Abstract

Metabolic disorders encompass various dysregulations, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, central obesity, atherogenic hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance. Dyslipidemia refers to elevated levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, along with decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the blood. Dyslipidemia is closely associated with hypertension, which is one of the important risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

In this study, an apolipoprotein E-deficient (apoE−/−) mouse model was utilized to investigate whether supplementation with steamed mature silkworm, known as HongJam, might ameliorate and have therapeutic effects on metabolic disorders and behavioral abnormalities observed in apoE−/− mice. The Golden Silk HongJam-supplemented feed-consuming (GSf)-apoE−/− mice showed recovery from the reduced spatial memory, social memory, and postural control ability observed in the normal feed-consuming (Nf)-apoE−/− mice. They also exhibited similar blood pressure to those in the normal feed-consuming C57BL/6J control (Nf-Con) group. Additionally, the significantly reduced activities of glutathione-S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, acetylcholinesterase, and mitochondrial complexes I–IV in the Nf-apoE−/− group were restored in all GSf-apoE−/− groups. Furthermore, the amount of ATP in all GSf-apoE−/− mice was similar to or higher than that in the Nf-Con group.

Taken together, GS HongJam supplementation may have preventive, ameliorative, and therapeutic effects on the symptoms of metabolic disorders caused by the loss of ApoE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a 34 kDa glycoprotein primarily synthesized in the liver and brain, and its key roles include interactions with lipoprotein particles1. Certain mutations in the ApoE gene in humans cause familial hypercholesterolemia2,3. While most plasma ApoE is produced by hepatocytes in the liver, peripheral sources include macrophages, astrocytes, and adipocytes1. Important functions of plasma ApoE include lipid transport, lipoprotein metabolism, and cholesterol homeostasis. However, ApoE secreted by macrophages does not regulate blood lipid concentrations. Instead, it functions in cellular cholesterol efflux from atheroma of the vascular wall4. Inflammatory stress conditions lead to decreased secretion of ApoE from macrophages, weakening its atheroprotective effects5. In the brain, astrocytes serve as the primary source of apolipoproteins, with ApoE being the most abundant lipoprotein in cerebrospinal fluid. Dysfunction of ApoE is known as the most significant risk factor for dementia6.

Metabolic disorders encompass various dysregulations such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, central obesity, atherogenic hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance. Without appropriate treatment, these conditions can progress to life-threatening cardiovascular disease and diabetes7. Dyslipidemia refers to elevated levels of total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and triglycerides (TG), along with decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) levels in the blood. Dyslipidemia is closely associated with hypertension, which is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease8.

Various animal models have been developed and utilized for research on dyslipidemia. Among them, the apoE deficient (apoE−/−) mouse model is widely used in dyslipidemia research because it recapitulates the hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, and hypertension observed in patients with human hypercholesterolemia9,10,11,12,13.

The treatment methods for hyperlipidemia vary slightly from country to country; however, in most nations, optimal medications are prescribed based on the patient’s cardiovascular risk14. In addition, the long-standing knowledge that healthy diet intervention contributes to the management of hyperlipidemia and hypertension is supported by systematic investigations15,16. It has been scientifically confirmed that the levels of TC, TG, and LDL in hyperlipidemic patients who received medical nutrition therapy (MNT) from registered dietitian nutritionists were significantly lower than those who did not17. In addition, the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH), a nonpharmacological dietary strategy for reducing hypertension, has been proven to be effective for managing hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease16.

Silkworms have been extensively bred by humans for over 5000 years for the production of silk fabrics and for obtaining high-protein nutrients. Humans have long used by-products from silkworm breeding as remedies for various diseases. According to traditional oriental medicine books, by-products of silkworms are effective against hypertension, diabetes, and insomnia18. Additionally, consumption of silkworm larvae or pupae has been reported to improve hyperlipidemia and hypertension19.

HongJam (HJ) is a natural health food produced by steaming mature silkworm larvae18,20. In particular, silkworms are sensitive to environmental pollutants such as pesticides, dust, odor, and vibration; therefore, they can only be bred in clean areas where mulberry leaves are grown without any contamination. According to the nutritional analysis results of freeze-dried HJ, it contains approximately 70% protein, 15% fatty acids, 3% fiber, 3% ash, diverse vitamins, and phytochemicals21,22,23,24. Recent studies have shown that HJ has various functions, including preventive effects against Parkinson’s disease, improvement of memory, gastrointestinal protection, and enhancement of liver function18,20. However, whether HJ affects the onset and progression of dyslipidemia and hypertension due to abnormalities in ApoE function has not been investigated. In this study, we used an apoE−/− mouse model to investigate whether supplementation with HJ alleviates and has therapeutic effects on metabolic disorder symptoms and behavioral abnormalities associated with ApoE dysfunction.

Results

Supplementing Golden Silk (GS)-HJ restored the declined spatial memory of the apoE−/− group

At 31, 39, and 55 weeks, spatial working memories in GS-HJ-supplemented feed (GSf-apoE−/−) groups were tested and compared to those in the normal feed-consuming C57BL/6J control (Nf-Con) group using Y-maze assays (Fig. 1A). There was food supplement group (between) effects [F(4, 105) = 7.488, P < 0.0001], but with non-significant age (within) effects [F(2, 105) = 0.7889, P > 0.05] and within–between interaction differences [F(8, 105) = 0.7745, P > 0.05]. Post-hoc pairwise comparison revealed differences at 31 weeks of age between the Nf-apoE−/− and 0.4 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05), between the Nf-apoE−/− and 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05). At 55 weeks, differences were found between the Nf-apoE−/− and 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05), between the Nf-apoE−/− and 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05). These results demonstrate that GS-HJ supplementation ameliorated the decline in spatial memory caused by the loss of ApoE function.

Two-way ANOVA was performed to investigate the effect of GS-HJ supplementation on various types of memory and behavior. A Significant differences were found in spatial memory between strains and GS-HJ supplementation (F(4, 105) = 7.488, P < 0.0001), but there was no significant difference in spatial memory with age (F(2, 105) = 0.7889, P > 0.05). No interaction effect was observed between GS-HJ supplementation and age for spatial memory (F(8, 105) = 0.7745, P > 0.05). B Significant differences were observed in posture control abilities with age (F(2, 105) = 9.088, P < 0.0005), but no significant differences were found between strains or with GS-HJ supplementation (F(4, 105) = 2.071, P > 0.05). No interaction effect was observed between GS-HJ supplementation and age for posture control abilities (F(8, 105) = 0.9655, P > 0.05). C Significant differences were found in sociability with age (F(2, 105) = 4.193, P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences between strains or with GS-HJ supplementation (F(4, 105) = 2.307, P > 0.05). A significant interaction effect was observed between GS-HJ supplementation and age for sociability (F(8, 105) = 3.854, P < 0.001). D Significant differences were observed in social memory with age (F(2, 105) = 7.522, P < 0.001) and with GS-HJ supplementation (F(4, 105) = 4.694, P < 0.005). A significant interaction effect was found between GS-HJ supplementation and age for social memory (F(8, 105) = 3.763, P < 0.001).

Consumption of GS-HJ prevents the decline in postural control ability in the apoE−/− group

At 32, 40 and 56 weeks, postural control ability among the groups was tested by limb clasping tests (LCT). There was age (within) effects [F(2, 105) = 9.088, P < 0.001], but with non-significant food supplement group (between) effects [F(4, 105) = 2.071, P < 0.05] and within–between interaction differences [F(8, 105) = 0.9655, P < 0.05]. Post-hoc pairwise comparison revealed non-significant differences between the Nf- apoE−/− and all GSf-apoE−/− groups. However, when one-way ANOVA analysis was performed at 56 weeks, the postural control ability of the Nf-apoE−/− group was significantly worse than that of the 1.0 g and 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups. There was no difference between the Nf-Con group and either the Nf-apoE−/− or the 0.4 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (F(4, 39) = 4.721, P < 0.05, Fig. 1B).These results demonstrate that the decreased postural control ability observed in the Nf-Con and Nf-apoE−/− groups with aging was restored by GS-HJ supplementation.

GS-HJ supplementation prevented declining of social memory in the apoE−/− group

We conducted a study to investigate how sociability and social memory change in apoE−/− groups with aging progression and GS-HJ supplementation. The sociability of all groups was tested at 31, 47, and 63 weeks. There were age (within) effects [F(2, 105) = 4.193, P < 0.05] and significant within–between interaction differences [F(8, 105) = 3.854, P < 0.001], but with non-significant food supplement group (between) effects [F(4, 105) = 2.307, P > 0.05]. The influence of age was evident in the Nf-Con group (P < 0.05). The sociability of the Nf-Con group at 31 weeks was lower than that of the other apoE−/− groups, even though there was no difference among the tested groups at 47 and 63 weeks (Fig. 1C).

The social memory of tested groups was compared at 31, 47 and 63 weeks. There was age (within) effects [F(2, 105) = 7.522, P < 0.001], food supplement group (between) effects [F(4, 105) = 4.694, P < 0.005] and significant within–between interaction differences [F(8, 105) = 3.763, P < 0.001]. The influence of age was evident in the Nf-Con and Nf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05), but not at all in the GSf-apoE−/− group. At 63 weeks, the post-hoc pairwise comparison showed a difference between two Con vs. all three GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05). Fig. 1D). These results demonstrated that GS-HJ supplementation ameliorated the declining social memory observed in the Nf-Con and the Nf-apoE−/− groups due to aging.

GS-HJ supplementation lowered the hypertension observed in the Nf-apoE−/− group

We investigated whether the hypertension observed in the Nf-apoE−/− group could be reduced by GS-HJ supplementation at 53 and 61 weeks. There was food supplement group (between) effects [F(4, 70) = 9.449, P < 0.0001], but with non-significant age (within) effects [F(1, 70) = 0.07495, P < 0.7851] and within–between interaction differences [F(4, 70) = 0.6105, P < 0.05] in diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Post-hoc pairwise comparison revealed differences at 61 weeks of age between the Nf-apoE−/− and the 0.4 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.01), or the 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.05). The increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) recovered in all GSf-apoE−/− groups at 53 and 61 weeks. There was food supplement group (between) effects [F(4, 70) = 8.531, P < 0.0001] and age (within) effects [F(1, 70) = 5.294, P < 0.05], but with non-significant within–between interaction differences [F(4, 70) = 1.663, P > 0.05]. Post-hoc pairwise comparison revealed differences at 61 weeks of age between the Nf-apoE−/− and the 0.4 g GSf-apoE−/− groups (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that GS-HJ supplementation reduced hypertension in the Nf-apoE−/− group.

Two way-ANOVA was performed to investigate the effect of GS-HJ supplementation to blood pressures. A Significant differences in diastolic blood pressures (DBPs) between GS-HJ supplementations (F(4, 70) = 9.449, P < 0.0001). But no significant difference in DBPs between ages (F(1, 70) = 0.0749, P > 0.05). No interaction effect in DBPs between GS-HJ supplementation and aging (F(4, 70) = 0.6105, P > 0.05). B There were significant differences in systolic blood pressures (SBPs) with aging (F(1, 70) = 5.294, P < 0.05) and GS-HJ supplementations (F(4, 70) = 8.531, P < 0.001). No interaction effect in SBPs between GS-HJ supplementation and aging (F(4, 70) = 1.663, P > 0.05).

Reduced levels of TC, LDL, and TG in the blood of the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group

The amount of TC in the blood of the Nf-apoE−/− group was 3.18-fold higher than that of the Nf-Con group. Although there was no statistically significant difference in TC levels between the GSf-apoE−/− group and the Nf-apoE−/− group, a 25.2% decrease was observed in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group (F(4, 39) = 5.217, P < 0.005)(Fig. 3A).

A The amount of TC in the blood of the Nf-apoE−/− group was more than three times higher than that of the Nf-Con group. The 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group showed a 25.2% reduction in TC content compared to that of the Nf-apoE−/− group. B The amount of LDL in the blood of the Nf-apoE−/− group was more than six times higher than that of the Nf-Con group. The 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group showed a 15% reduction in LDL content compared to that of the Nf-apoE−/− group. C Except for the 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group, the amount of HDL in the blood of all apoE−/− groups was similar to that in the Nf-Con group. D The amount of TG in the blood of the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group was similar to that of the Nf-Con group. The levels in other apoE-/- groups were higher than those in the other two groups.

The concentration of LDL in the blood of the Nf-apoE−/− group was 6.38-fold higher than that of the Nf-Con group. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the LDL levels of three GSf-apoE−/− groups compared to the Nf-apoE−/− group, a 15.0% decrease was observed in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group compared to the Nf-apoE−/− group (F(4, 39) = 27.651, P < 1.0 × 10−9, Fig. 3B).

The concentration of HDL in the blood of the Nf-apoE−/− group was 34.3% higher than that of the Nf-Con group, although the difference was not significant. While there was no significant difference in the HDL levels of the 0.4 g and 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups compared to the Nf-apoE−/− group, a significant increase was observed in the 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group (F(4, 39) = 2.648, P < 0.05, Fig. 3C).

The concentration of TG in the blood of the Nf-apoE−/− group was 34.3% higher than that of the Nf-Con group, although the difference was not significant. While there was no significant difference in the TG levels of the 0.4 g and 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups compared to the Nf-apoE−/− group, a significant decrease was observed in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group. There was no significant difference between the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− and Nf-Con groups (F(4, 39) = 2.648, P < 0.05, Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the decrease in TG and LDL levels in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group compared with those in the Nf-apoE−/− group resulted in a decrease in TC levels.

GS-HJ supplementation restored activities of key enzymes reduced in the Nf-apoE−/− group

The activity level of Glutathione-S-transferase (GST), which is an important detoxification enzyme in animals, was compared. The significantly reduced GST activity in the Nf-apoE−/− group compared to that in the Nf-Con group appeared to be restored in the 0.4 g and 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups and was significantly enhanced in the 2.0 GSf-apoE−/− group (F(4, 14) = 7.648, P < 0.01)(Fig. 4A).

A The GST activity level of the Nf-apoE−/− group was significantly lower than that of the Nf-Con group and recovered in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group. B The reduced SOD activity levels in the NfapoE −/− group compared to those in the Nf-Con group were recovered in the 0.4 g and 1.0 g GSfapoE−/− groups. C The reduced activity of AchE in the Nf-apoE−/− group compared to that in the NfCon group was significantly recovered in the three GSf-apoE−/− groups.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) removes superoxide produced during metabolic processes in all living cells and plays a major role in regulating the anti-oxidative stress, fat metabolism, and inflammatory responses25. Compared with the Nf-Con group, the SOD activity level of the Nf-apoE−/− group was significantly reduced by 50%. The reduced SOD activity of the Nf-apoE−/− group tended to increase in the 0.4 g and 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups, so there was no significant difference from the Nf-Con group (F(4, 14) = 10.404, P < 0.01)(Fig. 4B).

Acetylcholinesterase (AchE) is a key enzyme that hydrolyzes acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter in neuromuscular junctions and cholinergic synapses in the central nervous systems, and regulates signaling in the muscles and brain. The AchE activity level in the Nf-apoE−/− group was significantly reduced to 23% of that in the Nf-Con group. In addition, compared to the Nf-apoE−/− group, AchE activity levels in all three GSf-apoE−/− groups were significantly enhanced (F(4, 14) = 12.076, P < 0.001)(Fig. 4C). These results suggested that the reduced enzyme activities observed in the apoE−/− groups were recovered by GS-HJ supplementation.

GS-HJ supplementation recovered mitochondria functions reduced in the Nf-apoE−/− group

Mitochondria play the most important role in the survival of neurons and other cells in the brain. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been reported to cause various neurological disorders in humans6. Interestingly, cholesterol accumulation in mitochondria is known to be one of the main causes of mitochondrial dysfunction in various organs and tissues26. Thus, the activities of Mitochondria complex (MitoCom) I–IV in mouse brain tissues were investigated to determine whether GS-HJ enhances mitochondrial function in the GSf-apoE−/− groups.

The activity of MitoCom I in the Nf-apoE−/− group decreased to 61.7% that in the Nf-Con group. The reduced activity of MitoCom I in the Nf-apoE−/− group was restored to the level of the Nf-Con group in all three GSf-apoE−/− groups (F(4, 14) = 6.268, P < 0.01)(Fig. 5A). The activity of MitoCom II in the Nf-apoE−/− group significantly decreased to 16% of that in the Nf-Con group, and it recovered in all three GSf-apoE−/− groups to 74-77% of that in the Nf-Con group (F(4, 14) = 16.18, P < 0.001)(Fig. 5B). The activity of MitoCom III in the Nf-apoE−/− group significantly decreased to 46% of that in the Nf-Con group. In addition, it increased more than threefold in the 0.4 g and 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups and restored in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group compared to the Nf-Con group (F(4, 14) = 221.89, P < 0.0001)(Fig. 5C). Although the activity of MitoCom IV in the Nf-apoE−/− group was similar to that in the Nf-Con group, it significantly increased in all three GSf-apoE−/− groups (F(4, 14) = 103.28, P < 0.0001)(Fig. 5D). These results suggest that GS-HJ supplementation could enhance the reduced activities of MitoCom I–IV, resulting in the restoration of mitochondrial function.

A The MitoCom I activity levels in the Nf-apoE−/− mice appeared to be lower than those in the NfCon group, and recovered in all GSf-apoE−/− mice. B Significantly reduced MitoCom II activity levels in the Nf-apoE−/− group compared to those in the Nf-Con group were recovered in all GSf-apoE−/− groups. C The reduced MitoCom III activity levels in the Nf-apoE−/− group compared to those in the Nf-Con group were recovered in all the GSf-apoE−/− groups. D MitoCom IV activity levels in the NfapoE−/− group were similar to those in the Nf-Con group. All GSf-apoE−/− groups showed significantly higher MitoCom IV activity levels than the Nf-Con group. E Significantly lower ATP levels in the NfapoE−/− group compared to those in the Nf-Con group were recovered or higher in all GSf-apoE−/−groups.

The reduced ATP levels in the Nf-apoE−/− group was restored in all GSf-apoE−/− groups

Since mitochondria dysfunction in the Nf-apoE−/− group was recovered in all GSf-apoE−/− groups (Fig. 4A–D), ATP levels in moue brain tissues were investigated. ATP levels in the brain tissues of the Nf-apoE−/− group were significantly decreased to 60% of those in the Nf-Con group. They were restored in the 0.4 g and 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− groups similar to those in the Nf-Con group. In addition, ATP levels in the 1.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group were significantly higher than those in the Nf-Con group (F(4, 14) = 23.747, P < 0.001)(Fig. 4E). These results suggest that GS-HJ supplementation could increase ATP levels in the brain tissues of apoE−/− groups.

Discussion

Recent advances in biomedical science and technology have led to a rapid increase in the average lifespan of humanity27. The advancement of science and technology has enhanced the productivity of all industries, enabling humanity to enjoy a materialistically abundant life unprecedented in previous generations18,20. As a result, in most industrialized countries, the increase in metabolic disorders due to over-nutrition is becoming a serious social issue7. In particular, the globalization of calorie-rich Western-style fast foods, which are colored and flavored with various food additives and can be prepared rapidly for easy consumption, originating mainly from the United States, has led to a decrease in the preference for regionally traditional healthy and slow foods with unique nutrients, flavors, and aromas, leading to a rapid increase in metabolic disorders worldwide28.

As mentioned earlier, patients with metabolic disorders who undergo drug therapy based on individual cardiovascular risk factors, along with dietary adjustments based on MNT prescriptions or the DASH diet, experience superior metabolic disorder control effects7,16. Previous studies have shown that HJ prevents the occurrence of gastric ulcers by suppressing oxidative and inflammatory responses in alcohol-treated rats29,30. It also improves liver function by inhibiting the production of inflammatory cytokines caused by alcohol in the liver, thereby reducing blood alcohol levels31. Alcohol consumption is a significant factor that cause metabolic disorders such as hyperlipidemia and hypertension. However, no research on the preventive, mitigating, or therapeutic effects of HJ on metabolic disorders has been conducted. Therefore, the most significant contribution of this study is the investigation of whether HJ consumption affects the levels of blood lipids and hypertension in apoE−/− mice, an important model for dyslipidemia and hypertension research. Consistent with previously reported results10,11,12, it was confirmed that the 64-week-old Nf-apoE−/− group had blood total cholesterol 3.18-fold higher and LDL 6.38-fold higher than those of the Nf-Con group (Fig. 3). In the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group, the amount of TG was lowered similarly to that in the Nf-Con group, and the amount of LDL was also reduced by 15%. The amount of TC in the 2.0 g GSf-apoE−/− group was reduced by 25.2%. Additionally, the blood pressure in all GSf-apoE−/− groups at weeks 53 and 61 was not significantly different from that of the Nf-Con group, suggesting that GS-HJ supplementation also had a blood pressure-lowering effect.

In this study, only female apoE−/− mice were used. In a previous study, it was reported that HDL cholesterol and apolipoproteins, important determinants of atherosclerosis, were significantly changed only in females not in males32. Additionally, coronary atherosclerosis was more prominent in female than in male mice at 16 weeks of age, while at 48 weeks, coronary lesions were similarly advanced in both sexes33. Furthermore, females were more susceptible to cognitive dysfunction than males34. Obviously, using male mice is a standard approach to reduce potential variability caused by the estrous cycle. In apoE−/− mice, a small percentage of young female mice (20–24 weeks) experienced disruptions in the regularity of their estrous cycles. As these mice matured, the percentage of those with irregular cycles increased, showing similar patterns for both apoE−/− and wild-type mice35. Therefore, while the disruption of the ApoE gene does impact the regularity of the estrous cycle in young mice, this change may not significantly affect the overall experimental process of this study, since all behavioral and biochemical analyses were performed after 31 weeks of age (Figs. 1–5).

Since 1992, the U.S. NIH has been conducting a clinical study called the DASH to investigate whether hypertension can be controlled through specific dietary interventions16. According to the results of the DASH studies, reducing the intake of saturated fats, omega-6 fatty acids, high glycemic load carbohydrates, and food additives commonly found in Western-style fast food, consumption of fresh vegetables, fruits, unprocessed whole grains, low-fat dairy products, lean meat, and nuts, has been clinically proven to lower blood pressure and alleviate conditions such as dyslipidemia and heart failure. Furthermore, it has been shown that reducing sodium and increasing potassium intake in the DASH diet leads to greater blood pressure-lowering effects36. However, since this study only provided a certain amount of GS-HJ supplementation without altering the overall diet, we still observed effects similar to MNT and the DASH diet in the metabolic disease animal model, scientific explanations for this phenomenon are necessary. Interestingly, the previously reported nutritional composition of GS-HJ21,22,24 may partially explain its lipid- and blood pressure-reducing effects. The crude nutrient composition of GS-HJ consisted of approximately 70% protein, 15% fatty acids, 3% fiber, and 3% ash. Its nutritional characteristics include that among the amino acids comprising proteins, the combined ratio of glycine, alanine, and serine accounts for 45.5%, and unsaturated fatty acids are approximately twice as abundant as saturated fatty acids. Among unsaturated fatty acids, omega-3, which is beneficial for cardiovascular health, is approximately four times more abundant than omega-6, and potassium is 14.8 times more abundant than sodium, suggesting its potential for lowering blood pressure.

Another significant finding of our study was that the activities of enzymes crucial for maintaining cellular and tissue homeostasis and function, such as GST, SOD, and AchE, which were reduced in the apoE−/− group, were restored in the GSf-apoE−/− group. In addition to its anti-oxidative stress effect through the detoxification of harmful substances, GST has been implicated in controlling metabolic disorders by mitigating vascular neointimal hyperplasia induced by hyperlipidemia37. SOD, an essential enzyme for regulating anti-oxidative stress, fat metabolism, and inflammatory responses, has been reported to exhibit reduced activity in the blood and brain tissues of apoE−/− mice38 and animals fed a high-fat diet39. Furthermore, a previous study indicated that AchE, which plays a central role in the cholinergic system responsible for memory, learning, attention, and other higher brain functions, was decreased in apoE−/− mice40. Thus, it can be inferred that GS-HJ supplementation restores the activities of GST, SOD, and AchE, thereby reducing blood lipid concentration and blood pressure while simultaneously enhancing memory and postural control ability.

This study also provided significant evidence that GS-HJ supplementation restored the mitochondrial dysfunction observed in the Nf-apoE−/− group. Previous studies on ApoE have highlighted its crucial role in forming complexes with the mitochondria, linking its dysfunction to the development of Alzheimer’s disease41. Furthermore, ApoE dysfunction has been associated with impaired mitochondrial function. Stress-induced changes in mitochondrial metabolism can lead to lipid accumulation, exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction and contributing to various metabolic disorders26,42. Notably, ApoE deficiency has been associated with vascular dysfunction and atherosclerosis in mice, resulting in reduced cerebral blood flow and impaired autonomic regulation of the cerebrovasculature43. The age-related breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in apoE−/− mice has also been correlates with behavioral impairments, further illustrating the multifaceted impact of ApoE deficiency on brain health44. In previous researches, we demonstrated that GS-HJ consumption of improved mitochondrial function and ATP levels in the brains of animals with mild cognitive impairment, leading to enhanced memory45,46. Similarly, in the current study, mitochondrial function and ATP levels, which were decreased in the Nf-apoE−/− group, were restored in the GSf-apoE−/− groups (Fig. 5). This restoration of mitochondrial function may contribute to reductions in blood lipid levels and blood pressure, as well as improved memories and behaviors.

As aging progresses, even healthy elderly individuals experience a decline in social functioning47. According to the results of this study, GS-HJ supplementation restored the social memory loss that occurs with aging, independent of ApoE dysfunction. This finding indicates that GS-HJ may not only improve symptoms caused by ApoE dysfunction but also delay the normal aging process.

In summary, this study provided various pieces of evidence that GS-HJ supplementation prevents, ameliorates, and has therapeutic effects on dyslipidemia and hypertension, as well as spatial memory loss that occurs due to ApoE dysfunction. Additionally, it was observed to restore postural control ability and social functioning, which deteriorate with aging. In the future, when clinical trials involving humans are conducted, personalized medicine for dyslipidemia and hypertension arising from ApoE dysfunction may be possible.

Methods

Materials

The GS variety, an F1 hybrid of Bombyx mori Jam 311 and Jam 312 pure breeds, was raised with mulberry leaves at the National Institute of Agricultural Science (NIAS) campus in Wanju-gun, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea. Tap water-cleaned and anesthetized mature silkworms were processed as previously described48,49,50. After steaming for 130 min using a pressure-free cooking unit (Kum Seong Ltd., Bucheon, Korea), the steamed mature silkworms, known as HJ, were freeze-dried at −50 °C for 24 h using a freeze-dryer (FDT-8612, Operon Ltd, Kimpo, Korea) and pulverized into particles using a natural stone roller mill (Duksan Co. Ltd., Siheung, Korea). Voucher specimens of GS-HJ were deposited in the Bombyx mori Quality Maintenance and Storage Laboratory, Division of Industrial Insect and Sericulture, NIAS, Wanju-gun, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea.

Experimental animals

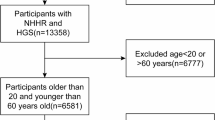

B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J (apoE−/−) and C57BL/6J mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) were housed and tested at the Laboratory Animal Facility of the Doheon Research Center, Hallym University. This animal experiment was conducted under the approval and supervision of the Hallym University Animal Clinical Trial Ethics Committee (HMC 2022-0-0304-04). The planning, conducting, and analysis of animal experiments adhered to the guidelines of Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments51. The control group (Con) consisted of eight female C57BL/6J mice that were fed normal feed (Nf, 2018S Teklad global 18% protein rodent diet, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The apoE−/− mice were randomly assigned to four experimental groups, each consisting of 8 female mice, at 4 weeks of age. The Nf-consuming apoE−/− (Nf-apoE−/−) group was supplied with Nf, as described above. After formulating GS-HJ into an Nf-based diet (GSf) at ratios of 0.4 g/kg body weight (BW), 1.0 g/kg BW, and 2.0 g/kg BW, it was supplied to apoE−/− mice. The experiment was terminated at the 64th week (Fig. 6). The BW changes in the Con and apoE-/- groups were measured every week (Supplementary Fig. 1). Significant differences in BW were observed between the Con and apoE−/− groups (F(4, 8) = 114.28, P < 0.0001) and across aging (F(8, 32) = 28.821, P < 0.0001). The BW differences between the Con and apoE−/− groups were not affected by aging (F(32, 315) = 0.9655, P > 0.05).

GS-HJ feed preparation protocol

Due to differences in BW between strains, food intake varies accordingly. In this study, the C57BL/6J and apoE−/− strains were used. Over four weeks, our calculations showed that the apoE−/− strain consumed an average of 141.5 ± 10.14 g of feed per kg BW per day, while the C57BL/6 J strain consumed 147.3 ± 7.53 g of feed per kg BW. There was no significant difference in intake between the two strains (P = 0.32).

Based on these results, GS-HJ was incorporated into the feed, estimating an average intake of 145 g of feed per kg BW per day for feed preparation. To provide 1.0 g of GS-HJ per kg BW per day (1.0 g GSf), mice consuming 145 g of feed daily were given feed containing 7.1 g of GS-HJ per kg of feed. For a 0.4 g GSf, 2.9 g of GS-HJ was added per kg of feed powder, and for a 2.0 g GSf, 14.2 g of GS-HJ was added. After adding GS-HJ to the feed powder, the mixture was thoroughly combined, formed into pellets, and dried using a UV sterilizing dryer. The formulated feeds were stored at 4 °C to maintain freshness before being administrated to the experimental animals. Equipment used for feed preparation included a mixer (HL 300, Hobart, OH, U.S.A.), a pellet mold (F-5/11-175D Pelleting Press, Fuji Paudal Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), and a UV sterilizing dryer (SMED 1.0, Hansung Ltd., Gimje, Korea).

Protocols for experimental animal behavior analysis and blood pressure measurement

To confirm the health-promoting effects of GS-HJ, behavioral analysis studies such as the Y-maze, three-chambered social interaction assay (SIA), and LCT were conducted, along with blood pressure measurement studies. The Y-maze test was conducted at 31, 39, and 55 weeks of age. SIA was performed at 31, 47, and 63 weeks, while LCT was conducted at 32, 40, and 56 weeks. Blood pressure measurements were performed at 53 and 61 weeks of age (Fig. 6).

The Y-maze spatial memory test protocol

To measure spatial memory and working memory in experimental animals, we conducted Y-maze test as previously described52. Briefly, the Y-maze apparatus consisted of three arms connected at 120-degree angles. Each arm was 35 cm long, 5 cm wide, and 10 cm high. The brightness of the experimental space was adjusted to 30–35 lux, and the experimental animals were gently placed in the center of the Y-maze and allowed to move freely for 10 min. The sequence in which the experimental animals entered each arm was recorded. Based on the number of entries and the sequence in each arm, a single spontaneous alteration was recorded when the animal sequentially entered each of the three arms. The number of spontaneous alterations during the 10-min period was divided by a number calculated by subtracting 2 from the total number of entries into arms to obtain spontaneous alteration ratios.

The SIA protocol

A previously published SIA protocol was used46. In brief, a three-chambered arena with passages for the free movement of experimental animals on clear acrylic plates was employed. On the first day, the experimental animals were allowed to move freely to acclimatize to the environment. In the first experiment on the second day, one side of the three chambers contained a novel mouse placed in a cage, whereas the other side of the three chambers contained an empty cage. The time spent in each chamber was measured. In the second experiment, one cage contained a mouse previously encountered by the experimental animal, whereas the other cage contained a novel experimental animal. The time spent by experimental animals in each chamber was measured.

The LCT protocol

Using a previously reported method53, we modified and performed a LCT to assess changes in corticospinal function in experimental animals. The tails of the experimental animals were held gently, and their limb movements and postures were recorded for 10 s. The LCT scores for all experimental animals were rated by two researchers based on the recorded data, evaluating the ability to extend the limbs and spread the toes on a scale of 0–4. A score of 0 indicated normal movement of all four limbs and the ability to spread the toes, while a score of 4 indicated the inability of the animal to move all four limbs and spread the toes.

The blood pressure measurement protocol

To measure changes in blood pressure in mice, we used the Coda high-throughput noninvasive blood pressure system (Kent Scientific Corp., Torrington, CT, USA). Experiments were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, experimental animals were placed in a holder designed for blood pressure measurements. The tail was then inserted into the cuff of the blood pressure monitor, and the monitor was connected to a notebook computer equipped with Coda software (Kent Scientific Corp.). The experimental animals were allowed to rest and stabilize on a temperature-controlled bed maintained between 32 and 35 °C before blood pressure measurement.

Protocol for obtaining blood and brain tissues from mice

When the experimental animals reached 64 weeks of age, they were euthanized with CO2 and blood samples were collected. After obtaining blood for various analyses, perfusion with an ice-cold saline solution was conducted for 30 min to remove the blood from the tissues. Brains were excised for collection. The collected brain was divided into halves, and regions such as the olfactory bulb, frontal cortex, cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus, cerebellum, and brainstem were obtained. Various biochemical analyses were performed on the collected tissues.

Protocol for the blood lipid measurement

Blood samples collected from the experimental animals were promptly analyzed for total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) levels using a cholesterol measurement device (Barrogen Lipid Plus, Handok, Seoul, Korea).

GST activity assay method

Brain tissues were homogenized in ice-cold 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.2) containing 1.0% Triton X-100 (PBST) and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant. The substrate solution was prepared by adding 146 μl of PBST, 2 μl of 200 mM glutathione (GTH, DaeJung Chemicals, Co.), and 2 μl of 100 mM 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB, Merck KGaA). After adding one-third of the sample to the substrate solution, the absorbance changes at 340 nm (A340 nm) were measured using a Multiskan Go spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) at 30-s intervals for 10 min. GST activity was calculated using the following equation:

GST activity = [A340 nm (Stop) – A340 nm (Start)]/[reaction time (min) x total volume (ml) x dilution factor].

SOD activity measurement method

The brain tissue was homogenized using ice-cold homogenization buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 250 mM sucrose, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg protease inhibitor). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was mixed with a substrate solution (40 mM Na2CO3, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.01% BSA, 0.05 mM xanthine, 0.1 mM NBT), and the absorbance changes at 550 nm (A550 nm) were measured using a Multiskan Go spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) at 30-s intervals for 5 min. The formula for calculating activity is as follows:

SOD activity (inhibition rate%) = [ΔA550nm/ΔA550nm of blank] × 100/[sample protein concentration].

Acetylcholinesterase (AchE) activity measurement method

Brain supernatants were used for AchE activity assays to measure GST activity. Substrate for AchE prepared by mixing 6.3 μl of 10 mM 5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) with 1.3 μl of 75 mM acetylcholine iodide, and 172.4 μl of PBS and 20 μl of brain supernatants were mixed. The absorbance changes at 412 nm (A412 nm) were measured using a Multiskan Go spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 30-s intervals for 10 min. The AchE activity was calculated using the following equation:

The AchE activity (µmol/ml/min0 = [ΔA412nm/min × V (ml) × dil]/ [ε × V enz 9 ml)].

dil = the dilution factor of the original sample

ε – the extinction coefficient constant = 13.6 M−1 cm−1

V - the reaction volume (for test 96-well plate) = 0.2 ml

V enz – the volume of the enzyme sample tested.

Extraction of mitochondria and measurement of the activity of mitochondrial complexes I–IV

A previously published protocol for extracting mitochondria was used45,46. Using mitochondria extraction buffer (MEB; 0.01 mM HEPES; pH 7.2, 125 mM sucrose; 250 mM mannitol; 10 mM EGTA; 0.01% (w/v) BSA, Merck KGaA), the brain tissue was homogenized, and then centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain the supernatant. The obtained supernatant was further centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain a pellet containing mitochondria. The pellet was mixed with MEB containing 0.02% digitonin and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to precipitate the mitochondria. The precipitated mitochondria were mixed well with chilled MEB to measure the activity of the mitochondrial complexes (MitoCom) I and II. To measure the activities of MitoCom III and IV, the pellet was mixed with MEB containing 1 mM n-D-β-D maltoside.

To measure MitoCom I activity, 20 μg of mitochondrial sample was mixed with MitoCom I assay buffer (25 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.8, 0.35% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 60 μM dichlorophenolindophenol (DCIP), 70 μM decylubiquinone, 1 μM antimycin A, 0.02 mM NADH) and 5 mM NADH. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 4 min, and the absorbance at 600 nm (A600nm) was measured using a Multiskan Go spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

For the measurement of MitoCom II activity, 20 μg of the mitochondrial sample was mixed with MitoCom II assay buffer (80 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.8, 0.1% BSA (w/v); 2.0 mM EDTA; 0.2 mM ATP; 80 mM DCIP; 50 mM decylubiquinone; 1.0 mM antimycin A; 3.0 mM rotenone, Merck KGaA). The reaction was then initiated at 37 °C for 10 min. Before measuring A600nm for 5 min, 4.0 μl of 0.1 M KCN and 2 μl of 1.0 M succinate were added to the sample. The formula for measuring activity is as follows.

Activity = [ΔA600/min × V of assay (ml)]/[(ε of DCIP × V of sample (ml)) × (protein concentration)]

ε of DCIP: 19.1 mM−1

To measure the activity of MitoCom III, 20 μg of the mitochondrial sample was mixed with MitoCom III assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1 mM decylubiquinone, 12.5 mM succinate, 2 mM potassium cyanide, 30 µM rotenone, 40 µM cytochrome C, and 4 mM NaN3). The absorbance of the mixture was then measured the absorbance at 550 nm (A550nm) for 3 min at 30 °C. The activity was calculated using the following formula:

Milli OD/min/µg protein = [(ΔA550nm of sample − ΔA550nm of blank)/min]/[V of sample (ml) × protein concentration],

To measure the activity of MitoCom IV, a mixture of 0.22 mM ferrocytochrome cytochrome C (Merck KGaA) and 0.1 M dithiothreitol (DTT, Merck KGaA) was reacted for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 5 μg of the mitochondrial sample was mixed with MitoCom IV assay buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 120 mM KCl, 11.0 µM ferrocytochrome cytochrome C). The mixture was then measured A500nmat 25 °C, with measurements taken every 10 s for 7 cycles. The activity was calculated using the following formula:

Activity (µmol/min/mg) = (ΔA550nm × 0.2)/[(21.84 × 0.002) × (protein concentration)]

0.2: reaction volume (ml)

0.002: sample volume (ml)

21.84: ΔзmM between ferrocytochrome C and ferricytochrome C at 550 nm.

Measurement of ATP amounts in the brain tissues

The cerebral cortex was homogenized in phenol-saturated TE buffer, and then 15% chloroform and 10% distilled water were added. After vortexing, the sample was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to recover the supernatant for ATP quantification, while the precipitate was used for protein quantification. To quantify ATP in the samples, ATP standard solution was mixed with ATP assay buffer (50 μM Luciferin, 1.25 μg/ml luciferase, 1 mM DTT, 20.875 mM Tricine, 4.175 mM MHJO4, 0.835 mM EDTA, 0.835 NaN3, Merck KGaA). Luminescence was measured using a Victor Nivo™ multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Quantification was performed using a standard curve prepared using ATP standard solution.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, IL, USA) with one-way and two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

References

Tudorache, I. F., Trusca, V. G. & Gafencu, A. V. Apolipoprotein E - A multifunctional protein with implications in various pathologies as a result of its structural features. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 15, 359–365 (2017).

Bea, A. M. et al. Contribution of APOE genetic variants to dyslipidemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, 1066–1077 (2023).

Civeira, F., Martín, C. & Cenarro, A. APOE and familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 35, https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0000000000000937 (2024).

Dove, D. E., Linton, M. F. & Fazio, S. ApoE-mediated cholesterol efflux from macrophages: separation of autocrine and paracrine effects. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C586–C592 (2005).

Gafencu, A. V. et al. Inflammatory signaling pathways regulating ApoE gene expression in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 21776–21785 (2007).

Troutwine, B. R., Hamid, L., Lysaker, C. R., Strope, T. A. & Wilkins, H. M. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 12, 496–510 (2022).

Fahed, G. et al. Metabolic syndrome: updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 786 (2022).

Stamler, R., Stamler, J., Riedlinger, W. F., Algera, G. & Roberts, R. H. Weight and blood pressure:findings in hypertension screening of 1 million Americans. JAMA 240, 1607–1610 (1978).

Andreadou, I. et al. Hyperlipidaemia and cardioprotection: animal models for translational studies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 177, 5287–5311 (2020).

Plump, A. S. et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 71, 343–353 (1992).

Piedrahita, J. A., Zhang, S. H., Hagaman, J. R., Oliver, P. M. & Maeda, N. Generation of mice carrying a mutant apolipoprotein E gene inactivated by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 4471–4475 (1992).

Zhang, S. H., Reddick, R. L., Piedrahita, J. A. & Maeda, N. Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science 258, 468–471 (1992).

Yang, R. et al. Hypertension and endothelial dysfunction in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 2762–2768 (1999).

Lee, S.-H. Lipid-lowering therapy guidelines. Korean. J. Med. 94, 396–402 (2019).

Kirkpatrick, C. F. et al. Nutrition interventions for adults with dyslipidemia: a clinical perspective from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 17, 428–451 (2023).

Onwuzo, C. et al. DASH diet: a review of its scientifically proven hypertension reduction and health benefits. Cureus 15, e44692 (2023).

Mohr, A. E. et al. Effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy in the management of adult dyslipidemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Lipidol. 16, 547–561 (2022).

Kim, K.-Y. & Koh, Y. H. The past, present, and future of silkworm as a natural health food. Food Sci. Nutr. 55, 154–165 (2022).

Kim, E.-J., Lee, S.-Y. & Kim, A.-J. Meta-analysis on the effect of serum lipids levels in silkworm and silkworm pupae. J. Korea Academia-Indust. Cooperation Soc. 21, 273–282 (2020).

Park, S. J., Kim, K.-Y., Baik, M.-Y. & Koh, Y. H. Sericulture and the edible-insect industry can help humanity survive: insects are more than just bugs, food, or feed. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 31, 657–668 (2022).

Ji, S. D. et al. Nutrient compositions of Bombyx mori mature silkworm larval powders suggest their possible health improvement effects in humans. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 19, 1027–1033 (2016).

Ji, S.-D. et al. Comparison of nutrient compositions and pharmacological effects of steamed and freeze-dried mature silkworm powders generated by four silkworm varieties. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 20, 1410–1418 (2017).

Ji, S.-D. et al. Contents of nutrients in ultra-fine powders of steamed and lyophilized mature silkworms generated by four silkworm varieties. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 22, 969–974 (2019).

Lee, J. H., Jo, Y.-Y., Kim, S.-W. & Kweon, H. Analysis of nutrient composition of silkworm pupae in Baegokjam, Goldensilk, Juhwangjam, and YeonNokjam varieties. Int. J. Indust. Entomol. 43, 85–93 (2021).

Islam, M. N. et al. Superoxide dismutase: an updated review on its health benefits and industrial applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 7282–7300 (2022).

Goicoechea, L., Conde de la Rosa, L., Torres, S., García-Ruiz, C. & Fernández-Checa, J. C. Mitochondrial cholesterol: metabolism and impact on redox biology and disease. Redox Biol. 61, 102643 (2023).

Kontis, V. et al. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet 389, 1323–1335 (2017).

Clemente-Suárez, V. J., Beltrán-Velasco, A. I., Redondo-Flórez, L., Martín-Rodríguez, A. & Tornero-Aguilera, J. F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: A narrative review. Nutrients 15, 2749 (2023).

Lee, D. Y. et al. Comparative effect of silkworm powder from 3 Bombyx mori varieties on ethanol-induced gastric injury in rat model. Int. J. Indust. Entomol. 35, 14–21 (2017).

Yun, S.-M. et al. Gastroprotective effect of mature silkworm, Bombyx mori against ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injuries in rats. J. Funct. Foods 39, 279–286 (2017).

Hong, K.-S. et al. Silkworm (Bombyx mori) powder supplementation alleviates alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. J. Funct. Foods 43, 29–36 (2018).

Surra, J. C. et al. Sex as a profound modifier of atherosclerotic lesion development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice with different genetic backgrounds. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 17, 712–721 (2010).

Caligiuri, G., Nicoletti, A., Zhou, X., Törnberg, I. & Hansson, G. K. Effects of sex and age on atherosclerosis and autoimmunity in apoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 145, 301–308 (1999).

Lane-Donovan, C. et al. Genetic restoration of plasma ApoE improves cognition and partially restores synaptic defects in ApoE-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 36, 10141–10150 (2016).

Grootendorst, J., Enthoven, L., Dalm, S., de Kloet, E. R. & Oitzl, M. S. Increased corticosterone secretion and early-onset of cognitive decline in female apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Behav. Brain Res. 148, 167–177 (2004).

Sacks, F. M. et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 3–10 (2001).

Zhou, C. et al. Glutathione S-Transferase α4 alleviates hyperlipidemia- Induced vascular neointimal hyperplasia in arteriovenous grafts via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1097/fjc.0000000000001570 (2024).

Ramassamy, C. et al. Impact of apoE deficiency on oxidative insults and antioxidant levels in the brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 86, 76–83 (2001).

Pei, Z. et al. Exercise reduces hyperlipidemia-induced cardiac damage in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice via its effects against inflammation and oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 13, 9134 (2023).

Chapman, S. et al. The effects of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor ENA713 and the M1 agonist AF150(S) on apolipoprotein E deficient mice. J. Physiol. 92, 299–303 (1998).

Rueter, J., Rimbach, G. & Huebbe, P. Functional diversity of apolipoprotein E: from subcellular localization to mitochondrial function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79, 499 (2022).

Cojocaru, K.-A. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and therapeutic strategies in diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Antioxidants 12, 658 (2023).

Ayata, C. et al. Hyperlipidemia disrupts cerebrovascular reflexes and worsens ischemic perfusion defect. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 33, 954–962 (2013).

Bell, R. D. et al. Author Correction: apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 617, E12 (2023).

Nguyen, P. et al. Mature silkworm powders ameliorated scopolamine-induced amnesia by enhancing mitochondrial functions in the brains of mice. J. Funct. Foods 67, 103886 (2020).

Nguyen, P. et al. The additive memory and healthspan enhancement effects by the combined treatment of mature silkworm powders and Korean angelica extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 281, 114520 (2021).

Kim, Y. & Ghim, H.-r The effects of social skills training program in the elderly. Korean J. Dev. Psychol. 31, 61–82 (2018).

Ji, S. D. et al. Development of processing technology for edible mature silkworm. J. Seric. Entomol. Sci. 53, 38–43 (2015).

Ji, S. D. et al. Production techniques to improve the quality of steamed and freeze-dried mature silkworm larval powder. Int. J. Indust. Entomol. 34, 1–11 (2017).

Kim, K.-Y. et al. New processing technology for steamed-mature silkworms (hongjam) to reduce production costs: employing a high-speed homogenization and spray drying protocol. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 61, 675–688 (2022).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000410 (2020).

Miedel, C. J., Patton, J. M., Miedel, A. N., Miedel, E. S. & Levenson, J. M. Assessment of spontaneous alternation, novel object recognition and limb clasping in transgenic mouse models of amyloid-β and tau neuropathology. JoVE 123, e55523 (2017).

Kandasamy, L. C. et al. Limb-clasping, cognitive deficit and increased vulnerability to kainic acid-induced seizures in neuronal glycosylphosphatidylinositol deficiency mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 30, 758–770 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out with the support of “Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development (Project No. RS-2022-RD010366)”, National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nguyen Minh Anh Hoang: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Thanh Thi Tam Nguyen: Investigation, Data curation, Yoo Hee Kim: Data curation, Visualization, Writing-review & editing, Young Ho Koh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, M.A.H., Nguyen, T.T.T., Kim, Y.H. et al. Preventive, ameliorative, and therapeutic effects of steamed mature silkworms on metabolic disorders caused by loss of apolipoprotein E. npj Sci Food 9, 27 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00392-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00392-0