include a number, \({N}_{{e}_{Ghost}}\), of additional “ghost” atoms for a particular element e, and in such a case the existence variable qi = ∑eqi,e for an atom can be fractional. For atoms of a certain element e not belonging to an ICE-group, excess atoms of element e would allow interpolation in existence space in such a way that the total elemental quantity Ne would still be conserved. This is illustrated in Fig. 1c), where five ghost atoms have been added to the system: two Al atoms, two Cu atoms, and one Pd atom. As atoms of low to no existence still exist in the atoms object but without interaction with the other atoms, we refer to such atoms as ghost-atoms, and an element, which may have ghost atoms, will be referred to as a ghost-possessing element.

As an atomic member of an ICE-group cannot be identified with any specific element, the inclusion of any ghost-possessing element in an ICE-group will allow all atoms of the ICE-group to become of fractional existence, hence allowing existence interpolation with any other atomic member of the ICE-group while still conserving the elemental sum Ne for any element e. This is illustrated in Fig. 1d), where the (Al, Cu, Ag) ICE-group now has four additional ghost atoms, the (Au, Ni) ICE-group has no ghost atoms, and finally there are two Pd atoms, where one of them is a ghost atom.

If we consider a system with Ne atoms of element e and label a given ICE-group with subscript α, the ICE-group may contain a number of ghost atoms \({N}_{{\alpha }_{Ghost}}\). We can regard atoms not belonging to an ICE-group as members of single-element ICE-groups. If an atom i and an element e do not belong to the same ICE-group, we have qi,e = 0. We have the following constraints

It follows that for a given ICE-group α, we have ∑i∈αqi = ∑e∈αNe. Therefore, if the ICE-group α does not contain any ghost atoms (\({N}_{{\alpha }_{Ghost}}=0\)), we have qi = 1 for all atoms i in the group. This just expresses that if the ICE-group does not contain ghosts, all atoms have complete existence.

The structural dimensions, i.e., the 3–6 spatial dimensions and the elemental coordinates, are incorporated in a fingerprint, which is used to predict energies and their derivatives through a Gaussian process trained on DFT data. The fingerprint consists of a radial and an angular part, which are both described in detail in the Methods section. However, here we shall briefly discuss the principle behind the inclusion of hyperspatial and elemental coordinates in the radial part as it illustrates how the additional degrees of freedom enable circumvention of energy barriers.

Fingerprint

The radial fingerprint, ρR, is essentially the radial distribution function weighted by the elemental coordinates, so for two chemical elements A and B, it takes the form

where r is the radial distance, rij is the distance between atom i and atom j, fc is a cutoff function limiting the sum to nearby atoms, and g is a Gaussian function. We first note that this definition can be immediately generalized to higher dimensions, since it only depends on the distances that are straightforwardly defined in higher dimensions. Secondly, a given bond between two atoms i and j receives a weight given by the product of the elemental variables, with qi,A and qj,B describing the fraction of element A in atom i and of element B in atom j respectively. This particular construction allows the “flow” of chemical element identity and existence over long distances without energy barriers. If two atoms are in identical atomic environments, but further apart from each other than the cutoff radius, they can exchange chemical identities with completely no change in the fingerprint and therefore without any energy barrier. The same situation applies if a ghost atom and a real atom exchange existence. This “free-flow” property is an essential feature of the fingerprint, and we show it in more detail in the Methods Section.

In a real application, the surroundings of the atoms will of course not in general be identical, and the fingerprint will vary between initial and final configurations of, say, a process where two atoms with different chemical elements exchange chemical identity. However, the variation of the fingerprint – if the atoms are far apart – will be linear in the fractional variables, and in practice, this leads to small or no energy barriers.

Bayesian search algorithm

The fingerprint and a Gaussian process (GP) trained on DFT energies and forces form the basis for our global structure determination. The procedure is similar to the one in GOFEE39 and BEACON40, but with additional facets because of the more general structure representation. The details of the approach are defined in the Methods section, so here we only give a brief overview before we turn to the results.

For a given atomic system, the optimization process is initiated by generating a set (we use two) random configurations of the system (upper part of Fig. 2). These configurations are all physical with spatial coordinates in three dimensions, i.e. all hyperspatial coordinates set to zero, and with all elemental coordinates being zero or one. DFT calculations for these systems can therefore be performed, and the resulting energies and forces are saved in a database, which we simply call the DFT database.

a Illustration of the Bayesian search algorithm inspired by the one in GOFEE39 and as implemented in BEACON40 emphasizing how the total number of atoms, NAtoms, and spatial dimensions, DAtoms, vary during the runs. Structures included in the training set always contain a total of NReal atoms of unit element identity embedded in the usual three dimensional space. Random structures for surrogate relaxation contain a total of NReal physical atoms and NGhost extra atoms, all with fractional existence and chemical identity, embedded in a space extended with DHyper extra spatial dimensions. The atoms in (a) are color-coded according to the insets (b–d) describing elemental coordinates of elements A and B and hyperspatial coordinates, respectively.

After this, a loop begins with the training of a GP on the DFT database using the fingerprint. The GP is thus trained on “real” systems, but because of the way the fingerprint is defined, it can provide predictions of energies and derivatives also for hyperspatial coordinates and fractional elemental coordinates. The loop proceeds by generating a number of new random configurations (we use forty). These configurations are allowed to contain fractional elemental coordinates and also coordinates in hyperspace fulfilling the constraints (i.e., spatial dimension, number of ghost atoms etc.) defined for this particular simulation. These configurations are then locally optimized using the GP to obtain a set of minimum-energy configurations of the GP potential (right part of Fig. 2). During these optimizations, the hyperspace coordinates are increasingly penalized. If the final configurations contain fractional elemental coordinates, they are rounded to zero or one so that the prescribed number of real atoms is obtained (lower right part of Fig. 2). At this stage undesired structures may be discarded, e.g. structures already included in the database. The remaining set of minimum-energy structures is then evaluated by a lower-confidence-bound acquisition function, which takes into account both the predicted energies and uncertainties from the GP. The configuration with the lowest value of the acquisition function is then evaluated with DFT and included in the DFT database, and the loop can continue. The algorithm is terminated after a fixed number of DFT calculations, and the lowest energy structure in the DFT database is then considered the best candidate for the ground state. Several independent runs are carried out to obtain statistical information on the performance of the algorithm.

Illustrations of barrier circumvention

We will now show some simple examples of how the fingerprint enables the circumvention of energy barriers. The Bayesian search algorithm is not applied here, but we only consider processes with a given Gaussian process (GP) potential. We use the effective-medium theory (EMT)53,54 to describe the interatomic interactions. A GP based on the fingerprint is trained on energies from a database of systems calculated with EMT. The GP is trained on real, physical configurations, i.e. all atoms are in three-dimensional space and the elemental variables are zero or one. However, once the GP is trained, it can predict energies and derivatives for any value of the fingerprint, and it therefore provides an interpolation to situations with atoms in hyperspace and with fractional elemental coordinates.

The expansion of space into higher dimensions allows for processes where atoms may pass each other with lower or no energy barriers45. Figure 3a shows a process for a 13-atom copper cluster. In the initial configuration, an atom is located on the outside of the cluster, which has a hole in its center. The atom is then pulled to the center of the cluster. In three dimensions the process necessarily involves pushing some of the atoms away from their low energy positions leading to an energy barrier of about 1 eV (as determined with the nudged-elastic-band method55,56). In four dimensions, the atom, which is pulled to the center, can move out into the fourth dimension keeping a proper bonding distance to the nearby atoms. The barrier is therefore removed. The degree to which the atom is moving into the fourth dimension is visualised by the color of the atom in the figure.

a An atom on the outside of a Cu12-shell is moved to the inside in three and four dimensions with the blue shading of the atom indicating its extension into the fourth dimension. The barrier disappears in four dimensions. b An atom is moved to a vacant hollow site of a Cu13 cluster by following a path crossing three bridge sites or by exchanging existence with a ghost atom residing at the hollow site. Atomic radius indicates existence. c An exchange process of a Cu and an Au atom in an alloy. The energy barrier is removed by a gradual change of the chemical identity of the involved atoms indicated by the atomic colors. In all cases, the energies calculated with the Gaussian process are very close to the target effective-medium theory energies (the blue lines).

Another process for a Cu13 cluster is considered in Fig. 3b. In the initial configuration, an atom is placed at the lower left side of the cluster, while in the final state, the atom is positioned at an energetically more favorable position on top of the cluster so that a symmetric configuration with a central atom surrounded by a shell of twelve atoms is obtained. The lowest-energy path between the initial and the final state involves moving the atom along the side of the cluster resulting in three energy barriers along the way. (The path is determined with the nudged-elastic-band method55,56). Alternatively, the atom can be moved with a ghost process. In that case, the initial state has the real atom at the lower left and a ghost atom positioned at the top position. In the figure, the degree of existence is indicated in the lower row of atomic configurations by the size of the atom. During the ghost process, the initial atom disappears while the ghost atom increases in existence until the atom has effectively completely moved. We saw above that if the surroundings of the two atoms are identical there would be no energy change. In the present case, the two surroundings are different, and the energy is seen to monotonically decrease from the initial to the final value without a barrier.

Barriers for exchanging atoms can also be circumvented through interpolation between the chemical elements. This is illustrated in the case of a CuAu-alloy in Fig. 3c. In the initial configuration, a copper and a gold atom have been interchanged relative to the lowest energy configuration, which is also the final state. The configuration path for the exchange process in physical space can be determined with the nudged-elastic-band technique. It involves a large energy barrier because it is difficult for the atoms to get around each other in the closely packed crystal as shown in the upper row of configurations in the figure. Introducing the elemental coordinates in the fingerprint allows for an alternative process in which the two atoms stay at the initial positions but gradually change their chemical identity. This leads to a process, where the high energy barrier is removed.

Example of surrogate relaxation

The fingerprint and the GP allow for simultaneous variation of all spatial and elemental coordinates at the same time. This is illustrated in Fig. 4 for a Cu18Ni5 cluster with 11 ghost atoms in four dimensions. The figure shows the result of an energy minimization from a random initial structure. The final configuration (for this initial structure) is the globally optimal one for the cluster. The relaxation is from the sixth iteration of a global optimization run as illustrated in Fig. 2, and the GP thus trained on seven configurations of the cluster as calculated with DFT, two random structures and five discovered local minimum structures. During the energy minimization the fourth dimension is increasingly penalized (Fig. 4d) to ensure that in the final structure all atoms are in 3D space. The penalization is the reason for the small upward steps in the energy curve (Fig. 4c). During the minimization, all spatial and elemental coordinates are simultaneously optimized. Due to the penalization of the fourth dimension the 4D coordinates gradually disappear (panel e). The elemental fractions (panels f, g) and the existence variable for each atom (panel h) are initially distributed in the interval between 0 and 1 but spontaneously converge towards integer values during the minimization so that the final configuration contains 18 Cu atoms, 5 Ni atoms, and 11 ghost atoms without existence. The motion of the atoms and the variation of the elemental variables are visualized in the snapshots in the two upper panels a and b.

a Snapshots of the atomic structure at relaxation steps 0, 50, 100, 150, 200, and by the end of the relaxation. Atoms are colored according to their fractional composition of copper and nickel with copper being brown and nickel being green. The atomic radius reflects the existence of the atoms with all atoms having roughly the same radius at full existence. b Same as (a) but with the coloring reflecting the distance into the fourth dimension. Grey indicates an atom embedded exclusively in the three dimensional space while the intensity of red and blue indicate the extension into the fourth dimension in the positive and negative direction, respectively. The remaining plots depict a function of relaxation steps: (c) The GP calculated energy, (d) the hyperspatial penalty constant, (e) the atomic extension into the fourth dimension, (f) the elemental coordinate of Cu, (g) the elemental coordinate of Ni, (h) the overall atomic existence. The differently colored lines in (e–h) represents the coordinates of the individual atoms.

Global optimization examples: overview

The following sections present a number of applications using the Bayesian search algorithm illustrated in Fig. 2. For each system, a number of 20 independent optimization runs are performed, and the statistical performance is shown using so-called success curves. A success curve shows the fraction of successful runs after a given number of DFT calculations, where success is declared if the ground state has been identified. In some cases, the ground state is known from other work, but in general we of course cannot prove that the true ground state has been determined. Therefore, we use the lowest-energy state identified in all runs as the ground state. In the following analysis, standard BEACON or simply BEACON refers to optimization runs without hyperspatial or elemental coordinates, serving as a baseline. The new methods are: ICE (interpolation of chemical elements), Ghost (ghost atoms) and 4D, 5D, 6D (hyperspatial optimizations in four, five and six dimensions, with 3D equivalent to BEACON).

Global optimiziation examples: hyperspatial coordinates

We first consider the copper clusters Cu38 and Cu55. Copper clusters are of interest within heterogeneous catalysis, and their properties have been addressed both experimentally and theoretically57,58,59,60,61,62.

Figure 5a, b shows the success curves for Cu38 and Cu55, where the simulations have been performed with standard BEACON in three dimensions and with hyperspatial extensions to four or five dimensions. For Cu38 the ground state is an fcc-like truncated octahedron. This is in agreement with previous studies57,58,60,61. One study also identifies an energetically nearly degenerate incomplete-Mackay-icosahedron structure60. The global minimum is seen to be found only once out of twenty attempts within 100 DFT calculations using standard BEACON, whereas it is found in half the cases when optimizing in four and five dimensions.

Success curves for global optimization runs without (3D) and with hyperspatial extension (4D, 5D, 6D) of (a) Cu38 cluster, (b) Cu55 cluster, (c) Cu18Ni5 cluster, (d) Ag12S6 cluster, (e) Ta6O15 cluster, (f) Ni15Al5 bulk system. The insets show the identified minimum-energy structures. All success curves include 20 independent runs with 40 surrogate relaxations in each iteration. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

The Cu55 ground-state structure is a well-known “magic” Mackay icosahedron. It is identified in eight of the twenty runs with standard BEACON, but is very easy to find using four or five dimensions, where only of the order 20 DFT calculations are needed (see, Fig. 5b). The fast identification is probably because of the high symmetry, which also means that competing structures are considerably higher in energy.

The improvement obtained by the hyperspatial degrees of freedom can also be seen for alloy clusters. Figure 5c shows the success curves in three to six dimensions for a Cu18Ni5 cluster. In this case, standard BEACON fails to identify the ground state structure, while optimizations with additional spatial dimensions have more success. Even though the number of atoms is lower than in the Cu38-cluster, the fact that there are two different elements gives rise to an additional combinatorial complication, making the problem hard. The convergence to the ground state is particularly fast if two or three dimensions are added in which case the ground state is identified in more than half of the runs in less than 30 DFT calculations.

The extra spatial dimensions do not always lead to an improvement in the global search algorithm. Figure 5d shows the success curves for the small binary cluster Ag12S6, where the search in 4D space is in fact less successful than the usual 3D search for a range of DFT calculations. We do not have a simple explanation for this behavior except that the cluster is fairly small, and the usual BEACON optimization therefore already is quite successful. Another point may be that an N-dimensional structure projected onto (N-1)-dimensional space appears more compact than an intrinsic (N-1)-dimensional structure with similar bond lengths. Thus, forming non-compact or hollow structures in 3D from a 4D space may be challenging, potentially disadvantaging the formation of the silver core hole in Ag12S6 during 4D optimization. The success curves for a Ta6O15-cluster, which was also treated in ref. 40, are shown in the Fig. 5e. This also relatively small non-compact cluster is likewise well handled by standard BEACON, and the extra dimensions slightly worsen the search.

A main feature of the present implementation of the global search algorithm is the ability to treat periodic systems with a variable unit cell. The fingerprint is defined through sums over local atomic surroundings and can therefore be straightforwardly implemented also for periodic systems, and a surrogate potential energy surface can be constructed based on the Gaussian process. The derivatives of the surrogate potential energy can be calculated not only for the spatial and elemental coordinates of the atoms but also for the unit cell vectors. In this way, the stress can be calculated and used in structure optimization.

Figure 5f shows the result of a global optimization of a Ni15Al5 system with variable unit cell. The well-known Ni3Al - L12-structure is identified with both standard BEACON and with hyperspatial extension. The optimization is fairly challenging in the sense that the number of atoms, which is five times the number in the primitive unit cell, requires a unit cell, which is not close to the cubic one. The extra hyperdimension is seen to considerably improve the search efficiency.

The effect of the extra dimension is further analyzed in Fig. 6, which shows the distribution of all calculated DFT energies during global optimizations of Cu18Ni5. The figure shows a clear shift to lower energies for the simulations in four, five and six dimensions relative to three dimensions. Figure 6 also indicates that going beyond five dimensions doesn’t provide any further improvement in agreement with Fig. 5c.

To conclude this section about the hyperspace approach, we note again that the extra dimensions make it possible to circumvent energy barriers in lower dimensions. Another factor possibly affecting the performance of the approach is that atoms in higher dimensions often have considerably more neighbors than in lower dimensions. One way to see this is through the so-called kissing number, which is the highest number of hyperspheres, which can touch an equivalent hypersphere without overlap. The kissing number increases substantially with dimension being for dimensions one to six: 2, 6, 12, 24, 40, and 72, respectively63. Noble metal clusters – if not very small – tend to form close-packed structures resembling the ones they take on in their bulk form. It is therefore conceivable that the possibility of forming more compact structures in higher dimensions also provides an advantage in the search for the global optimum structure in three dimensions when the ground state is compact. One unfortunate consequence of the high number of neighboring atoms in higher dimensions is that the fingerprint becomes more time consuming to calculate, especially for periodic bulk systems.

Global optimization examples: elemental coordinates

We now leave aside the hyperspace approach and consider the elemental coordinates together with the usual 3D spatial coordinates. We shall then afterwards discuss combinations of hyperspatial and elemental coordinates. For a start, we also do not consider any ghost atoms, so the elemental coordinates describe only the fraction of the different chemical elements present in each atom.

Crystalline metal alloys in either cluster or bulk form typically exhibit a very large number of meta-stable states. The swapping of two atoms of different chemical elements in a local (meta-)stable structure often leads to a new atomic configuration, which itself is at or close to a local minimum of the potential energy surface. The number of meta-stable states therefore grows very rapidly with the number of atoms present in a cluster or in a unit cell of a periodic crystal. The ICE-technique with interpolation between the chemical elements was introduced in ref. 43, but here we shall consider the approach in more detail with more analysis of its properties. We note that the performance of individual systems may depend rather sensitively on the particular choice of parameters, so our focus will be on trends and comparisons between the different methods for a fixed set of algorithm parameters.

The present approach allows for the definition of multiple ICE-groups, and it is, therefore, relevant to ask in which situations and for which types of atoms it is advantageous to combine them into ICE-groups. The spatial and elemental coordinates can be simultaneously optimized in a relaxation on the surrogate potential energy surface so that while an atom is gradually changing its chemical identity, the local environment can also spatially relax. However, it still seems reasonable to suggest that it might be better to put atoms, which are chemically similar, into the same ICE-group than atoms, which are very different. We investigate this further in Fig. 7 by showing the success curves for four binary systems, with the size of atoms being quantified by the covalent radii. We consider CuAu, where the covalent radii are rCu = 1.32 Å and rAu = 1.36 Å, MgPt (rMg = 1.41 Å, rPt=1.36), YZn (rY = 1.90, rZn = 1.22 eV) and TiS (rTi = 1.60, rS = 1.05). In these runs a fixed cell corresponding to the optimal structure from OQMD64 is used. As can be seen from the figure, the use of ICE considerably speeds up the identification of the lowest-energy structures for CuAu being a combination of two similar sized transition metals and for MgPt being a combination of a transition metal and an alkaline earth metal of similar size.

All systems have 16 atoms in the unit cell. a–d The identified minimum-energy structures. e Success curves for optimization of the four systems. “ICE” refers to runs where the relevant atoms are part of an ICE-group, while “BEACON” refers to runs without any ICE-groups. The applied unit cells corresponding to the optimal structures from OQMD64. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

The two elements in the YZn-system are both transition metals, which in their pure standard states exhibit a hexagonal close-packed structure, and they are therefore in that sense fairly similar despite the difference in atomic size. The situation is quite different in the case of TiS. Here, we have a transition metal combined with a chalcogen — two very different kinds of atoms with opposite charge states. Whereas ICE is seen to considerably speeds up the identification of the lowest-energy structure of YZn, it provides little to no advantage for TiS. We can thus conclude that for the systems studied here, the mere size of the constituent atoms of an ICE-group does not play a role in the efficiency, but the chemical character seems to be of importance.

To further back up this conclusion we consider the system NbNO containing two “types” of elements. We would expect the N and O gas atoms to be fairly similar while the metal atom Nb to be different from the other two elements. We would thus expect the search where N and O are included in an ICE-group, while Nb is outside the group, to be the most efficient. This is exactly what is seen in Fig. 8 with success curves for a 24-atom fixed unit cell. A search using an ICE-group consisting of all three elements does also find the ground state, but with slightly more difficulty. If we define an ICE-group of Nb and O, or use standard BEACON the ground state is not discovered at all within 100 DFT calculations.

Success curves for optimization of Nb8N8O8 from runs including ICE-groups containing NbNO (ICE Nb,N,O), NO (ICE N,O), NbO (ICE Nb,O), or no ICE-groups (BEACON). The inset shows the identified minimum-energy structure. The applied unit cell corresponding to the optimal structure from OQMD64. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

The new formulation of the ICE method also allows for simultaneous optimization of the unit cell. We start by considering the effect of varying the number of atoms in the unit cell. Figure 9 shows the success curves for bulk Ni3Al systems with 8, 16, or 32 atoms in the unit cell. As expected, it becomes considerably harder to find the ground state structure as the number of atoms increases. In particular for Ni24Al8, standard BEACON(dashed curves in the figure) does not find the right structure in any of the 20 runs within 100 DFT calculations each. The ground state is identified with ICE in very few DFT calculations for 8 or 16 atoms in the unit cell, while the 32-atom cell requires up to 60 DFT calculations.

a–c The identified minimum-energy structures. d Success curves for optimization of the three systems. “ICE” refers to runs where the relevant atoms are part of an ICE-group, while “BEACON” refers to runs without any ICE-groups. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

We continue the analysis of optimization of systems with varying unit cells by considering application of either the ICE or ghost method, but not at the same time. Figure 10 shows success curves for the systems NiAl3, NiPt2Al, and NiPtZnAl. All systems have 16 atoms in the unit cell, and the ICE group includes all elements. In the ghost runs, 50% of the number of each element has been added as ghost atoms.

All systems include 16 atoms in the unit cell. a–c The identified minimum-energy structures. d Success curves for optimization of the three systems. “ICE” refers to runs using ICE-groups containing all elements, “Ghost” refers to runs with 50% ghost atoms added, while “BEACON” refers to runs with no ICE-groups nor ghost atoms. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

The combinatorial complexity increases when there are more elements, and it is therefore expected that with more elements, it will be more difficult to find the ground-state structure. This is also what is observed in Fig. 10. The ICE approach improves the performance for the Ni3Al-system as already discussed in connection with Fig. 9, but standard BEACON also performs well for this system. However, standard BEACON does not find the lowest-energy structures for the three- and four-element systems in the twenty runs of 100 DFT calculations, while the ICE calculations do so. The ghost approach is seen to follow the same trends as standard BEACON while being slightly worse for Ni3Al.

Figure 11 shows the distribution of found energies. Inclusion of ICE is observed to substantially enhance discovery of low energy structures for Ni3Al as compared to BEACON with most of the low energy structures representing the global minimum. For NiPt2Al and NiPtZnAl inclusion of ICE likewise leads to a shift towards lower energies as compared to BEACON, with ICE discovering structures not found by BEACON at all. Discovery of structures close to the global minimum is however less frequent as contrasted to Ni3Al reflecting the greater complexity of the problems. In agreement with Fig. 10, the ghost approach is shown to lead to a similar energy distribution as standard BEACON but with slightly fewer low energy structures for all three systems. Hence, although the ghost approach has proven successful for clusters and lattice-based systems in ref. 44, the ghost method does not seem to generally improve the efficiency when simultaneously optimizing the unit cell. This conclusion seems intuitive as the cell would somehow have to accommodate the extra ghost atoms potentially hindering the relaxation of the unit cell.

All systems include 16 atoms in the unit cell. “ICE” refers to runs using ICE-groups containing all elements, “Ghost” refers to runs with 50% ghost atoms added, while “BEACON” refers to runs with no ICE-groups nor ghost atoms. The shown energies are relative to the lowest found energy for each system. The energies are sampled from 20 independent runs of 100 DFT calculations each. Only the lowest 2.5 eV of the distribution is shown.

Global optimiziation examples: combinations of hyperspatial and elemental coordinates

The approach presented here allows for optimizations with any combination of atomic coordinates in three or higher dimensions, unit cell parameters, and elemental coordinates describing existence and/or chemical element interpolation. We shall first illustrate some of the combinations and evaluate them on the Cu12Ni11 cluster which is more difficult to optimize than the Cu18Ni5 cluster studied in Figs. 4, 5c due to the higher combinatorial complexity.

Figure 12 shows the success curves for several different combinations of methods. Standard BEACON does not identify the correct ground state in any of the 20 runs of 100 DFT calculations. In fact, only optimizations including the ICE approach are able to find the lowest-energy structure. If the ICE approach is applied alone the ground state is found in five of the runs. However, combining ICE with either the hyperspace or ghost approach makes the search considerably more efficient, while combining all three doesn’t seem to further increase the efficiency for this specific system. The identified optimal structure is slightly lower in energy than the one found in ref. 43.

“BEACON” denotes a standard BEACON optimization. “Ghost” denotes inclusion of six copper and five nickel additional ghost atoms. “ICE” denotes combining copper and nickel in an ICE-group. “4D” denotes using hyperspace in four dimensions. An addition sign between any of of these labels indicate the methods being used simultaneously. The inset shows the identified minimum-energy structure. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

The behavior can be further analyzed by investigating the distribution of found energies for each run in Fig. 13. Here it is clearly seen how both the hyperspace and the ghost approach as expected shifts the energy distribution towards lower energies, however, to less extent than the ICE method. Any combination of ICE with hyperspace, ghost or both further shift the energy distribution towards lower energies leading to sharp peaks localized around the global minimum energy. Combining the hyperspace method with the ghost method has roughly the same distribution as hyperspace alone indicating that the two methods might serve similar purposes in this case.

Only the lowest 2 eV of the distribution is shown. “BEACON” denotes a standard BEACON optimization. “Ghost” denotes inclusion of six copper and five nickel additional ghost atoms. “ICE” denotes combining copper and nickel in an ICE-group. “4D” denotes using hyperspace in four dimensions. An addition sign between any of of these labels indicate the methods being used simultaneously.

The effect of combining our methods for bulk optimization with simultaneous unit cell relaxation is studied for NiPt2Al in Fig. 14. ICE is again essential for identifying the correct elemental ordering and hence the global minimum, as setups without ICE find it only once or not at all within 100 DFT evaluations. Combining ICE with hyperspace improves success rates as compared to ICE alone, while combining ICE with ghost reduces performance, confirming again that ghost is ill-suited for bulk systems with unit cell optimization.

“BEACON” denotes a standard BEACON optimization. “Ghost” denotes inclusion of two nickel, four platinum and two aluminum ghost atoms. “ICE” denotes combining nickel, platinum and aluminum in an ICE-group. “4D” denotes using hyperspace in four dimensions. An addition sign between any of of these labels indicate the methods being used simultaneously. The inset shows the identified minimum-energy structure. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

Global optimization examples: structure of dual atom catalysts

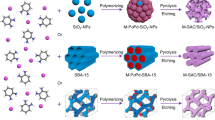

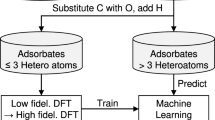

The transition to a more sustainable production of energy and green fuels requires development of efficient (electro-)catalysts. Recently, materials where a few atoms are embedded in nitrogen-doped graphene have attracted considerable attention as catalysts for for example CO2-reduction, oxygen reduction or evolution, and hydrogen evolution65.

Here we shall focus on the structure of a so-called dual atom catalyst consisting of an iron atom and a cobalt atom embedded in nitrogen-doped graphene. Much effort has gone into studying both the structural and catalytic properties of this system with a variety of experimental and theoretical approaches65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77. However, the structures have, as far as we know, not been systematically explored with a global structure search.

Here, we shall address the issue of the Fe-Co dual atom catalyst using a combination of the ICE and ghost approaches. Figure 15 shows the scenario for optimizing the location of a Fe and a Co atom on a fixed sheet of graphene where six carbon sites are replaced by nitrogen and four sites are vacant. The carbon and nitrogen form an ICE-group where four atoms are set to be ghost atoms, allowing the nitrogen and vacancies to move around on the graphene layer as seen in sub-figures a–f. The adsorbates Fe and Co form a second separate ICE-group, allowing the two to swap identity as observed between sub-figures f, g.

Nine snapshots labeled a to i in successive order from a single surrogate relaxation process for a Fe and Co adsorbate pair on graphene containing six nitrogen atoms and four carbon vacancies using a combined ICE and ghost approach. a represents an initial random configuration while (i) represents the end state also being the discovered optimal structure for the system. The graphene layer is fixed meaning that all movement in the layer is due to optimization of elemental coordinates. The element compositions are represented with colors, with C being gray, N being Blue, Fe being brown and Co being pink.

Figure 16 show the success curves for optimizing the system shown in Fig. 15 as well as a smaller system with only four nitrogen atoms and two vacant carbon sites. For the large system the minimum energy structure is found in all twenty independent runs within 100 DFT calculations while this is the case for eighteen runs for the smaller system proving the method to be feasible and effective.

a, b Identified optimal structure for a Fe and Co adsorbate pair on a fixed graphene layer with (a) four nitrogen substitutions and two carbon vacancies or (b) six nitrogen substitutions and four carbon vacancies. c Success curves for optimization of the two systems. The error shading is based on Bayesian uncertainty estimation, as detailed in the methods section.

The lowest energy structure of the large system is also visualized in Fig. 17a together with a structurally similar local minimum structure (Fig. 17b). The lowest energy structure is seen to be more symmetric with a mirror plane, which includes the Fe-Co axis and is perpendicular to the graphene plane. After relaxation of the two structures with PBE, the energy difference between the two is 2.3 eV for non-spinpolarized calculations, however, the inclusion of magnetism reduces this energy difference.

Interestingly, both of these structures have been investigated previously65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77. In ref. 66, the experimentally synthesized structure is identified as the asymmetric one based on XANES spectra, while in ref. 74 the symmetric one is preferred based on EXAFS measurements. The structure may of course depend on the detailed experimental conditions for the synthesis.

Discussion

We have presented a set of methods for global atomic structure optimization, where the main idea is to augment the configuration space with additional degrees of freedom in order to avoid barriers in the energy landscape. The methods have been applied to clusters and to three-dimensional bulk systems and some conclusions can be drawn about the virtues and limitations of the different methods and combinations of them.

The hyperspace approach seems highly efficient for closely packed systems, this being cluster or bulk materials. However, the usefulness of the approach for more open systems seems to be more limited. This may be a consequence of the higher kissing number in higher dimensions indicating a dense packing.

The ghost approach has earlier been demonstrated to lead to increased search efficiency for clusters and systems with atoms restricted to lattice sites44. The investigations performed here for bulk systems with variable atomic coordinate indicate a rather limited effect of the ghost variables when the method is applied alone. However, in combination with the ICE approach it does in some cases lead to a higher search efficiency.

The ICE approach is of course only applicable for systems with more than one type of element. It is particularly advantageous to use in systems where the composition leads to high configurational entropy with many local minima, which are time consuming to explore by other means. The method works best if the chemical elements in a common ICE-group are sufficiently similar. Metal atoms seem to combine well, as do some lighter elements like oxygen and nitrogen. However, combining transition metals with chalcogens in an ICE-group, as in the examples with TiS or NbO, makes the search less efficient.

The combination of several approaches (hyperspace, ghost, or ICE) is here investigated for the Cu12Ni11-cluster and the NiPt2Al-bulk. For Cu12Ni11, combining ICE with ghost or hyperspace leads to a substantial improvement over applying the methods separately. For NiPt2Al, combining ICE with hyperspace improves performance over either alone, while combining ICE with ghost reduces performance as compared to ICE alone.

Finally, the combination of ICE and ghost was shown to provide a novel approach to discovery of dual atoms catalysts on graphene substrates.

Let us also address some of the challenges and limitations that we have encountered. A key challenge is the construction of a set of default approximations and parameters, which will work for all systems. To mention an example, it is necessary to define in detail how to generate the “random” atomic structures used in the relaxations on the surrogate surface. If the atoms are too far apart they shall never “condense” into a cluster or material, but if they are too close, forming open structures may become exceedingly unlikely.

The Gaussian process is based on both energies and forces and the covariance matrix, therefore, has (NDFT(1 + 3Natoms)) × (NDFT(1 + 3Natoms)) matrix elements, where NDFT is the number of DFT calculations in the database, and Natoms is the number of atoms in the system. The covariance matrix has to be inverted many times when updating the hyperparameters, and this sets a limit on both the number of atoms and the number of DFT calculations in a single run. For large systems or situations where many DFT calculations are required, one has to either resort to more efficient implementations of the exact GP on GPUs78 or to apply approximations based on for example sparse (or induced-points) techniques79,80 or mixture-of-experts models81.

It is also worth noting that the length of the fingerprint increases rapidly with the number of chemical elements in the system. It involves angular distributions obtained from three atoms at the same time. We have demonstrated here that it is possible to consider a system like bulk AlNiPtZn with four different elements, but going much beyond this may require restructuring the fingerprint in order to retain computational efficiency. Likewise, due to the increase in potential atomic neighbors with the number of spatial dimensions, calculation time of the fingerprint grows rapidly, for bulk systems especially, in more than three dimensions.

Finally, we discuss some possible method extensions. It is shown in ref. 31 that combining simulated annealing with random sampling outperforms random sampling alone for optimizing complex atomic structures using an actively learned neural network. Combining random sampling with simulated annealing or other advanced global optimization techniques could likewise enhance the efficiency of our method. Implementing simulated annealing in the context of the hyperspatial method is straightforward, as it naturally extends the three dimensional version of the algorithm. Applying stochastic perturbations to chemical identities, would also be possible, but requires additional care to ensure that the imposed constraints are maintained.

Another modification could be to remove the constraint of fixed elemental sums, allowing stoichiometry and the number of atoms to change throughout the relaxation, potentially controlled by a set of chemical potentials. However, this would require training on variable atomic compositions, necessitating a local Gaussian process instead of the current global version. Such a method would resemble how atomic and elemental compositions vary during the reverse diffusion process in generative diffusion models17,18. A key difference would be that while diffusion models learn to generate new structures matching the distribution of structures in a large, predefined dataset, our method should learn the interatomic potential energy surface starting from minimal, actively generated datasets.

The idea of using machine learning models for implementation of hyperspatial optimization of atomic structures at first principles accuracy was first suggested by Pickard45. The approach presented in this paper uses a Gaussian process with a handmade fingerprint, chosen for its mathematical simplicity, high performance for small datasets, and a good ability to quantify uncertainty. It would be interesting to explore to which extent the fractional chemical identities and the hyperspace idea could be implemented in other machine-learning approaches like descriptor-based neural networks5, ephemeral neural networks9, or equivariant graph neural networks11,12,13. The hyperspace method can be directly implemented in techniques, which depend only on a description of the atomic structure through interatomic distances and bonding angles as for example suggested by Pickard for ephemeral neural networks9. Implementation of the fractional chemical elements will probably need some care. They can in principle be introduced in many different ways, but the usefulness of the implementation will depend on to which extent the barriers in the PES are in fact removed, and to this end we think that the “free-flow” property or similar constraints could be important.

Methods

In the following, we explain the applied methodology in more detail. We start with the DFT calculations and follow this with the details of the machine-learning model, i.e. the fingerprint and the Gaussian process including optimization of hyperparameters. We then provide a description of the Bayesian search algorithm including the random searches with the GP potential. Finally, we discuss success curves and the identification of ground state structures.

Electronic structure calculation

All DFT calculations are performed using GPAW82,83,84 and the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE)85,86. We apply the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)87 exchange-correlation functional, a planewave cutoff of 400 eV, and a Fermi temperature of 0.1eV. For clusters, only the Γ-point is used for k-point sampling while a k-point density of 6 Å was used for periodic systems in all periodic directions and a single k-point in the non-periodic directions. For the illustrative examples in Fig. 3, effective medium theory (EMT)53,54 was used instead of DFT. All calculations are without spin-polarization except the ones in Fig. 16. We note that the approach presented in this paper is not dependent on any specific electronic structure method or exchange-correlation functional and that any method of calculating energies and forces could have been used instead.

Machine-learning model: fingerprint

The atomic structures are represented by a fingerprint ρ(x, Q) with x and Q being the full set of spatial and elemental coordinates respectively. ρ(x, Q) consists of a radial part, ρR(r; x, Q), and an angular part, ρα(θ; x, Q). The radial fingerprint is a function of the pair-wise interatomic distances, rij, of atoms i and j whereas the angular fingerprint is a function of the triplet-wise angles, θijk, spanned between the distance vectors rij and rik from atom i to j and from atom i to k, respectively. Both rij and θijk, given by Eqs. ((7) and (8)), are trivially extensible to more than three dimensions. The elemental and existence fractionalization of atoms is made possible by introducing the scalar values q ∈ [0, 1] for each atom in each term of the fingerprint sum as described in refs. 43,44. ρR(r; x, Q) and ρα(θ; x, Q) are composed of several subfingerprints for each combination of two and three elements respectively concatenated together, the formula of which are given by Eqs. ((9), (10), (11)).

where \({R}_{c}^{R}\) and \({R}_{c}^{\alpha }\) are radial and angular cutoff radii, while δR = 0.4Å, δα = 0.4Å, and γ = 2 are constants. In general we use \({R}_{c}^{R}=5{r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) and \({R}_{c}^{\alpha }=3{r}_{co{v}_{max}}\), where \({r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) refers to the covalent radius of of the largest element in the system. For systems where the radius of the smallest element is 2/3 or less than that of the largest element \({R}_{c}^{\alpha }=2.5{r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) is used instead. The subscripts A, B, and C refer to elements with each radial and angular sub-fingerprint consisting of 200 and 100 entries for each elemental combination, respectively. A radial fingerprint containing two elements would thus have sub-fingerprints ρAA, ρAB, ρBA and ρBB (with the identity ρAB = ρBA) and thus a total length of 800 entries. A similar argument can be made for the angular part resulting in eight angular sub-fingerprints. In general, the radial and angular fingerprint will contain n2 and n3 sub-fingerprints respectively where n is the number of elements in the system.

The fingerprint counts all pairs and triplets within the radial and angular cutoff radii of each atom. The formalism extends to periodic boundary conditions by counting all pairs and triplets of the atoms in the primary unit cell with the atoms in a set of adjacent copies of the unit cell for any of the three standard spatial dimensions. Any hyperspatial dimension is considered non-periodic just as one would consider the third dimension non-periodic in relation to two-dimensional materials.

We now show the “free-flow” property mentioned in Section “Fingerprint” We consider a situation where two atoms, say atoms 1 and 2, exchange chemical identity. We focus on the radial part of the fingerprint as written compactly in Eq. (5), but it holds more generally. We now write out explicitly the terms involving atoms 1 and 2:

We consider a situation where no atoms are moved in coordinate space, but where the chemical identity A is transferred from atom 1 to atom 2 by an amount Δq. We have the changes Δq1,A = − Δq, Δq1,B = Δq, Δq2,A = Δq, and Δq2,B = − Δq. We furthermore assume that the distance between atoms 1 and 2 is larger than the cutoff distance so that fc(r12) = 0. In that case, the first term in Eq. (12) vanishes, and the last (fourth) term is unchanged by the process. In the remaining two terms the values of qi,A and qi,B do not change, so we can write the change in the fingerprint as

We now see that if the environment of atoms 1 and 2 are identical, the last parenthesis vanishes, and the fingerprint is completely unchanged during the process. We also see, that if the environments are different, the change in the fingerprint is linear in Δq, which invites a smooth variation of the energy in the Gaussian process.

Machine-learning model: Gaussian process

Energy and forces μ = (E, − F) and their associated uncertainties Σ(x, Q) are predicted by a Gaussian process described by the following equations88,89:

where μp(x, Q) is the prior mean, ρ(x, Q) is the fingerprint of the predicted structure, K and C = K + χ2I are the unregularized and regularized covariance matrices, respectively, with χ being a noise parameter, P is a vector of all fingerprints in the training data, y is the training energy and force targets, and μp(X) is the prior mean applied to all atomic structures in the training set. \(\tilde{K}(\rho [{\bf{x}},Q],\rho [{\bf{x}},Q])\) represents the covariance of the fingerprint with itself.

In this work, the kernel function in the covariance matrix has the form of the squared exponential function:

where ∣ρ1 − ρ2∣ is the Euclidean distance between two fingerprint vectors, l is the length scale, and σ2 is the prefactor.

Machine-learning model: prior potential function

The prior is set to a constant, μc, plus a repulsive potential, U[xij(x, Q)], depending on the spatial and elemental coordinates as described by Eq. (17).

where qi is the existence of atom i, \({r}_{co{v}_{e}}\) is the covalent radius of element e, rmin is the radius an atom will have at no existence and f is a scaling constant set to 0.8. rmin is set to the smallest covalent radius of any atom in the system. For the prior potential U[xij(x, Q)], we use a repulsive potential modified to go to zero at xij = 1 given by Eq. (17):

where \({\sigma }_{{p}_{rep}}\) is a strength constant set to 10 eV.

The associated forces, F(x, Q), element coordinate derivatives, dqi,e, and stresses, S(x, Q), of Eq. 20 are given by:

where we in the equation for the stress made use of the virial theorem.

On top of any prior potential, extra potentials may be applied. Excessively large cell volumes were penalized by an extra potential:

where σV is a strength constant and Vhigh is a potential onset below which the potential is zero. We set σV to \(10eV/{V}_{0}^{2}\) and Vhigh = 3.5V0 with \({V}_{0}={\sum }_{i}\frac{4}{3}\pi {r}_{cov,i}^{3}\).

Equation. (27) describes another extra potential punishing atoms being far into a non-periodic dimension of index d with coordinates xd

where σNP is a strength constant set to 10 eV/Å2. \({{\bf{x}}}_{{d}_{high}}\) and \({{\bf{x}}}_{{d}_{low}}\) are system specific potential onset values between which the potential is zero. This potential was applied to the bulk systems in Fig. 5f and Fig. 14 with \({{\bf{x}}}_{{d}_{low}}\) and \({{\bf{x}}}_{{d}_{high}}\) set to 0 and \(3{r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) respectively, where \(3{r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) is the largest covalent radius in the systems.

Machine-learning model: force and stress predictions

According to Eq. (14), the predicted force on atom i is given by

where \({{\bf{F}}}_{i}^{(p)}\) is the prior force and the kernel function, k(ρ1, ρ2), is taken between two atomic structures with fingerprints ρ1 and ρ2. Here, atomic coordinates with indices i and j contribute in ρ1 and ρ2, respectively, and j runs over all atoms.

Similarly the element coordinate derivative for element e of atom i is given by:

where \(d{q}_{i,e}^{(p)}\) is the prior derivatives.

As the total energy is in the end described through a fingerprint, which has an explicit dependence on the interatomic vectors rij, the stress can be calculated using the virial theorem. The stress is given by

where ε denotes the strain, and S(p) is the stress from the prior. The i-sum runs over the unit cell, while the j-sum runs over the surroundings within the interaction sphere defined by the cutoff of the fingerprint.

Machine-learning model: hyperparameter optimization

For each cycle in the global optimization algorithm (Fig. 2), the hyperparameters constituted by the length scale, l, the square root of the prefactor, σ, the noise, χ, and the prior mean constant, μc, are updated by maximizing the a posteriori probability p(l, σ, χ, μc∣y), given the training data y. The noise, prior mean constant, and the prefactor are set analytically as

with \({C}_{0}(P,P)={K}_{0}(P,P)+{\chi }_{r}^{2}I\), where yeng,n is the energy of structure n in the database containing a total of NDFT structures, Y is the total number of training targets, K0(P, P) is the covariance matrix without the prefactor, and χr is a relative noise constant set to 0.001. The relative-noise is identical for energy and force contributions. The total number of training targets is equal to 1 energy and 3Natoms forces for each structure in the training set, i.e., Y = NDFT × (1 + 3Natoms). As K0 and hence C0 depend on the length scale, the prefactor is always evaluated with respect to a given length scale, optimized by maximizing the log posterior \(\ln [p(l| y)]\):

where \(\ln [p(y| l)]\) is the log-likelihood and p(l) is a prior distribution for the length scale. The log-likelihood is expressed as

where we recognize the last term as the optimal prefactor at a given length scale from Eq. (34). The length scale is calculated in parallel by a nested grid search in the interval \([{\rm{median}}(\Delta {\rho }_{nn}),10\max (\Delta \rho )]\) in logarithmic space where Δρ marks the set of all euclidian distances between any two fingerprints in the training set, and Δρnn marks the set of nearest neighbor distances i.e. the shortest distances between a given fingerprint and all other fingerprints. This interval is chosen to seek a good compromise between accuracy and interpolatability between data points and new structures in the surrogate surface with the latter being of high importance when interpolating to fictive dimensions which can not be sampled by the model. To mitigate overfitting and secure interpolatability at low datasets a log-normal length scale prior distribution is applied in Eq. (36):

where μLN and σLN are the mean and the width in the logarithmic space, respectively. σLN is set to 2 and μLN is set from the equation: \({\rm{mode}}[p(l)]=\exp ({\mu }_{LN}-{\sigma }_{LN}^{2})=0.5[{\rm{mean}}(\Delta \rho )+\max (\Delta \rho )]\).

To make sure the radial and angular fingerprint had a reliable relative scaling across systems, the angular part was scaled by the following factor:

where ∣ρR∣abs and ∣ρα∣abs refer to the set of absolute differences between any two fingerprints in the training set for the radial and angular fingerprints respectively.

Bayesian search algorithm: overview

The overall structure of the Bayesian search algorithm shown in Fig. 2 has already been discussed in Section “Bayesian search algorithm”, but a number of details remain to be described. The following sections describe the generation of random structures, performing relaxations with the GP surrogate potential, selection of promising structures for database inclusion using an acquisition function, and discarding of undesired structures.

A potential issue with the Bayesian search method is that the surrogate PES could “degenerate” so that the global minimum never appears and all searches would lead to local minima, but not the global one. This behavior is counteracted by several means. Firstly, the use of an acquisition function instead of the bare energy will invite for “exploration” instead of only “exploitation” of previously investigated basins of the PES. Secondly, new suggested candidate structures obtained by relaxations on the surrogate PES are not selected if they are too close to already evaluated structures in the DFT database as described below. Thirdly, it might happen that at some stage in the optimization all relaxations in the surrogate surface lead to already known configurations (or gets discarded otherwise). In that case a new, truly random structure is created, directly evaluated with DFT (without relaxation on the surrogate PES), and included in the DFT database. So in principle, there is always a completely random element ensuring that the surrogate model will be improved in new regions of the configuration space.

Bayesian search algorithm: random structure generation

The following describes different ways of randomly placing atoms in a confined space. The atoms are afterwards repelled from one another. We found the potential Eq. (20) to be too strong and instead use a softer parabolic potential given by Eq. (40):

where the strength constant \({\sigma }_{{p}_{P}}\) is set to 10eV. The scaling constant f in Eq. (19) is set to 0.9 for structures entering the initial database and for generating random structures for surrogate relaxation.

Random cells are generated by generating a unit cube as represented by a 3 × 3 unit matrix and adding random numbers in the interval [− ξc, ξc] to all entries with ξc = 0.25 to secure an ensemble of cells with varying yet not extreme angles between the lattice vectors. The cell is next scaled to a volume in the range [1Vbase, 3Vbase] while maintaining the cell morphology, where Vbase is a reference volume given by:

where VD(rcov,i) is the volume of atom i with covalent radius rcov in D dimensions, Γ is the gamma distribution, and DHyper,k is the size of the non-periodic hyperspatial dimension k, set to \(3{r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) with \({r}_{co{v}_{max}}\) being the largest covalent radius of any atom.

This procedure is chosen to secure a similar span of initial atomic packing fractions in atomic systems of different dimensionality.

While working well for most compact materials this strategy is ill-suited for bulk systems with a lot of internal vacuum in which case one would have to come up with a larger guess for Vbase and possibly a larger interval range.

The atoms are subsequently placed randomly inside the cell and the hyperspatial dimensions. The structure is relaxed by the repulsive potential of Eq. (40) thus potentially slightly expanding the cell. For the case of Fig. 5f and Fig. 14, Eq. (27) was also applied alongside Eq. (40).

For clusters, i.e. non-periodic systems, a cubic cell of length 25Å was set with a centrally centered cubic subvolume box of range [1Vbox, 3Vbox] with Vbox = ∑iVD(rcov,i) within which the atoms are placed and subsequently relaxed in the repulsive potential.

For dual-atom catalysts, initial structures were generated by creating a graphene layer, randomly substitute NN carbon atoms with nitrogen and remove NV carbon atoms. Adsorbate atoms were randomly placed above the substrate within 3Å. In surrogate relaxations, the graphene substrate remained intact, with nitrogen substitutions and vacancies generated via ICE and ghost methods, respectively.

Random elemental coordinates are generated by combinatorial use of the Dirichlet rescale algorithm90,91 to satisfy the elemental constraints of Eq. (1).

Bayesian search algorithm: details of the surrogate relaxations

A key element in the procedure is the relaxation of randomly generated structures in the GP surrogate potential. Figure 4 illustrates such a relaxation process for a Cu18Ni5 cluster in the GP predicted potential energy surface. Due to the additional hyperspace and elemental coordinates, it is necessary to divide the relaxation process in four phases as we shall now discuss.

In the first phase, spatial and elemental atomic coordinates are updated simultaneously. As atoms embedded in the (3 + DHyper)-dimensional space will not spontaneously settle into the three dimensional space, all DHyper coordinates are punished by a potential, Uhs and its resulting force Fhs given by Eqs. (43) and (44)

where ∣xhs,i∣ is the Euclidean norm of the vector of hyperspatial coordinates for atom i and ω(c) is a custom time-dependent strength factor. The relaxation is structured into \(n_{c}^{hs}\) cycles of index c each lasting \(n_{c_{sub}}^{hs}\) steps. In this paper, the strength factor was set to

with the parameters a and b tuned such that k(0) = 0.1 and \(k(n_{c}^{hs})\) = 1000 with \(n_{c}^{hs}\) = 100 to set aside 25 cycles for one order of magnitude, as what constituted a good magnitude and rate progression was observed to be system specific. Too slow progressions result in long run times whereas too fast disrupts hyperspatial relaxation. Likewise, insufficient final magnitude results in the failure of squeezing the atoms into three dimensions.

During this phase, the total existence of atoms in ghost-possessing elements/ICE-groups are restricted to the interval [qlow, 1] with 1 ≫ qlow > 0 since atoms with zero existence do not interact with other atoms at all. Hence, they become idle during the relaxation as argued in ref. 44. Consequentially, the total elemental sum of any ghost-possessing element is temporarily set to \({N}_{e}+{N}_{{e}_{Ghost}}{q}_{low}\). The phase ends by projecting all atoms from (3 + DHyper) dimensions into three dimensions, which happens when ∣xhs,i∣ < 0.01Å for all atoms.

In the second phase, the relaxation proceeds as in phase 1 but with all atoms embedded in three dimensions and the existence interval of ghost-possessing elements/ICE-groups kept at [qlow, 1] for \(n_{q_{low,1}}^{3D}\) steps.

In the third phase, the existence interval of atoms belonging to ghost-possessing elements/ICE-groups is changed from [qlow, 1] to [0, 1] and the total elemental sum of atoms belonging to ghost-possessing elements is changed from \({N}_{e}+{N}_{{e}_{Ghost}}{q}_{low}\) back to Ne by removing \({N}_{{e}_{Ghost}}{q}_{low}\) of elemental existence starting from the atoms with lowest existence and up. The spatial coordinates and elemental coordinates are then optimized with \(n_{q_{0,1}}^{3D}\) steps.

In the fourth phase, the atoms of any ICE-group are assigned to an element based on the highest atomic elemental coordinate subject to the elemental sum constraints and excess atoms of any ghost-possessing elements are deleted in order of lowest to highest atomic existence. The spatial coordinates are then relaxed with all elemental coordinates kept at unit identity for \(n_{ui}^{3D}\) steps.

In all steps, the lattice vectors of the unit cell may be optimized at the same time if desired. The relaxation steps terminate either when the total number of steps is reached or when the desired convergence criteria is met.

In this work, all relaxations were limited to a maximum of 700 steps with parameters as listed in Table 1. Figure 4 illustrates a surrogate relaxation of a Cu18Ni5 cluster extended to four spatial dimensions where Cu and Ni form an ICE-group possessing 11 ghost atoms. The atoms in Fig. 4a are seen to initially form a dense globule with seemingly overlapping atoms which, when comparing to Fig. 4b, is observed to be due to atoms being distant in the fourth dimension. As the relaxation progresses, the atoms are squeezed out of the fourth dimension, and the fractional elements are generally observed to converge to 0 or 1 except for a few atoms. The atomic energy of Fig. 4a can be divided into four segments: 1) initial decline due to relaxation in the four dimensions with low penalty constant, 2) a steady increase due to the increasing penalty constant, 3) a second decrease due to atoms being squeezed out of the fourth dimension hence eliminating the penalty due to Eq. (43), and 4) a final segment with no atomic penalty where the existence fractions are also allowed to go to 0. The jagged shape of the energy curve reflects the cycles and sub-steps of the hyperdimensional squeezing phase. Which atoms should exist or not is observed to be decided during the first few steps of the relaxation as seen from Fig. 4h.

Relaxations are generally performed using the SLSQP (Sequential Least Squares Programming), except in figures with only hyperspatial optimization without elemental coordinates in which cases the L-BFGS-B method (Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno with Bounds) is used instead as it is in general more stable than the SLSQP method. Both methods are used as implemented in the scipy package92. The L-BFGS-B optimizer converged when all projected gradients were below 0.01 eV/Å, and SLSQP when the energy change between iterations was under 0.001 eV.

We use 40 parallel surrogate relaxations before we apply the acquisition function and perform a DFT calculation for the best candidate.

Bayesian search algorithm: acquisition function

Selection of the best candidate structure at the end of a cycle in the global optimization algorithm is determined by an acquisition function A(x) which in the present study is set to a lower confidence bound (LCB)

where κ is a constant set to 2 while E(x) and Σ(x) are the predicted energy and uncertainty of Eqs. (14) and (15), respectively. The dependency on Q is omitted as the acquisition function is only used on atoms with unit elemental identities.

Bayesian search algorithm: discarding structures