Abstract

Rydberg atoms have stood out as a highly promising platform for realizing quantum computation. Floquet frequency modulation (FFM), in Rydberg atom systems, provides a unique tool for achieving precise quantum control and uncovering exotic physical phenomena. This work introduces a method to realize controlled arbitrary phase gates in Rydberg atoms by manipulating system dynamics using FFM. Notably, the need for laser addressing of individual atoms is eliminated, enhancing convenience for practical applications. Furthermore, this approach is integrated with soft quantum control strategies to enhance the fidelity and robustness of the resultant controlled-phase gates. Finally, as an example, this methodology is applied in Grover-Long algorithm to search target items with zero failure rate, demonstrating its substantial significance for future quantum information processing applications. This work leveraging Rydberg atoms and FFM may herald a new era of scalable and reliable quantum computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to unique advantages and exotic dynamics, neutral atoms have emerged as one of the most promising and rapidly developing platforms in quantum computation and quantum many-body physics1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. When excited to Rydberg states, neutral atoms exhibit relatively long lifetimes and strong Rydberg-Rydberg interaction (RRI)9,10,11,12,13, which can manifest as the form of dipole-dipole or van der Waals forces. This interaction gives rise to the Rydberg blockade mechanism, wherein the excitation of one atom to the Rydberg state prevents the excitation of neighboring atoms2,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. This phenomenon has been extensively utilized for the implementation of quantum logic gates6,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 and holds significant promise for various applications in quantum computing, with ongoing experimental advancements30,31,32. Furthermore, this feature allows quantum information to be encoded in the collective states of atomic ensembles, enabling the realization of mesoscopic quantum information processing and thus forming Rydberg superatoms33,34,35. Beyond the Rydberg blockade mechanism, Rydberg anti-blockade (RAB)36,37,38,39,40,41,42 constitutes a critical dynamical process in neutral atomic systems, enabling the simultaneous excitation of multiple atoms to strongly interacting states. In particular, RAB permits a resonant two-photon transition between ground-state pairs and doubly excited Rydberg states in diatomic systems, thus playing a pivotal role in the realization of two-atom phase gates43,44,45 and the preparation of steady-state entanglement37,38,46. In addition to conventional Rydberg blockade and antiblockade effects, diverse dynamical regimes have been explored based on interacting Rydberg atoms. For example, the unconventional Rydberg pumping (URP) mechanisms has been developed47 freezes the system dynamics even when the coupling between ground and Rydberg states is switched on. Moreover, the selective Rydberg pumping (SRP) represents another particularly intriguing dynamics in Rydberg atom systems48. This mechanism enables selective resonance pumping of the two-atom ground state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) to a single-excited Rydberg state while effectively suppressing transitions from the other three ground states \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 01\right\rangle\), and \(\left\vert 10\right\rangle\). Such state-selective control offers a powerful and reliable approach for precisely manipulating quantum system dynamics, significantly advancing our capability to engineer quantum states with high fidelity.

Alternatively, in the realm of coherent quantum dynamics control, periodic driving serves as a prevalent method for state manipulation49,50,51,52,53. By applying Floquet frequency modulation (FFM), which involves periodic modulation of quantum systems at elevated frequencies, dynamic stability can be achieved54,55,56. Furthermore, through the judicious selection of appropriate modulation amplitude and frequency, the Rabi coupling strength can be effectively regulated. This significantly enhances the dynamics of quantum systems, providing a broader array of choices for manipulating quantum systems. By periodically modulating the atom-field detuning, FFM provides a robust approach to realizing RAB dynamics, irrespective of the strength of the RRI. This technique significantly enhances RAB processes and enables the stabilization of long-lived Rydberg states with strong interactions, even for closely spaced atoms. The practical execution of quantum computation necessitates the efficient and resilient deployment of quantum logic gates57,58,59,60,61 to enable the completion of numerous quantum tasks. Nevertheless, most of existing dynamic protocols often fall short of meeting this demand.

In this work, we employ the FFM method to tailor Rydberg interaction for implementing quantum computation. The versatile applications of FFM in coherent quantum system control allow for the exploration of diverse quantum phenomena. Through the manipulation of frequency-modulation parameters of driving field, the system dynamics can be adeptly regulated to realize robust quantum gates. The integration of FFM with advanced quantum control of Rydberg atoms may open new avenues for efficient and robust quantum computation, paving the way for practical implementations of complex quantum algorithms and the exploration of novel quantum phenomena in coherently controlled systems, which is based on the following features of our present work on exploring exotic dynamics in Rydberg atoms for quantum computation. This potential stems from our exploration of exotic dynamics for Rydberg-atom quantum computation, holding the following key features.

Firstly, previous studies on periodic driving primarily focused on specific dynamic phenomena without providing a comprehensive analytical framework50,54. In contrast, we derive an exact analytical solution, enabling universal realization of both RAB and URP regimes. Uniquely, while the referenced URP regime requires two driving fields47, our protocol achieves the same effect with just one. More importantly, unlike traditional second-order RAB regimes44,62,63,64,65, our scheme operates with undegraded dynamics, significantly enhancing the speed of running the system evolution. Secondly, compared with existing three-step Rydberg-blockade–based two-qubit gates and periodical-driving–induced two-qubit Rydberg gates that necessitate individual laser addressing45,66, our approach accomplishes the gate task in a single step without requirement of individual addressing on atoms. Thirdly, we employ FFM to periodically modulate the atom-field detuning, thereby overcoming the constraints imposed by RAB on atomic separations. Simultaneously, owing to the intricate dynamics inherent in the Floquet system, various control parameter values can be chosen to implement the C-Phase gates, which provides a clear optimal choice for us both in terms of gate time and attainable fidelities. Finally, we integrate the constructed C-Phase gate with Gaussian soft quantum control optimization techniques67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75, thereby improving the fidelity of the C-Phase gate and mitigating the occurrence of undesirable high-frequency oscillations during the evolution process. In addition, as an important example of application, we turn to apply our Floquet Rydberg-atom C-Phase gates for implementing Grover-Long search algorithm76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85. By carrying out the phase rotation by an arbitrary angle, Grover-Long algorithm enables the target items search with high success rate to be realized effectively78. Our approach facilitates multi-item searching with a unit success probability, eliminating the necessity for individual addressing and simplification of the quantum circuit offers a promising and feasible avenue for the practical implementation of the algorithm.

Results

Model and Hamiltonian

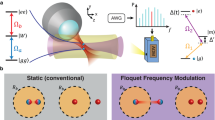

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we consider a scenario involving two neutral atoms interacting via RRI. Each atom is stimulated from the hyperfine ground state \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) to the Rydberg excited state \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\) with Rabi frequency denoted as Ω(t)eiϕ(t) and detuning Δ(t). In the interaction picture with rotating-wave approximation (RWA), the evolution of the system is governed by the Hamiltonian (ℏ ≡ 1)

where i indexes the i-th atom, V represents the RRI strength of the Van der Waals type, and the laser detuning \(\Delta (t)={\Delta }_{0}+\delta \sin ({\omega }_{0}t)\) undergoes sinusoidal FFM with the modulation frequency ω0 and the modulation amplitude δ. The notation \(\left\vert ab\right\rangle \equiv {\left\vert a\right\rangle }_{1}\otimes {\left\vert b\right\rangle }_{2}\) is employed throughout this study for conciseness. In implementing FFM, we can utilize a Rydberg excitation laser controlled by an acoustic-optic modulator (AOM) driven by an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG). Unlike conventional Floquet engineering techniques where FFM does not rely on periodic pulses but it directly alters the effective coupling between energy levels86,87.

Each atom comprises two hyperfine ground states, denoted as \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\), alongside a Rydberg excited state represented by \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\). Simultaneously, both atoms undergo excitation from state \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) to state \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\) with Rabi frequency Ω(t)eiϕ(t) and detuning Δ(t), while exhibiting Rydberg interactions between their respective \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\) states.

Now we introduce the unitary operator, \({\hat{U}}(t)={\exp}\left[-if(t)\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{2}|r|_{i}\left\langle r\right| -iVt\left|rr\right\rangle \left\langle rr\right|\right]\) with \(f(t)=-{\Delta }_{0}t+\delta /{\omega }_{0}\cos ({\omega }_{0}t)\), the Hamiltonian (1) is transformed into \({\hat{H}}^{{\prime} }(t)=i{\dot{\hat{U}}}^{{\dagger} }(t)\hat{U}(t)+{\hat{U}}^{{\dagger} }(t)\hat{H}\hat{U}(t)\), calculated as

in which the single-excitation intermediate state is denoted as \(\left\vert W\right\rangle =(\left\vert 1r\right\rangle +\left\vert r1\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\). We define the modulation index α = δ/ω0 and assume Δ0 = 0 for simplicity. By employing the Jacobi-Anger expansion \(\exp [\pm i\alpha \cos {\omega }_{0}t]=\mathop{\sum }_{m = -\infty }^{\infty }{J}_{m}(\alpha )\exp [\pm im({\omega }_{0}t+\pi /2)]\), the modified Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}^{{\prime} }(t)\) can be expressed as

where Jm(α) represents the mth order Bessel function of the first kind. To simplify subsequent analyses, the Rabi frequencies between the states are individually rescaled to

By selecting a significantly high modulation frequency ω0, the Rabi frequencies Ωa(t) and Ωb(t) are predominantly influenced by the resonance terms in Eq. (4). Specifically, the Rabi frequency Ωa(t) is governed by J0(α), whereas for Ωb(t), we establish mω0 = −V to satisfy the resonance criterion.

For a more intuitive analysis, we partition the system dynamics into distinct sectors, specifically involving the computational states \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 01\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 10\right\rangle\), and \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\). The state \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle\) remains unchanged as \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) is decoupled to the driving field. In the cases of the initial states \(\left\vert 01\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 10\right\rangle\), the dynamics can be described in the two-level systems, respectively, governed by

For the initial state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\), however, it is reduced into a three-level system with the Hamiltonian

The quite difference between Hamiltonian expressions in the cases of initial states \(\left\vert 01\right\rangle\) (\(\left\vert 10\right\rangle\)) and \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) is the very essence to achieve nontrivial two-atom quantum gates.

C-Phase gate of two Rydberg atoms

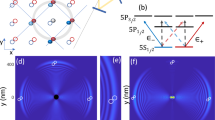

In this section, we utilize the FFM scheme to construct a universal two-qubit C-Phase gate, capitalizing on its intricate dynamics. By varying the modulation index α and modulation frequency ω0, we present the time-average population50,54 of the doubly excited Rydberg state \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) within 10 μs in Fig. 2a with the RRI strength of V = 20Ω. The results indicate that the FFM scheme can effectively manipulate the dynamic behavior of system according to the population behaviors of \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\). Notably, when the resonance condition ω0 = V is satisfied, the population of the \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) state is primarily modulated by J0(α) and J1(α). By selecting values of α at which either J0(α) or J1(α) vanishes, the population of \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) state can be effectively suppressed. Moreover, the conventional RAB effect necessitates operating outside the atomic blockade radius, which restricts the interaction strength V to very small values1,43. However, as illustrated in Fig. 2a, even for significantly large V, the doubly excited Rydberg state can still be realized by selecting the appropriate parameter α. This finding effectively overcomes the inherent limitations of the traditional RAB mechanism, particularly in terms of interaction strength and interatomic distance constraints.

a The time-average population of \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) varies as a function of the modulation index α and the normalized modulation frequency ω0/Ω. The red and green dashed curves correspond to J0(α) = 0 and J1(α) = 0, respectively. b Dynamics of transitions among the four ground states: the \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle\) state remains unaltered, transitions of the \(\left\vert 01\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 10\right\rangle\) states exhibit Rabi oscillations with the same Rabi frequency Ωa(t), while the \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) state is excited to the \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) state via the intermediate state \(\left\vert W\right\rangle\) with equivalent Rabi frequencies of \(\sqrt{2}{\Omega }_{a}(t)\) and \(\sqrt{2}{\Omega }_{b}(t)\), respectively.

To construct the desired two-qubit C-Phase gate \({\hat{U}}_{CP}=\) diag (1, −eiϑ, −eiϑ, 1), we employ two sequential identical Rydberg global pulses with equal duration τ but a laser phase jump ϑ inserted between the two pulses. Here, we first analyze the case of a square pulse (SP) sequence. In this scenario, the duration of each pulse segment is denoted as τ = π/ΩJ0(α), and the total gate time is correspondingly 2τ. The specific pulse sequence can be described as follows: when 0 < t ≤ τ, Ω(t) = Ω, and τ < t ≤ 2τ, Ω(t) = Ωeiϑ. Utilizing the unitary operator \({\hat{U}}_{f}=\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{f}{\exp}\left(-i\int_{0}^{2\tau }{\hat{H}}_{f}(t)dt\right)\), where f = 00, 01, 10, 11 and \({\hat{H}}_{00}(t)=0\), each pulse induces a transformation in the atomic states. An in-depth exploration into the evolution of the four computational basis states under the impact of \({\hat{U}}_{CP}\) is presented in Fig. 2(b). The state \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle\) is unaffected by these pulses with \({\hat{U}}_{f}\left\vert 00\right\rangle =\left\vert 00\right\rangle\), while the states \(\left\vert 01\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 10\right\rangle\) return to themselves with an additional phase factor represented by \({\hat{U}}_{f}\left\vert 01\right\rangle (\left\vert 10\right\rangle )=-{e}^{i\vartheta }\left\vert 01\right\rangle (\left\vert 10\right\rangle )\) after a duration of 2τ. Lastly, concerning the evolution of the state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\), our objective is to return it to the same state without accumulating any phase after the complete evolution. This is achieved by appropriately selecting the time-dependent functions ∣Ωa(t)∣ and ∣Ωb(t)∣. Thus, we define ∣Ωb(t)∣ as N times ∣Ωa(t)∣ and evaluate the time evolution operator \({\hat{U}}_{f}\) for the corresponding three-level system using Eq. (7). By applying the condition \({\hat{U}}_{f}\left\vert 11\right\rangle =\left\vert 11\right\rangle\), we can analyze the changes in population P11 and phase Φ11 of the state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) as N varies. It can be seen that when

the population P11 = 1 and the phase Φ11 = 0 are satisfied, the numerical result shown in Fig. 3a also prove this, and the state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) undergoes self-evolution without accumulating any additional phase. In other words, we can choose various values of n for the realization of the universal C-Phase gate, which undoubtedly demonstrates the unique advantages of our FFM scheme, enriching the dynamics of the quantum system and offering diversified options for the construction of quantum gates. With increasing n, the population of the state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) remains close to 1 due to the significant disparity between ∣Ωb(t)∣ and ∣Ωa(t)∣. This intriguing behavior, similar to the URP mechanism47, effectively freezes the evolution of a two-atom system featuring the same ground states. Therefore, our protocol offers a reliable approach for implementing the URP mechanism. By selecting a sufficiently large value of N, the URP mechanism can be achieved using just a single driving field.

a Diagram illustrating the variations in population and phase of \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) as the ratio N of ∣Ωb(t)∣ to ∣Ωa(t)∣ is altered. b Evolution of the Bessel function of the first kind with respect to the modulation index α, denoting J0 and J1 as the zeroth and first order Bessel functions of the first kind, respectively.

To satisfy the resonance conditions detailed in Eq. (4), we assign ω0 = V such that the coupling strength between the singly-excited state \(\left\vert W\right\rangle\) and the doubly-excited state \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) is primarily influenced by J1(α), while the Rabi frequency between the state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) and state \(\left\vert W\right\rangle\) is predominantly governed by J0(α). This configuration ensures that ∣Ωb(t)∣ = N∣Ωa(t)∣ is equivalent to J1(α) = NJ0(α), enabling us to select a suitable modulation index α to attain the desired nontrivial two-qubit gate illustrated in Fig. 3b. The aforementioned FFM approach facilitates the realization of the two-qubit C-Phase gate: \({\hat{U}}_{CP}=\) diag (1, −eiϑ, −eiϑ, 1) in reference to the computational basis \(\{\left\vert 00\right\rangle ,\left\vert 01\right\rangle ,\left\vert 10\right\rangle ,\left\vert 11\right\rangle \}\).

Parameter selection and numerical simulation

In this section, we employ feasible experimental parameters to conduct a numerical simulation for testing the performance of our FFM scheme. The excitation process from the ground state \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) to the Rydberg state \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\) can be achieved via a two-photon mechanism in 87Rb atoms6,7,88. Within the FFM scheme, to meet the condition V = ω0 ≫ Ω, it is necessary to have Rydberg states characterized by sufficiently high principal quantum numbers or close interatomic separations to ensure a potent RRI strength. Hence, we consider energy levels as two hyperfine ground states \(\vert 0\rangle =\vert 5{S}_{1/2},F=1,{m}_{F}=1\rangle\) and \(\vert 1\rangle =\vert 5{S}_{1/2},F=2,{m}_{F}=2\rangle\)89, an intermediary state \(\vert p\rangle =\vert 5{p}_{3/2}\rangle\) or \(\vert p\rangle =\vert 6{p}_{3/2}\rangle\), and the Rydberg strongly-interacting state \(\vert r\rangle =\vert 70{S}_{1/2}\rangle\) possessing an interaction coefficient of C6/2π = 858.4 GHz μm6. For an accessible atomic temperature Ta = 10 μK, the lifetime τr of the Rydberg state \(\vert r\rangle\) in 87Rb atoms with a principal quantum number 70 is ~400 μs6. The strength of RRI is set as V = 2π × 70.18 MHz, considering an interatomic separation of d = 4.8 μm88,90.

To study evolution of the two-atom system, we utilize the Lindblad master equation to assess the gate performance under dissipative effects, expressed as

where \({\hat{\rho}} (t)\) represents the density matrix operator corresponding to the two-atom system, \({\hat{H}}(t)\) stands for the time-varying Hamiltonian of the system as depicted in Eq. (1), and the dissipation terms \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{r}[\hat{\rho }]\) account for the spontaneous decay originating from the strongly-interacting states, elucidated as

in which the Lindblad operators \({\hat{L}}_{j}^{i}=\sqrt{{\gamma }_{j}}{\vert j\rangle }_{i}\langle r\vert\) represent the jump operators characterizing the spontaneous emission of the atom from the Rydberg state \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\) to a ground state \(\left\vert j\right\rangle\), where γj represents the decay rate from \(\left\vert r\right\rangle\) to the ground state \(\left\vert j\right\rangle\). Here we assume γ0 = γ1 = 1/(2τr) with τr being the lifetime of the Rydberg state.

To demonstrate the efficacy and resilience of our proposed two-qubit C-Phase gate across diverse initial conditions, we evaluate the average fidelity91

in which \(\hat{U}\) represents the perfect logic gate, \({\hat{U}}_{k}\) stands for the tensor of Pauli matrices \(\hat{I}\hat{I},\hat{I}{\hat{\sigma }}_{x},\hat{I}{\hat{\sigma }}_{y},\hat{I}{\hat{\sigma }}_{z},...,{\hat{\sigma }}_{z}{\hat{\sigma }}_{z}\) for a two-qubit gate, dk = 2x, with x being the number of qubits in a quantum gate and in this case, dk = 4. \(\xi ({\hat{U}}_{k})\) denotes the trace-preserving quantum operation achieved by solving the master equation (9).

As illustrated by the cyan dashed line in Fig. 4a, the average fidelity of the C-Phase gate we have constructed varies with the Rabi frequency ranging from 2π × 1 MHz to 2π × 20 MHz when n = 0, which indicates that the Rydberg blockade condition Ω ≪ V should be satisfied to attain a relatively higher and stable gate fidelity. For subsequent analysis, we selected a time-independent Rabi frequency of 2π × 3.5 MHz. In Fig. 4b, we present the evolving average fidelity of the C-Phase gate with ϑ = π/2 for n = 0, 1, 2, 3 corresponding to the gate time T = 2π/∣Ωa(t)∣, yielding final average fidelities of 0.9973, 0.9870, 0.9856, and 0.9647, respectively. It can be observed that for n = 0, the achieved gate fidelity is the highest with the shortest gate time. Conversely, for n = 1, 2 and 3, the gate time increases due to the decreasing values of selected J0(α) and J1(α), leading to a decline in the gate fidelity influenced by the non-resonant terms and dissipation of system.

a The average fidelity of the constructed C-Phase gate fluctuates as the square pulse Rabi frequency Ω and the Gaussian pulse maximum amplitude Ωg ranges from 2π × 1 MHz to 2π × 20 MHz when n = 0. b The evolution of the average gate fidelity of the implemented C-Phase gate over time, when n equals 0,1,2,3. The time-independent Rabi frequency Ω = 2π × 3.5 MHz, V = ω0 = 2π × 70.18 MHz, and the gate duration being T = 2π/∣Ωa(t)∣. c The temporal progression of the average gate fidelity for the C-Phase gate utilizing Gaussian soft quantum control when n = 0,1,2,3. The time-dependent Rabi frequency is given by Ωg(t) with the maximum amplitude Ωg = 2π × 8.1 MHz, \({T}_{g}=(-1+a)\pi /| {\Omega }_{g}(t)| {J}_{0}(\alpha )(4a-\sqrt{\pi })\) and a gate time of T = 8Tg. Additionally, V = ω0 = 2π × 70.18 MHz.

Gaussian-pulse optimization

Observing from Fig. 4b and the cyan dashed line of Fig. 4a, we note that the fidelity evolution exhibits pronounced oscillations due to imperfect parameter settings aimed at mitigating the high-frequency oscillations. These substantial oscillations render the resultant C-Phase gate particularly susceptible to control errors. To address this issue, we leverage the technique of soft quantum control67 to refine the parameters for better adherence to RWA conditions, thus damping the high-frequency oscillatory effects and reducing parameter uncertainties during the phase accumulation, ultimately enhancing the gate performance.

Under the implementation of soft quantum control, the time-independent SP with Rabi frequency Ω can be transformed into a time-evolving Gaussian pulse (GP), given by

where Ωg and Tg denote the maximum amplitude and width of GP, respectively. Furthermore, a = exp \([-{(2{T}_{g})}^{2}/{T}_{g}^{2}]\) and b = exp \([-{(T/2-6{T}_{g})}^{2}/{T}_{g}^{2}]\) causing the amplitude is zero at the start and end. Ensuring the pulse area remains constant, we deduce \({T}_{g}=(-1+a)\pi /| {\Omega }_{g}(t)| {J}_{0}(\alpha )(4a-\sqrt{\pi })\) by satisfying \(\int_{0}^{4{T}_{g}}{\Omega }_{g}(t)dt=\pi\) and \(\int_{4{T}_{g}}^{{t}_{g}}{\Omega }_{g}(t)dt=\pi\) with the gate time T = 8Tg. To highlight the distinctive superiority of the GP over the SP, the variation in gate fidelity with respect to the GP’s maximum amplitude under soft control is illustrated by the solid red line in Fig. 4a. The findings demonstrate that this approach noticeably enhances gate performance and facilitates a more gradual evolution of fidelity. Employing this GP configuration, we choose the maximum amplitude Ωg = 2π × 8.1 MHz so that the optimized gate time is consistent with the SP and illustrate the average gate fidelity of the C-Phase gate for the cases n = 0, 1, 2, 3 in Fig. 4c. The results depict a substantial reduction in oscillations through Gaussian soft quantum control. Moreover, GP offers practical advantages over traditional SP in experimental scenarios7. Consequently, the combination of our approach with Gaussian soft control significantly enhances operational feasibility in experiments, showcasing promising and valuable applications.

Gate resilience

Subsequently, we delve into the robustness of the constructed C-Phase gates against parameter inaccuracies, with a particular focus on the impact of laser intensity on the fidelity of the C-Phase gate. To explore this scenario, we examine the effects of deviations in the Rabi frequency Ω, detuning Δ0, and gate time T, encompassing both upward and downward deviations. To quantify these deviations, we introduce the deviation value δΩ, δΔ0, and δT, yielding actual parameters

Then, we analyze the influence of errors on the entanglement fidelity of an equivalent Bell state \(\left\vert {\Psi }_{{{\rm{Bell}}}}\right\rangle =(\left\vert 00\right\rangle -i\left\vert 01\right\rangle -i\left\vert 10\right\rangle +\left\vert 11\right\rangle )/2\). The entanglement fidelity is defined by \({{\rm{tr}}}[\hat{\rho }(T)\left\vert {\Psi }_{{{\rm{Bell}}}}\right\rangle \left\langle {\Psi }_{{{\rm{Bell}}}}\right\vert ]\), where density operator \(\hat{\rho }(T)\) at the final moment is obtained by solving the master equation with an initial two-atom product state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle =(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle )\otimes (\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle )/2\) when employing either SP or GP for the laser configuration, as illustrated in Fig. 5a–c. We observe that the entanglement fidelity exhibits a comparable level of performance degradation when subjected to the same relative error in either pulse strength or detuning parameters, regardless of whether a SP pulse or GP is employed. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fundamental dependence of quantum evolution on the effective pulse area. Specifically, an equivalent relative error in the pulse strength parameter across both scenarios results in identical alterations to the effective pulse area. Consequently, precise control over pulse strength and detuning emerges as a critical requirement for achieving high-fidelity C-Phase gate operations within the present gate implementation scheme. Alternatively, it is noteworthy that the robustness of C-Phase gates against pulse strength errors can be significantly enhanced through optimal control methodologies. These techniques introduce additional degrees of freedom into the Rydberg system29,92,93,94, thereby potentially improving error tolerance. However, this enhanced robustness comes at the cost of increased implementation complexity, which may inadvertently introduce new sources of error into the system. Regarding the timing error in Fig. 5c, the entanglement fidelity demonstrates remarkable resilience when the GP is used. This robustness stems from the inherent property that moderate deviations in operation time do not significantly alter the pulse area. Only when the actual pulse duration falls substantially below the desired value, does the entanglement fidelity exhibit a marginal decrease. This behavior stands in stark contrast to the SP gate implementation, where the entanglement fidelity shows pronounced sensitivity to timing errors. Such sensitivity arises from the direct linear relationship between pulse duration errors and pulse area variations when the SP is used.

The impact of errors in the a Rabi frequency Ω, b detuning Δ0 and c gate time T on state fidelity is examined using square pulse and Gaussian pulse configurations. The relevant parameters remain consistent with V = ω0 = 2π × 70.18 MHz, Ω = 2π × 3.5 MHz, and the time-dependent Rabi frequency Ωg(t) as previously described. Each point denotes the average of 1001 results obtained by randomly picking 1001 disorders from [−Wk, Wk] with k = 1, 2, and 3 in (a), (b), and (c), respectively.

Regarding the error associated with the RRI strength V, our protocol faces a challenge similar to that of the conventional RAB gate schemes. Namely, the gate fidelity is sensitive to fluctuations in the RRI strength. In most Rydberg gate implementations, the atoms are assumed to be at fixed spatial positions, ensuring a constant RRI intensity. However, in practice, atoms exhibit finite temperature effects, and their residual thermal motion introduces positional uncertainty. As a result, precise control over the RRI strength becomes exceedingly difficult. We systematically investigate the impact of V variations on the entanglement fidelity, as illustrated in Fig. 6a, covering a relative error range δV/V ∈ [−0.2, 0.2]. The results indicate that the entanglement fidelity exhibits remarkable sensitivity to relative errors even when the absolute error range is limited in ~0.01 (see inset box). Additionally, we investigate the impact of modulation index α variation on the entanglement fidelity of our protocol. As shown in Fig. 6b, following a similar approach to equation (13), the actual parameter was derived through α → α(1 + W4) under both SP and GP conditions. The results indicate that while significant fluctuations in the value of α diminish the fidelity advantage, the feasibility of our protocol can be ensured when the actual implementation maintains precise control over α limited with the relative error <0.05.

a Schematic diagram illustrating the effect of Rydberg interaction strength V error on entanglement fidelity under square pulse and Gaussian pulse. b Diagram depicting the impact of modulation index α fluctuations on the robustness of our protocol, comparing square pulse and Gaussian pulse. c Impact of Doppler dephasing errors on entanglement fidelity at various temperatures for square pulse and Gaussian pulse. The associated parameters remain consistent with the aforementioned ones.

Furthermore, we simulate the dynamics of quantum systems with Doppler dephasing errors95,96. The Rydberg atom, regardless of its temperature, is not at rest in the trap. Doppler dephasing caused by the random motion of imprisoned atoms is one of the most important sources of error in experiments, which will limit the performance of quantum gates. Due to the presence of the Doppler effect, the Rydberg excitation Rabi frequency changes to Ω(t) → Ω(t)eiδt, where δ = keffΔv denotes the Doppler shift with effective laser wavevector keff and atomic root-mean-square speed \(\Delta v=\sqrt{{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{a}/m}\). In which kB, Ta, and m represent the Boltzmann constant, atomic temperature, and atomic mass, respectively. For the two-photon transition process of Rb atoms, we choose laser wavelengths of λ1 = 780 nm and λ2 = 480 nm, respectively. Moreover, we replace the orthogonal lasers with the counterpropagating lasers to reduce the effect of Doppler dephasing, thus obtaining keff = 2π(1/λ2 − 1/λ1). The numerical results of the fidelity of the C-Phase gate we constructed are shown in Fig. 6c, and it should be noted that the temperature simulated here is much higher than the current experimental conditions, where the temperature of the atoms in the optical tweezers can be cooled to 5.2 μK97. Even so, in the presence of a Doppler shift, the fidelity of the quantum gate can still reach more than 0.98 for cases of the SP and the GP. Besides, the usage of GP exhibits better performance in resilience against the Doppler dephasing, knowing from a smaller slope of the red entanglement fidelity line in Fig. 6c.

Finally, it is noted that the pronounced sensitivity to V variations suggests significant potential for applications in enhanced quantum metrology of external microwave fields (referring to ref. 98), despite the negative effect on quantum gates. Based on the implementation of Hamiltonian in Eq. (7), to perform criticality-enhanced precision measurement of microwave electric fields by exploiting the extreme sensitivity of doubly-excited state \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) population to deviations in RRI, the following approach can be executed. First, Ωa = Ωb = Ω is set to excite the ground state \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) into Rydberg state \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) through a two-atom Raman process with evolution duration π/Ω, enabling collective excitation in the RAB regime. Then the system is tuned near a non-equilibrium phase transition critical point by adjusting the probe laser detuning Δp and Rabi frequency Ωp, where quantum fluctuations diverge and the optical transmission exhibits a steep, population-dependent spectral edge. At criticality, the interplay between RRI-induced shifts of \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) and external microwave fields amplifies the sensitivity: Small microwave-induced Stark shifts Δmw perturb the critical detuning, causing significant changes in \(\left\vert rr\right\rangle\) population and transmission signals. The Fisher information, derived from the maximal slope of transmission spectra, quantifies the metrological gain, revealing a giant enhancement over single-atom systems due to critical two-atom RAB correlations. By continuously probing the transmission near the critical point and analyzing differential photon-counting signals, even very weak microwave field amplitudes can be resolved, leveraging the divergent susceptibility and nonlinear dynamics of the interacting Rydberg atoms.

Application in the Grover-Long algorithm

Finally, we consider to apply the proposed C-Phase gates in implementing the multi-item quantum search algorithm. According to the Grover-Long algorithm80,99, by replacing the phase inversion with phase rotation in oracle and diffusion operations, the desired target items can be searched with zero failure rate. The detailed circuit diagram is presented in Fig. 7a, together with the following steps.

(i) Starting with the initial state \(\frac{1}{2}(\left\vert 00\right\rangle +\left\vert 01\right\rangle +\left\vert 10\right\rangle +\left\vert 11\right\rangle )\), the oracle operator is applied to mark the target items. The utilization of one-item search \(\left\vert 11\right\rangle\) as a case study to elucidate the implementation procedure, the oracle operator is defined as U1 = \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle \left\langle 00\right\vert +\left\vert 01\right\rangle \left\langle 01\right\vert +\left\vert 10\right\rangle \left\langle 10\right\vert -\left\vert 11\right\rangle \left\langle 11\right\vert\), which is implemented by selecting ϑ = π/2 in C-Phase gate together with the single-qubit operator U = \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 0\right\vert +i\left\vert 1\right\rangle \left\langle 1\right\vert\) applied to both qubits. For the two-item target state \((\left\vert 01\right\rangle +\left\vert 10\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), the oracle operator is given by U1 = \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle \left\langle 00\right\vert +i\left\vert 01\right\rangle \left\langle 01\right\vert +i\left\vert 10\right\rangle \left\langle 10\right\vert +\left\vert 11\right\rangle \left\langle 11\right\vert\), which is realized by setting ϑ = −π/2 in C-Phase gate.

(ii) For the diffusion operator, the inverse Hadamard operation (H†) is initially applied to each qubit. The operator U2 is identical to U1 in the case of the one-item search. However, for the two-item search, U2 is defined as \(\left\vert 00\right\rangle \left\langle 00\right\vert +\left\vert 01\right\rangle \left\langle 01\right\vert +\left\vert 10\right\rangle \left\langle 10\right\vert +i\left\vert 11\right\rangle \left\langle 11\right\vert\), which is implemented by setting ϑ = −5π/4 in C-Phase gate together with the single qubit operation U = \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \left\langle 0\right\vert +{e}^{i\pi /4}\left\vert 1\right\rangle \left\langle 1\right\vert\) applied to each qubit. Finally, the Hadamard operation is applied to each qubit to complete the diffusion process.

Following these steps, the one-item and two-item searches are successfully implemented, with the dynamical processes are illustrated in Fig. 7b. The achieved fidelities of 0.9975 for the one-item search and 0.9879 for the two-item search underscore the effectiveness of our scheme. Notably, the proposed approach simplifies the circuit design and eliminates the need for individual addressing in two-qubit operations, thereby significantly improving the accuracy and efficiency of the quantum search algorithm.

Discussion

We have introduced a strategy to realize a C-Phase gate utilizing Rydberg atoms with FFM techniques. This approach is implemented through the Floquet periodic modulation of the atom-field detuning. This method leverages the synergistic effect between periodic modulation and RRI strength, providing a versatile platform for quantum system manipulation through parameter optimization. Notably, it effectively circumvents the conventional limitation where interaction strength is strictly governed by interatomic distance in Rydberg systems. This capability is particularly advantageous for the development of quantum logic gates. With respect to the most recent experimental parameters concerning the alkali metal rubidium atom, the C-Phase gates devised by our proposed approach exhibit outstanding performances. Furthermore, our method can be integrated with the Gaussian soft quantum control to enhance the fidelity and robustness of the C-Phase gate. Ultimately, our C-Phase gates holds promise for search algorithms with high success rates, thereby significantly enhancing the efficacy of multi-qubit operations without the necessity for laser independent addressing. We envision that combining FFM with advanced quantum control of Rydberg atoms will unlock new opportunities for achieving efficient and fault-tolerant quantum computation, enabling the realization of sophisticated quantum algorithms and the discovery of unprecedented quantum phenomena in precisely engineered coherent systems.

Methods

Floquet frequency modulation

Utilizing the FFM method, we implement periodic modulation of the atom-field detuning, selecting optimal modulation parameters to govern the quantum system dynamics towards achieving high-fidelity and robust quantum gates. Through a sequence of procedures including the system Hamiltonian picture transformation and Jacobi-Anger expansion, we derive the equivalent Rabi frequency dominated by Bessel functions. By manipulating the modulation index appropriately, we steer the system’s evolution to realize the targeted controlled-phase gates.

Under the modulation of Floquet method, the Hamiltonian of the system transforms into

where \({\hat{\sigma }}_{ab}=\left\vert a\right\rangle \left\langle b\right\vert\) and a, b ∈ {r, 1}. Besides, \({\hat{\sigma }}_{x}={\hat{\sigma }}_{r1}+{\hat{\sigma }}_{1r}\).

Soft quantum control

When SP are employed, the fidelity evolution exhibits pronounced oscillations. To mitigate this issue, we employ soft quantum control techniques to optimize the parameters and convert the SPs into GPs. This transformation aims to align more effectively with the requirements of RWA, thereby diminishing the impact of control errors and ultimately enhancing the gate performance.

The optimized time-evolving GP form is presented in Eq. (15)

where Ωg and Tg denote the maximum amplitude and width of GP, respectively.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Jaksch, D. et al. Fast quantum gates for neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2208–2211 (2000).

Gallagher, T. F. Rydberg atoms. In Cambridge Monographs on Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Saffman, M., Walker, T. G. & Mølmer, K. Quantum information with Rydberg atoms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2313–2363 (2010).

Béguin, L., Vernier, A., Chicireanu, R., Lahaye, T. & Browaeys, A. Direct measurement of the van der Waals interaction between two Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 263201 (2013).

Omran, A. et al. Generation and manipulation of schrödinger cat states in Rydberg atom arrays. Science 365, 570–574 (2019).

Levine, H. et al. Parallel implementation of high-fidelity multiqubit gates with neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 170503 (2019).

Evered, S. J. et al. High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 622, 268–272 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Early warning signals of the tipping point in strongly interacting Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 243601 (2024).

Anand, S. et al. A dual-species rydberg array. Nat. Phys. 20, 1744–1750 (2024).

Crescimanna, V., Taylor, J., Goldberg, A. Z. & Heshami, K. Quantum control of Rydberg atoms for mesoscopic quantum state and circuit preparation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 034019 (2023).

Jin, Z.-y & Jing, J. Geometric quantum gates via dark paths in Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 109, 012619 (2024).

Wu, C.-E., Kirova, T., Auzins, M. & Chen, Y.-H. Rydberg-rydberg interaction strengths and dipole blockade radii in the presence of förster resonances. Opt. Express 31, 37094–37104 (2023).

Liu, B. et al. Higher-order and fractional discrete time crystals in floquet-driven rydberg atoms. Nat. Commun. 15, 9730 (2024).

Lukin, M. D. et al. Dipole blockade and quantum information processing in mesoscopic atomic ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 037901 (2001).

Urban, E. et al. Observation of Rydberg blockade between two atoms. Nat. Phys. 5, 110–114 (2009).

Graham, T. M. et al. Rydberg-mediated entanglement in a two-dimensional neutral atom qubit array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 230501 (2019).

Fromonteil, C., Bluvstein, D. & Pichler, H. Protocols for Rydberg entangling gates featuring robustness against quasistatic errors. PRX Quantum 4, 020335 (2023).

Buchemmavari, V., Omanakuttan, S., Jau, Y.-Y. & Deutsch, I. Entangling quantum logic gates in neutral atoms via the microwave-driven spin-flip blockade. Phys. Rev. A 109, 012615 (2024).

Sun, Y. Buffer-atom-mediated quantum logic gates with off-resonant modulated driving. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 120311 (2024).

Chen, Z.-Y. et al. Single-pulse two-qubit gates for Rydberg atoms with noncyclic geometric control. Phys. Rev. A 109, 042621 (2024).

Isenhower, L. et al. Demonstration of a neutral atom-controlled-not quantum gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 010503 (2010).

Su, S.-L. et al. Rabi- and blockade-error-resilient all-geometric Rydberg quantum gates. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 044007 (2023).

Møller, D., Madsen, L. B. & Mølmer, K. Quantum gates and multiparticle entanglement by Rydberg excitation blockade and adiabatic passage. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 170504 (2008).

Liu, B.-J., Su, S.-L. & Yung, M.-H. Nonadiabatic noncyclic geometric quantum computation in Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043130 (2020).

Xue, M., Xu, S., Li, X. & Li, X. High-fidelity and robust controlled-Z gates implemented with Rydberg atoms via echoing rapid adiabatic passage. Phys. Rev. A 110, 032619 (2024).

Guo, F.-Q. et al. Complete and nondestructive distinguishment of many-body Rydberg entanglement via robust geometric quantum operations. Phys. Rev. A 102, 062410 (2020).

Mitra, A., Omanakuttan, S., Martin, M. J., Biedermann, G. W. & Deutsch, I. H. Neutral-atom entanglement using adiabatic Rydberg dressing. Phys. Rev. A 107, 062609 (2023).

Jandura, S., Thompson, J. D. & Pupillo, G. Optimizing Rydberg gates for logical-qubit performance. PRX Quantum 4, 020336 (2023).

Song, P.-Y. et al. Fast realization of high-fidelity nonadiabatic holonomic quantum gates with a time-optimal-control technique in Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 109, 022613 (2024).

Cao, A. et al. Multi-qubit gates and schrödinger cat states in an optical clock. Nature 634, 315–320 (2024).

Jia, Z. et al. An architecture for two-qubit encoding in neutral ytterbium-171 atoms. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 106 (2024).

Unnikrishnan, G. et al. Coherent control of the fine-structure qubit in a single alkaline-earth atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 150606 (2024).

Stiesdal, N. et al. Observation of three-body correlations for photons coupled to a Rydberg superatom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 103601 (2018).

Zeiher, J. et al. Microscopic characterization of scalable coherent Rydberg superatoms. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031015 (2015).

Shao, X.-Q. et al. Rydberg superatoms: an artificial quantum system for quantum information processing and quantum optics. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11, 031320 (2024).

Ates, C., Pohl, T., Pattard, T. & Rost, J. M. Antiblockade in Rydberg excitation of an ultracold lattice gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 023002 (2007).

Rao, D. D. B. & Mølmer, K. Dark entangled steady states of interacting Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 033606 (2013).

Carr, A. W. & Saffman, M. Preparation of entangled and antiferromagnetic states by dissipative Rydberg pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 033607 (2013).

Amthor, T., Giese, C., Hofmann, C. S. & Weidemüller, M. Evidence of antiblockade in an ultracold Rydberg gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 013001 (2010).

Liu, F., Yang, Z.-C., Bienias, P., Iadecola, T. & Gorshkov, A. V. Localization and criticality in antiblockaded two-dimensional Rydberg atom arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 013603 (2022).

Kitson, P., Haug, T., La Magna, A., Morsch, O. & Amico, L. Rydberg atomtronic devices. Phys. Rev. A 110, 043304 (2024).

Li, W.-X., Wu, J.-L., Su, S.-L. & Qian, J. High-tolerance antiblockade SWAP gates using optimal pulse drivings. Phys. Rev. A 109, 012608 (2024).

Jo, H., Song, Y., Kim, M. & Ahn, J. Rydberg atom entanglements in the weak coupling regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 033603 (2020).

Wu, J.-L. et al. Effective Rabi dynamics of Rydberg atoms and robust high-fidelity quantum gates with a resonant amplitude-modulation field. Opt. Lett. 45, 1200–1203 (2020).

Wu, J.-L. et al. Resilient quantum gates on periodically driven Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 103, 012601 (2021).

Shao, X.-Q., Wu, J.-H. & Yi, X.-X. Dissipative stabilization of quantum-feedback-based multipartite entanglement with Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 95, 022317 (2017).

Li, D. X. & Shao, X. Q. Unconventional Rydberg pumping and applications in quantum information processing. Phys. Rev. A 98, 062338 (2018).

Shao, X.-Q. Selective Rydberg pumping via strong dipole blockade. Phys. Rev. A 102, 053118 (2020).

Eckardt, A. Colloquium: atomic quantum gases in periodically driven optical lattices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 011004 (2017).

Basak, S., Chougale, Y. & Nath, R. Periodically driven array of single Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 123204 (2018).

Mallavarapu, S. K., Niranjan, A., Li, W., Wüster, S. & Nath, R. Population trapping in a pair of periodically driven Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 103, 023335 (2021).

Nguyen, L. B. et al. Programmable Heisenberg interactions between Floquet qubits. Nat. Phys. 20, 240–246 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. Cavity Floquet engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 7782 (2024).

Zhao, L., Lee, M. D. K., Aliyu, M. M. & Loh, H. Floquet-tailored Rydberg interactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 7128 (2023).

Heya, K., Malekakhlagh, M., Merkel, S., Kanazawa, N. & Pritchett, E. Floquet analysis of frequency collisions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 024035 (2024).

Sun, H.-W., Wu, J.-L. & Su, S.-L. Floquet geometric entangling gates in ground-state manifolds of Rydberg atoms. Phys. Scr. 99, 085122 (2024).

Liu, B.-J., Song, X.-K., Xue, Z.-Y., Wang, X. & Yung, M.-H. Plug-and-play approach to nonadiabatic geometric quantum gates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 100501 (2019).

Li, H., Liu, Y. & Long, G. Experimental realization of single-shot nonadiabatic holonomic gates in nuclear spins. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 60, 080311 (2017).

Ma, S. et al. High-fidelity gates and mid-circuit erasure conversion in an atomic qubit. Nature 622, 279–284 (2023).

Song, X.-K., Zhang, H., Ai, Q., Qiu, J. & Deng, F.-G. Shortcuts to adiabatic holonomic quantum computation in decoherence-free subspace with transitionless quantum driving algorithm. New J. Phys. 18, 023001 (2016).

Zhang, S.-Y. et al. Quantum computation based on capture-and-release dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 111, 012604 (2025).

Wu, J.-L., Song, J. & Su, S.-L. Resonant-interaction-induced Rydberg antiblockade and its applications. Phys. Lett. A 384, 126039 (2020).

Su, S.-L. et al. One-step implementation of the Rydberg-Rydberg interaction gate. Phys. Rev. A 93, 012306 (2016).

Su, S.-L. et al. Applications of the modified Rydberg antiblockade regime with simultaneous driving. Phys. Rev. A 96, 042335 (2017).

Xing, T. H., Wu, X. & Xu, G. F. Nonadiabatic holonomic three-qubit controlled gates realized by one-shot implementation. Phys. Rev. A 101, 012306 (2020).

Liang, Y., Shen, P., Chen, T. & Xue, Z.-Y. Composite short-path nonadiabatic holonomic quantum gates. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 034015 (2022).

Haase, J. F., Wang, Z.-Y., Casanova, J. & Plenio, M. B. Soft quantum control for highly selective interactions among joint quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 050402 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Unidirectional acoustic metamaterials based on nonadiabatic holonomic quantum transformations. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 65, 220311 (2021).

Yin, H.-D. & Shao, X.-Q. Gaussian soft control-based quantum fan-out gate in ground-state manifolds of neutral atoms. Opt. Lett. 46, 2541–2544 (2021).

Song, X.-K., Ai, Q., Qiu, J. & Deng, F.-G. Physically feasible three-level transitionless quantum driving with multiple schrödinger dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 93, 052324 (2016).

Wu, J.-L. et al. Two-path interference for enantiomer-selective state transfer of chiral molecules. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 044021 (2020).

Han, J.-X. et al. Large-scale Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger states through a topologically protected zero-energy mode in a superconducting qutrit-resonator chain. Phys. Rev. A 103, 032402 (2021).

Wu, Q., Xing, J. & Yin, H. Soft-controlled quantum gate with enhanced robustness and undegraded dynamics in Rydberg atoms. EPJ Quantum Technol. 11, 1 (2024).

Guo, J.-K., Wu, J.-L., Cao, J., Zhang, S. & Su, S.-L. Shortcut engineering for accelerating topological quantum state transfers in optomechanical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 110, 043510 (2024).

Guo, F. Q., Su, S.-L., Li, W. & Shao, X. Q. Parity-controlled gate in a two-dimensional neutral-atom array. Phys. Rev. A 111, 022420 (2025).

Grover, L. K. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 325–328 (1997).

Grover, L. K. Quantum computers can search rapidly by using almost any transformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4329–4332 (1998).

Long, G.-L. Grover algorithm with zero theoretical failure rate. Phys. Rev. A 64, 022307 (2001).

Long, G.-L., Li, Y.-S., Zhang, W.-L. & Niu, L. Phase matching in quantum searching. Phys. Lett. A 262, 27–34 (1999).

Long, G.-L., Li, X. & Sun, Y. Phase matching condition for quantum search with a generalized initial state. Phys. Lett. A 294, 143–152 (2002).

He, X. et al. Experimental demonstration of deterministic quantum search for multiple marked states without adjusting the oracle. Opt. Lett. 48, 4428–4431 (2023).

Sankar, K. et al. A benchmarking study of quantum algorithms for combinatorial optimization. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 64 (2024).

Li, Z.-H. et al. Experimental demonstration of deterministic quantum search algorithms on a programmable silicon photonic chip. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 66, 290311 (2023).

Li, X., Shen, H., Gao, W. & Li, Y. Resource efficient Boolean function solver on quantum computer. Quantum 8, 1500 (2024).

Pokharel, B. & Lidar, D. A. Better-than-classical Grover search via quantum error detection and suppression. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 23 (2024).

Borish, V., Marković, O., Hines, J. A., Rajagopal, S. V. & Schleier-Smith, M. Transverse-field Ising dynamics in a Rydberg-dressed atomic gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 063601 (2020).

Geier, S. et al. Floquet Hamiltonian engineering of an isolated many-body spin system. Science 374, 1149–1152 (2021).

Levine, H. et al. High-fidelity control and entanglement of Rydberg-atom qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 123603 (2018).

Wilk, T. et al. Entanglement of two individual neutral atoms using Rydberg blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 010502 (2010).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579–584 (2017).

Nielsen, M. A. A simple formula for the average gate fidelity of a quantum dynamical operation. Phys. Lett. A 303, 249–252 (2002).

Yun, M.-R. et al. Quantum computation in silicon-vacancy centers based on nonadiabatic geometric gates protected by dynamical decoupling. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 064053 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Multiple-qubit controlled unitary quantum gate for Rydberg atoms using shortcut to adiabaticity and optimized geometric quantum operations. Phys. Rev. A 103, 062607 (2021).

Yun, M.-R. et al. Parallel-path implementation of nonadiabatic geometric quantum gates in a decoherence-free subspace with nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. A 105, 012611 (2022).

ŠibaliĆ, N., Pritchard, J., Adams, C. & Weatherill, K. Arc: an open-source library for calculating properties of alkali Rydberg atoms. Comput. Phys. Commun. 220, 319–331 (2017).

Shi, X.-F. Suppressing motional dephasing of ground-rydberg transition for high-fidelity quantum control with neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 024008 (2020).

Lee, W., Kim, M., Jo, H., Song, Y. & Ahn, J. Coherent and dissipative dynamics of entangled few-body systems of Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 99, 043404 (2019).

Ding, D.-S. et al. Enhanced metrology at the critical point of a many-body Rydberg atomic system. Nat. Phys. 18, 1447–1452 (2022).

Liu, B.-B. et al. Robust three-qubit search algorithm in Rydberg atoms via geometric control. Phys. Rev. A 106, 052610 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12304407, 12274376, 62471001, 12475009, 12075001, and 12175001), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology under Grant No. 258 2021ZD0301704, the Major Science and Technology project of Henan Province under Grant No. 221100210400, the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province under Grant No. 232300421075, Natural Science Research Project in Universities of Anhui Province (Grant No. 2024AH050068), Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Plan (Grant No. 2022b13020004), Anhui Province Science and Technology Innovation Project (Grant No. 202423r06050004), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grants No. 2023TQ0310, GZC20232446, and 2024M762973).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. made the calculations and carried out numerical simulations of the system. J.W., F.-Q.G., and B.-B.L. contributed to the implementation of the Gaussian soft quantum control method and the circuit of the quantum search algorithm. J.W. wrote the manuscript and J.-L.W., S.-L.S., and X.-K.S. edited the manuscript. J.-L.W., S.-L.S., X.-K.S., L.Y., and D.W. provided supervision and guidance during the project. All authors contributed to the discussions and interpretations of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Wu, JL., Guo, FQ. et al. Quantum computation via Floquet tailored Rydberg interactions. npj Quantum Inf 11, 118 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01068-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01068-z