Abstract

Low cycle fatigue often interacts with stress corrosion cracking behavior. In this work, the effect of low cycle fatigue on stress corrosion cracking susceptibility of a CrNiMoV steel was investigated by interrupted fatigue tests in air and slow strain rate tensile tests in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution at 180 °C. Microstructure evolution characterization verified cyclic softening and was found to improve stress corrosion cracking resistance with crack deflection along lath martensites due to a decrease of residual stress, phase transformation and increase of low-energy structures. As a semi-quantitative damage indicator, the microstructure evolution due to low cycle fatigue damage can be well described by the Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) from the Electron Backscatter Diffraction technique. The effect of fatigue damage on stress corrosion sensitivity was found predictable based on the linear relationship between KAM and stress corrosion sensitivity factor of reduction of area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fatigue failure is induced by a cumulative form of damage under cyclic loading associated with micro-crack initiation and propagation1. Low cycle fatigue (LCF) is a common loading mode for steam turbine rotors and blades during start-up and shut-down due to variations of centrifugal and thermal stress together with system resonance2. Several notched areas such as the heat-relieved grooves of the glands at the inlet end of the rotor, fillet radii at the base of disks, balance holes in the disks and blade grooving in reaction-type rotors3 will undergo severe LCF damage. Stress corrosion cracking (SCC) is another potential failure mode for nuclear steam turbine rotors operating in a wet steam environment4, and the SCC behavior of steam turbine rotors has been widely studied5,6. It appears that LCF and SCC may have interacted with each other, an issue that needs focusing and clarifying for underlying mechanisms, design, manufacturing and maintance techniques.

The steel used for steam turbine rotors (e.g., CrNiMoV steels) would soften during LCF process, especially at elevated temperatures, which was characterized by the decrease of dislocation density and the increase of subgrain size7,8. The process of cyclic softening contains two stages: the rapid softening in the early stage and stabilization in the following stage9,10,11. The different cyclic softening degree during LCF process was related to the formation of subgrain boundary12,13,14 and the interaction between dislocations and carbide precipitates15. The decrease of dislocation density was due to the formation and arrangement of dislocation cells in martensitic laths at the initial stage, and pinning of lath boundaries by carbide precipitates at the following stage16,17. The microstructure evolutions during LCF process led to the degradation of mechanical properties such as yield strength and hardness12,13,16,17. Furthermore, it was found that the change of microstructural strain localization can affect hydrogen embrittlement of the material18,19. It has been found the microstructure is one of the most important factors for the SCC sensitivity20, as a result, the SCC sensitivity of steam turbine rotor steel should be re-evaluated in the case of accumulation of in-service fatigue damage.

Several methods have been developed to quantify fatigue damage accumulation20, i.e., electric resistance method, hardness-based method, X-ray diffraction method, strain-based method, and nonlinear ultrasonic method21. The electric resistance method and strain-based method seem to be more prominent in later stages of fatigue, while the hardness-based method and X-ray diffraction are more or less sampling location dependent. Unfortunately, all these cannot characterize the microstructure changes during fatigue damage accumulation. It is reported that grain crystallographic structure strongly influences the mechanical and corrosion properties of materials13,22,23,24,25, and the intergranular corrosion resistance can be improved with higher proportion of low angle grain boundaries (LAGB)26. According to previous studies, the corrosion resistance of steam turbine rotor steel weldment was improved after the LCF test, while the galvanic corrosion of welded joint was promoted due to the difference of microstructural changes in the various regions of welded joints during cyclic plastic deformation27. Though SCC sensitivity of rotor steel welded joint has been impoved by fatigue damage28, the role of microstructure variation in mechanical properties and SCC sensitivity is not yet well understood. Therefore, damage parameter is highly needed to quantify the accumulation of fatigue damage for SCC sensitivity assessment of in-service component.

To this aim, the use of pure material other than welded joint has obvious advantage in avoiding galvanic corrosion effect. Therefore, in the present study, effect of cyclic softening caused by LCF on SCC sensitivity of a steam turbine rotor steel was investigated. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) techniques were used to elaborate the relationship between microscopic damage and macroscopic mechanical behavior. Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) based on EBSD examination was employed to represent fatigue damage evolution, and the relationship between KAM and SCC sensitivity was established.

Results and discussion

Microstructure characterization

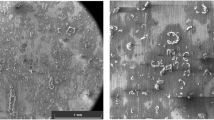

The microstructures of the as-received and fatigued specimens were observed by SEM and TEM. As shown in Fig. 1, the microstructures of 25Cr2Ni2MoV steel is mainly lath martensites. With the accumulation of LCF damage, retained austenites in the as-received specimen are transformed into martensites, the increasing number of sub-structures can be observed. Besides, the decreasing of maximum stress displays cyclic softening at the initial stage of fatigue process. Figure 2 shows the TEM micrographs of the as-received and fractured specimens. Plenty of dislocation tangles are observed in the as-received specimen (Fig. 2a), while dislocation density is decreased due to cyclic softening (Fig. 2b) which is in accoradance with those reported in open literatures7,8,27,29,30.

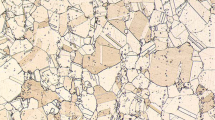

LAGB and KAM can be used to characterize the crystal orientations and evaluate residual strain distribution31,32,33. Fig. 3 shows the distribution of grain boundaries and their misorientation under different fatigue cycles. As shown in Fig. 3a–e, the angle of the yellow boundaries means low angle boundaries between 2° and 10°, while the angle of black and blue boundaries are between 15–45° and 45–60°. The black boundaries are mainly the prior austenite grain, and the grain orientation between boundaries is about 60°. During the cyclic softening in the LCF test, the retained austenite continues to transform34, and lattice distortion prefers to form low-energy grain boundaries33. The dislocations tend to accumulate at LAGBs which are then transformed into large angle grain boundaries. Compared with the regular and complete austenite grain boundaries (black grain boundaries) in Fig. 3a, it appears the rearrangement of austenite grain boundaries of fatigued specimens results in distortion of grain boundaries. With the accumulation of fatigue damage, the crushing of austenite grain boundaries due to the formation of sub-grain becomes more obvious, as observed in Fig. 3c–e. The recovered grain (or sub-grain) reduces the friction stress components as the dislocation density decreases. Furthermore, the back stress due to dislocation pile-ups at the grain boundaries, combined with the applied stress, promotes plasticity, which may cause a rearrangement of the austenite grain boundaries. The grain boundary (GB) distribution at different fatigue cycles is shown in Fig. 3f, where the grain tends to grow disorderly, leading to the misorientation between adjacent grain boundaries, and finally the decrease of dislocation density during fatigue test.

Panel (a) is the rearrangement of austenite grain boundaries of fatigued specimens results in distortion of grain boundaries under as-received condition. With the accumulation of fatigue damage from 5000 to 20,000 cycles, the crushing of austenite grain boundaries due to the formation of sub-grain becomes more obvious in (b)–(e). The grain tends to grow disorderly, leading to the misorientation between adjacent grain boundaries, and finally the decrease of dislocation density in (f).

KAM was used to characterize the local residual strain distribution, and was calculated by Eq. 132,35,36.

Where Δθ (P0, Pi) is the misorientation between the point P0 and neighboring points Pi in the same grain, N is the number of the neighboring points in the same grain.

Fig. 4 shows the KAM maps and local misorientation distribution at different fatigue cycles. It is observed in Fig. 4f that with the grain local misorientation at the peak becoming smaller (shift to left with loading cycles increasing), the frequency of the peak in the whole orientation increases, implying more severe small local misorientation among grains. It can be seen in Table 1 that the KAM average value is decreased with the increase of loading cycles, which is consistant with the evolution as observed in Fig. 4a–e. The evolution of grain boundaries and associated formation of sub-structures in the fatigue process mentioned above can explain the change in KAM value. During the cyclic softening in the LCF test, the lattice distortion prefers to form low-energy grain boundaries. The change of grain boundaries absorbs the accumulated energy and residual strain in the materials, resulting in a decrease in dislocation density and a corresponding decrease in KAM value. Additionally, stress concentration occurs at the edge of the grain boundary. Fatigue damage causes grain refinement and an increase in dislocation density, which in turn leads to changes in grain boundaries. Similar results have been reported in ref. 37,38. Comparing Fig. 3 with Fig. 4, it is observed that large residual strain is mainly concentrated upon austenite GBs in the as-received condition, and the transformation of residual austenite absorbs parts of strain energy at the grain boundaries. As a result, the residual strain of fatigued specimens is mostly localized at lath martensite boundaries.

Stress corrosion cracking sensitivities

The stress-strain curves obtained from SSRT in air and 3.5% NaCl solution at 180 °C are shown in Fig. 5. It can be found the ductilities of fatigue damaged specimen significantly increased by cyclic softening both in air and corrosion environment. Table 2 shows the mechanical properties under different fatigue damage. The yield strength (σs) is the stress when the strain value is 0.2% of the total strain, and the tensile strength (σb) is the maximum stress during the test. There is no significant trend for yield strength and tensile strength, which may be caused by the local damage during the LCF test and redistribution of grain boundaries after LCF test. The stress corrosion sensitivity factors calculated by different mechanical parameters are listed in Table 3. Since there are no significant differences of tensile strength and yield strength in air and corrosion environment, the stress corrosion cracking sensitivity factors calculated by tensile strength and yield strength are small which cannot well reflect the effect of fatigue damage on stress corrosion cracking properties. The stress corrosion cracking sensitivity factors calculated by fracture time are not suitable either because the values are very close to each other. However, as a performance parameter of plastic deformation capacity, the reduction of area (\(\varphi\)) has a tendency to increase with the increasing of LCF cycles in both air and corrosive environment, and stress corrosion cracking sensitivity factors are decreased with the increasing of fatigue damage. Furthermore, the performance parameter of toughness, the area included in the stress-strain curve (A) shows the same tendency with the reduction of area which is probably related to cyclic softening during LCF tests. Therefore, the effect of fatigue damage on the stress corrosion cracking sensitivity can be well expressed by the reduction of area (\(\varphi\)) and the area included in the stress-strain curve (A).

The fracture mechanism under different environments was studied using SEM. The typical fractography in air conditions is shown in Fig. 6, which shows an apparent ductile failure accompanying the cup-shaped necking phenomenon. As shown in Fig. 6a, the dimples in the middle area are much larger than that in the edge area. Fig. 6b shows the fractography of the as-received specimen in 3.5% NaCl solution. The fractured edge of the specimen is relatively flat, showing a river-like streak pattern, which is a typical brittle fracture feature. It can be also observed from Fig. 6b that corrosion products are densely distributed on the fracture surface. SCC is related to anodic dissolution during the tensile process39, and is performed as stepped stripes in the middle area, which may be caused by continuously broken and newly formed oxide film of the specimen during crack propagation. Besides, the cleavage morphology indicates a brittle fracture, which means when SCC propagates, the crack tends to propagate along the direction which is easy to slip at grain boundaries. Fig. 6c shows the fractography of fatigued specimen of 20,000 cycles. Comparing the specimen under the LCF test and the as-received condition, the surrounding oxidation products of fatigued specimen are denser, and there are larger dimples in the middle area, which indicates the ductility of the specimen is better. When the test enters the strengthening stage, the stress is dominant, and the specimen appears with plastic characteristics such as dimples. The increases of dimple size and plastic area also indicate the decrease of SCC sensitivity after fatigue test.

In (a), the dimples in the middle area are much larger than that in the edge area for loading of 5000 cycles in air. In (b), stepped stripes in the middle area and the cleavage morphology close to surface for as-received condition in NaCl solution. In (c), the increases of dimple size and plastic area can be observed for 20,000 cycles in NaCl solution.

Contribution of LCF to SCC

After SSRT tests, the specimens were cut along the axial direction to study the crack propagation mechanism. As the inverse pole figure (IPF) map shows in Fig. 7d, the main crack propagation mode of SCC is transgranular, while as the crack grows, the crack will deflect along the grain boundary, especially near the crack tip where the crack will extends along the direction of lath martensites, as shown in Fig. 7b, c.

A typical crack of as-received specimen can be seen in (a), the main crack propagation mode of SCC is transgranular in (b) and (c), while as the crack grows, the crack will deflect along the grain boundary, especially near the crack tip where the crack will extends along the direction of lath martensites, the crack crossed the direction of lath martensite in (d).

It has been reported that the increase of LAGB disrupted the grain boundary network, which leaded to higher resistance to SCC40,41,42. As for crack deflection phenomenon in SCC43,44,45, the fatigued specimen is more likely to propagate along the grain and lath martensite boundaries, due to decrease of dislocation accumulation, residual stress and increase of low-energy structures. Figure 8 shows that the crack propagates along the lath martensite boundaries (white arrow) for fatigued specimens with loading of 10,000 cycles and 20,000 cycles, and in some cases the main crack can propagate along the grain boundaries.

The comparison of two complete cracks sampled from the as-received specimen and 20,000 cycles specimen are shown in Fig. 9. It has been reported that the multiplication and motion of dislocations were active in the grain with high Schmid factor46,47,48. It is observed in Fig. 9 that the Taylor factor and Schmid factor of fatigued specimen are reduced, indicating the lower degree of plastic deformation, and an increased cracking resistance, as compared with the as-received condition. Besides, from the strain contouring, it is confirmed that the growing crack can bypass the position with large residual strain. Therefore, it can be concluded that during the cyclic softening process, with the dislocation density of the specimen decreased, phase transformation and increase of the internal low-energy structures lead to a higher energy threshold for crack propagation. As a result, cracks tend to grow along the direction of lath martensites.

Correlation LCF damage with stress corrosion cracking sensitivity

It is observed in Fig. 1 that the property change of materials is mainly occurred in the initial stage of the LCF test, which may be related to the cyclic softening behavior mainly appearing in nearly 15% of total fatigue life33,49. KAM value is usually used for estimation of dislocation density within the grains. The local variation of misorientation is a good indicator of strain localization in crystalline material where the stored energy is consumed by accumulated fatigue damage. The feasibility of KAM representing fatigue damage is that its calculation excludes misorientations greater than 15° to avoid the contribution of grain boundaries. Although cyclic softening can explain the effect of fatigue damage on stress corrosion property of material, it is not sufficient to reveal the multi-scale relationship between macroscopic assessment and microscopic damage characterization which are strongly related with corrosion or stress corrosion property. In 3.5% aqueous NaCl solution at 180 °C, the oxide films ruptured due to slip bands intersecting the crack tip, fresh metal exposed to the local environment, and then oxide formed along the crack tip, SCC is mainly controlled by slip dissolution mechanism with a cyclic process of “slip-film rupture-oxidation” for steam turbine rotor steels. The formation rate of oxide film at the crack tip presented by anodic current density of the metal is changed by microstructure, furthermore, the oxidation rupture rate is also strongly related to the microstructure due to the slip of local plastic zone at the crack tip.

Figure 10 shows the KAM value, Iφ and IA under different levels of fatigue damage. It is indicated that the SCC sensitivity of the specimen will decrease with the reduction of dislocation density and residual stress as a result of cyclic softening in LCF test. It is thus inferred that the cyclic softening, accompanied by dislocation density decrease, and the associated optimization of internal grain boundary, leads to the decrease of KAM value. The decreased tendency of KAM value agrees well with the stress corrosion cracking sensitivity factor Iφ and IA, especially at early stage of fatigue damage. Therefore, the effect of fatigue damage on stress corrosion cracking sensitivity of materials can be evaluated semi-quantitatively by KAM.

In the present work, KAM value was used to characterize the dislocation density and the residual strain of materials. In order to quickly define the effect of microstructure changes caused by fatigue damage on stress corrosion sensitivity, it is reasonable to characterize the relationship between dislocation density and SCC sensitivity by KAM value and SCC sensitivity factor I. The variation of KAM and SCC sensitivity factors can be defined as:

Where Ki, \({I}_{\varphi i}\) and \({I}_{{Ai}}\) are the KAM value, Iφ and IA of fatigued specimen with different number of cycles, while K0, \({I}_{\varphi 0}\) and \({I}_{A0}\) are the KAM value, Iφ and IA of the as-received specimen, respectively.

It can be observed from Fig. 11 that \({D}_{I\varphi }\) and DK are linearly correlated well compared with the relationship between \({D}_{{IA}}\) and DK. As a parameter representing the loss of plastic deformation in corrosion environment, SCC sensitivity factor Iφ is thus regarded as an indicator for SCC sensitivity. Therefore, the effect of LCF damage on SCC sensitivity can be linearly predicted based on the quantitative relationship between KAM value and SCC sensitivity factor Iφ.

Based on the above analysis, it is concluded that: (1) Pre-fatigue of the CrNiMoV steel induced cyclic softening behavior with grain misorientation increased and dislocation density decreased, and was consistant with the decreasing of KAM values. (2) LCF damage increased plastic property of the CrNiMoV steel and improved the SCC resistance with crack deflection along lath martensites due to decrease of residual stress, phase transformation and increase of low-energy structures. (3) The KAM value was a reasonable LCF damage indicator, and the effect of LCF damage on SCC sensitivity could be predicted by establishing the linear relationship between KAM value and SCC sensitivity factor Iφ for the CrNiMoV steel in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution at 180 °C.

Methods

Test materials

The material used in the present research is a type of CrNiMoV steel, and the chemical compositions are listed in Table 4.

Pre-fatigue tests

The specimens were pre-fatigued with interrupted strain-controlled LCF tests, and the geometry of the specimens is shown in Fig. 12a. The LCF tests were performed with a triangular waveform at 25 °C, a strain ratio of −1, a strain amplitude of ±0.3%, and a strain rate of 0.008 s−1. The fatigue life is estimated at about 24000 cycles, and thus specimens with cyclic loading of 5000 cycles, 10,000 cycles, 15,000 cycles and 20,000 cycles were selected for fatigue damage characterization. Three parallel specimens were used to ensure the repeatability and accuracy of the experiments.

Microstructure observation

The specimens for microstructure observation (Fig. 12b, Φ10 mm × 2 mm) were sampled from LCF test specimens. The specimens were grounded by 220, 400, 800, 1200, and 2000 grit silicon carbide emery papers, and polished for an hour using oxide polishing suspension (OP-U NonDry). Microstructures of specimens under different fatigue loading cycles were observed by EBSD with a scanning step of 0.1 μm.

SSRT test and SCC sensitivity assessment

In order to assess SCC sensitivity of pre-fatigued specimens, slow strain rate tensile (SSRT) specimens were machined from the LCF specimen, and the geometry of specimens is shown in Fig. 1c. The SSRT tests were conducted in 3.5% aqueous NaCl solution and air at 180 °C. The specimen was mounted onto the Cortest SCC machine, and loaded with a strain rate of 10–6 s−1. Prior to experiments, the specimens were cleaned ultrasonically with deionized water, alcohol and acetone. The stress-strain curves were measured through displacement and load extensometers. The fractured specimens were ultrasonically cleaned again, and the fracture morphology was observed by SEM. Three parallel specimens were adopted for each pre-fatigue condition.

The SCC sensitivity of the specimen was evaluated by Eq. 5.

Where \({{SSRT}}_{s}\) is the result obtained at 180 °C, 3.5% NaCl solution, and \({{SSRT}}_{a}\) is the result obtained at 180 °C air condition. I is the SCC sensitivity factor. In order to well understand the relationship between fatigue damage and SCC sensitivity, the stress corrosion cracking sensitivity results can be expressed by (1) \({I}_{b}\), stress corrosion sensitivity factor expressed in tensile strength, (2) \({I}_{s}\), stress corrosion sensitivity coefficient expressed in yield strength, (3) \({I}_{\varphi }\), stress corrosion sensitivity coefficient expressed in the percentage of reduction area, (4) \({I}_{t}\), stress corrosion sensitivity coefficient expressed in fracture time, (5) \({I}_{A}\), stress corrosion sensitivity coefficient expressed in the area included in the stress-strain curve. In addition, the larger the factor is, the higher stress corrosion sensitivity will be.

Data availability

Data will be available on request.

References

Fatemi, A. & Yang, L. Cumulative fatigue damage and life prediction theories: a survey of the state of the art for homogeneous materials. Int. J. Fatigue 20, 9–34 (1998).

Cano, S. et al. Detection of damage in steam turbine blades caused by low cycle and strain cycling fatigue. Eng. Fail. Anal. 97, 579–588 (2019).

Barella, S., Bellogini, M., Boniardi, M. & Cincera, S. Failure analysis of a steam turbine rotor. Eng. Fail. Anal. 18, 1511–1519 (2011).

Banaszkiewicz, M. & Rehmus-Forc, A. Stress corrosion cracking of a 60MW steam turbine rotor. Eng. Fail. Anal. 51, 55–68 (2015).

Lin, S., Huang, Y., Xuan, F. & Tu, S. Study on stress corrosion cracking sensitivity of CrNiMoV steam turbine rotor steels. Key Eng. Mater. 795, 102–108 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Comparison of oxide layers formed on the low-cycle fatigue crack surfaces of Alloy 690 and 316 SS tested in a simulated PWR environment. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 51, 479–489 (2019).

Mayer, T., Balogh, L., Solenthaler, C., Müller Gubler, E. & Holdsworth, S. R. Dislocation density and sub-grain size evolution of 2CrMoNiWV during low cycle fatigue at elevated temperatures. Acta Mater. 60, 2485–2496 (2012).

Zhang, Q. et al. Low-cycle fatigue behaviors of a new type of 10% Cr martensitic steel and welded joint with Ni-based weld metal. Int. J. Fatigue 88, 78–87 (2016).

Wang, C., Xuan, F.-Z. & Zhao, P. A dislocation-based constitutive model for the cyclic response of nanolath strengthened steels. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 155, 475–487 (2019).

Zhao, P., Xuan, F.-Z. & Wu, D.-L. Cyclic softening behaviors of modified 9–12%Cr steel under different loading modes: role of loading levels. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 131–132, 278–285 (2017).

Shankar, V. et al. Low cycle fatigue behavior and microstructural evolution of modified 9Cr–1Mo ferritic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 437, 413–422 (2006).

Hu, X. et al. Low cycle fatigue properties of CLAM steel at room temperature. Fusion Eng. Des. 88, 3050–3059 (2013).

Barrett, R. A., O’Donoghue, P. E. & Leen, S. B. A physically-based constitutive model for high temperature microstructural degradation under cyclic deformation. Int. J. Fatigue 100, 388–406 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Hu, Z., Schmauder, S., Zhang, B. & Wang, Z. Low cycle fatigue properties and microstructure of P92 ferritic-martensitic steel at room temperature and 873 K. Mater. Charact. 157, 109923 (2019).

Wu, D.-L., Xuan, F.-Z., Guo, S.-J. & Zhao, P. Uniaxial mean stress relaxation of 9–12% Cr steel at high temperature: Experiments and viscoplastic constitutive modeling. Int. J. Plast. 77, 156–173 (2016).

Kim, D. W. & Kim, S. S. Contribution of microstructure and slip system to cyclic softening of 9 wt%Cr steel. Int. J. Fatigue 36, 24–29 (2012).

Mishnev, R., Dudova, N. & Kaibyshev, R. Effect of microstructural evolution on the cyclic softening of a 10% Cr martensitic steel under low cycle fatigue at 600 °C. Int. J. Fatigue 134, 105522 (2020).

Fan, Y. H., Zhang, B., Wang, J. Q., Han, E. H. & Ke, W. Effect of grain refinement on the hydrogen embrittlement of 304 austenitic stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35, 2213–2219 (2019).

Weng, S., Huang, Y. H., Xuan, F. Z. & Luo, L. H. Correlation between microstructure, hardness and corrosion of welded joints of disc rotors. Procedia Eng. 130, 1761–1769 (2015).

Link, R. E., Yang, L. & Fatemi, A. Cumulative fatigue damage mechanisms and quantifying parameters: a literature review. J. Test. Eval. 26, (1998).

Bjørheim, F., Siriwardane, S. C. & Pavlou, D. A review of fatigue damage detection and measurement techniques. Int. J. Fatigue 154, 106556 (2022).

Shimada, M., Kokawa, H., Wang, Z. J., Sato, Y. S. & Karibe, I. Optimization of grain boundary character distribution for intergranular corrosion resistant 304 stainless steel by twin-induced grain boundary engineering. Acta Mater. 50, 2331–2341 (2002).

Bennett, B. W. & Pickering, H. W. Effect of grain boundary structure on sensitization and corrosion of stainless steel. Metall. Trans. A 18, 1117–1124 (1991).

Hu, H., Zhao, M. & Rong, L. Formation and evolution of low ∑CSL grain boundaries in J75 hydrogen-resistant alloy. Rare. Metal. Mat. Eng. 49, 131–137 (2020).

Wang, W., Zhou, B., Feng, L., Zhang, X. & Xia, S. Grain boundary character distributions (GBCD) of cold-rolled Pb–Ca–Sn–Al alloy during recovery and recrystallization. Acta Metall. Sin. 715–721 (2006).

Xia, S., Zhou, B. & Chen, W. Effect of single-step strain and annealing on grain boundary character distribution and intergranular corrosion in Alloy 690. J Mater. Sci. 43, 2990–3000 (2008).

Weng, S., Huang, Y., Xuan, F.-Z. & Zheng, S. Enhanced Galvanic corrosion phenomenon in the welded joint of NiCrMoV steel by low-cycle fatigue behavior. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, C270–C283 (2019).

Huang, Y., Si, X., weng, S. & Xuan, F.-Z. Effect of fatigue damage on stress corrosion cracking sensitivity of nuclear steam turbine welded joint. Trans. China Welding Institution 41, 12–19 (2020).

Guguloth, K., Sivaprasad, S., Chakrabarti, D. & Tarafder, S. Low-cyclic fatigue behavior of modified 9Cr–1Mo steel at elevated temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 604, 196–206 (2014).

Giordana, M. F., Alvarez-Armas, I. & Armas, A. Microstructural characterization of EUROFER 97 during low-cycle fatigue. J. Nucl. Mater. 424, 247–251 (2012).

Vogt, J. B., Argillier, S., Massoud, J. P. & Prunier, V. Fatigue damage evaluation of a power plant component from analysis of the dislocation structures. Eng. Fail. Anal. 7, 301–310 (2000).

Vogt, J. B., Bouquerel, J., Léaux, F. & Palleschi, F. Fatigue damage assessment of alternator fans by EBSD. Procedia Eng 66, 608–614 (2013).

Oh, Y.-J. et al. Crystallographic evolution and cyclic softening behavior of reduced activation ferritic-martensitic steel under different fatigue modes. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 802, 140454 (2021).

Gates, J. D., Atrens, A. & Smith, I. O. Microstructure of as-quenched 3.5NiCrMoV rotor steel. Part I. General structure and retained austenite. Materialwiss. Werksttech. 18, 165–170 (1987).

Kamaya, M. Assessment of local deformation using EBSD: quantification of local damage at grain boundaries. Mater. Charact. 66, 56–67 (2012).

Allain-Bonasso, N., Wagner, F., Berbenni, S. & Field, D. P. A study of the heterogeneity of plastic deformation in IF steel by EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 548, 56–63 (2012).

Garbacz, H., Pakiela, Z. & Kurzydlowski, K. J. Fatigue properties of nanocrystalline titanium. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 25, 256–260 (2010).

Zhu, D. P., Zhang, W. & Ding, Z. X. Dislocation density evolution in low-cycle fatigue of steels using dislocation-based crystal plasticity. J. Eng. Mech. 148, 13 (2022).

Ma, H., Liu, Z., Du, C., Li, X. & Cui, Z. Comparative study of the SCC behavior of E690 steel and simulated HAZ microstructures in a SO2-polluted marine atmosphere. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 650, 93–101 (2016).

Telang, A. et al. Iterative thermomechanical processing of alloy 600 for improved resistance to corrosion and stress corrosion cracking. Acta Mater. 113, 180–193 (2016).

Randle, V. & Jones, R. Grain boundary plane distributions and single-step versus multiple-step grain boundary engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 524, 134–142 (2009).

Telang, A. et al. Surface grain boundary engineering of Alloy 600 for improved resistance to stress corrosion cracking. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 648, 280–288 (2015).

Luo, L., Huang, Y. & Xuan, F.-Z. Deflection behaviour of corrosion crack growth in the heat affected zone of CrNiMoV steel welded joint. Corro. Sci. 121, 11–21 (2017).

Zhao, L., Jing, H., Xu, L., Han, Y. & Xiu, J. Analysis of creep crack growth behavior of P92 steel welded joint by experiment and numerical simulation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 558, 119–128 (2012).

Xuan, F.-Z., Chen, J.-J., Wang, Z. & Tu, S.-T. Time-dependent deformation and fracture of multi-material systems at high temperature. Int. J Press. Vessel. Pip. 86, 604–615 (2009).

Héripré, E. et al. Coupling between experimental measurements and polycrystal finite element calculations for micromechanical study of metallic materials. Int. J Plast. 23, 1512–1539 (2007).

West, E. A. & Was, G. S. A model for the normal stress dependence of intergranular cracking of irradiated 316L stainless steel in supercritical water. J Nucl. Mater. 408, 142–152 (2011).

Fujii, T., Yamakawa, R., Tohgo, K. & Shimamura, Y. Analysis of the early stage of stress corrosion cracking in austenitic stainless steel by EBSD and XRD. Mater. Charact. 172, 110882 (2021).

Song, W., Liu, X., Berto, F. & Razavi, S. M. J. Low-cycle fatigue behavior of 10crni3mov high strength steel and its undermatched Welds. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 11, 661 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially sponsored by National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFC3001800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51875202), and supported by Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2023–05–49).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.: Data collection, Analysis, Method development and verification, Manuscript writing; F.Y.: Analysis, Manuscript revision; N.W.: Experiment Method development; M.-L.Z.: Project direction, Manuscript revision, Funding; F.-Z.X.: Project direction, Funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, YH., Yang, FX., Wang, N. et al. Improvement of stress corrosion cracking resistance by low cycle fatigue of a CrNiMoV steel. npj Mater Degrad 7, 58 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-023-00372-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-023-00372-3

This article is cited by

-

Fatigue failure analysis of high-strength steel in seawater corrosion environment

npj Materials Degradation (2025)

-

Effects of the stored energy inside the deformation zones of metal workpieces on the machining and service processes of machined parts: a review

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)

-

Failure Study of 420 Martensitic Stainless Steel Needle Holder with Cr Coating

Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention (2024)