Abstract

The “dopamine hypothesis” of schizophrenia suggests the imbalance of the brain dopamine system plays a crucial role in the development of this disorder. Although this hypothesis has been partly supported by early studies, the brain region-specific abnormalities of different dopamine subsystems, and the influential factors on the heterogeneity of dopamine dysfunction of schizophrenia are still unknown. To address these issues, we carried out random-effect meta-analyses by collecting 49 in vivo PET studies (692 patients and 730 controls). Patients exhibited significant regional and population heterogeneity in D2/3 receptor availability, primarily manifesting as a moderate increased in the striatum of only drug-off patients (Cohen’s d = 0.56, 95%CI [0.16; 0.97]), whereas only drug-on patients showed a large decrease in D2/3 receptor availability in the thalamus, limbic lobe, substantia nigra, and temporal lobe (Cohen’s d < −1.40). Drug-off patients also had a small increase in dopamine synthesis in the striatum (Cohen’s d = 0.38, 95%CI[0.06; 0.69]), with no replicable dysfunctions in drug-on patients or other brain regions. D1 receptor availability and DAT showed high heterogeneity but no consistent significances. Finally, Meta-regression indicated that elevated striatal D2/3 levels correlated with a higher proportion of males, older patients, longer duration and worse symptoms predicted more severe D1 deficits in the striatum and prefrontal cortex. This study suggests that different dopamine subsystems in schizophrenia are selectively involved across brain regions; moreover, medication status, sex, age, illness duration and symptom diversity have significant impacts on the dysfunctions of dopamine subsystems in schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The “dopamine hypothesis” is one of the leading pathoetiologic theories of schizophrenia and has undergone significant evolution since its inception1,2,3. The classical hypothesis was originally proposed in the mid-20th century following the discovery of antipsychotic drugs dopamine D2 receptor antagonists primarily binding the striatum, thus linking D2 receptor increased in the striatum to positive symptoms like hallucinations and delusions4. However, in recent decades, advancements in understanding dopamine functional subsystems shifted attention to extra-striatal regions such as the mesocortical and mesolimbic pathways, which proposed that dopamine deficit in these pathways, particularly involving the D1 receptor, could better explain the negative symptoms such as social withdrawal and cognitive impairment of schizophrenia5. Moreover, recent multidimensional evidence proposed that schizophrenia arises from a complex interplay between dopamine systems and other neurotransmitters that are complexly influenced by genetic, environmental, and neurodevelopmental factors2,6. Thus, the current “dopamine hypothesis” of schizophrenia reflects a more comprehensive imbalance between increased in the nigrostriatal pathway and deficit in mesocortical/mesolimbic pathways6,7.

Based on this theoretical framework, researchers have expanded their investigations to encompass the entire dopaminergic system, where physiological functions depend on the dynamic equilibrium and coordinated regulation of dopamine synthesis, receptor availability, and dopamine transporter (DAT) functionality8. Dopamine synthesis begins with the catalytic actions of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, directly influencing the storage and release of dopamine within neurons9. Dopamine receptors, categorized into D1-like and D2-like families, modulate cognitive, reward, and motor functions through Gs and Gi protein-mediated signaling pathways10. DAT regulates the reuptake of synaptic dopamine via a sodium-dependent mechanism, thereby maintaining extracellular dopamine concentrations11. These components form a “synthesis-release-reuptake-signaling” loop. In pathological states like Parkinson’s disease and Schizophrenia, imbalances in any part of this loop can lead to widespread neural dysfunction through cascading effects12,13.

The dopamine hypothesis was originally supported by post-mortem brain tissue studies14,15,16 and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dopamine metabolites17. However, post-mortem studies do not account for the active processes of dopamine function, such as dopamine synthesis and release. Cerebrospinal fluid studies also fail to localize the region-specific dopamine dysfunction18,19. The rapid development of molecular imaging technology has provided important evidence for schizophrenia20, including positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission tomography (SPECT). The commercial development of SPECT predates PET21, but its image quality—such as spatial resolution, contrast-to-noise ratio, and biomarker specificity—is inferior to PET, resulting in less effective pathophysiological localization. The discovery of various PET tracers has deepened our understanding of the function and dysfunction of brain dopamine subsystems that assess Dopamine synthesis capacity (DSC), Dopamine transporter availability (DAT) availability, and postsynaptic dopamine receptor availability, respectively22. For example, D1 availability is mainly measured by [11C] NNC 112, [11C] SCH 23390; D2/3 is marked by [11C] FLB 457, [18F] fallypride and [11C] raclopride; DAT availability is evaluated by [11C] PE2I and [18F] CFT; and DSC is represented by L-[β-11C] DOPA and 6-[18F]-Fluorodopa.

PET tracer is used to estimate the average activity of receptor density or enzyme processes in specific brain regions, providing important evidence for revealing the “dopamine hypothesis” of schizophrenia23. However, previous reports on the dysfunction of the dopamine system in schizophrenia patients have great heterogeneity. For example, studies have reported either increased24, decreased25, or no abnormalities25 in striatal D2 receptor availability in schizophrenia; for D1 receptors, although some literature supports the PFC dopamine deficiency hypothesis26, there were also PET studies do not support this finding27,28; in terms of dopamine synthesis, both high29 and low capacity30 were reported in the same striatum. Given the high cost and diverse markers of PET, it is difficult to design a large-sample prospective study to elucidate this issue; alternatively, meta-analysis is a candidate to resolve the possible factors and hierarchical structure leading to the reported heterogeneity by summarizing existing research results. However, most meta-studies on PET dopamine dysfunction of schizophrenia focus only on the average effect of a single dimension, such as a specific dopamine subsystem, brain region, or clinical conditions31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39; only a few meta-analyses have focused on two or more factors40,41,42, and among them only one 2014 study examined the dysfunction distributions of different dopamine subsystems across extrastriatal cortical and subcortical regions42, but it did not fully elaborate on the antipsychotic effect because of limited number of reports at that time.

In this meta-analytic study, we hypothesized that dopamine dysfunctions of schizophrenia are subsystem-dependent and area-dependent. This study aimed: (1) to categorize dopamine system research into three subsystems—presynaptic synthesis, intrasynaptic transport, and postsynaptic binding—and then use meta-analysis to synthesize previous PET studies of schizophrenia across these dopamine subsystems, systematically revealing the heterogeneity of dopamine dysfunction in different brain regions of schizophrenia patients; (2) To explore potential contributing factors to this heterogeneity, such as antipsychotics, age, sex, publication year, illness duration of patients, and severity of symptoms.

Results

After initially identifying 797 articles, 749 were excluded with the pipeline described in Fig. 1, leaving 48 PET dopamine case-control studies involving 692 patients and 730 controls for meta-analyses, including 24 studies on D2/3 receptors availability, 14 studies on DSC, 5 studies on D1 receptors availability, 4 on DAT availability, and 1 study include both D1 and D2/3 receptor availability, the specific studies included in the meta-analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 2. The detailed characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3. The statistical findings of all meta-analyses are shown in Table 2, and all meta-regression results are shown in Table 3. Through full-text review, we identified and excluded seven studies with duplicate samples from the same research group to ensure data independence.27,43,44,45,46,47,48.

D2/3 receptor availability

The meta-analyses on D2/3 receptor availability included 375 patients and 364 controls from 25 studies, among which 5 studies separately reported DF and DN results, resulting in 30 summary statistics including 14 DN, 9 DF, 3 DN/DF, and 4 DO (Table 1).

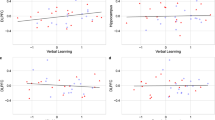

Striatum

Meta-analysis based on all studies did not show statistical abnormality in striatum D2/3 receptor availability (d = 0.41, 95%CI = [−0.01, 0.83]) and demonstrated high heterogeneity (Q = 159.37, p < 0.01; I2 = 86.19%, 95%CI = [80.53%, 90.21%]) but no evidence of publication bias (Egger’s z = 1.18, p = 0.236) (Fig. 2a). When separating the studies into drug-off and drug-on sub-groups, we found a moderately increased D2/3 availability in the striatum of only drug-off patients (Cohen’s d = 0.56, 95% CI [0.16; 0.97]), but no significant effect in the drug-on group (d = −0.36, 95%CI = [−1.75, 1.04]) (Fig. 2a). We further validated the findings on DN patients with moderate D2/3 increased in the stratum (d = 0.77, 95%CI = [0.07, 1.47], Supplementary Fig. 5a). When subgroup analyses were performed by tracer type, consistently significant effects were observed in early studies using [11C]NMSP (d = 1.52, 95%CI = [0.57, 2.47]) but failed using [11C] Raciopride and [11F] Fallypride (Supplementary Fig. 1). Finally, meta-regression demonstrated a negative correlation between publication year and estimated D2/3 effects (β = −0.05, p < 0.01) and a positive correlation between the proportion of males and estimated D2/3 effects (β = 4.06, p < 0.01) (Table 3 and Fig. 2b). Did not find a significant association between reported D2/3 receptor availability and age, illness duration and severity of symptoms (Table 3 and Fig. 2b).

Thalamus

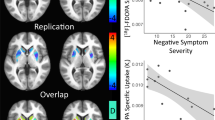

In the thalamus, meta-analysis observed a small effect of decreased D2/3 receptor availability in patients with schizophrenia based on all studies (d = −0.38, 95%CI = [−0.73, −0.03]) and demonstrated medium heterogeneity (Q = 46.37, p < 0.01; I2 = 71.96%, 95%CI = [51.97%, 83.63], power = 0.967) but no evidence of publication bias (Egger’s z = −1.09, p = 0.274) (Fig. 3a). When separating the studies based on antipsychotic experience, we found a large effect of decreased D2/3 receptor availability exclusively in drug-on patients (d = −1.73, 95%CI = [−2.70, −0.76]) based on only two included studies5,49. There showed no evidence of change D2/3 level in drug-off (Fig. 3a) and drug naive patients (Supplementary Fig 5b). Subgroup analysis stratified by tracer type revealed consistently significant effect sizes with the use of [11C]FLB 457 (d = −0.35, 95%CI = [−0.63, −0.08]) but not significant for [11F] Fallypride (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Meta-regression did not find a significant association between reported thalamic D2/3 receptor availability and publication year, patients’ sex, and age, illness duration and severity of symptoms (Table 3 and Fig. 3b).

Substantia nigra, limbic, prefrontal, and temporal cortices

Based on all available studies, meta-analyses did not detect any significant abnormal D2/3 receptor availability in schizophrenia in either limbic cortex (Fig. 4a), substantia nigra (Fig. 4b), temporal cortex (Fig. 4c) or prefrontal cortex (Fig. 4d) and demonstrated moderate (temporal cortex I2 = 69.52%[39.19%, 84.72%]) to high heterogeneity (limbic cortex I2 = 81.47%[62.74%, 90.78%], substantia nigra I2 = 88.45% [77.41%, 94.10%]) but showed no evidence of publication bias in these regions across studies (p > 0.05). When separating the studies based on antipsychotic experience, we found a large effect of decreased D2/3 receptor availability exclusively in drug-on patients in limbic cortex (d = −1.40, 95%CI = [−1.88, −0.93]), substantia nigra (d = −1.51, 95%CI = [−2.04, −0.99]), and temporal cortex (d = −1.50, 95%CI = [−2.39, −0.61], although these findings are based on only two studies5,49. No significant effect was observed in drug-off patients (p > 0.05) in any of these regions. No significant effects were found in the subgroup analysis of tracers for the limbic cortex and temporal cortex (Supplementary Fig. 2b, 2c). Meta-regression did not find significant associations between the estimated D2/3 effects and publication year, patients’ sex, and age, illness duration and severity of symptoms in any of these regions (p > 0.05) (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 3-4).

Dopamine synthesis capacity (DSC)

The meta-analyses on DSC included 179 patients and 194 controls from 14 studies, resulting in 18 summary statistics, including 4 DN, 3 DF, 2 DN/DF, and 9 DO (Table 1).

Striatum

Meta-analysis based on all available studies did not find evidence of changed DSC in schizophrenia (d = 0.21, 95%CI = [-0.11, 0.53]) but demonstrated high heterogeneity (Q = 70.47, p < 0.01, I2 = 75.88%, 95%CI = [61.98%, 84.69%], power = 0.610) with no evidence of publication bias (Egger’s z = 1.01, p = 0.311, Fig. 5a, Table 2). When separating the studies based on antipsychotic experience, we found a small effect of increased striatal DSC exclusively in drug-off patients (d = 0.38, 95%CI = [0.06, 0.69], median power = 0.782), which was validated in drug-naive patients (d = 0.74, 95%CI = [0.40, 1.07]) (Supplementary Fig. 5c), but not in drug-on group (d = 0.06, 95%CI = [−0.49, 0.60]). Meta-regression analysis did not show evidence of reported DSC effects caused by publication year, patients’ sex, and age, illness duration and severity of symptoms (p > 0.05) (Table 3, Fig. 5b).

Limbic, prefrontal, and temporal cortices

Based on all available studies, meta-analyses did not detect evidence of abnormal DSC in schizophrenia in either the limbic cortex (Fig. 6a), prefrontal cortex (Fig. 6b), or temporal cortex (Fig. 6c). Sensitive analysis also demonstrated no evidence of abnormal DSC in drug-off patients. There were too few drug-on studies on DSC to permit meta-analyses, but all reported no abnormal DSC in the thalamus50, substantia nigra51,52, and limbic, prefrontal, and temporal cortices52. Finally, Meta-regression analysis did not show evidence of reported DSC effects caused by publication year, patients’ sex, age, illness duration and severity of symptoms (p > 0.05) (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 6).

D1 receptor availability

The meta-analyses on D1 included 92 patients and 113 controls from 6 studies, resulting in 8 summary statistics, including 4 DN, 2 DF, 1 DN/DF, and 1 DO (Table 1).

Meta-analyses based on all 6 studies did not find any evidence of abnormal D1 receptor availability in schizophrenia in any of the striatum, limbic cortex, prefrontal cortex, and temporal cortex (p > 0.05), although one DO study demonstrated reduced D1 availability in these regions53 (Fig. 7 and Table 2). Besides, the available studies demonstrated medium to high heterogeneity in these regions (I2: 70.06%–88.36%) and showed significant publication bias in the limbic cortex (Egger’s z = −3.63, p < 0.01), striatum (Egger’s z = −3.46, p < 0.01), prefrontal cortex (Egger’s z = −3.13, p < 0.01) and temporal cortex (Egger’s z = −3.16, p < 0.01). In only five of the drug-off studies, there also showed no evidence of abnormal D1 in schizophrenia in all regions (p > 0.05) and demonstrated medium to high heterogeneity in the limbic, prefrontal, and temporal cortices. Finally, Meta-regression showed a negative correlation between patients’ age and the estimated D1 effect of the prefrontal cortex (β = −0.12, p = 0.026) and striatum (β = −0.10, p < 0.01) (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 7). Moreover, meta-regression demonstrated significantly negative correlation between striatal D1 receptor availability and disease duration (z = −3.74, p = 0.0002) and symptomatic severity (z = −4.20, p = 0.00003), and between temporal D1 receptor availability and symptoms severity (z = −2.05, p = 0.04) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 8).

Dopamine transporter availability (DAT)

The meta-analyses on DAT included 46 patients and 59 controls from 4 studies with 1 DN, 2 DF/DO, 1 DN/DF, and 1 DO (Table 1). Meta-analyses based on the 4 studies did not find any evidence of abnormal DAT (d = 0.34, 95%CI = [−0.82, 1.51]) but high heterogeneity across studies in the striatum (Q = 28.57, p < 0.01, I2 = 89.50%, 95%CI for I2 = [75.92%, 95.42%], power = 0.402) (Table 2, Fig. 6d). Two studies reported significantly increased DAT availability in the thalamus in either drug-off54 or DF/DO patients55. One study reported increased DAT in limbic areas and substantia nigra (p < 0.01)55.

Discussion

Based on a meta-analysis of 48 state-of-the-art studies involving 692 patients and 730 controls, this study highlights significant heterogeneity in dopamine system dysfunction among individuals with schizophrenia in the following ways: first, there is considerable variability in both the direction (increased vs. decreased) and the involved brain regions of abnormalities across different dopamine subsystems; second, the influence of medication status varies significantly across these subsystems. Additionally, the study clarified that patients’ age, sex, disease duration and symptom severity selectively account for the reported heterogeneity of dopamine subsystem abnormalities. Finally, publication years may also bias the dopamine subsystem dysfunction.

This study highlights the increased D2/3 receptor availability and dopamine synthesis capacity in drug-naive and drug-free schizophrenia patients’ striatum34. Backing the dopamine increased hypothesis in schizophrenia’s pathophysiology1,2,3. Our results corroborate previous studies, namely that participants with greater dopamine synthesis capacity exhibit higher D2/3 receptor binding potential56. Moreover, we did not observe significant abnormal D2/3 receptor availability and dopamine synthesis capacity in drug-on patients. Notably, heterogeneity in D2/3 and DSC among drug-on patients were higher than those in drug-off patients, with both decreased57,58, normal59 and increased reported60. Among the four drug-on studies, one early study59 reported no difference in in striatal D2/3 receptor availability between drug-naive patients and healthy controls following immediate treatment with haloperidol (a first-generation antipsychotic). However, both groups showed a marked reduction in striatal uptake of [11C]NMSP. Two other studies observed reduced D2/3 receptor availability after long-term treatment with second-generation antipsychotics57,58. These findings suggest that antipsychotics, whether first- or second-generation, may relieve symptoms by reducing striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor availability and synthesis activity61. However, previous research indicates that the dopaminergic response differs between the two drug types. For example, long-term use of first-generation antipsychotics is associated with significant increases in striatal DSC and DAT expression, whereas second-generation antipsychotics have minimal effects on these presynaptic markers62,63. These differences likely contribute to the distinct side-effect profiles between different generation drugs62,63. Because there are relatively few PET studies directly comparing these drugs, more research is needed to clarify their different effects on the dopamine system.

It should be noted that one study reported increased D3 receptor binding in the globus pallidus (GP) using a selective D3 receptor affinity radiotracer [11C]-( + )-PHNO in patients long-term treated with second-generation antipsychotics60. This diversity could related to differential response of D2 and D3 receptors after antipsychotic treatment60. And the increased D3 receptor availability after treatment may be explained by antipsychotic-induced increased Bmax by intracellular mechanisms, such as regulation of G protein signaling64, D3 mRNA Up-regulation65. The variability might also stem from differences in medication dosages and individual sensitivities35, indicating that the striatum’s functional status could be a biomarker for personalized treatment, involving not only radiotracers32 but also other related measures such as functional connectivity66. Finally, consistent with previous meta-analyses33, we did not find any evidence of abnormal D1 receptor and DAT availability in the striatum of schizophrenia, except for one D1 study53 and one DAT study67 that reported decreased in drug-on chronic patients. We speculated the striatum of these two dopamine subsystems may not be the key pathophysiological target for schizophrenia development, and the reduced D1 and DAT availability in drug-on chronic patients should be verified in the future.

While previous research suggests widespread dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia beyond the striatum, including the mesolimbic68, mesocortical69, and thalamic-sensory pathways70. This study observed no abnormalities in drug-free patients. Instead, significantly reduced D2/3 receptor availability was observed in the thalamus, limbic areas, substantia nigra, and temporal lobe exclusively in drug-on patients, aligning with previous meta-analyses42. Besides, reduced D1 receptor availability was noted in similar regions for medicated individuals53. This reduction in D2/3 and D1 receptor availability outside the striatum in medicated patients might be an “overcorrection” effect of antipsychotics, potentially explaining the shift from predominantly positive symptoms in early-stage schizophrenia to more prominent negative symptoms in chronic phases71. These findings suggest that the mesolimbic and mesocortical hypotheses of schizophrenia may be related to antipsychotic hypodopaminergic of these pathways, which was supported by neuroimaging studies showing gray matter atrophy and functional dysconnectivity in the thalamic-sensory72,limbic73 and prefrontal subnetworks in chronic schizophrenia74.

The above findings reveal that antipsychotic medications exert complex effects on the dopamine subsystems across brain regions in schizophrenia. One possible reason is that mainstream antipsychotic drugs neither exclusively target a specific dopamine subsystem nor a specific brain region75 which may alleviate positive symptoms but potentially induce side effects such as blunted affect, reduced motivation, and social withdrawal74. Such findings highlight the necessity for developing targeted therapies that precisely adjust dopamine subsystems in specific brain regions, minimizing side effects and improving treatment outcomes.

We also found that the effect sizes obtained from different tracers vary significantly, demonstrating a high degree of overall heterogeneity for striatal D2/3 availability results (I2 = 85.69%). For example, early studies using [11C]NMSP demonstrated stronger effect but higher heterogeneity across studies, likely due to its complex and condition-dependent binding properties59,76,77. In contrast, studies using [11C]Raclopride demonstrate much lower heterogeneity and more consistent measurements, though they typically report smaller effect sizes. For instance, [11C]FLB 457 has exceptionally high affinity outside the striatum, particularly in the thalamus78, and has proven reliable in both cortical and thalamic regions79,80,81. Future studies should standardize tracer selection and continue validating tracers across different brain regions and populations to reduce heterogeneity and improve measurement consistency.

Except for drug usage, this meta-analysis also revealed that patients’ demographic and clinical conditions, including age, sex, disease duration and symptom severity, contribute selectively to the variability in dopamine abnormalities seen in schizophrenia. Notably, a higher proportion of male patients correlates with increased striatal D2/3 receptor availability. Previous studies have reported diverse morbidity and symptom prevalence82, genetic risk83, and brain damage patterns84,85 between male and female patients. Moreover, early studies demonstrated a significant interaction between dopamine receptor D2 gene variants and sex on cognitive control86, and males had generally higher D2 receptor affinity than women in the striatum87. In combination with more severe dopamine dysfunction reported in male schizophrenia88,89. This gender-specific observation underscores important neurobiological differences in schizophrenia. Additionally, we found older patients exhibiting severe striatal and prefrontal D1 receptors deficits. Age-dependent decline of dopamine D1 receptors had been reported in these regions90,91,92. While limited studies prevent distinguishing drug effects, this study might suggest a faster decline of striatum and prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors with aging in schizophrenia. Additionally, the lack of significant findings for striatal and temporal D1 receptor availability in our meta-analysis can be partly explained by heterogeneity in illness duration and symptom severity. Specifically, we found that longer illness duration is associated with greater reductions in striatal D1 availability, likely due to the accumulation of neuropathological changes and increasing disruption of the dopamine system over time—factors that can introduce confounders and bias in pooled analyses. Finally, higher symptom severity is linked to further decreases in striatal and temporal D1 receptor availability, as severity reflects the extent of underlying neural and neurotransmitter dysfunction, making consistent measurement and integration of results more challenging. Collectively, these sources of heterogeneity—including sex, age, illness duration, and symptom severity—limit the accuracy with which we can characterize the relationship between dopamine markers and schizophrenia. Future research should address these issues by carefully matching participants by demographic and clinical characteristics and using standardized analytic approaches. Comprehensive and stratified study designs—such as lifespan normative models93—will help clarify the roles of age and sex in disease progression and treatment response, leading to a more reliable understanding of schizophrenia’s pathophysiology and improving clinical care.

We observed a significant negative correlation between year of publication and the estimated effect size for striatal D2/D3 receptor availability in schizophrenia patients: studies from the 1990s frequently reported marked hyper-availability, whereas more recent research shows much smaller elevations. Notably, studies published before 1994, particularly those using the radiotracer [11C]NMSP, reported dramatically higher effect sizes—with Cohen’s d reaching up to 2.97 and an average effect size of 1.52 (range: 0.57–2.47). This is substantially greater than the effect sizes observed in studies using later tracers such as [11C]Raclopride (ES: 0.16 [–0.11, 0.43]) and [11F]Fallypride (ES: 0.18 [–0.19, 0.55]). Thus, radiotracer may be an important factor for publication bias. Besides, differences in statistical methods, patient demographics, and clinical characteristics may also partly contribute to the publication bias. Such bias reduces statistical power and distorts scientific conclusions, highlighting the need for reproducibility strategies, including preregistration, data sharing, and transparent reporting94.

This meta-analytic study faces several methodological concerns. First, the prevailing PET studies only report region-wise statistics with varying region definitions, requiring us to aggregate data into six major areas, potentially reducing spatial precision. An image-based meta-analysis with voxel-wise statistics is preferable95. Authors are encouraged to share unthresholded PET/SPECT maps in public repositories like Neurosynth (https://neurosynth.org/) and Neurovault (https://neurovault.org/). Second, this study focuses on case-control statistics under resting-state conditions, but dopamine receptor availability was also reported to change under specific tasks, indicating condition-dependent activity may also contribute to the reported heterogeneity of dopamine dysfunction27. More research on this issue is needed due to limited studies on this effect. Third, we were unable to perform stratified meta-regression separately on drug-off and drug-on patients due to the insufficient number of studies. Fourth, our power analysis demonstrates that sample size is a critical driver of heterogeneity, and thus expanding the sample is a current research priority. Future studies should be anchored in large-scale cohorts. Finally, given that patient age and medication use may confound the experimental results, along with the tracer-specific nature of PET imaging, we were unable to conduct integrated analyses across dopamine subsystems. We hope future studies with better controlled variables may uncover potential pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the disorder.

Methods

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)96 were followed in conducting this study.

Search and selection strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed and Web of Science databases using the search terms [(“PET” OR “Positron emission tomography”) AND (“schizophrenia” OR “schizophrenic”) AND (“dopamine” OR “dopaminergic”)] to identify relevant studies on the research topic on January 2, 2025, without any specified time constraints for publication dates. Additionally, we manually searched the reference lists of articles in previous reviews to capture any relevant studies that may have been missed in the searches. While all included literature was in English, no language restrictions were applied. Furthermore, we applied additional screening criteria to select studies if they: (1) were original, peer-reviewed articles; (2) involved DSM/ICD-diagnosed schizophrenia patients and matched controls; (3) utilized PET imaging for comparison; (4) provided valid summary statistics to enable the derivation of Cohen’s d; and (5) For studies with overlapping samples, adjudication was performed by prioritizing those with either more comprehensive participant characteristics or larger sample sizes. Cross-examination was specifically conducted for articles published by the same research team to ensure complete independence of all included study populations.

Data extraction and harmonization

Two reviewers (Z.Z. and X.L.) extracted data independently using a standardized form. The primary analysis was a difference in dopamine PET imaging between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. We also obtained the following information regarding these studies: authors, journals, year of publication, drug history, gender, age, PET radiotracers, measures, and dopamine subsystems, illness duration, symptom severity. We selected the Simplified Reference Tissue Model (SRTM) as the preferred option when multiple quantification methods are available in a study.

Before conducting meta-analyses, we first converted each summary statistic result for each study into a standard effect size, Cohen’s d, and its standard error (SEd), regardless of the statistical measures used, such as mean (μ) ± standard deviation (SD) or T/P values plus sample size. Specifically, for result reporting the mean and SD for each group, the Cohen’s d, and its standard error (\({{SE}}_{d}\)) are calculated with:

Where:

\({N}_{{SCZ}}\) and \({N}_{{HC}}\) represent the number of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls, respectively. SDpooled is a statistical measure used to combine the standard deviations from two or more groups into a single estimate of variability.

For studies only reporting t values and sample size for each group, the Cohen’s d, and \({{SE}}_{d}\) are calculated with:

Where:

Because the vast majority of PET studies only reported region-of-interest (ROI) statistics, and the definition of ROIs are diverse across studies, we further standardized the ROIs by aggregating all statistical results into the same framework containing six Regions: striatum, thalamus, substantia nigra, limbic region, prefrontal cortex, and temporal cortex(Supplement Table 1). Results with more than one subfield within each ROI were aggregated by calculating the grand mean of the effect size measure in a certain study using R statistical programming language version 4.2.3 with the package “Mad” (https://cran.r-project.org/web//packages/MAd/MAd.pdf).

Statistics

For each PET tracer and each ROI, a random-effects meta-analysis model97 with a restricted maximum likelihood estimator (RMLE)98 was conducted using the aggregated Cohen’s d and \({{SE}}_{d}\) of all available studies as inputs for the “meta” package99. We estimated the heterogeneity using I² which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance:

Where Q is Cochran’s heterogeneity statistic, and df is the degrees of freedom. Negative values of I2 are put equal to zero so that I2 lies between 0% and 100%. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity and larger values show increasing heterogeneity100. To assess the statistical power of our meta-analysis and evaluate the robustness of all findings, we used “pwr” package in R to conduct a post hoc power analysis based on the pooled effect size.

Sensitivity analyses were performed when the number of studies in the subset was no fewer than five. First, we divided studies into two subgroups based on the patient’s antipsychotic history: drug-on (DO), Including patients who received antipsychotic treatment during the PET scan included in the study, and drug-off, including those who were drug-naive (DN) or drug-free (DF) who discontinued medication before the study. Second, we performed meta-analyses on studies containing only drug-naive patients. Third, funnel plots and Egger’ s tests were applied to assess the extent of publication bias101. Fourth, Additional subgroup analyses were performed based on the type of tracer used in the D2 study due to the variety of tracers employed in D2 research. Finally, potential factors that may explain the heterogeneity of schizophrenia dopamine subsystem dysfunctions, including publication year, patients’ gender, and patients’ age, illness duration of patients, and severity of patients symptom were evaluated using meta-regression, When analyzing symptom severity, due to heterogeneity in assessment scales across studies, we restricted our analysis to studies employing either the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). For studies using BPRS, scores were converted to PANSS equivalents using Equipercentile linked conversion methods102.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are derived from previously published literature, as detailed in Table 1. Statistical data can be found within this paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Meltzer, H. Y. & Stahl, S. M. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr. Bull. 2, 19–76 (1976).

Howes, O. D., McCutcheon, R., Owen, M. J. & Murray, R. M. The Role of Genes, Stress, and Dopamine in the Development of Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 9–20 (2017).

Seeman, M. V. History of the dopamine hypothesis of antipsychotic action. World J. Psychiatry 11, 355–364 (2021).

Seeman, P. Brain dopamine receptors. Pharm. Rev. 32, 229–313 (1980).

Slifstein, M. et al. Deficits in prefrontal cortical and extrastriatal dopamine release in schizophrenia: a positron emission tomographic functional magnetic resonance imaging study. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 316–324 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. Structural covariances of prefrontal subregions selectively associate with dopamine-related gene coexpression and schizophrenia. Cereb. Cortex 33, 8035–8045 (2023).

McCutcheon, R. A., Krystal, J. H. & Howes, O. D. Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: biology, symptoms and treatment. World Psychiatry 19, 15–33 (2020).

Lee, C. S. et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic evidence for compensatory changes in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol.: Off. J. Am. Neurol. Assoc. Child Neurol. Soc. 47, 493–503 (2000).

Daubner, S. C., Le, T. & Wang, S. Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch. Biochem Biophys. 508, 1–12 (2011).

Bhatia, A., Lenchner, J. R. & Saadabadi, A. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025).

Li, Y. et al. Dopamine reuptake and inhibitory mechanisms in human dopamine transporter. Nature 632, 686–694 (2024).

Xu, H. & Yang, F. The interplay of dopamine metabolism abnormalities and mitochondrial defects in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 464 (2022).

Grace, A. A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 524–532 (2016).

Mackay, A. V. et al. Increased brain dopamine and dopamine receptors in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 991–997 (1982).

Lee, T. & Seeman, P. Elevation of brain neuroleptic/dopamine receptors in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 137, 191–197 (1980).

Bird, E. D., Spokes, E. G. & Iversen, L. L. Increased dopamine concentration in limbic areas of brain from patients dying with schizophrenia. Brain 102, 347–360 (1979).

Widerlöv, E. A critical appraisal of CSF monoamine metabolite studies in schizophrenia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 537, 309–323 (1988).

Davis, K. L., Kahn, R. S., Ko, G. & Davidson, M. Dopamine in schizophrenia: a review and reconceptualization. Am. J. Psychiatry 148, 1474–1486 (1991).

Lyon, G. J. et al. Presynaptic regulation of dopamine transmission in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 37, 108–117 (2011).

Tan, J. et al. Progress in the application of molecular imaging in psychiatric disorders. Psychoradiology https://doi.org/10.1093/psyrad/kkad020 (2023).

Hutton, B. F. The origins of SPECT and SPECT/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 41, S3–S16 (2014).

Elsinga, P. H., Hatano, K. & Ishiwata, K. PET tracers for imaging of the dopaminergic system. Curr. Med Chem. 13, 2139–2153 (2006).

McCutcheon, R. A., Abi-Dargham, A. & Howes, O. D. Schizophrenia, dopamine and the striatum: from biology to symptoms. Trends Neurosci. 42, 205–220 (2019).

Frankle, W. G. et al. Amphetamine-induced striatal dopamine release measured with an agonist radiotracer in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 707–714 (2018).

Graff-Guerrero, A. et al. The dopamine D2 receptors in high-affinity state and D3 receptors in schizophrenia: a clinical [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 1078–1086 (2009).

Okubo, Y. et al. Decreased prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors in schizophrenia revealed by PET. Nature 385, 634–636 (1997).

Abi-Dargham, A. Probing cortical dopamine function in schizophrenia: what can D1 receptors tell us?. World Psychiatry 2, 166–171 (2003).

Karlsson, P., Farde, L., Halldin, C. & Sedvall, G. PET study of D(1) dopamine receptor binding in neuroleptic-naive patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 761–767 (2002).

Jauhar, S. et al. A Test of the Transdiagnostic Dopamine Hypothesis of Psychosis Using Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging in Bipolar Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia. JAMA psychiatry 74, 1206–1213 (2017).

Avram, M. et al. Reduced striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in patients with schizophrenia during remission of positive symptoms. Brain 142, 1813–1826 (2019).

Kestler, L. P., Walker, E. & Vega, E. M. Dopamine receptors in the brains of schizophrenia patients: a meta-analysis of the findings. Behav. Pharm. 12, 355–371 (2001).

Yilmaz, Z. et al. Antipsychotics, dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy and clinical improvement in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res 140, 214–220 (2012).

Fusar-Poli, P. & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Striatal presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia, Part I: meta-analysis of dopamine active transporter (DAT) density. Schizophr. Bull. 39, 22–32 (2013).

Fusar-Poli, P. & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Striatal presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia, part II: meta-analysis of [(18)F/(11)C]-DOPA PET studies. Schizophr. Bull. 39, 33–42 (2013).

Lako, I. M., van den Heuvel, E. R., Knegtering, H., Bruggeman, R. & Taxis, K. Estimating dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy for doses of 8 antipsychotics: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 33, 675–681 (2013).

McCutcheon, R., Beck, K., Jauhar, S. & Howes, O. D. Defining the locus of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and test of the mesolimbic hypothesis. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 1301–1311 (2018).

Brugger, S. P. et al. Heterogeneity of striatal dopamine function in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of variance. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 215–224 (2020).

Caravaggio, F. et al. What proportion of striatal D2 receptors are occupied by endogenous dopamine at baseline? A meta-analysis with implications for understanding antipsychotic occupancy. Neuropharmacology 163, 107591 (2020).

Plaven-Sigray, P. et al. Thalamic dopamine D2-receptor availability in schizophrenia: a study on antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis and a meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 1233–1240 (2022).

Stone, J. M., Davis, J. M., Leucht, S. & Pilowsky, L. S. Cortical dopamine D2/D3 receptors are a common site of action for antipsychotic drugs-an original patient data meta-analysis of the SPECT and PET in vivo receptor imaging literature. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 789–797 (2009).

Howes, O. D. et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 776–786 (2012).

Kambeitz, J., Abi-Dargham, A., Kapur, S. & Howes, O. D. Alterations in cortical and extrastriatal subcortical dopamine function in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of imaging studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 204, 420–429 (2014).

Larry, T. et al. Striatal dopamine D2 receptor quantification and superior temporal gyrus: Volume determination in 14 chronic schizophrenic subjects. Psychiatry Res.: Neuroimaging 67, 155–158 (1996).

Howes, O. D. et al. Midbrain dopamine function in schizophrenia and depression: a post-mortem and positron emission tomographic imaging study. Brain 136, 3242–3251 (2013).

Fumihiko, Y. et al. Abnormal effective connectivity of dopamine D2 receptor binding in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res.: Neuroimaging 138, 197–207 (2005).

Avram, M. et al. Aberrant striatal dopamine links topographically with cortico-thalamic dysconnectivity in schizophrenia. Brain 143, 3495–3505 (2020).

Poels, E. M., Girgis, R. R., Thompson, J. L., Slifstein, M. & Abi-Dargham, A. In vivo binding of the dopamine-1 receptor PET tracers [¹¹C]NNC112 and [¹¹C]SCH23390: a comparison study in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol. ((Berl.)) 228, 167–174 (2013).

Demjaha, A. et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in schizophrenia associated with elevated glutamate levels but normal dopamine function. Biol. Psychiatry 75, e11–e13 (2014).

Suhara, T. et al. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor binding in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 25–30 (2002).

Nozaki, S. et al. Regional dopamine synthesis in patients with schizophrenia using L-[beta-11C]DOPA PET. Schizophr. Res 108, 78–84 (2009)..

Kumakura, Y. et al. Elevated [18F]fluorodopamine turnover in brain of patients with schizophrenia: an [18F]fluorodopa/positron emission tomography study. J. Neurosci. 27, 8080–8087 (2007).

Elkashef, A. M. et al. 6-(18)F-DOPA PET study in patients with schizophrenia. Positron emission tomography. Psychiatry Res 100, 1–11 (2000).

Kosaka, J. et al. Decreased binding of [11C]NNC112 and [11C]SCH23390 in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Life Sci. 86, 814–818 (2010).

Arakawa, R. et al. Increase in thalamic binding of [(11)C]PE2I in patients with schizophrenia: a positron emission tomography study of dopamine transporter. J. Psychiatr. Res 43, 1219–1223 (2009).

Artiges, E. et al. Striatal and Extrastriatal Dopamine Transporter Availability in Schizophrenia and Its Clinical Correlates: A Voxel-Based and High-Resolution PET Study. Schizophr. Bull. 43, 1134–1142 (2017).

Berry, A. S. et al. Dopamine Synthesis Capacity is Associated with D2/3 Receptor Binding but Not Dopamine Release. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 1201–1211 (2018).

Grunder, G. et al. The striatal and extrastriatal D2/D3 receptor-binding profile of clozapine in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 1027–1035 (2006).

Joo, Y. H. et al. The relationship between excitement symptom severity and extrastriatal dopamine D(2/3) receptor availability in patients with schizophrenia: a high-resolution PET study with [(18)F]fallypride. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 268, 529–540 (2018).

Nordstrom, A. L., Farde, L., Eriksson, L. & Halldin, C. No elevated D2 dopamine receptors in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients revealed by positron emission tomography and [11C]N-methylspiperone. Psychiatry Res 61, 67–83 (1995).

Graff-Guerrero, A. et al. The effect of antipsychotics on the high-affinity state of D2 and D3 receptors: a positron emission tomography study With [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 606–615 (2009).

Nord, M. & Farde, L. Antipsychotic occupancy of dopamine receptors in schizophrenia. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 17, 97–103 (2011).

Laruelle, M. et al. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9235–9240 (1996).

Kegeles, L. S. et al. Increased synaptic dopamine function in associative regions of the striatum in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 231–239 (2010).

Erdely, H. A., Tamminga, C. A., Roberts, R. C. & Vogel, M. W. Regional alterations in RGS4 protein in schizophrenia. Synapse 59, 472–479 (2006).

Wang, W. et al. Up-regulation of D3 dopamine receptor mRNA by neuroleptics. Synapse 23, 232–235 (1996).

Li, A. et al. A neuroimaging biomarker for striatal dysfunction in schizophrenia. Nat. Med 26, 558–565 (2020).

Laakso, A. et al. Decreased striatal dopamine transporter binding in vivo in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 52, 115–120 (2001).

McCutcheon, R. A. et al. Mesolimbic Dopamine Function Is Related to Salience Network Connectivity: An Integrative Positron Emission Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Study. Biol. Psychiatry 85, 368–378 (2019).

Weele, C. M. V., Siciliano, C. A. & Tye, K. M. Dopamine tunes prefrontal outputs to orchestrate aversive processing. Brain Res 1713, 16–31 (2019).

Oke, A. F. & Adams, R. N. Elevated thalamic dopamine: possible link to sensory dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 589–604 (1987).

Wang, Z. et al. Comparison of first-episode and chronic patients diagnosed with schizophrenia: symptoms and childhood trauma. Early Inter. Psychiatry 7, 23–30 (2013).

Alemán-Gómez, Y. et al. Partial-volume modeling reveals reduced gray matter in specific thalamic nuclei early in the time course of psychosis and chronic schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 4041–4061 (2020).

Millman, Z. B. et al. Auditory hallucinations, childhood sexual abuse, and limbic gray matter volume in a transdiagnostic sample of people with psychosis. Schizophrenia ((Heidelb.)) 8, 118 (2022).

Kim, D. I. et al. Dysregulation of working memory and default-mode networks in schizophrenia using independent component analysis, an fBIRN and MCIC study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 3795–3811 (2009).

Jones, H. M. & Pilowsky, L. S. Dopamine and antipsychotic drug action revisited. Br. J. Psychiatry 181, 271–275 (2002).

Rosa-Neto, P. et al. MDMA-evoked changes in [11C]raclopride and [11C]NMSP binding in living pig brain. Synapse 53, 222–233 (2004).

Tian, M. et al. PET imaging reveals brain functional changes in internet gaming disorder. Eur. J. Nucl. Med Mol. Imaging 41, 1388–1397 (2014).

Leung, K. in Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database (MICAD) (National Center for Biotechnology Information (US), 2004).

Sudo, Y. et al. Reproducibility of [11C] FLB 457 binding in extrastriatal regions. Nucl. Med. Commun. 22, 1215–1221 (2001).

Vilkman, H. et al. Measurement of extrastriatal D 2-like receptor binding with [11 C] FLB 457–a test-retest analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 27, 1666–1673 (2000).

Narendran, R., Himes, M. & Mason, N. S. Reproducibility of post-amphetamine [11C] FLB 457 binding to cortical D2/3 receptors. PLoS One 8, e76905 (2013).

Ochoa, S., Usall, J., Cobo, J., Labad, X. & Kulkarni, J. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. Schizophr. Res Treat. 2012, 916198 (2012).

Goldstein, J. M., Cherkerzian, S., Tsuang, M. T. & Petryshen, T. L. Sex differences in the genetic risk for schizophrenia: history of the evidence for sex-specific and sex-dependent effects. Am. J. Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr. Genet 162B, 698–710 (2013).

Frazier, J. A. et al. Diagnostic and sex effects on limbic volumes in early-onset bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 37–46 (2008).

Mendrek, A. & Mancini-Marie, A. Sex/gender differences in the brain and cognition in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 67, 57–78 (2016).

Gurvich, C. & Rossell, S. L. Dopamine and cognitive control: sex-by-genotype interactions influence the capacity to switch attention. Behav. Brain Res 281, 96–101 (2015).

Pohjalainen, T., Rinne, J. O., Nagren, K., Syvalahti, E. & Hietala, J. Sex differences in the striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in vivo. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 768–773 (1998).

Williams, O. O. F., Coppolino, M., George, S. R. & Perreault, M. L. Sex differences in dopamine receptors and relevance to neuropsychiatric disorders. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091199 (2021).

Godar, S. C. & Bortolato, M. Gene-sex interactions in schizophrenia: focus on dopamine neurotransmission. Front Behav. Neurosci. 8, 71 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Age-dependent decline of dopamine D1 receptors in human brain: A PET study. Synapse 30, 56–61 (1998).

Johansson, J. et al. Biphasic patterns of age-related differences in dopamine D1 receptors across the adult lifespan. Cell Rep. 42, 113107 (2023).

Backman, L. et al. Dopamine D(1) receptors and age differences in brain activation during working memory. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 1849–1856 (2011).

Sun, L. et al. Population-specific brain charts reveal Chinese-Western differences in neurodevelopmental trajectories. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.17.659820 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Publication bias impacts on effect size, statistical power, and magnitude (Type M) and sign (Type S) errors in ecology and evolutionary biology. BMC Biol. 21, 71 (2023).

Salimi-Khorshidi, G., Smith, S. M., Keltner, J. R., Wager, T. D. & Nichols, T. E. Meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: a comparison of image-based and coordinate-based pooling of studies. Neuroimage 45, 810–823 (2009).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Trikalinos, T. A., Salanti, G., Zintzaras, E. & Ioannidis, J. P. Meta-analysis methods. Adv. Genet 60, 311–334 (2008).

Raudenbush, S. Analysing effect sizes: random effects models. In: Cooper, H.; Hedges, L. V.;Valentine, J. C., editors. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2nd ed.. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 2009. 295-315.

Schwarzer G., C. J. Carpenter, Rücker G. Meta-Analysis with R. R. 2015; 217–236.

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 327, 557–560 (2003).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 315, 629–634 (1997).

Leucht, S., Rothe, P., Davis, J. M. & Engel, R. R. Equipercentile linking of the BPRS and the PANSS. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 956–959 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Funding This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82472052 [W.Q.], 81971599 [W.Q.], 82430063 [C.Y.], 82030053 [C.Y.]), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1314300 [C.Y.]), TEDA-UCB Science Innovation Award [W.Q.], Tianjin Key Medical Discipline Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-3-008C[C.Y.]) and Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (19JCYBJC25100 [W.Q.]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. and Z.Z. initially designed the study. Z.Z. led, and all authors were involved in the conceptualization and in refining of the methods. Z.Z. and X.L. ran and double checked the searches, screened the papers and extracted the original data. Z.Z. and Q.W. drafted the manuscript, with all authors then providing significant contributions. Z.Z. and X.L. are joint first authors on this paper because of the significant time and effort they have jointly spent on designing, running and finalizing the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Z., Li, X., Xie, Y. et al. Resolving the heterogeneity of dopamine subsystems dysfunction in schizophrenia: a PET meta-analysis. Schizophr 11, 139 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00684-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00684-0