Abstract

Almost all organic coatings used for corrosion protection contain various types of pigmentation, both for the sake of aesthetics and performance. By focusing on spatially resolved vibrational spectroscopy and electron microscopy, we demonstrate that the type of pigmentation has a fundamental effect on both localized and global degradation processes across the investigated coatings. Samples with white TiO2 pigments display low macroscale chemical degradation across the surface but do experience a significant change in topography. SEM-EDS imaging shows that µm-scale craters are formed around the TiO2 pigments. Nanoscale spatially resolved IR spectroscopy (AFM-IR) suggests that this local erosion is not triggered by reactions seen in coatings with other types of pigments. However, FTIR-ATR chemical imaging of coating cross sections confirmed that the TiO2 pigments also protects material beneath the surface, resulting in very shallow chemical degradation effects as compared to the other systems. Darker coatings, containing carbon black, experience moderate to high chemical degradation across the surface, and additionally the degradation propagates deep into the coatings. Overall, this paper highlights that single criteria should not be used when comparing the degradation of different coatings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A common way to protect metallic surfaces and prolong their lifetime is to apply an organic coating that isolates the metal from water and corrosive species. However, aggressive environments can cause both chemical and physical reactions in the polymer materials1,2,3,4,5. These reactions may lead to unwanted results, such as changes in aesthetics properties, surface texture, or protective properties1. An important group of protective anti-corrosion coatings are coil coatings, sometimes called color coatings. These systems are applied onto pretreated metal sheets that are coiled into rolls before being shipped to be cut, deformed, and finally employed in their intended area of use. In addition to protecting a metal substrate, they are also designed to be visually appealing by adding color and texture to the surface1,6. There are many types of coil coatings, but in general they consist of two different polymer layers. Closest to the substrate there is a primer that improves metal/coating adhesion, and above that a topcoat that isolates the underlying material from factors that cause degradation. In addition to the organic components that makes up the polymer part of the topcoat, it also contains a combination of additives to improve various properties. For example, structural agents that change the mechanical properties and add surface texture, matting agents that reduce the glossiness, solvents that act as diluents and help dissolve the other additives, as well as pigmentation that adds color. The wide variety of combinations of constituents as well as the many unique weather conditions that the coatings may be exposed to contribute to complex degradation reactions.

Chemical reactions associated with the degradation in an organic crosslinked coating are generally considered to be dependent on three main factors; UV light, the presence of water, and temperature2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. UV light may cause photodegradation in polymers as photons with a high enough energy can break chemical bonds within the polymer network. In polyester melamine-based coatings this leads to the formation of radicals and if oxygen is available formation of oxy- and peroxy-radicals and secondary polymer radicals2,9,14. The free radicals then undergo combination or disproportion, and new bonds are formed. This may result in decreased flexibility and increased brittleness due to an increase in the degree of crosslinking2,9,15,16. The presence of water, either in the form of humidity in the air or liquid water has a tendency to increase the rate of photolysis, a phenomenon called moisture enhanced photolysis (MEP)17. In addition, the presence of water also makes hydrolysis reactions possible1,17,18. Hydrolysis can break chemical bonds and also result in the formation of products that facilitate further degradation reactions. For example, when a hydrolysis reaction breaks an ether linkage in a polyester/melamine formulation, formaldehyde is formed. This facilitates the formation of formyl and hydrogen free radicals in the presence of UV light, which further leads to formation of free polymer radicals and hydroperoxides9,19. In the presence of UV light these products can result in the formation of alkoxy and hydroxy radicals, which in turn react further9. In addition to a general increase in chemical reaction rates, higher temperatures also result in increased water uptake, especially above the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the material5,7,20,21. Thermal cycling also leads to internal stresses in the coatings that may contribute to faster degradation10.

Many commercially used commercial coil coatings have some type of pigmentation1,22. In addition to their effect on aesthetic properties, pigments can also significantly affect water absorption. Depending on both the water uptake of the pigments themselves as well as the pigment-resin interactions, their presence could either increase or decrease water permeability23,24. Additionally, water transport is also highly dependent on the amount and shape of the pigments, as well as on how well dispersed they are5,24. The pigment/polymer interfaces can also act as nucleation points for defect formation in coatings during strain25,26. In terms of chemical changes, different pigments can catalyze different reaction mechanisms1,24,27,28. For example, TiO2 (titania) strongly absorbs UV radiation and reflects almost the entire visible part of the light spectra as well as infrared radiation1,29,30. These optical properties keep the coating cooler than for example black coatings under illumination from, for example, solar radiation31,32. Due to the elevated temperatures during exposure to sun, black panels also tend to have a lower measured time of wetness (ToW) as compared to white panels at similar outdoor exposures32. The lower temperatures of white pigmented coatings leads to smaller increase in the rate of degradation reactions that are facilitated by elevated temperatures, and decreased thermal stress1,28,31. However, TiO2 also acts as a photocatalyst and absorption of UV light leads to formation of electron-hole pairs, which facilitates chemical reactions with oxygen and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)1,2,29. Formation of ROS can lead to accelerated degradation of the binder adjacent to the TiO2 particles30,33,34,35,36. In some cases the presence of TiO2 pigments in an organic coating under UV-illumination is even associated with total decomposition and formation of CO229,36. Hence, such pigments are often covered with zirconia, alumina, or silica compounds to minimize the direct TiO2-polymer contact area1,37. However, even though these compounds significantly reduce the catalytic effect, it is not entirely stopped29. Another example of metal oxides that can have an impact on degradation reactions within a coating is iron oxide pigments. In the presence of UV-light and hydrogen peroxide multiple types of iron oxides catalyze Fenton’s reactions38,39,40. Fenton’s reactions lead to formation of hydroxy radicals, which may facilitate further degradation reactions in the coating.

A common way to characterize degradation in different types of weathering environments is to study the coating surface, for example by measuring coloration and glossiness, rates of chemical reactions during weathering, as well as surface roughness9,28,41,42. However, the properties of coatings can vary along the cross section depending on for example how the coating was cured and the rate of diffusion or reactive species43,44,45,46. In addition, the pigments are spread throughout the coating cross section. Therefore, any effects they have on the stability of the coating are not limited to its surface. Thus, several recent studies have considered that degradation processes can have different effects on the surface and the bulk of a coating3,33,47,48,49,50,51.

FTIR spectroscopy is a powerful technique for quantifying chemical changes that occur in coatings, and recent advances have presented multiple ways of acquiring depth resolved information on coatings with thicknesses in the range of tens of µm3,48,52,53. By quantifying the relative size of different absorption bands, it is possible to assess the distribution of different chemical species. It is also possible to assess how distinct band ratios change with exposure to aggressive environments and thereby quantify chemical degradation processes3,27,54. Through the use of various methods, such as photoacoustic (PAS) FTIR, well-controlled abrasion, or a combination of drilling and an FTIR microscope equipped with a focal plane array (FPA) detector it is also possible to determine how the coating chemistry varies with depth28,47,48,54,55.

Depending on the formulation of a coating, different bands in FTIR spectra can be used to identify and quantify degradation reactions42,56,57. In polyester melamine coatings a decrease of the normalized intensity of the band around 1550 cm−1 is often used to quantify degradation17,48,49, or to compare differences between the degradation in different coating formulations28,54. This band is attributed to quadrant stretching of the central triazine ring in hexa-methoxy methyl melamine (HMMM), contractions of C-N bonds attached to the ring, coupled with CH2 and CH3 bending vibrations58. It is also very sensitive to chemical changes in the methyl groups attached to the ring, and their surroundings27,48,59. A schematic of the HMMM molecule crosslinked into a non-specified polyester is shown in Fig. 1. Formation of one or multiple bands around 1790–1760 cm−1 after photodegradation have been observed in many coating systems based on, for example, polyesters and acrylates2,60,61. These have been attributed to the formation of different combinations of lactones, peracids, peresters, and anhydrides2,61,62,63,64.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a technique that is suitable for quantifying local surface properties such as roughness and local mechanical properties28,41,60,65. Such information is valuable since inhomogeneities in a coating, resulting from for example limited mobility of the molecules during curing conditions or surface defects66,67, may lead to localized degradation. AFM-IR is a technique that combines the nanoscale resolution of AFM with the possibility to provide chemical information about a surface. This is done by using an AFM-tip to measure minute thermal expansion, induced when a surface absorbs infrared radiation68,69,70. These nanoscale chemical assessments are one of the few that allow probing small interfacial regions in coatings, for example to determine local water uptake or mechanistic studies of interphase regions around pigments23,71. However, AFM-based techniques tend to have a limited field of view and are sensitive to excessive roughness. In contrast, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provides information on the morphology across relatively large surface areas, whilst retaining resolution on the nm-scale. In addition, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) allows simultaneous capture of local elemental information across a sample. EDS has also been combined with ion milling, which makes it possible to characterize internal interphases in a coating with high resolution. For example, between the coating and the substrate or the coating and pigmentation particles72,73.

SEM-EDS is complimentary to IR-based techniques as the elemental information can be used to easily distinguish between different inorganic oxides, whereas IR-based techniques are ideal for quantifying chemical changes28,47,48,53,54,55. The information depth of both contact mode AFM-IR and EDS are comparable. For contact mode AFM-IR the information depth in polymers has experimentally been determined to be around 1 µm in polymer materials and for SEM-EDS it is around 0.1–5 µm, depending on the acceleration voltage, analyzed element, and local density of the polymer53,69,74.

This study aims to understand how propagation of degradation into naturally weathered polyester melamine coatings is affected by the presence of different pigments. To this end, six different colors of polyester melamine coil coatings were weathered on the Swedish west coast for six years, and the resulting effects were compared. Their surfaces were analyzed using FTIR-ATR vibrational spectroscopy as well as AFM and SEM imaging. To determine how pigments affect the propagation of degradation into the bulk of the coatings, FTIR-FPA chemical imaging as well as SEM-EDS were used.

Results and discussion

Chemical degradation on the surface

Figure 2 shows ATR-FTIR spectra from the surface of the blue coating, comparing the unexposed reference with one after 6 years of weathering in a Nordic coastal environment. The exposure site is further described in the Methods section. Each spectrum is an average of three spectrum from each sample, subjected to linear baseline correction with set points at 4000, 1830 cm−1, and rescaled.

Two of the most prominent characteristic bands include the band around 1550 cm−1, and the band around 1720 cm−1. The former band is often attributed to triazine ring stretching as well as contraction of C-N attached to the ring, coupled with the CH2 and CH3 bending vibrations58,59. The intensity of this band is indicative of the presence and state of the HMMM crosslinker13,28,43,46. A schematic of the crosslinked melamine and how it is connected to the polyester resin is shown in Fig. 1. The band around 1720 cm−1 has been attributed to carbonyl stretching, and it is mainly dependent on the presence and state of the polyester resin in the coating27,44,46. Multiple changes characteristic of degradation in polyester melamine can be observed. Firstly, wide bands centered around 3300 cm−1, mainly attributed to OH stretching vibrations, increase. These bands have previously been attributed to multiple oxidation-reactions related to weathering but are generally considered to be caused by photo-degradation3,63,75. These bands partially overlap with NH stretching vibrations (several wide low intensity bands around 3000 cm−1) and CH stretching vibrations (several medium intensity bands centered around 2900 cm−1). The bands assigned to NH and CH stretching remain relatively stable during weathering. In addition, weathering also broadens the carbonyl band around 1720 cm−1. This can be attributed both to a change in the local chemical environment of the carbonyl groups as well as formation of degradation products, including acids and other carbonyl degradation product3,9,14,37. This is indicative of chemical change primarily in the polyester resin. In the region around 1760–1780 cm−1 a shoulder on the strong central carbonyl band is formed. This shoulder has been assigned primarily to anhydrides, peracids, and peresters, products that are attributed to degradation reactions related to the melamine crosslinker and the polyester resin9,14,56,57. Weathering decreases the intensity, and to some degree, broadens the band centered 1550 cm−1.

The decrease of the band around 1550 cm−1, expressed as melamine substitution functionality loss (MSFL) as well as the increase in intensity of the band around 1780 cm−1 for the differently pigmented systems are shown in Fig. 3. MSFL is expressed as a percentage, where 0% corresponds to no change in the band intensity after weathering and 100% means that the band has disappeared completely28. The MSFL-value is calculated according to Eq. (1).

Where Iref is the 1550 cm−1 band intensity normalized against the band around 1375 cm−1, and Iexp is the corresponding intensity from the weathered sample. The change of the 1780 cm−1 band is expressed as the band intensity before and after exposure, normalized against the same peak as in the MSFL calculation. The degradation of the different systems, as quantified using changes of these two band intensities, are shown in Fig. 3. A complete summary of the pigment composition in the coatings is provided in the methods section. In short, all coatings contain TiO2 except the black coating. The white coating has the highest TiO2 content, followed by blue, red, light brown, and dark brown in descending order. The black, dark brown, light brown, and red coating all contain carbon black. Both brown, blue and red coatings contain a combination of various iron oxides. Both the increase of the 1780 cm−1 band, in the lower bar chart, and the decrease of the 1550 cm−1 band indicate that the white pigmented sample is chemically comparatively stable. In terms of changes to the 1780 cm−1 band the black, dark brown, blue, and red samples all show similar changes with the light brown having a slightly larger change, although only with a small margin. However, in terms of MSFL the red sample shows a significantly lower MSFL index than the black, dark brown, light brown and blue samples.

Depth resolved chemical degradation

It has been observed that concentration of HMMM groups varies along the cross section along a cured coil coating, which affects the intensity of the normalized band around 1550 cm−1,45,46. It was proposed that this concentration difference is caused by diffusion of the HMMM to the surface to reduce the surface free energy, limited compatibility of polyester and melamine, and density differences43,45,49. This is enabled by thermal gradients but hindered by the steric forces within the system. Because of the concentration difference, the intensity of the normalized band at 1550 cm−1 in the unexposed samples may vary as a function of distance to the surface both before and after weathering of a polyester melamine coating. This also means that the reference intensities used to calculate the MSFL along the cross section will vary. To calculate these in a consistent manner for all the coating systems, the variation with respect to the distance to the surface was assumed to be linear. Linearity was assumed to make the approximation as simple as possible, and it also works relatively well for all systems.

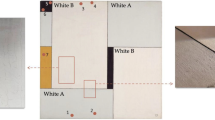

Depth resolved FTIR-measurements were performed along a drilled hole according to the schematic in Fig. 4. The geometry of the drilled hole is angled so that the horizontal distance from the edge of the hole is ten times greater than the depth. For instance, a point 150 µm from the edge, moving towards the center of the hole, corresponds to a depth of 15 µm. A detailed explanation of the experimental procedure can be found in section “FTIR–ATR and focal plane array”.

The top part of Fig. 4 shows the normalized band ratios and the linear interpolation used to calculate the reference values before and after weathering. The resulting MSFL for each of the points is shown in the bottom part of Fig. 5. Note that the x-axis shows the position in the horizontal cross section as viewed from the top of the coating. This means that the values < 0 µm on this axis are all collected from the surface of the coating and the numbers close to 200 µm show the values as you approach the primer. A summary of similar figures for the other systems is provided in the supplementary material.

In contrast, the band around 1780 cm−1 is generally assigned to a degradation product that is not present before weathering of the coating. Therefore, it is the absolute value of the intensity of this band that is relevant when assessing degradation. Normalization is performed against the band around 1375 cm−1 throughout the entire coating cross section. Note that the large carbonyl band centered at around 1720 cm−1 partially overlaps with the 1780 cm−1 band. This is why the 1780 cm−1 band also has an intensity value before exposure, as seen in Fig. 2.

In addition to the decrease of MSFL away from the surface along the cross sections, the increase in intensity of the 1780 cm−1 band is presented as an indication of chemical degradation related to the formation of several degradation products. The intensity of the 1780 cm−1 band, as well as the MSFL along the cross section of the blue pigmented samples are shown in Fig. 6. Before weathering the 1780 cm−1 band intensity as well as the MSFL are low and relatively homogeneous throughout the coating. After weathering the area closest to the surface of the coating, at the top of the heatmaps, close to y = 0, shows both elevated 1780 cm−1 band intensities and MSFL-values. The magnitude of the degradation is significantly lower further into the coating and drops to values comparable to the unexposed state close to 7 µm into the coating, or a 70 µm distance from the top of the edge of the drilled open cross section. The dark gray area in the heatmap of MSFL after weathering, around 80 µm from the edge of the drilled hole and 8 µm into the coating cross section, is indicative of a polyamide particle. The polyamide bands are present around 1640 and 1550 cm−1 and are known to interfere with calculations of MSFL54,58.

The degradation values for the black, white, dark brown, brown, blue, and red coatings are shown in the form of scatter plots in Fig. 7. Each point represents the average MSFL or 1780 cm−1 intensity as well as the standard deviation across a 1.7-µm thick slice of the coating, corresponding to a 33 × 17 µm large area in the near-horizontal cross section.

The leftmost column shows the MSFL. The values in the reference sample, green squares, generally remain close to zero throughout the cross sections and suggest that the linear correlation used to approximate the 1550 cm−1 band is appropriate. Local deviations, with large negative MSFL and large standard deviations indicate the presence of polyamide particles and are thus unrelated to the degradation of the coating54. Since there are small variations in the 1550 cm−1 band intensity across the surface, both on the µm and mm scale, the degradation values vary slightly when measured over regions with such length scales. However, the MSFL values close to the surface, around x = 0 in Fig. 7 are close to those presented in Fig. 3. The data for the weathered surface, orange circles, show similar overall patterns for all coatings. The level of degradation is highest close to the surface and gradually decreases as the bulk of the coating is approached. However, there are also important differences due to the pigment type. The degree of degradation depends on the pigment-type and is clearly lowest for the white sample. Further, depending on the pigmentation, the degradation reaches a stable value around 5–10 µm into the coating. In the white, blue, and red samples the MSFL stabilize at 0%, i.e. the bulk shows no sign of degradation. The black stabilizes at around 20%, whereas the dark and light brown samples stabilize around 10%. This indicates that an increase in MSFL can be related to both factors confined to the outermost part of the coating and factors that affect the bulk of the material. Water is not completely confined to the coating surface by the pigments23,24. This suggests that the degradation reactions related to hydrolysis can affect the state of the coating at larger depths. Similarly, temperature is also not confined to the surface and could be a contributing factor for degradation in the bulk of the coating. However UV radiation can be absorbed (or reflected) by pigmentation as well as the polymer itself, and TiO2 pigments have an especially large scattering effect1,29,30. This indicates that the degradation close to the surface, but not in the bulk, is significantly affected by incident UV light.

For all coatings the intensity of the 1780 cm−1 band is highest at the surface and gradually decreases. The intensity of the 1780 cm−1 band reaches a stable value between 5 and 10 µm into the coating, at approximately the same depth as the MSFL. However, as opposed to MSFL, none of the coatings show elevated degradation levels deeper than 10 µm. This suggests that although there is correlation between the MSFL and 1780 cm−1 band intensity, the reactions leading to these changes are triggered by different factors. One reasonable explanation would be that MSFL is more dependent on hydrolysis reactions and/or elevated temperatures as compared to the increase of the 1780 cm−1 band.

Topography and gloss retention

Gloss retention is a common way of assessing coating degradation by means of changes in light reflectivity of the surface. Figure 8 shows that the lowest gloss retention occurs in the white system. The blue and red systems show slightly higher retention, followed by the light brown and black systems, and the dark brown shows the least change. Thus, based on only gloss measurements one would conclude that the white coating is the most degraded. As shown in the previous sections, from the chemical point of view the opposite conclusion must be drawn, i.e. the white coating is the least degraded. We note that one of the major factors that affect the gloss is the topography of the sample. A higher roughness tends to result in more diffuse reflectance and thus lower gloss, with all other factors equal1,42. Indeed, as will be discussed below the white coating has the roughest surface after weathering.

An example of the topographical effects of weathering, as measured by AFM, is shown in Fig. 9. Such changes are commonly caused by material erosion. This leads to inhomogeneities in the coating, exposure of pigments that may fall out and whereby both hills and craters can be formed12,41. A selection of topographical maps is shown in the supplemental material.

Figure 10 shows the root mean square (RMS) roughness of all the pigmented coatings before and after weathering. Weathering resulted in an increase in surface roughness of all pigmented coatings. Especially the white pigmentated sample with large amounts of TiO2 showed a significant roughness increase even though the chemical indications of degradation are very low. This can also be seen in the AFM images provided in the supplementary material. After exposure, the non-white samples show mainly distinctly separated holes on the µm scale, whereas the white coating shows an uneven surface with overlapping and connected craters. When comparing Figs. 8 and 10, the white sample stands out in both cases, with the highest loss of gloss and largest roughness increase. In addition, the two brown colors showed good stability both in terms of gloss and roughness change, and the red sample being somewhere in between the white and brown samples is terms of both gloss retention and roughness after weathering. However, both the black and blue samples showed a relatively large spread in terms of surface roughness, indicating that there are local defects across these surfaces. The correlation between the chemical degradation on one hand and the surface topography and gloss on the other hand is thus poor. This can be illustrated by the fact that the most stable sample from a macroscale chemical perspective, white pigmented, was the most affected by weathering in terms of gloss and topography. Further, the light brown sample was only moderately affected in terms of roughness and gloss loss but showed the largest chemical degradation as quantified using MSFL and growth of the 1780 cm−1 band. This could have several explanations, but a contributing factor is suggested to be that white pigmentation leads to local degradation at the surface but counteracts degradation deeper into the coating. These protective properties could both be because TiO2 absorbs UV-radiation, thus preventing it from being absorbed directly by the coating resin to cause degradation reactions. Further, TiO2 reflects IR radiation which keeps the temperature lower than comparable coatings without this pigment type. However, the high surface roughness is also connected to the high TiO2 content and its photocatalytic effect, which are particularly important at the outermost part of the surface. The low degradation of the white sample deeper into the coating is discussed further on.

Elemental surface analysis

SEM-EDS images of the red sample before and after weathering are shown in Fig. 11. Pigments, as indicated by the yellow (Ti) and red (Fe) areas in the blue (C) organic resin, can be seen at the surface both before and after weathering. However, after weathering more pigments are exposed, supporting that erosion of the organic material around the pigments is a factor that increases the surface roughness41. In addition to the yellow and red pigments the amount of exposed Si from the silica matting agents increases with weathering. This is seen by the green EDS map in the rightmost part of each collection of maps. Weathering of the coatings also leads to the formation of craters of different sizes across the surfaces. The size of these craters is different for the different types of pigments. Generally, the TiO2-particles result in larger craters, whereas many iron oxide pigments are still embedded in the coating even after weathering. Clearly, the presence of TiO2-particles leads to release of pigments from the coating, explaining the high surface roughness of the white coating. This again emphasizes that that the pigmentation type plays a significant role in the degradation process during realistic outdoor weathering conditions.

Elemental cross-sectional analysis

The effect of the TiO2 pigments is further emphasized by SEM-EDS images across a cross section of the white coating as illustrated in the top row of Fig. 12. The cross section was exposed using broad ion beam (BIB) milling. Particles with diameters of ~0.1–0.2 µm, as indicated by the presence Ti (yellow) and O (blue), are surrounded by craters with diameters on the scale of 1 µm. This local erosion of material also occurs to some degree while the particles are still covered by the coating, as illustrated by the void formed around the TiO2 agglomerate on the right side of the weathered white coating. Although the TiO2 particles are coated with Al and Zr compounds to reduce their photoactivity they are still associated with local chemical degradation reactions. This could be the result of imperfections in the layer covering the TiO2 particles1 or/and degradation of the protective layers on the TiO2 particles as they are exposed to the environment. In contrast, cross sections of the black coating, shown in the second row of Fig. 12, have no metal oxide pigments and only significantly smaller carbon black particles. For this coating no craters can be seen after weathering. Since the carbon black particles do not result in any elemental contrast EDS images are not shown. In the third row of the figure an EDS map of the cross section of the blue coating before and after weathering is displayed. Here we can also see that cavities at the surface are formed, although to a lower extent because of the lower TiO2 pigment concentration. Note that the Ti-content indicated at the surface is caused by redeposition of the material from the cross section from the BIB milling.

Chemical nanoscale surface analysis

To further investigate the effects of the TiO2-pigments, AFM-IR measurements of the blue coating were conducted. This coating was chosen because the pigmentation content was largely based on TiO2, but the topography after weathering did not interfere with the measurements as much as in the white samples. Before weathering, no major variation in the surface chemistry on the nanoscale level could be decerned. This is illustrated in Fig. 13 which shows that the normalized band intensities for the band at 1550 cm−1(I1550/11375) is 2.40 ± 0.12. A topographical map is shown at the top left side of the figure and to the right spectra from the different areas, as indicated by the different colors, can be seen. The location of the different bands is similar to those collected using FTIR–ATR, presented in Fig. 2. The optimal sample thickness for contact mode AFM-IR measurements is on the scale of hundreds of nm68,69,70, but because of the topography, especially for the weathered sample, preparation of samples with that geometry was not practical. Therefore, measurements were performed directly on the painted steel samples. This probably influences the noise level of the spectra, may cause saturation of the IR-bands and affect the relative intensities of the bands. At the bottom left of Fig. 13 the normalized intensity of the different spectra is shown in no particular order to indicate the spread of band intensities. It is important to note that comparing the band intensities between different measurement areas is challenging. Since each laser chip in the QCL is optimized individually for each sample, each optimization process could result in changes to the relative intensity of the different parts of the bands. Comparison of relative band intensities for different experiments should therefore be made with caution and is not further discussed here.

Topographical and spectroscopic AFM-IR measurements of the same blue coating after weathering close to craters formed around TiO2 pigments are shown in Fig. 14. Just like indicated by the AFM and SEM images, surface roughness increases with weathering and leads to formation of 300–600 nm deep craters. This is shown in the topographical map at the top left side of the figure. In comparison to the spectra collected before weathering, the carbonyl band around 1720 cm−1 is somewhat broader and the band centered around 1550 cm−1 are flattened. This is consistent with macroscale FTIR–ATR measurements. When comparing the spectra form the surface of the weathered coating (blue, green, gray, and pink) and the bottom of craters (gold and orange) both types of areas show some variation in the band centered around 1550 cm−1. There is no distinct trend indicating that the shape of this band is affected by the location from which the spectrum is collected from. This is also shown by the intensities of the 1550 cm−1 band as normalized against the band around 1375 cm−1 at the bottom left of Fig. 14. The 1550 cm−1 band intensities from the cavities have an average value of 1.87 ± 0.19, whereas the other intensities, from the surface of the coating, have an intensity of 1.95 ± 0.14. This indicates that the degradation as measured using MSFL is not significantly affected in the vicinity of TiO2 particles and quite uniform over the surface. It suggests that degradation reactions caused by the TiO2 particles result in degradation products with low molecular mass or easily rinsed off during rain, condensation, or other similar events. Another possible reason could be that TiO2 catalyzes even more severe reactions. Polymer degradation in the presence of TiO2 has in some cases shown to release CO2 gas29,36, showing that combustion-like reactions can occur. This could be one reason why the MSFL from the surfaces of the weathered white coating was low, even though the topography was severely affected by weathering. When TiO2 is present, UV radiation is to some extent absorbed by the TiO2 pigments and may reduce the penetration of UV-light into the coating which also can lead to lower MSFL as measured by FTIR–ATR from the outermost 1–3 µm of the coating.

The effects of pigment type and concentration

The experimental results show clearly that the type of pigment and its content affect both the degradation effects on the surface and in depth of coil coatings exposed during natural weathering. Chemical degradation at the surface of the coatings, as shown in Fig. 3, indicates that there is an inverse correlation between the wt% of pigments and how degraded the coatings are4. This is presumably because inorganic oxide pigments can effect both the water absorption and scattering or absorption of incoming radiation1,4,35. An outlier in this respect is the black coating. Although it contains less than half as much pigmentation as compared to the two brown ones, or the blue coating, less degradation is induced by weathering (as measured using 1780 cm−1 band intensity and MSFL).

Depth resolved FTIR-imaging shows considerable differences in the chemical degradation between the coatings colored with different pigment types and pigment volume concentration. The depth resolved degradation effects were larger and extended to larger depth for coatings without TiO2 and lower pigment content, as illustrated in Fig. 7. For the white coating that exclusively contained TiO2, FPA-imaging confirms that the degradation is limited to the surface of the coating. Both the increase of the band around 1780 cm−1 and the MSFL reached the outermost 5 µm of the coating after 6 years of weathering, a shallower degradation than in all other formulations. This indicates that the large volume concentration of TiO2 pigments limits the penetration depth of the degradation. Presumably this is because the TiO2 pigments strongly absorb UV-radiation, thus preventing UV-induced degradation in the coating itself2,9. TiO2 also reflects infrared and visible light that will lead to heating of the sample and an increase in reaction rates. However, SEM-EDS results shown in Figs. 11 and 12 show that local erosion occurs around TiO2 particles, suggesting that TiO2 causes local erosion processes. The craters indicate that although the white TiO2 pigments are covered with Zr and Al compounds to decrease photoactivity and decrease the rate of degradation reactions, the coverage is insufficient. TiO2 is a strong photocatalyst, and when it absorbs UV light, it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). In moist or humid conditions, superoxide ions and hydroxyl radicals can form on the TiO2 surface through reactions with oxygen and water2,35. These highly reactive radicals can then interact with carbon–carbon or carbon–hydrogen bonds in the resin close to the TiO2 particles. This interaction breaks down the polymer network into smaller molecules and may eventually oxidize it entirely, forming CO2 and water2,30,36. Formation of smaller and lower molecular weight degradation products often wash out of the paint film, which would be an explanation for the craters around the photocatalytic TiO2 particles seen in the topographical map in Fig. 14. The local degradation effects around the particles were not observed for the other pigments, e.g. the iron oxides. This supports the argument that iron oxide pigments have a significantly different effect on the degradation process in coatings as compared to TiO2.

Figure 6 also shows that the coatings with >0.1 wt% carbon black have some degree of degradation, as judged from the MSFL values, throughout the entire coating. This includes the black, the dark brown, and the light brown coating formulations. Carbon black is a strong absorber of both visible and IR light, which means that darker coatings with higher amount of carbon black tends to have higher temperatures during weathering31. Higher temperatures are associated with an increase of chemical reactions as well as water absorption in the coating7. These degradation-inducing factors could work against the protective effects of the carbon black inside the cross section of the darker coating formulations. It is however noteworthy that only the MSFL-values are elevated, and not the intensity of the 1780 cm−1 band. This suggests that different stimuli trigger the two degradation indicators to different degrees. Water and elevated temperatures are presumably present along the entire cross section whereas the amount of UV radiation decreases the further into the coating due to light absorption and scattering both from the polymer itself as well as the pigmentation24,35,76. This suggests that MSFL would be more sensitive to hydrolysis or thermally triggered reactions whereas an increase of the 1780 cm−1 band probably is mainly triggered by UV radiation49. The higher temperatures during weathering induced by carbon black could increase water uptake in the coatings, especially above the glass transition temperature Tg7,21. Increased water uptake could worsen the photolysis reactions though MEP which would result in elevated MSFL close to the surface. Further in the presence of water could trigger hydrolysis reactions also throughout the coating. In contrast, the limited penetration depth of UV radiation would prevent an increase of the 1780 cm−1 band further into the coating. It can also be noted that degradation of the coating can lead to increase of water uptake51. An effect which should be more pronounced for the black coating in comparison with the white.

Methods

Materials

All coatings were applied onto polyester melamine primed hot-dipped galvanized steel sheets with a titanium hexafluoride-based pretreatment. The topcoats were based on commercial OH-functional polyester resins containing isophthalic acid, phthalic anhydride, neopentyl glycol, ethylene glycol, and adipic acid. All coatings contained rapeseed methyl ester (RME) added as a reactive diluent. They were crosslinked with HMMM at a ratio of 85:15 and applied using a wire rod to a nominal dry thickness of 20 µm. Curing was performed at 360 °C to a peak metal temperature (PMT) of 232–241 °C. The pigment contents of the different coatings and their colors are provided in Table 1. In addition to the pigments, all systems have added matting agents in the form of silica.

Weathering conditions

Weathering was conducted at Bohus-Malmön on the Kvarnvik site on the Swedish west coast 350 m from the Atlantic. Environmental parameters from the site across the six years of exposure are summarized in Table 2. This includes the yearly average temperature and relative humidity (RH), as well as the total incident solar radiation per unit area, and amount of precipitation. The time of wetness (ToW) is a measurement of the amount of time a surface is covered by adsorbed and/or liquid films of electrolyte. It was approximated by the time the relative humidity was above 80% and the temperature greater than 0 °C in accordance with ISO 9223. The ToW is given as a percentage, indicating how much of the total year fulfilled the requirements given in the standard. During the weathering, reference samples were stored at room temperature in laboratory conditions.

Optical measurements

Gloss measurements were performed on three areas for each sample using an Elcometer 408 at a reflection angle of 60°.

Surface roughness

Topographical measurements were performed using a Bruker NanoIR3 with PR-EX-T125-10 probes. The probes have a nominal tip radius on 20 nm, resonant frequency between 200 and 400 kHz and a spring constant between 13 and 77 N/m. Each measurement was performed in triplicates across 32 × 32 µm areas using a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels. Data processing and roughness measurements were performed in Gwyddion v. 2.61.

SEM cross sections

Vertical cross-sections for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS) analysis were prepared using an Ilion+ Advantage Precision Cross-Section System (Model 693, Gatan Inc.). Specimens were cut into ~5 × 5 mm sections using a guillotine. The metal substrates were then thinned through mechanical polishing on a Struers RotoPol-21 system with Struers FEPA P #500 silicon carbide abrasive paper. Each sample was mounted onto titanium blades using a conductive silver suspension (Agar silver suspension with Ag flakes in 4-methylpentan-2-one). Argon ion milling was performed at 6 kV for roughly 3 h, achieving a milling depth of ~60–80 μm over a 500 μm × 500 μm area.

Prior to SEM analysis, samples were sputtered with a 5–10 nm carbon layer using an Agar Carbon Coater to mitigate charging effects. SEM imaging and EDS measurements were conducted on a Zeiss Gemini SEM equipped with a Bruker QUANTAX FlatQUAD EDS detector. EDS data were collected at an accelerating voltage of 3 kV and a beam current of 1.2 nA.

FTIR–ATR and focal plane array

FTIR attenuated total reflection (ATR)spectroscopy of the sample surfaces were conducted using a Bruker Vertex 70 with a Specac Quest ATR accessory and a replaceable diamond internal reflection element. Both backgrounds and measurements were performed at a resolution of 4 cm−1 using 256 scans. Three measurements were performed on different areas across the unexposed reference samples, as well as on samples weathered for 6 years at Bohus-Malmön. The information depth of the measurements for this setup varies with wavenumber but is around 0.6 µm around 3200 cm−1 and around 1.3 µm around 1600 cm−1 77,78.

A Hyperion 3000 microscope accessory was used to make depth resolved measurements and map the cross sections. To achieve this, the microscope had a focal plane array (FPA) detector with an array of 64 × 64 pixels and an ATR objective with a germanium internal reflection element (IRE). The objective had a field of view of ~34 × 34 µm and the spectral data collected was for each measurement binned to result in a 16 × 16 spectral arrays. Both backgrounds and measurements were performed at a resolution of 8 cm−1 using 500 scans. Near-horizontal cross sections were opened up in each coating sample by means of a high angle (~5.7°) coating drill, as described in ref. 48, and seven successive measurements were made along the surface and into the cross section of each sample. After this, data from the surface of the coating, as well as data that could contain information from the primer, was excluded from further analysis. This resulted in an ~34 µm wide and 170 µm long area reaching into the coating and containing 16 × 81 spectra. This correspond to data from the outermost 17 µm of the topcoat being analyzed.

AFM-IR

Nanoscale chemical analysis was performed on a Bruker NanoIR3 with gold coated PR-EX-nIR2–10 contact mode probes. Each probe had a resonance frequency of 13 ± 4 kHz, a spring constant between 0.07 and 0.4 N/m and a nominal tip radius of 20 nm. Measurements were performed on the blue pigmented samples across areas around 4.5 × 4.5 µm2 with a resolution of 512 × 512 pixel points. The images were then cropped to 4 × 4 µm2, compensating for drift between the measurements. Scan rates were varied between 0.3 and 0.5 Hz to minimize artefacts. During imaging and spectral acquisition, the laser power was varied between 1.79 and 9.83% of the maximum laser power of ~800 mW. The duty cycle, or amount of time the Quantum cascade laser (QCL) was pulsing, was between 1 and 2%. Data processing, including removal of step-discontinuities, was performed in Analysis studio 3.17 and in Gwyddion v. 2.61.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Hare, C. H. Paint film degradation: mechanisms and control (Society for Protective Coatings (SSPC), 2001).

Rabek, J. F. Polymer Photodegradation: Mechanisms and experimental methods (Springer Science, 1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1274-1.

Mallégol, J., Poelman, M. & Olivier, M. G. Influence of UV weathering on corrosion resistance of prepainted steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 61, 126–135 (2008).

Van Der Wel, G. K. & Adan, O. C. G. Moisture in organic coatings - a review. Prog. Org. Coat. 37, 1–14 (1999).

Obereigner, B. et al. Key parameters and mechanism of blistering of coil-coatings in humid-hot laboratory environments. Prog. Org. Coatings 175, 107373 (2023).

Sander, J. Coil coating (Vincentz Network, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783748602231.

Caussé, N. et al. Ageing processes of coil-coated materials: Temperature-controlled electrochemical impedance analysis. Prog. Org. Coatings 183, 107682 (2023).

Jacques, L. F. E. Accelerated and outdoor/natural exposure testing of coatings. Prog. Polym. Sci. 25, 1337–1362 (2000).

Batista, M. A. J., Moraes, R. P., Barbosa, J. C. S., Oliveira, P. C. & Santos, A. M. Effect of the polyester chemical structure on the stability of polyester-melamine coatings when exposed to accelerated weathering. Prog. Org. Coat. 71, 265–273 (2011).

Prosek, T. et al. The role of stress and topcoat properties in blistering of coil-coated materials. Prog. Org. Coat. 68, 328–333 (2010).

Fedrizzi, L., Bergo, A., Deflorian, F. & Valentinelli, L. Assessment of protective properties of organic coatings by thermal cycling. Prog. Org. Coat. 48, 271–280 (2003).

Yang, X. F. et al. Weathering degradation of a polyurethane coating. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 74, 341–351 (2001).

Bauer, D. R. Melamine/formaldehyde crosslinkers: characterization, network formation and crosslink degradation. Prog. Org. Coat. 14, 193–218 (1986).

Lesage, N., Vienne, M., Therias, S. & Bussière, P. Photoageing and durability of a polyester-melamine organic coating on steel: New insight into degradation mechanisms. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 229, 110944 (2024).

Hill, L. W., Korzeniowski, H. M., Ojunga-Andrew, M. & Wilson, R. C. Accelerated clearcoat weathering studied by dynamic mechanical analysis. Prog. Org. Coat. 24, 147–173 (1994).

Johnson, B. W. & McIntyre, R. Analysis of test methods for UV durability predictions of polymer coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 27, 95–106 (1996).

Nguyen, T., Martin, J., Byrd, E. & Embree, N. Relating laboratory and outdoor exposure of coatings III. Effect of relative humidity on moisture-enhanced photolysis of acrylic-melamine coatings. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 77, 1–16 (2002).

Bauer, D. R. Degradation of organic coatings. I. Hydrolysis of melamine formaldehyde/acrylic copolymer films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 27, 3651–3662 (1982).

Gamage, N. J. W., Hill, D. J. T., Lukey, C. A. & Pomery, P. J. Factors affecting the photolysis of polyester-melamine surface coatings. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 81, 309–326 (2003).

Nguyen, A. S. et al. Determination of water uptake in organic coatings deposited on 2024 aluminium alloy: comparison between impedance measurements and gravimetry. Prog. Org. Coat. 112, 93–100 (2017).

Roggero, A. et al. Thermal activation of impedance measurements on an epoxy coating for the corrosion protection: 2. electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study. Electrochim. Acta 305, 116–124 (2019).

Cocuzzi, D. A. & Pilcher, G. R. Ten-year exterior durability test results compared to various accelerated weathering devices: Joint study between ASTM International and National Coil Coatings Association. Prog. Org. Coat. 76, 979–984 (2013).

Morsch, S., Emad, S., Lyon, S. B., Gibbon, S. R. & Irwin, M. The location of adsorbed water in pigmented epoxy-amine coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 173, 107223 (2022).

Perera, D. Y. Effect of pigmentation on organic coating characteristics. Prog. Org. Coat. 50, 247–262 (2004).

Bastos, A. C., Ostwald, C., Engl, L., Grundmeier, G. & Simões, A. M. Formability of organic coatings - an electrochemical approach. Electrochim. Acta 49, 3947–3955 (2004).

Bastos, A. C. & Simões, A. M. P. Effect of uniaxial strain on the protective properties of coil-coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 46, 220–227 (2003).

Zhang, W. R., Lowe, C. & Smith, R. Depth profiling of coil coating using step-scan photoacoustic FTIR. Prog. Org. Coat. 65, 469–476 (2009).

Zhang, W. R., Hinder, S. J., Smith, R., Lowe, C. & Watts, J. F. An investigation of the effect of pigment on the degradation of a naturally weathered polyester coating. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 8, 329–342 (2011).

Christensen, P. A., Dilks, A., Egerton, T. A. & Temperley, J. Infrared spectroscopic evaluation of the photodegradation of paint Part I The UV degradation of acrylic films pigmented with titanium dioxide. J. Mater. Sci. 34, 5689–5700 (1999).

Croll, S. DLVO theory applied to TiO2 pigments and other materials in latex paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 44, 131–146 (2002).

Fischer, R. M. & Ketola, W. D. Surface temperatures of materials in exterior exposures and artificial accelerated tests. In Accelerated and outdoor durability testing of organic materials, ASTM STP1202 (American Society for Testing and Materials, 1994). https://doi.org/10.1520/stp18174s.

Hoseinpoor, M., Prošek, T. & Mallégol, J. Comprehensive assessment of time of wetness on coil-coated steel sheets. Corros. Sci. 244, 112641 (2025).

Morsch, S., Van Driel, B. A., Van Den Berg, K. J. & Dik, J. Investigating the photocatalytic degradation of oil paint using ATR-IR and AFM-IR. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 10169–10179 (2017).

Diebold, M. P. Effect of TiO2 pigment on gloss retention: a two-component approach. CoatingsTech 6, 32–39 (2009).

Diebold, M. P. Optimizing the benefits of TiO2 in paints. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 17, 1–17 (2020).

Watanabe, N. et al. Photodegradation mechanism for bisphenol A at the TiO2/H2O interfaces. Chemosphere 52, 851–859 (2003).

Bauer, D. R., Mielewski, D. F. & Gerlock, J. L. Photooxidation kinetics in crosslinked polymer coatings. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 38, 57–67 (1992).

Urbanczyk, M. M., Bester, K., Borho, N., Schoknecht, U. & Bollmann, U. E. Influence of pigments on phototransformation of biocides in paints. J. Hazard. Mater. 364, 125–133 (2019).

Reza, K. M., Kurny, A. & Gulshan, F. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by magnetite+H2O2+UV process. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 7, 325–329 (2016).

Xiao, J., Guo, S., Wang, D. & An, Q. Fenton-like reaction: recent advances and new trends. Chem. A Eur. J. 30, e202304337 (2024).

Biggs, S., Lukey, C. A., Spinks, G. M. & Yau, S. T. An atomic force microscopy study of weathering of polyester/melamine paint surfaces. Prog. Org. Coat. 42, 49–58 (2001).

Wernståhl, K. M. Service life prediction of automotive coatings, correlating infrared measurements and gloss retention. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 54, 57–65 (1996).

Hirayama, T. & Urban, M. W. Distribution of melamine in melamine/polyester coatings; FT-IR spectroscopic studies. Prog. Org. Coat. 20, 81–96 (1992).

Gamage, N. J. W., Hill, D. J. T., Lukey, C. A. & Pomery, P. J. Distribution of melamine in polyester-melamine surface coatings cured under nonisothermal conditions. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 42, 83–91 (2004).

Greunz, T. et al. A study on the depth distribution of melamine in polyester-melamine clear coats. Prog. Org. Coat. 115, 130–137 (2018).

Hamada, T., Kanai, H., Koike, T. & Fuda, M. FT-IR study of melamine enrichment in the surface region of polyester/melamine film. Prog. Org. Coat. 30, 271–278 (1997).

Leidlmair, D. et al. Elemental and chemical depth profiling of high-build single-component (1K) polyester-polyurethane coil coatings. Prog. Org. Coatings 179, 107490 (2023).

Persson, D., Heydari, G., Edvinsson, C. & Sundell, P. E. Depth-resolved FTIR focal plane array (FPA) spectroscopic imaging of the loss of melamine functionality of polyester melamine coating after accelerated and natural weathering. Polym. Test. 86, 106500 (2020).

Zhang, W. R., Zhu, T. T., Smith, R. & Lowe, C. A non-destructive study on the degradation of polymer coating I: step-scan photoacoustic FTIR and confocal Raman microscopy depth profiling. Polym. Test. 31, 855–863 (2012).

Zhang, W., Smith, R. & Lowe, C. Confocal Raman microscopy study of the melamine distribution in polyester-melamine coil coating. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 6, 315–328 (2009).

Jero, D. et al. Degradation of polyester coil-coated materials by accelerated weathering investigated by FTIR-ATR chemical imaging and impedance analysis. Prog. Org. Coat. 199, 108953 (2025).

Gonon, L., Mallegol, J., Commereuc, S. & Verney, V. Step-scan FTIR and photoacoustic detection to assess depth profile of photooxidized polymer. Vib. Spectrosc. 26, 43–49 (2001).

Ernstsson, M. & Wärnheim, T. Surface analytical techniques applied to cleaning processes. In: Handbook for cleaning/decontamination of surfaces, 747–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044451664-0/50023-1 (2007).

Wärnheim, A. et al. Depth-resolved FTIR-ATR imaging studies of coating degradation during accelerated and natural weathering─influence of biobased reactive diluents in polyester melamine coil coating. ACS Omega 7, 23842–23850 (2022).

Adema, K. N. S. et al. Depth-resolved infrared microscopy and UV-VIS spectroscopy analysis of an artificially degraded polyester-urethane clearcoat. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 110, 422–434 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Maxted, J., Barber, A., Lowe, C. & Smith, R. The durability of clear polyurethane coil coatings studied by FTIR peak fitting. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 98, 527–534 (2013).

Gerlock, J. L., Smith, C. A., Cooper, V. A., Dusbiber, T. G. & Weber, W. H. On the use of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and ultraviolet spectroscopy to assess the weathering performance of isolated clearcoats from different chemical families. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 62, 225–234 (1998).

Socrates, G. Infrared characteristic group frequencies (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1994).

Larkin, P. J., Makowski, M. P., Colthup, N. B. & Flood, L. A. Vibrational analysis of some important group frequencies of melamine derivatives containing methoxymethyl, and carbamate substituents: Mechanical coupling of substituent vibrations with triazine ring modes. Vib. Spectrosc. 17, 53–72 (1998).

Wärnheim, A. et al. Nanomechanical and nano-FTIR analysis of polyester coil coatings before and after artificial weathering experiments. Prog. Org. Coat. 190, 108355 (2024).

Wilhelm, C. & Gardette, J. L. Infrared analysis of the photochemical behaviour of segmented polyurethanes: 1. Aliphatic poly(ester-urethane). Polymers38, 4019–4031 (1997).

Allen, N. S., Parker, M. J., Regan, C. J., McIntyre, R. B. & Dunk, W. A. E. The durability of water-borne acrylic coatings. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 47, 117–127 (1995).

Bauer, D. R. & Briggs, L. M. IR spectroscopic studies of degradation in cross-linked networks. Charact. Highly Crosslinked Polym. 243, 271–284 (1984).

Maetens, D. Weathering degradation mechanism in polyester powder coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 58, 172–179 (2007).

He, Y. et al. Nano-scale mechanical and wear properties of a waterborne hydroxyacrylic-melamine anti-corrosion coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 457, 548–558 (2018).

Zee, M., Feickert, A. J., Kroll, D. M. & Croll, S. G. Cavitation in crosslinked polymers: Molecular dynamics simulations of network formation. Prog. Org. Coat. 83, 55–63 (2015).

Kroll, D. M. & Croll, S. G. Influence of crosslinking functionality, temperature and conversion on heterogeneities in polymer networks. Polymers79, 82–90 (2015).

Dazzi, A. et al. AFM-IR: combining atomic force microscopy and infrared spectroscopy for nanoscale chemical characterization. Appl. Spectrosc. 66, 1365–1384 (2012).

Baldassarre, L. et al. Mapping the amide I absorption in single bacteria and mammalian cells with resonant infrared nanospectroscopy. Nanotechnology 27, 075101 (2016).

Schwartz, J. J., Jakob, D. S. & Centrone, A. A guide to nanoscale IR spectroscopy: resonance enhanced transduction in contact and tapping mode AFM-IR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 5248–5267 (2022).

Morsch, S. et al. Molecular origins of epoxy-amine/iron oxide interphase formation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 613, 415–425 (2022).

Ngo, S., Lowe, C., Lewis, O. & Greenfield, D. Development and optimisation of focused ion beam/scanning electron microscopy as a technique to investigate cross-sections of organic coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 106, 33–40 (2017).

Saarimaa, V., Virtanen, M., Laihinen, T., Laurila, K. & Väisänen, P. Blistering of color coated steel: use of broad ion beam milling to examine degradation phenomena and coating defects. Surf. Coatings Technol. 448, 128913 (2022).

Lahiri, B., Holland, G. & Centrone, A. Chemical imaging beyond the diffraction limit: experimental validation of the PTIR technique. Small 9, 439–445 (2013).

Allen, N. S. et al. Photoinduced chemical crosslinking activity and photo-oxidative stability of amine acrylates: photochemical and spectroscopic study. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 73, 119–139 (2001).

McClelland, J. F., Jones, R. W., Luo, S. & Seaverson, L. M. A Practical guide to FT-IR photoacoustic spectroscopy. In Practical sampling techniques for infrared analysis (CRC Press, 1993). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003068044-5.

Griffiths, P. R. & de Haseth, J. A. Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. In: Fourier transform infrared spectrometry, 2nd ed. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007). https://doi.org/10.1002/047010631X.

Van Krevelen, D. W. Properties of polymers. In Properties of polymers (Elsevier, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-054819-7.00043-1.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by SSF, Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research grant FID18-0034 and the Hugo Carlsson research fund. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W. compiled the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and performed quantitative data analysis and interpretation. D.P. and V.S. interpreted data and edited the manuscript. G.H., P.-E.S., P.M.C., and C.M.J. revised the manuscript, contributed expertise, as well as additional data interpretation. T.D. contributed expertise and made the samples. A.W. and D.P performed sample analysis except for SEM/EDS which was performed by V.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wärnheim, A., Saarimaa, V., Heydari, G. et al. Multiscale analysis of pigment effects on weathering of polyester coatings: from nanoscale chemistry to macroscale performance. npj Mater Degrad 9, 66 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00617-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00617-3