Abstract

This study assessed the impact of partially replacing wheat flour in croissants with 10% or 15% orange peel (OP), watermelon rind (WR), or melon peel (MP) on sensory properties, in vitro antioxidant capacity (DPPH, total phenolics, flavonoids), and anti-hyperlipidemic activity in rats. Nine groups of rats: a control group (G1), a hyperlipidemic (G2), control diet + 40% croissants (G3), and hyperlipidemic diet and croissants enriched with 10% or 15% of OP (G4, G5), WR (G6, G7), and MP (G8, G9), respectively. OP exhibited the highest antioxidant activity, total phenolics, and flavonoids. Sensory evaluations indicated no significant differences among the croissant treatments. G9 and G7 significantly reduced body weight gain. All treated groups attenuated elevated blood lipid and hepatic enzyme levels compared to G2. G2 showed severe steatosis, necrosis, vacuolation, and inflammatory infiltration in the liver, while these lesions were substantially ameliorated in the treatment groups. Cardiac tissue in G2 presented with fat globules, cardiomyocyte damage, and inflammation, whereas fruit byproduct treatment effectively maintained normal cardiac tissue morphology. This study successfully demonstrated the feasibility of developing anti-hyperlipidemic functional foods by enriching croissants with fruit byproducts in a rat model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipid disorders play a crucial role in the development of atherosclerosis, leading to serious health risks such as heart disorders and stroke1. Hypercholesterolemia (HYP) is a common disorder that significantly increases the risk of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD). This condition is a major risk factor for CVD, which is a significant concern globally, especially in developing nations2,3. Additionally, HYP is a lipid syndrome characterized by elevated cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) serum levels, also known as dyslipidemia. This condition may be accompanied by a decrease in high-density lipoprotein (HDL), an increase in triglycerides, or qualitative fat abnormalities4. According to the World Health Organization, CVD triggered by HYP is the leading cause of death globally5. Approximately 17.9 million people die from CVD, accounting for around 31% of all global deaths. Furthermore, in middle- and low-income nations, over 75% of deaths are due to CVD. Unhealthy diets, tobacco use, fast food consumption, modern lifestyle, and lack of physical activity are the most significant risk factors for CVD5. In Egypt, the WHO indicates that 40% of total deaths are attributed to CVD3. These diseases pose a major public health issue with substantial economic and social implications in terms of healthcare needs, loss of productivity, and premature mortality3.

Every year, the agricultural and food industries produce significant amounts of food waste, which has a negative impact on the environment. Byproducts from fruits are a major concern with direct implications for health, the economy, and the environment6. Finding ways to utilize these byproducts can help reduce food waste, which is crucial for environmental health and food sustainability7. Furthermore, this process can lead to the development of new food products that provide health benefits to consumers8.

Oranges are the most commercially popular fruit in the Citrus genus of the Rutaceae family. They have leathery, oily rinds and juicy, delicious inner flesh that is edible9,10. Egypt is one of the main producers of citrus in the world, with 3.6 million tons produced annually11. The weight of an orange peel (OP) is 35% of the weight of the orange, leading to environmental issues. Its rich sources of phytonutrients, such as flavonoids and phenolic compounds, offer significant health benefits9,12. Additionally, it is considered a food byproduct with health benefits, including anticancer, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and growth-promoting properties in animals13. However, its role in reducing dyslipidemia in animals is limited, especially when fortified with foods.

Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) is a tropical fruit from the cucumber family, known for its juicy and edible fruit. It is widely grown in Africa and Southeast Asia14. Watermelon is the second most grown fresh fruit in the world, with ~100 million tons produced annually on 3 million hectares of land15. Reflecting that about 100 million tons of watermelon are generated globally and that 30–40% of the watermelon is composed of the rind, around 30–40 million tons of watermelon rind (WR) waste are generated yearly16. WR is typically discarded, used as feed, or utilized as fertilizer. However, the WR contains phytochemicals, antioxidants, and functional constituents that can be incorporated into the human diet17. Generally, watermelon is composed of about 93% water, 6% carbohydrates, and small amounts of protein, fat, and minerals. It also contains specific amino acids like arginine and citrulline18. WR is rich in dietary antioxidants such as carotenoids and phenolics, including lycopene, ascorbic acid, flavonoids, and other phenolics. These antioxidants have been studied for their potential health benefits, including reducing the risk of certain diseases like cancer and CVD16,17,19. WR contains moderate quantities of phenolics and flavonoids, which can reduce the oxidation of LDL and quench reactive oxygen radicals, helping to decrease the risk of CVD diseases18. WR has been found to have various health benefits, including anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. It also helps protect the cardiovascular system and improve endothelial function due to its valuable content of arginine and citrulline16,17. However, the protective roles of WR byproducts in dyslipidemic rats and their potential benefits in croissant foods have not been explored yet.

The melon, scientifically known as Cucumis melo L., belongs to the Cucurbitaceae family. It originated in Africa and southwest Asia and later spread to Europe after the Roman Empire. Global melon production is ~28.3 million tons, with China being the largest producer, accounting for 53% of the world’s production20. In Africa, Egypt is the leading producer of melons21. Melons are popular during hot summer months due to their sweet taste and high water content, making them a refreshing and diuretic fruit. Melon is a low-calorie fruit that is free from sodium and fat, making it a nutrient-rich addition to a healthy diet20. The industrial processing of this fruit involves the separation of seeds and peels as byproducts, accounting for 3–7% and 25–44% of the weight of the fruit, respectively22. However, a significant amount of waste is generated during the production procedure, with about 8 to 20 million tons of melon byproducts, such as seeds and peels (MP), being discarded annually worldwide20,22. This waste material can lead to ecological issues, such as insects and rodent proliferation. MP is rich in valuable constituents containing hemicelluloses, cellulose, protein, pectin, and elements, but is often underutilized23,24. Valorizing byproducts such as melon peels (MP), OPs, and WR present an opportunity for sustainable development, and efforts should be made to promote the reuse of melon residues in the food industry.

Recently, bakery products have become a staple in people’s diets and are gaining popularity in the global food market25. However, they are often lacking in nutritional value, high in sugar and saturated fats, and low in dietary fiber26. Croissants are a popular bakery product consumed for breakfast or lunch in many countries worldwide27. Croissants are aerated-flaky pastries with a distinctive layered structure and should have a golden-yellow color27. They are known as “laminated” or “leafy” products, made with yeast in the dough. Biofortification of food products using eco-friendly extracts from food waste is significant in improving the overall quality of new products27. Therefore, their therapeutic roles in plant-based foods to treat certain disorders are necessary and a significant target. The incorporation of fruit waste, such as OP, WR, or melon peel (MP), into croissant formulations for potential preventative effects against hypercholesterolemia remains unexplored. This study explores the potential of valorizing OP, WR, and MP by investigating their antioxidant activity and phenolic compound content. Furthermore, it assesses the impact of incorporating these fruit wastes into croissants, both on their sensory evaluation and their ability to mitigate hypercholesterolemic effects in rats. The research suggests that utilizing these readily available food byproducts as natural additives can lead to the creation of functional foods with preventative properties against hypercholesterolemia. Beyond this, the incorporation of non-edible fruit byproducts into innovative food products offers a sustainable pathway to significantly reduce waste generated by agro-based industries.

Results

Antioxidant, total phenolic, and flavonoid contents

Table 1 demonstrates that the antioxidant activity (DPPH radical scavenging activity) was significantly highest in OP, followed by MP and WR (P < 0.001). Quantitatively, OP’s antioxidant capacity was 116.9% greater than MP’s and 42.56% greater than WR’s. Furthermore, OP exhibited significantly higher levels of both total phenolic (TP) and total flavonoid (TF) compared to WR and MP (P < 0.001). WR also had a significantly higher TF content than MP (P < 0.001). Overall, OP displayed superior antioxidant activity, TP content, and TF content compared to the other tested croissants.

Sensory evaluation of different kinds of croissants

The sensory properties of croissants incorporating different fruit peel powders (OP, WR, MP) at 10% or 15% wheat flour substitution levels are presented in Table 2. Statistical analysis revealed no significant impact of fruit peel enrichment on the overall sensory acceptance of the croissants compared to the control (P > 0.05). Nevertheless, a trend towards lower sensory scores was observed for croissants containing WR across all evaluated attributes. Notably, the 15% MP-enriched croissants received the lowest ratings specifically for texture.

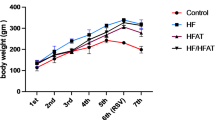

Body and organ weights

The body weight gain (BWG), FI, and FER were significantly affected by the treatment, as shown in Table 3. Feeding rats with a hypercholesterolemic diet (G2) resulted in the highest BWG (78.63% relative to control), while FI (18.75%) and FER (50.62%) were also higher in G2 compared to other groups (P < 0.05). Feed intake (FI) and FER were increased by 18.75% and 50.62%, respectively, relative to the control diet (P < 0.05). Compared to the hypercholesterolemic group, BWG was reduced by 54.5% in G9 and 52.13% in G7 (P < 0.05). Significant reductions (P < 0.05) in the weights of the liver (36.5%), heart (21.4%), and spleen (29.1%) were found in the G9 group (hypercholesterolemic rats fed 15% melon croissants) compared to the hypercholesterolemic diet (G2 group).

Lipid profile

Rats in the hypercholesterolemic group (G2) had the highest values of TG, TC, VLDL, and LDL compared to those in other groups (except for G3; P < 0.05, Table 4). The G5 and G9 groups exhibited reductions in TG (55.5% and 55.12%, respectively) and TC (51.4% and 50.1%, respectively) compared to the G4 (hypercholesterolemic rats) group. The lowest TC levels were observed in rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet and administered 15% MP or OP (G9). TC levels in the control group (G1) were also low, with no significant difference compared to G9 (P > 0.05). In contrast, all croissant-enriched groups (G4–G9) showed significantly reduced TG, TC, and LDL compared to the hypercholesterolemic control group (P < 0.05). HDL levels were higher in G1, G5, G7, and G9, indicating that the incorporation of OP, WR, and MP at 15% significantly improved the lipid profile in rats (P < 0.05). In the G5, G7, and G9 groups, HDL levels were significantly improved by 41.0%, 36.8%, and 3.6%, respectively, compared to rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet. Additionally, HDL levels were similar between G3 and the hypercholesterolemic group (P > 0.05). However, LDL levels were significantly lower in all croissant-enriched groups (10% or 15% OP, WR, and MP) compared to the hypercholesterolemic group (P < 0.05), with the lowest LDL levels observed in G5 (a 65.7% reduction). Compared to the hypercholesterolemic control group, VLDL levels were significantly reduced in all treated groups (P < 0.05). Notably, the most substantial decreases in VLDL were observed in groups G5 (55.5%), G7 (54.2%), and G9 (52.9%). Overall, dietary supplementation with croissants enriched with various levels of OP, WR, or MP significantly improved the lipid profile in hypercholesterolemic rats (P < 0.05) by reducing TG, TC, LDL, and VLDL, and by increasing HDL. Among the treated groups, the lowest TC values were observed in G9, G7, and G5 (P < 0.05).

Liver function and blood proteins

The AST, ALP, and ALT levels were significantly reduced by the inclusion of OP, WR, and MP in the diets of hypercholesterolemic rats (P < 0.05, Table 5) compared to the hypercholesterolemic rats in G3. Significant reductions in AST levels were observed in G5 (40.4%) and G9 (39.56%) when compared to hypercholesterolemic rats. Groups G7 and G9 exhibited significant reductions in ALT levels (37.8% and 39.2%, respectively) when compared to hypercholesterolemic rats. Regarding ALP, significant reductions of 44.06%, 42.9%, and 43.3% were observed in the G5, G7, and G9 groups, respectively, relative to rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet. Enriching croissants with 15% of all tested compounds significantly decreased the levels of hepatic enzymes compared to other groups (P < 0.05). Blood proteins showed a slight increase in all tested groups, with the highest values observed in the G5 group (60.2% increase). Albumin levels were not affected by the treatments (P > 0.05).

Kidney function and glucose

Creatinine levels did not statistically differ among all experimental groups (P > 0.05; Table 6). Rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet (G2) or 40% of control croissant (G3) exhibited the highest levels of urea, while glucose levels were the highest in rats of the G2 group (P < 0.05). Rats in groups G5, G7, and G9 exhibited significantly lower urea levels (by 22.41%, 20.41%, and 21.51%, respectively) compared to the G2 group (hypercholesterolemic diet). Rat groups supplemented with croissants containing OP, MP, or WR (specifically G5, G7, and G9 showed the most pronounced reductions) exhibited significantly lower glucose and urea levels compared to the control groups G2 and G3 (P < 0.05). Rats in groups G5, G7, and G9 exhibited significantly lower glucose levels (by 61.68%, 61.42%, and 61.89%, respectively) compared to the G2 group (hypercholesterolemic diet). The inclusion of 15% OP, MP, or WR in the hypercholesterolemic diet effectively counteracted the hypercholesterolemia-induced elevation of glucose and urea levels in rats.

Liver histopathology

Liver histopathological features observed in control, hypercholesterolemic, and treated rats are depicted in Fig. 1A–J. Control rats (G1) presented normal hepatic architecture, including hepatic cords, central veins, Kupffer cells, and hepatic sinusoids (Fig. 1A). In contrast, hypercholesterolemic rats (G2) exhibited lipid accumulation, hepatic necrosis, and hepatic vacuolation. Specifically, the altered hepatic parenchyma showed hepatocytes with a signet-ring appearance or foamy cells containing minute fat globules (Fig. 1B). Additionally, Fig. 1C illustrates hepatic necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration and hepatocytes containing large, clear vacuoles, some with a signet-ring morphology. Rats in groups G4 (Fig. 1E) and G5 (Fig. 1F) presented normal hepatic sinusoids with minimal perivascular leukocytic infiltrates. Groups G6 (Fig. 1G) and G7 (Fig. 1H) showed moderate hepatic fatty degeneration and small inflammatory cell aggregates. Small inflammatory cell aggregates were also observed in groups G8 (Fig. 1I) and G9 (Fig. 1J).

Liver histopathological features observed in control, hypercholesterolemic, and treated rats are depicted in (A–J). Control rats (G1) presented normal hepatocytes (HP), including hepatic cords, central veins (CN), Kupffer cells, and hepatic sinusoids (A). In contrast, hypercholesterolemic rats (G2) exhibited lipid accumulation, hepatic necrosis, and hepatic vacuolation. Specifically, the altered hepatic parenchyma showed hepatocytes with a signet-ring appearance or foamy cells containing minute fat globules (FG) (B). Additionally, C illustrates hepatic necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration (IN) and hepatocytes containing large, clear vacuoles (HPL), some with a signet-ring morphology. Rats in groups G4 (E) and G5 (F) presented normal hepatic sinusoids with minimal perivascular leukocytic infiltrates. Groups G6 (G) and G7 (H) showed moderate hepatic fatty degeneration and small inflammatory cell aggregates. Small inflammatory cell aggregates were also observed in groups G8 (I) and G9 (J). Normal hepatocytes (HP), fat globules (FG), inflammatory cell infiltration (IN), large, clear vacuoles (HPL), and hepatic necrosis (HN).

Cardiac histopathology

The effects of various treatments on rat cardiac tissues are illustrated in Fig. 2A–J. In the G1 group (Fig. 2A), normal histology of cardiac muscle fibers and vascular tissues was observed. In contrast, rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet (G2 group) exhibited fatty changes within cardiomyocytes and the tunica intima of some cardiac blood vessels (Fig. 2B, C). The heart tissues of hypercholesterolemic rats treated with 40% croissants (G3 group) revealed fat globules within a moderate number of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2D). Hypercholesterolemic rats treated with 10% (Fig. 2E) or 15% (Fig. 2F) orange croissants showed hyaline degeneration and vacuolation in some cardiomyocytes, while the overall structure of cardiac muscle fibers was preserved. Rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet with 10% WR croissants (Fig. 2G) displayed vacuolation in a limited number of myocardial bundles. Notably, the group fed 15% WR croissants (Fig. 2H) presented apparently normal histological sections in most areas of the heart muscle. Vacuolated cardiomyocytes were observed in the heart sections of hypercholesterolemic rats that consumed 10% MP croissants (Fig. 2I). In contrast, the heart sections of hypercholesterolemic rats that consumed 15% MP croissants (Fig. 2J) showed infiltration of a small number of leukocytes, with most of the cardiac tissue preserved.

A Control rats exhibited normal cardiac muscle fiber and vascular tissue histology. B, C Rats on a hypercholesterolemic diet showed fatty changes in cardiomyocytes, inflammatory cell infiltration (IF), and changes in the tunica intima of some cardiac blood vessels. D In hypercholesterolemic rats treated with 40% croissants, heart tissue analysis indicated moderate cardiomyocyte fat globules. In hypercholesterolemic rats treated with 10% E or 15% F OP, some cardiomyocytes showed hyaline degeneration and vacuolation. G Rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet with 10% WR, displayed vacuolation in a limited number of myocardial bundles. H Rats fed with 15% WR presented apparently normal histological sections in most areas of the heart muscle. I Vacuolated cardiomyocytes were observed in the heart sections of hypercholesterolemic rats that consumed 10% MP. J Heart tissues of rats fed 15% MP showed infiltration of a small number of leukocytes, NCM, FG, and IF (scale bar 20 µm).

Discussion

This study uniquely reveals the potential of fruit byproduct-enriched croissants to combat hypercholesterolemia in rats, suggesting their use as functional food additives. The findings indicated that fortifying croissants with 10% or 15% OP, WR, or MP waste maintained sensory properties and demonstrated potential against hypercholesterolemia in rats by improving metabolic markers and organ health. Utilizing these food byproducts as natural additives offers a promising route to functional foods. Furthermore, exploring non-edible fruit seeds in new formulations provides a sustainable waste reduction strategy.

Lifestyle and changes in nutritional habits play a critical role in promoting hypocholesterolemia and atherosclerosis, which can lead to CVD. Bakery products have become a dietary staple and are increasingly popular in the global food market. However, they often lack nutritional value, are high in sugar and saturated fats, and low in dietary fiber. These factors can have a negative impact on human health and contribute to various diseases, including CVDs. Biofortification of food products with eco-friendly food waste presents a significant strategy for enhancing the nutritional value of novel foods. Furthermore, extracts derived from these sources hold therapeutic potential for addressing certain disorders when incorporated into plant-based diets. Notably, this study demonstrates, for the first time, that croissants fortified with various byproduct wastes significantly reduced body weight, improved lipid profiles, and preserved organ histology in hypercholesterolemic rats.

OP is a valuable source of phenolic constituents, including flavonoids and phenolic acids, composing 147.6 mg/g of dry OP12. There are over 4000 different types of flavonoids discovered, each with potential health benefits. Flavonoids derived from citrus peels, such as narirutin and hesperidin, are known for their therapeutic effects on various health conditions. Hesperidin, in particular, is highly valued for its medicinal properties. A study by ref. 28 indicated that the observed attenuation of hesperidin’s protective effects against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and insulin resistance in HG-treated LO2 cells upon miR-149 knockdown indicates that miR-149 is a critical downstream mediator of hesperidin’s action, contributing to its beneficial role in diabetes. OP is a primary natural source of hesperidin, with reported concentrations ranging from 6.98 to 10.80 mg/g of dried matter28. In a related context, the TP in MP ranged from 694.22 to 1271.12 mg/100 g, while the TF varied between 427.69 and 562.89 mg catechin equivalents/100 g20. This study’s findings demonstrate that OP exhibits the highest antioxidant activity, surpassing MP by 116.9% and WR by 42.56%. This superior activity is corroborated by OP’s significantly higher levels of TP and TF in comparison to WR and MP (P < 0.001). Research conducted in Egypt29, indicated that WR yielded ~139.6 ± 2.54 mg GAE/100 g of TP and 40.4 ± 0.92 mg QE/100 g of TF. However, our analysis revealed a TP of 21.12 µg quercetin equivalents/mg and a total TF of 1.16 µg rutin equivalents/mg. According to ref. 20, this indicated that MP exhibited a high TF content of 149.85 ± 13.46 mg/100 g, indicating it as a rich source. The differing levels of TF and TP found in our analysis of MP and WR could be due to the biogeographical origin of the plant material, the harvesting technique employed, and other specific variables. In synopsis, OP displayed greater antioxidant activity, TP content, and TF content than the other croissants evaluated. However, analyzing TP and TF content in fruit byproducts, along with determining these values in the finished croissants, could further enhance the significance of our work. In this study, an untrained panel conducted a sensory evaluation of enriched croissants, assessing appearance, color, odor, texture, taste, and overall acceptability. The results indicated that enriching croissants with various natural functional foods did not significantly affect sensory attributes, suggesting their acceptability within the food industry. Notably, croissants containing 15% OP, MR, or MP demonstrated potential in mitigating the adverse lipid profile associated with a hypercholesterolemic diet. All functional food-enriched croissants were well-received by the participants.

Sensory analysis is crucial for the food industry as it helps in product development, reformulation, and understanding consumer preferences. In this study, sensory evaluation of enriched croissants was conducted by an untrained panel, focusing on appearance, color, odor, texture, taste, and overall acceptability using a 9-point hedonic scale test. The study findings indicated that enriching croissants with various natural functional foods did not significantly alter their sensory attributes, suggesting their potential for acceptance within the food industry. Dairy butter enriched with 1 g/kg of MP was preferred by panelists after 1 month of storage, receiving an average score of 6.7 on a 9-point hedonic scale20. These improvements could be attributed to the high levels of flavonoids and phenolic compounds present in these byproducts, which enhance their stability, taste, and storage ability20. MP exhibited higher levels of anthocyanins, carotenoids, chlorophylls, and lycopene, which offer numerous health benefits for human nutrition30. All functional foods were well-received by the participants. Enriching various foods with MP can enhance their nutritional value, promote public health, and reduce food waste23. This innovative approach also helps in valorizing byproducts that are typically discarded, thereby minimizing the environmental impact.

A hypercholesterolemic diet, characterized by increased fat intake, can induce weight gain and subsequent lipid accumulation in the liver and other organs31. The data presented in Table 3 demonstrated that the group consuming a hypercholesterolemic diet exhibited significantly higher BWG, FI, and FER compared to the control group that fed a standard diet. Croissants incorporating 15% of OP, MR, or MP demonstrated the potential to mitigate hypercholesterolemia by modulating lipid metabolism, consequently influencing body weight and the lipid content of internal organs. These findings align with previous research by ref. 10, which demonstrated that incorporating 10% of a specific ingredient into the diets of rats could modulate glucose levels in both diabetic and hypercholesterolemic conditions. Furthermore, a study by ref. 32 reported that fortified diets containing 9% melon fruit powder significantly counteracted the increase in body weight induced by a hypercholesterolemic diet in diabetic rats. Intriguingly, rats consuming croissants enriched with OP, MR, or WR exhibited a notable trend towards reduced weight gain and lipid buildup, hinting at their potential to counteract these detrimental effects. To delve deeper into this promising observation, we meticulously examined liver tissue samples across all experimental groups, seeking further evidence to substantiate these findings. In this study, rats with hypercholesterolemia exhibited a greater BWG compared to other groups (p < 0.05). Furthermore, rats with hypercholesterolemia treated with OP, WR, and MP showed a reduction in the increase in body weight induced by hypercholesterolemia. Feed intake (FI) was the lowest in rats fed croissants enriched with OP (20%), WR (10%), and MP (10 or 20%). In agreement with our observations10, reported a significant decrease in body weight in diabetic and hypercholesterolemic rats fed a diet containing 10% OP. More recently33, demonstrated that linalool and decanal treatments mitigated weight gain and dyslipidemia induced by a high-fat diet in rats. Several studies have also highlighted the potential of citrus peels to reduce body weight in rats34,35, which aligns with our findings. The observed increase in body weight in the hypercholesterolemic group could be attributed to the higher fat content of their diet, resulting in increased BWG. Notably, the weights of the heart, kidneys, liver, and spleen were significantly lower in the treated groups (P < 0.05). The elevated organ weights in the hypercholesterolemic group might be associated with the increased rate of cholesterol synthesis in the liver due to hypercholesterolemia20,32. Importantly, the weights of the organs did not show significant variations among the rats fed diets fortified with different levels of OP, WR, and MP. These results are consistent with the data reported by ref. 34. However, a significant reduction in body weight was observed due to the fortification of croissants with fruit waste. Nevertheless, further data, such as blood lipid profiles, are required to verify this hypothesis.

Assessing blood lipid profiles is crucial for the diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and obesity. The results indicated that all rats fed fortified croissants containing OP, MP, or WR exhibited a significant reduction in triglyceride, LDL, and cholesterol levels compared to the hypercholesterolemic control group. These findings are consistent with the data reported by ref. 34, who demonstrated that citrus peel powder and its extract significantly reduced triglyceride, LDL, and cholesterol levels in rats with hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia. Consistently, all lipid profiles, including triglycerides, LDL, and cholesterol, were significantly reduced in rats with fatty liver treated with OP extract10. This evidence supports our findings, indicating the regulatory role of OP in lipid metabolism19,36. The higher hesperidin content in OP, compared to other citrus varieties, may contribute to its observed potential in reducing lipid profiles28.

Several studies suggest that hesperidin may help prevent fatty liver degeneration and regulate hepatic lipid metabolism37,38, supporting our findings. Specifically, refs. 9,34 demonstrated that OP extract and powder effectively reduced total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, and glucose levels when incorporated into nutraceutical and functional diets. Furthermore, a study by ref. 10, found that a 10% OP inclusion in the diet of hypercholesterolemic rats significantly lowered total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL. Similarly31, reported a notable decrease in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL in hyperlipidemic rats fed fortified biscuits containing 10% OP.

Regarding the anti-lipidemic effect of WR, it contains a good source of citrulline, which has demonstrated strong inhibitory activity against carbohydrate-hydrolyzing enzymes39. Others have suggested that this effect might be attributed to the polyphenols found in WR, such as chlorogenic acid, gallic acid, caffeic acid, vanillic acid, and quercetin29. Moreover, arginine isolated from WR has also been shown to significantly lower BWG, organ index, LDL-C, serum TG, and TC levels in hyperlipidemic rats, while simultaneously increasing serum HDL-C levels40. Several earlier investigations have revealed the presence of free quercitrin, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, and apigenin-7-O-glucoside in melon peel (MP)41, exhibiting significant results in reducing lipid profiles in hypercholesterolemic rats.

These results are consistent with our data regarding the role of OP in reducing the negative effects of hypercholesterolemia10,34 via reducing the fat accumulation in the blood. Remarkably, administering a mere 200 mg of WR extract orally led to a significant reduction in key lipid markers such as total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL in rats grappling with both diabetes and a high-fat diet42. The anti-lipidemic effects of WR have also been demonstrated in glucose-induced male albino mice through the reduction of blood glucose levels43. The capacity of WR to reduce blood lipids is likely attributed to its l-citrulline content, in which the latter is converted to arginine, a precursor for nitric oxide synthesis. Nitric oxide plays a critical role in vasodilation, leading to reduced blood pressure and improved blood flow, which can facilitate the transport and metabolism of lipids16.

Diets enriched with citrus peel nutraceuticals demonstrated greater efficacy in regulating glycemic and lipidemic parameters compared to those supplemented with citrus peel powder. Notably, the flavonoids present in OP have been observed to stimulate the synthesis of cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) in the liver, thereby enhancing cholesterol metabolism44. This metabolic pathway reduces the accumulation of cholesterol in the bloodstream and tissues. The antihyperlipidemic effect of OP is attributed to the ability of its flavonoids to activate PPAR-α in various organs, including fat, liver, and muscle, of hyperlipidemic hamsters45. The data revealed multiple mechanisms underlying the anti-lipogenic bioactivity of OP, including the downregulation of key enzymes involved in triacylglyceride and cholesterol biosynthesis46. Similarly,33 reported that phytochemicals in citrus peels can reduce hepatic lipids by promoting and accelerating fatty acid oxidation through the stimulation of PPAR-α and CPT-1 expression. PPAR-α plays a crucial role in various aspects of fatty acid metabolism. Specifically, OP can reduce the activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase, HMG-CoA synthase, and HMG-CoA reductase, while upregulating cholesterol-7α-monooxygenase to promote lipid metabolism. Moreover, the results of ref. 24 found that LDL and total cholesterol levels decreased in hyperlipidemic mice treated with bitter melon extract for 12 weeks. Similarly, ref. 47 determined that a 5% inclusion of citron melon peel powder was the most effective treatment for reducing total cholesterol, LDL, and triglyceride levels compared to other groups. Furthermore, the outcomes of ref. 32 demonstrated that feeding rats a high-fat diet with 3%, 6%, and 9% melon peel resulted in reduced blood lipids. Our study also recorded a significant decrease in serum total cholesterol and triglycerides in all groups treated with OP.

Utilizing fruit waste materials to target fatty acid metabolism enzymes in dietary therapies presents a cost-effective and accessible strategy for addressing lifestyle-related diseases such as obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypercholesterolemia. A study by ref. 34 reported a notable increase in HDL levels in hypercholesterolemic rats consuming functional foods like OP. Similarly, ref. 31 observed an improvement in HDL levels in hyperlipidemic rats fed fortified biscuits containing 10% OP. Furthermore, naringin has been shown to substantially reduce the mRNA expression of FAS and SREBP-1c, while concurrently increasing the mRNA expression of the PPARα gene40.

Liver enzyme levels were reduced in hypercholesterolemic rats consuming diets containing 10% OP10. This improvement in liver function, evidenced by the restoration of enzymes affected by a hypercholesterolemic diet, may be attributed to the flavonoids present in OP44. Additionally, ref. 48 demonstrated that fortifying crackers with watermelon seed extract significantly reduced the elevated AST and ALT levels in hyperlipidemic rats. These findings align with our data, which demonstrated a notable decrease in hepatic enzyme levels across all fortified diet groups. This suggests that flavonoids may exert a hypolipidemic effect by enhancing liver function through their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in hyperlipidemic hamsters. Furthermore, MP contains bioactive compounds such as β-carotene, lycopene, vitamin C, and flavonoids, which exhibit anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects30.

In hypercholesterolemic rats, a 10% OP diet led to the restoration of kidney markers affected by the condition10, suggesting a renal protective effect of OP. This protective effect is attributed to its TF content44, a finding supported by the present study. These findings are consistent with previous research by ref. 9,32, who also observed a significant decrease in serum urea and creatinine levels in diabetic hypercholesterolemic rats fed OP, likely due to its higher antioxidant activity compared to other phytochemicals. Similar effects of OPs on urea and creatinine levels have been reported in other studies. Furthermore32, noted a significant decrease in urea and creatinine levels with increasing levels of melon peel in the diets of diabetic hypercholesterolemic rats. Recent research by ref. 48, demonstrated that fortifying crackers with watermelon seed extract significantly reduced the elevated creatinine and urea levels in hyperlipidemic rats.

Assessing organ integrity in animals fed or treated with novel foods or undergoing disease prevention strategies can be a valuable tool for providing detailed insights into how these materials affect organ integrity in target tissues. The authors suggest that the bioactive compounds present in the fruit byproducts used to produce the novel croissants may help protect organs from hyperlipidemic-induced damage in rats. Our observations revealed that feeding rats hyperlipidemic diets notably increased lipid accumulation, hepatic necrosis, and hepatic vacuolation. In contrast, rats fed croissants fortified with OP, WR, and MP exhibited regenerating hepatocytes, with significantly reduced activation of Kupffer cells and vacuolation in hepatic tissues. These findings are consistent with previous work by ref. 42, who reported that WR extract can protect hepatic tissues from high-fat diet-induced liver injury. Additionally, the administration of flavonoids isolated from OP has been observed to improve liver pathology in hyperlipidemic hamsters44. OP extract also enhanced hepatic architecture towards near normalcy, exhibiting fewer fat globule deposits and less sinusoidal dilation in rats with hyperlipidemia49. However, further immunohistopathological studies, integrated with transmission electron microscopy, are required to confirm these results.

The heart is a vital organ for life, ensuring that all parts of the body receive the necessary oxygen and nutrients while removing waste products. The accumulation of lipids in vascular tissues due to a hyperlipidemic diet can negatively impact cardiac physiology. This study revealed that rats on a hypercholesterolemic diet developed fatty changes in cardiomyocytes and the tunica intima of some cardiac blood vessels. In contrast, hyperlipidemic rats consuming diets fortified with OP, MP, and WR exhibited hyaline degeneration and vacuolation in a subset of cardiomyocytes, with preserved overall cardiac muscle fiber structure. Notably, OP fortification was associated with limited myocardial bundle vacuolation. Moreover, hyperlipidemic rats fed OP, WR, or MP generally showed normal heart muscle histology, indicating potential cardioprotective effects of these food industry byproducts when added to croissant products. Histopathological assessment of rat hepatic tissues demonstrated that OP or WR could alleviate the degenerative impairment of fatty hepatic cells in hyperlipidemic rats40. The phenolic and flavonoid compounds found in OP are the principal components of citrus peels and exhibit a strong lipid-lowering effect, safeguarding the cardiac tissues in hyperlipidemic rats. The antihyperlipidemic activity of citrus peels is attributed to phytochemicals such as naringin and other essential nutrients50, suggesting their potential as cardioprotective agents by preventing dyslipidemia. Our results emphasize the antihyperlipidemic potential of OP and enhance the scientific consideration of its antihyperlipidemic properties as an agro-waste, which may be crucial for its future use as a dietary approach for managing hyperlipidemia.

Gene expression analysis, immune-reaction assays, and western blotting are key techniques for validating our findings. A limitation of this study is the use of untrained panelists for sensory evaluation, whose opinions may be more subjective and less consistent than those of trained experts. However, limited analytical resources preclude us from performing these validation assays at this time. Exploring additional genes related to fatty acid oxidation could provide further support, although this has been discussed in detail in the discussion section.

Finally, the study found that supplementing croissants with 10% or 15% of waste byproducts such as OPs, WR, and melon peels (MP) did not significantly affect sensory evaluation. The study also elucidated the potential benefits of incorporating OP, WR, and MP in croissants to mitigate hypercholesterolemic effects in rats by reducing lipid profiles and liver enzymes, improving kidney function, blood proteins, and maintaining organ histology. These findings suggest that using food byproducts and waste as natural additives in food products can create functional foods to prevent hypercholesterolemia. Utilizing non-edible fruit seeds in developing new food products also presents a sustainable solution to reduce waste in agro-based industries. Further research is needed to confirm these results and evaluate their implications for human health.

Methods

Sources of materials and ethical statement

The wheat flour (72%), sugar, salt, vegetable oil, skimmed milk powder, baking powder, dry yeast, orange (Citrus sinensis L), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), and melon (Cucumis melo L) used in this research were purchased from a local market in Zagazig, Egypt. Minerals, casein, cellulose, and vitamins were obtained from El-Gomhoria Company (Zagazig, Egypt). Gallic acid, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl were supplied by Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

All procedures and experimental protocols complied with Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 22 September 2010, legislation on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. The experimental procedures were approved by the Zagazig University Scientific Research Ethics Committee (Ethical code: ZU-IACUC/2/F/174/2022) and conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.

Preparation of orange peel (OP), watermelon rind (WR), and melon peels (MP)

Following thorough washing with distilled water and detachment from cleaned fresh fruits, OPs and WR were cut into small pieces, rinsed with water on plates, and dried at 45 °C for 48 h in an air oven. Melon peels (MP) underwent a similar initial preparation (washing, detachment, and cutting), but were then specifically soaked in a 0.1% sodium metabisulfite solution for 30 min prior to drying at 45 °C for 48 h in an air oven51. All dried materials were subsequently ground into a fine powder using a laboratory mill and stored in polyethylene bags at 5 °C until use.

Preparation of croissants

The croissant was prepared according to Shalaby & Yasin52 with some modifications. The ingredients used were wheat flour (72%), sugar (4 g), powdered milk (12 g), vegetable oil (10 g), baking powder (2 g), yeast (2 g), vanilla (0.5 g), salt (0.5 g), and water as needed. Seven different croissant samples were prepared (C and T1–T6) using wheat flour and various fruit peel powders such as orange, watermelon, and melon in ratios of 100:0, 90:10, and 85:15, respectively. The control samples were prepared according to the ingredients described above (C), while the other samples were prepared as C and replaced wheat flour with 10 or 15% from OP (T1 and T2), WR (T3 and T4), and MP (T5 and T6), respectively (Table 7).

Antioxidant assay

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was performed for OP, MP, and WR. Radical scavenging action of the OP, MP, and WR samples was assessed by blenching of the purple solution of the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl hydrate (DPPH) assay according to Gülçin et al.53, expressed as µM Trolox /mg extract of OP, MP, or WR.

Total flavonoid (TF) and phenolic (TP) contents

TP content and TF content were quantified in OP, MP, and WR and expressed as µg of quercetin equivalent/mg and µg of rutin equivalent/mg, respectively, following the methods described by ref. 54 and Folin-Ciocalteau based on the ref. 55, respectively.

Sensory evaluation

Sensory parameters such as color, odor, taste, texture, appearance, and acceptability were evaluated for seven croissant products. When developing a new food product, it is important to consider sensory features and consumer approval. A hedonic scale assessment was conducted to assess the acceptability of the croissants using a blend of people (number of participants = 20). Twenty untrained panelists used a ten-point hedonic scale to rate the appearance, color, odor, texture, taste, and overall acceptability of the products. The scale ranged from 1 (disliked it very much) to 9 (liked it very much). The most common is the 9-point hedonic scale56, which ranges from 1: Dislike Extremely, 2: Dislike Very Much, 3: Dislike Moderately, 4: Dislike Slightly, 5: Neither Like nor Dislike (Neutral point), 6: Like Slightly, 7: Like Moderately, 8: Like Very Much and 9: Like Extremely.

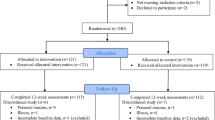

Biological experiment

Forty-five adult male Wistar albino rats weighing 120 ± 5 g were housed in stainless steel cages in the Animal Facility at the Food Science Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Zagazig University. The rats were housed at a temperature of 25 °C under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with food and water provided ad libitum. A 2-week adaptation period was allowed before the start of the experiment. The basal diet was prepared according to the procedure illustrated by 57.

The rats were randomly separated into nine groups, comprising five rats in each group.

-

(1)

The first group (G1): rats received normal diets.

-

(2)

The second group (G2): rats were fed a hypercholesterolemic diet for 6 weeks, which was formulated by supplementing a basal diet with 16% fat, 2% cholesterol powder, and 0.25% cholic acid, following the methodology described by ref. 31. This supplementation involved substituting an equivalent amount of starch in the basal diet (Table 8).

-

(3)

The third group (G3): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 40% of the control croissant.

-

(4)

The fourth group (G4): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 10% orange-enriched croissants.

-

(5)

The fifth group (G5): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 15% orange-enriched croissants.

-

(6)

The Sixth group (G6): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 10% watermelon-enriched croissants.

-

(7)

The seventh group (G7): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 15% watermelon-enriched croissants.

-

(8)

The eighth group (G8): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 10% melon-enriched croissants.

-

(9)

The ninth group (G9): rats were treated with a hypercholesterolemic diet as described in G2 and fed with 15% melon-enriched croissants.

During the investigational period, 40% of the starch in the diet was replaced with croissants. Live body weights of the rats were individually measured using a digital electronic balance (WANT, Jiangsu, China, sensitivity ±0.01 g) at the start and end of the experiment to determine BWG. Moreover, food intake (FI) was calculated weekly based on the amount of food consumed. The feed conversion ratio (FCR) was then determined using BWG, the duration of the experiment in days, and FI. After 6 weeks of treatment and a feeding trial, blood samples were collected, and the rats were sacrificed to discard the liver and kidney tissues for histological examination.

Blood and tissue sampling

Following a 12-h fasting period at the end of the experiment, blood samples (n = 5 per group) were collected from the tail vein of anesthetized rats. Anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (50 mg/kg bw)/xylazine (10 mg/kg bw) solution. Blood was collected into sterile tubes without EDTA. Blood samples were allowed to clot for 1 h at room temperature to facilitate serum separation. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min to obtain the serum. The resulting serum samples were then aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until further analysis of blood parameters. The liver, kidney, heart, and spleen tissues were extracted from the abdominal cavity of rats and individually weighed using a digital electronic balance (WANT, Jiangsu, China, sensitivity ±0.01 g). Subsequently, samples of heart and liver were preserved in formalin for histological analysis.

Biochemical analysis

The albumin and total protein levels in the serum were measured using commercial kits provided by SpinReact Company (Girona, Spain) following the instructions in the provided pamphlet. The serum glucose level was measured using the Glucose Assay Kit (CATALOG# 81693) following the procedure outlined by Barham and Trinder58.

Cholesterol (TC), Triglycerides (TG), and High-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) were determined according to refs. 59,60 and ref. 61, respectively. The ELISA kits for determining TG, TC, and HDL were also provided by SpinReact Company (Girona, Spain) and followed the company’s instructions.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) levels were calculated according to instructions in the provided pamphlet. VLDL-C levels (in mg/dL) were estimated by dividing triglyceride levels (mg/dL) by 5, according to the method described by Oliveira et al.62.

Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were calculated via the method outlined by ref. 63. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was measured following the protocol by ref. 64. Urea and creatinine levels were analyzed using Biodiagnostic (Giza, Egypt) kits based on the procedures illustrated by refs. 65,66, respectively. All assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions.

Histopathological procedure

Immediately after euthanasia, liver and heart tissue specimens were harvested from rats and directly immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for a fixation period of 48 h. Subsequently, the tissues underwent a dehydration process using a sequential series of increasing ethanol concentrations (70%, 80%, 95%, 95%, and 100%), followed by clearing in xylene and embedding in paraffin. Paraffin sections with a thickness of 5 µm were obtained using a Leica RM 2155 microtome (England), stained with hematoxylin and eosin using a consistent staining procedure, and examined under a light microscope67. Representative photomicrographs were captured using a Leica EC3 digital camera (Leica, Germany) mounted on a Leica DM500 light microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data were compiled and edited in Microsoft Excel. Statistical evaluations were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25). The assumptions of independent observations, normality of residuals, and homogeneity of variances were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test before performing the ANOVA. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, and the significant differences between treatments were assessed by a post hoc review of the Duncan test. Findings were informed as mean ± standard error. P values were determined as significant (P ≤ 0.05).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Soppert, J., Lehrke, M., Marx, N., Jankowski, J. & Noels, H. Lipoproteins and lipids in cardiovascular disease: from mechanistic insights to therapeutic targeting. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 159, 4–33 (2020).

Jamison, D. T. Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition: improving health and reducing poverty. Lancet 391, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60097-6 (2018).

Ramadan, A. et al. Evaluating knowledge, attitude, and physical activity levels related to cardiovascular disease in Egyptian adults with and without cardiovascular disease: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 24, 1107 (2024).

Woudberg, N. J., Goedecke, J. H. & Lecour, S. Protection from cardiovascular disease due to increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in African black populations: myth or reality? Ethn. Dis. 26, 553 (2016).

WHO. World Health Statistics 2020: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals (World Health Organization, 2020).

Rațu, R. N. et al. Application of Agri-food by-products in the food industry. Agriculture 13, 1559 (2023).

Muurmann, A. T. et al. Framework for valorizing waste- and by-products through insects and their microbiomes for food and feed. Food Res. Int. 187, 114358 (2024).

Gupta, A. K. et al. Slaughterhouse blood: a state-of-the-art review on transforming by-products into valuable nutritional resources and the role of circular economy. Food Biosci. 61, 104644 (2024).

Arief, R. Q., Prasetyaning, L., Purnamasari, R., Oktorina, S. & Hidayati, S. Determining the effect of orange peel extract in water on total cholesterol fluctuations in HFD-induced mice. J. Health Sci. Prev 7, 119–124 (2023).

Hammad, E., Kostandy, M. & El-Sabakhawi, D. Effect of feeding sweet orange peels on blood glucose and lipid profile in Diabetic and hypercholesterolemic. Bull. Natl. Nutr. Inst. Arab Repub. 51, 70–90 (2018).

FAS. Egypt: Citrus Annual https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/egypt-citrus-annual-8 (2024).

Sharma, K., Mahato, N., Cho, M. H. & Lee, Y. R. Converting citrus wastes into value-added products: economic and environmently friendly approaches. Nutrition 34, 29–46 (2017).

Jimenez-Lopez, C. et al. Agriculture waste valorisation as a source of antioxidant phenolic compounds within a circular and sustainable bioeconomy. Food Funct. 11, 4853–4877 (2020).

Mujaju, C. et al. Genetic diversity in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) landraces from Zimbabwe revealed by RAPD and SSR markers. Hereditas 147, 142–153 (2010).

Heindel, J. J., Lustig, R. H., Howard, S. & Corkey, B. E. Obesogens: a unifying theory for the global rise in obesity. Int. J. Obes. 48, 449–460 (2024).

Meghwar, P. et al. Nutritional benefits of bioactive compounds from watermelon: a comprehensive review. Food Biosci. 104609, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104609 (2024).

Dubey, S., Rajput, H. & Batta, K. Utilization of watermelon rind (Citrullus lanatus) in various food preparations: a review. J. Agric. Sci. Food Res. 12, 5–7 (2021).

Manivannan, A., Lee, E. S., Han, K., Lee, H. E. & Kim, D. S. Versatile nutraceutical potentials of watermelon—a modest fruit loaded with pharmaceutically valuable phytochemicals. Molecules 25, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules2522525 (2020).

Park, H. Y. et al. Effect of oral administration of water-soluble extract from citrus peel (Citrus unshiu) on suppressing alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats. Food Chem. 130, 598–604 (2012).

Farida, B.-D., Aoun, S., Cherifi, A. & Lynda, D. Melon peel powder: phytochemical screening, antioxidant contents, functional properties food application. J. Food Sci. Res 7, 1–14 (2022).

Dube, J. G. D. & Maphosa, M. Watermelon production in Africa: challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 27, 211–219 (2021).

Gomez-Garcia, R., Campos, D. A., Aguilar, C. N., Madureira, A. R. & Pintado, M. Valorization of melon fruit (Cucumis melo L.) by-products: phytochemical and biofunctional properties with emphasis on recent trends and advances. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 507–519 (2020).

Silva, M. A., Albuquerque, T. G., Alves, R. C., Oliveira, M. B. P. & Costa, H. S. Melon peel flour: utilization as a functional ingredient in bakery products. Food Funct. 15, 1899–1908 (2024).

Yoon, N. A. et al. Anti-diabetic effects of ethanol extract from bitter melon in mice fed a high-fat diet. Dev. Reprod. 21, 259 (2017).

Owusu-Apenten, R. & Vieira, E. In Elementary Food Science 499–512 (Springer, 2022).

Morreale, F., Angelino, D. & Pellegrini, N. Designing a score-based method for the evaluation of the nutritional quality of the gluten-free bakery products and their gluten-containing counterparts. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 73, 154–159 (2018).

Thota, N. et al. Lowering added sugar and increasing fibre in croissants using short-chain fructooligosaccharides (sc-FOS). Food Hydrocoll. 150, 109761 (2024).

Samota, M. K. et al. Hesperidin from citrus peel waste: extraction and its health implications. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 15, 71–99 (2023).

Wahdan, O. A., Bassuony, N. I., Abd El-Ghany, Z. M. & El-Chaghaby, G. A. Watermelon white rind as a natural valuable source of phytochemicals and multinutrients. Egypt. J. Nutr. 32, 87–102 (2017).

Gómez-García, R. et al. A chemical valorisation of melon peels towards functional food ingredients: bioactives profile and antioxidant properties. Food Chem. 335, 127579 (2021).

Aly-Aldin, M. M. Influence of Honeydew Melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit fractions on the diabetic hypercholesterolemic rats. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci., B Zool. 14, 89–100 (2022).

Wang, Q.-S., Li, M., Pan, S., Ren, J. N. & Fan, G. Regulation of lipid metabolism by the major components of orange essential oil in high-fat diet mice. Food Biosci. 59, 103965 (2024).

Ashraf, H., Butt, M. S., Iqbal, M. J. & Suleria, H. A. R. Citrus peel extract and powder attenuate hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia using rodent experimental modeling. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 7, 870–880 (2017).

Mbegeze, M. B., Stephano, F., Nondo, R. S. O., Nyandoro, S. S. & Munissi, J. J. E. Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic effects of flavonoids in streptozotocin-nicotinamide induced diabetic Wistar rats. J. Biol. Act. Prod. Nat. 14, 327–342 (2024).

Mollace, V. et al. Hypolipemic and hypoglycaemic activity of bergamot polyphenols: From animal models to human studies. Fitoterapia 82, 309–316 (2011).

Liu, S. et al. Hesperidin methyl chalcone ameliorates lipid metabolic disorders by activating lipase activity and increasing energy metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 1869, 166620 (2023).

Morshedzadeh, N., Ramezani Ahmadi, A., Behrouz, V. & Mir, E. A narrative review on the role of hesperidin on metabolic parameters, liver enzymes, and inflammatory markers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Sci. Nutr. 11, 7523–7533 (2023).

Balogun, O., Otieno, D., Brownmiller, C. R., Lee, S. O. & Kang, H. W. Effect of Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) Extract on carbohydrates-hydrolyzing enzymes in vitro. Agriculture 12, 772 (2022).

Yu, X., Meng, X., Yan, Y., Wang, H. & Zhang, L. Extraction of naringin from pomelo and its therapeutic potentials against hyperlipidemia. Molecules 27, 9033 (2022).

Ezzat, S. M., Raslan, M., Salama, M. M., Menze, E. T. & El Hawary, S. S. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity and UPLC-MS/MS profiling of the peels and pulps of Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis and Cucumis melo var. reticulatus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 237, 245–254 (2019).

Jibril, M. M. et al. Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) leaf extract attenuates biochemical and histological parameters in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Food Biochem. 46, e14058 (2022).

Jessa, L. et al. The Potency of antidiabetic properties of watermelon (citrullus lanatus) rind ethanolic extract in glucose-induced male albino mice. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 10, 118–131 (2025).

Ling, Y. et al. Hypolipidemic effect of pure total flavonoids from peel of Citrus (PTFC) on hamsters of hyperlipidemia and its potential mechanism. Exp. Gerontol. 130, 110786 (2023).

Naiel, M. A. E., Negm, S. S., Ghazanfar, S., Shukry, M. & Abdelnour, S. A. The risk assessment of high-fat diet in farmed fish and its mitigation approaches: a review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 107, 948–969 (2023).

Lin, L.-Y., Huang, B.-C., Chen, K.-C. & Peng, R. Y. Integrated anti-hyperlipidemic bioactivity of whole Citrus grandis [L.] osbeck fruits—multi-action mechanism evidenced using animal and cell models. Food Funct. 11, 2978–2996 (2020).

El-Sayed, M. M., EL-Sherif, F. E.-Z., Mahran, M. Z. & Ahmed, E. S. Biochemical and nutritional studies of pulp, seeds, and peels of citron melon (C itrullus sp.) among obese albino rats. J. Home Econ. 31, 14–24 (2021).

AlMasoud, N. et al. Impact of watermelon seed fortified crackers on hyperlipidemia in rats. Pak. Vet. J 44, 1291–1297 (2024).

Parveen, S. et al. Anti-hyperlipidemic effects of citrus fruit peel extracts against high fat diet-induced hyperlipidemia in rats. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 12, 2226–2232 (2021).

Mallick, N. & Khan, R. A. Antihyperlipidemic effects of Citrus sinensis, Citrus paradisi, and their combinations. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 8, 112–118 (2016).

Hanafi, N. A. M. et al. Optimized removal process and tailored adsorption mechanism of crystal violet and methylene blue dyes by activated carbon derived from mixed orange peel and watermelon rind using microwave-induced ZnCl2 activation. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 28415–28427 (2024).

Shalaby, S. M. & Yasin, N. M. Quality characteristics of croissant stuffed with imitation processed cheese containing microalgae Chlorella vulgaris biomass. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wjdfs.2013.8.1.1118 (2013).

Gülçin, I., Küfrevioǧlu, Öİ, Oktay, M. & Büyükokuroǧlu, M. E. Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiulcer and analgesic activities of nettle (Urtica dioica L.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 90, 205–215 (2004).

Zhishen, J., Mengcheng, T. & Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 64, 555–559 (1999).

Roy, S. A., Pal, T. K. & Bhattacharyya, S. Effect of thermal processing on in vitro antioxidant potential of Capsicum (Capsicum annuum) of different ripening stages. J. Pharm. Res. 8, 1751–1756 (2014).

Wichchukit, S. & O’Mahony, M. The 9-point hedonic scale and hedonic ranking in food science: some reappraisals and alternatives. J. Sci. Food Agric 95, 2167–2178 (2015).

Shehata, M. M. & Soltan, S. S. Effects of bioactive component of kiwi fruit and avocado (fruit and seed) on hypercholesterolemic rats. World J Dairy Food Sci 8, 82–93 (2013).

Youssef, M. K. E., Youssef, H. M. & Mousa, R. M. Evaluation of antihyperlipidemic activity of citrus peels powders fortified biscuits in albino induced hyperlipidemia. Food Public Health 4, 1–9 (2014).

Barham, D. & Trinder, P. An improved colour reagent for the determination of blood glucose by the oxidase system. Analyst 97, 142–145 (1972).

Richmond, W. Preparation and properties of a cholesterol oxidase from Nocardia sp. and its application to the enzymatic assay of total cholesterol in serum. Clin. Chem. 19, 1350–1356 (1973).

Fossati, P. & Prencipe, L. Serum triglycerides determined colorimetrically with an enzyme that produces hydrogen peroxide. Clin. Chem. 28, 2077–2080 (1982).

Burstein, M., Scholnick, H. & Morfin, R. Rapid method for the isolation of lipoproteins from human serum by precipitation with polyanions. J. Lipid Res. 11, 583–595 (1970).

Oliveira, M. J. et al. Evaluation of four different equations for calculating LDL-C with eight different direct HDL-C assays. Clin. Chim. Acta 423, 135–140 (2013).

Raza, S. H. A. et al. Krüppel-like factors family regulation of adipogenic markers genes in bovine cattle adipogenesis. Mol. Cell Probes 65, 101850 (2022).

Klein, B. & Kaufman, J. H. Automated alkaline phosphatase determination: III. evaluation of phenolphthalein monophosphate. Clin. Chem. 13, 290–29 (1967).

Patton, C. J. & Crouch, S. Spectrophotometric and kinetics investigation of the Berthelot reaction for the determination of ammonia. Anal. Chem. 49, 464–469 (1977).

Larsen, K. Creatinine assay by a reaction-kinetic principle. Clin. Chim. Acta 41, 209–217 (1972).

Suvarna, K. S., Layton, C. & Bancroft, J. D. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU- DSPP- 2024-238).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.E., S.M.M., and S.A.A.: conceptualization, data curation, and methodology; M.E.S., A.K.A., and G.A.S.: investigation, software, supervision, and writing—original draft; G.A., E.H.A., S.A.A., and H.E.: project administration and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, H.E., Mansour, S.M., Aldhalmi, A.K. et al. Investigating the anti-hypolipidemic effects of croissants enriched with fruit byproducts in a rat model. npj Sci Food 9, 130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00482-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00482-z