Abstract

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are frequent in schizophrenia (SCZ) and have been linked to cognitive impairment and low-grade inflammation. In this cross-sectional study of adults with DSM-5 SCZ (N = 218; SCZ = 103, SCZ+MetS = 62, SCZ + DM = 53), we quantified interleukine-6 (IL-6) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and evaluated their associations with Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) cognitive domains and routine metabolic measures using multivariable models. Results revealed that SCZ + DM showed lower attention and delayed memory scores than SCZ and SCZ+MetS. No between-group differences were observed for immediate memory, visuospatial function, or language. IL-6 was highest in SCZ + DM, intermediate in SCZ + MetS, and lowest in SCZ. CRP did not differ significantly between groups. Across the cohort, higher IL-6 and fasting glucose were associated with lower attention and delayed memory. We conclude that DM status and higher IL-6 were most consistently associated with poorer attention and delayed memory in SCZ. Given the cross-sectional design, these findings reflect associations and may be influenced by treatment and residual confounding. Longitudinal studies with broader cytokine panels are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a lifelong, heterogeneous mental disorder characterized by a diverse constellation of positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms1. Recent research has established that cognitive dysfunctions are a core feature of the disease, significantly impeding daily functioning and deteriorating quality of life and prognosis for patients1,2,3.

More than one-third of individuals with SCZ suffer from comorbid metabolic syndrome (MetS), which represents a significant risk factor for the development of various cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, consequently leading to an increased mortality rate4. Additionally, MetS is associated with cognitive impairment in both the general population and individuals with SCZ5,6.

The investigation of the relationship between MetS and SCZ has gained significant attention in recent years. Multiple genetic studies have investigated the potential link between the two diseases; however, they have yielded contradictory results7,8,9.

Contradictory genetic studies raise the possibility that various environmental factors may play a role in the higher prevalence of MetS among individuals with SCZ7. Additionally, SCZ patients are often characterized by a sedentary lifestyle, poor nutrition, and substance use, which further increase the risk of developing metabolic disorders10.

The involvement of inflammation and immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of SCZ has been extensively studied for several decades. Neurodevelopmental and inflammatory hypotheses emphasize the role of immune system-related elements, such as microglia, major histocompatibility complex (MHC), and complement component 4 (C4) in the context of dysfunctional synaptic pruning11. Moreover, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines have been detected in SCZ, both in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), suggesting their potential role in its pathophysiology12,13. Pathological peripheral inflammatory processes may potentially induce neuroinflammation, leading to structural changes in the brain and thus contributing to cognitive dysfunction. As inflammatory processes also contribute to the pathogenesis of MetS, and the relationship between inflammation and MetS is bidirectional, the investigation of these factors is of great importance14.

Notably, recent studies on the gut-brain axis also highlight the potential role of immune dysregulation mechanisms, disturbances in metabolism, and the neuroendocrine system in the pathomechanism of cognitive impairments observed in SCZ15.

Furthermore, a challenge in the treatment of SCZ is that the most commonly used medications, second-generation or atypical antipsychotics, have minimal effects on cognitive dysfunctions. Yet, they often cause metabolic side effects, leading to the development of MetS16,17. However, it should be noted that a meta-analysis has confirmed that metabolic dysregulations are more prevalent among drug-naive, first-episode psychotic patients who have not yet received antipsychotic treatment compared to the general population18.

Although inflammation and metabolic dysregulation have both been implicated in schizophrenia, it remains unclear how circulating IL-6 and CRP track cognitive performance across clinically relevant comorbidity strata. We therefore examined the association between IL-6/CRP, metabolic indices, and RBANS domains in three groups (SCZ, SCZ+MetS, and SCZ + DM).

We formulated the following hypotheses: First, patients with DM would exhibit the worst cognitive dysfunctions among the three groups. Second, fasting blood glucose levels would negatively correlate with cognitive functions. Third, SCZ + DM and SCZ+MetS groups would exhibit the highest levels of inflammatory markers. Fourth, elevated inflammatory markers would correlate with cognitive dysfunctions.

Methods

Participants and psychiatric assessment

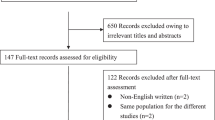

Patients with SCZ (N = 218) were recruited from three psychiatric centers in Hungary (National Institute of Psychiatry, Budapest; University of Szeged, Szeged; Bács-Kiskun County Hospital, Kecskemét; recruitment period: 2012–2023). Inclusion criteria were as follows: fulfilling the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), criteria for SCZ19; age between 18 and 65 years; clinical state stabilized with antipsychotic medications; no history of neurological disorders or head injury; and no substance misuse within the past six months. The clinical documentation and complete medical history were available for all patients.

Patients with SCZ received the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-520, administered by trained clinical psychologists or psychiatrists. We used the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which is a widely used instrument administered by clinicians21. It comprises 30 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, which are grouped into three subscales: positive symptoms (7 items, e.g. delusions, hallucinatory behavior, and conceptual disorganization), negative symptoms (7 items, e.g., blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and passive/apathetic social withdrawal), and general psychopathology (16 items; e.g., anxiety, tension, hostility, and depression). Scores are derived from structured clinical interviews and direct observations, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The clinical and demographic parameters are summarized in Table 1.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the National Medical Research Council (ETT-TUKEB 18814, Budapest, Hungary). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Metabolic status and laboratory measures

We assessed the metabolic status of the participants. Sixty-two patients were diagnosed with MetS based on the criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III), requiring at least three out of five components: “(1) abdominal obesity: waist circumference greater than 102 cm in men or 88 cm in women; (2) elevated triglyceride levels: 1.7 mmol/L or higher; (3) reduced HDL cholesterol levels: less than 1.03 mmol/L in men and less than 1.29 mmol/L in women; (4) elevated blood pressure: systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or higher, diastolic blood pressure of 85 mm Hg or higher; (5) elevated fasting glucose: fasting plasma glucose levels of 5.6 mmol/L) or higher.”22

Another group of 53 patients received a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM) in addition to metabolic syndrome (MetS) without DM. The three groups (SCZ patients without MetS or DM, SCZ+MetS, and SCZ + DM) were characterized separately by laboratory measures of lipid homeostasis (triglycerides [TG], high-density lipoprotein [HDL], low-density lipoprotein [LDL]) and glucose homeostasis (fasting blood glucose [FBG], hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c]). Additionally, we measured levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) as previously described. The diagnosis of MetS and DM was made immediately before testing. Therefore, the patients did not receive medications for MetS and DM.

Cognitive assessment

The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) was administered to evaluate cognitive function. The RBANS is a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery designed to assess multiple domains of cognition within ~20–30 min of test administration. It consists of 12 subtests, organized into five primary index scores23.

-

1.

Attention: Measured with the digit span and coding subtests, this index captures aspects of sustained attention, processing speed, and working memory.

-

2.

Immediate Memory: This index measures the ability to encode and recall information immediately after it is presented. It is assessed via the list learning and story memory subtests.

-

3.

Delayed Memory: This index assesses the retention and retrieval of information after a delay based on the list recall, list recognition, story recall, and figure recall subtests.

-

4.

Visuospatial/Constructional functions: This index measures visual perception and constructional praxis. It is evaluated using the figure copy and line orientation subtests.

-

5.

Language: This index, derived from the picture naming and semantic fluency subtests, reflects language production and semantic access.

All subtests were administered according to the standard protocol by trained examiners. Raw scores were obtained and converted into age-adjusted scaled scores using published normative data. Subsequently, these scaled scores were used to calculate the five index scores (normative mean: 100, SD = 15). The RBANS was extensively validated and demonstrated high reliability and sensitivity in detecting cognitive impairments23.

Data analysis

We used Spotfire Data Science Workbench 14.2.0 (Tibco), JASP 0.19.1, and the R-package for statistical analysis.

After checking the normality of data distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) of all variables on a group basis, we conducted multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with the group as between-subjects factors (SCZ, SCZ+MetS, and SCZ + DM) and the RBANS domains as within-subjects factors (attention, immediate memory, delayed memory, visuospatial function, and language). The dependent measure was the RBANS scores for each domain. We determined the effect size (η2). For the Bayesian interpretation of the p-value, we calculated the Vovk-Selke p-ratios (VSR) (VSR > 1: evidence against the null hypothesis; VS-ratio > 10: the evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis is strong; VS-ratio < 1: the null hypothesis is more supported). If the sphericity or homogeneity of variance was violated, Huynh-Feldt or Welch corrections were applied, respectively. For post-hoc comparisons, Holm-corrected t-tests were calculated. Demographics, clinical scales, and laboratory parameters were entered into one-way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc tests. Where appropriate, Cohen’s effect size values were also calculated.

To determine the relationship between cognitive deficits (RBANS scores) and laboratory parameters (IL-6, FBG, HbA1c, TG, HDL, and LDL), we used multiple regression analysis, adjusted for age, sex, education, clinical symptoms, social functioning, chlorpromazine-equivalent dose of antipsychotics, and duration of illness. We also calculated the strength and direction of the relationship between cognitive scores and laboratory measures using Pearson’s product-moment coefficients with VSR for Bayesian statistics. To contextualize subgroup precision, we report minimum detectable within-group correlations (two-sided α = 0.05, 80% power): r = 0.38 (SCZ + DM, n = 53), r = 0.35 (SCZ+MetS, n = 62), r = 0.27 (SCZ, n = 103).

Results

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and laboratory measures

Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics of the three SCZ groups (SCZ, SCZ+MetS, and SCZ + DM). We found no significant differences in age, education, sex, PANSS, illness duration, or general functioning. Patients with SCZ+MetS and SCZ + DM exhibited higher BMIs and WHRs than those with SCZ, but there was no significant difference between SCZ+MetS and SCZ + DM (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the laboratory measures. Patients with SCZ+MetS and SCZ + DM displayed higher TG, LDL, and lower HDL than patients with SCZ, but there was no significant difference between SCZ+MetS and SCZ + DM. In terms of FBG, the highest level was measured in SCZ + DM, followed by SCZ+MetS and SCZ. HbA1c was significantly increased in SCZ + DM relative to SCZ+MetS and SCZ. IL-6 was significantly increased in SCZ + DM relative to SCZ and SCZ+MetS, with no significant difference between SCZ and SCZ+MetS. Finally, there were no significant between-group differences in CRP (Table 2).

Cognitive performance

The RBANS results are shown in Table 3. The MANOVA performed on the RBANS domain scores revealed a significant main effect of group (F(2,115) = 18.0, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03, VSR = 372010.54) and RBANS domain scores (F(3.9, 838.3) = 3.47, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01, VSR = 8.97). The two-way interaction between the group and RBANS domain scores was also significant (F(7.8, 838.3) = 5.80, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04, VSR = 58250.54). Post-hoc tests indicated that patients with SCZ + DM scored lower on the attention domain than those with SCZ (t = 6.0, SE = 2.25, pHolm < 0.001, d = 1.0) and SCZ+MetS (t = 4.78, SE = 2.49, pHolm < 0.001, d = 0.98). However, there was no difference between SCZ and SCZ+MetS (pHolm = 1, d = 0.11). Similar results were obtained for delayed memory (SCZ + DM < SCZ, t = 5.39, SE = 2.50, pHolm < 0.001; d = 0.97; SCZ + DM < SCZ + MetS, t = 3.72, SE = 2.49, pHolm < 0.05, d = 0.70; SCZ = SCZ+MetS, pHolm = 1, d = 0.2). There were no significant between-group differences for immediate memory, visuospatial functions, and language (psHolm > 0.05) (Table 3).

Laboratory measures and cognitive performance

Multiple regression analyses revealed that IL-6 was the sole significant predictor of the RBANS attention score in the entire sample (β = −0.37, t = −5.34, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.19, VSR = 94017.2). For the RBANS delayed memory score, there were two predictors: IL-6 (β = −0.16, t = −2.11, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.08, VSR = 3.1) and FBG (β = −0.22, t = −2.58, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.08, VSR = 7.6). For the remaining RBANS domain scores (immediate memory, language, and visuospatial functions), we found no significant predictors from the laboratory measures (ps > 0.2).

In the whole sample, there were several significant correlations between RBANS attention scores and laboratory measures: IL-6 (r = −0.42, p < 0.001, VSR = 1.1×108), FBG (r = −0.27, p < 0.001, VSR = 520.8), TG (r = −0.19, p < 0.05, VSR = 13.5), and HDL (r = 0.20, p < 0.05, VSR = 17.7). However, in SCZ+MetS, the sole significant correlation was found between RBANS attention scores and IL-6 (r = -0.45, p < 0.001, VSR = 207.5). This correlation was consistently significant in SCZ + DM (r = −0.42, p < 0.01, VSR = 31.8), but not in SCZ (r = −0.14, p = 0.15, VSR = 1.3).

For RBANS delayed memory, we also found several significant correlations in the whole sample, including IL-6 (r = −0.28, p < 0.001, VSR = 985.8) and FBG (r = −0.28, p < 0.001, VSR = 897.1). Significant correlation between RBANS delayed memory and IL-6 was also observed in SCZ + DM (r = −0.40, p < 0.01, VSR = 20.2), but not in SCZ+MetS and SCZ (ps > 0.1; for detailed correlation analyses, see the Supplementary Material).

Discussion

In the largest single-cohort analysis to concurrently stratify schizophrenia by metabolic comorbidity (SCZ, SCZ+MetS, SCZ + DM), we showed that IL-6 and fasting glucose, but not CRP, map selectively to attention and delayed memory, refining prior global findings and quantifying precision using frequentist and Bayesian metrics. Two previous meta-analyses found that metabolic disorders contribute to the exacerbation of cognitive dysfunction in SCZ5,24 but it has not been proven that this association is confined to specific cognitive domains and is related to particular markers of low-grade peripheral inflammation.

Several factors and pathophysiological mechanisms may underlie our findings. First, severe insulin resistance (IR) is a central feature of the pathophysiology of type 2 DM25. A hallmark of DM and IR is impaired insulin signaling, which can lead to pathological alterations in key processes within the central nervous system (CNS)26. These processes play a profound role in synaptic transmission, neuronal survival, the elimination of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial function, energy metabolism, and the regulation of neural plasticity27,28,29. For instance, studies on rodents suggest that insulin may influence mesolimbic dopamine turnover and is involved in the regulation of long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity. Insulin is also believed to promote the membrane recruitment of NMDA receptors into excitatory synapses, thereby contributing to synaptic plasticity27,30,31. A comprehensive meta-analysis demonstrated that insulin plays a role in the regulation of multiple neurotransmitter pathways, including those of glutamate, GABA, serotonin, and dopamine32. This is especially relevant in cortical networks, thereby influencing the processes underlying cognitive functions33.

In our study, fasting blood glucose levels exhibited a negative correlation with attention and delayed memory domains. These findings potentially suggest that IR may affect the prefrontal cortex, fronto-parietal regions, and neural circuits related to attentional functions (e.g., alertness, inhibitory control, sustained attention, selection). In support of this, neuroimaging studies have confirmed that insulin resistance can negatively impact the physiological structure of various brain regions and networks34,35,36,37. However, we must emphasize that, in terms of energy metabolism, neurons are capable of insulin-independent glucose uptake38. One possible explanation for the deterioration of delayed memory functions is hippocampal impairment, as well as alterations in the networks connecting the hippocampus with various cortical regions. This could be supported by previous research, which found a negative correlation between IR and the volume of the hippocampal tail in patients with first-episode psychosis39. Furthermore, it is a well-documented phenomenon that DM can contribute to impaired hippocampal neurogenesis, increased apoptosis, and, consequently, hippocampal atrophy40,41. Intriguingly, the hippocampus may also play a role in the regulation of peripheral glucose metabolism. Electrophysiological studies conducted on rodent brains have demonstrated that oscillatory patterns of the hippocampus can be used to predict a decrease in blood glucose levels42.

To provide further insight, several neuroimaging studies have highlighted the crucial role of glucose metabolism dysregulation in the central nervous system of patients with SCZ. For example, a 2022 meta-analysis by Townsend et al. of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (¹⁸F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) studies revealed reduced glucose metabolism in the frontal cortex of individuals with chronic SCZ, which may serve as a potential explanation for the cognitive dysfunctions observed in the disease43. Furthermore, studies utilizing ³¹P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) have shown that cognitive dysfunctions in affective and non-affective psychosis are associated with decreased NAD + /NADH ratios and reduced creatine kinase (CK) activity in the brain, suggesting dysregulation of cellular-level metabolism44.

Additionally, hyperglycemia observed in DM can contribute to the damage of the blood-brain barrier, as well as endothelial dysfunction, vascular remodeling, and associated cerebrovascular complications45. Grey matter reduction and white matter abnormalities, which impact functional connectivity, have also been observed in DM46,47.

Other components of MetS, such as hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia, can also lead to structural changes in the brain and alterations in physiological cytoarchitecture, thereby potentially facilitating further deterioration of cognitive functions48.

We also have to point out that MetS and DM exhibit a bidirectional relationship with chronic low-grade inflammation14,49. For example, several studies have confirmed the role of obesity in facilitating systemic inflammatory processes, this effect is primarily driven by adipokines (e.g., leptin) secreted by adipocytes and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF) produced by adipose tissue macrophages14. It is also important to emphasize, further highlighting the complexity of metabolic dysregulations, that IR itself can induce systemic inflammation50.

These multifaceted interactions have also been observed in the CNS. For example, a post-mortem study on the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease found elevated IL-6 and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS-3) levels, which is particularly interesting given that SOCS-3 may play a role in impairing insulin signaling, potentially contributing to the development of brain IR51,52,53. In addition to its complexity, chronic hyperglycemia and progressive glucose load exhibit neurotoxic effects, leading to the buildup of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Through diverse cascade mechanisms, these contribute to pathological microglial activity patterns and the polarization of microglia towards the M1 phenotype, further exacerbating inflammation, neuronal and synaptic damage54. Interestingly, studies on human astrocyte cell cultures have demonstrated that under high glucose conditions, astrocytes respond to inflammatory stimuli by increasing the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8, which may further amplify neuroinflammation and its associated detrimental effects55.

In our study, we found that the highest IL-6 levels were measured in patients with both MetS and DM, followed by the group with MetS without DM, while the lowest values were measured in those without MetS. Surprisingly, regarding CRP levels, we found no significant differences between the three groups. IL-6 levels showed a significant negative correlation with attention and delayed memory domains. These results are consistent with data reported in a recent meta-analysis showing that IL-6 levels negatively correlate with these cognitive functions56.

Several factors may contribute to these findings. Evidence suggests that both abnormal innate and adaptive immune regulatory processes may be involved in the exacerbation of cognitive impairment57. For instance, in drug-naïve first-episode SCZ patients, elevated expression of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and an increased ratio of TLR4+ monocytes have been shown to correlate with cognitive dysfunctions58. Furthermore, in chronic low-grade inflammation, proinflammatory cytokines can cross the blood-brain barrier, potentially leading to pathological activation of microglia and astrocytes, which contributes to the development of neuroinflammation. In addition, neuroinflammation is associated with mechanisms such as glutamatergic excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, decreased neurotransmission, and neurodegeneration, leading to gray matter atrophy, cortical thinning, and ultimately a decrease in total brain volume59,60,61.

Based on the findings and explanations discussed in the previous paragraphs, a highly complex association emerges between metabolic dysregulations, inflammation, and cognitive dysfunctions. This relationship is further nuanced by the fact that antipsychotic medications used in the treatment of SCZ can induce metabolic side effects through various mechanisms, such as alterations in the gut microbiome, impaired central glucose sensing in the hypothalamus, weight gain, and dysregulation of peripheral glucose and lipid metabolism15,62,63,64. Paradoxically, both inflammation and metabolic dysregulations, such as IR, may play a significant role in therapeutic response and the development of treatment resistance65,66,67.

Although we suggested a pathway from metabolic deterioration to peripheral inflammation and cognitive dysfunction, the reverse direction is also biologically plausible. Central cholinergic circuits regulate both cognition and systemic cytokine responses via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, through which central acetylcholine signaling can dampen peripheral macrophage cytokine production. Muscarinic-targeted therapy for schizophrenia, such as xanomeline–trospium, may have a specific impact on inflammation and cognition. This invites prospective studies to explore whether cholinergic augmentation reduces peripheral IL-6 and improves attention and delayed memory, which are the cognitive domains most strongly associated with IL-6 and fasting glucose in our cohort68,69.

Implications for practice

The timely translation of scientific results into clinical practice is explicitly prioritized by the Academia Europaea70,71. Our results support incorporating routinely obtainable inflammatory markers alongside metabolic indices when profiling cardiometabolic and cognitive risk in SCZ. In practice, this favors integrated care models in which psychiatry and primary care jointly monitor glucose, lipids, weight, and inflammation, and consider antipsychotics with lower metabolic liability when appropriate. Adjunctive interventions that target glucose homeostasis and inflammation merit prospective evaluation for cognitive outcomes. The impact of various metabolic therapies, such as the ketogenic diet, on cognitive functions could represent a potential research direction, as preliminary findings among individuals with severe mental disorders are promising72. Furthermore, enhancing physical activity of patients and incorporating regular exercise into their lives is of paramount importance, as this may potentially improve inflammation, metabolic disturbances, and the associated structural brain abnormalities73.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the most extensive study to date to investigate the relationship between MetS, DM, inflammatory markers, and cognition in patients with SCZ. The SCZ patients with newly diagnosed MetS and DM did not receive specific medications for MetS and DM, which excludes the potential confounding effects of these drugs on inflammatory markers and cognition.

The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. The observed associations may reflect bidirectional relationships and residual confounding, including exposure to different kinds of antipsychotics. The inflammatory milieu was investigated only by measuring IL-6 and CRP, markers of low-grade systemic inflammation that do not capture pathway-specific cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) or anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-10). Broader panels may refine mechanistic interpretation. Finally, precision for some subgroup analyses is limited. For example, with n = 53 in SCZ + DM, the minimum detectable within-group correlation at 80% power is 0.38. The issue of a more comprehensive inflammatory panel, the confounding effect of different types of antipsychotic multiple medications, and the likelihood of type II errors can be addressed by recruiting larger samples. In the present study, we use Bayesian statistics, which is well-suited for small sample sizes because it does not rely on the asymptotic assumptions of large samples, providing more power and precision in these situations.

Data availability

The raw data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Kahn, R. S. et al. Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1, 15067 (2015).

Cowman, M. et al. Cognitive predictors of social and occupational functioning in early psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Schizophr. Bull. 47, 1243–1253 (2021).

Millan, M. J. et al. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 141–168 (2012).

Vancampfort, D. et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 14, 339–347 (2015).

Bora, E., Akdede, B. B. & Alptekin, K. The relationship between cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 47, 1030–1040 (2017).

Qiu, C. & Fratiglioni, L. A major role for cardiovascular burden in age-related cognitive decline. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 267–277 (2015).

Bahrami, S. et al. Shared genetic loci between body mass index and major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 503–512 (2020).

Lv, H. et al. Identification of genetic loci that overlap between schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 318, 114947 (2022).

Hackinger, S. et al. Evidence for genetic contribution to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes in schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 252 (2018).

Morris, A., Reed, T., McBride, G. & Chen, J. Dietary interventions to improve metabolic health in schizophrenia: a systematic literature review of systematic reviews. Schizophr. Res 270, 372–382 (2024).

Druart, M. & Le Magueresse, C. Emerging roles of complement in psychiatric disorders. Front. Psychiatry 10, 573 (2019).

Wang, A. K. & Miller, B. J. Meta-analysis of cerebrospinal fluid cytokine and tryptophan catabolite alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 75–83 (2018).

Müller, N. Inflammation in schizophrenia: pathogenetic aspects and therapeutic considerations. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 973–982 (2018).

Hildebrandt, X., Ibrahim, M. & Peltzer, N. Cell death and inflammation during obesity: ‘Know my methods, WAT(son). Cell Death Differ. 30, 279–292 (2023).

Zeng, C. et al. Gut microbiota: An intermediary between metabolic syndrome and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 106, 110097 (2021).

Allott, K., Chopra, S., Rogers, J., Dauvermann, M. R. & Clark, S. R. Advancing understanding of the mechanisms of antipsychotic-associated cognitive impairment to minimise harm: a call to action. Mol. Psychiatry 29, 2571–2574 (2024).

MacKenzie, N. E. et al. Antipsychotics, metabolic adverse effects, and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 9, 622 (2018).

Pillinger, T. et al. Impaired Glucose Homeostasis in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 261–269 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed., 2013.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S. & Spitzer, R. L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders—Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV) (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2016).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285, 2486–2497 (2001).

Randolph, C., Tierney, M. C., Mohr, E. & Chase, T. N. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 20, 310–319 (1998).

Hagi, K. et al. Association between cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 510–518 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 216 (2022).

Kullmann, S. et al. Brain insulin resistance at the crossroads of metabolic and cognitive disorders in humans. Physiol. Rev. 96, 1169–1209 (2016).

Kleinridders, A. et al. Insulin resistance in brain alters dopamine turnover and causes behavioral disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3463–3468 (2015).

Arnold, S. E. et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 168–181 (2018).

Kullmann, S. et al. Central nervous pathways of insulin action in the control of metabolism and food intake. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 8, 524–534 (2020).

Zhao, F., Siu, J. J., Huang, W., Askwith, C. & Cao, L. Insulin modulates excitatory synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity in the mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience 411, 237–254 (2019).

Skeberdis, V. A., Lan, J., Zheng, X., Zukin, R. S. & Bennett, M. V. Insulin promotes rapid delivery of N-methyl-D- aspartate receptors to the cell surface by exocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3561–3566 (2001).

de Bartolomeis, A. et al. Insulin effects on core neurotransmitter pathways involved in schizophrenia neurobiology: a meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Implications for the treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2811–2825 (2023).

McCutcheon, R. A., Keefe, R. S. E. & McGuire, P. K. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 1902–1918 (2023).

Xia, W. et al. Insulin resistance-associated interhemispheric functional connectivity alterations in T2DM: a resting-state fMRI study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 719076 (2015).

Deery, H. A. et al. Peripheral insulin resistance attenuates cerebral glucose metabolism and impairs working memory in healthy adults. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2, 17 (2024).

Kullmann, S., Heni, M., Fritsche, A. & Preissl, H. Insulin action in the human brain: evidence from neuroimaging studies. J. Neuroendocrinol. 27, 419–423 (2015).

Kullmann, S. et al. Intranasal insulin enhances brain functional connectivity mediating the relationship between adiposity and subjective feeling of hunger. Sci. Rep. 7, 1627 (2017).

Petersen, M. C. & Shulman, G. I. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev. 98, 2133–2223 (2018).

Armio, R.-L. et al. Longitudinal study on hippocampal subfields and glucose metabolism in early psychosis. Schizophrenia 10, 66 (2024).

Ho, N., Sommers, M. S. & Lucki, I. Effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis: links to cognition and depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 1346–1362 (2013).

Stranahan, A. M. et al. Diabetes impairs hippocampal function through glucocorticoid-mediated effects on new and mature neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 309–317 (2008).

Tingley, D., McClain, K., Kaya, E., Carpenter, J. & Buzsáki, G. A metabolic function of the hippocampal sharp wave-ripple. Nature 597, 82–86 (2021).

Townsend, L. et al. Brain glucose metabolism in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of (18)FDG-PET studies in schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 53, 4880–4897 (2023).

Chouinard, V.-A. et al. Cognitive Impairment in Psychotic Disorders Is Associated with Brain Reductive Stress and Impaired Energy Metabolism as Measured by 31P Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Schizophr. Bull sbaf003, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaf003 (2025).

Prasad, S., Sajja, R. K., Naik, P. & Cucullo, L. Diabetes mellitus and blood-brain barrier dysfunction: an overview. J. Pharmacovigil. 2, 125 (2014).

Ma, T. et al. Gray and white matter abnormality in patients with T2DM-related cognitive dysfunction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Diab. 12, 39 (2022).

Zhang, T., Shaw, M. & Cherbuin, N. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and brain atrophy: a meta-analysis. Diab. Metab. J. 46, 781–802 (2022).

Yates, K. F., Sweat, V., Yau, P. L., Turchiano, M. M. & Convit, A. Impact of metabolic syndrome on cognition and brain: a selected review of the literature. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2060–2067 (2012).

Reddy, P., Lent-Schochet, D., Ramakrishnan, N., McLaughlin, M. & Jialal, I. Metabolic syndrome is an inflammatory disorder: a conspiracy between adipose tissue and phagocytes. Clin. Chim. Acta. 496, 35–44 (2019).

Shimobayashi, M. et al. Insulin resistance causes inflammation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 128, 1538–1550 (2018).

Lyra E Silva, N. M. et al. Pro-inflammatory interleukin-6 signaling links cognitive impairments and peripheral metabolic alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 251 (2021).

Rui, L., Yuan, M., Frantz, D., Shoelson, S. & White, M. F. SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 block insulin signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRS1 and IRS2. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42394–42398 (2002).

Jorgensen, S. B. et al. Deletion of skeletal muscle SOCS3 prevents insulin resistance in obesity. Diabetes 62, 56–64 (2013).

Tian, Y., Jing, G., Ma, M., Yin, R. & Zhang, M. Microglial activation and polarization in type 2 diabetes-related cognitive impairment: a focused review of pathogenesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 165, 105848 (2024).

Bahniwal, M., Little, J. P. & Klegeris, A. High glucose enhances neurotoxicity and inflammatory cytokine secretion by stimulated human astrocytes. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 14, 731–741 (2017).

Patlola, S. R., Donohoe, G. & McKernan, D. P. The relationship between inflammatory biomarkers and cognitive dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 121, 110668 (2023).

Chen, S., Tan, Y. & Tian, L. Immunophenotypes in psychosis: is it a premature inflamm-aging disorder? Mol. Psychiatry 29, 2834–2848 (2024).

Kéri, S., Szabó, C. & Kelemen, O. Antipsychotics influence Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression and its relationship with cognitive functions in schizophrenia. Brain Behav. Immun. 62, 256–264 (2017).

Pape, K., Tamouza, R., Leboyer, M. & Zipp, F. Immunoneuropsychiatry - novel perspectives on brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15, 317–328 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Cortical grey matter volume reduction in people with schizophrenia is associated with neuro-inflammation. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e982 (2016).

Chaves, C., Dursun, S. M., Tusconi, M. & Hallak, J. E. C. Neuroinflammation and schizophrenia - is there a link? Front. Psychiatry 15, 1356975 (2024).

Castellani, L. N. et al. Antipsychotics impair regulation of glucose metabolism by central glucose. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4741–4753 (2022).

Pillinger, T. et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 64–77 (2020).

Morgan, A. P. et al. The antipsychotic olanzapine interacts with the gut microbiome to cause weight gain in mouse. PLoS One 9, e115225 (2014).

Mondelli, V. et al. Cortisol and Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict Poor Treatment Response in First Episode Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 1162–1170 (2015).

Noto, C. et al. High predictive value of immune-inflammatory biomarkers for schizophrenia diagnosis and association with treatment resistance. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 16, 422–429 (2015).

Tomasik, J. et al. Association of insulin resistance with schizophrenia polygenic risk score and response to antipsychotic treatment. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 864–867 (2019).

Pavlov, V. A. Novel opportunities for treating complex neuropsychiatric and neurocognitive conditions based on recent developments with xanomeline. Front Psychiatry 16, 1593341 (2025).

Metz, C. N., Brines, M. & Pavlov, V. A. Bridging cholinergic signalling and inflammation in schizophrenia. Schizophr 10, 51 (2024).

Hegyi, P., Erőss, B., Izbéki, F., Párniczky, A. & Szentesi, A. Accelerating the translational medicine cycle: the Academia Europaea pilot. Nat. Med 27, 1317–1319 (2021).

Hegyi, P. et al. Academia Europaea position paper on translational medicine: the cycle model for translating scientific results into community benefits. J. Clin. Med. 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051532 (2020).

Sethi, S. et al. Ketogenic diet intervention on metabolic and psychiatric health in bipolar and schizophrenia: a pilot trial. Psychiatry Res. 335, 115866 (2024).

Noordsy, D. L., Burgess, J. D., Hardy, K. V., Yudofsky, L. M. & Ballon, J. S. Therapeutic potential of physical exercise in early psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 209–214 (2018).

Acknowledgements

None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alexander Kancsev: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft; Marie Anne Engh: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; András Horváth: conceptualization, writing—review and editing; Péter Hegyi: conceptualization, writing—review and editing; Oguz Kelemen: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—review and editing Szabolcs Kéri: project administration, data curation, conceptualization, formal analysis, visualization, supervision; writing—original draft. All authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. This research received no external funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kancsev, A., Engh, M.A., Horváth, A.A. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, inflammation and cognitive dysfunctions in schizophrenia: a cross-sectional analysis. Schizophr 11, 148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00694-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00694-y