Abstract

Quantum transport simulations are essential for understanding and designing nanoelectronic devices, yet the long-standing trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency has limited their practical applications. We present DeePTB-NEGF, an integrated framework combining deep learning tight-binding Hamiltonian prediction with non-equilibrium Green’s function methodology to enable accurate quantum transport simulations in open boundary conditions with 2–3 orders of magnitude acceleration. We demonstrate DeePTB-NEGF through two challenging applications: comprehensive break junction simulations with over 104 snapshots, showing excellent agreement with experimental conductance histograms; and carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNT-FETs) at experimental dimensions, reproducing measured transfer characteristics for a 41 nm channel CNT-FET (~8000 atoms, 3 × 104 orbitals) and predicting zero-bias transmission spectra for a 180 nm CNT (~3 × 104 atoms, 105 orbitals), showcasing the framework’s capability for large-scale device simulations. Our systematic studies across varying geometries confirm the necessity of simulating realistic experimental structures for precise predictions. DeePTB-NEGF bridges the longstanding gap between first-principles accuracy and computational efficiency, providing a scalable tool for high-throughput and large-scale quantum transport simulations that enable previously inaccessible nanoscale device investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum transport simulation constitutes a cornerstone methodology for the investigation and engineering of nanoelectronic devices. The non-equilibrium Green’s function (NEGF) formalism1,2,3, when integrated with density functional theory (DFT)4,5, has emerged as the standard method for first-principles quantum transport investigations6,7,8. Nevertheless, the substantial computational overhead associated with DFT-NEGF self-consistent field (SCF) iterations imposes severe limitations on its practical applications, particularly in studying dynamic processes and large-scale systems.

This computational bottleneck is particularly acute in two critical scenarios: (i) break junction experiments9,10, the main platform for measuring the conductance of single molecules, requiring statistical analysis over thousands of configurations, and (ii) field-effect transistors at experimental nanoscale dimensions, where dominant quantum effects11,12 demand accurate first-principles modeling, but the large sizes lie beyond the reach of conventional first-principles methods. In both cases, the prohibitive computational cost restricts the studies to either selected static configurations or dramatically downsized systems, creating a disparity between computational tractability and experimental relevance. This compromise is widespread in nanoelectronics, highlighting the urgent need for more efficient methodologies to accelerate first-principles quantum transport simulations without sacrificing accuracy.

The key to addressing this challenge is to bypass the time-consuming DFT-NEGF SCF iterations while preserving first-principles fidelity. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising alternative to accelerate quantum transport calculations. Existing ML-based approaches include conductance prediction from atomic configurations13,14,15,16, and combining electronic and atomic features to infer transport properties17,18. While these methods demonstrate ML’s potential in transport simulations, they remain constrained to specific systems or selected transport characteristics, lacking the generalizability required for widespread adoption. A more fundamental and universal framework capable of accelerating first-principles quantum transport simulations while predicting diverse transport properties, ranging from transmission spectra to current-voltage characteristics, has yet to be established.

A more holistic solution would involve the direct prediction of the electronic Hamiltonians within the device geometries. By accurately modeling the fundamental electronic structures, this strategy could naturally yield all relevant transport characteristics rather than isolated properties. Recent advances, including our recently developed deep learning tight-binding (TB) Hamiltonian method DeePTB19,20, along with other electronic Hamiltonian prediction techniques21,22,23, have demonstrated impressive accuracy in predicting electronic structures. However, these approaches are limited to systems with periodic or isolated boundary conditions, leaving the unique challenges of open boundary conditions in device modeling unaddressed.

In this work, we introduce DeePTB-NEGF, a transformative framework extending the capabilities of electronic structure prediction to open boundary systems, a critical requirement for quantum transport in realistic devices with terminals. By achieving a 2 to 3 orders of magnitude acceleration compared to the conventional DFT-NEGF approach while maintaining first-principles accuracy, DeePTB-NEGF enables quantum transport simulations of complete experimental devices at previously inaccessible scales. The versatility and accuracy of DeePTB-NEGF are demonstrated in two challenging and representative applications.

First, we apply DeePTB-NEGF to break junction systems, demonstrating its capability for high-throughput simulations of dynamic processes. By modeling the complete elongation process (over 104 snapshots) of metallic contacts and molecule junctions, DeePTB-NEGF overcomes the immense computing cost of traditional DFT-NEGF while achieving excellent agreement with experimental data24. This application highlights DeePTB-NEGF’s ability to tackle statistical challenges requiring extensive simulations across numerous configurations.

Second, we demonstrate DeePTB-NEGF’s capacity to handle complex gate-controlled devices through simulations of carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNT-FETs) with a local bottom gate. Unlike two-terminal transport calculations, these simulations incorporate the bias among source, drain, and gate, necessitating self-consistent solutions of Poisson and quantum transport equations to properly capture gating effects. Our method accurately reproduces transfer characteristics for CNT-FETs with channel lengths up to 41 nm (~8000 atoms), showing excellent consistency with experimental measurements25. Furthermore, we successfully predict the transmission spectrum of a 180 nm CNT (~3 × 104 atoms and 105 orbitals), demonstrating DeePTB-NEGF’s potential for large-scale device simulations with first-principles accuracy.

These results establish DeePTB-NEGF as an important step toward bridging the long-standing divide between theoretical modeling and experimental reality in quantum transport. By enabling accurate, efficient modeling of device geometries at realistic scales, our method opens new horizons for the design and understanding of next-generation devices.

Results

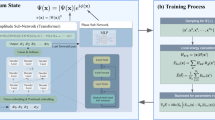

Efficient first-principles quantum transport simulations require an accurate electronic structure description while avoiding the computationally expensive DFT-NEGF SCF iterations. As illustrated in Fig. 1, our DeePTB-NEGF framework integrates deep learning-based Hamiltonian prediction and the NEGF formalism to enable high-throughput and large-scale quantum transport calculations. Below, we elaborate on each component of this integrated framework.

Atomic configurations X and \(X^{\prime}\) are structures for training and prediction, respectively. Reference Hamiltonians/overlap matrices \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{H}}}(X)\)/\(\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}(X)\) and reference eigenvalues \({\hat{\epsilon }}_{{\rm{nk}}}(X)\) are obtained from first-principles calculations, while \({\boldsymbol{H}}(X^{\prime} )\)/\({\boldsymbol{S}}(X^{\prime} )\) and \({{\boldsymbol{H}}}_{{\rm{TB}}}(X^{\prime} )\) represent predictions from the DeePTB model with the E3 method and SK method, respectively. T(E) denotes the transmission coefficient at energy E, and I is the current through the device.

Hamiltonian parameterization

DeePTB offers two complementary strategies for constructing electronic Hamiltonians: (1) the environment-dependent Slater-Koster (SK) TB Hamiltonians19 and (2) Kohn-Sham (KS) Hamiltonians in the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) basis with E(3) equivariant graph neural networks20. These strategies represent different trade-offs between computational efficiency and physical accuracy.

For the SK TB Hamiltonians19, DeePTB trains local environment-dependent SK integrals \({h}_{l{l}^{{\prime} }\zeta }^{\,\text{env}\,}\) as:

where \({h}_{l{l}^{{\prime} }\zeta }({r}_{ij})\) is the conventional SK integral, \({\Phi }_{l{l}^{{\prime} }\zeta }^{{o}_{i},{o}_{j}}\) introduces neural network-based environmental corrections through the descriptor \({{\mathcal{D}}}^{ij}\). This descriptor captures the chemical environment surrounding the atoms i and j. \(l,{l}^{{\prime} }\) denote atomic orbitals, ζ the bond types, and rij the interatomic distance. By training on the DFT eigenvalues \({\hat{\epsilon }}_{n{\boldsymbol{k}}}(X)\), the SK integrals as functions of the local environment can be predicted for unseen structures. This specific design transcends the intrinsic two-center approximation of the SK TB scheme while retaining the simplicity of the TB framework.

For the LCAO KS Hamiltonians20, DeePTB predicts multiple quantum operators (Hamiltonian, overlap, and density matrices) using E(3) equivariant neural networks with the localized equivariant message-passing (LEM) strategy. LEM provides a locality-based design for equivariant representations of quantum tensors, resulting in superior data efficiency and transferability20. The E(3) equivariant neural networks preserve rotational symmetry through angular momentum coupling:

where O represents the quantum operators, \({C}_{({l}_{1},{m}_{1})({l}_{2},{m}_{2})}^{({l}_{3},{m}_{3})}\) are the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients and \({o}_{{l}_{3},{m}_{3}}^{i,j}\) are the output node or edge features from the equivariant graph neural networks. After training on converged Hamiltonians and overlap matrices \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{H}}}(X)\) and \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{S}}}(X)\) obtained from DFT-NEGF, the features \({o}_{{l}_{3},{m}_{3}}^{i,j}\) would be determined.

Both strategies provide efficient access to electronic Hamiltonians while maintaining first-principles accuracy, though based on different theoretical frameworks. The SK-based approach prioritizes computational efficiency, making it particularly suitable for large-scale simulations. By contrast, the E(3)-equivariant approach yields a complete description of the DFT-level electronic structure, which is advantageous for applications that demand full electronic information. Together, the two complementary approaches provide a versatile toolkit for quantum transport calculations across different scenarios, balancing efficiency and electronic structure fidelity.

Open boundary condition treatment

Accurate quantum transport simulations require proper treatment of open boundary conditions to correctly model electron injection and extraction at the electrode-device interfaces. In the NEGF formalism, these open boundary conditions are incorporated through self-energies Σ that describe the coupling between the central scattering region and the semi-infinite electrodes with unit cells identical to the bulk structure3. Conventional DFT-NEGF approaches usually calculate electrode Hamiltonians from separate bulk simulations, then use these to construct self-energies with appropriate Fermi level alignment with the scattering region7,8,26.

For deep learning models to work effectively with open boundary conditions, they must accurately predict the electronic structure not only in the scattering region but also in the semi-infinite bulk electrodes, as depicted in the upper panel of Fig. 2. However, we discovered that simply training on primitive unit cells fails to produce correct Hamiltonians for electrode extensions, even with identical local environments. These Hamiltonians differ from true bulk by a constant energy shift due to long-range effects from the scattering region, creating a transferability problem.

Top panel: configuration for transport calculation consisting of a central scattering region connected to two semi-infinite electrodes. Bottom panel: configuration for DeePTB training with periodic boundary conditions. The local environment inside the cutoff radius rcut (marked by a bubble) for the atoms near the edge ofthe electrode extension is bulk-like.

We address this by introducing a constant shift freedom in the Hamiltonian representation:

where λ is determined during training by comparing DeePTB-predicted and DFT-calculated Hamiltonian blocks. This allows the training dataset to include both primitive unit cells and scattering regions simultaneously. To ensure a complete electrode extension description, we train on the entire scattering region with electrode extensions to create bulk-like environments within the cutoff radius rcut for atoms at the edge, as shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2. This leverages DeePTB’s locality features-either through the localized equivariant message-passing in DeePTB-E320 or the intrinsic locality of tight-binding in DeePTB-SK19. This locality captures relevant information nearly strictly within rcut, minimizing unnecessary long-range connections. Furthermore, using periodic boundary conditions in training (lower panel, Fig. 2) reduces the required electrode extension layers, improving the training efficiency.

NEGF formalism

With the Hamiltonians efficiently predicted by DeePTB, quantum transport properties are calculated using the NEGF formalism. The NEGF approach provides a rigorous framework for quantum transport by incorporating open boundary conditions through self-energies Σ that describe the coupling between the device and semi-infinite electrodes. For a two-terminal system, the transmission spectrum T(E), quantifying the energy-dependent electron transmission probability between electrodes, is given by:

where \({\Gamma }_{L/R}=i({{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}_{L/R}^{r}-{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}_{L/R}^{a})\) is the broadening function for the left (L) and right (R) electrodes and \({G}^{r/a}(E)={[(E\pm i\eta )S-H-{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}_{L}^{r/a}-{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}_{R}^{r/a}]}^{-1}\) is the retarded/advanced Green’s function with η being a positive infinitesimal and H/S being the Hamiltonian/overlap matrices.

The current (I) and zero-bias conductance (G) at the zero-temperature limit are then given by9:

where fL/R(E) are Fermi-Dirac distributions corresponding to the Fermi level of the left and right electrodes, Ef is the Fermi energy, G0 = 2e2/h is the quantum conductance, e is the elementary charge, and h is Planck’s constant.With Hamiltonians predicted by DeePTB, we further apply Bloch’s theorem to calculate the self-energy26and utilize the recursive Green’s function method27 with greedy algorithm28 to substantially enhance efficiency.

NEGF-Poisson self-consistency

To model realistic electronic devices operating under finite bias, it is essential to incorporate electrostatic effects through self-consistent coupling between quantum transport and electrostatics. In the DeePTB-NEGF framework, this is achieved through the NEGF-Poisson SCF procedure, which is particularly important for simulating field-effect transistors with gate control.

This self-consistency is achieved through the Gummel iteration scheme29, which begins with the equilibrium TB Hamiltonian H0 and iteratively solves for the non-equilibrium potential profile using the Poisson equation30,31

with the Newton-Raphson method on a discrete real-space grid. Here ϵ is the dielectric constant, ϕn+1 and ρn are the electrostatic potential and free charge number concentration in the n-th iteration. The term ρfix represents the average equivalent charge associated with ionized donors or acceptors at each atomic site within the doped region.In practical calculations, ρn is obtained as the Mulliken charge at all atomic sites based on the Hamiltonian Hn from the n-th iteration. The boundary conditions for the Poisson equation include constraints from gate voltage Vgs and drain-source bias Vds. Within the DeePTB-NEGF framework, the predicted TB Hamiltonian is updated according to the electrostatic potential as:

where \({H}_{n}^{i}\) and ϕn(ri) are the nth iteration Hamiltonian onsite block and electrostatic potential at site i, respectively. This NEGF-Poisson procedure enables the self-consistent treatment of quantum transport and electrostatics, essential for simulating realistic device behavior under biased conditions. This complete procedure is detailed in Supplementary materials (SM) Sec. S9, and our implementation has been validated against the established TB-NEGF code NanoTCAD ViDES30,32, as described in SM Sec. S10.

Having established the theoretical foundation and computational framework of DeePTB-NEGF, we now demonstrate its practical capabilities through two representative applications. These applications highlight the framework’s ability to address long-standing challenges in quantum transport simulation: statistical analysis of break junction experiments and realistic simulation of gate-controlled devices. The first application demonstrates how DeePTB-NEGF enables high-throughput calculations for statistical analysis, while the second showcases its capacity to handle large-scale systems with realistic dimensions.

Application 1: Break junction systems

Break junction experiments, primarily implemented through mechanically controllable break junctions or scanning tunneling microscopy break junctions9,10, provide a powerful platform for investigating quantum transport at the atomic and molecular scales. During a typical break junction elongation process, configurations evolve from metallic contacts with quantized conductance to the molecular junctions bridging nanoscale gaps33. Statistical nature of these experiments requires analyzing thousands of conductance measurements across multiple breaking events - a task prohibitively expensive for conventional first-principles calculations. The DeePTB-NEGF framework developed here enables efficient simulation of the break junction process while maintaining first-principles accuracy. Below, we demonstrate its capabilities in both metallic contacts and molecular junctions, providing direct comparison with experimental measurements and atomic-level insights into the quantum transport mechanisms. Here we employed the LCAO KS Hamiltonians predicted by DeePTB (Eq. (2)), which capture the full electronic structure and thereby enable the calculation of transmission spectra over the entire energy range.

Firstly, we investigate the gold metallic contact breaking process. Gold atomic contacts formed in break junction experiments (shown in Fig. 3a) exhibit distinct quantum transport features, including conductance quantization and ballistic transport34. As electrodes separate, the conductance evolves through characteristic plateaus, corresponding to specific atomic-scale contact configurations35. It requires thousands of breaking events to understand these quantum transport features through statistical analysis, making theoretical reproduction of conductance histograms at the first-principles level computationally challenging.

a Three representative snapshots in one breaking junction process. b Comparison for transmission at the Fermi level between the DeePTB-NEGF method (T) and DFT-NEGF calculations(\(\hat{T}\)) in structures obtained with different elongation speeds. c RMSE and MAE for zero-bias conductance between DeePTB-NEGF and DFT-NEGF results. Both RMSE and MAE are below 6 × 10−2 G0, ensuring sufficient accuracy for reliable conductance statistical analysis. d Conductance histograms from 10,119 configurations sampled from 85 elongation processes at three different speeds (v = 0.2, 1.0, and 5.0 m/s) compared with experimental measurements. Inset: experimental 1 G0 peak aligns with the v = 0.2 m/s case after shifting the experimental histogram by + 0.04 G0.

To simulate quantum transport through gold contacts, we construct a junction containing 304 gold atoms arranged along the [100] direction, with two bulk-like electrode extensions (100 atoms each in 5 × 5 × 4 supercells) shown as the scattering region in Fig. 2. Break junctions experiments were simulated through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations at 150K using the machine learning potential36 implemented in DeePMD37, with the simulation box being the scattering region under periodic boundary conditions. During elongation, the electrode sections are fixed as a bulk structure and move in opposite directions at speeds ranging from 0.2 to 5.0 m/s on each side. The resulting structures exhibit characteristic bipyramidal shapes consistent with experimental high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations38. Here, the choice of the [100] orientation and 150 K temperature serves primarily to define a benchmark setup for our study. A more detailed discussion of orientation and temperature choice is provided in SM. Sec. S1, demonstrating that DeePTB-NEGF is not limited to specific orientation and temperature.

To construct the DeePTB model for gold contacts, we randomly selected 122 configurations from 4 independent trajectories at v = ± 5.0 m/s labeled with Hamiltonians and overlaps using DFT-NEGF. Details of the dataset and training settings can be found in Methods. Building on the DeePTB-NEGF framework’s strategy in open-boundary systems, the model accurately predicts the electronic Hamiltonian for the complete atomic contact system, achieving root mean square error (RMSE) of 7.57 × 10−4 eV for Hamiltonians, and 4.73 × 10−5 for overlap matrices on the validation set. More importantly, despite being trained only on configurations from high-speed trajectories (v = 5.0 m/s), the model demonstrates outstanding transferability across different elongation speeds. For 55 randomly selected configurations spanning speeds from 0.2 m/s to 5.0 m/s, the predicted zero-bias conductance achieves exceptional agreement with DFT-NEGF results (R2 = 0.9985) as shown in Fig. 3b, with both RMSE and mean absolute error (MAE) below 60 × 10−3 G0 across all elongation speeds corresponding to a small relative error of only 1.55%, as illustrated in Fig. 3c. This error is nearly two orders of magnitude smaller than the characteristic conductance values (from several G0 to ~ 1 G0) and is also well below the separation between the main conductance peaks. This high precision ensures that all key features in the conductance histogram are clearly resolved, guaranteeing a reliable statistical analysis.

With the model validated, we then demonstrate its efficiency in high-throughput calculations by analyzing 10,119 configurations randomly sampled from 85 elongation processes at speeds of 0.2, 1.0, and 5.0 m/s - a scale previously inaccessible to first-principles methods. The calculations were accelerated using Bloch’s theorem for self-energy evaluation and exploiting the tridiagonal block structure of Hamiltonian matrices. Specifically, the electrode self-energies are computed only once and subsequently reused throughout the transport simulations, thereby significantly reducing the overall computational cost. To ensure statistical reliability, we verified that the conductance histogram is converged with respect to the sample size. As shown in the SM Sec. S2, the histogram constructed from 9049 snapshots is nearly identical to that from 10,119 snapshots, confirming the robustness of the results.

The predicted conductance histograms, normalized with respect to their respective 1 G0 peaks, are presented in Fig. 3d. The prominent peak at 1 G0 corresponds to monatomic chains, a well-established signature in gold metallic break junctions. Different elongation speeds lead to distinct variations in conductance peak shapes, particularly in the range from 1 G0 to 2 G0. This variation arises from the suppression of collective atomic relaxations at higher elongation speeds, which prolongs the stability of monatomic chains and therefore increases the height of 1 G0 peak before breaking13,39. Consequently, the relative intensity of conductance features beyond 1 G0 is systematically reduced in the normalized histograms. Note that the simulation speeds (0.2-5.0 m/s) are necessarily higher than experimental rates (10 pm/s to 100 nm/s)9, because the experimental breaking processes would require prohibitively large MD simulation times38. Nevertheless, even at these elevated speeds, our simulated conductance histogram at v = 0.2 m/s shows good agreement with experimental measurements, despite a minor shift (0.04 G0) in peak positions. This minor shift may result from structural perturbations or defects in the electrode, or from additional scattering processes in experiments, which are ignored in the simulations. By shifting the experimental histogram, we achieve excellent shape alignment of the 1 G0 peaks as shown in the inset of Fig. 3d. The aligned histograms reveal remarkable agreement between calculation and experiment38, particularly in reproducing two characteristic conductance peaks between 1 G0 and 2 G0.

These results demonstrate that our DeePTB-NEGF framework can efficiently and accurately predict the quantum transport properties of gold contacts, capturing the statistical features of the conductance histograms consistent with the experimentally observed characteristics.

Secondly, we focus on the single-molecule junctions. Unlike metallic contacts, single-molecule junctions present additional challenges for quantum transport calculations due to their complex chemical environments and dynamic metal-molecule interfaces. Their transmission spectra are particularly sensitive to molecular conformations and contact geometries, requiring extensive sampling to capture the dynamic features during junction formation and breaking that have been prohibitively expensive with traditional DFT-NEGF methods. Consequently, most previous DFT-NEGF studies focused on a few selected relaxed structures. While several works have combined MD (classical or first-principles) or Monte Carlo sampling with transport calculations to capture dynamical effects during junction evolution40,41,42,43, these approaches were typically limited to a relatively small number of snapshots or relied on approximate treatments due to the high computational cost of DFT-NEGF.

We investigated a classical π-conjugated system with a thiomethyl group as an anchoring group (top left inset of Fig. 4c), chosen for its rich chemical environments and flexible configurations due to three types of carbon bonds and the dihedral angle between the two benzene rings. The scattering region consists of a total of 478 atoms, with the molecule connected to gold [100]-oriented electrodes with a bi-pyramidal shape, where each electrode's principal layer contains 144 atoms (6 × 6 × 4 supercell). During stretching at 300 K as in experiment, the gold electrodes move in opposite directions at a speed of v = ± 2 m/s, with three representative snapshots at t1, t2 and t3 in equal time intervals shown in Fig. 4a. In these simulations, the gold atoms near the molecule were allowed to relax, while those far from the junction were fixed at their bulk lattice positions to mimic the extended electrodes, as illusrated in Fig. S5. To construct the DeePTB model for molecular junctions, we randomly sampled 268 configurations from 14 breaking junction trajectories as the training set, labeled with electronic Hamiltonians and overlaps using DFT-NEGF. More details of the dataset and training settings can be found in Methods.

a Three sequential snapshots of the molecular junction breaking process at equal time intervals (t1, t2 and t3). b Transmission spectra corresponding to the three snapshots in (a), and Fermi energy set to 0. c Spearman correlation coefficient between DeePTB-NEGF and DFT-NEGF transmission spectra within the energy range of -0.5 to 0.5 eV as a function of training dataset size. Blue dots show mean values with standard deviation error bars. Top left inset: Structure of the π-conjugated molecule with thiomethyl anchoring groups. Bottom right inset: Conductance histogram from 590 configurations across 11 stretching trajectories, showing a prominent peak at 10−3.3 G0.

To optimize model performance, we systematically studied the impact of training set size by training models using varying numbers of configurations (30, 60, 90, 123, 188, 208, 268) randomly sampled from the 14 breaking junction trajectories. In these calculations, the self-energy reuse strategy introduced above was employed as well to enhance the efficiency of the NEGF simulations. The prediction accuracy was evaluated using the Spearman coefficient44 between DeePTB-NEGF and DFT-NEGF transmission spectra in the energy range of -0.5 to 0.5 eV, which measures how well two variables can be described by a monotonic function. The coefficients are evaluated utilizing a validation set of 30 configurations from a different trajectory to test out-of-distribution generalization. As shown in Fig. 4c, both the mean and standard deviation of the correlation coefficient improve with increasing training set size, reaching a high value of 0.912 with 268 configurations. The diminishing rate of improvement suggests that the model performance is approaching convergence.

To further validate the statistical assessment of model accuracy indicated by the Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.912, we examine the performance of our model trained with 268 configurations by comparing transmission spectra for three representative configurations captured at times t1, t2 and t3 during the breaking junction process shown in Fig. 4a. As illustrated in Fig. 4b, the DeePTB-NEGF predicted transmission spectra closely match the DFT-NEGF results across different junction configurations, accurately reproducing both the positions and shapes of transmission peaks. Transmission comparisons in more snapshots are presented in SM Fig. S6. This consistency validates the accuracy of the predicted Hamiltonians as well as the robustness of the non-self-consistent NEGF calculation implemented in DeePTB-NEGF. Analysis of these transmission spectra further reveals distinct behavior of frontier molecular orbital contributions: the HOMO-dominated transmission peak maintains its energetic position relative to the Fermi level, while the LUMO-dominated peak shifts toward the Fermi level during junction elongation. This characteristic evolution of transmission peaks indicates that the conductance is LUMO-dominated, which is consistent with previous experimental and theoretical studies24. Furthermore, to enable statistical comparison with experimental measurements, we calculated the zero-bias conductance for 590 configurations sampled from 11 breaking junction trajectories. A convergence test (see SM Sec. S2) confirms that this number of samples is sufficient. The resulting conductance histogram (bottom right inset of Fig. 4c) shows a pronounced peak at 10−3.3 G0, in good agreement with the experimental value of 10−3.6 G024.

To quantify the computational advantage of our approach, we benchmarked DeePTB-NEGF against conventional DFT-NEGF using a molecular junction snapshot on moderate computing hardware (a 28-core CPU). By systematically scaling the system size up to 4798 atoms, we observed that DeePTB-NEGF achieves a remarkable 2–3 orders of magnitude speedup, as detailed in Fig. S7. The largest system’s transmission near the Fermi level was calculated in just 633 seconds, compared to projected 105 seconds (over 27 hours) for DFT-NEGF based on the linear extrapolation. More details can be found in the SM Sec. S5. This dramatic efficiency improvement transforms what were previously prohibitive calculations into routine tasks that can be performed on modest hardware. Furthermore, we also discuss the extrapolation capability of the DeePTB-NEGF framework, including its generality to different anchoring groups, as discussed in detail in the SM. Sec. S6.

From these investigations of break junction systems, we have demonstrated the applicability and accuracy of the DeePTB-NEGF approach in simulating quantum transport properties in the two cases of metallic atomic contacts and single-molecule junctions. Our method successfully captures the key features of the conductance evolution during the junction-breaking process and reproduces the main characteristics of the experimental conductance histograms. The excellent agreement between the DeePTB-NEGF and DFT-NEGF results further validates its accuracy in describing the electronic structure of the junctions, while our efficiency benchmarks reveal a remarkable 2−3 orders of magnitude speedup over conventional calculations. These results establish DeePTB-NEGF as a transformative method for studying quantum transport in break junction systems, finally enabling the statistical analysis necessary for meaningful comparison with experimental measurements while maintaining first-principles accuracy.

Applicaiton 2: Carbon nanotube field-effect transistor

Having demonstrated the capability of DeePTB-NEGF in break junction systems, we now turn to carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNT-FETs) that present substantial challenges in scale and complexity. CNTs with their quasi-one-dimensional structure and long mean free path enable ballistic transport at nanoscale dimensions, making them promising candidates for high-performance electronic devices25,45,46,47,48. Previous theoretical studies have typically relied on empirically parameterized Hamiltonians25,49,50,51 or employed tubes much smaller than experimental dimensions52. These compromises have created a persistent gap between theoretical simulations and experimental reality.

DeePTB-NEGF overcomes these limitations by enabling first-principles quantum transport simulations at experimental scales. To validate its computational capabilities, we first applied our method to predict transmission spectra for CNTs of increasing length. As shown in SM Sec.S8, with DeePTB-SK, our approach accurately reproduces DFT-NEGF results for a short tube (9 nm) while scaling efficiently to CNTs with length up to 180 nm containing approximately 30,000 atoms and 105 orbitals. This computational advantage demonstrates the potential of DeePTB-NEGF for large-scale device simulations.

Building on this foundation, we applied our framework to the more challenging and practically relevant case of CNT-FETs with gate control. The critical distinction in FETs is the presence of gate-modulated electrostatics, which necessitates a self-consistent solution of the Poisson equation coupled with the NEGF formalism53,54. As illustrated in Fig. 1, an integrated NEGF-Poisson SCF procedure is implemented in the DeePTB-NEGF formalism, enabling the quantum transport simulation under finite bias conditions. For these simulations, we employed the environment-dependent SK TB Hamiltonians predicted by DeePTB (Eq. (1)), which offer advantages over Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian models due to their smaller, sparser matrices and direct compatibility with the NEGF-Poisson framework.

We now apply the DeePTB-NEGF framework to study the transport properties of a local bottom gate (LBG) CNT-FET with experimental dimensions, demonstrating the capability of our method to simulate realistic nanoelectronic devices. The LBG CNT-FET geometry, shown in the inset of Fig. 5a, has been experimentally demonstrated to scale from 41 nm to 9 nm channel lengths without short-channel effects25,55. By simulating this specific device with different channel lengths, we aim to validate our method against experimental results and explore the scaling limits of CNT-FETs.

a Transfer characteristics at drain-source bias Vds = 0.4 V and dope concentrations as 8.89 × 108 m−1 for LBG CNT-FETs using different CNT diameters. The channel length Lch for all FETs is 9 nm. Inset: Schematic of the transistor geometry, where Lch denotes channel length. b, c Transfer characteristics at drain-source bias Vds = 0.4 V and dope concentrations as 8.89 × 108 m−1 for LBG CNT-FETs with channel length Lch as 18 nm and 41 nm. d–f Position-resolved local density of states for CNT(17, 0) along the transport direction (Z axis) with gate voltage Vgs = −0.8, −0.4 and 0. 0 V. The left and right electrodes are the drain and source, respectively. The red dashed lines indicate the Fermi level for source and drain. The orange dashed line in Vgs = 0.0 V case indicates the top of the valence band, inducing a barrier ΦB = 0.19 eV for holes.

Firstly we investigate the influence of CNT diameter on device performance. We simulated LBG CNT-FETs (channel length Lch = 9 nm) with various chirality indices (10, 0), (13, 0), (16, 0), and (17, 0), corresponding to diameters ranging from 0.79 nm to 1.35 nm. This range includes the 1.3 nm diameter CNTs used in the experiment reported in ref. 25, with CNT(16,0) and CNT(17,0) being the most comparable at diameters of 1.27 nm and 1.35 nm, respectively. We trained a sp-DeePTB model with environment-dependent SK parameter using the DFT eigenvalues of the CNT(7, 0), (10, 0), (13, 0) and (16, 0) structures as the training data set, allowing us to predict the TB Hamiltonian for CNT(17, 0). A comparison of band structures between DFT and DeePTB is illustrated in Fig. S9 in SM, validating the accuracy and generalizability of DeePTB SK TB Hamiltonian model across CNTs with different diameters. To model the metal contacts, we employed a doping contact approach by setting ρfix(r) in the Poisson equation (Eq. (7)). This method, previously employed in theoretical simulations25,52, induces a built-in electrostatic field between the doped regions and channel, mimicking the band bending at the Pd electrode-CNT interface in Ohmic contacted CNT-FET56,57. We tested doping concentrations ranging from 5.33 × 108 m−1 to 1.25 × 109 m−1, with little change in ON current and subthreshold swing (SS) (see SM Fig. S13a). Based on these tests, we chose a doping concentration of 8.89 × 108 m−1 for subsequent simulations. Additionally, since the bottom gate covers the channel as well as the source and drain contacts in the LBG device, we set the total gate length as Ltot = Lch + 2 × Lext, including the channel length Lch and source/drain extensions Lext25. Tests with different Lext values (Fig. S12b) indicated that Lext = 2.5 nm is sufficient to screen the impact from the channel.

Figure 5a shows the simulated transfer characteristics for 9-nm LBG CNT-FETs with varying diameters, demonstrating excellent agreement with experimental measurements. For clear comparison, the gate work functions of all devices were aligned to have the same ON current Ion ≈ 1 × 10−5 A, at Vgs = − 1.0 V. Notably, these CNTs with varying diameters (ranging from 1620 to 2,754 atoms) already exceed the computational limits of conventional DFT-NEGF-Poisson methods. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the transfer characteristics for the four tubes are similar in the ON state but differ dramatically in the subthreshold region. These differences arise from the distinct density of states (DOS) and band gaps of CNTs with varying diameters, resulting in different barrier heights Φb, between source and channel in CNT-FET at the OFF state. The intrinsic DOS of these CNTs, shown in Fig. S17, exhibits different distributions around the bias window, directly influencing the transport properties of the corresponding devices. In CNT-FETs, the barrier height Φb is illustrated by the local density of states (LDOS) as shown in Fig. 5d–f. For the same p-doped device, Φb increases as the gate voltage Vgs becomes more positive, hindering the injection of holes from the source and suppressing Ids. With diameter reduction, the OFF current Ioff decreases because larger band gaps in thinner CNTs would induce higher potential barriers Φb in the OFF state50,58, suppressing source-drain tunneling-the major contribution to Ioff. LDOS analysis reveals a significant decrease in Φb with increasing CNT diameter. As shown in Fig. S14, Φb in OFF states reduces from 0.48 eV for CNT(10,0) to 0.19 eV for CNT(17,0), consistent with the observed increases in Ioff. Despite these diameter-dependent differences in OFF current, Ion remains stable at approximately 1 × 10−5 A, attributed to similar transmission functions inside the drain-source bias window in the ON state across devices with different CNT diameters (see Fig. S13b). This comprehensive study of CNT diameter effects demonstrates the importance of accurately matching the simulated CNT size to experimental conditions for meaningful transfer characteristics and figures of merit such as Ion/Ioff.

To further validate our approach against experimental data, we extended our simulations to LBG CNT-FETs with longer channel lengths (18 nm and 41 nm) using CNT(16,0) and CNT(17,0), which closely match the experimental tube diameter. For these larger systems, the number of atoms ranges from 3904 (CNT(16,0) with Lch = 18 nm) to 7820 (CNT(17,0) with Lch = 41 nm), all exceeding the practical limits of conventional DFT-NEGF SCF calculations. The simulated results, shown in Fig. 5b and c, indicate that for both Lch = 18 and 41 nm, the SS agrees well with experimental data. In both cases, Ioff falls within the range predicted for CNT(16,0) and CNT(17,0), consistent with the experimental diameter lying between these two structures. The minor deviations between simulation and experiment, particularly in ON-state current and switching behavior at longer channel lengths, might be attributed to factors beyond ballistic transport, such as structural defects and scattering, which are not captured in our current model. Nevertheless, the overall agreement in key figures of merit demonstrates the validity of our approach for modeling realistic CNT-FETs.

To assess the scaling limit of LBG CNT-FETs, we further simulated devices with ultra-short channels as detailed in SM Sec. S18. As shown in Fig. S16, decreasing Lch from 9nm to 4nm leads to a sharp increase in SS from 98.88 mV/decade to 257.27 mV/decade, with Ion/Ioff dropping from 1 × 105 to 4 × 103. This rapid performance degradation signals the onset of severe short-channel effects due to reduced gate electrostatic efficiency48, indicating that the scaling potential of the LBG geometry is limited and further device geometry improvements are necessary for continued downscaling.

These results demonstrate the high fidelity of DeePTB-NEGF in quantum transport simulations with gate controlling, achieving DFT-level accuracy while maintaining the efficiency of TB method. By capturing essential physics across a wide range of nanotube diameters and channel lengths beyond the capability of conventional DFT-NEGF, this framework demonstrates excellent agreement with experimental data. This capability enables first-principles quantum transport analysis in realistic semiconductor devices, paving the way for more precise modeling and design of next-generation nanoelectronic technologies.

Discussion

In this work, we have developed DeePTB-NEGF, a deep learning-accelerated framework for first-principles quantum transport simulations in nanoelectronics. By integrating deep learning-based Hamiltonian prediction with the NEGF method, our approach enables efficient quantum transport calculations with or without self-consistent electrostatic effects. The framework demonstrates remarkable computational efficiency, handling break junction processes with over 104 snapshots, simulating the zero-bias transmission through a 180 nm CNT (~3 × 104 atoms), and modeling CNT-FETs with gate control and finite bias for channel lengths up to 41 nm (~8000 atoms)-scales previously inaccessible to first-principles methods.

For break junction systems, our framework accurately reproduced the statistical nature of experimental measurements by efficiently simulating thousands of configurations. The predicted conductance histograms captured key experimental features, including quantized conductance peaks in gold contacts and characteristic molecular junction signatures. This capability enables meaningful statistical analysis of break junction experiments with first-principles accuracy. For CNT-FETs, the DeePTB-NEGF-Poisson implementation successfully simulated devices with various diameters and channel lengths under finite bias conditions. The excellent agreement with experimental transfer characteristics validates our approach and demonstrates the importance of simulating devices at experimental dimensions. Our framework’s ability to predict the scaling behavior of CNT-FETs provides valuable guidance for future device designs.

With these achievements, the demonstrated performance of DeePTB-NEGF establishes a new paradigm for high-throughput and large-scale quantum transport simulations in nanoelectronics. Its dual capability in simulating break junction processes and transistors at experimental size opens new opportunities for advancing molecular electronics research and semiconductor device engineering. Future developments could incorporate electron-phonon scattering, defect-induced transport, and other quantum effects beyond ballistic transport. The framework could also be extended to more realistic and complex material interfaces and heterostructures relevant to next-generation devices. In particular, future work may incorporate effects such as multiple molecules and solvent environments in molecular junctions, as well as defects and contaminants in devices, to better capture experimental conditions. Furthermore, recent research indicates that massively parallel GPU-accelerated NEGF implementation can significantly reduce the computation time59, offering a promising path to further optimize our framework. By bridging the gap between fundamental physics and device-scale simulations, DeePTB-NEGF opens new possibilities for computational nanoelectronics in both research and industrial applications.

Methods

Datasets

The training dataset for metallic contacts consists of 122 configurations randomly sampled from 4 independent trajectories at elongation speed v = 5 m/s. The validation dataset includes 63 configurations from a single elongation process. Each configuration contains 304 atoms within the simulation box, with 100 atoms in both the left and right electrode regions. All configurations were generated via MD simulations at 150 K in the NVT ensemble, using the LAMMPS package60 based on a previously trained DeePMD model36. For DFT-NEGF calculations, we employed the TranSIESTA code7,26 with generalized gradient approximation (GGA) within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation as exchange-correlation functional and single-zeta plus polarization (SZP) basis. Only the Γ point was considered in reciprocal space, and norm-conserving pseudopotentials were applied. The iteration convergence threshold for the density matrix was set to 10−9.

The training dataset for single-molecule junctions consists of 30, 60, 90, 123, 188, 208, 268 configurations randomly sampled from 14 independent trajectories at elongation speed v = ±2 m/s. The validation dataset includes 30 configurations from one elongation process. Each configuration contains 478 atoms within the simulation box, with 144 atoms in both the left and right electrode regions. MD simulation was performed at 300 K using the ReaxFF reactive force field61, which can efficiently describe chemical bonding through its empirical bond-order formalism62. Other MD simulation and DFT-NEGF parameters are the same as those used for metallic contacts.

The training dataset for CNT comprises the band structure of zigzag CNT unit cell with different diameters (CNT(7,0), CNT(10,0), CNT(13,0), CNT(16,0)). The validation set is the band of CNT(17,0). The DFT-calculated and DeePTB-predicted bands are illustrated in SM Fig. S9. The DFT calculation is performed in SIESTA63 with SZP basis. The exchange-correlation functional is treated at GGA level within the PBE formulation.

Training settings

In the metallic contacts DeePTB-E3 model, to include the long-range interaction, the Localized Equivariant Message-passing (LEM) method is adopted in DeePTB-E320, using the irreducible representations (irreps for short) of the SO(3) group as the internal equivariant features. The model consists of 4 layers of message-passing neural networks with residual updates. To represent the interactions across (off-)diagonal blocks, we use the irreps setting 32 × 0e + 32 × 1o + 32 × 2e + 32 × 3o + 32 × 4e. The latent scalar channel dimension is fixed as 64. The cutoff radius of gold atoms is set to 7.4 Å, matching the maximum radius of gold atomic orbitals in DFT-NEGF. The loss function used is ‘hamil_abs’, which is composed of the first and second-order norms of the residuals between the target and predicted Hamiltonian/overlap matrices. The Adam optimizer is employed with an initial learning rate of 0.01. To accelerate convergence, the ReduceLROnPlateau learning rate scheduler is employed, which decays the learning rate once the averaged loss hasn’t decreased for the closest 60 epochs. We use the decay factor 0.8 in all training.

In the single-molecule junctions DeePTB-E3 model, the cutoff radius for the H, C, S, and Au are 3.8, 5.6, 7.1, and 6.9 Å. We used the loss function “hamil_blas". Unlike normal MAE or RMSE metrics that treat each matrix element equally, as in the loss function “hamil_abs", the “hamil_blas" uses a scattering mechanism to group the on (off) diagonal blocks by their atomic and bond species, computing the loss and average specifically. The resulting loss gives equal weights to every chemical element and bond species, helping to resolve the data scarcity when systems contain a type-unbalanced number of atoms and bonds. The Adam optimizer is employed with an initial learning rate of 0.001. The other training settings are the same as those in the metallic contacts DeePTB-E3 model.

In the CNT DeePTB-SK model, the fitting parameters for the empirical TB terms were represented by single neurons employing the “strain" onsite mode with the smooth cutoff rs = 2.5 and decay factor w = 0.3. The “ploy2exp" method is used for the hopping formula with the smooth cutoff rs = 4.0 and decay factor w = 0.2. For the environment descriptors in the embedding network, we utilized "se2" method37 with a ResNet neural network architecture of [10, 20, 60]. In embedding, the soft and hard cutoff radius rs and rc are 4.0 Å7D2and 6.1 Å, respectively. The fitting network for both hopping and onsite terms was implemented using a fully connected network with a size of [50, 50, 50]. Throughout all networks, the Tanh activation function was applied.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The DeePTB-NEGF framework combines two open-source packages: the quantum transport code dpnegf available at https://github.com/DeePTB-Lab/dpnegf and the deep learning tight-binding Hamiltonian prediction tool DeePTB accessible at https://github.com/deepmodeling/DeePTB.

Change history

28 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-026-01969-3

References

Kadanoff, L. P. & Baym, G. Quantum statistical mechanics: Green’s function methods in equilibrium and non-equilibrium problems. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429493218 (New York: W.A. Benjamin, 1962).

Keldysh, L. V. et al. Diagram technique for nonequilibrium processes. Sov. Phys. JETP 20, 1018 (1965).

Datta, S. Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805776 (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Taylor, J., Guo, H. & Wang, J. Ab initio modeling of quantum transport properties of molecular electronic devices. Phys. Rev. B 63, 245407 (2001).

Brandbyge, M., Mozos, J.-L., Ordejón, P., Taylor, J. & Stokbro, K. Density-functional method for nonequilibrium electron transport. Phys. Rev. B 65, 165401 (2002).

Rocha, A. R. et al. Spin and molecular electronics in atomically generated orbital landscapes. Phys. Rev. B 73, 085414 (2006).

Scheer, E. & Cuevas, J. C. Molecular electronics: an introduction to theory and experiment, Vol.15 (World Scientific, 2017)

Gehring, P., Thijssen, J. M. & van der Zant, H. S. Single-molecule quantum-transport phenomena in break junctions. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 381 (2019).

Deng, X. et al. Gate-controlled quantum interference effects in a clean single-wall carbon nanotube p-n junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 207002 (2023).

Iannaccone, G., Bonaccorso, F., Colombo, L. & Fiori, G. Quantum engineering of transistors based on 2D materials heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 183 (2018).

Bürkle, M. et al. Deep-learning approach to first-principles transport simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 177701 (2021).

Pan, J. Large-scale transport simulation by deep learning. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 306 (2021).

Deffner, M. et al. Learning conductance: Gaussian process regression for molecular electronics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 992 (2023).

Lin, D. et al. Transformer-based deep learning structure–conductance relationships in gold and silver nanowires. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 27, 7728–7739 (2025).

Topolnicki, R., Kucharczyk, R. & Kaminski, W. Combining multiscale MD simulations and machine learning methods to study electronic transport in molecular junctions at finite temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 19961 (2021).

Zhang, X., Xu, L., Lu, J., Zhang, Z. & Shen, L. Physics-knowledge-integrated neural network for quantum transport prediction of field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 034066 (2025).

Gu, Q. et al. Deep learning tight-binding approach for large-scale electronic simulations at finite temperatures with ab initio accuracy. Nat. Commun. 15, 6772, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51006-4 (2024).

Zhouyin, Z., Gan, Z., Pandey, S. K., Zhang, L. & Gu, Q. Learning local equivariant representations for quantum operators, in The 13th International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/forum?id=kpq3IIjUD3 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Deep-learning density functional theory Hamiltonian for efficient ab initio electronic-structure calculation. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 367 (2022).

Gong, X. et al. General framework for E(3)-equivariant neural network representation of density functional theory Hamiltonian. Nat. Commun. 14, 2848 (2023).

Zhong, Y., Yu, H., Su, M., Gong, X. & Xiang, H. Transferable equivariant graph neural networks for the Hamiltonians of molecules and solids. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 1 (2023).

Guo, M.-M. et al. Effectively enhancing the conductance of asymmetric molecular wires by aligning the energy level and symmetrizing the coupling. Langmuir 40, 3759 (2024).

Franklin, A. D. et al. Sub-10 nm carbon nanotube transistor. Nano Lett. 12, 758 (2012).

Papior, N., Lorente, N., Frederiksen, T., García, A. & Brandbyge, M. Improvements on non-equilibrium and transport Green function techniques: The next-generation TRANSIESTA. Comput. Phys. Commun. 212, 8 (2017).

Anantram, M., Lundstrom, M. S. & Nikonov, D. E. Modeling of nanoscale devices. Proc. IEEE 96, 1511 (2008).

Pecchia, A., Penazzi, G., Salvucci, L. & Carlo, A. D. Non-equilibrium Green’s functions in density functional tight binding: Method and applications. N. J. Phys. 10, 065022 (2008).

Gummel, H. K. A self-consistent iterative scheme for one-dimensional steady state transistor calculations. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 11, 455 (1964).

Fiori, G., Iannaccone, G. & Klimeck, G. A three-dimensional simulation study of the performance of carbon nanotube field-effect transistors with doped reservoirs and realistic geometry. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 53, 1782 (2006).

Ahn, P.-H. & Hong, S.-M. A fully coupled scheme for a self-consistent Poisson-NEGF solver. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 70, 239 (2022).

Marian, D., Marin, E. G., Perucchini, M., Iannaccone, G. & Fiori, G. Multi-scale simulations of two-dimensional material-based devices: the NanoTCAD ViDES suite. J. Comput. Electron. 22, 1327 (2023).

Xu, B. & Tao, N. J. Measurement of single-molecule resistance by repeated formation of molecular junctions. science 301, 1221 (2003).

Yu, Y., Cui, F., Sun, J. & Yang, P. Atomic structure of ultrathin gold nanowires. Nano Lett. 16, 3078 (2016).

Rego, L., Rocha, A., Rodrigues, V. & Ugarte, D. Role of structural evolution in the quantum conductance behavior of gold nanowires during stretching. Phys. Rev. B 67, 045412 (2003).

Andolina, C. M., Bon, M., Passerone, D. & Saidi, W. A. Robust, multi-length-scale, machine learning potential for Ag–Au bimetallic alloys from clusters to bulk materials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 17438 (2021).

Zhang, L., Han, J., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. Deep potential molecular dynamics: A scalable model with the accuracy of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 143001 (2018).

Lagos, M. J. et al. Temperature effects on the atomic arrangement and conductance of atomic-size gold nanowires generated by mechanical stretching. Nanotechnology 21, 485702 (2010).

Todorov, T. N. & Sutton, A. P. Force and conductance jumps in atomic-scale metallic contacts. Phys. Rev. B 54, R14234 (1996).

Paulsson, M., Krag, C., Frederiksen, T. & Brandbyge, M. Conductance of alkanedithiol single-molecule junctions: A molecular dynamics study. Nano Lett. 9, 117 (2009).

French, W. R. et al. Structural origins of conductance fluctuations in gold-thiolate molecular transport junctions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 887, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz4001104 (2013).

Nguyen, H. C., Szyja, B. M. & Doltsinis, N. L. Electric conductance of a mechanically strained molecular junction from first principles: Crucial role of structural relaxation and conformation sampling. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115440 (2014).

Ahart, C. S., Chulkov, S. K. & Cucinotta, C. S. Enabling ab initio molecular dynamics under bias: The CP2K+SMEAGOL interface for integrating density functional theory and non-equilibrium green functions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 6772 (2024).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 100, 441 (1987).

Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354, 56 (1991).

Peng, L.-M., Zhang, Z. & Wang, S. Carbon nanotube electronics: recent advances. Mater. today 17, 433 (2014).

Pitner, G. et al. Sub-0.5 nm interfacial dielectric enables superior electrostatics: 65 mV/dec top-gated carbon nanotube FETs at 15 nm gate length. in 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9371899 pp. 3–5 (IEEE, 2020).

Cao, W. et al. The future transistors. Nature 620, 501 (2023).

Alam, K. & Lake, R. Performance of 2 nm gate length carbon nanotube field-effect transistors with source/ drain underlaps, Appl. Phys. Lett. 87 https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-abstract/87/7/073104/117518/Performance-of-2-nm-gate-length-carbon-nanotube?redirectedFrom=fulltext (2005).

Guo, J., Datta, S. & Lundstrom, M. A numerical study of scaling issues for Schottky-barrier carbon nanotube transistors. IEEE Trans. electron devices 51, 172 (2004).

Leonard, F. & Stewart, D. A. Properties of short channel ballistic carbon nanotube transistors with ohmic contacts. Nanotechnology 17, 4699 (2006).

Xu, L. et al. Can carbon nanotube transistors be scaled down to the sub-5 nm gate length? ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 31957 (2021).

Sanchez-Soares, A., Kelly, T., Fagas, G., Greer, J. C. & Chen, E. Top-gated carbon nanotube FETs from quantum simulations: Comparison with experiments. in 2021 International Symposium on VLSI Technology, Systems and Applications (VLSI-TSA) https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9440104 pp.1–2 (IEEE, 2021).

Guo, J., Javey, A., Dai, H. & Lundstrom, M. Performance analysis and design optimization of near ballistic carbon nanotube field-effect transistors. in IEDM Technical Digest. IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting, 2004. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1419266 pp. 703–706 (IEEE, 2004).

Franklin, A. D. & Chen, Z. Length scaling of carbon nanotube transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 858 (2010).

Javey, A., Guo, J., Wang, Q., Lundstrom, M. & Dai, H. Ballistic carbon nanotube field-effect transistors. Nature 424, 654 (2003).

Léonard, F. & Tersoff, J. Multiple functionality in nanotube transistors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 258302 (2002).

Pal, A., Chavan, T., Jabbour, J., Cao, W. & Banerjee, K. Three-dimensional transistors with two-dimensional semiconductors for future CMOS scaling, Nat. Electron. 1 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41928-024-01289-8 (2024).

Sawant, S. S., Léonard, F., Yao, Z. & Nonaka, A. Eleqtronex: A GPU-accelerated exascale framework for non-equilibrium quantum transport in nanomaterials. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 110 (2025).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1 (1995).

Jarvi, T. T., Van Duin, A. C., Nordlund, K. & Goddard, W. A. III Development of interatomic ReaxFF potentials for Au-S-C-H systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 10315 (2011).

Senftle, T. P. et al. The ReaxFF reactive force-field: development, applications and future directions. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 1 (2016).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14, 2745 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the insightful discussions with Haoyang Pan, Daye Zheng, and Weiqing Zhou. This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20250472) and the Advanced Materials-National Science and Technology Major Project (2025ZD0618401) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (12504285), and National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFA1208203). Q. G. also acknowledges the funding support from the AI for Science Institute, Beijing (AISI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.G. conceived and led the project. S.H. co-supervised the research. J.Z., Z.Z., Y.H., and Q.G. developed the DeePTB-NEGF framework. J.Z. performed all the calculations and model training process, while D.L. provided the training data for break junction systems. J.Z. and Q.G. wrote the manuscript, and all authors commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, J., Zhouyin, Z., Lin, D. et al. Deep learning accelerated quantum transport simulations in nanoelectronics: from break junctions to field-effect transistors. npj Comput Mater 11, 375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01853-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01853-6

This article is cited by

-

Deep-learning electronic structure calculations

Nature Computational Science (2025)