Abstract

Single-phase ordered body-centered cubic or B2 multi-principal element intermetallics (MPEIs) have garnered significant attention due to their exceptional mechanical and functional properties. However, their discovery in complex compositional spaces is challenging due to the lack of high-dimensional phase diagrams and the inefficiency of traditional trial-and-error methods. In this study, we developed a physics-informed machine learning (ML) framework that integrates a conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) with an artificial neural network (ANN). This approach effectively addresses the challenges of data limitation and imbalance, enabling the high-throughput generation of B2 MPEIs. Using this framework, we successfully identified a wide range of B2 complex alloys, spanning quaternary to senary systems, with superior mechanical performance. This work not only demonstrates a significant advancement in the discovery of B2 MPEIs but also provides an accelerated pathway for their design and development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, single-phase B2 multi-principal element intermetallics (B2 MPEIs)1,2, which are typically composed of three or more principal elements, have attracted considerable research interest due to their exceptional properties. These include shape memory effect3, stable elastic energy storage4, high strength5,6, superior plasticity6, and superconductivity7. Most reported B2 MPEIs are composed of principal elements such as Ti, Zr, Hf, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu, with some variants where Ti, Zr, or Hf are substituted by Al8,9,10,11. However, as highlighted in refs. 2,12, despite the vast and unexplored compositional space, only a limited number (i.e, ~20) of single-phase B2 MPEIs have been experimentally identified to date, with the majority being binary and ternary alloys derived from phase diagrams. This underscores the significant challenges and untapped potential in discovering new B2 MPEIs within complex compositional systems.

To discover new B2 MPEIs with superior properties, researchers have tuned to computational approaches such as density functional theory (DFT)13,14,15 and the CALPHAD method8,16,17. While DFT provides highly accurate phase predictions, it is hindered by significant computational resource requirements and time-intensive calculations. Similarly, CALPHAD relies on extensive thermodynamic and microstructural databases tailored to high-entropy alloys (HEAs), which restricts its efficiency and scalability. As a result, these conventional methods fall short in enabling high-throughput screening of new B2 MPEIs, highlighting the need for more advanced and efficient discovery frameworks.

Recently, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool for accelerating alloy discovery, leveraging its ability to uncover complex relationships between alloy compositions and targeted phases or structures without relying on exhaustive theoretical calculations18,19,20. By incorporating descriptors derived from DFT or empirical physicochemical parameters, ML approaches have been successfully applied to the prediction of phase formation in intermetallic compounds with B221, L1022, L1223, Heusler24 and Laves25,26 structures. However, DFT-calculated formation enthalpies, often used as a reference for phase stability, typically neglect finite-temperature effects and fail to capture the metastable nature of many intermetallics23. Moreover, prior studies have primarily focused on binary and ternary systems, limiting their applicability to high-dimensional compositional spaces. To address this, Qi et al.27 developed a model to predict the principal phases of MPEIs (B2, Heusler, and Laves) using an extensive set of over 2500 candidate descriptors and complex feature engineering strategies. Despite achieving reasonable accuracy, the model lacks the ability to actively generate new B2 compositions or exclude multiphase regions28. Recently, Shargh et al.29 further introduced a deep learning framework involving 30 descriptors and deep architectures (10–13 hidden layers with 44–85 neurons), which improved classification accuracy but lacked experimental validation and showed limited generalizability across diverse alloy systems. Compared to ML-assisted studies on FCC, BCC, or eutectic HEAs20,30,31,32, the application of data-driven methods to the design of MPEIs with well-defined crystalline structures remains relatively underexplored, especially in the context of generative models and physical interpretability.

Unlike traditional supervised ML models, generative ML models offer distinct advantages by directly generating compositions with desired phases and/or properties from latent spaces, eliminating the need for manual input and overcoming limitations imposed by restrictive composition variations33,34. Among these, generative models such as variational autoencoder (VAE) and generative adversarial network (GAN) have shown particular promise, as evidenced by their successful applications in designing eutectic HEAs20 and high entropy bulk metallic glass33. In this study, we developed a physics-informed ML framework that integrates supervised artificial neural network (ANN) and VAE models. Using this framework, we successfully identified B2 MPEIs across quaternary to senary alloy systems, achieving unprecedented efficiency and accuracy compared to conventional methods. This work marks a significant advancement in the ML-driven design of single-phase MPEIs, opening new avenues for accelerated discovery in complex compositional spaces.

Results

Physics informed machine learning

As illustrated in Fig. S1, given the scarcity of reported B2 MPEIs in most alloy systems, our investigation focused on alloy systems containing refractory elements (e.g. Ti, Zr, Hf) and 3 d transition elements (e.g., Co, Ni, or Fe), which are thought to be able to form B2 structures due to the distinct elemental properties35,36. Alloy compositions and structures from relevant literatures (e.g., quaternary, quinary and senary systems) and binary/ternary phase diagrams37,38 were compiled to establish a representative database (see Table S1 for details). The phase or microstructures of all alloys in Table S1 fall into three classes, single-phased B2, multi-phased intermetallics (MPIM) and solid-solution + intermetallic (SS + IM). Compositions were classified as B2 if they crystallized directly into a single-phase B2 structure during casting of melt, while others as MPIM or SS + IM. The final database of three alloy systems is presented in Fig. 1a–c. For instance, 38 compositions in the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system were identified as single-phased B2 alloys, while the remaining 358 were categorized as MPIM or SS + IM alloys. This results in a significant data imbalance, with a B2 to non-B2 ratio of 1:9. Comparable imbalance patterns were observed in other alloy systems such as Co-Ni-Ti-Zr (Fig. 1b) and Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf (Fig. 1c), which poses challenges for ML-based alloy design20.

a Quinary Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system database. b Quaternary Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system database. c Senary Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf system database. d The mixing enthalpy Hij (kJ/mol) between candidate elements104. e Atomic radius ri (Å), electronegativity χi and valence electrons number VECi.

The development and selection of appropriate data descriptors is critical for developing reliable ML models20,39,40,41. In the ML-assisted design of HEAs with BCC, FCC or amorphous structures, classic parameters such as δ (atomic size mismatch), ΔHmix (enthalpy of mixing), ΔSmix (entropy of mixing), Δχ (electronegativity difference), and VEC (valence electron concentration) have been commonly employed as data descriptors42,43. While these parameters are effective in distinguishing SS and amorphous phases, they exhibit limitations in differentiating MPEIs from other phases44,45,46. For the rapid identification of single-phased B2 MPEIs, the selection of physically meaningful data descriptors that capture the intrinsic characteristics of the B2 structure is essential. In our previously proposed random sublattice model12, a B2 structure can be represented as a pseudo-binary system (PBS), characterized by two key parameters: δmean, which denotes the average atomic size difference between the two sublattices, and (H/G)pbs, which quantifies the ordering tendency between sublattices (see Table 1 for details).

Building upon our earlier random sublattice model12, we introduce additional thermodynamic and geometric descriptors to assess the stability of long-range chemical ordering versus random mixing in the two sublattices of a B2 structure. Previous studies47,48,49 suggest that the stability of long-range chemical ordering correlates positively with mixing enthalpy (ΔH), mixing entropy (ΔS), and differences in atomic radius (ri), electronegativity (χi), and valence electron concentration (VECi). Figure 1d–e maps the elemental distributions of Hij, ri, χi and VECi for nine candidate elements (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ti, Zr, Hf). These elements are categorized into two distinct groups: refractory elements (Ti, Zr, Hf) versus 3d transition metals (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu). According to the literature6,50,51,52,53, these elements intend to segregate to form long-range chemical order while mix to form chemical disorder in distinct sublattices in B2 intermetallics because of the enhanced inter-group disparity in physicochemical properties relative to intra-group variations, which may generate thermodynamic driving force to overcome ΔS, thereby stabilizing the chemically ordered B2 structure. As summarized in Table 1, the tendency favoring such a mixed chemical order is quantified by the following descriptors: Spbs, δpbs, ∆Hpbs, σVECpbs, σχpbs, (H/G)pbs and (δpbs/δ\()\). Theoretical considerations indicate that: (1) high \({S}_{{pbs}}\) and low absolute \(\triangle {H}_{{pbs}}\) favor chemical randomness over ordering12,54. (2) δpbs and (δpbs/δ) reflect the reduction in atomic size differences due to ordering, where large values indicate a stronger ordering tendency. (3) Similarly, higher σVECpbs and σχpbs correlate with increased ordering stability. Furthermore, the stability of individual sublattices is evaluated using σHpbs, ∆Hmean, σHmean, δmean, and σVECmean. Consistent with solid solution models for single phase HEAs45,55,56,57, large ∆Hmean and δmean promote sublattice ordering. However, as noted in refs. 6 and 12, significant variance in VECi (σVECmean) induces lattice distortion, destabilizing the B2 structure. Additionally, elevated σ∆Hpbs suggests heterogeneous bonding tendencies, which may drive short-range chemical ordering or elemental segregation58,59,60, potentially leading to precipitation or phase separation61,62,63. In addition to the above data descriptors, the classic parameters \(\chi\) and σχ were also used since electronegativity can aid in distinguishing solid solutions and multi-phase immiscibility55,64. As a result, 18 physics-informed data descriptors were employed for the ML-assisted design of B2 MPEIs, hereafter referred to as random-sublattice-based descriptors. For comparison, 16 classic descriptors (including δ, ΔHmix and ΔSmix, see Table 2 for details) was also employed to train the ML model, which are referred to as random-mixing-based descriptors. Before training the ML models, all descriptors for an alloy system with N compositions were normalized using the following formula:

Where xi,j and \({x}_{i,j}^{0}\) represent the normalized and initial values of the ith descriptor for the jth composition, respectively. Additionally, \({x}_{{imax}}^{0}\) and \({x}_{{imin}}^{0}\) denote the maximum and minimum values of the ith descriptor.

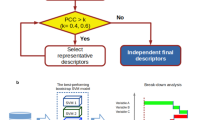

Within ML-assisted alloy design, one-hot encoding (OHE)19,65 is particularly well-suited for phase/microstructure classification due to its inherent mutual exclusivity and exhaustiveness—key requirements when modeling multi-phase systems, as evidenced in prior studies66,67,68. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, OHE encodes the three phases in this study as orthogonal vectors (B2: [1,0,0], MPIM: [0,1,0], SS + IM: [0,0,1]), serving as data labels compatible with conventional classifiers like artificial neural network (ANN). However, since the discovery of SS + IM or MPIM phases in the compositional space is not meaningful in the context of this study and falls beyond its primary focus. Therefore, for generative models such as variational autoencoders (VAEs), we developed a streamlined binary OHE scheme optimized for B2 MPEIs discovery. This adaptation consolidates MPIM and SS + IM into a single non-B2 class (encoded as 0), contrasting with the B2 class (encoded as 1), thereby reducing feature dimensionality, and decreases matrix sparsity by 66.7% (from 3D to 1D), thereby improving computational efficiency.

To mitigate the issue of data imbalance, the compiled dataset was refined by removing less informative entries, a strategy to enhance model training efficiency as demonstrated in our previous study20. As depicted in Fig. 2b, the normalized dataset was first analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA)69 to reveal its underlying structure, followed by K-means clustering70 to identify compositionally distinct subgroups for data refinement. The refined dataset was then utilized for two purposes: (1) training an ANN-based classification model (Fig. 2c); and (2) training a generative CVAE model to explore new B2 compositions (Fig. 2d). Candidate B2 compositions generated by the CVAE were subsequently filtered through the ANN classifier, with successful predictions selected for experimental validation (Fig. 2e).

In the case of the dataset for the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system, we found that the random-mixing-derived dataset, which used random-mixing-based descriptors, failed to differentiate single-phased B2 alloys from multiphase structures in the PCA plot (Fig. 3a). In the contrast, the random-sublattice-derived dataset, utilizing random-sublattice-based descriptors, enabled a clear separation of B2, MPIM and SS + IM alloys (Fig. 3b). The whole dataset D0 was divided by K-means into three groups, which are denoted as M1, M2, M3 when using random-mixing-based descriptors, and as S1, S2, S3 when using random-sublattice-based descriptors. All single-phased B2 alloys were clustered into the first group (S1 or M1), whereas a considerable fraction of non-B2 alloys were distributed across the remaining groups (S2 + S3 or M2 + M3). As illustrated in Fig. 3c, d, three training datasets were generated by combining the B2-contained group with the other two groups. Using random-mixing-based descriptors, the B2: non-B2 ratio of DRM1 increased to 1:5 from the 1:9 of D0, while DRM2 and DRM3 achieved ratios of ~1:7. In comparison, the use of random-sublattice-based descriptors alleviated data imbalance more significantly, with the B2:non-B2 ratio reaching 1:1 in DRS1, and 1:6 and 1:4 in DRS2 and DRS3, respectively. These results indicate that PCA combined with K-means clustering is effective in constructing more balanced datasets, especially when leveraging random-sublattice-based descriptors, whose enhanced phase separability directly contributes to this improvement.

The PCA plot of the whole dataset using (a)16 random-mixing-based descriptors and (b) 18 random-sublattice-based descriptors, through K-means clustering the whole dataset were divided into three groups, separated by the dotted lines; The data structures of (c) random-mixing-derived and (d) random-sublattice-derived training datasets.

As shown in Fig. S2, the training datasets in the Co-Ni-Ti-Zr and Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf systems were constructed following procedures analogous to those used for the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system. Similarly, PCA combined with K-means clustering effectively improves the B2: non-B2 ratios of these datasets, further confirming the superior B2/non-B2 separability of random-sublattice-based descriptors.

As shown in Fig. 4a, for the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system, the ANN model trained on random-mixing-derived D0 dataset effectively identifies MPIM and SS + IM alloys but exhibits poor accuracy in predicting B2 structures, primarily due to severe data imbalance71,72. In contrast, the model trained with 18 random-sublattice-based descriptors achieves more balanced predictive performance, attaining 100% precision and 97.4% recall for B2 phase identification (Fig. 4b). The confusion matrix of the DRM1-trained ANN model (Fig. S3a) further confirms that random-mixing-based descriptors necessitate a more balanced dataset for precise discrimination of single-phased B2 structure.

To assess the model stability, the ANN was subsequently trained 400 times independently for each dataset (i.e., D0, DRM1, DRM2, DRM3, DRS1, DRS2, and DRS3). Figure 4c reveals that random-sublattice-derived D0 dataset, along with its subgroups (DRS1, DRS2, and DRS3) maintain high and stable F-measure values (0.97 ± 0.03) regardless of data imbalance, whereas the random-mixing-derived datasets show markedly lower performance, with only DRM1 achieving moderate accuracy. To confirm that this difference arises solely from the descriptor type and not from differences in dataset composition, we repeated the training after exchanging the descriptors between the two groups of datasets. As shown in Fig. S4, the random-sublattice-based descriptors still yield superior and robust training performance, confirming that descriptor type is the dominant factor.

Like the ANN model, the CVAE model trained on random-sublattice-derived D0 dataset, achieves clear separation between B2 and non-B2 alloys in latent space (Fig. 5a), without clustering preprocessing as needed for random-mixing-derived dataset (Fig. S3b). Compositional analysis of 10000 generated alloys (5000 B2 + 5000 non-B2) reveals distinct elemental partitioning: B2 alloys exhibit near-zero concentration differences between two element groups shown in Fig. 1d, e (Dcom), while non-B2 alloys display Dcom values up to 20 at.% (Fig. 5b). Here Dcom is calculated as:

The validation of physics-informed ANN model shows that 90% of generated B2 alloys possess a PB2 >90%, with non-B2 alloys predominantly forming MPIM/SS + IM structures (Fig. 5c). As illustrated in Figs. S5–S7, similar training results in Co-Ni-Ti-Zr and Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf systems further demonstrate that our random-sublattice-based descriptors offer superior performance in both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency for targeted B2 alloy composition separation and generation, compared to classic random-mixing-based descriptors. All the new B2 MPEIs discussed below were generated and verified using the ML models trained on the whole datasets with random-sublattice-based descriptors.

Experimental validation

As shown in Fig. 6a–c, three potential B2 Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr MPEIs with predicted PB2 values exceeding 0.95 were selected from CVAE-generated alloys. Notably, most of potential B2 alloys in the pseudo-ternary compositional diagrams exhibit Dcom values clustered around zero (i.e. line compounds), while alloys with multiphase structures typically show larger Dcom values. With increasing Fe and Zr concentrations, the upper limit of the Dcom for B2 phase formation decreases from ~10 at.% to near zero.

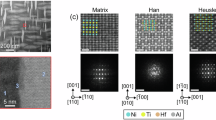

a–c The distribution of PB2 value in the pseudo-ternary compositional diagrams, three alloys including Fe2.7Co18.6Ni28.8Ti41.8Zr8.1 (Alloy 1), Fe7.4Co11.6Ni31Ti43.5Zr6.5 (Alloy 2) and Fe8.8Co14.2Ni26.5Ti40.1Zr10.3 (Alloy 3) were selected for preparation due to their PB2 value exceeding 0.95. d The XRD patterns of as-cast and as-homogenized alloys. e The SEM images of as-cast alloys. f BF, SAED and HRTEM images of as-homogenized alloys (two sublattices of B2 structure were marked by blue and green balls respectively, similarly hereinafter).

The XRD patterns of as-cast MPEIs (Fig. 6d) reveal a single-phase BCC/B2 crystalline structure, further confirmed by scanning electron SEM images (Fig. 6e) showing typical dendritic structures with noticeable segregation. After homogenization, the XRD patterns reveal sharper B2 superlattice peaks (Fig. 6d), and the dendritic segregation is effectively eliminated (Fig. S8). Bright-field (BF), high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) images (Fig. 6f) display distinct superlattice characteristics without evidence of antiphase domain boundaries or phase boundaries, confirming the formation of a single-phased B2 structure rather than a BCC + B2 dual-phase9,73,74,75,76,77,78,79.

Additionally, two alloys with low PB2 values were synthesized to assess the framework’s capability in predicting non-B2 structures. As illustrated in Fig. S9, both alloys formed MPIM structures, further demonstrating the predictive power of our ML framework for non-B2 alloys. These results provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of our physics-informed ML framework in generating novel single-phased B2 MPEIs within the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr alloy system.

In the Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system, the Co19.9Ni30.5Ti38.1Zr11.5 alloy, with a predicted PB2 value exceeding 0.95, was selected for experimental evaluation. The distribution of PB2 values across the compositional space, as depicted in Fig. 7a, demonstrates that indicates that the probability of B2 formation has the correlations with Dcom and CZr which is similar to the trends observed in the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system. The microstructure of this alloy, shown in Fig. 7c, d, indicates the characteristics of single-phased B2 structure and closely aligns with the ML model’s prediction.

The alloy Cu4.7Co9.2Ni36.4Ti38.7Zr7.4Hf3.5 was selected based on its PB2 value exceeding 0.99, as predicted by the ANN model. Notably, in the Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf system, if the Dcom value remains constant (~0.3 at.%) near zero, the PB2 value of alloy compositions declines sharply when Cu content exceeds ~25 at. % (Fig. 8a). XRD patterns and SEM images of both as-cast and as-homogenized alloys, shown in Fig. 8b, c, confirm the presence of B2 structure, while TEM characterization (Fig. 8d) provides further evidence supporting the single-phased and long-range chemical ordering nature of the material.

Beyond the above three alloy systems, the physics-informed ML framework also demonstrated success in discovering new single-phased B2 MPEIs in other alloy systems. For instance, experimental validations were successfully performed in the Fe-Ni-Ti-Zr and Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf systems (Fig. S10a, b), confirming the effectiveness of our approach.

Furthermore, as depicted in Fig. S10c–e, the ML framework was extended to an even more complex octonary system, Cr-Fe-Co-Ni-Cu-Ti-Zr-Hf, which includes 871 alloy compositions and introduces Cr as an additional element not previously covered in Fig. 1. In this high-dimensional space, the ML models maintained strong predictive performance and successfully identified new potential B2 compositions, further validating its scalability, robustness, and generalizability.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate the effectiveness of the physics-informed ML framework in discovering new B2 MPEIs, particularly when employing random-sublattice-based descriptors. Several previously unreported compositions across various alloy systems were successfully identified.

Subsequently, we systematically investigate the factors governing the formation of the single-phased B2 structure, and based on these insights, elucidate the origins of the near-linear distribution characteristics observed for single-phase B2 alloys in compositional diagrams. As shown in Fig. 9a, the sensitivity coefficients indicate that PB2 is predominantly governed by δmean and ∆Hpbs, while it exhibits a negative correlation with Spbs, σHpbs, σHmean, σTmean and Tm. Notably, (H/G)pbs and (δpbs/δ) also positively affect the formation of single-phased B2 structure, although their contributions are somewhat underestimated due to logarithmic transformation. In comparison, other descriptors such as χ and σχ play relatively minor roles in determining the stability of single-phased B2 structure. Overall, the variation of PB2 with respect to the key random-sublattice-based descriptors (highlighted in “Physics informed machine learning”) are generally consistent with the theoretical expectations at the design state of these descriptors.

a Sensitivity coefficients derived from trained ANN models. b Correlation coefficients between all parameters in the initial dataset of the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system, with those exceeding ±0.75 highlighted. c Evolution of δmean + σVECmean and (H/G)pbs + (δpbs/δ) with varying Ti and Zr content along the Dcom = 0.1 at.% in Fig. 5a. d, e Distribution of PB2, δmean + σVECmean, (H/G)pbs + (δpbs/δ) and VEC in the Fe-Co-Ni pseudo-ternary diagram at Dcom = −0.4 at.%.

Regarding melting-point-related descriptors σTmean and Tm, their effects can be explained as follows: (1) Figure 9b shows that σTmean correlates positively with δmean and σVECmean, implying that a lower σTmean intrinsically corresponds to reduced δmean and σVECmean. Thereby, reduced sublattice ordering (δmean) and lattice distortion (σVECmean) enhance the stability of single-phased B2 structure. (2) Also evident in Fig. 9b, Tm correlates negatively with VEC. A lower Tm (associated with a lower VEC) indicates higher Fe content, since Fe has a lower VECi than Co and Ni (Fig. 1e). According to the PBS model6, Fe tends to destabilize the B2 structure relative to Co and Ni, as evidenced by the inability of the Fe-Zr binary system to form B2 phase80,81,82,83. Consequently, an increased Fe concentration deteriorates the stability of the B2 phase. This is also consistent with the previous experimental findings84, where excessive substitution of Fe for Co and Ni in (Co, Ni)Ti-based B2 MPEIs promoted the formation of Laves phase. It should be noted that the strong correlation observed between some descriptors implies a degree of feature redundancy, which we confirmed by training ANN models with reduced descriptor sets. As shown in Fig. S11, the resulting F-measure values remained nearly unchanged. This redundancy stems from the inherent physicochemical property distribution across element groups, as discussed in “Physics informed machine learning”. Although certain descriptors are strongly correlated, they represent different physical mechanisms relevant to B2 formation. For this reason, all such descriptors were retained in the ML framework.

Additionally, a notable trend is that high PB2 compositions cluster around the Dcom = 0 line. As pointed by random sublattice model12, a larger Dcom value necessitates that atoms originally preferred to enrich one sublattice are partially redistributed to the other, destabilizing the B2 phase and promoting MPIM formation through increased δmean and reduced (H/G)pbs. Consequently, most reported single-phased B2 alloys adhere to a 1:1 ratio between two element groups2. This can also explain why certain generated B2 compositions with high Dcom (6–7 at.%, likely due to the error of CVAE model) exhibit low PB2 values (Fig. 5b, c). In practice, the segregation at grain boundaries and dendrites during solidification is inevitable and usually serves as a precursor to phase decomposition85,86. All discovered B2 MPEIs exhibited evident dendritic segregation in their as-cast microstructures (Figs. 6e, 7c, 8c). Thus, B2 MPEIs with higher upper limit of Dcom can tolerate greater segregation and possess enhanced single-phased B2 stability during casting.

For analyzing the influence of element-concentration trade-offs on the formation and distribution of B2 phase, the distributions of key random-sublattice-based descriptors were mapped across the compositional diagrams. For ease of presentation, the sum of δmean and σVECmean (i.e., δmean + σVECmean) was used to represent structural disparity (ordering and frustration) in sublattices, while the sum of (H/G)pbs and (δpbs/δ) [i.e., (H/G)pbs + (δpbs/δ)] was adopted to represent the tendency toward chemical ordering, as each pair of descriptors is strongly correlated (Fig. 9b).

Specific to the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system, increasing Zr content initially reduces and then increases the upper limit of Dcom (Fig. 6a–c), which means lower B2 phase stability for alloys located near the central area. For elucidating this phenomenon, the distribution of key random-sublattice-based descriptors was plotted. Figure 9c shows that δmean + σVECmean varies with Zr content in a manner like the width change of high-PB2 region (PB2 ≥ 0.95), while (H/G)pbs + (δpbs/δ) exhibits the opposite trend. The larger internal disparity in sublattices (δmean + σVECmean) and weaker long-range ordering [(H/G)pbs + (δpbs/δ)] made alloys located near the center of compositional diagrams, which display more sensitive to Dcom. Moreover, at the Zr endpoint along the Dcom = 0 line, the high-PB2 region is narrower than at the Ti endpoint, likely due to the stronger sublattice ordering reflected by the higher σHmean.

As exhibited by Fig. 9d, the Fe-Co-Ni trade-off also affects B2 stability. Increasing Fe while reducing Co and Ni results in lower PB2, although variations in the Co/Ni ratio alone have minimal impact. The differences in mixing enthalpies between Fe-(Ti, Zr, Hf) and Co/Ni-(Ti, Zr, Hf) pairs are much greater than the differences in electronic structures and electronegativities of Fe and Co/Ni (Fig. 1d, e), making (H/G)pbs + (δpbs/δ) more sensitive to Fe-Co-Ni ratios than δmean + σVECmean and VEC (Fig. 9e). Additionally, increased VEC and Fe content further weakens the formation ability of single-phased B2 structure.

These trends extend to other alloy systems. The Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system follows similar PB2-descriptor relationships and element-concentration trade-offs as observed in the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system (Fig. S12). In the Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf system, excessive Cu, Zr, and Hf contents destabilize B2 line compounds due to the complexity of Cu-Zr and Cu-Hf binary systems37 (Figs. 8 and Fig. S13). Thus, not only structural disparities and chemical ordering, but also the global electronic structures jointly determine the formation of single-phased B2 structure.

Additionally, magnetism may also influence phase stability in these alloy systems. For instance, Fe2Zr and Fe2Hf Laves phases exhibit ferromagnetic (FM) behavior with Curie temperatures of ~600 K and 630 K, respectively, while Fe2Ti displays antiferromagnetic (AFM) behavior with a Néel temperature around 280 K87,88,89. Recent studies on single-phase Ti0.25Zr0.25Hf0.25Nb0.25Fe2.3 MPEIs confirmed its FM characteristics90. Similarly, many FCC high-entropy alloys composed of Fe, Co, and Ni show diverse magnetic states (FM or AFM) with composition-dependent transition temperatures91,92. In contrast, B2 intermetallic compounds such as FeTi, CoTi, and CoZr are typically paramagnetic (PM) at room temperature or exhibit Curie temperatures close to 0 K93,94,95, likely due to the absence of strong exchange interactions between magnetic atoms in the chemically ordered structure94,95. These observations suggest that chemically ordered B2 MPEIs are also likely to remain PM at room temperature and above. From a thermodynamic perspective, magnetic ordering contributes negatively to enthalpy via exchange interactions in FM and AFM phases96,97,98, but also lowers the configurational entropy relative to PM states due to spin order constraints. Such enthalpy-entropy tradeoff may influence phase stability and formation preferences in MPEIs99, particularly near magnetic transition temperatures. In this study, however, the omission of explicit magnetic descriptors did not substantially impact the predictive performance of our ML models. This may be attributed to the relatively small variation in magnetic contributions under the investigated processing conditions.

Compared with recent ML frameworks for phase prediction in complex alloys27,29, our approach offers enhanced interpretability, efficiency, and experimental rigor. Instead of relying on high-dimensional black-box models or CALPHAD-generated multi-phase datasets, we employed a physics-informed descriptor set with clear structural relevance and a lightweight ANN architecture to achieve high accuracy in predicting B2 formation. The integration of a CVAE generative model enables targeted exploration of B2-forming compositions in latent space, rather than passive brute-force scanning. Moreover, our predictions were validated not only by XRD but also by high-resolution TEM to confirm ordering and phase purity. These distinctions make our framework a more physically grounded and experimentally verifiable strategy for the design of single-phased B2 MPEIs.

After confirming the single-phase B2 structures of the ML-discovered MPEIs, we further investigated whether they exhibited Elinvar behavior (near-constant elastic modulus over specific temperature range) and high strength, similar to previously reported B2 MPEIs12,84. As illustrated in Fig. 10a, all newly discovered MPEIs exhibit Elinvar effect over the temperature range of 300–750 K. Notably, except for CoNiTiZr and (CoNi)50(TiZrHf)50, all B2 MPEIs exhibit slight elastic softening, with Co17Ni32.9Ti36.1Zr9Hf5 showing the most pronounced softening among them. Figure 10b presents the compressive mechanical properties of these alloys. In the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr alloy system, Alloy 2, with higher Fe and Zr contents, exhibits reduced yielding strength (YS) and fracture strain (FS) compared to Alloy 1. Furthermore, both alloys show lower YS than CoNiTiZr. In the Co-Ni-Ti-Zr system, Co19.9Ni30.5Ti38.1Zr11.5 containing less Co and Zr than CoNiTiZr, achieves a FS of up to 11%, accompanied by YS reduction of 70 MPa. A similar trend is observed in the Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf system, where Co17Ni32.9Ti36.1Zr9Hf5 exhibits significantly improved malleability compared to (CoNi)50(TiZrHf)50. In the Cu-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr-Hf alloy system, the CVAE-generated B2 alloy demonstrates higher YS and FS than the previously reported alloys with higher concentrations of Cu, Zr, and Hf. Except for the Fe-Co-Ni-Ti-Zr alloy system, the newly developed B2 MPEIs exhibit excellent comprehensive mechanical properties, highlighting their strong potential for further research and application.

In summary, our work introduces a generative ML framework for the rapid discovery of single-phased B2 MPEIs. By utilizing new data descriptors based on our random sublattice model and applying PCA for dataset preprocessing, we directly addressed the issue of data imbalance. The CVAE model generates potential B2 alloy compositions, which are then evaluated by the ANN model using a high PB2 criterion. The B2 compositions with high PB2 values, spanning various alloy systems, successfully form single-phased B2 structures upon experimental validation. The formation likelihood and mechanical properties of single-phased B2 structures are determined not only by structural disparity but also by the global electronic structures. Remarkably, the new single-phased B2 MPEIs demonstrate superior comprehensive mechanical properties compared to previously reported alloys. With further refinement and application of this ML framework, more MPEIs with attractive properties will be discovered in the future.

Methods

Artificial neural network (ANN) model

In this study, an ANN was employed as a surrogate model to evaluate the formation likelihood of B2 structures across diverse alloy systems. The ANN architecture, implemented using the MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox, consisted of a feedforward neural network comprising an input layer, a hidden layer with 20 neurons, and an output layer. A sigmoid activation function was applied in the hidden layer to introduce nonlinearity. The dataset was partitioned randomly into three subsets: a training set (70% of the total data), a validation set (15%), and a testing set (15%). Normalized data descriptors were used as model inputs, while the output consisted of three continuous values in the range [0, 1], representing the formation probabilities of B2, MPIM, and SS + IM structures. The predicted likelihood of B2 formation is hereafter denoted as PB2.

To enhance generalization and minimize overfitting given the relatively small dataset size, we adopted a random search strategy to tune key hyperparameters. Specifically, the following ranges were explored: optimizers (SGDM, Adam, RMSprop), initial learning rates (0.001, 0.01, 0.1), L2 regularization intensity (0.01, 0.1), and Dropout rates (0.3, 0.4, 0.5). An early stopping mechanism was employed to terminate training if the validation loss did not decrease for six consecutive evaluation steps. Considering a balance between model stability and generalization performance, we selected the RMSprop optimizer (with a learning rate of 0.1, regularization strength of 0.01, and dropout rate of 0.3) for the final model, although the highest average F-measure was obtained using the Adam optimizer under the same conditions. The combined use of dropout regularization, L2 weight decay, and early stopping effectively suppressed overfitting and improved model generalizability. Model performance was quantified using the F-measure, computed as100:

where P and R denote the precision and recall, respectively, derived from the confusion matrix, and β is a weighting parameter that adjusts the relative importance of precision over recall. For this study, β was set to 1. Additionally, the sensitivity matrix S, which evaluates the influence of input descriptors on the ANN output was calculated following established methodologies using:

where W1 and W2 represent the weight matrices for the input-to-hidden and hidden-to-output layers, respectively. This matrix provides insight into the relative importance of input features in predicting structural formation tendencies20,101.

Conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) model

To generate single-phase B2 MPEIs, we implemented a conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) model. The model was developed in Python 3.7 using TensorFlow 2.1, with a latent space dimensionality of 2. The descriptors were encoded into latent Gaussian-distributed variables by the encoder network, with the OHE labels for B2 and non-B2 phases simultaneously input as condition vectors. The sampling process from the latent space conditioned on the target label directly corresponds to the generation of alloy compositions. Specifically, by setting the condition label to 1, the model generates potential B2 compositions, while setting it to 0 produces non-B2 ones. The latent size was set to 20, and the training process was conducted with a batch size of 32 using the Adam optimizer and an initial learning rate of 0.001. The Rectified Linear Unit activation function was applied in both the input and output layers to ensure nonlinear feature representation. The loss function, floss, was defined as a weighted sum of binary cross-entropy (BCE) and Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD), which regularizes the latent space distribution:

Here, BCE ensures reconstruction fidelity, while KLD regularizes the latent space distribution toward a Gaussian prior. The model was trained using the normalized elemental concentration descriptors as inputs, generating candidate B2 compositions for subsequent ANN evaluation. To enhance generalization and mitigate overfitting—particularly important given the limited dataset size—the model design incorporated several regularization strategies: latent space regularization via the KLD term, a low-dimensional latent representation to reduce model complexity, and mini-batch training to improve convergence stability.

Alloy preparation

To validate the reliability of our physics-informed ML framework, potential B2 and non-B2 alloys were fabricated by vacuum arc melting in a Ti-gettered high-purity argon atmosphere. Raw materials with purities exceeding 99.5 wt.% were melted and subsequently remelted at least five times to ensure chemical homogeneity of the ingots. After melting, the ingots were cast into a 5 mm × 12 mm × 100 mm copper mold. Subsequently, homogenization treatments were performed on the potential B2 alloy ingots at 1273 K for 24 h in a muffle furnace.

Microstructure characterization

The crystalline structures of both the as-cast and as-annealed alloys were characterized using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with Cu-Kα radiation. Scans were performed at a rate of 2°/min over a range of 20° to 100°. Microstructural and compositional analyses were conducted using a TESCAN MIRA3 scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). SEM samples were prepared by grinding with SiC abrasive papers (grid ranging from 180 to 7000) followed by polishing with a 0.5-μm particle-size diamond polishing agent. Further microstructural analysis of the designed single-phased B2 MPEIs was performed using a JEOL JEM-F200 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operating at 200 kV, integrated with EDS. TEM specimens were prepared through mechanical thinning to an approximate thickness of 50 μm, subsequently subjected to twin-jet electropolishing using a solution of 5 vol.% HClO4 + 95 vol.% C2H6O under controlled conditions: 25 V DC at 248 K (−25 °C).

Mechanical tests

The high-temperature elastic behavior was evaluated via dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA, EG-U/HT) using rectangular bars (1 × 2.2 × 30 mm), whereas the room-temperature strength and malleability were characterized by compressive tests conducted with a Gleeble 3180 system using cylindrical specimens (Φ4 × 6 mm).

Data availability

All data used in this manuscript is available from the author on request. The codes used in this manuscript are freely available at https://github.com/ZHAO-Weijiang/MLcode-for-B2MPEI. To accelerate the feature calculation for large sets of alloy compositions, we replaced the commonly used loop algorithm with matrix multiplication and utilized MATLAB’s Parallel Computing Toolbox.

References

Tsai, M. H. & Yeh, J. W. High-entropy alloys: a critical review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2, 107–123 (2014).

Wang, H., He, Q. F. & Yang, Y. High-entropy intermetallics: from alloy design to structural and functional properties. Rare Met. 41, 1989–2001 (2022).

Firstov, G. S., Kosorukova, T. A., Koval, Y. N. & Odnosum, V. V. High entropy shape memory alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2, S499–S503 (2015).

He, Q. F. et al. A highly distorted ultraelastic chemically complex Elinvar alloy. Nature 602, 251–257 (2022).

Meng, Y. H., Duan, F. H., Pan, J. & Li, Y. Phase stability of B2-ordered ZrTiHfCuNiFe high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 111, 106515 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Lattice distortion enabling enhanced strength and plasticity in high entropy intermetallic alloy. Nat. Commun. 15, 6782 (2024).

Stolze, K., Tao, J., Von Rohr, F. O., Kong, T. & Cava, R. J. Sc-Zr-Nb-Rh-Pd and Sc-Zr-Nb-Ta-Rh-Pd high-entropy alloy superconductors on a CsCl-type lattice. Chem. Mater. 30, 906–914 (2018).

Zhou, N. et al. Single-phase high-entropy intermetallic compounds (HEICs): bridging high-entropy alloys and ceramics. Sci. Bull. 64, 856–864 (2019).

Qiao, D. et al. The mechanical and oxidation properties of novel B2-ordered Ti2ZrHf0.5VNb0.5Alx refractory high-entropy alloys. Mater. Charact. 178, 111287 (2021).

Sriharitha, R., Murty, B. S. & Kottada, R. S. Phase formation in mechanically alloyed Al xCoCrCuFeNi (x = 0.45, 1, 2.5, 5 mol) high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 32, 119–126 (2013).

Lu, Y., Yamada, J., Miyata, R., Kato, H. & Yoshimi, K. High-temperature mechanical behavior of B2-ordered Ti–Mo–Al alloys. Intermetallics 117, 106675 (2020).

Zhao, W. et al. Formation of single-phased B2 multi-principal element intermetallics: From experiments to modeling. Scr. Mater. 256, 116437 (2025).

Li, Y. & Qiang, W. Compositional effects on the antiphase boundary energies in B2-type NiTi and NiTi-based high-entropy intermetallics. Mater. Chem. Phys. 311, 128549 (2024).

Zuo, T. et al. Structural and magnetic transitions of CoFeMnNiAl high-entropy alloys caused by composition and annealing. Intermetallics 137, 107298 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Theoretical prediction of high entropy intermetallic compound phase via first principles calculations, artificial neuron network and empirical models: a case of equimolar AlTiCuCo. Phys. B Condens. Matter 646, 414275 (2022).

Muralikrishna, G. M. et al. Novel multicomponent B2-ordered aluminides: compositional design, synthesis, characterization, and thermal stability. Met. (Basel) 10, 1411 (2020).

Wang, W., Chen, H. L., Larsson, H. & Mao, H. Thermodynamic constitution of the Al–Cu–Ni system modeled by CALPHAD and ab initio methodology for designing high entropy alloys. Calphad Comput. Coupling Phase Diagr. Thermochem. 65, 346–369 (2019).

Senkov, O. N., Miller, J. D., Miracle, D. B. & Woodward, C. Accelerated exploration of multi-principal element alloys with solid solution phases. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–10 (2015).

Hu, M. et al. Recent applications of machine learning in alloy design: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 155, 100746 (2023).

Chen, Z. Q., Shang, Y. H., Liu, X. D. & Yang, Y. Accelerated discovery of eutectic compositionally complex alloys by generative machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 1–12 (2024).

Medasani, B. et al. Predicting defect behavior in B2 intermetallics by merging ab initio modeling and machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 0–1 (2016).

Yin, P. et al. Machine-learning-accelerated design of high-performance platinum intermetallic nanoparticle fuel cell catalysts. Nat. Commun. 15, 415 (2024).

Sethi, S. S. et al. Unsupervised machine learning prediction of a novel 1:3 intermetallic phase with the synthesis of TbIr3 (PuNi3-type) as experimental validation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 3, 14739–14755 (2025).

Legrain, F., Carrete, J., Van Roekeghem, A., Madsen, G. K. H. & Mingo, N. Materials screening for the discovery of new half-Heuslers: machine learning versus ab initio methods. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 625–632 (2018).

Kong, C. S. et al. Information-theoretic approach for the discovery of design rules for crystal chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 1812–1820 (2012).

Singh, P., Del Rose, T., Vazquez, G., Arroyave, R. & Mudryk, Y. Machine-learning enabled thermodynamic model for the design of new rare-earth compounds. Acta Mater. 229, 117759 (2022).

Qi, J., Hoyos, D. I. & Poon, S. J. Machine learning-based classification, interpretation, and prediction of high-entropy-alloy intermetallic phases. High. Entropy Alloy. Mater. 1, 312–326 (2023).

Senkov, O. N. et al. Mechanical properties of an Al10Nb20Ta15Ti30V5Zr20 A2/B2 refractory superalloy and its constituent phases. Acta Mater. 254, 119017 (2023).

Shargh, A. K., Stiles, C. D. & El-Awady, J. A. Deep learning accelerated phase prediction of refractory multi-principal element alloys. Acta Mater. 283, 120558 (2025).

Wang, C., Zhong, W. & Zhao, J. C. Insights on phase formation from thermodynamic calculations and machine learning of 2436 experimentally measured high entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 915, 165173 (2022).

Oñate, A. et al. Supervised machine learning-based multi-class phase prediction in high-entropy alloys using robust databases. J. Alloys Compd. 962, 2023 (2023).

Mandal, P., Choudhury, A., Mallick, A. B. & Ghosh, M. Phase prediction in high entropy alloys by various machine learning modules using thermodynamic and configurational parameters. Met. Mater. Int. 29, 38–52 (2023).

Zhou, Z., Shang, Y., Liu, X. & Yang, Y. A generative deep learning framework for inverse design of compositionally complex bulk metallic glasses. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 1–8 (2023).

Fuhr, A. S. & Sumpter, B. G. Deep generative models for materials discovery and machine learning-accelerated innovation. Front. Mater. 9, 1–13 (2022).

Kaneno, Y., Yamaguchi, T. & Takasugi, T. Texture evolution during hot-rolling and recrystallization in B2-type FeAl, NiAl and CoTi intermetallic compounds. J. Mater. Sci. 41, 6871–6880 (2006).

Otsuka, K. & Ren, X. Physical metallurgy of Ti-Ni-based shape memory alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 50, 511–678 (2005).

Massalski, T. B., Murray, J. L. & Bennet, L. H. Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams. (ASM International, Metals Park, 1986)

Villars, P., Prince, A. T. & Okamoto, H. Handbook of Ternary Alloy Phase Diagrams (ASM International, 1995).

Zhou, Z. Q. et al. Rational design of chemically complex metallic glasses by hybrid modeling guided machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 138 (2021).

Machaka, R. Machine learning-based prediction of phases in high-entropy alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 188, 110244 (2021).

Qu, N. et al. Machine learning guided phase formation prediction of high entropy alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 32, 104146 (2022).

He, Z. et al. Machine learning guided BCC or FCC phase prediction in high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 3477–3486 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Machine learning-based glass formation prediction in multicomponent alloys. Acta Mater. 201, 182–190 (2020).

Yang, X. & Zhang, Y. Prediction of high-entropy stabilized solid-solution in multi-component alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 132, 233–238 (2012).

Guo, S., Hu, Q., Ng, C. & Liu, C. T. Intermetallics more than entropy in high-entropy alloys: Forming solid solutions or amorphous phase. Intermetallics 41, 96–103 (2013).

Toda-Caraballo, I. & Rivera-Díaz-Del-Castillo, P. E. J. A criterion for the formation of high entropy alloys based on lattice distortion. Intermetallics 71, 76–87 (2016).

Laughlin, D. E. & Hono, K. Physical Metallurgy (Elsevier B.V., Oxford, 2014).

Guo, Q. et al. Predict the phase formation of high-entropy alloys by compositions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 22, 3331–3339 (2023).

Yurchenko, N., Stepanov, N. & Salishchev, G. Laves-phase formation criterion for high-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 33, 17–22 (2017).

Takasugi, T. & Yoshida, M. Transmission electron microscopy observation for activated slip systems of B2 FeTi. Philos. Mag. Lett. 72, 303–310 (1995).

Wu, W. Q. et al. Influence of high configuration entropy on damping behaviors of Ti-Zr-Hf-Ni-Co-Cu high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 153, 242–253 (2023).

Shindo, D., Yoshida, M., Lee, B. T., Takasugi, T. & Hiraga, K. High-resolution electron microscopy of dislocations in a B2-Type intermetallic compound CoTi. Intermetallics 3, 167–171 (1995).

Nakamura, M. & Sakka, Y. Compressive deformation of CoZr and (Co,Ni)Zr intermetallic compounds with B2 structure. J. Mater. Sci. 23, 4041–4048 (1988).

Yeh, J. W. Physical Metallurgy of High-Entropy Alloys. JOM 67, 2254–2261, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-015-1583-5 (2015).

Guo, S. & Liu, C. T. Phase stability in high entropy alloys: Formation of solid-solution phase or amorphous phase. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 21, 433–446 (2011).

Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y. J., Lin, J. P., Chen, G. L. & Liaw, P. K. Solid-solution phase formation rules for multi-component alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 534–538 (2008).

Ye, Y. F., Liu, C. T. & Yang, Y. A geometric model for intrinsic residual strain and phase stability in high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 94, 152–161 (2015).

Bu, Y. et al. Local chemical fluctuation mediated ductility in body-centered-cubic high-entropy alloys. Mater. Today 46, 28–34 (2021).

Lei, Z. et al. Enhanced strength and ductility in a high-entropy alloy via ordered oxygen complexes. Nature 563, 546–550 (2018).

Su, Z. et al. Enhancing the radiation tolerance of high-entropy alloys via solute-promoted chemical heterogeneities. Acta Mater 245, 118662 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Atomistic simulation of chemical short-range order in HfNbTaZr high entropy alloy based on a newly-developed interatomic potential. Mater. Des. 202, 109560 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Achieving high strength and ductility in high-entropy alloys via spinodal decomposition-induced compositional heterogeneity. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 141, 149–154 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Chemical-affinity disparity and exclusivity drive atomic segregation, short-range ordering, and cluster formation in high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 206, 116638 (2021).

Poletti, M. G. & Battezzati, L. Electronic and thermodynamic criteria for the occurrence of high entropy alloys in metallic systems. Acta Mater. 75, 297–306 (2014).

Li, Z., Li, S. & Birbilis, N. A machine learning-driven framework for the property prediction and generative design of multiple principal element alloys. Mater. Today Commun 38, 107940 (2024).

Yang, J., Manganaris, P. & Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A. Discovering novel halide perovskite alloys using multi-fidelity machine learning and genetic algorithm. J. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0182543 (2024).

Peivaste, I., Jossou, E. & Tiamiyu, A. A. Data-driven analysis and prediction of stable phases for high-entropy alloy design. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–21 (2023).

Zhu, W. et al. Phase formation prediction of high-entropy alloys: a deep learning study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 800–809 (2022).

Latypov, M. I. et al. Application of chord length distributions and principal component analysis for quantification and representation of diverse polycrystalline microstructures. Mater. Charact. 145, 671–685 (2018).

Shutaywi, M. & Kachouie, N. N. Silhouette analysis for performance evaluation in machine learning with applications to clustering. Entropy 23, 1–17 (2021).

Khoshgoftaar, T. M., Van Hulse, J. & Napolitano, A. Supervised neural network modeling: An empirical investigation into learning from imbalanced data with labeling errors. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 21, 813–830 (2010).

Pandya, M. & Valadi, J. Random Forest Classification and Regression Models for Literacy Data. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0332-8_18 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Crystallographic ordering in a series of Al-containing refractory high entropy alloys Ta–Nb–Mo–Cr–Ti–. Al. Acta Mater. 176, 123–133 (2019).

Senkov, O. N., Jensen, J. K., Pilchak, A. L., Miracle, D. B. & Fraser, H. L. Compositional variation effects on the microstructure and properties of a refractory high-entropy superalloy AlMo0.5NbTa0.5. TiZr. Mater. Des. 139, 498–511 (2018).

Jensen, J. K. et al. Characterization of the microstructure of the compositionally complex alloy Al1Mo0.5Nb1Ta0.5Ti1Zr1. Scr. Mater. 121, 1–4 (2016).

Soni, V. et al. Phase inversion in a two-phase, BCC+B2, refractory high entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 185, 89–97 (2020).

Couzinié, J. P. et al. High-temperature deformation mechanisms in a BCC+B2 refractory complex concentrated alloy. Acta Mater. 233, 117995 (2022).

Abubaker Khan, M. et al. A superb mechanical behavior of newly developed lightweight and ductile Al0.5Ti2Nb1Zr1Wx refractory high entropy alloy via nano-precipitates and dislocations induced-deformation. Mater. Des. 222, 111034 (2022).

Jin, D. M., Wang, Z. H., Li, J. F., Niu, B. & Wang, Q. Formation of coherent BCC/B2 microstructure and mechanical properties of Al–Ti–Zr–Nb–Ta–Cr/Mo light-weight refractory high-entropy alloys. Rare Met 41, 2886–2893 (2022).

Wollmershauser, J. A., Neil, C. J. & Agnew, S. R. Mechanisms of ductility in CoTi and CoZr B2 intermetallics. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 41, 1217–1229 (2010).

Mulay, R. P. & Agnew, S. R. Hard slip mechanisms in B2 CoTi. Acta Mater. 60, 1784–1794 (2012).

Hatcher, N., Kontsevoi, O. Y. & Freeman, A. J. Martensitic transformation path of NiTi. Phys. Rev. B79, 2–5 (2009).

Ezaz, T., Wang, J., Sehitoglu, H. & Maier, H. J. Plastic deformation of NiTi shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 61, 67–78 (2013).

Wang, H., He, Q. F., Wang, A. D. & Yang, Y. Tuning Elinvar effect in severely distorted single-phase high entropy alloys. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0137687 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Segregation-driven grain boundary spinodal decomposition as a pathway for phase nucleation in a high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 178, 1–9 (2019).

Kwiatkowski da Silva, A. et al. Thermodynamics of grain boundary segregation, interfacial spinodal and their relevance for nucleation during solid-solid phase transitions. Acta Mater. 168, 109–120 (2019).

Surowiec, Z., Wiertel, M., Beskrovnyi, A. I., Sarzyński, J. & Milczarek, J. J. Investigations of microscopic magnetic properties of the pseudo-binary system (Zr1-xTix)Fe2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 15, 6403–6414 (2003).

Muraoka, Y., Shiga, M. & Nakamura, Y. Magnetic properties and Mossbauer effects of Zr(Fe1-xCo x)2. J. Phys. F. Met. Phys. 9, 1889–1904 (1979).

Delyagin, N. N., Erzinkyan, A. L., Parfenova, V. P., Rozantsev, I. N. & Ryasny, G. K. Ferromagnetic-to-antiferromagnetic transition in (Hf1-xTix)Fe2 intermetallic compounds induced by geometrical frustration of the Fe(2a) sites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320, 1853–1857 (2008).

Li, J. et al. High-Entropy Magnet Enabling Distinctive Thermal Expansions in Intermetallic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c10681 (2024)

Kumari, P., Gupta, A. K., Mishra, R. K., Ahmad, M. S. & Shahi, R. R. A comprehensive review: recent progress on magnetic high entropy alloys and oxides. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 554, 169142 (2022).

Tan, Y. Y. et al. Lattice distortion and magnetic property of high entropy alloys at low temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 104, 236–243 (2022).

Yuji, A. & Hiroshi, N. Magnetic properties of TiFexCo1-x. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 35, 409–413 (1973).

Zhou, G. F. & Bakker, H. Magnetic properties of B2-structure CoZr upon ball milling. Phys. B Phys. Condens. Matter 211, 134–138 (1995).

Miracle, D. B. Overview No. 104 The physical and mechanical properties of NiAl. Acta Metall. Mater. 41, 649–684 (1993).

Bruno, P. Absence of spontaneous magnetic order at nonzero temperature in one- and two-dimensional Heisenberg and XY systems with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 3–6 (2001).

Shirakawa, K., Fukamichi, K., Kaneko, T. & Masumoto, T. Electrical resistance of Fe-Zr and Fe-Ni-Zr amorphous alloys under hydrostatic pressure. Phys. Lett. A 97, 213–216 (1983).

Shao, W., Guevara-Vela, J. M., Fernández-Caballero, A., Liu, S. & LLorca, J. Accurate prediction of the solid-state region of the Ni-Al phase diagram including configurational and vibrational entropy and magnetic effects. Acta Mater. 253, 118962 (2023).

Lin, C.-L. et al. Investigation on the thermal expansion behavior of FeCoNi and Fe30Co30Ni30Cr10-xMnx high entropy alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 271, 124907 (2021).

Lin, W. J. & Chen, J. J. Class-imbalanced classifiers for high-dimensional data. Brief. Bioinform. 14, 13–26 (2013).

Zhou, Z. et al. Machine learning guided appraisal and exploration of phase design for high entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 128 (2019).

Huang, W., Martin, P. & Zhuang, H. L. Machine-learning phase prediction of high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 169, 225–236 (2019).

Risal, S., Zhu, W., Guillen, P. & Sun, L. Improving phase prediction accuracy for high entropy alloys with Machine learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 192, 110389 (2021).

Takeuchi, A. & Akihisa, I. Classification of bulk metallic glasses by atomic size difference, heat of mixing and period of constituent elements and its application to characterization of the main alloying element. Mater. Trans. 46, 2817–2829 (2005).

Chen, C. H., Chen, Y. J. & Shen, J. J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of (TiZrHf)50(NiCoCu)50 high entropy alloys. Met. Mater. Int. 26, 617–629 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The research of YY is supported by university grants council (RGC), the Hong Kong government, through the general research fund (GRF) with the grant numbers of CityU 11201721 and CityU 11202924. The research of YL is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U20A20236).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. supervised the project and conceived the idea. Y.L. supervised the project and provided the raw materials and instruments. W.J.Z. collected the dataset, performed CVAE and ANN modeling, and carried out experiments on alloy casting, XRD, SEM, TEM and compression tests. L.W. assisted perform TEM. Z.Q.C. and Y.H.S. helped to modify the code of CVAE and ANN. B.L. provided the instruments. Q.W. performed DMA. W.J.Z. and Y.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W., Chen, Z., Shang, Y. et al. A physics-informed machine learning framework for accelerated discovery of single-phase B2 multi-principal element intermetallics. npj Comput Mater 11, 278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01775-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01775-3

This article is cited by

-

The emerging role of machine learning in nanomaterials research: applications, challenges, and future directions

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2025)