Abstract

Circadian clocks orchestrate behavior, physiology, and metabolism in harmony with the Earth’s 24-h cycle. Low temperatures are known to disrupt circadian clocks in plants and poikilotherms; however, their effects on human circadian rhythms remain poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that cold exposure abolishes the circadian rhythm in cultured human cells through diminishing the oscillation amplitude, which was restored upon rewarming. In addition, the oscillation amplitude of the 24-h temperature cycles was enhanced through resonance, reflecting the intrinsic frequency of the circadian clock. From a theoretical perspective, these dynamics correspond to Hopf bifurcation, which is confirmed by a mathematical model for the mammalian circadian clock. In contrast, the circadian amplitude of human hair follicle cells was not significantly sensitive to temperature changes. These observations suggest a potential evolutionary advantage of maintaining Hopf bifurcation despite robust homeostasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temperature is a major environmental factor that regulates an endogenous oscillation with a period of approximately 24 hours, i.e., circadian rhythm1,2. The period of the circadian rhythm remains robust under different temperature conditions, a phenomenon known as temperature compensation, a prominent property of the circadian rhythm. Experimentally, it has been reported that temperature compensation involves some temperature-insensitive biochemical reactions3,4,5 as well as temperature-dependent degradation rates of clock proteins6,7,8. Theoretical studies proposed that a switch-like resetting mechanism9, and changes in amplitude-such as those caused by depletion of reactant molecules at higher temperatures are a key factor underlying temperature compensation10,11.

Another universal phenomenon related to temperature and circadian rhythm is the loss of rhythmicity in plants and poikilotherms under low-temperature conditions. This nullification of circadian rhythm, documented in species ranging from dinoflagellates and fungi to insects and higher plants, consistently occurs when temperatures fall below a species-specific critical temperature threshold12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In contrast, circadian rhythms in homeothermic animals under low-temperature conditions are reported far less frequently. A few studies have addressed mammalian circadian rhythms in the absence of body temperature homeostasis. One notable area of research focuses on circadian rhythms in hibernating rodents. The core body temperature of a hamster, including the brain, approaches 5 °C during hibernation. During this state, circadian rhythms of gene expression within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) are abolished20,21. More recent studies using calcium live imaging have demonstrated that circadian rhythms in SCN neurons disappear at 15 °C22.

The loss of self-sustained oscillation, such as the nullification of circadian rhythm under low temperature conditions, can be regarded as a qualitative change in a dynamical system. Dynamical system theories provide mathematical scenarios that occur due to changes in parameter values, a phenomenon referred to as bifurcation23. Thus, one can expect that bifurcation underlies the arrhythmicity induced by low-temperature conditions. According to bifurcation theory, two typical scenarios can explain the loss of rhythmicity: Hopf bifurcation and saddle-node on an invariant circle (SNIC) bifurcation (Fig. 1). In Hopf bifurcation, the oscillation amplitude gradually diminishes until it eventually reaches zero, and a self-sustained oscillator transforms into a damped oscillator. In SNIC bifurcation, oscillations are arrested at a specific phase, where the system transitions from a self-sustained oscillation to an excitable system. During this process, the period extends to infinity, while the amplitude remains almost constant. Another useful aspect of bifurcation theory is that it provides predictions about system behavior near the critical temperature. For example, the KaiC phosphorylation rhythm of the cyanobacterial circadian clock loses rhythmicity at 19 °C through a Hopf bifurcation24. As predicted by the theory of Hopf bifurcations, the system exhibits damped oscillations at low temperatures, and the amplitude of these damped oscillations can be amplified through resonance with periodic environmental changes. Similarly, oscillations of neuronal membrane potential can transition into a resting state via a SNIC bifurcation25. One can expect this resting state to show excitability, according to the theory of SNIC bifurcations. This same principle is exemplified by the gene expression oscillator in C. elegans larvae, which operates near a SNIC bifurcation, allowing it to arrest in a specific phase and potentially function as a developmental checkpoint26.

The loss of self-sustained circadian rhythms under low temperatures can be explained by two mathematical scenarios. Around the critical temperature, the oscillator behaves differently under the different bifurcations. In Hopf bifurcation, the oscillation amplitude decreases to zero while the period remains relatively stable. In addition, the self-sustained oscillator turns into a damped oscillator at the critical point. Meanwhile, in SNIC bifurcation, the oscillation period extends and eventually diverges to infinity. The self-sustained oscillation can be transformed into an excitable system at the bifurcation point.

Despite the effectiveness of bifurcation theory in explaining low-temperature-induced arrhythmia, it has not been investigated in other than cyanobacteria24. Specifically, the question of whether the types of bifurcation are conserved across species-spanning both endotherms and ectotherms such as temperature compensation, should provide valuable insights when considering the evolutionary drivers of biological clocks.

In this study, we focused on the loss of circadian rhythmicity in cultured human cells under low-temperature conditions and analyzed the qualitative transitions of the circadian clock using bifurcation theory. Furthermore, we examined human hair follicle cells to investigate the temperature dependence of peripheral circadian clocks in homeothermic organisms under low-temperature conditions. Through these investigations, we explored the universal dynamics governing circadian rhythms under low-temperature conditions and their evolutionary implications.

Results

Reduced circadian amplitude of cultured human cells under low temperatures

To determine the bifurcation type involved in the loss of self-sustained oscillations, a detailed analysis of the period and amplitude near the bifurcation point is required. Thus, we cultured U2OS cells expressing the BMAL1-dLuc reporter in wells with a controlled temperature gradient and monitored the bioluminescence patterns across a temperature range from 25 °C to 37 °C (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1). The oscillatory rhythms became undetectable at approximately 30 °C (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 1D). Since cell viability remained high throughout the 25–37 °C range (Supplementary Fig. 1E), we can exclude the possibility that amplitude reduction resulted from impaired cell viability at lower temperatures. As the temperature decreased, the oscillation amplitude of the bioluminescence rhythm progressively diminished, while the oscillation period did not significantly change. This temperature-dependent reduction in amplitude, coupled with the stability of the period near the point where the rhythm disappeared, suggests that the loss of circadian rhythmicity under low-temperature conditions is governed by Hopf bifurcation.

A Bioluminescence rhythm of U2OS BMAL1-dLuc cells at low-temperature conditions. B Amplitude (black) and period (red) of the bioluminescence rhythm under different temperatures. The period at each fixed temperature is presented as the mean ± SD of multiple peak-to-peak intervals within a single experiment. C Recovery from cold-induced arrhythmia. U2OS cells were incubated at 22 °C, 24 °C or 26 °C for 48 h and then transferred to 36 °C.

Recovery from cold-induced arrhythmia with a different phase

When plants or poikilotherms lose circadian rhythmicity under low temperatures and resume the rhythm upon rewarming, the rhythms tend to start from circadian time (CT) 12, the beginning of the subjective night13,27. To investigate whether a similar phenomenon occurs in human cells, we exposed U2OS cells to low temperatures (22–26 °C), followed by a rewarming to 36 °C. Consistent with observations in plants and poikilotherms, rewarming to 36 °C restored the circadian rhythm of BMAL1 oscillations (Fig. 2C).

In addition, we estimated the phase of the BMAL1 rhythm upon resumption based on its phase after rewarming to 36 °C. Consistent with prior studies28,29, we defined CT22 as the phase value corresponding to the peak of BMAL1 expression rhythm and estimated the phase at which the rhythm restarted based on CT22 - 24 t/τ, where t represents the time of the first peak after rewarming, and τ is the free-running period at 36 °C. Accordingly, we estimated that oscillations began at CTs 12.38, 13.08, and 14.76 for initial temperatures of 22, 24, and 26 °C, respectively. Notably, the phase of the oscillation rhythm after rewarming to 36 °C was not fixed at a specific phase but instead depended on the combination of temperatures. This phenomenon can be attributed to the temperature-dependent position of the stable fixed point created by Hopf bifurcation, rather than by SNIC bifurcation (Supplementary Fig. 2A and 2B).

Resonance of damped oscillation in response to temperature cycles

According to Hopf bifurcation theory, the bifurcation can transform a self-sustained oscillator into a damped oscillator at a critical point23. If exposure to low temperature induces Hopf bifurcation in the cellular clock, one can expect resonance of the circadian clock dampened by low temperature, which is analogous to the enhancement of the pendulum’s amplitude by an optimal periodic force. In cyanobacteria, the phosphorylation rhythm of reconstituted KaiC is transformed into a damped oscillator under low temperature conditions, and temperature cycles with an optimal period can restore the amplitude of the damped oscillation24. Similarly, a damped bioluminescence rhythm is observed in kaiA deletion mutants of cyanobacteria, which resonate with external cycles with a period of 24-26 h30.

Thus, we applied periodic 1-hour temperature pulses to U2OS cells maintained at 30 °C, a temperature near the bifurcation point (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 3). The amplitude of the forced oscillation depended on period of the cyclic pulses: it peaked under a 24-hour cycle for 1-hour pulses (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 3C). Additionally, it also peaked under an 18-hour cycle for 3-hour pulses (Supplementary Fig. 3D). We hypothesize that the enhanced amplitude might be related to the proportion of time occupied by the temperature pulse. This shift indicates that the cold-induced damped oscillation exhibits resonance, with a resonant period close to 24 hours. This observation is consistent with the property that Hopf bifurcation tends to preserve the intrinsic oscillation period.

A Bioluminescence rhythms of cultured U2OS BMAL1-dLuc reporter cells were subjected by periodic 1-h 37 °C pulses, administered at intervals of T = 18, 24, or 30 hours against a constant 30 °C (H: 37 °C; L: 30 °C). B The amplitude of forced bioluminescence oscillations under periodic temperature pulses. Amplitude was quantified using the SD on time-course data after 2T under 30 °C. The blue baseline indicates the amplitude at constant 30 °C conditions.

Preference for Hopf bifurcation in the mathematical model

To explore the underlying molecular mechanisms for Hopf bifurcation, we focused on the Kim–Forger model, which describes the dynamics of the detailed molecular network of the mammalian clock31. This comprehensive model incorporates 70 parameters and 180 variables, integrating both positive and negative feedback loops. To investigate the effect of temperature on the dynamics of this model, we assumed that some of the rate constants become smaller as the temperature decreases, i.e., we randomly assigned some parameters in the model as temperature-dependent. The reduction of the parameter value due to low temperature was parameterized by a factor α, which ranged between 0 and 1. We assumed that lowering the temperature can update the parameter value according to \({k}^{{\prime} }=\alpha k\), where k and \({k}^{{\prime} }\) represent the value of the temperature-dependent rate constant under normal and chilling conditions, respectively. We quantified the effect of the reduction of the parameter value on the amplitude and period of Bmals mRNA in the nucleus, which was representative of the mammalian circadian clock dynamics. We classified the type of bifurcation based on the transition of oscillation amplitude and period around the critical point of rhythm disappearance (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

To investigate which type of bifurcation is more likely to occur when reducing parameter values, we randomly selected n temperature-dependent parameters 100 times and examined the types of bifurcation that emerged as factor α decreased. Hopf bifurcations were frequently observed across a wide range of n values. In contrast, SNIC bifurcations occurred with a lower probability compared to Hopf bifurcations (Fig. 4A). This preference for Hopf bifurcations was reproduced in the Goodwin model32, which describes a simple transcriptional negative feedback loop (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, resonance behavior was confirmed in both the Kim-Forger and Goodwin models (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 7). Taken together, these simulation results align with our experimental findings and further suggest that biological oscillators based on a negative feedback loop have a tendency to generate Hopf bifurcations.

A Preference of Hopf bifurcation of Kim–Forger model. To classify the type of bifurcation, nuclear Bmals expression was selected as a representative marker of circadian dynamics. We hypothesized that some of the 70 parameters of the Kim–Forger model depend on temperature. The probability of bifurcation type depending on the number of temperature-dependent parameters n is displayed. B Resonance of the Kim-Forger model under temperature cycles. We periodically altered the value of 10 distinct parameters (index #: 20, 56, 32, 2, 8, 64, 10, 21, 48, 53; see Supplementary Table 1) via switching the value of α between 1 (normal temp.) and 0.4 (below critical temp.).

Circadian amplitude of human hair follicles across ambient temperatures

While we have investigated the effect of temperature on cultured human cells, the temperature effect on the individual level is more complex. In particular, the temperature dependency of cellular rhythms in the human body remains poorly understood. To address this gap, we investigated circadian rhythms of hair follicle cells in human subjects isolated in a temperature-controlled room. The advantages of hair follicle cells are that the expression level of the follicle cells can be measured non-invasively33 and the shallowness of follicle cells in the scalp skin suggests possible dependence on environmental temperature.

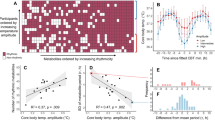

As a preliminary experiment, we examined the expression of nine clock genes in hair follicle cells at three time points (Supplementary Fig. 8). We extracted the amplitudes and phases from these time courses and selected four high-amplitude genes. In the subsequent main experiment, we focused on the expression of these selected genes together with the Cry1 gene, which is known to exhibit temperature-dependent amplitude regulation11. Hair follicle cells were collected every 6 h from six participants who stayed in a temperature-controlled chamber maintained at either 28 °C or 18 °C (Fig. 5A). Upon cosinor analysis, a circadian rhythm in scalp temperature was detected at 28 °C, with the most pronounced rhythm observed at 18 °C (Fig. 5B), consistent with prior studies34,35. As expected, the mean scalp temperature varied with ambient temperature. Notably, the timing of the temperature trough was delayed under cooler conditions.

A Hair follicle collection procedure. Six participants arrived at the experimental facility at 19:00 and were dressed in experimental clothes after receiving brief instructions for the experiment. The participants stayed in the isolated temperature-controlled chamber (28 °C and 18 °C) until the end of the experiment. Ten hair follicles were collected from participants at 22:00, 4:00, 10:00, 16:00, and 22:00. The hair follicle samples were immediately soaked in RNAlater and stored at −70 °C until RNA analysis. B Scalp skin temperature under different chamber temperatures. Each participant’s scalp skin temperature was measured three times at one-minute intervals. The value is presented as the mean ± SD. C Expression profiles of the circadian clock gene under different temperatures. The error bars indicate the SD of three repeated measurements by real-time qPCR. D Circadian amplitude of gene expression profiles under different temperatures. Each dot represents the circadian amplitude of hair follicle cells from an individual participant, shown as the SD. Gray lines connect the amplitudes of the same participant under different temperature conditions.

We quantified mRNA expression levels of key circadian regulators (NR1D1, PER3, BMAL1, CLOCK, and CRY1) in human hair follicles under 28 °C and 18 °C (Fig. 5C). The amplitude of these expression profiles revealed no statistically significant differences between different temperature conditions (Fig. 5D), demonstrating that the circadian amplitude of hair follicles in the human body maintained thermal stability.

We further investigated the circadian amplitude of ex vivo cultured human hair follicles under different temperature conditions (Supplementary Fig. 9A). The amplitudes of the expression profile of PER3 and CLOCK were enhanced at 36 °C compared with that of 26 °C. Conversely, the amplitudes of BMAL1 and NR1D1 were smaller at 36 °C than at 26 °C (Supplementary Fig. 9B), suggesting different temperature dependency in the amplitude compared to cultured U2OS cells. These observations imply that the circadian amplitude of ex vivo cultured human hair follicles is more sensitive to ambient temperature changes than those in in vivo conditions, and they exhibit different sensitivities between clock genes.

Discussion

We demonstrated that low temperature diminished the oscillation amplitude of circadian rhythms in cultured human cells, suggesting that Hopf bifurcation underlies the loss of rhythmicity. In addition, the resonance of the 24-h temperature cycle resulting in the enhancement of the circadian amplitude supports the involvement of Hopf bifurcation. Considering the phosphorylation rhythm of cyanobacterial KaiC24, these observations imply that two distinct clock mechanisms exhibited low-temperature-induced Hopf bifurcation. In Hopf bifurcation, the oscillation period remains relatively constant near the bifurcation point, whereas significant period slowing is observed in SNIC bifurcation. Given that compensation across a wide range of temperatures is a critical adaptive feature of circadian rhythms, it is plausible that the circadian system prefers Hopf bifurcation. These observations suggest Hopf bifurcation is a universal property along with temperature compensation and entrainment to environmental cycles.

Bioluminescence assays driven by luciferase reporter genes have been widely used as a standard approach for monitoring circadian rhythms36,37. Our bifurcation analysis was also based on bioluminescence measurements. However, since bioluminescence is the outcome of an enzymatic reaction, it is expected that the thermal stability of the enzyme, as well as the temperature dependence of the intracellular environment, influence the light output. In particular, because luciferase is more stable at temperatures below body temperature38, the intensity of bioluminescence at lower temperatures may have been overestimated. Such an overestimation of amplitude under low-temperature conditions may affect the determination of the circadian critical temperature that we estimated; nevertheless, it is unlikely to alter the scenario in which oscillations disappear at low temperatures via amplitude reduction through a Hopf bifurcation. The development of accurate and reliable tools for amplitude measurement using fluorescence22 will further strengthen our conclusion.

The Kim–Forger and Goodwin models confirmed the preference for Hopf bifurcation (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 6). The vulnerability of amplitude and robustness of period in this model can be observed even far from the bifurcation point11, which suggests the association between temperature compensation and Hopf bifurcation. Moreover, because these models comprise a negative feedback loop, temperature compensation and Hopf bifurcations may naturally arise as inherent properties associated with such a feedback loop.

While the qualitative loss of rhythmicity can be conserved across species, the critical temperature is not generally conserved quantitatively at certain levels. For example, we showed that the critical temperature of U2OS cells was approximately 30 °C (Fig. 2B), however, circadian oscillations in rat-1 fibroblasts persist under 28 °C39. Even wider divergence is observed in whole organisms and tissue slices: mouse SCN neuron slices maintain circadian rhythms down to about 15 °C22. The circadian rhythm in hibernating ground squirrels and bats continues to function at body temperatures around 10 °C40,41. Hibernating European hamsters do not show circadian oscillations when the core body temperature drops to near-ambient temperature (~5 °C)21. These observations suggest that the critical temperature depends on levels of the organization, i.e., cellular, tissue, or organismal level. Such diversity in critical temperatures may stem from the variability in the amplitude of circadian clocks. A larger amplitude would likely result in a lower critical temperature. Moreover, it is known that some clock genes are involved in determining the amplitude of the circadian clock42,43,44.

Resonance to temperature cycles with an optimal frequency enhanced the circadian amplitude of cultured human cells (Fig. 3). Resonance can transfer energy between oscillators, which provides an energetic advantage for biochemical oscillations45,46. Therefore, one can expect physiological merits for resonating with environmental frequency. Plants and cyanobacteria under light-dark cycles with periods close to the endogenous circadian rhythm exhibit enhanced growth47,48,49. Conversely, deviations to the innate 24-h circadian period in non-human primates and rodents resulted in reduced lifespans50,51,52. These connections between the environmental period and physiological advantage can be explained by the enhancement of amplitude by resonance. Winter coldness can severely reduce circadian amplitude in plants or poikilotherms13,24,53. However, resonance could recover this reduction of oscillation amplitude. Moreover, resonance to temperature cycles may function in homeothermic animals. The circadian clock in mammals rhythmically regulates body temperature. The resulting body temperature rhythm, in turn, is expected to enhance the circadian clock’s amplitude through resonance. This interaction between the circadian clock and body temperature rhythm via resonance may be one of the evolutionary reasons why peripheral clocks in homeothermic animals exhibit temperature sensitivity.

From a more microscopic view, the causes of amplitude reduction near a Hopf bifurcation are generally classified into two cases: amplitude reduction of individual oscillators or desynchronization, i.e., loss of rhythmicity in cultured cells caused by desynchronization between cells, or a decrease in amplitude in each cell. Decreased oscillation amplitude in individual SCN neurons at low temperature suggests oscillation death in each cell22. However, further single-cell observation around critical temperature is needed to elucidate the cause of Hopf bifurcation54.

We demonstrated that an ambient temperature of 18 °C reduced scalp skin temperature yet did not affect the amplitude of clock gene expression in hair follicle cells (Fig. 5). This suggests that the follicle cells, located in the dermal layer of the skin and influenced by blood flow55, can be maintained under relatively stable temperature conditions regardless of ambient temperature. The actual temperature measurements on or within the scalp are consistent with this suggestion56. In contrast, the circadian amplitude in ex vivo cultured hair follicle cells was more sensitive to external temperature fluctuations (Supplementary Fig. 9B). This suggests that isolated cells lack the integrative mechanisms required to buffer against environmental temperature changes. Temperature homeostasis in humans should contribute to maintaining the amplitude of peripheral clocks in the whole body by resisting the temperature dependence of circadian amplitude. While our data show no statistically significant difference in circadian amplitude between 18 °C and 28 °C, we cannot rule out subtle effects. Furthermore, the more direct method for measuring the temperature of in vivo follicles would reveal a precise correlation between ambient temperature and circadian dynamics.

Methods

Collection of human hair follicle cells from the scalp

Six healthy participants (three male and three female university students) were chosen for this experiment. The participants ranged in age from 22 to 32 years. The Kyushu University Institutional Review Board for Human Genome/Gene Research approved this study protocol (approval number: 548-08), and all procedures were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. After describing the experimental procedure to experimental participants, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to enrollment57.

All participants stayed in a homotoro chamber (temperature-controlled room) for one day. The room was set to a high temperature of 28 °C or a low temperature of 18 °C. A temperature detector was used to measure their scalp skin temperature. Before the experiment, all participants were asked to follow a sleep-wake schedule between 23:00 and 07:00 for at least one week. Each participant wore an Actiwatch Fitbit Charge 5 during the study period. An actigraph was used to confirm whether they followed the schedule. The participants were not allowed to consume excessive alcohol, snacks, or caffeine before the experiment. Ten scalp hair follicles were collected from each subject by holding and pulling hair with a pair of tweezers. The hair shafts largely covered with follicle cells were quickly immersed in RNAlaterTM Stabilization Solution (AM7020, Thermo Fisher Scientific, U.S.A) and stored below −70 °C until RNA purification.

Cell culture of U2OS carrying BMAL1 luciferase promoter

Human U2OS cells were provided by Dr. Takashi Yoshimura58. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; 3090869, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, FB-1290/500; Biosera, France), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Pen Strep, 15070-063, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for several days at 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2.

Real-time monitoring of BMAL1-dLuc oscillations in U2OS cells

When U2OS cells reached confluence, they were further incubated in serum-free DMEM for 24 h and then synchronized using 100 nM dexamethasone (Dex, Sigma-Aldrich). After 2 h of treatment with Dex, the culture medium was replaced with complete DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution, and the dish was placed in a photomultiplier tube (PMT) under different temperatures. Luciferase activity was monitored using a real-time PMT. The data are presented as counts per minute, calculated at 10-min intervals. A baseline correction was calculated using a 24-h moving average, which removed the first 12 h of data, as previously described59.

Measurement of amplitude and period for bioluminescence

The amplitude was examined by standard deviation (SD), and the period was determined using peak-to-peak fluctuations. We calculated the SD of all detrended data of bioluminescence as circadian amplitude. The period was determined based on the difference between peaks using the scipy.signal.find_peaks function in the Python3 module.

Temperature-gradient apparatus

Two heating baths (UT40U100F; Ampere) were connected by an aluminum block insulated with a heat-resistant material24. By adjusting the temperature of the heating baths, a precise temperature gradient was established with an accuracy of ± 0.1 °C.

Isolation of total RNA, reverse transcription PCR, and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from human hair follicles using the RNAqueous-Micro Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, U.S.A). The cDNA sample was generated by using SuperScriptTM IV VILOTM Master Mix. The primer sets used for real-time quantitative PCR are based on a previous study60. Briefly, qPCR was performed in a 20 μL reaction volume containing TB Green premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus), primers, template, and sterile purified water using the CFX96 Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), according to a previously described method59. All reactions were performed in triplicate and displayed amplification efficiencies between 80% and 120%. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to quantify gene expression. In addition, GAPDH was used as an internal reference to normalize the relative expression of each sample.

Numerical analysis of the mammalian clock model

Kim–Forger model was numerically solved using the MATLAB code provided by the authors31. To determine the type of bifurcation, we chose the concentration of Bmals in the nucleus as a representative variable of circadian dynamics. We hypothesized that some of the 70 parameters of the Kim–Forger model depend on temperature, i.e., \({k}^{{\prime} }=\alpha k\) where k represents the value of a temperature-dependent parameter and α ∈ [0, 1] is a temperature-dependent factor, with 1 corresponding to high temperature and 0 to low temperature. We adopted the value of the rate constants described in the original paper31. In addition, we calculated the probability of bifurcation by randomly selecting temperature-dependent parameters (Fig. 4A). Details of the formula in the Kim–Forger model and the determination of the type of bifurcation are provided in the Supplemental information.

Ex-vivo culture of human hair follicles

Hair follicles were cultured as described61,62. Briefly, intact scalp hairs with roots fully covered by follicle cells were plucked and immersed in pre-warmed complete DMEM medium. Cultures were maintained at either 36 °C or 26 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Following a 2 h synchronization with Dex, the hair follicle samples were collected every 6 h from 36 h to 60 h for RNA extraction.

Cell viability assay by trypan blue exclusion

Cell viability was quantified by trypan blue exclusion. Briefly, harvested cells were resuspended and mixed 1:1 with 0.4% trypan blue solution. After a 3-minute incubation at room temperature, the mixture was loaded into a hemocytometer chamber. Viable (unstained) and non-viable (blue) cells were counted under a microscope to calculate the percentage of viable cells63.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft) and GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software). The circadian rhythmicity of temperature fluctuation was detected using the cosinor method, rhythmicity was defined by a confidence region for the MESOR with a level of significance of P≤0.05. The values are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical details of experiments can be found in the figure legends, figures, and the results section.

Data availability

The simulation codes and the original experimental data reported in this paper are available from the link: https://github.com/hitolab/humanclock. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Code availability

The simulation codes and the original experimental data reported in this paper are available from the link: https://github.com/hitolab/humanclock. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

Dunlap, J. C., Loros, J. J. & DeCoursey, P. J. Chronobiology: biological timekeeping. (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA., 2004).

Buhr, E. D., Yoo, S.-H. & Takahashi, J. S. Temperature as a universal resetting cue for mammalian circadian oscillators. Science 330, 379–385 (2010).

Isojima, Y. et al. Ck1ε/δ-dependent phosphorylation is a temperature-insensitive, period-determining process in the mammalian circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15744–15749 (2009).

Terauchi, K. et al. ATPase activity of KaiC determines the basic timing for circadian clock of cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16377–16381 (2007).

Mehra, A. et al. A role for casein kinase 2 in the mechanism underlying circadian temperature compensation. Cell 137, 749–760 (2009).

Zhou, M., Kim, J. K., Eng, G. W. L., Forger, D. B. & Virshup, D. M. A period2 phosphoswitch regulates and temperature compensates circadian period. Mol. Cell 60, 77–88 (2015).

Maeda, A. E., Matsuo, H., Muranaka, T. & Nakamichi, N. Cold-induced degradation of core clock proteins implements temperature compensation in the arabidopsis circadian clock. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq0187 (2024).

Kidd, P. B., Young, M. W. & Siggia, E. D. Temperature compensation and temperature sensation in the circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E6284–E6292 (2015).

Hong, C. I., Conrad, E. D. & Tyson, J. J. A proposal for robust temperature compensation of circadian rhythms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1195–1200 (2007).

Hatakeyama, T. S. & Kaneko, K. Generic temperature compensation of biological clocks by autonomous regulation of catalyst concentration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8109–8114 (2012).

Kurosawa, G., Fujioka, A., Koinuma, S., Mochizuki, A. & Shigeyoshi, Y. Temperature–amplitude coupling for stable biological rhythms at different temperatures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005501 (2017).

Hastings, J. W. & Sweeney, B. M. On the mechanism of temperature independence in a biological clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 43, 804–811 (1957).

Kondo, T. & Tsudzuki, T. Phase progress under low temperature treatment of the potassium uptake rhythm in a duckweed, lemna gibba g3. Plant cell Physiol. 21, 95–103 (1980).

Zimmerman, W. F. On the absence of circadian rhythmicity in drosophila pseudoobscura pupae. Biol. Bull. 136, 494–500 (1969).

Roberts, S. K. D. F. Circadian activity rhythms in cockroaches ii. entrainment and phase shifting. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 59, 175–186 (1962).

Francis, C. D. & Sargent, M. L. Effects of temperature perturbations on circadian conidiation in neurospora. Plant Physiol. 64, 1000–1004 (1979).

Bieniawska, Z. et al. Disruption of the arabidopsis circadian clock is responsible for extensive variation in the cold-responsive transcriptome. Plant Physiol. 147, 263–279 (2008).

Ramos, A. et al. Winter disruption of the circadian clock in chestnut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7037–7042 (2005).

Martino-Catt, S. & Ort, D. R. Low temperature interrupts circadian regulation of transcriptional activity in chilling-sensitive plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 3731–3735 (1992).

Carey, H. V., Andrews, M. T. & Martin, S. L. Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol. Rev. 83, 1153–1181 (2003).

Revel, F. G. et al. The circadian clock stops ticking during deep hibernation in the european hamster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 13816–13820 (2007).

Enoki, R. et al. Cold-induced suspension and resetting of ca2+ and transcriptional rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. iScience 26 (2023).

Strogatz, S. H. Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: with applications to physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering (Westview press, Boulder, 2015).

Murayama, Y. et al. Low temperature nullifies the circadian clock in cyanobacteria through hopf bifurcation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 5641–5646 (2017).

Izhikevich, E. Dynamical Systems in Neuroscience (MIT Press, 2007).

Meeuse, M. W. et al. Developmental function and state transitions of a gene expression oscillator in caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Syst. Biol. 16, e9498 (2020).

Pittendrigh, C. S. Circadian clocks: What are they. The molecular basis of circadian rhythms 11–48 (1976).

Cox, K. H. & Takahashi, J. S. Circadian clock genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 63, R93–R102 (2019).

Ko, C. H. & Takahashi, J. S. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, R271–R277 (2006).

Kawamoto, N., Ito, H., Tokuda, I. T. & Iwasaki, H. Damped circadian oscillation in the absence of kaia in synechococcus. Nat. Commun. 11, 2242 (2020).

Kim, J. K. & Forger, D. B. A mechanism for robust circadian timekeeping via stoichiometric balance. Mol. Syst. Biol. 8, 630 (2012).

Gonze, D. & Ruoff, P. The goodwin oscillator and its legacy. Acta Biotheoretica 69, 857–874 (2021).

Akashi, M. et al. Noninvasive method for assessing the human circadian clock using hair follicle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15643–15648 (2010).

Mäkinen, T. M. et al. Seasonal changes in thermal responses of urban residents to cold exposure. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 139, 229–238 (2004).

Tsuzuki, K., Okamoto-Mizuno, K. & Mizuno, K. The effects of low air temperatures on thermoregulation and sleep of young men while sleeping using bedding. Buildings 8, 76 (2018).

Yoo, S.-H. et al. Period2:: Luciferase real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc. Natl .Acad. Sci. USA 101, 5339–5346 (2004).

Yamazaki, S. et al. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science 288, 682–685 (2000).

Baggett, B. et al. Thermostability of firefly luciferases affects efficiency of detection by in vivo bioluminescence. Mol. imaging 3, 324–32 (2004).

Izumo, M., Johnson, C. H. & Yamazaki, S. Circadian gene expression in mammalian fibroblasts revealed by real-time luminescence reporting: temperature compensation and damping. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 16089–16094 (2003).

Grahn, D., Miller, J., Houng, V. & Heller, H. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in hibernating ground squirrels. Am. J. Physiol.-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 266, R1251–R1258 (1994).

Menaker, M. Endogenous rhythms of body temperature in hibernating bats. Nature 184, 1251–1252 (1959).

Vitaterna, M. H. et al. The mouse clock mutation reduces circadian pacemaker amplitude and enhances efficacy of resetting stimuli and phase–response curve amplitude. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9327–9332 (2006).

Minami, Y. et al. Transgenic rats expressing dominant negative bmal1 showed circadian clock amplitude reduction and rapid recovery from jet lag. Eur. J. Neurosci. 53, 1783–1793 (2021).

Iiams, S. E. et al. Loss of functional cryptochrome 1 reduces robustness of 24-hour behavioral rhythms in monarch butterflies. Iscience 27 (2024).

Richter, P. H. & Ross, J. Concentration oscillations and efficiency: glycolysis. Science 211, 715–717 (1981).

Lazar, J. G. & Ross, J. Changes in mean concentration, phase shifts, and dissipation in a forced oscillatory reaction. Science 247, 189–192 (1990).

Ouyang, Y., Andersson, C. R., Kondo, T., Golden, S. S. & Johnson, C. H. Resonating circadian clocks enhance fitness in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 95, 8660–8664 (1998).

Dodd, A. N. et al. Plant circadian clocks increase photosynthesis, growth, survival, and competitive advantage. Science 309, 630–633 (2005).

Lambert, G., Chew, J. & Rust, M. J. Costs of clock-environment misalignment in individual cyanobacterial cells. Biophys. J. 111, 883–891 (2016).

Hozer, C., Perret, M., Pavard, S. & Pifferi, F. Survival is reduced when endogenous period deviates from 24 h in a non-human primate, supporting the circadian resonance theory. Sci. Rep. 10, 18002 (2020).

Libert, S., Bonkowski, M. S., Pointer, K., Pletcher, S. D. & Guarente, L. Deviation of innate circadian period from 24 h reduces longevity in mice. Aging cell 11, 794–800 (2012).

Wyse, C., Coogan, A., Selman, C., Hazlerigg, D. & Speakman, J. Association between mammalian lifespan and circadian free-running period: the circadian resonance hypothesis revisited. Biol. Lett. 6, 696–698 (2010).

Nakayama, T. et al. A transcriptional program underlying the circannual rhythms of gonadal development in medaka. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2313514120 (2023).

Mihalcescu, I. et al. When lowering temperature, the in vivo circadian clock in cyanobacteria follows and surpasses the in vitro protein clock trough the hopf bifurcation. Sci. Rep. 15, 14884 (2025).

Duan, J., Greenberg, E. N., Karri, S. S. & Andersen, B. The circadian clock and diseases of the skin. FEBS Lett. 595, 2413–2436 (2021).

Hillen, H., Breed, W. & Botman, C. Scalp cooling by cold air for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Neth. J. Med. 37, 231–235 (1990).

Nishimura, T. et al. Endocrine, inflammatory and immune responses and individual differences in acute hypobaric hypoxia in lowlanders. Sci. Rep. 13, 12659 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Modulation of circadian clock by crude drug extracts used in japanese kampo medicine. Sci. Rep. 11, 21038 (2021).

Xiao, Y. et al. Circadian clock gene bmal1 controls testosterone production by regulating steroidogenesis-related gene transcription in goat leydig cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 236, 6706–6725 (2021).

Lee, T. et al. Development of model based on clock gene expression of human hair follicle cells to estimate circadian time. Chronobiol. Int. 37, 993–1001 (2020).

Nishida, A., Miyawaki, Y., Node, K. & Akashi, M. Ex vivo culture assay using human hair follicles to study circadian characteristics. Bio-Protoc. 10, e3638–e3638 (2020).

Yamaguchi, A. et al. A simple method using ex vivo culture of hair follicle tissue to investigate intrinsic circadian characteristics in humans. Sci. Rep. 7, 6824 (2017).

Strober, W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 111, A3–B (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank T.N. Ohkawa, T. Yoshimura (Nagoya University) for providing U2OS cells; T. Ma, S. Yasuo (Kyushu University) for the technical support on the cell culture experiments; and M. Akashi (Yamaguchi University) for the helpful discussions about human hair follicles. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI to H.I. (JP23H04475, JP25H02463), and to T.N. (JP23K27259), AMED CREST to H.I. (JP24gm2010005), and the scholarship from the Chinese Government Scholarship Council to Y.X. (202006300020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and H.I.; methodology, Y.X., T.N., and H.I.; investigation, Y.X., Y.S., and H.I.; writing–original draft, Y.X. and H.I.; writing–review & editing, Y.X. and H.I.; funding acquisition, H.I. and T.N.; supervision, H.I.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Y., Sainoo, Y., Nishimura, T. et al. Low temperature abolishes human cellular circadian rhythm through Hopf bifurcation. npj Syst Biol Appl 12, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00628-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00628-5