Abstract

The effects of specific macronutrients on autoimmune diseases (ADs) independent of total calorie intake have rarely been studied. The study aims to decipher the associations of relative macronutrient intake with risk of ADs and identify potential circulating metabolic mediators. We performed a mendelian randomization (MR) study in Europe, using genetic variants associated with relative macronutrient intake among 268,992 participants, and genetic variants with 17 ADs outcomes from two large-scale biobanks including up to 951,301 participants. Eight potential causal associations were identified and further classified into three levels, according to the robustness of MR results. Tier 1 evidence included associations of relative protein and carbohydrate intake with risk of psoriasis, which was demonstrated by the fact that the association remained significant in the meta-analysis of two biobanks. For each 4.8% increment in relative protein intake and each 16.1% increment in relative carbohydrate intake, the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association with psoriasis risk were 0.84 (0.71–0.99) and 1.20 (1.02–1.41), respectively, as determined by the MR meta-analysis. To explain above associations, a two-step MR framework was further to identify five potential mediated metabolic biomarkers, using the genetic variants for 233 metabolic traits in up to 136,016 participants. This study provides insights into the clinical significance of dietary macronutrient intake and circulating metabolic biomarkers in the context of ADs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases (ADs) are a hand of disorders caused by aberrant immune responses against self-tissues1. To date, over 100 subtypes of ADs have been identified, affecting a total of 5–9% of the world population2. ADs have also been reported to be associated with the development of mental disorders, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases, posing a serious threat to individual quality of life2,3,4. Notably, most ADs are chronic and require lifelong therapies5. It is imperative to develop preventive strategies for ADs through the identification of potential causal factors.

Apart from well-established risk factors for ADs such as specific genetic backgrounds6, the relationship between energy intake and ADs has received much attention in recent years7,8. It is noteworthy that controlling energy intake through dietary regulation has emerged as an efficacious strategy for averting diseases onset9. Macronutrient, including protein, carbohydrate and fat, are considered as the primary dietary source of energy for the human body10. In some observational studies and animal models, macronutrient has been investigated as potential etiological factors in specific ADs, such as inflammatory bowel disease11, systemic lupus erythematosus12, and hypothyroidism13. However, previous studies have predominantly focused on “absolute intake” of specific macronutrient rather than “relative intake”. The determination of “absolute intake” has been primarily attributed to factors such as body size and physical activity14, which may lead to potential bias in population-based study. Besides, conducting clinical trials to investigate the effects of various macronutrient compositions within a fixed caloric intake range is a laborious work.

Metabolites, which serve as the products of metabolic reactions, have emerged as promising disease biomarkers. Their concentrations are modulated by a variety of factors, including dietary intake15. Therefore, deciphering the metabolic characteristics underlying dietary factors that influence disease can elucidate metabolic mediating effects in individuals with varying dietary habits.

In the study, we employed a Mendelian randomization (MR) design to systematically investigate potential causal association between relative macronutrient intake and risk of 17 ADs outcomes among two large-scale biobanks. MR is a popular statistical method to infer causality, when certain assumptions are met16. Based on the robustness of the MR results, we stratified them as tier 1, 2, and 3 evidence. We also investigated potential circulating metabolic mediators using a two-step MR framework. The study may emphasize the clinical significance of dietary macronutrient intake in the context of ADs and underscore the potential for disease surveillance and early detection in individuals with diverse dietary backgrounds.

Results

Study design

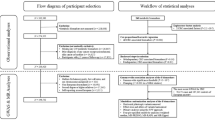

This study is based on a hypothesis-free design, using two-sample MR to systematically explore the potential association between relative macronutrient intake and risk of 17 ADs outcomes in Europe, using two large-scale biobanks. Meta-analysis of MR results from two biobanks was further performed to get robust estimates. Based on the robustness of the MR results, we stratified them as tier 1, tier 2, and tier 3 evidence. Finally, a two-step MR framework was used to investigate potential circulating metabolic mediators. The overall workflow of the study design is given in Fig. 1. Adherence to three fundamental assumptions is crucial for ensuring the validity of causal estimates in MR studies17,18: First, the genetic variants exhibit a significant association with the exposure. Second, the genetic variants should be independent of confounders. Third, the impact of genetic variants on the outcome is solely mediated through the exposure. This study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE-MR checklist19 (Supplementary Data 1).

Details regarding all data sources and sample sizes are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The data utilized in this study were sourced from publicly available studies with the consent and ethical approval of relevant participants, ethical approval from the institutional review board was not required for this study.

MR analysis of relative macronutrient intake on ADs

We identified 24 instrumental variables (IVs) related to relative macronutrient intake that were potentially associated with plausible confounders (Supplementary Table 2), including dietary factors other than macronutrients, smoking, alcohol consumption, and disease status. To better satisfy the second hypothesis of MR mentioned above, these IVs were excluded from the analysis. The included IVs of relative macronutrient intake used in this study have been summarized in Supplementary Table 3. The correlation coefficient (R2) for IVs that was located on the same chromosome have been presented in the Supplementary Table 4. Overall, the F-statistic for the all associations ranged from 21 to 48, indicating that the MR estimate was unlikely to be biased by weak IVs. Statistical power results indicated that our MR analysis was adequate to detect only large effect sizes for most of the ADs outcomes in the FinnGen and MVP biobanks (Supplementary Table 5). One standard deviation (SD) of relative protein, fat, and carbohydrate intake has been reported to be approximately 4.8%, 12.9%, and 16.1% of total energy intake in the UK biobank, respectively20. Of the 81 associations included in the two biobanks, eight were statistically significant in the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method, which were related to seven ADs outcomes (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 6).

A The heatmap shows the associations between relative macronutrient intake and 17 ADs in two biobanks based on IVW method. The gray color indicates that the corresponding ADs were absent in the MVP biobank. ADs autoimmune diseases, IVW inverse variance weighted, MVP Million Veteran Program, OR odds ratio; * indicates PIVW < 0.05. B Significant MR results in FinnGen biobank. C Significant MR results in MVP biobank. MR mendelian randomization, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, MVP Million Veteran Program.

In MR analysis based on the FinnGen biobank, genetically predicted higher relative protein intake (per 4.6% increment) was associated with a lower risk of autoimmune hypothyroidism (odds ratio for IVW [ORIVW] = 0.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.74–0.99, P = 3.7 × 10–2) and a lower risk of psoriasis (ORIVW = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.63–0.97, P = 2.4 × 10–2), respectively (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table 6). We also found that genetically predicted higher relative fat intake (per 12.9% increment) was associated with a lower risk of ulcerative colitis (ORIVW = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.54–0.76, P = 5.2 × 10–7) and a higher risk of Crohn’s disease of large intestine (ORIVW = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.26–2.18, P = 2.8 × 10–4), respectively (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table 6). For relative carbohydrate intake, genetically predicted higher relative intake (per 16.1% increment) was associated with a lower risk of autoimmune hyperthyroidism (ORIVW = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.52–0.97, P = 2.9 × 10–2) (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table 6). Apart from the association between relative carbohydrate intake and autoimmune hyperthyroidism (ORMR-Egger = 6.03), the remaining seven statistically significant associations have the same effect direction as that of the IVW method in other analytical approaches, including MR-RAPS, Weighted median and MR-Egger (Supplementary Table 7).

In MR analysis based on the MVP biobank, we additionally found that higher carbohydrate intake is a risk factor for psoriasis (ORIVW = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.06–1.62, P = 1.2 × 10–2) and type 1 diabetes (ORIVW = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.18–1.77, P = 4.3 × 10–4), yet it serves as a protective factor against sicca symptoms (ORIVW = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.55–0.85, P = 5.5 × 10–4) (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Table 6). The above associations have the same effect direction as IVW method under other analysis methods (Supplementary Table 7).

Sensitivity analysis also confirmed that the aforementioned associations were free from bias due to horizontal pleiotropy (Egger P for intercept >0.05 and MR-PRESSO global test P > 0.05), heterogeneity among IVs (P for Cochran’s Q > 0.05), and reverse causation (P for MR Steiger test <0.05 when the test direction was set to “True”) (Supplementary Table 7). Leave-one-out test on the above associations showed that after removing any one IV, the overall MR results still maintain the same direction and magnitude of effect as before, regardless of whether it was the FinnGen biobank (Supplementary Fig. 1A) or the MVP biobank (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Meta-analysis of MR results from two biobanks

Concerned about the low statistical power resulting in the observed null MR results, we conducted a meta-analysis of MR results from ten shared ADs outcomes across two biobanks to enhance statistical power and evaluate the robustness of significant MR findings initially observed within a single biobank.

Of the 30 associations based on meta-analysis, we observed that a higher relative protein intake was consistently associated with a protective effect on psoriasis (ORmeta = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.71–0.99, P = 4.8 × 10–2, I2 = 13.6%), whereas a higher relative carbohydrate intake was consistently associated with an increased risk of psoriasis (ORmeta = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.02–1.41, P = 2.5 × 10–2, I2 = 30.3%) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 8). Remaining 28 associations yielded null results in the meta-analysis (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 8).

Tier for MR evidence of relative macronutrient intake on ADs

Considering that the disease definition in the MVP biobank and the FinnGen biobank are not entirely consistent, this discrepancy has led to the absence of certain ADs in the MVP biobank. Therefore, we categorized the MR results to systematically represent the robustness of the eight significant associations identified within a single biobank (Table 1). Tier 1 evidence was defined in this study as MR Evidence with the highest level of robustness and confidence, while tier 2 and tier 3 evidence exhibited progressively lower levels of reliability.

Tier 1 evidence included associations of relative protein and carbohydrate intake with risk of psoriasis, which was demonstrated by the fact that the association remained significant in the meta-analysis of two biobanks. Although the statistical power of these associations is less than 80% based on individual biobank (Supplementary Table 5), the weak significant effect was still captured through the conduct of the meta-analysis. Tier 2 evidence comprised associations between relative protein intake and autoimmune hypothyroidism, relative fat intake and Crohn’s disease of large intestine, as well as relative carbohydrate intake and autoimmune hyperthyroidism. Above three associations were significant in one biobank, with all analysis methods showing a consistent effect direction; however, replication analysis was lacking due to data accessibility constraints. The remaining three associations are considered Tier 3 evidence, due to was not significant in either the other biobank or the meta-analysis.

Association of relative macronutrient intake with circulating metabolic biomarkers

Dietary intake are intricately linked to blood metabolite levels21. Therefore, we concentrated on the above established Tier 1 evidence of associations and explored the mediating effects of 233 circulating metabolic biomarkers within a two-step MR framework. In the first step, we systematically investigated the association between relative macronutrient intake and 233 circulating metabolic biomarkers levels.

Of the 699 associations, the F-statistic for the all associations ranged from 22 to 26, indicating that the MR estimate was unlikely to be biased by weak IVs (Supplementary Table 9). After multiple test correction with false discovery rate (FDR) less than 0.05, genetically predicted relative macronutrient intake demonstrates a potential causal relationship with the levels of 46 circulating metabolic biomarkers based on IVW method (Supplementary Table 9). Specifically, this encompasses ten metabolic biomarkers for relative protein intake, 11 for relative fat intake, and 25 for relative carbohydrate intake (Supplementary Table 10). In sensitivity analysis, for the association of genetically predicted relative protein intake with triglycerides to total lipids ratio in large high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the Egger intercept test suggested horizontal pleiotropy (P = 1.9 × 10–2) (Supplementary Table 10). Therefore, this association was not included in the subsequent analysis.

Association of relative macronutrient intake related biomarkers with risk of psoriasis

In the second step, we investigated the associations of 34 circulating metabolic biomarkers related to relative protein and carbohydrate intake on the risk of psoriasis, based on FinnGen biobank. Of the 34 associations, the F-statistic for the all associations ranged from 44 to 201, indicating that the MR estimate was unlikely to be biased by weak IVs (Supplementary Table 11). After multiple test correction (FDR < 0.05), 21 circulating metabolic biomarkers were identified associated with risk of psoriasis based on IVW method (Supplementary Table 11). For the association between glycerol levels and risk of psoriasis, given there were only two IVs for glycerol levels, we excluded this metabolic biomarker in subsequent analyses due to the failure of pleiotropic test. The remaining 20 associations showed no significant heterogeneity, pleiotropy, or reverse causality in sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table 12). Metabolic biomarkers involved included apolipoprotein B, linoleic acid (18:2), remnant cholesterol, six HDL related biomarkers, and 11 very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) related biomarkers.

To mitigate the false positive associations arising from strong correlations among these metabolic biomarkers, we performed a two-sample multivariable MR approach based on Bayesian model averaging (MR-BMA) on HDL and VLDL related biomarkers, respectively. MR-BMA, as an extension of multivariable MR, is capable of identifying true risk factors within a high-dimensional and intercorrelated set of candidate risk factors. For six HDL related biomarkers22. MR-BMA prioritized three key metabolic biomarkers: the mean diameter of HDL particles (PMR-BMA = 8 × 10–4), total lipids in very large HDL (PMR-BMA = 3.8 × 10–2) and concentration of very large HDL particles (PMR-BMA = 2.9 × 10–2) (Supplementary Table 13). For 11 VLDL related biomarkers, MR-BMA also prioritized three key metabolic biomarkers: cholesterol esters in medium VLDL (PMR-BMA = 1.9 × 10–2), phospholipids to total lipids ratio in small VLDL (PMR-BMA = 4.9 × 10–2) and triglycerides in small VLDL (PMR-BMA = 6.7 × 10–3) (Supplementary Table 13).

To estimate the mediating effect subsequently, we re-analyzed the effect size of the above nine metabolites on risk of psoriasis using multivariate MR (MVMR), adjusting for the relative macronutrient intake. MVMR analysis revealed that after adjusting for macronutrient composition, the associations of five metabolites on the risk of psoriasis were still remained, and their effect directions were consistent with those before adjustment (Supplementary Table 14).

Mediating effect of metabolic biomarkers between relative macronutrient intake and risk of psoriasis

Of the five intermediate metabolic biomarkers, three mediated the negative correlation between relative protein intake and risk of psoriasis, with mediation proportions ranging from 7.6 to 9.7%, including apolipoprotein B, remnant cholesterol and phospholipids to total lipids ratio in small VLDL (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 15). Two biomarkers mediated the positive correlation between relative carbohydrate intake and psoriasis, with mediation proportions ranging from 5.4 to 7.5%, including mean diameter of HDL particles and triglycerides in small VLDL (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 15).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic MR study to appraise the association between relative macronutrient intake and ADs risk, based on large-scale genetic data. Eight potential causal associations were identified and further classified into three levels, according to the robustness of MR results. Besides, we employed a two-step Mendelian randomization framework to investigate potential mediating circulating metabolic biomarkers for associations identified at tier 1 evidence.

In tier 1 evidence, we found that higher relative protein and carbohydrate intake were inversely and positively associated with the occurrence of psoriasis, respectively. Psoriasis is a chronic and immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease23. Nowadays, there is still a lack of specific, evidence-based dietary guidelines24. A case report by Castaldo et al. demonstrated that in patients treated with a high-protein diet (1.2 g/kg ideal body weight) during psoriasis recurrence, a significant reduction in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) score (>80%) was observed, and psoriatic joint pain was resolved25. In another study conducted by Castaldo et al., the impact of a 4-week very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD, <500 kcal/day) on psoriasis severity in overweight or obese participants (n = 30) was investigated. The diet provided 10–20 g of carbohydrates (from vegetables, approximately 400–500 g/day), 20–30 g of lipids, and 1.4 g of protein per kilogram of ideal body weight daily. After 4 weeks, there were significant improvements in PASI, itch severity, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)26. A cross-sectional case-control observational study also revealed that patients with psoriasis had significantly higher intakes of total and simple carbohydrates compared to controls, while their protein intake was comparatively lower27. These studies are consistent with our results and provide additional genetic evidence for the role of VLCKD in the development and progression of psoriasis.

Our study further elucidated the mediating role of multiple circulating metabolic biomarkers in the association between relative protein and carbohydrate intake and psoriasis risk. For instance, our study revealed that apolipoprotein B levels serve as a mediator for the inverse association between high dietary protein intake and the risk of psoriasis. The positive association between elevated apolipoprotein B levels and an increased risk of psoriasis has been consistently reported in a meta-analysis involving 2467 participants across 17 studies28. They revealed that psoriasis is significantly associated with elevated serum apolipoprotein B levels compared to healthy controls. At the mechanistic level, apolipoprotein B can trigger the production of TNF-α and IL-6 via the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and NF-κB signaling pathways, thereby promoting inflammatory responses29. Frondelius et al. conducted a cross-sectional study involving 24,984 individuals in Sweden to examine the lifestyle and dietary factors associated with apolipoprotein B concentration. Their findings indicated that a high body mass index (BMI) was one of the most significant determinants of elevated apolipoprotein B levels. For individuals who are overweight or obese, a protein-rich diet can facilitate weight loss by effectively regulating appetite, enhancing satiety, and reducing food cravings30.

Our findings have the following clinical implications. First, we separately determined that higher protein intake (per 4.6% increment) was protective, while higher carbohydrate intake (per 16.1% increment) was a risk factor for psoriasis. This provides genetic evidence and specific relative energy intake references for future clinical studies. Second, our conclusions may be more applicable to specific populations (e.g., obesity). Clinicians can monitor metabolic biomarkers (e.g., apolipoprotein B) in these populations to adjust corresponding dietary components (e.g., relative protein intake), thereby enhancing disease prevention.

For tier 2 and 3 evidence, we also found associations of other relative macronutrients intake with risk of ADs. However, it is important to emphasize that these results should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of independent replication. For instance, our findings found that higher relative fat intake may serve as a protective factor against ulcerative colitis. A prospective study demonstrated that a high intake of dietary long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) could potentially be associated with a reduced risk of ulcerative colitis. Conversely, a high intake of trans unsaturated fats might be linked to an increased risk of ulcerative colitis31. These results underscore the necessity for future research incorporating stratified analyses based on specific types of fats.

This study has several strengths. To begin with, the strength of this study lies in the assessment of isoenergetic diets by adjusting energy intake for macronutrients and food items. The observed change is attributed to the nutrient composition rather than quantity, emphasizing the “relative” rather than “absolute” intake, thereby minimizing confusion regarding energy intake32. Besides, we used genetic variants about dietary macronutrients intake from the largest available GWASs, which allowed us to include as many IVs as possible. We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of invalid instruments, heterogeneity, pleiotropy, and coheritability. In addition, the population ancestry of the datasets we used was all from Europe, therefore, population stratification was not a potential bias in our study. Furthermore, MR analysis takes advantage of the fact that genetic variants are randomly assigned at meiosis and fertilization and are established before disease develops, thereby minimizing the problems of confounding and reverse causation33. Finally, in order to enhance the statistical power and ensure the robustness of our results, we conducted replication analysis and additional meta-analysis.

This study also has several limitations. First, we did not stratify the analysis by influencing factors due to the unavailability of individual-level data. Second, the genetic variation explains only a small fraction of the total variation for relative macronutrient intake, thus the study was not sufficient to detect very small effects. Third, our study did not distinguish the sources of macronutrients, such as plant protein and animal protein. Different sources of nutrients may have different effects on the occurrence of ADs34, which needs to be further explored in future population studies. Fourth, genetic variants reflect lifelong exposure rather than short-term therapeutic interventions. Therefore, final confirmation of causal effects may need to be validated by randomized controlled trials of preventive interventions. Fifth, despite our thorough sensitivity analysis of the MR results, we cannot entirely rule out potential violations of the assumptions of independence and exclusion restrictions, especially concerning pleiotropy. Sixth, given the inherent complexity of autoimmune diseases, the disease definitions based on ICD codes from the biobank in this study may not be entirely accurate. Finally, the study primarily focused on European populations, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to some extent.

In summary, we included a broad range of ADs outcomes to determine the causal effect of relative macronutrient intake. Our findings provided three causal level from eight associations, as well as nine candidate circulating metabolic mediators in tier 1 evidence. Nevertheless, the results warrant further validation through randomized controlled trials.

Methods

Data sources

GWASs for relative macronutrients intake, including protein, carbohydrate and fat, were obtained from Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (SSGAC)20. This consortium included a sample size of 268,922 European-ancestry individuals. Using self-report questionnaires containing ≥70 food items, relative contributions of fat, protein and carbohydrate to total energy intake were calculated using a method that adjusts for observed non-linear relationships.

Based on the definition of ADs provided in previous research5,35, we retrieved GWAS summary data for 17 types of ADs from the FinnGen biobank36 and the MVP biobank37. The FinnGen biobank’s data, released in its 12th round, encompassed all 17 types of ADs investigated in this study, with a total of 198,548 ADs cases. Meanwhile, the MVP biobank included 10 overlapping types of ADs, matching those in the FinnGen biobank, with a total of 93,795 ADs cases. ICD-9 or ICD-10 was used for the endpoint definition of the above-mentioned ADs diseases.

Genetic variants for 233 circulating metabolic traits were downloaded from a meta-analysis from 33 cohorts quantified by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in up to 136,016 participants (approximately 88% European-ancestry population)38. The meta-analysis provided comprehensive data on lipoprotein subclasses, including their lipid concentrations and compositions, as well as measurements of apoAI and apoB levels, cholesterol and triglyceride levels, albumin concentration, various fatty acids, and low-molecular-weight metabolites.

Selection of the genetic IVs

For relative macronutrient intake, given the limited number of instrumental variables (IVs) reaching genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10–8), we set the significance threshold at 5 × 10–6 based on previous study on relative macronutrient intake39. For circulating metabolic biomarker, we still choose 5 × 10–8 as the significance threshold. We then excluded single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with the minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.01 and pruned SNPs by a cut-off of R2 < 0.001 and window size of 10,000 kb, utilizing the European samples data from the 1000 Genomes project, which included 503 European samples, as the reference panel40. Only the SNPs with the lowest Pvalue were retained. To check the actual linkage disequilibrium status of IVs after pruning, we used “LDmatrix tool” under the “European” parameter to calculate specific R2 values for those IVs located on the same chromosome (https://ldlink.nih.gov/?tab=ldmatrix). Considering the complexity of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region, we further examined whether the position of IVs overlapped with MHC and further excluded those IVs that overlapped. We obtained the MHC regions of GRCh37 assembly (chr6:28,477,797-33,448,354) and GRCh38 assembly (chr6:28,510,120-33,480,577) from the Genome Reference Consortium41.

In order to better control the bias of confounding factors on the MR results, we investigated all IVs of relative macronutrient intake in the GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/)42 to assess any previous associations (P < 5 × 10–6) with plausible confounders, including dietary factors other than macronutrient intake, smoking, alcohol consumption, disease status and physical activity6,43,44,45.

If the screened SNPs were not present in the outcome, we excluded the corresponding SNPs. Before MR analysis, two additional statistical methods were applied to select IVs. We employed Steiger filtering to eliminate genetic variants that account for a greater proportion of variance in the outcome compared to the exposure, thereby mitigating potential reverse causation46. We further introduced RadialMR method47, which can identify outlier pleiotropic SNPs to reduce the risk of pleiotropy.

Testing instrument strength and statistical power

The F statistic is used to gauge the strength of IVs through the formula F = Beta2/SE2, where Beta denotes the estimated genetic effect on exposure, SE represents standard error of Beta48. F statistic of ≥10 indicates the absence of significant weak instrumental bias49. R2 (proportion of variance in the phenotype explained by the IVs) was also calculated for subsequently power assessment, using the approximation R2 = 2×EAF× (1 − EAF)×Beta2, where EAF is the effect allele frequency50.

We calculated the statistical power of MR analysis using an online calculator tool (https://shiny.cnsgenomics.com/mRnd/)51. This tool utilizes asymptotic theory to estimate power values for detecting causal effects derived from IVs. We conducted power calculations at a significance level of 0.05, by inputting parameters such as the R2 of IVs, the proportion of outcome GWAS cases, and the OR obtained through MR analyses using the IVW method. We set the power to 80% and reported the minimum OR for each association.

Univariable MR and sensitivity analysis

Two-sample MR was performed to evaluate the causal associations between exposures and outcomes (R package TwoSampleMR, version 0.5.6). IVW under a multiplicative random-effects model were used for main analysis methods52. OR or β value with 95% CI were calculated to identify causal effects between exposures and outcomes.

Given that a low statistical power on the association between relative macronutrient intake and risk of autoimmune diseases, we did not directly apply multiple testing corrections to avoid losing valuable results. We adopted another common research design53, that is, conducting MR analyses on diseases from independent large-scale biobanks respectively, and then performing a meta-analysis to obtain the final results. This method can enhance the statistical power of MR analysis while taking heterogeneity into account. Meta-analysis of IVW results from different biobanks was further performed using “meta, version 7.0-0” package. The heterogeneity of the IVW results was evaluated using the I² statistic. A fixed-effect model (common effect model) was applied when I² < 50%, while a random-effects model was selected if I² ≥ 50%. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant54.

A series of sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness and reliability of the results. The Cochran’s Q statistic was calculated to assess heterogeneity among IVs55. MR-Egger regression with intercept terms was utilized to assess the potential presence of horizontal pleiotropy56. In addition to the MR-Egger method, MR-PRESSO global test was utilized as an additional tool for pleiotropy assessment with the “MRPRESSO (version 1.0)” package57. MR-RAPS and weighted median were also conducted to evaluate the robustness of our calculated results. MR-RAPS method could offer robust inferences for MR analysis with multiple weak instruments58. Weighted median method could allow up to 50% of the information from variants to violate the MR hypothesis in the presence of horizontal pleiotropy59. Besides, MR Steiger test was performed to estimate the potential reverse causal impact46. We also performed leave-one-out test to detect the influence of a single IV on the overall MR estimate50.

Tier for MR evidence

In order to compare the robustness of the MR results of relative macronutrients intake with risk of ADs, we stratified the MR results as follows: Tier 1 evidence indicates that the association was significant in the meta-analysis of two biobanks (Pmeta <0.05). Tier 2 evidence indicates that the association was significant in only one biobank based on IVW method (PIVW <0.05), with all analysis methods showing a consistent effect direction; however, replication analysis was lacking due to data accessibility constraints. Tier 3 evidence indicates that the association was significant in only one biobank based on IVW method and was not significant in either the other biobank or the meta-analysis. All evidence was required to satisfy no significant heterogeneity (P for Cochran’s Q testå 0.05), pleiotropy (P for Egger intercept test and MR-PRESSO global testå 0.05), or reverse causality (P for MR Steiger test <0.05 when the causal direction was set “True”). Although the study adopted the MR evidence stratification design, we still conducted multiple test corrections using the FDR method based on the Benjamini-Hochberg approach, with a threshold of 0.05. This can provide a reference for the false positive risk of MR evidence from Tier 2 and Tier 3.

Mediation analysis

Two-step MR was performed to assess whether a mediator had a mediating effect between the relative macronutrient intake and risk of ADs60. In the first step, genetic instruments for relative macronutrient intake were used to estimate the causal effect of the exposure on the 233 circulating metabolic biomarkers, using univariable MR (UVMR). The second step is to initially screen the significant associations between the metabolites identified in the first step and risk of ADs using UVMR. Subsequently, the causal effect was further estimated using MVMR after adjusting for the composition of macronutrient. We applied the MV-IVW as the main analysis in MVMR61. FDR based on Benjamini-Hochberg method less than 0.05 was used for multiple test corrected threshold. Where there was evidence that relative macronutrient intake influenced the metabolic mediator, which in turn influenced the risk of ADs, “product of coefficients” method62 was utilized to assess the indirect effect. The standard errors for the indirect effects were obtained through the utilization of the delta method63. MVMR was conducted using R package “MVMR (version 0.4)” and “MendelianRandomization (version 0.9.0)”.

MR-BMA analysis

MR-BMA analysis is an extension of multivariate MR, which can determine which of a set of exposures with common genetic predictors were causal drivers of risk of outcome22. In the MR-BMA analysis, for each exposure, an MIP value is calculated that represents the posterior probability that the exposure factor x appears in the true causal model for a given z iteration. The method also estimates MACE, which represents the weighted average direct causal effect of exposure on risk across all candidate models. It is important to note that MACE should not be interpreted in absolute terms. Due to the contraction applied in variable selection, it will be biased towards zero. But this metric can be used to understand the direction and magnitude of the impact relative to other exposures included in the model.

We combined the IVs for exposures, and further clumped by linkage disequilibrium (R2 < 0.001 within a window of 10,000 kb) to ensure that the IVs were independent. We set z to 10,000, the prior probability to 0.1, and prior variance (σ2) to 0.25 in the analysis64. The analysis was conducted using the “mrbma” package (version 0.1.0).

Data availability

The data utilized in this study were acquired from publicly accessible databases. The code implemented in this research will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Marrack, P., Kappler, J. & Kotzin, B. L. Autoimmune disease: Why and where it occurs. Nat. Med. 7, 899–905 (2001).

Conrad, N. et al. Autoimmune diseases and cardiovascular risk: A population-based study on 19 autoimmune diseases and 12 cardiovascular diseases in 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet 400, 733–743 (2022).

He, H. et al. Association of maternal autoimmune diseases with risk of mental disorders in offspring in Denmark. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e227503 (2022).

Hemminki, K., Liu, X., Ji, J., Sundquist, J. & Sundquist, K. Effect of autoimmune diseases on risk and survival in histology-specific lung cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 40, 1489–1495 (2012).

Conrad, N. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: A population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet 401, 1878–1890 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Mendelian randomization as a tool to gain insights into the mosaic causes of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 21, 103210 (2022).

Al Nabhani, Z. et al. Excess calorie intake early in life increases susceptibility to colitis in adulthood. Nat. Metab. 1, 1101–1109 (2019).

Bai, M. et al. Intermittent caloric restriction with a modified fasting-mimicking diet ameliorates autoimmunity and promotes recovery in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J. Nutr. Biochem 87, 108493 (2021).

Eckel-Mahan, K. Energy intake at the intersection of the clock and ageing. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 19, 72–73 (2023).

Lambert, C. P., Frank, L. L. & Evans, W. J. Macronutrient considerations for the sport of bodybuilding. Sports Med 34, 317–327 (2004).

Zielińska, M. & Michońska, I. Macronutrients, vitamins and minerals in the diet of multiple sclerosis patients. Adv. Psychiatry Neurol. 31, 128–137 (2022).

Castro-Webb, N. et al. Association of macronutrients and dietary patterns with risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in the Black Women’s Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 114, 1486–1494 (2021).

Shao, S. et al. Dietary high-fat lard intake induces thyroid dysfunction and abnormal morphology in rats. Acta Pharm. Sin. 35, 1411–1420 (2014).

Mifflin, M. et al. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51, 241–247 (1990).

Shah, R. V. et al. Dietary metabolic signatures and cardiometabolic risk. Eur. Heart J. 44, 557–569 (2023).

Emdin, C. A., Khera, A. V. & Kathiresan, S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA 318, 1925–1926 (2017).

Angrist, J. D., Imbens, G. W. & Rubin, D. B. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 444–455 (1996).

Didelez, V. & Sheehan, N. Mendelian randomization as an instrumental variable approach to causal inference. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 16, 309–330 (2007).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: The STROBE-MR statement. JAMA 326, 1614–1621 (2021).

Meddens, S. F. W. et al. Genomic analysis of diet composition finds novel loci and associations with health and lifestyle. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 2056–2069 (2021).

Noerman, S. & Landberg, R. Blood metabolite profiles linking dietary patterns with health—Toward precision nutrition. J. Intern. Med. 293, 408–432 (2023).

Zuber, V., Colijn, J. M., Klaver, C. & Burgess, S. Selecting likely causal risk factors from high-throughput experiments using multivariable Mendelian randomization. Nat. Commun. 11, 29 (2020).

Griffiths, C. E. M., Armstrong, A. W., Gudjonsson, J. E. & Barker, J. N. W. N. Psoriasis. Lancet 397, 1301–1315 (2021).

Hawkins, P., Earl, K., Tektonidis, T. G. & Fallaize, R. The role of diet in the management of psoriasis: a scoping review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 37, 296–330 (2024).

Castaldo, G., Galdo, G., Rotondi Aufiero, F. & Cereda, E. Very low-calorie ketogenic diet may allow restoring response to systemic therapy in relapsing plaque psoriasis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 10, 348–352 (2016).

Castaldo, G. et al. Effect of very-low-calorie ketogenic diet on psoriasis patients: A nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomic study. J. Proteome Res. 20, 1509–1521 (2021).

Barrea, L. et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J. Transl. Med. 13, 1–10 (2015).

Wang, F. et al. Association between psoriasis and serum apolipoprotein A1 and B: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 9, e21168 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. The difference of lipid profiles between psoriasis with arthritis and psoriasis without arthritis and sex-specific downregulation of methotrexate on the apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A-1 ratio. Arthritis Res Ther. 24, 1–9 (2022).

Leidy, H. J., Ortinau, L. C., Douglas, S. M. & Hoertel, H. A. Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese, “breakfast-skipping,” late-adolescent girls123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97, 677–688 (2013).

Ananthakrishnan, A. N. et al. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut 63, 776–784 (2014).

Willett, W., Howe, G. & Kushi, L. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65, 1220S–1228S (1997).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Smith, G. D. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 362, k601 (2018).

Manzel, A. et al. Role of “Western Diet” in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 14, 404 (2013).

Zhong, H. et al. Causal relationships between mood instability and autoimmune diseases: A mendelian randomization analysis. Autoimmun. Rev. 22, 103214 (2023).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518 (2023).

Verma, A. et al. Diversity and scale: Genetic architecture of 2068 traits in the VA Million Veteran Program. Science 385, eadj1182 (2024).

Karjalainen, M. K. et al. Genome-wide characterization of circulating metabolic biomarkers. Nature 628, 130–138 (2024).

Freuer, D., Meisinger, C. & Linseisen, J. Causal relationship between dietary macronutrient composition and anthropometric measures: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Clin. Nutr. 40, 4120–4131 (2021).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet 81, 559–575 (2007).

Schneider, V. A. et al. Evaluation of GRCh38 and de novo haploid genome assemblies demonstrates the enduring quality of the reference assembly. Genome Res 27, 849–864 (2017).

Cerezo, M. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog: Standards for reusability, sustainability and diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D998–D1005 (2025).

Dallongeville, J., Marécaux, N., Fruchart, J.-C. & Amouyel, P. Cigarette smoking is associated with unhealthy patterns of nutrient intake: A meta-analysis12. J. Nutr. 128, 1450–1457 (1998).

Joseph, P. V. et al. Relationships among alcohol drinking patterns, macronutrient composition, and caloric intake: National health and nutrition examination survey 2017–2018. Alcohol Alcohol 57, 559–565 (2022).

Hahn, H., Friedel, M., Niessner, C., Zipfel, S. & Mack, I. Impact of physical activity on caloric and macronutrient intake in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 21, 1–32 (2024).

Hemani, G., Tilling, K. & Smith, G. D. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. Plos Genet 13, e1007081 (2017).

Bowden, J. et al. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization via the Radial plot and Radial regression. Int J. Epidemiol. 47, 1264–1278 (2018).

Richardson, T. G. et al. A transcriptome-wide Mendelian randomization study to uncover tissue-dependent regulatory mechanisms across the human phenome. Nat. Commun. 11, 185 (2020).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 21, 223–242 (2012).

Yao, S. et al. Bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis identifies causal associations between relative carbohydrate intake and depression. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1569–1576 (2022).

Brion, M.-J. A., Shakhbazov, K. & Visscher, P. M. Calculating statistical power in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J. Epidemiol. 42, 1497–1501 (2013).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 37, 658–665 (2013).

Fu, Y. et al. Circulating vitamin C concentration and risk of cancers: A Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med 19, 171 (2021).

Wang, B., Chen, S., Liu, X. & Zhang, L. Effectiveness of tuberculosis preventive treatment in patients with rheumatic diseases: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 82, 103177 (2025).

Bowden, J. et al. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat. Med. 36, 1783–1802 (2017).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525 (2015).

Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet 50, 693–698 (2018).

Zhao, Q., Wang, J., Hemani, G., Bowden, J. & Small, D. S. Statistical inference in two-sample summary-data Mendelian randomization using robust adjusted profile score. Ann. Stat. 48, 1742–1769 (2020).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 40, 304–314 (2016).

Carter, A. R. et al. Mendelian randomisation for mediation analysis: current methods and challenges for implementation. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36, 465–478 (2021).

Grant, A. J. & Burgess, S. Pleiotropy robust methods for multivariable Mendelian randomization. Stat. Med. 40, 5813–5830 (2021).

VanderWeele, T. J. Mediation analysis: A practitioner’s guide. Annu Rev. Public Health 37, 17–32 (2016).

Carter, A. R. et al. Understanding the consequences of education inequality on cardiovascular disease: mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 365, l1855 (2019).

Lord, J. et al. Mendelian randomization identifies blood metabolites previously linked to midlife cognition as causal candidates in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2009808118 (2021).

Acknowledgements

All authors acknowledge the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium, the participants and investigators of the FinnGen study, Million Veteran Program and cited genome-wide association studies for sharing their GWAS data. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 82473628 to Y.J.S.), Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82200632), Industry-University-Research Innovation Fund for Chinese Universities—Infection and Control Project (2024GR024), Basic Scientific Research Funds of Department of Education of Zhejiang Province (KYZD202201) and Hangzhou Medical College Scientific and Technological Innovation Guidance Fund (2024CXZD02) to D.Z.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z.C. and Y.J.S. conceived and supervised research. S.Z.Z., G.Q.N, K.L.L and D.Q.M. participated in the data collection. S.Z.Z. and G.Q.N. performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. Y.J.S. assisted with proofreading the manuscript. D.Z.C. and Y.J.S. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors discussed the results and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, S., Na, G., Liang, K. et al. Systematic genetic investigation on relative macronutrient intake, circulating metabolic biomarkers and the risk of autoimmune diseases. npj Sci Food 9, 205 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00565-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00565-x