Abstract

Subradiance shows promising applications in quantum information, yet its realization remains more challenging than superradiance due to the need to suppress various decay channels. This study introduces a state space within a single-excitation basis with perfect subradiance and genuine multipartite quantum entanglement resources for the all-to-all case. Utilizing the quantum jump operator method, we also provide an analytical derivation of the system’s steady final state for any single-excitation initial state. Additionally, we determine the approximate final state in the quasi-all-to-all coupling scenario. As an illustrative example, we evaluate the coupling and dynamical properties of emitters in a photonic crystal slab possessing an ultra-high quality bound state in the continuum, thereby validating the efficacy of our theoretical approach. This theoretical framework facilitates the analytical prediction of dynamics for long-lived multipartite entanglement while elucidating a pathway toward realizing autonomous subradiance in atomic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multipartite quantum entanglement is an important quantum resource for quantum information processing in many-body systems1,2. In a three-qubit pure-state system, there are two inequivalent types of genuine tripartite entanglement: the GHZ class and the W class3. The three-qubit GHZ state \((\left\vert 000\right\rangle +\left\vert 111\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) is considered the maximally entangled state of three qubits, as all the single-qubit reduced states of the GHZ state are entirely mixed. However, under particle losses, the entanglement properties of the state GHZ are extremely fragile. In contrast, the entanglement of W state, \((\left\vert 001\right\rangle +\left\vert 010\right\rangle +\left\vert 100\right\rangle )\sqrt{3}\), is maximally robust under loss of any one of the three qubits. In addition, multipartite W-class states play important roles in quantum memory and quantum communication3,4, quantum measurement5, and quantum error correction6,7,8,9. In the framework of single-excitation, the collective states are usually entangled as a W-class, in which a single excitation is dispersed among multiple atoms.

In a collection of atoms, the collective emission rate can exceed γ0 (the vacuum emission rate of single excited atom10), resulting in a superradiant state11,12,13, or be less than γ0, leading to a subradiant state11,14,15,16. While superradiance and subradiance have attracted significant research interest and enabled various applications in recent years17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, observing subradiance is more challenging than superradiance due to the complex decay channels in most atomic systems. Subradiance has nonetheless been experimentally demonstrated in ultracold atomic28,29,30,31, molecular32,33, and superconducting34 systems. For a perfect subradiant state, the initially excited quantum system remains in its initial state indefinitely. These decoherence-free dark states are essential for quantum information processing. The simplest perfect dark state is an antisymmetric two-atom state\((\left\vert 01\right\rangle -\left\vert 10\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), with maximum incoherent interaction, where the spontaneous emission rate approaches zero35. However, in the vacuum, the inter-atomic interaction decays exponentially with distance. While strong, long-range interactions can be achieved in plasmonic or photonic systems36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, they have strict requirements on the number and geometry of atoms, and inherent losses in these systems limit their applications in quantum information.

The study of bound states in the continuum (BIC) has emerged as a promising approach for controlling and confining optical resonant modes with remarkably high-quality factors, enabling various applications44,45,46,47. Of particular interest are nonradiating BIC modes that also exhibit an effective zero refractive index48,49,50. Such BIC-zero-index systems can provide high-quality light confinement and facilitate long-range51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, even all-to-all interactions59, owing to the infinite wavelengths inherent to these materials. These unique properties make BIC-zero-index systems a potential candidate for realizing autonomous steady-state subradiance. However, for systems with long-range dissipative interactions, the dynamical evolution of multiple particles often becomes complex, as it requires numerical integration in the exponentially growing Hilbert space, which greatly limits the understanding of phenomena such as subradiance and related research.

In this work, we introduce a theoretical framework that addresses the dynamics of single-excitation processes in complex systems and facilitates the prediction of dynamics for long-lived multipartite entanglement, circumventing the need for intricate integral computations. While steady-state subradiance has been widely studied in waveguide60,61,62 and cavity QED63,64 systems, these platforms typically require external laser pumping. Our framework enables autonomous subradiance without external driving or precise initialization, as demonstrated through the quantum jump operator method, where we analytically derive the steady-state final state for any single-excitation initial state, including the approximate solution in the quasi-all-to-all case. The steady states exhibit W-class entanglement, with a maximally entangled state provided. As a demonstration, we compute the coupling and dynamics of emitters embedded in a dielectric photonic crystal slab with a BIC, confirming the validity of our approach. This theoretical framework elucidates a pathway toward realizing autonomous steady-state subradiance and multipartite entanglement.

This paper is organized as follows: In RESULTS, we introduce the model, the quantum jump operator profiles, and the maximally entangled and steady state in the all-to-all case. Next, we work out the analytical final state of any single-excitation initial state. At the end of RESULTS, we illustrate an example of emitters embedded in a high-quality photonic crystal slab possessing the bound state in the continuum to validate the efficacy of our theoretical approach. In DISCUSSION, we have some discussions about the robustness of autonomous subradiance. At the end of the work, we present the METHODS used in the whole work.

Results

The quantum jump operator profile

Following the tracing of the environment and the application of the Born-Markov and rotating-wave approximations, the Lindblad master equation of the n-emitter system in a weakly coupled environment can be expressed as35,43,65

where the raising and lowering operators of the ith emitter are denoted by \({\hat{\sigma }}_{i}^{\dagger }\) and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{i}\), respectively. The Hamiltonian shown in Eq. (1) is

with gij being the coherent coupling between the ith and jth emitters and ω0 being the transition frequency of emitters (here we assume that the two-level emitters are identical).

When discussing collective emission dynamics, the spin operators of single emitters can be conveniently recast into the collective jump operator \(\{{\hat{{\mathcal{O}}}}_{\nu }\}\), and the Lindblad equation gives66,67

with \(\left\{{\Gamma }_{\nu }\right\}\) being the eigenvalues of the decoherence matrix Γ, which takes the form

where the matrix element γij is the dissipative coupling between the ith and jth emitters, which can be calculated using electromagnetic Green’s tensor, as shown in Eqs. (30) and (31), and correspondingly, we can find that the collective operators \({\hat{{\mathcal{O}}}}_{\nu }\) and \({\hat{{\mathcal{O}}}}_{\nu }^{\dagger }\) are

where \({\left({\alpha }_{\nu ,1},{\alpha }_{\nu ,2},\cdots ,{\alpha }_{\nu ,n}\right)}^{\top }\) is the normalized eigenvector of matrix Γ, which corresponds to the eigenvalue Γν. Consequently, we have

and the matrix elements of Γ as illustrated in Eq. (3) are

In the language of this collective operator, a generic form of a master equation can be written as

where the ν-jump Liouvillian superoperator \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{\nu }\) is

The notation \(\left(\cdot \right)\) represents a placeholder for an arbitrary operator or state on which the superoperator \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{\nu }\) acts.

The solution of master equation

It is convenient to convert the matrices, such as density matrix, ρ to flattened vector \(\tilde{\rho }\) following a column-wise ordering

This process is the flattening of a matrix. For a general matrix A, it can be flattened as

where ai is the ith column of A with i ∈ [1, n]. In this work, we call the vector \(\tilde{A}\) the flattened form of matrix A.

In this context, we can transfer the superoperators, as illustrated in Eq. (8), into the multiplication of ρ by a matrix for convenience. We denote the multiplication operations \(A\left(\cdot \right)\) and \(\left(\cdot \right)B\) as pre(A) and post(B), respectively. Here we assume the dimensions of matrix A, B and ρ are all n, and we can easily obtain that

and

where pre(A) and post(A) are \({({2}^{n})}^{2}\)-dimensional matrices and ⊤ represents the transpose of a matrix.

Therefore, the superoperator of the right-hand side of Eq. (8) can be written as a \({({2}^{n})}^{2}\times {({2}^{n})}^{2}\) matrix

and thus the Lindblad master equation can be written in flattened form

The dimension of \({\mathcal{L}}\) grows with \({({2}^{n})}^{2}\), so when n is large, the numerical procedure will be very complicated. Subsequently, we will give a significantly simplified analytical method for the all-to-all case to calculate the system’s steady state over an extended period.

Actually, the flattened density matrix \(\tilde{\rho }(t)\) is a vector, so we rewrite this vector as a traditional Dirac form \(\left\vert r(t)\right\rangle\). It is important to observe that the vector presented here is not a conventional pure state but a vector form of a flattened density matrix. The initial state is denoted as \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\). In this case, \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle ={\rm{flatten}}\{\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{0}\right\vert \}\), where \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) represents the actual initial state. After the diagonalization procedure, we can obtain the eigenvectors and the eigenvalues of matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\). Nevertheless, these eigenvectors are not orthogonal. Subsequently, we orthogonalize these eigenvectors to obtain the orthogonalized and normalized eigenvectors \(\{\vert{l}_{\beta}\rangle\}\) and their corresponding eigenvalues \(\{{\epsilon }_{\beta }\}\), namely \({\mathcal{L}}={\sum }_{\beta }{\epsilon }_{\beta }\vert {l}_{\beta }\rangle \langle {l}_{\beta }\vert\). A diagonalization procedure can be found in METHODS. Consequently, the state at time t can be readily obtained as

It is important to note that it is generally challenging to diagonalize and orthogonalize a system with a large n, as the dimension of the matrix to be diagonalized increases with \({({2}^{n})}^{2}\). However, as we will see below, it is feasible to identify an analytical solution in the all-to-all scenario.

Maximally entangled and steady state in the all-to-all case

In the all-to-all case, the elements of the decoherence matrix Γ are all 1, namely the dissipative couplings between any two emitters are identical. This mechanism mirrors the case in the Dicke model, where a subwavelength ensemble of two-level atoms interacts uniformly with a quantized radiation field. However, such all-to-all coupling in the Dicke model is typically an idealized limit, assumed when atomic spacings approach zero. In this work, we will show that this all-to-all scenario can be realized in extended space using BIC-zero-index materials, enabling autonomous subradiance through our theoretical framework. The only non-zero eigenvalue of Γ is Γ1 = n, and the corresponding eigenvector is \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}{\left(1,1,\cdots ,1\right)}^{\top }\). Therefore, the master equation depicted in Eq. (8) can be written as

with

The matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\) is deterministic for a qubit system with a deterministic Hamiltonian and dissipative couplings between any two qubits. A steady state \({\tilde{\rho }}_{{\rm{s}}}\) for such a dissipative system requires that \({\mathcal{L}}{\tilde{\rho }}_{{\rm{s}}}=0\). The primary objective of this research is to identify non-trivial steady states that will enable us to determine the quantum state of the system after an infinitely long period. Then, we will provide a comprehensive explanation of how to utilize non-trivial steady states to obtain the exact arbitrarily long-time quantum state in the all-to-all case and the approximate long-time quantum states in the nearly all-to-all cases.

We first define the single-excitation basis \(\{\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle =\left\vert 00\cdots 1\right\rangle ,\left\vert {\mathbf{2}}\right\rangle =\left\vert 00\cdots 10\right\rangle ,\cdots \,,\left\vert {\boldsymbol{n}}\right\rangle =\left\vert 10\cdots 00\right\rangle \}\). The number i in \(\left\vert {\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle\) corresponds to the ith qubit is excited and the others are in their ground states, and \(\left\vert {\mathbf{0}}\right\rangle\) is the vacuum state. The maximal multipartite entanglement state within the single-excitation regime is the so-called W-state (or single-excitation Dicke state), which has the form

Here, we use negativity, an easily computable bipartite entanglement measure, to measure the bipartite and multipartite entanglement. For bipartite mixed state ρAB, its negativity is defined as \(N({\rho }_{AB})=| | {\rho }_{AB}^{{T}_{A}}| {| }_{1}-1={\sum }_{k}| {\lambda }_{k}| -1=2{\sum }_{k}| {\lambda }_{k}^{neg}|\), where λks and \({\lambda }_{k}^{neg}{\rm s}\) are the eigenvalues and negative eigenvalues of partial transposition matrix \({\rho }_{AB}^{{T}_{A}}\), respectively68. Bennett et al pointed out that a state has genuine n-partite correlations if it is nonproduct in every bipartite cut69. Therefore, via the bipartite entanglement negativity, we can define a measure for genuine multipartite quantum entanglement

where ρn is a n-qubit state, and the bipartite negativity \(N({\rho }_{{i}_{k}| {\overline{i}}_{k}})\) characterizes the quantum correlation between the kth qubit ik and the rest of the system \({\overline{i}}_{k}\). Therefore, the multipartite quantum correlation Nn(ρn) equals zero when the multipartite mixed state is biseparable in any partition. This measure has been extensively employed in numerous many-body systems70,71,72.

The only negative eigenvalue of the partial transpose of the W state is \({\lambda }^{neg}=-\sqrt{n-1}/n\), therefore, the multipartite negativity Nn can be calculated as \({N}_{n}=2\sqrt{n-1}/n\). In reality, not only the normal W state with identical coefficients, for a state of equal probability superposition of \(\left\vert {\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle\), \({\sum }_{i}{c}_{i}\left\vert {\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle\) with \(| {c}_{i}| =1/\sqrt{n}\), the multipartite quantum entanglement Nn is equal to the W state. It can be determined that if the system is prepared at the superposition of antisymmetric state \(\left\vert\,{\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle -\left\vert\,{\boldsymbol{j}}\right\rangle\) initially, the system will always stay at this state, which means that \(\left\vert\,{\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle -\left\vert\,{\boldsymbol{j}}\right\rangle\) along with their superpositions are steady states of the all-to-all system. Consequently, we can conclude that, in the all-to-all n-qubit system, the maximally entangled and perfectly subradiant state can be described as

where Rijs are random complex numbers. Therefore, if the initial state is prepared as in Eq. (21), it is a random superposition of antisymmetric steady states \(\left\vert\,{\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle -\left\vert\,{\boldsymbol{j}}\right\rangle\), and the modulus of the coefficients of each single-excitation component \(\left\vert {\boldsymbol{i}}\right\rangle\) is equal, the system will remain in this n-qubit maximally entangled state. For an even-qubit system, such as a four-qubit system, a steady and maximally entangled state is given by

For an odd-qubit system, like a three-qubit system, a perfectly subradiant and maximally entangled state takes the form

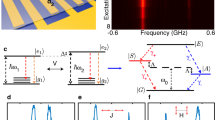

In the rest of this section and the next section, we take a six-qubit system as an example to illustrate the coincidence between the theoretical and numerical results. Panels (a)–(c) of Fig. 1 illustrate the dynamics of multipartite entanglement N6 and bipartite entanglement Nhalf (the entanglement between one half of the system and the rest) for three initial states

respectively. The numerical calculation results (symbols) and theoretical predictions (dashed lines calculated using initial states) are consistent, and the states remain unchanged despite having completely different entanglement distributions. Obviously, all three states are antisymmetric states or their linear superpositions, so they will always stay at the initial states, that is, perfect subradiant states. However, only \(\left\vert {r}_{1}\right\rangle\) fully satisfies the conditions of Eq. (21), namely the maximally entangled steady state; \(\left\vert {r}_{2}\right\rangle\) is a partially multipartite entangled state and \(\left\vert {r}_{3}\right\rangle\) has only bipartite entanglement.

Evolution of multipartite quantum correlation N6 (red squares) and bipartite entanglement Nhalf (blue triangles) with six typical initial states, \(\left\vert {r}_{1}\right\rangle \sim \left\vert {r}_{6}\right\rangle\) shown in the main text correspond to panel (a–f), respectively. Gray dashed and dotted lines represent N6(th) and Nhalf(th) calculated by the final states that are predicted by our theory. g Relationship between the multipartite entanglement of the totally random single-excitation states and their final-state result. The color of the scattered points represents the fidelity between the initial and final states. h A comparison of the calculation time between the numerical and our approach with the same initial state \(\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle\).

The analytical final state of any single-excitation initial state

Among the eigenvalues of the matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\) for a n-qubit single-excitation system, only a few possess a zero real part (steady-state basis), while the remaining eigenvalues are negative (exponentially decaying basis). Consequently, once the eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalues with a zero part is identified, the long-term steady state can be determined. The zero-eigenvalue basis of matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\) is the flattened vectors of

and the purely imaginary-eigenvalue basis (the eigenvalues are ± iω0) is the flattened vectors of

where i, j ∈ [2, n] and i ≠ j, and ϵk is the corresponding eigenvalue of bk. Obviously, the flattened vectors \(\{{\tilde{a}}_{k}\}\) are not orthogonal, and neither are \(\{{\tilde{b}}_{k}\}\). To obtain the final steady-state, we need to orthogonalize \(\{{\tilde{a}}_{k}\}\) and \(\{{\tilde{b}}_{k}\}\) as \(\{{\tilde{A}}_{k}\}\) and \(\{{\tilde{B}}_{k}\}\), respectively. The detailed orthogonalization process is shown in METHODS.

For a single-excitation initial state \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\), its corresponding state at a large time t can be readily obtained as

where the vector \(\left\vert \tilde{v}\right\rangle\) represents the flattened form of the vacuum state \(\left\vert {\mathbf{0}}\right\rangle \left\langle {\mathbf{0}}\right\vert\), while the term \({c}_{0}\left\vert \tilde{v}\right\rangle\) is included to ensure that the trace of the final state equals 1. Except for the eigenvectors \({\tilde{A}}_{k}\) and \({\tilde{B}}_{k}\) corresponding to Eqs. (25) and (26), the eigenvalues of the remaining eigenvectors of matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\) all contain negative eigenvalues. Therefore, the dynamical evolution terms corresponding to these eigenvalues will decay exponentially as time increases, and thus will not be included in the final quantum state with infinite time shown in Eq. (27).

Panels (d)–(f) of Fig. 1 are the multipartite and bipartite entanglement dynamic N6 and Nhalf of three typical six-qubit initial states

The gray dashed and dotted lines in panels (d)–(f) of Fig. 1 represent N6(th) and Nhalf(th) calculated by the final states that are theoretically predicted by Eq. (27). The coincidence of the theoretical and numerical results at a large time verifies that, even if the initial state is not a steady state, our theory can accurately predict its final state, whether it is the generation [panel (d)], reduction [panel (e)] or disappearance [panel (f)] of entanglement. Specifically, if the system is initially prepared in the maximally entangled W state [see panel (f)], it will decay rapidly and evolve into a product state. Nevertheless, if the system is to be maintained in the maximally entangled state, the initial state must be prepared in a form shown in panel (a).

Figure 1g shows the relationship between the multipartite entanglement of totally random single-excitation states and their final-state result. The color of the scattered points in the panel represents the fidelity73 between the initial and final states. The points on the diagonal correspond to the steady-state subradiance indicated by the first line of Eq. (21), where the three points marked by solid red circles represent Fig. 1a–c, and their fidelity is 1. The other three dotted black circles correspond to the three situations shown in Fig. 1d–f. Panel (h) compares the calculation time between the numerical and our approach, demonstrating our theory’s efficiency. Therefore, we can immediately get the exact form of any initial state’s final steady state. More importantly, we can easily find out what initial state the system is prepared to maintain its initial quantum state unchanged. This has a far-reaching significance for the production and storage of quantum resources.

Suppose the incoherent coupling between any two qubits in an n-qubit system is a value α that is close to 1, the steady basis shown in Eqs. (25) and (26) has the corresponding eigenvalues with near-zero real parts α − 1 and α − 1 ± iω0, respectively. In that case, the state at a large time as shown in Eq. (27) can be approximately written as

All the other eigenvalues have finite and negative real parts, so their corresponding dynamics will decay exponentially, thus they are not included in the final states. In Fig. 2(a), we plot the probability \(P=\left\langle r(0)\right\vert \rho (t)\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\) under different αs (shown by different symbols), which is the probability of the system remaining in the initial state \(\left\vert {r}(0)\right\rangle =\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle\) of a six-qubit initial state. The dotted lines are the corresponding theoretical results predicted by Eq. (29). As time increases, theoretical and numerical populations with very different initial values quickly approach, and they almost coincide in the end, regardless of the value of α. To further demonstrate the efficacy of the theory under different αs, we plot the dependence of fidelity between the theoretical and numerical results on α and time t in Fig. 2(b). The colors in the panel represent the difference between the theoretically and numerically calculated multipartite entanglement N6. When time is large, the numerical value of entanglement and the quantum state predicted by our theory is very close to the result of the numerical calculation. This result confirms the validity of Eq. (29), which can accurately predict the evolution of quantum states over a long time even if the system is not a perfect all-to-all situation.

a The numerical calculation of probability P of the system remains in the initial state \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle =\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle\) (marks) and our theoretical prediction (dashed lines) under different αs. b The fidelity between the numerical and theoretical states as a function of time and α. The color represents the difference of N6 between the numerical and theoretical states.

In the above study, we did not consider the effect of coherent dipole-dipole coupling in the system. In fact, the effect of coherent coupling on the emission dynamics of the system is very limited, and the relevant discussions can be found in the METHODS.

Subradiance in a bound state in the continuum

Here, we use the emitters embedded in an all-dielectric daisy photonic crystal slab [as shown in the right inset of Fig. 3a] with zero-index mode which is also symmetry-protected BIC48 to realize the low-loss and all-to-all interactions. As shown in the energy band around Γ point that is presented in the left inset of Fig. 3a, there is a clear Dirac cone and a flat band at Γ point, and the Q-factor of all three bands diverges to infinity. In Fig. 3b, we present the effective index derived through the calculation and interpolation of electric field in high-symmetry positions (dotted green line) \({E}_{z}(r+m\sqrt{3}a)={E}_{z}(r){e}^{i{n}_{e}{k}_{0}m\sqrt{3}a}\) 48, where k0 = ω/c and m takes integer values, and the dashed line is derived directly from the energy band near Γ point, ne = ck/ωk. Both simulation results confirm an effective near-zero index mode near the frequency ωa/(2πc) = 0.486 [as shown in Fig. 3b]. The two insets in Fig. 3b show the normalized spatial field diagram of placing an excited dipole emitter at a high-symmetry point (marked by yellow stars in two insets) when the transition frequency of emitter is near the Γ point [ωa/(2πc) = 0.486] or far away from the Γ point [ωa/(2πc) = 0.47], respectively. As can be seen from two insets, at the Γ point, the near-zero index causes the resonant emitter to produce a highly symmetric and almost non-attenuated field extension in space. However, when the frequency deviates from the Γ point, the spatial field distribution of the emitter is nonuniform. More details about the photonic crystal slab as well as the field distribution diagrams can be found in METHODS, where the BIC-zero-index effect can be observed on a large spatial scale, which suggests that it may be possible to achieve long-range, unattenuated interactions on a large spatial scale.

a Divergent quality factors of Dirac cone and flat band (energy band is shown in the left inset) of a daisy photonic crystal slab as shown in the right inset. b Effective index calculated from the energy band (dashed purple line) and transmission of electromagnetic field (dotted green symbols). Two insets show the field distribution emitted from a single excited emitter (yellow star) embedded in the slab near the Γ point (top left inset) and far away from Γ (bottom right inset). c, d Calculated coherent and incoherent couplings of emitters placed at high symmetry points for different slab sizes. e Subradiant state evolutions of six emitters under several scenarios: the ideal all-to-all case (dash-dotted green line), evolution predicted by Eq. (29) with α = 0.9 (dotted red line), evolution calculated in the BIC mode with (solid purple line) and without coherent coupling (dotted purple line), and the situation in vacuum (dashed blue line).

Figure 3c and d are the calculated normalized pairwise coherent and incoherent couplings of two emitters, g12/γ and γ12/γ, placed at high-symmetry points for different slab sizes, where one emitter is fixed in the center of the slab sample that possesses the spontaneous decay rate γ, and the other has a distance r with it. The coherent coupling between two emitters can be denoted by

while the incoherent coupling is

The Green tensor \({\overleftrightarrow{G}}({\vec{r}}_{1},{\vec{r}}_{2},\omega )\) showed in Eqs. (30) and (31) represents the electric field at position \({\vec{r}}_{1}\) due to a source located at \({\vec{r}}_{2}\) with frequency ω, and the distance between them is \(r=| {\vec{r}}_{1}-\vec{r}_{2}|\). In this work, the dipole moments are all directed along the z axis and have the same electric dipole moment. Therefore, the Green’s function can be obtained by solving for the electric field:

where \({E}_{z}{({\vec{r}}_{1})}_{\vec{{r}}_{2}}\) is the z component of the electric field at \({\vec{r}}_{1}\) emitted from the emitter located at \({\vec{r}}_{2}\). The detailed arrangement of emitters is shown in METHODS.

According to Fig. 3, the coherent couplings g12/γ decrease rapidly with the emitter-emitter distance, and almost turns to zero when the distance between two emitters are large. Nevertheless, the incoherent couplings γ12/γ are relatively uniform, which is also a consequence of the zero index. Figure 3e presents the population of the maximally entangled and steady state \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}(\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle -\left\vert {\mathbf{2}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{3}}\right\rangle -\left\vert {\mathbf{4}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{5}}\right\rangle -\left\vert {\mathbf{6}}\right\rangle )\) under several scenarios. The solid purple line represents the numerical result in the BIC system as shown in Fig. 3a (the emitter arrangement is shown in METHODS), and the dashed blue line is the result for emitters in a vacuum. It can be seen that although the state evolution in the photonic crystal slab has not yet reached the ideal situation (the all-to-all case, denoted by horizontal dash-dotted green line), the rate of state decay is much lower than that in a vacuum, which is definite evidence of subradiance.

The oscillation at the beginning of the evolution originates from the coherent coupling of the nearest neighbors, and its influence on the evolution of the entire state is very limited. This can be seen from the fact that the curves of the dynamical evolution are very close when the coherent coupling is taken as zero (the dotted purple line, denoted by BIC g = 0) during the evolution in the BIC case. The dotted red line is the theoretical result predicted by Eq. (29) with α = 0.9, which is very close to the calculated dynamic evolution curve in the real BIC system, even over a longer period (see inset). That confirms that our theory can predict the dynamical evolution of quantum states on a longer time scale.

It can be verified that BIC-zero-index modes are uniquely suited to achieving autonomous subradiance in our proposed setup, while W-class states as shown in Eq. (21) emerge as a natural resource within this framework, combining maximal multipartite entanglement with autonomous subradiant properties. These findings highlight the potential of BICs and W-class states as versatile tools for quantum information applications, particularly in the context of steady-state subradiance.

Discussion

Subradiance and entanglement preservation exhibit significant sensitivity to decoherence and practical imperfections, such as strong coupling effects, material losses, and fabrication errors in photonic crystals. To improve the experimental feasibility of the scheme, we conduct the following discussions and studies to verify the robustness of the autonomous subradiance against the non-Markovian effects, fabrication disorder, and non-identical couplings.

It is important to note that all dynamical analyses so far have been performed under the Born-Markov approximation. However, non-Markovian effects may significantly influence subradiance in strong-coupling regimes, particularly in experimental setups where memory effects play a crucial role74,75. The impact of non-Markovianity can be highly complex, depending on system-specific factors such as bath properties, environmental feedback, and the number of emitters involved76,77,78,79. For instance, in a waveguide-QED system, non-Markovian effects can further suppress the decay of subradiant states formed by two emitters60. This reduction in decay rates stems from photon retardation-induced nonlocal interactions between qubits, offering a potential mechanism to sustain long-lived quantum entanglement in dissipative systems. Conversely, non-Markovianity also leads to pronounced and intricate quantum beats. While the present theoretical framework focuses solely on weak-coupling regimes, the influence of non-Markovian effects on autonomous subradiance in strong-coupling systems warrants further investigation for a more comprehensive understanding.

Next, we present a detailed analysis of how fabrication imperfections affect the all-to-all coupling condition in daisy photonic crystal slabs. According to ref. 80, the fabrication disorder can be modeled as a triangular sidewall disorder, where the degree of disorder is characterized by the ratio of the triangular height l to the unit cell pitch a, as shown in Fig. 4a. This degree is used to measure the fabrication disorder in the actual BIC photonic crystal slab. Our analysis shows that under small fabrication disorder l/a, the quality factors of three degenerate modes at Γ point slightly decrease, as shown in Fig. 4b; thus, the subradiance remains robust, maintaining its key characteristics, as shown in the dash-dotted orange line in Fig. 4d. However, as the fabrication disorder increases, the quality factor of the photonic crystal decreases (Fig. 4c), leading to an increase in the decay rate of the initial state, as shown in the dotted black line in Fig. 4d. Quantitative results demonstrating the robustness of subradiance under small disorder conditions. However, as the fabrication disorder increases, the quality factor of the photonic crystal decreases, leading to an increase in the decay rate of the initial state.

a A schematic diagram of fabrication disorder use triangular serrated patterns with height l to simulate the roughness of the sidewall. b, c Quality factors of three BIC modes under different roughness levels. d Evolution of the population of the initial state \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\) over time under different roughness levels.

While this work primarily examines autonomous subradiance in all-to-all or near-all-to-all coupling regimes, it is intriguing to investigate its robustness in more general scenarios with non-identical emitter-emitter couplings. Here, we will conduct a comparative study between our autonomous subradiant state \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\) and the W-state under a non-identical coupling scenario in free space. In Fig. 5, we present a study on the comparison between two maximally entangled states in a free space under different inter-emitter distances. One state is the autonomous subradiant state \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}(\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle -\left\vert {\mathbf{2}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{3}}\right\rangle -\left\vert {\mathbf{4}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{5}}\right\rangle -\left\vert {\mathbf{6}}\right\rangle )\), and the other state is the W-state \(\left\vert {W}_{6}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}(\left\vert {\mathbf{1}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{2}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{3}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{4}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{5}}\right\rangle +\left\vert {\mathbf{6}}\right\rangle )\). The curves in Fig. 5 reveal that at large inter-emitter distances, \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\) actually decays faster than the W-state. However, as the distance decreases, \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\) shows rapidly decreasing decay rates but W-state decay more rapidly. In the zero-distance limit (all-to-all coupling), \(\left\vert r(0)\right\rangle\) recovers its ideal subradiant character, but W-state decays more rapidly. These results demonstrate that our autonomous subradiance basis maintains its advantages across a wide range of coupling conditions, not just in the ideal all-to-all case.

Our analysis reveals that the subradiant states engineered in this photonic crystal platform exhibit remarkable robustness against fabrication-induced disorder. Notably, even in free-space coupling schemes where emitter-emitter interactions decay rapidly with emitter separation, the subradiant basis maintains significant advantages over conventional quantum resources (e.g., W-states) in both state and entanglement persistence. These findings significantly expand the scheme’s experimental relevance, confirming that autonomous subradiance remains effective in realistic conditions beyond idealized theoretical constructs.

A theoretical framework has been developed successfully, which is able to reveal quite efficiently the dynamics of single-excitation processes in all-to-all systems, facilitating the prediction of long-lived multipartite entanglement dynamics without intricate integral computations. Utilizing the quantum jump operator method, we have analytically derived the steady-state final state for any single-excitation initial state, including an approximate solution for the quasi-all-to-all coupling scenario. Our results demonstrate unambiguously that the system’s multipartite entanglement, characterized by the negativity measure, remains robust over time, with the steady states exhibiting W-class entanglement. As an illustrative example, we have computed the coupling and dynamics of emitters within a photonic crystal slab possessing an ultra-high quality BIC, thereby validating the efficacy of our theoretical approach. This work not only elucidates a pathway toward realizing autonomous steady-state subradiance and multipartite entanglement in atomic systems but also has significant implications for the production and storage of quantum resources, potentially enabling more efficient quantum information processing and quantum communication protocols.

Methods

Orthogonalization procedure of steady basis

We first present a general orthogonalization procedure on the steady basis, and then we will present an example in the three-qubit case. Here, we take the Gram-Schmidt process81 to orthogonalize the zero-eigenvalue eigenvectors. The Gram-Schmidt process is as follows: given k vectors v1, ⋯ , vk, their orthogonalized vectors can be calculated as

Among the above vectors, proja(b) represents the orthogonal projection of a vector b onto a vector a.

and 〈b, a〉 is the inner product of vectors a and b.

For a three-qubit case, the steady-state basis of zero-eigenvalue can be found in Eq. (25) of the main text. Normalizing these vectors and following the orthogonalization procedure above, we can obtain the orthogonalized and normalized vectors, and their corresponding matrix form A1 ~ A4 can be written as

Similarly, the purely imaginary-eigenvalue basis can be readily found in Eq. (26) of the main text. Following the same orthogonalization procedure, we can obtain the orthogonalized matrix form B1 ~ B4

where \({\tilde{A}}_{1}\) to \({\tilde{A}}_{4}\) are the eigenstates correspond to the eigenvalue 0, \({\tilde{B}}_{1}\) and \({\tilde{B}}_{2}\) correspond to the eigenvalue − iω0, and \({\tilde{B}}_{3}\) and \({\tilde{B}}_{4}\) correspond to the eigenvalue iω0.

For systems with more qubits, the orthogonalized steady-state basis vectors can also be easily obtained according to the above process as well as Eqs. (25) and (26) in the main text. Based on these orthogonalized basis vectors, we can easily obtain the approximate final state of the system.

Role of coherent coupling in emission dynamics

Here, we will verify the dependence of coherent coupling on the emission dynamics under the simplest two-qubit case. The Hamiltonian of the two-qubit system has the form

with g being the coherent coupling between two qubits, and the master equation can be written as

The eigenvalues with zero real part of matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\) of such a two-qubit system can be easily obtained as

and the corresponding normalized eigenvectors are

In this part we consider a general case where the coupling between two distant qubits is close to 1 but not exactly 1, we can also use the theory in the main text to give the quasi-steady state. For the two-qubit case investigated in this part, the decoherence matrix can be written as

with α being the incoherent coupling between two qubits. The eigenvalues of this matrix are Γ± = 1 ± α, and the corresponding normalized eigenvectors are \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}{(1,\pm 1)}^{\top }\).

Here we will take two typical states as the initial states to clarify the dependence of the coherent coupling on our theory and the exact dynamics. The first state is the maximally entangled state, \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert eg\right\rangle -\left\vert ge\right\rangle )\). We have \(\langle {\overline{l}}_{1}| r(0)\rangle =1\) and \(\langle {\overline{l}}_{3}| r(0)\rangle =\langle {\overline{l}}_{4}| r(0)\rangle =0\), thus the final state can be obtained as

It can be verified that this state is the exact solution of the Lindblad master equation. Two-qubit entanglement can be measured with entanglement concurrence82, \(C(\rho )=\max \{0,\sqrt{{\lambda }_{1}}-\sqrt{{\lambda }_{2}}-\sqrt{{\lambda }_{3}}-\sqrt{{\lambda }_{4}}\}\) with λis being the square roots of the eigenvalues of matrix \(\rho \tilde{\rho }\), in decreasing order, and \(\tilde{\rho }=({\sigma }_{y}\otimes {\sigma }_{y}){\rho }^{* }({\sigma }_{y}\otimes {\sigma }_{y})\). Therefore, the two-qubit concurrence of the theoretical final state shown in Eq. (42) can be calculated as C12 = e(α−1)t, which is slowly decaying over time when α is close to 1. Consequently, we know that under the maximally entangled and steady state of the two-qubit system, coherent has no influence on the final state.

For another typical state \(\left\vert eg\right\rangle\), the analytical form of its density matrix over time can be expressed as42

where \({E}_{1}^{t}={e}^{(\alpha -1)t}+{e}^{(-\alpha -1)t}\), \({E}_{2}^{t}={e}^{(-\alpha -1)t}-{e}^{(\alpha -1)t}\), \({E}_{3}^{t}=2\cos (2gt){e}^{-t}\), and \({E}_{4}^{t}=2\sin (2gt){e}^{-t}\), and the exact two-qubit concurrence of the state can be calculated as

The theoretical final state can be calculated as

and it’s concurrence can be calculated as

Comparing these two results, we find that the exact concurrence shown in Eq. (44) will turn to the theoretical one shown in Eq. (46) at a large time t. However, the large coherent coupling g can lead to the wild oscillation at the beginning of the dynamic. This can be clearly observed in Fig. 6.

Details of the bound state in the continuum

In the main text, we selected a photonic crystal slab with BIC characteristics to verify our theory, as shown in Fig. 7(a). The photonic crystal slab is made up of a silicon slab of thickness d = 0.5a, with a dielectric permittivity ϵ=12, that has air holes arranged in a triangular lattice with a lattice constant a, and in actual calculations, we used a triangular sample slab. The shape of the air holes [as shown in the right inset of Fig. 5a] is given as \(r(\theta )=\frac{1}{2}({r}_{2}+{r}_{1})+\frac{1}{2}({r}_{2}-{r}_{1})\cos (6\theta )\) in polar coordinates, where r1 = 0.27a and r2 = 0.43a48.

Panel (a) is a schematic diagram of the BIC photonic crystal slab model, with the right figure showing a detailed diagram of the structure within a single unit cell. Panel (b) illustrates the schematic of the calculation positions for coherent and incoherent coupling, with yellow stars indicating the positions of the emitters and blue dots representing the calculation positions. Panel (c) represents the positions of the emitters (red dots) for the calculation of steady-state evolution in the BIC photonic crystal slab. Panels (d) and (e) show the electric field distribution diagrams in the central cross section of the slab at the BIC and non-BIC frequencies respectively.

Figure 7b depicts the schematic of the emitter arrangement for pairwise coherent and incoherent coupling on the BIC photonic crystal slab, as shown in Fig. 3c and d of the main text. In this diagram, the yellow star denotes the position of the fixed emitter, while the remaining blue dots represent the locations of the other emitters. The red dots in Fig. 7c present the emitter arrangement of six emitters referred in Fig. 3e of the main text. Figure 7d and e present our simulated electric field distributions in the central cross section of the slab, excited by embedded emitters (yellow stars) operating at different frequencies. These plots show the normalized Ez component for a lattice constant a = 800 nm. Specifically, Fig. 7d and e correspond to the BIC frequency ωa/(2πc) = 0.486 and non-BIC frequency ωa/(2πc) = 0.47, respectively. Comparing the field distributions under BIC and non-BIC cases, it can be seen that the field distribution in the slab under BIC is very uniform at high symmetry positions, even at the edge of the slab sample, while the field distribution decreases slightly under non-BIC frequencies. The simulations of the couplings and the field patterns in this work are implemented through the software COMSOL multiphysics.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes used to generate data for this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Amico, L., Fazio, R., Osterloh, A. & Vedral, V. Entanglement in many-body systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 517 (2008).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

Dür, W., Vidal, G. & Cirac, J. I. Three qubits can be entangled in two inequivalent ways. Phys. Rev. A 62, 062314 (2000).

Zhao, B., Chen, Z.-B., Chen, Y.-A., Schmiedmayer, J. & Pan, J.-W. Robust Creation of Entanglement between Remote Memory Qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 240502 (2007).

Gu, M., Wiesner, K., Rieper, E. & Vedral, V. Quantum mechanics can reduce the complexity of clasical models. Nat. Commun. 3, 762 (2012).

Briegel, H. J. & Raussendorf, R. Persistent Entanglement in Arrays of Interacting Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 910 (2001).

Bell, B. A. et al. Experimental demonstration of a graph state quantum error-correction code. Nat. Commun. 5, 3658 (2014).

Livingston, W. P. et al. Experimental demonstration of continuous quantum error correction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2307 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Encoding Error Correction in an Integrated Photonic Chip. PRX Quantum 4, 030340 (2023).

Dirac, P. A. M. The quantum theory of the emission and absorption of radiation. Proc. R. Soc. A 114, 243 (1927).

Dicke, R. H. Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 93, 99 (1954).

Rehler, N. E. & Eberly, J. H. Superradiance. Phys. Rev. A 3, 1735 (1971).

Gross, M. & Haroche, S. Superradiance: an essay on the theory of collective spontaneous emission. Phys. Rep. 93, 301 (1982).

Lehmberg, R. H. Radiation from an N-atom system. I. General formalism. Phys. Rev. A 2, 883 (1970).

Agarwal, G. S. Master-equation approach to spontaneous emission. Phys. Rev. A 2, 2038 (1970).

Milonni, P. W. & Knight, P. L. Retardation in the resonant interaction of two identical atoms. Phys. Rev. A 10, 1096 (1974).

Reimann, R. et al. Cavity-Modified Collective Rayleigh Scattering of Two Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 023601 (2015).

Hebenstreit, M., Kraus, B., Ostermann, L. & Ritsch, H. Subradiance via entanglement in atoms with several independent decay channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 143602 (2017).

Guimond, P.-O., Grankin, A., Vasilyev, D. V., Vermersch, B. & Zoller, P. Subradiant Bell states in distant atomic arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 093601 (2019).

Masson, S. J., Ferrier-Barbut, I., Orozco, L. A., Browaeys, A. & Asenjo-Garcia, A. Many-body signatures of collective decay in atomic chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 263601 (2020).

Robicheaux, F. Theoretical study of early-time superradiance for atom clouds and arrays. Phys. Rev. A 104, 063706 (2021).

Ruks, L. & Busch, T. Green’s functions of and emission into discrete anisotropic and hyperbolic baths. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023044 (2022).

Rubies-Bigorda, O. & Yelin, S. F. Superradiance and subradiance in inverted atomic arrays. Phys. Rev. A 106, 053717 (2022).

Masson, S. J. & Asenjo-Garcia, A. Universality of Dicke superradiance in arrays of quantum emitters. Nat. Commun. 13, 2285 (2022).

Mok, W.-K., Asenjo-Garcia, A., Sum, T. C. & Kwek, L.-C. Dicke superradiance requires interactions beyond nearest neighbors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 213605 (2023).

Cardenas-Lopez, S., Masson, S. J., Zager, Z. & Asenjo-Garcia, A. Many-body superradiance and dynamical mirror symmetry breaking in waveguide QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 033605 (2023).

Tiranov, A. et al. Collective super- and subradiant dynamics between distant optical quantum emitters. Science 379, 389 (2023).

Guerin, W., Araújo, M. O. & Kaiser, R. Subradiance in a large cloud of cold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 083601 (2016).

Rui, J. et al. A subradiant optical mirror formed by a single structured atomic layer. Nature 583, 369 (2020).

Cipris, A. et al. Subradiance with saturated atoms: population enhancement of the long-lived states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 103604 (2021).

Ferioli, G., Glicenstein, A., Henriet, L., Ferrier-Barbut, I. & Browaeys, A. Storage and release of subradiant excitations in a dense atomic cloud. Phys. Rev. X 11, 021031 (2021).

Takasu, Y. et al. Controlled production of subradiant states of a diatomic molecule in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 173002 (2012).

McGuyer, B. H. et al. Precise study of asymptotic physics with subradiant ultracold molecules. Nat. Phys. 11, 32 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Controllable switching between superradiant and subradiant states in a 10-qubit superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 013601 (2020).

Gonzalez-Tudela, A. et al. Entanglement of two qubits mediated by one-dimensional plasmonic waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 020501 (2011).

Martín-Cano, D., Martín-Moreno, L., García-Vidal, F. J. & Moreno, E. Resonance energy transfer and superradiance mediated by plasmonic nanowaveguides. Nano Lett. 10, 3129 (2010).

Pustovit, V. N. & Shahbazyan, T. V. Plasmon-mediated superradiance near metal nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 82, 075429 (2010).

Mlynek, J. A., Abdumalikov, A. A., Eichler, C. & Wallraff, A. Observation of Dicke superradiance for two artificial atoms in a cavity with high decay rate. Nat. Commun. 5, 5186 (2014).

Goban, A. et al. Superradiance for atoms trapped along a photonic crystal waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 063601 (2015).

Ren, J., Wu, T., Yang, B. & Zhang, X. Simultaneously giant enhancement of Förster resonance energy transfer rate and efficiency based on plasmonic excitations. Phys. Rev. B 94, 125416 (2016).

de Torres, J., Ferrand, P., Colas des Francs, G. & Wenger, J. Coupling emitters and Silver Nanowires to Achieve Long-Range Plasmon-Mediated Fluorescence Energy Transfer. ACS Nano 10, 3968 (2016).

Ren, J., Chen, T., Wang, B. & Zhang, X. Ultrafast coherent energy transfer with high efficiency based on plasmonic nanostructures. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 144101 (2017).

Ren, J., Chen, T. & Zhang, X. Long-lived quantum speedup based on plasmonic hot spot systems. New J. Phys. 21, 053034 (2019).

Kodigala, A. et al. Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum. Nature, 541, 196 (2017).

Muhammad, N., Chen, Y., Qiu, C. W. & Wang, G. P. Optical bound states in continuum in MoS2-based metasurface for directional light emission. Nano Lett. 21, 967 (2021).

Dyakov, S. A. et al. Photonic bound states in the continuum in Si structures with the self-assembled Ge nanoislands. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2000242 (2021).

Kang, M., Liu, T., Chan, C. T. & Xiao, M. Applications of bound states in the continuum in photonics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 659 (2023).

Minkov, M., Williamson, I. A. D., Xiao, M. & Fan, S. Zero-index bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 263901 (2018).

Peng, Y. & Liao, S. Bound States in Continuum and Zero-Index Metamaterials: A Review, arXiv:200701361, (2020).

Joseph, S., Pandey, S., Sarkar, S. & Joseph, J. Bound states in the continuum in resonant nanostructures: an overview of engineered materials for tailored applications. Nanophoton. 10, 4175 (2021).

Ziolkowski, R. W. Propagation in and scattering from a matched metamaterial having a zero index of refraction. Phys. Rev. E 70, 046608 (2004).

Alù, A., Silveirinha, M. G., Salandrino, A. & Engheta, N. Epsilon-near-zero metamaterials and electromagnetic sources: Tailoring the radiation phase pattern. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155410 (2007).

Engheta, N. Pursuing Near-Zero Response. Science 340, 286 (2013).

Maas, R., Parsons, J., Engheta, N. & Polman, A. Experimental realization of an epsilon-near-zero metamaterial at visible wavelengths. Nat. Photonics 7, 907 (2013).

Liberal, I. & Engheta, N. Near-zero refractive index photonics. Nat. Photonics 11, 149 (2017).

Li, Y. & Argyropoulos, C. Exceptional points and spectral singularities in active epsilon-near-zero plasmonic waveguides. Phys. Rev. B 99, 075413 (2019).

Zhu, S., Su, L.-L. & Ren, J. Tunable couplings between location-insensitive emitters mediated by an epsilon-near-zero plasmonic waveguide. Opt. Express 31, 28575 (2023).

Liedl, C. et al. Observation of superradiant bursts in a cascaded quantum system. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011020 (2024).

Ren, J., Zhu, S. & Wang, Z. D. Attaining nearly ideal Dicke superradiance in expanded spatial domains. Phys. Rev. Applied 21, 044053 (2024).

Zheng, H. & Baranger, H. U. Persistent quantum beats and long-distance entanglement from waveguide-mediated interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 113601 (2013).

Ostermann, L., Meignant, C., Genes, C. & Ritsch, H. Super- and subradiance of clock atoms in multimode optical waveguides. New J. Phys. 21, 025004 (2019).

Fasser, M., Ostermann, L., Ritsch, H. & Hotter, C. Subradiance and superradiant long-range excitation transport among quantum emitter ensembles in a waveguide. Opt. Quantum 2, 397 (2024).

Shankar, A., Reilly, J. T., Jäger, S. B. & Holland, M. J. Subradiant-to-Subradiant Phase Transition in the Bad Cavity Laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 073603 (2021).

Bin, Q. & Lü, X.-Y. Steady-state subradiance manipulated by the two-atom decay. Phys. Rev. A 106, 063701 (2022).

Dung, H. T., Knöll, L. & Welsch, D.-G. Resonant dipole-dipole interaction in the presence of dispersing and absorbing surroundings. Phys. Rev. A 66, 063810 (2002).

Carmichael, H. J. & Kim, K. A quantum trajectory unraveling of the superradiance master equation. Opt. Commun. 179, 417 (2000).

Clemens, J. P., Horvath, L., Sanders, B. C. & Carmichael, H. J. Collective spontaneous emission from a line of atoms. Phys. Rev. A 68, 023809 (2003).

Vidal, G. & Werner, R. F. Computable measure of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 65, 032314 (2002).

Bennett, C. H., Grudka, A., Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Postulates for measures of genuine multipartite correlations. Phys. Rev. A 83, 012312 (2011).

Bayat, A. Scaling of tripartite entanglement at impurity quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 036102 (2017).

Su, L.-L., Ren, J., Wang, Z. D. & Bai, Y.-K. Long-range multiaprtite quantum correlations and factorization in a one-dimensional spin-1/2 XY chain. Phys. Rev. A 106, 042427 (2022).

Su, L.-L., Ren, J., Ma, W.-L., Wang, Z. D. & Bai, Y.-K. Diagnosing quantum phases using long-range two-site quantum resource behavior. Phys. Rev. B 110, 104101 (2024).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2000).

Breuer, H.-P., Laine, E.-M., Piilo, J. & Vacchini, B. Colloquium: Non-Markovian dynamics in open quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 021002 (2016).

Vega, I. D. & Alonso, D. Dynamics of non-Markovian open quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015001 (2017).

González-Tudela, A. & Cirac, J. I. Markovian and non-Markovian dynamics of quantum emitters coupled to two-dimensional structured reservoirs. Phys. Rev. A 96, 043811 (2017).

González-Tudela, A. & Cirac, J. I. Quantum emitters in two-dimensional structured reservoirs in the nonperturbative regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 143602 (2017).

Liu, F., Zhou, X.-X. & Zhou, Z.-W. Memory effect and non-Markovian dynamics in an open quantum system. Phys. Rev. A 99, 052119 (2019).

Sinha, K., Meystre, P. & Goldschmidt, E. A. Non-Markovian Collective Emission from Macroscopically Separated Emitters. Phys. Rev. Lett 124, 043603 (2020).

Tang, H. et al. Low-Loss Zero-Index Materials. Nano Lett. 21, 914 (2021).

David, B. L. and Trefethen, L. N. Numerical linear algebra (Society for lndustrial and Applied Mathematics, 1997).

Wootters, W. K. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSF-China (Grant Nos. 11904078 and 11575051), GRF (Grant Nos. 17310622 and 17303023) of Hong Kong, Hebei NSF (Grant Nos. A2021205020 and A2019205266), and Hebei 333 Talent Project (B20231005). J.R. was also funded by the project of the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2020M670683).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to verifying the results and writing the manuscript. J.R. and Z.D.W. conceived the project and supervised the work. J.R. developed the autonomous subradiance theory and performed the numerical simulations. M.C. performed the simulations in BIC system.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, MJ., Ren, J. & Wang, Z.D. Deterministic steady-state subradiance within a single-excitation basis. npj Quantum Inf 11, 99 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01051-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01051-8