Abstract

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a prevalent nutritional disorder primarily treated with inorganic iron supplements. However, these interventions are often limited by poor bioavailability and gastrointestinal side effects. Food-derived protein hydrolysates have emerged as promising dietary strategies to enhance iron absorption and mitigate adverse effects. This study evaluated the efficacy of dietary supplementation with Donkey-hide gelatin hydrolysates (DH) in alleviating IDA in a rat model. DH-Fe exhibited superior binding affinity and stability, retaining more soluble iron fraction under diverse conditions, confirming its role as a functional dietary iron carrier. In vivo, DH markedly enhanced hematopoiesis and iron homeostasis, elevating hemoglobin by 44% and normalizing serum ferritin (25.34 ng/mL). DH also enhanced antioxidant defenses, increasing SOD and hydroxyproline levels to 111% and 168% of the reference groups, respectively. Moreover, DH ameliorated IDA-induced liver injury and gut microbiota dysbiosis by promoting beneficial bacteria (e.g., Ruminococcus) and suppressing pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Escherichia-Shigella). Overall, these findings indicate that DH improves hematopoiesis and modulates gut microbiota composition, supporting its potential as a next-generation dietary iron supplement for IDA management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is among the most common diet-related nutrient deficiencies worldwide and remains a major public health challenge, characterized by fatigue, pallor, and reduced hemoglobin levels1. The Global Burden of Disease Study (2017) estimated that over 1.1 billion people worldwide are affected by iron deficiency2. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia as hemoglobin <130 g/L in men and <120 g/L in women1. IDA mainly results from inadequate dietary iron intake and impaired intestinal absorption, underscoring the urgent need for improved dietary strategies and more effective iron supplementation3.

Conventional inorganic iron supplements have significant limitations, including poor bioavailability that often necessitates high doses (50–200 mg/day) to achieve therapeutic effects. However, such high doses can promote free radical formation, induce oxidative stress and disrupt metabolic homeostasis in vivo, thereby limiting their long-term management4. Intestinal iron overload may also cause gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., nausea, constipation, dyspepsia) and disturb gut microbiota composition and diversity5. To address these limitations, food-derived bioactive molecules have attracted considerable interest as alternative, natural iron carriers. For example, polysaccharides6,7, whey protein8, and casein phosphopeptides9 have been shown to enhance iron absorption and metabolism in vivo. Previous studies have mainly focused on biomolecule-iron chelates, which require additional chelation steps that can increase costs and reduce processing efficiency. Consequently, it remains uncertain whether biomolecules themselves (without prior chelation) can stably bind and transport iron under food-related processing or physiological conditions. Therefore, we attempted to directly mix biomolecules with iron (without additional chelation procedures) to evaluate whether they could spontaneously form stable, food-grade complexes and enhance iron absorption in vivo. Previous research has demonstrated that peptide-iron chelates can improve iron bioavailability through peptide transport pathways while also providing additional nutritional benefits. For example, hemoglobin hydrolysates (HH) have been reported to enhance iron absorption in mice through the spontaneous formation of iron complexes10. Donkey-hide gelatin (E-jiao), a traditional Chinese food-derived gelatin obtained from donkey skin, is rich in collagen and amino acids and has been used in China for over 2000 years for its hematopoietic and restorative properties. Extensive studies have shown that E-jiao exhibits multiple functional properties, including antioxidant, immune-modulating, and anti-anemia effects11,12. Notably, its hydrolysates (DH) further enhance hematopoiesis, likely through the release of bioactive peptides13. Unlike previously studied peptides such as casein phosphopeptides, DH offers a unique combination of traditional medicinal background11, collagen-derived bioactive sequences12, and potential dual effects on both iron metabolism and host physiology. IDA is also closely associated with intestinal microbiota dysbiosis, typically characterized by an increased relative abundance of Proteobacteria14. Moreover, dietary supplementation with E-jiao has been reported to alleviate intestinal inflammation and restore gut microbiota homeostasis13, suggesting that its hydrolysates may provide dual benefits by simultaneously promoting iron metabolism and improving gut health.

In this study, the hydrolysates were directly mixed with FeSO4 in aqueous solution at room temperature without additional treatments to obtain DH-Fe and HH-Fe complex solutions. The pH stability, thermal stability, and iron-binding capacity of DH-Fe and HH-Fe were systematically evaluated. An IDA rat model was established using a low-iron diet. The effects of DH on iron absorption and IDA management were evaluated without prior chelation, directly addressing the knowledge gap of whether hydrolysates themselves can act as efficient iron carriers in vivo. In addition, gut microbiota diversity was analyzed to explore potential diet-microbiota interactions underlying hematopoietic regulation. Collectively, these findings highlight DH as a promising next-generation food-derived iron supplement. Its distinctive advantages arise from its simplified preparation without prior chelation, its collagen-derived bioactive peptides that support hematopoiesis and antioxidant defense, and its dual action on both iron metabolism and gut microbiota balance. Unlike conventional carriers that focus primarily on iron delivery, DH integrates nutritional efficacy with microbiota regulation, offering a more comprehensive approach to IDA management.

Results

Relative molecular weight distribution of HH and DH

The relative molecular weight distribution of the hydrolysates is summarized in Table 1. DH contained 79.64% of peptides <3000 Da, 10.69% in the 3000–5000 Da range, 8.37% in the 5000–10,000 Da range, and 0.26% >10,000 Da. In contrast, HH was dominated by peptides <3000 Da (95.17%), with minor proportions in higher molecular weight ranges. Despite having fewer small peptides than HH, DH still exhibited strong iron-binding capacity and hematopoietic efficacy.

pH stability of DH-Fe

The results revealed a significant decrease in the soluble iron fraction content of the HH-Fe as the pH increased (p < 0.05). At pH 1.0, the HH-Fe retained 200.35 mg/L of soluble iron fraction; however, most of the iron precipitated under near-neutral and alkaline conditions (Fig. 1A). In contrast, DH-Fe exhibited a high soluble iron fraction under acidic conditions, with 387.45, 390.99, and 338.65 mg/L at pH 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0, respectively. Moreover, DH-Fe maintained 209.01 and 180.21 mg/L of soluble iron fraction even at pH 7.0 and 8.0. These findings suggest that DH has a stronger iron-binding capacity and superior pH stability compared to HH, supporting its potential as a stable dietary iron carrier under varying gastrointestinal conditions.

Thermal stability of DH-Fe

The DH-Fe showed excellent thermal stability, with soluble iron fraction levels remaining stable (~1007.02 mg/L) across a temperature range of 20 °C to 100 °C (Fig. 1B, p > 0.05). In contrast, the HH-Fe exhibited a gradual reduction in iron fraction solubility, decreasing from 595.39 mg/L at 20 °C to 487.59 mg/L at 100 °C. These results indicate that DH-Fe is more resistant to heat-induced loss of solubility than HH-Fe, suggesting better stability during food processing.

The DSC profiles revealed distinct thermal behaviors between HH-Fe and DH-Fe (Fig. S1). The magnitude of the enthalpy, ΔH, reflects the extent of protein denaturation and the thermal sensitivity of proteins15. For different samples, the larger ΔH, the smaller degree of protein denaturation prior to reaching the denaturation temperature, indicating better thermal stability16. HH-Fe showed a single endothermic transition at 118.96 °C with an enthalpy of 267.02 J/g, indicating a relatively uniform and less stable structure. In contrast, DH-Fe exhibited a bimodal profile with a low-temperature peak at ~84 °C and a high-temperature peak at 129.74 °C, accompanied by a markedly higher enthalpy (476.49 J/g). The larger ΔH observed in DH-Fe suggests that more energy was required to disrupt its peptide-iron interactions, reflecting enhanced thermal stability. The observed differences in denaturation temperatures may result from the denaturation of distinct peptide fractions17. The dual endothermic peaks of DH-Fe suggest distinct peptide-iron interactions with different stability levels. Together with the shift of the high-temperature transition above 120 °C and the significantly larger enthalpy, these findings confirm that DH-Fe possesses superior structural resilience and thermal stability relative to HH-Fe.

Binding stability of DH-Fe

At hydrolysate-to-iron ratios of 100:1 and 50:1, the soluble iron fraction content in the HH-Fe remained at relatively low levels (Fig. 1C). As the proportion of iron increased, the DH-Fe showed a gradual increase in soluble iron fraction content, reaching 101.42, 179.43, 1982.27, and 9639.01 mg/L, respectively. In comparison, the DH-Fe consistently exhibited higher soluble iron fraction levels than the HH-Fe across all tested hydrolysate-to-iron ratios. These findings highlight the strong and stable iron-binding capacity of DH across a broad range of iron concentrations, clearly surpassing that of HH. Collectively, these results demonstrate that DH possesses superior potential as an effective dietary iron carrier compared with HH, providing a more promising strategy for dietary iron supplementation.

DH improve physiological characteristics

Anemia is typically characterized by fatigue, pallor, and reduced hemoglobin levels1. Before the experiment, no significant differences in physiological characteristics or HGB levels were detected among the groups (p > 0.05). After IDA induction, the rats exhibited pallor and showed reduced weight gain (Fig. 2B). HGB levels in the MOD group (87.05 g/L) were significantly below the diagnostic threshold for IDA (Fig. 3A, p < 0.05). After 6 weeks of intervention, body weights in the HH (586.66 g), DH (596.00 g), and HDH (582.83 g) groups recovered to levels similar to the CON group (609.66 g) (Fig. 2C). Regarding weight gain rates, no significant difference was observed between the FeSO4 and IDA groups (p > 0.05). However, weight gain rates in the HH (118.91%), DH (121.44%), and HDH (116.31%) groups were significantly higher than in the FeSO4 group (p < 0.05). Furthermore, HH, DH, and HDH interventions effectively alleviated IDA-induced pallor, as indicated by restored redness in the rats’ mouths and ears, as well as smoother and tidier fur (Fig. 2E). DH effectively alleviated pallor and promoted weight gain in IDA rats.

A Schematic diagram of animal experiments; B Comparison of body weights of rats before and after modeling; C Comparison of body weight of rats before and after intervention; D Body weight growth rate of rats; E Observations in rats. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05).

DH enhance hematopoiesis

Hematological indices, including HGB, RBC, HCT, MCV, MCH, MCHC, and RDW, are key indicators of an organism’s overall health status (Fig. 3A-G). Consistent with previous studies, IDA caused significant changes in hematological indices in rats, particularly a marked reduction in HGB and MCV18. Various interventions produced different levels of improvement in these indices. The DH group showed the greatest improvement in HGB (126 g/L), MCV (45.92 fL), and RDW (17.37%) (p < 0.05), approaching the levels of the CON group (Fig. 3A, D and G). RBV, expressed relative to the FeSO4 group (set as 100%), was significantly elevated to 132.93%, 169.65%, and 158.99% in the HH, DH, and HDH groups, respectively (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3H). Similarly, HGB regeneration efficiency (HGBRE) reached 8.97% in HH, 11.45% in DH, and 10.73% in HDH, all of which exceeded the FeSO4 group (6.75%) (Fig. 3I). Overall, DH markedly enhanced the efficacy of iron supplementation: the DH group achieved the highest RBV (169.65%) and the greatest HGBRE (11.45%), both significantly greater than those in the FeSO4 group (p < 0.05).

Effect of DH on iron homeostasis in IDA rats

Biochemical indicators are essential for assessing iron metabolism, particularly in the context of IDA. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, B, and E, the SI (14.60 μmol/L), SF (18.36 ng/mL), and TS (9.95%) were significantly decreased in the IDA group (p < 0.05). In contrast, SI, SF, and TS levels significantly increased in the DH group, reaching 25.46 μmol/L, 25.34 ng/mL, and 25.49%, respectively (p < 0.05). These values corresponded to 138.75%, 127.66%, and 186.74% of those in the FeSO4 group, indicating enhanced efficacy (p < 0.05). TIBC was significantly elevated in the IDA group (149.25 μmol/L) compared to the CON group (p < 0.05). Conversely, the DH group maintained a TIBC level of 109.07 μmol/L, comparable to the CON group, suggesting effective normalization (Fig. 4C). These findings demonstrate that DH plays a vital role in restoring iron homeostasis in IDA rats.

DH enhances antioxidant activity and hydroxyproline levels

Oral FeSO4 administration is known to induce oxidative stress and promote lipid peroxidation in cell membranes, resulting in cellular damage19. This study investigated whether protein hydrolysate supplementation could mitigate these adverse effects. To evaluate the antioxidant effects of protein hydrolysates, serum SOD activity and MDA concentration were assessed as oxidative stress markers. Serum SOD activity was significantly reduced in the IDA group (148.37 U/mL) compared to the CON group (155.65 U/mL) (Fig. 4F, p < 0.05), suggesting oxidative damage. SOD activity further decreased in the FeSO4 group (145.40 U/mL), suggesting a possible pro-oxidative effect and supporting the hypothesis that FeSO4 promotes free radical formation in vivo4. Intervention with protein hydrolysates improved SOD activity to varying extents, with the DH group showing the most pronounced effect. The DH group exhibited the highest SOD activity (161.77 U/mL), which was not significantly different from the CON group (p > 0.05). In terms of MDA levels (Fig. 4G), both the IDA (9.63 nmol/mL) and the FeSO4 group (8.77 nmol/mL) showed significantly higher levels than the CON group (p < 0.05). In contrast, the HH (8.17 nmol/mL), DH (7.92 nmol/mL), and HDH (7.67 nmol/mL) groups did not differ significantly from the CON group (p > 0.05). HYP, a major component of collagen, serves as an indirect marker of collagen metabolism in vivo. HYP levels were significantly reduced in the IDA group (4.05 μg/mL) compared to the CON group (p < 0.05). However, HYP levels were significantly elevated in the DH (11.53 μg/mL) and HDH (8.97 μg/mL) groups, indicating that DH enhances collagen metabolism (Fig. 4H). Overall, these results suggest that DH enhances antioxidant capacity and stimulates collagen metabolism. These effects may contribute to tissue repair and support overall health in the management of IDA.

DH improves liver damage caused by IDA

Iron homeostasis is vital for tissue function, with the liver serving as the primary site for iron storage and metabolism19. Consequently, liver histomorphology was a key focus in assessing the impact of IDA and the potential protective effects of dietary interventions. H&E staining was employed to evaluate histological changes and assess the protective effects of protein hydrolysate interventions against IDA-induced liver damage20. In the CON group, hepatic lobules and sinusoids were clearly defined, and hepatocytes appeared densely packed and uniformly arranged, indicating normal liver architecture (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the IDA group exhibited pronounced pathological changes, including vacuolated hepatic cells with indistinct borders and severely disorganized sinusoids. In the FeSO4 group, hepatic sinusoids remained disrupted and hepatic cords poorly defined, showing only modest improvement relative to the IDA group. In contrast, the HH, DH, and HDH groups exhibited largely intact liver structures without noticeable lesions, demonstrating significant recovery compared to both the IDA and FeSO4 groups. These findings suggest that protein hydrolysate interventions, particularly DH, effectively alleviate IDA-induced liver damage, highlighting their potential as functional dietary components for liver protection. H&E staining was also conducted on the small intestine and skin tissues. However, the findings were not sufficiently distinct to support a clear conclusion. To avoid misleading readers, this part has not been included in the manuscript.

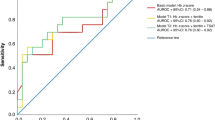

DH improves the intestinal microenvironment

The regulatory effects of DH on gut microbiota were assessed via 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples collected after six weeks of intervention, yielding sufficient coverage to evaluate microbial diversity and community composition. Alpha diversity indices, including Ace, Chao, Sobs, Shannon, and Simpson, showed no significant differences among the six groups (Table 2), indicating similar overall species richness and community diversity. Although overall diversity was unaffected, iron deficiency may selectively alter specific microbial taxa, such as promoting potential pathogenic bacteria, which can trigger inflammation and further impact host iron metabolism21. Thus, lack of significant alpha diversity differences does not preclude biologically relevant compositional changes. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed distinct clustering between the IDA and CON groups (Fig. 5B), suggesting that iron deficiency substantially altered the overall gut microbial community richness. Notably, the intervention groups clustered between the IDA and CON groups, suggesting that protein hydrolysate treatments partially restored microbial composition. A total of 14 phyla were identified (Fig. 5C). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidota ratio, highest in the CON group, was substantially reduced in the IDA and FeSO4 groups, consistent with previous reports that iron deficiency disrupts gut microbiota composition14. Intervention with HH, DH, and HDH groups significantly increased the Firmicutes/Bacteroidota ratio, with DH and HDH groups reaching levels comparable to the CON group. At the genus level (Fig. 5D), the IDA and FeSO4 groups showed elevated abundances of pro-inflammatory bacteria, such as Escherichia-Shigella and Bacteroides22, which were markedly reduced in the DH and HDH groups. Conversely, DH and HDH groups exhibited higher levels of beneficial bacteria, including unclassified_f__Lachnospiraceae, norank_o__Clostridia_UCG-014, Ruminococcus, Romboutsia, Candidatus_Saccharimonas, and Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1. LEfSe analysis identified key microbial biomarkers across groups (LDA > 3.0, Fig. 5F). The IDA group was enriched with UBA1819 and Bilophila, while the CON group was dominated by Clostridia, Firmicutes, and Christensenella. In the DH group, Saccharimonadia, Saccharimonadales, Patescibacteria, and related taxa were predominant. A community heatmap (Fig. 6B) showed species composition and relative abundance across groups. In the DH group, Lachnoclostridium and Bilophila abundances correlated positively with the CON group and negatively with the IDA group, suggesting that DH treatment helps restore gut microbial balance and may facilitate improved iron absorption and intestinal health.

A Intestinal iron content; B Community heatmap; C Correlation analysis of hematological indicators with antioxidant capacity and HYP levels. D Correlation analysis between intestinal microbiota and other indicators. In the matrix, the color gradient of each square represents the strength of the correlation coefficient. Red indicates a positive correlation, while blue indicates a negative correlation. Statistical significance is denoted by an asterisk (*p < 0.05).

Discussion

The relative molecular weight distribution of DH is summarized in Table 1. DH was dominated by peptides <3000 Da (79.64%), with moderate proportions of 3000-5000 Da (10.69%) and 5000-10,000 Da (8.37%) fractions, while peptides >10,000 Da were negligible (0.26%). This profile, characterized by an abundance of low-molecular-weight peptides, favors high solubility and efficient interaction with iron ions23,24. Notably, many DH-derived peptides are enriched in hydroxyproline, a residue reported to play a key role in iron metabolism. For instance, hydroxyproline-rich peptides from gum arabic were recently shown to stimulate intestinal iron absorption by stabilizing HIF-2α and upregulating iron transport proteins, highlighting the functional potential of Hyp-containing motifs25. By analogy, the prevalence of low-molecular-weight, hydroxyproline-rich peptides in DH likely underpins its superior capacity for iron binding and hematopoietic promotion.

The stability of iron carriers under physiological and processing conditions is critical for effective iron delivery in functional foods, as unstable carriers may precipitate or oxidize before absorption. In this study, the DH-Fe exhibited superior physicochemical stability to the HH-Fe in terms of pH tolerance, thermal resistance, and iron-binding capacity (Fig. 1). Iron absorption primarily occurs in the duodenum, where the pH ranges from slightly acidic to weakly basic. Under these conditions, free inorganic iron salts such as FeSO4 are prone to rapid precipitation and oxidation. Even though Fe3+ can be solubilized in the acidic milieu of the stomach, it cannot be directly transported to enterocytes5. In contrast, maintaining solubility within this range is essential for optimal bioavailability4. The DH-Fe maintained significantly higher levels of soluble iron fraction under both acidic and weakly basic conditions, indicating enhanced resistance to precipitation. This stability is likely due to stronger coordination between DH and iron ions, thereby stabilizing iron in its soluble form under gastrointestinal conditions, whereas FeSO4 lacks protective ligands and remains vulnerable to precipitation and redox cycling4,5. Thermal stability is vital for iron carriers used in fortified food products, as many undergo heat treatment during processing26. The DH-Fe showed excellent thermal resistance, maintaining high soluble iron fraction content across 20 °C to 100 °C, which makes it suitable for thermally processed foods where FeSO4 would otherwise lose stability. This performance reflects the strong thermal stability of the hydrolysate-iron complex, providing protection against heat-induced iron precipitation that typically limits FeSO4-based fortification. Additionally, DH-Fe exhibited a consistent iron-binding profile across various hydrolysate-to-iron ratios, whereas FeSO4 lacks such buffering capacity, making it prone to oxidation and precipitation and resulting in uncoordinated absorption in vivo5. In contrast to the HH-Fe, which exhibited instability at different iron concentrations, the DH-Fe showed a steady increase in soluble iron fraction content. This strong binding behavior may contribute to its thermal resistance, as supported by stability data, and may also reduce free iron-induced oxidative stress. This is particularly important since FeSO4 releases unbound iron ions that catalyze reactive oxygen species formation, increasing oxidative burden27. Overall, these findings highlight the superior stability of DH-Fe under variable pH and temperature conditions, supporting the potential of DH as a functional iron carrier. Unlike FeSO4, which suffers from rapid precipitation, uncoordinated absorption, and pro-oxidative effects, DH-Fe provides a more stable and safer delivery system. Its robust stability suggests enhanced bioavailability and broad applicability in food matrices exposed to pH and thermal challenges.

IDA is a prevalent global health concern characterized by fatigue, headaches, developmental delays in children, and premature birth21. Collagen polypeptides derived from Donkey-hide gelatin have been shown to exhibit hematopoietic activity by promoting hematopoiesis in anemic mice12. This study evaluated the efficacy of DH for alleviating IDA and investigated its mechanisms of enhancing iron absorption. The findings may contribute to the development of next-generation iron supplements with improved efficacy and reduced side effects.

The HH, DH, and HDH groups showed a rapid recovery toward near-normal body weight levels (Fig. 2C), whereas the IDA and FeSO4 groups continued to show weight deficits after 12 weeks of intervention. The slow weight gain in IDA rats likely resulted from impaired nutrient absorption13. Comparisons of weight gain rates revealed that treatment with HH, DH, and HDH significantly accelerated weight gain compared to FeSO4 (p < 0.05). Notably, the weight gain rate in the DH group was 109.96% of that in the FeSO4 group (Fig. 2D). This effect may result from the synergistic action of DH and iron, which not only replenished iron stores but also supplemented the body with protein-derived nutrients, such as amino acids and trace elements13. Physical improvements, such as improved coloration of limbs and noses, smoother fur, and increased vitality, were also observed (Fig. 2E). These findings suggest that DH can effectively alleviate the physiological symptoms of IDA in rats and demonstrate greater efficacy compared to FeSO4.

HGB, the primary component of RBCs, accounts for approximately 50% of total blood volume in humans1. As iron is an essential component of hemoglobin, iron deficiency reduces HGB levels, impairing the capacity of RBCs to transport oxygen and carbon dioxide28. After six weeks of intervention, the HGB level in the DH group was 121.15% of that in the FeSO4 group and nearly twice that of the IDA group (Fig. 3A). DH improved RBC count and RDW (Fig. 3B and G). The RBV in the DH group exceeded that in the FeSO4 group by 70%, and HGB regeneration efficiency was 169% greater (Fig. 3H and I). Previous studies have demonstrated that Donkey-hide gelatin can significantly alleviate anemia symptoms in patients with β-thalassemia and promote hematopoietic recovery in myelosuppressed mice29,30. The results of this study are consistent with previous findings. These findings suggest that DH significantly enhance iron absorption and utilization, underscoring their potential as a functional strategy for the dietary management of IDA.

In the IDA group, SI levels decreased to 14.60 μmol/L (Fig. 4A), indicating reduced iron availability for transferrin binding. This decline was accompanied by a significant increase in TIBC, which reached 149.25 μmol/L (Fig. 4C, p < 0.05). Treatment with DH significantly elevated SI levels and reduced TIBC (p < 0.05). Under iron-deficient conditions, ferritin releases stored iron into circulation, and its serum concentration is positively correlated with body iron stores31. The DH group showed significantly elevated SF levels (25.34 ng/mL) under the same iron dosage (p < 0.05). This value represented 127.72% of the level observed in the FeSO4 group (Fig. 4B). As the liver plays a pivotal role in maintaining iron homeostasis32, treatment with DH effectively ameliorated liver damage caused by IDA and FeSO4 (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that DH contributes to iron homeostasis by enhancing iron transport and storage. Moreover, DH outperformed FeSO4 in restoring iron-related biochemical parameters in IDA rats.

SOD, a key antioxidant enzyme, plays a crucial role in mitigating oxidative stress33. Both IDA and inorganic iron supplementation have been shown to induce oxidative stress, contributing to oxidative damage in vivo34. SOD activity was markedly reduced in the IDA and FeSO4 groups, while the DH group exhibited a 4% increase compared to the CON group (Fig. 4F). DH treatment lowered MDA levels to 7.91 nmol/mL, closely approaching those in the CON group (7.37 nmol/mL) (Fig. 4G). Animal-derived protein hydrolysates have been reported to alleviate oxidative stress via enzymatic hydrolysis35. Correlation analysis showed a significant positive association between SF and SOD, and a negative correlation between SF and MDA (Fig. 6C). These findings support the hypothesis that dysregulated iron metabolism contributes to oxidative stress36. HYP serves as a marker of collagen absorption in serum37. In the DH group, serum HYP levels rose to 11.53 μg/mL, representing 168.81% of those observed in the CON group (Fig. 4H). Collagen supplementation has been reported to enhance iron absorption38. Increased HYP levels stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α), thereby upregulating the expression of DMT1 and DcytB on the apical brush border of intestinal epithelial cells. Additionally, ferritin expression on the basolateral membrane is enhanced, facilitating intracellular iron storage39. A positive correlation between HYP and SF levels was observed (Fig. 6C), further supporting the findings of Malesza et al. Collectively, these results indicate that DH improves antioxidant defense and promotes iron absorption via collagen supplementation.

The gut microbiota plays an essential role in maintaining intestinal iron homeostasis21. Marked differences in gut microbiota composition were observed in the IDA and FeSO4 groups compared to the CON group. In contrast, the DH group exhibited a microbiota profile more similar to the CON group, suggesting that DH help restore gut microbial balance (Fig. 5B). IDA disrupted the Firmicutes/Bacteroidota ratio, a key indicator of intestinal microbial equilibrium14. This ratio was restored to normal levels after intervention with DH (Fig. 5C). Escherichia-Shigella exhibited significant proliferation in the IDA and FeSO4 groups (Fig. 5D), accompanied by marked iron accumulation in the intestines of the FeSO4 group (Fig. 6A). Certain bacteria, such as Escherichia, produce siderophores that sequester iron, thereby reducing dietary iron absorption into the bloodstream and aggravating IDA40. Correlation analysis revealed a significant negative association between Escherichia-Shigella and both HGB and HCT, suggesting its involvement in the progression of IDA, consistent with the findings of Seyoum et al. (Fig. 6D), consistent with the findings of Seyoum et al. Moreover, Escherichia-Shigella was positively correlated with MDA levels, indicating its contribution to inflammation41. Inflammatory responses upregulate hepcidin expression, which promotes ferroportin internalization and degradation, ultimately impairing systemic iron transport. A significant negative correlation between MDA and SF levels was also observed (Fig. 6C), supporting the observations reported by Malesza et al. 39. In the DH group, the increased abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Lachnospiraceae42, Clostridia_UCG-01443, and Ruminococcus44 may help alleviate intestinal inflammation and enhance iron absorption (Fig. 5D). Candidatus_Saccharimonas, a characteristic bacterium enriched in the DH group (Fig. 5F), exhibited significant positive correlations with HGB, HCT, and MCV, and a negative correlation with TIBC (Fig. 6D). This bacterium has been reported to be involved in immunomodulation and intestinal tissue repair45. Collectively, these results suggest that DH alleviates IDA and enhances iron absorption by modulating gut microbiota composition. By suppressing pathogenic bacteria, promoting beneficial microbes, and reducing intestinal inflammation, DH creates a favorable intestinal environment for effective iron absorption.

This study highlights the iron-binding stability of DH, confirms their effectiveness in alleviating IDA, and offers insights into the underlying mechanisms. Upon binding with iron, DH effectively maintained iron fraction solubility, even under varying pH levels, thermal conditions, and iron concentrations. Compared with FeSO4, DH exhibited superior efficacy in promoting iron bioavailability, as evidenced by improvements in hematological indicators, serum biochemical indicators, and gut microbiota composition. In addition, they supported hematopoiesis, regulated systemic iron homeostasis, and enhanced antioxidant capacity. Notably, they also alleviated gut microbial dysbiosis associated with both IDA and iron overload. These findings indicate that the combination of DH and iron represents a promising nutritional strategy for managing IDA. However, the stability of the interaction between protein hydrolysates and iron can be affected by external factors, including the form of iron supplements and processing methods. Future research should aim to optimize iron delivery systems to improve complex stability, thereby facilitating the development of next-generation iron supplements with enhanced bioefficacy and minimized side effects.

Methods

Materials

DH were provided by Dong-E-E-Jiao Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China) and stored at room temperature in a dry environment. HH were purchased from Hubei Rui Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Hubei, China). Ferrous sulfate (FeSO4, Food grade, 99.91%) was obtained from Henan Gaobao Industrial Co., Ltd. (Henan, China). All molecular weight standards were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Molecular weight distribution of HH and DH

The method described by Sha et al. 46 was adopted with slight modifications. The molecular weight distribution of HH and DH was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Separation was carried out on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with a gel filtration column (Waters XBridge Protein BEH 125 Å SEC, 3.5 μm × 7.8 mm). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (acetonitrile) and solvent B (deionized water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) mixed at a ratio of 4:6 (v/v), with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Calibration curves for relative molecular weight were established using the following standards: cytochrome C (12,384 Da), aprotinin (6500 Da), oxidized glutathione (612 Da), and L-hydroxyproline (131 Da). HH and DH samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm aqueous membrane filter and subsequently analyzed. The molecular weight distribution was calculated based on the calibration curve equation. The calibration curve was expressed as y = -0.1739x + 6.4353 (R² = 0.9955), which was obtained using the molecular weight standards.

pH stability

pH stability was modified based on in vitro simulated digestion conditions47. DH/HH solutions (1%, w/v) were mixed with FeSO4 (0.2%, w/v) and adjusted to various pH values (1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 8.0) using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min to remove insoluble precipitates. Soluble iron fraction content in the supernatant was measured to evaluate the pH stability of the DH/HH-Fe48.

Thermal stability

The thermal stability of DH/HH-Fe was evaluated using two different methods. DH and HH solutions (1%, w/v) containing FeSO4 (0.2%, w/v) were incubated at various temperatures (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 °C) for 30 min. After heat treatment, samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min to remove insoluble precipitates, and the soluble iron fraction content in the supernatant was measured to evaluate the thermal stability of DH/HH-Fe17. The other method employed differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a Discovery DSC2500 instrument (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) to investigate the thermal behavior of lyophilized DH-Fe and HH-Fe samples (3-5 mg, hydrolysate-to-iron ratio of 1:1) sealed in aluminum pans, with an empty pan as reference. DSC measurements were conducted from 20 °C to 250 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen flow of 20 mL/min17.

Binding stability

DH/HH solutions (1%, w/v) were mixed with FeSO4 at various peptide-to-iron mass ratios (100:1, 50:1, 5:1, 1:1) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After reaction, samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Soluble iron fraction content in the supernatant was measured to evaluate the saturation binding capacity and stability of peptide-iron complexes.

Animal experiment

Fifty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats (4 weeks old, SPF grade) were obtained from Zhejiang Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, China; license No. SCXK (ZHE) 2024-0001). Rats were housed under controlled conditions (24 ± 2 °C, 55 ± 5% relative humidity) with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Precautions were taken to avoid iron contamination during feeding. All experimental procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiangxi Normal University (approval No. 20210311-002).

All rats had ad libitum access to food and water. After a 1-week acclimation, rats were randomly assigned to either the control (CON, n = 9) or model (MOD, n = 45) group using body weight-stratified randomization (ranked by weight and allocated in permuted blocks according to a computer-generated random sequence) to ensure comparable baseline body weight. The CON group was fed a standard rodent diet (45 ppm Fe), whereas the MOD group received a customized low-iron diet (5 ppm Fe). Diets were supplied by Jiangsu Xietong Pharmaceutical Bio-engineering Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Starting from week 2, tail vein blood was collected weekly to monitor hemoglobin (HGB) levels. IDA was confirmed when hemoglobin levels dropped below 100 g/L49.

After successful induction of IDA, the MOD group (n = 45) was stratified by hemoglobin levels and evenly divided into five subgroups (n = 9 per group): IDA, FeSO4 (2 mg Fe/kg BW/day), HH (2 mg Fe + 200 mg HH/kg BW/day), DH (2 mg Fe + 200 mg DH/kg BW/day), and HDH (2 mg Fe + 100 mg HH + 100 mg DH/kg BW/day). Stratification by hemoglobin ensured comparable anemia severity across groups (p > 0.05). Dosage regimens were determined based on previous studies by Hu et al. and Cao et al. 36,50. Interventions were administered once daily by oral gavage and adjusted according to body weight; the CON and IDA groups received equal volumes of saline. The intervention lasted for 6 weeks (Fig. 2A), during which body weight was measured weekly.

To minimize selection bias, rats were initially allocated into CON and MOD groups by body weight–stratified randomization, ensuring comparable baseline characteristics. After IDA induction, MOD rats were further stratified by hemoglobin and divided into five subgroups (IDA, FeSO4, HH, DH, and HDH) with similar anemia severity. The CON group received a standard diet (45 ppm Fe), while all MOD-derived subgroups remained on a low-iron diet (5 ppm Fe) throughout, ensuring that observed differences resulted from the interventions rather than dietary iron.

Sample collection

At the end of the intervention period, rats were fasted for 12 hours and anesthetized with 5% isoflurane. Blood and serum samples were collected via cardiac puncture, followed by euthanasia through cervical dislocation. Liver, intestinal, and fecal tissues were harvested. All samples, excluding whole blood, were stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

Hematopoietic capacity

Hematopoietic capacity was analyzed using a veterinary automatic blood cell analyzer (BC-2800vet, Mindray Corporation, China). The evaluated indices included hemoglobin (HGB), red blood cell count (RBC), hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), and red cell distribution width (RDW). Previous studies reported that in anemic animals and those recovering from IDA, blood volume accounts for approximately 6.7% of body weight, with hemoglobin containing 0.335% iron (w/w)36. The relative biological value (RBV) and hemoglobin regeneration efficiency (HGBRE) were calculated using Eqs. 1–3. RBV is expressed relative to the FeSO4 group, which is set as 100%.

where:

A-Final HGB iron pool(mg)

B-Initial HGB iron pool(mg)

C-Total iron intake(mg)

D-HGB regeneration efficiency of each animal

E-HGB regeneration efficiency of the FeSO4 group

Iron homeostasis

The Iron homeostasis analyzed included serum iron (SI), serum ferritin (SF), total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), unsaturated iron-binding capacity (UIBC), and transferrin saturation (TS)10,18. UIBC and TS were calculated using Eqs. 4 and 5.

Oxidative stress and hydroxyproline

Serum concentrations of superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), and hydroxyproline (HYP) were measured using commercial assay kits following the manufacturers’ instructions. The HYP assay kit was obtained from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., while the SOD and MDA assay kits were procured from Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Research Institute.

Histomorphology

Fresh liver tissue was fixed in a tissue fixative solution, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5 μm-thick slices. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed under a microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

16S rRNA sequencing of fecal bacteria

Total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from fecal samples (n = 7) using the FastPure Stool DNA Isolation Kit (MJYH, Shanghai, China). The quality and concentration of extracted DNA were evaluated using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The hypervariable V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primer pair 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806 R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) on a T100 Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD, USA). PCR products were excised from a 2% agarose gel, purified using the PCR Clean-Up Kit (YuHua, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and quantified using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and sequenced using a paired-end strategy on the Illumina NextSeq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) according to standard protocols provided by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). After demultiplexing, the sequences were quality-filtered using fastp (v0.19.6) and merged with FLASH (v1.2.11). High-quality sequences were subsequently denoised using the DADA2 plugin in the Qiime2 (v2020.2) pipeline, achieving single-nucleotide resolution by modeling sample-specific error profiles. The denoised sequences generated by DADA2 were referred to as amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment of ASVs was conducted using the Naive Bayes classifier within Qiime2, employing the SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138). Data analysis was performed on the Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0. For data analysis, the maximum and minimum values in each group were excluded, and the mean of the remaining values was used. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple comparison test, was used for intergroup comparisons, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Graphs were generated using OriginPro 2024 software.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sun, B. et al. Effect of hemoglobin extracted from Tegillarca granosa on iron deficiency anemia in mice. Food Res. Int. 162, 112031 (2022).

James, S. L. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Characterization of oyster protein hydrolysate–iron complexes and their in vivo protective effects against iron deficiency-induced symptoms in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 16618–16629 (2023).

Man, Y. et al. Iron supplementation and iron-fortified foods: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 4504–4525 (2022).

Pantopoulos, K. Oral iron supplementation: New formulations, old questions. Haematologica 109, 2790–2801 (2024).

Nataraj, B. H. et al. Influence of exopolysaccharide EPSKar1–iron complexation on iron bioavailability and alleviating iron deficiency anaemia in Wistar rats. Food Funct. 14, 4931–4947 (2023).

Feng, Y., Wassie, T., Wu, Y. & Wu, X. Advances on novel iron saccharide-iron (III) complexes as nutritional supplements. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 64, 10239–10255 (2024).

Pan, W. et al. Food-derived bioactive oligopeptide iron complexes ameliorate iron deficiency anemia and offspring development in pregnant rats. Front. Nutr. 9, 997006 (2022).

Sha, X. et al. Casein phosphopeptide interferes the interactions between ferritin and ion irons. Food Chem. 454, 139752 (2024).

Xue, D. et al. Hemoglobin hydrolyzate promotes iron absorption in the small intestine through iron-binding peptides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 15237–15247 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Efficacy and safety of Ejiao (Asini Corii Colla) in women with blood deficient symptoms: A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 718154 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. Extraction and identification of collagen-derived peptides with hematopoietic activity from Colla Corii Asini. J. Ethnopharmacol. 182, 129–136 (2016).

Cheng, X. R. et al. Ejiao peptide-iron chelates regulate the metabolism of iron deficiency anemia mice and improve the bioavailability of iron. Food Biosci. 54, 102835 (2023).

Cheng, X. R., Guan, L. J., Muskat, M. N., Cao, C.-C. & Guan, B. Effects of Ejiao peptide–iron chelates on intestinal inflammation and gut microbiota in iron deficiency anemic mice. Food Funct. 12, 10887–10902 (2021).

Han, K. et al. Mechanisms of inulin addition affecting the properties of chicken myofibrillar protein gel. Food Hydrocoll. 131, 107843 (2022).

Chen, J., Chen, Q., Shu, Q. & Liu, Y. The dual role of mannosylerythritol lipid-A: Improving gelling property and exerting antibacterial activity in chicken and beef gel. Food Chem. 464, 141835 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Novel iron-chelating peptide from egg yolk: Preparation, characterization, and iron transportation. Food Chem. X 18, 100692 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Efficacy of polysaccharide iron complex in IDA rats: A comparative study with iron protein succinylate and ferrous succinate. Biomed. Pharmacother. 170, 115991 (2024).

Yu, Y. et al. Hepatic transferrin plays a role in systemic iron homeostasis and liver ferroptosis. Blood 136, 726–739 (2020).

He, H. et al. Dual action of vitamin C in iron supplement therapeutics for iron deficiency anemia: Prevention of liver damage induced by iron overload. Food Funct. 9, 5390–5401 (2018).

Sun, B. et al. Iron deficiency anemia: A critical review on iron absorption, supplementation and its influence on gut microbiota. Food Funct. 15, 1144–1157 (2024).

Gong, H. et al. Structural characteristics of steamed Polygonatum cyrtonema polysaccharide and its bioactivity on colitis via improving the intestinal barrier and modifying the gut microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 327, 121669 (2024).

Hong, H., Fan, H., Chalamaiah, M. & Wu, J. Preparation of low-molecular-weight, collagen hydrolysates (peptides): Current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Food Chem. 301, 125222 (2019).

He, X. et al. Industry-scale microfluidization as a potential technique to improve solubility and modify structure of pea protein. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 67, 102582 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Gum arabic-derived hydroxyproline-rich peptides stimulate intestinal nonheme iron absorption via HIF2α-dependent upregulation of iron transport Proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 3622–3632 (2024).

Mihaly Cozmuta, A. et al. Thermal stability and in vitro digestion of alginate–starch–iron beads for oral delivery of iron. Food Hydrocoll. 142, 108808 (2023).

Ostertag, F., Grimm, V. J. & Hinrichs, J. Iron saturation and binding capacity of lactoferrin - development and validation of a colorimetric protocol for quality control. Food Chem. 463, 141365 (2025).

Rusu, I. G. et al. Iron supplementation influence on the gut microbiota and probiotic intake effect in iron deficiency—A literature-based review. Nutrients 12, 1993 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Hematopoietic effects and mechanisms of Fufang E׳jiao Jiang on radiotherapy and chemotherapy-induced myelosuppressed mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 152, 575–584 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Therapeutic effect of Colla corii asini on improving anemia and hemoglobin compositions in pregnant women with thalassemia. Int. J. Hematol. 104, 559–565 (2016).

He, H. et al. Effectiveness of AOS–iron on iron deficiency anemia in rats. RSC Adv. 9, 5053–5063 (2019).

Rishi, G. & Subramaniam, V. N. The liver in regulation of iron homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. -Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 313, G157–G165 (2017).

Hu, S. et al. Molecular mechanisms of iron transport and homeostasis regulated by Antarctic krill-derived heptapeptide–iron complex. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 7517–7532 (2024).

Zhang, X.-G. et al. Preparation of S-iron-enriched yeast using siderophores and its effect on iron deficiency anemia in rats. Food Chem. 365, 130508 (2021).

Ding, Y., Ko, S.-C., Moon, S.-H. & Lee, S.-H. Protective effects of novel antioxidant peptide purified from alcalase hydrolysate of velvet antler against oxidative stress in Chang liver cells in vitro and in a zebrafish model in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5187 (2019).

Hu, S. et al. Iron complexes with Antarctic krill–derived peptides show superior effectiveness to their original protein–iron complexes in mice with iron deficiency anemia. Nutrients 15, 2510 (2023).

Kleinnijenhuis, A. J. et al. Non-targeted and targeted analysis of collagen hydrolysates during the course of digestion and absorption. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412, 973–982 (2020).

Zhu, S. et al. Collagen peptides as a hypoxia-inducible factor-2α-stabilizing prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor to stimulate intestinal iron absorption by upregulating iron transport proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 15095–15103 (2022).

Malesza, I. J. et al. The dark side of iron: The relationship between iron, inflammation and gut microbiota in selected diseases associated with iron deficiency anaemia—A narrative review. Nutrients 14, 3478 (2022).

Seyoum, Y., Baye, K. & Humblot, C. Iron homeostasis in host and gut bacteria – a complex interrelationship. Gut Microbes 13, 1874855 (2021).

Loveikyte, R., Bourgonje, A. R., Van Goor, H., Dijkstra, G. & Van Der Meulen–De Jong, A. E. The effect of iron therapy on oxidative stress and intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases: A review on the conundrum. Redox Biol. 68, 102950 (2023).

Vacca, M. et al. The controversial role of human gut Lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms 8, 573 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Liubao insect tea polyphenols ameliorate DSS-induced experimental colitis by protecting intestinal barrier and regulating intestinal microbiota. Food Chem. 467, 142156 (2025).

Shearer, J., Shah, S., MacInnis, M. J., Shen-Tu, G. & Mu, C. Dose-responsive effects of iron supplementation on the gut microbiota in middle-aged women. Nutrients 16, 786 (2024).

Ge, H. et al. Egg white peptides ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute colitis symptoms by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and modulation of gut microbiota composition. Food Chem. 360, 129981 (2021).

Sha, X. M. et al. In vitro gastrointestinal digestion of thermally reversible and irreversible fish gelatin induced by microbial transglutaminase. Food Hydrocoll. 145, 109079 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Ding, X. & Li, M. Preparation, characterization and in vitro stability of iron-chelating peptides from mung beans. Food Chem. 349, 129101 (2021).

Shubham, K. et al. Iron deficiency anemia: A comprehensive review on iron absorption, bioavailability and emerging food fortification approaches. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 58–75 (2020).

Song, S. et al. Antioxidant activity of a Lachnum YM226 melanin–iron complex and its influence on cytokine production in mice with iron deficiency anemia. Food Funct. 7, 1508–1514 (2016).

Cao, C. et al. Oral intake of chicken bone collagen peptides anti-skin aging in mice by regulating collagen degradation and synthesis, inhibiting inflammation and activating lysosomes. Nutrients 14, 1622 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32302147), the Centrally Government Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project (YDZX2023090), and the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20224BAB205045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.-B.L.: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. C.-Y.P.: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis. H.W.: Writing-review & editing, Project administration. Y.-E.S.: Writing-review & editing, Project administration. X.-B.D.: Writing-review & editing, Project administration. H.-B.L.: Writing-review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. X.-Y.L.: Software, Investigation, Formal analysis. L.-Y.Y.: Software, Formal analysis. Z.-C.T.: Conceptualization, Supervision. X.-M.S.: Methodology, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition, Data curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, HB., Peng, CY., Wang, H. et al. Stability and iron affinity of Donkey-hide gelatin hydrolysates: Implications for improving iron bioavailability and gut microbiota modulation. npj Sci Food 9, 254 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00617-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00617-2