Abstract

This study electroplates a 2 μm thick Al layer on mild steel, then uses wire-arc directed energy deposition (DED) to deposit Cu-4.2Sn alloy, forming a composite material which is subsequently cold-rolled. It investigates the microstructure, mechanical properties, and tribological behavior before and after rolling, along with underlying mechanisms. It indicates that Al coating completely suppresses penetration cracks on the steel side of the tin bronze/steel bimetal. After rolling, tin bronze grains are significantly refined (from 47.6 μm to 15.2 μm) with numerous twins formed, reducing matrix dislocation density. Compared to wire-arc DED alloy, rolled alloy hardness increases by 78%, yield strength by 51%, and tensile strength by 30%. Tribological tests indicate, under dry friction and simulated seawater conditions, the rolled alloy’s coefficient of friction (COF) and mass loss decrease by 30% and 24% respectively. Analysis of corrosion-friction synergy reveals interaction loss accounts for 13%, dominated by friction-promoted corrosion (11%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to excellent fatigue resistance, wear resistance, tin bronze is widely used in high wear-resistant structural components such as plain bearings, axle shafts, guide rails and rocker arms1,2. As a bearing material, tin bronze is often composite with steel plate to form tin bronze/steel bimetallic material. In recent years, with the innovation of material preparation technology, coating techniques such as arc spraying3, plasma spraying4, laser cladding5, and cold spraying technology6,7 have become mainstream methods for preparing tin bronze alloy layers on steel substrates, gradually replacing traditional techniques like powder sintering and continuous casting and rolling technology. However, the fusion cladding layer prepared by arc spraying and plasma spraying has defects such as oxidation, holes and unmelted particles; laser cladding realizes metallurgical bonding, but the process cost is high and there are problems such as over-thickness of the fusion zone, holes and thermal cracks; the cold spraying process overcomes the oxidation and thermal deformation problems of the traditional thermal deposition process, but it fails to form a complete metallurgical bonding, and there is a certain degree of porosity in the coating.

Wire-arc DED is a process that uses an arc as a heat source to melt welding wire material. By rapidly scanning the surface of dissimilar metal substrates with low line energy, molten droplets transition into micro-melt pools and solidify quickly, resulting in a material layer with special properties and achieving strong bonding between the cladding layer and the substrate8. The thermal input of this process lies between that of arc welding and arc spraying. The micro-melt pool on the substrate surface moves with the arc, and during the rapid heating and cooling process, the cladding layer forms a dense and uniform non-equilibrium solidified structure, endowing it with excellent wear resistance and corrosion resistance. Currently, arc deposition processes represented by cold metal transfer (CMT) technology have been extensively studied for the preparation of nickel-based alloys, copper alloys, and babbitt alloys9,10,11. For example, Zhou et al. used this technology to prepare babbitt alloys and NAB/steel bimetallic composite materials, both of which demonstrated significant performance advantages12,13,14. However, during service, although the tin bronze layer prepared using the wire arc DED technology possesses the unique advantage of non-equilibrium solidification microstructure, its room-temperature tensile strength and hardness fail to meet the increasingly stringent design specifications for high-performance military engine bearing materials without subsequent treatment. Especially in sliding bearing applications in corrosive environments such as ship propulsion bearings and submarine oil and gas extraction equipment, the material surface is simultaneously subjected to electrochemical corrosion and friction damage15,16. This manifests as a significant weakening of grain boundary bonding strength after the penetration of corrosive media, leading to friction-induced fatigue cracks rapidly propagating along tin-enriched phase aggregation zones, forming a corrosion-wear coupled failure mechanism. This composite damage mode is difficult to effectively suppress through surface coating technology under traditional lubrication conditions, and has become the core bottleneck constraining the application of tin bronze in severe corrosion-friction environments. Currently, scholars have adopted plastic deformation processes such as compression, spinning, and extrusion to process tin-bronze alloys. For example, Ebrahimi et al. 17 used equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) to process as-cast dilute Cu-Sn alloys, improving corrosion resistance by 182% via grain refinement. Moharami18 found that cumulative rolling bonding (ARB) could reduce the porosity of CuSn10P1 alloy, refine grain size to 6.5–22 μm, and shift the wear mechanism from predominantly adhesive/abrasive wear to oxidative/mild abrasive wear, resulting in a significant reduction in wear rate. Hui et al. 19 obtained Cu9.7Sn tubes with ultrafine grains and 753 MPa tensile strength through thermal spinning.

Currently, extensive research has been conducted on the wear behavior of tin bronze; however, there remains a significant gap in research on corrosion-wear behavior following plastic deformation. Therefore, this study aims to enhance the strength and wear resistance of the alloy by adjusting the microstructure of the tin bronze layer through rolling-induced line-arc directed energy deposition (DED), while conducting an in-depth analysis of wear behavior under corrosive conditions to elucidate the intrinsic mechanisms linking rolling-induced microstructural changes to service performance metrics (including strength and corrosion-wear resistance). These findings provide a theoretical basis for addressing failure challenges in harsh operating environments such as marine equipment and chemical machinery, thereby expanding the application scope of such materials in high-end equipment fields.

Results and discussion

Microstructure

Figure1 shows the cross-sectional morphology of the tin bronze/steel. The element distribution map shows that there are penetration cracks mainly composed of Cu and Sn on the steel base side. In contrast, Fig. 1g−l shows the cross-sectional morphology of a tin bronze deposition layer wire-arc deposited on an Al-plated steel substrate. A transition layer consisting mainly of Al with a thickness of approximately 6-7 μm was formed at the interface, and the penetration cracks at the interface disappeared. It indicates that during the wire-arc deposition process, the steel substrate is in direct contact with a liquid phase rich in Al but low in Cu and Sn, rather than liquid tin bronze. The enrichment of Al at the interface effectively blocks the direct contact between Cu, Sn, and especially Sn-which significantly promotes the formation and propagation of penetration cracks-and the steel substrate, thereby inhibiting the initiation and propagation of penetration cracks.

Figure 2a show the calculated strengthening energies of Cu-Sn and Cu-Al atoms at Fe grain boundaries. The strengthening energies of both systems are positive, indicating that the diffusion of these atoms into Fe grain boundaries weakens the grain boundary strength. Furthermore, their weakening effects are primarily due to chemical contributions, leading to significant changes in the interatomic interactions at Fe grain boundaries. Additionally, in these two systems, the strengthening energy, mechanical contribution, and chemical contribution of the Cu-Al system are significantly lower than those of the Cu-Sn system, indicating that while the Cu-Al system may weaken Fe grain boundaries to some extent, it poses a relatively minor threat to grain boundary strength. In contrast, the strengthening energy of the Cu-Sn system is relatively high, resulting in significant weakening of grain boundaries, particularly due to the combined effect of Cu and Sn atoms. This is primarily because the atomic radius of Sn differs significantly from that of Fe, leading to severe local distortion. Figure 2b shows the charge density distribution at pure Fe grain boundaries and Fe grain boundaries containing Cu and other atoms. The upper part shows the charge density at Cu-containing grain boundaries, while the lower part shows the charge density at grain boundaries containing other atoms. The combined effect of Cu and Sn atoms significantly reduces the charge density at grain boundaries, particularly between Fe(1) and Fe(-1), resulting in a noticeable weakening of the strength of Fe grain boundaries (Fig. 2(b2)). Therefore, the substrate Fe grain boundaries are easily pulled apart under the thermal stress of arc deposition, providing a pathway for atoms in the liquid tin bronze to spread along the grain boundaries. Cu atoms and Sn atoms diffuse into the Fe grain boundaries, leading to the rapid propagation of penetration cracks. In contrast, the combined effect of Cu and Al atoms does not significantly weaken the charge density between Fe(1)-Fe(-1), and the Fe(1)-Fe(-1) bond retains its high strength, thus posing a smaller threat to grain boundary strength, and penetration cracks are effectively suppressed.

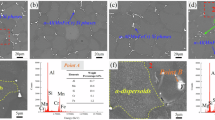

Figure 3 shows the microstructure of the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn and the rolled alloy. The SEM and TEM images reveal that the Cu-4.2Sn alloy contains almost no precipitates, likely due to the rapid non-equilibrium cooling during wire-arc deposition, which suppresses precipitation of the secondary phase. During wire-arc DED process, high-temperature droplets (liquid Cu-Sn alloy) solidify rapidly at cooling rates of up to 10³–10⁵ K s−120,21, severely limiting atomic diffusion. Although the equilibrium solid solubility of Sn in Cu at room temperature is only about 0.5%, rapid cooling “freezes” Sn atoms in the Cu matrix, forming a metastable supersaturated solid solution rather than precipitating equilibrium phases. This phenomenon is similar to the formation of supersaturated α(Al) solid solutions in rapidly solidified aluminum alloys22. Therefore, the amount of second phase (Cu3Sn) precipitated in the alloy is extremely small. Figure 3h shows the presence of a large number of dislocations in the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn matrix. This may be due to the formation of supersaturated solid solution by rapid solidification, the alloy produces lattice distortion, which directly increases the dislocation density; simultaneously, the thermal stresses in the alloy aggravate the plastic deformation, further distorting the lattice, which increases the dislocations density in the matrix. After rolling, deformation twins appear in the matrix, and dislocations nearly vanish. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the migration of the twin boundary during twin formation captures and annihilates dislocations. For example, research by Kou et al. found that in pure Cu with low stacking fault energy, fixed steps on twin boundaries can absorb dislocations through the climb of Frank partial dislocations, leading to a reduction in dislocation density23,24. This effect may be more pronounced in Cu-4.2Sn alloys because the addition of phosphorus further reduces the stacking fault energy (approximately 20–40 mJ m−2, significantly lower than that of pure Cu (70–100 mJ m−2))25. Low stacking fault energy promotes twinning-dominated deformation, inhibiting dislocation slip while enhancing the dislocation-capturing ability of twin boundaries.

Figure 4 presents the EBSD analysis results of the Cu-4.2Sn alloy. The images indicate that the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy exhibits a random texture, with a maximum texture pole density of 3.58. The rolled alloy shows enhanced texture effects, particularly for the (110) and (111) planes, with a maximum texture pole density of 10.33. Figure 4c, h show the Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) images of the Cu-4.2Sn alloy. Before rolling, the KAM image of the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy is predominantly blue, with only scattered green/yellow areas at the grain boundaries. This indicates that before rolling, the grain orientation within the tin bronze is consistent (low strain), while the atomic arrangement at grain boundaries is irregular, resulting in inherent lattice strain. This causes the crystal orientation difference at grain boundaries to be relatively larger than within the grains, reflecting inherent defects at the grain boundaries. After rolling, due to the low dislocation energy, a large number of twins formed in the Cu-4.2Sn matrix (Fig. 3). The formation of twins is accompanied by sudden changes in local crystal orientation, resulting in a significant increase in green and yellow regions (representing high orientation differences) in the KAM image. Twinning increases the deformation energy within the material through grain segmentation and orientation differences induced by twin boundaries26,27, thereby promoting work hardening in the alloy. Figure 4d, i display the distribution of grain boundary misorientation angles for both alloys, with high-angle grain boundaries ( > 15°, red lines) dominating. As shown in Fig. 4e, the grain size of the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy ranges from 5 μm to 149 μm, with an average grain size of 47.6 μm. The rolled alloy exhibits smaller and more uniform grain sizes, concentrated between 10 μm and 25 μm, with an average grain size of 15.2 μm.

Mechanical property

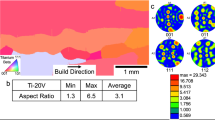

Figure5indicates the mechanical property test results for the samples. In Fig.2a, the variation in microhardness is represented by color intensity. The wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy is primarily depicted in blue, with hardness values ranging from 95 HV to 115 HV. The rolled alloys, indicated in yellow and red, are much harder than the wire-arc DED alloys, with hardness values ranging from 175 HV to 205 HV. Figure 5b shows the stress-strain curves of the alloys. For clarity and comparison, Table 1 lists the 0.2% yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation (EL). The results demonstrate that rolling significantly improves the alloy’s strength, with yield strength and tensile strength increasing by 51% and 30%, respectively. Figure 5 reveals that rolling reduces the grain size of Cu-4.2Sn, and the formation of fine grains contributes to Hall-Petch strengthening28,29:

where d is the grain size, σ is the yield stress, σ0 is the corresponding stress for a single crystal or large-grained material, and KHP is a material constant that can be theoretically predicted. The grain size d is inversely proportional to the yield stress, meaning smaller d results in higher strength. The formation of deformation twins in the rolled alloy matrix (Fig. 3g) impedes dislocation motion, refines subgrains, and enhances interfacial strengthening, while rolling results in work-hardening of the alloys, which results in a significant increase in the mechanical properties. Furthermore, Fig. 3 shows that the reduction in the size of the second phase in the alloy after rolling can generate a dispersion strengthening mechanism, which hinders dislocation movement during tensile deformation and significantly increases deformation resistance. Additionally, after rolling, when grains form preferred orientations, the angle between the slip planes and slip directions and the applied external force increases. According to Schmid’s law30,31, higher stress is required to activate slip, thereby significantly enhancing the alloy’s strength.

Figure6shows the fracture surface morphology of the alloy before and after rolling. For the wire-arc DED alloy, numerous deep ductile dimples can be observed on the fracture surface (Fig.6a), which correspond to the plastic strain of the alloy during the tensile test32, exhibiting typical high elongation ductile fracture characteristics. In contrast, the tensile fracture surface of the rolled alloy exhibits cleavage planes (Fig. 6b), which are typical of quasi-cleavage fracture, indicating poor plasticity of the alloy. This is consistent with the tensile test results (Table 4). Since the fracture of the copper layer during tensile testing indicates that the alloy has failed, the steel substrate is not analyzed further.

Tribological properties

Figure 7 displays the COF versus distance curves for the Cu-4.2Sn alloys. During the initial stage, the friction pair begins to contact the alloy surface and gradually presses into it. Due to the inherent roughness of the alloy surface, the friction pair must withstand a certain amount of compressive stress, accompanied by the friction process, to gradually penetrate the surface layer, with the friction coefficient increasing gradually during this process. During the wear stage, after penetrating the wear surface layer, the friction coefficient reaches its peak within a short period of time and then rapidly decreases; subsequently, the friction coefficient gradually stabilizes. Under dry friction conditions, abrasive particles generated between the grinding surfaces are dispersed between the two surfaces, leading to fluctuations in the friction coefficient. During wet friction, simulated seawater has some lubricating effect, so the friction coefficient of the alloy is more stable throughout the process and is less than that of dry friction. By comparison, it is found that the COF values of wire-arc DED alloy (0.86, 0.75) are higher than those of the rolled alloy (0.59, 0.54) throughout the friction process. To effectively evaluate the wear resistance of the two samples, the ratio of hardness to Young’s modulus (H/E) and yield pressure (H3/E2) were introduced33. The H/E value indicates the alloy’s ability to resist elastic strain failure, while the H3/E2 value indicates resistance to plastic deformation34. The higher the H/E and H3/E2 values, the better the wear resistance. To determine the hardness Hd and E of the two alloys, the experimental results were analyzed using Eqs. (2) to (5)35,36,37, with the experimental data listed in Table 2. The results indicate that the elastic modulus changes very little before and after rolling. The elastic modulus of the alloy is approximately 120 GPa. This is because the elastic modulus is determined by the interatomic bonding force, while rolling, as a macroscopic plastic processing technique, primarily alters the microstructure and mechanical strength of the material rather than the atomic-scale crystal properties38. The H/E and H3/E2 values of the rolled alloy are significantly higher, further confirming its superior wear resistance compared to the unrolled state.

where Fmax is the maximum indentation load; Ac is the indentation area; hc is the indentation depth under maximum load; p(h) is the corresponding load; the value of the correction exponent ε is 0.72 (Berkovich indenter); S is the unloading curve slope; Er is the Young’s modulus of the material; β is the asymmetric correction constant of the indenter, where β = 1.034 for the Berkovich indenter; Ei and vi are the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the indenter material, respectively; the Berkovich indenter is composed of diamond; Ei = 1141 GPa; vi = 0.07.

Figure 8 shows the worn surface morphologies of the samples in the dry friction condition and in simulated seawater. In Fig. 8a, the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy matrix undergoes deformation during repeated friction and wear, with noticeable flaking marks, irregular pits, torn edges, and wrinkled structures caused by plastic deformation. During friction, the temperature rises, causing the Cu alloy material to adhere to the counterface, forming metallic adhesion and leading to adhesive wear. Due to the low hardness of the matrix, material spalls from the surface under frictional wear loads, initiating fatigue cracks. These cracks propagate continuously, eventually leading to the spalling of the matrix material; thus, the dominant wear mechanisms of the matrix are fatigue wear and adhesive wear. This is similar to the findings of Kurtuluş et al. 39, who observed cracks forming in the coating when studying the wear process of Al2O3 coatings, indicating that the main wear mechanism of Al2O3 coatings is fatigue-induced. At this point, the wear track surface clearly exhibits numerous unspalled layers and deep spalling pits formed after layer detachment (Fig. 8b). Micro-area composition analysis of the wear track reveals the presence of O elements at different positions, indicating that frictional heat generated during the relative sliding of the friction pair causes oxidation of the alloy surface. This phenomenon is also clearly demonstrated in the research conducted by Boztepe et al. 40. In friction and wear experiments conducted on heat-treated D3 cold-work steel samples, the presence of the oxide layer confirmed by EDS analysis directly revealed the significant frictional heat effect generated during sliding, which also caused oxidation wear in the alloy.

In simulated seawater, although the surface of the alloy also exists in the exfoliation layer peeling off the leftover pits, but the depth of the abrasion marks is much smaller than the dry friction condition samples. In addition, in simulated seawater media, the surface of Cu alloys is susceptible to localized corrosion (e.g., pitting, intergranular corrosion) and the formation of corrosion pits or loose films of corrosion products (e.g., CuO, Cu2O, Cu (OH)2)41,42. During friction, the corrosion products are dislodged due to mechanical loading and form fine particles, which become new abrasive grains, thus creating a furrow morphology on the alloy surface during friction (Fig. 8e).

Figure 9 shows the worn surface morphologies of the rolled alloys. The occurrence of adhesive wear depends on the localized softening and adhesion of the contact surfaces. However, the increased hardness of the alloy after rolling makes it difficult for surface protrusions to undergo plastic deformation and interlock with each other. During sliding, the hard protrusions of Si3N4 grinding balls, which have higher hardness than the copper alloy, embed into and plow the softer substrate surface. During the friction process, the Hall-Petch strengthening effect induced by fine grains enhances the alloy’s resistance to plowing, while twin boundaries act as barriers to dislocation movement, reducing surface plastic deformation during wear deformation and inhibiting the formation of adhesion points. Additionally, the reduced plasticity of the alloy makes it difficult for the material to achieve plastic deformation buffering through lateral flow during grinding and cutting, thereby reducing the probability of surface adhesion points and tearing phenomena, and promoting a shift in the wear mechanism toward furrow wear dominance. In a simulated seawater environment, the friction process continuously peels off loose corrosion products, with the remaining product film acting as a hard layer, gradually transforming from a protective layer on the alloy surface into an abrasive source. Although friction heat is partially offset by seawater cooling, it still accelerates corrosion reactions and product formation, promoting the continuous conversion of corrosion products into abrasive sources, ultimately forming furrow wear morphology on the alloy surface.

Comparing the depth and volume of the wear morphology (Table 3), the friction coefficient (Fig. 7) and H/E ratio (Table 2), it is evident that the friction resistance of the alloy has been enhanced after rolling. The primary reason lies in the formation of high-energy twin boundaries in the alloy matrix during the rolling process, which significantly enhances the material’s ability to resist plastic deformation, crack propagation, and adhesion, thereby effectively suppressing wear mechanisms during friction. Additionally, the grain size and precipitate phase size of the rolled tin bronze have both decreased (Figs. 2 and 3). Through grain refinement strengthening, dispersion strengthening, and the work hardening effect induced by cold rolling, the alloy’s hardness and deformation resistance have been enhanced, thereby suppressing abrasive cutting and material peeling; simultaneously, the enhanced texture effect increases the activation stress of slip systems, reduces the surface deformation layer, and lowers grain boundary stress concentration, ultimately significantly improving the alloy’s wear resistance.

Synergistic effect of corrosion-friction

Figure 10 shows the potentiodynamic polarization curves for fresh samples and during friction in simulated seawater. It can be seen that in the static environment, the alloy has a passivation zone in the anodic section (wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn: 0.1–0.8 V, rolled: 0.01–0.8 V), while the potentiodynamic polarization curve of the alloy does not exhibit a clear passivation zone during dynamic friction. Since the cathodic polarization region of the potentiodynamic polarization curve is mainly affected by diffusion limitation and has the least effect on the Tafel behavior of the oxygen reduction reaction43, the anodic polarization region is selected for fitting. Table 4 shows the fitting and calculation results of corrosion current density (icorr) for wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn and rolled alloys. For fresh samples, the corrosion potentials of the two samples are similar, about -0.3 V, but the icorr of the rolled alloy (1.15 × 10−5 A cm−2) is larger than that of the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy (8.11 × 10−6 A cm−2). Due to the high distortion energy at grain boundaries and the distribution of a large number of irregularly arranged atoms, as well as the abundance of impurity elements and defects, the electrochemical activity at grain boundaries is higher than that inside the grains44,45,46. Therefore, compared with coarse grain alloys, after rolling, fine grain alloys have more initial active atoms, which is conducive to the free movement of corrosion ions and reduces the passivation ability of the alloy. In addition, the twin grain boundary crystal defects and high energy state in the rolled alloy make it a preferential corrosion site, so the corrosion resistance of the rolled alloy is lower than that of wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn. During the friction process, the corrosion product film on the alloy surface was destroyed continuously, the polarization curves of the two alloys shifted to the right obviously, and the corrosion potentials of the two alloys decreased to -0.48 V and -0.5 V, respectively. At this time, the icorr of wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy and rolled alloy were 1.07 × 10−4 A cm−2 and 5.02 × 10−5 A cm−2, respectively, which were higher than that of static state, and the corrosion resistance of the alloys decreased.

Figure 11 shows the mass loss of the alloy in dry friction condition, and simulated seawater and deionized water. It can be seen from the fig. that the mass loss of the alloy after rolling is less than that of Cu-4.2Sn alloy in dry and wet friction environments. This further confirms the improvement of friction and wear resistance of the alloy after rolling. The mass loss (Mt) of the alloy in simulated seawater can be expressed by Eq. 647:

where Mf is pure wear weight loss, Mc is pure corrosion weight loss, ΔMs is weight loss due to corrosion and wear interaction (ΔMs). ΔMs is the sum of corrosion weight loss due to wear Mcf and wear weight loss due to corrosion Mfc. Mcf can be calculated by Faraday’s law48:

where i is the corrosion current, t is the experimental duration (S), W is the relative atomic mass, n is the change in valence of elements during corrosion, F is Faraday’s constant (96,487 C49), ρ is the density of the alloy. W and n are 64 g·mol−1 and 2, respectively. After calculating the values of Mc and Mfc, the mass loss increment Mcf caused by corrosion is obtained by subtracting the remaining terms from the total mass loss Mt. Table 5 and Fig. 12 show the mass loss components caused by different factors and the corresponding proportions for friction and wear for 30 minutes respectively. The mass loss increment caused by the interaction between corrosion and friction and wear of the two materials accounts for 13%, and the increment of friction promoting corrosion is larger than that of corrosion promoting.

First of all, Cu alloy corrosion in marine environment will form Cu2O and Cu2Cl(OH)3 primarily composed of corrosion product film (as shown in the reaction formula41). Although the surface film can provide limited protection, the film hardness is low, toughness is poor, and the bonding force with the substrate is weak. During friction and wear, the surface film is highly prone to mechanical peeling or brittle fracture, resulting in the direct exposure of the base metal to the corrosive medium. The surface of nascent Cu exhibits higher electrochemical activity (Cu2⁺/Cu standard electrode potential 0.34 V), in the medium containing dissolved oxygen and chloride ions, it will cause severe anodic dissolution, and the corrosion current density can be increased by 1–2 orders of magnitude (Table 4). It is worth noting that the corrosion products of Cu mostly present loose and porous structure, which makes it difficult to realize the self-healing function of surface film, thus forming a self-accelerating failure mechanism of “mechanical wear-film destruction-accelerated corrosion-product looseness-secondary wear”.

Secondly, friction-induced surface plastic deformation (such as ploughing groove formation and micro-asperity fracture) can induce significant microstructural damage, such as high-density dislocations and grain boundary exposure. This microheterogeneity leads to differences in local electrochemical activity, forming a microbattery effect between local anodes (freshly deformed areas) and cathodes (undeformed or oxide film residual areas). For example, Cu atoms in deformed areas are more active and become anodes for preferential dissolution, while undamaged oxide film areas act as cathodes for O2 reduction reactions (O2 + 2H2O + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻ 50), forming localized corrosion with a corrosion rate much higher than uniform corrosion. If wear debris generated by wear remains on the contact surface, a crevice corrosion environment will be formed, which will further aggravate localized corrosion. Therefore, friction and wear not only eliminate the kinetic barrier of product film but also promote localized corrosion of alloy, which greatly promotes the mass loss increment due to corrosion.

Thirdly, corrosion has a limited promotion effect on the friction of Cu alloy. The corrosion products of Cu are less ductile, have a weak cutting ability when used as abrasive particles, and have a limited role in promoting wear. Although the surface layer softening caused by corrosion51 may increase the material removal rate, its thickness is usually only a few to dozens of micrometers, which is far less than the material peeling depth in a single contact during the friction process (up to hundreds of micrometers), and thus contributes little to the overall wear amount. In addition, it takes time (from minutes to hours)52,53,54 for corrosion to cause visible damage (such as pitting corrosion pits and surface roughening), while the mechanical peeling in wear is an instantaneous process55,56. On the same time scale, wear has directly removed a large amount of material and damaged the protective film through mechanical action, while corrosion only causes slight surface roughness or local embrittlement, and has not significantly changed the wear mechanism (such as from adhesive wear to abrasive wear). The wear resistance of Cu alloys mainly depends on the matrix hardness and lubrication conditions. The degradation of surface properties caused by corrosion has a far less significant impact on the wear rate than the direct effect of mechanical peeling. Therefore, the mass-loss increment of friction promoted by corrosion is less than that of corrosion promoted by friction.

In this study, a comparative analysis was conducted on the microstructures, mechanical properties, and tribological behavior of the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy before and after cold rolling. Additionally, a decoupling analysis was performed on the corrosion and friction interactions of the alloy, leading to the following conclusions:

-

(1)

The results indicate that the Al-coated alloy resolved the issue of penetration cracks on the steel side at the tin bronze/steel interface.

-

(2)

Compared with the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy, the grain size of the rolled alloy decreased by 68%, and a large number of twins are generated in the matrix. The yield strength and hardness of the alloy increase by 51% and 78%, respectively.

-

(3)

In simulated seawater, both the COF and mass losses are lower than those of the samples in dry friction condition. After rolling, the friction damage of Cu-4.2Sn alloy changes from adhesive wear to furrow wear. Compared with the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy, the rolled alloy exhibits better wear resistance. The mass losses of the samples in the dry friction condition and simulated seawater decrease by 23% and 25%, and the COF decreased by 31% and 28%, respectively.

-

(4)

The icorr of the rolled alloys is slightly higher than the wire-arc DED Cu-4.2Sn alloy for freshly immersed samples, but it showed stronger synergistic performance in resisting corrosion and friction.

-

(5)

The decoupling analysis indicates that in the interaction, the loss caused by the interaction between friction and corrosion accounted for 13%, among which the effect of friction promoting corrosion is dominant (accounting for approximately 11%).

Methods

Materials and methods

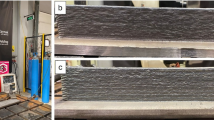

For sample preparation, S212 wire with a 1.6 mm diameter was employed, while the substrate used was a 2 µm Al-plated mild steel with dimensions of 200 mm × 200 mm × 2 mm. Their compositions are detailed in Table 6. The CMT wire-arc deposition equipment used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 13. The wire-arc deposition system consisted of a Yaskawa MA1400 robot, a DX200 control cabinet, and an RD350 digital inverter power supply. Wire-arc DED uses a molten droplet transition to complete the sample preparation by adjusting the process parameters through the control panel. Argon is used as the shielding gas during deposition. The deposition parameters are shown in Table 7. Subsequently, the prepared plates were cold-rolled with a 1% reduction per pass until a total deformation of 20% was achieved, resulting in rolled bimetallic composites.

Microstructure characterization

The fabricated samples underwent wire cutting for sectioning, followed by progressive abrasion wiath SiC paper up to a 5000-grit surface finish. Subsequently, they were finely polished using 1.0 μm diamond suspension. Etching was performed with (5 g FeCl3 + 2 mL HCl + 95 mL C2H5OH) solution. Microstructural analysis was conducted using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Mon FEI, USA) integrated with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Grain size characterization of the alloy was achieved via electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD; INCA Crystal EBSD), with results analyzed using AZtecCrystal software. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM; TalosF 200X, Thermo Fisher, USA) operated at 200 kV was employed for detailed sample observation.

Mechanical and friction performance testing

Mechanical property tests were performed at a constant strain rate of 1.5 mm·s−¹ at 25 °C using a CMT 5105 testing machine. A microhardness tester (FM-700) was used to evaluate the hardness of the samples under a 300 gf load. Hardness measurements were taken at 100 μm intervals in the x and y directions, and a 5×5 array was used to map the hardness values. In this experiment, a nanoindenter equipped with a diamond Berkovic indenter tip was used to test the micro-mechanical properties of arc-deposited alloys and their rolled states. The test parameters were a maximum load of 6 N, a loading/unloading rate of 200 mN·s−1, and a load holding time of 5 s.

Reciprocating friction and wear tests were conducted using an MSR-2T friction tester. To avoid galvanic corrosion between the Cu-4.2Sn alloy and the grinding ball, a non-conductive silicon nitride ceramic ball was selected. The tests were performed under a 15 N load at a speed of 3 m·min−1, with a 3 mm reciprocating stroke for 1800 s. The corrosive friction medium was a simulated seawater solution, the composition of which is shown in Table 8. The samples were weighed before and after the experiment using an electronic balance with a sensitivity of 0.01 mg. Finally, 3D morphology (OLS4000 laser confocal microscope) and SEM morphology were observed on the test specimens.

Simulated seawater was used for the electrochemical test solutions and the temperature was maintained at 25 °C during the electrochemical tests. Tests were performed on fresh samples and samples during friction with kinetic potential polarization in the ranges of -1.2 V to 1.3 V and -1 V to 0.4 V. The equipment and parameters used for the tests were similar to those used in previous study19 and are not described here.

First-principles calculations

This study employs the vienna ab-initio simulation package (VSPA)57 software to conduct first-principles calculations, analyzing the influence of different atoms (Cu, Sn, Al) on Fe grain boundaries in tin bronze. The VASP software can precisely determine the physical structure, electronic structure, and system energy of grain boundaries through a series of convergent calculations. Additionally, first-principles tensile test calculations were performed to investigate the effects of different atoms on the strength of Fe grain boundaries, thereby analyzing the roles of various elements in the formation and suppression of penetration cracks. The visualization for electronic and structural analysis (VESTA) software is used to visualize the results of the VASP first-principles calculations. By reading the VASP output file CONTCAR using VESTA, crystal boundary models and crystal boundary models after different atomic substitutions were plotted, enabling the physical structure of the crystal boundaries to be intuitively visualized. Additionally, by reading the CHGCAR file using VESTA, charge density distribution maps can be plotted.

According to the Rice-Wang grain boundary embrittlement model58, the effect of other atoms on the strength of Fe grain boundaries can be measured by the strengthening energy (Estr), which is calculated using the following Eq. (8):

\({E}_{{se}p}^{{Fe}}\) is the separation energy of pure Fe grain boundaries, \({E}_{{se}p}^{{Fe},\,X}\) is the separation energy of Fe grain boundaries containing other atoms.

To further investigate the mechanism by which doped atoms affect grain boundary strength, the strengthening energy can be decomposed into mechanical contributions Emech and chemical contributions Echem59,60. The specific values of the mechanical and chemical contributions can be calculated by considering a series of systems. Taking the Cu/Fe system as an example, system A represents an ideal Fe grain boundary model and the two fracture surface models obtained after the separation of the Fe grain boundary. System B is a pure Fe grain boundary model containing one Fe vacancy and its fracture surface model, which is obtained by removing one Fe atom from system A. System C is a crystal boundary model with Cu atoms doped into pure Fe crystal boundaries and its fracture surface model, where the Cu atoms occupy the positions of the Fe vacancies in system B. System D is the crystal boundary model and fracture surface model obtained by removing the doped Cu atoms from system C. The mechanical contribution is caused by local structural changes and can be considered as the difference between the separation energies of systems B and D:

Chemical contributions arise from changes in interactions caused by the chemical properties of different atoms. The difference in separation energy between pure Fe grain boundary system A and Fe-vacant system B is due to the removal of Fe atoms. The difference in separation energy between Cu-containing grain boundary system C and Cu-vacant system D is due to the removal of Cu atoms. Therefore, the formula for calculating chemical contributions is as follows:

Reinforced energy can be calculated using Eq. (11):

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hu, D. C., Chen, M. H., Wang, L. & Cheng, H. Dynamic tensile behaviour and deformational mechanism of C5191 phosphor bronze under high strain rates deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 649, 68–73 (2016).

Liu, Y., Liu, X. H., Fu, H. D., Lou, M. X. & Xie, J. X. Effects of process parameters on surface quality, composition segregation, microstructure and properties of QSn6.5-0.1 alloy slabs fabricated by HCCM horizontal continuous casting. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 24, 273–281 (2017).

Park, J. H., Kim, S. Y., Lee, H. S. & Wi, K. Influence of different metal types on the bonding strength of concrete using the arc thermal metal spraying method, Materials 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16072651 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Friction and wear properties of wide-velocity range high-energy plasma sprayed CuSn-NiCr solid self-lubricating coatings under heavy load. Wear 550, 205417 (2024).

Gan, R. et al. Preparation and properties of Cu/Cu-Sn alloy cladding layers on titanium alloy by laser cladding. J. Alloy. Compd. 1020, 179547 (2025).

Ozdemir, I., Bulbul, B., Grund, T. & Lampke, T. Wear and corrosion behavior of cold-sprayed Cu-10Sn coatings, Crystals 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst13030523 (2023).

Wei, J. et al. Cold spray deposition and microstructure characterization of CuNi, CuSn, and CuNiSiCr coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 480 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2024.130621 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. A novel cold wire gas metal arc (CW-GMA) process for high productivity additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 73 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103681 (2023).

Zhang, H., Hu, S., Wang, Z. & Liang, Y. The effect of welding speed on microstructures of cold metal transfer deposited AZ31 magnesium alloy clad. Mater. Des. 86, 894–901 (2015).

Wei, M. et al. Technology, Microstructure and bonding strength of tin-based Babbitt alloy on ASTM 1045 steel by MIG arc brazing. 32, 1–12 (2018).

Evangeline, A. & Paulraj, S.J.M.R.E. Cold metal arc transfer (CMT) metal deposition of inconel 625 superalloy on 316L austenitic stainless steel: microstructural evaluation, corrosion and wear resistance properties. 6, 066516 (2019).

Wei, M., Sun, K., Zhang, X., Zhang, C. & Xue, F. Microstructure and bonding strength of tin-based Babbitt alloy on ASTM 1045 steel by MIG arc brazing. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 32, 1–12 (2018).

Cai, X. et al. From cast to wire-arc DED: an investigation on NAB alloy MIC resistance. Corros. Sci. 251 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2025.112910 (2025).

Cai, X. et al. Comparative analysis of cavitation erosion behavior in wire-arc directed energy deposition and cast nickel-aluminum bronze alloys. Ultrason. Sonochem. 113 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2025.107235 (2025).

Mosleh-Shirazi, S., Akhlaghi, F. & Li, D. Y. Effect of graphite content on the wear behavior of Al/2SiC/Gr hybrid nano-composites respectively in the ambient environment and an acidic solution. Tribol. Int. 103, 620–628 (2016).

Ren, S., Meng, J., Wang, J., Lu, J. & Yang, S. Tribo-corrosion behaviors of Ti3SiC2/Si3N4 tribo-pair in hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide solutions. Wear 274, 8–14 (2012).

Ebrahimi, M., Attarilar, S., Shaeri, M. H., Gode, C. & Djavanroodi, F. M. Engineering, An investigation into the effect of alloying elements on corrosion behavior of severely deformed Cu-Sn alloys by equal channel angular pressing. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 19, 842–850 (2019).

Moharami, A. Improving the dry sliding-wear resistance of as-cast Cu-10Sn-1P alloy through accumulative back extrusion (ABE) process. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 10091–10096 (2020).

J. Hui, W. Liu, B. Wang, Quasi-gradient variation of microstructures and properties of Cu–Sn alloy along the thickness direction under cold spinning. J. Alloy. Compd. 831 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154701 (2020).

Pantawane, M. V., Ho, Y. H., Joshi, S. S. & Dahotre, N. B. Computational assessment of thermokinetics and associated microstructural evolution in laser powder bed fusion manufacturing of Ti6Al4V Alloy. Sci. Rep. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63281-4 (2020).

Orzolek, S. M., Semple, J. K. & Fisher, C. R. Influence of processing on the microstructure of nickel aluminum bronze (NAB). Addit. Manuf. 56 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102859 (2022).

Xing, Z. B., Nie, Z. R., Zou, J. X. & Gao, X. D. Effects of cooling rate on solidification and microstructure of Al-4.5Mg-0.7Mn-0.4Er alloy. Spec. Cast. nonferrous Alloy. 27, 3 (2007).

Kou, Z. et al. Observing dislocations transported by twin boundaries in Al thin film: unusual pathways for dislocation-twin boundary interactions. Nano Lett. 22, 6229–6234 (2022).

Kou, Z. et al. Revealing the atomic-scale evolution of sessile disconnections on twin boundaries during deformation. Scr. Mater. 221 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2022.114956 (2022).

Dey, S. N. P. Chatterjee, S. P. S. Gupta, Deformation stacking fault probability and dislocation microstructure of cold worked Cu-Sn-5Zn alloys by x-ray diffraction line profile analysis. J. Appl. Phys. 100 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2356906 (2006).

Rizi, M. S., Minouei, H., Lee, B. J., Toroghinejad, M. R. & Hong, S. I. Effects of carbon and molybdenum on the nanostructural evolution and strength/ductility trade-off in Fe40Mn40Co10Cr10 high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 911, 165108 (2022).

Rizi, M. S. et al. Enhancing mechanical properties in Ti-containing FeMn40Co10Cr10C0.5 high-entropy alloy through Chi (χ) phase dissolution and precipitation hardening. Mater. Lett. 377, 137516 (2024).

Cai, X. et al. Advanced mechanical properties of nickel-aluminum bronze/steel composite structure prepared by wire-arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 221, 14 (2022).

Li, Y., Bushby, A. J. & Dunstan, D. J. The hall-petch effect as a manifestation of the general size effect. Proc. R. Soc. A-Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 472 https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2015.0890 (2016).

Zhou, L. et al. Quasi-in situ electron backscatter diffraction analysis of twinning-detwinning behavior in AZ31 magnesium-alloy rolled plates subjected to compression loading in different directions. J. Magnes. Alloy. 13, 2358–2373 (2025).

Pouraliakbar, H. et al. Texture and grain refinement for enhanced strength and ductility in friction stir welding of cold-rolled thin-strip rapidly solidified AA5182 Al-Mg alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 36, 10143–10156 (2025).

Cai, X. et al. Effect of quasicrystal I-phase on microstructure and mechanical properties of hot-rolled diphasic Mg-8 wt.% Li alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 31, 3054–3064 (2022).

Lai, X. et al. Effect of annealing on microstructure and properties of AlCoCuFeTi high-entropy alloy fabricated by arc melting. Intermetallics 170 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intermet.2024.108327 (2024).

Okoro, A. M. et al. Nanoindentation studies of the mechanical behaviours of spark plasma sintered multiwall carbon nanotubes reinforced Ti6Al4V nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 765, 138320 (2019).

Cai, X., Qiao, Y. X., Wang, B. J., Zhou, H. L. & Wang, Y. X. Effect of cold rolling on microstructural and mechanical properties of Mg-7Li alloy. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 34, 2040035 (2020).

Tian, S. et al. Intermetallics-induced directional growth of Sn whiskers in Sn-3.5Ag coating on Al substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 539, 148135 (2021).

Tian, S. et al. Tin whiskers prefer to grow from the 001 grains in a tin coating on aluminum substrate. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 80, 191–202 (2021).

Kaneko, H., Eguchi, T. & Inoue, H. Recrystallization Texture and Young’s Modulus in Cu-3.8%Ni-0.9%Si Alloy Sheets. J. Jpn. I. Met. Mater. 77, 353–360 (2013).

Kurtulus, V., Gorgulu, B., Eraslan, F. S. & Gecu, R. Improving wear and corrosion resistance of Ti-alloyed nodular cast irons by Al2O3 and SiC-reinforced Al2O3 coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 498, 131809 (2025).

Boztepe, A. & Gecu, R. Influence of cryogenic treatment and tempering temperature on microstructural evolution and dry sliding wear behavior of AISI D3 cold-work tool steel. J. Tribol. 147, 064201 (2025).

Cai, X. et al. Experimental investigations on corrosion behavior and antibacterial property of nickel-aluminum bronze fabricated through wire-arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). Corros. Sci. 214 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111040 (2023).

Cai, X. et al. Investigation of mechanical and corrosion behavior of multi-pass nickel-aluminum bronze fabricated through wire-arc directed energy deposition, Addit. Manuf. 80 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2024.103967 (2024).

Cai, X. et al. Experimental investigation on wear resistance and corrosion behavior of nickel-aluminum bronze alloy fabricated by wire-arc additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 5801–5815 (2023).

Palumbo, G. et al. Effect of grain size on the corrosion behavior of Fe-3 wt%Si-1 wt% Al electrical steels in pure water saturated with CO2. Materials 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14175084 (2021).

Yamashita, M., Mimaki, T., Hashimoto, S. & Miura, S. Intergranular corrosion of copper and α-Cu-Al alloy bicrystals. Philos. Mag. A 63, 695–705 (1991).

Miyamoto, H., Yoshimura, K., Mimaki, T. & Yamashita, M. Behavior of intergranular corrosion of〈0 1 1〉 tilt grain boundaries of pure copper bicrystals. Corros. Sci. 44, 1835–1846 (2002).

Runa, M. J., Mathew, M. T. & Rocha, L. A. Tribocorrosion response of the Ti6Al4V alloys commonly used in femoral stems. Tribol. Int. 68, 85–93 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. Effect of surface oxidation on wear and tribocorrosion behavior of forged and selective laser melting-based TC4 alloys. Tribol. Int. 174 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2022.107780 (2022).

Alghamdi, S. A., Ahmad, S. & Lawan, A. Optimization of concrete mixture design and cover thickness for reinforced concrete members under chloride exposure. Acids. Mater. J. 113, 589–598 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. The role of nickel in mechanical performance and corrosion behaviour of nickel-aluminium bronze in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 139, 333–345 (2018).

Xin, J. M., Fan, L., Liu, Y. P. & Ma, L. Research progress on the corrosion mechanism of copper and Its alloys in marine environment. Equip. Environ. Eng. 21, 127–136 (2024).

Chang, T. et al. The role of Sn on the long-term atmospheric corrosion of binary Cu-Sn bronze alloys in architecture. Corros. Sci. 149, 54–67 (2019).

Liang, Z., Jiang, K. & Zhang, T. A. Corrosion behaviour of lead bronze from the Western Zhou Dynasty in an archaeological-soil medium. Corros. Sci. 191 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109721 (2021).

Xie, W., Qian, L. & Yong, L. Corrosion Behavior of New Cu-Sn-Fe-Ni Alloy in 3.5wt% NaCl Solution. Rare Met. Mat. Eng. 52, 3893–3899 (2023).

Hou, Q. Y. et al. Liquid phase separation microstructure and properties of mixed Cu-Sn and Co-base alloys without or with molybdenum addition processed by plasma transferred arc hardfacing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 262, 87–96 (2015).

Kostornov, A. G. et al. Service properties of Cu–Sn–CuWO4 –MoS2 composite and micromechanical characteristics of its friction surface. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 49, 647–653 (2011).

Kresse, G. Matter, Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B Condens Matter 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Rice, J. R. & Wang, J. S. Embrittlement of interfaces by solute segregation. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 107, 23–40 (1989).

Wu, X. B. et al. First-principles determination of grain boundary strengthening in tungsten: Dependence on grain boundary structure and metallic radius of solute. Acta Mater. 120, 315–326 (2016).

Razumovskiy, V. I., Divinski, S. V. & Romaner, L. Solute segregation in Cu: DFT vs. Experiment 147, 122–132 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z.: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft; L.W. : Investigation; D.M.: Investigation, Methodology; X.C.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—review & editing; M.M.Y.: Investigation; Y.X.Q.: Writing—review & editing; J.Z.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, W., Wang, L., Miao, D. et al. Enhancing mechanical strength and tribological performance in tin bronze alloys via rolling treatment. npj Mater Degrad 9, 107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00655-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00655-x