Abstract

HepG2 cells were cultured into liver organoids (more native liver-like than 2D cultures) and integrated into a microfluidic chip, which regulates flow, nutrients, and waste to simulate in vivo hepatic microcirculation. Key findings: Cadmium (Cd) exposure shows a positive dose-response with liver damage; 40 ng/mL selenium (Se) alleviates 3 sets of liver biochemical dysfunctions under 40 μg/mL Cd co-exposure, but 160/640 ng/mL Se diminishes this protection. Metabolomics (40 μg/mL Cd vs. 640 ng/mL Se+Cd) identified two mechanisms: high Se induces oxidative stress and disrupts liver cellular metabolism. This study provides data/theory for rational Se use against Cd-induced liver dysfunction. The platform integrates organoid/organ-on-a-chip assessments with microfluidic metabolomics (a cross-scale toxicological system) and informs 3D cell model development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cadmium-contaminated rice is a significant global food safety concern, primarily caused by cadmium accumulation in rice due to soil cadmium pollution1,2. Long-term intake of cadmium-contaminated rice increases human cadmium exposure, leading to chronic damage to the liver and kidneys, characterized by enhanced oxidative stress and abnormal cell apoptosis3,4. Existing studies have confirmed that consuming selenium-rich foods (such as selenium-enriched tea and selenium-enriched grains) can alleviate cadmium-induced liver and kidney damage by regulating the antioxidant system and inhibiting inflammatory responses5. However, the specific molecular mechanisms (e.g., competitive binding between selenium and cadmium, regulation of key signaling pathways) remain unclear, and the safe selenium dosage standards for different populations (e.g., children, the elderly) have not been unified, requiring further research6.

Organoids/organ-on-a-chip, as an emerging platform integrating cell technology, microfluidic engineering, and biomaterials science, hold great promise in biological/food safety assessment and scientific research7,8. Their ability to simulate the 3D structure, physiological microenvironment, and dynamic functions of human organs enables more accurate reflection of in vivo processes induced by pollutants or food components, such as toxin metabolism and cellular stress responses9. With technological advancements (e.g., multi-organ chip integration and sensor incorporation), this platform is gradually addressing issues like low throughput and insufficient standardization. It will increasingly replace traditional models in food toxicology screening and functional ingredient evaluation, becoming a mainstream research tool10. In recent years (year 2020~), more studies have used cell lines or tumor cells to generate organoids, rather than pluripotent stem cells or organ progenitors11,12.

To address these challenges, our study innovatively integrates organoid-based molecular and histopathological analyses with microfluidic metabolomics. By culturing liver organoids in a microfluidic organ-on-a-chip system, we can precisely control cadmium and selenium exposure levels, simulate physiological fluid dynamics, and thus more accurately recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment. The technical roadmap of this study is shown in Fig. 1. Metabolomic profiling will be used to map real-time metabolic changes, offering a holistic view of the biochemical alterations triggered by co-exposure. This integrated approach is expected to reveal novel protective mechanisms of selenium against cadmium toxicity, identify Construction of 3D HepG2 Liver Organoids: 3D HepG2 liver organoids were successfully constructed, with dynamic morphological and functional characteristics verified (Fig. 2A, B): Morphological evolution: Dispersed single cells (Day 0) aggregated into loose clumps (Day 3, initial prototypes), fused into regular spheres with stratification (Day 5), and matured into glossy, liver lobule-like spheres (Day 7, microstructural similarity to liver tissue). Functional validation: Fluorescence staining showed liver-like cell layering/zoning; ALB staining confirmed albumin synthesis, and ZO-1 staining demonstrated intact tight junctions (Fig. 3B), indicating structural/functional maturation. Stability: Organoids maintained stable development in vitro for 2 weeks, serving as a platform for liver research, disease modeling, and drug screening development of advanced 3D cell model platforms for toxicological research.

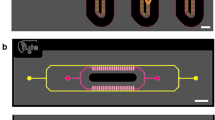

A Expansion of HepG2 cells. Aa: Microscopic images of HepG2 2D cells; Ab: Physical picture of HepG2 2D cell culture dish; Ac: Growth time microscopy images of 3D liver organoid. B Construction of HepG2 3D liver organoids. Ba: U-type ultra-low adsorption 96-well plate physical picture; Bb: 3D organoid culture physical drawing; Bc: Growth time microscopy images of 3D liver organoid; Bd: Confocal fluorescence images of 3D liver organoids. C Construction of HepG2 Livers-on-a-Chip. Ca: Schematic diagram of livers-on-a-chip cell culture process; Cb: Physical drawing of the liver chip microfluid system; Cc: Confocal fluorescence images of liver chip.

Results

Construction of the HepG2-derived organoid and organ-on-a-chip platforms

Successfully constructed the 3D HepG2 liver organoids: 3D HepG2 liver organoids were successfully constructed, with dynamic morphological and functional characteristics verified (Fig. 2A, B). Morphological evolution: Dispersed single cells (Day 0) aggregated into loose clumps (Day 3, initial prototypes), fused into regular spheres with stratification (Day 5), and matured into glossy, liver lobule-like spheres (Day 7, microstructural similarity to liver tissue) (Fig. 3A). Functional validation: Fluorescence staining showed liver-like cell layering/zoning; ALB staining confirmed albumin synthesis, and ZO-1 staining demonstrated intact tight junctions (Fig. 3B), indicating structural/functional maturation. Stability: Organoids maintained stable development in vitro for 2 weeks, serving as a platform for liver research, disease modeling, and drug screening.

Successfully constructed the 3D HepG2 Liver Organ-on-a-Chip: HepG2 liver organ-on-a-chip was successfully constructed (Fig. 2C). Key indicators verified. Fluid system mimicked in vivo liver flow (10 μL/h, live-cell monitored, Fig. 4A), enabling diffusion/transport and normal sinusoid-cord material exchange13,14. Cells (1 × 106/mL, Fig. 4B) attached to hydrogel/chip; 5 h: pseudopodia/proliferation; 10 h: clumps/ intercellular connections. Immunofluorescence (Fig. 4C): robust ALB (protein synthesis) and continuous ZO-1 (tight junctions). It serves as a biomimetic liver study platform, complementing 3D organoids. Metabolomic analyses used microfluidic effluent as the sample, which captures cellular metabolic outputs (secretion and excretion). These outputs are tightly linked to intracellular processes, thus ensuring the effluent reflects intracellular metabolic changes.

Molecular toxicologic study with HepG2-derived liver organoids

Relative to the control (CK) group, HepG2 3D organoids in the t-BHP group, c alongside those exposed to cadmium at concentrations of 30 μg/mL, 40 μg/mL, and 50 μg/mL, displayed varying degrees of elevation in levels of intracellular ROS (measured by probe assay), MDA, 8-OHdG, NFκB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, Casp-3, Nrf2, γ-GCS, ALT, AST, LDH, and TBA (see Fig. 5B and Table 1). Conversely, levels of GSH and ALB were markedly reduced. These results demonstrate that cadmium exposure induces oxidative stress, inflammation, and hepatic dysfunction, thereby eliciting a significant deleterious effect on HepG2 3D organoids in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment with low-concentration selenium (40 ng/mL) conferred a significant protective effect against cadmium-induced damage. However, as selenium concentrations increased (160 ng/mL and 640 ng/mL), it may exert toxicological effects or form more complex toxic complexes with cadmium, further exacerbating injury to liver organoids and counteracting or even reversing its initially observed protective effect. Our findings align with those of other investigators.

A Scientific hypothesis: potential mechanisms of Se protect liver against Cd-induced dysfunction. B Levels of biochemical indicators of oxidative damage, anti-oxidative feedback, inflammation, and liver dysfunction in different groups (n = 6). The color and size of the circles indicate the value of each indicator. The left side indicates the name of the biochemical indicator. Different group names are shown above. (Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test). Compared with the CK group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; Vitamin C (VitC) + Cd40μg/mL group or VitC + t-BHP group compared with the VitC group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01; Se40 ng/mL + Cd40μg/mL group compared with the Cd40 μg/mL group. &p < 0.05. &&p < 0.01). For more detailed data please see Supplementary Figs. S1–S4.

Cell toxicologic study of the exposure agents with HepG2-derived liver organoids

To ensure the integrity of this study, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of three tested substances (see Fig. 6). In addition to cadmium and selenium, we included t-BHP, a positive control commonly used in oxidative damage, cytotoxicity, and safety assessments. The results demonstrated that t-BHP exerted toxic effects within a normal range in liver organoids (see Fig. 6A). Figure 6B illustrates that, compared with the control group, cadmium-induced cytotoxicity at concentrations ranging from 30 to 65 μg/mL; in contrast, selenium exposure alone yielded a safe concentration range of 20–640 ng/mL for cells (Fig. 6C). The findings of this cytotoxicity assay were consistent with those of the previously described in molecular toxicology study15.

Histopathologic analysis of HepG2-derived liver organoids

To verify the properties of constructed liver organoids, immunofluorescence staining targeted multiple liver-specific markers. ALB staining showed strong fluorescence in the epithelial-like cell layer, indicating these cells retain the ability to synthesize and secrete ALB, a crucial hepatic function. For Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a tight junction protein connecting epithelial and endothelial cells, staining revealed its localization on the inner cytoplasmic membrane, where it interacts with other tight junction proteins to form a functional network. Hoechst detection demonstrated widespread nuclear expression in organoids. Together, these findings confirm the organoids exhibit liver-specific differentiation, with marker distribution resembling natural liver tissue, validating their molecular effectiveness.

Immunofluorescence results for different HepG2 3D organoid groups appear in Fig. 7. Following exposure to cadmium and t-BHP, ALB and ZO-1 fluorescence weakened significantly compared to controls. Their distribution showed localized aggregation, forming high-expression patches in some areas while remaining low in others, suggesting the treatments inhibited ALB and ZO-1 synthesis/secretion, causing functional abnormalities.

A The immunofluorescence staining images of liver organoids, where red indicates ZO-1, green represents ALB, and blue denotes cell nucleus; B the fluorescence quantification level of ALB; C the fluorescence quantification level of ZO-1 (n = 3). Compared with control group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; compared with Vit C group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01; compared with Cd 50 μg/mL group, &p < 0.05.

Treatment with Vitamin C and varying selenium concentrations mitigated cadmium toxicity, altering ALB and ZO-1 fluorescence. Notably, fluorescence intensity increased at lower selenium concentrations (40 ng/mL) but diminished with higher levels (160 ng/mL and 640 ng/mL), indicating selenium enhances protein synthesis/secretion within an optimal range, while excess induces toxicity that reduces these functions.

Histopathologic analysis of HepG2-derived livers-on-a-chip

Under standard culture conditions, liver organoids maintain stable functions in synthesizing and secreting ALB and ZO-1, with their cellular morphology and functionality preserved at basal levels. In this study, we used the t-BHP group and the 30, 40, and 50 μg/mL Cd groups for exposure to induce a pathological model. The results showed that, compared with the CK group, in the liver organoid chip experiments, the ALB expression levels in the cadmium exposure groups with different concentrations were significantly reduced. Moreover, the intracellular distribution of ALB appeared disordered and sparse, indicating that severe cadmium exposure interferes with the normal synthesis and secretion functions of hepatocytes. Meanwhile, ZO-1 expression was also significantly decreased, and the positioning of intercellular junctions appeared blurred and disrupted, suggesting damage to the tight junction structure between cells and impairment of liver barrier function. This effect was particularly prominent in the 40 μg/mL Cd and 50 μg/mL Cd groups. However, after specific intervention, compared with the 40 μg/mL Cd group, the VitC + 40 μg/mL Cd group showed significantly enhanced hepatocyte activation, proliferation, and protein expression (see Fig. 8).

A The immunofluorescence staining images of liver organoids, where red indicates ZO-1, green represents ALB, and blue denotes cell nucleus; B the fluorescence quantification level of ALB; C the fluorescence quantification level of ZO-1 (n = 3). Compared with control group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; compared with Vit C group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01; compared with Cd 50 μg/mL group, &p < 0.05).

In the selenium-protected groups (Se40 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL), compared with the cadmium exposure groups (Cd30, Cd40, and Cd50 μg/mL), ALB expression rebounded significantly, and its distribution became more regular and orderly. This indicates that selenium can mitigate the damage caused by cadmium to ALB synthesis and secretion, thereby promoting the restoration of normal protein metabolism in hepatocytes. Additionally, ZO-1 expression increased, and the continuity and integrity of intercellular junctions were partially restored, suggesting that selenium exerts a protective effect against cadmium-induced damage to tight junctions between hepatocytes.

However, with increasing selenium concentration (160 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL and 640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL), the expression levels of ALB and ZO-1 tended to decrease. This finding further emphasizes the protective role of selenium in alleviating cadmium-induced hepatocyte damage in the liver organoid chip model. Within the lower range of selenium concentrations (Se 40 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL), protein expression remained relatively stable initially; yet, once the selenium concentration exceeded a certain threshold, a steady decline in protein expression was observed.

Microfluidic effluent metabolomics of livers-on-a-chip: CK group vs Cd40 μg/mL group

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the metabolic impacts of cadmium (Cd) exposure on liver tissue organ chips, we performed a comparative metabolomics analysis between the Cd40 group and the control group (CK), with results presented in Fig. 9. During data preprocessing, metabolites with more than 20% missing values were removed. Remaining missing values were imputed with the minimum detected value for each compound, followed by total sum normalization and exclusion of metabolites with RSD > 30%. As illustrated in Fig. 9A, B, principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) revealed distinct clustering and clear separation trends in metabolite profiles between the CK group and the Cd 40 μg/mL group, indicating substantial differences in their metabolic patterns. A total of 1458 and 1444 metabolites was detected in the CK and Cd 40 μg/mL groups, respectively, with 1397 metabolites shared between the two groups (Fig. 9D). The non-overlapping metabolites represent compounds that were detected in only one group due to their relative abundance being below the limit of detection in the other group. In the volcano plot, significantly different metabolites were defined as those with P < 0.05, VIP_pred_OPLS-DA > 1, and a fold change (FC) > 1 or < 1. Compared to the CK group, the Cd 40 μg/mL group exhibited 332 significantly upregulated metabolites and 189 significantly downregulated metabolites (Fig. 9C). To identify key differential metabolites that could distinguish the two groups, we applied a threshold of variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1. The top 30 metabolites meeting this criterion are displayed in a heatmap (Fig. 9E and Table S1). These significant differential metabolites include ziprasidone, dapagliflozin 3-O-glucuronide, hyaluronan biosynthesis precursor 1, luteolin 7-O-(2-apiosyl-6-malonyl)-glucoside, 3-methylcholanthrene, and 23-hydroxyphysalolactone, among others, all of which were significantly elevated in the Cd40 μg/mL group relative to the CK group. To explore the biological pathways involving these significant differential metabolites and uncover potential molecular mechanisms, we mapped these metabolites to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Statistical analysis (t-test, p < 0.05) identified pathways with significant enrichment between the groups. Based on KEGG analysis, the top 10 enriched pathways were: long-term potentiation, cocaine addiction, spinocerebellar ataxia, alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, ABC transporters, D-amino acid metabolism, bile secretion, vitamin digestion and absorption, drug metabolism - cytochrome P450, and choline metabolism in cancer (Fig. 9F).

CK group vs Cd40 μg/mL group after cadmium exposure. A PCA analysis. B PLS-DA analysis. C Volcano plot of differential metabolites between the CK group and the Cd40 μg/mL group. D Venn diagram of metabolites between the CK group and the Cd40 μg/mL group. E Expression profile and VIP of metabolites. F KEGG enrichment analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Metabolomics of livers-on-a-chip: Cd40 μg/mL vs Se640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL group

Previous studies on cadmium-selenium co-exposure have revealed an intriguing phenomenon: high concentrations of selenium not only fail to alleviate cadmium-induced oxidative damage but may also exacerbate cellular oxidative injury. This observation has attracted our particular attention, prompting the present study to investigate its underlying mechanisms. To comprehensively assess the impact of high-concentration selenium on the metabolic profile of cadmium-treated liver organ chips, we performed partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), with results presented in Fig. 10A. This analysis revealed significant metabolic discrepancies between the cadmium-treated group (Cd40 μg/mL) and the high-concentration selenium co-treated group (Se640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL). These differences were further visualized via a volcano plot (Fig. 10B), which identified 145 upregulated metabolites, 330 downregulated metabolites, and 963 metabolites with no significant changes in abundance. The top 30 differential metabolites were displayed in a heatmap (Fig. 10C). In the Se640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL group, the abundances of metabolites such as behenic acid, 24-hydroxytetracosanoic acid, arachidic acid, rhamnazin 3-sophoroside, glucocorticoid receptor agonist, gibberellin A62, delta-viniferin, and physcion 8-gentiobioside were significantly reduced, whereas 3,5-dihydroxydecanoic acid and S-acetyldihydrolipoamide were significantly increased. Categorization of differential metabolites (Fig. 10D) showed that lipids accounted for the largest proportion. Additionally, all differential metabolites were subjected to KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, and the top 20 significantly enriched pathways were visualized using a bubble chart (Fig. 10E). These pathways included β-alanine metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, and D-amino acid metabolism, among others, which are closely associated with the core mechanisms of oxidative stress and hepatic metabolic dysregulation. The activation of these pathways may represent the synergistic mechanism by which high-concentration selenium exacerbates cadmium-induced hepatic dysfunction.

Metabolic effects of high-concentration selenium on cadmium-exposed HepG2 livers-on-a-chip. A PLS-DA analysis; B volcano plot of differentially expressed metabolites between the Cd40 μg/mL group and Se640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL group; C expression profile of significantly differentially expressed metabolites between the Cd40 μg/mL group and Se640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL group. D Classification of significantly differentially expressed metabolites between the Cd 40 μg/mL group and 640 ng/mL + Cd 40 μg/mL group; E KEGG metabolic pathway enrichment of the Cd 40 μg/mL group and 640 ng/mL + Cd 40 μg/mL group.

Discussions

This study employed liver organoids and Livers-on-a-chip derived from HepG2 cells to investigate cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity, as well as the protective effects and mechanisms of selenium under cadmium-selenium co-exposure conditions. A systematic molecular toxicology analysis was conducted using cells isolated from liver organoids. The research indicators included three biomarkers reflecting oxidative stress and damage (ROS, MDA, 8-OHdG), three factors associated with the Nrf2 pathway that indicate cellular antioxidant levels (Nrf2, γ-GCS, GSH), five factors related to the NF-κB pathway that reflect cellular inflammation and apoptosis levels (NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, Caspase-3), and five biochemical indicators signifying hepatocellular dysfunction (ALB, AST, ALT, TBA, LDH).

Results demonstrated that cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity is characterized by oxidative stress and inflammation. Specifically, with increasing cadmium exposure levels, the extent of oxidative stress and damage escalated; concurrently, the antioxidant-related factors Nrf2 and γ-GCS exhibited a feedback-induced increase16,17. The degree of cellular inflammation and apoptosis (Caspase-3) was aggravated, ultimately leading to cellular dysfunction, findings that align with the conclusions of other researchers and our initial scientific hypothesis. Furthermore, our results indicated that selenium exerts an antagonistic (protective) effect against cadmium, but it does not act like a typical antioxidant, as it fails to exhibit a positive dose-response relationship. Notably, low-concentration selenium (Se 40 ng/mL) is safely and effectively counteracts cadmium-induced hepatic toxicity; in contrast, higher concentrations of selenium (Se 160 ng/mL and Se 640 ng/mL) exacerbate such toxicity. This phenomenon has been previously documented in scholarly literatures18,19. Additionally, our study revealed that under co-exposure conditions (Se 640 ng/mL + Cd 40 μg/mL group vs. Cd 40 μg/mL group), the addition of selenium reduced the activation level of the Nrf2 antioxidant transcription factor (see Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S5B). In fact, long-term high-dose selenium exposure (e.g., dietary intake ≥300 μg Se/d) can elicit human hepatotoxicity, along with endocrine dysfunction, gastrointestinal distress, and other associated symptoms20.

In Fig. 5, when the HepG2 organoids were exposed in Cd (30, 40, 50 μg/mL) medium, the ZO-1 and ALB expression in HepG2 organoids were stronger on the outer side, and weaker on the inner side. The localization of protein in them was different. We propose that this phenomenon may be attributed to the “stress compensation response” of cells, which leads to the temporary upregulation of target proteins21,22. In Fig. 6, the expression of ZO-1 was enhanced in both the Se640 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL and Se640 ng/mL + t-BHP treated groups. This phenomenon may be attributed to the anti-oxidative effect of selenium. Cadmium (Cd) and t-BHP induce severe oxidative stress, which disrupts tight junctions by damaging proteins such as ZO-1. Selenium (Se) is a core component of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., glutathione peroxidase). At a concentration of 640 ng/mL, Se likely enhances the activity of these enzymes, protecting the structure and expression of ZO-1, and maintaining the integrity of tight junctions.

In this study, we established a novel metabolomics analysis technique using microfluidic effluent generated from organ chip operations, thereby verifying the effectiveness of this innovative analytical approach. Metabolomics analysis showed that cadmium disrupts drug metabolism pathways, as evidenced by increased levels of metabolites such as ziprasidone and dapagliflozin 3-O-glucuronide. This disruption is likely attributed to the suppression of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) activity, which impairs detoxification processes and exacerbates drug accumulation23. Oxidative stress further promotes the release of inflammatory factors (see Figs. 3B and S4B), disrupting extracellular matrix synthesis and causing the accumulation of intermediate metabolites. Elevated levels of antioxidants (e.g., luteolin 7-O-(2-apiosyl-6-malonyl)-glucoside) and lipid peroxidation markers (e.g., 23-hydroxyphysalolactone) suggest a hepatic response to oxidative damage24,25.

KEGG analysis highlighted two key metabolic alterations: first, the upregulation of ABC transporters, which serves as a compensatory mechanism to facilitate cadmium excretion26,27; second, the disruption of D-amino acid metabolism, which further exacerbates oxidative damage and cellular dysfunction28. Downregulation of CYP450-related pathways reduced bile acid metabolism and disrupted hormonal balance29,30, while suppression of alpha-linolenic acid metabolism weakened anti-inflammatory defenses, thereby increasing the risk of oxidative stress and liver damage31. Collectively, these findings underscore that cadmium severely disrupts hepatic metabolic and detoxification functions.

The exacerbation of hepatocellular dysfunction by high-concentration selenium is a critical focus of this study. Compared with the Cd 40 μg/mL group, the Se 640 ng/mL + Cd 40 μg/mL group exhibited significantly reduced levels of long-chain fatty acids (e.g., behenic acid, arachidic acid), a change indicating aggravated lipid metabolism disorders. This aligns with findings that cadmium-induced lipid peroxidation can be exacerbated by improper antioxidant intervention32, likely caused by selenium-induced lipid peroxidation33,34. This reduction in long-chain fatty acids suggests membrane damage, which further exacerbates liver injury. Levels of hormonal metabolites (e.g., rhamnazin 3-sophoroside, glucocorticoid receptor agonist) were also significantly decreased, reflecting disruptions in the endocrine network; this effect may be attributed to selenium-enhanced ROS production35. Lower levels of flavonoids and glycosides (e.g., delta-viniferin) indicate weakened antioxidant defenses, which are overwhelmed by persistent oxidative stress. Lipid metabolism and oxidative damage are tightly interconnected: dysregulated lipid metabolism promotes lipid peroxides (e.g., MDA) and oxidative stress, while oxidative damage impairs key lipid-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., ACC, CPT1), exacerbating lipid accumulation. Consistent with previous studies on HepaRG models, cadmium-induced hepatocellular lipotoxicity and lipidome alterations have been well-documented, further supporting this crosstalk32,36. Mitigating oxidative damage may ameliorate lipid dysregulation, and future work should explore underlying molecular links.

Elevated levels of metabolites such as 3,5-dihydroxydecanoic acid suggest abnormal fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction, which are worsened by selenium-induced metabolic stress37. Reduced levels of carboxylic acids (including behenic acid) further confirm disrupted fatty acid metabolism, resulting from selenium-induced promotion of peroxidation and suppression of fatty acid synthesis38. Key metabolic pathways, including beta-alanine metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, and D-amino acid metabolism, were significantly altered: overactivation of beta-alanine metabolism increased cellular energy burden while weakening antioxidant capacity; downregulation of cholesterol metabolism suggested impaired bile acid synthesis and detoxification, due to suppressed cholesterol-related pathways39; and inhibition of D-amino acid metabolism reflected heightened oxidative stress. In summary, high concentrations of selenium exacerbate cadmium-induced liver damage by intensifying oxidative stress and metabolic disruptions.

In food safety evaluation, the HepG2 cell line is a highly recommended and widely used model organism40. Derived from human liver cancer tissue, the HepG2 cell line boasts distinct advantages: it is easily accessible, requires simple culture conditions, can be stably passaged for an extended period, and ensures excellent experimental reproducibility41. It retains the core functions of hepatocytes, being capable of synthesizing albumin and secreting urea. Moreover, it exhibits the activity of various drug-metabolizing enzymes (such as the CYP450 enzyme system), enabling it to simulate the metabolic processes of the human liver42. In food safety evaluation, the HepG2 cell line can be used to detect the hepatotoxicity of food contaminants (e.g., heavy metals, mycotoxins) and assess the impacts of food additives and functional ingredients on the liver43. Additionally, by analyzing indicators including cell viability, oxidative stress markers, and metabolites, it can predict the in vivo safety of food components. This provides an efficient and low-cost in vitro model for food safety assessment, reducing reliance on animal experiments44.

Additionally, our research confirmed that both organoids and organ chips constructed from HepG2 cells are suitable for histopathological analysis (see Figs. 4 and 5). This finding is expected to significantly advance the application of organoid and organ-on-a-chip technologies in food safety evaluation, as alternatives to traditional animal-based toxicology research. Table 2 presents our preliminary insights into the histopathological analysis and other key characteristics of these two 3D cell model platforms.

In short, organoids and organ-on-a-chip serve different roles. Organoids contain sufficient cells for molecular toxicological measurements, while organ-on-a-chip is very suitable for metabolomic analysis (Table 2).

Regarding the safe dose of selenium (Se) exposure, results of the cell viability assay for Se-only exposure (Fig. 4) demonstrated that when Se acted alone at concentrations ranging from 20 to 640 ng/mL, it exhibited cellular safety (p > 0.05 vs. the control group). However, when Se was co-exposed with cadmium (40 μg/mL), Se at 40 ng/mL primarily exerted a protective effect on cells. This was specifically manifested as the downregulation of ROS, MDA, TNF-α, NFκB, ALT, LDH, and TBA expression levels, alongside the upregulation of ALB and GSH expression levels (vs. the 40 μg/mL cadmium group, &p < 0.05 or &&p < 0.01). A secondary effect of 40 ng/mL Se was the downregulation of Nrf2 expression (vs. the 40 μg/mL cadmium group, &p < 0.05). This may be attributed to the fact that reduced ROS levels downregulate Nrf2 activation by feedback effect (see Fig. 3A). When Se was co-exposed with 40 μg/mL cadmium at higher concentrations (160 ng/mL and 640 ng/mL), its protective effect against cadmium toxicity did not enhance; instead, it exhibited a dose-dependent decrease. Specifically, this co-exposure resulted in the upregulation of ROS, 8-OHdG, MDA, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, Casp-3, NFκB, AST, LDH, and TBA expression levels, and a concurrent downregulation of ALB and GSH expression levels (see Fig. 3; for detailed data, see Supplementary Figs. S1–S4). This finding is consistent with previous literature45, which has demonstrated that under conditions of Cd-Se co-exposure, low selenium (Se) concentrations (e.g., 40 ng/mL) afford a more potent protective effect against cadmium (Cd)-induced hepatotoxicity than high Se concentrations (e.g., 160 ng/mL and 640 ng/mL). However, the highlight of our findings resides in the discovery of the hepatocellular metabolomic mechanism underlying this phenomenon.

Finally, this study has several limitations: (1) The HepG2 cell model has low drug-metabolizing enzyme expression and inherent cancer cell proliferative traits. (2) Immunofluorescence had a small sample size (n = 3), lowering statistical reliability. (3) ALB and ZO-1 alone cannot confirm hepatocyte metabolic function. (4) Only vitamin C was used as the antioxidant control. (5) Specific lipid metabolism parameters (linked to membrane integrity/energy dysregulation, key toxicological readouts) were not fully addressed. (6) Systematic lipidomic analysis (for direct metabolic evidence) was lacking, though prior cadmium-exposed HepaRG studies36 identified relevant lipids.

Future work will address these by using primary hepatocytes, expanding sample sizes for rigorous quantification, staining toxin metabolism-related proteins/enzymes, comparing different antioxidants, including unaddressed lipid parameters, and integrating lipidomic analysis to clarify lipid metabolism mechanisms.

Methods

Construction and characterization of 3D HepG2 liver organoids46,47

Experimental materials

Cells: HepG2 cells (Wuhan Prosai, Cat. CL-0103), 6th passage (logarithmic phase). Plates: Corning® (USA) ultra-low adsorption U-shaped 96-well plates (polystyrene surface with covalently bonded hydrophilic neutral coating to reduce adhesion/coagulation, aiding cell aggregation). Medium: High-glucose DMEM + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin-streptomycin (1:1); sterilized, equilibrated to 37 °C before use. Cell preparation and organoid construction. Digestion: Confluent 6th-passage HepG2 cells rinsed twice with PBS; 0.25% (w/v) trypsin-EDTA added, incubated at 37 °C for 2–3 min until detachment. Termination and centrifugation: Equal-volume DMEM added to stop digestion; suspension centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min (RT). Resuspension and seeding: Supernatant aspirated; pellet resuspended in 30 mL pre-equilibrated medium (pipetted 5–6 times to 1 × 105 cells/mL); 200 μL/well seeded into ultra-low adsorption plates. Culture and Maintenance. Plates incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO₂ (humidified). Medium fully replaced every 48 h (old medium aspirated slowly; fresh pre-equilibrated medium added dropwise). Characterization. Morphology: Daily observation via Olympus (Japan) inverted phase-contrast microscope; images captured on Days 0, 3, 5, 7 (Fig. 3A). Fluorescence staining: Organoids fixed (4% paraformaldehyde), permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100), blocked (5% BSA); ALB stained with anti-ALB (1:200, Abcam) + Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500); ZO-1 stained with anti-ZO-1 (1:200, CST) + Alexa Fluor 594.

Construction and characterization of 3D HepG2 liver organ-on-a-chip

Hydrogel preparation: Mix 4.5 mg of fibrinogen into the hydrogel (Sigma-Aldrich) and set aside for later use. Cell seeding and culture: After digestion, HepG2 cells (6th generation, logarithmic growth phase; Wuhan Pricells, Cat. No. CL-0103) were resuspended in high-glucose DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Adjust the cell density to 1 × 106 cells/mL. Mix the cell suspension with the prepared hydrogel and inject it into the central channel of the chip, ensuring uniform distribution within the channel. Incubate statically at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 30 min to promote initial cell adhesion, then connect to the Suzhou Pengbo syringe pump system to initiate perfusion at a flow rate of 10 μL/h for simulating liver perfusion. Cell state characterization: Observe cell adhesion, pseudopod extension, and aggregation at 5- and 10-h post-seeding. Real-time monitoring was performed using the Jiangsu Ruiming live-cell monitoring system. Immunofluorescence staining: After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), incubate the samples with primary antibodies (anti-ALB, 1:200, Abcam; anti-ZO-1, 1:200, CST) followed by secondary antibodies (1:500, Alexa Fluor-conjugated). Acquire images using an Olympus confocal microscope (Fig. 2Cc). Metabolomic analysis: Collect the cell effluent, centrifuge the sample, and use the supernatant for metabolomic analysis.

Experimental grouping

Please see Table 3. The selection of cadmium doses in this study was determined based on a preliminary experiment. We first selected 30 μg/mL as the low dose, as it maintains approximately 80% cell viability, making it suitable for reflecting mild toxicity. The moderate dose (40 μg/mL) and high dose (50 μg/mL) were selected to induce moderate and severe cell lethal effects, respectively. Selenium doses were selected based on preliminary experiments, where concentrations ranging from 20 to 640 ng/mL showed no significant cytotoxicity; thus, 40, 160, and 640 ng/mL were chosen.

Cell culture and gel precursor preparation

Human liver cancer cells (HepG2 GFP, Shanghai Jinshaoyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). Cultures were maintained in a constant-temperature incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ and 95% humidity. GFP-HepG2 cells were propagated in DMEM medium until the sixth passage, reaching 80%-90% confluence. DPBS (Gibco, USA), DMEM medium, trypsin, and PBS were prewarmed to 37 °C for 30 min. Following established experimental protocols with slight modifications13, a 15 mg/mL fibrinogen solution was prepared. The solution was sterilized by positive-pressure filtration through a membrane at a controlled flow rate, which effectively trapped bacteria on the membrane surface. Thrombin (100 U, Sigma, USA) was removed from the 4 °C refrigerator and set aside for use.

Preparation of exposure solutions and biomarker assays

Exposure solutions of Cd, Se, t-BHP, and Vit C at varying concentrations were added to ultra-low adsorption U-shaped 96-well plates using DMEM high-glucose medium (PM150223, Wuhan Pronosai Life Sciences Technology Co., Ltd., China). Cd was prepared at three concentrations: 30, 40, and 50 μg/mL; Se at three concentrations: 40, 160, and 640 ng/mL. DMEM-t-BHP and DMEM-Vit C solutions were prepared concurrently, with final exposure concentrations of 700 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL, respectively. Plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere for 5 h. After incubation, samples were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the initial culture supernatant was collected.

Subsequently, levels of oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers, including ROS, 8-OHdG, γ-GCS, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, Casp-3, NF-κB, Nrf2, ALB, GSH, MDA, and LDH, were assayed48. Liver function biomarkers, such as TBA, ALT, and AST, were also measured49.

Cell viability assay

HepG2 cells were inoculated into T25 flasks and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Upon reaching the logarithmic growth phase (characterized by high viability), cells were counted using a hemocytometer (2 × 106 cells), digested with trypsin to form a single-cell suspension, and seeded into 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells/well in 100 μL volumes for adherence. After 24 h, the medium was removed, and varying concentrations of Cd (0–65 μg/mL) were added, with 6 replicates per concentration plus blank and control groups. Following 5 h of incubation, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added; absorbance at 450 nm was measured 2 h later. A similar CCK-8 assay was performed for Se (0–3560 ng/mL) after 24 h of incubation. The t-BHP concentration inducing 50% cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells was used for oxidative damage models. Additionally, the effects of t-BHP (0–1500 μg/mL) on cell survival were evaluated.

Immunofluorescence staining of HepG2 3D organoids and organs-on-a-chip

Liver organoids and liver organs-on-a-chip derived from HepG2 cells employ immunofluorescence triple staining targeting ZO-1, ALB, and nucleic acids46. Cells are first fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (40–60 min, room temperature [RT], shaking), then permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (30 min, RT). A blocking step follows with 5% BSA (1 h, RT) to reduce non-specific binding. Diluted primary antibodies, Affinity’s ZO-1 (1:200) and Proteintech’s ALB (1:1000), are added; these antibodies are from different species to avoid secondary antibody cross-reactivity, and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Next, fluorescent secondary antibodies (Affinity ZO-1, 1:300; Proteintech ALB, 1:500) incubate for 1–2 h (RT, dark). For nucleic acid staining, Sigma’s H 33342 is added and incubated for 1 h (RT, dark). Finally, cells are mounted with Beyotime’s anti-fluorescence quenching solution and imaged via fluorescence microscope or confocal laser microscopy (Olympus FV3000) to visualize targets through specific channels47.

Confocal imaging and quantitative morphometric analysis

The fluorescence imaging of microfluidic organs-on-a-chip was conducted using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus FV3000, Japan), equipped with excitation filters at wavelengths of 488 nm, 647 nm, and 409 nm. Place the liver organ-on-a-chip, stained with immunofluorescence, onto the stage of a confocal laser microscope (Olympus FV3000, Japan), ensuring that the organ-on-a-chip is securely fixed and positioned appropriately for observation. Power on the laser confocal microscope and carefully adjust the wavelength of the laser light source according to the characteristics of the dye on the organ-on-a-chip. Upon emission, the laser excites the dye, resulting in the production of a fluorescent signal. The microscope’s optical system collects these fluorescent signals, transmitting and focusing them through a series of optical pathways to generate clear fluorescent images. During the image acquisition process, parameters such as scanning resolution, scanning range, and scanning speed may be adjusted as needed to obtain high-quality, high-definition fluorescence image data suitable for research purposes50. These image data can subsequently be utilized for further analysis and investigation. The fluorescence image acquisition of microfluidic organ-on-a-chips was performed using a laser scanning confocal microscope, with excitation filters at 488 nm, 647 nm, and 409 nm (Olympus FV3000, Japan).

Untargeted metabolomics analysis of the microfluidic effluent of livers-on-a-chip

Process the liver organ-on-a-chip effluent (microfluidic effluent) using standard methods on the effluent samples, followed by analysis utilizing LC-MS technology51,52. The pretreatment of the original data obtained from liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) was conducted using Progenesis QI software, developed by Waters Corporation in Milford, United States. Following pretreatment, the data were exported into a three-dimensional data matrix in CSV format, encapsulating sample information, metabolite names, and mass spectrometry response intensities. Subsequently, the data matrix underwent cleaning and optimization processes. Internal standard peaks and various known false positive peaks-such as those resulting from noise, column bleeding, and derivatization reagents-were eliminated, while de-redundancy and peak merging operations were performed concurrently. During the metabolite identification phase, multiple prominent databases were queried, including the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, website: http://www.hmdb.ca/), the Metlin Database (https://metlin.scripps.edu/), and the Majorbio Database, to ensure accurate metabolite identification. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using the free cloud platform cloud.majorbio.com. Metabolic features that were present in at least 80% of any sample set were retained. After preliminary filtering, for specific samples with metabolite levels below the lower limit of quantification, the minimum metabolite values were employed to fill in the missing data; all metabolic features were adjusted using the sum normalization method. The pretreatment of the original data obtained from liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) was conducted using Progenesis QI software developed by Waters Corporation in Milford, United States. Following pretreatment, the data were exported into a three-dimensional data matrix in CSV format, which included sample information, metabolite names, and mass spectrometry response intensities. This data matrix then underwent a cleaning and optimization process. Internal standard peaks and various known false positive peaks-such as those resulting from noise, column bleeding, and derivatization reagents-were removed, while de-redundancy and peak merging operations were performed simultaneously. During the metabolite identification phase, several prominent databases were consulted, including the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, available at http://www.hmdb.ca/), the Metlin Database (https://metlin.scripps.edu/), and the Majorbio Database, to ensure accurate metabolite identification. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using the free cloud platform cloud.majorbio.com. Metabolic features present in at least 80% of the samples in any given set were retained. After preliminary filtering, for specific samples with metabolite levels falling below the lower limit of quantification, the minimum metabolite values were utilized to fill in the gaps, and all metabolic features were adjusted using the sum normalization method.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected from six replicates and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0, and data visualization was conducted with GraphPad Prism 9.0. Statistical significance was assessed via one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni test: (1) Compared with the CK group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; (2) VitC + Cd40 μg/mL group or VitC + t-BHP group compared with the VitC group. #: p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01; (3) Se 40 ng/mL + Cd40 μg/mL group compared with the Cd40 μg/mL group. &:p < 0.05, &:&p < 0.01.

Metabolomics data were processed on the online software platform MetaboAnalyst (https://dev.metaboanalyst.ca/home.xhtml). Based on the OPLS-DA model and Student’s t-test, the screening threshold was set as variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1 and P < 0.05. Additionally, metabolomics data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and the least significant difference test, with the statistical significance threshold maintained at p < 0.05.

Data availability

Data will be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Li, Y. et al. Achieving synergistic benefits through integrated governance of cultivated cadmium contamination via multistakeholder collaboration. Nat. Commun. 15, 9817 (2024).

Yin, X. Y. et al. Study on toxicological effect and the mechanism of cadmium in rice and inorganic cadmium on ICR mice. Toxicol. Res. 10, 639–650 (2021).

Li, M. L. et al. Effects of selenium and cadmium on human liver and kidney functions in exposed black shale areas. Geohealth 8, e2024GH001040 (2024).

Li, M. L. et al. Do high soil geochemical backgrounds of selenium and associated heavy metals affect human hepatic and renal health? Evidence from Enshi County, China. Sci. Total Environ. 883, 163717 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Protective effects and mechanism of chemical- and plant-based selenocystine against cadmium-induced liver damage. J. Hazard. Mater. 468, 133812 (2024).

Zwolak, I. The role of selenium in arsenic and cadmium toxicity: an updated review of scientific literature. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 193, 44–63 (2020).

Liu, K. et al. From organoids to organoids-on-a-chip: current applications and challenges in biomedical research. Chin. Med. J. 138, 792–807 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Global trends of organoid and organ-on-a-chip in the past decade: a bibliometric and comparative study. Tissue Eng. Part A 26, 656–671 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Advanced strategies in organoid/organ-on-a-chip for food safety and nutrition. Food Res. Int. 219, 117011 (2025).

Akhtar, A. A. et al. Organoid and organ-on-a-chip systems: new paradigms for modeling neurological and gastrointestinal disease. Curr. Stem Cell Rep. 3, 98–111 (2017).

Prince, E. et al. Biomimetic hydrogel supports initiation and growth of patient-derived breast tumor organoids. Nat. Commun. 13, 1466 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Systematic evaluation of colorectal cancer organoid system by single-cell RNA-Seq analysis. Genome Biol. 23, 106 (2022). 2022.

Li, Y. et al. Study of the neurotoxicity of indoor airborne nanoparticles based on a 3D human blood-brain barrier chip. Environ. Int. 143, 105598 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Atmospheric nanoparticles affect vascular function using a 3D human vascularized organotypic chip. Nanoscale 11, 15537–15549 (2019).

Feng, Q. et al. Antioxidant activity of Osmanthus fragrans extract and its protection effects on t-BHP-induced oxidative damage of HepG2 cells. Chem. Bioeng. 42, 53–58 (2025).

Liu, T. et al. A study on the time-effect and dose-effect relationships of polysaccharide from Opuntia dillenii against cadmium-induced liver injury in mice. Foods 11, 1340 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Effects of the gut microbiota and barrier function on melatonin efficacy in alleviating liver injury. Antioxidants 11, 1727 (2022).

Cao, Z. Y. et al. Selenium antagonizes cadmium-induced inflammation and oxidative stress via suppressing the interplay between NLRP3 inflammasome and HMGB1/NF-κB pathway in duck hepatocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6252 (2022).

Yang, Y. Q. et al. Triptriolide alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury by Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 999 (2018).

Vinceti, M. et al. Adverse health effects of selenium in humans. Rev. Environ. Health 16, 233–251 (2001).

Flores, K. M. et al. Hepatocytes display a compensatory survival response against cadmium toxicity by a mechanism mediated by EGFR and Src. Toxicol. In Vitro 27, 1031–1042 (2013).

Xu, Y. et al. α-Lipoic acid protects against the oxidative stress and cytotoxicity induced by cadmium in HepG2 cells through regenerating glutathione regulated by glutamate-cysteine ligase. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 25, 596–603 (2015).

Muranyi, W. et al. Immortalized human choroid plexus endothelial cells enable an advanced endothelial-epithelial two-cell type in vitro model of the choroid plexus. iScience 25, 104383 (2022).

Ye, Y. J. et al. Luteolin inhibits GPVI-mediated platelet activation, oxidative stress, and thrombosis. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1255069 (2023).

Kim, J. H. & Kim, I. H. Arsenic compounds arsenic trioxide and tetraarsenic oxide attenuate 3-methylcholanthrene-induced cytotoxicity in human keratinocytes. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 85, 1147 (2023).

To, K. K. W. et al. Utilizing non-coding RNA-mediated regulation of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters to overcome multidrug resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Drug Resist. Updates 73, 101058 (2024).

Chedik et al. Interactions of organophosphorus pesticides with ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporters. Xenobiotica 52, 644–652 (2022).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Mitigation of membrane biofouling by d-amino acids: effect of bacterial cell-wall property and d-amino acid type. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 164, 20–26 (2018).

Zhu, M. et al. Bile acid metabolic profiles and their correlation with intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and barrier integrity in suckling piglets. Animals 14, 287 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Genome-wide identification, comparative analysis and functional roles in flavonoid biosynthesis of cytochrome P450 superfamily in pear (Pyrus spp.). BMC Genom. Data 24, 58 (2023).

Omale, J. A. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acid oil extract on acute inflammation in animal models. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1761276/v1 (2022).

Migni, A. et al. Melatonin as a repairing agent in cadmium- and free fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Biomolecules 13, 1758 (2023).

Pannico, A. et al. Selenium biofortification impacts the nutritive value, polyphenolic content, and bioactive constitution of variable microgreens genotypes. Antioxidants 9, 272 (2020).

Lafin, J. T. et al. Methylseleninic acid induces lipid peroxidation and radiation sensitivity in head and neck cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 225 (2019).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. Phytohormones enhance heavy metal responses in Euglena gracilis: evidence from uptake of Ni, Pb and Cd and linkages to hormonomic and metabolomic dynamics. Environ. Pollut. 320, 121094 (2023).

Migni, A. et al. Melatonin repairs the lipidome of human hepatocytes exposed to Cd and free fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. J. Pineal Res. 77, e70047 (2025).

Cao, X. Y. et al. Cadmium induced BEAS-2B cells apoptosis and mitochondria damage via MAPK signaling pathway. Chemosphere 263, 128346 (2021).

Chen, J. R. et al. Enhancing organic selenium content and antioxidant activities of soy sauce using nano-selenium during soybean soaking. Front. Nutr. 9, 970206. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.970206 (2022).

Refaie, M. M. M., El-Hussieny, M. & Zenhom, N. M. Protective role of nebivolol in cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity via downregulation of oxidative stress, apoptosis and inflammatory pathways. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 58, 212–219 (2018).

Tanaka-Yachi, R. et al. Low-density cell culture enhances hepatic function through tight junction formation in HepG2 cells. Biol. Cell 114, 225–236 (2022).

Kitano, H., Kawabe, Y. & Kamihira, M. HepG2-based designer cells with heat-inducible enhanced liver functions. Cells 11, 1194 (2022).

Ruoß, M. et al. Epigenetic modifications of the liver tumor cell line HepG2 increase their drug metabolic capacity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 347 (2019).

Tomsuk, Ö et al. Effects of essential oil of Origanum onites and its major component carvacrol on the expression of toxicity pathway genes in HepG2 cells. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 24, 265 (2024).

Keuter, L. et al. Alterations in the proteomes of HepG2 and IHKE cells inflicted by six selected mycotoxins. Arch. Toxicol. 99, 701–715 (2025).

Feng, Q. et al. Protective effect of Osmanthus water extract on liver dysfunction caused by DBP based on organoids and organ chips technologies. Food Res. Int. 219, 116976 (2025).

He, Y. T. et al. Creating rat hepatocyte organoid as an in vitro model for drug testing. World J. Stem Cells 12, 1184–1195 (2020).

Xu, M. M. et al. Cell-free fat extract prevents tail suspension-induced bone loss by inhibiting osteocyte apoptosis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 818572 (2022).

Hu, W. B. et al. Specific strains of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii ameliorate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice in association with gut microbiota regulation. Nutrients 14, 2945 (2022).

Albrahim, T. & Alonazi, M. Effect of blueberry extract on liver in aged rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 3490776 (2022).

Giráldez-Pérez, R. M. et al. Biocompatible DNA/5-fluorouracil-gemini surfactant-functionalized gold nanoparticles as promising vectors in lung cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics 13, 423 (2021).

Lu, S. R. et al. Mechanisms underlying Th2-dominant pneumonia caused by plastic pollution derivatives: a molecular toxicology investigation that encompasses gut microbiomics and lung metabolomics. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 136326 (2024).

Wei, H. Q. et al. Mechanisms of exacerbation of Th2-mediated eosinophilic allergic asthma induced by plastic pollution derivatives (PPD): a molecular toxicological study involving lung cell ferroptosis and metabolomics. Sci. Total Environ. 946, 174482 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42177416, 42477452), the Key Special Project for Social Development R&D of Xianning City Science and Technology Program(2021SFYF007), Health Commission of Hubei Province scientific research project (WJ2021Z006), and Scientific Research Innovative Team of Hubei University of Science and Technology (2023T08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. performed the cell experiments, analyzed the data, created the figures, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the final version. Q.F. executed the cell experiments, analyzed the data, and produced the figures. L.S. conducted the study, conceived and designed the research experiments, and also revised the manuscript. S.L. contributed to data analysis and figure creation. Z.R. supervised the data analysis and provided revisions for the manuscript. B.Y. also supervised the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. W.X., Q.D., X.-Y.Y., C.Y., Y.W., and S.H. reviewed and revised the manuscript. Additionally, X.Y. conducted the study, conceived and designed the research experiments, analyzed the data, created the figures, and revised the manuscript. Finally, L.S. supervised the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript, while P.M. conducted the study, conceived and designed the research experiments, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, M., Feng, Q., Lu, S. et al. Application of HepG2-derived organoid and organ-on-a-chip platforms in elucidating selenium-mediated protection against cadmium-induced liver dysfunction. npj Sci Food 10, 22 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00669-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00669-4