Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating lung disease with limited treatment options, partly due to a lack of effective disease models. This study presents a ferret model of pulmonary fibrosis (PF) induced by bleomycin, which replicates key characteristics of human IPF. The ferret model demonstrates an irreversible loss of pulmonary compliance, increased opacification, and structures resembling honeycomb cysts. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing, we observed a significant shift in the distal lung epithelium toward a proximal phenotype. Cell trajectory analysis showed that AT2 cells transition into KRT8high/KRT7low/SOX4+ cells, and eventually into KRT8high/KRT7high/SFN+/TP63+/KRT5low “basaloid-like” cells. These cells, along with KRT7 and KRT8 populations, are located over myofibroblasts in fibrotic areas, suggesting a role in fibrosis progression similar to that in human IPF. This model accurately reproduces the pathophysiological and molecular features of human IPF, making it a valuable tool for future research and therapeutic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive pulmonary disease characterized by fibrotic lesions, with excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) and destruction of the lung architecture, which ultimately leads to decline of pulmonary function and respiratory failure with limited therapeutic options1,2. The lack of clinically relevant and highly predictive models has greatly impeded our understanding of IPF pathogenesis, and consequently, the development of new treatments for IPF3.

Although bleomycin-induced fibrosis in rodents share certain features of human IPF, most have failed to recapitulate the complex pathobiology, in particular the bronchiolization of distal alveoli and formation of honeycomb cyst-like structures that chronically persist. In general, lung fibrosis in rodents exhibits predominantly reversible features with self-limiting disease4,5. However, recent studies indicate that aged mice with multiple doses of bleomycin injury may exhibit progressive and chronic fibrosis6,7. Bleomycin-injured large animals such as canines8, sheep9,10, pig11, and non-human primates (NHPs)12 tend to recapitulate most manifestations of human IPF, however, the need for biosafety containment, widespread inaccessibility of transgenic lines, and costs of these models can be challenging.

Domestic ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) have been recognized as excellent models for medical research on a variety of respiratory diseases owing to similarities of airway anatomy, lung cell biology, and physiology between ferrets and humans13. These diseases include influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infections14,15, smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)16, obliterative bronchiolitis (OB)17,18,19, emphysema caused by alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency20, cystic fibrosis (CF)21,22,23, and acute lung injury followed by pulmonary fibrosis (PF)24,25,26. Each of these ferret models demonstrates potential to inform disease mechanisms that are similar to those in humans. Recent advances in ferret genetic engineering have made it possible to create sophisticated conditional transgenic ferrets with multiple transgenes, allowing for both fate mapping and gene manipulation27,28. These capabilities position ferrets as a valuable alternative species for investigating complex mechanistic questions in disease models.

Here we report a comprehensive evaluation of the histopathology, pulmonary function, and radiographic phenotypes, as well as cellular and molecular features, of a bleomycin-induced ferret model of PF. Our findings reveal that this bleomycin-induced ferret model exhibits key features of human IPF, suggesting it could serve as a reliable model for investigating the underlying mechanisms of IPF and accelerating the development of effective therapies.

Results

Bleomycin induces histopathologic and biochemical features resembling human IPF in ferret lungs

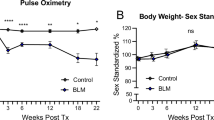

Following three doses of bleomycin injury, a gradual loss of body weight was observed in both male and female ferrets with most animals reaching a humane endpoint before 12 weeks post bleomycin challenge (Fig. 1A–C). By 4 weeks post bleomycin challenge, lung histopathology revealed a patchy distribution of fibrotic foci and honeycomb cyst-like structures (Fig. 1D) with significant collagen deposition (Fig. 1E, F). Consistent with our histomorphometric findings, the hydroxyproline (HYP) content was significantly higher in the plasma and lungs of bleomycin ferrets after the challenge than in age- and sex-matched controls (Supplementary Fig. S1A–C). Plasma HYP content was also significantly higher in older bleomycin-injured ferrets than that in their younger counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S1D), while no differences were detected between males and females (Supplementary Fig. S1E). In agreement with the histopathological changes and increased matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and collagen content (Supplementary Fig. S1F, G), the Ashcroft scores were significantly higher in bleomycin ferrets compared to controls (Fig. 1G, J). No significant decrease in the Ashcroft scores were observed beyond the 4-week timepoint, but the loss of some ferrets to clinical endpoints led to a downward trend due to drop-out of the most severely diseased animals (Fig. 1G). Notably, older ferrets (≥11 months old) were more sensitive to bleomycin injury (i.e., had higher Ashcroft scores) than younger ferrets (≤10 months) (p = 0.0030, N = 7), but there were no differences between male and female ferrets (Fig. 1H, I). This age-related observation regarding PF is consistent with the incidence and prevalence of IPF in human populations29,30 and bleomycin-based models of IPF in other species4,6,7,31.

A Schema representing the experimental timelines for bleomycin-induced PF in ferrets. Ferrets received 3 bleomycin (BLM) doses intratracheally at 1-week intervals (purple arrows), and lung tissues were harvested and analyzed at 4, 8, or 12 weeks (red arrows) after the first bleomycin challenge. Healthy age- and sex-matched ferrets treated with saline served as controls. B Curves of changes in body weight for male and female ferrets up to 13 weeks after the first bleomycin exposure. Data represents the mean ± SEM. C Kaplan–Meier survival curve for male and female ferrets up to 14 weeks after the first bleomycin exposure. D Representative images of H&E-stained lungs from control and bleomycin-challenged ferrets at the indicated timepoints. E Representative images of Masson’s trichrome stained lungs (for collagen deposition) from control and bleomycin-challenged ferrets at the indicated timepoints. Images in right panels of D and E are enlargements of boxed areas in the images at left. F Quantification of % collagen area as determined from Masson’s trichrome-stained images from control and bleomycin-injured ferrets at the indicated timepoints. G Ashcroft scores in bleomycin-challenged ferrets at 4, 8 and 10+ weeks. H Ashcroft scores in ferrets ≤10 months and ≥11 months old, following challenge with bleomycin (P = 0.0030, N = 7). I Ashcroft scores in male vs. female ferrets challenged with bleomycin (P = 0.139, N = 5). J Collagen deposition as a function of Ashcroft score in lungs from ferrets challenged with bleomycin, as determined by analysis of the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) (r = 0.85, P < 0.0001, N = 20). Data in F–I represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s comparison test, with (N) denoted in the graph. Data for individual ferrets are represented by dots. Scale bars in D and E equal 2 mm (left panels) or 100 μm (right panels).

In addition to the histopathological similarity between the bleomycin-challenged ferret and human IPF phenotype, biochemical and molecular analyses revealed that the profile of circulatory biomarkers in bleomycin ferrets is similar to that in people with IPF. Specifically, we found the protein levels for known human IPF biomarkers (KL-6, SFTPA, SFTPD, MUC5AC, MUC5B, MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-7) were significantly higher in the plasma of bleomycin-challenged ferrets compared with saline controls (Supplementary Fig. S2); the one exception was S100A12. Of note, the highly-studied epithelial-specific circulatory biomarker KL-6, which is used to distinguish between IPF and other common forms of interstitial lung disease (ILD)32,33, was more abundant in the plasma of older bleomycin ferrets than their younger counterparts without gender differences (Supplementary Fig. S3A,B). The expression of SFTPA was also slightly higher in bleomycin ferret lungs related to control, as determined by immunostaining and immunoblotting assays (Supplementary Fig. S3C–E).

Radiographic and pulmonary function assays reveal clinical manifestations of fibrosis in bleomycin-injured ferret lungs

Consistent with the histopathological findings, CT lung imaging showed diffuse homogeneous areas of increased lung opacification. The high attenuation area (HAA) was greater in the right vs. left lung (Supplementary Fig. S4A–C), likely due to uneven distribution of bleomycin during intratracheal delivery (Fig. 2A–C, Supplementary Fig. S4D,E). Consistently, pulmonary function testing (PFT) showed that the inspiratory capacity (IC) was significantly lower in both male and female ferrets at 4 weeks post bleomycin challenge as compared to baseline (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Fig. S5A,B). Using FEV0.4 as a ferret equivalent to human FEV120, we observed an restrictive pulmonary phenotype in males that was significant with an increased FEV0.4/FVC (Fig. 2E). Other PFT metrics, including quasi-static compliance (ml/cmH2O) (Cst) (Supplementary Fig. S5C) and dynamic compliance of the respiratory system (Crs, ml/cmH2O) (Supplementary Fig. S5D), were significantly decreased in ferrets at 4 weeks post bleomycin challenge. Elastance of the respiratory system (Ers, cmH2O/ml) (Supplementary Fig. S5E) and resistance (Rrs) (Supplementary Fig. S5F) were moderately increased. The decrease in Cst confirms that lung compliance in bleomycin ferret lungs is reduced (Supplementary Fig. S5C). Consistent with the more advanced fibrosis observed in male bleomycin ferrets, these animals demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in IC than their female counterparts (Fig. 2F), whereas the increase of FEV0.4/FVC ratio was not significantly different between sexes (Fig. 2G). In addition, there was no significant difference in IC (Supplementary Fig. S5G) and FEV0.4/FVC ratio (Supplementary Fig. 5H) between younger (≤10 months) and older (≥11 months) ferrets (Supplementary Fig. S5G). Notably, the decline in lung function was strongly associated with the degree of pathohistological change in the lungs of bleomycin-induced ferrets, as suggested by the correlation between the change in IC (∆IC) and PF as measured by the Ashcroft scores (r = –0.8486; 95% CI, –0.9485 to –0,5950, p < 0.0001, n = 15) (Fig. 2H). Also, the decrease of IC (Fig. 2I) and increase of FEV0.4/FVC ratio (Fig. 2J) did not recover to baseline levels by 12 weeks, indicating a sustained decline in respiratory function in these ferrets.

A Schema showing the timing of pulmonary function test (PFT) and computerized tomography (CT) in ferrets. PFT or CT was performed at one week (-1 week) before and at the 4, 8, and/or 10 weeks timepoints. B Representative 2D images (x view, upper panels; y view, lower panels) of a ferret at the indicated timepoints. C Quantification of radiographic opacity in lung, as determined by the percentage of high-attenuation areas (HAA) in whole lung and in the separated left and right lungs. Bleomycin-induced changes in inspiratory capacity (IC, mL at 30 cmH2O) (D) and FEV0.4/FVC ratio (E) at 4 weeks in 10 animals (5 males and 5 females) in which PFT was examined at one week before and 4 weeks after the bleomycin challenge. Differences in IC (F) and FEV0.4/FVC ratio (G) by sex. H Correlation between IC (∆IC) and Ashcroft score as determined by analysis of Pearson correlation coefficient (r) (r = –0.8486, P < 0.0001, N = 15). I, J Differences in IC and FEV0.4/FVC ratio in control vs. bleomycin-challenged ferrets analyzed through 12 weeks (control N = 3, bleomycin N = 4): Data were analyzed in sex-mixed group and sex-specific differences are indicated in figure labels for D–H. Unpaired t test with the number of samples (control N = 3, bleomycin N = 4) of samples denoted in the graph for I and J.

We next evaluated age-dependent impaired pulmonary function longitudinally in a subset of bleomycin-injured ferrets, with more moderate disease progression that did not reach the humane terminal endpoint prior to study completion. In four ferrets that were challenged with bleomycin at the ages of 3–11 months, the pressure-volume (PV) loop at the last experimental timepoint was shifted downward at 4 weeks post bleomycin challenge, and it gradually shifted upward in three younger animals (3–8 months) at 6–9 weeks post bleomycin challenge (Supplementary Fig. S5I–K). In the fourth ferret (11-months-old at the first bleomycin exposure), the PV loop was stable at 6- and 11-weeks post bleomycin challenge, and this animal met the humane terminal endpoint prior to 12-weeks (Supplementary Fig. S5L). It is worth noting that in all four of the longitudinally monitored bleomycin-injured animals, the PV loop did not recover to the initial baseline level (Supplementary Fig. S5I–L). Decline in pulmonary function in these bleomycin-induced IPF ferrets was further corroborated by the histopathological changes in lungs (Supplementary Fig. S5I’–L’), and other PFT parameters, including IC, Rrs, FEV0.4/FVC, Crs, Ers, and Cst (Supplementary Fig. S5M). These data suggest that impaired pulmonary function is persistent in bleomycin-induced ferrets up to 12 weeks, but that younger animals may have a greater capacity to recover from injury.

Emergence of diverse aberrant epithelial cell phenotypes reminiscent of human IPF in bleomycin-injured ferret lungs

To gain insight into cell-specific alterations in bleomycin-induced ferret lungs, we performed single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-Seq) analysis (Fig. 3A). We profiled 114,125 cells from the distal lungs of 9 ferrets. Among these, 66,864 cells were obtained from 5 bleomycin-injured ferrets with Ashcroft scores of 4 or above, and 47,261 were obtained from 4 saline controls (Fig. 3A). Following the removal of batch effects across samples, all major cell types were annotated using human lung cell atlas (HCLA) reference annotations: epithelial, mesenchymal, endothelial, and immune cells (Fig. 3B)34,35,36. We identified 33 discrete cell clusters based on the presence of distinct marker sets (Fig. 3C, D). The unique expression profiles of signature genes in each main cell type were used for supervised clustering (Fig. 3E, F and Supplementary Fig. S6A,B). In addition to the homeostatic cell types, we also identified disease-specific cell clusters for epithelial (Fig. 4A, B), mesenchymal (Fig. 7A, B), and immune cell types (Supplementary Fig. S6C–F).

A Schema showing workflow for generating and analyzing lung snRNA-Seq data (created with BioRender’s icons). B UMAP of major cell classes (epithelial, endothelial, mesenchymal, and immune) captured in snRNA-seq analysis. C UMAP of all cells profiled; the 33 clustered cell types were annotated using human cell reference annotations from the HCLA. D UMAP showing the distribution of cell-types in bleomycin-injured (blue) and saline-treated (orange) ferret lungs. Heatmap of marker genes used for classifying epithelial (E) and mesenchymal (F) cell types. Each cell type is represented by the top 5 genes ranked by Wilcoxon rank sum test for each cell type against the other cell types.

A UMAP of snRNA-Seq visualizing 10 subclusters of epithelial cells in both BLM- and saline-treated ferret lungs. B UMAP of snRNA-Seq visualizing differences between epithelial cell-types in bleomycin- and saline-treated ferret lungs. C Dot plot showing frequency of markers of cell types and transitional cell states. D UMAPs visualizing the distribution of expression of the SFTPC, AGER, MUC5B, SCGB1A1, and SCGB3A2 genes. E Bar plots showing the proportion of each epithelial-cell subtype enriched in bleomycin- and saline-treated lungs. F (Top panels) Representative immunofluorescence (IF) images showing cells that co-express the SPC (green) and SCGB1A1 (white) proteins and their proximity to ACTA2 (red)-expressing myofibroblasts. Expression of SPC (green) (Bottom panels) and SCGB3A2 (megenta) (bottom panels) proteins in fibrotic lesions. Insets indicate enlarged region and individual channels for regions marked by yellow dashed line box. DAPI-nuclei (blue). G Representative IF images of MUC5B- and Ki67-stained (Top panels), and bleomycin-induced fibrotic regions co-staining for MUC5B and SCGB3A2 (Botton panel). H Representative IF images of saline- and bleomycin-treated tissue showing cells co-expressing SCGB3A2 (magenta) and SCGB1A1 (green). Insets indicate enlarged region and individual channels of regions marked by yellow dashed box. DAPI-nuclei (blue). Scale bars equal 100 µm (main images), 50 µm in enlarged image in (F), and 20 µm in enlarged images in (H).

We next performed more focused analyses of epithelial cell changes in bleomycin-injured lungs and compared them to control counterparts. We identified 10 distinct cell types/states, encompassing typical epithelial cell types (e.g., AT1, AT2, basal, goblet, ciliated, and club), and epithelial cell states identified in human IPF lungs and rodent models (e.g., transitional AT2 cells), that express their unique marker genes in both bleomycin- and saline-treated ferret lungs (Fig. 4A–C). UMAP plots showed cell-type-specific marker genes SFTPC (AT2), AGER (AT1), MUC5B (goblet cells in proximal airway and submucosal glands), SCGB1A1 (club cells), and SCGB3A2 (secretory cells) in corresponding epithelial subclusters (Fig. 4D).

Analysis of differences in relative proportion of epithelial cell composition revealed a decrease in the number of AT1 (51.41% in saline vs. 48.59% in bleomycin) and AT2 (55.43% in saline vs. 44.57% in bleomycin) cells, and dramatic increases in the number of transitional AT2 cells (6.8% in saline vs. 93.2% in bleomycin) and KRT7+ cells (0.49% in saline vs. 99.51% in bleomycin) (Fig. 4E). The relative proportions of club (38.3% in saline vs. 61.7% in bleomycin), basal (23.25% in saline vs. 76.75% in bleomycin), goblet (37.12% in saline vs. 62.88% in bleomycin), and ciliated (44.61% in saline vs. 55.39% in bleomycin) cells were higher in the bleomycin compared to control lungs, indicating the “proximalization” of distal lung epithelium in ferret lung fibrosis (Fig. 4E). Corroborating the snRNA-seq data, immunofluorescence staining (IF) showed that the numbers of SCGB1A1 and SCGB3A2 expressing cells were significantly increased in fibrotic lungs of ferrets (Fig. 4F). Notably, in bleomycin ferret lungs a subset of SCGB1A1+ and SCGB3A2+ cells also expressed the AT2 cell marker SFTPC (SPC) (Fig. 4F), indicating that these putative transitional AT2 cells were phenotypically similar to previously described terminal and respiratory bronchiole (TRB)-specific AT0 cells12, or respiratory airway secretory (RAS) cells37. Further, we found SCGB1A1+SCGB3A2+ double-positive cells in “bronchiolized” regions (Fig. 4H), which are phenotypically similar to human TRB secretory cells (TRB-SCs) in both human IPF and bleomycin-injured primate lungs12. Note that these cells did not separately cluster in our single-cell analysis, presumably because they are few in number and share many of markers with AT2 and airway club/secretory cells. Collectively, single-cell and in situ validation data suggest that the lung fibrosis phenotype in ferrets emulates the AT0/RAS and TRB-SC dynamics that are observed in human IPF and non-human primates (NHP) fibrosis models37.

Genetic studies have demonstrated that MUC5B variants are strongly associated with the development of IPF and are considered an important risk factor38,39,40. Consistent with other scRNA-Seq analyses of human lungs34,35,41,42, we observed a significant increase in the MUC5B+ cell population in fibrotic lungs in ferret compared to controls (Fig. 4G). Further, IF staining revealed the presence of these cells in “honeycomb-like cyst” (Fig. 4G)25. The MUC5B+ cells were not proliferative, as evidenced by negative staining for the marker Ki67. However, most of the MUC5B+ cells also expressed SCGB3A2 in distal lung regions (Fig. 4G), consistent with the findings that a MUC5B risk variant promotes muco-secretory cell differentiation in IPF40.

Bleomycin induces bronchiolization of distal lung parenchyma in ferret lungs

Bronchiolization is a hallmark of the human IPF lung. It is characterized by ectopic aberrant basaloid epithelial cells and honeycomb cystic structures in the airspace of distal lung34,36. Our snRNA-seq analysis showed an increase in the proportion of basal cells and their markers in fibrotic ferret lungs (Figs. 4E, and 5A). IF analysis for basal cell markers KRT17, TP63 and KRT5 further revealed a subpopulation phenotypically similar to basaloid cells (KRT17+/TP63+/KRT5low) within “bronchiolization-like” structures in the periphery of bleomycin ferret lung but not in the control ferret lung (Fig. 5B–D,D’). The KRT17 gene is not annotated in the ferret genome and thus the analogous cell could not be interrogated at the single cell level, however, we used KRT7 as a surrogate marker for the presence of aberrant “basaloid-like” cells in bronchiolized regions and within the single cell dataset. Notably, the expression of KRT7 was observed in AT1 and AT2 cells of the alveolar space of bleomycin ferret lung but not that of the control lung (Supplementary Fig. S7A,B). Similar to the KRT17+/TP63+/KRT5low population, a subset of TP63+ cells were also KRT7+/KRT5low and similarly observed in the periphery of the bleomycin-treated lungs (Fig. 5E–G,G’). Further, the KRT7+ cells overlapped with the expression of KRT8, and subset of KRT7+/KRT8+ cuboidal cells express TP63 (Fig. 5H, I, I’). Similar to the observed KRT7+/TP63+/KRT5low cells, we also found rare KRT8+/TP63+/KRT5low cells and KRT7+/KRT17+/TP63+ cells (Supplementary Fig. S8) in fibrotic regions of bleomycin-injured ferret lungs. Taken together, these results suggest that KRT17+/TP63+/KRT5low, KRT7+/TP63+/KRT5low, and KRT8+/TP63+/KRT5low cells of bleomycin-injured ferret lungs share features of basaloid cells observed in human IPF34,35. Thus, these cells may contribute to the “bronchiolization-like” pattern observed in bleomycin-treated ferret lungs.

A Heatmap showing the expression of epithelial-cell markers of proximal airways, TP63, KRT7, KRT5 and KRT8 in ferret distal lungs. Representative IF images of co-staining of KRT5 (white), KRT17 (green), and TP63 (red) in distal lung of control (B) and bleomycin (C) ferrets. D Inset from (C), showing bronchiolar morphology with KRT17 (green), KRT5 (white), and/or TP63 (red) -positive epithelial cells. D’ Enlarged image of boxed area in panel (D). Double-channel images in right panels of D’ showing cells that are positive for KRT17 and TP63 (red) but negative or low for KRT5 (white) (basaloid cells; arrows). Representative IF images of co-staining of KRT5, KRT7, and TP63 in control (E) and bleomycin (F) ferret distal lungs. G Enlargement of boxed area in (F), showing bronchiolar morphology with KRT7, KRT5 and/or TP63-positive epithelial cells. G’ Enlargement of boxed area in (G). Double-channel images in right panels of (G’), showing cells that are positive for KRT7 and TP63 but negative or low for KRT5 (basaloid cells, arrows). H, I Representative IF images of co-staining of KRT7, KRT8, TP63 in distal lungs of bleomycin ferrets, showing aberrant KRT7 and KRT8 basaloid cells. (I) Enlargement of boxed area in (H), showing bronchiolar epithelium with KRT7, KRT8, and/or TP63-positive cells. I’ Enlargement of boxed area in (I). Double channel images in right panels of I’ showing KRT7/KRT8/TP63 triple-positive cells (arrows). Scale bars in B, E equal 100 μm; in C, F, H equal 200 μm; in D, G, I are equal 50 µm; in D’, G’, I’ equal 20 µm.

To investigate the relationship between the KRT17- and KRT7-expressing basaloid-like cells (TP63+/KRT5low), we performed co-immunolocalization of KRT5, KRT7 and KRT17. As the progression of fibrotic lesions gradually progresses from the lung periphery toward the center of the lobe (Fig. 6A)43,44, we examined the expression of these keratins across these regions (Figs. 6B, B1–5). In the central regions of the bleomycin-treated lung, we observed simple squamous and cuboidal KRT7+ cells lacking KRT17 and KRT5 expression (Fig. 6B, B1). These KRT7+ cells gradually adopted KRT17 and/or KRT5 expression as lesions progressed to the peripheral lung, where the dysplastic epithelium retained a heterogeneous pattern of keratin expression within cuboidal and columnar cells (Fig. 6B, B1–B5). Of note, the co-expression of these three keratins overlapped mainly in columnar epithelial cells of lesions midway between the center and periphery (Fig. 6B4). The expression of KRT7 and KRT17 in columnar cells of the peripheral bleomycin lung consistently overlapped; however, a subset of KRT5+ basal-like cells did not express KRT7 or KRT17 (Fig. 6B5). Subpopulations of KRT7+/KRT17+ cells also expressed TP63, suggesting they had adopted a “basaloid-like” phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S8D–F). In addition, in the bleomycin-treated ferret lung is highly heterogenous, as in human IPF34,35,45,46.

A Schema of ferret internal organs including the lung (a); the central and peripheral locations of all lobes of the lung (b); a single lobe (c) with the level at which cross sections were cut indicated (red dashed line); and a cross section of a lobe (d) used for IF staining and tile imaging from center to the periphery of the lung of in bleomycin-treated ferrets (B) (created with BioRender’s icons). B Representative IF images of colocalization of KRT5, KRT7 and KRT17 showing the different states of aberrant epithelial cells from the center to the periphery (1-5) in fibrotic ferret lungs. (B1-B5) Single-channel images of the corresponding boxed areas 1–5 in B, showing the patterns of expression of epithelial cell markers KRT5, KRT7 and KRT17 from the lobar center to the periphery in fibrotic ferret lungs. C Representative IF images of co-staining of KRT8, KRT7 and KRT5. Images in right panels are enlarged double-channel images of the boxed area in the left panel. D Pseudotime trajectory analysis of AT2, transitional AT2, Basaloid-like/Basal, and AT1 cells. E UMAP plot showing expression of the AT2 marker SFTPC along the trajectory. F UMAP plot showing expression of the AT1 marker AGER along the trajectory. G UMAP plots showing expression of the secretory-cell markers SCGB1A1 and SCGB3A2 along the trajectory. H UMAP plots showing expression of the basal-cell markers KRT7, KRT8, KRT5 and TP63 along the trajectory. Scale bars in B and C equal 200 μm; in B1-B5, and right-hand panels of C they equal 50 µm.

Evidence from human IPF and rodent lung injury models has suggested that AT2 cells progressively transdifferentiate into various aberrant epithelial cell types within fibrotic lesions. Therefore, to track the origin of aberrant epithelial cells in ferret fibrotic lesions we performed pseudotime analysis on AT2 cells. Notably, ferret AT2 cells show multiple distinct trajectories (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Fig. S9), including transitional AT2 cells (defined by SFTPC low, IGFBP7+, RTKN+, KRT8low expression) to immature AT1 (AGER+/MYRFlow) and then to mature AT1 cells (AGER+/MYRFhigh) (Fig. 6E,F and Supplementary Fig. S10A–C). Alternatively, transitional AT2 cells can take a distinct trajectory to KRT8high/KRT7high/SOX4+ and then to KRT8high/KRT7high/SFN+/TP63+/KRT5low “basaloid-like” cells (Fig. 6G,H and Supplementary Fig. S10A–C). In addition to these key changes, we also observed changes in additional markers that are described in human IPF and rodent fibrosis scRNA-seq data sets (Supplementary Fig. S10A–C)34,35,36,42,47,48. These observations in conjunction with immunofluorescent localization data suggest that de-novo bronchiolization of the distal lung epithelium occurs in bleomycin-induced ferret fibrotic lungs, as postulated in humans12,49, and that AT2 cells are a likely progenitor cell intermediate involved in formation of the dysplastic proximalized epithelium in ectopic bronchiolized structures that develop in human IPF lungs.

Mesenchymal cell dynamics in bleomycin-injured ferret lungs

Focusing on transcriptional alterations in distal lung mesenchymal cells after bleomycin injury, we analyzed 19,628 mesenchymal cells and identified six well segregated mesenchymal cell clusters with unique signature genes (Fig. 7A, B). These included adventitial fibroblasts (DCN, FBLN1, PI16 and GLI2); alveolar fibroblasts (PDGFRA, TCF21, and FN1); mesothelial cells (WT1, HAS1 and SOD3); myofibroblasts and smooth muscle cells (ACTA2, CNN1, MYH11, RUNX1, CP and TMP1); pericytes (PDE5A, PDGFRB and POSTN); and transitional alveolar fibroblasts, which express a combination of fibroblast/pericyte (PDGFRA, TCF21 and PDE5A), myofibroblast (RUNX1, SFRP1 and CP) and collagen (COL1A1, COL3A1 and COL5A1) markers (Fig. 7C and D). These annotations were validated by the clustering and consistent with results from other lung studies35,50,51,52,53. Additionally, the analysis of snRNA-seq data revealed a significant increase in the proportion of myofibroblasts and mesothelial cells in response to bleomycin, while there was a decrease in alveolar/lipo fibroblasts (Fig. 7E left panel). This change was accompanied by elevated expression of collagen genes (Fig. 7E right panel). Immunofluorescence staining further showed an increased abundance of CNN1+/ACTA2+-activated myofibroblasts (Fig. 7F) that increased with higher Ashcroft scores (Supplementary Fig. S11), and accumulation of collagen 1A1 and KRT7+ cells surrounding myofibroblast foci (Fig. 7G, I) with interspersed SPC-expressing AT2 cells (Fig. 7H, I) in bleomycin injury compared to control lungs. These observations support the close epithelial-mesenchymal interactions that contribute to the progression of fibrotic lesions and are consistent with findings from the human IPF lung54. CellphoneDB analysis of ligand-receptor pairs predicted that KRT7+ transitional cells may secrete the ligands TGFB and EREG, which could interact with receptors found in various fibroblast subtypes and other mesenchymal cell types (Fig. 7J). Similarly, IGF1 was expressed by adventitial and transitional fibroblasts, and to a lesser extent by myofibroblasts/smooth muscle cells. The corresponding receptor (IGFR1) was present in both KRT7+ transitional cells and AT2 cells, as well as in other mesenchymal cells (Fig. 7J).

A UMAP showing annotated mesenchymal cell subtypes snRNA-seq data. B UMAPs showing differences in types and proportion of mesenchymal cells between ferrets treated with bleomycin and saline. C Dot plot showing the frequency of expression of markers of cell types and transitional cell states. D UMAPs showing expression of the DCN, PDGFRA, TCF21, PDGFRB, ACAT2 and CNN1 genes. E Bar plots showing the proportion of each mesenchymal-cell subtype in bleomycin- and saline-treated lungs (Left panel). Heatmaps of the differential expression of collagen genes in bleomycin- and saline-treated ferret lungs (Right panel). F Representative IF images showing co-staining of ACTA2 (green) and CNN1 (red) in saline control (left panel) and bleomycin-injured (right panel) ferret lungs. G Representative IF images of co-staining of Collagen1 and ACTA2 in bleomycin-injured (right panel) and saline control (left panel) lungs. H Representative IF image of co-staining of SPC and ACTA2 in saline control (left panel) and bleomycin-treated (right panel) ferret lungs. I Representative IF image of co-staining for SPC (green), KRT7 (red), and ACTA2 (white) in bleomycin-treated ferret lung. Inset indicates enlarged region and individual channels of regions marked by dashed box. DAPI-nuclei (blue). Scale bars in E–I equal 100 µm; in enlarged panels in (I), they equal 20 µm. J Dot plot showing the ligands and receptor expressed by respective cell types.

Discussion

Here we present a ferret model of bleomycin-induced acute lung injury, which develops chronic dysplastic regenerative disease resembling human IPF. The key shared histopathological, cellular, and molecular features included fibrotic foci formation, honeycomb cyst-like structures, bronchiolization, and the emergence of aberrant KRT7+/KRT17+/KRT5–/TP63+ basaloid-like cells34,35,55. This ferret model also recapitulated the physiologic changes in pulmonary compliance and radiographic imaging observed in individuals with IPF. Due to the anatomical, cellular, and molecular differences between mouse and human lungs, as well as the disease mechanisms in pulmonary fibrosis56,57,58, the ferret presents promising opportunities for studying IPF pathophysiology.

A notable difference between human IPF and rodent models of lung injury is that the individuals with the condition often develop permanent, chronic, and progressive fibrosis, whereas rodents generally exhibit self-limiting disease progression and reversible fibrosis4,5,6,59. However, other studies have shown that more permanent fibrosis can also occur in aged rodents following repeated bleomycin-induced injury6,60,61,62,63 or influenza viral infection7,62,64,65. While a single dose of bleomycin to mouse lung leads to limited alveolar epithelial cell remodeling, inflammatory infiltrates, and spontaneously resolvable lung fibrosis4,6,66,67, repetitive doses of bleomycin can induce progressive lung fibrosis in aged mice up to 24 weeks post injury. These later rodent studies recapitulate some of the radiographic and pathohistological features of human IPF, including extensive epithelial remodeling and formation of honeycomb cyst structures in the lung parenchyma4,6,62,67,68.

Similar to young mice, our study also suggests that younger ferrets had a greater ability to recover pulmonary lung function following 3 doses of bleomycin (2.5 U·mL−1·Kg−1) as compared to aged ferrets, suggesting certain age-related commonalities in regenerative potential between the two species. Our findings that repetitive bleomycin injury led a persistent chronic fibrotic state in aged ferrets extending to 12 weeks post injury is consistent with another recent study in ferrets by Peabody et al.25. This study used a single dose of concentrated bleomycin (5 U·mL−1·Kg−1) and also showed persistent fibrotic injury and dysplastic repair with bronchiolization and KRT17+/P63+/KRT5low basaloid-like cells in lung at 22 week post injury25. Furthermore, this study highlights the similarities in pulmonary function and radiographic imaging between ferrets and humans with pulmonary fibrosis, offering additional insight into the persistence of dysplastic repair in the ferret lung after a single severe injury.

By analyzing single-cell datasets and conducting lineage tracing assays in mouse models of pulmonary fibrosis, induced either by viral infections62,66,69 or by repeated bleomycin-induced lung epithelial injury6,67,70,71, multiple studies have shown that the epithelial cells contributing to bronchiolization of the distal lung predominantly arise from p63⁺ basal cells62,70, which themselves appear to derive from distal airway secretory cells72. These dysplastic mouse airway progenitors are capable of differentiating into either AT2 and AT1 cells or forming aberrant bronchiolized honeycomb cysts following bleomycin-mediated lung injury71. In this context, transitional cell states that give rise to aberrant basaloid-like cells appear to contribute to bronchiolization in both mouse models and human cases of IPF42,45,53,68,73,74. Krt8 is the signature marker elevated in the epithelial transitional state of rodent lungs following severe acute injury34,68,74, whereas KRT17 is highlighted as a marker of the transitional state cell in human IPF34,35,55,68,75,76. Nonetheless, the origins of basaloid-like cells in human lungs following severe acute lung injury and IPF remain an open question and could involve distal airway basal cells, secretory cells, and/or AT2 cells12,37,56,57.

Compared with rodent models, our snRNA-seq analysis of saline and bleomycin-treated ferret lungs further identified molecular features reflective of substantial epithelial remodeling and macrophage activation following injury and cellular transitional states that mirrored those seen in humans and nonhuman primates12,37,76,77. Trajectory analysis of single-cell-transcriptomes supports AT2 cells acquire a transitional state that bifurcates to generate both AT1 and basaloid-like cells, a finding similar to human IPF lungs. Immunolocalization assays confirmed the widespread presence of KRT7⁺, KRT8⁺, and KRT17⁺ cells, and revealed that the majority of KRT17⁺ cells were localized within areas of bronchiolization, where a subset of these cells were KRT17+/P63⁺/KRT5low—a phenotype characteristic of basaloid cells previously identified in human IPF34,35,55. These results are in agreement with previous findings of aberrant epithelial cell types and states in fibrotic distal lungs of human IPF, including the KRT17+/TP63+/KRT5– basaloid cell type that has both the expression profile of basal epithelial cells and features of mesenchymal transition34,35,42,45,47. However, these analyses have not resolved whether RAS/TRB-SC12,37 or AT0 cells12 contribute to dysplastic regenerative states in bleomycin-treated lungs. Of note, the lineage trajectories we identified are based on in silico predictions, and future studies are needed to validate these observations using lineage tracing in ferret models. Collectively, the phenotypic differences in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in ferrets compared to mice suggest that variations in lung anatomy and cell biology may give rise to distinct progenitor cell states that influence the dysplastic repair process. Whether these differences reflect discrete lineage-specific outcomes or indicate a species-specific bias within a continuum of phenotypes derived from multiple lineages remains to be determined. For example, both RAS/TRB-SC progenitor populations and respiratory bronchioles are present in the ferret and human lungs, but are absent in the mouse lung12,37,56.

Recent studies in mice have introduced the concept of injury-induced tissue stem cell niches that form following acute lung injury66. This study proposes that injury-induced niches can drive dysplastic nonproductive repair leading to disease pathology and compete with niches that drive euplastic productive repair. Although these proposed mechanisms for IPF in humans are largely based on studies in transgenic mouse models, it remains to be seen if the biology and cell types involved in injury-induced niches and dysplastic repair differ in larger species, like ferrets, and if they bear greater similarity to those seen in humans. Given anatomical and cellular differences in the respiratory zones, precursor populations contributing to proximalization of the airspaces and basaloid cells, which drive structural and functional pathology in pulmonary fibrosis, may vary significantly between rodents and humans57. Ferrets may provide an opportunity to bridge this biologic and scientific gap.

Fibrosis-induced proximalization of distal airways and bronchiolization of the airspace typically initiates at the plural surface, or along the interlobular septa, and progresses toward the center of the lobe43,44,78. Current thinking is that these regions of the lung have unique physical forces and a biochemical makeup rich in collagens that enhances fibrogenic signals in the setting of inflammation and injury44,78. The ferret bleomycin model appears to reproduce this unique aspect of anatomical fibrotic disease progression in IPF. snRNA-Seq analysis and immunostaining revealed aberrant fibroblast and myofibroblast differentiation, as well as ECM accumulation in bleomycin ferret lungs that closely resembles that in human IPF and mouse models. Notably, the presence of KRT7+ cells outside of myofibroblast foci (separating fibrotic foci from the adjacent transitional AT2 cells), suggested that KRT7+ transitional cells may mediate the cellular interactions between fibroblasts and AT2 cells during fibrosis. Indeed, interactions between epithelial and mesenchymal cells are key drivers of aberrant differentiation of epithelial cells and fibroblasts, as well as of ECM accumulation in the lungs of individuals with IPF53,54. In particular, the communication between AT2 cells and fibroblasts is important for maintaining the appropriate architecture and homeostasis of the distal lung53. Our interactome-based analysis suggest that two-way interactions exist between KRT7 transitional cells (particularly interactions involving the highly expressed TGFB2) and various mesenchymal cell types. Additionally, we observed an increased proportion of activated macrophages characterized by the CD9⁺/TREM2⁺ subset expressing SPP1, TREM2, FABP5, and GPNMB, known as scar-associated macrophages (SAMs) (Supplementary Fig. S6F). These are believed to emerge in human IPF lungs and liver fibrosis, where distinct activation states are thought to impact fibrosis progression or resolution34,77,79. Besides the SAM-specific signature genes, these ferret macrophages also expressed the myeloid marker SIGLEC15 and the neutrophil marker MMP9 in bleomycin-exposed ferret lungs (Supplementary Fig. S6F).

Compared to other reported ferret IPF models induced by a single higher dose (5 U·mL⁻¹·Kg⁻¹) of bleomycin25, our model was established using three lower-dose administrations (2.5 U·mL⁻¹·Kg⁻¹). While both studies provide compelling evidence for dysplastic repair processes leading to basaloid-like cell formation and bronchiolization of the airspaces, accompanied by reduced pulmonary function and increased lung opacification25, our study placed greater emphasis on defining the cellular and molecular profiles observed in ferret lung injury compared to those previously observed in human IPF. Using the ferret bleomycin model, we employed snRNA-seq analysis and immunolocalization assays to examine these processes at single-cell resolution. The work by Peabody et al. effectively complements our study by systematically characterized clinically relevant aspects of IPF, including pulmonary function testing, CT imaging, and histopathological changes involved in proximalization and bronchiolization of the distal lung25.

Our study also has certain limitations. In particular, repeated administration of bleomycin at a dose of 2.5 U·mL⁻¹·kg⁻¹ led to the rapid onset of severe fibrotic phenotypes within four weeks and reached humane endpoints in most ferrets by 6–12 weeks. This limited our ability to accumulate a larger cohort of animals with advanced chronic fibrosis. This limitation is addressed in part by the findings of the Peabody et al. study25. Additional challenges stem from the fact that ferrets are a relatively new model system, with limited availability of biological reagents and an orphan genome that remains suboptimal for transcriptional analysis. For example, the KRT17 gene has not yet been annotated in the ferret genome. Lastly, there is a need to establish a bleomycin dose–response curve and optimize the dosing regimen to define the temporal progression of inflammatory and fibrotic events that lead to persistent pulmonary fibrosis.

In summary, we demonstrate that the bleomycin-induced ferret model emulates critical features of human IPF, positioning it as a promising alternative to rodent models by capturing cellular differences underlying pathogenic etiology. Notable features include sustained fibrosis persisting to the humane endpoint, irreversible bronchiolization of the distal lung, cell state changes resembling those observed in human disease, and increased ECM deposition. Future studies can leverage this model to explore cellular mechanisms and test IPF therapies, potentially bridging the gap between preclinical findings and human clinical applications.

Methods

Creation of an IPF ferret model using bleomycin challenge

All animal experiments and protocols received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Iowa (Protocol ID1071945) and adhered to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ARRIVE 2.0 guideline. Humane/euthanasia endpoints include labored breathing with a respiratory rate exceeding 90 bpm or lack of movement or response upon stimulation. All animals were euthanized by i.p. injection of Euthasol (a euthanasia solution containing pentobarbital and phenytoin) when a humane/euthanasia endpoint was reached or an experiment was concluded. Male and female domestic ferrets (3–24 months) were obtained from Marshall Farms (North Rose, NY, USA) and housed under controlled temperature (20–22 °C) with a light cycle of 16 h light/8 h dark and ad libitum access to water and diet. Animals were used for experimental purposes after 2 weeks of acclimatization. Ferrets were injured by administering three doses of BLM (2.5 units/ml/kg in saline, Fresenius KABI, Chicago, IL) at 1-week intervals via the laryngotracheal route, using a MADgic® Laryngo-Tracheal Mucosal Atomization Device (Teleflex, Morrisville, NC). The first dose of BLM was administered on the first day of Week 0. Throughout the study, all ferrets were monitored daily for activity level, body weight, and respiratory rate.

Procedure for anesthesia

Animals were anesthetized by subcutaneous injection of ketamine (5–25 mg/kg) and xylazine (0.5–1.5 mg/kg). Additional isoflurane (0%–5%) supplemented with oxygen flow was provided to sustain anesthesia during pulmonary function testing, CT scanning or intrapulmonary delivery of BLM. Throughout the procedure, temperature, pulse, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and general clinical condition were monitored and recorded by trained personnel. Anesthesia was reversed immediately after the procedure was completed by intramuscular injection of atipamezole (0.5 mg/kg). Animals were returned to their cage after they were fully recovered, following a monitoring period.

Assessment of pulmonary function

In ferrets, PFT was performed using a previously described protocol20. In brief, ferrets were anesthetized and intubated with an appropriately sized cuffed endotracheal tube (male I.D.: 3.0 mm, O.D.: 4.2 mm; female I.D.: 2.5 mm, O.D.: 4.0 mm) by a trained operator using a laryngoscope. Intubation was confirmed during a pre-calibration procedure by visualizing the passage of the laryngeal lumen through the cords and examining pressure tracings on a flexiVent ventilator (SCIREQ Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Routine ventilation parameters were a tidal volume (Vt) of 10 ml/kg, a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 3 cmH2O, and a respiratory rate of 60 breaths/min (bpm), which resulted in mild hyperventilation. Pulmonary function was assessed using the FX Module 6 of the flexiVent mechanical ventilator system, a computer-controlled piston ventilator that allows control of ventilation parameters16. Anesthetized ferrets were placed on the heated plate, and the endotracheal tube was connected to the in-line ventilator. Baseline parameters were calibrated and acquired, and then multiple forced maneuvers were performed to assess parameters of pulmonary functions, including inspiratory capacity (IC), forced expiratory volume (FEVx) at defined times (defined as “x” seconds), forced vital capacity (FVC), resistance of the respiratory system (Rrs), elastance of the respiratory capacity (Ers), compliance of the respiratory system (Crs), Newtonian resistance (Rn), tissue damping (G), tissue elastance (H), pressure volume (PV) loop, and quasi-static compliance (Cst). For flexiVent perturbations, a coefficient of determination of 0.95 or above was considered acceptable. All test maneuvers and perturbations were conducted until three acceptable measurements were collected. The collected data were analyzed using the pre-installed Scireq flexiWare Version 8.0, Service Pack 4 (Montreal, QC Canada). For each mechanical parameter, a total of six technical replicate measurements were performed and the average value was used for data representation.

CT imaging and quantification

Ferrets were anesthetized and imaged in the prone position using a SOMATOM Force dual-source CT scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Germany) in the Flash (dual-source) scanning mode. The ferrets breathed spontaneously during scanning. Full inspiration (end-tidal: ET) scans were obtained by scanning each ferret continuously 5 to 10 times and selecting the image with the largest lung volume as the ET scan. All images were acquired with the following parameters: detector configuration, 192 × 0.6 mm; kVp, 100; mAs: 100; slice thickness, 0.6 mm; slice interval, 0.3 mm; reconstruction kernel, Qr49 ADMIRE 3; scan pitch, 2.8; rotation time, 0.25 s. Quantification was performed using the Pulmonary Analysis Software Suite (PASS) (University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa), a software package that was developed in-house and customized for volumetric analysis of lung opacification by Hounsfield units (HU) in ferret lung disease models80. The left and right lungs were each segmented first, and then histogram analysis was applied to each segment to identify the high-density (fibrotic-like) lung regions based on the percentage of lung voxels with intensity values falling between –500 HU and 0 HU80,81.

Analysis of histopathology

Ferrets were euthanized when in clinical distress or at the end of the study. All five main lobes (except the accessory cordate lobe) were separately isolated. The middle portion of each lobe was fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin (10% NBF) and embedded for histopathological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses. The remaining lung tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen (LN2). Collagen deposition in lung was semi-quantified based on Masson’s trichrome staining of sections82. Morphological changes of fibrosis in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung sections were graded using the Ashcroft scale, by three independent researchers blinded to experimental conditions83,84. For this analysis, all parenchyma in the lung sections were assessed at 5× magnification after slide digitalization, using the 0–8 point Ashcroft scale. The mean of three individual scores of all five lobes served as the final Ashcroft score for analysis of each animal83,84.

Measurement of hydroxyproline content

Plasma and tissue from the combined lung lobes were homogenized for isolation of total protein. The HYP content of each sample was measured using a hydroxyproline assay kit (Ab222941, Abcam, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The HYP content of plasma is presented as µg/mL of volume, and that of wet lung tissue as µg/mg of protein.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

Frozen sections (8-µm) of lung tissues embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound were air dried for 30 min at room temperature before being post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min. Tissue sections were then permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, blocked with 5% donkey serum for 2 h, incubated with primary antibody in diluent buffer (1% donkey serum, 0.03%Triton X-100, and 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS) at 4 °C overnight, and incubated with Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Paraffin sections were prepared similarly, but were subjected to deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieved before being blocked in blocking buffer. Slides containing nuclei that were stained using DAPI or Hoechst 333427 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were then mounted with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and imaged on a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). All images were processed using FIJI-ImageJ software. The primary and secondary antibodies used for IHC staining are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Measurement of proteins in plasma using in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Ferret plasma was diluted (1:10) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer. Diluted plasma (200 µl) was used to coat each well of a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microtiter plate at 4 °C overnight. The coated wells were rinsed three times with washing buffer (PBS and 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 7.4)) and blocked with 5% non-fat milk in washing buffer for 2 h at 37 °C. After washing three times for 5 min each, 100 µl of diluted primary antibody (1:1000 in washing buffer) (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) for the protein of interest was added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The wells were washed five times for 5 min each and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000 in washing buffer). After the wells were again washed five times for 5 min each, 100 µl of TMB substrate solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to each and the samples were incubated in the dark for 15–30 at room temperature, at which point 100 µl of stopping solution (2 M H2SO4) was added to the wells. Optical density (OD) of the xx plate wells was measured at 450 nm (OD450nm) using a SpectraMax i3x Microplate Reader (Molecular Device, San Jose, CA). A no-plasma (PBS alone) well served as a blank control. The results are presented as ∆OD450nm, defined as the difference between the value of the OD450nm readout of the experimental sample substrate and the readout of the blank control.

Isolation and 10x sequencing of single nuclei RNA from ferret lung

Lung nuclei were isolated using a CST buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 292 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 42 mM MgCl2, 1% CHAPS, and 2% BSA) as described previously85. Briefly, snap-frozen lung tissues (50 mg) were immediately placed into a nuclei isolation using CST buffer, and a dounce homogenizer was used to mechanically dissociate nuclei from cells. The resulting homogenate was filtered through a 40 µm strainer, and nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 300 × g for 2 min at 4 °C. Nuclei were resuspended in 0.04% BSA buffer to a final concentration of 1000 nuclei/µl. Single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) libraries were prepared using the 10x Genomics 5’ Kit v2, following the manufacturer’s protocol (10X Genomics). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Nextseq 550 platform using 75-cycle paired-end sequencing, and 8 bp for the index read, 28 bp for the R1 read, and 56 bp for the R2 read.

Processing and analysis of snRNA-seq data

Illumina BCL files were processed to fastq format using the bcl2fastq v2.2.0 conversion software. To generate a count matrix, the sequenced files from each independent sample were processed through 10X the Genomics Cell Ranger software v7.1.0, using the default “include intron” mode and a reference build from Mustela putorius furo (domestic ferret) reference genome ASM1176430v1.1.

Samples were annotated for ambient content using Dropkick (https://github.com/KenLauLab/dropkick) and annotated with doublet scores using Scrublet (https://github.com/swolock/scrublet), both of which are built into the Scanpy toolkit (https://github.com/scverse/scanpy). Filtered feature-barcode matrices from Cell Ranger were initially filtered using Cell Ranger knee cutoffs to remove cells with unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts above the 99 and below the 4 percentile, unless the 4th percentile UMI count was less than 800, in which case a floor of 800 UMI was used. Cells annotated as doublets, cells with greater than 4% mitochondrial UMIs, and cells with a Dropkick score below 0.25 were then removed.

Visualization, dimensionality reduction, and clustering of raw data

The filtered raw count data were then annotated using a reference-based annotation tool (https://github.com/gordian-biotechnology/celltype_predict_ACTINN) using multiple published lung datasets (GSE135893, GSE136831, and the human cell lung atlas). snRNA-seq datasets were normalized and transformed the filtered count matrix as per standard Pearson residuals Scanpy pipeline. Dimension reduction was performed using the top 3500 highly variable genes, and the top 50 principal components were calculated and used for nearest neighborhood graph Leiden clustering and UMAP visualization. Cell type labels were assigned to Leiden clusters based on consensus cell-type labels from references and specific cell-type markers such as KRT7 to annotate specific subpopulations. All details of data processing, filtering, and annotation are shown in the accompanying Jupyter notebooks.

Cell type annotation and pseudotime analysis

Many higher-order vertebrate genes are orthologous and have been evolutionarily conserved, and annotation of the ferret genome has traditionally relied on the human reference genome as a guide28. Human ortholog names were assigned to ferret genes when corresponding entries were found in the Ensembl or NCBI databases. In addition, for ferret genes that remain unannotated, human ortholog names were assigned when an orthologous relationship was identified, based on Ensembl’s ortholog definitions. For cell type identification, we selected the top 20 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each cell type (Supplementary Data Files 1 and 2), complemented by well-established human gene markers documented in the literature28. Psuedotime analysis was computed using the Palantir (https://github.com/dpeerlab/Palantir) v1.3.3 software86,87.

Prediction and visualization of cell-cell interactions

Cell-cell interaction scores were computed using the Cellphone database (https://github.com/ventolab/CellphoneDB) v5.0.186,87.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

Data analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For all experiments, data are shown as mean ± SEM, unless indicated otherwise. Comparisons between two groups were done using an unpaired two-tailed t-test, and comparisons of more than two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Figures and legends provide the number of independent experiments and the results of representative experiments.

Data availability

snRNA-Seq data were deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE279470). Reviewers can access the deposited sequence data at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE279470) using the following token (snizcegudxwzbmt). Values for all data points in graphs can be found in the Supplemental Data file.

Code availability

The majority of the analysis was carried out using published and freely available software and pre-existing packages mentioned in the methods. No custom code was generated. R scripts used to analyze data and generate figures are available upon request to VS and XL.

References

Biondini, D. et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (AE-IPF): an overview of current and future therapeutic strategies. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 14, 405–414 (2020).

Glass, D. S. et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current and future treatment. Clin. Respir. J. 16, 84–96 (2022).

Shaghaghi, H. et al. A model of the aged lung epithelium in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Aging 13, 16922–16937 (2021).

Moore, B. B. & Hogaboam, C. M. Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 294, L152–L160 (2008).

Mayr, C. H. et al. Sfrp1 inhibits lung fibroblast invasion during transition to injury-induced myofibroblasts. Eur. Respir. J. 63, https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01326-2023 (2024).

Redente, E. F. et al. Persistent, progressive pulmonary fibrosis and epithelial remodeling in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 64, 669–676 (2021).

Narasimhan, H. et al. An aberrant immune-epithelial progenitor niche drives viral lung sequelae. Nature 634, 961–969 (2024).

Fleischman, R. W. et al. Bleomycin-induced interstitial pneumonia in dogs. Thorax 26, 675–682 (1971).

Derseh, H. B. et al. Small airway remodeling in a sheep model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Exp. Lung Res. 46, 409–419 (2020).

Perera, U. E. et al. Comparative study of ectopic lymphoid aggregates in sheep and murine models of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Can. Respir. J. 2023, 1522593 (2023).

Balazs, G., Noma, S., Khan, A., Eacobacci, T. & Herman, P. G. Bleomycin-induced fibrosis in pigs: evaluation with CT. Radiology 191, 269–272 (1994).

Kadur Lakshminarasimha Murthy, P. et al. Human distal lung maps and lineage hierarchies reveal a bipotent progenitor. Nature 604, 111–119 (2022).

Smith, R. E., Choudhary, S. & Ramirez, J. A. Ferrets as models for viral respiratory disease. Comp. Med. 73, 187–193 (2023).

Chiba, S. et al. Ferret model to mimic the sequential exposure of humans to historical H3N2 influenza viruses. Vaccine 41, 590–597 (2023).

Kim, Y. I. et al. Infection and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Cell Host Microbe 27, 704–709.e702 (2020).

Raju, S. V. et al. A ferret model of COPD-related chronic bronchitis. JCI Insight 1, e87536 (2016).

Sui, H. et al. Ferret lung transplant: an orthotopic model of obliterative bronchiolitis. Am. J. Transpl. 13, 467–473 (2013).

Lynch, T. J. et al. Ferret lung transplantation models differential lymphoid aggregate morphology between restrictive and obstructive forms of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Transplantation 106, 1974–1989 (2022).

Swatek, A. M. et al. Depletion of airway submucosal glands and TP63(+)KRT5(+) basal cells in obliterative bronchiolitis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 197, 1045–1057 (2018).

He, N. et al. Ferret models of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency develop lung and liver disease. JCI Insight 7, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.143004 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. In utero and postnatal VX-770 administration rescues multiorgan disease in a ferret model of cystic fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aau7531 (2019).

Evans, I. A. et al. In utero and postnatal ivacaftor/lumacaftor therapy rescues multiorgan disease in CFTR-F508del ferrets. JCI Insight 9, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.157229 (2024).

Sun, X. et al. Lung phenotype of juvenile and adult cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-knockout ferrets. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 50, 502–512 (2014).

Khoury, O. et al. Ferret acute lung injury model induced by repeated nebulized lipopolysaccharide administration. Physiol. Rep. 10, e15400 (2022).

Peabody Lever, J. E. et al. Pulmonary fibrosis ferret model demonstrates sustained fibrosis, restrictive physiology, and aberrant repair. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.06.04.597198v1.full (2024).

Sontake, V. et al. Cross-species transcriptome comparison revealed shared similarities between ferret sustainedpulmonary fibrosis model and human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 209, A2592 (2024).

Yu, M. et al. Highly efficient transgenesis in ferrets using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-independent insertion at the ROSA26 locus. Sci. Rep. 9, 1971 (2019).

Yuan, F. et al. Transgenic ferret models define pulmonary ionocyte diversity and function. Nature 621, 857–867 (2023).

Sese, L. et al. Gender differences in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: are men and women equal?. Front. Med. 8, 713698 (2021).

Raghu, G., Chen, S. Y., Hou, Q., Yeh, W. S. & Collard, H. R. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18-64 years old. Eur. Respir. J. 48, 179–186 (2016).

Solopov, P., Colunga Biancatelli, R. M. L., Dimitropoulou, C. & Catravas, J. D. Sex-related differences in murine models of chemically induced pulmonary fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115909 (2021).

d’Alessandro, M. et al. Serum concentrations of KL-6 in patients with IPF and lung cancer and serial measurements of KL-6 in IPF patients treated with antifibrotic therapy. Cancers 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040689 (2021).

Jehn, L. B. et al. Serum KL-6 as a biomarker of progression at any time in fibrotic interstitial lung disease. J. Clin. Med. 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031173 (2023).

Adams, T. S. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1983 (2020).

Habermann, A. C. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals profibrotic roles of distinct epithelial and mesenchymal lineages in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1972 (2020).

Reyfman, P. A. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 199, 1517–1536 (2019).

Basil, M. C. et al. Human distal airways contain a multipotent secretory cell that can regenerate alveoli. Nature 604, 120–126 (2022).

Conti, C. et al. Mucins MUC5B and MUC5AC in distal airways and honeycomb spaces: comparison among idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/usual interstitial pneumonia, fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis, and control lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193, 462–464 (2016).

Seibold, M. A. et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1503–1512 (2011).

Kurche, J. S. et al. MUC5B idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis risk variant promotes a mucosecretory phenotype and loss of small airway secretory cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 210, 517–521 (2024).

Carraro, G. et al. Single-cell reconstruction of human basal cell diversity in normal and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 1540–1550 (2020).

Huang, K. Y. & Petretto, E. Cross-species integration of single-cell RNA-seq resolved alveolar-epithelial transitional states in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 321, L491–L506 (2021).

Mai, C. et al. Thin-section CT features of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis correlated with micro-CT and histologic analysis. Radiology 283, 252–263 (2017).

Wu, H. et al. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis is caused by elevated mechanical tension on alveolar stem cells. Cell 180, 107–121.e117 (2020).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Persistence of a regeneration-associated, transitional alveolar epithelial cell state in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 934–946 (2020).

Choi, J. et al. Inflammatory signals induce AT2 cell-derived damage-associated transient progenitors that mediate alveolar regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 27, 366–382 e367 (2020).

Jin, C. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals special basal cells and fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 14, 15778 (2024).

Xie, T. et al. Single-cell deconvolution of fibroblast heterogeneity in mouse pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Rep. 22, 3625–3640 (2018).

Kathiriya, J. J. et al. Human alveolar type 2 epithelium transdifferentiates into metaplastic KRT5(+) basal cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 24, 10–23 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Categorization of lung mesenchymal cells in development and fibrosis. iScience 24, 102551 (2021).

Tsukui, T. et al. Collagen-producing lung cell atlas identifies multiple subsets with distinct localization and relevance to fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 1920 (2020).

Tsukui, T., Wolters, P. J. & Sheppard, D. Alveolar fibroblast lineage orchestrates lung inflammation and fibrosis. Nature 631, 627–634 (2024).

Konkimalla, A. et al. Transitional cell states sculpt tissue topology during lung regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 30, 1486–1502.e1489 (2023).

Mei, Q., Liu, Z., Zuo, H., Yang, Z. & Qu, J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an update on pathogenesis. Front. Pharm. 12, 797292 (2021).

Jaeger, B. et al. Airway basal cells show a dedifferentiated KRT17(high)Phenotype and promote fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 13, 5637 (2022).

Basil, M. C. et al. The cellular and physiological basis for lung repair and regeneration: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell 26, 482–502 (2020).

Basil, M. C. & Morrisey, E. E. Lung regeneration: a tale of mice and men. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 100, 88–100 (2020).

Stancil, I. T., Michalski, J. E. & Schwartz, D. A. An airway-centric view of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206, 410–416 (2022).

Tashiro, J. et al. Exploring animal models that resemble idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front. Med. 4, 118 (2017).

Cho, S. J., Moon, J. S., Lee, C. M., Choi, A. M. & Stout-Delgado, H. W. Glucose transporter 1-dependent glycolysis is increased during aging-related lung fibrosis, and phloretin inhibits lung fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 56, 521–531 (2017).

Hecker, L. et al. Reversal of persistent fibrosis in aging by targeting Nox4-Nrf2 redox imbalance. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 231ra247 (2014).

Warren, R. et al. Cell competition drives bronchiolization and pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 15, 10624 (2024).

Warren, R., Lyu, H., Klinkhammer, K. & De Langhe, S. P. Hippo signaling impairs alveolar epithelial regeneration in pulmonary fibrosis. eLife 12, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.85092 (2023).

Kasmani, M. Y. et al. A spatial sequencing atlas of age-induced changes in the lung during influenza infection. Nat. Commun. 14, 6597 (2023).

Yin, L. et al. Aging exacerbates damage and delays repair of alveolar epithelia following influenza viral pneumonia. Respir. Res. 15, 116 (2014).

Jones, D. L. et al. An injury-induced mesenchymal-epithelial cell niche coordinates regenerative responses in the lung. Science 386, eado5561 (2024).

McCall, A. S. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 regulates alveolar regeneration after repetitive injury in three-dimensional cellular and in vivo models. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eadk8623 (2025).

Wang, F. et al. Regulation of epithelial transitional states in murine and human pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 133, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI165612 (2023).

Vaughan, A. E. et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature 517, 621–625 (2015).

Lv, Z. et al. Alveolar regeneration by airway secretory-cell-derived p63(+) progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 31, 1685–1700.e1686 (2024).

Yuan, T. et al. FGF10-FGFR2B signaling generates basal cells and drives alveolar epithelial regeneration by bronchial epithelial stem cells after lung injury. Stem Cell Rep. 12, 1041–1055 (2019).

Beppu, A. K. et al. Epithelial plasticity and innate immune activation promote lung tissue remodeling following respiratory viral infection. Nat. Commun. 14, 5814 (2023).

Jiang, P. et al. Ineffectual Type 2-to-Type 1 alveolar epithelial cell differentiation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: persistence of the KRT8(hi) transitional state. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201, 1443–1447 (2020).

Strunz, M. et al. Alveolar regeneration through a Krt8+ transitional stem cell state that persists in human lung fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 3559 (2020).

Allen, R. J. et al. Genome-wide association study across five cohorts identifies five novel loci associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 77, 829–833 (2022).

Franzen, L. et al. Mapping spatially resolved transcriptomes in human and mouse pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 56, 1725–1736 (2024).

Fabre, T. et al. Identification of a broadly fibrogenic macrophage subset induced by type 3 inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 8, eadd8945 (2023).

Wellman, T. J., Mondonedo, J. R., Davis, G. S., Bates, J. H. T. & Suki, B. Topographic distribution of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a hybrid physics- and agent-based model. Physiol. Meas. 39, 064007 (2018).

Joshi, N. et al. A spatially restricted fibrotic niche in pulmonary fibrosis is sustained by M-CSF/M-CSFR signalling in monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. 55, https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00646-2019 (2020).

Guo, J., Fuld, M. K., Alflord, S. K., Reinhardt, J. M. & A., H. E. The Second International Workshop on Pulmonary Image Analysis http://www.lungworkshop.org/2009/proceedings-2008.html (2009).

Podolanczuk, A. J. et al. High attenuation areas on chest computed tomography in community-dwelling adults: the MESA study. Eur. Respir. J. 48, 1442–1452 (2016).

Van De Vlekkert, D., Machado, E. & d’Azzo, A. Analysis of generalized fibrosis in mouse tissue sections with Masson’s trichrome staining. Bio Protoc. 10, e3629 (2020).

Ashcroft, T., Simpson, J. M. & Timbrell, V. Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a numerical scale. J. Clin. Pathol. 41, 467–470 (1988).

Hubner, R. H. et al. Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological samples. Biotechniques 44, 507–511 (2008).

Nadelmann, E. R. et al. Isolation of nuclei from mammalian cells and tissues for single-nucleus molecular profiling. Curr. Protoc. 1, e132 (2021).

Setty, M. et al. Characterization of cell fate probabilities in single-cell data with Palantir. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 451–460 (2019).

van Dijk, D. et al. Recovering gene interactions from single-cell data using data diffusion. Cell 174, 716–729.e727 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health NHLBI (Federal Contract 75N92024R00008 and R01 HL165404) to JFE and from NHLBI/NIH (R01HL160939 and R01HL153375) to PRT. The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., V.S., and J.F.E. designed research studies. S.W., M.L., A.T., J.A., L.Y., J.W., and J.M. conducted experiments. I.D., H.M., D.P., and V.S. performed snRNA sequencing and analysis. S.S. and H.M. prepared single cell nuclei for sequencing. S.W., J.G., J.A., and E.A.H. performed CT scanning and analysis. V.S. and X.L. analyzed data. S.W., V.S., and X.L. wrote the manuscript. M.B.J., Y.W., P.R.T., and J.F.E. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors ID, HM, SS, DP, MBJ, and VS are employees of Gordian Biotechnology but declare no non-financial competing interests. PRT serves as Editor-in-chief of this journal and had no role in the peer-review or decision to publish this manuscript. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest directly pertaining to this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Driver, I., Luo, M. et al. Ferret model of bleomycin-induced lung injury shares features of human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. npj Regen Med 10, 53 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-025-00440-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-025-00440-z