Abstract

We present large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations based on a neural network potential (NNP) to investigate alkaline wet etching of GaN, a process critical to nitride-based semiconductor fabrication. A Behler–Parrinello-type NNP is trained on extensive DFT datasets to capture chemical reactions between GaN and KOH. Using temperature-accelerated dynamics, our NNP-MD simulations accurately reproduce experimentally observed structural modifications of GaN nanorods during etching. The etching simulations reveal surface-specific morphological evolution: pyramidal pits on the −c plane, truncated pyramids on the +c plane, and planar morphologies on non-polar m and a surfaces. We also identify key chemical reactions governing the etching mechanisms. Enhanced-sampling simulations provide free-energy profiles for Ga dissolution, which critically influences the etching rate. The −c, a, and m planes exhibit moderate activation barriers, confirming their etchability, while the +c surface shows a significantly higher barrier, indicating strong resistance. We also observe the formation of Ga-O-Ga bridges on etched surfaces, which may act as carrier traps. This work provides atomistic insights into the mechanisms and kinetics of GaN wet etching, offering guidance for the fabrication of nanostructures in advanced GaN-based electronic and display applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the demand for miniaturizing GaN-based devices has been growing to support emerging display and electronic technologies. For instance1,2,3, virtual reality and augmented reality displays have become essential technologies in today’s hyper-connected society4,5. Achieving these displays requires extremely high pixel densities—exceeding 3000 ppi—to eliminate screen-door effects6, necessitating the use of submicron-size LEDs based on precisely aligned GaN micro- or nanorods5,7,8. Moreover, GaN nanowires have the potential to extend the use of nanowire-based electronics beyond typical low-power applications—such as ultra-scaled digital circuits and 5G communications—to high-power applications like power conversion9.

The fabrication method of GaN nanostructures, particularly device-integrable one-dimensional forms such as nanowires and nanorods10,11,12, are classified into top-down and bottom-up approaches. Bottom-up techniques, such as molecular-beam epitaxy and metal organic vapor phase epitaxy, are advantageous for achieving high crystal quality, including low dislocation densities and minimal lattice strain11. However, nanostructures produced through bottom-up methods often exhibit undesired chemical and structural inhomogeneities, along with atomic-scale defects due to the use of molecular precursors13. Additionally, the consistent fabrication of uniformly aligned submicron-level geometries remains challenging using bottom-up approaches14.

Top-down approaches, which integrate lithography and etching processes, hold promise as an industrial method for mass production of wafer-scale GaN nanostructure arrays with precisely controlled shapes and dimensions15. Typically, the etching process, which plays a key role in determining the shape of GaN nanostructures, consists of two steps: dry and wet etching. In dry etching, high-energy particles, such as CI2/Ar plasmas, directly bombard a pre-grown nitride film, tearing off atoms from the surface and enabling the rapid formation of GaN nanorods. However, this process can result in damaged, rough sidewalls with numerous defects, significantly degrading device performance15,16.

Following dry etching, wet etching under alkaline environments, such as KOH and tetramethylammonium hydroxide solutions, is performed to refine the shape and size of nanostructures16,17,18. During wet etching, damaged surface layers are removed through chemical reactions between the nitride and etchant solution, promoting the formation of smooth, straight sidewalls. However, while wet etching mitigates surface damage caused by prior dry etching, it can also introduce other types of surface defects17. Given the device performance based on extremely scaled GaN is highly sensitive to surface properties due to the high surface-to-volume ratio (e.g., rapid degradation of GaN micro-LEDs with decreasing LED size)19,20,21, a comprehensive understanding of GaN wet-etching processes is therefore essential for enhancing device performance.

To date, various models have been proposed to elucidate the wet-etching behavior of GaN in alkaline solutions, with particular focus on the etching resistance of different surface orientations. For example, a previous study has suggested that etching resistance increases with the density of surface Ga and N ions, because the limited empty space on the surface hinders the attack of etchants, such as hydroxyl ions (OH−), for chemical reactions22. Several groups have insisted that surfaces with a higher concentration of nitrogen ions possessing dangling bonds or lone-pair electrons are more resistant to alkaline etching because OH− ions in solution experience greater electrostatic repulsion, making it more difficult for them to approach the surface23,24,25,26. Conversely, it has also been proposed that the presence of lone-pair electrons on surface nitrogen enhances wet etching by facilitating the subsequent adsorption of H+ onto nitrogen following Ga oxidation27. While these models may help explain the etching behavior of GaN surfaces under specific experimental conditions, they provide limited insight for surface engineering in GaN-based device fabrication due to the lack of detailed chemical reaction mechanisms. Additionally, beyond etching resistance, the evolution of surface morphology and the formation of surface defects during wet etching are critical issues for industrial applications. So far, these aspects have not been thoroughly investigated.

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations based on density functional theory (DFT) have been widely employed to investigate surface chemical reactions at the atomic scale, owing to the high accuracy of DFT. However, this approach requires significant computational costs, limiting the simulation size and time. Recent advances of machine-learning potentials (MLPs), which are trained on DFT results, have offered promising alternatives to overcome the limitations of DFT28,29,30. For example, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using a Behler–Parrinello-type neutral network potential (NNP) have been employed to investigate ammonia decomposition on lithium imide surfaces, successfully explaining experimental observations and providing important insights into the catalytic reaction mechanism31. In addition, MLP-based MD simulations have been used to explore various chemical pathways for combustion of gases, gas-phase SN2 reaction, phosphoester bond formation and rupture in solution, and oxidization of Pt surface32,33,34,35.

In this work, we perform large-scale NNP-MD simulations to investigate wet etching of GaN surfaces, including two polar surfaces (+c and −c) and two non-polar surfaces (a and m), in KOH solution, which are important for various industrial applications. By training on comprehensive DFT datasets and iteratively updating model parameters, we develop a Behler–Parrinello-type NNP capable of accurately describing chemical reactions between GaN and KOH solution across a wide range of temperature and pressure conditions. To simulate the wet etching of GaN, we perform NNP-MD simulations using the temperature-accelerated dynamics (TAD) approach under elevated temperature and pressure conditions36,37, which accurately reproduces the experimentally observed structural modification of a GaN nanorod during alkaline etching. We examine the evolution of surface morphology during wet etching, which reveals that pyramidal etch pits form on the −c surface, while truncated pyramidal pits develop on the +c surface, exposing facets such as \(\{10\bar{1}\bar{1}\}\) planes. On the non-polar surfaces, etch pits grow laterally, resulting in planar etched morphologies that retain the original surface orientation. From the analysis of MD trajectories, we identify key chemical reactions that constitute the etching mechanisms of GaN surfaces. We perform enhanced-sampling MD simulations for Ga dissolution on each surface, a critical step in determining the etching rate, constructing the corresponding free-energy profiles under realistic etching conditions. The results show that the −c, a, and m planes exhibit moderate activation energies, highlighting high feasibility of wet etching. In contrast, the +c plane yields a prohibitively high energy barrier, indicating the difficulty of its alkaline etching. We also demonstrate that Ga-O-Ga bridges, which would serve as surface defects detrimental to device performance, can form on etched surfaces of GaN.

Results

Training neural network potential

To develop a NNP capable of simulating the wet etching of various GaN crystal surfaces, including the +c, −c, a, and m planes, it is essential to construct a comprehensive training set that encompasses not only the bulk properties of GaN and alkaline solutions but also a wide range of relevant chemical reactions at their interface. However, due to the immense computational cost, it is infeasible to identify all possible chemical reactions exhaustively. To address this challenge, we first construct a baseline NNP model from a primary training set and subsequently refine it through iterative updates of model parameters, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Primary training dataset

Table 1 provides an overview of the primary training dataset, which is categorized into three components: bulk structures, reaction products, and GaN/solution interfaces. We sample training data from MD simulations, as described below, using constant time intervals: longer intervals (150–200 fs) for reaction products, which include high-energy structures that enhance MD stability by expanding the training domain38,39, and a shorter interval of 30 fs for bulk systems and GaN/solution interfaces to more thoroughly capture chemical processes directly relevant to alkaline wet etching.

(1) Bulks: For GaN, the training data include configurations from wurtzite crystal, amorphous, and liquid phases, as illustrated in Figure 1a. To capture diverse local geometries, MD simulations are conducted across various temperatures. Specifically, for the crystal phase, we prepare a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell of a perfect wurtzite GaN crystal, along with supercells containing either Ga or N vacancies. Trajectories for each supercell are sampled from NVT MD simulations performed at 1500 K for 3 ps. For the liquid phase, 40 Ga and 40 N atoms are initially distributed randomly within a supercell with the volume corresponding to the experimental crystal density of GaN (6.15 g/cm3). The structure is first premelted using NVT MD simulations at 4000 K, above the melting point of GaN, without sampling. Subsequently, the liquid is simulated at 3000 K for 10 ps, during which configurations are sampled for the training set. To obtain amorphous configurations, the liquid structure is quenched to 300 K at a rate of 150 K/ps and then annealed for 4 ps at 300 K. Configurations are sampled during the quenching and annealing steps.

For KOH solutions, we generate a supercell containing 4 KOH and 50 H2O molecules, corresponding to a 4 M molar concentration under ambient conditions (1 bar and 350 K). The in-plane lattice parameters are fixed to match a 3 × 2 extension of the GaN m-plane lattice, enabling seamless integration with subsequent GaN/solution interface simulations, while the z component is allowed to relax. We conduct NPT MD simulations for 8 ps across a broad range of pressures (1 bar and 100 kbar) and temperatures (350, 600, and 2000 K). The high-pressure (100 kbar) and high-temperature (2000 K) conditions are considered to reflect those used in etching simulations based on the TAD approach (see the Methods section for details on the etching simulation). Snapshots from these simulations are sampled to construct the training set. On the other hand, due to the finite size of the supercell, its volume fluctuates to some extent during NPT simulations, leading to variations in solute concentration between 3 M and 7 M. To sample molecular configurations at a consistent concentration, we also perform NVT simulations, setting the z lattice parameter to the time-averaged value obtained from the NPT simulation. We confirm that the time-averaged z lattice at 1 bar and 350 K leads to a solution concentration of 4 M, aligning with experimental results. It is worth noting that, although the high pressure and temperature conditions for etching simulations drive the solution into a supercritical state, the density of the solution (1.57 g/cm3) is close to that of a liquid state at 1 bar and 350 K (1.18 g/cm3). Nonetheless, the supercritical water differs from the ambient tental conditions. However, it may accelerate the etching rates on different surfaces to varying extents. Second, radical species such as neutral H and OH have been experimentally observed in supercritical water40,41. While such species could, in principle, affect the etching process, they are not generated in our closed-shell AIMD simulations, which are restricted to ground-state electronic configurations. Consequently, our simulations primarily describe solution species relevant to alkaline etching under experimental conditions, such as H2O, K+, and OH−.

(2) Reaction products: To sample aqueous molecular configurations of potential byproducts formed during alkaline wet etching, we perform NVT MD simulations. The types and amounts of elements initially included in each supercell are determined considering five chemical reactions between GaN and aqueous solutions with or without KOH, targeting specific byproducts (see detailed procedure in Section S2.1 in the Supplementary Information). Moreover, we additionally sample configurations of [Ga(OH)4]− and NH3 in KOH solution, because these species are thermodynamically more favorable and are therefore expected to form more readily during wet etching compared to other byproducts.

(3) GaN/solution interface: To generate atomic configurations at the GaN/solution interface for the primary training set, we focus on the m plane, as its surface structure is more complex than those of the other planes (such as a and ± c surfaces). This structural complexity allows for the generation of diverse local environments during MD simulations, potentially covering the structural characteristics of the other planes to some extent. The m plane exhibits a bilayer structure: Ga and N ions in the top layer possess a single dangling bond, whereas those in the sublayer have two dangling bonds upon cleavage (Fig. 1d). The interface model consists of a GaN slab, with either the top layer or sublayer exposed, in contact with an alkaline solution containing 4 KOH and 50 H2O molecules. Prior to the MD simulations, Ga and N dangling bonds exposed to the solution are passivated with OH and H species, respectively—a process that occurs spontaneously in water due to the energetic instability of the dangling bonds42. We sample trajectories associated with Ga and N dissolution from NVT MD simulations performed for 5 ps at 100 kbar and elevated temperatures (2700 K and 3000 K for the top-layer model and 2000 K for the sublayer model). The use of the lower temperature for the sublayer model reflects its higher reactivity, and therefore, a faster etching rate. During these simulations, the in-plane lattice parameters of the interface models are set to those of the GaN slab, considering the rigidity of the GaN lattice. The z component is determined as the time-averaged value obtained from the last 3 ps of the preceding NPT MD simulation (see Section S2.2, Supplementary Information, for details).

Iterative learning

To assess the training quality, we divide the primary dataset into training and validation sets in a 9:1 ratio. The baseline NNP achieves reasonably low root-mean-square errors (RMSEs): 7.86 meV/atom for energy, 0.31 eV/Å for force, and 12.26 kbar for stress on the training set, and 8.10 meV/atom, 0.33 eV/Å and 12.82 kbar, respectively, on the validation set. We further validate the accuracy and MD stability of the baseline NNP, by comparing its predictions with DFT results for interface properties and etching behavior of the GaN surfaces. To this end, we perform NNP-MD etching simulations on polar (+c and −c plane) and non-polar (m and a plane) surfaces within the TAD approach at 2000 K and 100 kbar. To ensure the feasibility of DFT calculations, the simulation cell size is restricted to include ~300 atoms. The supercells are constructed such that only the upper surface of the GaN slab interacts with the solution, while the bottom surface remains unreactive (details on the passivation of the bottom surface are provided in Section S3.1, Supplementary Information). Etching simulations are terminated once a single GaN layer (a bilayer in the case of m surface) completely dissolves, as shown in Fig. 2a for the m surface.

a Structural snapshots showing the progression of wet etching on the GaN m plane, from the pristine surface to a state with one bilayer removed, obtained from a 150 ps molecular dynamics simulation at 2000 K and 100 kbar. b Temporal evolution of atomic energies calculated by the NNP and DFT. c Parity plot of reaction energies comparing NNP predictions with DFT calculations. The snapshots used in (b) and (c) were selected from the etching trajectory using a graph-based filtering method.

Subsequently, we evaluate DFT energies for selected snapshots to estimate the prediction errors of the baseline NNP. Since etching involves chemical reactions that reorganize chemical bonds, it is crucial for NNP to accurately describe the reaction energy, i.e, the energy difference before and after chemical-bond reorganization. Hence, we identify reaction moments by analyzing the MD trajectories using a graph-based analysis (Fig. S3) and select snapshots before and after the chemical reactions for error estimation. This test reveals that the baseline NNP exhibits substantial energy errors for specific configurations, which significantly overestimate the validation RMSE, indicating that local configurations encountered during etching simulations are occasionally not well represented by the primary training set. The worst case appears for the −c plane, where the maximum error exceeds 1000 meV/atom (Fig. S4). To address these large errors (greater than 30 meV/atom), we add the corresponding snapshots to the training set and retrain the model. After three iterations of this refinement process, the updated NNP model consistently generates MD trajectories without notable energy deviations from DFT reference values, as shown in Fig. 2b. In the tests for each GaN plane, the energy RMSE was reduced to below 22 meV/atom (Table S2), which is comparable to the validation energy RMSE of 15.35 meV/atom, indicating that the model is sufficiently accurate to describe the etching process. As a note, we decompose the validation RMSEs according to the sampling categories presented in Table 1, as summarized in Table S3. This analysis shows that the overall validation RMSE is predominantly influenced by errors associated with structurally and chemically complex systems, such as interfaces and reactive species. In contrast, the RMSEs for simple bulk systems remain notably low, consistent with those reported in previous studies focused on bulk materials43.

It is worth noting that the iteratively trained NNP accurately reproduces DFT reaction energies, yielding a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.95 for their correlation (Fig. 2c). This underlines the reliability of the model for etching simulations. In addition to the reduction of energy errors, the iterative learning process significantly decreases force errors, thereby enabling stable MD simulations of the etching process (Fig. S5). The validation RMSE of the updated NNP model is 15.32 meV/atom for energy and 0.37 eV/Å for force. These accuracy levels are on par with those reported in previous studies (18 meV/atom and 0.64 eV/Å)44, which investigated complex and aggressive chemical reactions during dry etching.

The precision of the iteratively refined NNP is thoroughly validated for various fundamental properties of bulk GaN and KOH solutions, such as bulk moduli, equation of state, and diffusivity (see Sections S4.1 and S4.2 in Supplementary Information for details). Additionally, we confirm that the NNP accurately captures molecular arrangements at the GaN/solution interface. For example, MD simulations at 1 bar and 300 K show the accumulation of H2O molecules near the interface, with their O ions oriented toward H ions on the GaN surface, forming hydrogen bonds (Fig. S8). Furthermore, both the density and orientational distribution of water molecules gradually recover those of the bulk with increasing distance from the interface.

Note that long-range electrostatic interactions are usually not fully captured in NNP methods, although the alignment of water molecules on the GaN surface in Fig. S8 suggests that such interactions is partially incorporated, particularly within the cutoff radius used in atomic descriptors45,46,47. To assess the impact of this limitation, we explicitly examine the electrostatic potential distributions at the GaN/solution interface model obtained from our NNP-MD simulation. As shown in Fig. S9, the NNP approach yields configurations that reproduce electrostatic potential profiles closely matching those from the DFT method, thereby validating its applicability. The relatively minor influence of the incomplete treatment of long-range interactions can be attributed to the strong dielectric screening provided by the aqueous solution. In contrast, in systems with weak screening or strong electrostatic interactions, such as charged gases48 or ionic liquids49, this limitation may lead to substantial inaccuracies in NNP simulations.

In addition to our iterative learning approach, uncertainty estimation using ensemble NNPs has been employed to sample structures outside the training domain50,51. In this approach, the adoption of an NNP committee allows for atom-resolved error estimation52. However, compared to our method, this approach may demand greater computational resources, as it requires generating multiple NNP models at each training set update. Moreover, our method enables more direct error quantification by explicitly comparing NNP predictions with DFT reference values.

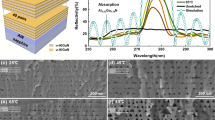

Structural modification of GaN nanorod by alkaline etching

To demonstrate the accuracy of etching simulations based on the refined NNP, we examine the structural evolution of a GaN nanorod under alkaline etching. The NPT MD simulation is carried out for 600 ps using the TAD approach at 2000 K and 100 kbar, with the solution pH set to 14. The height of the nanorod is maintained by fixing the z-axis during the simulation. The GaN nanorod model, consisting of ~50,000 atoms, initially adopts a truncated-pyramid structure (Fig. 3), exposing the a and r planes on its sidewalls. As etching proceeds, the slope of the original rod gradually disappears, and the structure evolves into a hexagonal shape with relatively flat sidewalls dominated by the m plane, which exhibits a slower etching rate compared to the a and r planes. The simulation results align well with previous experiments, in which slanted nanorods formed by dry etching gradually transform into a hexagonal shape, exposing the m plane during alkaline wet etching10,11,14,53. This underscores the capability of the accelerated NNP-MD approach adopted in this study to accurately simulate the wet etching process.

Morphologies of etched surfaces

In this section, we discuss the morphologies of etched surfaces that are generated from MD simulations leveraging the refined NNP within the TAD approach. The GaN/solution interface models contain thousands of atoms, including about 1000 GaN formula units. The solution models are constructed to exhibit a pH of ~14. The specific information about the supercell models are shown in Table S3. Prior to MD simulations, Ga and N dangling bonds of pristine surface models are passivated with OH and H species, respectively. All models are initially equilibrated for 100 ps at 20 kbar and 1000 K. Etching simulations are then carried out at 100 kbar and 2000 K for several hundred picoseconds.

Polar surfaces

We first discuss the −c plane, for which surface morphologies formed by wet etching have been extensively studied in experiments54,55. The slab model for the −c plane prior to etching is shown in Fig. 4a. Figure 4b depicts the cumulative number of the major etching products, [Ga(OH)4]− and NH3, as a function of time. At the beginning of the simulation, Ga and N ions on the surface are progressively decorated with OH− and H+, respectively, with negligible formation of the etching products. Once Ga and N dissolution begins at certain surface sites, nearby surface ions become destabilized due to the loss of Ga-N bonds, thereby accelerating the etching process. As a note, in the alkaline solution, the main source of H+ ions is H2O, which can dissociate into H+ and OH− at the interface. Upon H2O dissociation, H+ adsorbs onto a surface N ion, while the OH− ion mostly diffuses into the solution. Interestingly, N dissolution proceeds at a rate comparable to that of Ga dissolution, even in the alkaline solution where protons are scarce. This behavior is attributed to the higher positions of N ions relative to Ga ions, which enhances the accessibility of H2O to N ions, partially compensating for the limited availability of H+ ions in the alkaline environment.

a–e the −c plane and f–j the +c plane. a, f Atomic structures of the pristine −c and +c surfaces. b, g Cumulative number of dissolved species over time for the −c and +c surfaces. c, d, h, i Representative oxygen bridge structures and their areal densities at time t for the −c and +c surfaces, respectively. e, j Temporal evolution of etched morphologies for the −c and +c surfaces.

While the etching proceeds, we occasionally observe the formation of Ga-O-Ga bridges (Fig. 4c) as intermediates, as shown in Fig. 4d. These configurations are contained in our training dataset and are accurately described by the NNP (Fig. S10). The Ga-O-Ga units are formed when an OH− ion replaces a N ion during N dissolution. This is followed by the removal of an H+ ion through a reaction with a neighboring OH− ion, resulting in the formation of H2O. Note that the formation of oxygen bridges is not a prerequisite for N dissolution, as inferred by their low areal density during the etching (Fig. 4d). However, once formed, they can persist for a long period. The thermodynamic stability of oxygen bridges and their influence on the etching rate will be discussed in detail later.

The temporal evolution of the surface morphology of the −c plane is illustrated in Fig. 4e. Initially, pyramidal etch pits form at several locations on the surface. These pits then undergo lateral expansion along specific directions, such as \(\langle 11\bar{2}0\rangle\) and \(\langle 1\bar{1}00\rangle\), leading to their widening. Following a short period of lateral etching that exposes atomic configurations resembling those of the initial surface, vertical etching proceeds concurrently, resulting in the formation of deeper pits. Consequently, the etch pits grow three-dimensionally over time, while retaining their characteristic pyramidal shape. Considering the directions of the lateral and vertical etching, the exposed surfaces in etch pits are close to the \(\{10\bar{1}\bar{1}\}\) plane. This observation aligns with experimental studies23,25,26.

Figure 4f shows the surface model of the +c plane used for the etching simulation. Unlike the −c plane, preferential dissolution of Ga ions is pronounced (Fig. 4g), because N ions are positioned below Ga ions. As etching progresses, Ga-O-Ga bridges are formed (Fig. 4h, i). Two distinct configurations of these bridges are observed: (1) a Ga–ON–Ga bridge, in which an O ion occupies a N site, linking the upper and lower Ga ions, and (2) a Ga–Oint–Ga bridge, where an O ion resides at an interstitial site between two surface Ga ions. The latter configuration, which does not require N dissolution, can form even during the pre-equilibration step, leading to a finite number of Ga-O-Ga bonds at t = 0 (Fig. 4i). Similar to the −c plane, etch pits on the +c plane initially expand laterally. Although etching in the vertical \(\langle 000\bar{1}\rangle\) direction is observed, it is less pronounced than that of the −c plane (Fig. 4j). As a result, the surface morphology after wet etching is expected to resemble a truncated pyramid. To the best of our knowledge, there are no experimental reports on the morphologies of etched +c surfaces in alkaline solutions, likely due to the difficulty of etching at typical process temperatures of 50–90 ∘C23,24. Further experimental studies at elevated temperatures are needed to validate our prediction on the morphology of etched +c surfaces.

Non-polar surfaces

The etching simulation for the m plane begins with the atomic model illustrated in Fig. 5a. It is clearly seen in Fig. 5b that Ga dissolution occurs first, followed by N dissolution, despite surface Ga and N ions being located at the same height. This behavior can be attributed to the abundance of OH− ions in the alkaline solution, which promotes the formation of [Ga(OH)4]−. Furthermore, N dissolution on the m plane would be further delayed because each surface N ion has only a single nearest Ga neighbor in the top layer. This limited coordination with Ga is ineffective for top-layer N ions to increase N-H bonds upon the dissolution of top-layer Ga ions, thereby slowing down the formation of NH3. In the following section on mechanistic analysis, we will provide a more detailed discussion of the N-H bond formation process.

a–e the m plane and f–j the a plane. a, f Atomic structures of the pristine m and a surfaces. b, g Cumulative number of dissolved species over time for the m and a surfaces. c, d; h, i Representative oxygen bridge structures and their areal densities at time t for the m and a surfaces, respectively. e, j Temporal evolution of etched morphologies for the m and a surfaces.

During the wet etching process, Ga-O-Ga bridges are observed, as seen on the polar surfaces. Two Ga–ON–Ga and one Ga–Oint–Ga configurations are identified, as depicted in Fig. 5c. Between the Ga–ON–Ga configurations, one involves an O ion replacing a N ion at the top surface (N_t), and thus, the oxygen connects two sublayer Ga ions (Ga_s). In the other configuration, an oxygen ion occupies a N site in the sublayer (N_s), forming a bridge between a top-layer Ga (Ga_t) ion and a sublayer Ga ion (Ga_s). On the other hand, oxygen can occupy an atomic site between two top-layer Ga ions (Ga_t), producing a Ga–Oint–Ga configuration. A finite number of Ga–Oint–Ga configurations, which do not involve N dissolution processes, keeps observed throughout the etching simulation even at t = 0. In contrast, Ga-ON-Ga configurations emerge after N dissolution takes place.

Figure 5e depicts the morphological evolution of the m plane during the wet etching. Etch pits initially form at several locations on the surface due to the dissolution of Ga_t and N_t ions. These pits preferentially grow linearly along the \(\langle 11\bar{2}0\rangle\) direction. Over time, the pits extend further along the 〈0001〉 direction as Ga_s and N_s ions dissolve in addition to Ga_t and N_t ions. Notably, etching in the downward direction does not happen during the lateral growth of the etch pits, highlighting the highly anisotropic nature of wet etching of the m plane. Consequently, the etched surface adopts a planar morphology while retaining the surface orientation of the m plane. These simulation results are consistent with experimental observations, which reported that wet etching of the m plane produces a planar surface morphology rather than a pyramidal one, preserving the original surface orientation16,56.

The initial atomic structure of the a plane before wet etching is shown in Fig. 5f. Similar to the m plane, Ga ions on the a plane dissolve first, followed by dissolution of N ions (Fig. 5g). However, N dissolution on the a plane occurs more rapidly than that on the m plane. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that N ions on the a plane are bonded to two surface Ga ions, unlike those on the m plane. As a result, it is more feasible for surface N ions to increase N-H bonds following the dissolution of surface Ga ions. Intermediate Ga-O-Ga bridges are observed during the etching of the a plane, as shown in Fig. 5h, i. These bridges adopt a Ga–ON–Ga configuration, where an oxygen ion replaces a nitrogen site, bridging a Ga ion exposed to the solution with an underlying Ga ion.

The morphology and growth patterns of the etched surface of the a plane are similar to those of the m plane. During the initial stages of etching, etch pits are generated on the surface through the dissolution of Ga and N ions exposed to the solution, as shown in Fig. 5j. These pits first extend along the 〈0001〉 direction. Subsequently, they grow along the \(\langle 1\bar{1}00\rangle\) direction without notable vertical growth. As a result, the etched surfaces retain planar morphologies, preserving the original surface orientation. These findings align with previous experimental reports16,56.

Based on the foregoing discussions, the temporal evolution of etched surfaces on both polar and non-polar GaN planes is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Etching mechanism

Through detailed analysis of the MD trajectories, we identify key etching processes that commonly occur across all GaN surface orientations (Fig. 7). First, the OH− adsorption onto a Ga ion, which initiates the etching process, causes a significant upward displacement of the Ga ion due to the attractive interaction between the attached OH− ions and the Ga ion (Fig. 7a). This structural distortion progressively weakens the Ga-N bonds on the surface as the number of attached OH− ions increases. Consequently, one of the Ga-N bonds breaks, leading to an electron lone-pair on the N ion. In subsequent reactions, this lone-pair state is passivated by a H+ ion.

a Adsorption of OH− leading to Ga-N bond breaking, b Ga dissolution, c N dissolution with and d without the formation of Ga-O-Ga bridges, and e Ga-N bond breaking facilitated by proton transfer from -NH2 species. In a–e, reaction products and adsorbates are highlighted in blue. VGa denotes a Ga vacancy.

Second, as shown in Fig. 7b, Ga dissolution, which requires the consecutive breaking of Ga-N bonds, leaves behind -NH or -NH2 species near Ga vacancy sites. The -NH2 species can be converted into NH3 in the next step, leading to N dissolution. There are two pathways for N dissolution. The first one involves the formation of a Ga-O-Ga bridge (Fig. 7c). Specifically, the attack of OH− on a Ga ion bonded to the -NH2 species results in the formation of a Ga-OH bond. This subsequently breaks the Ga-N bond, leading to the immediate protonation of the -NH2 via the dissociation of an incoming H2O molecule. Once the NH3 molecule dissolves, the remaining nitrogen vacancy is occupied by the attached OH− ion, forming a bridge with a nearby Ga ion. Afterward, the hydrogen ion of the bridging OH− is dissociated through a reaction with another OH− ion in the solution, producing H2O. On the other hand, if breaking the Ga-NH2 bond is energetically unfavorable, further Ga dissolution occurs first, and NH3 spontaneously dissolves, as shown in Fig. 7d. Between these two pathways for N dissolution, the latter, which proceeds without the formation of an oxygen bridge, occurs more frequently. Nonetheless, a moderate amount of oxygen bridges is expected to be present on the etched surface due to their kinetic stability, which will be discussed later.

Third, -NH2 species can serve as a proton carrier, facilitating proton transfer to a underlying N ion that is otherwise difficult to gain a proton directly from a H2O molecule (Fig. 7e). Once this transfer occurs, the reverse reaction, namely the separation of Ga and OH−, becomes energetically unfavorable. As a result, the Ga-OH bonds can be sustained for a long duration, thereby promoting the dissolution of Ga ions.

In the following, we present free-energy profiles for Ga dissolution along with associated structural changes and chemical reactions on each surface. As discussed in Section 2.2, the onset of GaN etching is delayed until the dissolution of several Ga ions occurs. This underscores the critical role of Ga removal from the pristine surface, a process that recurs throughout wet etching, in determining the overall etching rate. The free-energy profiles are obtained as a function of the path-collective variable [σ(z)] via On-the-fly probability enhanced sampling (OPES) simulations at 1 bar and 350 K, corresponding to experimental pressure and temperature conditions. The reference path in Fig. 8 is initially constructed by guiding the system to sequentially break the Ga-N bonds of a target surface Ga atom, which is represented as discrete integers in the collective variable σ(z). The detailed procedure for the OPES calculations is provided in the Methods section.

a Free energy surfaces comparing Ga dissolution pathways on polar surfaces (−c and +c planes). The corresponding structural evolutions are shown in b for the −c plane and in c for the +c plane. d Free energy surfaces comparing Ga dissolution pathways on polar surfaces (m and a planes). The corresponding structural evolutions are shown in e for the m plane and in f for the a plane. g Comparison of free energy surfaces for Ga-N bond breaking in the presence of Ga–ON–Ga and Ga–NH2–Ga motifs. The corresponding pathways are shown in (h) and (i), respectively. j Free energy surface corresponding to the removal of a Ga–ON–Ga bridge, with k depicting the associated structural change. In the structural models, reaction products and adsorbates are highlighted in blue, and atoms occluded by others are rendered with reduced opacity. In c, pre-adsorbed OH− on Ga ions that assists in breaking the Ga-N bond are highlighted in orange.

Ga dissolution on polar surfaces

Figure 8a shows free-energy diagrams of the Ga dissolution pathways on the polar surfaces. On the −c surface, Ga ions lie below -NH units and have four Ga-N bonds, all of which must be broken for Ga dissolution to occur. The absence of exposed Ga-OH species, which could otherwise impede the approach of aqueous OH− ions to the surface, allows a underlying Ga ion to form a Ga-OH bond (i → ii in Fig. 8b), with a moderate reaction energy barrier of ~0.8 eV. This process results in an upward shift of the Ga ion, breaking one Ga-N bond. The subsequent step for breaking another Ga-N bond involves the OH− adsorption and the H+ passivation of electron lone-pairs on two N ions (ii → iii). It should be noted that, during this step, a proton transfer from the NH2 unit to the lower-lying N ion plays an important role in the H+ passivation. This step leads to an energy barrier of ~0.8 eV. On the other hand, the breaking of the remaining two Ga-N bonds (iii → iv and iv → v) and the formation of [Ga(OH)4]− proceeds with much smaller energy barriers below ~0.2 eV.

Unlike the −c surface, the initial adsorption of aqueous OH− to Ga ions on the +c surface is expected to be hindered by Coulomb repulsion between an incoming OH− ion and pre-adsorbed OH− species. Indeed, our OPES simulations reveals an alternative pathway for Ga dissolution that is not initiated by the adsorption of aqueous OH−. Specifically, the initial upward shift of a Ga ion occurs through the formation of Ga-OH-Ga bonds, involving preexisting OH− ions bound to neighboring Ga ions (i → ii in Fig. 8c). This is followed by protonation of the exposed lone-pair states on adjacent N ions (ii → iii). However, these steps cause a substantial energy barrier of ~2.8 eV, because surface Ga ions are tightly bound to three underlying N ions, significantly restricting their upward displacement. Compared to the first two steps, the subsequent reactions, breaking a single Ga-N bond (iii → iv) and two Ga-OH bonds (iv → v), proceed with relatively small energy barriers.

Overall, our results highlight the relatively high etchability of the −c surface in alkaline environments under typical experimental conditions, whereas the +c surface exhibits significant resistance to etching—consistent with experimental observations23,24.

Ga dissolution on nonpolar surfaces

Figure 8d illustrates the free-energy profiles for Ga dissolution pathways on the non-polar surfaces. On the m plane, the initial OH− adsorption (i → ii in Fig. 8e) is feasible, requiring a small energy barrier of ~0.3 eV. However, this process is insufficient to break Ga-N bonds. Additional OH− adsorption leads to the breaking of two Ga-N bonds (ii → iii), with an energy barrier of ~1.2 eV. During this step, one of the resulting N lone-pair states is immediately passivated by a proton. The proton passivation of the remaining lone-pair state occurs next (iii → iv), following a benign reaction pathway. Further adsorption of OH− onto the dissolving Ga ion leads to its dissociation from the surface (iv → v), with a small energy barrier of ~0.2 eV.

On the a plane, the initial two steps of Ga dissolution are analogous to those on the m plane: two consecutive OH− adsorption events expose a lone-pair state on a N ion by breaking a Ga-N bond, which is passivated by a proton (i → ii and ii → iii in Fig. 8f). However, in this case, the energy barrier associated with the bond breaking is relatively lower than that on the m plane, as only a single Ga-N bond is broken during this stage. Instead, the a plane exhibits a higher energy barrier (~0.4 eV) in the subsequent [Ga(OH)4]− desorption step (iii → iv), which involves additional OH− adsorption and immediate passivation of the resulting N lone-pair state.

The effective activation energy of the pathways, corresponding to the difference between the highest and lowest energies, is found to be 1.5 eV for the m plane and 1.4 eV for the a plane. These values are comparable to that of the −c plane, confirming the etchability of these non-polar surfaces in alkaline solutions. In addition, experimental results show that wet etching of the m plane is slightly slower than, or comparable to, that of the a plane11, consistent with the comparable activation energies predicted by our simulations.

Role of oxygen bridges

As we demonstrated above, oxygen bridges form intermittently during the etching process. In the case of oxygen bridges involving Oint, the bridges can be dissociated through reactions with H2O and OH−, effectively resulting in a structure equivalent to that formed by the adsorption of two OH− ions (Fig. S11). According to our MD simulations, this process readily occurs.

Conversely, oxygen bridges in which an O ion occupies a N site can remain persist for a longer duration. Figure 8g presents the free-energy profile for the initial steps of Ga dissolution within a Ga–ON–Ga bridge on the m plane. Interestingly, the Ga-O-Ga bonds are maintained even when a bridged Ga ion is attacked by OH−; instead, the reaction favors breaking a Ga-N bond. This leads to the formation of a lone-pair electron state on a N ion, which is subsequently passivated by a proton (see Fig. 8h). This pathway exhibits a substantial activation energy of ~1.9 eV, indicating slow reaction kinetics. In contrast, Ga ions that lose neighboring N ions without forming oxygen bridges can readily coordinate with OH− (Fig. 8i). This pathway results in a smaller energy barrier of ~0.6 eV and is thus expected to proceed rapidly.

In light of the results presented in Fig. 8g, the dissolution of Ga ions around a Ga–ON–Ga bridge is likely to occur before OH− adsorption onto the bridged Ga ions. During the dissolution of such neighboring Ga ions, N ions connected to Ga-O-Ga bridges can acquire protons, thereby weakening their chemical bonds with the bridged Ga ions. As a result, subsequent OH− adsorption onto the bridged Ga ions becomes more feasible, leading to Ga-O-Ga configurations that are only weakly connected to the surface, as illustrated in Fig. 8k. These configurations are indeed frequently found in our etching simulations. The following generation of [Ga(OH)4]− can efficiently proceed with a low activation energy of ~0.5eV (see Fig. 8j), eliminating the oxygen bridges. Note that the conclusions drawn from this analysis on the m plane are also applicable to the other surfaces, considering the results of the corresponding etching simulations.

As noted in Section 2.2, the concentration of oxygen bridges formed during wet etching is not significant, suggesting a limited impact on the overall etching rate. However, since the removal of each oxygen bridge is delayed until the dissolution of neighboring Ga and N ions, these configurations are likely to be present on the surface after alkaline etching. Notably, previous studies have demonstrated that substitutional oxygen in GaN can form critical defect complexes that enhance non-radiative recombination of charge carriers57,58. In this context, the role of Ga–ON–Ga bridges, likely formed on the sidewalls of GaN nanorods during wet etching, requires further investigation through both experimental and theoretical studies.

Discussion

We presented a comprehensive atomic-level investigation of GaN wet etching in KOH solution using large-scale NNP-MD simulations. By using an iterative learning strategy, we developed a Behler–Parrinello-type NNP with a high capability to describe chemical reactions associated with the alkaline etching of GaN surfaces. We showed that the NNP-MD simulations accurately reproduce the structural modification of GaN nanorods observed in experiments. The etching simulations revealed the morphologies of etched surfaces: pyramidal pits form on the −c surface, while truncated pyramidal pits develop on the +c surface. The non-polar (a and m) surfaces exhibit highly anisotropic lateral etch propagation, resulting in planar etched morphologies. Key surface reactions involved in etching were identified through atomic trajectory analysis, and OPES simulations provided free-energy profiles for Ga dissolution, a process critical to the etching kinetics. The moderate activation barriers observed on the −c, a, and m planes indicate their high etchability, whereas the significantly higher barrier on the +c plane accounts for its etch resistance. Additionally, we showed that Ga-O-Ga bridges can be present on etched surfaces, which may deteriorate the optoelectronic performance of GaN-based devices. The detailed insights from our study advance the fundamental understanding of GaN surface chemistry during alkaline etching and support the rational design of surface processes in nitride-based device fabrication.

From a computational perspective, although the current NNP method does not fully account for long-range interactions, which can be important for describing reactive solutions, more advanced MLPs capable of rigorously treating long-range electrostatics have been developed49,59,60,61. These approaches enable more reliable simulations and broaden the accessible range of chemical environments and system conditions. In addition, several state-of-the-art MLP models based on equivariant message-passing graph neural networks—such as MACE, NequIP, and SevenNet—have demonstrated higher accuracy and broader configurational coverage compared to traditional NNPs62,63,64 We indeed observe that the SevenNet model trained on the primary training set achieves generally higher accuracy, as evidenced by the results in Table S6 and Fig. S17. Nonetheless, both the SevenNet and BP-NNP models accurately reproduce the DFT reference data, suggesting that the underlying etching mechanisms are consistently captured by both approaches. Furthermore, as with our NNP model, these more advanced architectures may still exhibit significant errors when applied to configurations outside their training domain, as illustrated in Table S6. This underscores the importance of rigorous model validation and iterative refinement, particularly in chemically complex or reactive environments.

Methods

Neural network potential

We build a Behler–Parrinello-type NNP trained with the SIMPLE-NN package65,66. Atom-centered symmetry functions (ACSFs) are used as input features, with a cutoff radius of 6 Å for Ga, N, K, and O and 4.5 Å for H. The feature vector for each element initially contains 310 components. To enhance the training and inference efficiency of the NNP, we reduce the size of the feature vectors by applying CUR decomposition (see Section S1 Supporting Information for details). As a result, the final feature vector sizes become 145, 141, 51, 153, and 151 components for Ga, N, K, H, and O, respectively. Specific parameters for ACSFs are summarized in Table S1 in Supporting Information.

The feature vectors are scaled using the maximum and minimum values. To speed up the learning process, we apply principal component analysis to the feature vectors and whitening them. We employ a fully-connected neural network architecture consisting of two 30-30 hidden layers. The dataset is split into 90% for training and 10% for validation. Training is conducted in two stages: an initial stage for generating a baseline model and an iterative stage for model refinement44. In the initial stage, we use a learning rate of 10−4 and a batch size of 4. In the iterative stage, these parameters are adjusted to 10−5 and 8, respectively. The Adam optimizer is used for optimization.

DFT calculations

We perform DFT calculations using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with PAW pseudopotentials67. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is used to approximate the exchange-correlation energy between electrons68. The semicore d states for Ga and p states for K are treated as valence states. A energy cutoff for plane wave basis is set to 450 eV. We sample only the Γ point for Brillouin zone integration because the supercell size for generating the training data is sufficiently large. We account for Van der Waals interactions with the Grimme-D3 method69. During AIMD simulations, a timestep is set to 1 fs when hydrogen, the lightest element, is present in the supercell for ensuring the stability of the simulations. Otherwise, the timestep is set to 2 fs. Temperature control is implemented using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat for NVT simulations and the Langevin thermostat for NPT simulations. Our PBE+D3 approach is known to yield a stiffer hydrogen-bond network70. Nonetheless, it produces etching reaction energetics reasonably comparable to those obtained from more accurate methods, such as r2SCAN71 (Fig. S13), supporting its suitability for investigating wet-etching mechanisms.

MD simulation for wet etching in KOH solution

We perform molecular dynamics simulations of wet etching in KOH solution using the NNP within the LAMMPS package72. To efficiently explore the evolution of surface morphology within accessible MD time scales, we employ the TAD method, which accelerates chemical reactions by elevating the temperature. Specifically, we conduct NPT simulations at 2000 K, a temperature below the melting point of GaN. To prevent water vaporization, a pressure of 100 kbar is applied. A time step is set to 0.5 fs to ensure the stability of MD simulations. Due to the limited supercell size, the concentrations of dissolved species, such as gallium hydroxide ions ([Ga(OH)4]−) and ammonia (NH3), can instantly become unrealistically high, potentially altering solution properties and promoting undesirable reactions among byproducts (e.g., formation of a gallium hydroxide pillar, as shown in Fig. S14). To mitigate this, we regularly monitor the amount of dissolved species during etching simulations and remove them as necessary. At the same time, we replenish water and hydroxide molecules to maintain charge neutrality and to preserve the pH condition. For instance, when a [Ga(OH)4]− ion is removed, one OH− and two H2O molecules are added (Fig. S15). When a NH3 molecule is removed, one H2O molecule is added.

OPES (On-the-fly probability enhanced sampling)

To determine the free-energy profiles of key chemical reactions under experimental etching conditions, we conduct enhanced-sampling simulations based on collective variables (CVs). We define CVs as the coordination numbers of Ga-N, Ga-O, and N-H bonds. Herein, we adopt a continuous function to describe the coordination number (\({{\rm{CN}}}_{B}^{A}\)) which quantifies the number of neighboring atoms of type A around a central atom B within a cut-off radius r0:

where l and m are exponents controlling the sharpness of the function and di is the distance between atom i and the central atom B. The parameters l, m, and r0 are tuned for each bond type: Ga − N (14, 30, and 2.47 Å), Ga − O (12, 30, and 2.80 Å), and N − H (16, 30, and 1.58 Å). To enhance the likelihood of identifying transition states and the accuracy of free-energy estimation, we employ an adaptive reaction coordinate, σ(z), where z is a set of collective variables \({{\rm{CN}}}_{{\rm{Ga}}}^{{\rm{N}}},{{\rm{CN}}}_{{\rm{Ga}}}^{{\rm{O}}},{{\rm{CN}}}_{{\rm{N}}}^{{\rm{H}}}\). The coordinate σ(z) evolves along a parameterized curve, s(σ), which represents the average transition path connecting two local minima. An adaptive optimization for a given transition path is performed to identify the minimum free energy path, using the initial reference path. If a full reaction pathway involves σ(z) > 1, we performed OPES simulations sequentially for each reaction path, which facilitates better convergence of the free-energy profiles73,74,75. Each OPES simulation is run for at least five nanoseconds, and further extension of the simulation time do not change the overall conclusions, as demonstrated in Fig. S16. Detailed information on this approach and its implementation can be found in previous literature76,77.

To search for the lowest free-energy pathways, we employ the OPES method, which significantly improves the convergence of the calculations78. In OPES, the equilibrium probability distribution is estimated on the fly, followed by constructing a bias potential to guide the system toward a desired target distribution. A well-tempered target distribution, characterized by a bias factor γ > 1 and a temperature-dependent parameter β = 1/kBT, is considered in the present study. The bias potential Vn(σ), applied to the reaction path at each iteration, is given as:

with the probability distribution at n-th iteration Pn(σ), a normalization factor Zn, and a regularization parameter ϵ = e−βΔE/(1−1/γ). The maximum value of the bias potential is set to 3 eV to prevent the potential from overflowing into undesired high-energy molecular configurations. We employ the plumed2 package to conduct OPES simulations79.

Data availability

The primary training/validation dataset, trained NNP weights for each iteration, and LAMMPS/plumed2 scripts are available at Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16742609.

References

Wang, X., Zhao, X., Takahashi, T., Ohori, D. & Samukawa, S. 3.5 × 3.5 μm2 GaN blue micro-light-emitting diodes with negligible sidewall surface nonradiative recombination. Nat. Commun. 14, 7569 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Ultra-high brightness micro-leds with wafer-scale uniform gan-on-silicon epilayers. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 284 (2024).

Jeong, J. et al. Remote heteroepitaxy of gan microrod heterostructures for deformable light-emitting diodes and wafer recycle. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz5180 (2020).

Park, J. B. et al. Transfer printing of vertical-type microscale light-emitting diode array onto flexible substrate using biomimetic stamp. Opt. Express 27, 6832–6841 (2019).

Park, J. et al. Electrically driven mid-submicrometre pixelation of InGaN micro-light-emitting diode displays for augmented-reality glasses. Nat. Photonics 15, 449–455 (2021).

Huang, Y., Hsiang, E.-L., Deng, M.-Y. & Wu, S.-T. Mini-led, micro-led and oled displays: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 105 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. 31.1: invited paper: monochromatic active matrix micro-LED micro-displays with >5,000 dpi pixel density fabricated using monolithic hybrid integration process. Dig. Tech. Pap. 49, 333–336 (2018).

Gou, F. et al. High performance color-converted micro-LED displays. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 27, 199–206 (2019).

Min, J. et al. Bottom-up formation of iii-nitride nanowires: past, present, and future for photonic devices. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405558 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Self-array of one-dimensional gan nanorods using the electric field on dielectrophoresis for the photonic emitters of display pixel. Nanoscale Adv. 5, 1079–1085 (2023).

Ryu, H. et al. Wafer-scale vertical gan nanorod arrays with nonpolar facets using tmah wet etching. Appl. Surf. Sci. 661, 160040 (2024).

Johnson, J. C. et al. Single gallium nitride nanowire lasers. Nat. Mater. 1, 106–110 (2002).

Thaalbi, H. et al. Challenges in carrier gas-controlled growth of gan nanorods: Achieving uniformity and top-facet tunability in pulsed-mode mocvd. Cryst. Growth Des. 25, 191–202 (2025).

Yulianto, N. et al. Wafer-scale transfer route for top–down iii-nitride nanowire led arrays based on the femtosecond laser lift-off technique. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 32 (2021).

Oliva, M. et al. A route for the top-down fabrication of ordered ultrathin gan nanowires. Nanotechnology 34, 205301 (2023).

Jaloustre, L., Sales De Mello, S., Labau, S., Petit-Etienne, C. & Pargon, E. Faceting mechanisms of gan nanopillar under koh wet etching. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 173, 108095 (2024).

Aragon, A. et al. Defect suppression in wet-treated etched-and-regrown nonpolar m-plane gan vertical schottky diodes: a deep-level optical spectroscopy analysis. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 185703 (2020).

Liao, Y. et al. Improved device performance of vertical gan-on-gan nanorod schottky barrier diodes with wet-etching process. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 122109 (2022).

Olivier, F. et al. Influence of size-reduction on the performances of gan-based micro-leds for display application. J. Lumin. 191, 112–116 (2017).

Ley, R. T. et al. Revealing the importance of light extraction efficiency in InGaN/GaN microLEDs via chemical treatment and dielectric passivation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 251104 (2020).

Park, J. et al. Quantitative analysis and characterization of sidewall defects in ingan-based blue micro-leds. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 6, 8377–8383 (2024).

Guo, X., Gosalvez, M., Xing, Y. & Chen, Y. Etch and growth rates of gan for surface orientations in the <0001> crystallographic zone: Step flow and terrace erosion/filling via the continuous cellular automaton. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 153, 107173 (2023).

Zhuang, D. & Edgar, J. Wet etching of gan, aln, and sic: a review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 48, 1–46 (2005).

Li, D. et al. Selective etching of gan polar surface in potassium hydroxide solution studied by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 4219–4223 (2001).

Tautz, M. & Dıaz Dıaz, D. Wet-chemical etching of gan: Underlying mechanism of a key step in blue and white led production. ChemistrySelect 3, 1480–1494 (2018).

Tautz, M., Weimar, A., Graßl, C., Welzel, M. & Dıaz Dıaz, D. Anisotropy and mechanistic elucidation of wet-chemical gallium nitride etching at the atomic level. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 217, 2000221 (2020).

Weyher, J. L. et al. Chemical etching of gan in koh solution: Role of surface polarity and prior photoetching. J. Phys. Chem. C 126, 1115–1124 (2022).

Deringer, V. L., Caro, M. A. & Csányi, G. Machine learning interatomic potentials as emerging tools for materials science. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902765 (2019).

Fedik, N. et al. Extending machine learning beyond interatomic potentials for predicting molecular properties. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 653–672 (2022).

Wan, K., He, J. & Shi, X. Construction of high accuracy machine learning interatomic potential for surface/interface of nanomaterials-a review. Adv. Mater. 36, 2305758 (2024).

Yang, M., Raucci, U. & Parrinello, M. Reactant-induced dynamics of lithium imide surfaces during the ammonia decomposition process. Nat. Catal. 6, 829–836 (2023).

Xing, Z. & Jiang, X. Neural network potential-based molecular investigation of pollutant formation of ammonia and ammonia-hydrogen combustion. Chem. Eng. J. 489, 151492 (2024).

Kuryla, D., Csányi, G., van Duin, A. C. T. & Michaelides, A. Efficient exploration of reaction pathways using reaction databases and active learning. J. Chem. Phys. 162, 114122 (2025).

Benayad, Z., David, R. & Stirnemann, G. Prebiotic chemical reactivity in solution with quantum accuracy and microsecond sampling using neural network potentials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2322040121 (2024).

Jung, J., An, H., Lee, J. & Han, S. Modified activation-relaxation technique (artn) method tuned for efficient identification of transition states in surface reactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 8024–8034 (2024).

Zamora, R. J., Perez, D. & Voter, A. F. Speculation and replication in temperature accelerated dynamics. J. Mater. Res. 33, 823–834 (2018).

Chang, A. M., Meisner, J., Xu, R. & Martínez, T. J. Efficient acceleration of reaction discovery in the ab initio nanoreactor: Phenyl radical oxidation chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 9580–9589 (2023).

Takamoto, S. et al. Towards universal neural network potential for material discovery applicable to arbitrary combination of 45 elements. Nat. Commun. 13, 2991 (2022).

Kang, S. et al. Accelerated identification of equilibrium structures of multicomponent inorganic crystals using machine learning potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 108 (2022).

Feng, J., Aki, S. N. V. K., Chateauneuf, J. E. & Brennecke, J. F. Abstraction of hydrogen from methanol by hydroxyl radical in subcritical and supercritical water. J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 11043–11048 (2003).

Svishchev, I. M. & Plugatyr, A. Y. Hydroxyl radical in aqueous solution: computer simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 4123–4128 (2005).

Ertem, M. Z. et al. Photoinduced water oxidation at the aqueous gan (10\(\bar{1}\)0) interface: deprotonation kinetics of the first proton-coupled electron-transfer step. ACS Catal. 5, 2317–2323 (2015).

Chen, H.-A. & Pao, C.-W. Fast and accurate artificial neural network potential model for mapbi3 perovskite materials. ACS Omega 4, 10950–10959 (2019).

Hong, C. et al. Atomistic simulation of hf etching process of amorphous si3n4 using machine learning potential. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 48457–48469 (2024).

Schran, C. et al. Machine learning potentials for complex aqueous systems made simple. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2110077118 (2021).

Zhang, H., Juraskova, V. & Duarte, F. Modelling chemical processes in explicit solvents with machine learning potentials. Nat. Commun. 15, 6114 (2024).

Ju, S. et al. Application of pretrained universal machine-learning interatomic potential for physicochemical simulation of liquid electrolytes in li-ion batteries. Digital Discov. 4, 1544–1559 (2025).

Grisafi, A. & Ceriotti, M. Incorporating long-range physics in atomic-scale machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 204105 (2019).

Faller, C., Kaltak, M. & Kresse, G. Density-based long-range electrostatic descriptors for machine learning force fields. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 214701 (2024).

Kahle, L. & Zipoli, F. Quality of uncertainty estimates from neural network potential ensembles. Phys. Rev. E 105, 015311 (2022).

Bilbrey, J. A., Firoz, J. S., Lee, M.-S. & Choudhury, S. Uncertainty quantification for neural network potential foundation models. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 109 (2025).

Jeong, W., Yoo, D., Lee, K., Jung, J. & Han, S. Efficient atomic-resolution uncertainty estimation for neural network potentials using a replica ensemble. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 6090–6096 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Gan nanowire fabricated by selective wet-etching of gan micro truncated-pyramid. J. Cryst. Growth 426, 168–172 (2015).

Lai, Y.-Y. et al. The study of wet etching on gan surface by potassium hydroxide solution. Res Chem. Intermed. 43, 3563–3572 (2017).

Fujii, T. et al. Increase in the extraction efficiency of gan-based light-emitting diodes via surface roughening. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 855–857 (2004).

Dannecker, K. & Baringhaus, J. Fabrication of crystal plane oriented trenches in gallium nitride using \({{\rm{sf}}}_{6}^{+}\) ar dry etching and wet etching post-treatment. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 38, 043204 (2020).

Son, N. T. et al. Identification of the gallium vacancy–oxygen pair defect in gan. Phys. Rev. B 80, 153202 (2009).

Dreyer, C. E., Alkauskas, A., Lyons, J. L., Speck, J. S. & Van de Walle, C. G. Gallium vacancy complexes as a cause of shockley-read-hall recombination in iii-nitride light emitters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 141101 (2016).

Zhang, L. et al. A deep potential model with long-range electrostatic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 124107 (2022).

Barrett, R., Dietschreit, J. C. B. & Westermayr, J. Incorporating long-range interactions via the multipole expansion into ground and excited-state molecular simulations. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.21045 (2025).

Omranpour, A., Montero De Hijes, P., Behler, J. & Dellago, C. Perspective: Atomistic simulations of water and aqueous systems with machine learning potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 160, 170901 (2024).

Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G., Ortner, C. & Csanyi, G. Mace: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, (eds Koyejo, S. et al.) 35,11423–11436 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2022). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/file/4a36c3c51af11ed9f34615b81edb5bbc-Paper-Conference.pdf.

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Park, Y., Kim, J., Hwang, S. & Han, S. Scalable parallel algorithm for graph neural network interatomic potentials in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 4857–4868 (2024).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Lee, K., Yoo, D., Jeong, W. & Han, S. Simple-nn: An efficient package for training and executing neural-network interatomic potentials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 242, 95–103 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Bankura, A., Karmakar, A., Carnevale, V., Chandra, A. & Klein, M. L. Structure, dynamics, and spectral diffusion of water from first-principles molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 29401–29411 (2014).

Chen, M. et al. Ab initio theory and modeling of water. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 10846–10851 (2017).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comp. Phys. Comm. 271, 108171 (2022).

Májek, P. & Elber, R. Milestoning without a reaction coordinate. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6, 1805–1817 (2010).

Stack, A. G., Raiteri, P. & Gale, J. D. Accurate rates of the complex mechanisms for growth and dissolution of minerals using a combination of rare-event theories. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 11–14 (2012).

Conflitti, P., Raniolo, S. & Limongelli, V. Perspectives on ligand/protein binding kinetics simulations: Force fields, machine learning, sampling, and user-friendliness. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 6047–6061 (2023).

Díaz Leines, G. & Ensing, B. Path finding on high-dimensional free energy landscapes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 020601 (2012).

Hulm, A. & Ochsenfeld, C. Improved sampling of adaptive path collective variables by stabilized extended-system dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 9202–9210 (2023).

Invernizzi, M. & Parrinello, M. Rethinking metadynamics: From bias potentials to probability distributions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 2731–2736 (2020).

Tribello, G. A., Bonomi, M., Branduardi, D., Camilloni, C. & Bussi, G. Plumed 2: New feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604–613 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd (IO201214-08143-01) and the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00407995). We are grateful to Jisu Jung for the technical discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K. developed the neural network potential (NNP), conducted all major simulations and analyses, and wrote the paper. J.C. validated the potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution properties using the NNP. S.H. supervised the research. Y.K. wrote the paper and supervised the entire research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Ph., Choi, J.M., Han, S. et al. Neural network-driven molecular insights into alkaline wet etching of GaN: toward atomistic precision in nanostructure fabrication. npj Comput Mater 11, 311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01793-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01793-1